Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 313

February 15, 2016

Music pours down in Lima

Welcome back to Teca, Latin America is a Country’s own jukebox, where we’ll introduce you to some of the coolest, hippest, most recent music from cities around Latin America.

It never rains in Lima. Even if this is not entirely true, you are likely to hear Peruvians say this often about their capital on the shore of the Pacific Ocean. It is humid, but temperate out there, and though there is (almost) no rain, there are always clouds closing over the Limeño sky.

Maybe this is why, when I think about the music of Lima, I first think about introspective bands with beautifully arranged bittersweet, rueful songs. But this city of nine million people (about 30% of Peru’s total population) has plenty to offer, from the cumbia chicha bands of the local huekos, to a punk-rock revival, to a never-ending supply of electrocumbia sounds, and much more.

This is why we’re bringing you a new edition of Teca right from the City of Kings, with some of the hippest and coolest limeño bands. Here’s our brief selection:

Kanaku y el Tigre

Bruno Bellatín and Nicolás Saba had been playing music together for over 15 years in Lima. They collaborated often, but had their own projects. Then, Saba started to call himself “El Tigre.” One day, Bellatín realized they were collaborating all the time, so he thought maybe he should find a name for himself to accompany “El Tigre.” He chose “Kanaku,” which Bellatín says is “a call to introspection.” And, thus, Kanaku y el Tigre was born.

They play banjos, ukuleles, Peruvian charangos, as well as various toy instruments, and they got some people to play drums, percussions and horns, too. They say their sound is “Peruvian Psychedelic Funk,” but that seems to fall short to describe the beautiful simplicity of their songs, which may appear bare upon first inspection, but are truly rich and decorated.

They debuted with the album Caracoles in late 2010 (from which the below track, “Bicicleta,” comes from), with which they became known around the Latin American indie scene. Last year, they followed up with Quema, Quema, Quema, which features cover art designed by hyper-famous Argentinean cartoonist Liniers, as well as the sounds of more traditionally pop/rock instruments and beats, but still with a definitive style.

Tourista

Legend has it that, a few years ago, Rui Pereira decided to move to the Lima beach to record a demo. One day, Sandro Labenita dreamed he was in a band with Rui. Sandro told Rui of this dream and they decided to come together to form Tourista, a dance-rock, indie-pop trio (completed by the synth-master known as Genko) that has gotten airplay throughout Peru.

They debuted in 2012 with their EP Déficit de atención, fast-paced, danceable punk-rock music aided by synths, loops and Pereira’s catchy lyrics. This week they will debut a new album, Colores paganos, which they promise will be filled with more Afro-Peruvian instruments, as well as more Andean and tropical melodies.

The first single from Colores paganos, “Select y Start,” promises a much slower, more introspective record. But for now, here is the song that made me love them:

La Lá

In 2014, the singer/songwriter La Lá released her album Rosa which, I hope, was played next to many lit fireplaces, or within reach of ocean waves. Her music is, as her website describes it, the music of intimacy, music that “invites you to take a nap in the sofa, or drink a tea while you look out the window after having lunch.”

It is a very fragile, internal, personal state, and the minimal arrangements do perfect justice to La Lá’s voice, a voice that slowly wraps around you and keeps you comfort. So get the wine out, dim the lights, and listen to her powerfully subtle vocals:

Pamela Rodríguez

Wow, 2011 was five years ago? That’s when Pamela Rodríguez released her latest album, Reconocer, an indie record that still sounds relevant. There, she sings in a way that makes you listen to what she’s saying, with a particular twist to the female singing voice that has become common in some Latin American indie acts.

Her singing voice and style has changed considerably from her debut album Peru Blue (2005) and her second record La orilla (2008), but I believe it has changed for the better. Fortunately, for those of us who wanted to hear her again, last year Pamela released a song (or EP?) in four movements: Una herida hecha luz.

Amadeo Gonzales

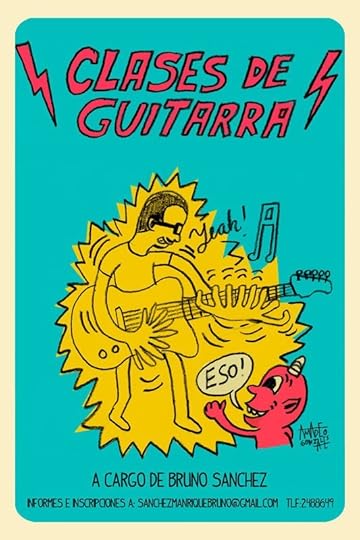

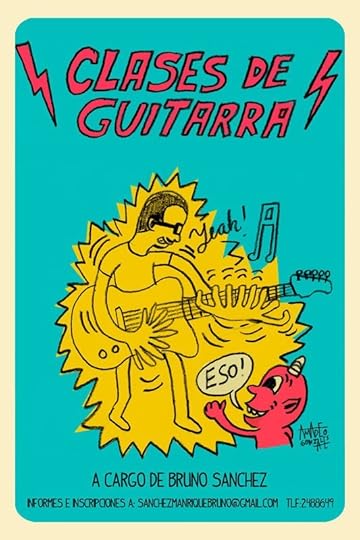

Are you looking for a Peruvian folk idol who is also a cartoonist, a graphic artist and a bit of a legend in the fanzine movement? Well, look no further than Amadeo Gonzales, who is all of that and maybe a bit more.

Amadeo and his brother Renso have published the cartoon fanzine Carboncito since 2001 and they have worked in many other cartoon publications since then. Amadeo has also worked extensively in concert posters and various graphic design projects. His work has been showcased in galleries throughout Peru. And he has also recorded two albums Mostros, marcianos y rocanrol (2011) and Perro de la calle (2014).

Both of them are very simple affairs. Amadeo, the self-taught musician, is not looking to get complex or layered in his recordings, just to create catchy, witty tunes. And he definitely succeeds. In particular in his song “El marciano,” in which a Martian says something unintelligible to Amadeo, until its warning becomes clear:

Also check out: surf-rockers Almirante Ackbar, synth-pop experimenters Las Amigas de Nadie, indie pop melancholic Mondebel, Nico Saba’s side project Los X Conchas Negras, techno cumbia masters of ceremonies Dengue Dengue Dengue!, and whatever the guys at El Chico del Pórtico have to showcase.

An Amadeo Gonzales poster.

An Amadeo Gonzales poster.Check out the rest of Teca here.

Did we miss any bands? Tell us in the comments below, or in our twitter, , or .

Teca #5: Music pours down in Lima

Welcome back to Teca, Latin America is a Country’s own jukebox, where we’ll introduce you to some of the coolest, hippest, most recent music from cities around Latin America.

It never rains in Lima. Even if this is not entirely true, you are likely to hear Peruvians say this often about their capital on the shore of the Pacific Ocean. It is humid, but temperate out there, and though there is (almost) no rain, there are always clouds closing over the Limeño sky.

Maybe this is why, when I think about the music of Lima, I first think about introspective bands with beautifully arranged bittersweet, rueful songs. But this city of nine million people (about 30% of Peru’s total population) has plenty to offer, from the cumbia chicha bands of the local huekos, to a punk-rock revival, to a never-ending supply of electrocumbia sounds, and much more.

This is why we’re bringing you a new edition of Teca right from the City of Kings, with some of the hippest and coolest limeño bands. Here’s our brief selection:

Kanaku y el Tigre

Bruno Bellatín and Nicolás Saba had been playing music together for over 15 years in Lima. They collaborated often, but had their own projects. Then, Saba started to call himself “El Tigre.” One day, Bellatín realized they were collaborating all the time, so maybe he should find a name for himself to accompany “El Tigre.” He chose “Kanaku,” which Bellatín says is “a call to introspection.” And, thus, Kanaku y el Tigre was born.

They play banjos, ukuleles, Peruvian charangos, as well as various toy instruments, and they got some people to play drums, percussions and horns, too. They say their sound is “Peruvian Psychedelic Funk,” but that seems to fall short to describe the beautiful simplicity of their songs, which may appear bare upon first inspection, but are truly rich and decorated.

They debuted with the album Caracoles in late 2010 (from which the below track, “Bicicleta,” comes from), with which they became known around the Latin American indie scene. Last year, they followed up with Quema, Quema, Quema, which features cover art drawn by hyper-famous Argentinean cartoonist Liniers, as well as the sounds of more traditionally pop/rock instruments and beats, but still with a definitive style.

Tourista

Legend has it that, a few years ago, Rui Pereira decided to move to the Lima beach to record a demo. One day, Sandro Labenita dreamed he was in a band with Rui. Sandro told Rui of this dream and they decided to come together to form Tourista, a dance-rock, indie-pop trio (completed by the synth-master known as Genko) that has gotten airplay throughout Peru.

They debuted in 2012 with their EP Déficit de atención, fast-paced, danceable punk-rock music aided by synths, loops and Pereira’s catchy lyrics. In about two weeks, they will debut a new album, Colores paganos, which they promise will be filled with more Afro-Peruvian instruments, as well as more Andean and tropical melodies.

The first single from Colores paganos, “Select y Start,” promises a much slower, more introspective record. But for now, here is the song that made me love them:

La Lá

In 2014, the singer/songwriter La Lá released her album Rosa, which subsequently, I hope, was played next to many lit fireplaces, or within reach of ocean waves. Her music is, as her website describes it, the music of intimacy, music that “invites you to take a nap in the sofa, or drink a tea while you look out the window after having lunch.”

It is a very fragile, internal, personal state, and the minimal arrangements do perfect justice to La Lá’s voice, a voice that slowly wraps around you and keeps you comfort. So get the wine out, dim the lights, and listen to her powerfully subtle vocals:

Pamela Rodríguez

Wow, 2011 was five years ago? That’s when Pamela Rodríguez released her latest album, Reconocer, an indie record that still sounds relevant. There, she sings in a way that makes you hear to what she’s saying, with a particular twist to the female singing voice that has become common in some Latin American indie acts.

Her singing voice and style has changed considerably from her debut album Peru Blue (2005) and her second record La orilla (2008), but I believe it has changed for the better. Fortunately, for those of us who wanted to hear her again, last year Pamela released a song (or EP?) in four movements: Una herida hecha luz.

Amadeo Gonzales

Are you looking for a Peruvian folk idol who is also a cartoonist, a graphic artist and a bit of a legend in the fanzine movement? Well, look no further than Amadeo Gonzales, who is all of that and maybe a bit more.

Amadeo and his brother Renso have published the cartoon fanzine Carboncito since 2001 and they have worked in many other cartoon publications since then. Amadeo has also worked extensively in concert posters and various graphic design projects. His worked has been showcased in galleries throughout Peru. And he has also recorded two albums Mostros, marcianos y rocanrol (2011) and Perro de la calle (2014).

Both of them are very simple affairs. Amadeo, the self-taught musician, is not looking to get complex or layered, just to create catchy, witty tuned. And he definitely succeeds. In particular in his song “El marciano,” in which a Martian says something unintelligible to Amadeo:

Also check out: surf-rockers Almirante Ackbar, synth-pop experimenters Las Amigas de Nadie, indie pop melancholic Mondebel, Nico Saba’s side project Los X Conchas Negras, techno cumbia masters of ceremonies Dengue Dengue Dengue!, and whatever the guys at El Chico del Pórtico have to showcase.

An Amadeo Gonzales poster.

An Amadeo Gonzales poster.Check out the rest of Teca here.

Did we miss any bands? Tell us in the comments below, or in our twitter, , or .

Jacob Zuma’s Party

You honestly wouldn’t have guessed that the guy was an intelligence operative. A big guy, sure, but dressed like he was going to the beach. No ill-fitting suit or wrap-around sunglasses.

But as he stood near the barricades where the President’s motorcade would soon pass en route to the opening of Parliament, you could see him scanning the small crowd of bystanders. Always watching.

“So what are you, the Secret Service?” I ask, trying to sound friendly.

“Something like that,” he says.

“Crime Intelligence?” I ask, referring to the police’s intelligence division.

“Yes,” he says, so matter of factly that it caught me off guard. That the state intelligence agencies surveil protesters and activists, including deploying undercover agents to crowds, is not news, but I did not expect such candour.

I ask him how many of his colleagues are here, fishing for a general number. But my new friend surprises me again, and points.

“There’s one, and the guy next to him. And over there.” We are at one of the short stretches of the parade route that has been opened for public bystanders. Maybe 20 metres long. The crowd is thin here, just a few dozen people. He’s just told me at least four undercover intelligence agents are among them (including him). One can only imagine how many have been deployed in total.

Why would he tell me this? I assume because, like many others, he is disgruntled at this state of affairs. That his mind boggles at how much security and resources have been brought to bear on this occasion — essentially, to control the crisis of one man.

Image by Shaun Swingler/Chronicle.

Image by Shaun Swingler/Chronicle.***

Everyone I speak to says this is an unprecedented level of security for the opening of Parliament.

Barbed wire has been rolled out along Darling Street and Adderley, effortlessly rolled off the back of those trucks that we remember from Marikana. Eight-foot high metal barricades line the route that Zuma will take – coming past District Six down Roeland Street, right on Plein Street, left on Spin Street, and pulling into Parliament’s gates behind the Slave Lodge.

The police are out in numbers that are simply extraordinary. There is a phalanx of cops on every corner and many have formed barriers across major intersections, backed up by Nyalas and water cannons. Units of the Public Order Police –our riot police – seem to have been called in from every corner of the country. I see SAPS bakkies from as far off as Upington and Kimberley. We hear reports that police have been bussed in from other provinces too. The city’s municipal police divisons are all out in riot gear too.

Farther back I see a few members of South Africa’s controversial paramilitary units, the Tactical Response Team with their berets, and the Special Task Force with their SWAT-style helmets. (Not carrying rifles, for once.) Off to one side, we even see a cluster of Cape Town’s liquor squad dressed in body armour. None of them looks too happy.

With this show of force, I wonder who the hell is policing the rest of the country? It’s an uncomfortable point for those who believe there should be fewer police, or none at all, but most people living in South Africa want more and better police in their communities. In surveys, crime features as the second or third biggest concern for citizens, after jobs and housing. The police have been slammed before for their unequal allocation of resources. So what is the knock-on effect on the safety of ordinary citizens when hordes of police are withdrawn from the communities they are ostensibly meant to serve, and dragged all the way to Cape Town to form a wall between the President and the people?

Several protests have taken place today, across a wide political spectrum. A Zuma Must Fall march unfolded without incident earlier in the day, and the ANC-aligned Ses’khona People’s Movement and MK Veterans Association marched ostensibly to commemorate the anniversary of Mandela’s release, though they are led by a banner saying “The DA Has Hatred for Black People”. As the day grows later, a large crowd of EFF supporters splits off from the Zuma Must Fall gathering, and heads up Adderley Street with a contingent of Pan Africanist Congress activists and students under the banner of #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall. Suddenly, up ahead, the police have blocked the way with a wall of shields. We can’t see what’s happening from further back, but suddenly stun grenades are exploding at the front and everyone falls back. Later, video footage of skirmishes between a few Ses’khona supporters and the EFF will appear online, but largely people are pissed off but peaceful.

Accusations circulate later on social media that police played a partisan role, policing some protests aggressively while giving others space. Photos also emerge of a riot cop tearing up placards brought by the students. One reads: No Free Education No Vote.

***

South African Police Service member tears up a placard stating “No Free Education No Vote”. Photo by Wandile Kasibe.

Eventually, in a quieter side of town, Zuma’s motorcade sweeps in. And it’s eerie. The marching bands have come and gone. Honour guards from the Navy stand in silence along the route. The crowd is so thin where I’m standing that bystanders are outnumbered by theParliamentary security staff. Suddenly, military police trot past on horseback. Then military police on motorbikes. Then several sedans full of presidential security, and then Zuma himself sweeps by in what can only be described as a Pope Mobile. He waves, but there is almost nobody here to see him. Aside from the hum of engines, the moment passes in silence. Later I will read that he did not walk the red carpet per tradition, but was driven right up Parliament Avenue and deposited on the very final stretch of red carpet.

Put these security measures together, and you have to assume that important people believe this man is unsafe. The threat assessment must be off the charts.

***

Later, as dusk gathers I get on my bike and cruise the empty streets around Parliament, the President’s address streaming through my headphones via the SABC. “Compatriots,” he tells us, “We are proud of our democracy and what we have achieved in a short space of time.”

I go past barbed wire and barricades and detritus.

“Our democracy is functional, solid and stable.”

I pass an armoured Nyala, where a cluster of cops from some other place are listening to the address as well.

“The Constitution, which has its foundation in the Freedom Charter, proclaims that South Africa belongs to all who live in it.”

We should not fall into the trap of Zuma-Must-Fallists who attribute all our problems to one man. But the ruin and the chaos in our streets today seem like the product of a system that has stretched and distorted to accommodate the crises of one man. It has bent itself to be shaped to his needs. And it probably can’t bend much further.

February 14, 2016

It’s the economy, stupid (also known as our new, weekly economics post) N°1

Given that we have an economist on board, it would be a crime not to ask him to do weekly post / “column”–called Its The Economy Stupid where he does a post with listicles of economic news; more like help us make sense of what mattered that week in economic policy, the markets or debates among experts. It was basically his informative Facebook posts about economic politics in his native Zambia, that got my thinking. Grieve Chelwa, of course, is duly qualified. He has a Ph.D in Economics from the University of Cape Town and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University’s Center for African Studies . You’ll also remember Grieve for this .—Sean Jacobs

(1) We’ll start where else but in the United States of America where Hillary Clinton, the presumptive presidential candidate of the Democratic Party, is facing questions about paid speeches she gave to the money men and women at Goldman Sachs. So at this Goldman Sachs shindig, Hilary Clinton makes a couple of jokes (watch beginning from the 6:30 mark) about a meeting she had with some “African” economists in the 90s and how she challenged them on the exclusion of women’s work in GDP statistics on the continent. The audience clearly enjoys this segment of the talk and has a series of laughs at the expense of the poor African economists.

Firstly, Madame Clinton should tell us the names of the “African” economists she met with. Inquiring minds want to know. Secondly, the joke’s on this audience because women’s domestic work is hardly reflected in GDP statistics even in the U.S. And by the way, women’s contribution to, for instance, agriculture in most African countries are relatively well captured in agricultural surveys. And agriculture is not an insignificant part of total output on the continent.

(2) Burkina Faso, which has been Africa’s biggest adopter of Genetically Modified (GM) Crops, has announced plans to phase out GM cotton. Adopting GM cotton increased Burkina’s cotton output. But it turns out that the GM cotton delivered a far inferior cotton quality resulting in “severe economic losses for Burkinabe cotton companies”. This development will definitely impact the GM adoption debate on the continent going forward. (Some additional reading is here).

(3) The 2016 Winter Edition of the Journal of Economic Perspectives has an entire symposium on the “Bretton Woods Institutions” (World Bank, IMF and World Trade Organization). Some of the essays, particularly this one by Martin Ravallion, are somewhat critical of the World Bank. Unfortunately, none of the essays feature writers from the “South”, particularly in light of the long history of interaction between these institutions and the countries of the South. Alas. (By the way, all the essays are free to read without the need for a subscription).

(5) Related to item number 4, the U.S. is emerging as the world’s favorite new tax haven: “Everyone from London lawyers to Swiss trust companies is getting in on the act, helping the world’s rich move accounts from places like the Bahamas and the British Virgin Islands to Nevada, Wyoming, and South Dakota”. Remember that story about Teodoro Obiang’s mansion in Malibu, California?

(6) So Barack Obama has signed into law the Electricity Act of 2015 which provides legal backing for his “Power Africa Initiative”. The initiative was announced during Obama’s tour of Africa in 2013 and aims to bring electricity to 50 million people on the continent by 2020. The U.S government has made financial “commitments” of $7bn towards the initiative plus $43bn in pledges from “partners”. Any investment into Africa’s power sector should certainly be welcomed but calling the initiative “Power Africa” might be a bit of a stretch. For one thing, the International Energy Agency reckons the continent needs to invest about $55bn per annum until 2040 to meaningfully power the continent.

(7) We are not surprised that the global aid industry transforms “unremarkable young people [from the West] into a little aristocracy [in much of Africa]”.

(8) The economic “burden” of hosting refugees for Western European countries is tiny. It would even be smaller if they were allowed to work. Hmmm, we wonder what explains all the refugee bashing, then?

(9) Nigeria is facing a widening fiscal deficit (which is the difference between government expenditure and government revenue) mainly as a result of dwindling revenues from oil exports. News broke a couple of weeks ago that Africa’s biggest economy was in talks with the World Bank and the African Development Bank for $3.5bn in emergency loans. The news was swiftly dismissed by the Minister of Finance who said the country had merely held “exploratory” talks with the World Bank. Nigeria’s story is now typical as the continent struggles with debt issues after borrowing heavily over the last decade when commodity prices were high and mighty (see Chad’s, Ghana’s and Zambia’s stories).

(10) The rate of inflation in Zambia (which is the rate at which prices are increasing) more than doubled to 21% in January 2016 from 7% in January 2015. The Kwacha’s underperformance in 2015 largely explains much of the rise in prices over the two time periods. Rising prices might turn out to be a significant factor in the presidential elections slated for August this year.

(11) January was the 101st birthday anniversary of Professor W. Arthur Lewis. Professor Lewis is the first and only black person to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. He also served as economic advisor to Kwame Nkrumah and some of his thinking around development economics was influenced by his time in Ghana.

(12) Finally, Julius Sello Malema, firebrand leader of South African opposition party, the Economic Freedom Fighters, had lunch with the Financial Times last week. The ending is gold.

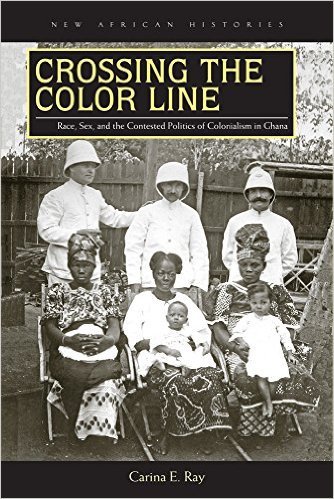

Valentine’s Day special! On love, race and history in Ghana

A couple months ago I was fortunate to read Carina Ray’s excellent new book Crossing The Color Line: Race Sex and the Contested Politics of Colonialism in Ghana on the history on interracial intimacy on the Gold Coast. I decided to interview her for AIAC and when our conversation moved from political economy and racism to political economy, racism and love, we figured – Valentine’s Day! So here it is: an AIAC take on love, critical politics included.

Why do you think that the history of interracial intimacy in the Gold Coast / Ghana important? What drew you to study it and to these stories in particular?

Let me answer the second question first. When I started the archival work that culminated in Crossing the Color Line, my intention was to write an altogether different book about multiracial people in colonial and post-independence Ghana. Much has been written about them in the context of the precolonial period as cultural, social, political, and linguistic intermediaries—the ubiquitous “middle(wo)men” of the trans-Atlantic trade, especially as it became almost exclusively focused on the slave trade. Hardly anything, however, has been written about this group during the period of formal colonial rule in British West Africa. So I set out to do just that, but quickly discovered that while the archive had much to say about interracial sexual relations in the Gold Coast, there was relative silence about their progeny.

This struck me as an intriguing departure from most early-twentieth century colonial contexts in which anxieties about multiracial people spurred increasing condemnation and regulation of interracial sex. In the introduction and first chapter I spend some time addressing why a book about sex across the color line has comparatively little to say about multiracial people. This was largely because multiracial Gold Coasters during the formal colonial period generally identified themselves, and were identified by Africans and Europeans alike, as Africans. To my mind it would have been ahistorical to write about them as a distinct social group. This allowed me to engage the question of interracial sexual relations in a deep and substantive way in its own right, instead of as a precursor to progeny.

To answer your first question about why this history is important, I have to return again to the nature of my archives. What jumped out at me immediately when I started working with the sources was the extent to which they revealed not only the deeply human and interpersonal dimensions of these relationships, but also the wider grid of Afro-European social relations that they were embedded in. The colonial government’s obsessive focus on interracial sex was methodologically generative because it produced a multidimensional archive that provided surprisingly detailed accounts of the conflicts and connections that characterized the everyday lives of and interactions between Africans and Europeans. What at first glance may seem like a narrow focus on interracial sexual relationships actually opens up an unprecedented view into colonial race relations in the Gold Coast. Part of what makes these relationships so compelling and important, then, is their potential to recalibrate our thinking about colonial economies of racism in ways that allow us to see greater parity between settler and administered colonialism without suggesting an equivalence.

But these relationships are also important in their own right, not least because so many of them force us to reckon with the unsettling gray area where racism and affect could and often did coexist. How else can you explain the British doctor who risked his distinguished career as a colonial medical officer to marry across the color line, and then proceeded to maintain his membership in a Europeans-only club that barred his African wife? In this and in so many other instances where I was confronted with relationships that resisted neat categorization, I found myself recalling Frantz Fanon, who in writing about interracial intimacies in Black Skin, White Masks, says “Today we believe in the possibility of love, and that is the reason why we are endeavoring to trace its imperfections and perversions.” I can’t think of a more profound or precise theoretical approach to the problem of love, in general, and the problem of love across the color line, in particular. This is not to suggest that all of the relationships I document in Crossing the Color Line were loving, but rather to say that loving relationships were not immune to the racism of their time.

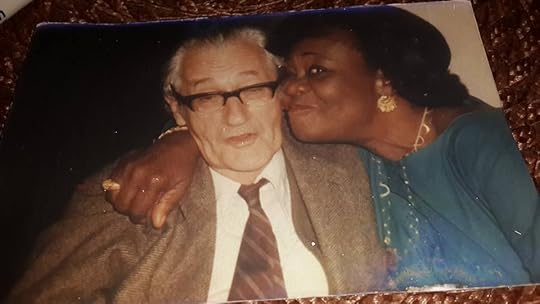

Despite colonial administrators’ attempts to sabotage their marriage plans, Brendan (a district commissioner) and Felicia Knight wed in 1945. Fifteen years later, Felicia staged a successful one-woman-protest in front of Flagstaff House to save her husband’s job during the Africanization of government service. On the grounds that he was married to a Ghanaian and raising their five children as Ghanaians, Kwame Nkrumah retained Brendan in government employ.

Despite colonial administrators’ attempts to sabotage their marriage plans, Brendan (a district commissioner) and Felicia Knight wed in 1945. Fifteen years later, Felicia staged a successful one-woman-protest in front of Flagstaff House to save her husband’s job during the Africanization of government service. On the grounds that he was married to a Ghanaian and raising their five children as Ghanaians, Kwame Nkrumah retained Brendan in government employ.Why and how did interracial sex go from being a fact to being a problem?

Although both Africans and Europeans most forcefully articulated interracial sex as a problem during the colonial period, I think its important to point out that during the precolonial period Africans tightly regulated these relationships in ways that indicate that they recognized their potential benefits and risks. Likewise, the various European powers that held sway along the Gold Coast managed their varying anxieties over these relationships in ways that recognized their indispensability to the European presence on the coast. That’s an important background to the question so that readers are not mislead into thinking that the Gold Coast was an interracial sexual utopia prior to the onset of formal British rule.

What was different about the first decade of the twentieth century was that the hyper-racialization of formal colonial rule meant that the very things that had once made interracial sexual relationships indispensable—namely their ability to acculturate and integrate European men into local societies in ways that allowed them to develop beneficial reciprocal networks—were now “undesirable.” Indeed that was the very term Governor John Rodger used to describe relationships between African women and European officers when he officially banned them in 1907. Coming on the heels of “a century-long shift from a Britain that asked to one that demanded and a last commanded,” to borrow from Tom McCaskie, the ban on concubinage not only signaled a new political modus operando, it also heralded a new era of colonial racial insularity, albeit one that was never fully achieved.

Readers won’t be surprised that interracial sexual relationships emerged as a “problem” under formal colonial rule, but what I hope to show is that making concubinage a punishable offense did more to undermine British authority than it did to preserve it. This is particularly evident not only in the individual disciplinary cases brought against offending British officers, but also in the wider current of anticolonial agitation that swelled around the increasingly illicit nature of interracial sexual relations. These relationships could no longer be publicly recognized and so they appeared all the more unseemly to Gold Coasters, who used them to call into question the moral credibility of British colonial rule. In short it was how the British chose to manage concubinage, as a problem, that actually became the bigger problem in the end.

I want to pursue an issue you raised in your first response. What about love? Where is the scholarship on love in African history? We hear a lot about pain, we learn a lot about anger and hate, but what of affection? How do your stories contribute to the history of love and what lessons do they teach us for love’s present?

Your question rightly points to a massive lacuna in our field, but also to deeper more unsettling questions about why historians have, until very recently, neglected love as a historical force and object of analysis in Africa. That pain, hate, and ager, to which I would add fear and suspicion, surface so frequently says more about the biases that shape our field, than it does about the affective and emotive economies that shape the lived experiences of African peoples, past and present. I would be remiss if I didn’t add that in as much as I think Africanist historians need to move beyond functionalist or transactional approaches to sexuality, marriage, and allied concerns, to get at affect, I also think that the scholarship on love elsewhere in the world would do well to remember just how intertwined affect and function can be…just how transactional love can be. Forget about romantic love, anyone with a kid knows that love is amenable to being bought!

But back to the scholarship. When Jennifer Cole and Lynn Thomas published Love in Africa – a book that is never out of my arm’s reach – I remember thinking to myself, this book is as close to a mic drop as any of us Africanist historians will ever come! TADOW! For me their book is the “call,” and now the question is, what’s the “response.” Jennifer had already pointed the way with Sex and Salvation: Imagining the Future in Madagascar, a beautifully and persuasively written historically-informed ethnography, and Rachel Jean-Baptiste’s Conjugal Rights: Marriage, Sexuality, and Urban Life in Colonial Libreville, Gabon takes up the challenge too. I also appreciated Pernille Ipsen’s analysis of love in her book Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast, which moves beyond a purely functional or pragmatic reading of Ga-Danish marriages in the context of the transatlantic slave trade. But clearly much more work is needed on this front.

In the case of Ghana and Britain both colonial racism and anticolonial resistance conditioned the possibilities for love across the color line in the twentieth century. The raced and gendered configuration of couples—African woman/European man or African man/European woman—and the respective political and social geographies of colony and metropole they inhabited shaped not only the kinds of emotional ties that developed, but also our ability as historians to interpret those ties. I was constantly aware of how much more fraught it was to write about the affective ties between African women and European men in the Gold Coast than about about love and affection between African men and European women in the British ports or elsewhere in Europe. Comparatively fewer caveats seemed necessary and I am still grappling with the why of that, especially since Marc Matera does such a superb job of showing just how racially vexed those relationships were in Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century.

But I also think there is something more fundamental at work in how people think about love as a panacea that is profoundly reductive and hinders our ability to see the ways in which love has and continues to coexist with racism…and a range of other isms for that matter. It’s clear from many of the stories in Crossing the Color Line that a variety of affective ties grew amidst the racism and exploitative and unequal power relations that shaped these relationships. That observation still holds true. I’m always struck by the lack of attention paid to how racism operates internally within interracial relationships today, yet there is no shortage of reportage, like this and this, emphasizing how external societal racism negatively impacts interracial couples. The assumption seems to be that if you are in an interracial relationship you can’t be racist. Well, we know that’s not true.

You’ve given us a lot to think about. I know that some historians don’t like being asked about what their work means for our present and future, but I was hoping you could underline your book’s contribution to ongoing conversations in the continent and diaspora. What do you hope readers take away from your work?

Actually, I take a very different approach. I think its crucial, especially as Africanists, to think about what our work means for the present and future precisely because the African past is always at play in the ways that people think about, talk about, write about, make policies about, etc., etc., Africa today. The very fact that our field is in itself a repudiation of centuries of racist thought about Africa’s lack of history and its lack of coevalness with the West, points to the urgency of actively engaging the present and the future, when and where possible, in our research.

That ideological commitment is at the heart of my book’s conclusion. In the section on “Interracial Heterosexuality, Homosexuality, and States of Panic,” I draw on the insights gleaned from my work on colonial interracial heterosexual relations in Ghana to think through the recent intensification of church and state-sponsored homophobia in a number of different African countries. Subjecting contemporary homophobic discourses to both comparative and historical analysis reveals them to be part of a much longer history of sexual panics visible across different parts of the continent, especially during the colonial period and continuing through today. In taking this approach, what I hoped to show is that homophobia in places like Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Uganda today does not represent an incomprehensible form of African social conservatism, a claim that inevitably leads down a slipper slope toward old tropes of African backwardness and stasis, underpinned, as they are, by the idea that Africa and modernity are incompatible. Rather, like the sexual panics that gripped their colonial predecessors, it is better understood as a symptom of deeper anxieties and social dis-ease occasioned by the crises facing the state in post-independence Africa – of which those at the forefront of this disturbing trend are unsurprisingly also those facing particularly acute crises of legitimacy.

What’s next? Where do you go from here?

I have the tremendous privilege this year of being at the Society for the Humanities at Cornell, where I’m getting started on my new book project, tentatively titled “Somatic Blackness: A History of the Body and Race-Making in Ghana.” In so many ways this is the book that I thought I would write first, so it represents a return to the foundational questions about race, identity, blackness, and the body that first captured my attention as an undergraduate study abroad student in Ghana in 1993! Wow, I really just dated myself there.

On love, race and history in Ghana: AIAC Valentine’s Day special!

A couple months ago I was fortunate to read Carina Ray’s excellent new book on the history on interracial intimacy on the Gold Coast / Ghana. I decided to interview her for AIAC and when our conversation moved from political economy and racism to political economy, racism and love, we figured – Valentine’s Day! So here it is: an AIAC take on love, critical politics included.

Why do you think that the history of interracial intimacy in the Gold Coast / Ghana important? What drew you to study it and to these stories in particular?

Let me answer the second question first. When I started the archival work that culminated in Crossing the Color Line, my intention was to write an altogether different book about multiracial people in colonial and post-independence Ghana. Much has been written about them in the context of the precolonial period as cultural, social, political, and linguistic intermediaries—the ubiquitous “middle(wo)men” of the trans-Atlantic trade, especially as it became almost exclusively focused on the slave trade. Hardly anything, however, has been written about this group during the period of formal colonial rule in British West Africa. So I set out to do just that, but quickly discovered that while the archive had much to say about interracial sexual relations in the Gold Coast, there was relative silence about their progeny.

This struck me as an intriguing departure from most early-twentieth century colonial contexts in which anxieties about multiracial people spurred increasing condemnation and regulation of interracial sex. In the introduction and first chapter I spend some time addressing why a book about sex across the color line has comparatively little to say about multiracial people. This was largely because multiracial Gold Coasters during the formal colonial period generally identified themselves, and were identified by Africans and Europeans alike, as Africans. To my mind it would have been ahistorical to write about them as a distinct social group. This allowed me to engage the question of interracial sexual relations in a deep and substantive way in its own right, instead of as a precursor to progeny.

To answer your first question about why this history is important, I have to return again to the nature of my archives. What jumped out at me immediately when I started working with the sources was the extent to which they revealed not only the deeply human and interpersonal dimensions of these relationships, but also the wider grid of Afro-European social relations that they were embedded in. The colonial government’s obsessive focus on interracial sex was methodologically generative because it produced a multidimensional archive that provided surprisingly detailed accounts of the conflicts and connections that characterized the everyday lives of and interactions between Africans and Europeans. What at first glance may seem like a narrow focus on interracial sexual relationships actually opens up an unprecedented view into colonial race relations in the Gold Coast. Part of what makes these relationships so compelling and important, then, is their potential to recalibrate our thinking about colonial economies of racism in ways that allow us to see greater parity between settler and administered colonialism without suggesting an equivalence.

But these relationships are also important in their own right, not least because so many of them force us to reckon with the unsettling gray area where racism and affect could and often did coexist. How else can you explain the British doctor who risked his distinguished career as a colonial medical officer to marry across the color line, and then proceeded to maintain his membership in a Europeans-only club that barred his African wife? In this and in so many other instances where I was confronted with relationships that resisted neat categorization, I found myself recalling Frantz Fanon, who in writing about interracial intimacies in Black Skin, White Masks, says “Today we believe in the possibility of love, and that is the reason why we are endeavoring to trace its imperfections and perversions.” I can’t think of a more profound or precise theoretical approach to the problem of love, in general, and the problem of love across the color line, in particular. This is not to suggest that all of the relationships I document in Crossing the Color Line were loving, but rather to say that loving relationships were not immune to the racism of their time.

Why and how did interracial sex go from being a fact to being a problem?

Although both Africans and Europeans most forcefully articulated interracial sex as a problem during the colonial period, I think its important to point out that during the precolonial period Africans tightly regulated these relationships in ways that indicate that they recognized their potential benefits and risks. Likewise, the various European powers that held sway along the Gold Coast managed their varying anxieties over these relationships in ways that recognized their indispensability to the European presence on the coast. That’s an important background to the question so that readers are not mislead into thinking that the Gold Coast was an interracial sexual utopia prior to the onset of formal British rule.

What was different about the first decade of the twentieth century was that the hyper-racialization of formal colonial rule meant that the very things that had once made interracial sexual relationships indispensable—namely their ability to acculturate and integrate European men into local societies in ways that allowed them to develop beneficial reciprocal networks—were now “undesirable.” Indeed that was the very term Governor John Rodger used to describe relationships between African women and European officers when he officially banned them in 1907. Coming on the heels of “a century-long shift from a Britain that asked to one that demanded and a last commanded,” to borrow from Tom McCaskie, the ban on concubinage not only signaled a new political modus operando, it also heralded a new era of colonial racial insularity, albeit one that was never fully achieved.

Readers won’t be surprised that interracial sexual relationships emerged as a “problem” under formal colonial rule, but what I hope to show is that making concubinage a punishable offense did more to undermine British authority than it did to preserve it. This is particularly evident not only in the individual disciplinary cases brought against offending British officers, but also in the wider current of anticolonial agitation that swelled around the increasingly illicit nature of interracial sexual relations. These relationships could no longer be publicly recognized and so they appeared all the more unseemly to Gold Coasters, who used them to call into question the moral credibility of British colonial rule. In short it was how the British chose to manage concubinage, as a problem, that actually became the bigger problem in the end.

I want to pursue an issue you raised in your first response. What about love? Where is the scholarship on love in African history? We hear a lot about pain, we learn a lot about anger and hate, but what of affection? How do your stories contribute to the history of love and what lessons do they teach us for love’s present?

Your question rightly points to a massive lacuna in our field, but also to deeper more unsettling questions about why historians have, until very recently, neglected love as a historical force and object of analysis in Africa. That pain, hate, and ager, to which I would add fear and suspicion, surface so frequently says more about the biases that shape our field, than it does about the affective and emotive economies that shape the lived experiences of African peoples, past and present. I would be remiss if I didn’t add that in as much as I think Africanist historians need to move beyond functionalist or transactional approaches to sexuality, marriage, and allied concerns, to get at affect, I also think that the scholarship on love elsewhere in the world would do well to remember just how intertwined affect and function can be…just how transactional love can be. Forget about romantic love, anyone with a kid knows that love is amenable to being bought!

But back to the scholarship. When Jennifer Cole and Lynn Thomas published Love in Africa – a book that is never out of my arm’s reach – I remember thinking to myself, this book is as close to a mic drop as any of us Africanist historians will ever come! TADOW! For me their book is the “call,” and now the question is, what’s the “response.” Jennifer had already pointed the way with Sex and Salvation: Imagining the Future in Madagascar, a beautifully and persuasively written historically-informed ethnography, and Rachel Jean-Baptiste’s Conjugal Rights: Marriage, Sexuality, and Urban Life in Colonial Libreville, Gabon takes up the challenge too. I also appreciated Pernille Ipsen’s analysis of love in her book Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast, which moves beyond a purely functional or pragmatic reading of Ga-Danish marriages in the context of the transatlantic slave trade. But clearly much more work is needed on this front.

In the case of Ghana and Britain both colonial racism and anticolonial resistance conditioned the possibilities for love across the color line in the twentieth century. The raced and gendered configuration of couples—African woman/European man or African man/European woman—and the respective political and social geographies of colony and metropole they inhabited shaped not only the kinds of emotional ties that developed, but also our ability as historians to interpret those ties. I was constantly aware of how much more fraught it was to write about the affective ties between African women and European men in the Gold Coast than about about love and affection between African men and European women in the British ports or elsewhere in Europe. Comparatively fewer caveats seemed necessary and I am still grappling with the why of that, especially since Marc Matera does such a superb job of showing just how racially vexed those relationships were in Black London: The Imperial Metropolis and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century.

But I also think there is something more fundamental at work in how people think about love as a panacea that is profoundly reductive and hinders our ability to see the ways in which love has and continues to coexist with racism…and a range of other isms for that matter. It’s clear from many of the stories in Crossing the Color Line that a variety of affective ties grew amidst the racism and exploitative and unequal power relations that shaped these relationships. That observation still holds true. I’m always struck by the lack of attention paid to how racism operates internally within interracial relationships today, yet there is no shortage of reportage, like this and this, emphasizing how external societal racism negatively impacts interracial couples. The assumption seems to be that if you are in an interracial relationship you can’t be racist. Well, we know that’s not true.

You’ve given us a lot to think about. I know that some historians don’t like being asked about what their work means for our present and future, but I was hoping you could underline your book’s contribution to ongoing conversations in the continent and diaspora. What do you hope readers take away from your work?

Actually, I take a very different approach. I think its crucial, especially as Africanists, to think about what our work means for the present and future precisely because the African past is always at play in the ways that people think about, talk about, write about, make policies about, etc., etc., Africa today. The very fact that our field is in itself a repudiation of centuries of racist thought about Africa’s lack of history and its lack of coevalness with the West, points to the urgency of actively engaging the present and the future, when and where possible, in our research.

That ideological commitment is at the heart of my book’s conclusion. In the section on “Interracial Heterosexuality, Homosexuality, and States of Panic,” I draw on the insights gleaned from my work on colonial interracial heterosexual relations in Ghana to think through the recent intensification of church and state-sponsored homophobia in a number of different African countries. Subjecting contemporary homophobic discourses to both comparative and historical analysis reveals them to be part of a much longer history of sexual panics visible across different parts of the continent, especially during the colonial period and continuing through today. In taking this approach, what I hoped to show is that homophobia in places like Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Uganda today does not represent an incomprehensible form of African social conservatism, a claim that inevitably leads down a slipper slope toward old tropes of African backwardness and stasis, underpinned, as they are, by the idea that Africa and modernity are incompatible. Rather, like the sexual panics that gripped their colonial predecessors, it is better understood as a symptom of deeper anxieties and social dis-ease occasioned by the crises facing the state in post-independence Africa – of which those at the forefront of this disturbing trend are unsurprisingly also those facing particularly acute crises of legitimacy.

What’s next? Where do you go from here?

I have the tremendous privilege this year of being at the Society for the Humanities at Cornell, where I’m getting started on my new book project, tentatively titled “Somatic Blackness: A History of the Body and Race-Making in Ghana.” In so many ways this is the book that I thought I would write first, so it represents a return to the foundational questions about race, identity, blackness, and the body that first captured my attention as an undergraduate study abroad student in Ghana in 1993! Wow, I really just dated myself there.

February 11, 2016

Can The Tate Britain curate a post-imperial future?

“It must be done, and England should do it” – John Everett Millais, 1874

Tate Britain’s Artist and Empire: Facing Britain’s Imperial Past exhibition catalogue opens with a foreword by the esteemed scholar of black Britain, Paul Gilroy. Britain, Paul Gilroy has argued on occasion, “remains ambivalent about its imperial past.” In the catalogue for the recent Tate Britain exhibition Artist and Empire: Facing Britain’s Imperial Past (25 November 2015 – 10 April 2016), Gilroy continues along similar lines, writing in the foreword that the British Empire “is often narrated as a simple story of civilisational clash that anticipates the diplomatic and military problems of the present. Apart from the sheer scale involved in the uncomfortable task of post-imperial evaluation, there is contemporary pressure to filter the Empire’s protracted history, to compress its expansive geography, to deny the whole, lengthy process any philosophical or cultural dimensions and to mystify its profound economic consequences.”

James Sant, “Captain Colin Mackenzie”, 1842

James Sant, “Captain Colin Mackenzie”, 1842The exhibition therefore seeks to explore the “porous” boundaries “between the exotic, the everyday, the anthropological, and the aesthetic” (per Gilroy) by way of an astonishingly vast array of visual and cultural objects produced in and collected from Britain’s overseas colonies and protectorates.

Artist and Empire is organised into six sections – Mapping and Marking, Trophies of Empire, Imperial Heroics, Power Dressing, Face to Face, and Out of Empire/Legacies of Empire. The exhibition proposes to “foreground the peoples, dramas and tragedies of Empire and their resonance in art today.” On my way through London after a conference on the fragments of American empire in Beirut, several friends and colleagues recommended I take a break from my own work on the resonance of black identity in one particular former British dominion (Egypt) and stop by the Tate instead. I’m a bit confused by what I saw.

The vast majority of artwork and objects on display consist of overwrought and lavish portraiture, typically of British imperial figures (often “cross dressed” in native ‘garb,’ as above) who are sometimes accompanied by docile, feminine, and exotic colonial subjects in the background, or kneeling adoringly beside them. Anyone familiar with the basics of Edward Said’s use of Orientalism as a theoretical lens will be unsurprised at the number of paintings that juxtapose the half-naked native with the regally uniformed British officer in a Caribbean, British North American, South Asian, or African setting.

Even when colonial subjects are the central subjects in a painting, they are still placed in orientalist arrangements that reflect British sensibilities. For example, white colonial masters paternalistically presiding over a gathering of newly civilised subjects, as in Charles Warren Malet’s 1805 portrayal of a treaty signing in Mysore. Or the East/West hybrid styling of Carlo Marochetti’s 1856 coloured bust of Duleep Singh (a gift to Prince Albert). Not to mention the beguiling primitivism in a 1784 portrait of a Polynesian chieftain’s daughter painted John Webber in the style of Venus (i.e. topless).

John Webber, “Poedua, Daughter of Orio”, 1784

John Webber, “Poedua, Daughter of Orio”, 1784The exhibition candidly discusses (more so in the catalogue but still present in the gallery) the often horrifying circumstances that enabled such scenes to be rendered on canvas, in stone, or in photograph. Poedua, the aforementioned daughter of a chief name Orio, was held hostage by James Cook in order to compel her father to allow two of Cook’s crew (gone AWOL of their own accord) to return safely. Visual renderings of kidnapped, imprisoned, or enslaved peoples unfortunate enough to encounter the British abound in the exhibition, occasionally offset by subversive art produced in situ.

An example of the resistance art on display includes brilliant Asafo flags made by Fante artists in the early twentieth century. Fante people appropriated the Union flag for use alongside images and symbols of local significance. The exhibition explains such flags are first produced to demonstrate loyalty to the British, but are eventually banned as seditious in the midst of Ghana’s struggle for independence.

Additionally, early in the exhibit, Scottish artist’s Andrew Gilbert’s installation, British Infantry Advance on Jerusalem, 4th of July, 1879, asks what would happen if the British had lost the Battle of Ulundi in 1879, rather than the Zulu army? Would they too have been put on display?

Finally, Artist and Empire closes with a nod to the resonance that British Empire has on modern (“post-colonial,” even) artistic production in Britain. The Out of Empire/Legacies of Empire room features watercolours by Rabindranath and Abanindranath Tagore, sculpture by Ronald Moody and Benedict Enwonwu, and other pieces from Donald Locke, Sonia Boyce, Judy Watson, Tony Phillips, The Singh Twin along with a number of other twentieth century and contemporary artists

Andrew Gilbert, British Infantry Advance on Jerusalem, 4th of July, 1879, 2015

Andrew Gilbert, British Infantry Advance on Jerusalem, 4th of July, 1879, 2015There is no question that what Professor Gilroy sees in Artist and Empire – a chance to “reconcile the tasks of remembering and working through Britain’s imperial past with the different labour of building its post-colonial future” – is a productive exercise in itself. But those tasks, and this labour, seem more dependent on the position of the visitor themselves than it is effectively probed in the curation and presentation of the exhibit.

Something about the clever counter-linearity of the exhibition is profoundly superficial, however. At the start of Artist and Empire, viewers are confronted with Walter Crane’s 1886 map of the imperial federation, a subtle socialist critique of commercial imperialism denoted by several visual cues common to the socialist movement in the late nineteenth century. This map re-appears, again by Andrew Gilbert (All Roads Lead to Ulundi [British Empire Map as ‘Paterson’s Camp Coffee’ Advert], 2015), at the end – a reimagining of the imperial and cartographic triumphs apparent in the colonial British artwork on display.

The effort to expose what Paul Gilroy refers to as the “disputed legacies” of British colonialism is clearly apparent in what is ultimately an illuminating glimpse at the beauty and barbarism of Britain’s imperial past. “Past,” however, may be the Tate Britain overstating Britain’s progress in its cultural, and indeed political, investments.

Walter Crane, Imperial Federation:Map Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886

Walter Crane, Imperial Federation:Map Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886![Andrew Gilbert, All Roads Lead to Ulundi [British Empire Map as ‘Paterson’s Camp Coffee’ Advert], 2015](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1455339563i/18088999._SX540_.jpg) Andrew Gilbert, “All Roads Lead to Ulundi” [British Empire Map as ‘Paterson’s Camp Coffee’ Advert], 2015

Andrew Gilbert, “All Roads Lead to Ulundi” [British Empire Map as ‘Paterson’s Camp Coffee’ Advert], 2015I frequently wondered about the prior ownership and means of acquisition of many objects on display when confronted with a Maori quarterstaff (Taiaha) and Kainaiwa war bonnet. Both of these sacred objects appear with white men in other contexts: the Taiaha surfaces again in painting, propped beside Sir Joseph Banks in a 1771 portrait by Benjamin West.

Tate Britain is not unique among other cultural, national institutions in the Western hemisphere for excluding mention that the artefacts it holds (and displays) are stolen goods. But my question upon viewing the exhibition is where, in Artist and Empire, does an acknowledgement of these items and their legal precarity appear? Does such an admission of the spoils of empire threaten, as with the glaring lack (with the exception of one T.E. Lawrence and his “friend,” the Emir Feisal) of the Arab world in the galleries*, the ‘innocent’ nostalgia for empire that Britain continues to clutch onto?

Augustus John, Colonel T.E. Lawrence and The Emir Feisal, 1919

Augustus John, Colonel T.E. Lawrence and The Emir Feisal, 1919I am not entirely sure that Artist and Empire “faces” anything at all. I appreciate its efforts to query the roots of British identity, particularly as Alison Smith notes in the catalogue, in light of this “moment in crisis in British identity.” This exhibition is certainly a step above the far less critical The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting, put on by Tate Britain in 2008. However, its tepid historicizing of colonial brutality – and complete silence on contemporary unevenness of labour, production, and ownership in both the arts and in British society at large – renders the exhibit one of many perfunctory exercises to purge a shallow sense of guilt without addressing the very real and material logics that sustain ongoing, structural inequalities within and outside of Britain.

*Everyone I spoke to about this exhibition later had the same question: Where the hell are the Arabs, Tate Britain?

February 10, 2016

How to say Joseph Kony’s name

Between 21 and 27 January, far away from the International Criminal Court in The Hague, the small town of Gulu in the northern region of Uganda was engrossed in the confirmation of charges hearing for alleged rebel commander Dominic Ongwen. It is one of the few public criminal proceedings for crimes committed during the 20 year Lord’s Resistance Army-Ugandan government war, so when public screenings of the hearing were organized, people came in their numbers to see it for themselves.

On the first day, an ICC lawyer began the prosecution’s opening by outlining the war and, in particular, the role LRA leader Joseph Kony played in it. As he made his presentation, there were whispers among the people gathered in the screening hall. A few people were confused by the prosecutor’s anglicized pronunciation of the names of northern Ugandan people and places which made some of what he was saying difficult for them to follow. One mispronunciation that stood out was the name Kony.

Following mass international coverage of the war, Joseph Kony has become one of the most well-known Ugandans in the world – famous, in particular, for abducting young children to serve in his army and for the gruesome ways his forces mutilated and killed civilians. In 2012, an eponymous campaign by Invisible Children brought his name to even more front pages. (In fact, Invisible Children’s goal was to “Make Kony famous.”) That campaign was challenged by many for presenting a simplified message about the war. So it comes as a surprise to many people here in Northern Uganda that in spite of this many still cannot say his name and in some cases, actually advise others to pronounce it as the prosecutor initially did, “Coney, like Coney Island.” The word kony is actually the Luo word for “help.” It is only one syllable and is not that difficult to say with some effort.

Complaining about the pronunciation of a name probably seems petty but it actually speaks to a larger issue: how detached people in and outside of Uganda are to the North’s experiences. Given how ethnically, politically and economically divided Uganda is today, this is especially real. There is stigma towards people from the lesser developed North by people living in the South, with them labeled as killers, cannibals or Kony’s name as insults. Politics rarely touches on reparative mechanisms for victims of war here and when it does, it takes too long (the passing of a government policy meant to “address justice, accountability and reconciliation needs of post conflict Uganda” has lagged for years).

When I tweeted mine and others in Gulu’s reaction to the opening presentation, I was met with resistance from fellow Ugandans who felt the tweet was making a big deal over nothing. Part of me agrees – how Joseph Kony’s last name is pronounced does not seem that important when we’re dealing with the pre-trial hearing for someone that is charged with 70 counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes. On the other hand, one realizes that over the past ten years northern Uganda, and in particular Gulu, has been welcome to numerous foreign researchers intent on gaining expertise on the LRA war, international agencies eager to gain success stories from their contributions to addressing its impact, and even Ugandan politicians playing on the hopes of the war’s survivors to gain support. Now prosecutors at the ICC are working to ensure the trial of Dominic Ongwen, someone who is alleged to have carried out Kony’s orders. One would assume that the process of exploring the dynamics of this war would have involved numerous visits to the region and interaction with the people here listening to them express their views. And while doing this they would have, in theory, noticed that no one says anything remotely close to Coney, right?

Through Ongwen’s case the world has said that it wants to provide justice for survivors of the war in northern Uganda. To do this it is hugely important to demystify the simplistic and sometimes misinformed narratives that often surround the war and its effects. Demonstrating basic knowledge about a central figure in the war may not provide all the solutions, but it’s a start. Fortunately it seems that the people at the ICC agree: seven days after the hearing began, while making his closing remarks the prosecution lawyer made a conscious effort to say Kony’s name correctly, often apologizing and correcting himself when he mistakenly said coney. Perhaps the ICC isn’t so far away, after all.

February 9, 2016

Africa is a Radio: Episode #15 – World Carnival 2016 Special!

The first Africa is a Radio episode of 2016 goes to Carnival with special guests Hipsters Don’t Dance! This month we run down some of the sounds of the World Carnival sound from Trinidad to Rio to Lagos and back!

Tracklist

Samito – Tiku la Hina

Baiana System – Playsom

Buju Banton – Champion (Maga Bo Remix)

Angela Hunte – Mon Bon Ami

Machel Montano & Timaya – Better Than Them (Jambe-An Riddim)

Runtown & Walshy Fire – Bend Down Pause Remix ft Wizkid & Machel Montano

Olatunji – Oh Yay

Patoranking – My Woman, My Everything… (feat. Wandecoal)

Banda Vingadora – Metralhadora

Delano – Devagarinho

Eddy Lover – Baja Pantalones feat. Aldo Ranks, JR Ranks & Mach & Daddy

Wizkid – Final (Baba Nla)

Pat Thomas & Kwashibu Area Band – Amaehu

Our Ivanka, our America: a story of Latino immigrants

To the family she is just “Ivanka.” Not “Ivanka Trump,” not “Miss Trump”—simply “Ivanka.” As if the millionaire’s daughter and my family in New York of Latin American immigrants were old friends. In some way they are.

Some years ago, my mother told me on the phone that my cousin Marcela—who has been living in the States for almost ten years but only two years ago became a legal citizen—was working for Ivanka. “Who’s that?”, I asked my mother – to which she replied, indignant: “Well, Ivanka!”

Last year, as I was planning a visit to the family in Jackson Heights, their bustling neighborhood in Queens, my mother called to tell me that if I wanted to see another member of the family—whose name I should better not mention here, since after twenty years in New York he is still an “illegal”—I should change my route, because, “as you know” (I didn’t) “on Sundays he is with Ivanka.” That meant that he was working for her in one of the luxury stores she owns.

Actually, none of us has ever spoken to Ivanka in person. However, the word “Ivanka” has a very special meaning for my family. For us, the mere mention of the name reminds us that those of us who went to “America”—a word that most “Americans” use but no Latin American does—have, somehow, made it there.

Almost half of my family on my mother’s side left Colombia betweenen the late 1990s and the early 2000s for New York, New Jersey, and other cities along the East Coast of the United States. First that relative whose name must not be spoken, then three of my mother’s six younger siblings—uncles Pablo, Fernando, and Gonzalo—and, finally, cousin Marcela, who is two years younger than me.

They are part of the tremendous exodus happening in Latin America since the 1970s. Due to the follow-up immigration of partners and children, some marriages and the birth of a couple of sons and daughters, the five original relatives have built a vast extended family, which today is indeed bigger than the one that stayed in Colombia. Their story is that of millions of others. So-called “Hispanics” are nowadays the largest ethnic minority in the United States. Around 54 million people, 17 percent of the total U.S. population, have a Latin American background. In 2060 they will account for 31 percent.

Most of the approximately eleven million people that live and work in the United States as illegal immigrants are Latin Americans. I have no idea about what Ivanka makes of that. My cousin Marcela, in any case, does not want to accuse her of anything. Usually, when I talk to Marcela I get the feeling that she, in general, does not like to talk in a negative way about other people.

Marcela went to New York when she could not find work after getting her degree in Psychology in our city, Bogotá. When she still was an illegal alien she worked for almost three years as a clerk in one of Ivanka’s jewelry stores. At times she was responsible for the transportation of jewelry worth thousands of dollars, she told me recently. Aside from the meager salary, which was her final reason to quit, Marcela said this experience was a quite positive one. “Ivanka seemed like a good, polite person. Of course, I only saw her twice. But anyway, she didn’t seem to be arrogant,” Marcela told me in the timid way in which uses to answer to my questions every time we talk about her life in New York.

What Ivanka’s father, Donald Trump, the magnate and presidential pre-candidate for the Republican Party, thinks about Latinos in the United States (the word he uses to talk about them is “Mexicans”), and especially about those who are illegal, became clear some time ago. In one of his explosive speeches in the summer of last year, Trump famously said that when Mexico “sends its people, they’re not sending the best”. They’re sending “people that have lots of problems and they’re bringing those problems. They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

To avoid a nasty generalization, Trump considerately added: “Some, I assume, are good people.” To this day, Trump’s public statements about Latinos—as well as about a quite long list of other ethnic and religious minorities—have remained along similar lines.

After Trump’s statements, the U.S. Congressional Research Service noted that the majority of illegal immigrants behave quite differently; crime rates within the first generation of immigrants are lower than in the rest of the population.

In an open letter to Trump, a young Mexican woman wrote that her father, who has lived illegally in the United States for years, and who “has worked 5-6 days a week since I was a child and I’ve never heard him complain about it one time,” was the greatest man that she knew.

Latin American politicians, artists and a starred chef from Spain criticized the billionaire. However, polls show that for many voters Trump appears as the best Republican candidate. I ask my cousin Marcela what she thinks of Donald Trump. Her answer to this question is slightly more vehement than the others. “I think that he has no idea what he is talking about,” she says. “Maybe he does not know that almost every waiter, every cook, every cleaning person in the restaurants and hotels he frequents is a Latino who probably was or still is illegal.”

I ask whether she believes that our emigrated family belongs to “the best” of our country. “I don’t think so!” she replies with a laugh. “But we are people who came here to live a decent life, and whose only dream is being legal. Of course, bad immigrants do exist. And the problem is that all of us are being discriminated against because of those few. That is just not right. We came here to work.”

My relatives belonged to Colombia’s lower-middle-class, which usually holds hard work, cleanliness, respectability, and family values in high regard. They have built a productive life in the U.S. And, like a huge number of immigrants in the States, they send money back to Colombia almost every week.

That’s how Marcela paid back the debts her mother had incurred to send her to college. None of my relatives has ever committed a crime (except, of course, being illegal themselves) and they would very probably perceive any trouble with the law as a disgrace for the whole family. Despite the common Colombian stereotype, none of them has ever been involved with drugs—except for Uncle Pablo, of course.

As a young man, Pablo was an notorious stoner who built his joints in such a masterly manner that his buddies used to call him “the architect.” Once I asked him about his infamous past. He told me, still ashamed, that he had lost many years to drugs, “and caused your grandmother many headaches.” But thirty years ago he found Jesus and became a pastor in one of the evangelical churches born in Tennessee or Alabama and that are now flooding all of Latin America. In the early 1990s Pablo and his wife were ordered by their church to go to Philadelphia and save the souls of Latinos. Today they live in Atlantic City with two daughters in college.

My other uncles emigrated for more mundane reasons. Fernando—known in the family for his calm temper and his funny dance moves when he has had something to drink—worked as a cab driver in Bogotá for years. One day he saw himself in his constantly vacant cab, surrounded by countless other vacant cabs and their frustrated drivers who had fled to the capital to escape the violence and lack of perspective in their provinces.

His two sons were in high school back then. Fifteen years ago, when I visited my family in New York for the first time, Fernando, still illegal at that time, had three jobs: from five to one he worked for a demolition company in New Jersey; from three to ten at night he worked at a recycling yard in New York; and almost every weekend he worked in a factory producing radiators. Today one of his sons lives and works in Newark, the other one studies in Bogotá. Fernando’s marriage, however, did not survive the long distance.

Uncle Gonzalo—a neat, diligent, and sometimes too serious man who is always the first one to congratulate me on my birthday every year and has the peculiar habit to tell waiters how to set the table correctly—was doing well as a bank employee in Bogotá. In the late 1980s he was laid off as part of a mass dismissal. He started working for a construction company that went bankrupt. So he opened a restaurant and then a bar—both failed.

One of his daughters was in college, the other one just born. In the first years after his arrival, Gonzalo—who was always proud of having an account with the Chase Manhattan Bank, which one can get as an illegal—worked as help in the kitchen of a yacht club on Long Island. Today he is the head waiter there. Both his daughters live close to New York; the elder married a Jewish lawyer some years ago and has now three children, the younger is in high school. Gonzalo’s marriage however, did not survive the long distance either.

My cousin Marcela tells me that getting the chance to work for Ivanka came “as a kind of liberation” from the first hard jobs, from cleaning toilets, from feeling like an extraterrestrial in the United States.

At first, she remembers, she was afraid to go to Manhattan: “I barely spoke English and all these people seemed so important! But it got better with time.” I ask how is it even possible for an illegal person to find a job. “That’s easy. You always know someone who knows where people are needed.” And how come they let you work? “Well, we are the perfect workers. We get minor salaries and if someone finds out that we are working with fake papers we get fired right away. After that the next immigrant is waiting in line and the whole process starts over.”