Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 312

February 25, 2016

After #MuseveniDecides

This past week Edward Ssebuwufu opened his Friday evening radio show his usual music, a Ugandan pop song simply titled “Africa.” The lyrics are a wry commentary on the politics of his native nation—“who can buy our country, we’ve put it up for sale” — and for Ssebuwufu they had once again proven to be prophetic. It was February 19th, the day after Uganda held presidential elections, and despite allegations of corruption and fraud it appeared that Yoweri Museveni would be back for a fifth term in office.

Ssebuwufu was not actually in Uganda last week, nor were most of his listeners. The show was on Radio Uganda Boston, which broadcasts worldwide on the Internet from a studio in Waltham, Massachusetts—a historic mill city in the northeast United States that has become a major center for the Ugandan diaspora.

But while the audience is scattered, their attention and sentiments are not. Once Ssebuwufu took his place behind the broadcast desk and announced the latest election figures, he opened the phone lines — punching two buttons on the mixing board to bring the first guest on air. It was a man in Norway asking which polling centers were reporting Museveni’s purported victory. A second caller in Maryland wanted to know what could be done next to challenge the results. A third claimed that the government was just waiting for everyone to go to sleep so that they could swap the numbers in Museveni’s favor. According to Ssebuwufu — who had been at the station for seven hours already that day — this has been the general tone in the diaspora: frustration, and disappointment.

And not without good reason: the elections in Uganda this past week have been mired by irregularities. Radio stations were censored and social media blocked; opposition candidates were repeatedly arrested and protests quelled while state funds fed the incumbent’s campaign; and reports of vote-buying and pre-checked ballots led the US State Department to announce: “The Ugandan People deserve better.”

Despite Museveni’s history of election tampering many in the diaspora had hoped that this time would be different. As Ssebuwufu describes it, that hope is a personal one. “If you ask any Ugandan, they will tell you: ‘I am here, I’m working—one time I want to go back home.’ That means that most of the Ugandans are living outside Uganda not because they want to, but because the situation back home is not good.” For now at least, that situation is not likely to change.

There was a lot of disappointment in Waltham on February 19. Freddie Kibuuka works the counter at Karibu, a Ugandan restaurant just off the city’s main drag. He is 29, which means that he has only known one president in his lifetime. “We felt this was our time to take power. We thought 30 years is too much.” Kibuuka spoke softly, the sense of defeat showing on his face.

At one of the tables, John Nsubuga expressed a more cynical view. Gesturing with a paper coffee cup, he announced: “You can never vote them out, only fight them out.” I heard a similar sentiment next door, where Gerald Mutiaba works as an accountant and manages his own Internet radio station. “I don’t know why people got so surprised when he came out to be the winner.”

Mutiaba placed Museveni’s reign in a larger context: “It is a trend, it has been happening. Look at Mugabe, he did it, Gaddafi did it, Saddam … Maybe we need to learn a lot from history, because it tends to repeat itself.”

But whether surprised or resigned, hopeful or skeptical, everyone I met was also concerned for Uganda’s stability, and wanted calm, despite the injustice. Ssebuwufu told me that he has been closing out his radio show with a different song: a version of “Give Peace A Chance” released last year by the aging South African singer Yvonne Chaka Chaka.

Ssebuwufu’s message to his listeners—whether in Uganda or the diaspora—is simple: “We are Ugandans. This is a process which comes every five years. It comes and it goes.” He adds: “Please don’t fight each other. I think we’ve walked that path for so long, enough is enough.”

The Friday night broadcast wrapped up at 9:30pm. Seven thousand miles away the sun was about to rise over Kampala. That immense distance is not as far as it once was, as Ssebuwufu’s program illustrates. The election unfolded in real time—so even though diasporic Ugandans could not vote from abroad, they could still follow official announcements, instantly share reports with relatives, and air their own views.

I had previously spent time at Radio Uganda Boston researching their music programming and its ability to connect the stations’ dispersed listeners, but coming back during the election season really drew out for me the extent to which Internet technology affects the meaning, experience and limits of being in the diaspora.

The very concept of a diaspora has always been defined in part by the existence of a shared homeland—whether real or imagined—that is preserved as a memory or myth. But for Ssebuwufu’s generation Uganda is much more than a myth; it’s a reality that they can see, hear, engage, and influence. And yet, they are still removed—protected to some degree, and also powerless; it’s still “back home” as Ssebuwufu likes to say. The election seemed to highlight that paradox of being both intimately connected and physically separated. Ssebuwufu’s listeners couldn’t take to the streets and most could not even cast ballots, so instead they called in and asked him: “What can be done next?”

“What can I do?”

Ssebuwufu didn’t have all the answers. There wasn’t much he could do either, except to keep broadcasting, to give his community an outlet for their frustration, and to hope for the best. “We are just waiting to see what happens, and we keep on praying that it’s not so bad.”

February 24, 2016

Abdi Latif Ega and the rejection of the ‘African’ novel

Abdi Latif Ega in Harlem. Credit: Zachary Rosen

Abdi Latif Ega in Harlem. Credit: Zachary RosenIt’s not an uncommon sight to find Abdi Latif Ega, cup of steaming tea in hand, strolling through the streets of Harlem in the afternoon sun, stopping to converse with a range of acquaintances along the way. Ega, a contributor to Africa is a Country, is a Somali-American novelist whose first book Guban breathes life into Somalia’s vast and intricate cultural landscape through the journeys of its characters. It’s a refreshing contrast to the barbaric representations Somalia frequently experiences from the Western media.

Now in the process of writing his second novel, Musa, Ega has launched an Indiegogo campaign to support the creative production of the book. More than just a writer, Ega embraces being a cultural worker who subverts the pigeonholing of African narratives in the mainstream publishing industry by self-publishing his work. In doing so, his writing transcends limitation by not being beholden to what a publisher deems is the marketability of Somali and immigrant lives.

Consider contributing to this fiercely independent thinker’s campaign to create Musa and read our interview below where Ega speaks about creating complex characters, the relationship of images to creative writing and the state of African literature today.

***

What kinds of issues move you to write?

My writing comes from being moved to say something about injustice. It’s almost reactionary to it, as a reflex to it. There is a colossal, almost belligerent continuum through history of the elite who everything seems to be working for at the cost of most of humanity. So I don’t see myself particularly as a writer, but part of many things that involve culture; a cultural worker meaning averse to the idea that the writer is put on this pedestal on the back of a book where no one encounters him unless they come to an event or something like that. A cultural worker is a part of the village that creates to enhance the village. In essence as a cultural worker there’s some fundamental injustice or wrong narrative that I’m trying to amend, represent, change; there’s activism and it’s sort of like “writing is fighting” which Ismael Reed says all the time.

When people are coming to appreciate a collection of writing, they’re often invested in the lives of the characters. How do you conceive of your characters? And, how do they accomplish the visions that you have for your stories?

Well I think it’s not difficult for me to find characters. My characters are generally composites, sometimes caricatures of maybe 40 or 50 different types of traits. Perhaps one character can encompass three or four different kinds of bad traits that you feel in one person, like greed and avarice. Sometimes it’s toned down, sometimes exaggerated, but nonetheless a lot of the ingredients come from things that I have seen or intuitively add.

So they’re not alien to our existential, but at the same time the empty page has its own magic and sometimes you find that a character will veer off and do other things. At that point the plot will work as a harness to keep them in a certain vision so that they don’t run away completely from what it is you want to say. So there’s many ways where the character is unknown to you and they speak to you not necessarily by talking, but by inserting themselves in the work. I generally see such; shadows, silhouettes. A lot of it is also in the subconscious, that comes into play; the excavation of the archive.

Things we don’t remember that are locked in our subconscious and we need to delve into that place where the story will open up to you. That’s why it’s an excavation.

So as you’re excavating the archive, do you find yourself in conversation with writers whose work you have been influenced by?

Yeah, I think we’re somewhat collections of what we’ve read. I believe the writing is a legitimate son, or daughter of reading. So you are influenced by many people and certain lines and how that previous author did a certain thing in a description. And this doesn’t really revolve only around writers but it also revolves around poets, who are also writers in another form, musicians, artists, certain paintings you have seen or photographs or movies that capitivate your imagery.

How do photographs in particular move you? How do you translate your experience of looking at images into your writing?

Well, I think it relates in the sense of the reality of the photographs. There’s nothing closer to reality in that moment, that second or two seconds, it’s still life. And so when you’re writing an entire story from a period which is historic, you’re also in some ways creating a much larger photograph with much more detail.

So images are some of the ingredients from which the story coalesces. It seems when the reader experiences that story, they’re also recreating those images again on their own. Images are reborn then through the imaginative process of reading.

It’s a dream sequence. That’s why sometimes your imagination looks better than the movie that’s made of the book because your imagination can be so much more fascinating than what the director decided.

So what is Musa, in your new work, fighting for?

Musa is a spoof on white supremacy. It’s called Musa after the prophet Moses and it deals with a lot themes; racism, institutional marginalization of immigrants particularly of African descent, which I am. The problems of immigration; which means paperwork, legalities during, before and after the war on terror, and how one pays into the capitalist coffers of the system. There’s a duration of eight years or nine years where you might not be able to visit your family or leave the country. Those are definitely the different sides of this which have a lot of problems. I want to represent myself and the activism behind this is that there is a particular story that has not been done to even approximate the colorful lives that we’ve lived. I’m not a son of a diplomat or anything like that. I’m not from the upper class so this is a very different approach. I don’t think any experience is less than the other, but I think the question of representation, where one becomes the representative of everybody, is the issue.

You seem to also take a strong stance against more traditional publishing houses and a style of writing that some writers may perform to be published. There’s a sense that you are not interested in fitting that corporate mold. So what is your relationship with the publishing world?

My relationship is from my previous work, Guban for which I got a traditional agent.

The problem then was that what mainstream publishing was excited to publish were things in my view that were demeaning to African personalities, and particularly the image of Africa. They were more interested in producing works that had a lot to do with child soldiers, works that have something to do with pornographic famine, poverty, violence those things. In the case of Somalia it was all about warlords, pirates and terrorists. Guban is basically a response to all of that caricature and demeaning of the African personality. This is the 21st century, it is not Treasure Island. This marriage between mainstream publishing and media has often determined the things being published. So when Guban started off to actually pose a counter-narrative to these ignoble caricatures of African people, it didn’t fit what people were looking for. That is the relationship between me and mainstream publishing.

I think that [self-publishing] is something that is becoming more and more available. The people who are doing literally criticism whether they are academics or not are going through this amnesia as if it doesn’t exist. People are buying and reading more than in any other time, works that are independently published. Imagine a place like The New York Times will not review a self-published book. How realistic is that in this day and age? My experience has taught me that I think nothing in my life has been mainstream. I’m happy to put out my own work, in that I have no regrets over the work itself. There’s a certain amount of integrity in the work. That it is aligned to my politics, it’s aligned to the things that I want to speak about and I am not necessarily changing anything to pander to any market place.

You’ve alluded to corporate media feeling very comfortable with boxes and one of those contested boxes is the mythical beast of ‘African writing’. Over the last few years there’s been a lot of conversation about ‘African writing’ means.

Some writers and artists of African heritage want to say their works are art first and then ‘African.’ They don’t want to be put on the African shelf, they want to be put alphabetical. Another faction claims their ancestry and speaks of how they define for themselves what an ‘African’ experience can be. Where do you see this conversation now?

There’s a lot of projection onto the African writer in that there’s always someone trying to define what they should be doing. I think there’s an inordinate amount of paternalism that is directed towards African writing in general. The second thing is there are sort of hardened divisions between orality and also a simplistic view of African writing as beginning with Heinemann [African Writer Series], which is textual. How do you look at something in the Somali language, which is oral, or in any other language which is African and disassociate that literature with its Africanness? That’s a very difficult proposition. You cannot say a book in Somali, written from Somali poetry that comes from a long line of centuries, is not Somali. It’s difficult to remove yourself. But the appraisal of it is where the problem is. How, for example, somebody who’s writing in Chicago, all of a sudden becomes a writer who’s universal, rather than provincial and no one says this is not a universal work? I think that’s also where the problem is linked to white supremacy in that, certain literatures are not considered universal as the European or the Western one. In other words, the human condition seems to be located only in the North or the West. If all was fair and there were no limitations of universality as a writer, then of course there would be no problem. So, I don’t think it’s a negation of being an African, I think it’s a negation of being thought of as less than any writer from any country or continent. It’s a rejection of limitation.

February 23, 2016

The Free State

There are so many lessons from (and horrors) from the violence against black students at South Africa’s University of the Free State (for background, see here) but here are my own observations:

(1) While movements like #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall have been powerful and poetic, the willingness by white Afrikaner youth at theUniversity of the Free State (UFS) to resort to brute violence to protect their interests and the level of organization displayed (availability of weapons, etcetera) suggests that the kind of decentralized, non-hierarchical, diffused, and seemingly “leaderless” mode of organization may well be inadequate for unsettling the much more organized economic and near-paramilitary concern that has dared to make itself visible in a public higher education institution 22 years after the fall of apartheid. And this is a broader issue concerning who, politically, fully demilitarized as a concession to democracy and who disbanded structures of local and grassroots organization and who did not. I think UFS shows us who’s been waiting and preparing for the moment of violent racial confrontation in South Africa and who will not be swayed by the poetics of an alternative mode of engagement

(2) The rise of#RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall, as I argued a few months ago, although necessary, its location in Cape Town (like at UCT) and Johannesburg (Wits University) and at Rhodes University not only eclipsed the ongoing struggles of poorer students at schools (the former technikons and “historically black universities”) like Vaal University of Technology, Durban University of Technology, Tswane University of Technology, but also the struggles of students in the vocational college sector, who have been raising issues of financial and academic exclusion for years. The bodies, lives, and experiences of Wits University and UCT students were ‘sanctified’ in ways that the bodies and hardships of poorer students in the countries post-school system were not.

(3) Linked to the above (and here the parallels with the French peasantry in the wake of the French Revolution are instructive), what UFS shows us is that the shoes that have done the disproportionate and possibly more sordid pinching of the toes of black students in South Africa’s universities has not, in fact, been at the leafy Cape Towns and and Johannesburg schools, but has remained largely unchanged and unchallenged in the quiet enclaves where the level and type of racism backed by the ever-present threat of force and violence has been much more acute. Like the French peasants, who became the squeakiest wheel in Europe, lending their weight to revolutionary fervor, the students at Cape Town, Grahamstown, and Johannesburg, as we can see, have hardly had to live in a context of such abiding physical threat and they could in fact be as vocal (and daring) as what they have been precisely because the nature of their beast operates at the level of symbolic and structural violence, not sheer force. Like the French peasants, these students ( and this is not intended to diminish the validity and urgency of their cause) can hardly be said to be the most oppressed.

(4) Finally, what’s emerged at UFS can’t be addressed by the UFS’s Vice Chancellor Jonathan Jansen or by the students and I wonder even whether or not it can be resolved by means other than violence and greater force. Those images of black students volleyed between the kicks of burly white boys have stirred a different kind of feeling inside me, and one that I would not have expected to experience 22 years after democracy. This takes me back to Point 1 above: who demilitarized and did so far too soon?

February 22, 2016

Football and power in Colombia: in bed since 1948

When thirty years ago Noemí Sanín – then Minister of Communications of Colombia – asked the directors of the main news media outlets in the country to stop their reports from the burning Palace of Justice and, instead, to broadcast a boring Millonarios-Unión Magdalena game, she was not being innovative. Football has been, throughout the country’s political history, an uncontested panic button for those in power.

We only have to remember the origin of the professionalization of Football in Colombia in 1948. A great deal of it was due to the necessity to give the people a civilized, weekly entertainment to ease the atmosphere that had been heating up since the murder of presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán — and the resulting riots on April 9th of that year.

So what did the government do? It allowed team owners to use the state’s infrastructure, and sold them dollars at a preferential rate, so the professional tournament could begin by August. Months later, news arrived of the strike in Argentina, which opened the door to poach star players from that country’s teams. Thanks to the dollars given by the state, along with other resources, Di Stéfano, Pedernera, Rial, Pontoni and others arrived to Colombian football. Ours was an openly pirate league between 1949 and 1953, which meant, among other things, that clubs were created without enough assets to face lean periods.

Years later, in 1984 when the Minister of Justice Rodrigo Lara Bonilla was murdered by narcos, the Belisario Betancur government wanted to show its claws, so said it would take steps to eradicate the mafia influence in many areas, including sport. But they were only words that didn’t become facts. Especially in an era when, as we now know, drug cartels controlled directly or indirectly a good amount of the Colombian league teams.

Five years later, on Friday August 18th, 1989, presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán was murdered. The qualifiers for the 1990 World Cup in Italy were scheduled to start the following Sunday in Barranquilla. Francisco Maturana’s Colombia was to play Ecuador, and many thought that the game should be played as a balm to calm the pain of loosing the president. It was out of the question to mention the paradox that that National Team was made up of players that had reached a superlative level thanks to the investments from “controversial businessmen,” who were the same people that had fueled the death machine that caused the end of Galán.

It took the murder of a referee, Álvaro Ortega, in Medellín weeks later for the government to feel that they had enough, and the Colombian league of 1989 was cancelled. Criticisms poured in from everywhere. Maybe the fiercest one came from Francisco Maturana, who said in his biography, Hombre Pacho, that Football and politics were separate issues, and that the show had to go on. A plethora of good intentions followed, along with the announcement of requirements each team would have to meet to guarantee legality and transparency. But good intentions were just good intentions. Months later, the 1990 tournament began, and the same people were still doing the same things.

There were other milestones. The 2001 Copa América “of peace,” was used to resuscitate the agonizing peace talks with the Farc guerrilla in El Caguán. Up until ten days before its start it was uncertain if the tournament would take place. This was due to a series of terrorist attacks happening around the country, in particular in Bogotá. Years later, Vice President Francisco Santos thought that there would be nothing like a World Cup to introduce Colombia as the Eden-like society we would become, thanks to President Álvaro Uribe’s seguridad democrática policies. And so the U-20 World Cup came to Colombia in 2011, a tournament for which the government invested 210,000 million pesos (equivalent then to 112 million dollars) to, mostly rebuild VIP areas in stadiums, including elevators that could lift the prominent bellies of FIFA executives. All of this was done, let’s not forget, by order of Jack Warner, the former Concacaf head now in jail. And how could we forget that Angelino Garzón – the first Juan Manuel Santos Vice President – helped to secure a 50,000 million pesos loan (25 million dollars) in 2010 from the Financial Development Fund Findeter to save the Colombian league teams. Would he have done the same for pig farmers?

And between milestones, there were also those little details that guarantee strength in a relationship: invitations from the world of Football to the officers responsible for the surveillance and control of teams; presidents that welcomed teams under legal investigation into their offices; high-ranking officers that would intercede so that an extradition order doesn’t ruin their beloved toy; and honorable court justices that let slip legal suits that seek to protect fundamental rights, so they don’t lose on ticket sales, while they were part of Dimayor – the Colombian football governing body.

It is a sick relationship, but very few, not even fans, want to be aware of it. Just like sausages, no one wants to know what are their team’s victories made of. Opinion leaders showcase high ethical standards in their usual platforms, but in the stadium they are much more flexible.

The biggest problem is that someone’s sons are the ones effected by this arrangement. They are footballers, in particular those of low or medium profiles, that when their rights are not respected, and they ask the state for assistance, they are met with the message that the corresponding officer is on a trip to Barranquilla, invited by the Colombian Football Federation.

This article originally appeared in Spanish in FútbolRed and is translated here with permission.

February 21, 2016

It’s the economy stupid, N°2

Here’s episode 2 in our new series. If you missed the first instalment and the rationale behind, click here.

(1) Suppose you are a poor country that also has wide-scale corruption, what should you do first? Target scarce resources to fight corruption and hope that growth follows thereafter or grow first and then hope that corruption declines? It appears that the empirical evidence doesn’t give much guidance on what to do. This from Bjorn Lomborg’s Project Syndicate column this past week: “[E]xperts do not agree on whether good governance or development should come first. Historically, good institutions such as secure property rights and the rule of law were seen as the single most important factor driving variation in the wealth of countries, and more corruption was associated with lower growth. But more recent analyses have shown that it could just as easily be that higher wealth and economic growth lead to better governance.”

(2) Even more, conscious efforts at fighting corruption are hardly successful. This again from Lomborg: “A study of 80 countries where the World Bank tried to reduce corruption revealed improvement in 39%, but deterioration in 25%. More disturbing is that all of the countries the World Bank didn’t help had similar success and failure rates – suggesting that the Bank’s programs made no difference.”

(3) More on corruption: A few weeks ago, Transparency International released their 2015 Corruption Perceptions Index report and African countries were singled out as being some of the most corrupt in the world. This is not to deny that corruption is a big issue on the continent, just as its more sophisticated nature is a big issue in Western countries. But what all this discussion neglects to mention is that there is currently a scholarly debate as to whether the Corruption Perceptions Index tells us anything meaningful about the extent of corruption, particularly in the developing world. (We also wrote about this in 2010).

(4) Is all this focus on corruption a red herring? A sort-of “Anglo-American fetish”? After all, who can confidently say corruption was nil when the West was rising?

(5) We were disturbed to learn that Malawi has a 60 year old Colonial-era Tax Treaty with the U.K. that makes it easy for U.K. companies to limit their tax obligations in Malawi. The treaty was “negotiated” in 1955 when Malawi was not even Malawi yet. Malawi (or Nyasaland, as it was known then) was represented in the negotiations, not by a Malawian, but by Geoffrey Francis Taylor Colby, a U.K. appointed Governor of Nyasaland. You can’t make this stuff up.

(6) Back in 2007, the cognoscenti were lauding Ghana as the next African star performer. Ghana then followed this up by going an international borrowing binge. It turns out that much of Ghana’s performance was built on pillars of sand, well sort of.

(7) Over at the LSE Africa Blog was this thought-provoking piece on the informal sector in Africa. The piece argues that the informal sector is important for Africa’s development. Whereas we don’t deny that thinking about the informal sector should be part and parcel of a broad development strategy on the continent, we are a bit apprehensive about the potential for the sector on its own to drive self-sustaining growth. We wrote about this last year.

(8) Another one, from the LSE Africa Blog about the “brain drain” in Africa.

(9) Here’s Dani Rodrik talking about some of the adverse effects of so-called “Free Trade” Agreements.

(10) Talking about the adverse effects of free trade, there appears, sadly, to be a link between free trade and mortality.

(11) Who knew that China, a big creditor to the world, was itself heavily indebted.

(12) Finally, Admiral Ncube, a Zimbabwean aid worker has penned this brilliant poem on aid work as an insult to the poor. An excerpt:

Experts have risen who have not been poor

Whose studies and surveys bring no change

Whose experiments and pilots insult the poor

Whose terms and concepts, tools always change

An industry of sorts – an insult to the poor.

The part of Ncube’s poem talking about “experiments and pilots” as insults to the poor, reminded us of this story from last year on a most indignifying economic experiment conducted in villages in Western Kenya. We weren’t pleased.

February 19, 2016

The Fire This Time

While the fight for the 0% fee increase commanded an amazing breadth of support, the subsequent, more radical trajectory of the South African student movement is jilting many sympathizers – including progressives (if you have South African friends, just check your Facebook feed.) This was certainly the case with the latest action at UCT – in which students erected a shack on campus and burnt colonial, artwork amidst a brutal crackdown by police and private security. While the “Fuck Whites” t-shirt campaign at Wits University only got a few people exercised, the sight of paintings going up in flames has many more debating.

Social media was alight with complaints that students had gone too far, that they were squandering sympathy and that such actions undermined their cause. The latter in particular is a common form of outside commentary: assuming a firm understanding of the students’ long-term goals and the best way of reaching them, and then adjudicating every event in purely tactical terms–whether or not it furthers the cause and thus whether or not it is justified.

It’s quite natural for the Left and for the public in general to debate and prognosticate over movements in which the whole society has a stake. But the above is not a helpful way of doing so. In the first place, it seems premised on erasing the context in which events unfold. It treats the students as a unitary agent – freely choosing its own path and thus morally culpable for all outcomes and externalities. This does violence to the reality of a decentralized, horizontally organized, mass movement – one that erupted suddenly out of wellsprings of suppressed rage, and that has shifted and evolved in response to repression and subversion. Like all radical movements, methods are not always clean or neatly pre-figurative of new ideals, nor should they be. For activists on the ground it’s imperative to fight for them to be aligned with ultimate aims. But for those outside, holding a moral compass to everything that transpires, rather than analyzing real distributions of power and calling attention to the disproportionate violence of the state, is not the course of someone genuinely sympathetic to the aspirations of the movement.

The most unhinged critics suggested a slippery slope from the burning of paintings to Nazism or Fahrenheit 511. Such notions do not bear serious engagement, but since a great many of commentators seem exercised by moral absolutes on the sanctity of art – it’s worth stating the obvious on why context matters, even here. The systematic suppression of art or literature is not something any progressive movement would want to condone – it signifies degeneration and counter-revolution. But no such thing was taking place at UCT, this was not the actions of a state or militarist organization deliberately trying to erase a culture, but another symbolic act of anger on behalf of an subaltern movement persecuting a legitimate struggle for decolonization – a central domain of which is aesthetic. Of course we may wish for a more temperate solution, the relegation of those turgid paintings to some dusty museum, but the reality is that we don’t always have a choice – mass action obeys its own logic. To project a veld fire out of a bonfire on this issue, when the realities of police brutality and exclusion are so immediate, seems not only pedantic but a complete corroboration of what protestors are claiming – that black lives matter less than white insecurities.

Thankfully, the students themselves do not seem much perturbed by these responses – they are viewed as just another predictable instantiation of attempts to police black rage by a sordid establishment. It has been my honest view that such arguments have been overused by some activists – with the result that fraternal critique is not adequately distinguished from hostile denunciation. But those pressing to uncover colonial hangovers behind all of their critics have sadly been validated time and again, and this latest incident will be viewed as no exception. None of this is to suggest that the movement is beyond reproach, that we can totally separate its cause from its means, or that tactics need not be seriously dissected within the ranks and extremist elements held to account. Torching offices and buses is reckless and likely to lead only to further repression – but to equate the rage of the protestors with the official brutality of the state is the bedrock of conservatism.

Boutros-Ghali, more than an Ali G punchline

How to mark the passing of Boutros Boutros-Ghali, former UN Secretary General and a major figure of late 20th Century global affairs? Perhaps by appraising the lessons to be learned from his life and work. The world in 2016 presents a set of problems distinct from those faced by Boutros-Ghali as the Cold War fizzled out in the early 1990s. He had hopes for a more just international order, hopes which were thwarted and cast aside, as the US and its NATO allies careered towards a new norm of “humanitarian intervention,” the unending, spreading wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the new migration crisis. So while his contribution to the international political landscape cannot exactly be appraised as a triumph, perhaps the lessons to be learned are from his dashed aspirations. With all of that in mind, we asked a few scholars in international relations to reflect on Boutros-Ghali’s life and career.

Oumar Ba

Boutros-Ghali – the first African to become UN Secretary General, started his tenure at a time of tumultuous world events that left the UN still incapable of creating an efficient organization for a new era. In 1992, the Berlin Wall had already fallen, the East-West divide had dissipated to the point of making it easier to pass UN Security Council resolutions, but the world also entered an era where complex humanitarian crises meant that peacekeeping operations meant no longer merely sending blue helmets to monitor cease-fires. These were the times of Boutros-Ghali.

Somalia and the US response to it in 1993 pitted Boutros-Ghali against the Clinton administration. The following year, Rwanda revealed the extent to which inaction had paralyzed the UNSC, eager to issue mandates without appropriate resources. For instance, as the Rwandan genocide was unfolding, the UN decided to reduce its presence from 2,500 to 200 troops, with the mandate of helping the parties negotiate to stop the killings. This failure certainly can’t be squarely imputed to Boutros-Ghali, but rather to the UNSC members. In 1995, Bosnia proved what everyone already knew: the UN was utterly incapable of delivering on its promise to preserve international security.

Yet, Boutros-Ghali had the perfect profile to be UN Secretary General, if there ever was one: African, Arab, Christian, Francophile, seasoned diplomat, international law scholar. His ambitious 1992 Agenda for Peace provided a blueprint for UN reforms, to address the new challenges of the post-Cold War politics and conflicts. It called for a more robust peacekeeping force on standby, with wider mandates and responsibilities in not only preserving peace, but also creating it, where necessary. But it would soon be obvious that the powers to be were not interested in implementing such agenda.

With the Clinton administration’s decision to bar him from serving a second term – and Madeleine Albright as the executioner of that decision – Boutros-Ghali left a UN that still struggled to draw a new blueprint for the 21st century. The man who wanted but failed to make the post of UN Secretary General more secretary than general later returned to the francophone world as the first Secretary General of the Organization Internationale de la Francohphonie.

Boutros-Ghali and Mandela

Boutros-Ghali and MandelaLina Benabdallah

That Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s legacy is tainted with major failures in humanitarian interventions is a mischaracterization of his role within the bigger picture. The pitfalls and disappointments of the post-Cold War United Nations should be placed within the context of larger issues that permeated that era. From a Western-centric perspective, the Cold War (not universally all that cold) was a success since no bullets were fired. From a non-Western perspective, conflicts such as the one in Somalia or Cambodia were direct echoes of the realpolitik going on between the two superpowers. Boutros Boutros-Ghali was the first UN secretary general of the post-Cold War global order and inherited a completely different organization. Was he set up for failure?

In hindsight, it is clear that the UN’s transition from a Cold War sabbatical mode to a more proactive international role had to face a few bumps along the way. Boutros-Ghali walking into his term viewed the early 1990s not as a time to celebrate the end of the Cold War; but as the duty of the international ‘community’ to repair the damage done at the Cold War’s margins, in Africa (mainly). He writes in his book Unvanquished: a U.S.-U.N. Saga “I had been elected as Africa’s candidate to take “Africa’s turn” in the job of UN secretary-general. Because of this, (…) I committed myself to try to advance the cause of the continent.”

In my view Boutros-Ghali treated the UN as a post-colonial body which was tasked to respond to issues primarily in the Global South, and specifically in Africa. He reiterated in several instances, controversially, that loss of life to conflicts in Europe and North America should not be valued more than those in Africa and Asia. He reportedly described the conflict in former Yugoslavia as “the war of the rich.” Needless to say such statements earned him heavy criticism.

His stand with the ‘wretched of the Earth’ in the Global South was admired by many, but the existential dilemma of his organization and its financial dependence on U.S. congress tied his hands. For US secretary of state Madeleine Albright and the Clinton administration, Boutros-Ghali had taken a little too seriously his title as general (as in secretary-general) more than secretary. In any event, Boutros-Ghali’s provocation and pressure on the US to pay its dues to the UN did not bode well, and was one of the cards used against reelecting him for a second term, and contributed to his disenchantment with the institution.

Yet, more controversy followed Boutros-Ghali’s legacy even long after his relationship with the UN. Recently, in an interview with Jeune Afrique, Boutros praised Egyptian president Al-Sissi as a selfless man who “only took over power because there was no other solutions,” adding that by doing so he “saved Egypt.” This support, and blunt denial of the existence of any political opposition in Egypt, earned Boutros-Ghali a lot of criticism at home and abroad as Al-Sissi’s regime has been denounced for severe violations of human and political rights.

Muhammed Korany

As we mourn the loss of Boutros Boutros Ghali. We should remember his tireless efforts to promote diplomacy as the beacon of light in the darkest times. He showed us that even when war seems unending, there is a path to light. It’s important that even in the turbulent times that we live in today that we remember peace and prosperity are just over the horizon.

We highly recommend checking out Vijay Prashad’s superb piece for The Hindu. Here’s an excerpt:

During his tenure at the UN, Boutros-Ghali laid out an Agenda for Peace (1992) and an Agenda for Development (1995). In the former, he argued for more robust UN action towards the sources of instability in the world. It was not enough to increase UN peacekeeping missions — to send out the blue helmets to police the world. That was merely a symptomatic approach to crisis. The UN needed to tackle the roots, to understand how the “sources of instability in the economic, social, humanitarian and ecological fields have become threats to peace and security.” To get beyond symptoms, Boutros-Ghali hoped to drive a new “agenda for development,” which would counter the tendency to allow unfettered corporate power to undermine the interests of the millions. Impoverishment created the conditions for insecurity. A secure world would require the human needs of the people to be taken seriously. Debt of the Third World had to be forgiven. No International Monetary Fund-driven recipe for growth should be forced on weak countries. “Success is far from certain,” he wrote of his agenda, which seems charming in light of what followed.

Boutros-Ghali warned, in 1992, “The powerful must resist the dual but opposite calls of unilateralism and isolationism if the United Nations is to succeed.” He had in mind the U.S., which believed that it need not heed the diversity of opinion in the world but could push its own parochial agenda in the name of globalisation. Boutros-Ghali went unheeded. In 1993, at a lunch with Madeleine Albright, the U.S. Ambassador to the UN, and with Warren Christopher, U.S. Secretary of State, he said, “Please allow me from time to time to differ publicly from U.S. policy.” He recalled that Ms. Albright and Christopher “looked at each other as though the fish I had served was rotten.” They said nothing. There was nothing to be said. The sensibility of the moment was that the Secretary-General of the UN needed to take his marching orders from the White House. The Americans do not want you merely to say “yes”, he would later say, but “yes, sir!”.

February 18, 2016

The Burning

At the University of Cape Town (UCT) this week, a group of students protested the housing crisis that has affected the university for as long as black people have been present as students on the campus. Every year black students students starve and drop out because they cannot afford campus accommodation. The #RhodesMustFall (RMF) movement, from which South Africans have come to expect uncompromising and hard-to- watch displays of anti-colonial symbolism, decided to erect a shack to disrupt the complacency that says shacks must stay in their place.

The appearance of a small corrugated iron shack where it doesn’t belong. It was jarring; incongruous amidst the pristine and manicured elitism of UCT. It looked malignant; a growth where tidiness normally masks exclusion.

It was a powerful statement but the protesting students were not content with just ruffling feathers. They wanted to make a pyre: to burning paintings the way one might an effigy. It was a send-off to all the dead white men whom history has covered in glory instead of blood.

The fact that the UCT art collection continues to house so many of these sorts of portraits was laid bare. The flames licked at history. The colonial exploiters were framed in gilt and the fact of them, the idea that there are so many homages to this past, was sickening.

So I looked at the pictures and felt sick. I felt sick at the fact of them, and I felt sick at their being burned. Then I learned that the Vice Chancellor’s office had been petrol bombed and I felt very very sick indeed. What if there had been, in there a black woman cleaning. What would we then say about the collateral damage?

The events at UCT unfolded after weeks of tension at Wits University. Last week, art student Zama Mthunzi who was reported to the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) for hate speech over a t-shirt he created during a protest over the financial exclusion of poor students from Wits, and the presence of security personnel on campus.

Art, it seems, has contagious qualities, as does violence.

At both UCT and Wits, at the University of Kwazulu-Natal and at the University of Johannesburg, indeed at many of the historically white universities in South Africa, private security has been heavily present since the beginning of the academic year in late January. University administrators have dug in their heels, as have activists. Both sides accuse one another of violence.

The university of course, has institutional and structural weight on its side. It has far more “respectable” power than the students. It has the logic of the status quo in its corner and so it is easy to see it as ‘rational’ in the face of irrational and angry students.

I take this as a given. I do not suggest that the university and students have commensurate power. Perhaps my problem is that I expect more from emancipatory movements than I do from the academy. I want the movement that is building and growing to be ‘clean,’ and untainted by the decay and rot of violence, by accepting that the winning side gets to erase all traces of their enemy.

More to the point though, of what really worries me, is the sense that our national debates about these issues are so starkly polarized. Too many of us insist on scorn and derision, and yet these issues are critical for our common future. South Africans, it seems are increasingly engaged in violent rhetoric and action.

So this is not a note aimed at berating #RhodesMustFall though the blowing up of the office is chilling. I have disagreements with some of the tactics they have used of late. More broadly though, as I look across the political and social landscape, I am concerned that our activists should not succumb to the either/or thinking that seems to have gripped other quarters in our country. I fear though, that many amongst the student movement are veering in this direction.

Responses to the t-shirt and to the tactic of burning the Vice Chancellor’s office and also the art have been so frighteningly unequivocal. You are either totally with the students, defending their right to burn art and buildings because people’s lives matter more and ‘who cares about those dead whites and rubbish art anyway?’ or you hate the students and dismiss their concerns because they are wanton and dangerous property destroyers.

Something is wrong. Similarly, in the case of the t-shirt, there is an important debate to be had. Is saying “Fuck Whites,” a useful or a diversionary tactic? Where does the violence of masculist language take us? Yet in too many quarters, simply asking these questions makes you a sell out. On the other end of the divide, it makes you anti-white, a hate-monger for daring to support a student’s speech as fair comment in a racist society.

The false need for agreement, and the vitriol spread around when people disagree – with university management, with politicians, and with activists – is starting to worry me.

But let me be clear about my own views on some of this. On RMF, and specifically the UCT issue, it is shameful that students have not been guaranteed the right to housing. Part of the project of making universities spaces of liberation and genuine learning includes supporting poor students to be fully functional students like their elite peers.

Also, art must not be burned. Supporters of the burning of the paintings have argued that this is yet another defense of western notions of respectability; that art is sacrosanct because European democracy says that it is. I find this view too narrow, and indicative of how much work we still have to do to decolonize our mentalities.

In African societies the griot, the dancer, the woman who painted her home or beaded, or who drew paintings on the inside of a cave – have been important and in some instances sacred people in our communities. So I am skeptical of the idea that ‘art’ is only valued by people from settler and colonizing societies. It seems to me that we ought to value art precisely because our acts of creativity have been so under-valued and mis-recognised for so long.

Burning colonial artifacts might feel good but in the end it seems like an act of woundedness rather than an act of strength. It does symbolic violence to the colonizers and that may be okay, but more than that – and this is where I have real questions – it seeks erasure. I want to believe that a movement for justice is one that rages against forgetting, not one that enables it.

I continue to believe that the students who have brought Rhodes’ statue down and continue to insist that we look his legacy in the face, are some of our finest and bravest minds. They have found a way to demonstrate the symbolism of the colony and to shake this country out of the complacency of accepting the intolerable. They must also know that when you begin to destroy art (regardless of its quality or who made it) the collateral damage is always, always far more bloody and self-harming than you can immediately see.

In the end a movement is not simply the sum of its ideas; it is spoken for by the actions of its members. A movement marks its progress by what it has created and not just by what it destroys (although destruction has its place).

A movement must see beyond the here and now; beyond the catharsis of immediate disturbance. Catharsis has its own power but it must not be mistaken for power. What is done in the name of a movement either builds it, or haunts it.

The task for this generation of activists is to reimagine power and this means resisting the impulse to use power in a way that demeans and cheapens and exploits. This means refusing to use the master’s tools. Violence is the favourite tool of the institutions and structures that do the most harm to black and poor and marginalized people everywhere in the world and so I will continue to repudiate its use, even as I recognize that it takes place in the context of greater and often disproportionate violence. I know this is not popular amongst those with whom I spend intellectual time but it is a position I have considered carefully.

I would like the RMF movement to employ ever more creative and energy-giving means to fight power as it is currently understood in this country. I would like RMF and other student groupings to also aim their ire at the liberators who are also black, because they have betrayed the dreams of millions and they command a trillion rand state budget. #FeesMustFall began this focus on the state but I am deeply interested in where it goes and what that also builds. I would like RMF to widen its scope while also continuing to aim at those who have always run the colony and who still today continue to administer a system of intellectual apartheid.

I know that this is not my movement and that I am almost old enough to be a mother to some of the protesting students, so these are just wishes. I am aware that this is a lot to ask and that it has its pitfalls. Still, given everything I have witnessed this past year, I am hopeful. I continue to watch this generation and to be awed by its energy and dynamism and bravery. I remain an ally – critical; worried at times; on my feet with excitement at others – but an ally nonetheless.

Akin Omotoso’s NBA All Star Weekend diary, Toronto

Wednesday 11th: In Rum We Trust

All that snow that Alejandro G. Inarritu said evaded them in Alberta, Canada during The Revenant shoot finally turned up in The T-Dot with full force.

I thought I would escape writing about the weather this year but it dominated all the narratives. Even the Lords Of The Court weren’t immune. Commissioner Adam Silver’s joke about the weather was the best for me, he joked to reporters that the game was played indoors. And indoors on College Street at Free Times Café was where I found myself on arrival. I asked the waiter for their house special telling him I had journeyed from far. The Hot Apple Rum cider was presented to me. As I sipped on it, I asked why he recommended this drink. He smiled and said: “when it’s cold like this, in rum we trust.”

Thursday 12th: Giants Of Africa

Masai Ujuri has a lot to be proud of as the world arrives in Toronto for All Star weekend. The All Star Game will feature two of their players in DeMar DeRozan and Kyle Lowry, and the Raptors are the number two team in the Eastern Conference behind a team led by the King.

Kicking off the festivities was a premiere screening of a documentary on Masai’s work on the African continent called Giants of Africa. The premiere was at the TIFF Bell Lightbox, the official home of the Toronto International Film festival. The invite called for smart casual, let’s just say I dressed warmly which to me was the smart thing to do. It was a red carpet affair, with all the guests walking onto the red carpet with the sounds of Baba 70 playing. The Fela Playlist was strong and I nearly burst out dancing when my one of my favorite Fela songs came on. In fact, I wanted everyone to stop for a minute and listen to “Army Arrangement.” I remember once watching Femi Kuti perform the song at a gathering in Lagos a few years ago, and even though Fela wrote the song in the 70s, and Femi was singing it in the present, he didn’t have to change a single sentence. That’s genius.

The documentary, directed by Academy Award nominee Hubert Davis, follows Masai and his team as they try to make an impact in the lives of basketball players in Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana and Rwanda through the Giants Of Africa program and the basketball camps they hold. The film is very moving and powerfully told. Especially because of the players, and their histories, and the wars some of them have overcome to make it to playing in the camps — you can really get a sense of the salvation this hoop dream can bring. Cinematically, it presents a basketball poetry hardly seen from the point of view of Africans. There is a sequence where a character tells the most gruesome story of his upbringing, while the camera tracks beside him dribbling the ball on the darkest of nights — it was cinema at its most visceral.

Friday 12th: Ice Cold 6

The first thing that I realized today was that whatever I had brought for warmth wasn’t going to cut it. Never mind wardrobe malfunction, I needed a wardrobe overhaul. Basically my South African jackets were vests compared to what I needed to deal with in The 6. I had to get Mammoth type furs.

It was the Rising Stars Game. To celebrate the first NBA All-Star game taking place outside of the U.S.A., the NBA made Team World the home team instead of Team U.S.A.. Representing Canada were Andrew Wiggins, Trey Lyles and Dwight Powell. For the continent, Denver Nuggets Rookie Emmanuel Mudiay, whose story going from DRC to China to the NBA has to be told on film some day. And even though Jahlil Okafor was playing for Team U.S.A., we still ‘throway salute’ as they say in Pidgin English. Mudiay came out smoking, and despite his best efforts Team U.S.A won by three points.

After the game, walking through the pathways from the Air Canada Centre — built to keep visitors like myself out of the cold, someone said that tomorrow was going to be colder. I asked myself how that was even possible?

Saturday 13th : Negative 31

The lady told me, “No one gets accustomed to negative 31 wind chill,” as she fetched her jacket from the coat check. “I might be Canadian but I ain’t crazy!” she added. Originally, when I planned this trip I thought it would be a great opportunity to get the see the city from a different point of view. Usually when I’m in Toronto I just use the taxis. This time I thought I’d explore the bus routes, do some walking etc. Then Revenant Part 2 snow happened and I realized a few things about my life: 1) I have nothing to prove to anyone 2) From now on I am limiting the steps I take in actual snow. 3) I now know how fast I can get from the house to the Uber, and how fast I can get from the arena door to the front seat of the taxi. These are the things that start to consume my mental and physical energy, because the cold is real.

Klay Thompson paid attention when his father told him not to come home if he didn’t win the three point shoot out. And then, the event that had been low on everyone’s radar turned out to be a history making one. To be in the arena and watch Aaron Gordan and Zach LaVine go at it in ways that the contest hasn’t seen since the Air Jordan and The Human Highlight Film was the one time, for a brief moment, that Negative 31 was the last thing on my mind. To watch such a history making event live was surreal, and as someone on Twitter said, “They should have had them dunking till Monday!” To think I had even dared to suggest that the dunk contest be moved from the highlight of the evening to the middle section and the 3-point contest turned to the main event. How dare I?

Sunday 14th: Kobe

The score was never the thing about today’s All-Star Game. It was all about Kobe.

The fans at the Air Canada Centre gave him a great send off. The custodians of the game, those Lords Of The Court, kept it free flowing. The jump ball between Kobe and Lebron was a nice touch. And, with different players taking turns to guard Kobe, the mood was light, and the audience was appreciative. This is why we watch, this is what we play for and this is why they play.

And while Kobe had the night, Steph Curry reminded everyone that he and the Warriors are still the team to beat, the team to watch and bring on the second half of the season.

*All photos by Akin Omotoso

February 17, 2016

Capturing Brazilian Candomblé through the lens of Mario Cravo Neto

Mario Cravo Neto, ‘Laróyè 1980-2000. Courtesy Rivington Place, London.

Mario Cravo Neto, ‘Laróyè 1980-2000. Courtesy Rivington Place, London.There is a silent story when studying global history in the UK. This is the history of the slave route from the African continent to Brazil. Led by Portuguese colonisers, the route between Africa and Brazil saw ten times more slaves crossing the ocean (around 5.5 million in total, of which 4.8 made it across alive) than the ones forced by the British to work in the U.S.

Most of the people taken to Brazil were forced to work in Portuguese plantations, with the central hub being the city of Salvador in Bahia, founded in 1548. This city is also the birthplace of photographer, Mario Cravo Neto.

Born in 1947, Cravo Neto is one of Brazil’s most widely acclaimed photographers. Rivington Place—one of London’s foremost art centres—is now hosting Cravo Neto’s first UK solo exhibition. He passed in 2009, but this exhibition shows how much he will be missed.

Cravo Neto’s work is important to understand the religious practice of Candomblé in Brazil. Candomblé is a religious practice based on West African beliefs, specifically from the Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu people. From the 16th Century, many of these people brought their traditions and oral histories on the slave ships, weaving them together (combined also with the colonisers Catholicism) to form what refer today as Candomblé.

Portuguese colonisers tried to end the traditions of Candomblé, which explains why the first Candomblé church was only founded in the 19th Century. Candomblé followers were still frequently persecuted until the 1970s, but this was perhaps more to do with its role as a religion that is essentially racialised and tied to ‘blackness,’ which many Portuguese demonised.

Case in point, the initial colonisers were intensely aware of this majority non-white population, thus systematically encouraged and implemented a migration of white Portuguese population to Brazil. Miscegenation—the mixing of different racial groups—during the period of slavery was also a lot higher in Brazil than in the U.S.: whilst this may be attributed in part to promiscuity, it also reads as a dissemination of the white, Portuguese ‘seed’ into the black population (whilst the British feared miscegenation, the Portuguese seemed to encourage it).

Mario Cravo Neto, ‘Sacrificio ‘V [1989], Courtesy of Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zurich & Rivington Place, London.

Mario Cravo Neto, ‘Sacrificio ‘V [1989], Courtesy of Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zurich & Rivington Place, London.Candomblé as tied to blackness was seen as an act of resistance against the coloniser. This was literal in the case of quilombos: communities founded by runaway slaves, where Candomblé is most often practiced and to this day undergo frequent raids by police. A quashing of Candomblé thus becomes a quashing of blackness, and vice versa.

Cravo Neto’s photographs therfore become a site of resistance. He understands the importance of Candomblé to Brazilian identity, and puts it at the forefront of his work. His images are imbued with references to the spiritual practice: Sacrificio V (above), the sacrifice of animal, which is said to feed the deities, existing as an explicit example.

Less clear are some of the other more nuanced black and white portraits that make up the first half the exhibition named The Eternal Now. In this instance I think of Deus de Cabeça (Head of God; see photo below). An integral part of the belief is the following of orixas (orishas), the deities underneath the supreme creator, Oludumaré. Each person is said to have their own orixas, based on their personal character, who they then communicate with and worship throughout their lifetime. Parallel to orixas are nkisi, objects which contain a spirit. Deus de Cabeça is a coming together of both orixas and nkisi. The subject holds the spirit, represented here in turtle, to their face—their bodies becoming a patterned symbiosis—amalgamating the nkisi, or the orixas (whichever way you want to see it) with their human counterpart.

Laróyè is the second portion of the exhibition. The word is a greeting to éxù, the messenger of all the orixas. As Argentinean curator Gabriela Salgado writes: “without his [éxù’s] consent, the other entities would not manifest or connect with humans, as he holds the key to open the gates of the intangible.”

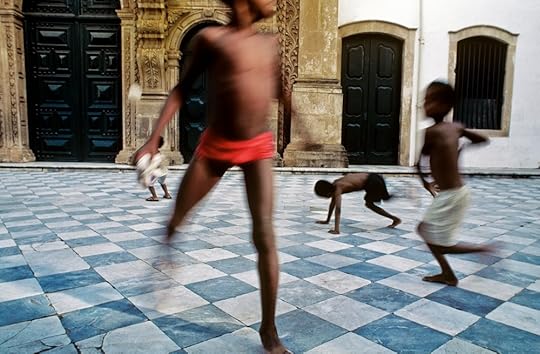

In her salient essay she also goes on to point out that éxù is an entity that patrols the street and protects those that inhabit it, “the homeless, the stranded and children.” Cravo Neto’s colour photos here come as manifestation of éxù, the camera eye reflecting that of éxù’s own. The messenger’s colours are black and red and this colour scheme is leitmotif that runs throughout the photographs that Cravo Neto made for Laróyè. Whilst the shadows in these photos are strong, the bodies of the Salvador population exude the prevailing black. They become the ‘earth’ and clad in red cloth, the ‘fire’ too, that the black and red of êxù are said to symbolise. They are the human counterparts of éxù – both the life force of Salvador and the messengers of the Gods.

Mario Cravo Neto, ‘Laróyè 1980-2000. Courtesy Rivington Place, London.

Mario Cravo Neto, ‘Laróyè 1980-2000. Courtesy Rivington Place, London.But what if, like me, you have little knowledge of Candomblé when you enter Rivington Place? What I was reminded of first was the musings of novelist, essayist and photographer, Teju Cole, in his essay, “A Truer Picture of Black Skin.“ In the black and white works of Cravo Neto, but even in some of his colour photographs, there is not always an attempt to illuminate black skin. I mean that literally—some of these photos are dark, the shadows, as aforementioned, are strong. Teju Cole writes similarly about the photographer, Roy DeCarava: “His work was, in fact, an exploration of just how much could be seen in the shadowed parts of a photograph, or how much could be imagined into those shadows.”

Mario Cravo Neto, ‘Laróyè 1980-2000. Courtesy Rivington Place, London.

Mario Cravo Neto, ‘Laróyè 1980-2000. Courtesy Rivington Place, London.What DeCarava was shooting, says Teju Cole, was black identity under question. The same could be said of Cravo Neto, even if imagined differently. Both are documenters of the black experience in their respective countries (DeCarava’s in the U.S.). Both use the shadows to help illustrate their point. They differ as photographers all over the place: framing, colour, abstraction vs. realism. But the shadows remain, and talk of untold or invisible experiences.

There aren’t many fixed statistics regarding the numbers of Candomblé followers in Brazil. In 2010, around 5% of the population declared themselves spiritualists—one can only imagine some of these follow Candomblé, but not all.

In a country that declares itself a racial democracy (something to explore another time), I believe it important to understand the history of Candomblé (even if the numbers are small) to the Afro-Brazilian experience—as both a cultural practice, a form of black unity, and as colonial defiance. In this sense, the photographic works of Cravo Neto are increasingly important: as documentation, as art, and as resistance.

‘Mario Cravo Neto: A Serene Expectation of Light’ is on at Rivington Place, London till 2nd April 2016, and is free entry. Do also check out the exhibition there on Maud Sylter—it is equal importance.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers