Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 305

May 26, 2016

Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead

Their voices, sharp and angry, shook me from my slumber. I didn’t know the language, but I instantly knew the translation. So I groped for the opening in the mosquito net, shuffled from my downy white bed to the window, threw back the stained tan curtain, and squinted into the light of a new day breaking in South Sudan. Below, in front of my guest house, one man was getting his ass kicked by another. A flurry of blows connected with his face and suddenly he was crumpled on the ground. Three or four men were watching.

The victor, still standing, appeared strong and confident. His sinewy arms seemed to have been carved from obsidian. Having won in decisive fashion, he turned his back and began walking away with a self-satisfied swagger. The other man staggered to his feet, his face contorted with a ragged, wounded-animal look — the one that seems to begin as an electric ache at the back of your jaw, drawing your lips back into a grimace as tears well up in your eyes. And what he did next seemed straight out of a movie. I couldn’t believe I was seeing it.

The vast, rutted dirt field below me was filled with trash: half-burned water bottles, empty soda cans — and glass. And that furious man promptly did what I had previously only seen on screen. He grabbed a bottle by the neck — it might already have been broken or he might have shattered off the bottom with a quick rap on a rock — and in an instant he had himself an equalizer.

The ass-kicker spun around to find the tables turned and he knew it. The man with the bottle knew it, too. He was shouting and jabbing, though he wasn’t actually close enough to do any damage. Nonetheless, with fear spreading across his face, the ass-kicker backpedaled, still talking loud but unmistakably in retreat.

It seemed clear enough that the man with the bottle didn’t really have it in him to punch that jagged glass through the other’s taut skin. His fury seemed to fade fast and he didn’t press his advantage. Or maybe he was just afraid of what might happen if he were disarmed. Whatever the reason, cooler heads prevailed. The onlookers got him to drop his weapon and the combatants walked off in opposite directions. It was over, even if nothing else was in South Sudan.

At one point, as the two fought, I glanced back at the bed where my cell phone lay and nearly fetched it. The impulse to shoot a few pictures or some video footage of the unfolding scene was powerful and hardly surprising since I come from a culture now built around documenting and sharing even the most mundane happenings.

I didn’t move, in part because I had no idea what was going on. If I recorded it, what then? What accompanying story could I tell? I knew that, short of one man killing the other, it was unlikely that anyone would be around by the time I threw on my clothes and got downstairs. Real-life fights rarely last long. And what, even if they spoke English, were these men going to tell me? Would I write about a personal skirmish over money or a woman or some drunken insult?

Thinking about it later, I came to see the episode as a metaphor for my situation. It was the summer of 2014 and the dawn of my first full day on my initial trip to South Sudan. I was there to get an on-the-ground look at a failing nation in the midst of a months-old civil war; a complex, partly tribal conflict that, in some ways, boiled down to a backyard fight between two men. And frankly, as with the morning struggle I had just witnessed, I had little idea of what was going on. Sure, I’d talked to humanitarian experts and South Sudanese in the United States. I’d read news articles and substantive reports by the United Nations, Human Rights Watch, and others. On the flight over, I’d finished a very good book on the country and a couple marginally useful ones before that, but I couldn’t have been more of a neophyte standing there in the capital of a new nation, convulsed by a conflict that had already killed more than 10,000 people and left millions homeless or displaced.

Still, I came with a history that seemed suited to the situation. I’d spent parts of the previous decade wandering around post-conflict countries in Southeast Asia, unearthing evidence of horrendous crimes committed by the United States and its allies. I had traveled to remote Vietnamese villages no American had visited since my country’s combat there ended in 1973, hamlets where the villagers might never have met an unarmed Westerner. I talked to people about rapes and murders and massacres, largely by American troops. I interviewed them about living for years under bombs and artillery shells and helicopter gunships that hunted humans from the sky. I spoke with women and men who saw their families cut down by American teenagers with automatic rifles. I talked with those who had lost limbs or eyes or were scorched by napalm or white phosphorous — incendiary weapons that melted faces or left the victims with imperfectly mended swaths of skin. And back in the United States, I spent endless hours with the men who had done these sorts of things to Vietnamese and Cambodians, as well as others who had refused to take part.

After more than 10 years immersed in atrocity, I needed a change so — obviously — I headed for a war zone filled with atrocities about which I knew next to nothing. But to me, it felt different. I wasn’t about to repeat my work in Vietnam. I had landed in a place where history was being made and I was going to do my best to report on a different kind of war victim. This time, it was going to be displaced people trapped by the thousands on United Nations bases that had become almost like open-air prisons. It didn’t take me long, of course, to realize that there was something unnervingly familiar about the work, about the grim tales I began to hear of suffering, privation, and loss (with women and children, as always, hit hardest). In talking to people in those sun-drenched limbos — refugees in their own country — it took next to no time for stories I recognized well to begin seeping into the interviews, tales of family members gunned down in the streets, of rapes and assaults, the sort of hideous acts that form the fabric of modern war, no matter what country, what area of the world.

I spent a couple weeks in-country talking to ordinary South Sudanese and humanitarian workers, taking stock as best I could — part of the time on the outskirts of Malakal, a war-ravaged town 515 kilometers north of Juba.

I traveled there, in the heart of the rainy season, to find a United Nations base drowning in a sea of muck and squalor. And I wiled away an evening with a couple of local journalists who had, in the wake of the war, signed on with the U.N. Bathed in an unnatural fluorescent glow, we talked shop after hours in their office. I wanted the inside story of South Sudan’s crisis and they, in turn, wanted to know about me. Perhaps unsatisfied with my answers, one of them decided to consult Google for background. My book on the Vietnam War, Kill Anything That Moves, popped up instantly and he looked up from his monitor astonished. He had, after all, just told me about how a member of his family — a man of some standing — had apparently been the victim of a targeted killing in the opening salvo of the civil war. If I specialized in investigating crimes of war, the journalist wanted to know, why the hell wasn’t I investigating war crimes in South Sudan? I came up with excuses, but my new acquaintance found them unconvincing and, in truth, I wasn’t that convinced myself.

I spent that night on a cot in the back of a deserted office on that U.N. base thinking about what he had said and was still thinking about it the next day when I arrived at a nearby airport to catch a U.N. flight back to Juba. Of course, to call it an airport is a bit of a misnomer. By the time I arrived, it had devolved into an airstrip. Nobody seemed to use its vintage blue and white terminal building anymore. Instead, you drove past cold-eyed Rwandan peacekeepers, U.N. troop trucks, and an armored personnel carrier or two, right up to the tarmac.

That’s where I was when a large, nondescript white plane arrived. That in itself was hardly remarkable for Malakal. If it isn’t a World Food Program flight, then it’s a big-bellied plane hauling in supplies for some nongovernmental organization or a U.N. plane like the one that brought me there and would soon take me away.

This nondescript white plane, however, was different from the others. When the Canadair CRJ-100, with “Cemair” written across its tail, taxied up and its door opened, a group of young men in camouflage uniforms carrying assault rifles and machine guns emerged. And they were met there by scores of similarly attired, similarly armed young men who had arrived in a convoy just minutes before.

I’d never seen anything like it, so I pulled out my phone and tried to surreptitiously take a few photos. Not surreptitiously enough, it turned out. A commander spotted me and promptly headed my way, visibly angry and waving his finger “no.” As I glanced to my left, a boy holding an AK-47 and following the officer’s gaze turned toward me and with him came the barrel of his rifle.

I didn’t think he was going to shoot me. There was no anger in his eyes. He didn’t draw a bead on me. His finger may not even have been near the trigger. Still, he was a boy — he looked about 16 — and he was holding an assault rifle and it was pointed in my direction, so I stepped lively to put the commander between him and me, while quickly shoving my phone in my pocket and apologizing profusely if not quite sincerely.

By the time my plane arrived and I was heading back to Juba, I was sure that I needed to return to South Sudan to talk to boys like that teenaged soldier; to spend more time on United Nations bases with people trapped in squalor; to try to understand how a new nation only years before “midwifed” by my own country and hailed as a great hope for Africa could be laid so low that people were starting to whisper “Rwanda” and talk about South Sudan as a possible next epicenter of genocide.

Even though I’ve spent considerably more time in the country since, I still don’t claim to know much about this hot, land-locked, Texas-sized country, only a few years old, inhabited by 60 ethnic groups, and a population whose median age is 17. But, there are people who do know it intimately and I sought them out. For several weeks in early 2015, I spoke with U.N. officials and humanitarian workers, military officers and child soldiers, politicos and “big men,” but mostly with ordinary people whose already tragedy-tinged lives had been blown apart by a violent power struggle that began on a military base in Juba and spread like a pandemic into the neighboring streets, then through the capital, and finally into rural hot zones to the north.

No one knows how many men, women, and children were slaughtered in Juba’s streets that first night, December 15, 2013, or how many died in the following weeks as war flared in the towns of Bentiu, Malakal, and Bor, or in the spasms of violence elsewhere in the months that followed. Nobody knows where all the bodies went; where all the mass graves are located. But when so many die, others in similar situations do survive and I sat down with scores of them in plastic-tarp shanties, dimly lit bars, deserted workplaces after hours, or under the welcome shade of sun-scalded trees, or we spoke by phone or on Skype in Africa and the United States. With a vividness that often astounded me, they described their stories of hardship and horror and sometimes even told me of small victories.

There is a chance that by the time this book is published a peace deal signed as the manuscript was being completed will take root — unlike the many ceasefires before it that shattered, some within hours — and that the world’s newest nation will be on a path to reconciliation and prosperity; a chance, that is, that the promise of that country’s Independence Day in 2011 will finally be realized. There is also the potential for so much worse, the possibility that recent reports of government forces raping girls and burning them alive, castrating young boys and allowing them to bleed out, or crushing people with armored vehicles are a prelude to an even more brutal, sadistic spree of violence on an even more massive scale, a chance that “Rwanda” could become a reality in South Sudan in the months or years to come.

Whatever happens to the country and its long-suffering people, the voices in this book serve, I hope, as a testament both to the struggles and the courage of the victims of violence there and as a cautionary tale of the sort of chaos and mayhem that may lie ahead.

This is the introduction to Nick Turse’s new book, “Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead: War and Survival in South Sudan,” published by Haymarket Books. The book can be purchased here and here.

May 25, 2016

Kenya’s Refugee “Problem”

Earlier this month, the Kenyan Interior Ministry declared its intent to shut down the country’s refugee camps, citing concerns about security and the threat of terrorism. The last time the government indicated its plan to close the camps in April 2015, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry announced $45 million in additional aid, and the camps remained open.

This time, policymakers and domestic and international rights activists have noted with grave concern Kenya’s recent revocation of prima facie refugee status for Somalis, who constitute two-thirds of the nearly 600,000 refugees in Kenya. This change means that those fleeing Somalia will need to apply for refugee status on a case by case basis—made more complicated by the decision to shut down the Department of Refugee Affairs—and in the interim, they will be subject to removal and abuse by security forces.

Commentators have pointed out that the Kenyan government has never substantiated its claims that refugees were responsible for violent attacks in the country. Instead, they argue that the government is using the refugee population as a diversionary tactic domestically, and as a bargaining chip for more aid from humanitarian institutions internationally. As European states are now willing to pay for other governments to assume the burden of hosting refugees, Kenya seems to be positioning itself not simply to attract more funds, but also to challenge the moral authority of Western states when it comes to international obligations.

Integrally tied to this pending humanitarian crisis is the global architecture of counter-terrorism. The Kenyan government is but one actor among many who produce, and profit from, the specter of terrorist threat, which allows for the discursive slippage from civilian, to potential Al-Shabaab sympathizer, to potential terrorist. Readers unfamiliar with the region are led to believe that ‘Kenya’ is an inward-looking political entity with little connection to the situations in neighboring states, beyond its position as the recipient of refugees. The ‘international community’—led by the world’s most powerful states—is viewed only through the prism of aid, with little consideration of these actors’ own role in exacerbating, rather than mitigating the very violence leading to displacement in the first place. Viewed through this polarizing lens of ‘Kenya’ vs. the ‘international community,’ we fail to grapple with the array of conflicting cross-border interests and entanglements at play, and to contextualize the dilemma as it unfolds.

In 2009, the Kenyan government initiated plans to create a buffer zone between Kenya and Somalia. Working closely with both the Ethiopian and Somali governments, Kenya recruited roughly 2,500 youth both from within Somalia and from north-eastern Kenya, including Dadaab refugee camp. Luring them with false promises of financial remuneration, this militia was trained for a possible assault on Al-Shabaab controlled areas in southern Somalia. Yet disputes soon unfolded between Kenya and Somalia about where to deploy these forces, confirming the range of interests at play. The whereabouts of these young men remains unknown, raising important questions about the mobilization of armed actors for the objective of ‘counter-terrorism.’

Yet this number pales in comparison to the nearly 22,000 troops now occupying Somali territory as part of an internationally funded ‘peacekeeping’ operation. Formed in 2007 following the US-backed Ethiopian-led invasion of Somalia, the African Union Peacekeeping Mission for Somalia (AMISOM) troops hail from Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda, with police contingents from Nigeria and Ghana. AMISOM receives logistical and financial support from the UN, and is funded primarily by the EU, US, UK, Japan, Norway, and Canada.

Few analysts have inquired about the violence and displacement generated by the introduction of these armed ‘peacekeepers,’ despite the publication of UN and other reports documenting such effects. In 2014, for example, Human Rights Watch reported that AMISOM troops abused their authority by preying on women and girls, who constitute the majority of those displaced by violence. Rather than weaken Al-Shabaab, the UN Monitoring Group Report observed in October 2015 that offensive military operations by AMISOM and Somali security forces have exacerbated insecurity. The rush by various actors to capture resources in the wake of territorial gain has threatened to undermine peace and state-building efforts, while the territorial displacement of Al-Shabaab from major urban centers “has prompted its further spread into the broader Horn of Africa region.”

African Union troops are not the only actors shaping dynamics in Somalia. Private security firms operate largely with impunity despite documented abuses. In 2015, the UN Special Representative for Children in Armed Conflict expressed concerns about the unlawful detention of children, reportedly formerly associated with armed groups, in a ‘rehabilitation’ camp run by the Serendi Group in Mogadishu. And in March 2016, the US military launched a drone strike that killed 150 people, citing Al-Shabaab plans to attack both US and African Union forces. While US officials insist that the precision of these airstrikes ensure minimum civilian casualties, the Intercept recently reported that the US possesses limited intelligence capabilities in Somalia to confirm that the people killed are indeed the intended targets. Between AMISOM and private security abuses, and the growing use of drone strikes, Somalis may not necessarily feel more secure in the hands of foreign armed actors than they do in the hands of local ones. And as those who have documented the conditions inside Kenya’s refugee camps have indicated, we should perhaps think twice about calls by humanitarian agencies to simply maintain the status quo.

But Somali experiences and perceptions are of little interest to the more powerful external players who make daily calculations about how to justify their continued role.

As Alex de Waal observed in his recent book, The Real Politics of the Horn of Africa, the ‘war on terror’ has enabled “an exceptionally well-financed rentier-political-security market with the added bonus that counter-terror patronage also comes with intelligence technologies and a legal vocabulary that is perfectly suited for justifying secrecy and repression.” Former Somali Special Envoy to the U.S. Abukar Arman uses the term ‘predatory capitalism’ to describe the hidden economic deals that accompany state-building efforts, as ‘capacity-building’ programs serve as a cover for oil and gas companies to obtain exploration and drilling rights, and as senior military officials profit from the illicit cross-border trade in sugar and charcoal.

Cognizant of the potential for critical questions about their own role in ongoing instability in Somalia, the AU and UN have employed consulting firms to ensure that we, as outside observers, continue to conceive of only a select few actors (Al-Shabaab) as part of the problem, with others (UN, AU, peacekeepers, donor states, and private firms) painted as entirely outside the frame and therefore best-placed to offer solutions.

Recent developments have led to the temporary placement of the Kenyan government in the ‘problem’ category. But rather than conceive of humanitarian agencies and the ‘international community’ on one end and the Kenyan state on the other, perhaps it is time to think more critically about their entanglement. As governance in the name of humanity becomes intertwined with the violence of ‘security,’ it becomes less and less clear . Simply insisting that the refugee camps in Kenya remain open distracts us from more difficult but important considerations: namely, the ongoing participation of an ‘international community’ that includes Kenya in the production and reproduction of violence in the region.

May 24, 2016

Racial nationalism and the political imagination

In 1976 the historian and activist Walter Rodney spoke at Howard University on the then-unfolding civil war in Angola. Noting that in the late 1960s and early 1970s many African-Americans had been compelled by the then-nascent UNITA movement’s seemingly Africanist-centered opposition to the socialist-aligned MPLA, Rodney cautioned that “we must of course admit that to declare blackness is a very easy thing to do.” “The Lessons of Angola” he suggested, were that racial solidarity needed to be tempered with ideological solidarity in order to fashion a more effective weapon. The tension between left- and race-based politics has been a constant issue in transatlantic solidarity for decades, as have issues of race, decolonization and education.

The Cornell University historian Russell Rickford examines the historical intersection of these concepts in in his remarkable new book, We Are An African People: Independent Education, Black Power and the Radical Imagination (published by Oxford University Press). Rickford’s study tells the little-known story of how US-based Pan Africanists responded to white racism and a corrupt school system by founding and funding their own schools, throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Over the last few months, Rickford and I had exchanged periodic messages about his book, historical antecedents to contemporary debates about education, and the fault-lines of Pan-Africanist and African diasporic politics. We began by considering the career of Howard Fuller, who founded the Malcolm X Liberation University in 1969.

Tell me about Howard Fuller, a.k.a. Owusu Sadaukai.

Owusu Sadaukai (aka Howard Fuller) was one of the most influential U.S. Pan Africanists of the Black Power era. He was a community organizer who was deeply involved in antipoverty work when he founded Malcolm X Liberation University (MXLU) in Durham, North Carolina, in 1969. The post-secondary school, which eventually moved to Greensboro, North Carolina, was widely regarded as the leading Pan Africanist/black nationalist institution of the period.

Sadaukai is significant for a number of reasons. One of his main contributions was helping to increase black American awareness of and support for armed struggles against settler colonialism and white minority rule in Southern Africa and the Portuguese colonies. Sadaukai made a very influential journey to Mozambique in 1971, where he spent a month embedded with Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) fighters. The experience helped transform Sadaukai’s vision of Pan African solidarity. He began to see the fight against U.S. imperialism as the main priority for black American internationalists, because Portuguese colonialism was propped up by U.S. aid.

Sadaukai also played a leading role in founding African Liberation Day (ALD) in 1972. This annual fundraising and public education effort on behalf of ongoing anti-colonial struggles on the African continent greatly increased Pan-African consciousness in the U.S. It also accelerated the political growth of many U.S. Pan Africanists by hastening the transition from Racial Pan Africanism (a philosophy based on notions of global racial linkages) to Left Pan Africanism (an approach based more on anti-imperialism, anti-capitalism, and anti-racism).

However, Sadaukai followed a very strange path in the decades after the Black Power movement. Ultimately he became a major spokesman for “school choice,” or voucher programs that enable parents to use public education funds to enroll their children in private schools. “School choice” has been a major goal of the privatization movement, and is widely criticized by defenders of public education, the system upon which the vast majority of black children rely. Thus, Sadaukai (who has now reverted to his original name, Howard Fuller) has traveled full circle from integrationism to black nationalism to Marxism-Leninism to staunch advocate of free market policies. In the closing chapters of my book I trace a larger retreat from the radical elements of Black Power politics during the post-civil rights era.

That’s quite an intellectual journey. I want to keep the “end” of Sadaukai / Fuller’s journey in mind as we continue our conversation, but for now let’s go back to the beginning. How was Sadaukai’s political activism and especially solidarity with Frelimo and other liberation movements consistent with his critique of the American educational system?

Sadaukai and other Pan-African nationalist organizers and intellectuals believed black America had been socialized for subservience and sociopolitical dependency.

They were strongly influenced by postcolonial and radical theorists who condemned Western education for “colonizing the mind” of oppressed peoples throughout the world. They joined a host of figures, from Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere to Guyana’s Walter Rodney, in arguing that subject peoples (including African Americans) needed to reject the principles of individualism, materialism and white supremacy on which Western education was based in order to reclaim their humanity and achieve cultural and political autonomy. These were guiding principles for MXLU.

However, Sadaukai’s view of revolution changed in the early 1970s. As he traveled and interacted with revolutionary movements, he developed a more materialist vision of the reconstruction of society. Rehabilitating consciousness remained a major priority, but he began to see anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism as struggles for land and for the reconstruction of political economy. He developed a critique of global finance capital as the engine of political and economic exploitation not just in the Third World, but also in the United States.

As Sadaukai’s politics evolved, MXLU developed a more internationalist and leftist orientation. Equipping African Americans (and other black people) with technical skills so that they could assist in the modernization of developing nations (especially those seeking to travel a socialist path) emerged as the institution’s primary mission. Before it closed abruptly in 1973 amid severe financial trouble, MXLU also attempted to revive its original emphasis on serving local African American communities within North Carolina.

Could you talk a bit about the distinction you made earlier about the difference racial Pan Africanism and left Pan Africanism?

In the book I try to distinguish between a Left Pan-Africanist orientation rooted in a fundamentally anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, and “Third Worldist” outlook and a racial Pan-Africanist trajectory, more wedded to principles of racial fundamentalism, cultural nationalism and the politics of all-black unity.

The complex realities of ideology often stretch the explanatory value of these categories, but over the course of the 1970s sharp conflicts erupted in black progressive and radical circles over these and other ideological distinctions.

The story of the decline of the more radical tendency is complicated. One would have to talk at length about external factors (including state repression) and internal factors (including bitter ideological feuds.) But I think it is fair to say that by the 1980s, racial Pan Africanism was more widespread. It emerged as a more inward-looking form of Pan Africanism re-emerged as a major black political alternative to integrationism. This iteration of Pan-African nationalism took a less hostile stance toward global capitalism than had the radical varieties of the 1970s. It was also more firmly based in the academy and less closely tied to ongoing struggles in Africa and the Caribbean. In my epilogue I make the case that this bourgeois nationalism entered into a kind of detente with corporate capitalism and the forces of privatization. But forms of Left Pan Africanism never fully disappeared, and continued to influence campaigns like the anti-Apartheid struggle and the Black Radical Congress.

Responding to your striking title, I’m wondering what lessons your book offers about the African Americans’ relationship to “Africa” (as a fact, as a concept) both during your time period and today?

The question of the relationship of African Americans to Africa is a thorny one, of course. The historical relationship itself has been torturous. From the African-American perspective, I would have to say that black folk need to understand the history of what I call “Africa in the African-American Mind” (I teach a seminar on the topic at Cornell). A good place to start is by reading Middle Passages by James Campbell and Proudly We Can be African by Meriwether.

But in general, I still think some of the lessons of the Black Power era are relevant in terms of African-American consciousness. Most of the figures in my book start from a position of romanticizing African politics and culture in the context of the 1960s revalorization of African identity. My book’s title, “We are an African People,” comes from a very popular slogan of the late 1960s/1970s, which makes this point quite clearly.

As these activist-intellectuals traveled throughout Africa and the Diaspora, they were forced to confront some of the political and social complexities of societies and governments that they had previously viewed through a very simplistic lens. At best, African Americans rethought the basis of their connection to Africans, moving away from racial mysticism and thoroughly western essentialism and moving toward solidarity based on common circumstances and political perspectives/objectives. They began confronting the complex problems of neocolonialism. They began considering questions of class and gender in both African-American and African contexts. This is part of what I characterize in the book as “political maturation.” Yet, realistically, I must concede that at the end of the day, a push for African and African-American solidarity based on racial romanticism is probably superior to an outright rejection of the idea of shared political fate. The African and African-American cultural encounter seems to work best when both sides recognize multiple historical veils of stereotype and misunderstanding as well as historical ties of solidarity, inspiration, and struggle.

May 23, 2016

Julius Malema’s Tailored Revolution

Julius Malema, at his party headquarters in Johannesburg, 31 March 2014. Image via Jerome Starkey.

Julius Malema, at his party headquarters in Johannesburg, 31 March 2014. Image via Jerome Starkey.At the end of April this year, South Africa’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), launched its local government elections manifesto in front of 40,000 people in Johannesburg’s Orlando Stadium. Julius Malema, who serves as both the party’s political and sartorial “Commander in Chief,” led the proceedings, sporting his now iconic red beret and jumpsuit. This carefully constructed image is central to the EFF’s populist allure, one the party hopes will prove strong enough to overthrow the ANC in the upcoming local elections.

The color red, berets, and plain workers’ clothing have all become potent aesthetic symbols for the EFF. Standing in monochrome defiance of the ruling African National Congress’s black, green and gold, Malema and his red band use the color to commemorate “those who have died during the struggle for economic freedom.” The color also serves to remind the nation of the 2012 Marikana massacre, which occurred under the watch of the ANC. Berets and the occasional military fatigues convey a revolutionary Guevaran spirit, while overalls and jumpsuits show solidarity with the working class.

But Malema’s closet would surely tell a different story. Somewhere under all the layers of EFF apparel sit past political skeletons. Not so long ago, the South African media rightfully called out the disparity between Malema’s everyman speech and designer shoes. After the media salvo, it’s no mystery why Malema ditched the Gucci suits for something more palatable to the proletariat and better aligned with his platform. Although the media has since eased off, stories of “Malema’s millions” are still fresh for many South Africans.

Beyond media fodder for contradiction between walk and talk, a politician’s outward appearance can convey several messages: defiance, humility, and status among others. Leaders use their outward appearance to elevate themselves above the masses or, in Malema’s case, to walk among them. Physical appearance as political messaging is as old as politics itself. Brown University’s Jeri DeBrohun writes that Greeks and Romans alike appreciated the “potential of the body . . . as a means of marking social, political, religious, and even moral distinctions.”

But one doesn’t have to look to the ancients to witness the power of dress. In Malema’s home country, it’s now the stuff of legend. Nelson Mandela’s outfits were as numerous as his identities: camouflage to flex his strength as leader of the ANC’s military wing, a tailored suit to show his brilliance as a lawyer, and traditional Xhosa garb at a 1962 trial for inciting a work stayaway and leaving the country without a passport. That reference to tradition made deliberate connections between his royal lineage and his emerging role as a black nationalist leader. During the 1995 Rugby World Cup, then president Mandela famously donned the green jersey and cap of the Springboks, South Africa’s national rugby team and former personification of apartheid. Many whites at the time saw this symbolic gesture as an important step towards reconciliation and unification of the fragile new democracy.

Mandela’s successors continued this tradition to suit their own political needs. Thabo Mbeki’s choice of more conservative wardrobe, often suited demurely, reflected his alignment to the West. Although normally also dressed in suit and tie, Jacob Zuma built his public persona in post-apartheid society as a Zulu traditionalist, particularly in his off-duty fashion choices on public holidays.

However, Malema’s red beret does not give one a sense of reconciliation or cultural identity. For better inspiration, we have to look outside South Africa, just as Malema did. The most obvious visual comparison comes from Venezuela’s Chavistas. Before he formed the EFF, Malema expressed his admiration for Hugo Chavez’s Bolivarian Revolution, visited the country and copied, wholesale, Chavistas’s use of the color red as well as the red berets.

An even better historical example for Malema’s stylistic motivations comes from another beret-wearing revolutionary, Thomas Sankara, who EFF leaders often invoke. Until his assassination in 1987, Burkina Faso’s charismatic leader only wore clothing made from cotton grown, dyed, and woven in his home country and exuded the type of self-reliance and national pride he reflected in his anti-foreign aid policies.

In a memorable scene from the documentary “Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man,” Sankara is seen seated, smiling wide, surrounded by a group of men and women listening to him intently. Sankara lifts an arm and beckons a comrade from the crowd to come forward.

See, you’re wearing an advertisement for Levi’s,” he says playfully, as laughter ripples through the crowd. “Yes it’s well made – it’s Levi’s. But it’s American. Don’t you think we have weavers able to make them here?

During his presidency, Sankara launched the Faso Dan Fani, Burkina Faso’s national cloth, and required all public servants to wear homegrown Burkinabé clothing. But this nationalist sentiment could not stem the tide of globalization, even in the 1980s. Public servants often brought the Faso Dan Fani in a bag to work and only took it out during one of Sankara’s infamous surprise visits to government offices. Soon, people dubbed Faso Dan Fani’s as “Sankara’s coming.”

Interestingly, political dress spanned the ideological spectrum. Even more rightwing African leaders tied clothing politics to their ability to reproduce their power. In the early 1960s, Mobuto Sese Seko sought to offset his regime’s dictatorial rule through dress. He decreed a strict African dress code, later known as Authenticité, for the Congolese, to portray himself as a cultural nationalist.

Sankara’s Faso Dan Fani would probably play well with Malema’s comrades today. Amid service delivery and outsourcing protests, especially on university campuses, Malema’s worker jumpsuits complement the manifesto’s main points. If elected, the EFF promises to ensure that a “minimum of 50% of basic goods, services and products consumed in the municipality are manufactured, processed or assembled within the municipality.” Here, the EFF hopes to bring Sankara’s self-reliance to a local level.

Yet it remains to be seen whether the public and the media have bought into Malema’s image and policies. The EFF will find out in August, when South Africans head to the polls to decide whether red is their color or not.

Julius Malema’s Tailored Image

Julius Malema, at his party headquarters in Johannesburg, 31 March 2014. Image via Jerome Starkey.

Julius Malema, at his party headquarters in Johannesburg, 31 March 2014. Image via Jerome Starkey.At the end of April this year, South Africa’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), launched its local government elections manifesto in front of 40,000 people in Johannesburg’s Orlando Stadium. Julius Malema, who serves as both the party’s political and sartorial “Commander in Chief,” led the proceedings, sporting his now iconic red beret and jumpsuit. This carefully constructed image is central to the EFF’s populist allure, one the party hopes will prove strong enough to overthrow the ANC in the upcoming local elections.

The color red, berets, and plain workers’ clothing have all become potent aesthetic symbols for the EFF. Standing in monochrome defiance of the ruling African National Congress’s black, green and gold, Malema and his red band use the color to commemorate “those who have died during the struggle for economic freedom.” The color also serves to remind the nation of the 2012 Marikana massacre, which occurred under the watch of the ANC. Berets and the occasional military fatigues convey a revolutionary Guevaran spirit, while overalls and jumpsuits show solidarity with the working class.

But Malema’s closet would surely tell a different story. Somewhere under all the layers of EFF apparel sit past political skeletons. Not so long ago, the South African media rightfully called out the disparity between Malema’s everyman speech and designer shoes. After the media salvo, it’s no mystery why Malema ditched the Gucci suits for something more palatable to the proletariat and better aligned with his platform. Although the media has since eased off, stories of “Malema’s millions” are still fresh for many South Africans.

Beyond media fodder for contradiction between walk and talk, a politician’s outward appearance can convey several messages: defiance, humility, and status among others. Leaders use their outward appearance to elevate themselves above the masses or, in Malema’s case, to walk among them. Physical appearance as political messaging is as old as politics itself. Brown University’s Jeri DeBrohun writes that Greeks and Romans alike appreciated the “potential of the body . . . as a means of marking social, political, religious, and even moral distinctions.”

But one doesn’t have to look to the ancients to witness the power of dress. In Malema’s home country, it’s now the stuff of legend. Nelson Mandela’s outfits were as numerous as his identities: camouflage to flex his strength as leader of the ANC’s military wing, a tailored suit to show his brilliance as a lawyer, and traditional Xhosa garb at a 1962 trial for inciting a work stayaway and leaving the country without a passport. That reference to tradition made deliberate connections between his royal lineage and his emerging role as a black nationalist leader. During the 1995 Rugby World Cup, then president Mandela famously donned the green jersey and cap of the Springboks, South Africa’s national rugby team and former personification of apartheid. Many whites at the time saw this symbolic gesture as an important step towards reconciliation and unification of the fragile new democracy.

Mandela’s successors continued this tradition to suit their own political needs. Thabo Mbeki’s choice of more conservative wardrobe, often suited demurely, reflected his alignment to the West. Although normally also dressed in suit and tie, Jacob Zuma built his public persona in post-apartheid society as a Zulu traditionalist, particularly in his off-duty fashion choices on public holidays.

However, Malema’s red beret does not give one a sense of reconciliation or cultural identity. For better inspiration, we have to look outside South Africa, just as Malema did. The most obvious visual comparison comes from Venezuela’s Chavistas. Before he formed the EFF, Malema expressed his admiration for Hugo Chavez’s Bolivarian Revolution, visited the country and copied, wholesale, Chavistas’s use of the color red as well as the red berets.

An even better historical example for Malema’s stylistic motivations comes from another beret-wearing revolutionary, Thomas Sankara, who EFF leaders often invoke. Until his assassination in 1987, Burkina Faso’s charismatic leader only wore clothing made from cotton grown, dyed, and woven in his home country and exuded the type of self-reliance and national pride he reflected in his anti-foreign aid policies.

In a memorable scene from the documentary “Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man,” Sankara is seen seated, smiling wide, surrounded by a group of men and women listening to him intently. Sankara lifts an arm and beckons a comrade from the crowd to come forward.

See, you’re wearing an advertisement for Levi’s,” he says playfully, as laughter ripples through the crowd. “Yes it’s well made – it’s Levi’s. But it’s American. Don’t you think we have weavers able to make them here?

During his presidency, Sankara launched the Faso Dan Fani, Burkina Faso’s national cloth, and required all public servants to wear homegrown Burkinabé clothing. But this nationalist sentiment could not stem the tide of globalization, even in the 1980s. Public servants often brought the Faso Dan Fani in a bag to work and only took it out during one of Sankara’s infamous surprise visits to government offices. Soon, people dubbed Faso Dan Fani’s as “Sankara’s coming.”

Interestingly, political dress spanned the ideological spectrum. Even more rightwing African leaders tied clothing politics to their ability to reproduce their power. In the early 1960s, Mobuto Sese Seko sought to offset his regime’s dictatorial rule through dress. He decreed a strict African dress code, later known as Authenticité, for the Congolese, to portray himself as a cultural nationalist.

Sankara’s Faso Dan Fani would probably play well with Malema’s comrades today. Amid service delivery and outsourcing protests, especially on university campuses, Malema’s worker jumpsuits complement the manifesto’s main points. If elected, the EFF promises to ensure that a “minimum of 50% of basic goods, services and products consumed in the municipality are manufactured, processed or assembled within the municipality.” Here, the EFF hopes to bring Sankara’s self-reliance to a local level.

Yet it remains to be seen whether the public and the media have bought into Malema’s image and policies. The EFF will find out in August, when South Africans head to the polls to decide whether red is their color or not.

May 22, 2016

Intersectionality and economics

Intersectionality is all the rage in social movements. I am a former student at the University of Cape Town and the movement informed by intersectionality that I have observed most keenly has been the #RhodesMustFall movement there. As a result of my interest in economics, I have been wondering the ways in which what has emerged at South African universities relates to demands for economic redress and development more broadly. I hadn’t found a clear link until recently.

That there is a lack of clarity between the student movement and questions of economic transformation, is because the dominant ideological frameworks in the emergent movements — postcolonial theory and theory around intersectionality — tend to suffer from the absence of an economic analysis. (Sociologist Vivek Chibber’s work on the limitations of postcolonial theory in explaining the evolution of the Global South and his more recent critical commentary on the use of the language of intersectionality in the US presidential election speaks to this.)

Two recent developments have challenged my views. Firstly, I recently heard Feminist/Marxist economist Nancy Folbre (she is based at the University of Massachusetts, Armherst) outline her forthcoming work on “The Political Economy of Patriarchal Systems,” which seeks to push intersectionality into political economy and challenge the binary that only class relates to economic interests while gender, race, citizenship and sexuality (among others) relate merely to issues of identity.

Folbre’s work attempts to put forward a relationship between intersectionality and economic analysis, beyond looking merely at the traditional economic domain of production and exchange. It does this principally with reference to the notion of “dynamic intersectionality” and the idea that “different identities may become more salient as different opportunities for collective action to emerge.” While there is a lot more work to be done in sketching out under what terms identity relates to economic interests, the skeletal outline of “dynamic intersectionality” seemed to me to hold the prospect for an exciting positive account of a formalized representation of intersecting inequalities.

The second is the emergence of the Decolonise UCT Economics movement in South Africa, which excites me in its ambition. It is an antidote to the suffering I endured through four years of economics at UCT. Ideas like “trade unions are to blame for South Africa’s high unemployment rate” or “education is the only solution to the country’s status as the most unequal country in the world” – are all unquestioned dogmas among professors there.

An intersectional economic theory, rooted in, but also moving beyond, the traditions of radical political economy might precisely be the development left students need to pursue in countering the role of orthodox economics in perpetuating the continuing social crises that are the lived experience of South Africans (or even here in the United States where I am currently based) of different oppressions.

For me, an intersectional political-economic theory has great potential to provide a working basis for social movements that draw strength from powerful alliances of oppressed groups. This can be seen in the US presidential primaries, where we can speculate that had Bernie Sanders contested Hillary Clinton’s appropriation of the language of intersectionality to her own cynical ends, Sanders may have stood a better chance at speaking to Black and Latino voters.

In the South African context, the potential for a student-worker alliance that speaks to the intersections between worker exploitation and the issues that students have taken as their central causes (fees, racism, the continuation of colonial culture, rape culture) represents to me one of the best prospects for a united front, that up to now has not been utilized productively. In other words, it would be exciting to see what could be built on the back of the tremendous achievements of movements like #RhodesMustFall alongside university workers in winning concessions like the scrapping of outsourcing, against the backdrop of years of neo-liberalization at the university.

The ambivalence of students to participate in regressive, opportunistic movements like the #ZumaMustFall campaign suggests strong and principled analytical capacity. (#ZumaMustFall emerged soon after South Africa’s sudden currency depreciation, bringing about public uproar from mainly white South Africans, who took to the streets, with their poodles and slogan marked yoga mats, to protest their trips to Europe becoming more expensive.) This mirrors in some senses (perhaps through a shared critique or general skepticism of those who wish to venerate the South African constitution as the basis for all efforts at realizing progressive change) the interventions of more principled members of the union movement (see here). It would be exciting if these forces could be united in the aim of more consistent public left opposition to social crises of national importance.

Economics has an important role in the analysis of the contemporary national and global order, it thus holds an important role in questions of ideological orientation and strategy for social movements. An intersectional economic theory holds the prospect of informing the development of a more complete analysis and strategy for social movements that speak to broad coalitions of oppressed groups interested in furthering progressive agendas. That such a theory doesn’t seem to exist damages the coherence of both, movements that seek guidance from an analysis emphasizing a ‘class first’ approach, and those that pursue a ‘race first’ approach (either explicitly or implicitly). These tensions are clear from recent public debates about reparations for slavery in the US (see here and here).

Another way of making this point is that an intersectional economic theory cannot be truly intersectional without successfully challenging the false binary, discussed above, that seems to be the main aim of Folbre’s forthcoming work. Further, developing such a theory ought to be a central goal of progressives interested in dismantling multiple oppressions and would be a valuable addition to the exciting social movements that have emerged recently. With this in mind, I hope movements like Decolonize UCT Economics will move forward in centrally pushing for a revised curriculum with a bigger place for radical political economy. It will only be through a better informed public debate that the aforementioned tensions can be resolved, and if done successfully, it will be to the benefit of meaningful progress in realizing truly emancipatory political projects.

May 21, 2016

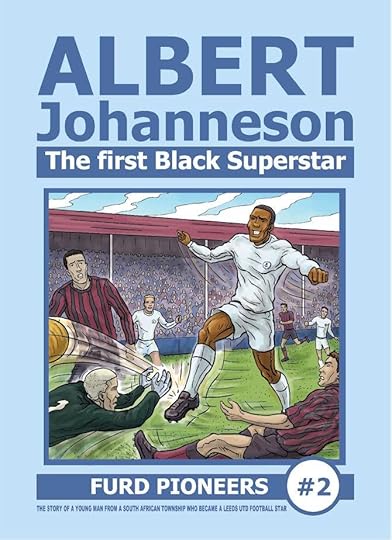

Black players won’t be a big deal at today’s FA Cup Final. Back in 1965 it was

When Manchester United and Crystal Palace take the field in the English F.A. Cup final in London later today, the presence of black players on either team won’t be a big deal. But back in 1965 it was. That’s when Albert Johanneson became the first black footballer to play in an F.A. Cup Final, for Leeds. (Leeds lost to Liverpool.) Like many early black sports pioneers Johanneson has been largely forgotten in both his home country of South Africa and in the U.K., where he played and lived most of his life.

After almost a decade playing for Leeds, Johanneson (born in Germiston outside Johannesburg) played a season for fourth division side York City, returned to South Africa to play for Glenville FC (in the Indian and coloured Federation Professional League) for a season before returning to the UK. He never played professionally again and died at fifty-five in Leeds, in poverty, having struggled with alcoholism for much of his life.

This his time last year, saw the publication of “Albert Johanneson, the first Black Superstar.” One of the things that stood out for me in the research material on Johanneson was how fans and teammates described him shrugging off insults, always being friendly and humble and seeming unaffected by the (often intense) racial abuse he was confronted with. I’m sure decades of this must have affected him, though, and the later alcoholism and personal problems no doubt, reflect that. Imagine the exposed position he was in as, usually, the only black man in the stadium, never mind on the field.

I first came across Johanneson’s life story in 2009 while doing illustrations for an exhibition called ‘Offside’ at the District Six Museum and funded by the British Council. Johanneson was one of forty odd players illustrated at life size for the exhibition timed to coincide with the 2010 World Cup taking place in South Africa. ‘Offside’ intended to celebrate the contribution of African footballers who had played in the European and American leagues and examine their varied experiences depending on race, gender and time-period.

The UK-based FURD (Football Unites Racism Divides) was one of the partners for the Offside project and Howard Holmes, FURD’s founder, contacted me later about a project related to the Offside show. He wanted to do football comics about these early sports pioneers to celebrate their achievements but also show the damage racism had done to their lives and careers.

We started with the Ghanaian Arthur Wharton, a major sporting figure in the 1880s in Britain credited as “the world’s first black professional footballer.” Wharton’s story was so early and unusual, and there are so few photographs of the sports of the period that he was almost totally forgotten. Howard helped to organize a proper headstone for his grave and did some work with his granddaughter. We completed ‘Arthur Wharton, Victorian Sporting Superstar’ now two years ago.

For the second of these ‘FURD Pioneers’ comics Howard suggested Albert Johanneson, to coincide with last year’s F.A. Cup final, which happened to mark fifty years since Johanneson’s appearance in 1965. The Albert Johanneson comic was launched in the UK last year and we launched it in South Africa at the District Six Museum’s Homecoming Centre on Human Rights Day (March 21st) and then on Freedom Day, April 27th, at Sophiatown’s Trevor Huddlestone Memorial Centre in Johannesburg.

Many of us in South Africa grew up on the old British football comics like Roy of the Rovers, and to show some more relevant history and character stories in a comic book format is very satisfying. We feel that the stories of sporting pioneers like Johanneson and Wharton (and many, many others) can, told, in this format, reach a wide audience and entertain readers while reinforcing an anti-racism message.

We are trying to distribute the stories as widely as possible, to this end the first comic is available in digital format on the FURD website and we have sold and given away thousands of copies of both comics now. Contact FURD or the District Six Museum for copies and more information.

May 20, 2016

Weekend Music Break No.95 – Afro-Europe special!

Fresh of a trip to the UK and Germany, with stops in Afro-European strongholds of London and Berlin, I thought I’d theme this week’s Music Break around some of what I saw and heard there. So enjoy this brief (and not comprehensive by any means) trip around young Afro-Europe, with stops in London, Paris, Berlin, Lisbon, and Rome.

Music Break No.95

1) MHD was a revelation for me on this trip, first getting hipped to his #AfroTrap series by a friend in Bristol, and then being treated to an onslaught of it in Berlin for their Carnival weekend. 2) Belly Squad out of London come with a bit of a naughty song and video to show the youthful energy of the UK-Afrobeats scene. 3) Amsterdam via London’s Jaij Hollands’s gravely flow is taking Afrobeats in a little harder edged direction. 4) Maître Gims’ Sapés comme jamais was also on repeat in Berlin, also coming from the Paris scene. 5) YCEE who bursted on to the scene with Jagaban last year takes his new video to the streets of London, showing how many artists, even those based in Africa, prefer to go to London for their aesthetics. 6) Aina More is killing it over this beat by DJ Juls! 7) On the other side of Berlin, Daniel Haaksman recruits Spoek Mathambo for this chugging Mbaqnga influenced Afro-House jam. 8) Lisbon’s Throes + The Shine recruit Argentina’s La Yegros for this high tempo Afro-Latin-Rock number. 9) A few years old classic out of Rome, Pepe Soup’s Pump Tire! 10) And finally, the absolute Dona of the Lisbon Afro-Electronic scene in her Boiler Room Lisbon appearance to take you out!

Happy Week’s End!

Music Break No.95 – Afro-Europe special!

Fresh of a trip to the UK and Germany, with stops in Afro-European strongholds of London and Berlin, I thought I’d theme this week’s Music Break around some of what I saw and heard there. So enjoy this brief (and not comprehensive by any means) trip around young Afro-Europe, with stops in London, Paris, Berlin, Lisbon, and Rome.

Music Break No.95

1) MHD was a revelation for me on this trip, first getting hipped to his #AfroTrap series by a friend in Bristol, and then being treated to an onslaught of it in Berlin for their Carnival weekend. 2) Belly Squad out of London come with a bit of a naughty song and video to show the youthful energy of the UK-Afrobeats scene. 3) Amsterdam via London’s Jaij Hollands’s gravely flow is taking Afrobeats in a little harder edged direction. 4) Maître Gims’ Sapés comme jamais was also on repeat in Berlin, also coming from the Paris scene. 5) YCEE who bursted on to the scene with Jagaban last year takes his new video to the streets of London, showing how many artists, even those based in Africa, prefer to go to London for their aesthetics. 6) Aina More is killing it over this beat by DJ Juls! 7) On the other side of Berlin, Daniel Haaksman recruits Spoek Mathambo for this chugging Mbaqnga influenced Afro-House jam. 8) Lisbon’s Throes + The Shine recruit Argentina’s La Yegros for this high tempo Afro-Latin-Rock number. 9) A few years old classic out of Rome, Pepe Soup’s Pump Tire! 10) And finally, the absolute Dona of the Lisbon Afro-Electronic scene in her Boiler Room Lisbon appearance to take you out!

Happy Week’s End!

Monochrome Lagos

Lagos is known for being an assault to the senses: Swarms of bright yellow danfos maneuver stridently through lanes, and in a manner not quite unlike bumblebees — carrying a weight that seems optimistic at best. Dust often cakes the skin, but is streaked by drips of perspiration, courtesy of the blaring sun overhead. An ever-increasing soundtrack of voices booms in the background, emitting from seemingly every direction and without a recognizable source. Ever oscillating between exuberance and excess, the city is described as cacophony of sights and sounds—varying in levels of logic and function, always full of movement and energy.

Yet, in Logo Oluwamuyiwa’s ongoing project Monochrome Lagos (2013—), we encounter a Lagos that is rendered quite differently. A resistant body of work, Monochrome Lagos presents an alternative visual vocabulary through which to comprehend this city — one that strips Lagos down to its component parts, as an encounter between the individual and the built environment. Limiting his palette to black and white, Oluwamuyiwa presents high-contrast images that demonstrate a close attention to line and architectural forms. A rumination on presence and absence, Monochrome Lagos muffles the sensorial tropes of Lagos, bringing to the fore the spaces wherein once can find solace within the city.

Drawing on a photographic lineage of documentary and street photographers such as Robert Frank, Gary Winogrand, and fellow Nigerian J.D. Okhai Ojeikere, Monochrome Lagos attests not only to the individual narratives of Lagos’s inhabitants, but also Oluwamuyiwa’s own artistic development within the medium. From the outset, one can envision this photographer as a flâneur of the digital age, presenting an intuitive cartographic study with an ever-heightening attention to light, line and form. Rather than proposing a block-by-block visual analysis of the cityscape, Oluwamuyiwa embraces the complexities and inconsistencies of Lagos, and often perched on the back edges of buses, captures mundane objects and quotidian interactions from a quasi-aerial perspective.

While a critical mass of images seems to accrue around the architectural structures of the Third Mainland bridge, Oluwamuyiwa attests to the psychological meaning of the bridge solidifying its central position in his work, not only its function as the connection between Lagos’s Victoria Island and mainland. Also featuring images that abstract the various texts (signs, advertisements, logos, etc…) of the city, Monochrome Lagos, hints at a dialogue between word and image that could re-envision the working structures of the photo-essay.

Perhaps the only element of this project that confirms to reigning expectations of Lagos is the tremendous number of narratives it represents—to date it includes more than 200 photographs. Yet, because Oluwamuyiwa frames this project as simultaneously a digital archive and poetic process, such numbers seem well suited to its location on platforms like Instagram and Tumblr. This decision also positions Monochrome Lagos quite uniquely: its aesthetic treatment of mundane objects as social sculptures is reminiscent of fine art photographer Edson Chagas’ “Found Not Taken” series in Luanda, yet its unifying mission also brings to mind Fati Abubakar’s viral Bits of Borno Instagram project. In a recent conversation with Tate curator Shoair Mavlian, Oluwamuyiwa spoke to the importance of Monochrome Lagos’s photographic lineage and social impact online. He stated, “the urban space is inexhaustible in its narratives” — a sentiment one can undoubtedly perceive through every image in this series, as well as its collective bearing on larger visual discourses of Lagos.

* Oluwamuyiwa’s first exhibition in the United Kingdom, “It’s Also a Solo Journey,” is on view at News of the World until 22 May 2016. This exhibition forms part of the first session of Future Assembly, a London-based artists’ development program for emerging practitioners from Africa and its diaspora, founded by Hansi Momodu-Gordon, and co-curated with Orla Houston-Jibo.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers