Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 226

March 24, 2019

The Collapse of Oil for Insecurity

Image: United States Marine Corps, via Flickr CC.

The crisis in US-Saudi relations triggered by the state sponsored murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi might seem unrelated to Venezuela���s current turmoil.

Commentary on both crises has of course noted the centrality of oil. Whereas Venezuela���s civil conflict allegedly stems from mismanaged oil revenues, the Khashoggi crisis is represented as a consequence of Washington���s tragic ���oil for security��� deal with Saudi Arabia, the idea that the US reluctantly but imperatively protects the region���s oil and, in return, the Saudis buy US weapons to keep thousands of defense workers employed.

In many ways, however, both of these crises are related to a greater crisis, the growing crisis of oil���s ���overabundance.��� As such, these crises call into question the possible collapse of political and economic arrangements created in the 1970s that have been disrupted by a recent technological revolution in US oil extraction. For four decades, hyper-militarization and permanent war in the Middle East and North Africa were the primary conditions that allowed wealth and power to be extracted from oil. These means ��� oil-for-insecurity ��� no longer appear to be working.

What ���oil for security���?

���Oil for security��� represents a powerful but flawed narrative of US relations towards the greater Middle East for a number of reasons. First, there���s no documentary evidence that any such deals formally exist, as political historian and Saudi specialist Robert Vitalis has argued.

Second, oil-for-security narratives don���t add up. Washington was much more directly involved in the day-to-day security of the Saudi, Iranian, and Libyan monarchies in the 1950s and 1960s, well before the US became dependent on foreign oil. In Libya, British and US ���protection��� preceded oil production by over a decade. Washington has also shown just as much commitment to Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Israel, Turkey, and Pakistan, countries with little or no oil production. During the Cold War, Morocco received more US military aid than any other country in Africa besides Egypt.

Third, oil-for-security has been a losing proposition for almost everyone involved. The Iraqi, Iranian, and Libyan monarchies were all overthrown and replaced by regimes that openly challenged Washington���s policies. More recently, the US army concluded that Iran was the only country to benefit from the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq. By 2014, the American occupation of Afghanistan had already cost more than the Marshall Plan, and yet the Trump administration now seems set to withdraw on almost the same peace terms that the Taliban offered before the 2001 invasion.

Nor has oil-for-security been very good for the region���s security. Today the Middle East boasts three of the five deadliest conflicts since the end of the Cold War, and since 2012 it has witnessed more deaths from armed conflict than all other regions of the world combined.

Fourth, oil-for-security narratives obscure the ideological nature of US policies. In the 75-year history of America���s ���awkward entanglements��� and ���unfortunate interventions��� in the Middle East, Washington has never once found itself durably if regrettably allied to any of region���s oil-producing populist socialist republics like Algeria, Libya, Syria, Iraq, or Iran. It hardly needs to be said that these were in fact the regimes Washington most often contained, confronted, or changed through force.

Finally, energy security does not require oil-for-security entanglements. China has managed to develop the world���s largest economy and now boasts the planet���s largest fleet of motor vehicles, all without invading or occupying a single oil producing country.

Oil for Insecurity

The problem with ���oil for security��� theories is the common assumption that oil politics is defined by oil���s natural scarcity. Hence the frantic efforts to control it, especially in the Middle East and North Africa. But as historian Timothy Mitchell has demonstrated, oil���s role in the making of the modern world has been defined by the exact opposite problem: there���s always been too damn much. The ability of companies to extract wealth from oil and the ability of governments to draw power from it has always depended on creating a sense of oil���s scarcity.

In the early decades of oil, profits and power were created through domestic monopolies and collusion between imperial powers. After World War Two, a cartel of the dominant North Atlantic oil firms colluded with their home governments to managed oil���s scarcity. This system gradually came into crisis in the 1950s and 1960s. The major producer states began to demand more equitable profit sharing agreements and more involvement in the technological, scientific, and managerial aspects of extracting, refining, and exporting oil. Soon ownership of oil reserves and infrastructures were being aggressively renegotiated, if not outright nationalized, across the postcolonial world.

This crisis of Western power and corporate profitability in the late 1960s was resolved when a new means of manufacturing oil���s scarcity emerged in the Middle East and North Africa: war. In the wake of the 1967 and, more importantly, the 1973 Arab-Israeli wars, the major international oil companies saw their relative rates of profit surge. This scarcity had nothing to do with the so-called Arab oil embargoes. Rather, it was the power of permanent insecurity in the Middle East and North Africa to induce a global sense of scarcity, and so raise prices.

By the end of the 1970s, a constellation of new and exacerbated conflicts had developed from the western edge of the Sahara desert to the western Himalayas. With the world���s major oil reserves under constant threat from political instability, permanent war and hyper-militarization had the effect of creating unprecedented rates of profit.

All of this was a happy coincidence for the oil companies. The real drivers of permanent insecurity across the Middle East and North Africa stemmed from two other developments: one, Washington���s post-Vietnam policy of indirect control, proxy wars, and Communist containment in the postcolonial world (e.g., the Safari Club); and two, the imperative to find new markets and sources of financing for weapons manufacturers. The geographical confluence of these interests in the Middle East and North Africa could be more accurately described as oil for insecurity.

The Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan administrations consistently pursued policies that destabilized the Middle East. Wars in Western Sahara, Chad, Iran-Iraq, and Afghanistan were all deliberately exacerbated; pariah regimes in Iran and Libya were aggressively confronted; and conservative authoritarian allies in Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan were lavishly rewarded with weapons and aid.

Flush in petrodollars, regimes across the Middle East responded to the intensification of inter-regional rivalries by equipping themselves with either North Atlantic or Soviet-made weapons depending on their Cold War (non)alignment. For North Atlantic arms manufacturers, oil-for-insecurity was also the solution to their own post-Vietnam crisis of profitability. In 2017 dollars, Middle East arms imports went from $7.5 billion in 1971 to over $30 billion in just six years. By the end of the 1970s, Middle East represented the vast majority of countries whose military expenditures registered as ten percent or more of GDP. The ten countries with the highest ratio of military expenditures to central government expenditures in 1982 were all in the Middle East. Today, most governments in the region continue to outpace all other ���middle income��� countries in terms of military spending and arms imports.

As economists Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler have consistently demonstrated in a series of studies spanning over three decades, the relative profitability of the major oil and armament companies since the late 1960s has been closely tied to instability across the region.

The Crisis of Overabundance

Though the Islamic State���s resurgence in Syria, Iraq, and Libya from 2014 onward seemed to indicate an intensification of regional instability in a number of key oil producing zones, the relative profits of the major petroleum companies actually entered a period of unprecedented decline. So what happened?

In the fifty years since the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, there have been two cycles of scarcity and abundance driven by permanent insecurity in the Middle East and North Africa: the first from the mid-1970s through the 1990s; the second from 2001 to now.

The first cycle of oil-for-insecurity pushed oil prices to unprecedented levels in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which incentivized new frontiers and technologies of extraction (e.g., Alaska and the North Sea). An increasing glut of oil worldwide followed. Prices finally crashed in 1986, taking the Soviet Union down with them.

The end of the Cold War soon became a period of sustained crisis for the major oil and arms companies. It was a world of base closures, reduced Pentagon budgets, and Middle East peace processes (e.g., Western Sahara and Palestine). As the neoliberal Democratic Party sidelined labor and embraced those sectors within capitalism that thrive on peace and security (tech and services), the reactionary political forces of the neoconservative movement doubled down on the old alliance of oil, arms, and Middle Eastern insecurity to restore their political fortunes. The Bush-Cheney administration���s invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq were in fact stunning successes in one respect: the peace crisis of the 1990s was ended and relative profitability was restored to oil and defense.

The major oil producing states ��� those not engulfed in war or under US sanctions ��� transformed these profits into political power. An ironic example was Venezuela. Hugo Ch��vez���s ability to conduct one of the most ambitious experiments in socialist populism since the end of the Cold War was made possible by the very imperialism he regularly denounced.

But the success of oil-for-insecurity from 2001 to 2012 proved to be its unmaking. New yet expensive technologies for onshore and offshore extraction, above all, hydraulic fracturing (���fracking���), seemingly became financially viable as oil prices finally returned to levels not seen since 1980. Production in the United States began to surge. And so this is how the second cycle of oil-for-insecurity, like the first, created the conditions of its undoing ��� by producing too damn much.

Ch��vez, who died in 2013, would not live to see the 2014 collapse in oil prices and the squandering of his legacy under Nicol��s Maduro. But like all political and corporate leaders who had grown dependent on oil-for-insecurity, Maduro struggled to adapt to a new reality of implacable overabundance. Nor did it help that US sanctions have made it impossible for Venezuela to restructure its debt.

Today���s overabundance crisis has proven exceptionally resilient. Civil wars in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen were intensified by foreign interventions in 2014 and 2015 yet prices continued to crash. More recent effort to raise prices through traditional mechanisms ��� OPEC-Russia quotas and sanctions on Iran and Venezuela ��� have so far proven ineffective. As fracking becomes cheaper, efforts to restrict oil and so raise prices appear to be automatically offset by increased output from North America.

The demise of oil-for-insecurity raises questions as to the kinds of strategies that will emerge to adapt to this new reality. It is tempting, after all, to think that we are seeing early iterations of a new politics of overabundance in the neo-authoritarianism of Putin and Trump. That might be giving them too much credit, however. There are still immensely formidable incentives in the world today ��� at the level of corporate profits and political power ��� to see major oil producing states like Venezuela cut off from markets through sanctions, civil conflict, or both. Hence the world should be concerned when it sees leaders in Washington and Moscow effectively colluding to exacerbate Venezuela���s crisis.

March 23, 2019

Yacht rock or slave ship rock?

A still from the music video Toto's music video for "Africa."

In February 2018, the American music magazine, ���Billboard,�����published��an oral history of the song ���Toto��� by the California soft rock band, Toto. The song, heralded as ���the internet���s favorite song��� (that��is a meme in itself), has often been derided for��its ridiculous lyrics, leading to all kinds of deconstructions of its meanings.�� In an interview with Billboard, the critic Carl Wilson made this remark:�����…��it���s too dumb for anybody to insult their own intelligence by mounting a serious critique of [the song]. Like, you���d be the biggest fun-killer in the world with your politics if you were like, ���I want to seriously talk about Toto���s ���Africa��� now.������

The problem is we need to seriously talk about��Toto���s�����Africa.���

At the end of January��2019, the American pop group��Weezer��released an album of cover songs��(the ���Teal Album���). The tracks on ���The Teal Album��� includes,��of course, ���Africa,��� which among the other covers has gotten the most attention.��Months earlier, when��Weezer��released the ���Africa��� cover as a single, it climbed to the top of the Billboard charts in the United States. Then the band choose to parody themselves when they invited parody-singer Weird Al��Yancovic��to lip synch the lyrics��in the music video��of the cover. (At last count, that video has been viewed nearly 9 million times on YouTube alone.)

The original ���Africa��� was first released by Toto in 1982 and has been��covered��by a range of groups and artists since; even��GZA and��Madlib,��Nas��and��Xzibit��have sampled the song. But it is the��Weezer��version that has had most cultural significance. How the cover version came about is also a story at once strange and befitting the social media age: the result of a teenage girl���s imagination. Mary, a 14 year old girl from Cleveland, set up a Twitter account demanding that��Weezer, her favorite band, cover her new favorite song ���Africa.��� It wasn���t entirely organic. It��took mainstream music writers��to��help make Mary���s request viral.

The most obvious thing to say about��Weezer���s�����Africa��� is that the cover version brings nothing new to the table, only switching the trademark percussions in the original for subtle barbed wired (yet somehow tame) guitars in the new version. And even worse, it becomes clear that the lyrics only pinch a figment of most people���s imaginations.

How did Toto come up with the song ���Africa��� in the first place? None of the band members had been to the continent when the song was made. As drummer Jeff Porcaro, is quoted (on Wikipedia): ������ a white boy is trying to write a song on Africa, but since he���s never been there, he can only tell what he���s seen on TV or remembers in the past.”

The only thing (we hope) the band knew about Africa was that their ancestors violently took man power, culture, and perhaps most visibly, music from the continent.

The biggest problem with ���Africa��� is that ���the whole weird history of American culture is in this song somewhere,��� as Rob Sheffield��writes��in��Rolling Stone. Sheffield doesn���t say exactly what this history of American culture is. We assume he means the fact that the slave trade is an important, yet gruesome part of that history.

The song maintains a dance between black and white, both literally since all walks of life have danced to it, and metaphorically since the song has been covered by all kinds of people. The band were practically outsiders in the record business when they recorded it, and the song is embraced by both low and high culture. The way in which the song has a ���brave��� but indeed grimy sense of nobility towards Africa as a continent hammers the point even further. Most importantly, the ridiculous lyrics mean so much��more than what they seemingly say.

When Toto made ���Africa,�����Toto��were hipsters. Toto members got their start as session musicians for Steely Dan, the eminent California via New York hipsters. Toto was basically a kind of Steely Dan on steroids. Later yacht rock, of which Steely Dan and Toto are two of the biggest exponents from the late 1970s and early 1980s, was made a comeback by hipsters from the early 2000s.

After all the word ���hip��� comes straight from the word ���hepi��� in the still thriving��Senegambian��language Wolof.��The vernacular word were first in use among the enslaved in the plantations in the colonies, before it became common in pop culture hundreds of years later. The word��means something in the vein of ���to open one’s eyes�����in Wolof.

In the lyrics to ���Africa��� a part of this unsung history becomes even more evident.��This is not just about a white man longing for his faraway love as the visuals of the original music video (that its stereotypical images) suggests. When the chorus begins with: ���It’s��gonna��take a lot to take me away from you��� they���re talking about being taken away from Africa, aren���t they? And, of course,��they are telling the tale from the perspective of an American black man, as white hipsters so often do.

So now we are starting to get to the core of the song, even if we have Carl Wilson���s comment about mounting a serious critique of ���Africa��� in custody. In fact, Wilson should be the last one to speak. His main claim to fame is the little book, ���A Journey To The End Of Taste��� (in Bloomsbury���s 33 ��� series) which amounted to a hate letter to C��line Dion���s ���Let���s Talk About Love,��� another album all music critics dislike, and tons of everyday people love. Shouldn���t music criticism be about breaking with the consensus among critics? Shouldn���t we try to question what we already like?

Why shouldn���t we also try to make sense out of what we don���t understand? As such, this is not so much a critique as an attempt to make connections. ���Why should a man deliberately plunge outside of history?,��� a character in the late great Ralph Ellison���s monumental novel��Invisible Man��asks. When we take a trip out of American history, we will most likely see a more complete picture of that history when we return to it.

Here���s my take: The song ���Africa��� is about the United States of America, and it is that country���s history and not the continent that these songwriters hadn���t been to. ���Africa��� is probably more about the Atlantic slave trade than it is about Africa.

The slave trade was and continues��to be central to American history, culture and identity. African-Americans invented musical intersections such as spirituals, blues, jazz, rock and hip hop. When we hear white American men sing about Africa, we must stop and think what they have earned from the continent. Their only direct experience with anything African is by far African-Americans, and the piece of culture that wasn���t taken away from the previously enslaved. So with lyrics depicting an imagined African life, like how ���Kilimanjaro rises like Olympus above the Serengeti,��� some��ancient melodies, an old man and a boy, some of these connections start to rise to the surface.

If the lyrics seem deceptively general, then the video is even more confounding. Close-ups of the doughy front man, David Paich, in an office littered with encyclopedias alternate with the band playing the song on a giant book simply titled ���Africa.��� Soon, the stereotypical paraphernalia make an appearance — zebra print background, random masks, a black arm is raised with a spear in hand, a taxidermy tiger head and some potted plants seem to pass off as dense African shrubbery. A sexy but befuddled black woman watches on in a swivel chair. The climax of the video is absurd as the spear pierces a wall, books topple, the weird lady���s glasses are crushed, and eventually a book (presumably the book called Africa) burns down to the crescendo of ���I bless the rains,��� ���I bless the rains,��� and on and on …

The closest readings of the song���s lyrics have been done by��humorist Steve Almond, who��down the lyrics in this video, and by��musicologist Wayne Marshall, who wrote��a long post��about the ���Africanness��� of the actual tune.��And mainstream critics, when they tried, have always been befuddled by the video. Pop culture essayist Chuck��Klosterman��probably has the funniest interpretation of the lyrics and the video:

Whenever I���d listen to Toto���s ���Africa���, I always assumed the song was using Africa as a metaphor. However, this video suggests the song is literally about the continent itself (and maybe about an African American travel agent, although I can���t be sure), so now I���m confused. It definitely has a globe, though. Also, what does ���Africa��� have to do with the movie��Fatal Attraction? I swore I just heard some VJ talking about that movie (and its relationship to Toto). I struggle.

The slave trade is central not only to American history but to all Western history to the point that even the small country of Norway where I come from was partaking in the spoils.��Although very few people, let alone Norwegians, knows anything about��Norway���s part in this��history, it involves more than the benefits of sugar, cotton and gold. This summer, filmmaker, playwright and activist Ole��Tellefsen��starts shooting the dramatized documentary ���Slaveskipet��� (The Slave Ship) about a Norwegian slave ship, which sunk to the bottom of the sea just outside��Arendal, a small town on the southern coast of Norway. The filmmaker reveals that he has many similar stories about other ships that were in action.

���It might be asked what has��this��or any fairy tale to do with a world stricken, starving, and half insane; or with the relations of Africa to Europe and America,��� W.E.B. Dubois, the African-American political scientist and activist, asked in the 1950s. What���s ���this��� he talking about exactly? The question is ambitious and the answer is troubling. But if ���Africa��� is a fairy tale, then the answer is the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

March 22, 2019

Africans are largely on their own facing climate change

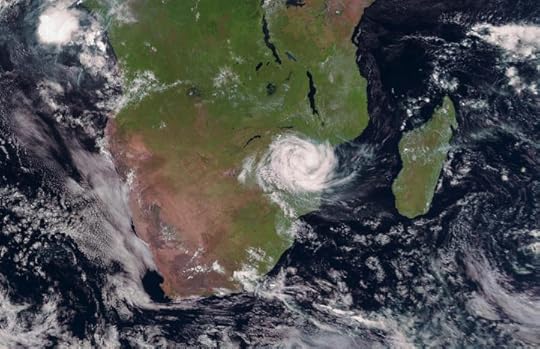

Tropical cyclone Idai over Mozambique as captured by Meteosat-11 at 09:15 UTC on 15 March. Image: Copyright: 2019 EUMETSAT

On 15 March 2019, an intense tropical cyclone hit land at Beira, Mozambique. The cyclone also brought severe winds and rain to Madagascar, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Across the region, the storm has been so severe that it has been extremely difficult to get help to the people who need it. The death-toll in both Zimbabwe and Mozambique is steadily rising ��� but the full extent of the damage is not yet knowable, as floodwaters are still high and conditions on the ground difficult.�� Roads, villages, and suburbs have completely washed away.�� In both Mozambique and Eastern Zimbabwe, it is still raining days later, and the wind has not stopped blowing ��� conditions that make it extremely difficult for rescue helicopters to fly.

Nonetheless, help is beginning to reach the region, from small-scale local efforts to much larger scale regional and international operations. As a Zimbabwean anthropologist living outside of the country, what I have seen and heard is extraordinary, and tells us something about Zimbabweans expectations of the state���s response to such a massive emergency; and their relationships with one another.

Zimbabwe is still immersed in a long term politico-economic crisis. In November 2017, citizens across Zimbabwe celebrated the end of the era of President Mugabe, following a coup-that-wasn���t-allowed-to-be-called-a-coup. After a long limbo period, previous Vice President Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa (ED to locals) was voted into Presidential power in a disputed electoral process in August 2018.

But ED���s rise to power and his consolidation of it has not been smooth. Following protests against the 2018 election results, the Zimbabwean army opened fire on crowds, killing six. It was a harbinger of things to come, however: in January 2019, when the government massively hiked fuel prices in an attempt to bring some money into a collapsing economy, people took to the streets in protest. The army was mobilized once again, and this time the death toll was higher, and came with multiple arrests.

It was into this set of conditions that Cyclone Idai rolled: climate change doesn���t care what stage of political crisis a country is experiencing. And across Zimbabwe, people came together, and came together fast. Almost immediately, collection efforts were set up in large urban areas. My social media feed showed hundreds of pictures of people in queues ���not to obtain petrol or cash this time, but rather to give donations towards the people in Manicaland whose lives have been devastated by Idai. In a country with massive unemployment, an insane economy which effectively has a double currency, and where political violence has been the order of the day for months, people came together. In droves. To give.�� From food to pots to pans to blankets to money to services. In Victoria Falls, on completely the other side of the country, a team of white water rafting guides, supported by major telecoms provider Econet, ��set off to see if their expertise could assist with rescue operations in the floodwaters. In Harare, the Highlands Presbyterian Church became a hub for private donations. Zimbabweans mobilized, and mobilized fast, across the entire country.

The government acted too, deploying the military to Chipinge and Chimanimani: this time to bring help rather than quell protest. Food aid has been forthcoming, and attempts are certainly being made. But ZimRights, a grouping of civil society organizations, has expressed deep concern at the politicization of the response, and a strong plea that the processing of international humanitarian aid at border posts be fast-tracked, as so far it has been far too slow and bureaucratized.

It���s no surprise that Zimbabweans don���t trust the government and the army to act in citizen���s interests. One of the things I have seen in the research I���ve undertaken in Zimbabwe is the ways in which, aside from moments of extraordinary interference and violence, the state has receded from people���s lives. There is little expectation in urban or rural Zimbabwe of the sort of services that protect socioeconomic rights: access to water or electricity, refuse removal and sewage services, road maintenance, or even the most basic healthcare. While this isn���t necessarily that different to, say, many townships in South Africa (aside from the healthcare), it is different in scale ��� nationwide ��� and different in the extent of its��� normalization. South Africa sees hundreds of service delivery protests a year. Zimbabweans no longer expect anything much from government, and have only protested when the fuel hike threatened to bring about truly unsurvivable conditions.

For decades now, Zimbabweans have been making their own plan. And in the process, communities have changed.�� Wherever you live, neighbors know neighbors. They have to, to make a plan to share a borehole; or to have someone keep an eye on children while mothers, fathers and grandparents partake in some way in the informal economy.

Cyclone Idai���s impacts will remain devastating for a long time to come. But it has shown us the ways in which ordinary Zimbabweans will move to protect the lives and livelihoods of other ordinary Zimbabweans. Idai is a large scale disaster, requiring a large scale response. But the huge disaster that is Idai was preceded by continual day-to-day socioeconomic crises for all citizens. As a result, every single day, on much smaller scales, Zimbabweans are accustomed to working with one another and making a plan. The country���s deep crisis has resulted in tighter forms of community, and greatly increased networks of reciprocity, that largely bypass state involvement. Such a set of conditions meant that when Zimbabweans in other parts of the country heard about conditions in Manicaland, they came together in unprecedented ways. Zimbabweans have realized that the state���s shortcomings can only be filled by ordinary people���s actions; as such, despite poverty, there is a sense of personal responsibility felt towards other citizens when things go terribly wrong. The question that remains is whether the new dispensation will pick up the reins or will continue to leave ordinary Zimbabweans to fill the gap.

Protest art in Sudan’s uprising

Man with flag in boxi artwork jaili. Image credit MUST.

This post was written by an anonymous artist.

Street protests over the past few weeks against��President Omar al-Bashir���s military dictatorship��have been accompanied by an explosion of��Instagram��protest art��from��inside��Sudan and��its��diaspora.

In the 30 years of Bashir���s military dictatorship, there has never been a��popular��uprising��comparable to the one that has been shaking the country since 19th December 2018. The artistic expressions that are��emerging��in their wake��are novel in their intensity and content, but draw on Sudan���s long history of protest art. A defiant��Bashir��has��said: ���Changing the government or president cannot be done through WhatsApp or Facebook. It can be done only through elections.�����The state���s targeting of social media suggests��otherwise.

The��use of art in��Sudani��political struggle��begins with the creation of��political cartoons in the 1950s; since then��artists��have��learned to continually adapt to different political environments. During��several decades of��authoritarian��rule, artists resorted to self-censorship and communicated their political messages subversively to supersede censorship and prosecution. Those who didn’t obey those rules suffered consequences.��Traditional media channels including radio, television and newspapers fail to provide a forum to discuss political issues due to government��repression.

Social media has become not just a tool for communication,��but an outlet for greater freedom to express political opinions. At��the forefront of all this is the��Sudanese Professionals Association. Virtual public spaces��like Twitter and Instagram��have given artists and activists alike the chance to voice opinions on a global platform while having the option to stay (semi-) anonymous without fear of persecution. It has also given the opportunity to those in the diaspora (or otherwise unable to march in the streets) to participate in the civil uprising.

Sudani��Twitter,��with users��in Sudan��and the��diaspora,��is filled with (graphic) audiovisual content exposing��the violence��that the peaceful protestors from Atbara to��Ghaybesh��are met with while chanting�������������������������������������� (freedom, peace, justice). The hashtags��������_��������������_����������#�� (Sudan���s cities uprising)����������_����# (just fall) and #sudanrevolts��are a way to��mobilize��the��protest culture��and fuel��discussion.��Those documenting��the protests and the ongoing human rights violations are a thorn in the eye of Sudan���s ruling elite who have cut access to social media.��Anonymous��reacted to this by attacking official websites and archiving audiovisual proof for the state���s violence.

Artists appropriate iconic images and in many cases, increase their art���s��shareability��and global reach.��One image that has been remixed,��is that of��the arrest of a protestor on a��boxi��(pick-up-truck used by the police and National Security/Intelligence Service) still holding the Sudanese national flag up in the air while lying on the back of the car.

More disturbing details are coming out concerning the��detention��of thousands of��people��who have been picked up from the streets and from their own homes by police and security forces on a daily basis���not to mention those��killed through torture and live ammunition.

Artists have been documenting this through depicting snapshots of events and portraits of victims. Amani and Samir, two protestors who were attacked by the police, lost their eyesight and became icons of the bravery, strength and endurance of the people demonstrating in the streets. Artworks honoring them have been widely circulated. Another protestor who became frequently portrayed is Mohamed Al��Masri,��who lost one of his hands during the protests in December but nonetheless was seen marching in the streets again in January.

Mohamed al masri hands. Image via Instagram.

Mohamed al masri hands. Image via Instagram.The government has responded to the deaths of protestors by claiming that��unidentified��people are responsible for these casualties. Government forces even detained a donkey that was marked creatively with a protest chant mocking the government. This moment, recorded on camera, presented a perfect occasion for artists to mock��the government��even further. Meanwhile al-Bashir stated that he is��satisfied with the executive forces�����actions.

In the midst of the accusations of human rights violations, Bashir held a pro-government “1 Million People March” at Green Yard, dancing on stage in front of governmental employees.��(Dancing with his��walking cane,��is one of Bashir���s trademark moves.)��While this spectacle took place,��Bashir���s��security forces were teargassing peaceful anti-government protestors. The hypocrisy of this��also��motivated many responses from artists.

Although portraying the President is punishable by law, fear of doing so has dramatically decreased in light of more and more people joining the protests. Social media platforms are full of caricatures of Bashir which depict the oppressive system he and his government have installed for the past��three��decades.

Street art is another vehicle of resistance in Sudan���s protest history; a medium of voicing political opinion which has spread all over urban centers. Simple slogans reiterate the tenets of the movement while portraits of the martyrs enhance the community���s unity. Under the cover of night, activists spray their messages on billboards and walls all over Khartoum, while protest posters appear at traffic lights. The non-violent resistance movement��Girifna��is well known for its use of street art in highlighting their protest.

While police and security forces shoot rubber bullets, gas canisters and live ammunition at protestors, some collect these items. On one hand, this can be done to prove the violent backlash they face���on the other, it can be used to contest the violence through artistic means. Tear gas canisters are laid down on the ground forming words such as��the��names of neighborhoods, or protest chants like����������_������(just fall). Bullets have also been used to create��jewelry. These appropriations of ammunition contest the power of the “enemy” and send powerful messages of resistance and resilience.

The��role of women��has been vital in the current uprising. One example is a new practice undertaken by women, in which they write anti-government slogans on their hands and feet with henna���which is traditionally used to decorate women and show their marital status. Using henna as a form of protest is an act of dedication to the cause, and puts them at great risk in public spaces where their political commentary becomes publicly visible. Similarly, male artists have been appropriating the henna tradition, using permanent markers to inscribe chants, flags and faces onto their skin.

Protest art��in Sudan��has become a self-perpetuating movement. The artistic expressions, deeply rooted in the moment and space they originate in, represent the creativity of the��Sudanese people to develop new tools for protest, as well creating a dialogue that is stronger and longer-lasting than the tyranny of the ruling elite. The artworks provoke the government to respond with acts of cruelty, but��brutality��only increases��the resolve of the artists.

This piece was���originally written for���shado,���an online and print publication which promotes the engagement between arts, activism and academia to amplify the voices of those at the frontline of social, political and cultural change.���Instagram: @shado.mag

March 21, 2019

Reanimating mobile cinema

An audience gathers for the Sunshine Cinema special screening of the Waves for Water documentary at Blue Bird Garage in Muizenberg, Cape Town, South Africa, on February 19th 2017. Image credit Sunshine Cinema.

Cinema���s mobility���the medium���s capacity to move beyond the confines of theatrical exhibition spaces���has��long been exploited on the African continent, and to a diversity of ends.��Even south of the Sahara, commercial theatrical exhibition���whether in roofed establishments or open-air venues���has coexisted��with noncommercial, nontheatrical iterations of cinema��since at least��the 1930s.��Colonial rule facilitated the rise of mobile cinema units consisting of vans, 16mm projectors, reels of 16mm film, collapsible screens, and���perhaps most significantly for the spread of market ideology���interpreters or��comperes��whose task was��to ���explain��� the meanings (including the capitalist encodings) of imported films.

In the aftermath of��independence, colonial cinema vans were repurposed for neocolonial enterprise���heartily adopted by multinational giants,��including pharmaceutical companies, for the exhibition of industrial films and the associated selling of drugs and other products.�����Mobile vans reach Africans,�����announced��the American��trade paper��Business Screen��in 1961.�����The showing of sponsored advertising films and public-interest short subjects is a familiar practice throughout these lands.�����Indeed, during and after��colonial��rule,��mobile cinema units were exploited by numerous commercial organizations,��including Unilever and Procter & Gamble, in order to move various products.��By the 1960s, numerous pharmaceutical companies had co-opted these immensely popular cinema vans in order to advertise and sell their products, employing hawkers��to describe these goods in detail (and, of course, to identify their prices for cinema audiences).

Introduced by colonial governments committed to cultivating respect for free-market enterprise (however politically and racially constrained), mobile cinema units were later employed to help expand practices of consumption across the continent, thus confirming and extending their original function as instruments of the capitalist world-system. Brought to village squares and athletic fields, cinema vans, with their prototypical combination of screen entertainment (such as gangster films and romantic melodramas) and multiple modes of advertising (short industrial and promotional films accompanying the feature-length attractions, marketing slogans discernable on signage, and ���interpreters��� trumpeting the benefits of particular consumer items), anticipated a central aspect of today���s multiplexes, where African audiences are assailed by commercials for Coca-Cola��as they wait for the latest superhero film to start.

Mobile cinema units���prized pedagogic mechanisms of colonial governments, later��embraced��by indigenous elites and multinational corporations���required little more than automobiles, projectors, and folding screens. They routinely attracted large and enthusiastic audiences, even when exhibiting dry ���developmentalist��� documentaries. The immense popularity of these ���traveling vans��� is captured in a 1940 article��in��Documentary News Letter: ���When a van arrives at a village the show is announced through the loudspeaker, and (in Nigeria at least) an audience of anything from 2,000 to��15,000 can be rapidly collected. Before the film is shown, its story is first explained in simple terms through the microphone. After it is over, a short talk follows, punching home the main message of the film.���

It is against this backdrop that��Sunshine Cinema, a solar-powered mobile-cinema network, has emerged.��Since 2013, it has screened to over 8,000 audience members across southern Africa, offering��film showings��and workshops devoted to community building and the pursuit of social justice. Sunshine Cinema���s reliance on solar power and its emphasis on environmental challenges should be of particular interest to anyone examining questions of power generation on the African continent in an age of accelerated climate change. Indeed, a commitment to solar power���what Sunshine Cinema both promotes and embodies���is��increasing throughout the continent.��Nigeria, for example,��invested $20 billion in solar projects in��2017 and is��currently��building a $5.8 billion hydropower plant to bring electricity to a rapidly growing population (which current estimates put at 198 million people, and which��is expected to��more than double��by 2050). For some national economies, shifting to renewables is a means of getting more media to more people���a��goal that resonates with some of the objectives of Sunshine Cinema.

In the following interview,��Sydelle��Willow Smith, the director of Sunshine Cinema, reflects on the network���s origins, development, and possible futures.

How the poor can fight back against the banks

Stone Town, Dar es Salaam. Image credit Andrew Moore via Flickr (CC).

I live in��Manzese,��on��Mvuleni��Street. [Manzese��is a working-class area in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania���s commercial capital ��� Editor]. I own a small business. We, small business owners, find ourselves taking out loans because of the difficult living conditions we face; so, we go for loans to get capital. Because the commercial banks refuse to lend to us as we lack collateral, we have invented new strategies to lend amongst ourselves.

Upatu

In the past,��upatu��(a collective savings and credit scheme, or ���money-go-round���) was very well-known, and it seemed to help many poor people. The way��upatu��worked was like this: you were many people, each one of you contributed a certain amount of money each day, and then after several days, one person would withdraw money. Like let���s say you are 20 people, each one of you contributes Sh2,000 ($0.86), so each day you have Sh40,000 ($17). After five days, you give away the money to one of you, and then you keep rotating until everyone has benefited.

The person managing the��upatu, the treasurer, is known as the��kijumbe��(literally, the ���broker��� but effectively a treasurer). Initially, the treasurer did her work voluntarily, so she took no pay. But later many treasurers turned��upatu��into a business. That same treasurer started to claim an allowance. When collecting money each day, she charged a fee.

The whole scheme was not secure at all. There were many cases of treasurers failing to safeguard the money, or those who got money early in the rotation then ran away without contributing their share.�� A treasurer could get money and use it for her businesses or to pay a loan. Also, the��upatu��scheme was dominated by the treasurer who was the only person who knew everyone while you, the participants, did not know each other. After some time, this scheme lost prominence as many people stopped taking part.

Microfinance institutions

Another way to lend to poor people is through microfinance institutions, which are now widespread. These institutions lend to one person, but she must be part of a group. So, the guarantor of the loan is the group.

A small business owner is given a loan, and then she is told to return a small amount each week. But that person receiving the loan is not told how much interest will be charged. She will just be relieved to see that the loan repayment each week is not very big. Even so, if you calculate, you��realise��that a person may take out a loan of Sh500,000, but by the time she finishes paying it all back, she will have paid Sh750,000. In other words, she is charged a 50 percent interest rate for the few months when she had that loan. A big part of the profit that small business owner makes, then ends up being taken by the microfinance institution.

Because poor people access credit in groups, if one person misses her loan repayment, then the whole group is told to pay for her.�� Often, the group members who���ve come to pay their share are literally locked inside the offices of the microfinance institution until they find a way to cover for their absent colleague.

A mountain of debt

If a debtor completely fails to replay her loan, the interest will continue to increase beyond what was left to repay of the loan. You find yourself with a mountain of debt, even though the money you took was little. Also, there are microfinance institutions here in the streets that subtract a lot of money from your loan all while still charging high interest rates. For instance, there is one institution that, if you want a loan, you will pay Sh20,000 for the application form. You will then be charged for the cost of sending an officer to inspect your things as well as for the loan insurance. At the end of the day, if you took out a loan of Sh400,000, they subtract like Sh80,000, and you are left with Sh320,000. Then they charge you a high interest rate, so you end up paying a lot of money.

If you fail to pay back that loan, they announce an auction to liquidate your assets. Officers from the microfinance institution, rallying your fellow group members to help, they come to take everything from your house.

There is one sister who had her belongings in her home, but when she failed to pay back her loan, they came and took everything, even the cutlery. They sold it all off for a very low price just to get their money back. This means if you go to borrow, there is nothing you get out of it. You end up losing everything you had, from your small business to everything in your home. You are left without a thing; you have to start from scratch.

This means, if you borrow money, make sure you don���t have any problems. You shouldn���t fall sick because if you do get sick, you go to hospital, and then you end up using your loan money to pay for your treatment. Or if your child is going back to school, where will you get the money for school fees? Will you just stare at that child? You���ll need to take money from the loan to pay those fees. If you get any problem, you will have to use that loan money. Then the interest they charge is not at all in line with the profit you get from your small business. You end up working to profit the microfinance institutions.

For those who are married, sometimes the husband can be stubborn and refuses to let your things be taken. He will say that those things in the home are his as the husband, so if they want their payment, fine, let them take ���their person��� (the wife) who borrowed the money. This does not help; instead, your fellow group members are used to pressure you, to humiliate you. They will harass you using whatever means they can so that you pay back that loan.

In our area, many people have run away from their families to escape their debts. A person may disappear for even a whole year. Meanwhile, her things are sold off. Then they force her group members to pay back any remaining debts. The day the runaway returns, she���s caught by her group members and taken to the police. If she is granted bail, her family pays money. Now she has become a source of capital to the police. After being granted bail, she will sign a police statement so that she repays that loan. As the date for repayment nears, she will need to borrow again. But no lender will agree to give her another loan because she has nothing ��� she doesn���t have a business or her own personal belongings. In this case, she���ll have to borrow from private individuals at an even higher interest rate, and so the problems start again. I mean, it���s one problem after another.

Exploitative savings and credit groups

The system of savings and credit groups was, at the start, an exploitative one, dominated by the rich woman who founded the groups.

[In this section,��Shomary��discusses a particular scheme, the Village Community Banks (VICOBA). The VICOBA were established by a prominent woman, who was at the time an MP (referred to here as the ���rich woman���). The VICOBA structure is as follows. You have savings and credits associations that function as a primary unit, and then there is an apex organization that brings together all the primary groups. This structure resembles the standard, unitary structure of Tanzania���s cooperatives.��Shomary��observes that the apex organization was not accountable to its constituent primary groups; it was simply a structure created to extract money from poor women. That is why her primary group ultimately decided to withdrew from the VICOBA��structure.���Editor]

If you start a group, to register it, you must pay the registration fees, which were Sh450,000. Our group, when it was registered, it had to pay an additional Sh300,000 to access more lending opportunities. We paid that money until we had paid Sh6m, but we did not get any loan. We started going to demand our money at the headquarters. We went��round��in circles, wasting our time, and after all that frustration, we only got half of our money back. When we got to the headquarters, we found mainly groups had come to complain, and they too were demanding their money.

Also, our group had to pay Sh30,000 at the end of every month as the monthly fee. In a year, we paid Sh360,000. We were told that money would help us get supplies, like notebooks, and cover the cost of a teacher and a group coordinator. But for a whole year, we didn���t get a teacher or coordinator. The only instruction we got came from the sponsors, especially Coca Cola, whose aim was to convince small vender to sell its sodas in their area.

The fees kept going up from Sh30,000 to Sh60,000 per month. When it reached that level, we wrote a letter withdrawing our group from this savings and credit system and demanding our money.

In that system, each group member must open a bank account, and the group itself also must have its own account. The bank where we opened our account had a contract with the company that ���owned��� all the savings groups, and so it withdrew our money to send it to the ���apex.��� All the money we contribute collectively to lend to each other we had to take first to the bank, then the bank transferred the money to the account of the individual group member taking a loan. Here there are the costs of running an account. Even if you go to check your balance, you pay a fee.

Another exploitative venture was the government���s effort to encourage small business owners to form groups and get loans from the government. There again each group had to open an account, and each group member also had to have her private account. The group account had to have a balance of Sh20,000, and each member���s account needed a minimum of Sh10,000.

Here in��Manzese, there are like 50 groups, and each group has 30 members. Do the math: in��Manzese��ward alone, that bank collected Sh15m. In each district, the bank can��mobilise��30,000 group members to open accounts and get government loans. Because there was a big��mobilisation, and because it was done by government officials, I am certain that the bank got no less than 30,000 new customers in each district across the whole country. Take the 160 districts, each adding Sh300m, you get Sh48b.

Many of us who were encouraged to open accounts didn���t get loans. So, it���s really us who gave a loan to the banks. My group contributed Sh300,000 to the bank. Through all our groups, we contributed more than Sh48b. Here in Tanzania, it���s us the poor who loan to the banks.

The third exploitative scheme involves identity cards for��wamachinga��(small business owners, vendors). I know that when President [John]��Magufuli��introduced these identity cards, he had good intentions, and almost every day he tells us that he looks out for the needs of the poor. But each identity card is Sh20,000 per year. Each region received 25,000 cards. In a single region, the government collects Sh5bn. If you add up for Tanzania���s 26 regions, excluding Zanzibar, you get Sh130bn. And already Regional Commissioners have been told to take more identity cards where they have already finished distributing the first lot. I am sure there are very many of us small business owners. When we pay this money for the identity cards, it doesn���t mean that now we don���t pay taxes where we do our business, including for our market stalls. This Sh20,000 is just another burden for us. The question I ask myself, this money, will it be invested in social services so that if I go to hospital for a surgery, I won���t be charged? If not, then where is it going?

A Democratic Alternative ��� Savings and Loans Cooperatives

There is now a more egalitarian system of savings and credit groups.

The aim is to build the capacity of lower-class people after many of them were hurt by the system that only benefits financial institutions. In this new system, we lend to each other, we set our own interest rates, we share out the profit, and we don���t bring our money to any bank.

We lend to each other for 36 weeks, and after that, we start to return our loans. When we get to the 48th week, each member gets their savings back and then we divide amongst ourselves the left-over profit from interest collected on loans.

In managing our groups, we discuss everything collectively and openly. If someone wants a loan, we discuss with her, and everyone knows the amount she contributed. Through the discussion, she can explain her problems, and her fellow group members can discuss the way to help her through a social fund, a children���s fund or a loan. [Shomary��here refers to the three funds to which group members contribute: the social fund, the children fund, and the general��contributions.���Editor].�� Through these groups, we are inspired to love each other, to respect each other and to help each other.

There is also transparency in the collection and lending of money. Each time we meet, we count the money together, and we record the results together. As such, each group member knows how much money was contributed and where it went.

If a group member could not pay back a debt, she stays in the group. Even if she is afraid, we encourage her to stay as a group member, and we set a procedure for her to gradually finish paying back her debt.

At the end of a savings cycle, at the end of the year, the social fund and children���s fund are divided up equally. But with the savings, each person gets back what she put in to begin with. The profit is divided according to the percentage of savings each group member contributed.

The small business owners��� liberation

From my perspective, I see these groups as a liberation for small business owners. For instance, if I want to get a bank loan, I need guarantors. Me, a poor woman, who is going to agree to be my guarantor? Also, bank interest rates are high, and that interest goes into the pockets of only a few people. But with our groups, there are no complicated lending conditions. If you need a loan, you will get it there and then, and the profit that comes from this scheme isn���t for someone else; it���s our very own.�� With the banking system, if someone is late with their loan repayments, she has to pay additional interest, and if she fails to pay her loan, she is bankrupted. There is no one who listens to the borrower���s troubles; they just want her money. With our groups, we listen to the problems of each one of us, and we find a way to help. We don���t add on extra interest, nor do we sell off her property.

If we plan well, we can use this system to open our own bank���the Poor People���s Bank. Our bank will not have extra charges and costs to drive people to bankruptcy, and with our deposits, we can make big investments that benefit the majority. There is a large network of these groups here in the street, and the groups can use their experience to pool their resources at the ward-level, and then continue to higher levels.

These groups can also build the collective strength to empower the poor to fight for their rights. We need to use these groups to encourage discussion about the reality of our daily lives. For instance, when we go to hospital, what happens? Is it our responsibility to pay for expensive health care? If I go to a government hospital, I will be asked to pay Sh2,000 for a registration card. If I get a test, like a simple blood test, it���s more than Sh10,000. And I haven���t even bought any medicine. Why is it that we hear children���s medicines are free, and then if you take your own little girl to hospital, you get the prescription and then are told to go buy the medicine at the pharmacy? Now aren���t you paying? Is this your responsibility? So, we can use these groups to question these things and to demand our rights.

Also, we can use these groups to advise our President, who presents himself as a champion of the poor. It is good to hear about and find solutions to each person���s problems. For instance, one mother whose land was confiscated had it returned to her, which helped her a great deal. But each time he helps someone, he should know that there are a thousand with that same problem. So, what we can advise the President is that he implement policies that remove the troubles confronting the majority. If he buys the farmer���s crops, that is a good thing. But if you have yet to remove charges for healthcare, then the farmer���s money will end up with the hospital. Or it will end up paying a bank loan. That person, will she benefit really?

This article���forms part of an initiative with���Sauti��ya��Ujamaa���(Voice of Socialism) to amplify grassroots voices���on Africa is a Country. The original post was dictated by the author in Swahili, transcribed by���Sabatho���Nyamsenda���and published in the bi-weekly Tanzanian newspaper,���Raia��Mwema��(Good Citizen) and then on��the Sauti ya Ujamaa blog.

March 20, 2019

Thinking with Africa, making the world

Saving Mali's manuscripts. Image credit Marco Dormino via UN Photo Flickr (CC).

At their origin, African studies���ethnology and anthropology in particular���were��colonial exercises��intended to think��about��Africa and to say what it was; to define it in order to better dominate it, and to be able to adjust colonial techniques of domination and exploitation. It was in no way a matter of thinking��with��Africa. Contrary to this perspective, in a decolonial approach, we would like to think with Africa as world-making; to think with Africa and make world, make worlds, in order to make the world. But what should be understood by world-making?

World-making is building, producing the world. It’s building the link from the in-common to the present time, in order to re-member ourselves. It is building a link between generations, with the past and with the future. But it is also to think of humanity in taking into account its link, its relationship to life and to the world in which we live, that is to say to the planet that we occupy. To make world is therefore also to think the cosmos.

A lot of formerly colonizing nations such as France maintain a colonial relation towards its Afro-descendant population, and do not manage to treat it fairly and to fully recognize it as part of its history and identity. How can afro-descendants realize themselves when they are nowhere to be found in the collective memory? When their past has been erased, and they are considered alien to their own national community even as they help to form it? When the link to their own history was broken the moment that, for example, their ancestors were ripped from their native land to be deported to another continent? How to deal with this experience of a double-absent memory (the absent memory of their heritage and the absence of afro-descendant memory within the national narrative)? And how to handle this experience of transgenerational memory that can transmit an experience of submission, self-hatred, denial, or resilience and resistance? In the same society, transgenerational memory transmits a different kind of lived experience to another section of the population; one of dominance, arrogance, racism, violence, and a feeling of superiority. For white citizens of formerly colonizing countries, there is the question of their responsibility in the perpetuation of a singular system of domination.

This past that we have in common compels us to work towards an understanding of what makes a community and its members, whom we have to connect. How to integrate those who have been excluded into the founding narrative of our society, without the destructive violence of assimilation that asks them to destroy their own memory, and with it their history, their culture and their language? We have to think about what memory can and should be in and for a community and individuals in this community.

In the context of a partial remembrance, to make memory is to undertake the task of mourning���whose therapeutic dimension is essential for re-possession of the self���especially by reconnecting with what has been unjustly depreciated, devalued and expunged. Heritage must therefore be subject to inventory. To remember is to give value to one’s story and to master the discourse that surrounds you. This is part of the process of identity. Memory is one of the sites in which I am able to choose my own trajectory, one that bears meaning for me and, from a collective point of view, for my people.

There is an urgent need to learn to live together. Thus, let us be reminded that the social cogito that is��Ubuntu��teaches us that community is not a sum of scattered individuals; it is the group, through the links that it creates and nourishes, that nurtures the power to act. This praxis rests on an in-common that must be built. This implies developing an ethics of participation and solidarity.��Ubuntu, which could be translated as “I am because we are,”��invites us to privilege the common interest over that of our individuality in all circumstances, and to strive always to identify with others, even with their feelings of hostility, in order to regulate one’s own life. This social cogito suggests respect for another’s humanity, insofar as it poses the irreducible value of human life. And it infers an ethics that rests on the pre-eminence of reparation and on understanding over punishment. Which, very concretely, supposes the continuous search for conciliation and the “refusal of revenge” in the management of conflict.

We find this idea in different forms of traditional African justice such as the��gacaca��in Rwanda. In the aftermath of the genocide, discussion played a central role. It was a matter of recreating foundations for a peaceful society, without erasing the crimes that had been committed from memory, or abandoning the cause for truth; and rather by developing the conditions for an active citizenship unburdened, as far as possible, of vengeful feelings; and which is necessary for the construction of a true democracy.

This is what the Cameroonian philosopher Jean-Godefroy��Bidima��proposes in his essay, “La��Palabre: the legal authority of speech,” in which he explains that, in��palabre, the rights of the community do not supplant those of the individual, even if justice bears a cathartic function that comprises the healing of the collective��and��the individual. It seeks to rehabilitate the other, be they the victim or the guilty party, and to recognize them, as such, as a full member of society.

In this perspective, world-making is to build together a memory of the in-common which supplements our own – and does not replace it. Memories are not exclusive: one can add to one’s own memory that of the in-common, which should surely lead us to forge a memory that is reconciliatory and peaceful; the only thing capable of permitting each one of us to deploy our full potentiality and to realize what we are. This does not mean always being in agreement with others or seeking consensus at all costs. But to think about how we can use tension in order to create a positive, and not necessarily destructive, force. To see how, in certain situations, dissensus can be beneficial, in particular for avoiding any move that would tend towards transforming the “different” into the “same.” We must also ask ourselves how memory can bring together the various and the multiple without diluting them in a unity understood as one. How can that which makes dissensus contribute to the construction of the in-common?

Therefore, a world-memory would be a memory that allows us “re-member”. This task of “re-membering” is a work of both remembrance and consolidation. To build community is to��re-member, or to re-group, ourselves; to gather scattered members and to build a body around the values, goods, and history that we have chosen to share.

World-making is above all making a place livable, habitable. But what makes our world so, in the strictest sense, is not, contrary to what we would like to think, so much man and his activities as plants and the process of photosynthesis that transforms solar energy into living matter (Emanuele Coccia). We do not belong just to humanity, but to life. We do not inhabit the Earth so much as the atmosphere, which is this cosmic flow that we produce in interaction with plants.

We have forgotten our planetary condition, that we are inscribed into a cosmos and that the Earth could not exist outside of it. A process of withdrawal from the cosmos, from a philosophical point of view, was developed in the West during the period of so-called Modernity. But astrophysicists have proven to us that we are all stardust, that we are the children of stars that have exploded and during this process, produced the chemical elements that we are made up of and which also make up our world. We have to understand that all world-memory is a cosmic one. This is not a metaphor. We all share the same genealogy. Everything that lives on the Earth is astral in nature. There is material and ontological continuity between the Earth and the rest of the Universe. This planet that is our home is a celestial body. Let us move out of the night in which we are enclosed and think about light, the sun, the moon, the stars. There is no autonomous Earth.

Our cosmic reality calls for an understanding that we can only make world by conceiving of human community in its intimate link to the rest of the world, animal, vegetal, mineral, with the invisible, our ancestors and those to come, with our universe as well as the other universes, the multiverses of astrophysicists. World-making means understanding that human rights cannot be separated from the right to a healthy environment, and therefore from the rights of nature, nor from engaging in transformations of our social and political organizations in order to broaden the beneficiaries of rights to include Nature. This has already happened in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and New Zealand, as well as thirty-something cities in the USA; we must also broaden our conception of democracy to include future generations, as well as our forebears.

In this way, the West has much to learn from African civilizations that have fostered a bio-centric philosophical vision, judging it better to under-use the nutritional potential of nature because the planet is for all living things. In this way, it would be invited to go beyond the anthropocentrism of its humanism. In the second half of the 20th��century, African philosophy built and defined itself in opposition to African cosmologies, to animism, and yet, it could prove extremely fertile to explore these traditional philosophies in that, according to��Felwine��Sarr��in��Afrotopia,

the conception of the Universe that is visible in a wide variety of African knowledge and practices is that of a cosmos thought of as a great living thing. It is a whole of which Man is an emanation, one living being amongst others. […] Man is considered as a symbolic operator linking heaven and Earth. […] the ritual of repairing the Earth constitutes one of the most significant symbolic acts in a��realisation��of this responsibility (115).

They could certainly provide us with a rich source of material that we need to offer to post-humanist thought which, and this is not a paradox, would allow us to accomplish our��humanity in that becoming human or being more human would bring us back to helping life, and every life force, grow. To succeed in making a world is to achieve one���s humanization, not only for humanity, but for everything living, and to inscribe oneself into a cosmology of emergence. This��vitalist��ontology insists on an ethics of action. We must act according to everything that reinforces vital force. Evil is the lessening of life force. It is thus a question of privileging the relation which allows to be related without being tied together, which emancipates and does not stifle.

March 19, 2019

Diagnosing neopatrimonialism

Nigeria���s President, Muhammadu Buhari on a visit to Benin in October 2018. Image via office of the President of Benin via Flickr (CC).

Thandika Mkandawire��is currently Chair and Professor of African Development at the London School of Economics. He was formerly Director of the��United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, and Director of the��Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa��(CODESRIA). In 2015, he published an influential critique of neopatrimonialism, “Neopatrimonialism and the Political Economy of Economic Performance in Africa: Critical Reflections.”

[It���s been very difficult to pin down what political scientists, who favour the term, mean when they talk about patrimonialism or neopatrimonialism. As the political scientist Anne Pitcher, anthropologist��Mary Moran and political scientist Michael Johnston illustrate in��a 2009 article, it is difficult to pin down what is meant by the term.��They summarize the political science view as ������ to denote systems in which political relationships are mediated through, and maintained by, personal connections between leaders and subjects, or patrons and clients.�������� The Editor, AIAC]

Mkandawire���s��empirical analysis demonstrates that neopatrimonialism can neither explain heterogeneity in political arrangements nor predict variability in economic outcomes. He argues that its dominance in scholarly and popular discourses of the continent derives from its appeal to crude ethnographic stereotypes. Yet such stereotypes are at odds with the idea that African citizens can be trusted to vote intelligently. As a result, the��neopatrimonial��school tends to seek political arrangements that can circumnavigate democratic politics, particularly in the form of bureaucratic authoritarianism or external agents of restraint. Against this, Mkandawire insists on an approach that recognizes the importance of democratic politics, and the critical role that ideas, interests and structures play in shaping African societies.��The full interview can be read��here. Below is an excerpt of the��interview��which I conducted for the Journal for Contemporary African Studies.

Nimi Hoffmann

What explains the rise of neopatrimonialism as a framework for understanding African societies?

Thandika Mkandawire

The Dependence School was firmly focused on external drivers and with��Fanonian��concerns over the mental state of ruling elites (���colonial mentality���). With the��crisis starting in the mid-1970s and subsequently worsened by the pro-cyclical policies of neo-liberalism (introducing austerity measures in economies in recession), it became common to focus on the internal causes of the demise of African economies. Two internalist explanations of the public choice approach focused on interests and rent-seeking. The ���universalism��� of this approach built on rational choice and methodological individualism, and had little room for culture. Africa���s economic policies were attributed to capture of the state by organised special interests seeking policies that would assure them rents. Except that there were no such organised interests in Africa. The approach also suffered from a crude materialism and the non sequitur that if groups of people benefited from a particular��policy��they must have organised around themselves for that policy and its eventual perpetuation.

Later, when governance was identified as Africa���s main problem, neopatrimonialism became dominant. Here we entered the realm of analysis by invective. Both these schools tended to rule out any possibility of development or states that would pursue development as a national project. These arguments prompted me to��write the paper��on the Developmental States in Africa which was first presented at a CODESRIA General Assembly.

Neopatrimonialism has been with us for a long time. In the 1960s when Africa was doing well economically ��� 5.7% growth rates ��� and when credible nation-building policies were being pursued, little was said about the cultural barriers to development.�������Neopatrimonialism may be pointing to social practices and social hierarchies in Africa. But it has little predictive value. As a paradigm, neopatrimonialism has had to deal with a wide range of discomfiting facts but it somehow soldiers on. One feature of paradigms is precisely their capacity to fend off discomfiting evidence through a wide range of ���paradigm maintenance��� stratagems. Increasingly it is being sustained by a wall of adjectives to account for nonpredatory behaviour in some countries. For example, we now have ���developmental neopatrimonialism��� to account for periods of high growth in a number of African countries. We should not forget that academics invest huge amounts of intellectual capital in sustaining a particular paradigm and they are not going to go away all that easily.

Nimi Hoffmann

What explains the appeal of anti-democratic and culturalist explanations to those of us on the continent?

Thandika Mkandawire

One explanation is the failure of many new democracies to deliver on the substantive demands of voters. New democracies in developing countries emerged under the dark cloud of neoliberalism. Democracy was largely reduced to formal structures of elections and voting and was to eschew any messing up with the macroeconomy. Democracies were disempowered by removing a whole range of key functions from the oversight of representative bodies. Thus central banks were made independent but only with respect to national institutions. They became what I called ���choiceless democracies.���

And today some of the countries identified as star performances are not exactly what one might take as democracies. The great intellectual challenge for Africa is how to create democratic developmental states that can address the material needs of citizens in ways that are socially inclusive.

The other purpose has been the delegitimation of local elites. If the local elites are hopelessly mired in neopatrimonial relations, then ���external agents of control��� such as the IMF, foreign experts or foreign dominated NGOs, present a way out.

Nimi Hoffmann

What would you replace neopatrimonialism with?

Thandika Mkandawire

With nothing as grandiose. I would insist that African scholars engage with intellectual traditions but also insist that the African experience is understood and taken seriously and that many claims by or for the universalism of their own experience are fraudulent claims.

What is the Dangbe word for chameleon?

Accra, Ghana 2006. Image credit Jonathan Ernst via World Bank Flickr (CC).

A few weeks ago,��I asked my mother for the��Dangbe��language translation��of��the English word�����chameleon.�����She couldn���t remember it. She insisted that she knew it but hadn���t used it in a long time,��deferring rather to the English word. So, my mother called her sister who unsurprisingly didn���t remember either. They called another aunt who,��they assured me,��spoke proper��Dangbe. Strangely, she used the Twi equivalent of�������bosomaketew,�����convinced that was the��Dangbe��word.��The search continued.��Friends were called, pocket dictionaries were consulted and memories were racked�����till the word�����Akpasi�����was found.��The entire exchange was hilarious but filled me with a profound sadness. Although my family speaks��Dangbe, I was raised with the Ga language because I grew up in towns where Ga is the native language.��Dangbe��is increasingly becoming endangered, losing��ground as a first language and I am an example of this.

In Ghana,��speaking a local language in school is subject to punishment��as in��other African countries. This is a bizarre attitude seeing as Ghanaian languages are examinable subjects in the school curriculum. The law requires that��a local language is used as the language of instruction��from kindergarten to upper primary level. From then on, English replaces these languages as the language of instruction.��Given��the favored outlook towards English,��this law is often non-enforced,��with English being used throughout��a child���s early schooling.��We could argue about the effectiveness and usefulness of this law. In a��globalized��era,��in which��competency in English is highly valued,��we could argue that��English as a language of instruction from the beginning of formal education is useful.

I���m more interested in the��impression that such a law gives about the relationship between English and the other languages. It assumes that local languages exist merely as launching pads into a higher form of education in English. After the fourth grade, they are reduced to single non-compulsory subjects, pushed aside for the favored English. Coupled with attitudes of derision and negativity, local languages are then increasingly seen as lesser.��Native fluency��is on the��decline in most mother tongues.��What is occurring in its place is switching and mixing with English��to supplement vocabulary.��English becomes the default base for discussing serious and complex issues with insertions from other languages. English vocabulary is�����localized�����and the indigenous equivalents of these words steadily decline in use.