Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 224

April 3, 2019

Algeria, Sudan, and the Arab Spring

Image by Omar Malo, via Flickr CC.

In the early, heady days of 2011, pundits and policy makers alike were caught out as the uprising that toppled two pro-Western regimes spread to adversarial regimes in Libya and Syria. Counter-revolutionary actors quickly took advantage of openings in the latter two countries to get ahead of events that were seriously threatening the international order in the region.

That order, it is often forgotten, was characterized by decades of nearly an unrivaled American hegemony. And it had never seemed more entrenched and ossified than it was in December 2010, before thousands of people rose to challenge it.

The hope and optimism that many on the left felt in those early days has since been eroded by the victories of a coordinated, repressive, and blood-soaked counter-revolutionary wave over the past few years. The Syrian regime is inching closer to achieving a full military victory, el-Sisi���s Egypt has become more repressive than Mubarak���s, and the Gulf states, led by Saudi Arabia, are openly acknowledging their alliance with Israel, something that��would have been impossible before the uprising was contained.

These setbacks led to a renewed pessimism and revisionism about the events of the Arab Spring, on both the left and right.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the Western discourse around the Syrian civil war, as elements from both the left and the right are increasingly expressing support for Bashar al-Assad���s regime.

Pro-regime arguments collapse the politics of the Syrian war, and indeed, the entire region into a geopolitical binary. Actors are judged worthy of support by their perceived alliance or hostility to Western interests. Elaborate facades of analysis can be constructed upon this foundation, but they only serve to liquidate the agency of the mass of people in question and reduce whole societies to monolithic entities defined entirely by their perceived position vis-a-vis the West.

Implicit in this argument are deeply Orientalist assumptions about Arabs and Muslims. The prospect of change in Arab and Muslim societies raises the specter of chaos; the ���inevitable result of the irruption onto the scene of a culturally and politically backward people unable to understand any language other than a quasi-atavistic obscurantism,��� in the words of the late Samir Amin.

The right has never hidden its agenda for the region or its preference for authoritarian governments. It is not difficult to critique the arguments put forward by columnists that attribute the problems the region faces to ���the disease of the Arab mind��� which needs an ���iron fist��� to be kept in line.

On the left however, the impulse to criticize Western foreign policies has led some down strange analytical corridors, where they end up internalizing and inverting the very discourses they seek to criticize. The struggle for human emancipation and all its constituent parts and expressions���rights, democracy, dignity, security���serve as nothing more than rhetorical flourishes, to be exaggerated or ignored depending on whether the regime or movement in question is perceived to be in support or in opposition to a Western ally.

Those on the right that buffoonishly justify support for the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman find their discursive mirror image in those on the left that support Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

From either end of the political spectrum, these arguments begin to fray when the uprisings are viewed from a proper, regional perspective. Nearly every regime in the entire region���from those that are hopelessly reliant on Western countries like Jordan, to those that frequently fall into confrontations with them, like Libya or Syria���experienced remarkably similar protest movements, animated by similar economic and political grievances. As Gilbert Achcar argued in his 2013 book, The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising, the levels of oppression and type of regime may vary, but these regimes shares similar economic and political characteristics, which constitute the ���peculiar modalities of capitalism in the Arab Region.���

The fact that the Arabic chant ���ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam,��� was taken up by the protestors everywhere they took to the streets, from Tunisia in December 2010 to Sudan and Algeria in 2019, is a testament to this inter-connectedness, and an expression of solidarity across borders that recognizes a mutual struggle against similar oppressors.

The central demands of the mass of people across the region are the same: the fall of the regime and the unequal social order that it perpetuates.

So how does one end up developing different positions in relation to the different uprisings or the regimes they challenged? How does one support the uprising against Ben Ali or Mubarak but oppose the uprising against Gaddafi, or Assad?

The key to sustaining these arguments is to cleave the developments in question from their regional context. This is the only way to give coherence to a position that prioritizes the very narrow interests of one regime over the interests of the mass of people.

That is the lens through which policy makers in Western capitals and their counterparts in the mainstream press view these events. Inverting that lens is not a sufficient or critical response.

It is easy to be reflexively pessimistic and argue that the alternative to the status quo could be worse, but events in Algeria and Sudan show that the mass of people are still a force to be reckoned with and that the region is still far away from a return to authoritarian stagnation.

April 2, 2019

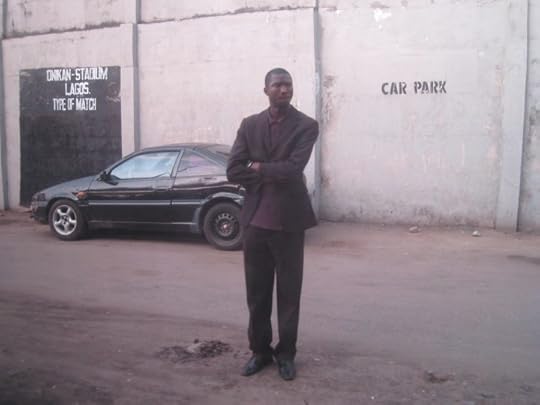

Sex, lies and Lagos

Image credit Nick M via Flickr (CC).

In his first novel,��Easy Motion Tourist, the Nigerian writer��Leye��Adenle��introduced us to��Amaka, a lawyer turned protector of commercial sex workers.��Amaka��is the only child of Ambassador��Mbadiwe, one of the old-moneys of Lagos���old enough to own property in old��Ikoyi. Through the eyes of Guy Collins, a British journalist posted to Lagos to cover the upcoming Nigerian elections, the book explores the ritual killing or the trade in human body parts: the street gangs that kidnap and kill, and the Lagos big men who commission the street gangs. Guy,��Amaka, and Inspector Ibrahim, an officer in the Nigerian police force, unravel a web of killers that reach as high as the commissioner of police, and just as the commissioner is unmasked as the directing mind of the enterprise, the book ends.

In��Adenle���s��second novel,��When Trouble Sleeps, the story opens just a few days after book one ends. Guy Collins is back in London and��Amaka, just like��Adenle, is no longer interested in kill-for-money gangs. The task at hand is to uncover and take down a prostitution ring, which is disguised as an exclusive social club, by following the trail of a working girl, Florentine, who was beaten and left for dead by Chief��Ojo, a patron of the club. While��Amaka��hunts down Malik, the owner of the club, a political assassination sees Chief��Ojo��become the Lagos gubernatorial candidate of one of the two major political parties. So,��Amaka��must avoid death by Malik, who wants to put an end to her meddling in his business, as well as death by Chief��Ojo��and his political cohorts, who want to ensure that she does not stifle his long-held political dreams by revealing his varied criminal sexual dalliances.

In her quest against Malik and Chief��Ojo,��Amaka��co-opts everyone that can help���the Nigerian Police Force, the Navy, and even the opposition political party. She also has several unknown allies along the way,��double agents and turn-coats who reveal themselves just in time to salvage the story. It is hard to imagine the story sustaining itself, or��Amaka��remaining alive, without these��random��accomplices.

The cast of characters in��When Trouble Sleeps��are familiar, not��only��because they feature in��the first novel,��but also because they are recognizable as everyday��Lagosians.��Adenle��tames cynicism in his readers by infusing the story with characters that are distinctly Nigerian: from political godfathers to trigger-happy policemen.��He��successfully captures the grit of Lagos life:��from a��mob scene in��Oshodi��market��fueled by a��false allegation of theft��to��young people serving as political thugs to mete out violence against members and supporters of opposition parties.

Adenle��presents a thriller told through the eyes of��Lagosians��and thankfully removes the probing gaze of Guy Collins that trailed the first book.��When Trouble Sleeps��is written in��Adenle���s��distinct style:��short��vignettes��and detailed-oriented prose that renders every chapter or sub-chapter a movie scene,��so the��reader flips the pages with anticipation of how the cliff-hanger from the previous chapters will resolve.

Notwithstanding the��abundance of suspense, the resulting hunger isn���t always satiated. Some characters fall��in and��out��of the story��without any explanation, like the sister of��YellowMan, a political thug, who is kidnapped because of her brother���s activities but of whom we hear nothing��further. In another scene, Inspector Ibrahim is caught between two factions of his team, one loyal to him, the other lured by the promise of money from an apprehended suspect, both groups with their guns drawn and again, the book ends without any hint as to how the scene resolves. In yet another scene,��Amaka��is engaged to a Lagos gubernatorial candidate, ���Tiffany Diamond sparkling from her ring finger,��� and a few scenes later she is on a flight to London to meet Guy Collins.

The phrase ���The End��� that signs off the book does little to put to rest the many questions the book raises.

Perhaps��they will be answered��in the next��Amaka��thriller.

The new South African stoner comedy

Still from Matwetwe.

Ice Cube���s 1995 film, Friday, featuring two slacker friends in post-riot black Los Angeles (it launched the career of comedian Chris Tucker), launched a whole genre of stoner comedies. Three years later Dave��Chapelle��co-wrote the film, Half Baked, about three stoner friends trying to make a big weed score in New York City. Both films borrowed heavily from the films of the Latino comedy duo, Cheech and Chong, which made a series of stoner films from the late 1970s through the 1980s.�� Above all, both Friday (and its sequels) and Half Baked represented refreshing takes on Black American social life on film in the 1990s when films such as��Juice��(1992) and��Menace II Society��(1993), with their gritty and violent depictions of gang life in LA and New York, dominated.

The South African film, Matwetwe, falls squarely into the stoner comedy genre. Like Friday, Matwetwe��is a film of its time and its location. Just as��the former���s release coincided with a renaissance in LA hip hop and militant black identity politics,��Matwetwe��overlaps��with hip hop���s artistic and commercial success in South Africa��as well as��the rise of #FeesMustFall��and #RhodesMustFall��movements with their demands for black self-expression. While Hip hop celebrates ���hustling��� (entrepreneurship), the student movements of 2015 and 2016 emphasized doing things differently from previous generations. But, for all the comparisons and linkages to the American films, Matwetwe��is a very local film. Once you get pass the cheap stoner jokes, there���s much more to the story as a commentary on post-apartheid black life.

The title means ���wizard��� in Tswana. The story revolves around��Lefa��and��Papi, two childhood friends in��Atteridgeville, a working-class black township outside South Africa���s capital, Pretoria. Both��Lefa��and��Papi��have just completed their matric (senior year of high school) and chance on the idea to sell marijuana in the township.��Lefa��intends to��enroll��at a university by paying part of his fees with the proceeds from their business dealings, while��Papi��is just keen on ���hustling��� instead. The duo, whose respective families��� economic backgrounds are sharply contrasted, soon realize that they would not make the kind of substantial money that would change their lives by selling their merchandise in their township. It is here that��Papi��suggests that they target the white market in town where there is lots of money to be made. Through��Papi���s��cousin, who appears to come from an affluent family that stays in a historically white suburb in town, the duo clinches a substantial deal with a white man who gives payment money upfront, with an understanding that the merchandise would be delivered later. Sadly, the local thugs rob��Lefa��and��Papi��of all their marijuana before they could deliver the product to the buyer. This creates a major conflict for the duo and they quickly resign themselves to a doomed end. However,��Lefa��devices a clever plan that sees the duo, through an interesting twist, honor their deal with the buyer.

The film is directed and scripted by��Kagiso��Lediga, a regular on South Africa���s stand-up comedy circuit and also an accomplished screen actor.��The film was shot in three weeks.��Lediga��first wrote the script of Matwetwe��some twenty years ago while studying at the University of Cape Town, also a time when he was fascinated by marijuana. It just happened that in 2018, South Africa legalized the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes, after many decades of propaganda about marijuana���s supposed harm to humanity.

The film is generous with its humor, inspiring the kind of laughter that escapes one���s mouth as though it is a sneaky little fart that takes one by surprise, but whose release leaves behind a great sense of satisfaction. Boasting a rich and immersive cinematography,��Matwetwe���s��colors and textures are bold, strongly anchored. Through sweeping and excellent camera focal points, coupled with its distinctive Sepedi/Setswana dialect, Pretoria is represented delightfully with its cultural and structural dimensions and legacies.

Both��leads and��the��supporting cast give remarkable��performances. However, the��actor who plays��Papi,��Tebatso��Mashishi, stands out; impressing in the spoken elements of his character, but��also in the way he embodies the character:��in the way he walks for example, or pauses for a moment to think, and how he generally engages his fellow actors through his eyes and other body features. He is particularly convincing when playing a tipsy or drunk person.��(Unfortunately, the second lead,��Sibusiso��Khwinana, won���t get to enjoy the expected stardom that comes with the role. He was murdered at the end of��February��2019.)

Most of the actors are either from the theater or are first timers on screen.

Matwetwe��excels in its treatment of contrasts, such that one is made to oscillate between different emotions, which the film evokes in its portrayal of issues like mental illness,��femicide��and general economic hardships. For example, when��Borotho, a mentally ill man, is knocked down by a car. But this sombre scene quickly takes on an ironic turn when one recalls that��Borotho��had earlier been shown walking along the road holding a car wheel cap in his hands as though it was a steering wheel and he was driving a real car, when this was in fact not the case. Now lying on the ground from an impact of a real car on his body, with community members standing around him in horror and pity,��Borotho��goes on to say something that tears up the somberness of that moment.�����And to think that he does not have a license!�����Borotho��says, which at this point suggests that the driver of the car that knocked him down does not have a driver���s license, when he is the one who probably does not.

But there are also macabre scenes amid the inherent comedic characteristics of the film. One such harrowing moment is the exposure of the body of a woman murdered by her husband and kept in her bedroom until neighbors call the police, possibly due to the stench of a decomposing body. A deranged man, brilliantly portrayed by��Kagiso��KG��Mokgadi, is soon arrested by the police in a scene that reminds us of the hideous and murderous nature of some men.

Matwetwe��also aims to satirize the human tendency to posture.��Papi���s��character carries himself as if he has loads of personal experience and knowledge about girls and related matters, but when in fact he has never been with a girl before. The portrayal of black and visibly affluent characters in��Papi���s��cousin���s circles appears to be satiric too especially since these characters are made to talk as if they were white. The film portrayal of��Papi���s��speech and behavior also seem to mock the influence of African-American culture on South African youth.

It very sad that��Matwetwe��was initially shown at selected movie theaters, with a possibility of more screens being added on condition that the film performed well through ticket sales. This is tragic and unpatriotic to say the least, given that there is a flurry of very awful American films flooding the local film market. Granted, cinemas need to make money to stay operational, however, a fine balance needs to be struck in such a way that local film productions are nurtured and given the rightful platforms to showcase the talent that is ever so abundant in this country.

But in a poetic justice kind of way, the film, which was co-executively produced by the internationally acclaimed DJ and producer, Nkosinathi Maphumulo, popularly known as Black Coffee, would later account for over R4 million worth of ticket sales in a period of just over three weeks on the circuit, a performance that represents double its production budget. With various cinemas still showing the film, it is clear the figures will continue to rise.

April 1, 2019

Two people ‘cured’ of HIV. But we don’t have a cure for HIV.

HIV awareness in Darfur. Image credit Albert Gonz��lez Farran for UNAMID via Flickr (CC).

Earlier this month,���The New York Times���and others��published, in��violation��of a���media��embargo, world-shaking headlines of a ���cure��� for HIV. It���s huge news. 37 million people live with HIV and the extraordinarily resilient and adaptable virus has for decades kept a step ahead of cure researches. But the news was as confusing as it was explosive. First, because headlines claiming ���cure!��� quickly shrunk away into fourth-paragraph disclaimers about scalability and, second, because the word ���cure��� seemed to swap interchangeably with the more conservative word ���remission.���

Here���s what happened: two people who once had HIV underwent aggressive cancer treatment and then stopped their HIV medicine for long periods of time during which highly-sensitive HIV tests haven���t detected the virus. Timothy Brown, aka the Berlin Patient, once had HIV but, as far as we can tell, has been living without it for 12 years now. The London Patient, who has remained anonymous, hasn���t had HIV for about 18 months, according to an announcement at the���Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections���at the beginning of March 2019 and an article published around the same time in the journal��Nature.

As part of their cancer treatment, both men received bone marrow transplants from donors with a special genetic mutation called ���CCR5-delta 32.��� The mutation makes it hard for HIV to spread into certain blood cells. Both men went off their HIV medicine and the HIV hasn���t rebounded. When the Berlin Patient news broke 12 years ago, it sparked a rush of efforts to recreate the results, but the HIV eventually rebounded in every case, until, it seems, the London Patient.

HIV is a great hider, treatment drives it into nooks and crannies of the body where, tucked away at such low levels, even our most sensitive tests can���t find it. But if treatment stops, HIV normally pops out and begins to spread again. This is why some people avoid the word ���cure��� and instead say ���remission,��� meaning we can���t find the virus right now, but it may show up again later. After all, there is no official consensus as to how long remission should last before it should be called a cure and there have been plenty of��people��we hoped were cured but turned out to instead be in remission.

This discussion is significant beyond the scientific technicalities; headlines about an HIV ���cure��� have extremely dangerous potential. The history of HIV has often been ugly���hundreds of thousands of AIDS deaths��are more properly attributed to misinformation than the virus. Those deaths are tragic and inexcusable. The history of HIV is also, however, beautiful and inspiring:���great movements���fought inertia, ignorance and indifference with education, organizing, and now-famous campaigns that wedded science, law, and political pressure.���HIV is a political and social issue as much as it is a biomedical one���and we already have tools to stop HIV from spreading and keep people living with HIV healthy if only we do the political and social work to ensure everyone can access them. While we want and need an HIV cure, we must be cautious that dreams of a cure in the future don���t cause complacency for the life-saving action needed now.

All that said, supposing we use the term ���cure���, this is where we are: two people have been cured of HIV, but we (the rest of the world) do not have a cure for HIV. This is not a treatment many people can or should get���bone marrow transplants are expensive, traumatic, and chancy; risking, for example, new cancers, graft-versus-host disease, organ damage, and death. There is a reason we only give bone marrow transplants to people with serious cancer and not to everyone with HIV.��And, in any event, modern HIV treatment is designed to reduce HIV to an undetectable level anyway, at which point the person has a basically normal life expectancy and quality and cannot pass the virus to their partners or children. In this sense, the only practical difference for Timothy Brown and a person who takes HIV medicine is that the latter has to swallow a pill every day whereas the former underwent a procedure that almost killed him.��It is far preferable to live with treated HIV than undergo a bone marrow transplant, unless, of course, you need one for some other reason.

The development nonetheless holds exciting and fascinating significance beyond the Berlin and London Patients. For starters, the Berlin Patient���s cancer treatment was so brutal he almost died. The London Patient had a much easier time and achieved similar results, giving hope that things will continue to get easier. More importantly, the development pushes us into new understanding of HIV immunology and gives hope that gene therapy and editing might lead to a true cure in the foreseeable, though not immediate, future.

This hope should spur us up and onward. In the meantime, we have treatment that keeps people healthy and stops the spread of HIV. Yet���nearly half���of the 37 million people who need treatment don���t have access to it, and so, while we must work toward a cure, we cannot wait for one.

Senegal’s fear of outspoken women

Still from Maitresse dun homme marie

One would think��only a few weeks after��very heated presidential elections, which saw President��Macky��Sall��re-elected,��Senegalese would be spending their time reflecting about issues like the chronic youth unemployment, a failed education system, precarious healthcare, and the ever-present violence against women and children. But no, not really.��The��main conversation topic on TV, online and socially, is the new��drama��series��Maitresse��d���un homme��mari����(Mistress of a Married Man) produced by��Marodi��TV, which airs on the private channel 2STV. Only in its fifteenth��episode,��Maitresse��has garnered millions of views on YouTube and Senegalese social media buzz with debates about whether the series should continue or not.

Maitresse��follows the lives of five women in Dakar, some married, others not. Played by rising star��Khalima��Gadji, the lead character,��Mar��me, is the mistress of��Cheikh, a married man and father of one with whom she has sex.

Though the title of the series focuses on the mistress, the content is equally divided across the lives of the four other female characters who in their own right are multifaceted representations of contemporary urban Senegalese women. There is the guarded��Racky, a construction professional who lives with her controlling mother, and has never been on a date because she has PTSD from being sexually abused as a child.��Lalla��is the devoted wife of��Cheikh��and lives in a bubble because she believes that her husband is a saint.��Dialika��is professionally successful, yet she is married to��Birame, an alcoholic narcissist pervert who cheats on her and beats her, while his mother with whom they live, watches. But��some��might��view these other female characters as minor profiles whose purpose is to detract attention from what they call the series��� apology of promiscuity in the character of��Mar��me��and her relationship with��Cheikh.

In a��majority��Muslim country where women���s sexual desires and fulfillment cannot be conceived outside of marriage,��Mar��me���s��character is a courageous representation of a Senegalese woman who does exist in real life, but whom the male-centered culture does not want to publicly acknowledge on the grounds of religious morality. In one episode,��Mar��me��points to her sexual parts and proclaims: ���Sama��lii ma��ko��moom,��ku��ma��neex��laa��ko���y��jox��(My thing is mine, I give it to whomever I want.).���

Much has been made about the pleonasm in the series title. But there is more to the opposition to��Maitresse.��Some religious clerics��are outraged by the series because of its��representation of adultery in Senegal. But recently, what many viewed as a passing indignation by a few, is taking a serious stand as the Islamic��NGO,��JAMRA, announced a march��to protest the series. JAMRA accuses the film of perverting the morals of young people. However, since��Maitresse��is the first series in a budding local film industry attempting��to break away from the one-dimensional representation of Senegalese women as hapless wives whose sole existence is to be pretty and cater to the needs of their husbands, one cannot help but ask whether the outrage is about religious morality, or is it because of a phobia for the independent and outspoken women that the series profiles.

Since 2011, Senegalese television have gradually severed ties with South American novellas in favor of locally produced serials. However, the first franchises of this ���consommez��S��n��galais��� film industry, which are produced and written by men, often represent Senegalese women as subordinates to men. Characters like��Marichou��in��Pod et��Marichou��or��Soumboulou��of��Wiri��Wiri��go to great length in order to keep their husbands regardless of whether��they are chronic serial cheaters or abusers. Then came��Maitresse��whose executive producer,��Kalista��Sy, is a young woman with a mission to give women a voice and represent Senegalese society in a more realistic light, especially as it pertains to Senegalese men���s sense of entitlement and their treatment of women. Her female cast does not practice the��widely accepted��skin bleaching prominently featured in earlier series as the standard of beauty for Senegalese women. More importantly, the series puts women���s��experiences at the center of its storyline.��Mar��me��and her cohort are ambitious women with jobs and their lives do not center exclusively on their relationships with men.

In Senegal, Islam is often heralded as the monitor of all behaviors regardless of the fact that the republic is not an Islamic one and has a secular constitution. Despite the fact that the series raises awareness on sexual abuse, domestic violence, child abduction, parental irresponsibility, and evil��mother-in-laws���all of which are rampant in Senegalese society���critics are fixated on��Mar��me��and��Cheikh���s��adulterous relationship, something that is also widespread in Senegal where men wield polygamy as a religious right and are quick to say that Islam allows them to take up to four wives. It��is indeed possible that many second, third, and fourth wives have once been mistresses or not with their husbands prior to marriage.

While the series��� critics acknowledge that men sleeping with women who are not their wives is common, seeing it represented on national television and by Senegalese actors brings them too close to a reality they���d rather cover under the dark sheet of��sutura��(discretion) and religious morality. Yet, the problem is not with the character of��Cheikh��who is having sex out of wedlock. The outrage seems to be about an unmarried woman owning her sexual freedom.

Maitresse��is just putting a mirror in front of the Senegalese and the image they see is perfectly theirs. The real problem is that the producer is a woman, and the female characters are not like the ones Senegalese audience have been seeing. In Senegal, anything that does not view men in a positive light or��cater to their self-fulfilling understanding of women���s roles is accused of detracting from religion or culture. All too often, anything that gives Senegalese women agency or casts them in positions that differ from their��widespread subordinating roles is��labeled as a copycat of Western models as if Senegalese women have not been empowered before their society���s encounters with the West. It is absurd that the country���s claim of respect for women does not consider giving them a space in public discourse in order for them to voice their own viewpoint on matters that directly affect their lives.

It is interesting that this policing in the name of religious morality happens often when women attempt to have an opinion that is different from the patriarchal roles��that the culture imposes on them. There are many issues in the country that warrant a stand from religious clerics, such as the precarious conditions of the��talib��s, these children as young as three who are sent to cities��in the name of Islamic education but who end up as street beggars, making them vulnerable to all kinds of abuses, including sexual ones.

Furthermore, the Brazilian and Mexican novellas that the Senegalese have been watching for decades and the American films that are shown on national television during daytime have heavy sexual content as well as gun violence, but no one ever��organized a march to protest them. It is easy to say that a telefilm is corrupting the morality of young people when in Senegal children have unfiltered access to the internet where they are privy to indecent content including pornography. What is the role��of parents in all this? Since when is it television���s responsibility to educate children? Have Senegalese parents given up their role to the point that a telefilm is liable for the education or miseducation of children?

March 31, 2019

A meditation on home

Image credit Stephanie Urdang.

Stephanie��Urdang��didn���t��leave��South Africa at the age of 23 because she was forced into exile. She left because she ���hated Apartheid.��� It was the late 1960s���mid-hiatus between the��Rivonia��Trial, the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela and other anti-Apartheid leaders��(in 1964), the burgeoning of Black Consciousness��(from the late 1960s onwards), the��resurgent��trade union movement��(1973), and the Soweto uprising��(1976). Avenues for fighting Apartheid had narrowed; the comforts of whiteness expanded.

Urdang��grew up in a staunch anti-Apartheid family��(her father��practiced law��in��Athlone, a��coloured��township on��the Cape Flats), but very much a white South African, with all the trappings of privilege that her skin color guaranteed. Admittedly, it took her some time to ���understand the gross inequality,��� and it festered, eventually to the point that she ���didn���t seem to have a place��� in the South Africa of the time. She chose to move with her fianc����to start another life in the United States, where he would study physics. ���I never talked to anyone, but underneath I had great ambivalence about the decision. I couldn���t even talk to myself about it. I didn���t want to leave, but I couldn���t voice it.�����Following the banning of the International��Defence��and Aid Fund (IDAF),��where she worked in support of��political detainees and their families,��she felt��torn further. The only alternative she saw was to leave the country, get involved in the movement abroad and to come back at some point in the future.

Urdang���s journey from the leafy suburbs of Cape Town���first as�����a dutiful wife to be,��� later��as��an activist and journalist��during��the most difficult and exhilarating years of struggle for liberation on the African continent��and��alongside some of its most committed revolutionaries���is brought to life in her remarkable memoir,��Mapping My Way Home���Activism, Nostalgia and the Downfall of Apartheid South Africa.��It lives alongside the significant books she has written on women in��Guinea Bissau��and��Mozambique.

Home, for Stephanie��Urdang, is not an uncomplicated idea. It is, at once, associated with the familiarity of place, and of people. But it is also about a desire for a particular way of being, of freedom, of solidarity. The longing for home, for��Urdang, rested on a desire for a future South Africa free from Apartheid.��Urdang���s��nostalgia was not for the past, but for the future, for a��democratic��South Africa. She wanted ���the food, and the house, and the mountains��� but couldn���t have the place without the change.���

This meditation on questions of home, belonging and solidarity��is��timeous, emerging as it does in a moment of resurgent ethno-nationalism everywhere and its accompanying xenophobia (prevalent in the once-longed-for South Africa).��Urdang���s��book helps us think about border crossings,��borderlessness��and literal liberated zones as domains of the everyday rather than the expectation of bourgeois privilege.

Activism, nostalgia and the downfall of Apartheid are dealt with in fascinating reflections and witness accounts that reveal��Urdang���s��narrative gifts, her incisive mind, and her deep commitment to feminist principles and the struggles against colonialism. Her enduring relationships with African revolutionaries in Guinea Bissau, Mozambique and Egypt offer a different and refreshing lens through which to understand the heady and often dangerous period of the fight for liberation in the so-called ���late��decolonizers�����and in post-independence Africa. As��Urdang��recalls in an interview��with the authors:

The late 1960s and 1970s was such a vibrant time. We really believed that we would change the world, and that capitalism was going to fall���especially after the liberation victories in Mozambique, Guinea Bissau and Angola. These were the countries that would put in place the ideologies of socialism, the theories of��[Amilcar]Cabral��and other revolutionary thinkers, for the benefit of the people. Poverty would be dealt with. This is what spurred us on.

Urdang��tells the story of a period of her life that unfolds through a series of mostly defaults and some design.��Her��trajectory, for a time, was driven by the privileges afforded by her race and class, as well as the self-doubt and lack of confidence that were a mark of her gender. In the US, she began working for a community organization, to provide support while her husband completed a PhD. She may have been unaware of it at the time, but now, through her memoir, through her decades of political work,��Urdang��understands well the advantages that she had:

We came from countries where there was a struggle, but I got on a plane and I came here (to the US). My husband had a scholarship. I didn���t think about the extreme privilege of that. We had no money. We lived in poverty while he did his Ph.D. But I knew we would be out of it; that this was temporary.

For most people, significantly in��Urdang���s��adopted country, this condition of��precarity��is permanent. Her memoir is thus suggestive of a new longing���for a place, a politics of the unsettled, of building ���a notion of home that is post-border in some ways.���

After��two��years in the US,��Urdang���s��desire to continue the fight against��Apartheid��led her to the offices of the American Committee on Africa (ACOA). There, she joined the Southern Africa Committee and was asked to edit the important��Southern Africa��magazine. As editor, she began to travel to Africa (to Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, Egypt and Ethiopia), expanding her horizon beyond the struggle in South Africa.

Moreover, her relationships with African women in these countries profoundly impacted her life, her work, her politics and depth of experience:

These friendships were extraordinary for me. I got so much more from them. They were going on with their work. I had come from such a different place, culture, experience. It sobered me. Made me think about what was important about my life, about community. I had a sense of home in so many places, because I connected deeply and primarily with women. There was such a generosity of spirit on their part.

Urdang���s��memoir stands out in its narration of her time at��Southern Africa. She produces what can only be regarded as a feminist memoir: a genre through which the self is neither condemned to obscurity nor elevated to the center of social processes. She, at once, participates in social change as she is produced through her interactions with others.��Urdang��has an important story to tell, of her own life, perspectives and contributions. But her ideas, hearts and actions are crafted in community with others. They are not a transcendent condition.�� This is a major contribution to memoir writing.

Her story centers short biographical accounts of the many women with whom she forged community, or solidarity, or love. The vignettes of these women���s lives suggest that hers is conditioned by them. Even the women���s groups that��Urdang��participates in and builds are afforded agency in the book.��Urdang��takes seriously what Chandra��Mohanty��later reminds us, ���Beyond sisterhood there are still racism, colonialism, and imperialism���. As such,��Urdang��participates in producing a sisterhood that is ���forged in concrete historical and political practice and analysis���. She produces a memoir that projects a woman who has found her voice through activism with other women, at the same time as it refuses the centering of her story over others, or detracting from the broader historical narrative.

Urdang, thus, finds home.

March 30, 2019

The great Somali apologia

Image credit Tobin Jones for UN Photo via Flickr (CC).

The first realm of fear��for Somalis��comes��from��their��leadership’s��apologia.��This is why Somalis have��to apologize.��There��is no��avant��garde, but merely���vacant blue corporate suits. Let us give you a taste of what we live with in��Mogadhishu. Every time you project terror,��remember how we live here.

Xamar��(Mogadishu) has a certain relationship with mortality. It is so close��to��the line between the living and the dead. Anyone of us can go, all it takes is��Al��Shabaab��imposing on your routine. It��is��amazing how as soon as the carnage happens, folks start to clean up, build,��wipe the blood off the asphalt and move on. The mindset resets and the daily returns. As if,���this���marauding danger���is pushed back to the inner or outer reaches of the mind. Where it latently languishers until the next return.

Out of the daily, I see and understand it myself somewhat as a condition of anyone in the midst of such colossal uncertainty. In���this���mode,��we all reflect in the first 24��hours:��first how close you were��(in my case I am staying about 100 meters��away from the bomb, woken up by shattered glass, fixtures strewn along with from the aftershock) gaping holes where the door window was. Thinking,��oh shit, they are in the compound.��Next,��they��will��be��coming to the rooms to get all the��murtids!��The apostates. The backsliders.��So, I��dressed quickly and did not have time for shoes.��Made a dash to the back of the compound Exit, exit before��I��make it to the living quarters. They always lay siege to the hotel and take everyone with them. Of course,��I am��off��to hell and of course they to��paradise.

Outside the hotel workers and a coterie of guests were running like chickens without heads.��Like myself, an older gentleman was fully dressed,��but without��socks. The back of the compound is a maze of structures a from many reincarnations of the structures in Somalia���s��heydays.���This���was offices for a robust��USAID��presence. The old man owned the vast compound��which��gate reaches the main drag. Approximately, a��New York block and change away from the carnage.

In���this���confusion, my purpose is palpitating,��pressured by the window of time. I am (we are) all thinking,�����From the gate to us it will take them a few minutes to reaches us.��In the back.�����There is���a young Somali composer from the��UK��rocking his underwear and completely gone. Running back and forth, completely “gone.”��He finally settles on following some us who seem to have a sense of purpose. I ask one the workers f there is another��exit. ���Yes,������he says. We both move urgently. I��follow.��The difference between the unsettled to our degree, of the young man from the��UK,��� is��that it was his first such experience of an explosion. The two of us are not looking back but we hear the old man, young man and others sounds and pace behind us. We venture through what was possibly a vast kitchen in the past and the worker starts to remove a large round metal plate from its leaning position on the wall. I help remove���this���heavy plate and some other material to expose the bottom of the back wall, four or six blocks missing. Leaving the wall exposed enough for a slim person to wriggle through. I was the first to wriggle followed by the worker. We were outside the compound and into another. Just a large walled compound with a��small heard of black-head lambs grazing in the far corner, oblivious it seems to us��and��the��earth shaking��tremor from the explosion.

We seized a moment of reprieve having located and gotten away from the immediate danger of the hotel enclosure. We sat on our haunches, taking in the space between us and outside from the compound. The side roads were visible in far reaches beyond the lambs.��� We remained there just outside the wall for minutes. I���could���now see smoke bellowing intensely beyond the walls.��� I realized then that��the explosion was somewhere else. Close,��but not��to��the hotel compound we had just escaped from. The line behind never came through the wall to our side. We decided to crawl back. The thorny grass bit me, already my mind had gone from certain murder to worrying about the prickly thorny grass. We got back and ended up going to the place (front gate) we were so desperately getting away from.

Soon we talked about what happened, who was hilarious:��me,��no shoes, first to get out, the old man with socks. The composer whose��legs were still quivering standing in a banquet hall��alone,��petrified. Still not convinced the danger was over. He left the very next day when the roads were open again. The old man said he didn’t know he���could���run like that. He thought that. Was just a memory.��� Who jumped over the walls,��9��feet��with razor��wire.����The other standing in���this���middle in the middle of his upstairs disheveled room. Fixtures on his bed, shattered glass everywhere. He stood there immobilized looking below at the proceedings, us running for our lives! He seemed tranquilized by the whole affair. He stood their peering from the second��floor. From a now empty space where the window and its fixtures were. We talked to him on our return from the escape almost shouting in conversation. He managed to laugh at us, himself and just found his immobility���so hilarious.

March 29, 2019

Cyclone Idai and climate justice

Image credit Climate Centre via Flickr (CC).

Nearly two weeks after Cyclone Idai struck the coast of Mozambique, near Beira, the flood waters are receding to reveal a shattered landscape. Houses and roads are washed away; crops awaiting harvest are destroyed. Confirmed deaths number in the high hundreds across Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi, with the total still unknown. Emphasis is shifting from the rescue of survivors clinging to treetops and rooftops, to provision of food, housing, and medical care for hundreds of thousands left homeless.

Even as local relief efforts gear up, there is a need to also focus on broader global implications. The causal connection between climate change and extreme weather events, such as Cyclone Idai, is clear. The need for climate actions in both poor and rich countries is beyond dispute. These include making the response to crises sustainable, increasing resilience to the effects of climate change through adaptation, and rapidly accelerating action to cut greenhouse emissions from fossil fuels.

Whose responsibility should this be? At the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, the first global climate agreement affirmed that much of the burden should be shouldered by the wealthy countries:

The Parties should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof.

Paying the climate debt

The outpouring of support is impressive, but a key test will be its sustainability. Beyond immediate disaster relief, sustainable global responses to climate change require greater and more predictable funding to strengthen the resilience of the most vulnerable regions.

There is no shortage of proposals for action, such as this guidance from the UN Environmental Program. But implementation will depend on political will in the countries that can afford to pay. This requires wide recognition of the ���climate debt��� owed by fossil fuel companies and rich countries whose emissions have contributed the most to destructive climate change.

Poorer people and countries, which have contributed the least to climate change, are also the most vulnerable to its effects. The price paid in lost lives and livelihoods falls disproportionately on them. This is seen not only in Cyclone Idai, but also in the recent flooding in the US midwest, where Native Americans on the Pine Ridge Reservation are finding recovery far more difficult than farmers in neighboring states.

Those who should pay more to prevent and mitigate climate change, and to cope with climate disasters, are still evading their responsibilities. In the words of Dipti Bhatnagar, coordinator of Friends of the Earth Mozambique, speaking on Democracy Now, ���This is about the rich countries ��� We need to stop dirty energy, dirty and harmful energies everywhere. But this is about historical responsibility. So, that needs to happen in the northern countries first, to stop fossil fuels, to stop dirty and harmful energies.���

Bhatnagar and other climate justice campaigners such as #Decoalonize in Kenya also call for an end to projects such as Exxon���s natural gas project in northern Mozambique and new coal mines in Kenya, South Africa, and other countries. While national governments, in both North and South, remain slow to act, the range of action by civil society and subnational governments is expanding. Examples include the rising tide of lawsuits against fossil fuel companies and the March 15 climate strike in more than 112 countries.

The Green New Deal in the United States, and similar efforts in other countries, must take on the powerful forces of the status quo. They must also be framed within a South-centered vision that highlights global climate justice, addresses inequality both within and between nations, and targets the strategic reallocation of wealth from the most privileged sectors to the common good.

This in turn will require structural changes, especially the identification and progressive taxation of corporate and individual wealth, much of which is hidden or exempt from taxation. In addition to saving lives in the present, South-North networks built in response to crises such as Cyclone Idai provide a foundation for demanding these critical changes.

The March 22 issue of AfricaFocus Bulletin includes selected news, analysis, and videos on Cyclone Idai, and links to organizations accepting contributions.

Samir Amin and beyond

The late Samir Amin (right) on a panel with Robert Brenner (UCLA), Carlos Prieto (Universidad��N��mada), Ho-Fung Hung (Indiana University Bloomington) and Perry Anderson (UCLA)��in Madrid, Spain��in 2009. Image credit Museo Reina Sofia via Flickr (CC).

When the sad news came of Samir Amin���s passing on August 12th, 2018, a plethora of beautiful obituaries were published in his memory (see for example��here,��here,��here��or��here). These have made it more than evident not only how important his scholarship and work through the World Social Forum��is, but also what an extraordinary person he was. We never had the privilege of meeting Samir Amin in person, but he was very kind to grant us an interview over Skype for an��e-book��we put together in 2017 on the contemporary relevance of dependency theory (since published by the��University of Zimbabwe Publishers). Now we wish to unpack his contributions to our understanding of political economy and uneven development, and explore how his ideas have been interpreted and��adopted in different contexts,��and their relevance today.

Transcending��boundaries:��scholarship��on a��world scale

Samir Amin���s work is not just relevant for Egypt, for Senegal, or for the African continent. His insights stretch beyond national and regional boundaries in tireless efforts to analyze how international capitalism manifests itself both at a global level, and in specific contexts. What is particularly impressive about Amin is that he made no attempts to conform to the “mainstream” of the profession, nor of any discipline or theoretical tradition. On the contrary, his work transcended disciplinary boundaries, combining insights from economics, politics, and history, and his Marxist analysis was deeply critical of many of his Marxist contemporaries. As he once said in��an interview, ���I consider a Marxist as starting from Marx but not stopping at Marx.��� Amin argued that many��western��Marxists neither went beyond Marx nor did they acknowledge and analyze the intrinsically imperialist nature of capitalism.

Amin became one of the pioneers of dependency theory (see��here), which in the��1960s and��1970s was a hotly debated theoretical framework,��with the central idea that core countries benefit from the global system at the expense of periphery countries,��which face structural barriers that make��it difficult, if not impossible, for them to develop in the same way that the core countries did. Important for Amin was the notion of unequal exchange (see��here).

It is��particularly within the African continent that Amin made efforts to build institutions and foster dialogue and debate. Amin founded both��Third World Forum��and��CODESRIA. As��Issa��Shivji��put it��in his obituary, ���he has consciously done everything possible and seized every opportunity available to provide space, forum, and a training ground for young African scholars.���

Why is Samir Amin not��reflected��in��most contemporary curricula?

When Amin published in the first issue of Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE) in 1974, the��editor wrote: ���It is our hope that his work, which represents the most significant African contribution to the debate on underdevelopment, will be studied widely and discussed critically.��� Indeed, his work has been discussed critically and read widely. As Mahmoud Mamdani��wrote, Samir Amin ���introduced an entire generation of young scholars, myself included, to think of under-development in historical terms.���

However, Amin has not been studied as widely as perhaps the ROAPE editor, and others, had hoped. Due to enduring eurocentrism in academia, few contributions by thinkers from outside of the��western��world make it to textbooks and curricula in universities around the world. Indeed, we know from our own experiences with studying political economy and development in different disciplines and in different regions, that Samir Amin is rarely required reading, regardless of the level of study. University of Zimbabwe is the exception,��as several of Amin���s key articles and books are on the curriculum in��its Economic History program.

This exclusion of non-western��scholarship has led to calls from across the world for a decolonizing of the curriculum (see��Chelwa��2016��on Economics in South Africa,��Jayadev��2018��on Economics in India and��Sabaratnam��2017��on UK academia more generally). In��economics��the situation is perhaps the most dire, where not only is non-western��scholarship excluded, but since the 1970s there has also been a narrowing of the field with the rising dominance of neoclassical economics. This means that all forms of theorizing about dependency, exploitation, and historical materialism have been removed from mainstream economics��teaching.

Samir Amin���s��work has been a great source of inspiration to us, and we believe it is a loss to students interested in questions of uneven development if they are not confronted with Amin���s analyses. Amin���s core contributions to economic and political thought, in particular his notions of unequal exchange, the role of imperialism, eurocentrism, and the need for delinking, are still relevant to debate today, and should therefore be made accessible to students across disciplines. Nevertheless, particular new developments, such as, for instance, the intensification of��financialization��globally and the rise of China, mean that his conceptualizations��might need to be��rethought within new contexts. We also think that there is a need for greater intellectual exchange between those who are closer to Amin���s own generation, and younger scholars who grew up intellectually under different political, economic, social and (not to forget) academic circumstances.

Samir Amin and��Beyond

With the desire to both celebrate Amin���s intellectual legacies and to interrogate��the relevance of his ideas today��across different contexts,��we are currently��working on an edited book��titled��Samir Amin and Beyond: Development, Dependence and Delinking in the Contemporary World.

The book will cover key themes, including the economics of imperialism, unequal exchange, crisis, decolonization and delinking, and feature chapters by a range of both senior and younger scholars. These include professors��Marisa Silva��Amaral,Sabelo��J.��Ndlovu-Gatsheni,��Jayati��Ghosh,��Kin-chi Lau,��Adebayo��Olukoshi��and��Cathrine��Scott, as well as��Ziyana��Lategan, Francesco��Macheda��and Roberto��Nadalini, Petronella��Munhenzva, Francisco Perez, Natasha��Issa��Shivji,��Ndongo��Samba��Syllaand��Salimah��Valiani.��Through this book, we are hoping to contribute to a dialogue��across generations, disciplines and regions on��the contemporary relevance of Samir Amin��s prolific contributions to social and economic��critical thought.

March 28, 2019

The political viability of anti-immigrationism

Image credit Jack Zalium via Flickr (CC).

Political pressure regarding migrants in western countries remains ambivalent and highly contested, representing one of the most dominant sociopolitical issues��some��of the countries face. In Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, caught between the vice grip of anti-immigrant demands of his party���s right-wing��(and an election on April 9th), and the country���s activist groups and political left, recently��withdrew his plan to force out roughly 40,000 black African migrants.��However, this has been framed as a demonstration of political peril, ���trapping nationalist leaders��� between the demands of the xenophobic and the progressive, relegating black peoples to the role of pawns in��a��chess match between white peoples more interested in the ethnic purity and image of moral integrity than the well-being of��migrants and refugees.

Africa is the site of anti-migrant policy testing writ large; the West, including Netanyahu and Israel, have used African nations as sites where they have implemented mass deportations; police raids of suspected migrants; and even voluntary repatriations; or in the case of Israel, paying black Africans money to leave Israel. These represent a form of racism passing as immigration control, and are becoming incredibly commonplace as Europe looks to the physical space of African nations for potential solutions to its racial and demographic anxieties.

Netanyahu���s renege on forcibly expelling black African migrants from the country comes just months after Israel enacted a policy to��pay black Africans money to leave the country or face imprisonment. As��far back as 2013, Israeli politicians introduced a bill offering migrants $3,500 USD to leave the country, demonstrating the recycling of migration������management������tactics over time.���Recently, Israel has begun��recruiting civilians to temporarily serve as inspectors to aid state authorities in the expulsion of black Africans, demonstrating Israel���s expressed and determined efforts to remove them��from the country. However, the presence and availability of Uganda and Ethiopia as a backdrop���and Africa more broadly���signifies the centrality that���access���to Africa maintains within Israel���s larger anti-immigration policy.

This shouldn���t be framed as a story about the difficulties of being a conservative leader in the��West who is dealing with migration, stuck between anti-immigrant sentiment on the right and activist pro-immigrant groups on the left. Unfortunately, the political possibilities racism offers have proven to be more than enough to sustain actual��debate���rather than outright opprobrium and social rejection. These ideas have currency and political utility, and pro-immigrant groups have had trouble appealing to the������moral authority������of conservative politicians who want racial purity in their countries.

Israel and Netanyahu have reached a point where their anti-black tactics have met considerable opposition from protestors and the political left.��However,��these gains are quite rare. In the US,��President Trump��allowed a government shutdown to rage on because of��Democrats������unwillingness to fund��the construction of��a wall on the southern border with Mexico.��In August 2018, France passed a��strong anti-immigrant measure����satisfying the public who thought that French immigration policy was�����too lax.�����These thinly veiled racist conceptions of��what it means to be French��have been part of the French political landscape for years and has continued to give white French people a sense of demographic anxiety that fuels the debate amid the growing concern of im/migration.��Furthermore,��France and the EU have not only enacted policies within their borders, but have moved to implement migration policies and activities��within��Africa.��This political exploitation of migrants in Europe provides some public cover that serves as justification for Europe to physically extend its borders southward through African sovereign nations.

Under intense pressure from the EU,��Niger passed the��anti-human trafficking law in 2015, allowing its military to arrest and jail migrant smugglers, and the authorities to bring migrants to the police or the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the UN agency responsible for coordinating (anti-)migration activities in Africa. This�� anti-human trafficking law in Niger has been incredibly effective. At the zenith of migration through Niger in 2015, approximately 5,000 to 7,000 migrants traveled through��the country��to Libya, but the criminalization of human smuggling and trafficking has reduced those figures to about��1,000 people per week, according to the IOM. In other words, these anti-migration efforts are working, as they stifle black movement. Politicians can show��that��they are blocking Africans from moving to Europe at all costs and show how their policies are������working������there; providing specious justification for continuing border projects including the expulsion of black peoples���often via racial profiling, assuming all blacks are migrants without papers.

The viability of these��anti-immigrationist policies and the ascendant power of the groups who peddle them, is sustained by the aggravated anxieties of Europeans��wanting to preserve their perceived entitlements to neoliberal pursuits without many of the individuals who support that lifestyle through their exploited labor. Marine Le Pen��along with the populist right-wing party Dutch leader Theirry Baudet, among others across western Europe, have advocated xenophobic, racist sentiments and endorsed anti-immigrant and anti-migrant policies in their countries, and have called upon Europe as a whole to��fortify its borders. Beyond this, anti-immigration and xenophobic policies of Europe with respect to black Africans has been able to lean on the assumedly ���non-racial��� and ���technocratic��� migration projects within���Africa.

The anti-immigrant xenophobia endorsed and ratified by Netanyahu, Trump, Macron and others illuminates how politically favorable the current social climate is to these racist and xenophobic policies, even as we experience a more ���woke��� social era. If anything, cases like Matteo Salvini using effective populist tactics to��nudge Italy to fully embrace the far right��and its anti-immigrant leanings, indicate how Europe���s historical, geographic and economic proximity to Africa will continue to serve as lynchpins in the uneven racial relationship that Europe has enjoyed at the expense of black peoples. Many African nations, most of which are former European colonies, largely remain sources of extractable material and socio-political resources for European powers.��Even in the case of countries like Israel and the US with anti-immigrant leaders who have faced pressure from rights groups, they can still impress their anti-immigrant base and activists by playing political football with human beings. With Netanyahu stumbles through the political��minefield in his shaky reelection bid, supporters and detractors of his anti-immigration policies will pay close attention to how he uses his new��right-wing coalition��around��anti-blackness and xenophobia to secure votes��in the upcoming April 2019 presidential election.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers