Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 228

March 12, 2019

Against Zionism

Image credit Heri Rakotomalala via Flickr (CC).

In 2003,��Herzlia��High School, the apex of the private Jewish school system in Cape��Town, South Africa, awarded me ���Best All-Rounder�����in my grade 12 year,��though it didn’t grade my final Jewish History research project. My paper was titled ���Palestine: A Stolen Land?��� and subtitled ���The Establishment of Israel: Zionists, Palestinians, Democracy and the UN Partition Plan.���

Contrary to what people think,��Herzlia’s��official religion��is not Judaism; it’s Zionism.

In November 2018, two grade 9 students��kneeled in protest��at��Herzlia��Middle School���s prize-giving when the Israeli national anthem was played. While the teenage students did not make a verbal statement, a voice recording by one of the two students, circulated at the time on WhatsApp and other social media, articulates the students��� principled intention to demonstrate their disagreement with the current Israeli regime���s actions��and to challenge��Herzlia���s�����big problem with restriction of information ��� when they only teach you one side of the story ��� pro-Israel.���

The��two protesting students wanted to show fellow students that�����normal humans��� like themselves and ���not terrorists�����are sympathetic to ���pro-Palestinian ideas.�����The recording��also advanced a third rationale:�����I felt really strongly connected to��� surfacing the ���huge divide in the Jewish community [between] pro-Palestine or pro-Israel,�����which is often unspoken to avoid conflict. As a result,��division and anger persist without ���discourse.���

In response, the��Director of Education��of the��United��Herzlia��Schools (the schools��� corporate entity)��sent a swift letter to parents, which condemned the teenagers for ���deliberate and flagrant disregard for the ethos of the school [���and] blatant flouting of [���]��Herzlia���s��Zionist values.�������The letter asserted the teenagers would face ���disciplinary and educational�����consequences:

the students could not wear their colours for six months nor represent��Herzlia��for six months. They must write two��3,000 word��essays, write an apology letter, attend four meetings with elected community members, and are not permitted to attend grade nine farewell. They also may not talk to the media.

The two teenagers have since been named, shamed, vilified and victimized���though one-hundred-odd alumni then��signed a letter��in support of the students��� (right to) protest. According to these��alumni,��Herzlia���s��response is ���not surprising��� and is ���deliberately one-sided��� about Palestine-Israel.��Indeed,��the school���s ���ethos��� is openly and�����proudly Zionist���; it educates-and-disciplines (or re-educates ���undisciplined��� teenagers) in orthodox Zionism.

The��Director of Education��then��gave an interview to the Jerusalem Post where he��assured��Israelis that the two students are Zionists, and��Herzlia��is a ���proudly Zionist��� school. (Incidentally, the Jerusalem Post was edited by a South African Zionist ��migr�� to Israel from 2011 to 2016).

But why shouldn���t the two protesting teenagers be Zionists (inasmuch as they are)? Isn���t��the problem��just contemporary Israeli government policy, or prime minister Netanyahu, and not Zionism itself?

In December 2017,��a��16-year-old Palestinian��Ahed��Tamimi was imprisoned for 8 months by Israel after slapping an Israeli soldier on her family���s property���hours after Israeli soldiers shot her 15-year-old cousin in the face. This was not Tamimi���s first fight for freedom: in 2015, a��video��went viral of her biting an Israeli soldier who was arresting her younger brother. Consequently, in 2016, she was��not granted a visa��by the United States government for a��speaking trip���entirely unsurprising, given the US establishment���s ���deliberate and flagrant��� decades-long support for Zionist Israel.��An��editorial��in��the��Israeli paper Haaretz (which has a liberal reputation),��at the time of��Tamini��biting the soldier, noted:

The video clearly shows, once again, the truth about a great deal of the IDF���s operational activities: chasing children.��[���]��It���s hard to blame��[the soldier involved]. An army that fights children and chases them as they flee is an army that has lost its��conscience.��The only way to change the situation is to change the reality.

The Haaretz editorial did not say when the Israeli army lost its conscience���nor when it started ���fighting��� children. Also omitted is the fact that the Israeli army murders Palestinian children regularly: on average, more than two every week since 2000 (as Noam Chomsky��put it; data from respected rights group��B���Tselem��among others). Also passed over in silence are all the children who live in Gaza, now widely labeled an ���open-air prison.���

Yet the Haaretz editorial points to the ongoing Israeli Zionist policy of changing reality on the ground. Thus, Israeli cabinet minister Uri Ariel was��more direct��in calling��teenage��Ahed��Tamimi a ���terrorist��� for not having learned the lesson taught, and thus being an undeterred, obstructive reality to be removed: ���I think Israel acts too mercifully [���] Lack of deterrence leads��to��the reality we see now��[���]��we must change that.���

Indeed, changing reality on the ground���from occupations of Palestinian land and livelihood resources, through military expulsions and murders, to extensive expansion of Israeli Zionist settlements���has been consistent Israeli Zionist policy for decades. Such policy is remarkable only for its consistency across governments; and for the very limited comment this draws in corridors of power, and on pages of establishment newspapers.

Today, the Israeli prime minister and a number of party-leaders-cum-cabinet-ministers, explicitly foreswear any Palestinian state. In contrast, Israel���s unending conquest of ever more Palestinian land, and severance of Gaza from the West Bank���itself divided into apartheid-Bantustan-type cantons���have led many to conclude the only outcome possible is a single state of some kind.

Zionism is a chauvinist, racist, ethnically-nationalist Euro-modern settler-colonialism, which manipulated the Holocaust to establish an ethno-nationalist colonial-settler state in Palestine, called Israel as an alleged haven for Jews. All this on land stolen and occupied after the��Nakba, meaning ���catastrophe,��� which marked the expulsion of half of the Palestinian population. Today, Israel remains a state in which citizenship is legally constituted in terms of ethnicity (���Jewish��� or ���Arab���; not ���Israeli���). ���Jew��� and ���Jewish��� are legislated and enforced as a superior and exclusionary ethnic-racial identity. Only ���pure��� Jews are recognized and treated as full citizens. Palestinians, exiled Palestinian refugees, and children of Israeli-Palestinian marriages are excluded, physically, from citizenship and/or return; Arab-identified nationals are systematically made secondary citizenship through discrimination in education funding, land ownership, etc.

This colonial-settler, ethno-nationalist racism extends to African migrant workers and refugees, who��suffer��official and popular anti-Black-African racism, including their being labelled�����infiltrators���, used to��justify plans��for��deportation en masse. Actually, darker-skinned Mizrahi Jews in general, and Ethiopian Jews in particular face racist discrimination. For instance, Ethiopian Jews��continue to protest��the�����special approval�����they need to ���return��� (emigrate-as-Jews) to Israel (where many also have family). In turn, the Israeli government has been forced to��admit to��widespread sterilization��of Jews from Ethiopia; despite the country���s loudly proclaimed claim as the ���only democracy in the Middle East.���

What Israel, and much of the��Herzlia��community, and many in the Cape and South African white Zionist communities would rather avoid (or only conveniently manipulate) is that to be Jewish is not inherently or necessarily to be white. There are long histories of��darker-skinned Jews��in the Middle East, as well as��African and/or Black Jews��in today���s��North America and the Caribbean. The East-European Ashkenazi Jews only became white when they fled to racist South Africa, or the United States. The increasing Zionist insistence on the racial and ideological purity of Israeli Jewishness is a mark of European colonial white supremacy and anti-Black racism.

Certainly, all this is��highlighted��in the current period, in which ���democratic��� Israel has been changing reality by reinforcing Zionism internally and internationally���including against, and/or at risk to, Jews. Rebecca��Vilkomerson, banned from Israel alongside fellow Jewish Voices for Peace colleagues from the US,��points out��what is clear:

One thing that has definitely happened in the Trump era is that [���] you can��love Israel and still hate Jews��and often I think��a deal with the devil��is being made by a lot of Jewish organisations, that as long as a person supports Israel, they��give them a pass on anti-Semitism.

Thus, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu was one of the first to��congratulate��the open fascist Jair��Bolsonaro��after he was elected president of Brazil, saying he was ���confident of [���] great friendship [���] We await your visit to Israel.�����And the��prime��minister��doesn���t hide his affinity for Donald Trump, and has repeatedly called a ���true friend of Israel,��� sometimes adding that��Israel has no ���greater friend.�����Netanyahu and Israel have embraced another�����true friend of Israel�����in the person of neo-fascist Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orban.��In 2017, Trump himself��responded��to an orthodox Jewish journalist���s question about rising anti-Semitism in the US with Netanyahu���s endorsement (of Trump) as the only evidence needed. Throughout, Trump, Orban, Netanyahu, and��Netanyahu���s son��(aged 26), are all currently engaged in scapegoating Jewish Hungarian-American billionaire-philanthropist George Soros as the evil ���puppet-master��� behind opposition to their actions, using the explicitly anti-Semitic tropes of the��wealthy Jewish ���globalist�����and sinister�����happy Jewish merchant.�����One��consequence of these leaders��� common anti-Semitism while asserting Zionist Israel, and especially Trump���s license and encouragement to the anti-Semitic right, was, of course, the murder of 11 Jews at a synagogue in��Pittsburgh��last October.

What is not yet evident to���or else still wilfully denied by���those in the Cape Town and South African Jewish communities who enforced and/or supported��Herzlia���s��Zionist ���disciplinary and educational��� consequences, as well as those in Israel and internationally who cheered along, is��that��Zionist ethno-nationalist, racist identification of Jews is entirely compatible with anti-Semitism up to and including the murder of even white Jews living today in the United States, Israel���s ���greatest friend.���

Today, Netanyahu and Israel are reinforcing, enabling and sometimes��weaponizing��the historical co-existence of Zionism with anti-Semitism. Before Netanyahu���s congratulations to��Bolsonaro, Israel was��selling weapons��en masse��to Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte, an authoritarian far-right mass-murderer. The most recent sale was concluded on Duterte���s trip to Israel��in 2017, during which he also visited the Holocaust memorial��Yad��Vashem. This is the same Rodrigo Duterte who��the��previous year��likened himself to Hitler��and expressed admiration for the Nazi leader.

In stark contrast, and against Zionism, in��Ahed��Tamimi���s��video message��to the First World Forum on Critical Thinking in Argentina last��November, the teenage freedom fighter insisted:

along with inheriting occupation and suffering [���] “We inherit the revolution. [���] Palestinians see themselves as fighters for liberty, not victims. So, I hope that you too can see us as fighters for liberty.”

Tamimi encouraged each of us to make a choice: ���Support us in the struggle to obtain [���] liberty, justice, and democracy. That���s the best way to support us.���

As each of us makes our own choice, what��more��can�����we������including everyone connected to the South African Jewish community���learn here?

Rafeef��Ziadah,��Palestinian��poet-activist,��points the way.��Ziadah��narrates that�����When the bombs were dropping on Gaza,��� she��was��asked a question of the kind ���we Palestinians always get���:�����Don���t you think it would all be fine if you just stopped teaching your��[Palestinian]��children to hate?���

What about��Herzlia���s��Jewish children?��We must learn from��Ziadah���s��poetic��(four-and-a-half minute)��response:�����We Palestinians wake up every morning to teach the rest of the world life.”

Against Zionism, we must��choose to��learn and teach life.

Is Ousmane Sonko the future of Senegalese politics?

Image: Ousmane Sonko Twitter.

On Thursday,��February��28th, Senegal���s electoral commission announced the provisional results of the country���s presidential election.��Macky��Sall��won re-election��in the first round with 58.27 percent��of the vote, eliminating the possibility of a run-off where opposition support could have coalesced around one candidate. Despite popular opposition, especially in and around the capital of Dakar,��Sall��not only received a majority of the vote, but surpassed the 55.90 percent��Abdoulaye��Wade won��during��his re-election��in 2007.��The four other candidates on the ballot��have��rejected��the results of the election, but have decided not to challenge it in front of��Senegal���s Constitutional Court.��The result��was also��confirmed by Senegal���s Constitutional Court.��Idrissa��Seck, the former prime minister and mayor of��Thi��s, finished second with 20.50 percent of the vote, followed by��Ousmane��Sonko��at 15.67 percent.��Sonko���s��showing,��particularly��among young people,��will make him a formidable challenger in the 2024 election, especially given that��Macky��Sall��will be prohibited from running again.

A rapid expansion of infrastructure has marked��Sall���s��first term, including the opening of the new Blaise��Diagne��International Airport outside of Dakar,��and more recently the inauguration of a bridge across the Gambia River to facilitate traffic��between��northern and central Senegal to the distant��Casamance��south of the Gambia. The bridge is a particularly notable accomplishment as��a multi-national challenge that has frustrated��citizens and governments��dating back to the colonial period.��Perhaps more importantly, the seven years of��Sall���s��first term have also seen the construction of new and improved roads��and other infrastructure projects��across��the country. Opposition supporters argued that��the president��focused on infrastructure, not jobs, and is leaving Senegal���s young adults behind while consolidating��the country���s economic gains��within��a narrow elite class.

Two major opposition candidates in the 2019 election were supposed to be the former mayor of Dakar,��Khalifa��Sall, and Karim Wade, the son of ex-president��Abdoulaye��Wade and a former ���super minister��� given charge of much of the government���s budget during his father���s presidency. Wade, representing his father���s Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS),��was convicted��in 2015 of��embezzling��178��million euros��during his father���s administration, a figure many suspected was an understatement.��Macky��Sall��pardoned��Wade in June 2016, after which he went into exile in Qatar.��Wade was never particular popular (he lost an election for mayor of Dakar while his father was president), but his father���s popularity would have lent him some validity that may have taken some votes away from��Sall.

Khalifa��Sall��(no relation to the president),��served as mayor of Dakar��from 2009��until his conviction on charges of��embezzling 1.8 billion CFA��(2.8 million euros)��in 2018. While��Karim��Wade had��supporters��who rejected his jailing as politically motivated, there was a far greater outcry from the public over��Sall���s��arrest and subsequent trial. Many accused the government of��acting not on principles of good governance, but��instead��intentionally��sidelining��a chief��rival for political reasons.��In January 2019, both Wade and��Sall��were deemed ineligible to run in the presidential election, at which point��Sall��threw his support behind the former prime minister��Idrissa��Seck.��Khalifa��Sall��continues to be popular in Dakar, which could have lowered the president���s percentage, but nationwide has minimal appeal.��The��2019��election often seemed to be a referendum on��President��Macky��Sall��rather than on any particular vision for the country, a dynamic that echoed the 2012 election when��Sall��defeated��Abdoulaye��Wade.

With��Wade and��Sall, opposition candidates struggled to gain traction. However, it is important to note the historical patterns of elections in Senegal. In the 2000 and 2012 elections where incumbent presidents were defeated, both incumbents led by substantial margins after the first round, before seeing little to no gains in the run-off election. In 2000, President��Abdou��Diouf��received just over 41 percent of the vote in both rounds, while the challenger��Abdoulaye��Wade rose from 31 to 58.5 percent. In 2012, the pattern was even more stark. Incumbent��Abdoulaye��Wade received 34.8 percent in the first round, and saw a 0.6 percent drop in the run-off (albeit with��higher turnout).��Sall, on the other hand, saw his 26.6 percent in the��first round��jump to 65.8 percent.��These numbers indicate that had the opposition been able to��limit��Sall��to��under 50��percent in the first round, a run-off election��could��have led to��Sall���s��defeat.

Sall��won��majorities��in most of the country���s districts. He lost to��Seck��in��Mback��,��which contains the��Mourides�����holy city of��Touba,��and��Thi��s,��where��Seck��had served as mayor, while losing to��Sonko��in��his home��Ziguinchor��Region. Outside of these particular��geographic��bases for��Seck��and��Sonko,��Sall��comparatively��underperformed��in��and around Dakar. According to��the provisional numbers,��Sall��received 46.8% of the vote in Dakar, as compared to 25.5% for��Idrissa��Seck��and 22.2% for��Ousmane��Sonko. He also received less than a majority in��Guediawaye��and��Pikine��on��the outskirts of��Dakar. This reflects in part��growing discontent with a lack of employment opportunities and��environmental degradation.��Sall���s��lack of support is particularly notable in Dakar and��Thi��s��given that��he received��over 72 percent of the vote in each��region in��the run-off��election��of��2012.

On the other hand,��Sall���s��margins of victory in some of the outlying areas of the country seem so extreme as to almost be unbelievable.��In the districts of��Podor,��Matam, and��Kanel��along the Senegal River, over 93 percent of voters went for the president��(Sall���s��parents are from��the��Matam��region). He also ran up large margins��as well��in eastern and southern Senegal, as well as��over 80 percent in��his home area of��Fatick.

Senegal���s opposition parties will have five years to regroup now that the presidential term has officially been shortened from seven��to five��years due to a��2016��constitutional��referendum��that��the��Constitutional��Court��controversially��decided did not��apply to��Sall���s��first term. It remains to be seen whether��Khalifa��Sall��or Karim Wade will be��eligible��to run in 2024, or whether��Idrissa��Seck��will run for president for a��fourth��time.

Ousmane��Sonko, of the PASTEF��(Patriots of Senegal for Ethics, Work, and Fraternity)��party��founded in 2014,��gained traction among Senegalese youth with a more radical stance��calling for��the abolition of the West African Franc (CFA)��and moving the Senegalese economy away from foreign corporations.��The party���s anti-corruption stance was particularly popular among urban��youth who have become disaffected with��Sall���s��presidency, and saw him as part of the larger corrupt establishment that included��Khalifa��Sall��and Wade.��Sonko���s��background as a former tax collector gave him credibility in pushing back against the tax evasion practiced by many foreign corporations active in Senegal. He��proved particularly popular in the greater Dakar area,��and��finished well ahead of��Seck��in most of the��areas furthest from Dakar.��Should he choose to run, he��will be a formidable challenger in the next election.

Assuming��no political machinations like those that allowed��Abdoulaye��Wade to run for a third term in 2012,��Macky��Sall��will not be on the ballot in 2024. His Benno��Bokk��Yakaar��coalition has no clear successor, and it remains to be seen if his popularity can be transferred to future candidates.��Sall��had seven years to develop a network of supporters across the country, and the only other candidates with large political bases were deemed ineligible. The test for any future emerging candidates in Senegal will be to develop a political base outside of one���s home region and major urban centers,��building a network in towns and villages��where governing parties have tended to maintain support.��Without a sitting president on the ballot, the next election��will hopefully��focus more on a vision for the future than a referendum on the incumbent, a welcome refresher after a series of elections focused primarily on presidents��� job performance.

Five more years of President Macky Sall in Senegal

Image credit Office of the President of the Republic of Benin via Flickr (CC).

On Thursday,��Febraury��28th, Senegal���s electoral commission announced the provisional results of the country���s presidential election.��Macky��Sall��won re-election��in the first round with 58.27 percent��of the vote, eliminating the possibility of a run-off where opposition support could have coalesced around one candidate. Despite popular opposition, especially in and around the capital of Dakar,��Sall��not only received a majority of the vote, but surpassed the 55.90 percent��Abdoulaye��Wade won��during��his re-election��in 2007.��The four other candidates on the ballot��have��rejected��the results of the election, but have decided not to challenge it in front of��Senegal���s Constitutional Court.��The result��was also��confirmed by Senegal���s Constitutional Court.��Idrissa��Seck, the former prime minister and mayor of��Thi��s, finished second with 20.50 percent of the vote, followed by��Ousmane��Sonko��at 15.67 percent.��Sonko���s��showing,��particularly��among young people,��will make him a formidable challenger in the 2024 election, especially given that��Macky��Sall��will be prohibited from running again.

A rapid expansion of infrastructure has marked��Sall���s��first term, including the opening of the new Blaise��Diagne��International Airport outside of Dakar,��and more recently the inauguration of a bridge across the Gambia River to facilitate traffic��between��northern and central Senegal to the distant��Casamance��south of the Gambia. The bridge is a particularly notable accomplishment as��a multi-national challenge that has frustrated��citizens and governments��dating back to the colonial period.��Perhaps more importantly, the seven years of��Sall���s��first term have also seen the construction of new and improved roads��and other infrastructure projects��across��the country. Opposition supporters argued that��the president��focused on infrastructure, not jobs, and is leaving Senegal���s young adults behind while consolidating��the country���s economic gains��within��a narrow elite class.

Two major opposition candidates in the 2019 election were supposed to be the former mayor of Dakar,��Khalifa��Sall, and Karim Wade, the son of ex-president��Abdoulaye��Wade and a former ���super minister��� given charge of much of the government���s budget during his father���s presidency. Wade, representing his father���s Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS),��was convicted��in 2015 of��embezzling��178��million euros��during his father���s administration, a figure many suspected was an understatement.��Macky��Sall��pardoned��Wade in June 2016, after which he went into exile in Qatar.��Wade was never particular popular (he lost an election for mayor of Dakar while his father was president), but his father���s popularity would have lent him some validity that may have taken some votes away from��Sall.

Khalifa��Sall��(no relation to the president),��served as mayor of Dakar��from 2009��until his conviction on charges of��embezzling 1.8 billion CFA��(2.8 million euros)��in 2018. While��Karim��Wade had��supporters��who rejected his jailing as politically motivated, there was a far greater outcry from the public over��Sall���s��arrest and subsequent trial. Many accused the government of��acting not on principles of good governance, but��instead��intentionally��sidelining��a chief��rival for political reasons.��In January 2019, both Wade and��Sall��were deemed ineligible to run in the presidential election, at which point��Sall��threw his support behind the former prime minister��Idrissa��Seck.��Khalifa��Sall��continues to be popular in Dakar, which could have lowered the president���s percentage, but nationwide has minimal appeal.��The��2019��election often seemed to be a referendum on��President��Macky��Sall��rather than on any particular vision for the country, a dynamic that echoed the 2012 election when��Sall��defeated��Abdoulaye��Wade.

With��Wade and��Sall, opposition candidates struggled to gain traction. However, it is important to note the historical patterns of elections in Senegal. In the 2000 and 2012 elections where incumbent presidents were defeated, both incumbents led by substantial margins after the first round, before seeing little to no gains in the run-off election. In 2000, President��Abdou��Diouf��received just over 41 percent of the vote in both rounds, while the challenger��Abdoulaye��Wade rose from 31 to 58.5 percent. In 2012, the pattern was even more stark. Incumbent��Abdoulaye��Wade received 34.8 percent in the first round, and saw a 0.6 percent drop in the run-off (albeit with��higher turnout).��Sall, on the other hand, saw his 26.6 percent in the��first round��jump to 65.8 percent.��These numbers indicate that had the opposition been able to��limit��Sall��to��under 50��percent in the first round, a run-off election��could��have led to��Sall���s��defeat.

Sall��won��majorities��in most of the country���s districts. He lost to��Seck��in��Mback��,��which contains the��Mourides�����holy city of��Touba,��and��Thi��s,��where��Seck��had served as mayor, while losing to��Sonko��in��his home��Ziguinchor��Region. Outside of these particular��geographic��bases for��Seck��and��Sonko,��Sall��comparatively��underperformed��in��and around Dakar. According to��the provisional numbers,��Sall��received 46.8% of the vote in Dakar, as compared to 25.5% for��Idrissa��Seck��and 22.2% for��Ousmane��Sonko. He also received less than a majority in��Guediawaye��and��Pikine��on��the outskirts of��Dakar. This reflects in part��growing discontent with a lack of employment opportunities and��environmental degradation.��Sall���s��lack of support is particularly notable in Dakar and��Thi��s��given that��he received��over 72 percent of the vote in each��region in��the run-off��election��of��2012.

On the other hand,��Sall���s��margins of victory in some of the outlying areas of the country seem so extreme as to almost be unbelievable.��In the districts of��Podor,��Matam, and��Kanel��along the Senegal River, over 93 percent of voters went for the president��(Sall���s��parents are from��the��Matam��region). He also ran up large margins��as well��in eastern and southern Senegal, as well as��over 80 percent in��his home area of��Fatick.

Senegal���s opposition parties will have five years to regroup now that the presidential term has officially been shortened from seven��to five��years due to a��2016��constitutional��referendum��that��the��Constitutional��Court��controversially��decided did not��apply to��Sall���s��first term. It remains to be seen whether��Khalifa��Sall��or Karim Wade will be��eligible��to run in 2024, or whether��Idrissa��Seck��will run for president for a��fourth��time.

Ousmane��Sonko, of the PASTEF��(Patriots of Senegal for Ethics, Work, and Fraternity)��party��founded in 2014,��gained traction among Senegalese youth with a more radical stance��calling for��the abolition of the West African Franc (CFA)��and moving the Senegalese economy away from foreign corporations.��The party���s anti-corruption stance was particularly popular among urban��youth who have become disaffected with��Sall���s��presidency, and saw him as part of the larger corrupt establishment that included��Khalifa��Sall��and Wade.��Sonko���s��background as a former tax collector gave him credibility in pushing back against the tax evasion practiced by many foreign corporations active in Senegal. He��proved particularly popular in the greater Dakar area,��and��finished well ahead of��Seck��in most of the��areas furthest from Dakar.��Should he choose to run, he��will be a formidable challenger in the next election.

Assuming��no political machinations like those that allowed��Abdoulaye��Wade to run for a third term in 2012,��Macky��Sall��will not be on the ballot in 2024. His Benno��Bokk��Yakaar��coalition has no clear successor, and it remains to be seen if his popularity can be transferred to future candidates.��Sall��had seven years to develop a network of supporters across the country, and the only other candidates with large political bases were deemed ineligible. The test for any future emerging candidates in Senegal will be to develop a political base outside of one���s home region and major urban centers,��building a network in towns and villages��where governing parties have tended to maintain support.��Without a sitting president on the ballot, the next election��will hopefully��focus more on a vision for the future than a referendum on the incumbent, a welcome refresher after a series of elections focused primarily on presidents��� job performance.

March 11, 2019

Others made of kindness

Boarding the Likoni Ferry bound for Mombasa. Image credit Xiaojun Deng via Flickr (CC).

Another Kind of Madness, the viscous, lyrical debut by��American��poet Ed��Pavlic, moves at two different speeds at once. While the narration threads quickly and easily through the interior worlds of��Ndiya��Grayson and Shame Luther, the scenes, set alternately in beachfront Mombasa��in Kenya��and��the��South Side Chicago, unfold languorously. The book focuses on seemingly disconnected moments���babysitting twins, sleeping on a strange train, a factory without ventilation (���acid ate the teeth���)���and yet the tension between the characters�����tactile reactions and their submerged trauma burns an unexpected urgency into the story.

Shame, a laborer and son of a bricklayer, returns to Chicago after a decade of self-imposed exile. Jobs in Los Angeles and Mississippi have provided him with a bigger picture: ���The days of long jobs on newly constructed factories were, as far as he���d seen in Chicago, gone.��� Back home he spends his time at industrial gigs, minding the children of 63rd Street, and dabbling with the piano at a Northside lounge.

Ndiya��attends college in Cambridge and lives afterwards in New York City. The recent demolition of The Grave, the Chicago building where she was victimized as a child, offers her the possibility of return. Once back, however, she feels unmoored. ���The way she saw it, things in Chicago and the rest of the United States would continue to slosh about, unanchored, and …��in the end no one really had any idea of what it would mean.��� She struggles with her job, and later with the idea of work itself. When Shame introduces himself as a member of ���International Laborers��� Union, Local 269,��� she misunderstands. ���Yeah? Where���s that?��� she replies.

Shame���s building is owned by Junior, a drug dealer who knew��Ndiya��when they were children. When violence engulfs Junior and the neighborhood, Shame, with the help of a bassist named��Kima��(a nod to��novelist Peter Kimani), flees to Kenya. Eventually��Ndiya��joins him.

Major Chicago episodes, such as the murder of Fred Hampton��in December 1969, the politicization of Yvette ���Chaka Khan��� Stevens��(Chaka Khan joined the Black Panthers in her teens and befriended Hampton), the fall of kingpin Jeff Fort and the rise of the��street gang, the��Black Gangster Disciples,��make cameo appearances. The attack on��Ndiya��reverberates with��the��real-life attack on ���Girl X���,��who was��sexually assaulted��and left for dead��in the Cabrini Green��(public)��Houses��on Chicago���s South Side��in 1997:

Far as he knew, the girl lived. He forgot the name. She was shipped out of the city by sponsors and private schools… Years later they���d been this story about the girl grown, on her way to Harvard.

As the book glances these large events, it lingers longer on seemingly inconsequential ones. A spider bites a thigh, someone slices ginger, an ankle monitor slips out of a handbag���Ndiya��or Shame pull apart each incident as they replay them. Hazy word-clouds accumulate, condense, and dissipate, leaving gooey drips of information.

In the morning:

Shame���s before-work was stripped down to bed, fridge, the first forced meal of the day, the painted-pine closet full of��worksmell,��bodysmell, chemical-scented clothes hanging in there. The feel of worn cotton. Cotton was his one extravagance. It was expensive and it wore out fast. But he wouldn���t wear the polyester work clothes the old men wore. Wouldn���t do it.

And on a Mombasa beach:

Barracuda. Their heads were oversized as locomotives, Shame thought,��as he gazed down at the strangely fixed image cast by the tangle of specialized marine engineering.��Kubwa��and his brothers watched��Shame from behind��but he had no sense of that. The eyes of the fish were obsidian disks with flecks of cobalt, none of it much use, he figured, out of the water.

Some sections are narrated by a ghost of Shame���s best friend, whose death precipitated his exile. The ghost tells us that Shame is not a birth name, but the alias of Allen��Sardonovic. For Allen, ���shame��� describes a ���silent border between grief and despair.��� Some grief comes from the loss of the friend, some from a distance from his father. ���I���d call Shame���s pops��Gotta��Go and laugh. Shame didn���t laugh,��� the ghost says.

But Shame also experiences humiliation and anguish around racial (mis)identification. During a police interrogation in Chicago, a childhood memory rushes up:

The conversation he didn���t need to hear when he got up and left the table: ���Do you know, up until now, I mean at first, I thought he was white?���

Other such exchanges exhaust Shame. ���Just another roll of the same dice,��� he says. In a 2016 Boston Review��essay,��Pavlic, who shares biographical details with Shame, is more explicit:

More than once in my twenties, police asked me point blank:��Are you black or white?��In these previews of often subtler interrogations to come, it always seemed to me that the question��was��the answer. Yet for years and long after I knew better, and even up until now, I have been afraid to openly analyze the dynamics that have produced these questions. I dealt with them lyrically, both in poems and in life. But in a fearful and tiresome symmetry, this silence and lyrical angularity… also forced me to treat my condition as if it were a personal psychosis, mine and mine alone, an essential and incommunicable privacy. It���s taught me how necessary privacy is but also how an incommunicable privacy narrows, collapses, becomes a trap.

Mombasa, then, where East Africa meets the Indian Ocean, becomes, for both��Ndiya��and Shame, a place of renewal and reinvention, where people blend in, blend away, start over. Witness the symbolism in the advice they get:

Take yourself a sail. Charter a dhow. Go all the way to��Kiwayu, near Somalia���a��beautiful sandy seal on a wide-open envelope. The place is borderless.

Ndiya��begins, and struggles, in Mombasa, to tell Shame her story. He doesn���t understand what she���s talking about, but ���he knows there is no way to ask. He hopes she���ll continue. And he���s afraid.�����Ndiya��arrives at the following realization: ���We owe the world that���to live in it.���

The title of the novel is taken from the 1994 song��Miles��Blowin���, recorded by Chaka Khan. Other Khan epigraphs guide the story. Yet the ragged, passionate love that she sings out into the world���I need you, that���s another kind of madness���feels, when compared to the quiet pact��Ndiye��and Shame make, the solidarity of the lonely, of a different timbre. The profound kindness and the redemptive acceptance that the two find and build in each other is what sticks.

Ndiya, at times, feels like too many characters bundled into one: child survivor, Harvard graduate, urban drifter. And often our picture of Shame seems incomplete, leaning away from the ���necessary privacy��� towards the�����incommunicable.�����Yet this remarkable project, with its lyrical play and experimental structure, shrinks the moment between event and emotion���as well as the distance between text and experience���down to a dot.��Another Kind of Madness��is likely to grow��Pavlic���s��reputation beyond the community of poets and academics in which he is already well-known.

March 10, 2019

Eritrea’s diplomatic offensive?

Left to right: US Embassy Charge��d���Affaires��Natalie E. Brown, Ilham Omar, Eritrea���s minister of information��Yemane��Gebremeskel, Karen Bass and��Congressman��Joe��Neguse. Image via US Embassy Asmara Eritrea Facebook page.

Ilhan��Omar, the Somali-American congresswoman from Minneapolis, has��been in the headlines lately for��calling out Israel���s influence on US foreign policy��and��for��her grilling of��Donald��Trump���s Venezuela envoy, the��war criminal Elliot Abrams. Less well covered has been��her��venturing into the United States’s policy on Africa.

At the beginning of March��Omar joined a��US Congressional Committee led by Rep. Karen Bass��to��visit��Eritrea. Others in the delegation included��Eritrean-American��congressman��Joe��Neguse��of Colorado.

Karen Bass is chairperson of the US House of Representatives��Foreign��Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights and International Organizations, so this clearly was a high level affair.

That the visit happened may have been largely a consequence of changing geopolitics and conflicting interests of the superpowers in the Horn of Africa; buying time for��Eritrea���s Life-President Isaias��Afwerki��and his regime, in power for 27 years already. It is unclear who will benefit from��the visit by the US delegation: the US, the Eritreans or even Eritrea’s more powerful neighbor, Ethiopia. Afwerki���s��regime has been shunned by the US and subjected to sanctions.

We doubt that the visit will receive the kind of scrutiny Omar���s remarks about Israel have received in US media. In a��tweet, Omar described the visit as the ���the first American delegation to Eritrea in decades.�����It was the first in fourteen years.��But the US may be following its chief ally in the region, Ethiopia.

The presence of Ilhan Omar on the trip was significant. She was born in Somalia, also in the Horn, and fled to the US via a Kenyan refugee camp with her family, settling in Minneapolis as a teenager. In Omar’s short time in Congress, Omar has emerged as a leading critic of US foreign policy. But, Eritrea may prove to be something else.

During the Eritrea visit,��Omar sent out a bland��tweet��about her visit to Eritrea and expressed her gratefulness for being part of the delegation. She finished with�����I fight peace and justice because only those who experience the pain of war, know the joy of peace.���

Then her tweets returned to domestic US politics.

A number of Twitter users, including many Eritreans, reminded��Omar��of��the systemic abuses committed��by Eritrea���s government against its citizens.

As for Karen Bass, she has��bashed��President Trump for meeting with North Korea���s autocratic leader. Eritrea is often characterized as ���Africa���s North Korea.����� Some Eritreans couldn���t pass up the opportunity to remind Bass of her��double standard��for leading a delegation��to the North Korea of Africa.

Joe��Neguse, whose parents fled Eritrea in 1980, then still under Ethiopian control, also had little to say. He only added to a collective post-trip press statement signed by Bass:�����I look forward to further discussions with my colleagues and the State Department on how to further promote peace, security, human rights, and democratic reforms in the region.���

Statements by��Bass and��tweets by��Eritrean government officials,��suggested��the delegation held�����a��series of meetings,��� with senior government officials, according to��a tweet��from��the Eritrean minister of information,��Yemane��G.��Meskel.��On her way��back to the US, during a��stopover in Addis Ababa,��Ethiopia, Bass��spoke��to��the��Associated Press��about the Eritrea visit. For Bass,��Eritrea�����has been a mystery������showing little reform��since rapprochement��with Ethiopia. Yet, she hoped to see several detained US nationals including former US embassy staff to be released�����promptly, as well as other people who are incarcerated.���

So, in the absence of��independent��media��or��press conferences (especially on the Eritrea side), no one knows the outcome of��the��meetings. Eritrean state media��was quiet on the matter.��There was no mention of the meeting��apart from the minister���s tweet. (A��visit by��French��congressional��delegation��around the same time,��also received only��one-tweet��by the��information��minister.��This, in��contrast to the��relatively strong��state media��coverage of a visit by a��Russian��delegation��at the time.)

More significant has been��Afwerki���s��diplomatic��engagement with��other African states, especially Ethiopia.

On March 3,��Afwerki��met with Kenyan President,��Uhuru Kenyatta,��and��Ethiopian Prime Minister,��Abiy��Ahmed,��in what��Eritrean��state media��described��as��a�����Tripartite Summit.�����Kenyatta flew back the next day,��while��Afwerki��took Ahmed to��show��him��the dams��he had personally��supervised��during construction.��(This while��Eritrea���s��cities, including Asmara, are suffering from��a��shortage of running water,��further exacerbated��in August last year when��more than 300 water truck owners��were��rounded up and required to pay huge amounts��to be released.)

Afwerki��and Ahmed��then��flew to South Sudan and met with President Salva��Kiir��on��March 4th.��Clad in khaki attire, the newly enamored leaders, each facing mounting pressures in their respective��countries,����discussed��regional economic integration��before��addressing domestic issues.

In the fast-pace diplomatic thaw between Eritrea and Ethiopia,��the unholy��alliance��of the��leaders��is unnerving��Eritreans.��Since July 2018, when��Afwerki��made his first official visit to Ethiopia, Eritreans have been��wary of his utterances. His mercurial temperament and his grand��ambitions��make the fear legitimate. This��is��further compounded��by��the opaque nature of the regime wherein��the��majority, including��senior officials,��are��alienated. In his first speech��in Awasa, Ethiopia, President��Afwerki��stated,�����from now on,��anyone who says��Eritrea and Ethiopia��are��two��people is out of reality.�����Then he��told��Abiy�����you are our leader��� and��declared: ���I���ve given him all responsibility of leadership and power.���

Since July 2018,��Afwerki��has met with��Abiy��nine times while he has only met with his Cabinet ministers once.

But a return of US and Ethiopian influence is not the only thing ordinary Eritreans have to think about.��In August��2018��Reuters��reported that��the��UAE is planning to build��an oil��pipeline from the Eritrean port��Assab��to Addis Ababa. There��has��been��no��official��confirmation��on the��report��from the Eritrean side. ���Then in��January 2019��at the��World Economic Forum��in��Davos-Klosters, Switzerland,��Ahmed��said he doesn���t see the need to have separate armies and embassies for Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti.��A��few days later,��the official handle of Ethiopia���s Prime Minister��tweeted��that Ahmed held talks with��his��Italian counterpart and agreed to build an Addis��Ababa-Massawa railway line.��Massawa is��an��Eritrean port-city;��Eritrea���s��diaspora, fiercely nationalist,��responded��ferociously. In his attempt to��ease qualms, the Eritrean minister of information��tweeted��that the proposed railway line��was part of the ���cooperation between the��three��countries explored in previous meetings.�����It��didn���t stop there.��When��the administrator of Ethiopia���s��Oromia Region, Lemma��Megersa, was asked why Ethiopia is building a navy when it does not have��a��sea, he��replied, ���You never know, we might have access to a sea��in the future.���

During Ethiopia’s��political parties��meetings last month, Ahmed stressed Ethiopia���s unity and��assured��the audience that ���Ethiopia won���t disintegrate, but it is a matter of time that those��who have left would return.�����He��did not mention names, but it was obvious that he was implying Eritrea.

The��diaspora-based Eritrean independent media��are examining these events in retrospect.��Prominent exiled��freedom fighters have been sharing different anecdotes��that foreshadow��Afwerki���s��ambivalent stand on Eritrea���s national sovereignty. The��anxiety��is widely shared, including among��leading Eritrean intellectuals.

Bereket Habte Selassie, the��chairperson of��Eritrea���s��1997 constitution��(never implemented),��told journalist Martin Plaut,��that��with��Afwerki���s��singlehanded decisions,�����Eritrea has been offered to Ethiopia��on a silver platter.���

March 9, 2019

Africa doesn’t care about its women

Seun Babalola in Portugal. Image used with permission of author.

I remember it well. One afternoon, in an immigration office in Freetown, I applied for my Sierra Leone passport. It was difficult because the officials would not believe that my mother was my mother. The birth certificates and family photos were insufficient, my Yoruba name threw them off���my dad was born and raised in Nigeria���and they thought I was a scammer. I was exhausted from an afternoon of arguing, to say the least.

My mother, small, thin and powerful, was fed up. I���m sure, as she cast her threats, she managed to make the four grown men in the room feel like children. But her presence was only making things worse, so I pushed her out of the room and pleaded with the men.

In my (broken) Krio, I asked, ���Sir,��wetin��na��problem? Ah nor��sabi.���

He looked at me surprised and stated that we didn���t respect him enough. I calmly asked, ���What more respect do you need? We are asking you to be logical.���

As if I had flicked a switch, his demeanor spun 180 degrees. He leapt from his desk and towered over me, screaming in my face. ���Do you think this is the States? You can���t just get your way. You are a woman. I am the boss. I have you here in this room, do you know what I could do to you?���

I noticed that the other men were also standing, blocking me in a circle. I pushed them aside and darted to the door but they blocked it. I lunged for the door again they pushed me back. When the door was slightly ajar, I noticed people sitting outside so I banged on available desks, screaming, ���Let me out!��� After a scuffle, I made it out safely.

That interaction was years ago, but it was not the first nor the last time I was judged or threatened because of my gender. My name is��Seun��Babalola, I was born in New York, and raised by Sierra Leonean and Nigerian parents. I���m a filmmaker. One of my projects,�����OJU, is a documentary series made to showcase the beauty and diversity of youth culture on the continent. It���s a platform for us to speak to one another, learn from our differences, and inspire dialogues that explore identity.

After traveling to eight African countries as a one-woman crew, I have met amazing people, people who have opened up their world to me. I���ve navigated these African cities on my own, and while it was mostly positive, the negative experiences are hard to ignore. My experience with the immigration office is a tame example of what our women face on a daily basis. I have the privilege to fight, argue, or board a plane when I feel like I���ve had enough. The vast majority of women on the continent do not have that option.

I have a connection to Sierra Leone. It���s where my mother was born, it���s the culture that raised me and it���s one of the countries where I first filmed ���OJU. While rich in culture and natural resources, it has had its battles with colonialism, civil war, and disease. Its beaches can rival any Greek island, and its mountains and terrain take your breath away. Morning rush hour in Freetown is a strange one. No one is in too much of a hurry but everyone is doing something, with enough time in between to gist and say hello. As the sun sets, the city is cast in orange and the bustle of the day fades to a hum of��keke��motors and��Afrobeats��from homes scattered around town.

Image via ���OJU Facebook with permission from author.

Image via ���OJU Facebook with permission from author.My sister,��Massah��KaiKai, has lived in Sierra Leone for the past four years. She moved to Freetown in order to provide opportunities for local women in the textile industry, launching��projects like a successful collaboration with American Apparel. The t-shirt line, made of traditional Sierra Leone tie-dye, sold out. Fifty percent of the proceeds went to the women who created the designs.

In 2018,��Massah��was recommended for appointment as Executive Chair of the Small and Medium Enterprise Development Agency (SMEDA) under current President Julius��Maada��Bio.��Before she could start the position this September, she disappeared.��Massah��has been missing since August 7, 2018.

The search for my sister has placed me face-to-face with misogyny. When��speaking to local police, many began their questioning with, ���How is she successful?��� ���Was she dating married men?���

After another day of being dismissed by the local police department, our mother told me, ���I am not respected and my concerns are not addressed because I am not a man.��� The police neglected to pursue leads (to avoid taking orders from a woman) and mocked her when she demanded due process. The officers jokingly posed the question, ���What���s so special about your child?���

The disappearance gained the attention of First Lady, Fatima Bio, who informed the President and Vice-President Mohamed��Juldeh��Jalloh��via telephone. A decision was made to ���take action.��� That was on October 19, 2018. Since then, all correspondence has fallen silent.��Massah��is still missing.

When it comes to our continent, we lack variety in how Africa is presented in the media. It���s either one-note or a negative perspective. In a rush to provide an alternative, it���s easy to leave Africa���s reality on the sidelines. The reality is, we have��beauty��and we have��struggle. This reality takes time to explain and includes a nuanced understanding of history and culture. We have to take the time to understand, and be honest about what we learn. In the media and in our everyday lives, representation is important, but truth and balance are crucial.

I would be remiss as an African woman and a filmmaker with a voice to not share these experiences. It is not only in Sierra Leone, and it is not only me, my mother, or��Massah��who are affected. From the��Market March in Nigeria, to��gender inequality in Kenya,��there is ample evidence continent-wide that��this a societal problem. Ignoring it points to a lack of respect and empathy. It needs a lack of fear to consistently call it out, and an abundance of perseverance to fix it.

If you have any information about��Massah��KaiKai���s��whereabouts, please email��helpfindmassah [at] gmail.com. All messages will be kept anonymous.

March 8, 2019

A Photographer of African Liberation

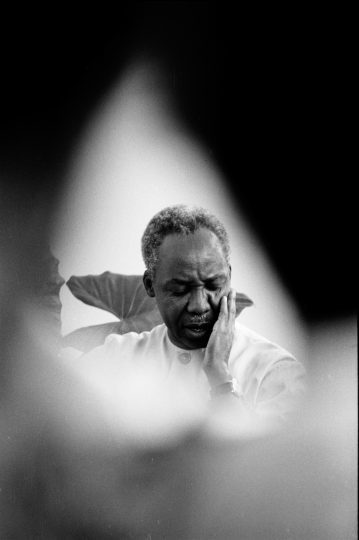

President Julius Nyerere. Dar Es Salaam, 1974. Image credit Ozier Muhammad.

During the Sixth��Pan-African Congress���a��political��gathering��launched��at the turn of the 20th��century by the theorist, writer, and activist W.E.B. DuBois���the then President of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere��closed his eyes and placed his left hand on his cheek.��Nyerere was unaware of the presence of��the��young��black��American��Ozier Muhammad,��the photographer��and��grandson of Elijah Muhammad, who��founded��the religious group The Nation of Islam. Muhammad���s trip to Tanzania, as part of the conference���s North American��delegation, marked the first of many times he traveled to the continent.

Elementary school boys at Muslim school, 1966. Image credit Ozier Muhammad.

Elementary school boys at Muslim school, 1966. Image credit Ozier Muhammad.A print of��Nyerere���s��image��was��featured alongside Muhammad���s Pulitzer Prize winning photographs of famine in Ethiopia,��and the presidential inauguration and funeral of Nelson Mandela as part of��a��recent��short-run��exhibition,�����A Life in the World: Bearing Witness with a camera from the South Side of Chicago to South Africa,�����hosted��at��The��InterChurch��Center��in New York City.

Initially��hesitant to give creative license to��the show���s curator, Frank��DeGregorie,��Muhammad��conceptualized��his��first solo��exhibition as a�����retrospective,�����an opportunity ���to look over the range of [his] working, creative, and productive life as a photojournalist.�����Until the exhibition, the majority of Muhammad���s photographs��had��appeared��in the��Chicago-based��Ebony��and��Jet��magazines��and the New York City��newspapers��Newsday��and��The New York Times, where he worked until recently.��There were��subtle��nods��in the show��to his early days as a photographer��on the streets of Chicago and his��coursework��in photography at Columbia College, where��social documentarians��Carol Evans, Jim Newbury and Archie Liberman personally introduced him to��the legendary American photographers��Robert Frank and Roy��DeCarava,��and where he learned to make silk screens and��daguerreotypes.��Despite��prioritizing his published��works, the exhibition succeeded��in��illustrating��the��historical and cultural brilliance of black American and African��life and the shared political struggles that unite black populations.

New York, NY. Image credit Ozier Muhammad (The New York Times).

New York, NY. Image credit Ozier Muhammad (The New York Times).No particular chronological, thematic or methodological frame��fused��the three-part exhibition.��The��InterChurch��Center���s��Treasure Gallery, a small room near the��westside��entrance, housed Muhammad���s photographs of Africa���his portrait of Nyerere,��along with intimate portraits of black American��pop-culture��icons, such as Lawrence Fishburne and Muhammad Ali. The hallway on the building���s southern side, closest to the Treasure Gallery���s entrance, included pictures from Muhammad���s early days as a photographer living in Chicago, where he��photographed everyday street scenes��outside of��a��homeless shelter��in conjunction with��the activities of the Nation of Islam, and of Harlem, where he currently lives. The building���s elevators and reception area obscured��the northward side hallway, which displayed scenes gathered in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the 2010��earthquake in Haiti, and Barack Obama���s��2008��campaign��for US president.��Forced to look at the exhibition in parts made it possible to see why Muhammad eschews the term ���news photographer,��� and prefers to be called ���a��photojournalist.��� In his words, he did not always cover�����news.�����In fact, when on assignment, Muhammad found himself documenting��in ���post-mortem,��� or ���catching up with breaking news.��� He likened his practice and work as a photojournalist to ���keeping visual journals.��� There was ���documentary, personal, feature, news, [and] sports.�����The same year��of these��editorial��assignments in Africa,��when��he��photographed not only Nyerere,��but also Samora Machel, then the leader of Mozambique���s liberation war against Portugal,��Muhammad photographed the famed boxer and Nation of Islam member Muhammad��Ali��as he read a poem.

Haiti 2010. Image credit Ozier Muhammad (The New York Times).

Haiti 2010. Image credit Ozier Muhammad (The New York Times).Rich visual imaginaries��of Africa���s liberation��informed black American political activism��during the��US civil��rights��movement. The photographic image of black African and Caribbean liberation heroes,��such as��Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, and Michael Manley, were fixture���s in Muhammad���s childhood home, where the African-American-owned newspapers��The Chicago Defender��and��Pittsburg Courier,��and magazines��Ebony��and��Jet��circulated frequently. Muhammad��recalled the pain experienced by members of his community upon learning��of��the��Lumumba���s death in 1961. ���We grieved as if he [Lumumba] was our leader.�����Tied to this imagery��and his own family collection of news clippings, Muhammad became��attuned to��the��American��media���s��fascination with the Nation of Islam��and the ���great photography��� that accompanied reporting.

Muhammad Ali recites poem, 1974. Image credit Ozier Muhammad

Muhammad Ali recites poem, 1974. Image credit Ozier MuhammadMuhammad���s vein of news photography��in the 1970s and 1980s��differed from African-based��photographers,��including the Kenyan Priya��Ramrakha��and the South African David Goldblatt, who published features in the well-known American publication��Life��magazine. Muhammad worked for the��cash flushed��Johnson Publishing Company, the owner of��Ebony��and��Jet��magazines. Unlike its competitors, Johnson Publishing Company used its��sales profits to support��Muhammad���s first trips to the continent, and��to��create an informal yet highly��productive wire-service that rivaled��Life���s, the��Associated Press���s, and��Agence��France Presse���s��Africa coverage.��Muhammad��resists identifying��himself as the only��African American photographer��in such a position. In fact, he and the black American female photographer Marilyn Nance documented the Second World Black and��African��Festival of Arts and Culture in Nigeria��(FESTAC) in 1977.��An extensive network of black print news journalists,��including��Lerone��Bennett��Jr., John Johnson,��and��Gerold Boyd,��published Muhammad���s images��without��backlash, including��potentially more��gruesome and violating ones��of��famine in Ethiopia,��for which he shared the 1985 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. The��black newsrooms where Muhammad worked prioritized news coverage of Africa.��Years after he won the Pulitzer, Muhammad��noted��particular journalistic concern for what he called ���misery photography��� with the��controversy��that surfaced around Pulitzer-prize photographer Kevin Carter���s picture of the child and vulture in Sudan.

Nelson Mandela in NYC, 1990. Image credit Ozier Muhammad.

Nelson Mandela in NYC, 1990. Image credit Ozier Muhammad.Muhammad���s photographs��reflect a��willingness��to focus on the background:��he��stood��behind or next to his subjects, to consider what they saw��on the streets of Harlem,��or while traveling on the train to Mandela���s inauguration;��and he photographed��moments when his sitters looked��at and��looked��away from the camera.��The African continent is not Muhammad���s muse.��Muhammad��does��not seek to criticize the failures of African liberation.��Instead, he celebrates these aspirations for the expressive possibilities they presented many black Americans��and the complex networks of cultural and political solidarities that black communities cultivated through photography. He��freely documents��the vulnerabilities that black populations continue to face��in the wake of��natural disasters.

When I asked him what kind of photographer he wants to be thought of, Muhammad responded, ���as a race man… I was a person concerned about the African race. In a nutshell, in the best sense of the term, I would be thought of [as such].���

March 7, 2019

South Africa’s Third Way revival

President Cyril Ramaphosa addresses Black Business Council Gala Dinner. Image credit GCIS via Flickr (CC).

South African president Cyril Ramaphosa will remain president after the May 2019 election. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) can rely on its strong base of mostly rural, working class voters to ensure victory, the only question being by what margin. The flattening of South Africa���s labor movement, starting under former president Thabo Mbeki and��graduating��to the violent repression of the Marikana massacre in August 2012, has seen the main sources of political agitation become university students, the NGO sector and big business. In spite of and because of the dramatic failure that was the previous Jacob Zuma presidency, many view Ramaphosa with modest warmth, finding attractive precisely that which makes him pernicious:��his reputation as a businesslike, rational pragmatist.

Interpreting Zuma���s presidency (2009 to 2017) through an ideological prism (he projected himself as opposed to ���white monopoly capitalism���) is giving him too much credit. His actions were governed by personal enrichment, and sustained by reconciling his power and popularity. So widespread was the corruption and mismanagement that the country now stumbles through an extraordinary amount of��commissions of inquiry, trying to make sense of what went wrong. With news cycles still dominated by fresh revelations detailing the involvement of high ranking officials in the country���s looting, what was once a mood of righteous indignation has fizzled out to a general��ennui.

If Zuma was the paragon of corruption, Ramaphosa���s rise came by embodying himself as anti-corruption. It remains to be seen whether or not he���ll be able to overturn whatever corruption persists while holding whoever takes part liable. The predictable criticisms focus on how his efforts to do so have thus far been lackluster, while those defending him point out��the awkwardness of acting ruthlessly when lacking electoral legitimacy, which they claim he���ll get in May.

This vindication reflects the popular sentiment that although he hasn���t accomplished much in the transition to a new regime, what Ramaphosa has to offer will be noticeable afterwards. Much of South Africa���s faith in Ramaphosa comes from the trauma of Zuma and the desperation for anything that��seems��to be different. We are in the doldrums of low expectations, which when combined with our historical tendency to idolize political leaders, renders personality the chief factor for political change.

What makes Ramaphosa charming, is less the substance of what he has to bring to the table, and more the��method��by which he brings it. Ramaphosa operates with technocratic authority and the air of a problem-solver. His business success supposedly serves as self-evident proof. Combine that with his background as first a trade-union advisor during apartheid and then a negotiator in ending it (he oversaw the drawing up of the new Constitution) completes the profile of a man adept at finding tough solutions for tough problems.

Assessing his State of the Nation address, the South African journalist Ferial��Haffajee��called��him, ���…a nerd and a workaholic in the style of former US president Barack Obama.��� And much like Obama following the 2008 financial crisis, so for Ramaphosa���in the midst of a policy climate raising demanding action around��land reform��and the state of��public enterprises���a defensive narrative has sprung out presenting Ramaphosa as a man faced with making unpopular but urgent compromises while having the will to make them with sound deliberation and analytical rigor.

Ramaphosa���s posturing is that of rising above the ideological, and zoning in towards the practical; the suggestion being that the two are difficult to reconcile. His approach resembles the now discredited Third Way politics of the 1990s, associated with Bill Clinton and the New Democrats, Tony Blair and New��Labour���s��Third Way in the UK, and copied elsewhere by governments. At the heart of Third Way politics is centrism that views itself as post-political, able to harmonize different political orientations in the pursuit of the irrefutable, objective good that is policy moderation.

As far as indicating a substantive value commitment, Third Way centrism is vacuous. It is, however, obsessed with process, which if followed rationally and with care to ensure accountability, transparency, and good governance, will yield good outcomes. What it���s actually served to do, was to naturalize policies which��are��ideological, rooted in neoliberalism and faith in the free-market. It did so by marrying center-right economic tendencies with some, progressive social justice initiatives (mostly around identity), but never far enough that they could be considered actually egalitarian or redistributive.

The Third Way leans left to obfuscate the fact that it stands right, and talks loftily of procedure and deliberation to assert that it��is��right.

Considering this, Ramaphosa���s policy direction will likely be a continuation of the Mbeki years, swinging in favor of deregulation, liberalization and privatization. The government under Ramaphosa is already getting ready to implement structural adjustment programs to the satisfaction of the��World Bank and IMF,��with a particular focus on restructuring state owned enterprises and opening up to��multinational��mega projects. (His finance minister��said as much��during the recent Budget Speech.) With his close ties to numerous South African��business elites,��the intention is clearly, as its always been, to appease domestic and global finance capital.

What distinguishes Ramaphosa from Mbeki is a stronger effort to involve and triangulate,�� preemptively placating those angling for a radical vision. While Ramaphosa talks left on��land reform, the Department of Mineral Resources led by Minister��Gwede��Mantashe��continues to override the interests of��indigenous communities��in��favor of international mining companies. Ramaphosa���s talk of ���inclusive growth��� merely refers to a��neo-corporatist,��big tent style of politics that sees��summit��after summit where the left may have a seat at the table, but won���t have a signature on the final policy document.

This turn contrasts starkly with the rest of the world, where radical programs are finding mainstream resonance again. In the Anglophone powers where ���there is no alternative��� once reigned, policies such as a Green New Deal, free universal healthcare, a living wage and universal basic income are firmly on the national agenda. They are spearheaded by hard-working, self-described democratic socialists like Jeremy Corbyn, who���s rapidly restored the��Labour��Party���s popularity in the UK, Alexandria-Ocasio Cortez, the young congresswoman from New York driving the conversation on climate change internationally, and above all Bernie Sanders, who recently announced his candidacy for the US presidency, raising $6 million in individual donations within 24 hours of making the announcement. (His closest rival for the Democratic Party nomination, Elizabeth Warren,��raised only $300,000��on her first day as a candidate.)

In South Africa, the closest thing to a popular left movement with electoral viability has only increased Ramaphosa���s appeal. The black nationalist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) spent the majority of their existence since inception fighting Jacob Zuma���s corrupt presidency (amazingly, allying with the center-right Democratic Alliance to do so), and neglected building a strong, working class base in both rural and urban South Africa. Since Zuma���s departure, the party finds itself fighting for relevance, and is faltering. Now regularly embroiled in its own corruption scandals, the EFF���s lead figures are often found devolving into��hysterics��aimed at those who speak critically of them. Where their brash brand of politics was once useful, it now just makes Ramaphosa look all the more level-headed, measured and in control.

A credible alternative seriously capable of addressing South Africa���s economic crisis in the short to medium term is almost non-existent. Still, the country continues to be in the throes of outrageous��inequality. 30 million people, which is 55% of the population, earn less than $82 per month. Meanwhile, the top 10% of income earners received two thirds of national income in 2014. While white South Africans dominate the top earners at 49%, the face of chronic poverty in South Africa is black���only 30% of black South Africans, who outnumber whites eight to one, are among the top earners.

To drive home the extent of the disparity, any South African earning an��income��of more than $1,366 per month falls in the top 2% of income earners. To most, that is both disturbing and perplexing, because inasmuch as they might earn a��relatively��high income on the continent, most South Africans are financially constrained by wage and salary stagnation, debt-driven consumption, and burdened by financial commitments to extended family members. Many in South Africa���s middle class are a paycheck short from financial catastrophe.

The depths of the misery and destitution faced by the majority makes our political landscape laughable when considering how��void of ideology��it is. To be sure, advocating the presence of ideology also means that whoever responsible for seeing it through, should do so pragmatically and efficiently. Our conundrum appears to be that those with somewhat of an ideology can���t be trusted to run the country well, and those who could run the country well are sympathetic to an ideology that serves the few and not the many. Neither, are helpful for addressing the crisis.

South Africa���s future looks bleak if current political trends continue. We can no longer pretend that all it takes to address our persistent and deep-seated problems is better management of government. Our next president might be a billionaire businessman, but our country isn���t a business. History has shown that even if government operates effectively, as long as it is still tethered to the interests of the investor and ownership class, all managerial efficiency does is aid their accumulation.

In the middle of the short-lived grassroots movements like #FeesMustFall, many South Africans, especially young South Africans, came to accept that the causes of widespread poverty and inequality are structural.

Well, that structure has a name, and it���s time we fought it earnestly.

March 6, 2019

Revolutionary political thought in South Sudan

[image error]

Bentiu, South Sudan, August, 2014. Image credit JC McIlwaine via UN Photo Flickr (CC).

In 2011, South Sudan celebrated its secession from Sudan as a triumph of both “bullets and ballots,” invoking��Malcolm��X���s call to action in 1964. There is little sense of a revolutionary politics today. Instead, a dominant (bleak,��neopatrimonial) analysis of South Sudan describes divided and defensive ethno-local communities manipulated by exploitative and greedy military elites in a battle for control of the oil tap. There is a��common idea that there was little emotional content or intellectual substance to South Sudan���s national independence beyond a reactionary resistance to generations of violent colonization.

But this neglects the rich and diverse history of South Sudanese people���s political cultures and projects during the last three civil wars since the 1960s. In Sudan���s capital Khartoum of the 1980s and 1990s, a population of about two million displaced southern and Darfuri residents constructed impoverished but dynamic black suburbs, in which people of all backgrounds engaged in a rich conversation about what Sudanese independence, self-determination, and political community could look like. Men and women of various socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds invested in constructing schools and social centers, rewriting curricula and books, organizing language schools and adult education classes, writing groups, poetry competitions, drama and song groups, and publishing pamphlets and cassettes, graduation certificates and new textbooks.

This political educational work involved extensive rewriting and rethinking of forms of community and collective history in Sudan. Many men (and some women) focused on writing southern and black Sudanese people into longer and wider African histories, including recording their own subaltern history of experience in the civil wars. This history writing was so important that a research methodologies section is included in a self-made vernacular primary school textbook (in Primary 4 Reader, p. 7). This body of work cites everything from��Charles��Dickens’��Tale of Two Cities, to Holt and Daly’s textbook��A History of Sudan, and���more commonly���songs, texts, curriculum books, quotations and political speeches, including the speeches of Malcolm X.

The men and��women involved in these projects reworked and reframed the political discussions they had in terms of wider black struggles, the position of black people and Africans in the world, critiquing securitized states and the idea of borders, and the wider��neoliberal economy of individualizing wealth, inequalities, and vertical hierarchies of patronage and exclusion. Not being able to place yourself in this wider��historical and political context was explicitly criticized in these texts, even if this knowledge was traumatic; as a Dinka song Rinydan Junub (���This southern generation���) written in Khartoum in the 1990s says, “being always annoyed makes you a man.”

Through the 1990s and 2000s in Khartoum, people from across the southern and western borderlands of��Sudan set out competing (and often incomplete) ideas of what black and/or southern Sudanese futures might and should be. These projects and discussions were part of a brokering of the limits of practical political affiliation���broadly between ideas of specific regional southern self-rule, with the territorial borderlines and parochialisms that this demanded; broader ideas of black Sudanese nationalism, which necessitated a definition of who was included as a legitimate Sudani; and possibly more inclusive or radical ideas of pan-Africanism and communist futures beyond the nation-state.��This debate was centered on how to create this conscious and collective Sudani community in practice���and in what shape, and with what exclusions.

This contemporary history��evidences��a far wider intellectual culture in conflict than��the��dominant narrative��of South Sudan’s civil wars and national�����birth�����in 2011 allow. These��old radical��ideas, projects and people still hold significant power, as songs, books and individual intellectuals’ old work are cited on message boards and passed as MP3s and re-photocopied pamphlets. Most of the surviving songwriters and poets and playwrights and teachers I have met are still working. Their work,��and the possibilities held in these intellectual cultures, are missing from current discussions around reconciliation and national dialogues. But these older projects of political thought and education might contain useful weight and substance in the��continuing and fundamental��conversation in South Sudan on what was being fought for, and what political community should and can be built on this history.

March 5, 2019

France no longer has an excuse to hold on to African cultural heritage

19th Century Dahomey statues at the Royal Palace of Abomey that France is returning to Benin. Image credit Jean-Pierre Dalb��ra via Flickr (CC).

On Thursday, December 6, 2018,��Senegal���s president��Macky��Sall��inaugurated��the Museum of Black Civilizations��(Mus��e��des��civilisations��noires)��in Dakar, the culmination of a half-century-old dream by Senegal���s first President Leopold��Sedar��Senghor.��The museum, directed by Hamady��Bocoum, the former head of the��Institut��Fondamental��d���Afrique��Noire��in Dakar, features space for as��many��as 18,000 exhibits.

The goal of the museum is to demonstrate the cultural heritage of Africa and Africans, intentionally defined to include diasporic communities��globally.��For those interested in seeing parts of the museum,��Le Monde��has��a two-minute ���guided tour��� of the museum (and the BBC has a series of photos in��its article��on the museum���s opening).

Though the museum���s construction began in 2011, it opened after a year of intense public discussion and debate about the return of African cultural heritage to the continent. In a speech in Ouagadougou in November 2017, French president Emmanuel Macron��declared��that items from France���s former African colonies should be returned to those countries. This March, Macron reiterated his pledge,��announcing��the appointment of��Felwine��Sarr��and��B��n��dicte��Savoy to investigate the process for repatriating artifacts held in French museums.

In late November,��Sarr��and Savoy delivered��their report. The report recommends that objects taken without consent be returned permanently to their countries of origin, but only if those countries ask for them (an interview in French with��Sarr��and Savoy on the report can be viewed��here). The report estimates at least 88,000 objects from sub-Saharan Africa in French museums, with about 70,000 of these held in the��Quai��Branly. The day the report was delivered, Macron��agreed to return 26 items to Benin��taken by the French military in 1892, an important first step, but a drop in the bucket compared to France���s total holdings. So far, Macron���s promises are little more than empty gestures.

St��phane Martin, the head of the Quai��Branly,��came out against restitution��because it ���puts historical reparations over the contributions museums make.��� He complained that the report painted all items acquired during the colonial period ���with the impurity of the colonial crime,��� even if those items had been acquired legally. How Martin intends to define the legality of a given acquisition was left unanswered.