Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 230

February 26, 2019

A planetary humanism made to the measure of the world

Speaker's Corner, Hyde Park. Image credit Hugh Hill via Flickr (CC).

Paul Gilroy is one of the most formidable cultural and social theorists of our time. The son of the Guyanese-born novelist Beryl Gilroy, Gilroy grew up in London���s East End, and studied at the Centre For Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) at the University of Birmingham under the supervision of the late Cultural Studies doyen Stuart Hall (1932-2014).

Gilroy���s breakthrough work was There Ain���t No Black In The Union Jack, first published in 1987. He is also known for works such as The Black Atlantic: modernity and double consciousness (1993), Against Race: imagining political culture beyond the color line (2000) and After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture (2004). Gilroy���s work speaks to practically anyone interested in the vexed questions relating to “race,” racism and nationalism in our time, and offers a trenchant multi-pronged critique of various forms of essentialism from the point of view of an engaged postcolonial scholar long committed to anti-racism and anti-colonialism and the furthering of multicultural cultures of conviviality. It was with this in mind that I decided to invite Paul Gilroy to my “Anthropology of our times” series in public anthropology at the House of Literature in Oslo, Norway on April 17th 2018.

A transcript version of the public conversation I had with Gilroy about his life, work and influences in front of a packed hall at the House of Literature in Oslo on that day has now been made available in an open access version by the journal Cultural Studies.

On conviviality:

For much of my early life that was a question that was put to me a lot, actually. ���Where are you from? You can���t be from here!��� And I suppose in a way, the history of my responses, my evolving responses to that question can be retrospectively made into a narrative that explains my work���[���]��� London didn���t just become a heteroglot cosmopolitan place recently. I mean in the flats where I grew up���you know���upstairs from us were Jamaicans and Indians, my best friend as a young child was a boy whose mother was French and his father was Algerian and they had come to live in London to get away from the situation in France. The people who lived opposite were Jews, and there were Sikhs and Cypriots. I am really formed by that mix. I am formed by that version of a rich, urban culture in which local, white English life is only one element. In my work I have called it a convivial culture, which is not the same thing as a multicultural [one]. It is a convivial culture. In other words, very complicated forms of interdependence exist where one set of habits flows into others and all of them are altered by that encounter.

On the Caribbean and black studies:

When thinking about the making of our modern world it is essential to understand��� that the Caribbean was a kind of experiment. It is an unprecedented historical experiment in the making of social and economic and political life. Anyone who wants to understand the history of our modernity has to know that history. CLR James said as much in his beautiful essay Black Studies and the Contemporary Student from 1969. He says that he loved black studies only as long as it was a way of teaching an alternative history of the world, of western civilization.

On James, Glissant and Hall:

What they showed me was that it was possible to be a black intellectual. Which is a kind of impossible condition. In the way that modern racism works, blackness is the body and whiteness is the mind.

On Fanon:

For me Fanon, like C��saire actually, is a great humanist. A planetary humanist is what he is. C��saire says ���We must make a humanism made to the measure of the world, right?… I would say that there are two things about Fanon that his many American readers have failed to really grasp��� One is that he was a doctor. He had a doctor���s mentality: he wanted to heal���actually. In Fanon every argument about violence, every single comment on violence is framed or qualified by an argument about healing. And the other thing��� he was also a soldier. So in Fanon we have someone who combines the figures of the doctor and the soldier. The taker of life, and the saver of life. You can���t comprehend him without that pairing.

On new racism:

The context of that book [There Ain���t No Black In The Union Jack]��� was the emergence of what a number of us had begun to call a new racism. By calling it a new racism we were drawing attention to the fact that it was strongly culturalist in character, and that it articulated nationalism and racism very tightly together��� I felt that the starting point for any critique of the racism that I was most familiar with was a very close connection with nationalism. That association was accomplished through a particular sense of what culture could be, which had acquired all the force of an earlier biologically-orientated racism. But the new racism didn���t announce itself as a biological racism. It made culture into the favoured battleground.

On anti-racism:

There are some people���rightly or wrongly���who want anti-racism to be a critical project only. They want to be able to say what is wrong with the world and to show how those wrongs might be challenged, undone��� However, I don���t think that is enough, and I think we do that work better���we do it much better���if we have an idea of the world we want to make. And that might be difficult but it could not be avoided.

The full interview can be accessed here.

February 25, 2019

The ways in which movement can and cannot heal

Fallen Ships, Nouadhibou. Image credit Emmanuel Iduma.

There is a scene in��A Stranger���s Pose,��Emmanuel��Iduma���s��new nonfiction book, when he wanders the Moroccan city, Rabat, with a companion who offers to, ���show you how Nigerians live here.�����Iduma��finds himself in a crowded house, where people, drinks and drugs are for sale. ���I was trying to make it to Europe,��� says��Iduma���s��host later as they walk home. ���But then I came to Rabat.���

From the time he was 22 to 26,��Iduma��traveled to 20 African cities, the majority in West Africa. Some of��Iduma���s��trips occurred during the years he participated��in Invisible Borders, a project that funded African artists to travel across the continent and document their experience. Others��Iduma��took on his own.

As we follow��Iduma��through his travels, we are briefly transported to new communities. Letters, stories, poems and images surface within the broader text, often making connections between previous eras and people. There are images by African photographers, from Burkina Faso���s��Siaka��S.��Traor����to Ethiopia���s��Michael��Tsegaye, including portraits in which��Iduma��shyly poses.

Iduma��sometimes omits certain details���names, locations and mode of transport. The result is, at times, intentionally disorienting. But��Iduma���s��lyrical prose and curiosity allow for delicious submersion. The result is a journey through emotion, thought and place that is not restricted to specific countries. It is also a personal meditation on transience and grief; the ways in which movement can and cannot heal.

I met��Iduma��on a crisp October afternoon at an empty coffee shop in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, right before the US launch of his book.��We talked about his lifelong fascination with photography, the politics of travel and why home remains an elusive concept.

Today across Africa, borders are becoming more, not less, militarized. In the name of stopping migration and counter-terrorism, European countries are funding biometric technology, border guards and training police.��Few African governments have resisted. In the book,��Iduma��meets people on the move to Europe and understands that already he is traversing through a different reality: he will never know what it is like to undertake those crossings. ���The ocean is the world, without partition or division, only depth and expanse,��� writes��Iduma. ���The opacity of the sea is therefore its rich, dangerous promise. Some will drown, and some will reach��harbour.���

Yet A Stranger���s Pose remains a powerful testament to the possibilities that result from human movement.

(The following has been condensed and edited for clarity).

Caitlin L Chandler

This book can be read as a process of becoming; as an artist, a writer and a person. How did your travels shape you?

Emmanuel Iduma

I came to the end of the book feeling that I had articulated something for myself as a human being, which was the notion of what it means to be a stranger. I felt that I had material for a book that is not just about travel but is more about the process of discovery.

Caitlin L Chandler

Throughout the book, you detail several brief relationships, but not lasting connections. In which way do you feel travel brings you closer to people, but also farther away?

Emmanuel Iduma

It became clear to me from the start that I couldn���t form lasting relationships [while traveling] and that wasn���t the point. And this is what informed the entire preoccupation of the book���the notion of estrangement.

But how do you stay within that moment of being a stranger and still feel some kind of genuine interaction? Maybe that���s exactly why it���s a travel book because that���s what the genre requires or expects from the writer���to write about experiences or encounters that are always going to be brief and, in that sense, complete.

Caitlin L Chandler

Do you think that���s always the nature of being a traveler, or is that also a choice? At what point would it be possible to cross this threshold from the stranger passing through to being part of a place or community?

Emmanuel Iduma

I think it���s at that moment that one defines home. For me that���s still something I���m trying to figure out, because I live in this country [the US] and it���s just a mess and I���m constantly asking myself, how much longer will I be here? What does it mean to keep being away from Nigeria, away from my family?

Caitlin L Chandler

Does NYC feel like home to you?

Emmanuel Iduma

I would say no and that���s being really brutally honest. Especially because I���m not American, I always recognize that anything can happen���your visa could be rejected���you might never get permanent residency or become a citizen.��So��in that very��bureaucratic��sense, just the knowledge that my status is “provincial” is enough to make me not feel settled. [When I came], I only knew I wanted to do my MFA, and everything was finding my way in the dark and trying to insist that a writing life was possible; I���m sure you know that struggle.

Caitlin L Chandler

It���s very lonely���you���re creating something that does not exist and no one���s really there to guide you or to tell you it���s going to be okay.

Emmanuel Iduma

Or tell you, this is how you do it. I trained as a lawyer. I���ve done some curatorial work. I feel it���s difficult for people to place me. It���s either that you���re talked about as an academic, or as a scholar, and that���s very far from my interest.

I didn���t think I was writing a travel book until I was almost done. I was just recounting experience. But what is a travel narrative?

Caitlin L Chandler

Unlike other travel narratives, you don���t often give names or places.

Emmanuel Iduma

Well that was important to me, that anonymity was a device for storytelling.

I was also thinking a lot about Yvonne��Owuor���s��essay in the��Pilgrimages��project that Chimurenga did in 2010 when they sent a number of writers to different parts of Africa during the World Cup to write short pieces. It was very much conceived of as a travel writing project. Yvonne���s essay was important to me because I could see that she immediately went to the lyrical���she basically went in search of music and in search of silence.

Caitlin L Chandler

In the book your travels seem almost borderless, but then you juxtapose that with the stories of someone who went to Libya, or to Europe���how did you reconcile your freedom of movement with those who have none?

Emmanuel Iduma

Around the time I was traveling, migration became a central question. Because I tend to shy away from the obvious, I wanted to find a way to write about migration and the perils of crossing to Europe without making the book about that. How do you make this part of a larger question? The question of itinerancy; the question of the freedom to move or the constraints; or the very important distinction between living in a tent and living in a house made of walls?

I have some limitation attached to my movement because I have a Nigerian passport, but not to the same degree of severity as someone who doesn���t have a passport at all. I had traveled as an artist���and there���s no greater privilege than that. Even though we had a lot of challenges on the way, we had passports and funding; we were invited to places. Even if you don���t know people in a place, you have equipment that immediately identifies you as someone with access.

It was important to admit that right away, and also important to explain or convey how my experience paled in comparison to those I had met on the road.

There was this guy I met who said, ���the sea is the only way.��� And I thought, that���s the only thing I should write.

Caitlin L Chandler

I think of it as worlds within worlds.

Emmanuel Iduma

I think so, and I think it���s important that the project finds a way to allude to that���it���s always an allusion, in place of the main thing���the shadow not the substance. And I���m fine with that, with describing the in between.

In other travel writing, there is this attempt to say, because I spent time there and did research and work, I can say something that is whole. But I [felt] I could only write about these [places] in fragments.

Caitlin L Chandler

Why the enduring fascination and admiration of photography?

Emmanuel Iduma

I think its memory. The fact that photographs are indexical���they refer in a very clear sense to what has been. A good photograph is difficult to forget. There���s a good��quote��from Audre Lorde:

However��the image enters

its force remains within

my eyes.

Caitlin L Chandler

You don���t reveal a lot about yourself in the book. Why not?

Emmanuel Iduma

I use the��i!

Caitlin L Chandler

But not very often. We get observations of yourself���or of your emotional state���but only in a particular moment.

Emmanuel Iduma

I believe that my life is only interesting if it connects to the lives of others.��So��my sense is how can I use the logic of the��I, but also propose something a little bit���I don���t want to say universal���but larger.

Caitlin L Chandler

When did you know that you wanted to be a writer?

Emmanuel Iduma

When I was six. I think it���s just one of those things I can never have an explanation for���it���s just what your life will be about. I don���t remember a time as a kid that I wasn���t either writing something or thinking about writing something or trying to plagiarize something I was reading.

Caitlin L Chandler

You��wrote��once in an essay that desire is sanctioned by loss. What did you mean?

Emmanuel Iduma

I���m becoming more aware about how all of my writing is in some way an attempt to understand loss, so my thinking then was how can I connect the desire for people you love, or are in love with, to the knowledge that you will lose them one way or another.

And I wanted to find a way to say that it is loss that makes it possible for desire to exist. If I didn���t lose people, I wouldn���t know what it means to desire them.

Caitlin L Chandler

How do you feel about the book coming out?

Emmanuel Iduma

I���m proud of it because it���s the most intentional thing I���ve done. I���m curious how it will be talked about, how it will be received.

February 24, 2019

The film festival film

Image credit Old Location Films End Street Africa, 2019.

Shit got real at the debut screening of��the��exciting short film,��Film Festival Film��at the 69th��Berlinale. The South African short film follows��Fanon���played by��Lindiwe��Matshikiza���trying to shop her film at the Durban International Film Festival, one of South Africa���s two major��industry events.��At the end of the screening,��during the question and answer��session�� Fanon��was��invited to��talk about her role in the film by��Mpumelelo��Mcata,��one of the��film��directors.��Fanon��instead��turned��to��Mcata��and��co-director��Perivi��Katjavivi��and��pointedly asked, “how do you feel��as two black male directors taking all the credit for a film��that is essentially��about my struggle?” Flipping the script��on��the��post-screening��epilogue,��Fanon��cut to the chase��about��stuff��at the heart of this��quirky,��surprising short film.

The film sets��Fanon���s��agonising attempt to��pull together a film pitch.��We see her rehearsing the plot of her��somewhat��ridiculous film��about the tragic death of��Marike��de Klerk, the former wife of��the last apartheid president��F.W de Klerk. She was��brutally murdered in 2001��by a security guard working at her beach-side apartment complex. During his time as president F.W de��Klerk cultivated an image similar to Gorbachev in the West, as a ���great reformer,��� while��Marike, who��he��divorced while negotiating with Nelson Mandela,��struggled to adjust to her new life.

The film��shuttles between the claustrophobic,��yet atmospheric��setting of��her tiny hotel room where she��is��heard��constantly running through��her��pitch��and the bright,��kitsch��rooms of the Sun Coast Casino resort where the film festival��takes place.��Her performance��well��captures��the fraught struggle��of a young��black��female��filmmaker trying to hustle in a business where the odds are stacked against her.

Film finance and race are two major themes that the��crew seem to want to comment on, but they do so in playful, ironic ways.��For example, early on��Fanon announces that it is��considered��normal that white��directors��package and sell��black stories��while��she does not get the same treatment. This is an odd narrative reversal: a young black woman complains that her script about��the death of a white��Afrikaner��politician���s wife��is not attracting funding. It is as comically biting as it is��bitter.

Documentary and film��genres��are spliced��together unevenly throughout the piece.��The crew��includes��scenes where filming is intruded upon by folks just wanting to say hi��at the festival,��and the��use of��interviews and backstage scenes that include��Matshikiza,��seemingly out of character, candidly��commenting on��how she feels about performing.��Blurring reality and fiction only helps deepen��its��mischeivous��questioning of the film��business.��This��is the product of��some sharp craft��in��plotting and cutting,��however haphazard��the crew��wish to make it seem.

At the screening, the��directors��looked��at a loss for words when confronted by��Fanon��in the��question and answer session. They tried to��dodge her��question and sidestep the��volley of��follow-ups��from��women��in the��audience��who wanted to��know about��authorship, power and positioning. All the while members of the crew��in the audience��recorded��sound and footage��as the��robust��discussion��unfolded. The recordings could have��been for posterity.

But��then this is the��Film Festival Film,��a film about��a film festival��that was just��a side-project��that,��the directors��admitted,��was��never��intended to��make it to Berlin.��It could just be another punchline in what is already a��fascinating mockery of the��contemporary film industry.

By provoking this kind of��lively��discussion��in Berlin��you could say the crew��were��taking a gamble,��staking their audience���s faith��in the integrity of the film on the greater goal of��asking big��questions about��the business of film making today. Indeed, if anything,��this is��Film Festival Film���s��real strength, that it makes you wonder where��critique begins and filming��ends.��It is a troubling proposition that��makes you feel��unsettled, unsure, and gets people talking.��But then,��isn���t that��what all good works of cinema are meant to do?

February 23, 2019

The contradictions of Africa-China in Guangzhou

[image error]

Image credit Jose Pereira via Flickr (CC).

Guangzhou, in Southern China, hosts the largest community in China of people from the African continent. Migrants from��Sub-Saharan Africa, collectively referred to as ���Africans in Guangzhou,�����have been attracting��attention��due to their ���visibility,��� and the ���exoticism��� they bring to the city relative to the rest of the country. Their��presence��creates��a sort of contact zone;��a manifestation of the much-talked-about Afro-Chinese modern encounter.

For would be migrants, the idea of a thriving economy, cheap consumer goods, and a vast market lead many to perceive it as newfound destination full of opportunities and expectations.��So, those with sufficient financial means seek out established networks of (oft-legally dubious) migration agents and other contacts.��The problem, however, is that China is not really��an immigration country, and upon arrival, these dreams are tested against an unavoidable harsh reality. The��2016��documentary film,�����Guangzhou Dream Factory,�����sums this situation up neatly.

Also emblematic is the experience of one of my informants in the city. Richard, 29, is a Guinea-born Togolese who gave up his university education more than two years ago to venture to China. As the first born, he decided it was time he “took charge” of the expanding family. To do so, he needed to ���achieve something.�����After trying and failing elsewhere many times, China came calling. In searching for a way, he found a network that arranged a tourist visa and a guaranteed job in a-textile-company in Guangzhou��for him. He would work there for as long as he wished, save some money, get to know the business environment, and eventually start his own. With all these attractive promises Richard did not hesitate in spending what little he had been saving to pay for the ���formalities��� to get to China.

Once in Guangzhou, however, Richard would find no one as a contact-point. Naturally, optimism gave way to mounting doubts, hope to despair, and confidence to helplessness: ���I found myself stuck here (in Guangzhou) as I couldn���t even earn enough to go��back home. It wasn���t a matter of choice, but a lack of possibilities. All my big plans and big dreams had to vanish into the thin air. Coming to China became a one way entry with no exit.��� After staying illegally in the city and��hiding from the police for about half of a year, Richard managed (with a combination of good luck and diligence) to find an exit. He would eventually��secure��a short-term work-visa.

Many migrants have had similar experiences to Richard’s, but are determined to stay in the country at whatever cost. This means overstaying their visas and becoming illegal residents for some time before either being caught by the police or managing to��attain��a new visa. They learn risky tricks from one another to get by. Yet, having a valid visa does not necessarily mean the end of their��struggles. In addition to the day-to-day challenges interacting with the locals���negative stereotypes, blatant discrimination, and both��subtle��and��overt��racism���they are constantly confronted with institutional hurdles such as police harassment, visa renewal bureaucracy, and more.

On Sanyuanli��Avenue in Guangzhou sits the��famous��African Pot Restaurant, a popular place for many ���Africans in Guangzhou.��� It is��owned by a Ghanaian man and his Chinese wife. A narrow and steep corridor leads to the entrance-door and into the dining hall, which is usually full with a mixture of African and Chinese customers. There are several things that capture one���s attention as one walks in. First, a display of flags for each of the African countries as decorative symbolism, a sense of��home in a distant land. Also, clearly visible from the entrance, is a warning in English and Chinese of��the severe consequences of drug-dealing in China.��And finally, all the employees, including the chef, are Chinese���a signal of how difficult it is for “Africans in Guangzhou” to achieve long-term legal status.

Indeed, there is no doubt that China is amongst the countries with the toughest and most restrictive immigration policies. Yet there is also little doubt that these��policies disproportionately��affect immigrants from African countries, creating a discrepancy between an ���anti-African immigrant campaign��� at the personal and local levels and a ���pro-African political��� discourse at the national and international levels.

So what do these issues say about the broader Afro-Chinese relations? Indeed, a lot. They say a lot about the unbalance and asymmetric nature of relations between one country and an entire continent. It is intriguing for example that of the 53 countries benefiting from China���s new��72 hours��and��144 hours��visa-free-transit policies, none of Africa���s over 50 countries qualify. And although such policies may be of less significance to the daily struggles of people like Richard, it would surely help minimize the sense of��preferential treatment��given to non-African foreigners in China.

Therefore, the challenge ahead for China-Africa relations lies in finding sound and mutually beneficial solutions to people���s mobility across both regions. There is a mutually shared feeling that��we are here because they are there, and as long as that government level policy persists, the presence in China of people from African countries is unlikely to subside. Instead, harsh treatment of migrants from Africa will only reinforce the growing dilemma between the boosted “China-Africa friendship” and historical solidarity at state and global levels and the persistent structural and institutionalized discriminations at individual and local levels.

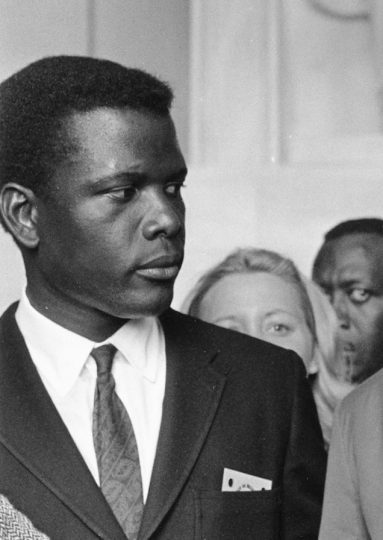

Sidney Poitier and Capitalist Decolonization

Sidney Poitier in 1963. Image Wiki Commons.

Sidney Poitier, who turned 92 on Wednesday, February 20, 2019, once complained about ���all those dumb-ass Tarzan movies,��� but the films that he made on the African continent���many of them committed to promoting a conciliatory, emphatically capitalist decolonization process���may be even more insidious. These include the films Cry, the Beloved Country (1952), set in apartheid South Africa; The Mark of the Hawk (1957), set in an unnamed African country; Something of Value (1957), also known as Africa Ablaze and set in colonial Kenya; and Mandela and de Klerk (1997), about political negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa.

The British-American-Nigerian co-production The Mark of the Hawk (Michael Audley, 1957) is perhaps the most striking. Starring Poitier and Eartha Kitt, it was largely shot on location in Nigeria. The film depicts an African revolution that is ultimately suppressed, its passions redirected by an American missionary (played by John McIntire), who proposes that nation building proceed ���within the framework of the Christian church.��� Unsurprisingly, the missionary prescribes ���patient faith��� in place of violent revolt, and his Christian paternalism puts an end to an anti-colonial uprising that, in his view, is ���moving too fast.���

Though made in Nigeria and eventually acquired by Universal-International for distribution to the country (as well as to Europe and the United States, among other global markets), The Mark of the Hawk is set in an unnamed British colony ���somewhere in Africa���; it therefore strategically subsumes a Nigerian specificity, which nevertheless remains eminently recognizable in the film���s many exteriors, under an abstracted Africanity whose marketability remains pronounced (as films from Kim Nguyen���s War Witch to Netflix���s Beasts of No Nation attest)���precisely the sort of racialized placelessness parodied in Keenan Ivory Wayans���s I���m Gonna Git You Sucka (1988), set in ���Any Ghetto U.S.A.��� (The 2016 Nollywood film Couple of Days offers its own, equally satirical spin on this device, superimposing the words ���Somewhere in Lagos��� over aerial shots of what is clearly Victoria Island.) It would, however, be a mistake to attribute such vagueness to racism or ethnocentric ignorance alone. When The Mark of the Hawk was made, the ���most basic foreign policy��� of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) ���was to avoid giving offence to any country which provided the [Hollywood] industry with any revenue,��� however meager. Explicitly identifying Nigeria was thus out of the question for a ���political��� production that, though made at the tail end of formal imperial rule and in the wake of Ghana���s independence, could not risk offending either a colonial government (which, in 1957, could easily have prevented the film���s exhibition in Nigeria) or its counterpart in the metropole.

In The Mark of the Hawk, the African characters are said to ���speak African,��� and a workers��� revolt, however evocative of actual Nigerian labor movements, is carefully tailored to reflect the sort of generalized, deracinated anti-colonial sentiments seen in the exactly contemporaneous Harry Belafonte film Island in the Sun (Robert Rossen, 1957), which is set on the fictional island of Santa Marta (���just Jamaica with the name changed,��� Belafonte called it), and whose plot pivots around the efforts of ���colored natives��� to claim capitalism���formerly the exclusive preserve of white plantation owners���for themselves. Island in the Sun opens in the manner of a travelogue, with a tutelary voice narrating images of Grenada (standing in for the fictional Santa Marta). ���Its main industry,��� says the voice on the soundtrack, ���is raising sugar, copper, cocoa���and exporting them. Originally a French island, its laborers were brought in slave ships from the Gold Coast of Africa, four and a half centuries ago, and now it is a British crown colony.��� The voice, it turns out, belongs to the colonial governor, Lord Templeton (Ronald Squire), who endeavors to instruct a visiting American journalist on the subject of empire. ���Do you think the West Indian is ready to govern himself?��� asks the journalist. ���When you get to know the island better,��� replies the governor, ���I shall be glad to discuss it with you.���

Lord Templeton is particularly fond of Harry Belafonte���s character, David Boyeur, the leader of a local trade union, whom Templeton affectionate calls ���our home-grown revolutionary.��� That Templeton is so enamored of alleged revolution���so chummy with the passionate activist Boyeur (who says of the governor, ���He needs me more than I need him���)���indicates his acceptance not merely of the inevitability of political independence for Santa Marta but also of decolonization as involving little more than a ���color shift��� under capitalism, a movement of black toward white in the shared pursuit of private accumulation. ���True independence,��� Templeton suggests, is ���merely��� a matter of ���the natives��� becoming properly capitalist, having absorbed the lessons of their ���masters.��� Boyeur agrees, albeit with more ���fire��� than the tired old colonialist can muster.

Described by one white observer as ���a man with real power,��� Boyeur is committed to fighting not private accumulation but the ���ignorant��� forces that might prevent its extension to those of African descent. Invoking non-capitalist African economies, which militate against individual acquisition and assign redistributive duties amid concern for ���the community,��� Boyeur raises the specter of communism as a menace to newly independent countries���an ideology and a political system that would ���shackle��� Black people no less forcefully than colonialism, precisely by preventing them from pursuing personal enrichment. Non-capitalist African economies���brought to Santa Marta in the memories of the enslaved, but foreclosed by the colonial system���threaten a return of the repressed, the revivification of a tradition vulnerable to communist takeover. Boyeur���s activism, then, is focused not on honoring and reestablishing tradition but on jettisoning it in the name of market ideology. ���One of the most important fights,��� he declares, ���is against tradition���this island is shackled with traditions!��� Boyeur may complain about the conditions of those ���working like beasts��� in the cane fields, but he is unprepared to concede���and seemingly unaware of the fact���that capitalism is the culprit, and not simply the cruelties of individual plantation owners. Asked to identify the island���s most pressing problem, Boyeur replies, ���Color.��� As in The Mark of the Hawk, capitalism is not to blame; instead, ���the real issue��� is the colonialist refusal to permit the formerly enslaved to compete for its profits. Rather than being allowed to pursue individual acquisition, these subjugated ���darkies��� are lucky to benefit from occasional acts of colonial largesse���mere ���charity��� (a concept that Boyeur despises, prescribing ���equality of opportunity��� under capitalism as its righteous alternative).

Island in the Sun is steeped in the proto-neoliberal language of individual responsibility: the colonial system must be replaced because it permits so many individual failures (of leadership, of conscience), and not because it serves to organize extractive capitalism at the explicit expense of community development. According to the film���s logic, colonialism���s principal fault is that it is hostile to the free market, its protectionist policies preventing the infiltration of American capital���an infiltration that, the film contends, would mean the enrichment of the ���native��� population. The message could not be clearer���or more clearly geared to reflect Hollywood���s own globalizing interests: colonialism must make way for the free market, a fundamentalist precept easily (if disingenuously and distractingly) couched in the language of racial equality. It is no accident that the one film said to be playing on the island of Santa Marta in 1957���Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger���s The Red Shoes (1948)���is a British import from the previous decade. The removal of colonialist protectionism will therefore mean, among other things, the replacement of such ���outdated��� nationalist fare with the sort of big-budget, narratively and iconographically transnational spectacles that Hollywood���s Island in the Sun���in Cinemascope and Technicolor, no less���represents.

For its part, Poitier���s The Mark of the Hawk frequently stages debates between two representatives of empire, both of whom recognize the inevitability of independence but disagree about the character of the colonized. ���We have no business making judgments���we���re newcomers here,��� says one of these white men, while the other insists that the ���whole trouble��� with colonized Africans ���is that they don���t appreciate what���s been done for them.��� Some argue that the Christian church has instilled anti-capitalist beliefs (���the poverty of mankind before God,��� and so on), but the American missionary insists that this isn���t the case���that the church wants merely to see the privileges of the free market, of private enterprise and possessive individualism, extend to formerly subjugated Africans. ���My church has taught the African Christians to hope for social justice,��� he says, ���while my white western world has kept it from them.��� In his reading, however, ���social justice��� refers primarily to equality under capitalism���to late-colonial efforts to ensure that the material and symbolic gains of an extractive, profit-seeking system will be open to Blacks as well as to whites, who will then ���compete��� in a purportedly free market, unfettered by any colonial or otherwise paternalist restrictions.

Island in the Sun shares this stark racial binarism, while similarly couching anti-colonial sentiment as a ���colored struggle��� to achieve inclusion in capitalism���a process that cannot unfold ���too fast��� if true transracial harmony is to be achieved. Thus even as they stress the acceleration and intensification of globalizing capitalism at mid-century, both films prescribe ���patience��� to African and diasporic populations whose capitalist ambitions are nevertheless heartily endorsed.

MaryEllen Higgins has commented on the importance of viewing ���Hollywood���s Africa not as a series of detached fantasies that offer pure entertainment, but as projections���entertaining as they may be���that reflect various national and international investments, both material and ideological.��� Chinua Achebe may have been describing much of Poitier���s filmography when he referred critically to ���Africa as setting and backdrop which eliminates the African as human factor���Africa as a metaphysical battlefield devoid of all recognizable humanity, into which the wandering European enters at his peril.���

As is well known, Achebe, in his 1958 novel Things Fall Apart, endeavored to counter what he saw as Joyce Cary���s misrepresentation of Nigeria in Cary���s ���African��� novel Mister Johnson (1939). But he might also have been responding to The Mark of the Hawk, whose production in Nigeria coincided with the writing of Things Fall Apart. Achebe���s protagonist, Okonkwo, is not unlike Poitier���s character in The Mark of the Hawk: both men are ���born leaders,��� charismatic and idealistic, and their fates are equally entwined with the efforts of British colonialism to shape Nigeria and Nigerians in its own image. But where Okonkwo chooses violence (including self-destruction) as a rebuke to British rule���a victim, in Achebe���s tragic framework, of colonial modernity���Poitier���s character opts for Christianization, reverting to a ���peaceful protest��� of colonialism that doubles as an active embrace of American capitalism. Young���s script seems to understand the profoundly destabilizing potential of violence���its capacity not simply to subvert colonial rule but also to stave off the encroachment of capitalism. It is, quite simply, a socialist revolution that the American missionary must prevent in The Mark of the Hawk���a violent transfer of power from colonialists to anti-capitalists.

This normalization of capitalism is critiqued in a number of canonical African films. Consider, for instance, La Vie est Belle (Mwez�� Ngangura and Beno��t Lamy, 1987), in which a commitment to individual accumulation is taken to outrageous extremes by a Congolese landlady, Mama Dingari (Mazaza Mukoko), who raises rents arbitrarily and often. ���This mama has a reputation for being greedy,��� observes one of her tenants; ���Life has become less beautiful,��� says another, whenever Mama Dingari wields her extortionate power. And in Flora Gomes��� The Blue Eyes of Yonta (1991), ���capitalist independence��� represents a contradiction in terms, as Vicente (Ant��nio Sim��o Mendes), revolutionary-turned-businessman, is forced to concede, ���Money is the weapon now…We thought that independence would be for everyone, but it���s not.��� He even speaks of an all-encompassing capitalism, ominously referring to the Atlantic Ocean as being ���married to container ships.��� Made in 1991������the year of liberalization,��� one character calls it, before a district-wide power outage eliminates the electrical supply to his classroom (a symptom of the cuts in public spending required by structural adjustment)���The Blue Eyes of Yonta makes clear some of the neocolonialist effects of the capitalist world-system. ���First I loaded crates for the Portuguese,��� says one character, an elderly fisherman, of his life under colonialism. ���I was overjoyed at independence. I thought my life would change. But these crates and sacks are as heavy as the Portuguese ones.���

The 1957 release of Poitier���s The Mark of the Hawk heralded the hundred-year anniversary of the arrival of Anglican missionaries in Nigeria. The film���s conciliatory Christianity���like that of a number of Poitier���s other ���African��� dramas���would have to be countered by African directors in the post-independence period. In Guelwaar (1992), for instance, Ousmane Sembene provides an opposite view of Christianity from the one promoted by The Mark of the Hawk. Through a title character whose home is the site of political meetings at which Christians discuss ���the misappropriation of foreign aid and how it ends up sold or distributed to party members,��� as well as ���the illegal accumulation of wealth and theft of public funds,��� Guelwaar offers an implicit critique of an understudied title in Poitier���s ever-contentious oeuvre.

February 21, 2019

Laughing pains

Trevor Noah. Image Credit slgckgc via Flickr (CC).

One of the South African comedian Loyiso Gola���s most incisive jokes is this punchline: ���Do white people know where��Gugulethu��is? Well you should know, you put us there��motherfuckers.���

Gugulethu��is a township about 20 minutes outside central Cape Town where blacks had been forcibly resettled in the 1960s. The joke is biographical. Gola, now 35, grew up in the township. And his joke also reveals the expansive potentials of comedy in a complex, unequal South Africa.

For many of the country���s comedians, the political realities of the country and the world are intimately intertwined with the practice of comedy, a practice that has turned out to be a prominent avenue for contributing to social dialogue and providing a snapshot for outsiders into what South Africa is currently grappling with.

Comedy in South Africa during apartheid was largely dominated by white comedians, and you could find comedy on the radio, in a few performance spaces,��and on television in late 1970s with programs such a Biltong and��Potroast, a weekly comic debate between white South African comedians and white British comedians. In this case, the industry and the jokes were dominated by those who had social power in the space. Following 1994 and the formal and legal end of apartheid, there was a rapid growth of comedy, particularly from black comedians. With more��entertainment��venues being built in cities like Cape Town and Johannesburg, infrastructure was being laid for a new generation of black and coloured��voices that have been excluded and marginalized socially, politically, and economically.

The burgeoning field of comedy in South Africa is dynamic, and while Trevor Noah���s name is sometimes oversaturated in the discussion of South African comedy, his distinctive and ambitious success demonstrate the appetite for newness and for self-reflection. In Noah���s first��Netflix special,��You Laugh But It’s True, he sold out two nights at the Joburg Theater��in 2011 with his one man show, which was the largest debut show by a South African comedian.

You Laugh But It’s True��serves an archival piece of South African comedy, bringing together the voices of white and black comedians to discuss the realities of building infrastructure for comedy, the grind of making a career, and the uniqueness of South Africa, in its joys and devastations, inequities and potential. In this discussion, we see the solidarity as well as the fractures amongst comedians, with many white comedians exemplifying racial resentment by no longer being interested in hearing any more jokes about the townships or apartheid.

This racial resentment demonstrates the anti-blackness South Africa is marked with; the lack of consideration of what apartheid did, what it took from people (lives, land, human dignity) and a lack of rigor in rectifying the violence done demonstrate the tensions that the country is grappling with. In a 2016 comedy special in New York, Gola explains to the audience South Africa���s 1992 apartheid vote and how only allowing white people to vote on the end of apartheid was like allowing your children to vote on bedtime. Moreover, he talks about how the 39% of the white population who voted against ending apartheid were saying, ���No! We���re having a good time.���

Comedy is proving to be just one avenue to explore and express black radical politics, including larger projects of decolonization. In her latest standup special for Netflix, released this month (as part of the series ���Comedians of the World���), Tumi Morake, closes her set in Montreal with ���Tell America to stop sending their 16 year-olds to build our schools. They���re making us a shithole. I���m not joking, these kids come and they can���t wipe their ass or fry an egg, but they���re going to build a school in Africa. How?��� Playing on the funny, but not so funny, realities of imperialism and white saviorism, Morake confronts the actions of global communities and most likely the white audience members who have donated to an ���Africa fund��� at least once in their life.

The��2017 documentary��Kill or Die, we follow the daily experiences of four comedians, Thulani��Ntlabati,��Ebenhaezer��Dibakwane,��Khanyisa��Bunu, and��Aljoy��Chik, all working and based in Johannesburg. In the film, we hear from Chik, originally from Zimbabwe, who uses comedy as a means of making sense of his life and healing. Both��Dibakwane��and��Bunu��abandoned education and a 26-year career of teaching respectively and turned to comedy as a means of interrogating social issues such as education, philosophy, and racism. For��Dibakwane, it became a more direct route for social change and while he is interested in dissecting education, philosophy, and racism, he also commented on his desire be a comedian and not the tokenized or pigeon holed ���black��� comedian.

The beauty of comedy lies in its disarming nature; going to a comedy gig can in many ways be an avenue for tapping out, yet many South African comedians keep you tapped in. In the opening scene of��Kill or Die, comedian��Ntlabati��introduces himself and the person shooting the��documentary��to the audience telling them, ���She’s going to be shooting as I���m performing���it’s not the first time a white��person shoots a black person for having fun.��� And while the audience laughs, Thulani follows up with ���No its true, during apartheid they used to shoot people for dancing.���

However, the act of making people remember is not an easy task. Perhaps one of the greatest navigations of comedy in South Africa is audience. In corporate gigs, where more substantial pays lies, there are higher proximities of white audiences, meaning everything from jokes about race to television can become at best��not��relatable or, at worst, contentious.

Managing this disarmament of audiences is one of the many pertinent skills South African comedians have adapted to. For��Bunu, featured in��Kill or Die, she must engage in two kinds of disarmaments, both as a black and as woman, needing to win over audiences before they write her off. In a male dominated field that also possesses the tendency to reproduce misogynistic ideas and caricatures of black women for material, women comedians can face an uphill battle.��Bunu��manages this masterfully by being incredibly sincere and earnest, and as she says, ���when you are female and you walk out on stage people don���t really expect you, but you have to know your story so that you can take them off by surprise.���

February 20, 2019

How to manage post-colonial African economies

Following the tracks from the Zimbabwe border to Zambia at sunset. Image credit Youngrobv via Flickr (CC).

A lot has been written about��the failings of the ZANU-PF regime in Zimbabwe since the 1980s. Analyses of economic collapse that correctly and consistently point to the capacity and shortcomings of this nationalist liberation movement-turned-government have centered on its authoritarian rule, maladministration, corruption, neo-patrimonialism,��clientelism, political paternalism and violence. Acknowledging initial positives in health and education, land reform and mixed attempts at economic indigenization, other observers have turned towards amplifying what they view as the positives from these experiences. Illuminating as these perspectives are, they are insufficient in explaining the current crisis. They miss a critical point: an assessment of how to manage post-colonial economies.

The politics and predation of the economy by ZANU-PF became the rallying point of the country���s opposition movement from the late 1990s onwards. As the economic crisis escalated into the 2000s, it resulted in hyperinflation and the demonetization of the Zimbabwean dollar. The only brief respite was offered by dollarization, a short-lived moment of the Government of National Unity between 2009 and 2013 but the crisis soon resumed following the controversial 2013 election victory of ZANU PF and its eventual introduction of a pseudo currency: bond money (including electronic money; hereafter referred to as��bollars) in 2016. Building on this, the post-coup dispensation of President��Mnangagwa��argues that it simply needs more time to get the economy on an even keel. But the opposition, now under Nelson��Chamisa, who succeeded as party leader following the passing of Morgan Tsvangirai, maintains that it can do a better job. Without elaborating its policies, the current MDC���s policies are not dissimilar to those of ZANU- PF, which has led to increased political, public and academic discourses about the best approach to resolving the enduring crisis.

Characteristic of the crisis has been the consistent problem of managing money. Whereas the early 2000s legacies are associated with hyperinflation, the post 2013 challenges were anchored on a shortage of foreign exchange emanating from constrained production capacity. This is what led to the introduction of��bollars��by Reserve Bank Governor John��Mangudya. But their focus on monetary policy has been ineffective. Even as��Chinamasa��was replaced by��Mthuli��Ncube��as Finance Minister following the contested post-coup ZANU-PF election victory, the government���s Transitional Stabilisation Programme (TSP) has not worked. If anything, the official maintenance of an artificial 1:1 parity between the��bollars��and US��dollars has caused further structural hiccups in the economy where parallel market rates have depreciated the pseudo currency in excess of 350% against the greenback.

Ncube��proposes that the 1:1��bollar��to US dollar parity is just an interim measure laying the ground-work for a more stable local currency to be introduced in the near future. Meanwhile, his fiscal consolidation plan to reduce government spending, settle domestic government debts by raising taxes and his plan to pay off international debt lack substance. Economic problems in Zimbabwe cannot be reduced to fiscal consolidation; they are much deeper, historical and structural.��Ncube���s��neoliberal leanings neglect production issues. On top of unchecked government spending, the economy is not producing sufficiently to generate foreign exchange to achieve equilibrium. There is just no way a country without secure land agrarian tenure, characterized by leakages, money laundering and under-invoicing in its corporate sectors across the economy can run efficiently. The economy displays numerous features of state-capture and rampant corruption that politicians ignore, and until at least some of these issues are meaningfully confronted, no amount of tinkering around the edges will help. If anything, the problems will worsen.

This raises fundamental question about the logic of economy management in Zimbabwe. There seems to be an enduring fascination with technocrats and general confidence in their capacity to address the country���s problems despite their disappointing record. This can be traced back from the country���s first Minister of Economic Planning (1980-1983) and second and longest serving Minister of Finance, Bernard��Chidzero��(1983-1995). Despite beliefs that post-independence economic performance was good, the illusion was created by the advances made in the expansion of health and education provision. But in economic terms, the country has consistently been on a trajectory of economic decline, if GDP numbers are anything to by. This is worth examining as the source and endurance of the crisis in Zimbabwe.

In analyzing these challenges, the works of scholars such as��Samir��Amin��are illuminating. His argument in the first ever publication of the��Review of African Political Economy��in 1974, focusing on “Accumulation on a World Scale” suggests that the colonial economy was designed to promote development in the metropole and inhibit it in the periphery. These structures were maintained by post-colonial governments in perpetuity. More recently, Alden Young���s��book,��Transforming Sudan, interrogates the origins of the economic framework inherited by Sudanese policy makers as an Anglo-Egyptian condominium. This framework is anchored on a system of National Income Accounts (NIA). The NIA framework considers the extent to which a country accounts for its Gross National and Domestic Product (GDP), among other indicators. These are the yardstick for measuring the developmental success of government policies. However, wherever they have been ineffective, as in the case of Zimbabwe, the government maintains the performance of seeking economic solutions while deploying the arsenal of patronage and authoritarian rule to maintain power.

The use of such abstraction has its roots in the late colonial period. Starting with Colin Clark���s work published in the 1940s, these statistical tools were adapted from the global North and became the popular mode of economic management in Nigeria in the late 1940s and 1950s. Through the work of��Phylis��Dean, data was collected for the accounts of central African nations from 1947. But by the time Nyasaland (Malawi), Northern and Southern Rhodesia (Zambia and Zimbabwe respectively) were brought into the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1953; she concluded that the NIA framework would be difficult to implement in an African context. Dean could not measure communal agrarian work done by work parties, children and women easily in monetary terms. She also found it difficult to trace migration wages, for example, because of seasonal employment, lack of traceable work contracts and for economies whose currency were tied to empire. Yet African economic technocrats unquestioningly adopted NIA following independence.

Despite the limitations of NIA, a commission headed by Oliver Stone encouraged the United Nations (UN) to make its adoption by newly independent countries a condition for membership in the organization. To guide the process, the UN created the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). Among its first officials was��Chidzero, the future Finance Minister of Zimbabwe. His experience there between 1960 and 1968, and as Deputy Secretary General at the United Nations Commission for Trade and Development (UNCTAD), influenced his work in government between 1980 and 1995.

Zimbabwe adopted NIA conditions for UN membership at independence. Despite its modernization undertones, the NIA framework was problematic. With limited research on NIA in the case of Zimbabwe, the Sudan example is illustrative. Young shows how postcolonial Sudan maintained late colonial NIA structures, thus embedding colonial relations of exchange. This dilemma raises the critical question: what is an economy?

As Sudan gained its independence, development became anchored on ways to account for and increase especially the production of cotton to earn foreign exchange as part of its state-building. The country borrowed and constructed roads, rail, dams for hydroelectric and irrigation infrastructure to achieve this. What was transformed in Sudan by the 1960s, was not so much the colonial economy but the people who planned and managed it at independence. So, instead of any significant structural transformation, the concentration with income accounts (read GDP) only led to an entrenchment of colonial economic structures.

Zimbabwe adopted the same trap at independence. The country pursued policies anchored on GDP performance while trying to sustain a floating Zimbabwe dollar. During��white��Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence��(UDI) era, Rhodesian currency was maintained by stringent exchange controls between 1965 and 1979. At independence, radical transformation was stifled by limitations placed on land redistribution, which could only occur on a willing buyer-willing seller model, and respect for property placed by the Lancaster Agreement. Also, the need to attract foreign investors led��Chidzero��to adapt what he called a pragmatic approach, avoiding socialist rhetoric and guaranteeing the safety of investments in Zimbabwe. In attempting to settle inherited��debt,��Chidzero��hosted an investment conference in 1981, the Zimbabwe Investment Conference. ZIMCORD, as the investment conference was known,��raised just over US$ 3 billion as Zimbabwe. It was expected that despite the limitations of Lancaster, the funds would be a shot in the arm of development supporting a NIA framework predicated on maintaining the economic structure��through exports. But by the late 1980s, imports nevertheless outstripped exports and the economy was under severe strain that led it to seek IMF and World Bank support.

Chidzero��was at the forefront of pushing for the adoption of neoliberal economic reform espoused by the IMF/WB conditional for securing loans to balance the national budget and recurrent BOP deficits. He adopted the disastrous Economic Structural Adjustment Program (ESAP) between 1990 and 1995. The program was notorious for opening up fragile economies to international cheap imports, undermining prospects of industrial growth and thus weakening their currencies and economies. As��Alois��Mlambo��demonstrated, ESAP eroded the early gains in health and education. Yet successive finance ministers and generations of economists trained on these kinds of economics logic unquestioningly followed the legacy left by��Chidzero��who eventually died in 2002. The crisis in today���s Zimbabwe was rapidly accelerated by off-budget expenditure on War Veterans��payouts��and the government���s misadventure in the DRC in 1997, resulting in the rapid depreciation of the��Zim��dollar.

Ncube���s��approach to economic management mirrors that of��Chidzero-style technocrats, which exposes a deep ignorance of crucial structural, political and historical antecedents of the enduring crisis. In an economy with more than 90% formal unemployment, under military rule, governed through patronage and violence, policies designed for an industrialized country with near-democratic institutions and systems can never work. The artificial separation between politics and economics and the fiction that politicians can focus on the politics while the technocrats work on the economy is a false dichotomy. Even in the 1980s, corruption, patronage and the heavy financial costs of pursing the��Gukurahundi��massacre not only cost human lives and caused untold suffering, but also placed a heavy burden on the��fiscus. The technocrat that��Ncube��appears to be, will not turn around the Zimbabwean economy.

Even under the best of political and social circumstances, African economies have other international, historical and legacy impediments that need to be confronted before they can make that turn. While African technocrats are still pursuing dead approaches to economic management, the rest of the world is moving on. There has been a recent global resurgence in interest of African Economic History asking that crucial question: “Why are we so poor?” Diverse international scholars are actively undertaking various interdisciplinary studies that address this question. Ironically, Zimbabwe is one of a handful of African countries with a fully functional��Department of Economic History at the University of Zimbabwe, where such questions have been studied for decades, and an amazing group of scholars and students has been produced. Sadly, the state has made no use of this intellectual capital.

Furthermore, there is a big global shift that has prompted a rethinking of economics globally and a movement spearheaded by the Institute of New Economic Thinking (INET) to investigate these issues. The Africa Working Group and the Economic Development Working Groups of INET���s Young Scholars�����Initiative is taking the question of the challenges of Africa to the world. Zimbabwean economic historians have been leading lights��in this regard, hosting workshops, conferences and plenaries inside the country and abroad to tackle these issues.

But who is listening?

How to manage post-colonial economies

Following the tracks from the Zimbabwe border to Zambia at sunset. Image credit Youngrobv via Flickr (CC).

A lot has been written about��the failings of the ZANU-PF regime in Zimbabwe since the 1980s. Analyses of economic collapse that correctly and consistently point to the capacity and shortcomings of this nationalist liberation movement-turned-government have centered on its authoritarian rule, maladministration, corruption, neo-patrimonialism,��clientelism, political paternalism and violence. Acknowledging initial positives in health and education, land reform and mixed attempts at economic indigenization, other observers have turned towards amplifying what they view as the positives from these experiences. Illuminating as these perspectives are, they are insufficient in explaining the current crisis. They miss a critical point: an assessment of how to manage post-colonial economies.

The politics and predation of the economy by ZANU-PF became the rallying point of the country���s opposition movement from the late 1990s onwards. As the economic crisis escalated into the 2000s, it resulted in hyperinflation and the demonetization of the Zimbabwean dollar. The only brief respite was offered by dollarization, a short-lived moment of the Government of National Unity between 2009 and 2013 but the crisis soon resumed following the controversial 2013 election victory of ZANU PF and its eventual introduction of a pseudo currency: bond money (including electronic money; hereafter referred to as��bollars) in 2016. Building on this, the post-coup dispensation of President��Mnangagwa��argues that it simply needs more time to get the economy on an even keel. But the opposition, now under Nelson��Chamisa, who succeeded as party leader following the passing of Morgan Tsvangirai, maintains that it can do a better job. Without elaborating its policies, the current MDC���s policies are not dissimilar to those of ZANU- PF, which has led to increased political, public and academic discourses about the best approach to resolving the enduring crisis.

Characteristic of the crisis has been the consistent problem of managing money. Whereas the early 2000s legacies are associated with hyperinflation, the post 2013 challenges were anchored on a shortage of foreign exchange emanating from constrained production capacity. This is what led to the introduction of��bollars��by Reserve Bank Governor John��Mangudya. But their focus on monetary policy has been ineffective. Even as��Chinamasa��was replaced by��Mthuli��Ncube��as Finance Minister following the contested post-coup ZANU-PF election victory, the government���s Transitional Stabilisation Programme (TSP) has not worked. If anything, the official maintenance of an artificial 1:1 parity between the��bollars��and US��dollars has caused further structural hiccups in the economy where parallel market rates have depreciated the pseudo currency in excess of 350% against the greenback.

Ncube��proposes that the 1:1��bollar��to US dollar parity is just an interim measure laying the ground-work for a more stable local currency to be introduced in the near future. Meanwhile, his fiscal consolidation plan to reduce government spending, settle domestic government debts by raising taxes and his plan to pay off international debt lack substance. Economic problems in Zimbabwe cannot be reduced to fiscal consolidation; they are much deeper, historical and structural.��Ncube���s��neoliberal leanings neglect production issues. On top of unchecked government spending, the economy is not producing sufficiently to generate foreign exchange to achieve equilibrium. There is just no way a country without secure land agrarian tenure, characterized by leakages, money laundering and under-invoicing in its corporate sectors across the economy can run efficiently. The economy displays numerous features of state-capture and rampant corruption that politicians ignore, and until at least some of these issues are meaningfully confronted, no amount of tinkering around the edges will help. If anything, the problems will worsen.

This raises fundamental question about the logic of economy management in Zimbabwe. There seems to be an enduring fascination with technocrats and general confidence in their capacity to address the country���s problems despite their disappointing record. This can be traced back from the country���s first Minister of Economic Planning (1980-1983) and second and longest serving Minister of Finance, Bernard��Chidzero��(1983-1995). Despite beliefs that post-independence economic performance was good, the illusion was created by the advances made in the expansion of health and education provision. But in economic terms, the country has consistently been on a trajectory of economic decline, if GDP numbers are anything to by. This is worth examining as the source and endurance of the crisis in Zimbabwe.

In analyzing these challenges, the works of scholars such as��Samir��Amin��are illuminating. His argument in the first ever publication of the��Review of African Political Economy��in 1974, focusing on “Accumulation on a World Scale” suggests that the colonial economy was designed to promote development in the metropole and inhibit it in the periphery. These structures were maintained by post-colonial governments in perpetuity. More recently, Alden Young���s��book,��Transforming Sudan, interrogates the origins of the economic framework inherited by Sudanese policy makers as an Anglo-Egyptian condominium. This framework is anchored on a system of National Income Accounts (NIA). The NIA framework considers the extent to which a country accounts for its Gross National and Domestic Product (GDP), among other indicators. These are the yardstick for measuring the developmental success of government policies. However, wherever they have been ineffective, as in the case of Zimbabwe, the government maintains the performance of seeking economic solutions while deploying the arsenal of patronage and authoritarian rule to maintain power.

The use of such abstraction has its roots in the late colonial period. Starting with Colin Clark���s work published in the 1940s, these statistical tools were adapted from the global North and became the popular mode of economic management in Nigeria in the late 1940s and 1950s. Through the work of��Phylis��Dean, data was collected for the accounts of central African nations from 1947. But by the time Nyasaland (Malawi), Northern and Southern Rhodesia (Zambia and Zimbabwe respectively) were brought into the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1953; she concluded that the NIA framework would be difficult to implement in an African context. Dean could not measure communal agrarian work done by work parties, children and women easily in monetary terms. She also found it difficult to trace migration wages, for example, because of seasonal employment, lack of traceable work contracts and for economies whose currency were tied to empire. Yet African economic technocrats unquestioningly adopted NIA following independence.

Despite the limitations of NIA, a commission headed by Oliver Stone encouraged the United Nations (UN) to make its adoption by newly independent countries a condition for membership in the organization. To guide the process, the UN created the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). Among its first officials was��Chidzero, the future Finance Minister of Zimbabwe. His experience there between 1960 and 1968, and as Deputy Secretary General at the United Nations Commission for Trade and Development (UNCTAD), influenced his work in government between 1980 and 1995.

Zimbabwe adopted NIA conditions for UN membership at independence. Despite its modernization undertones, the NIA framework was problematic. With limited research on NIA in the case of Zimbabwe, the Sudan example is illustrative. Young shows how postcolonial Sudan maintained late colonial NIA structures, thus embedding colonial relations of exchange. This dilemma raises the critical question: what is an economy?

As Sudan gained its independence, development became anchored on ways to account for and increase especially the production of cotton to earn foreign exchange as part of its state-building. The country borrowed and constructed roads, rail, dams for hydroelectric and irrigation infrastructure to achieve this. What was transformed in Sudan by the 1960s, was not so much the colonial economy but the people who planned and managed it at independence. So, instead of any significant structural transformation, the concentration with income accounts (read GDP) only led to an entrenchment of colonial economic structures.

Zimbabwe adopted the same trap at independence. The country pursued policies anchored on GDP performance while trying to sustain a floating Zimbabwe dollar. During��white��Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence��(UDI) era, Rhodesian currency was maintained by stringent exchange controls between 1965 and 1979. At independence, radical transformation was stifled by limitations placed on land redistribution, which could only occur on a willing buyer-willing seller model, and respect for property placed by the Lancaster Agreement. Also, the need to attract foreign investors led��Chidzero��to adapt what he called a pragmatic approach, avoiding socialist rhetoric and guaranteeing the safety of investments in Zimbabwe. In attempting to settle inherited��debt,��Chidzero��hosted an investment conference in 1981, the Zimbabwe Investment Conference. ZIMCORD, as the investment conference was known,��raised just over US$ 3 billion as Zimbabwe. It was expected that despite the limitations of Lancaster, the funds would be a shot in the arm of development supporting a NIA framework predicated on maintaining the economic structure��through exports. But by the late 1980s, imports nevertheless outstripped exports and the economy was under severe strain that led it to seek IMF and World Bank support.

Chidzero��was at the forefront of pushing for the adoption of neoliberal economic reform espoused by the IMF/WB conditional for securing loans to balance the national budget and recurrent BOP deficits. He adopted the disastrous Economic Structural Adjustment Program (ESAP) between 1990 and 1995. The program was notorious for opening up fragile economies to international cheap imports, undermining prospects of industrial growth and thus weakening their currencies and economies. As��Alois��Mlambo��demonstrated, ESAP eroded the early gains in health and education. Yet successive finance ministers and generations of economists trained on these kinds of economics logic unquestioningly followed the legacy left by��Chidzero��who eventually died in 2002. The crisis in today���s Zimbabwe was rapidly accelerated by off-budget expenditure on War Veterans��payouts��and the government���s misadventure in the DRC in 1997, resulting in the rapid depreciation of the��Zim��dollar.

Ncube���s��approach to economic management mirrors that of��Chidzero-style technocrats, which exposes a deep ignorance of crucial structural, political and historical antecedents of the enduring crisis. In an economy with more than 90% formal unemployment, under military rule, governed through patronage and violence, policies designed for an industrialized country with near-democratic institutions and systems can never work. The artificial separation between politics and economics and the fiction that politicians can focus on the politics while the technocrats work on the economy is a false dichotomy. Even in the 1980s, corruption, patronage and the heavy financial costs of pursing the��Gukurahundi��massacre not only cost human lives and caused untold suffering, but also placed a heavy burden on the��fiscus. The technocrat that��Ncube��appears to be, will not turn around the Zimbabwean economy.

Even under the best of political and social circumstances, African economies have other international, historical and legacy impediments that need to be confronted before they can make that turn. While African technocrats are still pursuing dead approaches to economic management, the rest of the world is moving on. There has been a recent global resurgence in interest of African Economic History asking that crucial question: “Why are we so poor?” Diverse international scholars are actively undertaking various interdisciplinary studies that address this question. Ironically, Zimbabwe is one of a handful of African countries with a fully functional��Department of Economic History at the University of Zimbabwe, where such questions have been studied for decades, and an amazing group of scholars and students has been produced. Sadly, the state has made no use of this intellectual capital.

Furthermore, there is a big global shift that has prompted a rethinking of economics globally and a movement spearheaded by the Institute of New Economic Thinking (INET) to investigate these issues. The Africa Working Group and the Economic Development Working Groups of INET���s Young Scholars�����Initiative is taking the question of the challenges of Africa to the world. Zimbabwean economic historians have been leading lights��in this regard, hosting workshops, conferences and plenaries inside the country and abroad to tackle these issues.

But who is listening?

February 19, 2019

Magical realism in Accra

Still from film The Burial of Kojo. Credit Ofoe Amegavie.

The Ghanaian film,��The Burial of��Kojo,��is a gift to self, offered as a collective experience which expands on African oral traditions and allegories of a metaphysical journey. The film sparks a vital conversation about the intersections of heritage, politics, and spirituality in Ghana and in Africa at large.

It is a tale of two brothers,��Kojo��and��Kwabena, whose tumultuous relationship spirals when��Kwabena���s��wife dies on their wedding night in an accident caused by��Kojo. The story is told through the voice of��Kojo���s��young daughter��Esi. Embodying the future,��Esi��represents a generation tackling a complex conversation between the present and an ancestral plane of sorts, where her dreams lead her to uncover truths about the masked rivalry between her father and uncle��Kwabena. Playing on facets of time and space through a magical realist lens, the non-linear plot, the film unfolds with��Esi��caring for a Sacred Bird that is hunted by a mysterious crow; lending it a thread of symbolism and foretelling. When her father goes missing,��Esi��sets the Sacred Bird free to encounter him again. As her mother��Ama��and a local detective struggle to locate��Kojo, she is often shown running, alluding to the pressures of running out of time.��Esi��is also wise beyond her years, taking on the role of her father���s keeper in a tender relationship where they are ever-present in spirit and flesh.

This award-winning screenplay is written and directed by��Samuel��Bazawule, a renowned hip-hop artist who goes by the stage name Blitz the Ambassador. His music has long fused traditional and contemporary sonic elements, with accompanying ethereal videos detailing lived-experiences in Africa and the diaspora. In this same storytelling tradition,��Bazawule��reintroduces his homeland Ghana to the world in��The Burial of��Kojo,��highlighting the neglected beauty of the everyday in an unconventional manner. We begin inside our minds, led by curious visuals and electric feels, as the opening scenes provoke familiar memories that resemble mysterious terrains. We transition between urban and rural, into dreamscapes and landscapes animated on inverted screens with delicate treatments of color, shadow-play, and sound. I am reminded of the fluidity between life and the afterlife, of navigating through bliss and pain, and of elusive memories from my childhood which resurface through the eyes of the young narrator��Esi.

Still from film The Burial of Kojo. Credit Ofoe Amegavie.

Still from film The Burial of Kojo. Credit Ofoe Amegavie.As the plot unveils, we are forced to face politically charged undertones that deal with corruption,��galamsey��(illegal gold mining), and unemployment in Ghana. The social, spiritual, and emotional implications of the risks taken by the marginalized,��Kojo��and his family, are linked with the jarring realities of police bribery and Chinese-led neocolonial activity in Africa. However, the people, emotions, and culture remain central in this narrative as the film provides insight into the intimacies of family. As much as it is a tale of betrayal, survival, and exploitation, it is equally about ontology, purpose, and innocent curiosity. Through the inclusion of metaphorical characters,��The Burial of��Kojo��prompts us to reimagine dimensional binaries and the coexistence of “utopia” and “dystopia” in an African terrain. The incorporation of a foretelling telenovela, with a parallel narrative to that of��Kojo��and��Kwabena, adds a twist to this play on spatial awareness. Elements of��afrofuturist��spaces, much like��Black Panthers�����Wakanda��or the��Kingdom of��Or��sha��in��Children of Blood and Bone, are visualized through riveting cinematography that alternates our senses between mind and matter.

The Burial of��Kojo��is an affirmation of the power of representation and a jolt in the culture of visual storytelling. The research and time poured into this production is evident in the questions we are forced to ask ourselves and the symbolisms that stretch our imaginations during the viewing experience.