Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 233

January 30, 2019

The spear of the nation

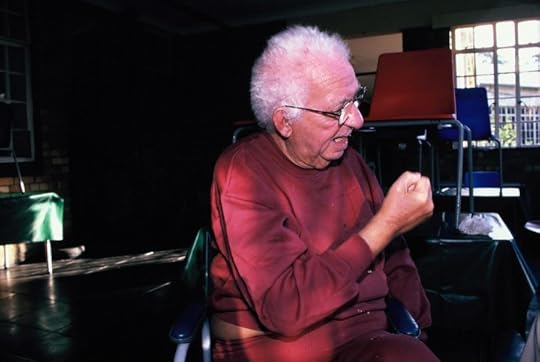

Dimitris Tsafendas. Image credit Ellen Elmendorp.

It was at 2:20 pm on the 6th of September 1966 when Dimitris Tsafendas, a parliamentary messenger, stabbed Hendrik Verwoerd to death���South Africa���s prime minister and the so-called ���architect of apartheid������inside the House of Assembly in Cape Town. In a frantic scramble,��Tsafendas��was pulled physically off Verwoerd by members of parliament, dragged from the chamber and taken to Caledon Square Police Station. There he was interrogated at length and tortured frequently. In a statement to the police on 11 September,��Tsafendas��said, ���I did believe that with the disappearance of the South African prime minister a change of policy would take place��� I was so disgusted with the racial policy that I went through with my plans to kill the prime minister.��� Questioned by a senior police officer,��Tsafendas��gave a coherent account of his life, including his decision to kill Verwoerd, in a statement which covered eleven pages.

In a second statement on the 19th of September,��Tsafendas��articulated in detail how he planned the assassination and gave an account of his prior movements. He revealed that his initial intention was to shoot Verwoerd at an evening social event, then take refuge in a Greek tanker,��Eleni,��anchored in Cape Town harbor, and hopefully escape when the ship sailed. When this plan failed because he could not find a suitable firearm, he decided to use a knife. He believed that it was his duty to kill Verwoerd when he had the opportunity. He spelled out his reasons as follows: ���Every day, you see a man you know committing a very serious crime for which millions of people suffer. You cannot take him to court or report him to the police, because he is the law in the country. Would you remain silent and let him continue with his crime, or would you do something to stop him?���

Tsafendas��knew that using a knife, because of the necessity for intimate physical contact with his victim, meant that he had no chance of escape. However, he told the police emphatically that he did ���not care��about the consequences, for what would happen to me afterwards.��� He said, ���I didn���t care much and didn���t give it a second thought that I would be caught.���

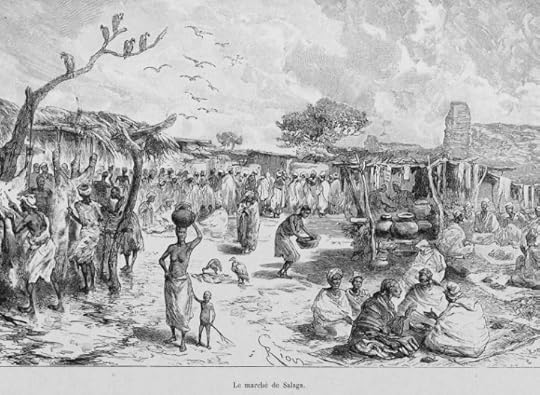

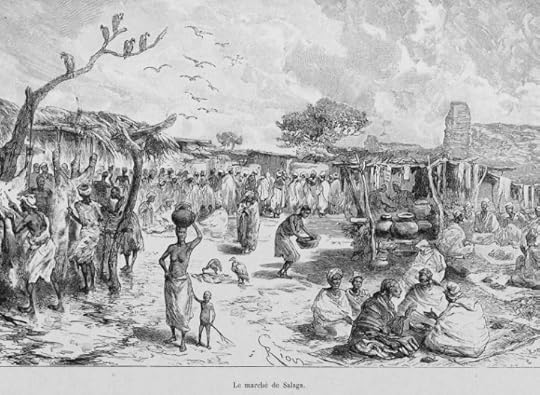

Tsafendas in Egypt. Image courtesy Liza Key.

Tsafendas in Egypt. Image courtesy Liza Key.In a story that can finally be told in full, decades after his death and long after the end of state-sanctioned racism in South Africa, it can be revealed how the apartheid regime squelched discussion of��Tsafendas��� motivations by having him declared mad���after all who would want to kill whites��� beloved leader���in order to stifle the left.

Tsafendas��was born in 1918 in��Louren��o��Marques, now Maputo, capital of Mozambique in East Africa, which had long been a colony of Portugal. His father was Michalis��Tsafantakis, a Greek from Crete, and his mother was Amelia Williams, daughter of an African mother and a European father, who grew up as a member of the Shangaan tribe.��Tsafendas��spent his first two and half years with his biological parents before he was sent by his father to Egypt to be brought up by his grandmother and his aunt, Michalis���s sister. He returned to Mozambique when he was seven, by which time his father was married to a Greek woman with whom Michalis already had two children.��Tsafendas��grew up in a highly revolutionary environment. His father���s family was famed for producing rebels who fought for Crete in the War of Independence against the ruling Ottomans.��Tsafendas��was named Dimitris after one of them, an uncle who was widely known as a rebel leader. Two cherished objects, which the boy Dimitris took with him when he returned to Mozambique from Egypt, were a bayonet and a flintlock pistol which belonged to two rebel relatives.��Tsafendas���s��own father, though he did not participate in war, was an instinctive revolutionary, an anarchist at heart and a prominent member of the Italian anarchist movement while he studied in Padua. Michalis spoke often to his first-born son about independence, social justice and his family���s famous forebears.��Tsafendas��grew up dreaming that one day he would be a rebel, too.

Michalis���s surname was officially��Tsafantakis��and this infuriated the young Dimitris. The original name was in fact��Tsafendas��but the Ottoman occupiers had ordered that the suffix ���akis��� be added to Cretan family names. This was intended to belittle them since ���akis��� at the end of a name meant ���little boy.�����Tsafendas��found this deeply offensive and akin to black slaves in America being given names by their owners. He urged his father to change his name back, but Michalis argued that such a procedure would be overly complicated since the family was recorded as��Tsafantakis��in all official documents. However, when Dimitris grew up, he changed his name back to��Tsafendas.

Dimitris Tsafendas at top with his step sister Evangelia, step-sister Katerina, step-mother Marika and step brother Victor (left to right). Image courtesy Mike Vlachopoulo.

Dimitris Tsafendas at top with his step sister Evangelia, step-sister Katerina, step-mother Marika and step brother Victor (left to right). Image courtesy Mike Vlachopoulo.While��Tsafendas��was in custody, the South African police questioned��about��150 people from South Africa, Mozambique and Rhodesia who had met��Tsafendas. To their horror, the security forces discovered that��Tsafendas��was a former member of the South African Communist Party and that he had a long history of political activism. This included fighting with the Communists during the Greek Civil War; being arrested and imprisoned twice in Mozambique and twice more in Portugal because of Communist and anti-colonialist activities in Mozambique; being a member of the British anti-apartheid movement in London, where he associated with Tennyson��Makiwane, the ANC���s representative there; being exiled for 12 years from Mozambique and being banned from South Africa since 1942 because of his political activities in both countries. Among the 150 questioned was Edward Furness, a South African citizen who had met��Tsafendas��in London six years earlier. He informed the police that��Tsafendas��once told him he was willing to do ���anything that would get the South African regime out of power.��� Other evidence included a submission to a subsequent Commission of Enquiry into Verwoerd���s death that, also in London,��Tsafendas��tried to ���recruit people to take part in an uprising in South Africa.��� Further, two witnesses, Nick��Vergos��and Father Hanno Probst, had reported��Tsafendas��to the South African police as, respectively, ���the biggest Communist in the Republic of South Africa��� and ���a Communist and a dangerous person.��� This was about a year before the assassination.

Anxious to learn more about��Tsafendas���s��activities in Mozambique, the South African police asked the Portuguese security police (PIDE) for any information they had about��Tsafendas. PIDE were uncomfortably aware that a Portuguese citizen, who was a Communist with a long history of political activism, had killed the South African prime minister. Even more embarrassing, they had been tricked by��Tsafendas��three years earlier into granting him an amnesty when he claimed to be a reformed person, a loyal Portuguese and no longer a Communist or anti-colonialist. Thus,��Tsafendas��was allowed to return to Mozambique after twelve years and numerous rejected applications to be allowed to reside in the country where he was born. For these reasons, PIDE decided to downplay��Tsafendas���s��political activities and even omit some of them. Two days after the assassination, PIDE in Lisbon instructed its counterparts in Mozambique that any ���information indicating��Tsafendas��as a partisan for the independence of your province should not be transmitted to the South African authorities, despite the relations that exist between your delegation and the South African police.��� To make sure there would be no slip-ups, PIDE sent their Mozambique colleagues a report on��Tsafendas��which sanitized his political career, omitting several of his known activities.

[image error]PIDE���s order that ���information indicating Tsafendas as a partisan for the independence of your country should not be transmitted to the SA police.

As the police pursued their inquiries in and beyond South Africa, their colleagues in Cape Town tortured��Tsafendas��on a daily basis. Beatings and electric shocks escalated to dangling his body out of a high window and threatening to let him fall. Worse still were the mock hangings. The routine was to put a bag over��Tsafendas���s��head, place a noose around his neck with the rope looped over a beam and make him stand on a chair. They would then kick the chair away.��Tsafendas��would be left hanging and choking for long seconds before his captors released the rope and his body crashed violently to the floor. This terrifying routine convinced��Tsafendas��that he was not going to get out of there alive, that he would be hanged and the police would claim he had committed suicide. He believed that was what happened to David Pratt, the man who had shot Verwoerd six years earlier.��Tsafendas��was not afraid of dying, but he feared a brutal death, lacking in dignity and shrouded in lies. It was apparent to him that the only way to get out of Caledon Square Police Station was as a crazy man. The question was crazy and alive or crazy and dead? He chose the first option: he would pretend to be mad in order to escape death.

The proceedings whereby��Tsafendas��was accused of murdering the prime minister proved more of a show trial than an actual trial. Five psychiatrists testified, four for the defense and one for the state, accompanied by a psychologist for the state and one for the defense. All of them found��Tsafendas��to be a schizophrenic who believed he had a living worm inside him. They based their diagnoses entirely on what��Tsafendas��told them, without looking at any other evidence such as his criminal or medical records, or by talking to people who knew him. Dr Cooper, the defense���s main witness testified that, ���I made a diagnosis of schizophrenia on the basis of my interviews with him [Tsafendas], but in order to try and add either supportive or negative evidence towards this diagnosis, I felt it essential to elicit a history from him and try and decide whether the history I obtained from him was consistent with my impression of him suffering from schizophrenia.���

Dr Macgregor, another psychiatrist for the defense, told the court: ���I thought I had to���time was a little bit precious���I had to take shortcuts. I accepted what was given to me about this man���s life history, various dates and to which countries he had been.��� Mr Reyner van Zyl, the defense���s psychologist, told me in a personal interview that all the background information which the medical experts got about��Tsafendas��was given to them verbally by the police and the defense lawyers. He said, ���We were told, or I was told, the group of guys that examined him, that he had been in various mental hospitals all over the world… we were given this information, that he was a disturbed, schizophrenic man. And that was the background that we had available, and nothing else. The third part [the medical reports] was given to us almost in summary: He has been to this hospital, that hospital, that hospital… I think three or four were mentioned, various hospitals overseas.���

“I was a communist.”

“I was a communist.”Apart from the scientists, a few people who had contact with��Tsafendas��in various situations testified in the court, but their evidence was largely manipulated or misrepresented to present a negative picture of the man. Apart from Patrick��O���Ryan��and his wife, Louisa, who knew��Tsafendas��well, the witnesses had experienced only minimal contact with��Tsafendas��and hardly knew him. One of them was James Johnston, who had spoken twice in his life to��Tsafendas��for a total of 20 minutes. The most absurd testimony came from Peter Daniels. Daniels���s sister, Helen Daniels, a minister of the Christian Church, a sect of which��Tsafendas��was a member, had testified to the police that��Tsafendas��was recommended to her by members of their sect as an ideal husband. She had subsequently written to him asking him to marry her. She wrote to him four times and even sent him her photograph.��Tsafendas��replied to her letters, but said that he wanted to meet her first before committing to marry her. By arrangement, he lived in Helen���s house, where her parents also lived, for about a month. In the end, nothing came of the relationship, since each seems to have been disappointed with the other when they met face to face. Helen Daniels testified to this effect when questioned by the police and��Tsafendas��told them exactly the same thing. Both statements were in the hands of the attorney-general, Wilhelm van den Berg, who was also acting as public prosecutor at the trial. Contrary to what his sister and��Tsafendas��had said, Peter Daniels claimed that��Tsafendas��had turned up at their house uninvited, forcing himself onto them, and was only allowed to stay out of humanitarian reasons. He also testified that��Tsafendas��had pursued his sister and not the other way around. Although van den Berg was aware that these were all lies, he did not challenge Daniels with his sister���s statement and allowed a highly inaccurate and negative picture of��Tsafendas��to prevail. This was not the only time that the attorney-general failed to challenge a witness when he had evidence to break down��his��testimony. Time after time, with witness, after witness, including the medical experts, van den Berg ignored the plethora of evidence in his possession that gave the lie to the inaccurate portrait of��Tsafendas��that was being formed in the court.

Van den Berg also lied flagrantly to the media. On the 3rd of October��1966, he had written a memorandum stating that ���Demitrio��Tsafendas��admitted that he had joined the Communist Party shortly before World War II.��� Then, on the 30th of October,��ten days after the trial, he contradicted himself. A reporter for��The Post��asked van den Berg whether he knew that��Tsafendas��was a former member of the SACP. He replied: ���This is news to me. I certainly had no knowledge of it until this very moment when you brought it to my notice.���

The subsequent Commission of Enquiry into Verwoerd���s assassination also went to extreme lengths to picture��Tsafendas��in an unremittingly negative light. There was no mention of his years of political activism, his well-documented hatred for apartheid and his hope, delivered to the police themselves, that with Verwoerd gone, this racist policy would sooner or later collapse. Instead the Commission���s report portrayed the assassination as a non-political event, almost an accident, caused by an insane man. In this way, it sought to discourage any suspicions that serious opposition could exist to the apartheid regime or that Verwoerd was any other than a beloved leader of all the peoples of South Africa. By portraying��Tsafendas��in an entirely negative light, it also aimed to ensure that the public would feel no sympathy for him.

To achieve this, the Commission, just like the Attorney-General, chose to manipulate and present evidence that supported its stance and ignore that which did not. A breakdown of testimony made by the 200 witnesses who were interviewed by the police and the Commission showed that 44 made positive statements (22%) about��Tsafendas��or his character and 6 (30%) made negative statements. However, the Commission used only 1 of the 44 positive statements (2.2%) but all 6 negatives (100%). Asked about his mental state, only 4 of the 200 (2%) thought there might be anything wrong with��Tsafendas��and the Commission presented 3 of these 4 views (75%). On the other hand, 51 witnesses (25.5%) held the opposite opinion, that there was nothing mentally amiss with��Tsafendas��(the rest made no comment, presumably because��Tsafendas��seemed perfectly normal to them or they would have mentioned it), but the Commission used only 6 (11.7%). Overall, the Enquiry omitted about 90 per cent of positive evidence available to it concerning��Tsafendas���s��character and mental state.

Tsafendas in an identification parade shortly after the assassination. Image courtesy Liza Key.

Tsafendas in an identification parade shortly after the assassination. Image courtesy Liza Key.Tsafendas��was found unfit to stand trial for Verwoerd���s assassination, but instead of being given hospital care, as was his right, he was taken to Robben Island and a few months later incarcerated in Pretoria Central Prison. For much of this time in both prisons, he was subjected again to serious torture and constant humiliation. After the democratic elections of 1994, he was transferred to Sterkfontein, a psychiatric hospital in Krugersdorp. Jody��Kollapen, a High Court judge in Pretoria, but then a young lawyer of the organization Lawyers for Human Rights, campaigned at length for��Tsafendas��to be freed. However, this did not materialize due to the unwillingness of his family and of the local Greek community to care for him after his release. In 1996, Krish Govender, a lawyer from Durban and future��co-chairman of the Law Society of South Africa, made a submission to the TRC that��Tsafendas���s��circumstances should be ���reviewed and investigated.��� However, the TRC took no action in his case.��Tsafendas��died in 1999 and after a pauper���s funeral, he was buried in an unmarked grave.

In April 2018, a report I wrote about these events was submitted to South Africa���s Minister of Justice. It was nearly 2,200��pages long, including about 12,000 pages of documents located in the National Archives of South Africa, Portugal and England, a further 137 interviews, including 69 with people who knew��Tsafendas��personally, and thousands of newspaper articles. Five prominent South African jurists collaborated with me in the evaluation of the evidence and of the report; they were Advocate George��Bizos, Professor John��Dugard, former KwaZulu-Natal State Attorney Krish Govender, Advocate��Dumisa��Ntsebeza��and former Judge Zak��Yacoob. I also consulted a number of leading forensic psychologists and psychiatrists from the United States and South Africa. In a joint letter, accompanying the report, the judges wrote��the new evidence:

[S]hows convincingly that��Mr��Tsafendas��was not a schizophrenic who believed that his actions were determined by a tapeworm. In fact, the study compellingly demonstrates that he was a man with a deep social conscience who was bitterly opposed to apartheid and viewed Verwoerd as the prime architect of this policy.��Tsafendas��told the police after the assassination that he killed Dr Verwoerd because he was “disgusted with his racial policies” and hoped that “a change of policy would take place.” The killing of Verwoerd was therefore a political assassination and not the act of an insane man.

Tsafendas��was indeed a freedom fighter and a hero.

January 29, 2019

The war on women and children in South Africa

Image credit Federico Moroni via Flickr (CC).

Thousands of women throughout South Africa participated in the��#TotalShutDown��marches��in August 2018��to draw attention to what the mainstream media has described as ���the war on women.�����The nation-wide grassroots mobilization has been distinctly feminist, articulating��anti-patriarchy sentiments. What challenges need to be confronted in order to affirm South African women���s rights��to safety, security and equality?

Gender-based violent crimes within families,��communities��and society at large��have��been increasing at an alarming rate.��The statistics are grim,��with��one��in��two��women predicted to experience some form of violence within their lifetimes.��Over time the South African government has drafted various pieces of legislation and policies to address violence against women.��Although��acknowledged for creating an infrastructure to enable effective��support��for women, there is currently much criticism of state institutions for��poor��interventions, few prosecutions��and inadequate implementation of policy.

In��the��organized waves of��protest against male violence, it is important to reflect on what the state offers, why it��consistently fails to deliver��and what��could be put in place��to make its programs work. The following��South African��legislation in some way��addresses��gender violence in the country:

The��Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996.��Chapter two of the South��African��Constitution,��the Bill of Rights, protects��the rights of all��South Africans.��These��include the rights to equality, dignity��and��freedom��from all forms of violence,��maltreatment, abuse��and��exploitation��while having��access to justice��and fair treatment (amongst others).

The��Domestic Violence Act��(DVA)��Act 116 of 1998��was��intended��to provide victims of domestic violence��with��protection from abuse.��The DVA��takes��account of��the variety of family and co-residential relationships existing in South Africa within which violence can occur.

The��Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act, Act 32 of 2007.��This Act is more specific than the DVA in��that��it defines rape, sexual assault, compelled rape or sexual assault, and the compelling of persons older than 18 years to witness a sexual offense.��All the aspects of��gender-based��violence��referred to in the Sexual��Offences Act��are covered in the Domestic��Violence��Act, with the��main��difference being the relationships between��victims and perpetrators.��The DVA��refers��to�����an intimate relationship�����whereas this does not have to be the case under the Sexual��Offences Act.

Activating the legislation to empower victims of abuse

In order to effectively enact the various pieces of legislation,��The National Policy Guidelines for Victim Empowerment��(NPGVEP)��were��developed to ensure a co-ordinated, multi-sectoral and departmental approach to��addressing the needs of victims (women, domestic violence and rape survivors, abused children, abused elderly people, abused people with disabilities, victims of trafficking,��farmworkers and others). Based on these identified groups, the��NPGVEP��also invoked��a number of Acts and Guidelines��such as��the��Constitution, the��DVA,��the��Children���s Act, Act 38 of 2005, and international frameworks such as the��United Nations Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power��and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

These guidelines determine which��national��government departments, civil society��organizations,��and��academic and research institutions would��play a key role��and work together��to ensure effective implementation and��thereby��empower��survivors of violence.

Several departments��and government entities��now comprise��the core of the Victim Empowerment Management Forum. They are��the��Department of Social Development (DSD), which is the lead and co-ordinating Department,��the��Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DoJCD), the��South African Police Services (SAPS),��the��Department of Correctional Services (DCS),��the��Department of Health (DoH),��the��Department of Education��(DoE),��Provincial Victim Empowerment Program��coordinators from provincial��Departments��of Social Development��and relevant civil society��organizations, academic and research institutions.

The NPGVEP was followed by the��National Policy Framework: Management of Sexual Offence Matters,��which attempted to enhance��its��effectiveness. In addition to the victims of violence identified by the NPGVEP,��the framework��importantly��added��Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) persons,��immigrants and refugees, and awaiting-trial detainees and incarcerated offenders.��The��additional��entities��that then became relevant��were��the��National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), the��Department of Women, Children and Persons with Disabilities (DWCPD), the��Department of Basic Education (DBE),��Legal Aid of South Africa��and the��National House of Traditional Leaders (NHTL).

Since��the DWCPD��was dissolved,��and the Department of Women (DoW) within the Presidency��was��established,��it can be assumed that this would now fall to��the��Department of Women, although��this is��not indicated on��its��website.��The��various pieces of legislation, policies��and treaties provide an armament of strong protection for abused women and children��irrespective of social background, nationality or sexual orientation. Yet,��as the��protest��marches��suggest, good policy if not effectively applied��becomes inconsequential. What challenges��then do victims of gender violence��face when��reporting��cases,��charging��perpetrators��or seeking��protection?

Challenges facing the implementation of acts

Socio-cultural��and��political��discourses:��Although��it is reasonable to assume that there is often a lag between��drawing up��Acts and their implementation, action is often��weakened��by prevailing��socio-cultural��practices��and��political��discourse.��Although��2018��marked��20 years of the��Domestic Violence Act (Republic of South Africa, 1998),��there��were��media reports��on the��complicity��of��some��senior��state officials in��sexist stereotyping or��acts of violence against women (including��their��intimate partners).��Reporting of violence has��thus��been inhibited by a��social environment��in which��hegemonic male-dominated��systems��and discourse��persist and where��women��are frequently��blamed��for their own abuse. The��lack of empathy��and��support��adds to their trauma.��The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW��recommended��adopting��measures��to��begin��a dialogue about��socio-cultural��practices��and institutions that��perpetuate��prejudices,��misogyny, heteronormativity��and��gender inequality.

Strains of the��family��context:��The family��has become the site��of��extremely��violent��incidents��in��South African society.��Studies by the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation��show that more than 50% of��women in��Gauteng��have��been victims of��violence with about 80% of men in these studies admitting to being violent towards a partner. Married women��are at��particularly��high-risk��category��for��domestic��violence,��with 83% of abused women having children living with them at the time of their abuse.��However, while the site of violence is often��within the parameters of��family��life, there is often reluctance to move beyond the family to seek recourse. Family interventions��commonly��represent��attempts to��keep partners together��and not��to give��an��abused��spouse��the option of��moving��into an autonomous safe space. Compounding this are religious leaders who offer advice��that maintains patriarchy, encouraging wives to forgive perpetrators,��drawing on��the��scriptures asking��both women and men to��change and��to accept the status quo.

Inadequate��responses of��service��providers:��It is often the case that abused women feel��stigmatized��and aggrieved by the dismissive attitudes of service providers. When reporting abuse at a police station,��they��face��poor service, long wait��times��or��insensitive questioning by��members��of the��police service.��The��Tshwaranang��Legal Advocacy Centre (2009) found that the police were��usually��either not recording domestic violence��or��were recording it but��in a domestic violence register��as��required by��the��DVA.��Poor��data capture��has led to��perceptions��that domestic violence and rape have��in fact��declined. The police��have also been found to be��non-compliant in serving notices and warrants on perpetrators. Additionally,��those in breach of protection orders��are often not arrested.��A common��reason cited��is��that offenders��cannot be��easily traced.��Apart from the police, clinic and hospital��health workers are��often described as extremely��unsympathetic��and highly judgmental. This is particularly the case when healthcare workers come from the same cultural traditions��as the victim��and are��themselves��survivors.

Misdirected and��insufficiently��trained��officials:��All state-run��structures are performance-managed and��thus��accountable for productivity and delivery.��Striving to show competence and good annual practice is being linked to periodic declarations by the��South African Police Services (SAPS) that rape,��femicide��and domestic violence in the country (or parts of the country) are in decline.��Officials��often find themselves pressurized to��make claims that��levels of��gender-based violence��are under control or��have��dropped in��their constituencies.��The��SAPS performance indicators��show a��reduction in the number of rape cases reported (South African Police Service, 2014). This illusion of a decrease in sexual offenses and domestic violence would��in turn��reduce the focus��on,��and funding of,��gender-based violence��interventions.��Financial support for the NGO-sector and for shelters have been cut,��as more funds��are��diverted towards government departments�����marketing and campaigns on gender-based violence. It would be useful if more funds were��invested in training and��maintaining��specialized and dedicated staff in the��national police service,��the��National��Prosecuting��Authority��and��Department of Health. Police officers are often untrained, unable to interpret the law adequately,��or correctly collect and��use medico-legal evidence.��This��results in postponement of proceedings and the mishandling of cases.

Lack of��coordination��and��leadership��issues:��A lack of coordination between different departments has a bearing on what is delivered and in particular on whether perpetrators are apprehended and brought to court. Thus, in the event that a woman reports her husband as an abuser, she has no guarantee��that she��(and her children)��will receive protection��and��counseling, that he will face��legal and correctional��consequences,��and��that the violence will end. For this to happen,��coordinated action of the��police,��department of health, social development, the national prosecuting authority��and possibly��victim��empowerment��programs��is��required. A��2015 Soul City study��highlights��the��problem of��duplicate��mandates and confusion of roles,��which��negatively affects implementation of the DVA.��There is��also��a high turnover of key officials;��often effective��agents��are replaced by less effective and��unskilled functionaries. With��this may come a loss of institutional memory and a growing cohort of leaders��who��may��not have independent track records or��credibility.��Internal dynamics and egocentrism may lead to attempts to wipe out previous managers�����legacies and go back to the drawing board to build new and possibly less-effective approaches.��Lack of��strategic��assessments and evaluations��of the performances of programs and departments undermine the potential positive effects of the��Domestic Violence��and Sexual Offences Acts.

Necessity for��shelters and��post-shelter��services:��A lack of��government��funding has offered fewer prospects for new shelters to be built, particularly in the rural areas, or for the existing shelters to be properly��maintained.��In��a study��on shelters in South Africa,��Kailash��Bhana, Claudia Lopes and Diane��Massawe��suggest that��although shelters offer a space��in��which women can make life-changing decisions, it is often a struggle to get the state to pay to keep them functioning and optimally serviced. While accepted globally as a vital��crisis-intervention��step towards emancipating��abused women,��they are yet to be acknowledged by the state as essential for saving the lives of women and their��children. Evidence shows that children exposed to violence at��a��young age experience depression, withdrawal and other��behavioral��problems, and if uncounselled may��have a high likelihood of��living out troubled, anti-social adult lives.��Thus, follow-up programs��catering��for the needs of women and their children are important to keep them safe and stress-free. This may include assistance in finding employment, skills-upgrading, educational needs, advice on how to gain access to legal aid,��counseling��or specialized health care. The move to the shelter represents a break from the family and the cycle of abuse. Arguably, in South Africa the tendency is to seek to reconcile the abused woman with her violent partner. Where men have not faced any consequences, the return home usually��results in repeated��exposure to violence.

Absence of a��feminist-informed��political��will:��South Africa is currently described as the rape capital of the world, with overall levels of gender-based violence akin to a country in a state of war. The��#TotalShutDown��marches��represented a historic moment for��women��working to bring��gender-based violence to an end.��With the slogan�����enough is enough�����shouted across the length and breadth of the country,��the��campaign��has��highlighted the need for collective action, for strong leadership, for��raising awareness��about the��statutory��Acts that are intended to protect women and for the perpetrators of domestic violence��and rape to be apprehended��and sentenced. With a specifically feminist agenda, the call��has been for a strengthened political will���and for the President himself to��influence change and��to��listen to��the voices of women.��The point about��the ���entrenchment of patriarchy�����(Bennett, 2001:90)��and the difficulties entailed in dislodging��such an amorphous edifice��have��been��raised for the��past��few decades.��A��feminist-informed political��will��can��confront��patriarchy��at every level,��whether in��the home, the workplace, on campuses��or��in public arenas.��Such resolve can��potentially��transform attitudes and��behaviors, rally progressive men��into supportive action,��and keep state officials accountable for how they��attend to, and��serve the interests of,��abused women.

Conclusion

While it can be shown that the infrastructure of��available��policy is strong, the persistence of gender-based violence highlights��the barriers to implementation that need to be addressed. Since most violence��against women emanates from within the private politics of family life, there need to be mechanisms and interventions that draw out these private, intimate and familial conversations into the public domain. In doing so, however, socio-cultural and political discourses will need��continuous��tackling.��Re-training of service-providers��and getting the police to deal decisively with��apprehending offenders and recognizing��gender-based violence��as a human rights violation would be��a good beginning.��More funds need to be invested in��the��provision��of��shelters. Coordination between departments���perhaps driven via a dedicated coalition of cadres with a coherent game plan���is critical and needs��support. Above all, an invigorated feminist-informed political will needs to��spread��from��civil society��to the upper echelons of the state.

January 28, 2019

What is this ‘New Uganda’?

Image credit Future Atlas via Wikimedia Commons.

For the last three decades, Uganda has been one of the fastest growing economies in Africa. Globally praised as an ���African success story��� and heavily backed by international financial institutions, development agencies and bilateral donors, the country has become an exemplar of economic and political reform for those who espouse a neoliberal model of development. The neoliberal policies and the resulting restructuring of the country have been accompanied by narratives of progress, prosperity and modernization,��and��justified in the name of development. But this self-celebratory narrative, which is critiqued by many in Uganda, masks the disruptive social impact of these reforms, and silences the complex and persistent crises resulting from neoliberal transformation.

Those who want to better understand the dynamics of contemporary Uganda thus face a bifurcated scenario: two different narratives persist at global and local levels that seem, taken together, hard to reconcile. One is of a Uganda emerging from years-long civil war in the late 1980s, and then within a few years becoming an international success story. This ���Uganda as a success��� narrative praises the post-1986 policy reforms that have stimulated economic growth, with sustained GDP growth and foreign direct investment (FDI) attraction matched by steady progress in poverty reduction and gender empowerment.

Central to this narrative is the leadership of a president who is a progressive modernizer, acting with the interest of the nation at heart. In short, Uganda has never been better. Such accounts parade all manner of positive achievements in social, political and economic spheres. Very powerful actors promote this narrative, year in, year out: from the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and various international and bilateral donors of the country, to influential international and domestic scholars and analysts, not to mention the Ugandan government and establishment. The same actors have produced a plethora of official statistics and econometric studies that supposedly provide evidence of this stated steady progress. A prime example of this celebratory narrative about the new Uganda is the Kampala speech of the IMF Managing Director, Christine Lagarde, in January 2017, ���Becoming the Champion: Uganda���s Development Challenge.”

Lagarde states: ���This gathering provides an opportunity to congratulate Uganda for its impressive economic achievements… I do not normally begin my speeches with statistics, but today will be an exception. That is because the numbers tell us a great deal.��� After reciting the country���s official figures concerning GDP growth and poverty reduction, she concludes: ���This is an African success story.��� Another exemplar is a recent speech by the UN Resident Coordinator and UNDP Resident Representative in Uganda, Rosa Malango, who boasted thus: ���Uganda is widely recognized for producing a wide range of excellent policies on social, economic and development issues.���

Lagarde made her visit just months after the highly controversial 2016 political elections that were accompanied by repression against sections of the opposition and critics of the government, as well as accusations of substantial and outright vote rigging. The outcomes of the 2016 elections further deepened the government���s legitimacy crisis. This leads us to discuss the second narrative about contemporary Uganda: here, there is talk of OR the focus is��on,��a patrimonial mode of rule supported by the president���s ruling group. This formation uses state power to advance private economic interests and functions through a far-reaching business and political network, which includes the president���s extended family, political allegiances and foreign investors. To denounce the self-seeking attitude prevalent in the ruling party, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), Ugandan street politics dubs it the ���National Robbery Movement.���

The state has come to be associated with increasing political repression, a decline in public services and generalized economic insecurity. Public debates refer to mafias, and a mafia/vampire state, a country occupied, controlled and exploited by a tiny clique of powerful domestic actors and their foreign allies. There is reference to issues such as recurring food shortages and chronic indebtedness, and a social crisis characterized by increased inequality, widespread violence and increased criminality, high levels of suicide (especially among the youth), poverty-driven deaths, preventable illnesses and generalized destitution. This second narrative of ���Uganda in crisis��� is articulated by the people on the street, sections of the political opposition, the media, NGOs, the religious community and a range of critical national commentators. One can listen to it on TV news and debates, in churches and mosques and read about it in media articles and on social media platforms, or in academic research and NGO reports about state violence and repression, corruption and land disputes.

Our recently published edited collection, titled:��Uganda: The Dynamics of Neoliberal Transformation��(ZED 2018; see for free introduction��here)��intervenes in this crucial debate about the character and trajectory of change in contemporary Uganda, about what constitutes the New��Uganda.��It confronts the often sanitized and largely depoliticized accounts of the Museveni government and its proponents. It questions mainstream narratives of a highly successful (and socially beneficial) post-1986 transformation, and contrasts these with empirical evidence of a prolonged and multifaceted situation of crisis generated by a particular version of severe capitalist restructuring, or neoliberal reforms. This analytical approach has, to date, occupied little space in the context of neoliberal academia. We thereby also sought to challenge the decades-long ideational and discursive hegemony of powerful international and national reform designers, implementers and supporters. We critique and challenge what Ngugi��wa��Thiong���o��calls, with reference to the European colonialism in Africa,�����mental domination������a domination that is so characteristic of neoliberal social order across the contemporary “free world”:�����Economic and political control can never be complete or effective without mental control.�����As thinkers from Luxemburg to Orwell noted, contesting the��truth of the ruling classes, pronouncing what is going on and offering alternatives to establishment accounts of reality (and thereby history), is a crucial political act.

As a collective of 25 scholars, we��wanted to map, understand and explain the key features of both the��making��and��operation��of neoliberal-capitalist Uganda, against the political-economic and socio-cultural context of this particular society. A major question we wanted to address was: by whom, why, how and to what effect was Uganda transformed in all the different societal realms? Moreover: What does 30 years of neoliberal reform and transformation do to a particular society? What is the New Uganda, the new neoliberal-capitalist market society, all about? What are its characteristics? What does the data and analysis in the altogether 19 chapters enable us to see, argue and for now conclude about this march towards a more fully-fledged, specifically institutionalized capitalism, in this particular site of the global political economy?

When we began this work, as editors we felt that there was little scholarship available on Uganda that gave neoliberalism the analytical seriousness and treatment that an empirical phenomenon of this size and relevance deserves. Social sciences scholarship on Uganda, for reasons explained in the book, has to date not sufficiently analyzed the many characteristics of the all-encompassing process of change triggered by neoliberal reforms. And yet of course, Uganda is a special site for such an analytical undertaking: the country is a hotspot of capitalist restructuring, transformation, contradiction and crisis, past and present. And, it has a peculiar mix of capitalist political-economic specifics. It is a peripheral, donor-dependent country, subject to imperialist dynamics. Inequality and poverty are rampant, society is dominated by violence and conflict, to which militarism adds its weight.

Indeed, Uganda is a prime example of neoliberal restructuring in Africa where the neoliberal project does not seem to have been significantly challenged so far. The key processes and practices underpinning social transformations in the country are not unique to Uganda. Several African countries have in many ways undertaken similar paths of political, social, economic and cultural transformation. Yet the spectacular transformations that have occurred in the country in the last 30 years reveal the potential trajectories of transformation upon which other African countries could embark in the near future, or that are already underway there. The prevalence of extractive and enclave economies, the hegemony of a state-donors-capital block, and the expanding marketization of society, represent the common denominator for many African countries.

The version of neoliberalism observed in Uganda is in key aspects arguably more extreme, crass and unequal than some of the neoliberal societies elsewhere. Analytically crucial: the exclusion, inequality, violence, precarity and crises that large sections of the subaltern face are��thus, the book shows, not caused by a malfunctioning market, or a deviated capitalist trajectory. Rather the opposite is true: it is precisely the functioning of neoliberal restructuring and institutions that causes widespread social, political, and economic crises. Mainstream narratives claiming that more private sector development will produce a future that is, as Museveni put it in a recent twitter tweet, ���easy to handle,��� are a fallacy. Current in-crisis countries, such as Mexico, once celebrated success stories of neoliberal restructuring, are telling cases of its regressive outcomes. Uganda, as other��neoliberalized��countries in Africa and elsewhere, could go down a similar path, breeding a future of permanent social crisis.

Now that the book is out, we actually feel that there is the necessity to expand such a handbook-length treatment of neoliberalism to other African countries to get a more adequate data overview and analytical grip of the phenomenon. In other words, the specific declination of contemporary capitalism, which is neoliberal capitalism, is actually understudied when it comes to African countries. Other frames dominate the social sciences, also because of the political economy of research funding in the country, for instance the role of donors from the capitalist North. Given the heft of the analysis that this collective of scholars has offered in our collection, we believe that a much more collective and focused, as well as continuously critical and innovative analysis is needed in future to cage, look at, touch and make sense of the ���beast��� (capitalist social reality) and to resist and��counter��hegemonic forces and their account of reality.

January 27, 2019

This is what a neoliberal trade union looks like

Image credit Kyle Gman via Flickr (CC).

In July 2018, the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ), the largest and oldest of Zambia���s mining unions, held its 14th quadrennial conference and elections.��Union elections in Zambia are typified by allegations of corruption, but not these.��After serving two terms as the union���s General Secretary, Joseph��Chewe, was elected unopposed as union President. His long-term Deputy, George Mumba, became General Secretary and��Chishimba��Nkole,��former MUZ president��remained as��Zambia Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU)��president.��The other two mineworker unions,��the National Union of Mine and Allied Workers (NUMAW) and the United Mineworkers Union of Zambia (UMUZ) also held national elections in��2016��and 2017, and re-elected their respective leaderships.

After almost a��generation of instability, the last five years have arguably been a period of success for these mineworker unions. Stable leadership has coincided with a reduction in the substantial debts of each union, with MUZ going from near receivership to annual profitability in ten years. More importantly, after the number of unionized miners fell to below 20,000 in the early and mid-2000s (from a peak of 65,000 before privatization), it has reached about 30,000 across the mining unions. Much of this growth in membership has come from unionizing sub-contracted miners, whose contract precariousness had previously been seen as a potential deathblow to a union movement structured around well-paid permanent workers.

However, the stabilization of Zambia���s mining unions��has been intimately tied to an increasing focus on profit-generating businesses, at the expense of collective action. Union businesses are located on company property and require licensing from the government. Each union operates stores at the worksite and��in town, selling essential commodities on credit to their members at a high mark-up. As payments are deducted from payroll (to reduce defaults) the unions need their employers��� cooperation for this system to continue. MUZ also owns a busing company that is contracted by the mines to transport workers (MUZ members) to the worksite and a mealie mill plant that has been made viable through subsidized maize and soft loans from Zambia���s government. Across each of the unions, these businesses are providing funds��that compensate for the decreased dues that lower salaried workers are contributing,��and the increased administrative costs of unionizing small groups of subcontractors. Dependence on these new sources of income has reduced militancy and is a liability during daily interactions with the companies.

Many underground miners who are members of the union are beginning to question the relevance of the union to workers��� rights. As one machine operator asked ���what interests do the unions in the mining sector serve?��It appears to me that they are more interested in business ventures than workers��� concerns.��� Thus, members move from one union to the next hoping that the other union might serve them better only to discover that all unions offer the same kinds of services. Other members were concerned about the close business relations that unions have with banks and the mining companies. For every loan that is given to a mine worker by the bank, the union is given a commission. Yet this cost is passed on to the worker/member who suffers high interest charges and long repayment periods. At one of the mining companies, about 78 percent of general payroll employees had loans with commercial banks. In a context where retrenchments are frequent, and banks recover their loans from retrenchment packages, many retrenched miners have lost their entire packages. According to the Ex-Miners Association��of Zambia EMAZ), an association that provides financial support for and lobbies government on behalf of retrenched miners, in 2015 alone, over��85 percent of the retrenched workers lost their packages through loan recovery from banks.

The unions��� changing emphasis and structure has been a relatively deliberate response to Zambian neoliberalism, aimed at mitigating, rather than challenging structural change. The presidents of the three mineworker unions mentioned earlier see their increased reliance on business as necessitated by mechanization, casualization, and feckless international investors. Mechanization is particularly troubling. Senior unionists see a time when there are a few thousand long-term jobs in the mining sector and are attempting to prepare the union for that.��This creates many questions about what the mining unions��� purpose will be if there is no mining workforce.

Recent debates on trade union militancy advocate for social movement unionism���the idea that trade unions need to work closely with other like-minded civil society organizations, combining workplace issues with broader political issues in order to be relevant. The��major problem, however, has been that unions in the mining sector find it appropriate to align with the ruling political party than with other civil society organizations. Each of the three unions holds an official policy of “working with the government of��the day.” At both MUZ and NUMAWU���s quadrennial elections, members of government were invited, who warned miners against militancy that targeted either the companies or government. When civil society organizations are protesting against issues such as abuse of government funds or corruption, the union encourages its members not to be involved in politics. In an interview with some union leaders, most argued that ���it is impossible to work with civil society organizations because they are very political.��� This view clearly demonstrated that the unions in Zambia still see engaging in political and governance issues to be beyond the scope of the unions.

The combination of a mechanizing workforce and wealthier apolitical unions creates new questions for those who hope social alliances with social movements will re-empower unions in southern Africa. It represents a near direct contrast to��Pnina��Werbner���s��description of Botswanan unions engaging in widespread mobilization of civil society associations that supersedes the notion of class identity. There are valid questions as to how Zambia unions can be involved in such civil action, not only due to their��current entanglements with the��government and companies, but also because class identity is so key to Zambian miners��� lived experiences. Alternatively, the unions��� growing financial clout has the potential to enable greater independence. Many more militant MUZ branch executives see MUZ���s mealie mill sales as potentially supporting a strike fund, subsidizing the costs of unionizing sub-contracted workers or even offering retirement packages (which they increasingly believe neither the government nor companies can be trusted to provide). It remains to be seen whether these (highly leveraged) companies will be a success and��whether��this success will enhance or damage Zambia���s mining unions��� potential to combat injustices in their sector or society.

The growth and stability of business unionism in Zambia

Image credit Kyle Gman via Flickr (CC).

In July 2018, the Mineworkers Union of Zambia (MUZ), the largest and oldest of Zambia���s mining unions, held its 14th quadrennial conference and elections.��Union elections in Zambia are typified by allegations of corruption, but not these.��After serving two terms as the union���s General Secretary, Joseph��Chewe, was elected unopposed as union President. His long-term Deputy, George Mumba, became General Secretary and��Chishimba��Nkole,��former MUZ president��remained as��Zambia Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU)��president.��The other two mineworker unions,��the National Union of Mine and Allied Workers (NUMAW) and the United Mineworkers Union of Zambia (UMUZ) also held national elections in��2016��and 2017, and re-elected their respective leaderships.

After almost a��generation of instability, the last five years have arguably been a period of success for these mineworker unions. Stable leadership has coincided with a reduction in the substantial debts of each union, with MUZ going from near receivership to annual profitability in ten years. More importantly, after the number of unionized miners fell to below 20,000 in the early and mid-2000s (from a peak of 65,000 before privatization), it has reached about 30,000 across the mining unions. Much of this growth in membership has come from unionizing sub-contracted miners, whose contract precariousness had previously been seen as a potential deathblow to a union movement structured around well-paid permanent workers.

However, the stabilization of Zambia���s mining unions��has been intimately tied to an increasing focus on profit-generating businesses, at the expense of collective action. Union businesses are located on company property and require licensing from the government. Each union operates stores at the worksite and��in town, selling essential commodities on credit to their members at a high mark-up. As payments are deducted from payroll (to reduce defaults) the unions need their employers��� cooperation for this system to continue. MUZ also owns a busing company that is contracted by the mines to transport workers (MUZ members) to the worksite and a mealie mill plant that has been made viable through subsidized maize and soft loans from Zambia���s government. Across each of the unions, these businesses are providing funds��that compensate for the decreased dues that lower salaried workers are contributing,��and the increased administrative costs of unionizing small groups of subcontractors. Dependence on these new sources of income has reduced militancy and is a liability during daily interactions with the companies.

Many underground miners who are members of the union are beginning to question the relevance of the union to workers��� rights. As one machine operator asked ���what interests do the unions in the mining sector serve?��It appears to me that they are more interested in business ventures than workers��� concerns.��� Thus, members move from one union to the next hoping that the other union might serve them better only to discover that all unions offer the same kinds of services. Other members were concerned about the close business relations that unions have with banks and the mining companies. For every loan that is given to a mine worker by the bank, the union is given a commission. Yet this cost is passed on to the worker/member who suffers high interest charges and long repayment periods. At one of the mining companies, about 78 percent of general payroll employees had loans with commercial banks. In a context where retrenchments are frequent, and banks recover their loans from retrenchment packages, many retrenched miners have lost their entire packages. According to the Ex-Miners Association��of Zambia EMAZ), an association that provides financial support for and lobbies government on behalf of retrenched miners, in 2015 alone, over��85 percent of the retrenched workers lost their packages through loan recovery from banks.

The unions��� changing emphasis and structure has been a relatively deliberate response to Zambian neoliberalism, aimed at mitigating, rather than challenging structural change. The presidents of the three mineworker unions mentioned earlier see their increased reliance on business as necessitated by mechanization, casualization, and feckless international investors. Mechanization is particularly troubling. Senior unionists see a time when there are a few thousand long-term jobs in the mining sector and are attempting to prepare the union for that.��This creates many questions about what the mining unions��� purpose will be if there is no mining workforce.

Recent debates on trade union militancy advocate for social movement unionism���the idea that trade unions need to work closely with other like-minded civil society organizations, combining workplace issues with broader political issues in order to be relevant. The��major problem, however, has been that unions in the mining sector find it appropriate to align with the ruling political party than with other civil society organizations. Each of the three unions holds an official policy of “working with the government of��the day.” At both MUZ and NUMAWU���s quadrennial elections, members of government were invited, who warned miners against militancy that targeted either the companies or government. When civil society organizations are protesting against issues such as abuse of government funds or corruption, the union encourages its members not to be involved in politics. In an interview with some union leaders, most argued that ���it is impossible to work with civil society organizations because they are very political.��� This view clearly demonstrated that the unions in Zambia still see engaging in political and governance issues to be beyond the scope of the unions.

The combination of a mechanizing workforce and wealthier apolitical unions creates new questions for those who hope social alliances with social movements will re-empower unions in southern Africa. It represents a near direct contrast to��Pnina��Werbner���s��description of Botswanan unions engaging in widespread mobilization of civil society associations that supersedes the notion of class identity. There are valid questions as to how Zambia unions can be involved in such civil action, not only due to their��current entanglements with the��government and companies, but also because class identity is so key to Zambian miners��� lived experiences. Alternatively, the unions��� growing financial clout has the potential to enable greater independence. Many more militant MUZ branch executives see MUZ���s mealie mill sales as potentially supporting a strike fund, subsidizing the costs of unionizing sub-contracted workers or even offering retirement packages (which they increasingly believe neither the government nor companies can be trusted to provide). It remains to be seen whether these (highly leveraged) companies will be a success and��whether��this success will enhance or damage Zambia���s mining unions��� potential to combat injustices in their sector or society.

January 26, 2019

The house of exile

Lusaka, Zambia. Image credit Bengt Flemark via Flickr (CC).

���In exile we only thought about the��Boers. We��never imagined��the houses���what they were like inside��and how it felt to live in one.�����Growing up in exile in Zambia, Kenya, Canada and the United States, a daughter of anti-apartheid freedom fighters, Sisonke��Msimang��knew her country only as a metaphoric war��of ideals.��Always Another Country:��A Memoir of Exile��and Home��(World Editions, 2018)��tells of her��coming-of-age��outside the country,��and her long-awaited homecoming as an adult. On the surface, this��is a celebratory moment:��She��and her��husband buy their first house:�����the walkway (���)��smells like jasmine (���) there is a lovely soft grey marble on the floors (���) a generous veranda runs the length of the house.�����But��she��soon��begins to realize that South African suburbia is ���a place as haunting as it is manicured.��� She is confronted with her identity��without��the Struggle, and the guilt of her position as a member of the��black elite, one��who ���got off easy��� in exile,��begins��to consume her.

Much has been written about the usefulness of exile for intellectual work: Edward Said��described��it as��adopting ���a spirit of opposition, rather than accommodation.�����But what about the houses? What about��the architecture, where the windows are located,��whether there���s a garden, how��the light��streams in? Living in exile seems to raise the stakes of��the domestic, and this is something that preoccupies Baldwin scholar Magdalena��Zabarowska��in her latest biographical study,��Me and My House: Baldwin���s Last Decade in France��(Duke University Press, 2018). Baldwin���s��final resting place, a sprawling stone house in the French village of St. Paul-de-Vence,��transformed him from��a ���transatlantic commuter�����into a homeowner.��The privacy of��this exilic abode,��Zaborowska��shows,��developed in sophisticated dialogue with the ���political house��� he called the United States.��His��sensitivity to interior spaces and the objects in them������he referred to them as ���little gimcracks, like mirrors��and ash-trays���������provides an unexplored dimension to��understanding his role as an interpreter of America, and he ���infused many of his essays with metaphors of domesticity that confirmed his commitment to the private being always political��and vice versa.�����Baldwin��left America���first for Turkey, and then for��France���not only to gain a sharper perspective on it, but also for the creative respite of a ���private life������a life beyond his role as a cipher, a target, or the resident specialist in American race��politics. Outside America, he found this home.

In��many ways,��Msimang���s��story appears as a mirror image of Baldwin���s, which starts in Harlem and��unfolds in the��glimpses of his autobiographical essays.��If Baldwin was��pushed out of America,��Msimang���s��family was locked��out of South Africa, her father having left before she was born,��to be trained outside the country as a member of the ANC���s armed wing.��If��Msimang��gained a home country, she was also bereft of the��ideal of South Africa���a kind of spiritual-political home���with which she grew up.

In light of��Zabarowska���s��study, it���s striking to see��the weight given to domestic details in��Msimang���s��memoir.��In Canada, a��white classmate��walks into the family home,��treading��dirt��into the carpet. She��turns toward the mantelpiece, where rows of photographs show multiple generations of��family and friends. ������Don���t you like even know anyone who isn���t from Africa?��������she asks.�����I had never even thought about it,�����Msimang��writes, ���but now, looking at the house, at our art and our photos, through her eyes, we were different.���

As a child, then,��Msimang��encounters��herself through the eyes of whiteness���a��Fanonian��idea that was��useful��for��Baldwin, who��maintained that, as an identity,��race was��nothing more��valuable��than��a projection��by the white imaginary.��What��Africans and African Americans��held in common,��he��wrote in ���Princes and Powers������is a history of suffering, but this was��no��marker��of cultural unity. They also held in common�����the necessity to remake the world in their own image, to impose this image on the world,��and no longer��be controlled by the vision of the world, and themselves, held by other people.���

While Baldwin left America in order to discover who he was without its racial politics,��Msimang���s��arrival in��South Africa culminates in the loss of all the Others that had defined her identity up until that point���it is a loss of the Other opposite which she was positioned in exile,��whiteness abroad and whiteness at home,��of the South Africa-to-come, which was always a metaphor for redemption.��But it��is also, to some��extent, the��loss of a private life. If the private is political,��in South Africa, the material��private is especially so.��The house in which her family ensconces itself begins to take on a sinister undercurrent, as though haunted by a ghost whose exorcism had failed.��Its��upkeep��begs the labor of other black South Africans, and suddenly she is no longer an innocent������the house has made me complicit.��� Two��women move in to help with��the��housework and childcare.��They watch soap operas together��and ���breathe the same air,��� even as they keep an ���emotional distance��� and ���learn to live with the guilt.�����It is when one of��the women��betrays her that��Msimang��is��forced to��confront her growing disillusionment with the ANC���s entire enterprise.�����Apartheid���s spatial legacies seem to have woven themselves into the most intimate of spaces,��� she writes.�������Dysfunction pulses at every street light and violence seeps under every door.��� The private is political.

But��of course, as Baldwin continually shows, it���s��not that simple.��When��Msimang��inconveniently falls in love with��a white Australian,��she��initially resists.�����I���m stubbornly clinging to a political position I arrived at in the absence of love���when I was in college and charged with a righteousness that was deeply powerful and naively abstract���instead of deciding that it���s more complex than I want it to be.�����Eventually she��decides that��although ���objections to interracial love in a racist��world make sense,�����she��will�����accept the contradictions.�����It is fitting that love is the��area��where��her��politics��ultimately��has no place:��the very element Baldwin invoked when��he spoke about ���private life,�����his��Jamesian��term, Kevin Gaines writes, ���for the interior life that served as the wellspring of his creativity. In a homophobic world, it was also the euphemism he used for his sexuality: a catch-all for��the��immensity���and��the��wealth���of life beyond��the political.

As the young��Msimang��looks at��her classmate��looking at��the objects on��her mantelpiece, we see how the��domestic��is a way��of remaking the world in��her own image, of imposing��this image on the world. Though she��sees, for the first time,��the photos��of�����yellow-eyed grannies who had paid a great deal to have themselves posed, and well-fed black men (���) whose eyes spoke of hard times despite their tight waistcoats and spotless white shirts,��� and��though��the photo of her with her cousins��and siblings��was suddenly just a photo of ���long-limbed Africans sprawled out on a lawn somewhere foreign,��� there is��a hint at��the potential of��these objects��as refuges of dignity. The framed��Heidi Lange batik��had��come ���all the way from Nairobi.���

���We��washed our hands because the world��was dirty and home was clean.���

January 25, 2019

O problema com ‘Black Panther’

Still from Black Panther.

Pantera Negra se tornou um fen��meno cultural sem precedentes na hist��ria recente. Audi��ncias arrebatadoras t��m idolatrado este��blockbuster, remake da hist��ria em quadrinho sobre o super-her��i da m��tica na����o africana de Wakanda.

Assistir o filme tem se sido especialmente cat��rtico para aqueles sufocados pela pol��tica racial americana, com nacionalistas brancos marchando abertamente nas ruas e um governo que parece conspirar para aumentar o sofrimento das pessoas n��o-brancas, o espet��culo de eleg��ncia negra no filme oferece mais do que entretenimento, �� uma fonte de ��guas doces em meio ao deserto.

Dada a escassez de imagens relativas �� afirma����o negra na m��dia popular, o impulso de canonizar o filme �� compreens��vel. Mas Pantera Negra �� mais do que a celebra����o da dignidade negra e sua sofistica����o, �� tamb��m um discurso de liberta����o,��uma paisagem on��rica��baseada nas tradi����es negras de pensar e buscar construir sociedades ideais al��m do alcance da supremacia branca.

Pantera Negra exige uma��leitura��cr��tica porque vis��es ut��picas s��o inevitavelmente pol��ticas. S��o elas algumas das principais ferramentas usadas por pessoas oprimidas para pensar um futuro mais justo. Infelizmente, qualquer pessoa comprometida com um conceito amplo de liberta����o Pan-Africana ��� desenhada para libertar africanos e descendentes de africanos no mundo todo ��� precisa considerar Pantera Negra como uma imagem n��o-revolucion��ria.

Essa afirma����o pode parecer injusta, at�� uma blasf��mia para f��s do filme, porque, apesar de tudo, Pantera Negra apresenta um elenco de personagens negros nobres e complexos (numa sociedade obcecada por pele clara, �� importante notar que o filme oferece um suntuoso desfile de personagens de pele negra retinta).

Wakanda, al��m disso, �� um modelo de autodetermina����o negra, aben��oada com um suprimento inesgot��vel de um mineral valioso conhecido como vibranium. A na����o prosperou por gera����es, escapando da coloniza����o e de outras influ��ncias��perversas, protegida por uma c��pula m��gica que oculta o reino do mundo exterior.

Wakanda �� tecnologicamente avan��ada e povoada por cidad��os orgulhosos e leais, incluindo um regimento de formid��veis mulheres guerreiras.

O problema, do ponto��de vista��progressista,��est�� no nacionalismo conservador de Wakanda. Governantes da na����o rejeitam as sugest��es de que o uso de sua tecnologia possa empoderar outras pessoas negras no continente Africano e ao redor do mundo. Os l��deres de Wakanda mant��m um teimoso isolacionismo, enviando agentes secretos em miss��es��benevolentes��em terras estrangeiras de forma pontual, mas evitando qualquer programa significativo de solidariedade internacional.

Essa �� uma pol��tica extremamente limitada. No filme, assim como na vida real, pessoas negras que n��o tem a sorte de possuir uma fant��stica fonte de energia m��gica enfrentam s��culos de escravid��o, colonialismo, imperialismo e subjuga����o. Elas s��o sistematicamente exploradas e brutalizadas, mesmo quando seu trabalho �� a fonte de riqueza de seus opressores. Ainda assim, as pessoas em Wakanda permanecem��isoladas, cercadas por luxo e conforto no que poderia ser considerado um grande condom��nio fechado. Em outras palavras, elas se comportam como qualquer elite capitalista moderna.

No filme, o personagem mais ressentido com o isolacionismo de Wakanda �� Killmonger, o filho afro-Americano de um expatriado morto. Criado na periferia de Oakland, Calif��rnia, Killmonger �� uma alma perturbada, uma crian��a problem��tica da di��spora que promete retornar �� terra de seus antepassados para tomar o poder e distribuir as armas incompar��veis de Wakanda para pessoas negras oprimidas em todo o mundo.

Em resumo, Killmonger ����um��revolucion��rio. O fato de ele ser apresentado como sociopata �� um dos aspectos mais problem��ticos do filme.

Superficialmente, Killmonger serve para real��ar o protagonista do filme. Como um dispositivo pol��tico, no entanto, ele desempenha um papel muito maior, pois seu personagem existe para desacreditar um movimento radical internacional. Na verdade, Killmonger �� um mecanismo atrav��s do qual Pantera Negra reproduz uma s��rie de id��ias perturbadoras.

Id��ia Perturbadora n��mero 1: A desaven��a entre africanos e afro-americanos

Killmonger incorpora a m��xima de ���voc�� n��o pode voltar pra casa���. Sua busca pelo ���retorno��� para o solo de seus antepassados (um lugar onde ele nunca esteve) �� apresentado como tr��gico e inalcan����vel. No entanto, h�� uma grande hist��ria por detr��s desse impulso.

Por s��culos, afro-americanos e outros membros da Di��spora Africana tem buscado a repatria����o para o continente africano.��Esse anseio pela reunifica����o e restaura����o dos la��os de parentesco �� um subproduto da experi��ncia hist��rica de dispers��o for��ada.��Desgastados e explorados em todo o mundo, gera����es de pessoas negras ansiavam por uma terra onde pudessem encontrar seguran��a, prosperidade e poder. Muitas vezes eles viram na ��frica esse alicerce.

Entretanto, ap��s a Segunda Guerra Mundial, houve uma nega����o de qualquer forma de internacionalismo negro popular por parte dos l��deres que conduziram a guerra fria no frente americano. Intelectuais argumentavam que ���o negro��� era exclusivamente norte-americano, que norte-americanos e africanos eram separados e desconhecidos e que o Pan-africanismo era uma fantasia f��til e perigosa.

Todavia, afro-americanos nunca abandonaram o esfor��o para recuperar e reivindicar os la��os africanos. Esse objetivo inspirou atividades simb��licas nos anos 60 e 70, incluindo a ado����o de roupas, penteados e nomes africanos. Tamb��m ajudou a reviver uma consci��ncia revolucion��ria, uma cren��a de que o processo de descoloniza����o poderia vencer o imperialismo ocidental e libertar n��o apenas africanos, mas tamb��m afro-americanos e outras pessoas subjugadas ao redor do mundo.

Isso n��o era apenas um ideal negro. Foi o princ��pio do Movimento dos N��o Alinhados, uma luta pela autonomia e poder do ent��o Terceiro Mundo endossada pela confer��ncia ���Afro-Asi��tica��� em Bandung, Indon��sia, em 1955. Os herdeiros espirituais de Bandung, incluindo Malcolm X, rejeitavam a auto-proclama����o dos Estados Unidos de “l��der do mundo livre”.��Eles viam os Estados Unidos como um imp��rio violento e insistiam que “as na����es mais��escuras” (alus��o ao livro Darker Nations de��Vijay Prashad)��deveriam adquirir poder – militar ou de outra forma – para resistir �� viol��ncia norte- americana.

Killmonger, ao que parece, �� um neto fict��cio de Bandung, mesmo ele tendo falhado em apresentar um movimento pac��fico com ��nfase nos direitos humanos como alternativa ao expansionismo. Ainda assim, a verdadeira estrutura de poder americana ainda teme qualquer alian��a global que possa representar uma contra-for��a ideol��gica �� hegemonia dos Estados Unidos. Assim, Killmonger �� retratado como louco e sua trama para armar aqueles que Frantz Fanon chamou de “os miser��veis da terra” �� lan��ada como uma amarga cruzada por vingan��a, e n��o como uma resposta racional aos horrores da supremacia branca e do imperialismo.

Nesse sentido, defensores do imperialismo s��o capazes de distorcer o projeto hist��rico da esquerda no Terceiro Mundo enquanto equalizam �� terrorismo toda vis��o de globaliza����o que n��o seja organizada pelo capitalismo norte-americano e seus aliados.

Id��ia Perturbadora n��mero 2: A patologia afro-americana

Retratar o Killmonger como demente n��o apenas difama o radicalismo, tamb��m recria temas racistas sobre corrup����o e imoralidade ligados ��s pessoas negras. Ironicamente, esse aspecto de Pantera Negra tem sido amplamente ignorado em meio �� alegria por representa����es mais promissoras de negritude. Na verdade, as representa����es lisonjeiras s��o desiguais. Pantera Negra define a virtude africana contra a imoralidade afro-americana.

A justaposi����o �� perniciosa. Afinal, as afirma����es da degenera����o negra acompanham narrativas de decl��nio cultural, incluindo a id��ia de que os traumas da escravid��o ou da vida urbana prejudicaram permanentemente os afro-americanos. Como o historiador Daryl Scott mostrou, tais mitos geraram desprezo e pena pela Am��rica negra. O que eles nunca fizeram �� honrar a resili��ncia que permitiu que os negros americanos sobrevivessem aos pesadelos do Novo Mundo.

Isolada e provinciana, Wakanda carece de uma heran��a revolucion��ria que possa ajudar a moldar suas institui����es sociais ou rela����es internacionais. Oakland, por outro lado, possui um legado de luta radical enriquecida pelo esp��rito irreprim��vel dos afro-americanos.

Id��ia Perturbadora n��mero 3: O Salvador branco

Se Pantera Negra refaz imagens feias de afro-americanos, tamb��m reafirma o ideal de salvador branco. Em uma reviravolta especialmente grotesca (alerta de spoiler), este papel �� feito por um agente da CIA, que �� levado a Wakanda para tratamento m��dico, e acaba ajudando o reino a derrotar Killmonger. As ironias aqui s��o in��meras. �� um desafio identificar um inimigo maior das massas africanas do que a CIA, a ag��ncia que ajudou a assassinar ou subverter algumas das luzes mais brilhantes do continente, desde Patrice Lumumba, no Congo, at�� Nelson Mandela na ��frica do Sul.

Apresentar os Estados Unidos como um guardi��o dos interesses africanos camufla o conglomerado das for��as ocidentais, de bancos globais �� corpora����es multinacionais, que continuam a roubar a riqueza da ��frica mesmo muito depois do fim formal do colonialismo. Tamb��m obscura a extens��o impressionante em que o militarismo dos Estados Unidos penetrou no continente africano em nome de uma incessante “Guerra ao Terror”.

Se o povo de Wakanda tivesse lido o te��rico de Martinica, Aim�� C��saire, eles poderiam reconhecer o imperialismo americano como ���a ��nica domina����o da qual nunca se recupera���. Em vez disso, as cenas finais de Pantera Negra sugerem que a colabora����o entre o reino e a superpot��ncia global �� o futuro.