Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 236

December 19, 2018

Why western donors love authoritarian leaders

Abiy Ahmed Ali. Image credit Odaw via Wikimedia Commons.

���Rwanda has turned out to be an incredible partner,��� the philanthropist Howard Buffett��said��at a World Economic Forum event in Kigali in 2016. ���When we show up in this country, we know that we can do what we need to do, we know we can meet with who we need to meet with.�����For a generation, British Prime Minister Theresa May��said��in August, her fellow citizens only thought of famine when they thought of Ethiopia. But now the country ���is fast becoming an��industrialised��nation, creating a huge number of jobs and establishing itself as a global destination for investment.���

Western governments and philanthropists have matched their rhetoric with money. In recent years, Rwanda and Ethiopia have been some of the largest recipients of aid money from the UK and US governments, as well as some of the West���s leading philanthropies, including the Gates Foundation. To justify these lavish contributions, Western leaders have repeated versions of a story, that regimes in these countries are undergoing a state of transition, and that democratic governance will have to wait until it develops some more. But where does this story come from?

To state the obvious, Western governments have often contradicted their officially pro-democracy positions to back authoritarian regimes they considered useful. At the end of the colonial era, and the start of the Cold War, European and American leaders invoked a fear���real or imagined���of a world succumbing to communism to explain why they occasionally needed to cast aside principles in the realm of foreign policy. Democracy was nice, even ideal, but only if the ���right conditions��� were met, and the chosen leaders were inclined to uphold the Western-led international order. In the meantime, allied strong-men were a more than adequate substitute.

But as the Cold War gave way to a world where commerce was the organizing principle of the day, Western governments justified their alliances with authoritarians with new stories. To understand where those stories came from, it helps to look at China. As the journalist James Mann details in his 2007 book,��The China Fantasy, under President Nixon, US leaders accepted China as a ���card��� to play against the Soviet Union, and gradually relaxed trade barriers to bring it more closely to the West. With the end of the Cold War, however, US leaders were wondering aloud if it was worth maintaining the special arrangement any longer.

In 1991, Bill Clinton ran for president arguing that any trade agreement with China had to be tied to ���specific, tangible improvements in human rights,��� in Mann���s words. The position was popular with voters, many of whom had��watched��Chinese troops murder the pro-democracy demonstrators of Tiananmen Square on TV a few years earlier. But as president, Clinton had to contend with American business leaders who saw his emphasis on human rights as a hindrance to their investments in a country that was just beginning a period of rapid growth.

In 1994, Clinton dropped the demand for tangible improvements from his trade proposal, replacing it with a package of human rights and pro-democracy gestures, like asking American businesses to draft codes of conduct before investing in China. To the surprise of almost no one, what Clinton called a ���new human rights strategy��� achieved nothing. But even a predictable failure needed a cover story. Near the end of his first term, Clinton adjusted his stance once more. Instead of combining free trade with some pro-democracy gestures, the US would merely allow free trade. Trade, and the growing economy that resulted, Clinton said, would��force��democratic change in China– somehow, someday, inevitably. Since political freedom would be a natural outcome of free trade, there was no reason to compel China to reform itself. Politics couldn���t shape China���s economy, in this telling. Its politics would be shaped by its economy.

Clinton���s story was irrational, a neoliberal myth that made a bald effort to give American companies an advantage abroad sound intellectually sophisticated and morally upright. But Clinton held to it through the end of his presidency. Campaigning for China to join the World Trade Organization, Clinton said membership was ���likely to have a profound impact on human rights and political liberty.���

It did not. Since 2000, the Chinese government has not only become��more��authoritarian, it has become a model for authoritarian regimes around the world. And yet, the notion that free trade makes people free persists, not just in the global elite���s comments on China, but, more recently, in their comments on African regimes which aspire to fit the Chinese mold.

In an��interview��this November with��Ezra Klein,��of explainer site Vox,��Bill Gates made a robust defense of authoritarian regimes in Africa. People intent on helping the world���s poor could not afford to work exclusively with democratic countries. ���If you wait, usually you only get really good governance once a country is middle-income,��� he said. And besides, there was no need to wait. As examples, he cited his two favorite countries in Africa. ���When you have a leader like [Paul] Kagame in Rwanda who appoints good people and really cares about these results, it���s a fantastic thing,��� he said. ���Neither Ethiopia [nor] Rwanda checks every box of excellent government. It���s likely that those countries,��until they get to middle-income status, won���t have all those characteristics.���

When Klein pressed Gates on the governance issue, Gates was more blunt. ���It���s important to separate out the economic model of development from that political model,��� he said. The most important changes governments can make were to adopt ���market-based pricing��� and ���invest��� in citizens by bolstering sectors like health and education, he added. Any government could make these changes, even an authoritarian one.

Just like Clinton a generation before, Gates is telling a story about the nature of a nation���s economy.��An economy, he says,��is shaped not by politics, but by policy.��Politics is complicated, but policy is simple: either it���s good (market-based), or bad (something else). The economy���s possibilities are accordingly easy to comprehend as well: either it grows because of good policy, or it doesn���t grow, for the opposite reason. With a robust economy, the many wants of a people���even freedom itself���are possible. Without it, very little is.

But Gates��� telling also represents an evolution from Clinton���s original fable. Not only might economic growth lead to greater freedom,��he says,��authoritarian regimes could��even be good for their nation���s economies���better, even, than democratic ones.

���There���s never been as strong a coupling between economic growth and democratic freedoms as we���d all like,��� Gates said later, this time with a new example to make his point. ���China grew dramatically faster than India did.��� (India is a democracy.) ���Now, India���s a very good story��� But it���s not even close to what happened in China��� The human freedom argument is going to have to be made on its own.���

Elsewhere in that interview, Gates ponders whether China,��having��now achieved middle-income status, will become more democratic. ���Will their political model progress or not?��� he asks rhetorically. ���That���s a valid question.”

The economy comes first, though in Gates��� telling of the story, democracy is no longer inevitable.

Fortunately for their Western supporters, leaders in these countries are willing to maintain the democratic ritual. In August 2017, Kagame won a third term as president of Rwanda, in an election that observers from the East African Community��called�����really successful��� and generally in line with international standards.

And yet there were numerous reasons to be suspicious. To begin with, Kagame won with 99 percent of the vote. Three opposing candidates had been disqualified before the election. When Frank��Habineza, one of the two candidates allowed on the ballot, held rallies in the northern districts of Rwanda, Human Rights Watch reported that Kagame���s security forces went house-to-house intimidating voters into staying at home.

With the election over, Kagame has resumed his position on the world stage. Earlier this month, Kagame was��rallying��a crowd at the Global Citizen Festival in Johannesburg, a fundraiser for aid organizations on the occasion of Nelson Mandela���s 100th birthday. Kagame���s security forces have been caught��assassinating Rwandan dissidents��in South Africa since Kagame���s rise to power, but nothing so controversial came up in the president���s address.

���Tonight, I join you to pay tribute to Nelson Mandela,��� he said to cheers. ���He never gave up on Africa. He believed African children can achieve anything. It���s in our responsibility to continue building on Mandela���s legacy.���

December 18, 2018

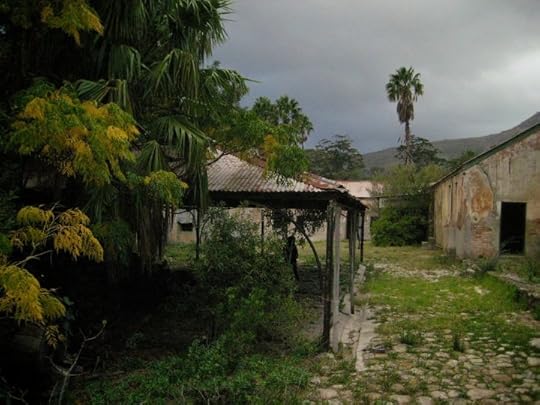

The battles over land in Namibia

Image credit Thomas Becker via Flickr.

Thirty��years of German settler colonialism in South West Africa (1884 to 1914) paved the way for continued white minority rule under South African control. The primary resistance against the foreign invasion triggered��the first genocide of the 20th��century among the��Ovaherero, Nama and other groups. As main occupants of the eastern, central and southern regions of the country, they were forced from their land into so-called native reserves.

Since then, the land (dis-)possession continued. The South African Apartheid regime���s administration provided Afrikaans-speaking poor whites a new existence as farmers in the occupied so-called fifth province. Land appropriations and resettlements took place until the 1960s also as part of the Bantustan policy, which was transplanted under��the so-called Odendaal Plan.

The limits to liberation

Independence did not bring any decisive changes to the skewed patterns of colonial land distribution created. The negotiated transition to sovereignty in 1990��entrenched the structural discrepancies. In turn for occupying the political commanding heights of the state, the national liberation movement-turned-state��SWAPO accepted the material inequalities existing without any major debate. Rather, controlled change��resulted in changed control.

Essential clauses seeking to maintain the economic status quo��in Namibia���s Constitution��were drafted already in the early 1980s as an integral part and precondition by a Western Contact Group, representing three of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council,��initiating a��negotiated decolonization. It was up to SWAPO to propose the adoption of these constitutional principles in the Constitutional Assembly as the final step towards sovereignty. Articles 5 to 25 in chapter 3 (���Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms���), cannot be changed. As stated in article 25(1): ���Parliament or any subordinate legislative authority shall not make any law, and the Executive and the agencies of Government shall not take any action which abolishes or abridges the fundamental rights and freedoms conferred by this chapter.�����Next to civil and political rights, article 16 includes the freedom and protection of property:

All persons shall have the right in any part of Namibia to acquire, own and dispose of all forms of immovable and movable property individually or in association with others and to bequeath their property to their heirs or legatees: provided that Parliament may be legislation prohibit or regulate as it deems expedient the right to acquire property by persons who are not Namibian citizens.

The State or a competent body or organ authorised by law may expropriate property in the public interest subject to the payment of just compensation, in accordance with requirements and procedures��to be determined by Act of Parliament.

As a consequence, existing socio-economic inequalities were officially recognized. Private owned freehold land, amounting to 48% of the territory, remained in the hands of less than 5,000 mainly white farmers, while over 70% of the population nowadays close to 2.5 million Namibians remained directly or indirectly dependent upon the 35% communal land (the remaining 17% are state owned and to a large extent nature reserves). As recently��summarized: ���The pattern of land distribution and ownership reflects class inequality and perpetuates racial inequalities.���

The first land conference���promises undelivered

Since independence, the question of land���not surprisingly���remained a hotly contested issue. Already in 1991,��a major National Land Reform Conference��took place. It��recommended:

redistribution of commercial farmland, mainly on the basis of willing seller-willing buyer, with��government having preferential rights to purchase farmland for resettlement purposes;

introduction of a land tax;

reallocation of underutilised land;

limits to the size and number of farms of private owned land;

elimination of foreign owned land and absentee landlordism.

In the communal areas (the former reserves), situated mainly in the Northern regions and offering the minimum rainfall to cultivate the land, ���the landless and those without adequate land for subsistence��� should be given priority. Disadvantaged communities (in particular the San) ���should receive special protection of their land rights.��� However,�����given the complexities in redressing ancestral land claims, restitution in full is impossible.���

As a result, meaningful restitution was not implemented at all. As early as the mid-1990s, disappointed��locals already held the view that the land reform had been completed. After all, almost every member of cabinet had by then acquired a private farm with state support under preferential conditions. For many, this also explained why the land tax remained��a “work��in progress” for decades to come instead of being implemented as a means to enhance rural transformation.

While the most marginalized battling for survival in the communal areas were supposed to be protected, their de facto expropriation became in parallel the order of the day. Local headmen and chiefs in cahoots with the new political and administrative elite transferred the exclusive individual right of utilization of land and resources to the latter in the higher echelons of state power. This often included their access to and control over water and boreholes (at times state-financed as drought-relief measures). By illegally fencing the allocated land, the beneficiaries de facto privatized the prey as personal property as��a form of elite land grabbing.

Failed resettlement policies

Despite the declared policy and the institutionalization of a separate Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation (nowadays the Ministry for Land Reform), purchasing of farm land was slow and inefficient. The Ministry did not even spend the annual budgetary��allocations for the purchase of land, despite many farms on the market. Rather, what emerged was a rhetorical policy on land lacking any��meaningful land policy. Where farms were used for resettlement purposes, beneficiaries were often simply dumped but not enabled to utilize the land due to lack of capital and know-how.

In a prominent case, farm��Ongombo��West near the capital Windhoek made good business in exporting cut flowers to the European market. It was expropriated after a long legal battle. Handed over to landless people, the production collapsed and the infrastructure deteriorated. Occupants are unable to make a living, as documented in��a televised news clip.��Ironically so, on��a recent state visit to Kenya, Namibian President Hage Geingob praised the cut flower industry there as��a good example��for economic development.

In southern Namibia, the farms Neue��Haribes��and adjacent��Baumgartsbrunn��were once with a combined size of 80,000 hectares, the country���s biggest private farming unit. The carrying capacity of 12,000 karakul sheep indicated the limits under the dry climate. The enterprise owned by a locally operating German company provided a meagre income for close to a hundred farm workers and their families mainly from the vicinity and had a school for their children. When Persian lamb furs were in less demand the farm became uneconomical. In 2010, the state purchased 50,000 hectares from the Swedish absentee landlords. Now the left overs are in total shambles. The residents have no means of income and��depend on food aid.

Such examples make one wonder if state policy was eager to create a self-fulfilling prophecy that resettlement schemes do not work. But the failed policy only testifies to the incompetence and lack of political will beyond the hunger and greed to own land among the new elites. There are many good but hitherto��largely ignored recommendations��how best to provide resettlement farmers with meaningful��opportunities��to make a living.

In addition, the allocation of land to members of communities from other regions of the country became a growing bone of contention. Beneficiaries were often historically from the northern parts of the country. The land in their home regions was never seized under colonialism. The new mobility��unlocked by political independence now provided access to land in other parts of the country. Those whose ancestors were robbed of their land by German and South African colonialism, however, remained on the margins and witnessed the new redistribution often as another means of marginalization and discrimination.

Furthermore, while classified as ���previously disadvantaged,��� many of the beneficiaries were anything but still disadvantaged. Members of the political and bureaucratic elite received preferential treatment. Subsidized by taxpayers��� money��they became weekend or hobby farmers. Trying to investigate the mounting complaints, Namibia���s Ombudsman demanded in May 2018��access to the list of resettlement farms and their beneficiaries. It took the Ministry several months to finally hand it over, only after the Ombudsman had threatened��to take legal action. By then the second land conference was over. A widely demanded proper land audit is still missing.

In late 2016/early 2017��a fall out��between the Deputy Minister for Land Reform and his Minister (a son of Namibia���s first president Sam Nujoma) led to the former���s dismissal first from office and later from Parliament and SWAPO. A Landless People���s Movement (LPM) was subsequently founded, which��submitted��its registration as a political party in September 2018.

Access to scarce and costly urban land had also emerged as a political issue, pushed by activists from the SWAPO Youth League. Their formation��of an Alternative Repositioning (AR) with regard to urban plots in 2015 has since then��become another political factor.

At a SWAPO Central Committee meeting towards the end of August 2018, President Geingob took a swipe against those mobilizing around the issue of land. For him, these were ���failed politicians��� merely looking for personal gains. He accused them of tribalism,��playing with people���s emotions, and warned that��they could��instigate civil war.

The second land conference���more promises

After several postponements, the second land conference���announced with much fanfare���finally came and went during the first week of October 2018. The Namibian government invited more than 800 participants and allocated N$15 million (a million US$) for the five-day event. Given the overwhelming dominance of state authorities and other official institutions as well as indications that SWAPO tried to hijack the agenda, civil society organizations��threatened to boycott. At the end, most of them participated, if only to make use of the opportunity to voice their frustrations.

As President Geingob��stressed��in his opening speech:

As the head of this Namibian House, I am committed to ensuring that the basic needs of all inhabitants are met. I believe that each and every Namibian should live a dignified life. I feel the pain of the landless. I feel the pain of the dispossessed. I feel the pain of the��hungry and impoverished.

The Ministry for Land Reform provided access to��most of the documents submitted, including those of the first Land Conference. Compared with the 24 resolutions adopted but hardly implemented then, many matters in the now��40 resolutions��were��a modified follow up.

A significant new addition was the issue of urban land and informal settlements. It recognized the demands of urban squatters, estimated at almost a million people���40%��of Namibia���s��total population���to affordable housing. The capital Windhoek is��a tale of two cities.

Notably, the issues of communal and of ancestral land also received more prominence and a greater willingness to consider interventions��by the state. These included a resolution stressing the need for the protection of tenure rights mainly in the interest of the poorest as victims of illegal land occupation and the condemnation of the ongoing privatization of communal land by members of the new elites.

While it was pointed out in 1991 that ���restitution in full is impossible,��� during the 27 years since then no serious efforts were made for meaningful restitution at all. Now the recommendations were in stark contrast to the earlier insults by Namibia���s President as quoted above in response to such demands. Significantly, a Presidential Commission of Inquiry on Ancestral Land should be tasked to offer further advice.

Overall, the local responses to the final document adopted were based on previous experiences��where��not much happened after similar such conferences. ���The proof of the pudding is in the eating,��� concluded a columnist in the state-owned newspaper. ���Placing one��or two plasters on the stump of an amputated leg, is not a cure,��� remarked��an editorial��in��The Observer,��a weekly paper.

The meaning of land���beyond economy

What complicates matters is that land is not merely an economic affair. Only about 8%��of the over 825,000 square��kilometers��of��land, mainly situated in the Northern communal areas, are suitable for dry land cropping. Its size shrinks due to the effects of climate change. Droughts have become a regular feature, and chronic water shortage makes��farming even more difficult. Two-thirds of the country are semi-arid, another quarter is arid. Some 60% of the freehold agricultural land receives on average less than 300 mm rainfall annually. The means of income among commercial farmers���with the exception of some big cattle ranchers and farms producing maize and other crops under irrigation���have considerably shifted towards guest farms and trophy hunting to benefit from tourism as the current most important economic growth sector.

Beyond economic matters, however, the land issue is also a matter of identity; for those who own it as much as for those who feel it should be theirs. Colonialism went along with and remains associated with violent land theft. Therefore, the current distribution of land in Namibia is a constant reminder that colonialism has not ended with independence. It continues as long as restorative justice is��.

But as legitimate as these claims are, the restitution of land is confronted with a dilemma. What��King Louis XVIII���s advisor��Talleyrand reportedly told��the king��applies for land restitution too: ���treason is merely a matter of dates.��� Nando���s controversial��TV ad of 2012,��taken off the air��by the South African state broadcaster��on the grounds��that it is xenophobic,��makes the point: going back long enough, legitimate land claims would rest solely with the descendants of the San (Bushmen) as the only indigenous people roaming Southern Africa.

History cannot be fully reversed. The structural legacies created under Apartheid and the long-term demographic impact of the genocide have left irreversible marks on Namibian society. However, what seems a feasible compromise is to offer the San communities access to and protection in the parts of��Namibia, which have remained their home. At the same time, the forced removal from land on record since the early times of white settler��encroachment would be a widely-accepted reference point.

Some of the festering wounds can be treated. The Land Conference stated on ���ancestral land rights and claims��� in resolution 38 that, ���measures to restore social justice and ensure economic empowerment of the affected communities��� should be identified. And it suggests to ���use the reparations from the former colonial powers for such purpose.��� This might offer a way out of the current stagnation in the negotiations��between the Namibian and German governments. The latest return of human remains documented no breakthrough in coming to terms with the shared past as regards��a somewhat adequate compensation��for the crimes committed.

As part of the long overdue consequences, Germany should fork out the necessary funds for a just expropriation of commercial farmers, whose land was utilized by the indigenous communities and where their ancestors are buried. The German state should also finance the necessary investments���both in terms of infrastructure as well as know-how���that empowers local communities to fully benefit from resettlement and access to land under the conditions��of climate change adaptation. The Namibian government would have to accept resettlement��for the��descendants of those robbed of the land. This would be a wise investment by both governments into true reconciliation towards a peaceful future for all people who want to continue living in Namibia. After all, as a local commentator observed ���the land issue is the most divisive issue of all that Namibia has experienced since independence.���

Land grab 2.0���class matters

But such brokerage requires honesty to obtain legitimacy and credibility. Ten days after the Land Conference, some disturbing news made the rounds.��Rashid��Sardarov, a��Russian oligarch, since 2013 in possession of three farms, added another four farms to his Namibian empire��in a rather dubious transaction. The shady deal with the Land Reform Ministry was sealed a week before the Land Conference. Meanwhile, conference resolution 21 stated ���no land should be sold to Foreign Nationals.��� And a sub-clause under resolution 2 ominously proclaimed ���Implement the Principle of ���One Namibian One Farm���������whatever its unexplained meaning might be. After all, the close to two and a half million Namibians are hardly able to have one farm each. Presumably, the meaning of the resolution links to earlier recommendations that farmers should limit property to one farm only.

With the latest ���billionaire playground�����of��Sardarov��getting the green light, it seems that foreigners are at greater liberty to benefit from exceptions decided on a political level. The deal was justified by the government with the argument that it is a major investment into development. The oligarch purchased the farms and donated them to the state in exchange for a 99-year lease. The lawyer tasked with the transaction for ���the King of Dordabis�����(the area in one of the country���s best farming locations about an hour���s drive from both Windhoek and its international airport) is also frequently acting for the government. He negotiated the agreement with his private partner acting in the capacity as conveyancer of the land deal.

Not surprisingly, the public outcry was massive. After all, following the logic of such arguments could there then also be a tentative “solution” to the land issue once and for all: commercial farmers not willing to vacate their land in return for a just compensation could simply donate their property to the state in a similar deal for a 99-year lease in return. Then the state would be the owner of all commercial farming land, which is utilized for a century to come by the previous owners���almost as long a period since the land was originally appropriated. And given the effects of climate change, the issue of an investment is hardly of any value until or rather by 2117. In response to the outburst of public criticism, the Prime Minister vowed to defend the deal in court. As she��declared: “All requirements of all the laws of the state have been followed.��The government��made use of the legal expertise within government to make sure that it��was��done��properly.”

However, such dubious legal argument overlooks the moral dimensions of such deals. It only documents the ignorance���or rather arrogance���of those in power.���Some 1,200 landless people dumped in a small corridor at��Dordabis,��feel very differently��about the deal than the political office bearers do.

The contrast could have hardly been bigger comparing this transaction, which had the explicit approval of cabinet, with��the closing speech��at the Land Conference by President Geingob. He then, days after the deal had been done, urged: “we need to ensure that we are living in a just and fair society, a society in which the mantra of ���No Namibian must feel left out��� permeates every facet of our coexistence.”

But the landless dumped since years at the margins of the new empire��created at Dordabis, feel exactly left out and betrayed. Their story differs from the populist rhetoric, which is nothing else than the cosmetics trying to cover up an elite pact. People are not fooled when feeling the effects daily. As a commentator in the state-owned newspaper��put it: “the saga of the four Russian farms seems to be the tip of the iceberg��� we��must call upon the Namibian government to institute a forensic audit into the management of land.”

By diagnosing that the ���inaccurate characterization of the land issue is a smokescreen to cover-up continued elite control over not just the land, but all income-generating natural resources in Namibia,�����an editorial in The Observer��managed to put the battles for land in the overall current context:

If an accurate look at who is receiving the resettlement farms, EPLs, fishing quotas, affirmative action farm loans and other natural resource allocations is ever possible, we are convinced it will reveal not necessarily one ethnic group reaping all benefits but one socio-economic class gathering wealth.

December 17, 2018

The politics of reforming traditional land in South Africa

Image credit Maarten Elings via Flickr.

���They want to sell us.���

Those are the haunting words of an elderly woman��in the���48-minute narrative documentary,���This���Land��(2017), about the struggle of���rural people for protection of their rights and accountability on communal land���in rural KwaZulu-Natal. Her words and expression, well-worn hands covering her face, capture the painful controversy of the democratic government���s undemocratic approach to land reform in rural South Africa.

Who are������they��� who want to sell poor, rural people like this woman?���In short, traditional leaders in cahoots with the government.

This woman was describing the reality that��former President��Kgalema��Motlanthe��later acknowledged after hearing hundreds���of rural people across South Africa give testimony on their experiences of land confiscations, insecurity, and destitution, especially in mineral-rich areas such as the Platinum Belt in the northern provinces and land under the jurisdiction of the��Ingonyama��Trust Board in KwaZulu-Natal.�����Motlanthe���was a member���of President Cyril��Ramaphosa���s���task team meant to “clear existing confusion” on the ruling African National Congress���s position on “the land question;��� i.e. the imperative to embark on large scale land reform to right racial imbalances in land ownership and access.

As��Motlanthe��said of the��Ingonyama��Trust Board,��which is appointed by the Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform to administer the public land held in trust for the Zulu people and controlled by��the Zulu royal family��who manage ordinary��people���s access to that land��through traditional leaders:�����People who have lived there for generations must pay the��Ingonyama��Trust Board R1,000 rent which escalates yearly by 10%.���

Specifically, the Trust approaches and advertises to poor, rural people under its jurisdiction that they have insecure tenure in the form of PTO certificates��(an apartheid-era certificate that is upgradeable to ownership in terms��of the Upgrading of Land Tenure Rights Act of 1991)��or no documented right to occupy the land they have inhabited, in many instances, for generations. It tells them that, they can������upgrade������their land rights by��entering into long-term leases���with���the Trust so that they can have proof of residence to register to vote, open bank accounts, register cell phones, or obtain rural allowances from employers.

These are people who typically have���either���PTO certificates or informal land rights (established by long-term occupation that are likely to be considered customary ownership and thus entitling them to compensation under the Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act of 1996). The���Trust,���having gotten these people to unknowingly trade in their rights that are more akin to ownership for the status of tenants, then extorts these���escalating���annual rental fees from them.

The���Trust continues to issue this solicitation via its Facebook and Twitter accounts and advertisements despite the fact that, in March, the��parliamentary chair of the��Portfolio Committee on Rural Development and Land Reform���directed the trust to stop this practice, and a senior official of the��responsible government��department confirmed that the Trust’s income-generating scheme is unauthorized��and��violates both the Constitution and the Public Finance Management Act.

Motlanthe��was���quoted���as concluding:

Some traditional leaders support the ANC, but the majority of them are acting like village tin-pot dictators to the people there. The people had high hopes the ANC would liberate them from these confines of the homeland systems, but��clearly��we are the ones who are saying the land must go to traditional leaders and not the people.

Unsurprisingly, the comment attracted a lot of criticism of the former president, particularly��from traditional leaders��and other insiders and allies��such as��Mangosuthu��Buthelezi, who heads the��Inkatha��Freedom Party, a party close to the Zulu king and traditional leaders in KwaZulu-Natal.

But is what��Motlanthe��said really unwarranted?

The core debate is about who owns the land:��whether the traditional leaders and/or kings or the people who have lived on the land,���burying their ancestors, grazing their cattle, fetching grass, wood and water there. The essential challenge is one of reconciling a global and local political economy that centers���on individual and exclusive forms of ownership with the customary system of nested, overlapping and relative rights coexisting at multiple levels of social organization from the strongest family level rights to the weakest community level rights.

The��Ingonyana��Trust has proceeded on the argument that the Zulu King owns the land and rents it to the people��who live on the land.���The King has therefore interpreted the��High��Level��Panel report produced under��Motlanthe���s��chairmanship as an attack on Zulu land and sovereignty, and has mobilized��amabutho���(warriors) to do as necessary to protect them, including���threatening���secession.

In May��2018, Deputy President David��Mabuza��told��the National Assembly that insecure��land��tenure sometimes emanates from the ���false view��� that������land under traditional leadership is owned by traditional leaders.��� He continued, ���In terms of custom it is the people who own the land; traditional leaders are only custodians of the people���s land.���

Unfortunately, this language of ���custodianship��� does not settle the issue. It is slippery language that the ANC has used for decades to justify allowing traditional leaders control of customary land on behalf of their ���people��� (read: subjects).

Faust,��in the eponymous��legend,�����traded his soul to the devil in exchange for knowledge. To ‘strike a���Faustian bargain’ is to be willing to sacrifice anything to satisfy a limitless desire for knowledge or power.������In short, a “Faustian bargain” is the proverbial deal with the devil.

Before any misunderstandings arise: I am NOT calling traditional leaders and institutions the devil. I am not at all equating traditional governance arrangements with evil.���The deal with the devil that I described��here��is the compact that the ANC has made to perpetuate the fictitious structures that the oppressive regimes of our country’s dirty past created and branded������tribal” in the Native Administration Act of 1927 and Bantu Authorities Act of 1951.

If you do��not believe that the structures that the ANC is perpetuating are indeed an apartheid construct, perhaps you will believe the founding fathers of the ANC. These were their strong responses to the creation of these structures��by��the Bantu Authorities Act.

Here���s Albert Luthuli, himself a Zulu chief in Natal��and onetime ANC President, on this system in 1962:

The modes of government proposed are a caricature. They are neither democratic nor African. The Act makes our chiefs, quite straightforwardly and simply, into minor puppets and agents of the Big Dictator. They are answerable to him and to him only, never to their people. The whites have made a mockery of the type of rule we knew. Their attempts to substitute dictatorship for what they have efficiently destroyed do not deceive us.

And Nelson Mandela,��then leader of the ANC in Transvaal,��writing in 1959:

[I]n South Africa, we all know full well that no Chief can retain his post unless he submits to Verwoerd, and many Chiefs who sought the interest of their people before position and self-advancement have, like President��Lutuli, been deposed…������Thus, the proposed Bantu Authorities will not be, in any sense of the term, representative or democratic.

In 1964,��Govan��Mbeki, who would be sentenced to life imprisonment along with��Mandela that year, and who had done extensive research on and participated in peasant uprisings in the Eastern Cape:

Many Chiefs and headmen found that once they had committed themselves to supporting Bantu Authorities, an immense chasm developed between them and the people. Gone was the old give-and-take of tribal consultation, and in its��place��there was now the autocratic power bestowed on the more ambitious Chiefs, who became arrogant in the knowledge that government might was behind them.

In essence, they rejected what the ANC has embraced in the Traditional Leadership and Governance��Franework��Act of 2013 (TLGFA) when it says in section 28:

Any traditional leader who was appointed as such in terms of applicable provincial legislation and was still��recognised��as a traditional leader immediately before the commencement of this Act, is deemed to have been��recognised��as such in terms of section 9 or 11, subject to a decision of the Commission in terms of section 26.

Section 28(3):

���any ������tribe��� that, immediately before the commencement of this Act, had been established and was still��recognised��as such is deemed to be a traditional community contemplated in section 2.

And��Section 28(4):

…any tribal authority that, immediately before the commencement of this Act, had been established and was still��recognised��as such, is deemed to be a traditional council���

The technical change that the TLGFA Amendment makes then is to give these apartheid constructs of “tribal” governance an extended life in our democracy as “traditional” governance institutions. By this, the government would like us to believe that those institutions that are���to quote Nelson Mandela���not�����in any sense of the term��� so,��have suddenly become traditional.

But they haven’t.

Firstly, not once does the TLGFA provide for recognition of “traditional” structures to be dependent upon consultation with the people who are to be governed by them. And, 15 years after the legislation was initially passed, the elections of 40% of traditional council members that it provides for,��have yet to be seriously carried out in most of the country. ���In case you are wondering: the other 60% is to be appointed by the traditional leader whose own recognition is not at all contingent upon acceptance and recognition by his/her people.

By the government’s own admission, elections have been held for few traditional councils and there are contests and disputes with respect to the overwhelming majority of traditional communities and the institutions of traditional leadership recognized over them.

In the meantime, the government is also processing the Traditional and Khoisan Leadership Bill (TKLB), under which the deal with the devil of apartheid will be fully realized. This Bill would���fully revive separate territorial enclaves in which poor, black people are stripped of their citizenship rights (such as the right to speak for themselves) but are instead forced to be governed as subjects by imposed authorities that the government names “traditional” as it gives these authorities un-traditional and un-democratic “roles, functions and power” to wholly speak on “their people’s” behalf as so-called “custodians of our culture” and “custodians of our land.���

As��summarized��by then-Chief Justice��Sandile��Ngcobo, on behalf of the Constitutional Court, in a��2010��case implicating the TLGFA:

Under apartheid, these steps were a necessary prelude to the assignment of African people to ethnically-based homelands��� According to this plan, there would be no African people in South Africa, as all would assume citizenship of one or other of the newly created homelands���

Amidst the sensational deliberations about “expropriation without compensation��� of white-owned land, it is hard for the public to remain vigilant against all Faustian deals made by our government. But I would appeal to all to pay keen attention to that of the politics of reforming traditional land in South Africa,��for it renews the very foundations on which apartheid was built.

December 16, 2018

The slave holders on the border

Child refugees in Madagali, northern Nigeria, near where Boko Haram displaced people. Image by Immanuel Afolabi via Conflict & Development at Texas A&M Flickr.

The Mandara Mountains, on the border between Nigeria and northern Cameroon, are among the regions that have most suffered from attacks by��Boko Haram.��However, for the inhabitants of this area, this situation is not new;��they instantly recognize in the Boko Haram��leader, Abubakar Shekau, another dreaded enemy from the past���Hamman Yaji.��Yaji��was an early 20th-century Fulani chief and slave trader in the same areas of northern Cameroon and north-eastern Nigeria where Boko Haram operates today. For twenty years, he raided throughout the area, capturing slaves and killing those who resisted him.

Today, non-Muslims living along the border between Cameroon and Nigeria refer to Boko Haram as hamaji, a term derived from their memory of��Yaji’s��depredations. We will not detail here the story of Boko Haram, which has been the subject of many publications. Rather, we seek to understand why people today refer to Boko Haram in terms reminiscent of the��period of slavery: why do they use the term hamaji��to describe Boko Haram, and why do they compare Shekau to��Yaji?

Hamman��Yaji��and��Aboubakar��Shekau

The colonial presence in northern Cameroon and north-eastern Nigeria was marked by the persistence of systems of enslavement, which lasted until at least the 1940s and in diluted forms until even more recently. The primary sources shedding light on this reality are, first, oral traditions collected by anthropologists, and second the German, French and English colonial archives.

The third source for our understanding of 20th century slave-trading is atypical:��a diary dictated between 1912 and 1927 by the most important slave-raider in the southern Lake Chad Basin, Hamman Yaji. His main base was in��Madagali, a settlement west of the Mandara Mountains and now in Nigeria, near the international border with Cameroon. In his autobiographical journal,��Yaji��mentions about a hundred raids directed against settlements in the Mandara Mountains, in which 1600 slaves were captured and more than 150 people killed.

People in Mandara communities still remember��Yaji��as a monster who committed enormous crimes. The Dutch anthropologist Walter van Beek reports, for example,��in��the words of��Vandu��Zra��T��, a local historian whom he interviewed in 1989:

Hamman��Yaji��used people as money. He asked a��Fulbe��woman for a pounding stick and paid with a slave. He bought a mat, and paid with a slave. To buy a calabash, or a stick, he paid with people. Even a jar with��shikwedi��(a crop for the sauce [for food���SM/MC]) he paid with a slave. That is what he did.

Extraordinary characters may often generate significant myths. This seems to be the case with��Yaji, who for Mandara people became a symbol of war and atrocities. Today, the Boko Haram leader Shekau is developing a similar mythology. In almost every local commentary on Boko Haram and Shekau,��Yaji���s��name��emerges: ���Shekau is no different from Hamman��Yaji. Both love women; both kill without��mercy; both drink water from men���s skulls.���

For locals, the Fulani leader was the epitome of danger, absolute evil, and brutal slavery, and it is this��pillager��who they perceive has returned in the person of the Boko Haram���s��Shekau: ���For me, Shekau, he is the same as the chief in��Madagali��who used to send his troops��to capture girls.���

Time does not really seem to have changed the memory of the ravages of the Fulani raiders, constantly evoked in local conversations about Boko Haram: ���Slavery is now back, and it is��everywhere, even in the mountains,��� laments one informant.

At the same time, the differences between the situations of��Yaji��and Shekau are obvious: modern life, with much wider networks of relations within and beyond Nigeria, rooted in state functions and��beyond; the presence of the internet and a global radical Islam;��the use of video and news technologies by Boko Haram;��the use of motorcycles as a means of mobility��� all this provides context that distinguishes these two figures and the processes that they embody, slavery and Boko Haram.

Despite all this, the analogies between��Yaji��and Shekau remain striking, especially for the inhabitants of the��Mandara��Mountains: extreme violence, the evocation of the slave market, the idea of being invested with a divine mission, the production of quasi-apocalyptic discourses, the division of the world into ���believers” and “unbelievers,��� and the inspiration drawn from Islam are as easily recognizable in the earlier historical moment as they are today.

I will sell (the Chibok girls) in the market

Perhaps the most striking analogy between these two actors is the fact that girls and women are the main targets of kidnapping.��Yaji���s��targeting of young women permeates his diary. For example, he reports the following attacks during a short period in mid-1913:

May 21: �����I sent soldiers to��Hudgudur��and they captured 20 girl slaves.

June 11:�� �����I sent��Barde��to��Wula, and they captured six girl slaves and ten cattle, and killed three men.

June 25: ��� I sent my people to the pagans of��Midiri��and Bula and they captured 48 slave girls and 26 cattle and we killed five people.

July 6: ��� I sent my people to��Sina��and they captured 30 cattle and six slave girls.

Enslaved young women were taken in other ways as well: On August 26, 1917,��Yaji��writes ������I fixed the penalty for each slave who leaves me without cause at four slave girls and, if he is a poor man 200 lashes.���

What did��Yaji��do with the many hundreds of slaves captured between 1902 and 1920? This question is particularly pertinent since, by that time, the pre-colonial slave markets in the region had already been abolished by the British. It seems likely that��Yaji��never made any significant monetary profit on his slaves. However, his diary indicates that he used young enslaved women as a kind of human currency in themselves, trading them for horses and other goods. His diary also states that he gave them as gifts to his supporters in recognition of their allegiance.

The parallels here with Boko Haram are striking.��Madagali, capital of��Hamman��Yaji, is only 80 kilometres from Chibok, where, in April 2014,��Boko Haram kidnapped 276 girls in a government secondary school. The Chibok girls were probably of about the same age as the girls who were the target of the��Yaji��raids. Shekau did not keep a diary, but��in 2014,��he boasted of selling the girls from Chibok: ���I will sell them on the market, in the name of Allah. There is a market where they sell human beings […]. A 12-year-old girl, I would give her in marriage, even a 9-year-old girl, I would do it.���

What slave market was Shekau talking about? Such markets do not exist today, just as they did not in the days of��Yaji. What, then, is the motivation behind these kidnappings of girls? We need to remember that the Chibok kidnapping is not the only such kidnapping of young women undertaken by Boko Haram; it is merely the most famous. Young women have very frequently been the target of kidnappings.

While some women have voluntarily joined Boko Haram, the fates of women who were kidnapped and forcibly married, and of those who voluntarily joined Boko Haram, were very different.��While the latter benefited from better treatment within the organization���some of those women described their husbands as well-off and generous���the former were subjected to sexual and non-sexual violence by the kidnappers. Women who joined Boko Haram voluntarily and married members of the group often remained in��purdah, sheltered from public contacts, where they take care of domestic tasks. Kidnapped women, on the other hand, were used as sources of forced labor���they were, in fact, enslaved.

A number of the Chibok girls who were released reported rape and other forms of inhuman and degrading treatment. In particular, they were subjected to forced marriages (sexual slavery, in other words) to lower-ranked members of Boko Haram, as a reward and incitement to fidelity for Shekau���s followers.

This instrumental use of women precisely parallels the actions of��Yaji��at the beginning of the 20th century: while girls and women captured by force suffered all kinds of sexual and non-sexual violence, those who voluntarily joined the ranks of slavers were treated with more moderation. They had rights and privileges that other categories of slaves did not have access to: right to food, clothing, and sometimes to education.

These advantages led some of these women to value their new lives��as concubines, as illustrated by the words of this former concubine one of us met in��Madagali��in 2007: ���I will not go back to the mountains, because I do not want to eat dog meat and drink sorghum beer��any��more.���

Even given the absence of slave markets, the servitude of young women would be very useful for warlords like��Yaji��and Shekau. Such young women were an extremely effective recruitment mechanism for young men, if they were to be given out as sexual partners. Such young men would normally have difficulty accumulating the wealth necessary to pay the dowry of their wives and thus becoming a��baaba��sare���in Fulani, head of the household. In that case, without the possibility of marriage, they would be trapped in a perpetual adolescence, because they could not be accepted as adults even as grown men.

Why is this important?

Now back to our original question: why do local people refer to Boko Haram as hamaji? Is this merely a repetition of older stories?

The European colonies of a century ago are not the same as today’s postcolonial states of Cameroon and Nigeria, the reports of kidnaping by��Yaji��are now done through social media and video by��Shekau and his followers. This means that the context is undoubtedly different. But Boko Haram���s banditry is still a means of existence, a way of life, as were��Yaji���s��raids. In both cases, women constitute an extremely important spoil of war, evoking the sale of enslaved women in markets that exist in the imaginaries of��modern jihadists. This is not a replication of history but rather its continuity, because violence���and perhaps especially gendered violence���has never ceased to be a reality in this border zone of the Lake Chad Basin.

This conclusion has something to teach us in our search for a sustainable solution to Boko Haram. Instead of treating the symptoms, why should we not determine the origin and nature of the disease? In other words, why not take into account the��historical context of Boko Haram, in order to think effectively about how to combat forms of violence that have never really disappeared in this area?

Local interpretations are informative: they indicate that the actions of Boko Haram are not a mysterious and unprecedented eruption of violence and savagery. Certainly, important elements of Boko Haram���s ideology are imported from beyond the Lake Chad Basin. At the same time, their speeches and actions derive their legitimacy from endogenous doctrinal and historical resources���even if their media productions frequently borrow elements from those of the jihadist groups of the��Middle East.

December 15, 2018

The creation of black criminality in South Africa

The abandoned site of an old reformatory in Cape Town, South Africa. Image credit Mallix via Flickr.

��� Stephen Dillon, 2016[T]he prison is more than an institution composed of cages, corridors, and guard towers; it is also a system of affects, desires, discourses, and ideas that make the prison possible��� The prison could disappear tomorrow and the types of power that give rise to its reign could live on in other forms such as the regimes we call freedom, rights, and the state.

There is an intimate relationship between the prison and concepts of freedom, as Stephen Dillon observes. Operating on dual levels, as both confinement and the basis for freedom, the institution of incarceration has an ambivalent presence. ���The prison is present in our lives and at the same time, the prison is absent in our lives,�����argued Angela Davis. This oscillating presence/absence masks the ideological function that the prison serves, as ���a site into which undesirables are deposited, relieving us of the responsibility of thinking about the real problems that afflict the communities from which prisoners are drawn.��� It exists, in other��words, to produce and naturalize the category of ���undesirables.���

The prison has a strikingly prominent place in South African history. As Michel Foucault argues through the concept of the carceral, the prison operates not only as a physical space but as a powerful social formation. In South Africa, colonial discourses of African disposability and unfitness for owning land operated alongside laws that created new forms of criminality. Because the colonial and apartheid states saw themselves��as bastions of civilization in a sea of African barbarity, they used the instrument of the law to generate new forms of criminality and to transform black people into carceral bodies��by definition. These bodies were also expediently made available for exploitation as cheap labor. The proliferating use of the pass laws (first passed under British colonial rule in 1809 and only abolished towards the end of apartheid in 1988) and the Masters and Servants Act (1841 and 1856, and only abolished in 1974) eventually created the largest imprisoned population on the continent. Such laws created widespread African illegality at a scale ���as industrial as making cars.��� At the level of discourse, they generated the notion that black bodies are inherently criminal, deviant, and dangerous.��That is, following Angela Davis and��Katherine McKittrick���s formulation, they��naturalized��the ���undesirability��� of African subjects.

What explains the long hold of the prison on notions of state governance from the colonial to the apartheid and even post-apartheid periods? The laws that cast a widening net of criminalization over Africans remained in place for nearly 180 years and became built into the very structure of the South African state. In fact, after the South African war ended in 1902, the state and the mining industry became increasingly reliant on the labor of incarcerated Africans. There was a direct correlation between laws that increased levels of imprisonment and the labor needs of the state and the agricultural and mining industries. As Charles van��Onselen��notes, this��mutual reliance on prison labor reflected a ���deeper circular logic��� of an ���economy��� heavily reliant on labour-repressive institutions and instruments such as compounds, prisons and pass laws.���

The infinitely painful pass laws terrorized black South Africans by making their presence in their own country a crime. During apartheid, any black South Africans who did not have approved employment and was caught outside the Bantustans was immediately charged with a crime. This ensured that to be African in South Africa was to be criminal. The Bantustans were created by the apartheid state in order to remove black��people���s��South African citizenship and simultaneously acted as impoverished labor reserves with an endless supply of vulnerable workers, always either imprisoned or about to be imprisoned. Indeed, during apartheid, ���the pass laws ensured the constant flow of men into and out of prisons��� (per Van��Onselen). These laws tied the state to the mining industry through a system of continual imprisonment of black people.

The South African prison system developed alongside and in parallel with the mine compound. De Beers operated both mining compounds and the earliest private prisons in South Africa. The explicit relationship between the mining industry and the industrial scale of state incarceration became clear by the end of the South African War. ���The mining company ��� paid the state for the use of their prison��labour. By the end of the 19th century, the De Beers Diamond Mining Company was using over 10,000 prison��labourers��daily.��� Through its penal policies, the state in effect became a channel of cheap��labor��to the mines. K.C.��Goyer��notes��that ���convict labor was integral to the growing South African mining industry until as recently as 1952��� and was only abolished in 1959. Even after��the legal ending of prison labor, policies such as the ���teaching of skills��� and the recommendation of “useful and healthy outdoor work” for short-term prisoners nonetheless ensured that the state continued��to benefit from penal labor.��The relationship between the South African and the mining industry exemplified the cynical conclusion that ���[e]very system of production tends to discover punishments which correspond to its productive relationships.���

The colonial prison system thus shaped the creation of a modern industrial labor force in South Africa through the production of a constant source of imprisoned labor. This closed machine for manufacturing systematic African criminality would govern the colonial and apartheid economies for over a century and a half. By the early twentieth century, the system of incarceration had become an ���accelerating motion of an engine of oppression.�����From 1902 to 1936, there was ���a huge increase in the numbers sentenced and imprisoned. Very nearly all were black men prosecuted under the taxation, pass and masters and servants laws.��� Much of the modern South African landscape was built through forced��labor. This is obvious on slave-built farm estates, but��prison��labor was also used to build public roads constructed during the 1840s and 1850s, as well as��the breakwater that forms the harbor of Cape Town.

Criminalization��is therefore��central to the history of labor in South Africa. The dangerous connection posited between poverty and moral degradation was given a particular racial taint in South Africa. The political threat posed by racial mixing, especially among the poor, drove an elite project to separate black and white workers under the guise of the ���moral threat��� of racial mixing. The criminalization of black workers served to divide workers along race. In effect, just as Pumla Dineo Gqola��argues that ���rape creates race,��� the development of the working class in South Africa was profoundly shaped by incarceration.

The normativity of racialized incarceration transformed black men into prison material whose confinement was seen as necessary both for their own rehabilitation, and for ordinary society��to function safely and effectively. The imprisonment of African and formerly enslaved people therefore became naturalized and even insidiously viewed as beneficial. In the 1930s, the South African government created programs to address ���coloured��poverty��� that took the form of the ���teaching of skills��� through the��increasing use of prison labor��for road-building and farming. Through these policies, African and coloured��bodies were emptied of all meaning other than��carcerality, and marked by the taint of criminality as ���waste��� bodies which could only be redeemed by useful (imprisoned) labor. This turned black people into objects of fear and simultaneously obscured the crimes that they themselves experienced. Reviewing South African practices of incarceration in the mid-twentieth century, Gail Super��concludes��that ���coloured��and black men were disproportionately criminalized under apartheid [while]��coloured��and black crime victims were largely ignored��by white South Africans.���

Post-apartheid incarceration

The use of incarceration as a state policy continued��untrammeled��from the colonial to the apartheid periods. Worryingly, the post-apartheid period also shows clear continuities with colonial and apartheid policies.��Lukas��Muntingh��notes��that ���the rate at which South Africans are currently arrested rivals the situation experienced during apartheid.��� In fact,��Super��concludes that ���in South Africa today, imprisonment forms a central plank of the government���s crime policies.���

I wish to introduce a further factor into this analysis���while black people as a whole have suffered grievously from a century and a half of mass incarceration in South Africa, the industrial scale of criminalization and confinement takes particular force among a specific group of black people���the descendants of enslaved people, who were known after emancipation as ���coloureds.��� There are clear continuities between ���black��� (at first termed ���native��� in apartheid legislation) and ���coloured��� identities, though these were created as separate racial identities through apartheid���s Population Registration Act of��1950, and black people were placed at the bottom of the racial hierarchy. Despite apartheid���s targeted violence against black people, incarceration figures show that��coloured��men are imprisoned at twelve times the rate of white men, and��twice the rate of black men. This striking phenomenon of disproportionate levels of incarceration has continued from the colonial period to apartheid and even into the post-apartheid period.

How does one explain the contradiction between apartheid���s racial theory and its practice of punishment, manifested in the continuing mass imprisonment of formerly enslaved (i.e.��coloured) people and their descendants? The answer, I argue, lies in the foundational role of 176 years of slavery in South Africa, which has acted as a hidden force in the country���s political culture since emancipation. These numbers suggest that the slave-based system in the Cape Colony generated a code of disposability that continues to shape how formerly enslaved people were viewed after emancipation, that is, as deviant, criminal and in need of control and repair. This formulation of inherent deviance and infinite reparability is evident in the notion that incarceration is actually a��benevolent��state policy. Government programs in the 1930s that led to the increasing use of prison labor for road-building and on farms were described as addressing��coloured��poverty through the ���teaching of skills.����� These laws therefore acted as a means to produce exploitable labor and embedded apartheid-era capitalism in a longer history of slavery and colonialism. The history of the post-emancipation period in South Africa shows an increasing reliance by both public and��private capital on prison labor and discourses of criminality, intoxication, and physical malaise were used to naturalize the resulting epidemic levels of incarceration.

Today, this infrastructure of widespread incarceration has attached a discourse of moral failure and physical contamination to black and��coloured��neighborhoods. The association of such subjects with notions of crime, gangsterism, alcohol and drug abuse, dependency, lassitude and sexual deviancy has created a category of people who appear to deserve and even��need��punishment.

Intimate and industrial punishment

The system of corporal punishment, based on the Masters and Servants Acts, imposed the brutal, degrading and intimate punitive act of whipping on prisoners. James Midgley���s study shows that the widespread use of corporal punishment began immediately after emancipation and continued into the 1970s of corporal punishment, suggesting that the stain of disposability remained attached to emancipated bodies. As the history of punishment in court documents reveal, the severity of such whippings (often more than 100 lashes) has led to severe injury and even death. Despite this brutal history, more than 34,000 young offenders were subjected to whipping as recently as 1970 and its application was explicitly racialized. Originally, in fact, whipping could be enacted solely against black convicts,��a policy which only changed in 1880. By 1952-1954, state figures of corporal punishment against juvenile offenders showed ���an orgy of whipping.��� Reviewing such sentencing in 1970,��James��Midgley��shows��that ���[t]he great majority of children who were sentenced to corporal punishment were��coloured.��� Moreover, he finds that ���while sixty percent of all coloured��offenders were whipped, corporal punishment��was imposed on only twelve percent of white offenders.��� Midgley observes that about fifty percent of black men who appeared before the Cape Court were subjected to whipping. This revealing figure, as well as the fact that even during apartheid, with its focused violence against black people,��coloured��men were imprisoned at twice the rate of black men, indicates that the taint of disposability and criminality associated with enslaved bodies has shaped rates of incarceration both before 1994 and into the present.

Could the reason for the repeated use of the intimate punishment of whipping during and after slavery be that the enslaved (and, later,��coloured) body, in contrast to Khoisan and Nguni bodies, was viewed as both infinitely broken and infinitely repairable? Was the enslaved body nearer to that of the slave-owner and therefore potentially nearer human, if disciplined, compared to indigenous bodies, which were seen as inaccessible and incorrigible? Could the nearness of slave bodies hold both a threat and a promise to repair the flaw of race?

The text below allows me to explore further this apparently oscillating view of��coloureds��as impaired and in need of fixing. In December 2011, a controversial public service advertisement to discourage drunk driving called ���Papa Wag��Vir��Jou��� (���Daddy���s Waiting for You��� in Afrikaans) appeared on South African television. In the advert, a series of men appear on screen one by one to describe their ideal partner. The lines spoken by successive men were ���I���m looking for that special person;��� ���Someone who can handle heavy situations with a smile;��� ���These hands will never let you go;��� and ���I���m quite demanding physically.��� Gradually the lines become more sexually overt and are expressed with more loaded meaning. Only at the end of the advertisement does the camera pull back to reveal that the men are in prison uniforms, surrounded by a crowd of other men clad only in their underwear. While the earlier lines are all in English, the final line of the series, ���Papa Wag��Vir��Jou,��� is delivered in Afrikaans. In retrospect, the sequence of the lines and the tone of weighted intimacy in later lines, especially ���Daddy���s Waiting for You,��� makes clear that the basis of advert���s appeal not to drink and drive was the implicit threat of male rape in prison. The advertisement was reported to the Advertising Standards Authority of South Africa for racism and homophobia, but the ASA dismissed these objections.

The literary scholar Bernard Fortuin��has compellingly��analyzed��the advertisement��in his doctoral research��on a queered history of homosexuality in South African institutions, but��I wish to point to its naturalization of who��belongs��in prison. Behind its public appeal to reduce drunk driving, the advertisement signaled that some people are��at home��in prison while others do not belong. The former act as a warning to the public. The bodies who most clearly signal that they belong inside prison are black and��coloured��men, whose familiarity with the place���their��at-homeness there���is signaled by their tattoos, their at-ease bodies and their casual hand gestures. In contrast, a white man at the beginning is stiff and nervous and a second white man laughs self-consciously. The third man in the sequence is African and he looks intently at the camera. In contrast, the loose delivery of the three��coloured��men who follow him makes the implied threat of rape at the end even more blatant. As��Fortuin��notes, their treacherously sexual brown bodies suggest their familiarity with prison and its intricate hierarchies, violence and power, which is��shockingly clear in the advert. The��sexualization��and commodification of transgressive��coloured��bodies can be seen here and also in the songs and music videos of the white South African music group ���Die��Antwoord.��� Fortuin��points out��how such men���s bodies are simultaneously ���threatening and sexually alluring to the South African public,��� arguing that part of the advert���s effect comes from the fact that the ���prison has been confounded with homosexuality in the South African context.���

The ���Papa Wag��Vir��Jou��� video relies on the implicit threat of prison rape to deter people from drunk driving. Its larger effect, however, is even more disturbing���which is to entrench the putative link between black and��coloured��men and criminality. The history of carceral bodies outlined above allows us to revisit this unremarked association of diverse black masculinities with a sense of at-home-ness in prison. In the visual narrative of ���Papa Wag��Vir��Jou,��� these bodies do not strike me as repairable, but rather, they are��naturalized��in the setting of prison. Instead of being redeemable, the��coloured��bodies arrayed in the prison are portrayed as duplicitous and threatening. In fact, the assumption at first that the men are innocently referring to their ideal partner is revealed as dangerously na��ve. Especially the men who appear toward the end of the advert cannot be trusted. The prison could well be the space of abjection for the putative drunk driver who may end up among the men in the advert, facing the threat of rape. But instead of fulfilling the promise to repair the ���flaw��� of race, the men who are at home there reveal themselves to be irredeemably and inherently ���dirty.��� And that is why they��belong��in prison.

December 14, 2018

The struggle for a minimum wage in Nigeria

Oil workers in Port Hartcourt, Nigeria. Image credit Cristiano Zingale via Flickr.

On Tuesday November 6th, the Nigerian Labour Congress (NLC) called off a general strike after agreeing with the government to increase the national minimum salary by 67% to 30,000 Naira (US$ 83). In typical fashion, Bloomberg, the American business news service,��couldn���t help��pointing out that ���Nigerian��labor��is flexing its muscle before an election, winning a large increase in the minimum wage despite investor concerns about the oil-exporting nation���s deteriorating budget balance.��� The wage increase has been described by the usual dial-a-quote anti-labor��experts as a populist move that will distort the state economy and further fuel inflation. Another example from��Reuters: ���Economists say the new minimum wage risks stoking inflation, which is currently above the central bank���s single digit target thereby creating a new headache for the bank as it defends the currency hit by lower oil prices.���

Contrary to the wisdom of these “experts,” the process is better seen as a��key fora��for democracy at work, the minimum wage being neither fair nor enough for a decent living.��And what should be clear is that Nigerian workers on minimum salary are not to be blamed for��an overspending by public officials.

The new proposed minimum wage is a compromise agreement between workers, employers and the government. Such tripartite negotiations are a sign of democracy at work, founded in the ILO conventions of rights to collective bargaining (ILO core convention #98) and on minimum wage machinery (ILO #26), both to which Nigeria���s��government is a signatory. Minimum salaries should be adjusted on a regular basis to keep up with inflation, and according to Nigerian law, it should be negotiated at least��every five years. The Nigerian negotiations were way overdue given that the last Nigerian minimum wage agreement was in 2011.

In 2011, the minimum wage of 18,000 Naira was equivalent to about US$110, today it is worth less than US$50. This is below the��poverty line, and the NLC claimed it was the��lowest minimum wage on the continent.��It is a far cry from what Lagosians���the inhabitants of Nigeria���s crowded commercial capital���estimate��they needed to make ends meet. Stuck in economic crisis since 2014, the country���s external debts��have doubled in three years��(only a decade after the ���watershed�����debt relief��in 2005), the middle class with stable income is shrinking and the numbers of working poor are expanding. At the same time, the costs of living��is��fast increasing with inflation, illustrated by the fact that��foodstuff like cereals, cooking oil and even spices, are now sold in daily portions.

Though a 67% increased minimum wage sounds formidable, the new minimum wage of 30,000 Naira (US$83) is in real terms it lower than the 2011 minimum wage at the time of agreement (US$110).�� Workers were represented at the tripartite negotiations through NLC, the Trade union congress (TUC) and United Labour Congress (ULC). The (original demand of the NLC and TUC was 66,500 Naira (US$181), while the ULC (which is not recognized by the federal government) demanded 96,000 Naira (US$264). By comparison, the 1981 minimum wage of 125 Naira was worth US$200.

With labor rights under pressure, and an ever expanding share of labor being precarious, even some of the so-called ���privileged���oil��workers “work 12-hours-a-day, six-days-a-week for monthly salaries ranging from US $137 to US $257.�����As one oil worker in Port Harcourt, told a visiting delegation of American oil workers:�����We work like an elephant and eat like an ant. Our salary at (contractor)��Plantgeria��is about 95,000 Naira (US$257). In Nigeria today, you can���t do anything on that. You can���t pay your children���s school fees. You can���t eat well. You can���t do anything better for yourself.�����In my own��work in the Niger Delta, I have met contract workers in oil pipeline security earning wages as low as 20,000 Naira (who had also not been paid for months).

When the ruling APC party called the tripartite forum���consisting of representatives of workers, employers and the state���for minimum wage negotiations at the of December 2017, it was long overdue. It also came after continuous calls from the unions. Nevertheless, the process has been stalling. The��three negotiating��union��centers��NLC, TUC and ULC have been frustrated by the government, and threatened strike on several occasions. The government has held back the conclusion, not only because ���they cannot afford��� an increase, but allegedly also to conclude the deal as close to the national elections in early 2019 as possible in order to gain popular support.

After the tripartite��forum concluded on November 6th, the opposition presidential candidate, Atiku Abubakar (PDP) promised workers�� a��33.000 Naira minimum salary��in his private businesses and a��living wage��if elected. (Atiku���s claim to employ 100,000 workers has been hotly contested on social media.)

Although the Nigerian unions are under deep pressure, they have been able to mobilize and shut down the economy, as demonstrated in January 2012 during the Occupy Nigeria protests. The increase in minimum salary is popular, as it will improve the purchasing power of a large majority of Nigerians.

Formally, the minimum wage agreement is a recommendation to Parliament, which has to pass it into law. The parliamentarians that will vote��are among the richest of the world. While using private salaries to support patronage networks is not necessarily illegal, using private or public funds to stay in political positions through vote buying is corrupt. Nigerian political corruption is well-known, vast and systemic, and politicians��� misuse of public funds for personal and political support tend to increase in the run-up to elections (as in now), and it is particularly strong at state levels.

Nigeria has 36 states. They are key public sector employers. Despite the fact that the Governors Forum, representing the governors of these states, had six representatives at the tripartite forum, they��refuse to accept the new minimum wage��and have threatened to sack workers because they��cannot pay the bill.