Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 240

November 12, 2018

The rebirth of the Nigerian Left?

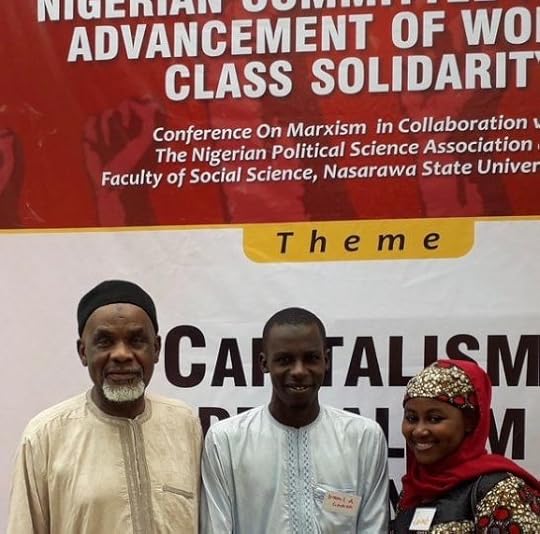

Dr. Ibrahim��Muazzam, Ismail��Auwal��and���Zainab��Mutkthar��delegates at the ���Capitalism, Imperialism, & Revolutions in the 21st Century��� conference held recently at��Nasarawa��State University.

Even as a phrase, ���The Nigerian Left��� might sound paradoxical. What has the world���s��Mo��t drinking capital��and a world leader in global indices of private jet ownership to do with lefty politics? In fact, when I recently tweeted about an academic project I am pursuing entitled ���What���s left of Nigeria���s Left?��� I was not��surprised��to be greeted by a number of comically skeptical responses from��Naija��Twitter��including:

Though amusing, such a view is inaccurate, as I got to see for myself while attending the conference on�����Capitalism, Imperialism, & Revolutions in the 21st Century�����held��recently��at��Nasarawa��State University��(NSU).

The��two-day��meeting��was put together by the Nigerian Committee for the Advancement of Working Class Solidarity���constituted��of��former radical activists and now the leading lights of Nigeria���s NGO sector���in collaboration with the Nigerian Political Science Association and the Social Sciences Faculty at��NSU.��As a student of political ideology in contemporary Africa (and a Nigerian), it was a privilege to attend the first gathering of this sort.

The deeper paradox, however, was that the conference was��inaugurated�� after��17 years of democracy: though the Left was the engine of anti-colonial and pro-democracy struggle,��it has suffered decline in the Fourth Republic. The weight of this history gave the gathering an air that was both momentous and marginal. Held in the literal margins of Nigeria���s capital, the gathering felt modest, barely receiving coverage in the local press. Yet��this is��precisely��what��gave the conference a welcoming and inclusive tone.

It was also a thoroughly Nigerian affair in ways that sometimes sat uncomfortably with its radical aims. Classically, the conference began by ���observing protocols,��� the Nigerian euphemism for paying respects to the highest authorities in the vicinity���in this case the��vice chancellor��of the��university. That a presidential portrait of Muhammadu��Buhari��remained affixed to the wall behind the stage looking down at the audience throughout proceedings was similarly not without irony.��In��classic (though pleasantly) Nigerian form, we were served meat-pie and��kola-nut at tea breaks,��jollof��rice and pounded yam at lunch,��and the conference had its own custom made souvenirs���even its own Ankara uniform.

Conference participants.

Conference participants.Less characteristic for the context was that several presentations on radical feminism,��which profoundly questioned gendered norms and the family,��were welcomed by the audience, triggering neither convulsions from male delegates nor extensive quotations of scriptural justifications for patriarchy.

Delegates to the conference included senior academics, veteran labor activists, feminist intellectuals and advocates, as well as delegations of undergraduates, many of whom were encountering��Marxist��theories for the first time. Some of the veterans included��Dr. Amina��Salihu, Professor Dung Pam Sha, Professor��Jibrin��Ibrahim, Comrades Ibrahim��Muazzam,��Issa��Aremu,��Ene��Obi and many other former student activists.

A notable absence was that of the counter-culture��and artistic Left, which were central��to��revolutionary gatherings in earlier periods of Nigerian history. A similar ���All Nigerian Socialist Conference��� held in��Ahmadu��Bello University in 1977 was attended by non-other than��Fela��Kuti��himself, along with the full contingent of his band and dancers, who according to mathematician and��left-wing��journalist��Edwin��Madunagu�����insisted on sitting on the floor!��� The day may yet come when��Seun��Kuti��opens up a Nigerian Socialist Conference, but that was not to be in��Keffi. Another missed opportunity was��the absence��of�����informal��� working class organizations including market women���s unions, street cleaners�����associations and artisans and traders�����organizations,��many of whom play a critical role in electoral politics (as we saw in the recent��Lagos State APC Governorship primaries in which a sitting governor was defeated��in part because he annoyed the��Association of Waste Managers).

Presentations��covered��the anti-colonial��Aba Women���s War of 1929; the collapse of the Soviet Union; and why the teaching of Marxist theories has declined in Nigerian universities (yes, this was once a thing!). At one point during a Q&A session, an earnest engineering student suggested that the Left should consider changing its name to the�����Right�����for him a synonym for ���correct��� and the more marketable direction overall. ���How you brand yourself is very important,��� he added, as many audience members looked on in a mix of incredulity and anguish. There was also at least one shouting-match sparked by a presentation on whether the Nigerian Left should pursue ���entryism�����by seeking to infiltrate mainstream political parties to move them in a radical direction.

Our deliberations inevitably had certain blind-spots. There was little discussion, for instance, about what the Nigerian Left might learn from the resurgence of socialism in America and Britain following the��delegitimization��of neoliberal and “third-way” politics in much of the West. The conversation could also have been enriched had some presentations offered a Left perspective on pressing economic issues, including��diversification from oil, social security��and the weaknesses of Nigerian Federalism.

However, despite this, the conference accomplished some important feats, the most significant was the fact that it actually happened.��Promisingly,��the organizers also pledged to set up a steering committee to��develop Marxists ideas and politics in Nigeria in a number of ways. These included commitments to host regular conferences, improve upon the teaching of Marxism within the trade union movement, publish classic Marxist scholarship locally, and support comrades who are running for public offices on credible progressive platforms.

It was also encouraging to observe the students and the youth.��In sparking a wide-ranging and inter-generational conversation about alternative political futures, the gathering succeeded in escaping blind partisanship and defeatist cynicism, both of which have come to set the boundaries of�����intellectual�����debate in contemporary Nigerian politics.

November 10, 2018

The idea of a borderless world

'Immigration blues' by Patrick Marion��. Via Flickr CC

As the 21st century unfolds, a global renewed desire from both citizens and their respective states for a tighter control of mobility is evident. Wherever we look, the drive is towards enclosure, or in any case an intensification of the dialects of territorialisation and deterritorialisation, a dialectics of opening and closure. The belief that the world would be safer, if only risks, ambiguity and uncertainty could be controlled and if only identities could be fixed once and for all, is gaining momentum. Risk management techniques are increasingly becoming a means to govern mobilities. In particular the extent to which the biometric border is extending into multiple realms, not only of social life, but also of the body, the body that is not mine.

I would like to pursue this line of argument concerning the redistribution of the earth. Not only through the control of bodies but the control of movement itself and its corollary, speed, which is indeed what migration control policies are all about: controlling bodies, but also movement. More specifically I would like to see whether and under what conditions we could re-engineer the utopia of a borderless world, and by extension, a borderless world, since, as far as I know, Africa is part of the world. And the world is part of Africa.

It is important to attend once again to what is obviously a utopian intent, the question of a borderless world. ��From its inception ���movement��� or more precisely ���borderlessness��� has been central to various utopian traditions. The very concept of utopia, refers to that which has no borders, beginning with the imagination itself. The power of utopianism lies in its ability to instantiate the tension between borderlessness, movement and place, a tension���if we look carefully���that has marked social transformations in the modern era. This tension continues in contemporary discussions of movement-based social processes, particularly international migration, open borders, transnationalism and even cosmopolitanism. In this context, the idea of a borderless world can be a powerful albeit problematic resource for social, political and even aesthetic imagination. Because of the current atrophy of an utopian imagination, apocalyptic imaginaries and narratives of cataclysmic disasters and unknown futures have colonised the spirit of our time. But what politics do visions of apocalypse and catastrophe engender, if not a politics of separation, rather than a politics of the humanity, as species coming into being? Because we inherit a history in which the consistent sacrifice of some lives for the betterment of others is the norm, and because these are times of deep- seated anxieties, including anxieties of racialised others taking over the planet; because of all of that, racial violence is increasingly encoded in the language of the border and of security. As a result, contemporary borders are in danger of becoming sites of reinforcement, reproduction and intensification of vulnerability for stigmatised and dishonoured groups, for the most racially marked, the ever more disposable, those that in the era of neoliberal abandonment have been paying the heaviest price for the most expansive period of prison construction in human history. I refer to the prison here, the carceral landscapes of our world, precisely as the antithesis of movement, of freedom of movement. There is not a more dramatic opposition to the idea of movement than the prison. And the prison is a key feature of the landscape of our times.

In proposing to re-examine the question of a borderless Africa and a borderless world, I would like to stay away from dominant ways with which this issue has been dealt. That is under the sign of Kant and his promise of unbounded cosmopolitanism, and under the sign of liberal individualism understood as an antidote or to the deeply ingrained fascist impulses of European governance and bureaucracies. Although they seem to be worlds apart, both of these approaches are articulated around the concept of the fourth freedom.

In classical liberal thought there are three core freedoms: First of all, freedom of movement. Within freedom of movement, there is freedom of movement of capital, priority number one. But, since there is no capital without goods, there is freedom of movement of goods. Number three is services, and especially in these times of ours, the freedom of movement of those who can provide services. Those are the three core freedoms. So the concept of the fourth freedom has to do with freedom of movement of persons. Traditional engagements with the idea of a borderless world aimed at precipitating the advent of that fourth freedom. Within that configuration a borderless world would be a world of free movement of: capital, goods, services and persons. Such movement, such freedom of movement would not be restricted to the core economically rich countries or states, which is the case as we speak. The Schengen system, for instance, is limited to the core European countries. In fact, if you have an American passport you can basically go wherever you want. The world belongs to you. But this is not the case for every inhabitant of our planet. So in the configuration I have just referred to, the fourth freedom, the ability to move around the planet would no longer be limited to Europeans and Americans. It would be a radical right that would belong to everybody by virtue of each and every individual being a human being. It is a right that would be extended to poor members of the earth. So we keep going back to the question of the earth. There would be no visas, in some instantiations of the fourth freedom of movement there would be no quotas, and no bizarre category to fill in, because you would not even have to apply for a visa. One could just get on a plane, a train, a boat, on the road, or on a bike. Rights of non-discrimination would be extended to all. I will give you one little example. In Cameroon, until the beginning of the 1980s, it was possible to travel to France with one���s national identity card. Most people went to France and came back. They did not go because they wanted to settle there. Most people want to live where they ���belong���. But they want to be able to come and go. And they are more likely to come and go when the borders are not hermetically closed. So, ��a borderless world imagined by the fourth freedom of movement is premised, therefore on this right of non-discrimination and on this circulatory and pendular set of migrations.

To elucidate or pose differently the question of a borderless world, is to contrast two paradigms. On the one hand, examine the liberal idea of a borderless world through the free movement concept and contrast it with African precolonial understandings of movement in space. Contrasting these two paradigms will hopefully give us conceptual resources to expand on this utopian project of a borderless world.

When I say liberal classical thought, of course it is extremely complicated, we understand that. I am giving you an archetype, which itself needs to be properly deconstructed. And here I will rely in particular on a recently published work called��Movement and the Ordering of Freedom��published by Hagar Kotef, an Israeli scholar who teaches at School of Oriental and African Studies ��in London. You might let your imagination work and understand why it is an Israeli who is interested in this. What Kotef shows in that work is the extent to which liberal political thought has in fact always been saddled with a contradiction when it comes to imagining the possibility of a borderless world. Her argument is that this contradiction stems from its conception of movement. She shows that, in fact, two dominant configurations of movement constantly come into conflict with one another, cancelling each other at times within classical liberal thought. Movement here is seen both as a manifestation of freedom and as an interruption, as a threat to order. One of the functions of the state is, therefore, to craft a concept of order, stability and security that is reconcilable with its concept of freedom and its concept of movement. That is the contradiction. Kotef argues, the liberal classical state is the enemy of people who restlessly move around. ��Such people are configured as an unassimilable other. You cannot assimilate them. They are constantly on the move. There are colonial repercussions to all of this. The biggest problem of the colonial state in the continent of Africa from the 19th century onwards was to make sure people stayed in the same place. It had a hard time achieving this. They were constantly on the move. They were ���uncaptured���.

So, the business of the state is how to capture them. Without capturing them, sovereignty does not mean anything. Sovereignty means you capture a people, you capture a territory, you delimit borders and this allows you, in turn, to exercise the monopoly of territory, of course, monopoly over the people and in terms of the use of legitimate force and, very importantly���because everything else depends on that���monopoly over taxation. You cannot tax people who have no address. The state sees such people as enemies, both of freedom, because they do not exercise it with restraint, and of security and order. You cannot build an order on the basis of that which is unstable.

The same state is a friend of self-regulated movement. Why? Because freedom here is understood as being about moderation, about self-regulation. It���s not about excess���excessive movement immediately conjures problems of security. So, as Kotef argues, movement not only has to be restrained via an array of disciplinary mechanisms, it has to be reconciled with freedom and to some extent self-restraint, but the ability to restrain or regulate oneself is not assumed to be the share of all subjects. Not everybody is able to restrain him- or herself. Some movements were therefore configured as freedom, and others were deemed improper and were conceived as a threat. That is the bifurcation we have in classical liberal thought. It is the spectre that haunts classical liberal states, from those years up to now. We have not gotten rid of that spectre.

The way in which classical liberal states have tried to resolve this contradiction has been by managed mobility, which is back on the agenda right now as I speak, in Europe and even in South Africa where I have been doing some work with the Department of Home Affairs on recalibrating inter-African migrations. The key concept is ���managed mobility���. So, within the framework of managed mobility, certain categories of the population are constantly seen as posing a threat, not only to themselves and to their own security, but also to others��� security. Such a threat, it is thought, can be diminished if their movements are confined and if they are domesticated and subject to some type of reform.

In the classical liberal model security and freedom came to be defined as a right of exclusion. Order within that model is about securing the unequal ordering of property relations. Asserting the boundaries of the nation goes hand in hand in that model with the assertion of the boundaries of race. Now, defining the boundaries of race within that model requires a proper definition of the boundaries of the body; the centrality of the body in the calculus of both freedom and security.

First of all, let me say that pre-colonial Africa might not have been a borderless world, at least in the sense in which we have been defining borders, but where the existing borders were always porous and permeable. The business of a border is, in fact, to be crossed. That is what borders are for. There is no conceivable border outside of that principle, the law of permeability. As evidenced by traditions of long-distance trade, circulation was fundamental. It was fundamental in the production of cultural forms, of political forms, of economic and social and religious forms. The most important vehicle for transformation and change was mobility. It was not class struggles in the sense that we understand it. Mobility was the motor of any kind of social or economic or political transformation. In fact, it was the driving principle behind the delimitation and organisation of space and territories. So the primordial principle of spatial organisation was continuous movement. And this is also still part of present day culture. To stop is to run risks. You have to be on the move constantly. More and more, especially in conditions of crisis, being on the move is the very condition of your survival. If you are not on the move, the chances of survival are diminished. So dominance over sovereignty was not exclusively expressed through the control of a territory, physically marked with borders. It was not. ��How was it then? If you do not control a territory, how can you exercise sovereignty? How can you extract anything, since as far as we know, power expresses itself also, if not primarily, through one or the other form of extraction.

All of that was expressed through networks. Networks and crossroads. The importance of roads and crossroads in African literature is astounding. Read Soyinka, read Achebe, read Tutuola. Roads and crossroads are everywhere in their literature. So crossroads, flows of people and flows of nature, both in dialectical relationships because in those cosmogonies people are unthinkable without what we call nature. So while the Anthropocene���s turn seems to be a novelty in parts of our world today, we have always lived in that. It is not new. Because you cannot think of people, without thinking of nonhumans. Read Tutuola, it is a world of humans and non-humans, interacting, acting with others. I do not want to exaggerate this. Fixed geographical spaces, such as towns and villages did exist. People and things could be concentrated in a particular location. Such places could even become the origin of movement and there were links between places, such as roads and flight paths, but places were not described by points or lines. What mattered the most was the distribution of movement between places. Movement was the driving force of the production of space and movement itself, if we are to belief some of those cosmogonies. Here I have in mind the Dogon cosmogonies that were particularly studied by Marcel Griaule, or other cosmogonies in Equatorial Africa dealt with by anthropologists and historians like Jan Vansina, John M. Janzen��and others. Movement itself was not necessarily akin to displacement. What mattered the most was the extent to which flows and their intensities intersected and interacted with other flows, the new forms they could take when they intensified. Movement, especially among the Dogon, could lead to diversions, conversions and intersections. These were more important than points, lines and surfaces, which are, as we know cardinal references in western geometrics. So, what we have here is a different kind of geometry out of which concepts of borders, power, relations and separation derive.

If we want to harness alternative resources, the conceptual vocabulary type, to imagine a borderless world, here is an archive. It is not the only one. But what we harness are the archives of the world at large, and not only the western archive. In fact, the western archive does not help us to develop an idea of borderlessness. The western archive is premised on the crystallisation of the idea of a border.

In this configuration, wealth and power, or lets say wealth in people, always trumped wealth in things. There are two forms of wealth. You could be wealthy in terms of your capacity to agglomerate around your clients, family members, and so on. Or, you could be wealthy just by virtue of having accumulated a huge amount or quantity of things. So you see here a dialectics of quantities and qualities. And multiple forms of membership were always available. How is it that one belonged? Through what window is it that you can enter the house? There were multiple forms of membership, not rigid classifications where you are either a citizen or a foreigner. In between being a citizen and being a foreigner there was a whole repertoire of alternative forms of membership���building alliances through trade, marriage or religion, incorporating new commerce, refugees, asylum seekers into existing polities���that was the norm. You dominated by integrating foreigners. All kinds of foreigners. And peoplehood���not nationhood���included not only the living, but also the dead, the unborn, humans and non-humans. Community was unthinkable without some kind of foundational debt, two principal forms of debt. There is a kind of debt that is expropriatory. Some of us are indebted to banks. But in these constellations, there is a different kind of debt that is constitutive of the very basis of the relation. And it is a kind of debt that encompasses not only the living, the now, but also those who came before and those who will come after us that we have obligations to���the chain of beings that includes, once again, not only humans but animals and what we call nature.

I would like to end by putting forward a notion that I take from the Ghanaian constitution. The constitution of Ghana has developed a concept that I have not found anywhere else. It is the concept, a new right they call the right of abode as a fundamental right that they want to add to the list of traditional human rights. It seems to me that this idea of the right of abode is a cornerstone for any re-imagination of Africa as a borderless space. At a deep historical level, African and diasporic struggles for freedom and self-determination have always been intertwined with the aspiration to move unchained. Whether under conditions of slavery or under colonial rule, the loss of our sovereignty automatically resulted in the loss of our right to free movement. This is the reason why the dream of a free redeemed and mighty African nation has been inextricably linked to the recovery of the right to come and go without let or hindrance across our colossal continent. In fact our history in modernity has, to a large extent, been one of constant displacement and confinement, forced migrations and coerced labour. Think of the plantation system in the Americas and the Caribbean. Think of the Black Codes, the Pig Laws or the vagrancy status after the failure of the reconstruction in the United States in 1887. Think of the chain gangs, labouring at tasks such as road construction, ditch digging, tearing and deforestation. Think of the Code de l���indig��nat, think of the Bantustans and labour reserves in Southern Africa and of the carceral industrial complex in today���s United States of America. In each instance, to be African and to be black has meant to be consigned to one or the other of the many spaces of confinement modernity has invented.

The scramble for Africa in the 19th century, and the carving of its boundaries along colonial lines, turned the continent into a massive carceral space and each one of us into a potential illegal migrant, unable to move except under increasingly punitive conditions. As a matter of fact, entrapment became the precondition for the exploitation of our labour, which is why the struggles for emancipation and racial upliftment were so intertwined with the struggles for the right to move freely. If we want to conclude the work of decolonisation, we have to bring down colonial boundaries in our continent and turn Africa into a vast space of circulation for itself, for its descendants and for everyone who wants to tie his or her fate with our continent.

This essay appears in the latest print issue of Chimurenga Chronic, which is available for purchase here.

November 8, 2018

What to do about South Africa’s flailing economy?

Central Johannesburg. Image credit Simon Inns via Flickr.

In 2018, the��South African��economy slipped into a technical recession. StatsSA recently reported that��69,000 jobs��were shed between March and June alone.��Recent research��indicates that inequality remains startlingly high; currently 10% of the population own at least 90-95% of the country���s wealth. These statistics put the fleeting optimism generated by the so-called ���New Dawn��� into its proper perspective and can be understood within a longer trajectory of a struggling economy.

Since the transition to democracy, South Africa���s economy has been characterized by premature��de-industrialization, rising inequality, increasing��financialization, high unemployment and unsustainable levels of poverty. A��recent report��penned by the Department of Trade and Industry, the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development (CCRED), and the��SARChl��Chair in Industrial Development, underscores the failure of the democratic era to��realize�����inclusive development��� and to transform the economy in the interests of the poor.��Continuities from apartheid persist: our economy remains highly concentrated and based on capital-intensive, resource-based industries.��South Africa is now, in the words of the report, at ���a critical inflection point.���

What do we do in such a crisis?

Last weekend the head of the South African Reserve Bank,��Lesetja Kganyago,��warned against what he termed ���populist��� responses to the current economic crisis. Instead, he called for greater responsibility, accountability and restated firmly his commitment to the rigors of inflation targeting and admiration for�����fiscal discipline.���

While we always want to apply a critical lens to new policy offerings,��Kganyago���s��neat populist/sensible binary serves, in my view, to undermine the range and depth of our thinking on economic issues.

The dichotomy juxtaposes a supposedly moderate,��sensible, and��considered��orthodoxy with a reckless and morally righteous but intellectually bankrupt alternative. Any deviation from orthodoxy is made coterminous with the most extreme cases, like Zimbabwe and Venezuela.

What is populism anyway?

I have always been skeptical of the analytic value of the term ���populism.��� Indeed, what is termed ���common sense,��� and what is termed ���populism��� varies across time and space and politics. ���Common sense��� is something that is socially generated, a function of some mixture of��intellectual ingenuity, practical need and, crucially, material backing by interest groups in society.��It is the latter that is often the decisive factor in producing a seemingly��general��conventional wisdom which is in fact an ideology designed to serve��particular��interests.��What constitutes the exact mix of the former makes for an interesting empirical and historical question.

Turning to the character of economic discourse in recent memory, we know that ���common sense������at least in the Global North���during the immediate post-World War II era was based��largely��on��Keynesian economics, although a number of countries went beyond Keynes���s��more narrow��prescripts, as was the case in Sweden in the form of the��Meidner��Plan. The conventional policy blueprint��of the era, implemented to varying degrees,��included the welfare state and other ingredients of social democracy��i.e. stable and high wages, social provision of basic services including health and education, strong collective bargaining mechanisms etc.

The economic thinking of the time held that an active state was necessary to smooth over the consequences of capitalism���s inherent tendency to market failure and responded to a real need for social reconstruction after the economic collapse resulting from World War II. There was widespread determination to ensure that the social conditions that generated fascism���high unemployment being primary���would not return to disturb the peace. In addition, as��Eric Hobsbawn��reminds��us, in��the context of the Cold War, ���Western��� elites were somewhat forced to accept a more equitable capitalism, not only due to pressure from local��labor, but also as their economic model faced, if only for a brief moment, a challenge of legitimacy in the face of Soviet-style socialism.

This had profound consequences for countries in the Global South, many of whom were in the midst of independence struggles at the time. As��Thandika Mkandawire��has pointed out, the early ���development��� discourse coming from donor countries in the West followed a Keynesian bent.

Yet the so-called ���golden��� age of social democracy������golden��� due to high growth rates, relative social equality and stability achieved in the Global North in that era���collapsed in the 1970s in the wake of a crisis of profitability. The Thatcher and Reagan regimes in the UK and US consolidated a shift to a new orthodoxy. ���Common sense��� transformed into an unbridled faith in the virtues of the free-market, conceived to be welfare maximizing and naturally stable. We were now in the age of neoliberalism, backed by a corporate elite interested in securing more��favorable��terms for accumulation.

In the Global South, the dominant development thinking changed gear in-sync and was crystalized in the ���Washington Consensus��� and Structural Adjustment Programs imposed by the World Bank and IMF. South Africa had its own structural adjustment some years later with the introduction of GEAR in 1996. The collapse of the Soviet socialist experiment certainly supported the conviction that free markets were the thing of the future.

The free market ���common sense��� has, however, not lived up to its promises. Today, we are witnessing widening global inequality and economic instability. The market system seems incapable of dealing with the challenges posed by climate change, by technological change and automation. Financial deregulation has led to growing��financialization��and financial instability,��threatening another global financial crisis. Economies that have modeled themselves on neoliberal orthodoxy have stagnated and the structural adjustment programs imposed on countries in the Global South were an outright failure. In pure economic terms, China, hardly a country that subscribes to liberal orthodoxy, is one of the most dynamic economies of the modern era. The development experience of East Asian countries did not follow the script of the Washington Consensus either.

���Common sense���, in short, is proving to be nonsensical. Global politics is making this abundantly clear: the rise of Trump, Brexit, the crisis of the EU, and the rise of far-right, racial nationalism and xenophobia across the globe from Brazil to South Africa all point to the fragility of global liberal democracy. We are living in anxious and dangerous times and there can be no return to the ���common sense��� that has governed global economic discourse in the neoliberal era.

The end of the ‘End of History’

Ironically, the man who famously proclaimed that the neoliberal age would constitute ���The End of History,��� is one of those leading calls to abandon current orthodoxy. Fukuyama has gone so far as to call for a ���return to socialism��� and has admitted that Karl Marx was right about capitalism���s inherent tendency toward crisis. In��Fukuyama���s words, if socialism means:

���redistributive��programmes��that try to redress this big imbalance in both incomes and wealth that has emerged then, yes, I think not only can it come back, it ought to come back. This extended period, which started with Reagan and Thatcher, in which a certain set of ideas about the benefits of unregulated markets took hold, in many ways it’s had a disastrous effect.

And further:����

At this juncture, it seems to me that certain things Karl Marx said are turning out to be true. He talked about the crisis of overproduction��� that workers would be impoverished and there would be insufficient demand.

These are remarkable admissions from a man who was once considered to be part of the intellectual vanguard of free-market capitalism.��His words are a sign that the liberal consensus that has governed our thinking since the 1980s has disintegrated. Indeed, both the IMF and World Bank have also distanced themselves from their ���Washington Consensus��� past, the former even going so far as to publish��a critique of neoliberalism��itself.����

To be fair to Fukuyama, he was never as rosy-eyed about the fortunes of liberal democracy as his admirers and detractors let on. In his ���End of History��� he bemoans the spiritual dearth of neoliberalism, an ideology, he argued (and with hindsight rightly so), that is ripe for tribalism,��narrow identity politics, and fundamentalisms. Nonetheless, he and his fellow travelers played an important role in entrenching today���s orthodox ���common sense.��� And it is to that ���common sense��� that conservative economists in South Africa still appeal to justify their hesitancy to embrace alternative policy solutions. This deserves to be challenged.

Imagining alternatives in South Africa

Given the depth of South Africa���s social and economic crisis,��we��need to be bold about forcing through an urgent conversation about economic policy alternatives. Such open conversation is necessary precisely to avoid the recklessness that the��Kganyago��rightly worries about.

The persistent legacy of colonialism and apartheid in South Africa makes our current crisis particularly combustible. And we have already experienced a startling turn to��the politics of indigeneity and racial nationalism, sometimes, and worryingly, wrapped in��pseudo-progressive garb. The rise of xenophobia and tribalism also highlights the fragility and anxiety that define our present-day reality. In this context, it is imperative that those economists and political economists who have been exiled by ���common sense��� should find a voice.

I am hopeful and excited, therefore, about the potential of the student-led Rethinking Economics for Africa (REFA) movement,��launched this year in Johannesburg��at the same time as the launch of the Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ). REFA joins an international movement with several chapters that emerged��as a direct response to the global crisis of 2008��and the failure of mainstream neoclassical thought to account for the largest slump since the Great Depression.

There is certainly a need for a pluralist approach to economic problems as students need a wide theoretical vocabulary to confront the vast economic challenges confronting our national and global societies. It will take time but early signs suggest that future curricula may include a diversity of perspectives���Post-Keynesian, Marxist, feminist, ecological���not as mere peripheral electives, like economic history has for so long been treated, but as a central component of a rounded economics education.

A broader shift in economics discourse in South Africa must also involve discussions on alternative forms of accumulation and distribution. We certainly cannot go back and attempt to neatly copy welfare state models of old, let alone should we return to a totalitarian planned economy. Modern times need modern thinking, but something must give on the current orthodoxy.

In my view, concrete programs to mitigate the current economic crisis must include an end to austerity, a state-led productive investment program, concerted effort to attack obscene wage inequality, a wealth tax, efforts to curb illicit financial flows, and the��reorganization��of SOEs as agents of social transformation. These should all be articulated within a broader and more ambitious industrial policy, building on, but moving beyond, the DTI���s Industrial Policy Action Plans. This is not an exhaustive list. Other more creative solutions include a��Universal Basic Income (UBI), sovereign wealth funds,��cooperatives��and��solidarity economies. Surely one of the central priorities must be thinking through a ���just transition��� to avert the looming threat of climate change. These solutions should be debated and discussed as part of our everyday economic policy discourse.

So, let us listen to Fukuyama, imagine alternatives and escape the current grip of economic orthodoxy. Doing so requires, as a first step, a recognition that things simply cannot continue as they are. This is the time for creativity. If things don���t change in a conscious way, governed by democratic principles and a commitment to the empowerment and self-empowerment of the poor and��marginalized��in our society, then, indeed, history will repeat itself farcically once more.

November 7, 2018

The disastrous road of private prisons

Then-Kenyan Minister of Finance, Uhuru Kenyatta, with pop star Bob Geldof and Dominic Strauss-Kahn, then IMF Managing Director in 2010. Image credit Stephen Jaffe for IMF.

Last month Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta signed measures to restructure the Kenyan prison system. The move will merge the existing Kenyan Prison Farms Fund and Kenyan Prison Enterprise Fund into a single Kenyan Prison Enterprise Corporation. This company would expand its production to include not only agricultural products and the iconic car license plates but a number of other products in line with Kenyatta���s��Big 4 Agenda:��manufacturing, universal healthcare, affordable housing, and food security.��While media accounts referred to this as ���privatization,��� the initiative did not directly involve any private concerns.

Nonetheless, the Kenyan prison system does face serious problems typical of countries that rely on solving social problems with police repression and incarceration rather than social welfare programs. Kenya���s reliance on imprisonment means the prisons now house nearly 50,000 people in facilities designed to hold 14,000. Moreover, a number of��studies��have uncovered horrific conditions such as lack of food and rampant presence of tuberculosis, scabies and diarrhea. A 2014 survey of 18 prisons found many cells without toilets and some without running water. In several instances overcrowding was so severe individuals could not even find a private space to meet with their attorney.

Claims of torture have also emerged, as evidenced by a 2017��suit��brought by three men confined in��Manyani��prison. The men are litigating on behalf of themselves and 800 others incarcerated at��Manyani, arguing that they were subjected to repeated beatings and starvation. Ironically, during the Kenyan War of Independence (often called the ���Mau-Mau War���),��Manyani��was one of the��sites��that held alleged freedom fighters.

The truth is that for the most part Kenya is locking up people charged with petty offenses. While media may echo government assertions of a��crime wave, a study released by Chief Justice David��Maraga��in 2017 alleged that��70 per cent of cases��resulting in imprisonment involved offenses such as lack of business licenses and creating a public disturbance. Hence, the problem of overcrowding could be solved by simply finding alternative methods for addressing petty crimes, such as restorative justice or community service.

Instead, Kenyatta���s recent moves likely herald introducing private sector players into the equation. Dressed up in the rhetoric of national development, this restructuring looks much more like creating a vehicle to exploit cheap prison labor rather than address more substantive issues.

While the Kenyan prison system needs transformative change, turning to the private sector has a long global track record of failure.��A more serious turn to the private sector, such as full privatization of prisons, by Kenya may deliver profits to corrections bureaucrats and companies involved in the global prison industry, but bring little relief to those locked up in places like��Manyani.

In a country which Transparency International��ranks��as one of the most corrupt in Africa, the advent of the private prison profiteers could also likely bring kickbacks and backhanders to government officials who pave the way for private sector expansion. Private prisons��are not the solution. They make money by locking up more people and keeping them locked up for longer periods of time. They have not worked in��South Africa,��Australia, the��US��or the��UK. There is no reason to expect they will offer a recipe for Kenyatta in Kenya.

The real answer lies in cutting back on incarceration and providing resources to fight back poverty and inequality-jobs, education, housing-not building more prisons or bringing in new leadership to manage a fatally flawed system. These unfortunately are not��steps��that Uhuru Kenyatta is likely to take any time soon.

November 5, 2018

Young people lead the resistance in Sudan

Tuti Bridge. Khartoum, Sudan. Image credit Christopher Michel via Flickr.

When��we talk of the��crisis of governance��in��Sudan, the focus is usually limited to the incompetence and corruption of the ruling party. Yet,��the opposition��National��Umma��Party��(NUP)��is equally distrusted, due to its��regular��alliances with the regime, and moreover, it���s lack of��vision, a��plan��to address the��country���s��problems��and to drive meaningful change.

Since the National Congress Party (NCP) of President Omar el-Bashir��took power through a coup in 1989��(following a split with its coup partners the Islamic Movement), it��has��worked diligently to��implement��a comprehensive plan��to��weed out��all��forms��of resistance. It��introduced��the��Altamkeen��(empowerment and solidification)��Policy��and launched��a series of procedures to assure its grip on the economic and political resources of the country. It��began��by banning all political parties, professional associations, students�����unions��and civic activities. It��then��dismissed thousands of people��not aligned to the ruling party��from civil services,��including��the army and the police.��On the policy side, the��NCP��announced liberalization of trade, privatization��measures,��the��lifting��of��subsidies and��cuts to services spending.

The goal was to��simulate��the��economic conditions that empowered it��(as the Islamic Movement)��in the mid-1970s-1980s,��when��it��benefited tremendously from the corruption and profiteering��that resulted from the��liberalization policies of the International Monetary Fund��and other western backers. The economic liberalization��per the IMF framework was implemented rapidly,��resulting in the wholesale privatization.��The government sold��publicly-owned��enterprises��and companies��across sectors,��such as transportation, communications��and��agricultural,��through corrupt procedures��that benefitted��party affiliates.��Transparency and accountability were all but absent; the government controlled the banking system, limiting loans for such purchases to party loyalists.

The social impact of these policies��during��the past three decades��has been devastating. Like any country that applies economic liberalization without sequencing and��strategic��planning, the��polarization of��Sudanese society���where the opulent wealth of the few��contradicts the poverty of the majority, coupled with cuts to healthcare and education spending���is stark. Moreover, civil wars��beginning in the south of Sudan and in Darfur in the early 2000s resulted in hundreds of thousands of internally displaced and an exodus of people into poverty in and around Khartoum.��Thousands of Sudanese citizens also fled the country.

Young people in Sudan, those aged 15-35��who make up 41% of the population,��have been��particularly affected. Those who��did��not support the ruling party found it difficult to reach their potential.��Unemployment amongst youth��was��high and student resistance, for example, was not tolerated. Student��unions, professional associations and community / cultural organizations were infiltrated by cadres of the government, to ensure that they were towing the party line. The government��understood, through experience,��that these��environments were breeding grounds for resistance and community organizing.��It took further��steps��to suppress��open challenges to its rule, introducing��restrictions��on where��registered students could live (confined to campuses),��cutting��financial aid and��limiting��campus transportation.��It launched�����The Income-generating Student Project��� and campaigned for students to ���work hard.�����Access to social, cultural and political expression was restricted, beyond that which was vetted by government.��And sanctions imposed by the international community isolated the country and its young��people further.

Currently, a��key challenge��in the political landscape��is��the lack of alternatives. The Sudanese public distrust the opposition and the regime��leverages��this public opinion��by��suppressing��the��efforts of��the opposition to��mobilize��for change;��people��look to��models of change from��the past, from��revolutionary movements��that toppled two dictatorships and fought against colonialism. By��doing so they��overlook��the��reality that despite three decades of repression under el-Bashir, different��forms of activism have emerged in contemporary Sudan.

Historically,��the potent��social capital of Sudan was not taken seriously,��or even��considered��a source of strength.��Generations of political leaders��in��Sudan were educated and trained��under a colonial system,��which aimed��to create��elites��and��further distancing the political realm from the social day-to-day of the majority Sudanese.��Youth��resistance to��these imposed divisions is not new, indeed it has historical precedent dating to the 1980s at the University of Khartoum. Attempts by the then dictatorship to infiltrate and undermine efforts to challenge political authority, through student groups, affiliates and activities, was successfully neutered by a group of students who launched��the highly influential��Alheyad��(Neutralism) Movement,��which called for��transforming politics��in Sudan. The movement was successful politically and economically; it won student union elections��and��produced a significant body of literature that��significantly shifted��the language of student activism��at the University of Khartoum.

The��Alheyad��Movement had much in common with��contemporary��street initiatives. It relied on social networking, it had a fluid organization, it responded to actual needs of the society and delivered practical solutions. It financed its activities by collecting money from students, recent graduates and from��wider civil society networks. Most important,��it produced a profound critique of politics in Sudan and embodied what politics should stand for in the larger society. The reliance on social networking facilitated the movement���s initiatives and protected its members from the harassment of the government security agents; it made it easy to gather information.

The fallout of three decades of��repressive��rule and policies of structural adjustment has created a contemporary crisis in Sudan that requires similar response. The country���s youth are mobilizing.��For instance, the privatization of healthcare��means that care for certain illnesses is a luxury rather than a right.��In response, an��initiative called��Shar���i��Alhawadith��(Emergency��Street)���after the road in Khartoum where it started���identifies��sick people��in the community��who��cannot afford their��medication. The group��raises funds through social media and street canvasing, to help pay for these medications.��Another,��Adeel��Almadares��(Doing��Good for��Schools),��collects money��for��students�����school supplies��and��infrastructure��maintenance, in the case of schools that have fallen into disrepair.��Groups are mobilized to respond to��crises as they arise.��The��Nafeer��initiative��rescues and��supports��people who have been affected by��flooding. It��provides��shelter, food and labor to repair��damaged��homes, while also attending to building basic flood prevention infrastructure.��Sadagat��(Money��Donated to Help Others) works during Ramadan to secure the main meal of the day for needy families.��The importance of reviving the cultural and intellectual vibrancy of the community is also acknowledged.��Mafroosh��(Laid��Out in the��Open) organizes a monthly book��street��fair��/��exchange. It��is a popular��meeting place for youth.��Another initiative is aimed at��gathering��poets and interested people��in streets to recite and celebrate poetry.

All these��initiatives��have distinct goals,��but��also��key��features in common. First, they rely on highly celebrated values of the Sudanese society:��responding promptly��to others�����needs, for example.��If��we look to the meaning of their names we find that they are all traditional Sudanese words used to respond to help others,��inferring��selflessness, altruism and dedication to community members. Second, these��initiatives do not have systematic structures��or strict organization; they are fluid organic networks that rely on the will and interest of individuals who want to volunteer their time and energy.��Any��Sudanese youth who��is��moved by the urgency of the needs of others��is a��potential��resource��for such groups. Third, they operate without a fixed location.��They meet on the street,��usually in the tea-vendors�����spots,��sitting on��banber��(traditional stools),��which is a��common��way of socializing��and passing time in Sudan.��They rely on the��ingrained��nature of social networking of Sudanese society.��The overlapping of extended families, neighbors, relatives of neighbors, friends and co-workers creates various domains of acquaintances��and��facilitates��the��information sharing. This has become even more efficient��with the��advent of technology,��and social��media in particular.

These youth initiatives are powerful acts of resistance and resilience given the tremendous stress and lack of resources��with which the majority of��young Sudanese live daily.��The fact that they are often harassed and even arrested by the police speaks to their courage and commitment. Those who want to theorize for change and the future of governance in Sudan should take into consideration such treasures��of social capital.

Young people leads the resistance in Sudan

Tuti Bridge. Khartoum, Sudan. Image credit Christopher Michel via Flickr.

When��we talk of the��crisis of governance��in��Sudan, the focus is usually limited to the incompetence and corruption of the ruling party. Yet,��the opposition��National��Umma��Party��(NUP)��is equally distrusted, due to its��regular��alliances with the regime, and moreover, it���s lack of��vision, a��plan��to address the��country���s��problems��and to drive meaningful change.

Since the National Congress Party (NCP) of President Omar el-Bashir��took power through a coup in 1989��(following a split with its coup partners the Islamic Movement), it��has��worked diligently to��implement��a comprehensive plan��to��weed out��all��forms��of resistance. It��introduced��the��Altamkeen��(empowerment and solidification)��Policy��and launched��a series of procedures to assure its grip on the economic and political resources of the country. It��began��by banning all political parties, professional associations, students�����unions��and civic activities. It��then��dismissed thousands of people��not aligned to the ruling party��from civil services,��including��the army and the police.��On the policy side, the��NCP��announced liberalization of trade, privatization��measures,��the��lifting��of��subsidies and��cuts to services spending.

The goal was to��simulate��the��economic conditions that empowered it��(as the Islamic Movement)��in the mid-1970s-1980s,��when��it��benefited tremendously from the corruption and profiteering��that resulted from the��liberalization policies of the International Monetary Fund��and other western backers. The economic liberalization��per the IMF framework was implemented rapidly,��resulting in the wholesale privatization.��The government sold��publicly-owned��enterprises��and companies��across sectors,��such as transportation, communications��and��agricultural,��through corrupt procedures��that benefitted��party affiliates.��Transparency and accountability were all but absent; the government controlled the banking system, limiting loans for such purchases to party loyalists.

The social impact of these policies��during��the past three decades��has been devastating. Like any country that applies economic liberalization without sequencing and��strategic��planning, the��polarization of��Sudanese society���where the opulent wealth of the few��contradicts the poverty of the majority, coupled with cuts to healthcare and education spending���is stark. Moreover, civil wars��beginning in the south of Sudan and in Darfur in the early 2000s resulted in hundreds of thousands of internally displaced and an exodus of people into poverty in and around Khartoum.��Thousands of Sudanese citizens also fled the country.

Young people in Sudan, those aged 15-35��who make up 41% of the population,��have been��particularly affected. Those who��did��not support the ruling party found it difficult to reach their potential.��Unemployment amongst youth��was��high and student resistance, for example, was not tolerated. Student��unions, professional associations and community / cultural organizations were infiltrated by cadres of the government, to ensure that they were towing the party line. The government��understood, through experience,��that these��environments were breeding grounds for resistance and community organizing.��It took further��steps��to suppress��open challenges to its rule, introducing��restrictions��on where��registered students could live (confined to campuses),��cutting��financial aid and��limiting��campus transportation.��It launched�����The Income-generating Student Project��� and campaigned for students to ���work hard.�����Access to social, cultural and political expression was restricted, beyond that which was vetted by government.��And sanctions imposed by the international community isolated the country and its young��people further.

Currently, a��key challenge��in the political landscape��is��the lack of alternatives. The Sudanese public distrust the opposition and the regime��leverages��this public opinion��by��suppressing��the��efforts of��the opposition to��mobilize��for change;��people��look to��models of change from��the past, from��revolutionary movements��that toppled two dictatorships and fought against colonialism. By��doing so they��overlook��the��reality that despite three decades of repression under el-Bashir, different��forms of activism have emerged in contemporary Sudan.

Historically,��the potent��social capital of Sudan was not taken seriously,��or even��considered��a source of strength.��Generations of political leaders��in��Sudan were educated and trained��under a colonial system,��which aimed��to create��elites��and��further distancing the political realm from the social day-to-day of the majority Sudanese.��Youth��resistance to��these imposed divisions is not new, indeed it has historical precedent dating to the 1980s at the University of Khartoum. Attempts by the then dictatorship to infiltrate and undermine efforts to challenge political authority, through student groups, affiliates and activities, was successfully neutered by a group of students who launched��the highly influential��Alheyad��(Neutralism) Movement,��which called for��transforming politics��in Sudan. The movement was successful politically and economically; it won student union elections��and��produced a significant body of literature that��significantly shifted��the language of student activism��at the University of Khartoum.

The��Alheyad��Movement had much in common with��contemporary��street initiatives. It relied on social networking, it had a fluid organization, it responded to actual needs of the society and delivered practical solutions. It financed its activities by collecting money from students, recent graduates and from��wider civil society networks. Most important,��it produced a profound critique of politics in Sudan and embodied what politics should stand for in the larger society. The reliance on social networking facilitated the movement���s initiatives and protected its members from the harassment of the government security agents; it made it easy to gather information.

The fallout of three decades of��repressive��rule and policies of structural adjustment has created a contemporary crisis in Sudan that requires similar response. The country���s youth are mobilizing.��For instance, the privatization of healthcare��means that care for certain illnesses is a luxury rather than a right.��In response, an��initiative called��Shar���i��Alhawadith��(Emergency��Street)���after the road in Khartoum where it started���identifies��sick people��in the community��who��cannot afford their��medication. The group��raises funds through social media and street canvasing, to help pay for these medications.��Another,��Adeel��Almadares��(Doing��Good for��Schools),��collects money��for��students�����school supplies��and��infrastructure��maintenance, in the case of schools that have fallen into disrepair.��Groups are mobilized to respond to��crises as they arise.��The��Nafeer��initiative��rescues and��supports��people who have been affected by��flooding. It��provides��shelter, food and labor to repair��damaged��homes, while also attending to building basic flood prevention infrastructure.��Sadagat��(Money��Donated to Help Others) works during Ramadan to secure the main meal of the day for needy families.��The importance of reviving the cultural and intellectual vibrancy of the community is also acknowledged.��Mafroosh��(Laid��Out in the��Open) organizes a monthly book��street��fair��/��exchange. It��is a popular��meeting place for youth.��Another initiative is aimed at��gathering��poets and interested people��in streets to recite and celebrate poetry.

All these��initiatives��have distinct goals,��but��also��key��features in common. First, they rely on highly celebrated values of the Sudanese society:��responding promptly��to others�����needs, for example.��If��we look to the meaning of their names we find that they are all traditional Sudanese words used to respond to help others,��inferring��selflessness, altruism and dedication to community members. Second, these��initiatives do not have systematic structures��or strict organization; they are fluid organic networks that rely on the will and interest of individuals who want to volunteer their time and energy.��Any��Sudanese youth who��is��moved by the urgency of the needs of others��is a��potential��resource��for such groups. Third, they operate without a fixed location.��They meet on the street,��usually in the tea-vendors�����spots,��sitting on��banber��(traditional stools),��which is a��common��way of socializing��and passing time in Sudan.��They rely on the��ingrained��nature of social networking of Sudanese society.��The overlapping of extended families, neighbors, relatives of neighbors, friends and co-workers creates various domains of acquaintances��and��facilitates��the��information sharing. This has become even more efficient��with the��advent of technology,��and social��media in particular.

These youth initiatives are powerful acts of resistance and resilience given the tremendous stress and lack of resources��with which the majority of��young Sudanese live daily.��The fact that they are often harassed and even arrested by the police speaks to their courage and commitment. Those who want to theorize for change and the future of governance in Sudan should take into consideration such treasures��of social capital.

Youth and resistance in Sudan

Tuti Bridge. Khartoum, Sudan. Image credit Christopher Michel via Flickr.

When��we talk of the��crisis of governance��in��Sudan, the focus is usually limited to the incompetence and corruption of the ruling party. Yet,��the opposition��National��Umma��Party��(NUP)��is equally distrusted, due to its��regular��alliances with the regime, and moreover, it���s lack of��vision, a��plan��to address the��country���s��problems��and to drive meaningful change.

Since the National Congress Party (NCP) of President Omar el-Bashir��took power through a coup in 1989��(following a split with its coup partners the Islamic Movement), it��has��worked diligently to��implement��a comprehensive plan��to��weed out��all��forms��of resistance. It��introduced��the��Altamkeen��(empowerment and solidification)��Policy��and launched��a series of procedures to assure its grip on the economic and political resources of the country. It��began��by banning all political parties, professional associations, students�����unions��and civic activities. It��then��dismissed thousands of people��not aligned to the ruling party��from civil services,��including��the army and the police.��On the policy side, the��NCP��announced liberalization of trade, privatization��measures,��the��lifting��of��subsidies and��cuts to services spending.

The goal was to��simulate��the��economic conditions that empowered it��(as the Islamic Movement)��in the mid-1970s-1980s,��when��it��benefited tremendously from the corruption and profiteering��that resulted from the��liberalization policies of the International Monetary Fund��and other western backers. The economic liberalization��per the IMF framework was implemented rapidly,��resulting in the wholesale privatization.��The government sold��publicly-owned��enterprises��and companies��across sectors,��such as transportation, communications��and��agricultural,��through corrupt procedures��that benefitted��party affiliates.��Transparency and accountability were all but absent; the government controlled the banking system, limiting loans for such purchases to party loyalists.

The social impact of these policies��during��the past three decades��has been devastating. Like any country that applies economic liberalization without sequencing and��strategic��planning, the��polarization of��Sudanese society���where the opulent wealth of the few��contradicts the poverty of the majority, coupled with cuts to healthcare and education spending���is stark. Moreover, civil wars��beginning in the south of Sudan and in Darfur in the early 2000s resulted in hundreds of thousands of internally displaced and an exodus of people into poverty in and around Khartoum.��Thousands of Sudanese citizens also fled the country.

Young people in Sudan, those aged 15-35��who make up 41% of the population,��have been��particularly affected. Those who��did��not support the ruling party found it difficult to reach their potential.��Unemployment amongst youth��was��high and student resistance, for example, was not tolerated. Student��unions, professional associations and community / cultural organizations were infiltrated by cadres of the government, to ensure that they were towing the party line. The government��understood, through experience,��that these��environments were breeding grounds for resistance and community organizing.��It took further��steps��to suppress��open challenges to its rule, introducing��restrictions��on where��registered students could live (confined to campuses),��cutting��financial aid and��limiting��campus transportation.��It launched�����The Income-generating Student Project��� and campaigned for students to ���work hard.�����Access to social, cultural and political expression was restricted, beyond that which was vetted by government.��And sanctions imposed by the international community isolated the country and its young��people further.

Currently, a��key challenge��in the political landscape��is��the lack of alternatives. The Sudanese public distrust the opposition and the regime��leverages��this public opinion��by��suppressing��the��efforts of��the opposition to��mobilize��for change;��people��look to��models of change from��the past, from��revolutionary movements��that toppled two dictatorships and fought against colonialism. By��doing so they��overlook��the��reality that despite three decades of repression under el-Bashir, different��forms of activism have emerged in contemporary Sudan.

Historically,��the potent��social capital of Sudan was not taken seriously,��or even��considered��a source of strength.��Generations of political leaders��in��Sudan were educated and trained��under a colonial system,��which aimed��to create��elites��and��further distancing the political realm from the social day-to-day of the majority Sudanese.��Youth��resistance to��these imposed divisions is not new, indeed it has historical precedent dating to the 1980s at the University of Khartoum. Attempts by the then dictatorship to infiltrate and undermine efforts to challenge political authority, through student groups, affiliates and activities, was successfully neutered by a group of students who launched��the highly influential��Alheyad��(Neutralism) Movement,��which called for��transforming politics��in Sudan. The movement was successful politically and economically; it won student union elections��and��produced a significant body of literature that��significantly shifted��the language of student activism��at the University of Khartoum.

The��Alheyad��Movement had much in common with��contemporary��street initiatives. It relied on social networking, it had a fluid organization, it responded to actual needs of the society and delivered practical solutions. It financed its activities by collecting money from students, recent graduates and from��wider civil society networks. Most important,��it produced a profound critique of politics in Sudan and embodied what politics should stand for in the larger society. The reliance on social networking facilitated the movement���s initiatives and protected its members from the harassment of the government security agents; it made it easy to gather information.

The fallout of three decades of��repressive��rule and policies of structural adjustment has created a contemporary crisis in Sudan that requires similar response. The country���s youth are mobilizing.��For instance, the privatization of healthcare��means that care for certain illnesses is a luxury rather than a right.��In response, an��initiative called��Shar���i��Alhawadith��(Emergency��Street)���after the road in Khartoum where it started���identifies��sick people��in the community��who��cannot afford their��medication. The group��raises funds through social media and street canvasing, to help pay for these medications.��Another,��Adeel��Almadares��(Doing��Good for��Schools),��collects money��for��students�����school supplies��and��infrastructure��maintenance, in the case of schools that have fallen into disrepair.��Groups are mobilized to respond to��crises as they arise.��The��Nafeer��initiative��rescues and��supports��people who have been affected by��flooding. It��provides��shelter, food and labor to repair��damaged��homes, while also attending to building basic flood prevention infrastructure.��Sadagat��(Money��Donated to Help Others) works during Ramadan to secure the main meal of the day for needy families.��The importance of reviving the cultural and intellectual vibrancy of the community is also acknowledged.��Mafroosh��(Laid��Out in the��Open) organizes a monthly book��street��fair��/��exchange. It��is a popular��meeting place for youth.��Another initiative is aimed at��gathering��poets and interested people��in streets to recite and celebrate poetry.

All these��initiatives��have distinct goals,��but��also��key��features in common. First, they rely on highly celebrated values of the Sudanese society:��responding promptly��to others�����needs, for example.��If��we look to the meaning of their names we find that they are all traditional Sudanese words used to respond to help others,��inferring��selflessness, altruism and dedication to community members. Second, these��initiatives do not have systematic structures��or strict organization; they are fluid organic networks that rely on the will and interest of individuals who want to volunteer their time and energy.��Any��Sudanese youth who��is��moved by the urgency of the needs of others��is a��potential��resource��for such groups. Third, they operate without a fixed location.��They meet on the street,��usually in the tea-vendors�����spots,��sitting on��banber��(traditional stools),��which is a��common��way of socializing��and passing time in Sudan.��They rely on the��ingrained��nature of social networking of Sudanese society.��The overlapping of extended families, neighbors, relatives of neighbors, friends and co-workers creates various domains of acquaintances��and��facilitates��the��information sharing. This has become even more efficient��with the��advent of technology,��and social��media in particular.

These youth initiatives are powerful acts of resistance and resilience given the tremendous stress and lack of resources��with which the majority of��young Sudanese live daily.��The fact that they are often harassed and even arrested by the police speaks to their courage and commitment. Those who want to theorize for change and the future of governance in Sudan should take into consideration such treasures��of social capital.

Youth revive resistance in Sudan

Tuti Bridge. Khartoum, Sudan. Image credit Christopher Michel via Flickr.

When��we talk of the��crisis of governance��in��Sudan, the focus is usually limited to the incompetence and corruption of the ruling party. Yet,��the opposition��National��Umma��Party��(NUP)��is equally distrusted, due to its��regular��alliances with the regime, and moreover, it���s lack of��vision, a��plan��to address the��country���s��problems��and to drive meaningful change.

Since the National Congress Party (NCP) of President Omar el-Bashir��took power through a coup in 1989��(following a split with its coup partners the Islamic Movement), it��has��worked diligently to��implement��a comprehensive plan��to��weed out��all��forms��of resistance. It��introduced��the��Altamkeen��(empowerment and solidification)��Policy��and launched��a series of procedures to assure its grip on the economic and political resources of the country. It��began��by banning all political parties, professional associations, students�����unions��and civic activities. It��then��dismissed thousands of people��not aligned to the ruling party��from civil services,��including��the army and the police.��On the policy side, the��NCP��announced liberalization of trade, privatization��measures,��the��lifting��of��subsidies and��cuts to services spending.

The goal was to��simulate��the��economic conditions that empowered it��(as the Islamic Movement)��in the mid-1970s-1980s,��when��it��benefited tremendously from the corruption and profiteering��that resulted from the��liberalization policies of the International Monetary Fund��and other western backers. The economic liberalization��per the IMF framework was implemented rapidly,��resulting in the wholesale privatization.��The government sold��publicly-owned��enterprises��and companies��across sectors,��such as transportation, communications��and��agricultural,��through corrupt procedures��that benefitted��party affiliates.��Transparency and accountability were all but absent; the government controlled the banking system, limiting loans for such purchases to party loyalists.

The social impact of these policies��during��the past three decades��has been devastating. Like any country that applies economic liberalization without sequencing and��strategic��planning, the��polarization of��Sudanese society���where the opulent wealth of the few��contradicts the poverty of the majority, coupled with cuts to healthcare and education spending���is stark. Moreover, civil wars��beginning in the south of Sudan and in Darfur in the early 2000s resulted in hundreds of thousands of internally displaced and an exodus of people into poverty in and around Khartoum.��Thousands of Sudanese citizens also fled the country.

Young people in Sudan, those aged 15-35��who make up 41% of the population,��have been��particularly affected. Those who��did��not support the ruling party found it difficult to reach their potential.��Unemployment amongst youth��was��high and student resistance, for example, was not tolerated. Student��unions, professional associations and community / cultural organizations were infiltrated by cadres of the government, to ensure that they were towing the party line. The government��understood, through experience,��that these��environments were breeding grounds for resistance and community organizing.��It took further��steps��to suppress��open challenges to its rule, introducing��restrictions��on where��registered students could live (confined to campuses),��cutting��financial aid and��limiting��campus transportation.��It launched�����The Income-generating Student Project��� and campaigned for students to ���work hard.�����Access to social, cultural and political expression was restricted, beyond that which was vetted by government.��And sanctions imposed by the international community isolated the country and its young��people further.

Currently, a��key challenge��in the political landscape��is��the lack of alternatives. The Sudanese public distrust the opposition and the regime��leverages��this public opinion��by��suppressing��the��efforts of��the opposition to��mobilize��for change;��people��look to��models of change from��the past, from��revolutionary movements��that toppled two dictatorships and fought against colonialism. By��doing so they��overlook��the��reality that despite three decades of repression under el-Bashir, different��forms of activism have emerged in contemporary Sudan.

Historically,��the potent��social capital of Sudan was not taken seriously,��or even��considered��a source of strength.��Generations of political leaders��in��Sudan were educated and trained��under a colonial system,��which aimed��to create��elites��and��further distancing the political realm from the social day-to-day of the majority Sudanese.��Youth��resistance to��these imposed divisions is not new, indeed it has historical precedent dating to the 1980s at the University of Khartoum. Attempts by the then dictatorship to infiltrate and undermine efforts to challenge political authority, through student groups, affiliates and activities, was successfully neutered by a group of students who launched��the highly influential��Alheyad��(Neutralism) Movement,��which called for��transforming politics��in Sudan. The movement was successful politically and economically; it won student union elections��and��produced a significant body of literature that��significantly shifted��the language of student activism��at the University of Khartoum.

The��Alheyad��Movement had much in common with��contemporary��street initiatives. It relied on social networking, it had a fluid organization, it responded to actual needs of the society and delivered practical solutions. It financed its activities by collecting money from students, recent graduates and from��wider civil society networks. Most important,��it produced a profound critique of politics in Sudan and embodied what politics should stand for in the larger society. The reliance on social networking facilitated the movement���s initiatives and protected its members from the harassment of the government security agents; it made it easy to gather information.