Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 244

September 19, 2018

Guinea and the bully

Image credit Gage Skidmore via Flickr.

Now that the 2018 World Cup��fever��has passed��and France��has stopped��arguing��about the role and place of Africa in its��championship team, it is time to��focus on the future. Clearly, FIFA���s next World Cup in 2022 in Qatar has come with its fair share of��controversies, including allegations of��corruption,��homophobia��and��slavery. So has the vote for the��2026 World Cup���the three-country bid led by the USA, Mexico and Canada known as��United 2026��won out in the end over Morocco. And FIFA���s African members���one of the largest voting blocs at 54 members, one smaller than UEFA and eight more than the Asian Football Confederation.

The choice of one country���Guinea in West Africa���deserves closer scrutiny. It is also a case study in how world football works.��The announcement of the results of FIFA 68th Congress vote on the 2026 World Cup, held the day before kick-off on June 13th in Moscow, left many Guineans scratching their heads. Who did Guinea vote for? No matter how many times they rubbed their eyes or refreshed their browsers, the official tally was clear: Guinea���s vote went to��United 2026.

Feguifoot, the Guinean soccer federation, was immediately summoned for an explanation: Who did Guinea vote for? Wasn���t Guinea officially supporting fellow African nation and long-term partner Morocco���s bid? Feguifoot���s��president and Guinea���s representative with FIFA, Mamadou Antonio��Souar�����s��initial response only caused further confusion. As he��explained��a few minutes after the publication of the results: ���Guinea didn���t vote for the US-led bid. It���s not possible. There is a total confusion here with the electronic vote. A lot of complaints. Our conscience is clear.�����The point was further reiterated in an official press release from��Feguifoot��confirming Guinea���s support for the losing bid��Morocco 2026.

Yet, in Guinea, the notion that��FIFA���s electronic voting system is to blame failed to convince. In fact, FIFA promptly issued an official response ruling out any potential problem with the system, which it described as ���flawless.��� What is more, although Lebanon found itself in the exact same situation than Guinea, with officials from the��Lebanese football federation��also blaming electronic voting for their equally unexpected last minute ditch of the Moroccan bid, the Lebanese federation lodged an official complaint with FIFA. That Guinea did not attempt to��officially contest the result, despite publicly denouncing it, further raised suspicion as to what the real motives behind this last minute backflip on the sacrosanct principle of pan-African��solidarity. This turncoat move was particularly shocking coming from the country currently heading the African Union���whose official position is to support voting for African candidates��par��principe���and from a country who has in recent years developed increasingly close ties with��Morocco.��As a Guinean��official recently noted: ���During the Ebola crisis, Morocco was one of the few countries to support us. Even our soccer games were played��in Morocco [during that crisis].���

So, if FIFA ruled out an electronic malfunction and Guinea hasn���t officially tried to set the record straight, what happened? Although speculations offered widely varied with regards to where the blame might lie within��the Guinean political landscape, most if not all, appear to arch back to a single tweet: Donald Trump���s April 26��threat to those considering not backing United 2026:

The U.S. has put together a STRONG bid w/ Canada & Mexico for the 2026 World Cup. It would be a shame if countries that we always support were to lobby against the U.S. bid. Why should we be supporting these countries when they don���t support us (including at the United Nations)?

Whether this single tweet is to blame for Guinea���s flip-flop is impossible to say. However, one thing is clear: Despite claims that FIFA only represents the will of national soccer federations, and is “not the United Nations,” the US under Trump is more than willing to tie the two���FIFA and the UN���in an effort to bully his country’s way to winning a bid. For a small country like Guinea, whose standing vis-a-vis the US significantly fell after��it supported the resolution to allow the Palestinian flag to fly at the UN and whose citizens are currently not being issued any type of US visas���with the exception of close family members���any threat to its already strained relationship with the US is��to be taken��seriously.

As the fake��twitter��account of��the��Guinean president noted in response to the scandal: ���Faced with the man who twisted Little Rocket Man���s arm, what can you do?��� This recent episode in Guinea is a stark reminder that in an era when diplomatic relations are increasingly characterized by impulses, personal favors and plain-old bullying, staying close to the principle of pan-African solidarity may be a good place to start.

September 18, 2018

Unfinished business doesn’t go away

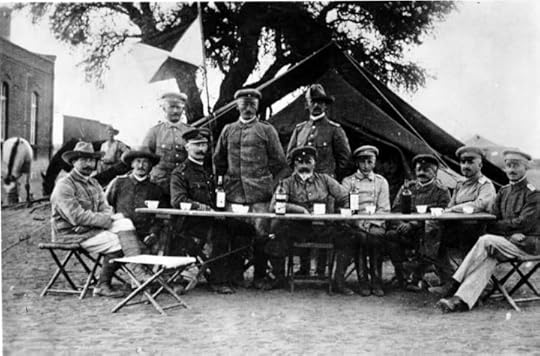

German officers in colonial South West Africa, 1904. Image credit the German Federal Archives via Wikimedia Commons.

The colonial empire of the German��Kaiserreich, which lasted from 1884 to the First World War, was decisive in Germany���s trajectory towards Nazi rule. Yet until a few years ago it hardly featured in discussions of the German past and its legacies. These days it cast long shadows especially on German-Namibian relations. It��also��remains an asymmetric relationship, based on��an��entangled history and a vital dimension of the postcolonial situation that pertains to both societies, even if in different ways.

The former ���German South West Africa��� became the independent Republic of Namibia in 1990. (Between 1915 and 1990 it was occupied by��neighboring��South Africa, then under white minority rule–Ed.) Independence opened avenues for victims of colonial crimes, including the genocide of 1904-1908, to put forward demands for recognition and redress.

In Namibia,��the German past is an integral part of the present.��In a country with one of the highest social��inequality��rates��worldwide (it competes with South Africa,��which ranks on top of the Gini-coefficient),��a tiny German-speaking minority remains on average the most privileged part of society. A skewed land distribution, where German-speaking farmers occupy large stretches of prime commercial farm land, is among the��most visible��reminders of the colonial legacy. The ���Second Land Conference��� to be held in��early October��2018��will focus��on��this continuation of colonial dispossession and appropriation, which is reproduced in current property relations.

In Germany, the situation was very different. At most, colonial memories were cultivated mainly as a romantic nostalgic celebration of a ���civilizing mission��� by colonial apologists. This changed somewhat since the turn of the millennium. Awareness campaigns by local��post-colonial and Afro-German civil society initiatives, along with the impact of��sustained activities of Namibian victim communities��managed to bring the issue through the media into the public domain.

But there are other obvious reasons why German colonialism remains on the agenda of both countries. Not by coincidence, the current German governing coalition has included in its coalition agreement,��a clause��that it will address colonial history.��Yet this is the first time something like this happened.

This commitment focuses largely on the contested issue of the restitution of stolen artifacts in German museums to countries of their origin and hitherto uncounted and mostly unidentified human remains, which in their thousands from all over the world remain in the hands��of German institutions.

Strikingly, Namibia is not mentioned specifically though many human remains held in Germany came from the then-South West Africa; collected from a variety of Namibian populations for research in human-genetic anthropology, a pseudo-science that later fed into Nazi obsessions.

In late August 2018, largely because of the work of activists in Germany and Namibia, human remains, a large number from the 1904-08 genocide were repatriated to Namibia. This was the third time since 2011 that remains were returned to Namibia. The other time was in 2014.��It is still not known how many more human remains are in German ���collections.���

In July 2015, a spokesperson for the German Foreign Office said the term genocide was applicable to what had happened in German South West Africa.��At the time, the government, in a written answer to a parliamentary question, confirmed that what happened in 1904-1908 was genocide and that this is now official German government��policy.

Soon after,��both governments appointed special envoys to negotiate how best to come to terms with this now acknowledged past. But the exchanges had a bad start: Agencies of the descendants of the main victim groups (Ovaherero,��Ovambanderu��and Nama) complained that they were not given an adequate and independent role in the proposed negotiation process. (Those representing victim groups often forget to include the Damara and San as other groups directly affected by the genocidal warfare.) Further, the German side entered the dialogue with the declared aim to negotiate an apology���as if this would only be a second step to the admission of genocide. Finally, the consequences of such an apology (i.e. the form of reparations) remain an issue. Not surprisingly, for more than a year now,��bilateral negotiations are at an impasse. Several rounds of meetings between the two special envoys and their teams remained shrouded in secrecy. Disclosure on the proceedings was highly selective. It is clear, however, that the main issues remain the full recognition of the genocide, an appropriate apology and a willingness for redress on the side of the German government.

During the ceremonies around the restitution of human remains in late August 2018, German official pronouncements once again remained evasive. Basically, despite the repatriation of human remains, no formal recognition of genocide, no official apology, and no mention at all of any redress. Notably, at the next meeting, while the Namibian delegation was led by a Cabinet Minister, it��was hosted by someone not in a cabinet post in Germany: Minister of State for International Cultural Policy in the Federal Foreign Office, Michelle M��ntefering. In her��welcoming speech, M��ntefering declared: ���When I consider the actions of Germans during the colonial period, then I stand humbled and ashamed before you.���

On 29 August, 27 human remains���which besides��Ovaherero��and Nama included four skeletons and one skull of San, then known as Bushmen���were handed over��ceremoniously in a prominent Berlin church. The speech��by M��ntefering, partly repeated her earlier welcoming remarks. Again, remorse was clearly shown, but no deep apology was extended. At the end, she ���bowed in deep mourning��� and asked, ���from the bottom of my heart for forgiveness.��� Such wording did not go beyond the individual remorse��offered��in 2004 by then German Minister Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul. The latter���s speech at the centenary commemoration of the battle at��Ohamakari, which triggered the genocidal warfare of 1904-1908, was a pioneering feat. Deeply moved, she asked for ���forgiveness of our sins.��� At the time, Wieczorek-Zeul��acted against the writ of the Foreign Office and formally, against cabinet discipline. In 2018, M��ntefering clearly reflected the line taken by her ministry.

M��ntefering once again resorted to a quaint wording: the ���atrocities committed then in the German name were, what today would be termed a genocide.��� Such verbal acrobatic relates to the Foreign Office���s stand that international law would not apply to the deeds of 1904-1908. Rather than voicing genuine regret, M��ntefering in this way stuck to the judicial niceties set out by lawyers in the Ministry where she works. Moreover, for some time, the German Foreign Office has once again retracted from the earlier acknowledgement of a genocide. However, reparation claims do not go away through denialism. They are pursued both by the Namibian government and separately also by descendants of the main victim groups, quite regardless of their controversies. Large sections of the descendants of victims of the genocide do not feel adequately represented in the bilateral negotiations between the governments. The actions by agencies of��Ovaherero��and Nama therefore include��a widely observed court case in New York.

The contested “G-word” and its implications for reparation claims were not the only sensitive issue. Before the handover of human remains was consummated, conflicts cropped up on account of the approach taken by both governments. In an obvious attempt to keep a low profile on the side of the German state, the ceremony was devolved into the responsibility of the German Protestant Church, acting jointly with the Namibian Council of Churches. Participation both in the church service and in��a vigil on the preceding evening��was declared restricted to personal invitations. This violated the fundamental principles of Christian sermons being open to all.

In another twist, the Namibian ambassador to Germany informed the post-colonial civil society group ���V��lkermord��verj��hrt��nicht,��� that its members��were no longer invited to attend��the hand-over ceremony. The activists had relentlessly campaigned for a recognition of the genocide. They were also crucial in��the renaming of some colonial street names in Berlin. The new names include figures of earlier Namibian anti-colonial resistance. To exclude them, as the Ambassador had done in his mail, from the ���friends of the Namibian government and people,��� was received as a serious insult.

The selective approach to the ceremony by both governments triggered public vigils outside the ceremonial venue in Berlin by members of the excluded civil society groups. Notably, public vigils by activists in solidarity with the victims took place in Munich, Hamburg and Leipzig, making this the first repatriation of human remains that was observed on a national scale in Germany. But not only local activists were originally excluded from the ceremonies.��Representatives��of the independent��Ovaherero��and Nama agencies as descendants of the victim groups were only allowed at the last minute to occupy some space in the ceremonies. They voiced their frustration accordingly. As Paramount Chief��Rukoro��stated��on their behalf:

How do you���the organizers of this event���think of us, Herero and Nama leaders, that our staunch supporters who were responsible for discovering these remains, are��kept outside while we are locked up inside and standing next to members of the very church that has committed genocide against our people? Don���t you ever have respect for our feelings?

The human remains were repatriated in the company of M��ntefering and the German special envoy to Windhoek. On August 31st a ceremony, with Namibia���s Vice President,��Nangolo��Mbumba, as the keynote speaker, took place in the Parliament Garden. While all participants were at pains to maintain decorum, divergent concerns were strikingly articulated.��Mbumba��followed his government���s line, in stressing national unity. He��emphasized��the need for reparations:

The Namibian Government on behalf of all its citizens who have been scarred irreparably by Germany���s colonial atrocities, especially by the 1904-08 Genocide of the��OvaHerero,��Namas��and others, will continue to seek the acknowledgement, apology and reparations from the German Government.

He also thanked:

Namibian and German NGOs, Members of Parliaments, and private individuals for their long-standing and unwavering support to the affected Namibian communities and the Namibian Government in bringing light to this dark chapter of our joint history.

Recognizing the contribution of the affected communities, he reminded them that the human remains left Namibia when it was a colony. They were now returned to a democratic country under a constitution.

M��ntefering mainly��repeated��her previous speech. In contrast, the representatives of victim communities insisted on a formal apology and reparations. Even the��Ovaherero��group that cooperates with the government negotiators as well as with Namibia���s special envoy,��stressed��they would evaluate any result against these essentials. Leaders of affected communities��insisted��that it amounted to a continuation of colonialism to relegate them to a subaltern position as members of a technical committee during the negotiation process.

By all evidence this third repatriation of human remains was another missed opportunity to move closer to some serious reconciliation over the dire past. Upon arrival of the Namibian delegation in Berlin, M��ntefering had told reporters��that Germany still has ���a lot of catching up to do in coming to terms with our colonial heritage.�����This challenge remains, and coming to terms with the past still remains unfinished business, which requires much more serious efforts towards some closure. The descendants of the victims will continue to demand justice in the sense of proper recognition of what has happened, above all the genocide, a formal apology and consequent adequate redress or reparation.��Germany and Namibia remain a far cry from a true reconciliation that would need to find expression not only in pronouncements by the political top brass but effected by the people at large from both sides.��Meanwhile, the fact remains that German diplomacy continues to bank on post-colonial asymmetry. Such asymmetry concerns both the marginal concern with (post)colonial issues in Germany, as compared to their urgency for many Namibians, and grossly uneven leverage. At least in part, this forms also an outflow of the colonial past.

Pentecostal republic

Image via Max Pixel.

Late last month, Pastor Tunde Bakare, founder of the Lagos-based Pentecostal church, The Latter Rain Assembly, and indisputably one of Nigeria���s most popular Pentecostal pastors, visited Glasgow, Scotland, at the invitation of the African Forum Scotland and Association of Nigerians in Scotland. Fielding questions from the audience after his address on ���A New Nigeria Re-engineered: The Role of Diaspora,��� (sic) Pastor Bakare disclosed a previously unknown fact about his otherwise well-documented relationship with Kaduna State Governor, Nasir el-Rufai;�����When he was contesting for the governorship of Kaduna State, I contributed N160 million [about US$450,000] to his electioneering campaign and he later paid me back,�����said Pastor Bakare.

After several Christian villages in Southern Kaduna were sacked and hundreds of villagers killed on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day 2016 in attacks believed to have been orchestrated by Fulani herdsmen, Pastor Bakare was strangely conciliatory. Temporarily repudiating the truculence that had become part of his persona, he could only vaguely assure that ���peace will return to Southern Kaduna��� based on ���some other things that I know that made me say peace will return there.���

What did Pastor Bakare know, and when did he know it? Why did he offer only to pray for the return of peace in Kaduna State following the massacre of fellow Christians when,��on a different occasion, he would, in all likelihood, have taken to the streets in protest?��To what extent did the fact that he had extended a line of credit to his ���younger brother��� Governor el-Rufai, as he disclosed to his audience in Glasgow, factor into his unusual conciliatoriness? Was he perhaps motivated by a desire to protect his financial investment by not risking his friendship with the governor, a risk that a robust denunciation of the Christmas Day killings might have triggered? Beyond Bakare, how have the affinities, networks, and alliances of the sort typified by the pastor and his Muslim governor ���brother��� shaped politics and political modalities in the Nigerian Fourth Republic?

Answers to these and corollary questions go to the heart of the intriguing imbrication of the theological and the political in contemporary Nigeria. It is also the subject of my forthcoming book,��Pentecostal Republic: Religion and the Struggle for State Power in Nigeria��(Zed Books/University of Chicago Press, 2018). Insisting that the kind of inter-religious political bromance between Bakare, a Pentecostal pastor, and Governor el-Rufai, a Muslim politician, is imperative for an understanding of the��theo-politics of the Nigerian Fourth Republic (1999- ), the book advances two complementary theses as follows:

First, I argue that the return to Civil Rule in Nigeria in 1999 also coincided with the triumph of Christianity over its historic rival, Islam, as a political force in the country. Second, I suggest that the political triumph of Christianity happened in tandem with Pentecostalism���s creeping domination, not just of Christianity, but of popular culture, politics, and the entire social imaginary. Hence, it would seem logical, as I proceed to do, to name the Fourth Republic after Pentecostalism and place it under its sign, the idea being that the entire democratic process since 1999 is in fact inexplicable without appeal to the emergent power of Pentecostalism.

While my book focuses primarily on the interplay of faith and politics in Nigeria, populated by personalities and events known to scholars and students of��Nigeriana, the nature of the subject matter means that, sociological minutiae notwithstanding, it speaks to scholars of religion and politics, and specifically Charismatic politics, both in other parts of Africa, and other regions of the world.

However, while it contributes to literature on Pentecostalism and politics in general,��Pentecostal Republic, contra the largely laudatory tendency seen in the same literature, takes a dim view of Pentecostalism���s effect on politics. Based on data from Nigeria over the span of the Fourth Republic, the conclusion is difficult to avoid that, although it has deeply��affected��the socio-political order in Nigeria, Pentecostalism, being more apologetic than critical, has largely shied away from��challenging��it.

To be sure, the Nigerian scenario as analyzed in this book is best approached as one model of the various unpredictable ways in which, globally, and in contrast to the certitudes of secularization, religion and religious agents and factors continue to affect politics. I say unpredictable because, even in a Nigerian context in which Pentecostalism has been undeniably dominant, it does not always yield dividend for those seeking to cash in politically. For instance, and as I analyze in my book, for all his witless genuflection to the leading lights of the Pentecostal elite, former president Goodluck Jonathan still failed to secure a second term in office, raising the question of how much actual influence the leading pastors wield over their congregants, whether indeed there is a ���Pentecostal vote��� to mobilize, and the extent to which serious personal divisions between members of the Pentecostal elite disturb the wisdom of assuming their coherence as a class.

Coherent or not, we might legitimately expect them to continue to exert some measure of sociopolitical influence so far as Pentecostalism remains the most ebullient movement within the Christian tradition.

September 16, 2018

Kinshasa headache

Still from Kinshasa Makambo.

As Christian��Lumu��Lukusa, a youth leader of the Democratic Republic of Congo���s (DRC) largest opposition party, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS in French), leaves the house for the umpteenth protests in 2016 against the then fifteen-year rule of President Joseph Kabila, his mother shouts: ���Lumumba died trying to free this land,��and you think you will succeed?��� Christian is one of the three Congolese activists followed by��Congolese filmmaker��Dieudo��Hamadi��for his��documentary,��Kinshasa��Makambo��(loosely meaning Kinshasa Headache), between 2016 and early 2017.

Christian���s mother has reason to be apprehensive about her son���s involvement in activism. After all, Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the DRC, died a violent death at the hands of a conspiracy of��colonialists��and their Congolese allies.

A while after Hamadi stopped filming, in August 2018, Kabila finally (and to the surprise of many) announced via��his��Minister of information Lambert Mende that he would not run for president again; almost two years beyond his constitutional mandate.

According to the DRC���s constitution,��Kabila was supposed to organize��elections and relinquish power to a new president on December 20, 2016. However, he refused to give up the reins of power, using fear, intimidation, brute force and the perversion of Congo���s Constitutional Court to hold on to the presidency. Hundreds have been killed by Kabila’s security forces, several hundred jailed through arbitrary arrests, and others have been driven into exile. The Kabila regime has beefed up its security forces, expanded the intelligence network and militarized public space throughout the country,��especially in the capital Kinshasa in order to secure his hold on power.

Apart from Christian, the two other male activists followed by Hamadi are: Ben Kabamba, who recently returned to the Congo from exile in the United States and��Jean Marie Kalonji,��released from prison��(for his anti-government organizing)��after enduring eight months of torture and uncertainty about whether he would live or die.��The immediate goal of the youth was to spark a mass uprising to remove Joseph Kabila from power if he refused to step down by December 20, 2016.

Kinshasa��Makambo��unfolds in Congo���s capital city of Kinshasa. It is a mega-city with an estimated population of 11 million inhabitants. While following the youth leaders up-close with camera in-hand,��Hamadi��not only captures the dangerous protest environment that the activists have to navigate but he also provides a glimpse into the dilapidated garbage-filled streets lined by open trench sewers that make routine daily movement and living difficult at best.��Hamadi��at great risk to himself embeds with the three youth leaders during secret meetings, preparations for demonstrations, and while they are in the midst of protests dodging live��bullets and teargas from Congo���s security forces.

In January 2015,��the Congolese youth rose up��in a spontaneous outburst to resist an electoral law that would require a census before organizing the 2016 elections, hence delaying the elections by at least four years. Since these 2015 uprisings, the Kabila regime��has systematically cracked down��on youth in Kinshasa and elsewhere in the Congo. Human Rights Watch reported that the regime has gone as far as��recruiting former M23 rebels��and giving them shoot-to-kill orders against unarmed demonstrators in Kinshasa. According to the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner���s latest report on political repression in the DRC that documents killings and human rights violations by the security forces; the right to peaceful assembly has been severely restricted. The UNHRC report document 47 killings by security forces during 2017, which included women and children. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights said that ���the systematic suppression of demonstrations, including through the use of disproportionate force, is a serious breach of international human rights law and the laws of the DRC.���

In addition to the repressive and violent conditions created by Kabila’s security forces,��Hamadi��provides some keen insights into the human and organizational challenges faced by the Congolese��youth. Without exception, the youth family members either counsel them to abandon their protests or curtail their desires to descend into the streets. He brings to the fore the incredible courage and fortitude demonstrated by Ben, Jean Marie and Christian as they confront the Kabila regime.

Whether intentional or not Hamadi reveals some of the cleavages that plague the protestors, whether it was the generational gap between��the��older��Etienne Tshisekedi��(who died during filming)��of UDPS and the youth,��or��tactical��differences��between those in civil society and political parties. In addition, the youth delve into intense debates about methods of resistance���whether to use violent or non-violent means to respond to the violence of Kabila’s security forces. Also, the efficacy of social media activism is brought into question by activist Christian in one of the exchanges among the youth. (���You are not going to change the regime by Facebook.���)

In spite of the��critique and sense of betrayal��from the youth about��Tshisekedi���s tactics, until he died, at 84, he still��represented the moral authority of the opposition. At the same, that he was still the major leader of the opposition at��such an advanced age,��provide��a glimpse into the crisis of leadership among Congo���s political class in general and the opposition in particular. It is in part, this absence of political leaders who truly embody the aspirations and interests of the masses that has enabled Kabila to maintain his hold on power. One only has to look to key Tshisekedi comrades like Joseph��Olenghankoy��and Bruno��Tshibala, who were quickly coopted by Kabila soon after Tshisekedi���s death in 2017 and are now part of Kabila���s Common Front for the Congo (FCC in French), the so-called electoral coalition.

A��shortcoming��of��the��film,��which��the��filmmaker himself��acknowledged in a recent interview��is��the lack of female representation among the protagonists. Also, Hamadi could have provided some historical background of the political environment and personal background of the three youth leaders.��For example, in the case of Ben who was��one of the key organizers of the March 15, 2015 conference in Kinshasa��and was repressed by the Kabila government, resulting in his fleeing into exile and the arrests of two of his comrades, Fred��Bauma��and Yves��Makwambala. This is valuable information that would help to contextualize Ben���s return to Kinshasa and the role he has played in the overall youth movement in the Congo.

Kinshasa��Makambo��introduces��the more radical elements of��Congo���s social justice struggle to��a��global��audience. To the extent that the struggle has been presented to the world, it��is usually by individuals who appear��comfortable with imperialism and the neoliberal order.��Hamadi offers up the radical underbelly of Congo���s social justice movement that is anti-imperialist and critical of the established neoliberal order.

Kinshasa��Makambo��also reveals the weakness of the Congolese youth movement and its inability to mobilize the masses of Congolese for radical change. This point is best captured in an exchange between Ben and Jean Marie when Ben makes a proposal, which Jean Marie characterizes as superficial. Jean Marie attempts to convince Ben that the only way they are going to succeed is to mobilize the people in the streets. The youth ultimately failed to mobilize the people to unseat Kabila at the end of his constitutional mandate in December 2016. By the end of the film, Ben returns��to exile��in Congo-Brazzaville��and Christian��is snatched��up��by Kabila���s security forces��and has been incarcerated since November 2017.

In��Kinshasa��Makambo,��Dieudo��Hamadi elevates the agency of the Congolese youth���both technically by not using a narrator and in content���struggling to fulfill the ideals and promises for the Congo that were articulated by Patrice Lumumba over a half century ago of a free and liberated Congo. It is a welcomed lens through which Congo can be viewed by the rest of the world.

September 15, 2018

Pay me what you owe me

Biggie Smalls mural on Fulton St. in Ft. Greene, Brooklyn. Image via author.

Somewhere in Bed��Stuy, an old homeless man shuffling up to me, asking for money��� Then he began to shout at me…��Pay me what you owe me motherfucker���White Tears, pg. 53

Well, the most important thing is, I want you guys to have a real precise perception of what I do, and how I make my money, and how I affect people���s lives, and how I represent people. Because it���s really important.���Diplo

Gimme��the loot!��Gimme��the loot!���Notorious B.I.G.

White��Tears,��the fifth and latest novel from Hari��Kunzru, melds social satire, cultural archeology and the supernatural in an unexpected and clarifying way. It begins by unraveling the tangled friendship between pre-millennial Brooklyn musicians Carter and Seth, then���whirling through the Manhattan fifties, with record collectors Chester Bly and��JumpJim���buries itself in the Mississippi twenties. The stakes rise as Seth, the narrator, shifts his attention from Carter to Charlie Shaw, a brilliant, forgotten bluesman.

Most reviews focus on the��excavatory��work of the novel. ���Masterly… writing about early American blues,��� writes novelist Rachel Kushner. Slate: ���…into the shadowy heart of the matter, to the poisoned center of America���s past.��� The��Los Angeles Review of Books��notes the focus on the ���prewar African-American artist��� and the similarity between famed collector Jim McKune and the character of Chester Bly.

Yet, even as the story sinks deeper into the old South, it evokes, with greater intensity, contemporary Brooklyn. Bly conjures Frank ���VoodooFunk�����Gossner, who spent a decade��acquiring rare West African vinyl��for re-issue on boutique Brooklyn labels. And Carter���s family���the��Wallaces, rich from Southern prison labor���resemble the real-life��Bronfmans, bootleggers who became conservative liquor magnates, and whose youngest members, Benjamin and Hannah, have embedded themselves in Brooklyn subculture.

Carter���s career trajectory and general worldview, though, hew closest to Diplo, the producer-celebrity who began in Philadelphia and Williamsburg loft parties. More subtly, Brooklyn-born rapper The Notorious B.I.G. (or Biggie Smalls), murdered at 24, hovers over the pages, especially over the character of Charlie Shaw.

In the familiar yet alternate world of��White Tears,��white privilege is unstable, and racial profiteers must account for their misdeeds. The ghost of Shaw seeks justice, and Carter���s family will pay. This fictional present, when juxtaposed against our own, throws new light on the tangle of American economies���music, real-estate, prisons���that continue to make meaning, and money, on black erasure.

These fuckers think this music was made in 1928, but we actually made it. We made it, fools!���White Tears, pg. 61

Every sound we explore is NEW! We are the innovators!���Diplo

Rasta don���t work for no CIA.���Bob Marley

Diplo, born Wesley��Pentz��in Mississippi, attended college in Philadelphia in the late nineties. He ran an online music forum, an avant-garde party and hung out in Brooklyn, deejaying ���electro, Top 40,��crunk, throbbing beats from Rio de Janeiro, frenetic Angolan hip-hop.���

In 2009, Major��Lazer, an unknown band with a ���Rasta commando��� logo, released ���Pon��Di Floor,��� an electro-dancehall track with kazoo sounds and stuttering drums.��The��raunchy, trippy video��became popular online, but gave no indication of who Major��Lazer��actually was.��Eventually fans learned: the black performers���dancer Skerrit��Bwoy; singer Vybz��Kartel; keyboardist Afrojack���were��not��in the band. The two��true��members, Diplo and DJ Switch (absent from video and artwork) were both white. Diplo invented the commando character with designer Ferry��Guow.

Critics balked. ���Boys travel to Jamaica, boys record with locals and make less convincing songs than the locals make on their own,��� wrote the��New York Times. A PulseRadio.net blog read:

Major��Lazer��is a ‘Jamaican commando who lost his arm in the secret Zombie War of 1984,’ now turned ‘renegade soldier for a rogue government operating in secrecy underneath the watch of M5 and the CIA’… Can���t make this shit up.

Industry figures, however, felt different. ���When Major��Lazer��released their first album and I made the connection that it was half-Diplo, I knew I had landed on something magical,��� wrote Alexander Wang. A 2010��Blackberry commercial��brought��Diplo centerstage, and soon after,��his photo essays of��Brazil��and��Trinidad��appear in��Vanity Fair. Images of him shirtless, cliff-jumping in Ibiza, mud-bathing in Israel, and in-studio with Jamaican producer Lee Perry congeal into a��book. He begins producing for pop superstars��Beyonce��and Usher.

Eventually even Justin Bieber, the white R&B singer and teen-internet superstar, approaches Diplo and keyboardist Ariel to brainstorm. “Ariel’s more anxious than me to do whatever it takes to make the Bieber record,�����he tells reporters.

A��2011 essay��by��Boima��Tucker critiques Diplo���s philosophy and practices. The��Vanity Fair��photos, he says, look ���a lot like someone looking for redemption in a pure, untouched, uncontaminated, Other.�����Diplo is undeterred. In 2013 he makes Forbes��� list of wealthiest deejays.

Illustrator Ferry��Guow discusses designing the character Major Lazer. Image credit Patricio Pomies.

Illustrator Ferry��Guow discusses designing the character Major Lazer. Image credit Patricio Pomies.In��White Tears, blond, dreadlocked���often shirtless���Carter attends school in upstate New York. His Mississippi family, rich from prison labor, has grown wealthier from private prisons. With family money, he hikes Nepal, and drives ���a bus across the Skeleton Coast in Namibia looking for surf.���

Ideology guides his taste. Black music is more ���authentic than anything made by white people.�����His views infect classmate Seth: ���Carter taught me to worship���it���s not too strong a word���what he worshipped.��� Together they ���reproduce effects heard on Lee Perry���s Black Ark studio.���

For Carter, Brooklyn is another beach to explore. After graduation, he deejays ���in basement bars, on midtown rooftops, in Bushwick warehouses,��� spinning ���regional flavors of bass and juke music. Chicago, London, Lagos, Miami.���

In a Williamsburg studio they manufacture authenticity. ���We blew up their harmonies into towering melodrama, sprayed on the fuzz. It sold out in a week.�����When a white rapper with ���James Brown dance moves��� wants to collaborate, however, Carter expresses little interest. ���We���re doing a favor even talking to him,�����Carter tells Seth.

Instead, Carter uploads a file of a street singer��that��Seth recorded. He adds a ���scuffed and faded��� label with the ���made-up��� name Charlie Shaw. ���Who knows the tradition? We do! We own that shit!��� he says.

Here misrepresentations come with consequences. Unknown attackers beat Carter in the Bronx at night. ���Charlie Shaw is real,��� an aged��JumpJim��tells Seth. ���You���ve crossed the line…���

And all the dreams of what might come after that.��The train car with my name on the side. The silk suit.���White Tears, pg. 253

It was all a dream/I used to read Word Up Magazine/Salt n��Pepa Heavy D up in the limousine.���Notorious B.I.G.

Biggie���s deep, breathy voice and storytelling gifts brought him early attention:��Pusha��T once called him a ���master painter with words.�����The bricolage of Biggie material���inspiring, bawdy, violent���arose from his Bedford-Stuyvesant childhood. His mother was a schoolteacher; yet nearby, at the��Albee Square Mall, rap stars like Eric B & Rakim hung out with neighborhood men like Killer Ben.��

On March 9th, 1997, in Los Angeles, Biggie was killed in a drive-by. His album,��Life After Death, came just two weeks later. It became the third best-selling rap album��ever. Subsequent albums (of unreleased material) sold millions. Yet, before he died, Biggie, strapped for cash,��sold half his publishing rights to his label boss.

Over the last two decades, real-estate developers have, as they remade Bedford-Stuyvesant, also remade Biggie���s image. A mural of him in a beret with his (most upbeat) lyric,��spread love it’s the Brooklyn way,��now adorns a renovated Fulton Street building. The 2011 unveiling coincided with the opening of the nearby billion-dollar Barclay���s Center.

In an��2015 essay��on the architectural, spiritual history of Brooklyn,��Kunzru��notes the new, symbolic Biggie:

A mural of his jowly face looks down on Fulton Street. Worshippers (it���s really not too strong a term) make pilgrimages to the apartment building on Saint James Place where he grew up. They take photos outside his front door. They film rap videos. On his birthday they leave flowers and pour libations of Hennessy cognac on the ground.

B.I.G. once��called his childhood home at 226 Saint James Place a ���one room shack.�����It sold, in 2013, for $825,000.

The Ft. Greene bookstore where White Tears was launched. Image via author.

The Ft. Greene bookstore where White Tears was launched. Image via author.White Tears��moves between parallel versions of Shaw���s life.��In one, a single copy of Shaw���s record survives.��In another, Shaw, murdered in prison at 27, never records. Either way, the value of his vocals exceed that of his life; death increases their value. In 1929 a producer offers ten dollars. ���Not twenty-five, but enough,��� Shaw says. Decades later, Bly offers one hundred dollars for Shaw vinyl. Online, it’s five thousand.

Seth travels to Jackson, Mississippi, seeking Shaw���s ghost near where he may have recorded. An Edwards Hotel hosted real blues sessions: in the book it appears as the Saint James. As Seth photographs dilapidated Jackson, a turbaned woman accosts him. ���We���re fascinating to you, as long as we���re safely dead,��� she says. Like Charlie Shaw, she appears in two places at once: she speaks to Seth, near the Saint James Hotel, and to Biggie-pilgrims, near Saint James Place.

���The family has decided to create a Carter Wallace Foundation… providing scholarships to deserving young students from a minority background.������White Tears, pg. 219

���The Christopher Wallace memorial foundation… will target the minds��of the youths by providing scholarships and grants.������Voletta��Wallace (Biggie���s mom)

The long shadow of Biggie also falls, unexpectedly, on Carter. The name-choice ���Carter Wallace,��� amalgamates the surnames of Biggie (Christopher Wallace) and his protege, Jay-Z (Sean Carter), forcing old plantation entanglements to the fore; narrowing the distance between a Bed-Stuy��street guy and a Southern scion. The attacks on Carter and Biggie mirror each other (each at a red light); as do their memorials.

���What was a young music producer with a glittering career doing at 3am in the industrial wastelands of Hunts Point?�����reads a headline in the novel after Carter���s beating. Biggie, however, was seen as responsible for his own murder. The��New York Times, March 10th, 1997:

In Bedford-Stuyvesant, where Mr. Wallace and his friends once dealt drugs out of a garbage can in front of a fried-chicken place on Fulton Street, his neighborhood friends and fans did not seem surprised that Mr. Wallace had died in a hail of bullets.

���Smalls��� death may in some way be payback,��� reported a young Anderson Cooper at the time.

Shaw���s ghost resists erasure by slipping into Seth���s audio files and, slowly, his thoughts.��He becomes�����stronger than death,��� as Seth begins to lose his identity:�����I pull up my shirt… I look at my stomach but I can���t tell what color it is. I can���t tell what color I am.���

White Tears��refers, on one level, to white self-pity. [Slate called it a ���Twitter-ish��jeer���]. Yet if the struggle between Shaw and Seth analogizes the larger fact of blackness pulsing under the skin of White America, then Seth���s fragility, the shredding of his racial solidity���and the attack on Carter���offer an alternate interpretation.

White, it seems, tears.

Perhaps shrines just spring up after any act of violence, anywhere there is some energy that people want to harness or ward off… Perhaps it was none of my business.���White Tears, pg. 102

I was meeting my friend/Killer Ben/in Fort Greene���Eric B. & Rakim

���The real problem isn���t too many westerners going to Africa to buy up old records,��� collector Frank��Gossner��said in 2012. The problem? ���Most African countries there are run by thugs.�����The New Yorker recently asked��Diplo about cultural appropriation: ���It���s complicated, but I don���t fucking care.��� Together,��Gossner��and Diplo represent a kind of hermetically-sealed whiteness, inured to criticism, authenticated by black symbols but with little room for black autonomy.��White Tears��punctures this cocoon, exposing its ahistorical substance and the controlling impulses of those who live within it.

It��also makes visible the violent reduction of black artists to symbols. As Bedford-Stuyvesant is destroyed and remade, images of Biggie, the conscripted patron-saint-of-gentrification, proliferate. The ghost of Charlie Shaw kicks out against this spiritual servitude.

Seth tells us that radio inventor Guglielmo Marconi��wanted�����a microphone powerful enough��� to listen to ancient sounds, which ���never completely die.�����White Tears, like Marconi���s microphone, like Seth’s equipment, picks up resonances beyond its physical design.��

The novel was���appropriately���launched at a Fort Greene bookstore across from the Spread Love building. [���Even the humblest of intersections is a crossroads, and possesses that ancient symbolic power,�����Kunzru��wrote, in his Brooklyn essay.] That the March 14th, 2017 event fell between the twentieth anniversaries of Biggie���s death (March 9th) and the release of��Life After Death��(March 27th), however, feels more mysterious.

A mile from Spread Love, on Vanderbilt and Myrtle, a lesser-known mural lives.�����BEN,�����in��terraced, metallic letters, with birth-and-death dates, accompanies the painting of a bright-faced young man with a square jaw and sharp hairline. This marks the short life of Benjamin ���Killer Ben�����O���Garro. Biggie would have heard of Ben; a popular��1991 song��mentions him by name. In 1995, according to former detective and��author Derrick Parker, they may have even clashed, months before Ben was murdered.

In July of 2015, Ben���s mural was defaced;��his eyes and life-dates sprayed with white paint. For veterans familiar with the old blood-feuds, it was a disrespect, a defiling.

Can we imagine it differently?

A Brooklyn warrior dies in battle. His ghost, trapped inside a wall, continues to watch over his village. One summer day, after many years, the warrior blinks out onto the street. He recognizes no one; no one recognizes him.

Chalk-white tears fill his eyes.

Ft. Greene mural memorializes Benjamin “Killer Ben” O’Garro. Image credit Eddie “Stats” Houghton.

Ft. Greene mural memorializes Benjamin “Killer Ben” O’Garro. Image credit Eddie “Stats” Houghton.

September 14, 2018

The ethics of political art

Still from Congo Tribunal.

How��can��arts��respond to conflict, human rights violations and impunity?��What role can��they��play in peace building and reconciliation?��These��questions��are��raised by Milo Rau���s��Congo Tribunal, a��multimedia project, consisting of a film, a book, a website, a 3D installation, an exhibition in The Hague��and, most centrally,��a performance that took place in Bukavu and Berlin.

The project��has an ambitious bottomline: ���where politics fail, only art can take over.��� The failure of politics, in this case, lie in the blatant impunity and��perpetuation��of the violence that��engulfs��eastern��Democratic Republic of the��Congo��(DRC)��since more than��twenty years.

Milo Rau is very explicit in his political aims, stating:

as a reaction to the passivity of the international community to the systematic attacks against the civil population, [the tribunal] was designed to counteract the decades of impunity in the region.

In the film, footage from the hearings in Berlin is mixed with images from��Mutarule,��Twangiza��and��Bisie, the cases under investigation, but the bulk of the film reports on the Bukavu hearings. In this��eastern Congolese town, a three-day fictitious tribunal was set up, bringing together various actors of the Congolese conflict,��including��the victims,��witnesses, civil society, opposition��and government��actors as well as other observers. Victims and human rights advocates spoke��out about��the role of government and the UN in massacres, about conflict minerals and forced displacement, divided into the three aforementioned cases.

Although the project is admittedly larger than the film (the website has recently been updated with the full-length hearings), the film��is��the primary means through which Rau communicates with his western audience.��The film,��however,��ends��up in murky ethical waters:��it��remains��deliberately��ambiguous about what is fiction and what is reality,��its producers��lack rigor in examining the cases under investigation,��and��they��selectively take responsibility (wrongly claiming a positive impact and avoiding questions about possible negative impacts) for the impact of the intervention.

Although the tribunal is��presented as theatrical��(and some elements such as a man with a clapperboard��stepping��on��the��scene sustain this), most other elements give a different impression: the stage is set up as a real tribunal with a large “Truth and Justice” banner hanging above the scene,��the hearings��mimic��court procedures, use��related idioms and are full of factual information.��Rau himself��emphasizes,��that ���there is no doubt that all witnesses and all experts are real and that they pledge to say the truth.���

In his communication, Rau has also repeatedly mentioned the participation of International Criminal Court lawyers in the court, adding to its image as a real tribunal.��While indeed some of the tribunal���s jury members have been working as civil parties at the ICC, they have certainly not partaken in the tribunal on behalf of it.

Mixing up fiction and reality in this way may not only be confusing��to��western, but also local audiences.�����People have been mobilized for the hearings and sensitized about the rights of local communities vis-��-vis the mining companies, but until today we have not seen any impact,��� a��local analyst says.��A participant in the hearings told us that he ���hopes the message will have an effect in maybe five or ten years. But so far the effect on the political situation has been nihil.��� We are willing to follow and even applaud��Rau���s reasoning��that this is a symbolic and not a pragmatic act. And��as researchers we strongly��believe it is extremely important to talk about��the ongoing violence and impunity��in Congo, to give a voice to all parties involved. However, we feel such an ambitious project should pay more attention to ethics, as it��does��intervene in real��and��ongoing conflicts and��hence��may have��more than symbolic��consequences.

Milo Rau does take��responsibility��for the real consequences of his project when it comes to positive effects, but seems less��concerned about potential negative effects. In several of his communications around the film, Rau claims responsibility for the dismissal of two ministers. However,��according to our sources��in South Kivu���s civil society,��their sidelining can be attributed to internal provincial politics,��including wrongdoings entirely unrelated to the issues dealt with by the Congo Tribunal,��and certainly not directly to their performance in the Bukavu hearings.��Moreover, local observers stress that the success of the hearings had more to do with the presence of witness opposition candidate Vital��Kamerhe��than with intrinsic enthusiasm about the project.

In general, our contacts in the region seem to be rather disappointed by the limited impact the project has had (so far) on the political situation, some of them dismissing it as a show of the bazungu. In this sense,��the director��seems to overestimate the positive effects of the project, or at least use this as a selling point towards his western audience to show that this symbolic act has had pragmatic consequences.��Potential negative��consequences, in turn, are��not addressed.��For example, one may raise questions about the protection of witnesses who (courageously) testified against their government and/or big mining corporations.

Still from Congo Tribunal.

Still from Congo Tribunal.Despite Rau���s claims that a witness protection program was set up,��this was limited to the anonymization of one witness during trial. One participant in the hearings��confessed to us: ���There was no witness protection program. They have not followed up. I was told they didn���t have the budget nor the time to do so.���

Most importantly,��Congo Tribunal has, in various ways, failed to live up to its own stated aim and rigor, namely to provide��an��explanation for the rampant impunity and to contribute to the fight against it. If a project claims to��make ���a very concrete analysis of all causes and backgrounds that led to a civil war in Congo�����and to unveil the truth, it must use rigorous methods to do so or at least try to do so. Our earlier concerns about this were��brushed away by��Milo Rau. Yet,��here lies a major problem: the film suffers��from��a striking lack of research into the cases, namely a violent massacre (the 2014��Mutarule��massacre, which has been thoroughly researched by��two��of the authors, as well as��other researchers), the role of a multinational in��eastern Congo (the industrial gold��producer��Banro��Corporation, also researched by��one of the authors), and the clash between artisanal and industrial mining interests in the world���s biggest known tin mine (Bisie).

By using cinematographic techniques and presenting particular images (for example��Mutarule, followed by an aerial view of Banro���s��Twangiza��concession) in sequence, the film��suggests��a causal relationship between these cases. Likewise, as participants of the hearings shared with us, the hearings as such did jump rather arbitrarily in between the different case��studies, and hence, in between different stereotypical registers of a much more complex setting of violent conflict.��Testimonies about the��hugely complex case of Mukungwe, for example, are conflated with��Banro���s resettlement to��Cinjira, while these are very different dynamics.

In neglecting to explain the complexities of each case-study, the film does what it aims to criticize: it explains multifaceted conflicts through a dominant and oversimplifying narrative���the��narrative on conflict minerals���which reduces the conflict in��eastern DRC to an economic war, as a struggle for��mineral��resources.

Presenting this narrative as something��new and neglected, the film and artist seem��(painfully) unaware of the long history of this narrative, as well as the��wide criticism on it. Much research has shown the inaccuracy and even harm done by this selective focus.��Similarly, while the film claims to have brought in a wide range of witnesses and experts, it is very selective in its editing and construction of its message. Experts who were critical of the��conflicts minerals��narrative���such as one of the authors��(Vogel)���have��been tackled with a series of suggestive questions during the hearings. His testimony was not��taken��into��account��in the��cinematographic edition,��for��it��might represent��too much a cognitive dissonance��to��Rau���s preformated punchline?

Rau���s wider work provocatively engages with the boundaries between fiction and reality of cruelty and violence, but���as critiques on his other pieces have shown���can border on��recuperation of this cruelty.

Here lies a major challenge: art aims to be provocative, but what if��the actual context becomes secondary to the artistic mission���however vaguely defined? This is particularly acute in extremely complicated and opaque conflicts such as the DRC. Overall, the film��leaves questions about the��project���s ethics,��and particularly,��about��the impact on its local participants, who��may be facing not just symbolic, but real consequences���in a positive as well as a negative sense.��The example of Congo Tribunal��shows that creative and active engagement with war and violence is an important function of the arts, yet we need to give justice to the complexities and risks associated with that engagement���and��Congo Tribunal should have done better in this.

September 12, 2018

Black and Black

Still from BlacknBlack.

After��fleeing political turbulence in his��in his native Ivory Coast, and��settling in Boston thirteen years ago with his American wife and young daughter, film-maker��Zadi��Zokou��noticed a certain indifference towards his African background and experience by several African Americans��he encountered.��Zadi���s��subsequent conversations and interviews with local community activists, academics, artists, and everyday people in��Boston, Philadelphia, Washington DC, as well as in Africa, revealed fascinating insights into the tensions between these communities. Even more importantly, they also uncovered a pervasive common concern to find and establish points of coherence and harmony, and revealed fascinating new perspectives on identity, culture, heritage, and history.

The result is��BlacknBlack.��The film is��first and foremost a celebration of kinship between African Americans and African immigrants who share similar ethnic origins and cultural heritage. The film also poses poignant questions about tensions and misunderstandings that often plague the relationship between these two groups.��BlacknBlack��is about the historical context of knowing each other among these two communities, and about the ongoing process of mutual learning and self-reflection. The film makes a powerful point about the importance of considering the complex histories of African and American��relationships that span several centuries and continents, coloring the interactions and mutual perceptions within the communities of African heritage.

The central theme of the film is the violent history of migration that shapes the African American experience���a legacy defined by broader global forces of slavery and colonialism.��The historical slave trade across the Atlantic resulted in forced displacement of about 12 million Sub-Saharan Africans, while also shaping the geographical and ethnic distribution of many present-day African-American communities in North America. Many recent African immigrants to the United States are war or conflict refugees, or economic migrants from countries marginalized by decades of post-colonial legacies.

While slavery was��historically��common in some African empires and kingdoms, just as in the rest of the world, its meaning was different. African systems of slavery were often defined by local socio-cultural patterns of clientage and adoptive kinship rather than large-scale commercial enterprise. That part of the history also tends to be affected by stereotypes and misconceptions. The role of some Africans as complicit in the slave trade continues to remain a painful aspect of African American history. But unscrupulous chiefs selling their fellow Africans to slave traders is not the whole story. The history also includes acts of resistance, raids and attacks on European slave traders. These important stories are not well known yet.

To come to terms with the painful historical events, reconciliatory ceremonies have been taking place recently, acknowledging the effects of the lost labor and brainpower on African communities:��There does not need to be an apology, but a discussion��about our communal history.��The film describes the emotional trips of present-day African Americans to the Cape Coast Castle of Ghana���a historical trading post used in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The film makes poignantly clear the fact that the African American experience has been largely one of displacement, extreme mobility throughout history���often resulting in��deterritorialization, and an erosion of social and cultural identity. That also reinforces mutual stereotypes. The Yoruba word��akata��of��Nigeria��originally refers to a ���cat who does not live at home, a wild cat,�����sometimes used to refer to African immigrants by the people on the continent. Those traveling to Kenya may be called by Swahili��mzungu, meaning ���wanderer,�����a word also used for white expatriates. That identification of African Americans as foreigners and outsiders when visiting their ancestral homeland can be unexpected and disheartening.��On the other hand, the recent ���Bronx culture clash�����between West African immigrants and local black Americans in��the��South Bronx illustrated the difficulties that newcomers may face when settling into local communities in American cities.��In the course of over two years, the predominantly conservative Muslim migrants��suffered��a��series of violent attacks by African American youth��in the neighborhood, resulting in several hate crime charges.

A mutual discussion of such experiences of alienation and perceived hostility can prove cathartic and constructive, as��BlacknBlack��suggests, revealing��to participants��hidden facets of their identity and self-perception. Even more importantly, it can encourage joint political and social action in today���s environments of segregation along poverty and racial lines.

The film-maker interviews several African Americans who have settled in African communities. An American woman who has lived in Ghana feels that this experience taught her more about her own identity as African American���as a unique identity in its own right, with its own language, its own culture and distinctive way of being. Both African and African American communities have evolved longitudinally, over time, and transnational contacts continue to shape both cultures. People interviewed in the film who have undergone the experience of living in both societies���in Africa as well as in America, either by birth or immigration���contemplate a deeper understanding of diversity and difference. That has also enabled them to appreciate more highly the value of mutual dialogue and common action, and address the legacies of colonialism that continue��to��shape��the African experience.

The mutual entanglements are complex. African Americans sometimes feel that Africans as foreigners have not had to deal with the history of racism in this country, and it is therefore easier for them to relate to white Americans���their foreigner status highlighting a separate identity. They perceive African immigrants as reluctant to get involved in the African American politics and civil rights struggle, while taking advantage of benefits created through those struggles by people living in this country.��At the same time, the movie recalls the history of��solidarity and collaboration between people of African heritage on both sides of the Atlantic, through the Pan-Africanist Movement.

BlacknBlack��is not just a virtual artistic project. It aims to engender new venues and live forums of discussion, and facilitate building bridges through self-reflection and mutual learning. The film is being screened on college campuses, and��inspires emotional��discussions at meetings of community groups and African diaspora organizations. In July 2018, it received the��Henry Hampton Award for Documentary Excellence��at the 2018 Roxbury International Film Festival. By encouraging people to share their experience, fears, prejudices, and expectations,��BlacknBlack��acts as a healing force towards reconciliation, and a better understanding of��oneself and the other.

Through DNA testing,��Zadi��Zokou��has found hundreds of African American relatives who are descendants of slaves. This experience will���be the subject of his next documentary.

September 11, 2018

Rwanda’s ��30 million sleeve

Image from Arsenal kit promo campaign.

As the English Premier League returns to the football pitch, Rwanda is also suiting up. Fans��can���t help noticing a�����Visit Rwanda�����logo��on the left shoulder of jerseys for Arsenal���s first, U-23 and women���s teams.��The deal, inked in May 2018 between Rwanda���s government-operated Development Board (RDB) and the London-based football club, is worth an��estimated 30 million pounds��over three years.��The��RDB officials expect that the sponsorship deal will increase the number of foreign tourists visiting the country while also promoting Rwanda as an ideal foreign direct investment��(FDI)��partner.��Critics, including members of Rwanda���s��diplomatic corps, questioned the value of deal. Why, they wondered, would a government that receives hundreds of millions of donor dollars every year strike a sponsorship deal with Arsenal?

In the wake of the deal, legislators in��the Netherlands��and the UK demanded that��their governments revisit the development aid they send to the country, raising the ire of the senior members of the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). Rwanda,��President Paul��Kagame��chastised, will spend its dollars as it sees fit. He reminded foreign critics to��mind their own business. After all, the president continued, ���we suffered genocide, you did��not.��� Since taking power in 1994, the RPF has governed on its terms and conditions, brokering no opposition to its policy choices��and��remaining allergic to criticism, particularly about human rights abuses at��home��and��abroad.

Senior government officials and regime praise-singers predictably defended the Arsenal deal: Those who��question the decision��are not friends of Rwanda but��rather are foes��who bark like dogs. Critics, they say, fail to understand the RPF spends foreign aid wisely and well. If foreigners could see how well Rwanda is governed, they would know that the Arsenal deal is a product of commercial diplomacy, intended to reduce Rwanda���s��dependency��on foreign aid. ���Visit Rwanda��� branding, they say, just makes good marketing sense to grow tourist numbers and increase revenue. With the horrors of the 1994 genocide a distant memory, Rwanda is focused on economic growth and��increasing the flow of��foreign tourist dollars is the best way to do so.��By August 2018, RDB officials proclaimed the Arsenal deal a��promising return on investment, without a shred of evidence.

A mirage of economic growth justifies the��RPF���s authoritarian rule. The Arsenal sponsorship deal is another example of the RPF���s promoted image of a self-sufficient and peaceful Rwanda, safe and prosperous under��Kagame���s��capable leadership. It is also��emblematic of regime rhetoric that seeks to sanitize the oppressive elements of RPF rule while highlighting government independence from��western��aid, even as it��remains reliant on donor dollars. For many Rwandans,��the��president is ruthlessly repressive,��willing to jail, disappear or assassinate��those who question his policy choices or style of governance.

The government public relations strategy���whether told in foreign settings or on social media���aims to craft a particular image of Rwanda��as a country on the move, fully restored from the violence of the��genocide.��Among its priorities upon taking power in August 1994, the RPF leadership strategically, and with considerable success, dispatched both the military intelligence services and public relations machinery��to craft a singular victor���s narrative��of Tutsi victims and Hutu killers. Working with expatriate journalists, aid workers and diplomats���all of whom were rightfully shocked at the human suffering the country experienced���RPF media handlers were able to quickly crafted a singular RPF-produced narrative that framed itself��as the hero��who saved Rwanda from chauvinist Hutu elites with ethnic hatred in their hearts.

Widely accepted in the West,��this narrative��has provided the government with the moral authority to remake Rwanda in its vision of benevolent leaders governing the largely uneducated and rural masses. The official PR line is that thanks to government-led initiatives to promote national unity, Rwandans now live in harmony. Ethnic labels���of being Hutu, Tutsi or��Twa���are a thing of the past, a relic of previous regimes who manipulated ethnicity for their own selfish political goals.��With ethnic unity comes economic development. The subtext is also plain: Rwanda is a good place to do business, and welcomes foreign tourists and��investment��as part of the��backbone of government plans to grow the economy. The Arsenal deal is the most recent iteration of this policy goal, offering a tidy convergence of President��Kagame���s��love of the beautiful game and the desire to transform��his��Rwanda, whatever the costs��to��the average citizen.

The strategy of economic transformation has been government policy since 2000, when the RPF first announced its plans��in the��Vision 2020��document. Designed to transform the country into a middle-income, service-based economy, Vision 2020 was a most ambitious plan, especially given Rwanda���s historical reliance on subsistence farming and foreign aid. Undeterred by such realities, the RPF would deliver a median household income target of US$1,240 and a life expectancy of��55��years (up from the 2000 baseline of US$290 and��49��years). By 2016, the impossibility of meeting Vision 2020 goals was clear. Instead of taking a hard look at the��structural economic and political limitations��of poverty alleviation in landlocked and natural resource-poor Rwanda, the��RPF refashioned Vision 2020 as a new and improved economic plan dubbed Vision 2050.

The President mapped out his government���s economic agenda for the next��34��years.��Kagame��promised to make Rwanda an upper middle-income country by 2035 and a high��income one by 2050. According to the��World Bank, middle-income countries have a��gross national income��(GNI)) of between US$4,036 and US$12,476; high-income countries have a GNI of more than US$12,476. Raising per capita incomes to these levels will be a difficult, if not impossible, order given that��Rwanda���s 2015 GNI��was just US$700.�� Never one to shy away from hard work or worry��about the��,��Kagame��stressed that the 2050 goals will require an average annual growth rate of 10 percent.��Reaching this near-unattainable goal will fall on the backs of rural farmers, as local officials do all they can to get as much as they can out of an already exhausted population. Doing more with less is a public virtue in contemporary��Rwanda, even as the��government stands accused of manipulating poverty-reduction data to rationalize its hard line on economic growth.��For the time being, the government seems more interested in producing impressive statistics over investing in a diversified pro-poor economy.

Indeed, for all of��Kagame���s��bluster about��FDI��and tourism as the basis of Rwanda���s economic transformation, the numbers are far from promising.��World Bank data��reveals that up to 2017, FDI accounts for approximately 13 percent of Rwanda���s budget, illustrating the need��for��continued foreign aid receipts. And, despite receiving an increasing number of foreign tourists since 2010, Rwanda attracts��fewer than one million��per year, raising questions about how��the hospitality��sector��can provide the��promised foreign exchange dollars.��By the end of 2014, the hotel industry registered only 19 percent occupancy, with 97 percent of beds sold to foreigners.��Major hotel chains,��such as the Radisson and other luxury names,��brought in most foreign business, while local boutique hotels, guesthouses, and hostels in Kigali and the rest of the country often go weeks without selling a room.

Rather than address these realities head-on, the government instead brushed off hospitality-sector closures as the result of��hoteliers��failure to meet��strict hygiene standards. Owners in the capital Kigali and elsewhere sang a different tune, citing an absence of skilled tourism professionals, lack of demand and��high taxes. Few dare mention that��RPF-controlled investment companies��own shares in luxury hotel properties marketing Rwanda to foreign tourists and investors.��Kagame��responded in typical fashion,��admonishing those who complain. The president���s message remained on point: Those who cannot keep up the pace of development are quickly reminded of the need for hard��work and entrepreneurial spirit to meet government demands.

The Arsenal ���Visit Rwanda��� campaign is yet another example of President��Kagame���s��grandiose vision for Rwanda, seductively disseminated as good economic stewardship.��The sponsorship deal is better read as another example of a dictator who is out-of-touch with local realities, bent on pursuing vanity projects rather than actual development. Rwandans deserve better. Sadly, there is no avenue for recourse given the RPF���s tight political grip.

September 10, 2018

Cobalt isn’t a conflict mineral

Luwowo, conflict free certified, Coltan mine near Rubaya, North Kivu March 2014. Image credit Sylvain Liechti via MONUSCO Flickr under CC license.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)���s ���conflict minerals�����(tin, tantalum, tungsten,��gold)��often appear��in��advocacy campaigns��given their importance for��western consumer electronics, but a different mineral, cobalt, has gained��media��attention��recently.

News��articles have��likened��the DRC���s cobalt to Wakanda���s��vibranium; discussed��a��Canadian alternative��to Congolese cobalt��for electric cars; and��described a��new��deal��between��Swiss company Glencore (the world���s biggest cobalt producer)��and��a Chinese firm.��Another��piece��described moves by several different Chinese corporate investors to buy in to the cobalt boom in the Kolwezi area, while the BBC recently described the situation as a�����new gold rush.�����With rapidly rising demand for��the cobalt needed to manufacture��electric cars, a new ���ethical cobalt��� scheme is being��trialed��in the DRC���s artisanal cobalt mines, with��blockchain��being used as part of these efforts.

Previously, the��US administration��announced��it����suspend��the Dodd-Frank Act���s ���conflict minerals��� provisions��for two years.��Although��Human Rights Watch��and��Amnesty��expressed concern about��suspending this��legislation, an��investigation��found��merit��in Trump���s��assertion that Dodd-Frank��caused Congolese people to lose their livelihoods.��Trump��and the Republicans��have ideological reasons for disliking Dodd-Frank:��the��cost��of compliance,��and their view that the SEC has��overstepped��its role. Yet,��the��issue should not be reduced to ���regulation��� vs. ���no regulation,�����but��seen as an opportunity to design better transnational governance to address��conflict and human rights in mining.

The ���conflict minerals��� narrative��links��the presence of armed groups in eastern DRC to��mineral riches��for which these groups loot, rape��and kill civilians.��National, regional��and international supply-chain initiatives, like Dodd-Frank,��have multiplied,��requiring��companies to disclose the fact��they use these minerals, and��make their supply chains�����conflict free.��� However,��academics��respond that��multiple��factors contribute to conflict. Armed groups��rely��on a��range��of sources of income; for some, minerals play��little or no��role.��Many��mines are not��controlled��by armed groups.��Attempts to regulate supply chains��carry potential negative consequences,��such as a��de facto��boycott of��all��minerals from the DRC,��even��where there is no conflict.

Congolese and international��researchers��have shown that Dodd-Frank has had unintended and negative consequences. Some industry actors��avoided��sourcing from the DRC, which��made artisanal miners, their dependents��and people in related industries��more��vulnerable.��Supply chain initiatives have not had a��meaningful impact��on traceability or conflict, and may even��trigger conflict��and/or��increase��the incidence of fighting, looting��and violence against civilians.

Although��efforts to demilitarize mineral supply chains��are not new,��several human rights groups want ���conflict mineral���-style supply chain traceability and due diligence��extended to��artisanal��cobalt mining. A��report��by Amnesty International and��Afrewatch��in January 2016 highlighted the poorly paid, hazardous conditions in which��children and adults work.��A November 2017��follow-up report��by��Amnesty assessed 29 companies�����responses��on��how they source their cobalt.

There is a need for systematic evaluation of��potential��risks to��ordinary people���s livelihoods��from expanding the ���conflict minerals��� category.��The negative effects reported in��Kivu provinces,��particularly the��loss of employment��for tens of thousands to��millions of miners,��suggest there is cause for concern about similar impacts��in southeastern DRC, already in economic difficulty��due to��low copper prices.��The��de facto��boycott has led to negative consequences for those in eastern DRC who depend on artisanal mining, including��loss of income;��negative effects��on child mortality and healthcare; and an��expansion��in illegal activities and smuggling.��Evidence from the��Kivus��points to the disproportionately negative impacts of supply-chain measures on artisanal miners and women in associated economic activities. In southeastern DRC, these groups are already disadvantaged, as multinational corporations have removed tens of thousands of artisanal miners from their concessions.

Recent events suggest��that a��quasi-boycott is a real possibility.��Companies��responded��to advocacy about cobalt, while the��Washington Post,��Wall Street Journal, and��Compliance Week��picked up the story. The fact that companies like Apple have��signaled��their intention to follow up on the cobalt supply chain shows the attention has had real effects. In March 2017,��Apple��announced��it had put a temporary hold on purchases of hand-mined cobalt from the DRC while it addresses working conditions and child��labor.��A recent BBC article��highlighted��that while corporate investment in the DRC���s cobalt is likely to continue growing, concerns��about��child��labor��and corruption have led investors to seek to develop cobalt mining in other countries.