Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 247

August 21, 2018

What happened on Bird Island

Bird Island in the Eastern Cape, the site of sexual crimes by apartheid government ministers. Image credit Steve McNicholas via Flickr.

It���s about my older brother, sir��� They���ve hurt him.

This startling claim is made by a young boy in a recent book,��The Lost Boys of Bird Island��by Mark Minnie and Chris Steyn. The hurt he describes results from��pedophilic��rape. The alleged perpetrators: ministers of the apartheid Nationalist government.

The pain caused by the South African apartheid government has been widely recorded. Yet, the allegations collected in this bombshell of a book suggest new depths in the moral depravity of the regime.

In recent weeks the content of the book has received��extensive media coverage��in South Africa, which took a further twist when one of the authors, former detective Mark Minnie, who co-authored the book with veteran investigative journalist Chris Steyn,��was found dead��in an��apparent suicide.

To summarize: the book details allegations against the (now deceased) former Minister of Defense in the apartheid government, Magnus Malan, his friend John Wiley���the former Minister of Environmental Affairs���as well as a third former minister (whose name was withheld in the book, but former apartheid Finance Minister��Barend du Plessis��has since, unprompted, outed himself in an��interview��in the Afrikaans newspaper��Rapport). Minnie and Steyn allege that the men were involved in a��pedophile��ring organized by a businessman from Port Elizabeth, Dave Allen, on nearby Bird Island. Allen and Wiley were well acquainted, and Allen had a government permit to harvest��guano��on Bird Island. The men���s visits to the island in a military helicopter had previously been confirmed by Malan, who maintained until his death that they were official military business visits (even though they took their fishing rods along).

It is now alleged that the group of men took young boys along on these visits, plied them with alcohol and then raped them, forcing them to participate in sex orgies. Minnie, working as a detective in Port Elizabeth, arrested Allen in 1987 on a charge of statutory rape. Allen immediately “sang like a canary,” Minnie recalled and pointed the finger at high-ranking politicians who he alleged were complicit in the abuse. Allen��died��shortly after his arrest, in an apparent suicide, before the case could go to court. Within weeks, his friend Wiley was also found dead, also apparently as a result of suicide. In a chilling resonance with Minnie���s own recent death, the book alleges that the two deaths were murders that were set up to look like suicides.

The rumors of��pedophilia��would clearly have damaged the reputation of the NP-regime at a time when the party was fighting for its survival against growing resistance in- and outside of the country. Rumors about Wiley���s alleged sexual relations with underage boys had already been circulating. Wiley was the only English-speaking Minister in PW Botha���s cabinet and apparently such a racist that he left the Anglican church after Desmond Tutu was appointed as Archbishop. Malan defended his friend (���he���s not that type of man���), but admitted that he knew about Allen���s��pedophilia. The media, then muzzled by a range of regulations under a��State of Emergency, were��warned by the police��not to speculate about Wiley���s reasons for suicide, and refused to confirm or deny that Wiley was visited by two police colonels on the morning of his death. International news agencies such as UPI��covered the issue more extensively. In his��obituary��at the occasion of Malan���s death in 2011, Chris Barron again referred to these allegations. Other journalists, such as��Colin Urquhart of the��Weekend Post��and��Martin Welz of��Rapport, also worked on the story at the time, but like Chris Steyn, they eventually abandoned the story when the trail went cold. The apartheid state���s machinery went into overdrive, and even former president PW Botha reportedly intervened to make the story go away.

The book���s description of the tight bond between Malan, Wiley, the third minister and Allen is not new news. Partly due to the NP government���s strict control of information, and partly due to newspaper editors��� hesitation and fears of prosecution, the story remained speculative. This book however now reconstructs the events in more detail, to the extent that the country���s National Prosecuting Authority��has indicated��that they would in principle be able to prosecute if presented with evidence. Both Steyn and Minnie initially worked on separate books about the story, until the publisher linked them up and they combined forces.

The book reads effortlessly, written in a pulp fiction style, with first-person narrators who become characters themselves: The flawed detective with a love of hamburgers and whisky, contending with bar fights and hangovers while chasing the bad guys. A stubborn but diligent journalist that fights for the truth, getting reined in by wimpy editors. Unidentified informants, mysterious telephone calls, disappearing dockets.

The advantage of this style is that the book sidesteps the pitfall that even excellent investigative journalism does not always manage to avoid���bombarding the reader with complex facts, dates and names that are difficult to keep track of. The disadvantage, however, is that the accessible tone can undermine the gravity and impact of the allegations���especially since the nature of the investigation, confidentiality of sources and the historic nature of the events requires a reliance on circumstantial evidence. Subsequent to the publication of the book, at least one victim���”Mr��X”���has come forward to confirm the allegations, remaining anonymous out of fear for his life.

The risk of a book like this is that reading can become a voyeuristic act, the disturbing, gruesome story reduced to��gossip. The��journalistic norm of��audi��alteram partem���”listen to the other side”���is difficult to follow in such a case. Steyn had interviewed Magnus Malan before his death and also quotes from other interviews and coverage in which he denied the allegations. While the media have covered the story extensively, Afrikaans publications in particular have also given much space and credence to denials issued by apartheid politicians such as Du Plessis,�� and their friends, such as��Wouter Basson. After weeks of coverage���and backlash from its conservative readers���Rapport���s editor��Waldimar��Pelser��backtracked in an op-ed, admitting that the newspaper should have indicated more clearly that the allegations have not been proven. On the same day, the less hesitant English-language��Sunday Times��published a full-page obituary for Minnie, interviewed a relative of another victim, and in an editorial called for justice to be done. Even decades later, discursive power relations are still playing out.��Until the lions have their own historians, indeed.

How does one read such a book in a responsible manner? Three reactions from readers are possible: anger, disgust and denial.

Anger, especially among the generation that remembers the days when Magnus Malan in his olive brown uniform was a regular and unpleasant face on our TV screens. Those on the receiving end of the military performances in the townships might potentially not be as shocked to hear about further violence from the former government���s side. It was, after all, during Malan���s tenure that the��Civil Cooperation Bureau��was founded, hit squads were sent into neighboring countries to murder activists, and��Basson���s��Project Coast��was��authorized. On the other end of the barrel, there were young white conscripts. There are still many enraged��Boetmans��who, thirty years later, live with the psychological effects rooted in the experience of being simultaneously a victim of a system that devoured its own young, and forced them to become accomplices in the systemic violence visited upon the townships, Namibia and Angola. Those men who wasted two years of their lives���and whose friends or family members lost theirs���in the service of the SADF, colloquially known as “PW, Magnus and Sons,” will probably read the book with a combination of Schadenfreude and frustration at the prospect that this story might again stay locked up in the closet of apartheid evils, rather than end up in court.

Disgust is another probable reaction to the allegations. Prudish readers might find the language crude, the topic unsavory. There is, however, no nice way to talk about rape. The revisionists will protest again that history should be left to lie: “How long do we still need to listen to these stories of apartheid?” Such a stance, at the very least, ignores�� the roots of the country���s��current pandemic of violence against women and children��due to toxic masculinity, which cannot be addressed without acknowledging its roots in the country���s centuries of violence, dispossession and oppression.

But then there are those readers already denying these revelations, and dismissing them as malicious gossip or conspiracy theories. After all, aren���t these the upstanding leaders that told us they were defending Christian civilization in Africa against the Total Onslaught of Communism? The staunch patriarchs who turned our boys into men, taught them to proudly stand to attention and take up weapons against the enemies on our borders? Why would these good men abuse vulnerable children? It seems to have escaped these readers that they base their��defence��of the alleged��paedophiles��on the exact same model of masculinity that��justified the use of shock therapy, humiliation and beatings of gay men and women in the apartheid military, headed��by Malan.

There might be potentially legitimate questions about the writers��� methods, the accuracy of every claim and the lack of concrete proof. But to acknowledge the absence of conclusive empirical proof is something completely different to greet these allegations with disbelief from the outset simply because the shocking image of molesting ministers does not fit a still deeply engrained belief among some conservative whites that their reign was at heart a moral, well-intentioned one. Perhaps there were a few bad apples in the ranks, but ultimately their intentions were good, weren���t they? A mishap here and there, but as a whole apartheid surely was not a crime against humanity,��Afriforum pleads, after all. It���s that distance between the uncle in the church pews and the minister in the uniform that Hannah Arendt described as the “banality of evil.” It is precisely because that chasm is so wide, and so difficult to bridge in a collective psyche conditioned through those very same institutions, that the initial reaction among such readers would be denial. Because an acknowledgement of this evil would then lead to the most uncomfortable question of all���how, in whatever subtle way, we too have been guilty of exploitation, suppression and amnesia. Despite its shortcomings, these ethical questions make up the book���s strongest appeal���because the writers ask those questions of themselves too.

Ultimately it is not the ruined reputation of the former ministers that we should be most concerned about. The book is dedicated to “the boys of Bird Island���and all children that suffer under those who have power over them.” If the past has taught us anything about humanity, those we ought to be lying awake over at night are this country���s lost generations. How are the violated living with their memories? Did they manage to salvage their dignity, or have they succumbed to the continued cycles of abuse South Africans are all too familiar with? How do you re-learn the language of humanity and regain trust in others once you have had a pistol shoved into you?

If nothing else, the book is a powerful metaphor for an entire system that was based precisely on the stripping of human dignity, the exercise of violence and the ruthless exploitation that this story so harrowingly recounts.

Hulle��was die��oorlog��vir��die��nuwe��dag

Vir��Harry Oppenheimer en al��sy��maats

Vir��Rembrandt van Rijn en Alfred Dunhill

En die OK Bazaars

En die hele bloody��spul��by die SAUK

Julle��was die��oorlog��vir��die CIA

Generaal��ry��rond��in��sy��blink��swart��kar

Speel��skaak��met die��kinders��van��ons��land

En��agter��hom��is die��w��reld��nou��erg��aan��die brand

Translation:

They were the battle for the new day

For Harry Oppenheimer and all his friends

For Rembrandt van Rijn and Alfred Dunhill

And the OK Bazaars

And the whole bloody SABC gang

You were the war for the CIA

General drives around in his shiny black car

Plays chess with the children of our country

And behind him the world is now on fire

(Lyrics from ���Goeienag Generaal��� (Good night General) by Piet Botha)

In the bay, only half hidden under the mist, the island is still there, and always has been.

This is a translation of the original review that appeared in the newspaper��Rapport.

A story of love in the time of the constitution

Screen shot from Whispering Truth to Power.

Thuli��Madonsela��was South Africa���s Public Protector between 2009 and 2016. She��became well known within��the��county��and beyond as a result of her report into the enormous government expenditure related to then-President Jacob Zuma���s private home in Nkandla. (He had improperly spent US$23 million to upgrade the house.)��Her subsequent battles with Zuma over the effects of her findings against him earned her the reputation of being David to the ruling party���s Goliath.

Whispering Truth to Power��is a documentary film written and directed by South African cinematographer,��Shameela��Seedat. It tells the story of��Thuli��Madonsela���s��final year in office.

On the surface, the film is a straightforward story about the woman many South Africans came to know as a quiet heroine. Yet it is some senses much more than this.��Whispering Truth to Power��also documents��Madonsela���s��family���s journey through public and private life. In so doing, it tells a deeply personal and political story about freedom, democracy and the battle over the meaning of the South African constitution through the eyes of two generations of black South Africans.

The family that is used for this examination happens to be headed by a strong, disciplined and highly successful single mother. Ms��Madonsela��is the mother to two children,��Wantu, and��Wenzile.�� Like their mother, her son and her daughter are members of a privileged political elite. Simply in the choice of subject matter then, and in the decision to explore both the political and the personal, the film confirms and upends stereotypes about single motherhood, family structure, privilege and social power.

Madonsela��is cast as both a fearless protagonist in the fight against state corruption, and as the impatient parent of a testy and at times entitled child who also happens to be a member of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). The latter is South Africa’s third largest parliamentary party, which built a reputation disrupting Zuma���s parliamentary appearances. Just as the ANC moulded��Madonsela, the EFF is now shaping her daughter. The film confirms that real life imitates art. Fiction is unnecessary when reality offers its own exquisite dramas.

South Africa always shows off on camera.��Seedat���s��shots of the impossibly blue sky and the perfectly placed��neighborhoods��around the Public Protector���s office��compound are in stark contrast to the grubbiness of the events the film describes. Seedat��does well to capture the seeming calm of a planned society where disorder erupts around the edges; where dust rises when motorcades stop in communities full of disappointed and anxious black faces. Seedat���s��camera tells us this is a country where peace is precarious and justice is elusive.

When the film begins the Public Protector has a year left in office and many obstacles to face before her time is up. She needs to��finalize a new report that looks into President Zuma���s affairs, which will be just as explosive as the Nkandla analysis. This report will focus on the ties between the Zuma and Gupta families, and allegations that the Gupta���s have used their influence to hire and fire senior members of the presidential cabinet. This includes an attempt to install a minister of finance who was on their payroll.

As��Madonsela��goes about her business in her final few months in office, she and her staff are��worried that��if they are unable to finish the state capture report it may never see the light of day. As she works to deal with her backlog of outstanding cases, it is obvious that��Madonsela��will not be replaced by a strong and independent expert. The ruling African National Congress will not make the same mistake twice.

This knowledge hangs like a sword over the events in the film. In its first third, the film gets its momentum from the fact that��Madonsela��is racing to preserve the gains she has won for the nation, as well as to protect the state capture report investigation, her final effort.

The film flips back and forth between two key aspects of��Madonsela���s��work. On the one��hand��there is the pursuit of senior politicians���the president in the main. The legal battles and the political drama around his performances in parliament make for compelling watching. At the same time, the film follows the case involving the��Bapo��bo��Mohale��community and the theft of half a billion Rand from their coffers.

The��Bapo��Bo��Mogale��are a community in the��North West province, who were recipients of royalties from��Lonmin, the mining company which was at the center of the��Marikana��massacre. In 2014, members of the community asked the Public Protector to investigate discrepancies in the amount of money in the account that was established to receive the royalties from the company. The resources were supposed to be used for their benefit.

In an emotionally devastating scene early in the film,��Madonsela��addresses the community in a packed community hall. The faces of community workers are expectant as the Protector arrives. In devastating detail, she informs them that, ���You asked us to find out how much money was in the ���D account��� for��Bapo. What had the money been spent on and who were the individuals who were signing for the money to be spent?��� The community concurs. Indeed, that is what they asked��for. Madonsela��barely pauses. She dives right in, coolly giving the bad news. ���The amount that got into the account was��R680 million. What is left is��R495,655. The biggest amount of money went to the palace. We found that a lot of money was also paid to consultants. Basically,��all of the money that you earned has been spent.���

Later in the film there is a scene in which the community confronts the Public Protector. Why, they wonder, is the process so slow when it comes to their case? Is it that their issues are less important because they are seen as local? The question contains an accusation.

The truth of course is less about��Madonsela��than it is about Zuma. The consequence of his political maneuvering was that he was able to distract��Madonsela, forcing her to spend her valuable time defending herself, tying her up in protracted legal battles, rather than devoting herself to the many injustices that prevail across the country. It was Zuma the community should have been angry with���not��Madonsela. Gracious and quiet as ever,��Madonsela��takes the heat.

The film really finds its rhythm when it begins to examine the relationship between��Madonsela��and her daughter��Wenzile. Wenzile��is a born-free. She attends the University of Pretoria and is a member of the EFF���s student structures. She is outspoken, impatient and stubborn. In many ways, mother and daughter mirror one another. There is tremendous love between them, and there are of course, raging tensions. Although the presence of the camera keeps both of them relatively restrained it is impossible to ignore their tensions.

This aspect of the film comes as a surprise and it is all the more enjoyable as a result. While it starts out as a film about accountability and governance, it turns into a story about the country South Africa is becoming.

In the relationship between the��Madonsela��women we see an intergenerational conflict that is steeped in love and doused in bitterness. We see a country in which rancor sits side by side with sweet hope.

At a practical level,��Thuli��Madonsela���s��commitment to the South African constitution gives her personal power. Her belief in the constitution has literally given her the capacity to speak to the nation and to be respected by citizens in a way few African women are afforded an opportunity to do. In this way, she is a stand-in for middle class black South African women. At the same time of course,��Madonsela���s��belief in the Constitution serves as a proxy for the beliefs of many middle class South Africans of all races.

The Bill of Rights in the South African constitution protects those who can (and have) read it. It affords them legal recourse and imbues them with the dignity of knowing when their rights have been violated. The women and men who wrote the Constitution wanted it to be the case that access to the powerful discourse of rights��would be more important than access to the courts. In other words, they had hoped that knowing your rights and being able to articulate them would inoculate you. Armed with the law, South Africans would be able to avoid and pre-empt the violation of their rights.

For people in��Madonsela���s��generation, the Constitution provides a framework for leaving the Apartheid past behind them and charting a new future, a future in which citizens are vested with individual rights.

Wenzile��clearly does not see the world in the same terms as her mother. While��Thuli��is trying to move forward, in spite of the past,��Wenzile��reaches back into the past as the basis for her anger. The future then, cannot be clean. All is not forgiven and the Constitution does not remake the nation, nor does it provide cover to the poor people it ostensibly seeks to help. For��Wenzile, the Constitution means little if it cannot provide access to land for black people, and if it cannot put an end to systemic racism and white supremacy.

Both��Madonsela��women���s views are well-rehearsed. These debates pre-date the establishment of the new South Africa. Indeed, the limits of the law, even the most progressive law, are well known. The law is by its very nature an elite instrument. In line with this, in recent years the supreme law of the land���the constitution���has come to be seen as a tool of the privileged minority. This is a complete reversal in perception from the way the Constitution was discussed in the first ten years of the democratic project. The Constitution was touted as a tool for liberating the masses���a document that finally gave black people the equality they were denied under Apartheid. It is in the tension between the first view of the constitution and the second view, between��Thuli���s��version and��Wenzile���s��version, that the film finds its steadily beating heart.

It is not lost on the viewer that��Madonsela���s��children tag along to numerous events with her. Watu has a preference for dating white. He admits this in a hilarious but troubling scene. He is affable and smart and happy to cruise along, representing the somewhat apolitical middle class black youth who have benefitted from their parent���s economic gains. Wantu��stays close to his mother because he loves her and enjoys her company. Still, there is no question that the dinners and cocktails where he joins her provide excellent networking opportunities.

Wenzile��on the other hand is more conflicted about her place at her mother���s side. She dresses up and helps to powder her mum���s face in the endless wardrobe changes required by her position as she moved from one good-bye party to the next. Through it all, it is difficult to ignore the fact that��Wenzile��belongs to a privileged minority in this country. When she sits in the back of the car alongside her mother, chatting as their expensive government car makes its way through the streets, she looks like any other well-raised beneficiary of the 1994 class project.

Like others in her cohort of course, she is more complex than this picture allows. Those looking into the car at the traffic lights will have no way of knowing that the young woman in the back has just fought with her mother, citing the Constitution to defend herself. They will have no idea that she is clutching her EFF beret. After the��hobnobbing��she had plans that involve donning the fiery accessory. I didn���t know whether to grin or grimace as I watched the scene in which��Wenzile��told her mother she was bringing the beret to her dinner party because the Constitution gave her the right to associate with anyone she pleased.

Wenzile��respects her mother but throughout the film it is obvious that she is biting her tongue. She has little time for her politics. She has bigger questions on her mid. She is occupied with race and land and decolonizing Azania.

The same dynamic is true for the elder��Madonsela. Thuli��respects her child���s political passion but she doesn���t have much patience for her rhetoric and her views about race and racism.

As the film ends,��Madonsela���s��last day has arrived. Her work is clearly not finished and she does not hand in her final State Capture report on the��Guptas. Still, her time is up and so she must let go.

We do not see a resolution to the tension that has escalated between the Public Protector and her daughter. Seedat��is wise not to try to wrap it up neatly. Their relationship���with all its contradictions and tensions, is perhaps a perfect metaphor for the state of South Africa. We are at once full of love, and bursting with rage, unable to let go of the past, and dying to be rid of it.

Their’s is a story that is still unfolding���much like the story of South Africa���s freedom fighters and their children. In the end then,��Whispering Truth to Power��is like all good stories: it is most poignant in the places where it is most restrained.

August 17, 2018

Brexit, diamonds and everyday corruption

Image credit Mark Hodson via Flickr. Creative commons.

The rise of populism across the US and Western Europe��has been well documented, but��it��is not��only an American��or European issue. The ugly nativism and anti-immigrant fervor that typify today’s right-wing populism make it clear that populism is also a concern for international relations, with implications that extend far beyond talk of trade wars and border walls.

Commentators across the UK and the USA��seemingly��struggle daily to understand and explain the ���turn to populism.�����But��those who live with endemic��political��corruption that is��often��more visible in��poorer countries��have long hoped for populist redeemers��(or really anyone)��to come in and clean up their politics too. Many commentators have accused both Donald Trump and Brexit supporters of turning the UK or US into “banana republics,” the once-proud empires now��just ordinary, well, shitholes. A byproduct of this populism has been to reveal that the corruption and kleptocracy that plague many poor countries is just as prevalent in wealthy countries. In��fact,��as is the case with the Brexit-Lesotho connections making headlines lately,��they are often��two sides of the same potentially illicitly-obtained coin.

For Basotho, the sad saga of British Brexit financier Arron Banks and his links to the leaders of the Basotho National Party (BNP) in Lesotho only heighten��the sense that the malaise of the political class in Lesotho runs deep.��The deep imbrication of Banks with the Basotho��political elite��is not a one-off. Rather it is a feature of the endemic corruption at the heart of the international political order, and a by-product of the ease with which people can move capital across borders.

The��Banks case��suggests that ���corruption��� is as much an integral element��of the political systems in the West as��it is��in African countries, and that��simple narratives about ���corrupt African leaders��� need to be complicated��(should there be��a Mo Ibrahim-equivalent prize��for American and European political or business leaders?).��With Banks operating with seeming impunity to��post large sums of cash to��leaders in Lesotho and��pour millions��of��unexplained pounds into the Brexit vote, perhaps Transparency International���s��#8 ranking��(out of 180) for the UK is not all that far from��Lesotho���s #74��after all. This intertwining of internationally-corrupt figures likely helps explain��why people across the globe are upending the political order in the hopes of finding the key to better governance.

Previous reporting had��called into question Banks��� claim that much of the money he poured into the Brexit campaign came from��a��diamond mine in Lesotho. This turned out to be patently untrue, as the mine was so far from profitable that it is about to close��operations.��Reports��also��note��that Banks��had��sent����65,000 to the personal South African bank account��of Basotho National Party (BNP) leader��(and government minister)��Thesele��John ���Maseribane in 2013, and��that Banks��had��funded��large parts of the electoral campaign of the��BNP��for the 2015 general elections in Lesotho.

It has since come out that in addition to the funds given to ‘Maseribane, who is currently Minister of Communications, Science, and Technology,��Banks��also funded��Lesotho Prime Minister Tom Thabane���s 2014-15��stay in exile in South Africa��(though Banks denied such��payments).��The reporting��linked the funds given by Banks��to ���Maseribane to the issuance of a��mining license for Banks��� company��(though��Banks, again, denied such a link).

���Maseribane,��whose father also led the BNP and��was��Deputy Prime Minister of Lesotho��from 1965��into the��1980s,��went��on camera��to deny��that the money was in any way meant to influence the issuance of a license. He claimed that the payments were normal ones to��receive from ���a friend.��� For those watching in Lesotho, where some��estimates place 57%��of the population as living below the poverty line,��a ���donation��� of that size to a politician is unfathomable. The payment suggests the��degree to which corruption is enmeshed with the highest levels of politics and government in Lesotho, and the degree to which the citizens of Lesotho are disillusioned by��a��politics��that��works��only for those involved at the highest levels.

For those who have long watched the operations of the Lesotho government, the details of this particular story are new, but the general outlines are not. Dating at least to the late 1990s with the issuances of contracts for the first phases of the��Lesotho Highlands Water Project,��outright bribery and tender collusion��(along with a cynical lack of concern for those most impacted by projects)��have long been endemic in the Mountain Kingdom. This has led to large-scale public cynicism among��Basotho about��ever getting good governance.

The recent coalition era of Lesotho politics��since 2012��has been, in many ways, a response to this popular disenchantment. Prime Minister Tom Thabane has come to power twice now in the span of 5 years with a coalition��of parties (including ���Maseribane���s BNP)��running on��an anti-corruption platform. Their argument��was that long-time Prime Minister Mosisili��and his party��had presided��over public��corruption and needed to go. The coalitions were, thus, in many ways��populist revolts��based largely in Lesotho���s urban areas��aiming��to��sweep away a corrupt old elite.��Neither of Thabane’s coalitions has effectively punished or eliminated government corruption, and��one of��the big questions��looming over current Lesotho politics is how the populace will react if corruption continues under the��rule of the��anti-corruption campaigners. When leaders cloaking themselves in populism fail to ���drain the swamp,��� what then?

The story��of a maybe-corrupt government minister in Lesotho��is in front of western viewers because of the sexy connection between Banks’ money and the Brexit campaign (with whispers of a Russian connection hanging over��it as well,��for good measure).��For much of the UK viewing public, this story is surely being seen through a partisan lens, based on personal opinion about Brexit. The Lesotho connections are��merely exotic sideshows��inserted seemingly��gratuitously into��the��key��political questions��that will define the UK for the next generation at least.

For those who hate Banks and the dark money that funded Brexit, it is, of course,��natural��that Banks went��to��far-away places to make and/or launder money, and then bring it home for nefarious purposes. For Brexit supporters, the campaign against Banks (as he himself suggests��in a��BBC interview) is one where a��successful��businessman is facing extreme questions from a partisan media about business practices in far-flung places that have no bearing on his political views in the UK. The unspoken narrative from the BBC interviewer is that were Banks to try��something��so brazen, so��clearly corrupt, in the UK, it would never fly. Thus, in all the narratives��of Banks, his��South African and Lesotho connections (his ���African connections,�����for the majority of the viewing audience) are treated��as somehow separate from his UK business operations. They work��under different standards. The implication:��Surely the open corruption��seemingly practiced by��Banks and�����Maseribane��could never happen in the UK!

And yet, the Brexit voters, the Donald Trump voters, those who put anti-immigrant populists in��power in Poland, Hungary, and Austria (to name��a few), and the seeming fatalism of voters in Lesotho are all connected through��stories like this. These individuals are reacting to stories��that play out along similar lines to the��Banks/���Maseribane��tale��where the��powerful are able to��cross borders and access capital at will. When journalists ask tough questions about where the money came from, why it crossed borders, and whose interests it served, those involved smile and plead friendship (���Maseribane:�����Can you respect my friendship with Arron?���)��or deny that anything nefarious could be going on (Banks: ���[The money] came from my��bank accounts��� from my own wealth.���). Thus,��ordinary citizens��can��reasonably conclude that these are wolves raiding the henhouse without even bothering to wear��sheep���s clothing. Why do you need��disguises��when you can simply deny that you are a wolf and��still��face��no��consequences?

In Lesotho the turn to populism and/or fatalism is more��easily understandable;�����Maseribane��all but admitted to corruption. He��did not��deny that significant money came into his personal South African bank account from��Banks, and did not deny that Banks and his associates funded their 2015 election campaign.��And yet, ���Maseribane and the BNP remain important coalition partners of the ruling government. Why would Basotho trust such a process?

Banks��treats��the British public with the same sort of disdain, arguing on camera that his ���business interests��� are what funded his public Brexit campaign, even though the reporters lay on a table in Lesotho the�����evidence�����he has put forward for��that wealth���five tiny��unprofitable��stones��dug up in��Lesotho. In treating the British public with��such��disdain, he lays bare��one of the roots of European populism���with ���leaders�����that will baldly lie about the exchange of large sums of money, why should people trust��any��leaders, save for��those claiming to��want to��overthrow the whole damned��system? With his smug smile��on camera, thus, Banks��is engaged in the process of tarnishing��not just his own reputation (if it were possible to do��that more), but also any��good name that the political classes and political ���influencers�����might have had left in the UK.

Why do people in Lesotho��distrust��their��own government��at increasing rates,��and why did Britons, in the eyes of many commentators and��economists, cut off��their��nose to spite their face in voting for Brexit?��It is in part because of individuals like Arron Banks and��Thesele�����Maseribane who freely pass large sums of money, ideas, and business permits across international borders at the same time that people��without political connections and access to large amounts of cash��are restricted from doing so. Banks and ���Maseribane get to decide who benefits from large sums of cash, while those whose lives are spent in grinding poverty in Lesotho or in a stagnating working class in the UK have no such option.��The��populist rhetoric that ordinary people don’t��have a chance to succeed because the deck is stacked in favor of the wealthy and powerful is clearly demonstrated��by their actions.

Will the Banks saga change anything in either the UK as regards Brexit or in Lesotho? In the short term it is not likely. What it will do is hammer home, yet again, that the political status quo is not working���and that it has not been working for many people for quite some time. Why should people, either in the UK or in Lesotho, trust the political class,��which seems to profit handsomely no matter what?��The saga might lead��some��to��even ponder the��question: What good is democracy if those who are leading campaigns and funneling money to support causes cannot be held accountable? Why should people vote for anyone��OTHER than someone��claiming they will clean up the system, no matter how dodgy some of their other views might be? In a world where the truth does not matter, why trust anyone?��As��Dan O’Sullivan framed Trump voters��in the US, “they do not accept life in America as it is today, and they will vote, if courted, for the one guy willing to walk through life as a six-foot upraised middle finger to everything known and despised.”

In the end, however, there��is no simple answer to the rise of the complex and nebulous phenomenon of global populism, especially given that one of the features of populism is a strongly local element. The questions��this saga raise, however, point to the��rise��of a global��political and economic��aristocracy. The intertwining of this global elite in their business and political deals that remain opaque to the great majority is a feature, not a bug, of this system.��Even if any of the investigations into Banks (including a just-confirmed one opened in��South Africa by the Hawks)��manage to dent his Teflon��persona, the damage to public institutions and popular trust in the political class has already been inflicted.

So,��why��does��Arron Banks��own��a��highly��unprofitable Lesotho diamond mine?��We��have no��conclusive answer, and despite all the high-quality journalism from good governance groups like Open Democracy and��MNN CIJ, and now��Channel 4,��the BBC, and the Mail and Guardian, we may never actually know.��That matters because it means that the good citizens of the UK and Lesotho who are not part of this elite, those who are facing the struggles of putting daily bread (or papa) on the table are getting shortchanged yet again by their political leaders. For some��the turn to populism is the only thing that is left short of nihilism or complete disenchantment from the political systems that have for too long sold them short.

August 16, 2018

Afri-comics in the afterlife

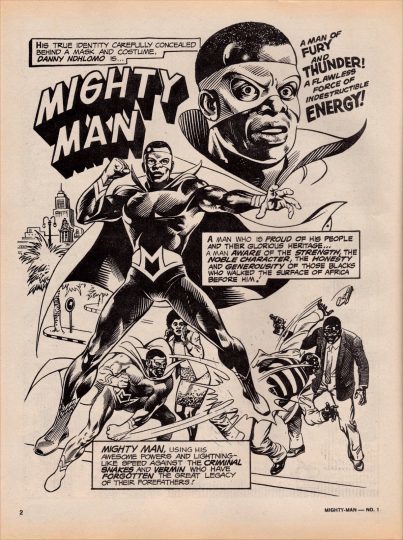

Mighty Man No.1

During the 1970s,��the��Apartheid��government���s Department of Information surreptitiously produced propaganda that masqueraded as popular entertainment. The B-Scheme films of the 1970s are familiar to historians of South African cinema, but less well known are two pro-apartheid comic book series���Mighty Man��and��Tiger Ingwe.��Mighty Man��featured a crime-busting superhero and was designed to appeal to urban audiences, while��Tiger Ingwe��targeted black readers in the rural areas, or ���homelands.���

Africa is a Country��spoke to historian William��Worger��who��is spearheading��a project��at��UCLA Library��to��compile��a complete set of digitized��Afri-comics��to make them��freely available��online.��We chatted��about their production, about the challenge of understanding how they were read when they came out, and how we��might��read them today.

Lily Saint

How did you discover these comics?

William Worger

I first visited South Africa in 1977 right after Biko was killed in detention in 1976, and I came across some references to Mighty Men then which I went back to recently in preparation for a return visit. I found some examples on the South African Comic Books website about five years ago. I put the title into eBay and that���s where a collection became available about four years ago���from an American comic collector who had a huge number of comics���those are the ones up at UCLA.

Lily Saint

How many titles did they make?

William Worger

There are 17 of Mighty Man and 17 of Tiger Ingwe. The National Library in Cape Town is, coincidentally, displaying its complete collection of Mighty Man so I am working with them to hopefully digitize the full 34 titles to make the whole set available. This display at the library suggests that people are starting to recognize that the comics deserve scholarly attention.

Lily Saint

One of the most interesting, but difficult questions to answer is how we understand readers to have responded to these when they were first published.

William Worger

I talked to a friend of mine involved in the Soweto Uprising, who would have been about 13 at the time, part of the target audience, and I asked him if he knew anything about them, and his response was ���No, I was reading newspapers!��� This is of course, in part, a response that indicates how uninteresting these comics would have been for a politically engaged young person. But I���m certain that they were read, so that���s something I want to follow up when I go to South Africa later this year and talk to a wider range of people who were children at the time, who might have come across these comics.

Lily Saint

The production process, as you explain on the UCLA Library website, tells an interesting story of collaboration between the Apartheid government, the CIA, American-based DC-Comics artists and writers, and anthropological focus groups run in South Africa.

William Worger

Yes, I want to go back and learn more about how these were created. Eschel Roodie, the Secretary of the Department of Information, describes how anthropologist Bettie van Zyl Alberts ran focus groups in South Africa before they were made, ostensibly to assess how these comics might best appeal to readers in rural and urban areas. The American DC-Comics artists (most notably the illustrator Joe Orlando) made the drawings for the comics. Oddly, under the injunctions of the South African government, they were tasked with drawing black South Africans to look different, somehow, from American comics��� depictions of black Americans. This of course begs the question: How do you make people look more African than African-American? Is there a memo somewhere that says if you change the image in a certain way you can make characters look more African than African-American?

Lily Saint

Perhaps this is done in part by the inclusion of the folktales which appear in every issue of Mighty Man apparently to affirm particular African cultural histories.

William Worger

Yes, one connection that hasn���t been made much yet is between these comics and Drum magazine. Even though no one says this, the Afri-Comics appear to be modeling themselves partly on Drum, which had a clear anti-Apartheid stance but also regularly juxtaposed its more overt political agendas with stories about sports and bodybuilding, advertisements for skin lightening creams, references to South African folklore and traditions, and features about American movie actors. Similarly Mighty Man mixes genres, but interestingly, they draw on this model with an expressly opposite pro-Apartheid aim.

Lily Saint

Roodie mentions that these comics were meant to counteract ANC/pro-Communist and SWAPO publications in circulation. Do you know about any of these?

William Worger

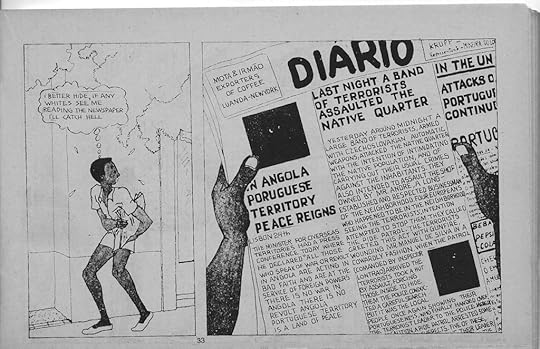

They were primarily books and radio, but I���ve been trying to hunt down any examples of pro-Communist comics that might have been circulating within Apartheid South Africa. There���s a fantastic comic that came out in Angola in 1976 after the Portuguese uprising, for instance. It���s a very graphic depiction of people struggling against colonialists���violent anti-colonial portraits. This would be something the Afri-Comics were meant to combat.

MPLA comic from 1970s Angola.

MPLA comic from 1970s Angola.Lily Saint

There are other examples of US and CIA-funded comics that circulated the whole world over, to propagate American propaganda.

William Worger

The Franklin Book Program was a front or semi-front organization which, from the 1950s through the early 1970s, put out a lot of pro-America, US Information Service/CIA funded materials. These papers are actually at Princeton Library and the inventory of the holdings there show a manifest interest in producing these kinds of propaganda for distribution worldwide.

Lily Saint

This shows us how South Africa was one node within a more global network with the set aim to circulate pro-American propaganda through cultural forms of entertainment.

William Worger

Yes, and the comics are just one part of this, but they remind me, as a scholar who largely thinks of himself as working on anti-Apartheid history, that there are other people coming at these materials from other angles, say as Cold War historians, and these materials make me realize I might need to alter my framework since we are actually doing overlapping and connected work.

Lily Saint

On the UCLA website, there���s mention of two other titles that I hadn���t heard of���Witch Doctor���s Cave and Shaka���s Love Pampata. It would be great to add collections of these to the online archive.

William Worger

Yes. Now once we have the complete set of these first two titles up online, we will suddenly have a new national archive, without a paywall, accessible to anyone, including all those people who actually can���t get to, or can���t be granted access to the holdings in the South African library���namely the bulk of the population in South Africa.

Lily Saint

It���s very ironic that these comics made cheaply for mass distribution, for people who didn���t have a lot of money or time to spend on entertainment, have this afterlife of inaccessibility and unavailability, so that only one with credentialed privilege can gain access to them.

William Worger

That���s a key point���widespread access to the internet, even despite bandwidth problems is available to almost everyone now in South Africa, and these comics provide all sorts of interesting ways into getting back into the history of Apartheid, to see how the government was manipulating people, creating images of it, etc. In my small way I���ve been trying really hard with this project to get around the gatekeepers. There���s a lot of lip service paid to decolonizing the university and the country but what really matters is how the people who were colonized themselves think of materials like these, and how they decided to handle and interpret them.

August 15, 2018

Marikana and the end of South African exceptionalism

Occupy Oakland protest in solidarity with Marikana miners on August 24, 2012, a few days after the massacre in South Africa's platinum belt. Picture: Daniel Arauz, Flickr CC.

On Thursday, August 16th, South African security forces shot dead 34 protesters at Marikana, a platinum mine, owned and operated by multinational firm Lonmin, in South Africa’s Northwest Province. The dead were rock drill operators on strike for better wages���most of them reportedly earned around the equivalent of $500 per month���and a higher standard of living.

Because of the excessive violence (video of the shootings��have gone viral), some are��making comparisons��to the tragic events of March 1960, when South African security forces, then defending the apartheid regime, murdered 69 protesters in Sharpeville, a black township south of Johannesburg. The victims in Sharpeville had gathered to protest the apartheid state’s requirement that adult Africans could only set foot in South African cities if they showed a passbook proving they were employed by local whites.

Times have changed���last Thursday’s dead had a right to vote, which many of them doubtlessly cast in support of the African National Congress, the party that has governed South Africa since apartheid’s end in 1994. Yet, once again, the South African state has shed the blood of its citizens. The similarities and differences between that half-century-old killing and this month’s are a reminder of how much South Africa has changed, and how much it hasn’t; how South Africa is singular and how it’s susceptible to the same forces of class and inequality as any other democracy.

Marikana presented familiar images���singing protesters dancing in the faces of uniformed, well-armed police, who deployed with cannon and armored vehicles, and were followed by shots and slowly settling dust. Not surprisingly, the South African government and its defenders reject the comparison. The national police commissioner��defended her officers, noting that the strike had been violent���even deadly���before the police arrived. On the day of the massacre, miners were armed, some with spear-like assegais and machetes. They had marched on the police voicing “war chants.” To be sure, the state had the preponderance of power, but this was not Sharpeville.

Yet, in its catalyzing potential, in perhaps forcing South Africa to confront a serious social ill, Marikana might still prove to be something like the post-apartheid state’s Sharpeville.

After the 1960 massacre, South Africa was kicked out of the international community: condemned at the United Nations; eventually excluded from the Olympics. Those killed at Sharpeville had been protesting in the name of freedom of movement and democratic participation in their national future, touchstones of the UN charter and of international human rights. The Cold War complicated the politics, but the world seemed largely to agree that the South African government was beyond the pale. Time and struggle undid the legacy of Sharpeville; a generation later, South African athletes featured prominently at this summer’s London Olympics, a clear reminder that South Africa is once more welcomed within the community of nations.

Human rights and democracy are wonderful and the world justly celebrates South Africa for having attained them. But the years since 1994 have demonstrated that poverty and inequality can be far wilier foes than white supremacy. South Africa was white supremacist, but it was also characterized by a particularly brutal form of capitalism, with few or no protections for workers. That latter hasn’t changed much. In the days since the massacre, Lonmin has��ordered��the miners back to work without adjusted wages; the company’s��public statements��have fretted about what it means for their shareholders’ bottom line. In the years since 1994, state violence against protesters has been frequent���witness the��2011 police killing of schoolteacher��Andries Tatane during a protest calling attention to squalid conditions in townships. In post-apartheid South Africa, Marikana was not aberrant; it was just excessive.

South Africa is now essentially a “normal” democratic country dealing with issues that,��however extreme they sometimes appear, are not actually so unique: economic inequality, labor rights abuses, corporate irresponsibility. These are not South African issues, they’re democratic issues.��Because South Africa was the last hold-out among the 20th century’s legion of racial and colonial states, and because its liberation movement took place after the international consensus on human rights and non-racism had already emerged at least at a rhetorical level, it is often treated as an exceptional case. This may have been true under apartheid, at least to some extent, but it is no longer.

The practice of treating South Africa as so different has been compounded by the myth of the rainbow nation, the singular celebrity of Nelson Mandela, and the much-touted reconciliatory nature of its transition to democracy. While there are certainly aspects of the South African story that are distinctive, Europeans and Americans have their own shameful racial histories. Aspects of South Africa’s political economy are, relatively speaking, globally commonplace: neoliberal economic policy, the predominance of multinational corporations, privatization and the weakening of labor are all��issues that South Africa is not alone in facing.

Yet many of the mainstream op-eds and editorials have��attempted��to make sense of the violence by��interpreting��it, and South Africa, in a way that emphasizes the country’s particular history, rather than considering the ways in which the killings at Marikana speak to larger international trends. The narrative of South African exceptionalism has limited our analysis of this massacre by making it difficult to see it as anything other than further evidence of the ��failure and disappointment of South African liberation. Yet Marikana is bigger than South Africa. That’s not to bash those particular writers or outlets, of course, but to note the tendency to perceive South Africa in the specific, limiting context of apartheid and its aftermath.

What can we learn from the dead in the dust in Marikana? Maybe the lessons are not so much about fulfilling the promise of post-apartheid as they are the less particular but even more daunting challenges of poverty and inequality, those faced by the entire international community. It was a great day when South Africa ended apartheid and joined the community of democratic nations, but that community has problems of its own.

Rather than judge South Africa in the wake of this 21st century Sharpeville, the rest of the world ought to ask what kind of community post-apartheid South Africa has joined.

This post was first published at the end of August 2012 on TheAtlantic.com. See also “Notes from Marikana, South Africa: The Platinum Miners��� Strike, the Massacre, and the Struggle for Equivalence.”

It feels like 1980

Image credit Tafadzwa Tarumbwa via Public Domain Pictures.

In 1980, for the first time, Zimbabweans���yes, Zimbabweans, no longer involuntary subjects in the rogue nation of Rhodesia���lined up by their millions to cast their vote in their first democratic election in the newly freed nation.

Back then, Robert��Mugabe was a national��and pan-African hero: a leader of a successful anti-colonial movement. Bob Marley sang at the inauguration, which, in hindsight, may as well have been a coronation.��Mugabe��would, through a brutality that mirrored, and then surpassed that of the racist white supremacist Ian Smith, continue to rule over (not lead) the country to��an unconscionable decline for 37��years.

It would be��Emmerson��Mnangagwa��(known��simply��in��Zimbabwe��as ���E.D.���),��Mugabe���s��longtime brutal bodyguard-turned-second-in-charge, who would bring about his ousting in the surprise military backed ���not-coup��� in late 2017.

The crowds that gathered around the army tanks in the streets in November 2017, celebrating the end of the Mugabe era, rivaled those that hailed his ascendancy a generation earlier. Despite E.D.���s fingerprints over every single oppressive act since Independence, including the genocidal ethnic cleansing ���Gukurahundi��� that consolidated Mugabe���s power in the early 1980s, 37��years of Mugabe made��anyone��look preferable. Reminiscent of the US��� rose-colored nostalgia over the war-crime ridden presidency of George W Bush in light of the catastrophe that is Donald J Trump, E.D. wasn���t Mugabe, and at least for a short while, that made him David to his mentor���s Goliath.

Late last month, in a previously unimaginable election in which Mugabe���s name was not on the ballot, Zimbabweans stood in line to vote again.��Mugabe, uncomfortable on the sidelines,��inserted himself into the election on the eve of the historical vote.��He��stirred up confusion and controversy in the waning hours of the campaign during a press conference, declaring,�����I can���t vote a party or those in power who are the people that have brought me to this state. I can���t��vote for them. I have said the two��women presidential candidates don���t offer very much. So what is there? It���s just��[opposition leader Nelson]��Chamisa.��� The delivery��was��given in��his personal brand of sardonic humor. Even the press corps couldn���t help but laugh. How ironic that Mugabe, after��ruling��Zanu-PF��for so long��and mentoring his imposed predecessor, would not vote for them. But by aligning himself with the opposition,��Mugabe��tainted the��appeal��of the alternative. Genius. He���s still the most skilled politician in the nation, even from a deserved forced retirement.

Speaking to voters throughout the July 30 elections, my prevailing sense was ���hope.�����Nelson��Chamisa, the challenger most likely to succeed amongst the 22 candidates running against the incumbent E.D.,��had broad support in the densely populated urban areas.��Forty��years old, charismatic and personable,��Chamisa, who survived an ugly leadership battle after the death of��his��predecessor (and thorn in Mugabe���s side) Morgan Tsvangirai, has been Obama-esque��in his popularity.��Despite a demonstrated tendency toward hyperbole and outright lies, his support (as evidenced by the crowds at his rallies) was��huge, lively and excited.

���It feels like 1980,��� one woman said.

If ever there was an image to capture the mood of Zimbabweans��on the eve of the polls,��that was it.��It��remained��unclear whether Nelson��Chamisa���s��relative youth represented��the ushering in of a new era of transformative leadership, or the beginning��of another long dictatorship, but��for many, the hope was��enough. Obama��campaigned on ���Hope and change���;��Zimbabweans, beaten down by a generation of oppressive��leadership, were more tempered:��Hope, then change.

The results, revealed as a slow motion sledgehammer to��the��optimism of an emotionally, economically and physically beaten down populous, were expected by the cynical. ZANU-PF, the ongoing ruling party,��prolonged the status quo with a parliamentary majority, and E.D. legitimized his��ill-gotten��presidency with an��electoral victory.

Hope turned to despair, anger and resignation, in��predictable��stages, and the supremacy of the ruling party was established by all means possible. The image of a soldier, in fatigues, kneeling in the streets of the capital city,��taking directed aim at retreating crowds with an AK-47,��will long haunt every Zimbabwean, especially the families of the four protestors whose lives were taken from them by the army they were celebrating less than a year ago.

Every country has a��myth that it believes of itself. For Zimbabweans, after��suffering through the Mugabe era without a civil war, the myth is ���Zimbabweans are a peaceful people,�����(with the ever present unspoken ���unlike other African countries.���)��The post-election violence, then, was especially shocking and grievous to the national psyche. Yet the notion of inherent peacefulness is a myth, as Zimbabwean writer��Rudo��Mudiwa (@seka_hako) wrote in an insightful Twitter thread responding to the state���s violence following the election results:

The notion that Zimbabwe is inherently peaceful is a fiction that only serves to cover up the state’s violence. We see the limits of that language, and who it protects, in moments like this.��That fiction that we are better than other African countries because our politics are less violent (���this is not Mogadishu,��� someone said) also prevents us from learning from them. I’ve been struck today by how many other Africans were retweeting us and saying they know how we feel. I remember being at a conference a few years ago and someone was talking about “post-war African societies” and mentioned Zimbabwe. And I was taken aback because all my life I never considered us to be one of those types of countries. We are not peaceful or peace loving. So much of the lives that people live are characterized by slow violence. Look at our newspapers���weekly accounts of deadly crashes caused by bad roads, preventable hospital deaths, diseases caused by water contamination, many more things we can’t even see. That is not peace!��The government has made us all invested on preserving a nonexistent peace when what we really need, and what they have to deliver, is freedom.

���It feels like 1980,��� someone said before the election. Freedom felt attainable then, when it was clothed in change. It visited, but never stayed. So we���re back to hope. As��Chamisa��contests the election results in the courts to mixed reactions��from a populous desperate for peace��and prosperity, Zimbabweans are once again forced to find a new home for their hope. True change, at least in the government, looks less likely, and thus the new old resting place for hope deferred lies either in a judiciary system with dubious legitimacy or in the false change represented by a new-ish��President with an old agenda.

For Zimbabweans, we���re back where we started, then. Hope, no change. Still.

August 14, 2018

Everything happening to you is a wound

Still from Sisters of the Wilderness.

The documentary film,��Sisters of the Wilderness,��starts slowly: close-up of a giraffe���s head, seemingly looking directly at the audience.��The giraffe disappears,��then��reappears, happily munching away, followed��by��a distant shot of the giraffe in its environment. This is followed by a close-up of an elephant walking through the bush. Music swells. Abruptly, music turns to cacophony: protected by razor wire, bulldozers assault and rip up the earth.��A large dump��truck��carries��off whatever��it is the bulldozers are wresting��from beneath the ground.��The noise of dump��trucks��and��a��speeding��train��erupt. Then back to the bush, where there is silence. Finally,��we hear��a person���s voice; a��young woman���s voice��is heard to say, mournfully, between sobs, ���Everything happening to you is a wound.���

Five��young women, seen from the back, embrace each other, watched over by an older woman.��The voice continues, ���My problems are small compared to yours.��� The��young��women burst into tears. The older woman���s voice enters, ���Please don���t lose hope. All your experiences are so painful. Don���t lose hope.�����Thus begins��Sisters of the Wilderness,��a documentary about five young Zulu women, two rangers, and one mentor guide who go on a five-day walk through��the��Imfolozi��wilderness.��This��meditation on sisterhood, wilderness��and the precious��begins, ���Everything happening to you is a wound.���

Hluhluwe���Imfolozi��Park, in KwaZulu-Natal,��is the oldest nature reserve on the African continent.��The park was established in 1895��to protect the white rhinoceros, already��recognized as an endangered species. Thanks to conservation efforts in the park,��iMfolozi��today houses��more than��90% of the white rhinos on the continent. This means the park is a war zone, with rangers and allies on one side, and poachers on the other.

Over the last couple decades,��Hluhluwe-Imfolozi��has also seen the arrival of new��threatening��neighbors, open-cast coal mines. Open-cast��mines are open��pits. Mining corporations dig giant pits, extract the mineral, devastate the surrounding area, work to depletion, and leave. Year in and year out, new mining corporations apply to mine closer and closer to��Hluhluwe-Imfolozi��Park. Last year,��Tendele��Coal Mining applied. This July, it���s a hitherto unknown mining company,��Imvukuzane��Resources.��In each case,��the��nearby��Fuleni��community have��joined��the Park to oppose the mining,��with limited success.��Rhino poachers in the park.��Coal��mines bordering the park. Everything happening to you is a wound.

Sisters of the Wilderness��tells��the story of the double warzone as it focuses on the counter-story of��the wilderness. As the never-named guide mentor��explains, ���The place we went to isn���t like any other place. We were in a powerful place. It���s powerful because of the river. Our aim of bringing people on the trail��is for them to have a release.���

Sisters of the Wilderness��is��the story of a five-day walk. The area covered is thus��relatively��small. The pace of physical movement is slow. But the emotional and learning distances covered are astronomical.��The young women��immediately learn that in the wilderness, they must walk the paths made by the animals.��There must be no heroically ���manmade��� paths in the wilderness because those paths are built of disrespect for the local and indigenous environment. The women learn to respect the environment as they learn to respect one another and themselves. The speed with which these five young women learn to need one another speaks to the forms of isolation, under the rubric of independence, in their everyday lives. They remark on their lessons in sisterhood.

As��they share experiences and visions, they learn to speak and listen to one another, as they learn to speak and listen to themselves. The wilderness teaches the five women to share. The ranger-guides and the mentor-guide make it clear that the wilderness teaches them to share as well. Each day is a new day.��That the wilderness is ���a powerful place��� becomes a lesson in the meaning of Zulu history and identity; the geographies of inclusion and exclusion that go into constructing a ���wilderness zone���; the devastation of mining on local people and��environment, and on the future; the meaning of the wilderness itself.

Although��the film hews closely to its characters, it opens spaces for conversations across the board. This year,��Women���s Month��(August), began with #TotalShutDown��marches and actions across South Africa, and solidarity actions around the world. How do five young Zulu women walking through the wilderness intersect with thousands and tens of thousands of women and non-gender conforming individuals filling the public space��to end gender-based violence? Both actions speak to the importance of release in the context of an analysis and a politics of women���s power and freedom.

In South Africa, as around the world, the wilderness is under attack as it has not been for generations. This is not to say that the wilderness has been revered or left pristine, but rather that right now, thanks to the collusion of local, national��and regional governments,��the assault on the wilderness is more intense and widespread than it has been for decades. This assault is supposedly the price of the so-called��Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Sisters of the Wilderness��argues, quietly and persuasively, that another world is still possible. One of the young women notes that she has learned that even if she has no mother, no parents, she has sisters.��Sisters of the Wilderness��argues��that we would do well to learn that the wilderness itself is, or better can be, our sister. Please don���t lose hope.

August 13, 2018

Eritrea beyond the media fanfare

Image credit Yemane Gebremeskel, Minister of Information of the State of Eritrea via Twitter.

Despite the breathless headlines of the��rapprochement��between��Ethiopia and Eritrea, nothing substantial has come out from Eritrea, as��yet. Eritreans,��who have been endlessly waiting to hear��of��any policy change from their government,��are about to give up.

Since Eritrean officials never cared to give any real information on the agreement between the two countries, the only news is coming from Ethiopian media. Eritreans inside the country have had to��watch��Ethiopian TV channels to stay informed.��The��Eritrean diaspora is ceaselessly refreshing the Twitter handles of Ethiopian officials. The only time Eritrean leaders have communicated about the rapprochement was to inform residents to show up in public places to welcome state guests. While regular��direct flights��between the two countries have resumed, and normalization of inter-state relations progress at a swift pace, Eritreans are still held hostage and reduced to mere observes in their own affairs.

The first Ethiopian flight to Asmara carried many Ethiopian investors who came to explore the Eritrea’s business landscape. Eritreans are denied��this privilege.����Since 2003 import and export businesses have been banned in Eritrea. The subsequent targeting of Eritrean nationals with capital under different pretexts, have resulted in Eritrean investors steadily fleeing the country. The extremely��unfavorable��conditions��for businesses, coupled with��a��construction ban in May 2006, have pushed almost all Eritrean investors to relocate to South Sudan, Angola, Uganda and other��African countries.

No matter if some would like to return, Eritrean investors are not part of the rapprochement. Such uneven engagement will eventually lead to resentment and��a��sense of alienation among Eritreans���a perfect recipe for tense relations between the two��countries in the future.��The opening of borders will certainly benefits Eritreans, however thanks to the Eritrean government���s lack of communication, many are unprepared to even host a few guests, let alone the potential flood of Ethiopians who have been waiting to visit Eritrea for decades.

Most hotels and restaurants do not��have��basic amenities,��such as running water and other modest services, yet��they are about to be packed with Ethiopian visitors.

As many outside observers are overwhelmed by the headlines on global news networks, they are still not able to explore the reality��on��the ground.��The��first Ethiopian Airlines flight��to Eritrea��carried many international and Ethiopian journalists.��With their expectations��low, many were cheerfully sharing their adventures on social media. However, references to Asara’s art-deco architectural style and the country’s welcoming culture have dominated in coverage by��international media over the past few years. We are still waiting��to see��if the journalists��will��come up with deeper stories that delve beneath the cute art-deco surface.

For example, while thousands of followers of Pentecostal churches have been rotting in underground dungeons��since 2002, it has been widely reported, even by the Eritrean opposition media outlets, that 400 prisoners of faith, particularly followers of the banned Pentecostal church have been released��following��the peace deal. This was lauded as��a��sign of��an improving��Eritrean police state. Yet, as later confirmed they were only 35 and their release has��nothing to do��with the recent developments.��In an interview with��BBC Tigrinya, Eritrean��Minister��of��Information��Yemane��Gebremeskel,��even said he was not aware of the release, and��reiterated the old stand that the Eritrean government does not allow religions sponsored by outsiders.

Meanwhile, the information gap for reporting on the ground has been filled��by��rumors; some deliberately driven��by the intelligence agencies and others by self-appointed wishful thinkers.

Rumors have been floating around that there will be a mass release of political prisoners and journalists who have been held in custody��since 2001. It can’t be confirmed.��Other rumors have��created��a��media��uproar, such as the widely spread news that claim��Eritrean troops are��withdrawing from borders. This news was based on a��Facebook page��run by two random individuals who are not affiliated with any official office.��Pressed��to reveal their sources and motives on Twitter, their response was, ���the story was meant to be positive.�����The same Facebook page had also announced��that the most��infamous military prison,��Adi-Abieto,��had��also been closed��due to��the recent developments.

Reuters repeated similar��unconfirmed news claiming that the time period for Eritrean national military service has been returned to its regular 18��months. The news story was based on��information from��family members whose children are in the military and cited��President��Afwerki���s��recent speech in��Sawa. In the speech,��which��I��previously��cited for��its lack of content, the��President did not discuss the subject. When the minister of information was asked to comment he neither denied nor confirmed it.

The consequences of such unverified news have already��reverberated beyond the borders of the Eritrea. Israel is weighing the possibilities of��fouling Eritrean��asylum seekers.

President��Afwerki��has consolidated his unchecked rule by��institutionalizing��fear, and��limiting information. Eritrean top government officials mainly depend on town rumors��for information. As��Haile ���Durue�����Woldensae,��the former minister of foreign affairs��(incarcerated����since��September 2001)��related, even in times of emergency�����ministers did not have any information on what things were going on. So, they were going to anybody that could tell them what is happening, how��are things��going on.���

During all these recent developments, Afwerki��is applying his usual style of information blocking. As some sources have indicated, it��appears that��many ministers��did not have a clue��about the rapprochement until the president made the announcement on June 20th that Eritrea��would��send a delegation to Ethiopia.

Apart from his subordinates, who have been effectively reduced to docility,��the��majority of Eritreans, particularly those living inside the country, are very much aware that��Afwerki��will��only take actions if it secures his own interest. It��has not��taken��long��for the��euphoria of rapprochement to turn��to��anger and frustration. Yet, some hoped that the peace deal might benefit Eritreans by way of securing��Afwerki���s��self-interest.

So what possible changes might we in fact expect in Eritrea? Among the highly expected actions would be��the��re-shuffling��(or�����cleaning”) of��the��top echelons of the government.��Many also expect mass arrests of senior state officials. In exchange,��Afwerki��might release some political prisoners as��a sign of��change.��He��might��go so far as to��use Ethiopian forces to subjugate his own people,��as he did in��2013��when he��used��the��Tigray��People���s Democratic Movement��(TPDM) to conduct��military roundups��and arrests because��Eritreans did not comply��with his orders��to arrest their brothers and sisters. He also may try exert some influence inside of Ethiopia.

All things are possible as long as��Afwerki���s��self-interests are assured.

August 11, 2018

The Rugby revolution is not being televised

Screenshot from the documentary Progress. Image credit Simon Taylor.

More than��20��years after the inception of democracy, South Africa continues to battle with segregation in sport, particularly in rugby. It is astonishing that South African rugby���s inability to transform continues to dominate conversation around the sport���not without damning effects to the game and the country���s image, as we have witnessed during the most recent World Cup and even more recently on TV.���The subject is extremely relevant to the transformation dialogue in South Africa and the role of sport in the broader transformation process.

It is in fact unusual that rugby in South Africa is understood to be a white sport, as contemporary statistics reveal that a great��many��more black people��than white people��play rugby in��the county.��It just happens that most of these players are from the Eastern Cape���the peripheral outpost,��particularly when it comes to national selection of players.

On any given weekend during the cold dry winter in the Eastern Cape, so-called black teams will play it out on dusty township fields���no��TV��coverage and few corporate sponsors,���but a���lot���of passion and���heart put into an old form of rugby far from the new impact-filled sport��that is the common broadcast fare. Yes,��this is�����running rugby.���

Screenshot from the documentary Progress. Image credit Simon Taylor.

Screenshot from the documentary Progress. Image credit Simon Taylor.A���club���called Progress is one of those���teams.��Over the course of several months,��while��shooting a documentary for Periphery Films, I became a���familiar face around Uitenhage,���a small factory town a few��kilometers���off���the N2��arterial highway.��Here,���we���followed the team members of Progress around with cameras���for an entire winter season, to better understand and���to capture what was happening in this isolated, peripheral landscape.

What we���found is an incredible richness of talent and a robust community run rugby��organization. Packed out stadiums every weekend where fans and���players alike support���and play���rugby with��much gusto and shouting. All of this outside of the National Rugby frameworks. No selectors, no��TV���cameras, a total lack of any institutional funding support���and���surprisingly, no sign of���portions of national spend allocated to rugby.

This is heartland rugby. The National Team on TV is not the most important game on the weekend, especially if Progress in blue is to play Gardens in green���Gardens Rugby Club being the local rival.���Zama��Takayi, the coach of Progress, says�����it���s that game!…��if Progress looses to Gardens the whole town is Green… It���s that game!������Progress wing��Riaan,��recalls a 2006 club championship game between Progress and the��Stellenbosch University team, on the latter���s��homeground:�����two things happened in the world��[that]��year… the Tsunami and Progress beating��Maties.���

Screenshot from the documentary Progress. Image credit Simon Taylor.