Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 249

July 31, 2018

The hubris of western science

Aedes Aegypti Mosquito. Image credit Prof. Frank Hadley Collins for the CDC via Public Health Image Library.

Target Malaria��plans��to introduce genetically modified mosquitoes to a remote village in Burkina Faso. Why do we need to be concerned?

Few people need convincing that malaria is a deadly and terrible disease. The World Health Organization��estimates��that half of the world���s population is at risk, with 445,000 deaths recorded in 2016, most of which were in Sub-Saharan Africa. Young children and pregnant women are particularly at risk in areas with high transmission, and, although malaria has been on the global radar for decades, the World Health Organization recently��noted��a ���troubling shift in the trajectory of the disease��� with progress in reducing transmission and fatalities having stalled at the end of 2016.

Prevention and treatment��methods��have��included��insecticide treated mosquito nets,��sprays, and anti-malarial drugs.��Now,��proponents of��a��new technology��claim they��can supposedly eliminate��the disease at its��source,��in the very DNA of��malaria-transmitting��mosquitoes.��It sounds��fictitious, but that is��the objective of��Target Malaria, a research consortium that receives its core funding, $92 million, from the��Bill and Melinda Gates��Foundation��and from��the Open Philanthropy Project, funded largely by��Facebook co-founder Dustin��Moskovitz.

Target Malaria claims that there is a consensus�����that new tools are needed to eliminate malaria.��� Their ���new tool��� is a��gene drive, a speculative technique��intended to engineer the genetics of entire populations of the malaria-transmitting��Anopheles��gambiae��species by a single release of��an organism with engineered genes. Target Malaria aims to create strains of genetically modified female mosquitoes: essential genes for fertility��are cut, preventing them from having female offspring or from having offspring altogether. These modified mosquitoes will be rigged to then pass on their genes to a high percentage of their offspring, supposedly spreading auto-extinction genes throughout the population.

Target Malaria���s project��focuses��on four countries: Burkina Faso, Mali, Uganda and Kenya. The project is most active in Burkina Faso: in 2016,��genetically modified mosquitoes were exported to the country from Imperial College in London��for contained experiments, with approval from the National Biosecurity Agency.��The��Institut��de��Recherche��en Sciences de la Sant�� (IRSS) in Burkina Faso, part of the Target Malaria consortium, plans to release the GM mosquitoes into the environment��between July and November 2018 in one of three villages of��Bana, Pala��ou��Sourkoudiguin. The consortium says it is planning a phased approach; in the first phase, it will release 10,000 ���male-sterile��� (non-gene drive) mosquitoes; in the second, another non-gene drive mosquito will be released into the open, to bias the mosquito population to be male only; in the third and final phase, the gene drive mosquitoes will be released, involving either male bias or female infertility.

Behind gene drive technology

International media coverage of Target Malaria���s project has been substantial, revealing the ubiquitous��technophilia��that characterizes so much of today���s responses to these kinds of new innovations.��Little of this coverage however, has looked at who is behind��research on gene drives or questioned their premise.

The��gene��drive��files, a trove of emails and records discovered by civil society organizations and released in December 2017,��reveal��that��it is in fact��the US Military��that��has taken the lead in pushing forward research on gene drives. According to the records, The��US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has given approximately $100 million for gene drive��and related��research, making it the largest��funder of gene drive research, and it ���either funds or coordinates��with almost all major players working on gene drive development as well as the key holders of patents on CRISPR gene editing technology.�����The files also��uncovered�����an extremely high level of interest and activity by other sections of the US military and intelligence community��� in gene drives.��

It���s not just the US Military that��was subjected to��scrutiny: the gene drive files found that a��gene drive ���advocacy coalition,��� was run by a private PR���firm that received $1.6 million in���funds from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and seem to have used covert���lobbying tactics to influence UN discussion on gene drives.��And while��Target Malaria��has emphasized their independence from��any��military agendas,��it has since become apparent��that��Target Malaria���s Andrea��Crisanti, who developed the modified mosquitoes at Imperial��College��is also funded by��DARPA���s Safe Genes project.

(Un)Intended consequences?

If��the����source��of funding for Target Malaria���s experiments and their relationship to DARPA is not worrying enough, there are��myriad other reasons to be wary of��gene drive technologies,��however well-meaning the target. For one thing, gene drives rely upon the new and poorly understood��gene editing��technique CRISPR-Cas9.��Many of the consequences of such gene editing techniques are yet unknown.

The short sighted hubris of altering wild��insects��populations is also cause for concern. It is a tendency of science and research in the Western world to treat issues in isolation, as if one part has no relationship to larger webs of complex interconnection. Although controlling mosquitoes is supposedly about one strain of a single species, scientists have��warned��that there are dangers in the unintended consequences of altering one part of a complex ecosystem���a decrease in one species for instance often leads to an increase in another or a loss of important functions (such as pollination), or alternatively, a gene drive could spread between species causing potentially devastating effects.��

These are not just hypothetical concerns. In Panama for instance,��following��programs��that targeted��Aedes��agyptae��mosquitoes using fumigation methods and limited releases of GM mosquitoes by UK Biotech��company��Oxitec, there was a��rise��in numbers of the Asian Tiger mosquitoes.

Simple evolution is very likely to outwit too-clever-by-half schemes.��Edward Blumenthal, the Chair of Biological Sciences at Marquette University��has noted that��the��anopheles��mosquito species��may develop��a mutation��(a phenomena known as�����gene��drive resistance�����is already being noted),��preventing the��gene drive��method from working, or��the malaria parasite could find a different host. Researchers have also��warned��that ���a gene drive would be remarkably aggressive,��� likely giving rise to invasive species��and that real world experiments are ���extremely risky.��� And, even when a gene drive is applied in one country, neighboring countries would become part of the experiment, ���whether they like it or not.�����Gene drives and winged insects do not respect national borders.

In addition to impacts on natural ecosystems, there are the very real fears of how gene editing technologies will fare in a world characterized by widening inequalities, violence and warfare in many countries, ecological crises, and a rise in far-right and fascist movements. In today���s social and political climate, being able to genetically engineer undesired species seems just a few steps away from the possibilities of eugenics and certainly opens the way to hostile uses against food sources.��The US President���s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology��warned��the White House directly about the possibility of editing genes and turning viruses or infectious agents into diseases for which no treatment exists.

Burkina Faso as a ‘Guinea Pig’ for experimentation

Within Burkina Faso, a number of groups have been mobilizing in opposition to Target Malaria���s project.��This is not the first time Burkina Faso has experimented with genetic modification: In 2008, when the country���s cotton crop was being devoured by pests, it introduced GM seeds for BT cotton produced by Monsanto (now Bayer). The resulting cotton was pest free but��of lower quality. As the GM cotton lost its premium pricing, the impact was a drop in the value of its output.

On June 2,��2018,��the organization��Collectif��citoyen��pour��l���agro-��cologie, together��with��hundreds of��peasants��and farmers��gathered��in Ouagadougou, holding��banners that said:�����Stop and desist:��GMO, BT��cowpea, genetically modified mosquito,��� and�����Monsanto, Target Malaria and Bill Gates: respect Africa���s right to self-determination.�����These groups want the��risks of GM technologies to be��properly evaluated and a moratorium on gene drives put in place in the meantime.

Leaving aside the��problem of the��unintended consequences��of the released mosquitoes,��there��are��also enormously unequal��power dynamics��at play in��which��a��consortium funded mostly by��powerful foreign��institutions��is��introducing a new technology developed in a lab in the UK to be released in a rural community��in West Africa.��It is not surprising that��the group��COPAGEN,��(Collective pour la protection du��patrimoine��g��netique��Africain),��has��publicly��denounced��Target��Malaria���s use of Burkina Faso for its experiments saying that ���Burkinabes��are being used like guinea pigs��� and has��appealed��to the National Centre for Biosecurity not to authorize the��release of the mosquitoes.

Indeed, although Target Malaria has insisted that it works with local communities and obtains their consent before releasing the mosquitoes,��it is difficult to see how is possible if, as a few people have pointed out, there reportedly��exists��no word for a “gene”��in local languages. Interviews with inhabitants of the targeted villages indicate that their inhabitants��do not really understand��how the gene drives work. Gene drive technology is already very difficult for a general public��to��understand, let alone rural communities who may not have sufficient information about the origins and details of malaria transmission. What in that case constitutes consent? Groups including Third World Network, the African Centre for Biodiversity and ETC Group state that this is a particularly important issue given that Burkina Faso���s biosafety regulation��does not have��specific guidance for conducting risk assessment for GM mosquitoes, and it is unclear what kind of public consultation is required.

Bringing��these concerns to the forefront of��high level negotiations around gene drives��has been challenging for civil society groups. Last month in Montreal, at the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA-22), where government delegates from around the world meet to discuss key issues on biodiversity,��the Target Malaria consortium had a representative,��Elinor��Chemonges, whose role was simultaneously to represent the government of Uganda in a clear conflict of interest.

Target Malaria resembles many of the technical “solutions” that western philanthropists and multinational corporations come up with to solve the social and environmental problems facing our world: from schemes like carbon credits designed to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, to��geoengineering��projects to solve climate change (which Bill Gates has also incidentally invested in), there is no shortage of speculative technical fixes presented to solve��myriad��serious problems that we are faced with today, and which obviate the need to deal with their structural causes.

It is noteworthy that Paraguay, and before that, Sri Lanka,��eliminated��malaria entirely without��western��scientists in lab coats fidgeting with mosquito DNA. The World Health Organization��predicts��that Algeria, Argentina and Uzbekistan could be malaria-free later this year. If such strides are currently being made, imagine what possibilities exist if an equivalent sum to $92 million were spent strengthening public health care systems in West Africa, as well as tracking malaria cases and preventing outbreaks, as was��done��in Paraguay.

If there are any lessons that as Africans we should learn from the past, it���s to be wary of technological interventions that claim to be saving African lives, especially when they are supported and funded by, among others, wealthy western��philanthrocapitalists��and the US Military.

The hubris of western neoliberal capitalism and its attendant belief that we can master and control nature without end is in large part to blame for the current social and ecological crises we are in today. The only way out of these crises, whether it��is climate change or malaria, is to dismantle this very ideology, to create space for indigenous science and knowledge in the path we forge toward the future, and to consider the existing solutions that have been there all along.

July 30, 2018

#BringBackOurHistory

Image credit Michael Fleshman.

Everyone but the��Chibok��girls and their families have moved on. The Obamas are busy building a post-white house legacy that will help the world forget��Barack���s��previous work as��President Drone��and��Deporter��in Chief.��Former Nigerian President��Goodluck��Jonathan, after losing to��Muhammadu��Buhari, is now playing elder statesman���dispensing��advice��on governance.��The celebrities are back to making their music and movies and occasionally lending their faces to other causes.��The intellectuals are back in their classrooms and offices writing their essays behind��paywalls.��And the politicians are thinking about the next election cycle.��The media too has moved on���a��Google��news search of��Chibok��girls from the last 24 hours produces seven hits.

But as��Helon��Habila���s��short and anguished book,��The��Chibok��Girls: The��Boko�� Haram��Kidnappings and Islamist Militancy in Nigeria (2016)��reminds us, history does not march on for the victims.��Certainly��not��for the teens,��now��women,��still in captivity.��Today there are parents still wondering where their children are, knowing that if they are still alive they are enduring horrors at the hands of��Boko��Haram. That is four years of knowing without a doubt that your daughter is living a life of torture.��Imagine living that reality as a parent. Imagine living that reality as one of the��Chibok��girls.

I had just finished reading��Helon���s��book,��so the irony,��quickly turned to abject anger, was not lost on me��when French President Emmanuel told Nigerians that while they should remember their history, they should also leave it behind. CNN��quoted him��on July 5th��as saying ���My generation never experienced colonialism. I mean��it’s��part of our history obviously�����you have to recognize all the past deeds and face them, but you have to move forward.����� If this sounds vaguely familiar it is because��11��years earlier then-French President Nicolas Sarkozy said it more bluntly:�����The tragedy of Africa is that the African has not fully��entered into history�����They have never really launched themselves into the future.����� Put the two statements side by side and the puzzle is complete���history, whether you embrace it or whitewash it, has no business speaking to the present.�� Yes, colonialism was bad, a mistake (as Sarkozy called it in his 2007 Dakar speech), but that was a long a time ago���time��to move on.

It is a lie to equate history with an expired coupon that can no longer be redeemed. In Kenya we declared colonialism over in 1963, but history just shrugged��us off and marched us into neocolonialism.��South Africans celebrated the end of��Apartheid��only to see neo-Apartheid��usher��in a��small black elite that was only too eager to abandon the majority black population. One did not need foresight to know that affirmative action, by design, surely can never work for a majority population.

Slavery ended a long time ago,��Apartheid-like segregation is dead, colonialism is long gone; we��are post racial, post-colonial,��post-apartheid���these��declarations are made while history holds us to the structures that did not change.��So,��here we are today living through��sedimented��historical injustices of slavery,��colonialism��neo-colonialism, globalized inequalities and hoping that somehow free market democracy will undo that history.

African governments are leasing land to foreign powers to come and grow their own food.��The African Union hall was built by the Chinese���African��governments could not marshal the funds themselves.��Macron,��in his Nigeria speech,��revealed that some African cultural events to be held in Paris in 2020 will be sponsored by African governments and businesses.��Why not in Accra or Nairobi then?��Or even more to the point, why not in��Chibok?

It is not just we who are piling democracy on top of historical injustice and inequality���American��democracy,��built on slavery��and its legacies��racist and anti-worker hyper-capitalism,��is a fa��ade unraveling right before our eyes.��Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, after his tour of the United States��noted that����� in��September 2017,��more than one in every eight Americans��was��living in poverty (40 million,��equal to��12.7% of the population). And almost half of those (18.5 million) were living in deep poverty, with reported family income below one-half of the poverty threshold.�����And if��the US does not have its��Chibok��girls, it has its fair share of state violence against black people, a still growing prison-industrial complex, anti-voting measures,�� xenophobia, not to mention being in the words of Martin Luther King��Jr, ���the greatest purveyor of violence in the world.�����And let us not forget Western instigated or supported coups against democratically elected progressive governments all over the global south.��In short American capitalism���America���s��economic, racial and political reality���is incompatible with democracy.

There are many who tried to do just that, to change our societies fundamentally in order to change history, including��Patrice Lumumba, Thomas��Sankara, Ruth First, Chris Hani,��Amilcar��Cabral,��Pio��Gama Pinto, Malcolm X and more recently��Marielle��Franco in Brazil and Berta��C��ceres��in Honduras to name a few. These��men and women of revolutionary visions��were��all assassinated.��Because of them history matters because it guides us, as if on rails.��To change the direction of the train, you have to change the rails it travels on.

Indeed��Boko��Haram,��Habila��reminds us, does not come from a vacuum.��It thrives along the fault lines of a Nigerian neo-colonial state with a leadership that has failed the Nigerian people. For example, Reuters reported��in February 2018��that Africa���s largest oil producer had ���spent $5.8 billion on fuel imports since late 2017.����� It is the coups and counter coups of corrupt and yet-to-be decolonized leaders of the 1960s to the 1990s that made it possible for groups like��Boko��Haram to emerge.��At the same time the Nigerian government,��together with Shell Oil Company,��were busy suppressing the��Ogoni��people who were opposed to living in poverty while their environment was being devastated.��For being a voice of reason, the writer Ken��Saro-Wiwa��was hanged while the rest of the world watched in 1995.

If you want to understand the criminal callousness of leaders like��Goodluck��Jonathan���consider��this response to the��Chibok��kidnappings.��Jonathan��was scheduled to��visit with the families in��Chibok��on May 16, 2014 but citing security concerns, he cancelled the visit.��On that same day he travelled to Paris for a security conference about��Boko��Haram.�� Even if we believe that the Nigerian police and army could not have kept him safe, why��didn���t he use his presidential jet to bring the families to his presidential palace? It cannot get more cynical that this���and��his contempt for the Nigerian poor could not be clearer.��Call it the��Goodluck��syndrome:��when Paris calls all else can go to hell.

The story about the��Chibok��girls is ultimately a story about who we��are as people.��Some of the girls who escaped eventually made their way to the United States where their tragedy became��a recurring trauma to be��exploited��by Christian evangelicals, a shadowy Nigerian Human rights activist and American politicians.��Why did they need to come to the U.S.��at all?�� And once in the U.S., why send them to a Christian school in rural Virginia playing straight into the narrative of Islam is evil and cruel and Christianity is pure and kind? Where was the Nigerian government when these arrangements were being made?�� Where was the African Union?

And where were we?�� Where were we,��the ���relatively conscious��� few that James Baldwin called upon in��The Fire Next Time��with the faint hope they would win the fight for a better world? There are some actions that should spell the end of a government:��Goodluck��Jonathan��and the��Chibok��girls, George Bush and New Orleans (not to mention torture and illegal wars),��Zuma��and�� the��Marikana��massacres, Obama and drone warfare and targeted assassinations, Trump and the separation of asylum-seeking parents from children including infants.��There��are moments when an action, or inaction can no longer hide the lie,��and��on��revealing that lie that government should fall.��Yet��we, the relatively conscious, trudge on sipping on Afro-optimism and democracy as history continues to call our bluff.

���The shocking banality of it all,�����Helon��writes towards the end of the book.��Only one who has seen the horror and wishes for distance can write that sentence to sum up the kidnappings, murders, and attempts at reconstruction in��Chibok.��The tragedy is that��it is also true���how��many millions have died in the Congo since 1998?�� Some say 5.4 million,��others contest that figure��and��say 2 million.��Still others debate whether combat deaths should be counted alongside collateral deaths��due to famine��and��the attrition of war.��But even taking the lowest number should jolt us all into action.��The Israeli state continues to kill,��detain, torture��and maim Palestinians with near impunity. Migrants are dying by the boat loads in the Mediterranean��and African governments stand with the rest of us in shock as if they too could not do something about it. Yemen, Iraq, Afghanistan, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, Philippines��etc.��Indeed,��the banality of it all, the predictability of it all.

But the contradictions are sharpening internationally and nationally in ways that they��never have.����Certainly, the growing inequalities can no longer be sustained with band aid solutions.��No promises of Making America Great Again will work because��the problem is structural, as handed down to us by history.��Most��certainly in countries like Kenya, Nigeria or South Africa the poor will come calling because the history that we wish to banish into the past is very much the present.

There are two fundamental truths that we must face.��History is still here with us��and��the global political leadership as we know it, across gender, race and ethnicity,��has to go.��Baldwin, writing in 1963, was speaking to us��when he said that ���Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise.���

If not, shame on all us for using democracy to sweep history under our collective beds.��Shame on us all.

July 28, 2018

Expropriation without compensation? Ask the British.

Chimanimani 2013. Image credit Ciaran Cross.

One hundred years ago,��it was the British Empire doing all the expropriating.

On 29 July 1918,��the Judicial Committee of the UK���s Privy Council��handed down its infamous ruling,��In Re Southern Rhodesia.��Lord Sumner took the occasion to offer��Britain���s��most expressly and egregiously racist justification for the land dispossession of indigenous peoples. He declared that the ���natives��� could not have had rights to land, because they were ���so low in the scale of social organization that their usages and conceptions of rights and duties are not to be reconciled with the institutions or legal ideas of civilized society.���

The court��upheld��the��expropriation of the entire��territory of Southern Rhodesia for the British Crown,��with the immortal words:�����Whoever owns the land, the natives do not������

Tomorrow, as Zimbabweans go to the polls, they continue to pay the price for that��malediction.

At the turn of the millennium, Zimbabwe underwent the most controversial��and divisive��episode of land redistribution in recent history, with��ZANU PF��sanctioning farm occupations and amending the��law��to permit expropriation without compensation.��The reasons for doing so were both real��and��opportunistic���not necessarily in that order.��Julius��Nyerere, then-President of Tanzania, warned presciently on the eve of Zimbabwe���s independence that it would be untenable ���to tax Zimbabweans in order to compensate people who took [land] away from them through the gun.�������

That���s why Zimbabwe has since 2008 put the onus of compensation for land reform on the British, a clause which was consolidated into the constitution in 2013.��After all, the British��mandated��Cecil Rhodes��� British South Africa Company (BSAC)��to invade and conquer the territory. The British continued to maintain��full oversight of the��continuing land dispossession of the indigenous population by white supremacists from 1889 through to 1965.��After the Privy Council���s 1918 decision, which��rejected��the BSAC���s claim to ownership of the��entire territory of Southern Rhodesia, the British even paid��several million pounds��in compensation�����to the BSAC.

But��now,��Zimbabwe��seems to be heading��in the opposite direction��(at precisely the moment when South Africa looks set to emulate its neighbor���s stance on��compensation). Front-runner for President,��Emmerson��Mnangagwa,��keen to lay the foundations for the country���s re-integration into the international economic order,��has committed to compensate the former landowners.

Only, slapping a��retrospective billion-dollar price tag on former President Robert Mugabe���s��land reform program is not something to celebrate���however much one dislikes��him. It��will not make the past less violent or shambolic, or help restore��a sustainable and equitable��agricultural��sector.

For the incoming government��in Harare,��it could cost. A lot.

Zimbabwe is still seeking to have annulled��two Awards��issued by a tribunal of the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).��The��disputes concern��the government���s expropriation of��timber plantations which were first established by Rhodes��� BSAC.��One might��think��that��the former property��of��the��poster-boy of British imperialism��would be just the ticket for redistribution��in a formerly colonized��state��vying for land reform to complete its path to independence. Right?��Think again.

Indigenous��communities squatting on the plantations are still waiting for formal resettlement, eighteen years after Zimbabwe���s ���fast-track��� land reform kicked off. Some of them��can��remember being forcibly removed from��their��ancestral lands and into native compounds, after the land was taken by the BSAC. The company���s��pine trees��were��planted on the sacred sites and burial grounds of their ancestors, which these communities have maintained over generations, despite having no legal title.

What makes the ICSID��proceedings��so��abhorrent is��not��merely��that the government has��not said one��word in those��communities��� defense. It is��that the arbitrators�����treatment of��the��indigenous communities�����claim��is��as flagrantly racist as that of the Privy Council in 1918.

The communities�����appeal to participate in the case in 2012��was flatly rejected by the��tribunal. Their rights as indigenous peoples under international law to collective ownership and usufruct of their traditional lands, as well as their collective right to consultation, were deemed irrelevant.

And��in��the��final award,��the arbitrators��have��dubbed��these communities ���The��Invaders.���

Meanwhile��they awarded��the Swiss-German investors nearly $200million.��Actually, that���s roughly the present-day equivalent of what the British compensated the BSAC.��But the tribunal��doesn���t want Zimbabwe to pay. Its preferred alternative would be much cheaper. Ideally��the expropriations��should��be reversed and the properties returned to the��investors.��To achieve that��the tribunal called on��both��disputing parties (the state and the company) to��facilitate the invasion��of the indigenous communities��� lands���to burn their crops and homes, and remove them by force if necessary���in the name of white European capital. Again.

July 27, 2018

A Black Queen in the Seattle Reign

Elizabeth Addo in the post-game ���fan zone,��� where she has become a crowd favorite for��selfies��and signatures. Image credit Danny Hoffman.

Elizabeth Addo���s start in club soccer bears little resemblance to youth soccer in the United States. ���In Ghana,�����as��Addo tells the story, ���we don���t have under-17 amateur��[teams]. It���s just the premier side, you just have to join.�����As a��precocious eight-year-old, she showed up for tryouts with��Tesano��Ladies FC, a team in the Greater Accra Women���s League:�����When I got there, they were laughing because I was so tiny and small.��So��the coach��asked me in front of the ladies��if I could play with these big women.��And I said, ���Of course, yes.�����So��they��laughed.��When the game started, then they saw,��like, wow, I���m not just a kid.��They realized I was good.�����The��second-youngest member of��Tesano��at the time��Addo��joined��was nineteen, eleven��years her senior.

Seattle Reign FC���s Elizabeth Addo.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.

Seattle Reign FC���s Elizabeth Addo.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.Addo didn���t��stay��long with��Tesano.��The still tiny midfielder��moved on to play professionally in Nigeria, Serbia, Hungary, and Sweden.��Now��24, she��currently��plays with the Seattle Reign FC in the US National Women���s Soccer League (NWSL)���and��captains the Black Queens,��Ghana���s national team.��Like her male counterparts, Addo has endured years��abroad��to reach the pinnacle of her sport at home.

As France���s victory in Russia fades into memory and the��November 2018��Africa Women Cup of Nations comes into view (along with the 2019 FIFA Women���s World Cup, for which Africa���s participants will be determined at the Cup of Nations), the inequities between women���s and men���s soccer���in Ghana, the United States, and worldwide���will be thrown into high relief. Addo, for one, hopes to see the tournament, hosted in��Ghana,��lead to improvements.�����I pray,��� she says,�����this African Cup will change so many things, so that we [women] also get support.�����If it does, it will be in large part��because players like Addo are��internationalizing the women���s game��everywhere��it is played.

Elizabeth Addo matches up with��Andressinha, the Portland Thorns FC���s Brazilian midfielder.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.

Elizabeth Addo matches up with��Andressinha, the Portland Thorns FC���s Brazilian midfielder.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.Addo���s��circuitous��journey to Reign FC, for example,��belies��the assumptions often made about women���s soccer in the US: that players are privileged suburban kids who move easily from college scholarships to national team glory.��Hope Solo���the former women���s soccer star everyone loves to hate���caused consternation throughout��US soccer��recently��when she said that ���Soccer in America right now is a rich, white kid sport.�����The soccer commentariat��wrung their hands over the bluntness of the accusation, reminded readers that Solo had been arrested for assault, took her comments largely out of context, and��mostly��ignored the fact that Landon Donovan recently made the same argument,��albeit��in less stark terms. Lost in the��media��firestorm was the obvious truth in her statement:��pay-to-play��youth��soccer favors��(relatively)��rich white kids and is a significant problem for player development in US soccer, especially for girls.

The post-match��cool��down following a frustrating Reign FC draw against visiting Orlando Pride.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.

The post-match��cool��down following a frustrating Reign FC draw against visiting Orlando Pride.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.And yet, four days after Solo���s comments, Reign��FC��took the field against the Portland Thorns��in��the fiercest rivalry��in the��NWSL. Joining Addo in the��Starting XI��were��players from seven different nations���even with the team���s popular��Welsh captain��out with an injury. The team included two players named to the Best XI at Euro 2017��(from England and Denmark), a��world-cup winning��Japanese star, two Australians, and a Macedonian��coach,��Vlatko��Andonovski.

The��young��fans at Seattle���s Memorial Stadium may have largely reflected Solo���s critique,��but��they were not watching a��grown-up version of��suburban youth league��soccer.��At��its��highest levels��the game��is increasingly cosmopolitan.��For Addo that means the chance to bring back to Ghana new ideas and strategies that will make the Black Queens viable contenders for France 2019.��For US soccer, it means the chance to celebrate diversity on the pitch��and an alternative vision of what women���s soccer can be.

In her first season with the Seattle Reign, Addo has developed a reputation among fans and the coaching staff as a particularly daring and exciting player.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.

In her first season with the Seattle Reign, Addo has developed a reputation among fans and the coaching staff as a particularly daring and exciting player.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.So��what is Addo���s prognosis for the Black Queens in November? ���I know this year the African Cup is not going to be easy,��� she says, ���but we are going to play hard.��� As her smile grows, she adds, ���And then win.��� She has already won over��at least��one��new fan.�����Before��she came��I didn���t really have a��country that I would root for,��� quipped��Reign FC Coach��Andonovski.�����But now��in the African Cup of Nations, I���m a Ghanaian fan.���

Reign FC���s Welsh captain Jessica��Fishlock, sidelined with an injury, celebrates the team���s 1-0 home victory over rival Portland��with Addo.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.

Reign FC���s Welsh captain Jessica��Fishlock, sidelined with an injury, celebrates the team���s 1-0 home victory over rival Portland��with Addo.��Image credit Danny Hoffman.

July 26, 2018

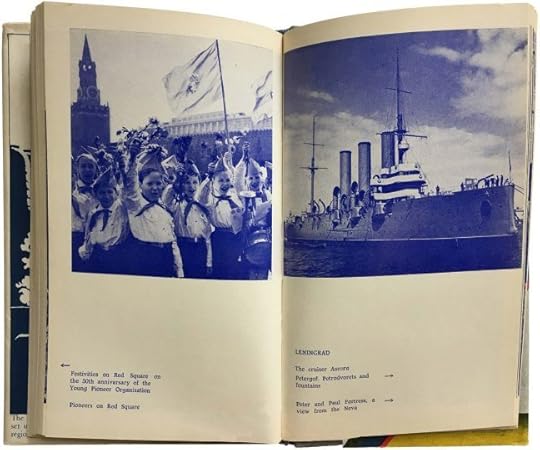

Back in the USSR

Forty years ago in��1978,��Progress Publishers in Moscow released��A Soviet Journey��by the South African writer Alex La��Guma.��Today it stands as��one of��the longest accounts��of the Soviet Union by an African writer. Yet it remains largely ignored, a non-fiction aberration��within his��library of politically committed fiction.��La��Guma��was not��the��only African writer to describe the USSR and its��personal and political��meanings. Andrew Amar��(An African in Moscow, 1960), William Anti-Taylor (Moscow Diary, 1967), and Richard��Dogbeh-David (Voyage ay pays de��L��nine, 1967) published��shorter��accounts that��depicted their experiences studying and traveling in��the Soviet Union. Fellow South African writer Christopher Hope composed��a��memoir of visiting Moscow (Moscow! Moscow!, 1990)��toward the end of the��Cold War,��while the��Jungian�����white bushman,�����Laurens van der Post, published��A Journey into Russia��(1964) at the height of it. Primarily an anti-communist screed,��Van��der Post���s account is technically longer than La��Guma���s, but is nonetheless a questionable source given��the former���s��long-discredited reputation.��Still, why did La��Guma��write��A Soviet Journey, and what does it tell us about South African politics��and the role��of the USSR in the anti-Apartheid��political imagination?

Born��in 1925��and raised in Cape Town, La��Guma��was one of��the��Apartheid��era���s most celebrated��writers. He posthumously received��the Order of��Ikhamanga��in Gold��from the South��African government in 2003, almost two decades after his death��in Havana, Cuba, in 1985.��He is still��best known for his��fiction,��which��captured��the��lives��of��day��laborers, activists, prisoners,��petty criminals,��and impoverished families in Cape Town��in��such works as��A Walk in the Night��(1962),��And a Threefold Cord��(1964),��The Stone Country��(1967), and��In the Fog of the Seasons��� End��(1972).��With Maxim Gorky as his literary hero, La��Guma��crafted a South African version of ���proletarian humanism�����(an��expression��of Gorky���s)��that sought to��represent��the��precarious and��violent world��of working-class life��under��Apartheid. In this regard, he was a member of��a��pivotal��generation of��new��South African writers during the 1950s and 1960s,��exemplified��by��Drum��magazine contributors like��Es���kia��Mphahlele, Can��Themba,��Lewis��Nkosi��and Bloke��Modisane,��who sought to portray��the��vitality of urbanism in��South African life.��La��Guma, Richard Rive��and James Matthews were Cape Town counterparts to this Johannesburg scene.

Against this backdrop,��A Soviet Journey��appears as an anomaly in La��Guma���s��oeuvre��in terms of genre, geography, and subject matter.��However, despite these��contrary qualities, it is also one of his most personal works, with memories of his father, his childhood, and reflections on the wider political world that he belonged to. Beyond his writing��life,��La��Guma��was also a member of��a heralded generation of African National Congress (ANC)��and��South African Communist Party (SACP)��activists��that included such figures as��Nelson Mandela, Walter��Sisulu,��Oliver Tambo, Joe��Slovo��and Ruth First.��A Soviet Journey��unquestionably captures��this political side, while conforming��to��and expanding the widely-recognized��political themes��of��his fiction.

Distinguished as La��Guma���s��longest literary work, fiction or non-fiction,��A Soviet Journey��is a memoir of his travels to the Soviet Union beginning in the late 1960s in his capacity as a representative for the ANC and the SACP.��It is also based on a single trip he took in 1975 upon the invitation of the Soviet Writers Union. In short, it��is a composite work that��fills an important gap in his personal history, given the South African focus of his fiction that does not directly address his time of nearly two decades in exile, primarily in London and Havana. But��A Soviet Journey��is also compelling as a historical and political document of a period when an entire generation of��activists left for exile.��It��points��to the complex politics of the��ANC-SACP alliance��during the Cold War, when the anti-Apartheid��struggle intersected with a broader set of Third World politics that was tri-continental���Africa, Asia, and Latin America���in scope and ambition. La��Guma���s��book provides rare insight into the global political communities that anti-Apartheid��activists were part of, challenging more conventional understandings of this period that have gravitated toward nationalist politics and struggles��internal��to South Africa���the��writings of Mandela,��First, and Steve��Biko��being key examples of this fight on the domestic front.

More specifically,��A Soviet Journey��re-situates the important role that the USSR played for liberation struggles around the world as a patron, host, and political model���perspectives that have gradually been lost, particularly at a popular level, since the demise of the Soviet Union��itself.��Beginning with the 1917��October��Revolution, Leninism provided an alternative model of self-determination apart from��American��Wilsonianism���one that combined nationalism with class politics. This strategic intersection, further articulated through Lenin���s ���Preliminary Draft Theses on the National and Colonial Questions��� (1920), held wide appeal for��black and colonized activists around the��world, resulting in the Black Belt Nation��thesis��and the Native Republic thesis, both of which argued for black liberation in the American South and South Africa, respectively. In both cases, a nationalist struggle would come before a socialist revolution���a two��-stage process and strategy that��broadly��informed the 1927 League Against Imperialism meeting held in Brussels,��which was��sponsored by the��Comintern��under the leadership of Nikolai Bukharin��and��promoted anti-colonial liberation movements around the world. Marxism-Leninism consequently inspired and empowered a spectrum of activist-intellectuals��during this period before the Second World War, including Claude McKay, George��Padmore, Langston Hughes,��and��M. N. Roy,��to name only a few.

It also inspired James (Jimmy) La��Guma, Alex���s father, who attended the League��Against��Imperialism meeting as a representative for the Communist Party of South Africa (founded in 1921) along with Josiah��Gumede��of the ANC. This was��an��early rehearsal��of the��later��affinity and collaboration between both organizations starting in the 1950s. The senior La��Guma��would go on to cultivate a political career of his own, but these sequential political positions��of national liberation followed by socialist revolution��would��continue to shape liberation politics up through the early 1990s and the CODESA process. The argument of ���colonialism of a special type��� developed during the 1950s is the best known iteration of this��political��logic, which pitched South Africa as a colony despite its self-governing status as of 1910. But this position had deeper roots, in addition to experiencing��debate and��revision over time.

This evolving program��also informed��Alex La��Guma���s��writing. His��early fiction��not only captured the oppressiveness of��Apartheid authoritarianism���and, thus, the dimensions of the colonial question in South Africa���but��also��his later work, after he left for in exile in 1966,��examined the fissures, dilemmas, and potential resolutions for the national question. His later novels��In the Fog of the Seasons��� End��(1972) and��Time of the Butcherbird��(1979), which appeared the same decade as��A Soviet Journey, grappled��with this question specific to urban and��rural areas, respectively. But��A Soviet Journey��illustrated an actually existing model of political revolution, decolonization��and self-determination in the eyes of La��Guma. The Soviet system���a��multinational federation of states���had solved the national question��through socialism. Indeed, in contrast to the frequently grim and adverse worlds found in his fiction,��A Soviet Journey��is a joyful work, with La��Guma��celebrating everything about the USSR. For this reason, La��Guma���s��sanguine outlook can be critiqued in retrospect, particularly given knowledge of the Stalinist purges of the 1930s and the Gulag system��more generally��in the decades thereafter. But he was not alone. Figures such as��Padmore, Paul Robeson, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Angela Davis continued to promote the Soviet model as an alternative to the racial capitalist system of the Euro-American West.

Revisiting��A��Soviet Journey��today not only provides for a reconsideration of a neglected text, but also��the restoration of��a personal history, an intellectual history��and a political future that has since been lost.��It expands the definition��and possibilities��of African literature. As��a programmatic statement,��A Soviet Journey��also��opens a broader set of parameters as to how South African politics can be approached, as well as��how��the black��radical tradition, as once formulated by Cedric Robinson and��which has been��centered in the North Atlantic, might be extended to the South Atlantic and across Africa more generally. Anthony��Bogues��has discussed two modes within this tradition���one heretical and another prophetic���that underpin��its��potential for��rupturing the Western Marxist tradition.��Though La��Guma���s��vision of��a��future South Africa was never fulfilled along the lines he imagined,��A Soviet Journey��reflects both of these qualities, exemplifying��a��type of ���epistemic displacement��� (to use an expression of��Bogues���s)��that��points to the��momentary��conjuncture between��the��Black Atlantic,��the��Third World��and South African politics during the Cold War.��La��Guma��and��A Soviet Journey��constitute��a pivot point between all three,��providing a correction to the liberal��triumphalism��that��has often inhabited��post-Cold War��historiographies��of the present. It is a��reminder that national self-determination��remains only a first step.

July 25, 2018

This is Congo

Screenshot from This is Congo.

���To grow up as a child in Congo, according to God���s will, is to grow up in paradise. Perhaps because of the will of man, growing up in Congo is to grow up in misery because of these endless, unjust wars imposed on its people.��� ���Colonel��Mamadou��Ndala

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) recently marked its 58th��independence anniversary���and still awaits the first peaceful transfer of power in its history. It seemed an��opportune time for the release of photographer-turned filmmaker Daniel McCabe���s long-awaited documentary��This��is Congo.

This is Congo��is an ambitious project. In a little more than 90 minutes McCabe uses the narratives and individual fates of a young ambitious military commander, an anonymous whistleblower, a mineral dealer��and a continuously displaced tailor to draw lessons about Congo���s history, its political economy, and its relationship to regional-and international geopolitics. Despite shortcomings and broad-brush generalizations with regards to the depiction of Congo���s complex history, and little reference to Joseph Kabila���s administration,��This��is Congo���s��unique��imagery, and exceptional protagonists leave a lasting impression on its viewers, and unearth important insights about what it means to live in today���s Congo.

Screenshot from This is Congo.

Screenshot from This is Congo.The documentary unfolds in the context of the rebel movement M23���s��2012 invasion��of Goma, the capital city of North Kivu located at the border to Rwanda, and in close proximity to Uganda. Goma is one of the key locations from which to understand recent Congolese history not only due to its role as a formal and informal mineral trade transit hub (highlighted in the documentary by one Mama Romance, who sells precious stones in Rwanda and Kenya to support her family); but also due to its exposure to the geopolitical ambitions of Congo���s neighbors (especially Rwanda); the country���s ethnic diversity and susceptibility to��identitarian��grievances; and the sprawl of international aid-agencies, which have made it Congo���s ���NGO capital.���

Given the continuous formation, and reformation of insurgencies in the region, one could easily be tempted to conclude that in the��Kivus��(and some would say Congo as a whole), history runs in circles. As the whistleblower ���Colonel��Kasongo��� (real name withheld)���acting��as a narrator of sorts���fittingly��comments on the most recent M23 advances: ���Everything that is happening in this war has happened before.���

Screenshot from This is Congo.

Screenshot from This is Congo.Indeed, similarly to previous foreign-backed rebel insurgencies in the eastern DRC, M23 fighters like��their��commander��Sultani��Makenga, participated in previous insurgencies, and were subsequently incorporated into the Congolese Armed Forces (FARDC) as part of controversial peace accords. Without necessarily having a prospect of victory, insurgencies can be motivated by the prospect of using��Kinshasa���s inability to effectively control the territory to force it to the bargaining table to extract more senior positions within the army hierarchy��and the local government.

This dynamic interacts with the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, which has had profound implications for the regional political economy, as well as Congo���s internal politics.��Whereas Rwanda had been intervening in the region directly during the first��and second��Congo Wars, Kigali has always attempted to mask its own geopolitical,��territorial, and resource��ambitions by supporting Congolese insurgents said to represent ���legitimate political grievances.�����As shown repeatedly in��This is Congo, the result of this��not-so-covert��Rwandan backing of insurgencies has led to a dangerous proliferation of anti-Tutsi rhetoric among some Congolese; at one point, protesters��even��claim Kabila must be a Tutsi. This identitarian framing is particularly toxic due to legacies of intra-regional migration, and its implications for the Congolese Tutsi population, who are subsequently wrongly framed as the enemy. Unfortunately, Rwanda���s role in stirring up instability in the DRC has often been neglected by an international community consumed by Rwanda���s remarkable post-genocide economic miracle.

Screenshot from This is Congo.

Screenshot from This is Congo.The most��remarkable��character in the��film is Colonel��Mamadou��Ndala.��Following his promotion to commanding officer in charge of defending the city of��Goma��against M23,��Mamadou, as his supporters refer to him, rose to prominence due to his unwavering patriotism��and exceptional, almost ���Sankarian,�����charisma. McCabe��had��exclusive access to follow��Mamadou��as he��trained��and��prepared��his fellow soldiers, and��accompanied��them��to the frontlines of the battle against M23. The latter���s��love for the country and willingness to sacrifice for the prospect of a better collective future stands��in stark contrast to the DRC���s self-enriching political establishment in Kinshasa.��One particular scene shows FARDC generals from Kinshasa arriving following��a successful battle against M23. Instead of crediting the victory to Colonel��Ndala���s��leadership, and his fellow soldiers, the generals proceed to outdo each other in how much they can ascribe their success to the ���visionary leadership��� of the ���Commandant��Supr��me��� (aka President Kabila).

For Colonel Ndala the main explanation for the country���s continued instability and lack of inclusive statehood is rooted in a history of unaccountable leadership.��Perhaps it is precisely the powerful symbolism of this contrast that he embodies���the��prospect of popular patriotic leadership in service of the people���that would seal his��tragic fate.

This is Congo��will not overwhelm with its complexity, or analytical vigor, but it will encourage viewers to grapple with,��and attempt to interpret,��the insights and fates of its protagonists. As��Mamadou��explains in the opening scenes:�����To grow up as a child in Congo, according to God���s will, is to grow up in paradise,��� but ���perhaps because of the will of man, growing up in Congo is to grow up in misery because of these endless, unjust wars imposed on its people.���

Similarly to��Mamadou, the unwavering commitment of��recently killed��activists��Rossy��Mukendi��and��Luc��Nkulula��to fight for a better future, and realize the country���s immense potential, leave their compatriots with an important message: ���This is Congo���. But it doesn���t have to be.���

July 24, 2018

Thirty years after Cuito Cuanavale

Women and girls with fish traps. Cuito Cuanavale, Angola. 2005. Image credit Cedric Nunn

Cuito��Cuanavale��was the site of a military battle in Angola in 1988, which took place between March and September of that year, and is the largest conventional battle in Africa since the��Second World War. This battle, fought by the the Angolan army FAPLA and the Cubans on one side, and the Angolan rebels UNITA and South Africans SADF on the other, is widely believed to have been lost by UNITA and the��SADF.

Washington gave tacit consent to the��Apartheid South African state to wage this geopolitical battle, and indeed the CIA were aiders and abettors of the creation and arming of UNITA. The Russians in turn supported the fledgling��Angolan socialist state and the Angolan FAPLA military.

Night club. Cuito Cuanavale, Angola 2005

Night club. Cuito Cuanavale, Angola 2005Image credit Cedric Nunn.

During the��Battle of��Cuito��Cuanavale, the Cuban Air Force dominated the skies, outwitting the South African Air Force, and��ensnaring the SADF��armored��division in a cauldron��they were��unable to escape���many of their��armoured��vehicles rusting away in the bush of the��Tumpo��Triangle to this���day.��Following the battle, in which the SADF suffered significant losses,��South Africa���s politicians��realized��that their Generals had over-reached and they relented on South West Africa, paving the way for Namibian independence, the unbanning of South African��liberation organizations��and the release of��political prisoners aligned with the ANC��and other groupings. This led to a political settlement and the dawn of a transition to democracy in 1994.

So, the Battle of��Cuito��Cuanavale��is credited with being the catalyst for��peace, for��bringing about a profound change to the political landscape of the��Southern��African region.

The battle fields of Cuito Cuanavale. Angola. 2005

The battle fields of Cuito Cuanavale. Angola. 2005Image credit Cedric Nunn.

I am interested in the significance of the area of��Cuito��Cuanavale��in this regard and as a signifier for the various processes during the Cold War which beset the entire African continent,��as well as��other��regions around the globe as they were subjected to various abuses and used as proxies by the West in the pursuit of power and scare resources.

The opportunity to visit��Cuito��Cuanavale��came unexpectedly, through journalist and side-kick Andrea��Meeson, who in turn came about the unconventional��uMkhonto��Military Tours operation through her personal involvement in the liberation struggle of South Africa as a combatant in��uMkhonto��weSizwe, armed wing of the African National Congress, whose soldiers fought on the side of the Angolan state.

MPLA soldier. Cuito Cuanavale, Angola 2005

MPLA soldier. Cuito Cuanavale, Angola 2005Image credit Cedric Nunn.

We quickly realized the significance of the opportunity to posit this difficult-to-access battlefield as a key lynchpin in the slew��of engagements that characterized the��armed resistance to Apartheid, colonialism and imperialism.

The first trip, in 2005,��was an eye-opener, traveling “in battle-simulated” conditions meant long rides through the night and flooded plains of Angola, and living in hastily pitched tents at the��best of times. The scenes that met our eyes were of an untouched landscape, heavy with the scars of war, a terrain where time had stood still.

Image credit Cedric Nunn.

Image credit Cedric Nunn.On the second visit to��Cuito��in 2008, and��our��last attempt at accessing the famed��Tumpo��Triangle,��named for��a stream near��Cuito��Carnuavale,��change and progress was beginning to make itself felt, albeit slowly, and traveling with a much larger group brought its own challenges in trying to make sense of the significance geopolitical importance of the battle.

What was clear was that the intensity and ferociousness of the attempt to rid Angola of its Communist aspiration, like��it did in��Mozambique, meant a scorched earth approach that brought the possibility of any flourishing life to a halt. Angola experienced forty years of war in total, and the effects on the people were��tangible, especially in the far-flung regions in which places like��Cuito��are located.

Cuito Cuanavale hospital. Angola 2005. Image credit��Cedric Nunn.

Cuito Cuanavale hospital. Angola 2005. Image credit��Cedric Nunn.Hopefully, these lessons will serve us Africans well, and we will recall what we learnt during the Cold War. We see the rise of AFRICOM and the specter��of Africa once again becoming a theatre as the New Cold War takes shape and the contest for the riches and resources of Africa once again assumes prominence. We are also witnessing what is now clearly an epic struggle of the demise of a unipolar��western��empire, and the emergence of a multi-polar power structure dominated by China and Russia.

July 23, 2018

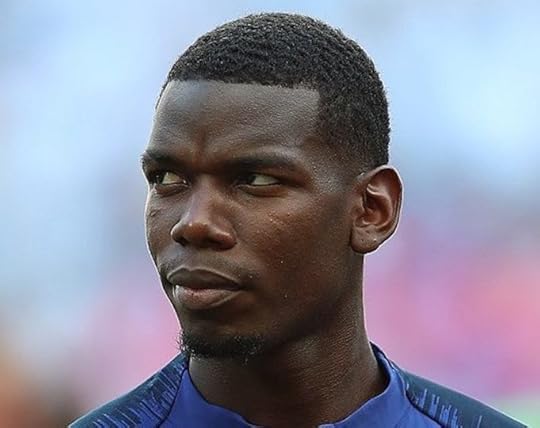

Pogbacit��

French national football team squad member, Paul Pogba with the national team at the 2018 FIFA World Cup. Image credit ���������� ������������ via Wikimedia Commons.

As the clock wound down��on the World Cup final, the roar of the crowds, in the bar I was in and on the surrounding packed street in the Paris neighborhood of Butte aux��Cailles, grew louder and louder. Someone lit a red flare, and the crowd started swirling around him. The power of the moment came from knowing we were a tiny piece of a mass communion that stretched all over Paris, all over France, all over the world���all shouting and singing and not quite believing what was happening before our eyes. A drummer sat down at the crossroads and a crowd formed around him, bouncing, moving, uncontrollable. The dancing would continue for hours, to the pulse of a giant speaker set down in the middle of the street. A��man stood on a parked van waving a giant French flag over the crowd.

The victory felt all the more powerful because of who its authors were. Over the course of the semi-final and final, the most beautiful and crucial goals of France���s tournament were scored by Samuel��Umtiti,��Kylian��Mbapp����and Paul��Pogba. All three are of African background, like the majority of the team, and all three grew up in what are known as��banlieues��(suburbs) in France. These are the neighborhoods dotted with housing projects on the outskirts of the capital where many poorer immigrant communities are concentrated. Like the generation of players from 1998, who this year’s champions have now joined in the pantheon of French soccer,��Pogba��and his teammates are a powerful riposte to far-right politicians who see immigration as a threat to France. In fact, they seem to have basically silenced any such critiques, for this tournament saw few of the racist criticisms of the team��that��marked recent World Cups. Victory is a powerful thing, and for the moment at least, Pogba��and his teammates have become the country���s new joyous heroes.

Media pundits in the UK, particularly Graham��Souness, have targeted��Pogba��with criticisms similar to those that are directed at��Raheem��Sterling and other black��players in the Premier League. They claimed he was overpaid, too much of a flashy player needing correction and management.��Pogba���s��World Cup performance has been a powerful riposte to these attacks as well.

Over the course of the tournament Pogba��became the moral center of the team. Before the final, he gave��a speech��in the locker room telling his teammates that they were about to play a game that could ���change history… Tonight, I want us to be remembered by all the French people who are watching, by their children, their grandchildren, and their great grandchildren too.���

The kind of love a player like��Pogba��has now garnered from the public is��something that politicians hunger for but can never quite get, because none of them can ever create��as much collective joy as a soccer team does. You could see that palpably as the French president Emmanuel Macron, having made his way to the locker room, dutifully learned how to dab from��Pogba, and stood amongst the players, hoping some of that glory would rub off of him. Welcomed to the presidential palace on Monday, the players selected��Pogba��to give a speech on their behalf. He was completely at ease in his suit, wearing sunglasses, joking and animating the crowd, singing and joking about his teammates. Macron stood off to the side.

The team���s victory represents the culmination, and confirmation, of a long-term project in the country that leveraged civic support for youth soccer as a social program, while creating a centralized system to train players for the international stage. As Rory Smith and��Elien��Peltier��have written, figures like Antonio��Riccardi,��Mbapp�����s��first coach in the��banlieue��of��Bondy, combine roles as social workers and athletic mentors. Municipal funds support the building and maintenance of soccer fields, but also the salaries of local coaches. Soccer gives young boys and girls something to do amidst the towering blocks of apartments, and is seen���as��soccer has been from its origins in the English schools of the��19th��century���as a way of inculcating values of team-work and fair-play among kids.

This web of municipal infrastructure and coaching has created one of the most successful zones of youth soccer development in the world. Young players are raised in an environment surrounded by great players, and the results are striking. As��a��Darko��Dukic��paper has shown, there were��52��players with French citizenship at the World Cup this year���the��23��on the French team, along with others with double-nationality playing for Tunisia, Morocco, Portugal, and Senegal. Senegal had eight players who grew up in France, most of whom played on French national teams at the youth level. This is made possible by current FIFA regulations,��which allow players with multiple nationalities to switch which country they play for once they turn��21. Of all the cities in the world, Paris sent the most players to the tournament.

The local municipal infrastructure in many French regions is connected to a centralized national project for youth development, centered on the��Clairefontaine��Academy, founded in 1988. In the promotional video that the French Football Federation released at the beginning of the tournament��(which ended up aging well comparatively)��you see the players, including��Pogba, along with��Deschamps, at this training academy.��Pogba��has been a central part of France���s youth teams for years, and is very much a product of this centralized system.

If infrastructure is the foundation for any victory, of course, it is never enough without the brilliance of individual players at a particular moment in history. And for��Pogba��and many of his teammates,��as for many fans across the country,��this victory also felt like a vindication. In a powerful��meditation��on the contradictions at work in rooting for France from the continent of Africa, fully aware that the presence of players like��Pogba��is the result of histories of colonialism, the historian��Achille��Mbembe��notes that, in the midst of all else around us, the victory at least��allowed us to ���breathe, for the space of an instant, and to remind ourselves of that that we too can, alongside others, win,��� an idea, a possibility, that is ���priceless.���

We might give a name to that sense of opening and hope: Pogbacit��.��It is a combination of the solidity and serenity with which he played, the humor and joy with which he celebrated, and the intensity and fierceness with which he spoke to his teammates. It is how he responded after the final to those who had criticized him over the years, claiming he lacked the ���discipline��� or ���seriousness��� to become a great player. He��slapped his jersey on the place��where there was just star, representing France���s sole World Cup victory���and��now thanks to him there will be two. Then, nodding his head, he gestured ���you���ve been talking.��� Then, pointing to his ear, ���I���m not listening anymore.���

Finally, he pointed at the pitch beneath him, and then bent down to touch it. The facts are on the ground, the history made, and it can never be taken away.

July 18, 2018

In Langa with Louis Moholo-Moholo

Louis Moholo Moholo in Langa. Image credit Ben Verghese.

���We love you, we love you, you don’t have to love us, we love you…��� drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo enthused during a series of concerts at Guga S���thebe Arts Centre in Langa (Cape Town) earlier in 2018.

The series, titled SONKE���Uplift the People���came in three-parts: each an outdoor concert at the Guga S���thebe amphitheater. A mark of respect for a musician who during his decades overseas helped first collaboratively establish the Blue Notes as ���a school��� then become a pivotal figure in the free jazz movement. SONKE (meaning together) sought to allow Louis (aka Bra Tebs, or Bra Louis, or Ntate Louis or Mr Moholo-Moholo depending on your positionality) the room to shine on his home turf while also allowing Langa locals to hear and celebrate a home-grown icon in action. Now, more than ten years since he returned from exile (���It���s a motherfucker,��� he memorably said) and pushing 80 years of age, Bra Louis remains hyper-charged and hungry to play; that is, when musicians and concert organizers have the stamina to work with him.

In the last 12 months, including the SONKE shows, Louis has performed half a dozen times at Guga S���thebe. Recently, Moholo-Moholo performed here as part of Sipholeni Sonke, a concert and film project from students of Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT). Also featuring students and mentors from the Winston Mankunku Ngozi Jazz Foundation (based in Gugulethu), Sipholeni Sonke (we heal/chill together) aims to portray a narrative of the ongoing cultural work(ers) using music as a uniting force within communities in Langa and Gugulethu. The student film-makers from CPUT are fundraising for their venture��until��July 19th.

In early June, Moholo-Moholo was acknowledged in concert and conversation by The Centre for Humanities Research at the University of the Western Cape. The focus from UWC picked up and extends an academic interest tweaked in 2016 by the Louis Moholo-Moholo Legacy Project, an eclectic program arranged by the Centre for African Studies at University of Cape Town. For all the merits and importance of these initiatives, it remains to be seen how the legacies of Louis Moholo-Moholo and the Blue Notes will enter the curriculum and be taught or acknowledged on an ongoing basis.

The SONKE concerts were without an institutional agenda. Running three consecutive weekends through late January into February, Bra Louis was given space to be celebrated and enjoy himself for more than just a one-off gig.

���KwaLanga kumnandi…��� goes the song. ���In Langa it���s nice.��� And yes, the lokshin closest to Cape Town���s leafy (and still mostly white) suburbs and city center possesses a certain appealing energy. It feels different to denser, more populated areas of the Cape Flats. It���s a feeling hard to put into words, or perhaps just into English. And so, as the song goes: ���KwaLanga kumnandi…���

Regarded as the second oldest township countrywide, in Langa the cultural history runs deep. But what of the study, the books or theses published on this? Where is this knowledge shared?

With much of Langa’s musical history still unwritten and/or disseminated into public consciousness, stories mostly remain in conversation(s) with elders, including Louis, or Mpumi Moholo (his wife), Pallo Jordan, or other less high-profile age mates. Once such tale is of Sigcawu Street, where, in the 1950s, so the story goes, in that street alone there were 80 or more gifted musicians active; Louis Moholo was one (then drumming with The Chordettes) another was Christopher ���Colombus��� Ngcukana (father to Duke, Ezra and Fitzroy).

Perhaps it���s an overly nostalgic view but then, a spirit, the spirit of togetherness, seemed lit. And now? Where is such spirited togetherness, the jam sessions, the hub/clubs, where is the jazz in Langa now?

At the first and third of the SONKE concerts Louis sat with a small band of musicians chosen from his generation-crossing contact book. On keys, Mr Mervyn Africa, a comrade from time together in London. Fellow Langa resident Fancy Galada sang. Bassist Brydon Bolton continued as one of Louis��� regular Cape Town collaborators. Then for the frontline, two shows featured saxophonist Abraham Mennon, with reinforcement coming in the third concert from Langa-born elder Duke Norman (tenor sax) and trumpeter Mandisi Dyantyis.

Each of those shows offered its own magic and memories. In the first gig (taking place the week Bra Hugh passed), Fancy Galada pushed her voice through extended, marauding versions of ���Dikeledi,��� ���The Tag��� and ���Yakhal���inkomo.��� Blowing adeptly, Abraham Mennon managed to tenderly express much-loved melodies while also finding room to let loose, at times removing the mouth piece of his horn to generate all manner of squeaks and shrieks. And then, in the third concert not only did Mandisi Dyantyis��� playing bring additional warmth and extra dimension to the ensemble but Louis��� own understated crooning vocals repeatedly came to the fore: ���Yes baby. No baby. Yes baby!���

The second SONKE concert offered a duet format akin to that which Louis has explored through the years with Cecil Taylor, Irene Schweizer, Keith Tippett and scores of piano players. A baby grand piano was wheeled onto the stage and Hilton Schilder, the chosen pianist, invited to express himself opposite Louis.

Moving in and out of intense improvised exchanges, glimpses of recognisable melodies fleetingly revealed themselves (including Schilder���s composition ���Birsigstrasse 90��� and John Coltrane���s ���Naima���). Throughout both sets the two colourful artists shone; Hilton in a grey cape wagging its tail in the gusting wind, Louis working his kit wearing a signature porkpie hat. Following the interval, looking all the more epic after sunset, Hilton prepared the piano with the chain worn around his neck placed under the bonnet. Thereafter (until its removal) notes rushed in a sharper key, an act of experimentation illustrating the type of creative thought and bravery Moholo-Moholo still relishes from musicians he takes the stage with. Tuning into each other, channelling circles and cycles of sounds, under a starry sky the wind blew and these two hip kings played.

���Working with Louis Moholo I find I do a lot of things I wouldn’t get into with anybody else.��� The pianist Stan Tracey told Melody Maker in 1973. Forty-five years later, in the liner notes for Moholo-Moholo���s latest album release Uplift the People (Ogun Records, 2018), bandmates Alexander Hawkins, Jason Yarde, John Edwards and Shabaka Hutchings similarly express their appreciation for how Bra Louis musically provokes them.

Gigs in London (the Moholo���s home away from home for half a century) still come Louis’ way. He���s due back there in October for an improv festival. Up in that metropole, the force Moholo and fellow Blue Notes [study guide here: with Johnny Dyani] brought with them, shaking the scene on their arrival in the mid-1960s continues to affect generations of musicians.

Back in the early 1970s, Louis briefly returned to South Africa, then under Apartheid’s heavy manners. Moments of his visits to Langa were documented, in part with an audio recording by Ian Bruce Huntley from Langa Town Hall. There Moholo played alongside a group of musicians including Winston Mankunku Ngozi and a young Ezra Ngcukana. Listening back to that concert, a thunderous Brotherhood of Breath-like storm stacked with a dozen or so musicians laying down lines and loops of melodies on top of or within each other���s playing, it makes me wonder if such intensity is carried by ensembles playing in the Cape, or elsewhere in South Africa today.

Photos by Basil Breakey also allow us to look at Moholo���s 1972 trip home. Two shots in particular are striking. In Langa Stadium, Louis Moholo is at the drums surrounded by a standing crowd, looking on. Shoulders high, biceps bulging, he wears a waistcoat over a vest adorned with a star. Mouth open and eyes wide he is staring at whoever the musicians with him at this moment are. Above all the figures is a clear sky, grey in one image, white in the other, blown out in Breakey���s image. Those two photos were partial inspiration for the SONKE concerts. Visions of the music (back) in Langa. Back outside. In the open air, where the music, the vibrations may travel up and outwards, in and across the township. Sounds that cannot be contained. Sounds that are free. Free(d) jazz.

A few weeks after the SONKE shows, Louis Moholo-Moholo performed as a headline act at the 2018 Cape Town International Jazz Festival, a gala the promoters annually subtitle ���Africa���s Greatest Gathering��� and colloquially referred to as The Jazz. Year on year conversations locally bemoan how the festival overemphasizes styles of music/musicians unrecognizable as being jazz artists, be it jazz as a history, a mode or method of music making. That history, and feelings���these�� ways of playing and performing (on the edge, in the present)���have been embodied by Moholo-Moholo for almost all his life. To play under an open sky in his home, Langa, feels right, it felt right. And as he often says in his still hip way: right on.

But, truth is, to put on shows like SONKE takes a lot. Crews have to come together and organize such occasions, money is tight, people are busy, infrastructure seems to be built elsewhere. Without government support forthcoming it takes individuals, collectives, friends helping each other to get things happening. So what else to do but keep on? Do we not owe it to the elders around us? Right on…

When the sun sets, alakutshon���ilanga, will we have listened (and learnt) all that the elders around us had to share? Asimameleni sonke. Let us listen together. Sibeni sonke. Sisonke.

July 15, 2018

The Story of Kenyan photographer Priya Ramrakha

Two women, Kenya, 1966. By Priya Ramrakha.

After Kenyan photojournalist Priya Ramrakha was killed on assignment in Biafra, Nigeria, in 1968, his photographic legacy and archive seemed to vanish. Four decades later, his relative, Shravan Vidyarthi, found his prints and negatives in Nairobi. Covered in dust and all but forgotten, the 100,000 images that make up his archive trace the short life of one of the most prolific photographers of Africa���s independence movements in the 1950s and 1960s.

In 2004, Shravan started to retrace Priya Ramrakha���s life story, talking to journalists, family and friends and using a handful of images in family collections that would become the basis for his documentary film, African Lens: The Story of Priya Ramrakha (2007). After the film screened, Shravan recovered thousands more prints, negatives and albums from Priya���s family and friends across Kenya, the US and Europe. Numbering over 100,000 negatives, prints, contact sheets and documents, a selection of these photos were exhibited for the first time last October in Johannesburg (Priya Ramrakha | A Pan-African Perspective 1955-1968, commissioned with VIAD at the University of Johannesburg).

Bicycles on bridge, c.1965, west Africa

Bicycles on bridge, c.1965, west AfricaEven though Priya left no written records as to his views of what photographs could do, the influences of his journalist family���s anti-colonial efforts shaped his career. Daily, Priya saw the impact of the color bar, its segregations and deprivations endured by African and Indian Kenyans in the colony. In the 1940s and 1950s, the efforts of African and Indian freedom fighters, activists, leaders, and everyday people joining forces is a story of cooperation that is rarely mentioned or recalled in Kenya now.

In 1952 Priya was only 18 when he turned to photographing the first skirmishes of Mau Mau in Kenya. He documented horrific scenes after the Lari massacre, and later recorded the round-ups and jailing of innocent people in Nairobi. Later that year the government shut down the free press in Kenya, his photos with very different editorial guises appeared in the pro-British press, the free press, and the east African edition of Drum.

Nuns, Nigeria, 1968

Nuns, Nigeria, 1968In 1960 Priya studied in Los Angeles, and in a few short years captured key moments of black struggle in the US, rallies for Martin Luther King Jr, and Malcolm X and Nation of Islam marches in Los Angeles and New York. He portrayed the pan-Africanist Miriam Makeba, who performed to raise funds for the young generation of African students studying in the US. Priya was drawn to a series of subjects and everyday moments that were significant for offering a different gravity and center, though these never aligned with editorial demand in the US or internationally.

Miriam Makeba, 1962.

Miriam Makeba, 1962.Though Priya���s images marked resonances between the civil-rights movements in the US and anti-colonial struggles and independence movements on the continent, he became known for his work covering the front lines as a first African photographer to work for Time and Life. With a British passport from colonial Kenya in hand, he crossed borders that were forbidden to many of his contemporaries, and he photographed independence movements and wars in Kenya, Zanzibar, Congo, Yemen, and Nigeria. He was killed in the crossfire of the Biafran/Nigerian war in 1968, aged 33.

Priya���s archive is not solely photojournalistic, but offers todays viewers an expansive array of glimpses of everyday people. To think of his work as singularly political or journalistic is to overlook the way he connected with people, with an abiding curiosity that framed bicyclists on the streets, a father cradling his baby, or friends chatting in the shadows, oblivious to his camera.

See Ramrakha���s work at the Recontres d���Arles in July 2018, Photoville mid-September 2018, South African National Gallery/IZIKO in February 2019.

Priya Ramrakha, edited by Shravan Vidyarthi and Erin Haney, with essays by Morley Safer, John Edwin Mason, Sana Aiyar, Drew Thompson, Shravan Vidyarthi, Erin Haney and Paul Theroux. Kehrer Verlag, October 2018. Advance copies/trailer/additional information here.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers