Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 246

August 30, 2018

Eddison Zvobgo and the struggle for Zimbabwe

Eddison Zvobgo.

We do not want to create a socio-legal order in the country in which people are petrified, in which people go to bed having barricaded their doors and their windows because someone belonging to the��Special��Branch of the police will break into their houses. This is what we have been fighting against.

�����Eddison��Zvobgo

On August 22, my family, strewn across the globe, remembered the��life of��Eddison��Zvobgo���my uncle, our family patriarch, and one of Zimbabwe���s great men���whose��life��ended��in 2004��after��an arduous battle��with��cancer.��With��Zimbabweans��once again facing an uncertain future,��I have been reflecting��on��his��life and involvement in the struggle for Zimbabwe, and wondering what he,��and��others��who sacrificed so much for the nation,��would make of��contemporary politics.

A��Harvard-trained lawyer, poet, and the ZANU-PF spokesperson at the Lancaster House where the eponymous��Agreement��brought recognized independence to��Zimbabwe,��Eddison��loved his country��and served��it��throughout his life, even at great��personal cost.

Like anyone,��Eddison��was a flawed and complicated man.��Before becoming a��critical voice��against��former president��Robert Mugabe���who for��decades��took all means necessary to maintain his grip on power���Eddison��had not only been Mugabe���s co-partisan but also his ally.��They had fought together in the liberation struggle��and, along with many others,��emerged as heroes.

A��brilliant legal mind,��Eddison��helped��legislate the��single-party state��Mugabe governed���a��reality that even those who loved him cannot ignore or forget.��However, as��Mugabe��defied��the law, term limits, and��civil liberties,��Eddison��began to��publicly challenge��him.��One notable��challenge��was over��Gukurahundi���the massacres in which an estimated 20,000��Ndebele people��were��killed.��Eddison��was��one of the very few ZANU��leaders to��ever��recognize and apologize��for��Gukurahundi��notwithstanding the political taboo.��These defections from mainstream ZANU politics��cost him dearly.

One of my earliest memories of Eddison is in the hospital when I was 4 years old. He had just survived an assassination attempt staged as a car accident���the price of��stepping out of line. I do not remember much of the events succeeding the��incident, except for the whoosh of hospital curtains being drawn by white-clad nurses, the blue blanket that covered my uncle���s two leg casts, and laughter���my family���s coping mechanism of choice. From time to time in the following years, at family gatherings, I would overhear relatives talking in hushed tones about the accident. They would clam up when they realized I was listening.��Ever-curious, I would press, ���What are you talking about?��� to which they would respond, with a smile, ���Oh Clara [my middle name], you ask too many questions. Some things you are just not meant to know…���

Once Minister of Justice and, later, Minister of��Parliamentary��and��Constitutional Affairs,��Eddison��was��demoted��over the years, first��to Minister of Mines��then��to Minister Without Portfolio.��Finally,��in 2000,��Mugabe��removed��him��from the cabinet��altogether.��At a different time, under different circumstances,��Eddison��may have been president of Zimbabwe. But, I suppose we will never know.

I wonder sometimes if it is better that my uncle did not��live to��see the extent of Zimbabwe���s fall and the worst of corruption, kleptocracy, and repression under Mugabe and now Mnangagwa. I think it��may��have been too��painful��to see��his��and others�����dreams��for��Zimbabwe in tatters.��While in Mozambique during the liberation struggle,��he��is��recorded��in an interview��saying:

Every one of us has been in jail ten years, fourteen years, I myself nine, without trial. Every one of us has lived, has had to live, scared of the police. How on earth could we create a society which is exactly like that? We don���t want it. We are fed up of it. And, this is why we are in this revolution for as long as is necessary, to abolish this system.

Forty years later,��Eddison���s��question resounds still.��How on earth could we create a society which is exactly like that?��Zimbabweans��today��live��in��fear of��harassment, intimidation, and political violence��by the��police and the military.��And,��they��don���t want it.��They��are fed up of it.��So, I wonder:��Will the revolution begin anew, this time to��dismantle��the party��Eddison��helped found��and��remove its��leaders��from power?

My uncle��Eddison���or��babamukuru, as I called him���made an indelible mark on my life, and I wish he could see me today. Now pursuing a political science PhD, I, like him, pry into the uncomfortable and criticize the party and the regime, albeit from a safer distance.��He��was a poet,��politician,��and patriot. But, to me, he was first and foremost my uncle, my dad���s big brother. He��remains��the smartest and funniest person I have ever known.��He taught��me to be sharp, competitive, and, above all, courageous.��How��I loved him.

Chengetai JM Zvogbo’s biography,��The Struggle for Zimbabwe 1935-2004: Eddison JM Zvobgo is recently available from Mambo Press (Gweru, Zimbabwe).

August 29, 2018

The Black Mediterranean and the limits of liberal solidarity

Still from When Paul Came Over the Sea.

The Mediterranean has become a graveyard where black and brown bodies transit��a��hostile and��deadly passage. While the rise of the far right in Europe and��border externalization have resulted in a drastic drop of the number of refugees and migrants crossing the sea,��more than 1,500 people have died so far in 2018 trying to reach Europe;��making it one of the deadliest years. Far right policies, dead ideologies, and cultural wars��also��fundamentally altered��Europeans��� view on issues of forced displacement, resettlement��and solidarity.

When Paul came over the Sea��is a now-celebrated documentary��that��highlights��these��issues through the��encounter��between��two men:��Jakob��Preuss,��a��German filmmaker,��former reporter and political advisor to the Green Party,��and��Paul��Nkamani��a��Cameroonian migrant and��political activist,��whose��work against��the autocratic government��in his home country��resulted��in him being expelled from university and abandoning his dream of being a diplomat.

Preuss��lays out what��is��at��stake��from the perspectives��of��both the migrant and the European. The documentary��opens��in an informal settlement��on��the outskirt of Melilla, a Spanish exclave located on the Moroccan side of the Mediterranean, where Paul and other Cameroonian migrants live while waiting for an opportunity to reach��Europe. The��candid conversations��between��Preuss��and��camp residents��and��Nkamani���s��story��of his��journey from��Douala��through Nigeria, Mali��and Algeria,��offer an important summary of the conditions and motives behind forced displacement of African migrants.

The major tension in��the film��revolves��around��Jakob���s��decision whether to become an active part of Paul���s pursuit of a better life,��or��to��remain a detached filmmaker. This��suggests the limits of solidarity at work in the project. The documentary���s epigraph further motivates this observation: A quote��by Frederik Douglas on��migration as a fundamental and undeniable human right, and another��by Paul Collier,��from his book��Exodus: How migration is changing our world,��in which��he��rehearses an argument��that refugees are drawn by Europe���s generous welfare systems. Throughout the film,��Preuss��is on the fence��between the two.

While other documentaries on the refugee crisis,��such as Ai Weiwei���s��Human Flow,��avoided analysis,��When Paul came over the Sea��attempts to be too informative;��there is��overemphasis on actors and policies��such that the��voices of both protagonists are relegated to the background.��Preuss��focuses on feeding the curiosity and interests of a European/German spectator who wants to find in his documentary available answers to a hotly discussed topic and draw easy conclusions on the refugee issue.

Throughout the documentary,��Preuss��� political activism feeds��his ethical approach to the question of the Black Mediterranean: How should the European subject react to the refugee��issue?��The��central ethnographic narrative attempts to uncover the many sides of the Mediterranean issue��beginning��with��Nkamani���s��reasons to migrate,��to his struggle to settle in Germany. In contrast to Gianfranco Rosi���s��Fire at Sea, Preuss�����investigative preoccupation and analytical aesthetics��spares��viewers the widely circulated��and��grim images of drowned bodies. The deadly passage is��narrated��instead��through��Nkamani���s��memories and language. Still, the filmmaker organizes and manages��the��visual narrative of his social and political relationship with��Nkamani��in the service of particular identity politics that always produces the other as a subject in need of rescue.��Again, the��white male hero��is��faced with an incomparable challenge to his political potency.��Preuss���s��anxiety mirrors��Germany���s political and cultural responses to the refugee issue��at the national level.

Counter to this driving interest,��Nkamani��emerges as��a��larger-than-life figure whose refined personality, superb emotional intelligence��and strong communication skills allow him to navigate complex and hostile spaces that cut across gender, race��and class. In a revealing moment, we see��him, after surviving the crossing to Spain in which half of his companions drowned, chatting��over the internet��with��someone��who remained in the Moroccan camp. The camera��zooms��on Paul writing��news of his last moments with one of his friends; he then decides to delete what he has written and��replace��it��with a more delicate and compassionate statement.

While the meeting between��Preuss��and��Nkamani��is framed as accidental, it becomes clear, as the film develops, that their encounter wouldn���t be possible if it weren���t for their intellectual, political, and professional affinities. Moments after��Nkamani��is introduced,��Preuss��narrates:�����I will never be sure if I chose him or if he chose me��� in any case this is the story of our encounter.���

Their relationship cannot however be framed as a friendship. Rather, it uncovers the limits of solidarity at work in the documentary.��From��the start, their meeting is motivated by��pragmatic, mutual��interest.��In��Nkamani,��Preuss��finds an��interlocutor who allows him to have a clear and balanced discussion. Such a meaningful exchange is what fulfills the filmmaker���s desire to investigate the dynamics of the refugee experience.��Nkamani��is��a complex character,��who appropriates and stages different and conflicting discourses to negotiate and��ensure��his safety. During his stay at the Red Cross shelter and quite aware of the guiding sympathies of European refugee policies, he asks the Red Cross instructor about ���how can one prove his homosexuality?��� in order to ask for political asylum.��The��Senegalese instructor tells him�����you need to have a good story to tell.�����Nakamani��further questions, ���To prove that you are homosexual do they ask you to do it?��� These questions suggest that he is capable of��mobilizing��a rhetoric��of false victimhood to secure the sought-after refugee status. In a��video��released��a��few months after the documentary, we see��Nkamani��giving his ���message back home��� in which he urges anyone thinking of migrating to Europe ���to do it the legal way.��� This is a stark departure from what he��states��at the beginning of the film, that��sub-Saharan migrants and refugees are ���nothing but a burden��� that���s why [they] have to leave��� [and join] those who were lucky with jobs��� in Europe.

The documentary���s emphasis on the personal and the ethical��manages to��introduce��often��overlooked dimensions of the Mediterranean passage,��such as religion, masculinity, interracial��communication��and dreams. In an almost lyrical scene,��Preuss��and��Nkamani��reflect on their dreams:��Preuss��recalls a nightmare��in which��he leaves��Nkamani��behind in a metro station, and fears of his arrest, while��Nkamani��recounts��dreaming of��filth, rubbish and waste and explains that ���at home, you always interpret dreams of the opposite way.���

When Paul came over the Sea��oscillates between��the rational and uncanny, between the ethical and the subjective to offer an important documentary.��Despite its forced��narrative and��overly��ambitious��intentions, it is a��hopeful examination of the complex relationship between Europeans and African migrants��and a��must-see for those interested in the Mediterranean migration issue.

August 28, 2018

The contemporary state of Ethiopia

Image of Addis Ababa street by Andrea Moroni (Flickr CC)

The youth protest movement that emerged in Ethiopia in 2016, forged a fundamental shift in power relations by 2018. Tech savvy youngsters in Ethiopia challenged prevailing social media theories by employing communication technologies for the mobilization of collective action.

It was against the severely repressive political regime of the Ethiopian Peoples��� Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) (1991-present) that forms of clandestinely held protests began to emerge. Particularly pronounced in the region of��Oromiya, its��magnitude increased after October 2, 2016 when��scores of people died at the annual��Irreecha��cultural festival.��(Irrecha��is an important cultural festival of the Oromo people. People gather each year in��Bishoftu, 40km��from Addis to celebrate the end of the rainy season and welcome the harvest season.) The festival followed a stampede��triggered by security forces��� use of teargas and firearms.��It was after this incident that young Oromo protesters��began to attack business establishments by burning them to ground. Some were targeted enterprises that were owned by the��state��and some were multinational corporations.

At first, the protests purposefully created an ethnic-based sentiment that exclusively attempted to address questions that pertained to the Oromo ethnic group (the largest ethnic constituency, followed by the��Amhara). Young protesters called the��kero,��which disturbingly means young unmarried men, were social actors with an identity oriented viewpoint. Later in the movement, the protest encouraged other movements to emerge who apprehensively embraced the demands of the Oromo youth since the movement simultaneously opened a platform to echo their own injustices.��For instance, diaspora social media outlets acted and interacted simultaneously with the��kero��movement,��not only in the mobilization of protest actors but also in the production of political messages.��However, the young Oromo protesters were by far more sophisticated and organized than the other movements that surfaced. The��kero��subsequently became the voice for justice not only for the Oromo ethnic group but also indirectly for other oppressions.

Multiple voices of dissent���Amhara,��Tigrean��and Somali nationalists, among many, who had conflicting perceptions of nationalism and belonging���with multiple utopias, desires, belongings and identifications consequently emerged in social media channels. It remained unclear, however, how and to what extent the political subject maintained and strengthened its commitment to its form of protest. The inequalities, power relations, ethnic based relations in the process of subjection,��required numerous interrogations. But at a volatile moment, these voices of dissent, each with their own history, context and specific intention ended up with general questions of political participation and representation. From a broader perspective, this movement impacted the transformation in politics,��but the significance of these protests��reside��in the realization of social and democratic demands for each voice of protest in their own specific historical context. It is in this regard that questions about the outcome of these social media protests surfaced.

Indeed, with no visible leadership, the��kero��used several strategies of protests and demanded response to core problems affecting the Oromo region,��such as ethnic-based hierarchies, land rights, unemployment and corruption.��Undeterred by the barrage of bullets fired at them,��the��protesters were persistently on the street, sometimes in groups and other times in spontaneous/simultaneous individual attacks on targeted establishments. Although methods of surveillance on internet and mobile communications were at��their��height, activists successfully circumvented the��panopticon��eye, though communication among protesters��was��mostly made through social media outlets.

When��excessive force by law enforcement became unbearable, they became deceptively quiet for a few days only to come back to the streets with entirely nuanced forms of resistance. As Hannah Arendt in her chapter on ideology and terror��in��The Origins of Totalitarianism��states:�����Under totalitarian conditions, fear probably is more widespread than ever before; but fear has lost its practical usefulness when actions guided by it can no longer help to avoid the dangers man fears.��� Simply stated, the historical suppressed subject arose in a new social movement that was significantly different from previous social movements; fragmented, atomized with social actors rallied under identity oriented viewpoints but that ultimately served in amplifying larger oppressed voices.

Previous social movements in the country had brought about the TPLF (Tigray��People���s Liberation Front) to power. The 1974 revolution was a mass uprising that overthrew the imperial government of Emperor Haile Selassie making an end to the��Solomonic��dynasty. But this unprecedented moment was usurped by a self-proclaimed socialist military junta called the��Derg��(1974-1991). Various underground movements, of which the TPLF was part, were formed to topple the military regime. It was after��17��years of guerilla warfare that claimed Marxism Leninism as its core ideology that the TPLF finally took over the State. The TPLF later turned into the EPRDF which was formed under an ethnic constituency. In 1994, the Federal Constitution had ratified a ���multi-cultural federation based on ethno national representation.��� (Ethiopia adopted ethnic federalism and reorganized regions along ethnic lines when the EPRDF came to power in 1991, supposedly to give ethno-regional rights and a federal and democratic structure to previously underrepresented groups.)

As the International Crisis Group���s��Africa Report��(2012)��states: ���The regime not only restructured the state into the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, but also redefined citizenship, politics and identity on ethnic grounds [into] ethnically defined politics that decentralize rather than mitigate inter-ethnic relations.���

In the years that followed the end of state socialism, the EPRDF redefined the nature of politics with new economic, social and institutional agendas. Ideas that were caught somewhere between neo-liberal ideology and�����revolutionary democracy�����began to emerge in official discourse in the 1990s. And by the early to mid-2000s, the politics of the EPRDF had radically��shifted. Increasingly drawn into post-Cold War global economic and political conditions, the�����revolutionary democratic state�����gradually changed to the�����revolutionary developmental state.�����In the absence of an economic model that clearly addressed Ethiopia���s economic relationship to global economic networks and powers, the mediation between leftist rhetoric and capitalist economic policies became disconcerting. Neither revolutionary nor democratic, the State imposed official narratives of progressive economic change over wide gaps in income; and this despite massive unemployment, repression of expression and obscene levels of corruption.

Besides the edifices of politics and identity based on ethnic frameworks, the absence of a genuine multi-party democratic system also became cause for growing tensions. Most importantly, the glaring gaps in income,��which��were��significant��along��ethnic lines, became cause for unrest. The intensified urbanization of Addis Ababa and its expansion to the hinterlands surrounding the city���land that is allotted to Oromo farmers under the federalist state���became the greatest site of contention since Oromo farmers were bought out with a meager sum to give way to corrupt investments. Certainly, impugning Oromo dignity, as a result of land grabbing, was the crucial dispute that the��kero��raised.

But how the process of protest mobilization was��managed,��and how the social networks that set the general discourse of the protest were able to effectively communicate with participants in events/incidents is what is interesting,��and what shaped and formed protest in contemporary Ethiopia.��In this new understanding of social movement��that brought about tremendous change���the resignation of Prime Minister��Hailemariam��Dessalegn��and the appointment of��Abiy��Ahmed, an Oromo leader within the EPRDF, as the new Prime Minister���the multiple timelines of protest also defined the reach and immediacy of protest.

Because��traditional media was under state control, many Ethiopians and particularly the youth turned to online resources to follow the movement. Platforms like��Facebook��served as a space for alternative news sources and for social identification.��They��also served as a stage for the exchange of culture,��such as music and literature that were produced under tyrannical conditions, and most of all, as��media��to express concerns around fairness and justice. Music and poetry,��which particularly became prominent instruments of activism,��were also followed by both Oromo and non-Oromo activists.��Among the many Oromo artists to have played a role in recent events,��notes��law professor��Awol��Allo, ���one musician and one performance stands out.�������Allo��refers to��Haaccaaluu��whose song��Closer��to��Arat��Kilo��galvanized the movement.

In switching between articulations of��precarity��and resilience, writes��Allo:

Haaccaaluu��challenged the audience and the Oromo leadership in the gallery, which included��Abiy��Ahmed,��who was then the deputy president of the Oromo Peoples Democratic Organization (OPDO)��to make bold moves befitting of the Oromo public and its political posture. He urged his audience to look in the mirror, to focus on��themselves, and decolonize their minds. We are, he said, closer to��Arat��Kilo, Ethiopia���s equivalent of Westminster, both by virtue of geography and demography. (���) The Oromo People���s Democratic Organization, the party in the ruling coalition that put��Abiy��forward, thankfully followed��Haaccaaluu���s��advice. After PM��Desalegn��announced his resignation, it fought tooth and nail to secure the position of the Prime Minister. After��Abiy���s��imminent confirmation, the first chapter of a journey for which��Haaccaaluu��has��provided the soundtrack will be complete.

Perhaps one can say it is one of the rare moments in modern Ethiopian history that music became an instrument for dissent.��Indeed,��Haaccaaluu���s��music��electrified the Oromo protest movement. On the other hand, the��notion of the�����we�����in��Haaccaaluu���s��lyric such as�����are��we there yet?�����or�����have we arrived to��Arat��Kilo yet�����made non-Oromo Ethiopians apprehensive. Who are the�����we���?�� Was it only the Oromo ethnic group or did it��include��non-Oromo Ethiopians? Certainly for non-Oromo Ethiopians,��Haaccaaluu���s��music restricted the entrance to the gates of victory.

But��in an ironic way, since��Haaccaaluu���s��lyrics provided the broad political landscape of change in one of the rare moments that the history of resistance and exclusion was openly apprehended, his music, though shy from discussing the notion of the�����we�����also gained energy in non-Oromo social media circles.��Activists chose conformist activism across conversations rather than unpacking the controversial features of ethnic-based politics.��In this regard, while the informality and spontaneity of social media deliberations were fresh and innovative, discussions that surrounded the complexities of issues,��such as the politics of��ethnicity, were��mostly reductive.��It is with all these unresolved tensions that social media activism brought forth the contemporary state of Ethiopia.

An essentialist perception of the social media political subject would be: it disrupted the status quo by playing an instrumental role in the resignation of a prime minister and the appointment of a young and seemingly progressive prime minister from within the same repressive party that is still in power. Shortly after assuming power, the new��Prime��Minister��released hundreds of political prisoners, condemned the practice of torture (that had pervaded the country���s incarceration policy) and legitimized freedom of speech. To this end, the movement��ultimately succeeded in becoming an overarching voice for justice. Yet��without a collective political ideology and a coherent political voice,��how do we constitute and unite the unresolved inventory of multiple micro utopias, desires, identifications and belongings?

All the more striking is that activists claimed the internet as a neutral space in which everyone can uniformly network ignoring crucial issues that pertain to the political economy of the internet, and/or the dominant realities of capitalism and its relationship to the Ethiopian��state��and its economy. Besides understanding that��Facebook��and other social media networks are corporations and new arenas where capitalism can outstretch itself, it is also crucial to recognize the limitations of such kind of protest that arose and continue to exist without a materialistic��analysis of the broader capitalist frame and its impact on the political projects of the��state��and on issues that the militant political subject sought to address.

In an altogether complex way, such activism has presently resulted in the emergence of other political actors after��Abiy��Ahmed���s rise to power; a pluralistic public that has yet to employ the ideologies of a common cause. This lack of a common cause is dangerously reflected in present day persistent skirmishes among the pluralistic public.��I believe we will better understand the compounded voices of protest if we think through new frameworks and alternative models that can open up productive ways for theorizing contemporary social movements.��And I argue an important task is to identify the fundamental ways in which multiple levels of oppression are related to the political economy of class within the framework of late capitalism and its causal mechanisms. Perhaps we should bring back a counter ideology to capitalism into the studies of contemporary movements to re-theorize our fluid identities��that are��shaped by capitalism in multiple ways.

Unfortunately, the new��state��is less concerned with the global capitalist dynamics and its political economic factors on dependent states. Within three months in power, the new prime minister has��appropriated the voices of protest and��is��presently��attempting to incorporate it to party line politics. He tells us��liberalizing the economy would resolve our economic��woes, a swift solution to youth unemployment whose economic disenfranchisement has supposedly galvanized restlessness.��Furthermore,��ethnic conflicts would be resolved through the spirit of ���love.��� Under great pressure from the IMF, stakes in state-held companies like Ethiopian Airlines are to be sold to private investors and industrial parks turned into sweatshops for H&M and other corporations (policies initiated by the previous prime minister) are to be expanded. The threat of authoritarian neo-liberal��developmentalist��projects and��their��uncompromising alteration of social structures will continue��to flourish. In this regard, doubts remain as to the longer impact that these protests have made in achieving major political changes.

Parts of this post were presented as a paper to the Winter School of the University of the Western Cape (UWC), South Africa in July 2018.

August 27, 2018

The global ways of white supremacy

Donald Trump speaking with supporters at a campaign rally at the Phoenix Convention Center in Phoenix, Arizona. Image credit Gage Skidmore via Flickr.

White supremacy has never operated in isolation. While it has always asserted��its malevolence��in local and��national politics, it has consistently��relied��on an international receptivity and interdependence, whether formal or informal.��Activists and intellectuals��cited such connections time and time again during��the��20th��century.��Consider, for example,��what Nelson Mandela writes in��Long Walk to Freedom��(1994), when comparing the South African situation to Algeria, remarking, ���The situation in Algeria was the closest model to our own in that the rebels faced a large white settler��community that��ruled��the indigenous majority.��� Or consider��an��observation by Frantz Fanon in��The Wretched of the Earth��(1961), as if in an imagined��dialogue��with Mandela, when he concludes, ���The colonial subject is a man penned in; apartheid is but one method of compartmentalizing the colonial world.��� Or, in��the American context, consider��Malcolm X and��his��geographically��expansive�����Message to the Grassroots��� speech���ranging��from Bandung,��to��Kenya, to Cuba, to��Detroit���delivered��in 1963, in which he states:

We have a common enemy. We have this in common: we have a common oppressor, a common exploiter, and a common discriminator.��But once we all realize that we have a common enemy,��then��we unite���on the basis of what we have in common.��And what we have foremost in common is��that enemy���the white man. He���s an enemy to all of us.

In��The Origins of Totalitarianism��(1951), Hannah Arendt attempted to��pull together this dispersed racialization and its political effects��into a single framework, outlining��how the roots of authoritarianism and the Holocaust��in Europe during the Second World War were not, in fact, European alone, but could be located to the colonies���in part, the ���race society��� that had been constructed in South Africa. In her words:

South Africa���s race society taught the mob the great lesson of which it had always had a confused premonition, that through sheer violence an under-privileged group could create a class lower than itself, that for this purpose it did not even need a revolution but could band together with groups of the ruling classes, and that foreign or backward peoples offered the best opportunities for such tactics.

Aim����C��saire��drew a similar conclusion��several years later��in��Discourse on Colonialism��(1955), forcefully��writing��that:

before they��[Europeans]��were its victims, they were its accomplices; that they tolerated that Nazism before it was inflicted on them, that they absolved it, shut their eyes to it, legitimized it, because, until then, it had been applied only to non-European peoples.

Both referred to this malignant��intercontinental��circulation of white supremacy��as a ���boomerang effect.���

Scholars have��built upon this argument for interdependence��in different ways. George Fredrickson pioneered an approach of comparative history between the United States and South Africa in his tersely��titled��White Supremacy��(1981), a three-hundred-year revisionist history of the two countries from Jamestown to the Soweto Uprising.��Neither country was ���exceptional��� as claimed by their founders, but instead based on interrelated patterns of settler colonialism, the displacement and extermination of indigenous peoples, dependence on slavery, and the segregation and exploitation of black labor as part of a process of ���modernization.�����Tiffany Willoughby-Herard��has more recently examined the��exchange��of scientific racism and ���segregationist philanthropy�����between both countries��through the activities of the American Carnegie Corporation���in particular,��its��financial and technical��support for addressing the ���poor white problem�����during the interwar period���in��Waste of a White Skin��(2015).

Inspired by��W. E. B. Du��Bois���s��enduring��assertion that��the problem of the��20th��century was�����the problem of��the��color line,�����Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds have��embraced a larger imperial scale,��tracing��the emergence of a transnational whiteness specific to the late��19th��and early��20th��centuries��that formed as a defensive reaction to��what an Australian politician called��the rising power of ���the black and yellow races.�����Among many cases��in their book,��Drawing the Global��Colour��Line��(2008),��is the collaboration and friendship between US President Woodrow Wilson and South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts, two arch-segregationists who shared��common ground��ideologically and politically��and, as a result, ultimately limited the possibilities of self-determination through��the League��of Nations, in which��both��were��involved. In��his statistic-laden��Replenishing the Earth��(2009), James��Belich��has��taken this global approach further back, describing��what he calls the ���Settler Revolution������a historical shift��akin��to the Industrial Revolution���in the American West and the British West (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa)��during the��19th��century,��occasioning��the creation of what he��calls (chillingly, to my mind)��the Anglo-World.

Against this backdrop of scholarship and activism, the specious absurdities of��Tucker Carlson and the Trump administration��last week��are less surprising, but no less threatening. In��Critique of Black Reason��(2017),��Achille��Mbembe��has written that ���the fantasy of Whiteness��� is never spontaneous; it has been ���cultivated, nourished, reproduced, and disseminated by a set of theological, cultural, political, economic, and institutional mechanisms��� that have evolved over centuries. As such, whiteness��has been transformed into common sense, but also��into��an object of incessant desire and��unremitting��fascination.��AfriForum��and its international correspondents, whether the Alternative for Germany (AfD) or the French��Rassemblement��national��(formerly the��National Front), understand this��perverse enchantment and its potential for political mobilization, as do members of the Alt-Right in the US.��(Although��it should be stressed that��AfriForum��is far more marginal��in South Africa��than these��parallel��dangers��in Europe and the United States.)

The ways of white supremacy are neither local nor episodic, but recurrent and international.��Over a century after his��original injunction,��we still inhabit Du��Bois���s��world.

August 26, 2018

Xenophobia and party politics in South Africa

Street market in Hillbrow, Johannesburg. Image credit Joonas Lyytinen via Wikimedia commons.

With the campaigning for the 2019 national elections gripping South African politics, all kinds of xenophobic statements are uttered by most political parties who see anti-immigrant, xenophobic and��Afrophobic��rhetoric as a way to attract votes.��Through blatant lies,��othering��and scaremongering, foreigners are blamed for many of South Africa���s woes and social ills.��All political parties are guilty.

In a society where��violence against foreign nationals��is pervasive and xenophobic sentiments are common, irresponsible leaders continue to manufacture an atmosphere of crisis. Politicians claim that foreigners are��flooding South Africa��and undermining country���s security, stability and prosperity. Yet,��according to the 2011 census, South Africa isn���t overwhelmed with immigrants, with some 2.2 million international migrants (about 4% of the population) in the country in 2011.��Stats SA Community Survey 2016��puts the number of foreign born people at 1.6 million, out of the population of 55 million at the time. While there are a number of methodological issues with the Stats SA Community Survey, it would not be surprising if this figure is correct, especially as the Department of Home Affairs has��deported close to 400,000 foreign nationals��since 2012.

South Africa is one of the���most unequal countries in the world. More than half of the population lives in poverty. The inequality and hardships experienced by��the majority of��South Africans are rooted in the country���s colonial and apartheid racist��legacy, as well as the post-1994 failures to transform the economy and society. Yet, listening to many politicians one gets the impression it���s all the immigrants��� fault.

Both the African National Congress-led government and the Democratic Alliance want to��build higher fences at the border��to prevent foreigners from coming in and undermining South Africa���s socio-economic development and security. Politicians claim that foreigners are the��main reason for��high crime rates; immigrants are��blamed for the hardships��experienced by poor South Africans and for��overrunning��South Africa���s cities.

In 2017, South Africa���s deputy police minister��claimed��that the city of Johannesburg was taken over by foreigners, with 80% of the city controlled by them. If this is not urgently��stopped,���he added, the entire country�����could be 80% dominated by foreign nationals and the future president of South Africa could be a foreign national.�����The mayor of Johannesburg often��speaks��about�����our people�����and�����those people�����(the foreigners) who make South Africa into a�����lawless society.�����The Economic Freedom Fighters��has��questioned��whether those born outside the country���even����the��people born abroad to South African parents���can��ever be trusted or regarded as�����proper South Africans.���

While speaking about their plans to run a coalition government on the national level if they get enough votes in 2019, the Democratic Alliance, COPE and the right-wing Freedom Front Plus��promised��to place foreigners in camps��rather than letting them roam free in South African��cities.��The��African Basic Movement, a newly registered political party, has called��for all foreigners to leave��South Africa by the end of 2018. The party claims that foreigners plan to take over the country in a few years and thus must be stopped by any means. They also want to make it illegal for foreigners to marry South African citizens.

The��Democratic Alliance is approaching the next year���s elections with a new nationalistic slogan�����All South Africans First.�����As an��editorial in the Mail & Guardian��recently pointed out, this slogan is�����pandering to a sentiment among South Africans that��others��poor immigrants.�����This is nothing but�����an attempt to co-opt the nationalism [and anti-immigrant rhetoric] so in vogue in much of the rest of the world right now.���

None of this anti-immigrant rhetoric is based on��evidence. The research shows that immigrants��don���t steal jobs��from South��Africans and that��foreigners are not responsible��for high levels of crime. The majority of foreign nationals also don���t receive any support from the government, such as��social grants, and have to fend for themselves for survival. But facts don���t seem to matter in South African politics.��Why��would politicians choose to��face��the rightful anger��millions of poor and hopeless South Africans when��they��can��revert to��anti-immigrant rhetoric and shift��blame to those who have no voice, the people who make up��between three to four percent of the population?

If, or rather when xenophobic��violence explodes and immigrants are beaten, displaced, tortured, killed and/or burned alive, while their property and possessions are looted���as��has��happened many times in the past���the��politicians will say this has nothing to do with xenophobia. It���s just��criminality. The politicians will��take no responsibility for fueling��xenophobic sentiment.��Denialism��will be the order of the day.

While the opposition parties��spout��xenophobic rhetoric and bigotry, the African National Congress-led government has already developed and approved anti-poor and anti-African immigration plans. The government sees poor and unskilled African migrants and asylum seekers as threats to country���s security and prosperity. The��White Paper on International Migration, approved by the government in March 2017, separates immigrants into�����worthy�����and�����unworthy�����individuals. Foreigners who have skills and money are welcome��to come to the country and can stay in South Africa permanently.��Poor and unskilled immigrants,��who are predominantly from the African continent,��will be prevented from coming to and staying in South Africa by any means,�����even if this is��labelled��anti-African behavior,�������as the former Minister of Home Affairs,��Hlengiwe��Mkhize,��pointed out in June 2017.

The immigration��debate in South Africa��is framed around whether foreigners can benefit the economy.��Separating immigrants into those who can contribute to country���s economy and those who can���t is rooted in��racist, white supremacist, classist and��ableist��thinking.��Thus,��South Africa���s new immigration��policy��mirrors��the United States, Australia and much of Western Europe.����Only the��exceptional, privileged, skilled, productive and well-off are welcome.��The��unworthy,��from��shithole countries��will��be denied access.

One of the most controversial aspects of the White Paper on International Migration is the plan to establish��asylum seeker processing centers. These centers will be used for detention of asylum seekers while their applications are being processed by the South African authorities.��The use of blanket detention to manage international migration would be��in breach of the South African Constitution.

South African president, Cyril���Ramaphosa, recently��strongly rejected���the proposals to build detention centers for African migrants in North Africa aimed at curbing migration to Europe.��Ramaphosa��said that this is ���akin to creating prisons for the people of our continent and I can���t see how African leaders can accede to that.��� Yet, his government plans to��follow similar proposals.

It is important to remember that���the large majority of those who reject or dislike foreigners in South Africa are��anti-black immigrant and��Afrophobic. White foreigners and immigrants don���t experience xenophobia in South Africa.��It is��reserved mainly for poor black foreigners��from the��African continent.

Xenophobic and��Afrophobic��bigotry remains the order of the day in the�����Rainbow Nation�����and is likely to��get uglier as the electioneering heats up.��We will��continue to hear the politicians put the blame on foreign migrants, asylum seekers and refugees for many of the social ills and hardships experienced by��the majority of��South Africans.��One would��expect better of the country���s political leadership, but South Africa��isn���t there yet.

Xenophobia trumps ubuntu in South African politics

Street market in Hillbrow, Johannesburg. Image credit Joonas Lyytinen via Wikimedia commons.

With the campaigning for the 2019 national elections gripping South African politics, all kinds of xenophobic statements are uttered by most political parties who see anti-immigrant, xenophobic and��Afrophobic��rhetoric as a way to attract votes.��Through blatant lies,��othering��and scaremongering, foreigners are blamed for many of South Africa���s woes and social ills.��All political parties are guilty.

In a society where��violence against foreign nationals��is pervasive and xenophobic sentiments are common, irresponsible leaders continue to manufacture an atmosphere of crisis. Politicians claim that foreigners are��flooding South Africa��and undermining country���s security, stability and prosperity. Yet,��according to the 2011 census, South Africa isn���t overwhelmed with immigrants, with some 2.2 million international migrants (about 4% of the population) in the country in 2011.��Stats SA Community Survey 2016��puts the number of foreign born people at 1.6 million, out of the population of 55 million at the time. While there are a number of methodological issues with the Stats SA Community Survey, it would not be surprising if this figure is correct, especially as the Department of Home Affairs has��deported close to 400,000 foreign nationals��since 2012.

South Africa is one of the���most unequal countries in the world. More than half of the population lives in poverty. The inequality and hardships experienced by��the majority of��South Africans are rooted in the country���s colonial and apartheid racist��legacy, as well as the post-1994 failures to transform the economy and society. Yet, listening to many politicians one gets the impression it���s all the immigrants��� fault.

Both the African National Congress-led government and the Democratic Alliance want to��build higher fences at the border��to prevent foreigners from coming in and undermining South Africa���s socio-economic development and security. Politicians claim that foreigners are the��main reason for��high crime rates; immigrants are��blamed for the hardships��experienced by poor South Africans and for��overrunning��South Africa���s cities.

In 2017, South Africa���s deputy police minister��claimed��that the city of Johannesburg was taken over by foreigners, with 80% of the city controlled by them. If this is not urgently��stopped,���he added, the entire country�����could be 80% dominated by foreign nationals and the future president of South Africa could be a foreign national.�����The mayor of Johannesburg often��speaks��about�����our people�����and�����those people�����(the foreigners) who make South Africa into a�����lawless society.�����The Economic Freedom Fighters��has��questioned��whether those born outside the country���even����the��people born abroad to South African parents���can��ever be trusted or regarded as�����proper South Africans.���

While speaking about their plans to run a coalition government on the national level if they get enough votes in 2019, the Democratic Alliance, COPE and the right-wing Freedom Front Plus��promised��to place foreigners in camps��rather than letting them roam free in South African��cities.��The��African Basic Movement, a newly registered political party, has called��for all foreigners to leave��South Africa by the end of 2018. The party claims that foreigners plan to take over the country in a few years and thus must be stopped by any means. They also want to make it illegal for foreigners to marry South African citizens.

The��Democratic Alliance is approaching the next year���s elections with a new nationalistic slogan�����All South Africans First.�����As an��editorial in the Mail & Guardian��recently pointed out, this slogan is�����pandering to a sentiment among South Africans that��others��poor immigrants.�����This is nothing but�����an attempt to co-opt the nationalism [and anti-immigrant rhetoric] so in vogue in much of the rest of the world right now.���

None of this anti-immigrant rhetoric is based on��evidence. The research shows that immigrants��don���t steal jobs��from South��Africans and that��foreigners are not responsible��for high levels of crime. The majority of foreign nationals also don���t receive any support from the government, such as��social grants, and have to fend for themselves for survival. But facts don���t seem to matter in South African politics.��Why��would politicians choose to��face��the rightful anger��millions of poor and hopeless South Africans when��they��can��revert to��anti-immigrant rhetoric and shift��blame to those who have no voice, the people who make up��between three to four percent of the population?

If, or rather when xenophobic��violence explodes and immigrants are beaten, displaced, tortured, killed and/or burned alive, while their property and possessions are looted���as��has��happened many times in the past���the��politicians will say this has nothing to do with xenophobia. It���s just��criminality. The politicians will��take no responsibility for fueling��xenophobic sentiment.��Denialism��will be the order of the day.

While the opposition parties��spout��xenophobic rhetoric and bigotry, the African National Congress-led government has already developed and approved anti-poor and anti-African immigration plans. The government sees poor and unskilled African migrants and asylum seekers as threats to country���s security and prosperity. The��White Paper on International Migration, approved by the government in March 2017, separates immigrants into�����worthy�����and�����unworthy�����individuals. Foreigners who have skills and money are welcome��to come to the country and can stay in South Africa permanently.��Poor and unskilled immigrants,��who are predominantly from the African continent,��will be prevented from coming to and staying in South Africa by any means,�����even if this is��labelled��anti-African behavior,�������as the former Minister of Home Affairs,��Hlengiwe��Mkhize,��pointed out in June 2017.

The immigration��debate in South Africa��is framed around whether foreigners can benefit the economy.��Separating immigrants into those who can contribute to country���s economy and those who can���t is rooted in��racist, white supremacist, classist and��ableist��thinking.��Thus,��South Africa���s new immigration��policy��mirrors��the United States, Australia and much of Western Europe.����Only the��exceptional, privileged, skilled, productive and well-off are welcome.��The��unworthy,��from��shithole countries��will��be denied access.

One of the most controversial aspects of the White Paper on International Migration is the plan to establish��asylum seeker processing centers. These centers will be used for detention of asylum seekers while their applications are being processed by the South African authorities.��The use of blanket detention to manage international migration would be��in breach of the South African Constitution.

South African president, Cyril���Ramaphosa, recently��strongly rejected���the proposals to build detention centers for African migrants in North Africa aimed at curbing migration to Europe.��Ramaphosa��said that this is ���akin to creating prisons for the people of our continent and I can���t see how African leaders can accede to that.��� Yet, his government plans to��follow similar proposals.

It is important to remember that���the large majority of those who reject or dislike foreigners in South Africa are��anti-black immigrant and��Afrophobic. White foreigners and immigrants don���t experience xenophobia in South Africa.��It is��reserved mainly for poor black foreigners��from the��African continent.

Xenophobic and��Afrophobic��bigotry remains the order of the day in the�����Rainbow Nation�����and is likely to��get uglier as the electioneering heats up.��We will��continue to hear the politicians put the blame on foreign migrants, asylum seekers and refugees for many of the social ills and hardships experienced by��the majority of��South Africans.��One would��expect better of the country���s political leadership, but South Africa��isn���t there yet.

August 24, 2018

What would happen if the women cut their ribbons?

Still from I Am Not a Witch.

A strange image appears throughout Welsh-Zambian director��Rungano��Nyoni���s��beautiful and haunting film��I Am Not a Witch,��and I can���t get it out of my head. A dozen or so elderly women wearing ragged dark blue overalls and scarves over their hair, sit together, expressionless, on the bed of an orange 18-wheeler truck. Each woman has a harness attached at her shoulder blades connecting her to a spool of ribbon. The spools are affixed to poles that jut out all along the bed of the truck. When the truck is parked, the women fan out across the landscape, their ribbons crisscrossing the horizon and flapping in the wind. As each woman walks further away from the base, her spool turns to unfurl the ribbon. To bring her back to the base, a supervisor need only turn the spool��in��the opposite direction to wind her in. What would happen if the women cut their ribbons? Why don���t they? After all, it is only ribbon and not chain. What is really keeping them tethered?

This is the unstated question that runs throughout��I Am Not a Witch. The premise of the film is this: villagers in a town in rural Zambia accuse a mysterious��girl, played by Maggie��Mulubwa, of witchcraft. A government official, Mr. Banda, played by Henry BJ Phiri, is called to the scene and takes the girl to a witch camp, populated by the elderly witches in blue overalls, each tethered to a spool of ribbon. Mr. Banda and his lackeys attach her to the end of a ribbon and send her alone to a hut for the night with a pair of scissors and these instructions: leave the ribbon intact and join the witch camp or cut the ribbon and immediately turn into a goat. She leaves the ribbon intact, and the remainder of the film explores that choice.

The girl does not say much. It is through encounters with others that her character is��both developed and restrained. The senior witches name her ���Shula,��� which means ���abandoned.��� They assure her that she has it easy compared to the olden days: the ribbons are so much longer now; back in the olden days, you could barely turn around, the ribbons were so short. Mr. Banda sees in Shula an opportunity for power and profit. He takes her around on official government errands, exploiting her powers to bolster his authority, and he markets Shula brand eggs on national television. Banda���s stylish wife Charity (Nancy��Murilo) takes pity on Shula and welcomes her into her lavish home, and, pointing to her own wedding ring, tells her there is only one way out of��witchhood: respectability. Meanwhile, a drought ravages the region and the queen, played by Pulani��Topham, insists that the future of the community is in Shula���s hands: the girl must make rain. Idiotic tourists come to the witch camp to ogle Shula, speaking to her in saccharine tones before snapping selfies with her.

Within��Nyoni���s��macabre premise, we recognize traces of our own world. We are told by corporations, NGOs, politicians and culture-makers what girls are.�� Girls are an investment. Girls are the future. Girls are consumers. Girl power! Girls are dangerous���they can disrupt the social order and so must be taught to behave. Girls are vulnerable,��and only you can save them. Their��fate, we are told,��is��the fate of the world. But what is it like to be this figure upon which so much depends?

Nyoni���who both directed and wrote the screenplay for��I Am Not a Witch���does not use the Shula character to ventriloquize our fantasies or clich��s about girlhood: Shula is not cuddly, or heroic, or virtuous, or kick-ass. She is robustly and intricately human. Maggie��Mulubwa, the young actress who plays Shula, explores the emotional contours of her predicament with great nuance. Tears streak her cheeks when she is lonely and overwhelmed by the demands placed on her. She narrows her eyes and sets her jaw when vindictive, and as she becomes aware of her limited power, she sometimes uses it to harm others. At other times, she gazes into��the��distance, resigned and depressed. Her face and body relax into an expression of pure joy on the few occasions when she is free to just play with other children.

This film is simultaneously heartbreaking and hilarious. Much of the credit for the film���s humor is due to Henry BJ Phiri in the role of Mr. Banda. We first encounter his character from behind as he reclines in a bubble-filled bathtub, his flesh virtually flowing over the sides of the tub, slippery like a dolphin while his wife labors to scrub and clean his body. We watch��him��scramble on hands and knees as he grovels before the queen, and we watch him pathetically use his power to bully the weak.

There is comedy throughout the film. A somber trial in which Shula must use her��witchly��powers to identify a thief from a lineup of suspects is interrupted repeatedly by the sound of a funky, zippy version of ���Old MacDonald��� emanating from the pocket of the accuser: an elderly man dressed in a suit and thick glasses who cannot figure out how to silence his phone. In another scene, the senior witches primp and pucker in the mirror while they try on garish red and blue and pink and blond wigs, and they get sloppy-drunk on gin at nighttime.

Is Shula a witch? Maybe she���s just a child, an earnest member of the public suggests when calling into a television talk show where Shula is on display in full��witchy��regalia, complete with feathers and face paint. The awkward silence that ensues leaves us to ponder what that would mean, what adjustments would have to be made,��and��whose expectations released?��The question is not so much whether or not witches are real, but rather what everybody would have to give up if the ribbons were cut.

August 23, 2018

The core of Samir Amin’s politics

Image credit Skill Lab via Flickr.

There is a luminous anecdote in the memoirs of the Egyptian Marxist Samir Amin, who died August 12, 2018. At age six, he was with his family in the city of Port Said. He saw a child picking up garbage from the street to eat. Why, he asked his mother, was the boy doing that? ���Because the society we have is bad,��� said his mother. ���Then I���ll change society,��� Amin answered.

Amin was born��in��1931��in Egypt to an Egyptian father and French mother. He later studied in Paris, including under the radical structuralist economist Francois Perroux, and defended a dissertation in 1957 dissecting and anatomizing then-modish theories of development and economics, from modernization theory to��marginalism. He substituted for such social science fiction an inherently hierarchical and inherently global world-system���one which rested on enfolding, shackling, looting, and stunting what came to be the colonial world and then the periphery.

From there, he plunged into the nuts-and-bolts of planning in populist governments of the Third World. He worked for the Egyptian government from 1957-1960 and in Mali from 1960-1963. From 1963-1970 he was in Dakar, at the Institut Africain de D��veloppement ��conomique et de Planification (IDEP), a pan-African institution meant to train and deepen the knowledge base in development planning of post-colonial African technical attaches, bureaucrats, and leaders. He left IDEP and founded the Third World Forum, which took shape in 1973, and��was��a network of intellectuals spanning Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The Forum was another effort to provide intellectual space for interchange around anti-systemic developmental thought,��and��scaffolding for research programs. Since then, Amin was involved and in supporting roles with radical movements across the Tri-Continental arena.

Amin���s contributions to historical social science���and revolutionary theory���span an almost boggling breadth. His masterwork, eventually published as��Accumulation on a World Scale, was a revision of his doctoral thesis. He mapped the mechanisms through which value flowed from South to North, maintaining an international division of labor and a geographically uneven distribution of wealth and want. Avant la lettre, he clarified that the core-periphery distinction was based on uneven levels of development through value extraction, and not any specific technical pattern of production. Heavy industrialization did not need to mean development. In��this work, he was a forerunner and a parallel founder of the most novel approach to advancing Leninist and Luxembourgist analyses of imperialism: dependency theory.

Based on this conception, he put forth a radically novel notion: delinking. Pilloried and misinterpreted by Eurocentric Marxists and modernizers alike, Amin argued that insofar as Third World social formations accepted their subservient incorporation into global capitalism, they would remain underdeveloped. He did not write a brief for autarky. Instead, he argued for countries to develop their productive systems according to a popular law of value and through popular participation. They would decide how much industry, how much agriculture, and what techniques ought to be used in each sector. In this way, rather than peripheries passively accepting the adjustments imposed by the capitalist core, they would decide on the shape and pattern of their relationship to the world trading system. The core would adjust to the periphery than the periphery adjusting to the core.

The Bandung moment, the Rise of the South, was a political mooring point. Although he was acutely aware from direct study of the limits and constraints of post-colonial developmentalism, he was equally aware as he saw unfolding in front of his eyes a movement towards the re-assertion of the sovereignty and dignity of the Third World after the calamity of colonialism. The Rise of the South sought to demolish politically what Amin aimed to eradicate intellectually through his book��Eurocentrism, where he deconstructed the mythology of European centrality to world culture, and how supremacist myth justified the material ambitions of Euro-American capitalism.

Amin looked askance on one after another fad emerging from the intellectual factories of the First World, especially the post-USSR negation of the category of imperialism. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri���s replacement of imperialism with an amorphous everywhere-nowhere empire and their twinned replacement of worker with ���multitude��� were one example. Amin saw imperialism alive if not exactly well, and its underbelly, a shapeshifting process of primitive accumulation and folding peripheral workers into the law of value, equally omnipresent.

Amin���s influence on the continent of his birth especially was enormous. In Dakar he was in constant exchange with radical economists and the luminaries of the left, in Africa and elsewhere. He used IDEP���s infrastructure to host the earliest versions of CODESRIA, the premier continental academic association headquartered in Dakar, which became a central point for��the��rejuvenation of African social science. In the Middle East he was a touchstone of debates on independent development, and in the Maghreb his work was central to studies of dependency.

His work and vision did not ossify as he aged. He was directly involved with the World Social Forum process. As the 90s turned to the 2000s and the 2010s, he turned his attention to the ecological destruction wrought by monopoly capitalism, its inability to resolve the climate crisis, and the need for a socialist alternative. He warmed to and supported the movements clustering around the slogan of food sovereignty, as an important component of a broader anti-systemic project.

Although Amin has left this world, like a dying star the path ahead remains illuminated by the brilliant light he cast,��and will remain so for some time to come. What remains is to walk it.

The core of Samir Amin

Image credit Skill Lab via Flickr.

There is a luminous anecdote in the memoirs of the Egyptian Marxist Samir Amin, who died August 12, 2018. At age six, he was with his family in the city of Port Said. He saw a child picking up garbage from the street to eat. Why, he asked his mother, was the boy doing that? ���Because the society we have is bad,��� said his mother. ���Then I���ll change society,��� Amin answered.

Amin was born��in��1931��in Egypt to an Egyptian father and French mother. He later studied in Paris, including under the radical structuralist economist Francois Perroux, and defended a dissertation in 1957 dissecting and anatomizing then-modish theories of development and economics, from modernization theory to��marginalism. He substituted for such social science fiction an inherently hierarchical and inherently global world-system���one which rested on enfolding, shackling, looting, and stunting what came to be the colonial world and then the periphery.

From there, he plunged into the nuts-and-bolts of planning in populist governments of the Third World. He worked for the Egyptian government from 1957-1960 and in Mali from 1960-1963. From 1963-1970 he was in Dakar, at the Institut Africain de D��veloppement ��conomique et de Planification (IDEP), a pan-African institution meant to train and deepen the knowledge base in development planning of post-colonial African technical attaches, bureaucrats, and leaders. He left IDEP and founded the Third World Forum, which took shape in 1973, and��was��a network of intellectuals spanning Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The Forum was another effort to provide intellectual space for interchange around anti-systemic developmental thought,��and��scaffolding for research programs. Since then, Amin was involved and in supporting roles with radical movements across the Tri-Continental arena.

Amin���s contributions to historical social science���and revolutionary theory���span an almost boggling breadth. His masterwork, eventually published as��Accumulation on a World Scale, was a revision of his doctoral thesis. He mapped the mechanisms through which value flowed from South to North, maintaining an international division of labor and a geographically uneven distribution of wealth and want. Avant la lettre, he clarified that the core-periphery distinction was based on uneven levels of development through value extraction, and not any specific technical pattern of production. Heavy industrialization did not need to mean development. In��this work, he was a forerunner and a parallel founder of the most novel approach to advancing Leninist and Luxembourgist analyses of imperialism: dependency theory.

Based on this conception, he put forth a radically novel notion: delinking. Pilloried and misinterpreted by Eurocentric Marxists and modernizers alike, Amin argued that insofar as Third World social formations accepted their subservient incorporation into global capitalism, they would remain underdeveloped. He did not write a brief for autarky. Instead, he argued for countries to develop their productive systems according to a popular law of value and through popular participation. They would decide how much industry, how much agriculture, and what techniques ought to be used in each sector. In this way, rather than peripheries passively accepting the adjustments imposed by the capitalist core, they would decide on the shape and pattern of their relationship to the world trading system. The core would adjust to the periphery than the periphery adjusting to the core.

The Bandung moment, the Rise of the South, was a political mooring point. Although he was acutely aware from direct study of the limits and constraints of post-colonial developmentalism, he was equally aware as he saw unfolding in front of his eyes a movement towards the re-assertion of the sovereignty and dignity of the Third World after the calamity of colonialism. The Rise of the South sought to demolish politically what Amin aimed to eradicate intellectually through his book��Eurocentrism, where he deconstructed the mythology of European centrality to world culture, and how supremacist myth justified the material ambitions of Euro-American capitalism.

Amin looked askance on one after another fad emerging from the intellectual factories of the First World, especially the post-USSR negation of the category of imperialism. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri���s replacement of imperialism with an amorphous everywhere-nowhere empire and their twinned replacement of worker with ���multitude��� were one example. Amin saw imperialism alive if not exactly well, and its underbelly, a shapeshifting process of primitive accumulation and folding peripheral workers into the law of value, equally omnipresent.

Amin���s influence on the continent of his birth especially was enormous. In Dakar he was in constant exchange with radical economists and the luminaries of the left, in Africa and elsewhere. He used IDEP���s infrastructure to host the earliest versions of CODESRIA, the premier continental academic association headquartered in Dakar, which became a central point for��the��rejuvenation of African social science. In the Middle East he was a touchstone of debates on independent development, and in the Maghreb his work was central to studies of dependency.

His work and vision did not ossify as he aged. He was directly involved with the World Social Forum process. As the 90s turned to the 2000s and the 2010s, he turned his attention to the ecological destruction wrought by monopoly capitalism, its inability to resolve the climate crisis, and the need for a socialist alternative. He warmed to and supported the movements clustering around the slogan of food sovereignty, as an important component of a broader anti-systemic project.

Although Amin has left this world, like a dying star the path ahead remains illuminated by the brilliant light he cast,��and will remain so for some time to come. What remains is to walk it.

August 22, 2018

The now neglected history of Soviet anti-colonialism

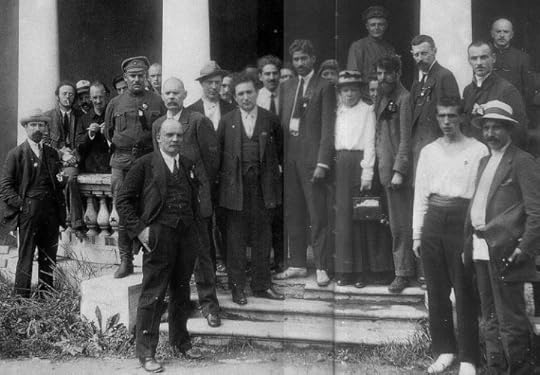

Roy in center with Lenin at the 2nd congress of the Communist International, 1946. Public Domain image.

In 1920, prior to the second Congress of the��Comintern, Lenin circulated a draft of his theses on ���The Question of Colonized People and Oppressed Minorities.��� The end-result of this was the inclusion in the ���21 Conditions��� for��Comintern��membership, of an obligation to provide ���direct aid to the revolutionary movements among the dependent and underprivileged nations and in the colonies.��� While often cited by Marxists as evidence of the Bolshevik���s commitment to anti-imperialism, few cite the role of colonized activists in its formation.

Lenin���s theses were revisionist in two senses. Firstly, they cast anti-imperialism as a priority of the movement, and expanded from class reductionism and Euro-centrism on several issues. Secondly, they contributed to the idea of labor aristocracy. These ideas, while not entirely new, were closely linked with an Indian delegate for the Mexican Communist Party, MN Roy, the prime source of pressure on Lenin to expand upon his theses.

Pre-1917 Marxist theory held that revolution would originate in the industrial nations of Western Europe, or the United States, the industrial proletariat holding the greatest revolutionary potential. By 1920, socialist revolution in Western Europe that Lenin and other Marxists had hoped for, had either failed to materialize, or been put down, as in Germany and Hungary. Russia, where revolution had endured, was an agricultural nation with sluggish industrial development. It was also a territory with extensive populations of non-Russians, many who had come under Petrograd���s rule within the last century. During the early years of the revolution, the question of whether Russia needed to undergo a period of liberal-capitalist rule as opposed to a transition directly to socialism had divided the Left. By 1920, many of the nationalist-liberal governments that had emerged in the Caucuses, Far East, and Central Asia had collapsed under pressure from both the Red and White movements.

While the Bolshevik government established socialism through force, other colonies and stateless peoples of the world were under the control of powers that had stymied political participation and development. Colonizers had elevated an educated strata of the colonized, often already elites prior to colonization. Despite this, many had come to develop ideas of nationalism, and formulate critiques of foreign rule. Of positions of privilege, these figures and their parties, were cautiously moderate in demands and methods.

Lenin, and many other influential European socialists held the view that in colonies, ���feudal or patriarchal-tribal relations were prevalent.��� Concurrently, the view that the colonial bourgeois was opposed to imperialism was true in the sense that this class was, at the time, the driving force in formal political anti-colonialism. Lenin���s theses called for communists to remain independent, but to collaborate with bourgeois-liberal nationalists. Roy met with Lenin several times following his circulation of the draft thesis, and while the exact nature of these meetings has escaped record, Lenin considered Roy���s critiques to be sufficiently constructive to warrant amendment.

Roy���s primary challenge to Lenin���s draft was that collaboration with national-bourgeois would be self-defeating in the twofold struggle for emancipation that colonized peoples would have to engage in, not to mention the struggle of white socialists. Roy was skeptical of the idea that the national-bourgeois would act as revolutionaries, and that if they were to succeed, would only subject colonized peoples to continued exploitation, while strengthening their political position, dampening the efforts of colonized socialists. While the bourgeois did play a significant role in nationalist movements, this did not mean that they would pave the way for liberal political development, nor would they act to deconstruct the intra-colonial hierarchy.

Roy argued that instead of collaboration, communists should attempt to step to the forefront and actively pursue leadership. Roy further emphasized the necessity of colonial, and ultimately racial struggle. Not only could white workers be ideologically pitted against their colonized counterparts, but they could also be appeased through reformist concessions built on colonial loot. Roy noted firstly, as Lenin would concede, the importance of the subservience of colonies to the metropole, in capitalism���s growth, and the rapid advances in the industrial nations. Thus, capitalists states would be ultimately comfortable ���sacrificing the entire surplus value in the home country so long as it continues in the position to gain its huge super-profits in the colonies��� stymying the work of western comrades.

Ultimately, many of the most radical elements of Roy���s supplemental theses were not adopted, most prominently, emphasis upon the centrality of colonial liberation to worldwide revolution. Nevertheless, the changes that were implemented, most importantly the necessity of communist parties to provide support to national liberation struggles, and the ambiguity of the relationship between bourgeois national liberation movements and communists provided a great moral and political boost to socialists of color, and laid the base for the USSR���s later support of struggles from Mozambique to Vietnam. At the same time, it established the precedent that would culminate in the Socialist Bloc���s support, or silence towards regimes that decimated their revolutionary left.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers