Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 227

March 18, 2019

The stuttering development of a radical electoral alternative in Nigeria

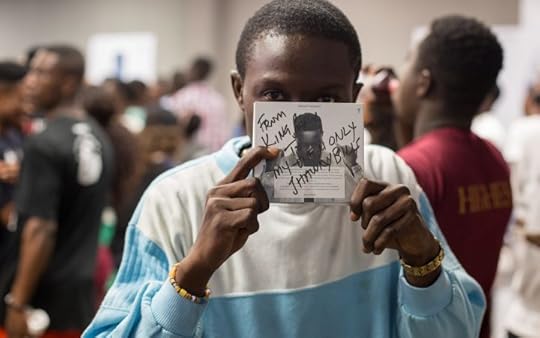

Image Credit Omoyele Sowore via Twitter.

Omoyele��Sowore, the farthest left candidate in Nigeria���s just concluded presidential election, did not even manage to come third. President Muhammadu Buhari of the All Progressives Congress (APC) secured re-election with 15.2 million votes, against 11.3 million for Atiku Abubakar of the People���s Democratic Party (PDP).��Sowore���s��African Action Congress (AAC), in contrast, gained only 33,000 votes, finishing seventh place.

It was an abysmal performance for a candidate backed by some of Nigeria���s most active radical groups, including the Joint Action Front (JAF), the Campaign for Workers and Youth���s Alternative (CWA), and the newly registered Socialist Party of Nigeria (SPN).

Sowore��has��built��a��reputation which appeals to a certain strata of Nigeria���s youth population. He first came to prominence��when, as��a member of student union movements, he helped��fight��against campus-cultism���that is the violent often male co-fraternities��organization that have a toxic presence on university campuses (not entirely unlike American frat culture). After being beaten��by cultists��and arrested on several occasions,��Sowore��relocated to the United States, where he now lectures��in��Modern African History at the City University of New York and Post-Colonial African History at the School of Art, New York. He also started an investigative media outlet known as Sahara Reporters, which has become popular in Nigeria for exposing corruption cases, and has turned��Sowore��into a respected opposition figure.��What��Sowore��still lacks is a national organizational structure which can turn his fandom into votes in neighborhoods��polling stations��across the country.

In Nigeria, only the APC and the PDP can��boast��of such nation-wide organizational density.��In the 2019 election,��both main parties��campaigned on center-right populist platforms, mobilizing based on ethnic nationalisms and on slightly differing versions of neo-liberal governance. This ideological fusion has dominated Nigeria���s electoral politics since the start of its Fourth Democratic Republic in 1999. In 2015, the APC, on a platform of ���change���, became the first victorious opposition party in Nigeria���s history when its candidate, retired General Muhammadu Buhari, defeated incumbent president��Goodluck��Jonathan. However, Buhari ���change��� looked very similar to the economic strategy and political message during the previous 16 years of PDP rule.

In fact,��as I argue in my thesis, this��remarkable ideological��convergence��between both major parties has been misidentified by many analysts to suggest the��absence��of ideology in Nigerian politics. Part of the reason for this miscalculation lies in the fact that African politics, even in Africa���s new democracies, is still generally understood through the prisms of primal tribal ties,��or patronage links, a stereotype which Africa-focused social scientists have termed ���neo-patrimonialism.���

This stereotype appears to be affirmed each election cycle when we hear of clashes between rival party supporters, and of election results triggering bouts of communal violence, as occurred after the 2011 election when as many as 800 people were killed in election related violence.

The current election cycle also witnessed both pre-election and election day casualties recorded across Nigeria���s turbulent middle-belt states and oil-producing Niger-Delta. This electoral cycle has been more peaceful that recent ones, with the fact that both Buhari and Atiku are northern Muslims reducing the religious and regional tensions that have characterized previous presidential polls. However, localized violence was witnessed in the key battleground states of Lagos, Rivers, Bayelsa, Delta, Enugu, Anambra,��Nasarawa��and��Kogi��states. By mobilizing tensions��across the length of��Nigerian society, its two main parties have once again managed to retain control of the Presidency and of the majority of National Assembly (parliamentary) seats.

Without a national wide organizational structure that extends down to the neighborhood level,��Sowore��was ultimately unable to meaningfully confront the main parties of government.����However, despite his failure to unseat the two hegemons,��Sowore���s��seventh place performance ��� particularly in a crowded field of over seventy political parties���is nonetheless the best electoral performance Nigeria���s fledgling anti-capitalist fringe has achieved since Nigeria returned to democracy in 1999.

For Nigeria���s political left, the past two decades have been marked by retreat. The Nigerian Labor Congress (NLC), the umbrella body for national unions, has faced a crisis of legitimacy, typified by the NLC���s ultimate capitulation to the Jonathan government���s new petroleum price during the 2012 #OccupyNigeria��protests against the removal of a fuel subsidy. The intellectual and artistic left have largely lost contact with each other, an unfortunate departure from the scene in the 1970s, back when��Fela��Kuti��and his full band used to play at Marxist conferences, hosted by students, academics, and public intellectuals.

Electorally, the absence of the left has created a political void which the main political parties, the APC and the PDP have happily filled. Feelings of marginalization and exclusion held by rural and working-class citizens have been mobilized by demagogues through populist organizations fueled by ethno-nationalist sentiments.��It is a story that resonates with that of Brexit and of the victory of Donald Trump, though the ���arrival��� of a politically viable right-wing populist movement is often narrated from a Eurocentric perspective, failing to notice the long-standing dominance of such movements elsewhere in the world, particularly in Africa. Rather than thought of as exotic, Nigeria���s democracy is best understood through this same ideological frame. Moreover, to do so would only be to access Nigeria���s two main candidates by their own standards; Atiku Abubaker, the PDP candidate and the more articulate of the two, recently described himself as a centrist as well as a ���big fan��� of Margaret Thatcher���s privatization drive.

Shortly after Buhari���s victory was declared, the opposition PDP announced that it had rejected the ���sham��� results and would challenge them in court. Though election management has often been fraudulent in Nigeria, it is clear that��Buhari���s��slightly more mass-oriented policies was part��of what won him support overwhelming amongst the��talakawa, the largely Muslim��northern-Nigerian working masses who are also Nigeria���s most populous voting-block. Ultimately this constituency proved to be more decisive than did Atiku middle-class southern supporters for whom the privatization of state industries is a sensible idea.

Thus, a major contribution of this election has been to both shed a light on the dominance of the two��centrists��parties and to awaken a measure of class consciousness in Nigeria, if one that is also clocked in ethno-regional identities. The election and the mixed success of��Sowore��have also provided the fledgling left with a useful reminder of the harsh realities of electoral politics without being devastating enough to crush its spirit.

Given the relatively moribund state of the Nigerian left���with the exception of a few recent��stirrings���Sowore���s��national media recognition, as well as the fact that he was amongst the top-ten candidates, is a milestone in the development of a radical electoral alternative. What remains to be seen is what direction this momentum will have taken by the end of Nigeria���s new electoral cycle.

March 17, 2019

Algeria’s bloodless coup

Image credit Farah Souames.

Veteran Algerian��human rights��lawyer Abdennour Ali Yahia once said: ���[Abdelaziz] Bouteflika doesn���t want to be Le Pouvoir, but rather the political system as was the case for Houari Boumediene, or Fidel Castro in Cuba. He wants to lead everyone, the army included. This is the fundamental problem.���

Boumediene governed Algeria from 1965 until his death in 1978. Ben Bella was the first President of Algeria from 1962, at independence, until he was overthrown by Boumediene.

Boumediene���s critics labeled him a dictator (he ruled via a Revolutionary Council made up of military men until 1976), but they never denied his presidential charisma and revolutionary vision. He maintained what resembled a social and economic balance though his presidency. His regime, however, was undone by the country���s dependence on oil revenues and stagnation in the rest of the economy.

Bouteflika served in Boumediene���s government as minister of foreign affairs and was his expected successor. Bouteflika only became president twenty years later when the country was struggling with a horrific civil war.

The backdrop to almost any analysis of Algerian politics, is recognition of the army���s ability to manipulate the ruling elite. With the protests in Algeria continuing for the fourth weekend in a row, the message from the street now is a little different from the previous protests. While until now people chanted ���No-to-a-fifth-term,��� this time it was relevant since Bouteflika announced last week he was not running for a fifth term, but postponed elections indefinitely.)

In recent days, the protesters��� demands have taken a different turn (they’ve been out in the streets since March 12th): denouncing the entire system���opposition parties, parliamentarians, and army elites included. Protesters, while keeping their cool and intensifying humor and sarcasm, are reaching a point where they are articulating their demands for what they want to see happen next in a way they have not before. And far away from the mediatized protests, we have seen public forums in the form of neighborhood councils, students filling auditoriums across the country to have open debates among themselves and with their professors, and lawmakers striking impromptu meetings to discuss formulating somewhat of a roadmap for what���s next.

The government���s strategy to bide time until the president dies in power is becoming more and more difficult as more pressure is mounted by the popular movement.

It is reported that President Bouteflika is no longer the decision-maker, but his entourage is. Lawmakers have especially been angered by the confusing messages coming from El-Mouradia (the Presidency). For example, in the most recent letter attributed to Bouteflika, he states that he never intended on running for a fifth term. This is in direct conflict with the fact that he had two campaign managers and somehow was able to collect 6 million signatures and deposited his candidacy file by proxy. The legitimacy of Le Pouvoir is fading by the day and the recent nominations of Ramtane Lamamra and Lakhdhar Brahimi are not helping to convince the people that meaningful change is happening.

Anti-constitutionally yours

The legitimacy of the Bouteflika government had never been more punctured than when the country���s lawmakers (of all ranks) took to the street to protest and denounce the breaches to the constitution.

Article 102 of Algeria’s Constitutional Law, states that if an illness ���prevents a leader from governing the country, they must step down.���

It���s not the first time that this administration has grossly violated the constitution. A two-term limit on the presidency was lifted in 2008 to allow Bouteflika to��run for a third time, a fourth and a fifth time. The most recent one was when he formally submitted his candidacy by proxy on March 3rd.

But this was not the only fishy thing about his candidacy. The next day, the Constitutional Council deleted from its website the requirement that a candidate submit his application in person. A move that pushed lawyers and judges to protest in Algiers and across the country.

In an interview with French TV news station, Europe 1, shortly after his inauguration in 1999, Bouteflika said: ���I could have claimed power after Boumediene���s death, but in reality there was a bloodless coup d�����tat and the army imposed their candidate.���

If anything, this shows an inclination of Bouteflika to think that he is somewhat an heir of Boumediene and a natural fit for the presidency. His and his government���s legitimacy though has never been this low.

A family affair

Humor and sarcasm were once again the beats of the protests. ��Once again, Algerian protesters displayed their political wit, dark sense of humor, and geekiness on their protest slogans. One of the funniest signs was a meme using taglines of Marlboro advertising: ���You are in a bad shape (���Mal Barr�����), your system is seriously damaging our health.���

Yet, a unifying theme on many of the signs from across the country last Friday carried messages about the protests being ���a Family Affair.���

Most of the protest signs targeted France and the US. Some were chanting against French President Emmanuel Macron, who has called for a reasonable transition “Macron, go away��� or ���Macron be careful, you got 7 million Algerians in France.��� ��France has been very vocal when it came to mass demonstrations in Venezuela for instance but being as loquacious on Algeria is a different story. France���s stance is dominated by the fear of being on the wrong side of the history. Right now, any speech or action that resembles interference would only make things worse. As for the US, a protest signed read: ���Dear USA, there is no more oil left, leave unless you want olive oil.���

Protesters emphasized a clear message that no foreign intervention is being requested or welcomed. Lofty statements like those coming from the Elysees or other foreign governments in these defining moments of Algeria���s transition are not viewed to be useful by the Algerian people.

The street vs the newly appointed transition team

The government has designated a team to negotiate Algeria’s political future, which will be led by veteran UN diplomat Brahimi, an Algerian national who is best known for the failed peace talks in Syria. Brahimi was also an Arab League envoy and reportedly brokered the��Taif Agreement��ending the civil war in Lebanon). He has always been the go-to person when the government wanted to deny allegations looming over the president���s failing health.

The precursor and most immediate trigger to the most recent protests of March 15th was the day Bouteflika ���signed��� a decree creating the position of deputy Prime Minister. After appointing Interior Minister Noureddine Bedoui as the new Prime Minister, he named Ramtane Lamamra, his advisor for diplomatic affairs as the new Deputy Prime Minister.

All three men appeared last week on national radio and television to address the Algerian people and welcomed them to be part of the transition team. Their media appearances showed nothing but their total disconnection from 40 million people. They were unable to give clear and direct answers to questions asked by journalists, which exposed their poor misunderstanding of the people���s reality and demands. A colleague said sarcastically: ���What do you expect from them, they still use fax machines and make little use of their emails, while millennials are out there broadcasting the protests to the world. The gap is real and huge.���

It should be noted that shortly before resigning, former Prime Minister Ahmed Ouyahiahad, made a veiled threat against protesters: “But, I remember that in��Syria��it��[the anti-government protest] began��that way, too; with��roses.” Meanwhile, newly appointed Deputy Prime Minister Lamamra insisted that, “Syria and Libya made mistakes that we will not make.”��However, not even the softer tone coming both from politicians and the army is not enough to convince Algerians to end the protests.

For instance, when asked multiple times about the legitimacy of Bouteflika���s presidency after April 28th, Bedoui didn���t offer an answer but rather passed it on to Lamamra who denied the dismantling of the national assembly.

What���s next?

Developments are happening so fast, sometimes too fast to keep up with. The broad picture looks smooth yet very complex. On March 15th, some policemen marched with protesters, and local TV channels aired for the first time since February 22nd live from the protests scene. Print media is more daring now than it was a few weeks ago. On its cover page for March 16th, El Khabar���s (one of the leading newspapers in Algeria) wrote ���Don���t add a minute, Bouteflika.���

This level of open criticism of Bouteflika was unseen in mainstream media at the beginning of the protests. On Friday, March 15, the state-owned TV news channel aired anti-government chants during prime time. These shifts along with defections inside the government and the army could really lead to a positive change.

All eyes are now on the Algerian constitution and the civic movement. The government might resort to Article 107 of the Constitution and declare a state of emergency. This option looks almost impossible when one considers the huge civil wave. If declared, protests would have to be halted and the voicing openly of the peoples��� demands would be squashed. This would further delegitimize the government in the eyes of the people and might as well harden the position of the protesters.

Camp of the Saints

Image by Tony Webster. Flickr CC.

In mid-February 2019, U.S. president, Donald Trump, declared a national emergency to combat an immigration ���crisis��� and ���invasion��� that is not based in fact, but in deep-rooted fears about the end of white, Western civilization. That is: the president���s national emergency is about more than just placating an angry electorate. He is waging an ideological battle that is heavily scripted by 20th-century white nationalist thought.

It is this same script that that informed the ���Great Replacement��� manifesto of the New Zealand mosque terrorist, who killed at least forty-nine worshippers a month later. It is a script that European far-right politicians and intellectuals have increasingly enlisted to resist pressure from the EU to accept climate refugees and asylum seekers into their countries. Now would be a good time to shed some light on this script���a script that is so vile, so apocalyptic, so dehumanizing that it makes sense why more people haven���t done a deep dive.

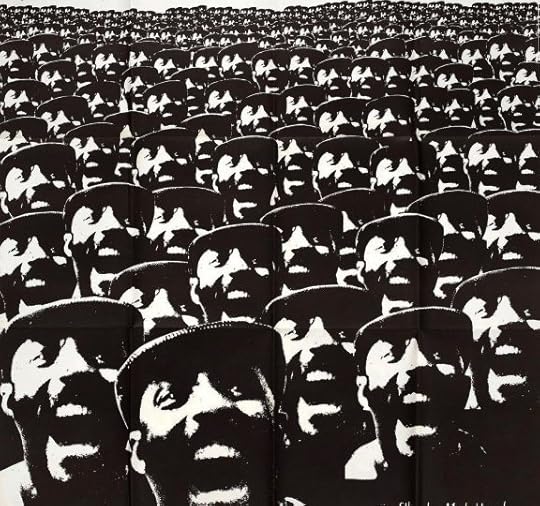

I mean more specifically The Camp of the Saints, a 1973 dystopian apocalyptic French novel about the crisis of immigration, the fear of ethnic replacement, and the invasion and end of the white West. I read this toxic book so that you don���t have to. And yet I think everyone should read it in order to uncover the fictional source code for the tropes, language, rhetoric, and style that invent the crises of invasion and replacement���and to uncover the very real consequences of (mis)taking these fictions as fact.

Imprinted into the Brain

Representative Steve King (Republican, Iowa), the US congressman recently relieved of his House committee assignments for asking���out loud���when white nationalism had become offensive language, has been on the crisis of invasion, great replacement anti-immigration train for years. He remarked in a 2018 interview with the far-right Austrian web publication Unzensuriert that the story of Jean Raspail���s The Camp of the Saints ���should be imprinted into everybody���s brain.��� King���s comment rang true for me, though for very different reasons. My experience of Raspail���s text was more like a toxin or a parasite: the text burrows into the psyche through its extremely effective use of rhetorical and figurative devices: anaphor, repetition, accumulation, alliteration, onomatopoeia, and imagery.

I assigned Raspail���s novel in a class I was teaching on far-right nationalism (Maurrassisme) and Catholicism in 20th-century France, part of an attempt at what I���ve come to think of as ���staring into the abyss������close reading, analysis, and evaluation of the far-right nationalist screed that informs not only present-day ideology, but our present-day political language. There is pedagogic value in tracing this textual and discursive heritage by actually reading the texts themselves, instead of just pointing to their existence. We come to know them and the power they hold for an emergent new far right that is hyper-nationalist, islamophobic, anti-EU, and for zero immigration.

Indeed, Raspail���s book has long been lauded by the far-right nationalist Le Pen dynasty in France (Marine Le Pen famously gives the book pride of place in her office), and has more recently surfaced in the US as a point of reference for the anti-immigration advisors and congressional allies that work with Trump.

Peter Maass at The Intercept pointed out a truly extreme Breitbart article (which is saying something) penned by erstwhile special assistant to Trump, Julia Hahn. In it, she accused Pope Francis of repeating the fictional folly of the pope character in Raspail���s book: treating impoverished migrants with humanity and dignity. No surprise, coming from a Bannon prot��g��. In his deep dive into Bannon���s intellectual and ideological roots, Josh Green described the former Breitbart chair���s worldview as: �����the whole world is falling apart, the country is going to hell, these dangerous immigrants and criminals are kinda marauding through our culture, and meanwhile the secular PC liberals are turning a blind eye to it and destroying American identity and so on and so forth.��� This is, predictably, the tl;dr version of The Camp of the Saints updated to a 21st-century U.S. context.

So the novel inspired Bannon. But what inspired the novel itself? Certainly some of the same early 20th-century far-right nationalist, fascist thinkers (Julius Evola and Charles Maurras, for starters). But Raspail���s text was also born out of the neo-Malthusian revival of the 1960s and 1970s, when demographers predicted exponential population growth from 3.7 billion to 7 billion by the year 2000. We would do well to revisit this historical context in order to better grasp the ideology and the zero-sum thinking that structure at least the current White House policy on immigration, if not the broader language, legislation, and action of the far-right leaders throughout the world. It is a script that is unfamiliar to most Americans, if we consider the sheer foreignness of the language, imagery, and references that scripted Trump���s ���American carnage��� inaugural speech. This script has come into focus as the administration has moved forward: in legislation, in presidential remarks, in news show appearances, in media talking points.

The Camp of the Saints

Jean Raspail is a nonagenarian French novelist whose prolific fifty-year oeuvre is part travel narrative and part fiction–rather like a conservative, Catholic, not-at-all-nouveau roman version of J.M.G. le Cl��zio. Raspail���s political and literary leanings share much with earlier French intellectuals like Paul Morand and Maurras, though comparisons to Camus, C��line, Rabelais and, more recently, Houellebecq and most certainly Renaud Camus and Eric Zemmour, are warranted. Raspail shares the fate of some of the above-listed authors who were denied entry into the French National Academy for their political views���he has been nominated for a seat as an ���immortel��� three times already and failed. He has nevertheless won a handful of small awards from the prestigious French literary academy.

Raspail published Le Camp des Saints in 1973 with ��ditions Robert Laffont, one of the bigger French publishing houses known for its popular (less ���high culture���) literary offerings. The novel���s publication coincided with a fundamental shift in French politics, culture and society, and the emergence of reactionary, new-nationalist thinking. Not incidentally, the early 1970s saw the founding of Jean-Marie Le Pen���s anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-EU National Front party (recently rebranded for maximum main-stream normalization as the ���National Rally��� or Rassemblement national party).

In its packaging���title, structure, epigraph���Le Camp des Saints is based on the Apocalypse of John in the Book of Revelation that prophesizes the arrival of apocalyptic hordes (Gog and Magog) who will gather in an assault against the holy city. In this, Raspail���s narrative is fairly straightforward: it tells the story of an armada of migrants from Southeast Asia arriving upon the shores of the French Riviera and sacking the unnamed coastal city by the novel���s end. The book���s rather uncomplicated premise allows Raspail to typify the main groups involved for symbolic effect: the French army; the Catholic Church; the French elite; the communist hippie youth; the nameless, faceless masses of North African and sub-Saharan immigrants that are already packed into cellars, attics, and twenty-mattress rooms in Paris; and the half-naked, only half-human hordes of migrants from the subcontinent that are set to arrive on the shores of the West.

Fair enough. Yet in spite of this symbolic framing, I would argue that the novel is primarily driven by real, concrete concern for���obsession, really���with those 1970s population growth models and more specifically, non-white population growth. In the short two-paragraph preface to the first French edition, Raspail states in no uncertain terms that his text is to be taken literally and not symbolically. That is, in spite of the biblical allusions, the symbolism, and the prophetic narrative mode that he adopts, he purports to write the novel with authentic ripped-from-the-headlines news stories, presidential speeches, and faits divers. For Raspail, France���and the rest of the White West���is indeed headed for its Camp of the Saints moment: ���We need only glance at the awesome population figures predicted for the year 2000, i.e., twenty-eight years from now: seven billion people, only nine hundred million of whom will be white.���

Oof. It���s shocking to read the plainly-raced terms in which Raspail states his premise���one that has been rebranded, reframed, shined up, and sanded down but never really changed in the fifty odd years since his novel came out. It���s the premise of white supremacy, and the ontological threat that a growing non-white world population poses to it. Its unchecked, unabashed premise is that whiteness=Western civilization and non-whiteness=the end of that civilization.

In Raspail���s fictional world, all non-Western, non-white immigrants exist as pathetic, sub-human, nameless, faceless hordes. Indeed, he often describes them as bare, naked flesh; disembodied parts with no identity, no face, no soul. The desired effect of this rhetorical and stylistic conceit cannot be overstated: in order for Raspail to create the effect of the onslaught of the horde, of the swarming mass, to evoke fear, there can be no individual description or discrete identity within the group. Raspail describes the migrants coming ashore: ���like an anthill slashed open [���] Endless cascade of human flesh ��[���] Surging blindly forward. Unthinking, unwitting.��� The horde���the plague���is unmistakable here; the migrants are insects, swarming in an infestation, acting as one without actually thinking, deciding. The text itself is a virtual assault on the reader; we are trapped, subsumed by the onslaught of adjectives and descriptions. His language itself is an infestation, submerging the reader and, in many ways, overwhelming her.

So Raspail successfully creates the effect of the infestation through his stylistic and rhetorical devices. But people read this stuff and believe it? Even if we set aside the white supremacy disclaimer he loudly announces in his preface (and we definitely shouldn���t), we would also have to acquiesce to the assumption that structures Raspail���s entire gambit: that not a single one of the millions of migrants that stream ashore in The Camp of the Saints can be treated with an ounce of humanity. Raspail may know that they are human beings, but that is not the point. The point is that, to survive the fictional, sensationalized, entirely unrealistic onslaught, the West has to decide to dehumanize the non-Western, non-White other. This is crazy. And yet, it makes everything else that we���ve seen out of the Trump administration in the last three years make so much more sense: it���s based on the zero-sum idea of the survival of (White, Western) humanity that Raspail���s novel is constructed to conjure up, and to make seem and feel real.

In subsequent writing about the book, Raspail further elaborates this aspect of his worldview, explaining the importance of The Camp of the Saints by rooting it in a series of either/or propositions. In the 1982 Afterword, Raspail presents the problem of the Global South and the migrant crisis as one that is ���absolutely insoluble by our present moral standards. To let them in would destroy us. To reject them would destroy them.��� The vague ���present moral standards��� that Raspail evokes here should be understood to mean Enlightenment liberalism, and more specifically, humanism, universal equality, and human rights. He laments the ���Western conscience��� as having been besieged by ���the slow, cancerous progress of compassion, which is only a misleading and lethal form of charity.��� Westerners must accept that ���rejecting them��� is a necessary condition for the survival of the West. His novel is designed to prove that ���the denial of essential basic human differences would work solely to the detriment of our own integrity,��� and so the West must act according to basic human difference between races, maintaining some apartheid-style wall building or, if necessary, destroying the Other.

The degree to which Raspail, a Catholic, criticizes Catholic social teaching in the novel is particularly noteworthy here: he assails the fictional pope and the line the Vatican takes in favor of the migrants, and shows a group of Benedictine Monks committed to welcoming the migrants get trampled in seconds by the migrant onslaught in the novel���s denouement. Indeed, Raspail seems to take aim precisely at the social justice Catechism of the Catholic Church: that of the transcendent dignity of humankind, that one must fight against sinful inequalities in the name of social justice, equity, and human dignity. These, too, are the ���present moral standards��� that Raspail argues must be done away with. Again, for Raspail this is zero-sum: ���we are facing a unique alternative: either learn the resigned courage of being poor or find again the inflexible courage to be rich. In both cases, so-called Christian charity will prove itself powerless.��� ��It is perhaps this last sentence, penned in a new 1985 Introduction, that resonated most with a certain kind of U.S. readership that would come to see in Raspail���s novel a useful tool and a prophetic touchstone.

The Camp of the Saints in the US

���Years ago a book, ���The Camp of the Saints��� came into my hands.��� This is how Steve King explains how he became familiar with Raspail���s novel. It���s a convenient phrasing���passive voice, no indication of when, who gave it to him, or in what circumstances. This phrasing also maintains the cult-like status of the book, passed around among like-minded adherents.

In fact, the book came to the U.S. via Scribner���s���the well-respected publisher of works by major US writers from Hemingway to Stephen King���which published the first translation in 1975, just two years after it appeared in France. The edition included no other introductions or prefaces, though the dust jacket notes that the novel is ���already a sensation in Europe��� and that ���no one will forget it or remain unaffected by the questions it raises about the future of the world.��� Scribner was thus plugged into the same zeitgeist of population projections and dystopian future worlds of the 1970s.

(Small side note: Scribner commissioned Norman Shapiro���a well-known translator of scores of French-language literary works then quite early in his career���to translate. Shapiro is rather notorious in the field of Francophone Studies for writing translator prefaces that denigrate the Francophone poetry he���s tasked with translating as ���derivative��� or subliterary, as he recently did with the poetry of Haitian independence).

Scribner only printed one hardbound edition of the novel, though Shapiro���s translation was used in each subsequent U.S. edition. What is clear from these different publishers is that Raspail had found in the U.S. a special interest anti-immigration audience early on: the Institute for Western Values, Inc. (1982), the American Immigration Control Foundation (1987), and the Social Contract Press (1995) each published U.S. editions of the book. Notable for its status as a Southern Poverty Law Center-designated hate group, The Social Contract Press leaned heavily on Raspail���s status as a ���prophet��� in lauding the book for its prescient depiction of an invasion of immigrant hordes. The novel has found an important anti-immigration audience outside of the U.S. as well. Literary critic Jean-Marc Moura has noted translations in Spain (Plaza y Jan��s 1975), Portugal (Publi��oes Europa-America 1977), and London (Sphere Books 1977). Moura argues that the publishing history of Raspail���s book is not purely based on literary or commercial interests, but rather ideology, and that the book itself is not received by its readership as a simply literary fantasy (as it was first marketed by Laffont and Scribner���s).

All of this to say, the novel did not just fall into the hands of Steve King; a network of special interest non-profit organizations worked hard to make sure it got into the hands of people like King. And, in the advent of internet hate, it has been discussed at length on Occidental Dissent, Daily Stormer, Breitbart, Reddit, and probably all sorts of other corners of the internet.

The Script

Donald Trump���s dislike for the written word has been a feature of his presidency from the start, and a near-constant theme in news coverage of it. This fixation on the president���s predilections for TV screens and phone calls tends to mask the highly textual nature of Trumpism, and the script that informs it. Indeed, many of his aides and advisors love to read, but what they���re reading is a body of work that most educated Americans are entirely illiterate in.

The novel is not a prophesy, nor is Raspail a prophet. It is a discursive and cultural script that includes a ���deeply predictable��� trope that Dara Lind has called, in shorthand, IACATBTKY (Immigrants Are Coming Across The Border To Kill You). To be sure, it is not a script in the sense that Trump or his aides are thumbing through an old dog-eared copy of the book. Rather, Trumpism is based on set of images, comparisons, and tropes that are part of Raspail���s dystopian, terrifying worldview that sees the end of the White West as nigh. In this scenario, the question of humanity is entirely self-referential. It���s not about recognizing the fundamental humanity of all beings in the world, but about White Westerners seeing their own human existence as under threat. Their humanity thus becomes contingent upon whether they choose to ���break��� with the moral principles of human rights and fundamental human equality���whether they choose to see the Other as a threat upon whom the most inhumane treatment should be visited.

Whether or not Trump���s national emergency is blocked by Congress or the courts, as it is likely to be, there is now no mistaking the scripted nature of the crisis. Its actors are unmoored from the basic principles of human rights. What real emergencies they might create within their own nation and in others���we do not need a fictional apocalyptic tale to predict.

March 16, 2019

Namaste India

Image credit Riccardo Romano via Flickr (CC).

Remember me,��right?

I came to visit your home at your humble request. I am very good friends with your son/daughter. I came over and you served me chai and namkeen. Then you asked me to visit you more often.

You see, I go to college with your son/daughter. We are very good friends. We help each other with class work and assignments and we even go shopping together. Your children have shown me the best markets in the city and we have taken a thousand photos together.

You know me.

You know me from the metro. Where you have taken selfies within my range so that you can show your friends and relatives that you spotted a foreigner today. You have asked to take random pictures with me in public and very often I have smiled for the camera.

You know me.

You know me from your��dhabas��and your shops. I come to buy milk and bread every morning. I often chat with you about the weather before picking up my grocery bag and heading home,��where I have sometimes given young Indians the opportunity to clean my house or iron my clothes for a fee that will help feed their kids.

You know me.

You know me from when you draped my saree for me from your home; That time it was your cousin brother’s marriage in a far-off place.

Your daughter and I have wiped each other���s tears and danced together in the rain. We have figured out that even though we are from different places, we can still work together. I learn from them and they learn from me.

Sometimes I���ve been asked why my skin is dark. ���Is��it because Africa is very hot?�����And I’ve often answered that India is hotter than Africa and that my skin is darker because God gave me more melanin than you.

You know me.

Well at least I thought you all did; enough to know that I do not and��can not��and will never eat a fellow human being.

You know me.

I am not a cannibal.

Image credit GNLogic via Flickr (CC).

Image credit GNLogic via Flickr (CC).My parents sent me to India to study. At home, I have a sister and brothers waiting for me to come back with a degree. My parents are constantly worried about my wellbeing. Shouldn’t they?

And today there���s news that people of my race are being attacked for no reason at all. What if I were your beautiful Sunita, or your beloved Rohit? What would you do if you heard they were missing or being beaten up by a mob in an African mall just because they are brown in color?

Every race has a stereotype towards another. We often tend to judge that which we do not understand; that which we could never be. But just because my skin is packed with melanin or I have locks in my hair does not mean I do not have the same feelings as you. Does not mean I deserve to be beaten up to near death for a crime I never committed.

There are millions of Indians living in Africa. I do not think they are being treated this way. Help stop the hate!

I have parents waiting to meet me alive at the airport��some day. Please help me be safe. Help my friends remain safe here until we go back home. Help spread the truth. Help stop the hate and discrimination.

Aunty, Uncle, you know me. Help me.

Shukriya

March 15, 2019

Sarkodie and the politics for ‘freedom-making’

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.

Sarkodie is��arguably��one of the most successful��Ghanaian musicians��of his generation.��Employing��braggadocio,��Sarkodie��displays his musical and economic success in his��self-fashioning,��songs and��music��videos.��He has won numerous awards both��locally, on the��continent and��internationally.��In 2017, he was ranked number 9 in Forbes��� list of��the��top 10 most bankable African artists because of his brand value, endorsements, social media presence, earnings, bookings and popularity.����But��it is��how his��astute entrepreneurial sense��aligns��with the��state���s��imperatives to produce��entrepreneurial��citizens,��which��makes him such an important cultural-political figure in Ghana and beyond.

Sarkodie has become a model, particularly for young men,��for��how to successfully navigate socio-economic��terrains��to attain economic well-being.��He even��proffers��investment��advice,��cautioning��them��against��frivolous lifestyles��such as conspicuous consumption,��as well as encouraging them to��invest in their��future��financial security.��(In this, he parrots his role model Jay Z.)

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.Recently���in a series of tweets��in December, 2018���Sarkodie��broadly touched on��unequal global media exchange,��black inferiority,��youth agency��and African liberation.��He then��appeared to��offer��one��solution to��all these ills:��He tweeted,�����What we need at this point might seem like dictatorship and will feel uncomfortable since we have enjoyed temporal freedom for a minute but we need drastic measures to survive.���

This may appear ironic coming from somebody whose profession is built on the freedom of speech that many Ghanaians��risked their��lives and safety to secure. Yet, this sentiment is not uncommon amongst various segments of Ghana���s��population,��especially��among��young folks. Just listen to��the��radio in��Accra��and you��will��hear��people claiming Ghanaians are��undisciplined,��and��that��we need a�����strongman�����(it’s always gendered that way too)��to��discipline��us.��At times,��some folks��have��suggested that Nkrumah rushed independence and perhaps under British��colonialism��we could have become��a developed nation.��Generally, these sentiments echo racist colonial ideas about��how��Africans are��incapable��of handling their��own��affairs.��These ideas blame all the country���s problems on its internal happenings.

But��these��problematic ideas��also��express��several��complex��sentiments��among��Ghanaians.��Within these ideas are incomplete answers to why Ghana���s independence and democracy have not led to the promises of development.��Since��the return of democracy in��1992,��the two major political parties,��the��National Democratic Congress (NDC) and New Patriotic Party (NPP),��have��simply��captured the��state.��Ideologically,��both parties��uphold��the neoliberal assumptions��about��private��sector led development.��The consequences of this captured��duopolistic��liberal��democracy��have��been��an��ever-diminishing��set of possibilities��for many young people.��And��this has engendered��a��creeping��fatalism,��which��appears to reinforce the idea that things will forever remain the same.

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.In 2016,��according to the��World��Bank,��youth��(between 15-24)��unemployment��in Ghana��stood at��48 per cent. For many young people, democracy under this two-party system��has��failed to improve their conditions. They are caught in what��Alcinda��Honwana��calls�����waithood,�����which��she describes as��the ���prolonged period of suspension between childhood and adulthood.�����Increasingly, it has become difficult for��young Ghanaians��to acquire markers of adulthood. For instance, moving out of their parents��� home is an expensive endeavor��as��potential tenants are��required to��cough up 2��to��5 years rent advance. In addition, for many young people��it feels like��their voices do not matter. Recently, this was evident��during��the��students��protests in��the Kwame��Nkrumah��University��of��Science��and��Technology.��Afiba��Harrison, a student, offered the most insightful��analysis��on��the��matter:�����We’ve shifted focus from that fact that in this country the system does not allow for discourse. What the system …��listens to is violence�������In the 21st century, if students had to resort to violence to actually get the authorities’ attention, the whole nation’s attention, the media, you and everybody else talking about this issue, then there is a problem. The problem is not about the students. The problem is the system.”

Strikingly,��this latest youth uprising��was not enough to��push a national conversation on youth and��gerontocracy. No national forum was organized to listen to the concerns of young people. After the protests were milked for their news value��by the media, the unhearing returned.

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.As such, folks like��Sarkodie, now empowered��by��turning��their��musical talent into economic success have��become��prominent��voices��in an urbanity that unhears its��youth. The platform he commands allows him to echo the imperatives of the society��while presumably��challenging��the status quo.��In fact,��by��merely being a��successful creative artist��he has become a��successful��model to young folks. His��commercialized��aesthetic��reveals aspirations to live the good life, like most economically oppressed young Ghanaians. Yet, Sarkodie offers liberation through a narrow notion of securing��male��economic well-being,��mostly��at the individual level.��In his song�����Black��Excellence�����he substitutes��Steve��Jobs��and Warren buffet��for Martin Luther King��Jr.,��conflating the struggle to attain material wealth with the struggle to attain freedom and��dignity��against��patriarchal��capitalist exploitation.��(Moshood��had an excellent analysis of the anti-black ideas within the song, on Africa is a Country.)

Yet, like��Sarkodie,��hiplife��has come to represent possibility, often for young men.��It���s agentic affordances are gendered, women in this male dominated��genre��are often unable to thrive because hiplife refuses to recognize their talent and insists��that their success is tied to their bodies��and commodified performances of hypersexuality.��Nonetheless, the possibilities reside in the��relative��creative freedom��it offers young folks��to explore their histories, lived experiences and bodies. It��has made legible the strategies to��recuperate/recreate��narratives of freedom that place the ���wretched of the Earth��� at the center.��It is here that young folks can��produce vocabularies that��imagine��and construct worlds that enable all to thrive.

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.

Image credit Nii��Kotei��Nikoi.*I first heard the phrase ���freedom making��� from Dr.��Sionne��Neely in Accra during conversations at Accra [dot] Alt about art making in Ghana.

Bittersweet Swazi sugar

Due to potential security threats,��the��writer��has asked to stay anonymous��and the names of farmers have been changed.

���My heart was pained again because they grew sugar cane on top of my��first born��son’s grave��� we found bones of our dead in the open,��� says 50-year-old Carol as she sits in her dusty make-shift hut in��Simunye, in [what part of] Swaziland. A combination of red mud, branches and whatever she can scavenge to hold it all together, her house still looks too weak to protect her against the brutal winter winds that slice through the��Lebombo Mountain Range.

To anyone visiting this isolated community of once prosperous farmers, this starkness may seem strange after driving through endless fields of lush sugar cane marked with the insignia of the King���s Royal Swaziland Sugar Corporation (RSSC). Carol���s community was among the first of various rural communities in the region forcibly relocated from their homelands in the 1970s to make way for sugar cane production, the crop that has become known as��“the hunger crop”��because of the poverty left in its wake among��evicted communities.

As we visit Carol, meanwhile,��on the other side of the country, King��Mswati��III���with an entourage of selected wives and a bevy of royal hands���boards��his recently refurbished��A340-300���Airbus purchased for��US$30 million. He is on his way to New York for his annual address to the United Nations General Assembly, but is reportedly flying a few days earlier to squeeze in some shopping and business.

That Swaziland is also home to some of the biggest multinational companies in the region, which makes a killing off of cosy relationships with a regime notorious for paying little heed to human or property rights (by Western or even traditional definition)���a kingdom described by a local critic as a bizarre place of ���traditional leather sandals and BMWs������goes unnoticed by most.

Swaziland was colonized by��Britain, and the former Empire���s��financial interests in the country go back long before they granted Swaziland independence in 1968. Britain built��strong relationships with the current King���s father,��Sobhuza��II. This was no different for various multinational companies who saw great opportunities in the natural resource-rich Kingdom decades back, largely underexploited by traditional structures in the country.

For regular poverty-stricken Swazis like Carol who got caught up in the political and business ambitions of the Royal family and multinationals, there would be no respite. Her story is a common one in the many isolated rural areas of the region and just a precursor for further evictions that took place in a community not far away ��� again, to the benefit of the King.

Swaziland attracts foreigners for its natural beauty, towns and villages nestled between endless rolling hills and mountains,��as well as some of its cultural spectacles. The Reed Dance ceremony���where��as many as��up to��40,000 young Swazi maidens cut reeds in front of the king��and Queen Mother��as a rite of passage to womanhood���attracts tens of thousands of��international��tourists every year. During the ritual,��the king may, should he so choose, pick a bride to join his 15 current wives.��This spectacle is an easy sell��for��Swazi tourism��as an opportunity for foreigners to see one�����of the biggest and most spectacular cultural events in Africa.���

A successful post-colonial experiment goes awry

With independence, the fertile kingdom was open for (new) business. The British government, which,��at the time, had major interests in agricultural projects across commonwealth countries, guided the process through its international finance development institution, the��Commonwealth Development Corporation��(CDC).

With Swaziland���s eastern��lowveld��region having an exceptionally high-yield per hectare of sugar cane (currently 9th��internationally), the CDC embarked on an ambitious pilot project of relocating a group of the country���s most experienced farmers to a piece of CDC-owned land called Farm 860 in an area called��Vuvulane��close to the Mozambican border.

This fertile land���collectively known as the Vuvulane Irrigated Farms project���would become the new home to approximately 265 farmers (and their families totaling over 3000 people) who would gradually move there��from all over the country��through the 60s and early 70s to learn from the British how to become smallholder sugarcane farmers and businessmen. Each farmer was allocated approximately 14 acres of land on which they could grow sugar cane as well vegetables and other crops with which to sustain their families.

���My first time here was on 16 October 1972���that was the day I was allocated land. I was brought to Vuvulane by the whites. It went very well and we were better off in those years��� I had my first car in 1974. We worked well and it was profitable,��� says Msolwa Dlamini, one of the original group of farmers who came to Vuvulane. In a country where��almost��75% of the population survived (and still does)��on subsistence farming,��this created a steep learning curve but they prevailed and times ���were good.���

As evidenced in interviews with��eight��of the farmers and their families and various documents and contracts��that I��reviewed, the deal was that the farmers would lease their patch of land from the CDC for approximately 20 years after which they would be given freehold title���making them landowners.

���[They said]��after 20 years we will give you your portion of land because you no longer have land where you came from,�����said��Mpisi Dlamini,��one of the elders leading the farming community who also moved to the scheme in the 60s.

After the lease period had expired, many successful harvests had come and gone. Their children had become adults and learned the family business of smallholder sugar farming. The CDC then resurfaced after speaking to the father of the current King.�������In 1981, the whites made a decision to give us the land�����We heard the decision to cede the land from the King [Sobhuza II]. The King said the whites had decided to give us the whole land,�����said��Msolwa.

It was soon after this that Swaziland went through a time of political flux following the unexpected death of Sobhuza II, which saw power changing hands and a new Queen Regent, Ntfombi (mother to Mswati III), assuming power and, according to the farmers, took advantage of the profit potential of the Vuvulane scheme. Ntfombi���s son was crowned as King Mswati III in 1986.�����On its exit in 1983, [the] CDC handed over the farm to the resettled farmers [but] King Sobhuza was not present�������he passed on in 1982,��� says farmer Allen Mango.��

The Vuvulane scheme had already gained recognition in international development circles. As one of Oxfam���s staff in the 70s noted (from a memo their archives), ���this is beyond a doubt the finest settlement scheme I have seen anywhere.��� But an allegedly opportunistic move by the Queen would eventually spell the beginning of the end of the community���s success story.

In 1998, as a precursor to the privatization of the CDC in��1999, the development company allegedly signed over the farmers��� lands to the King, instead of returning it to the farmers as originally promised. Prior to this, due to mounting questions over land ownership in Vuvulane and surrounding areas King��Mswati III��commissioned a secret report by a committee, or��Libandla, of his closest advisors in 1995. This report���now leaked to the Swaziland Justice Forum���indeed reconfirms the rights of the farmers to the land following the 20 year lease period with the CDC.��But as a final recommendation and conclusion to the King, the commission noted that it was ���unSwazi��� for the farmers to own land and��suggested it would give them too much power��in��the��future.

���If [the] CDC had given the land to the farmers directly we would not be where we are today���there was no compensation. We were never compensated,��� says Cabangembili Mamba.

Farmers evicted

Just before sunset on the morning of 6 February 2016, the absolute darkness of rural night was ignited by an all too familiar sight in the area���police van flood-lights and blue lights crawling up the gravel farm roads. The RSSC���s threats of eviction had finally become a reality.

���They [the police] started with Mpisi Dlamini.��They bundled him into a police car��� shoved him like a hard core criminal in full sight of his little children. It was a great pity. They drove off with them leaving their earthly possessions,��� said��Cabangembili,��who witnessed the evictions.

The family were dumped by the trucks over 300 km south of Vuvulane on a drought stricken stretch of dust known as Lavumisa on South Africa���s border.��

There is no legal recourse the farmers can take due to the country���s compromised judiciary. ���There is a law that says when you move someone��� when you evict someone you should compensate him. They are not compensating us, they just take you and throw you in the open regardless whether you have children,��� said��a grey and weary Mpisi while fighting back tears.��

Many of the interviews with the��33 evicted farmers (and their 293 dependents)��were conducted in the bush alongside the highway in a barren patch of forest between makeshift huts like Carol���s in neighboring Simunye. The squatter camp is less than affectionately called ���Baghdad��� by locals due to its starkness and isolation, contrasted with the lush, green, fertile lands they���d been evicted from. With a correlation of satellite images of the area and plot numbers of the farmers evicted by the RSSC, it is clear to see the move to expand the company���s reach in the area at the expense of the farmers.

Evicted farmer *John, says: ���we are under slavery here���it is slavery. I say this because since [I���ve been here from] 12 August 1963,��I have nothing to show for it. There is no hope for the future to take care for my family��� these clothes [he takes his jacket off] are all I have, nothing more. What���s the point of living?���

A generation of farmers trapped in perdition

Leading the charge publicly for the evicted farmers is the��Swaziland Justice Forum (SJF), a small group of dedicated activists and academics representing the farmers and their plight to get their land back. The forum has run a social media campaign which has garnered a fair amount of public interest and concern around the evictions on both sides of the border. In their press release the forum accuses the��Tibiyo Taka Ngwane sovereign wealth fund and the��Royal Swaziland Sugar Corporation��of ���being behind illegal and reportedly violent evictions of smallholder sugar cane growers in that country.�����

���Over the years the farmers have made exhaustive appeals (legal and traditional) to the King, the Queen Mother, the Royal Advisors and the Prime Minister to no avail. The farmers are convinced that despite compelling evidence in their favor, coupled with the fact that they have occupied the land for over 54 years as promised to them by the CDC (and confirmed in official documents) justice would never be achievable through the compromised Swazi Justice system as the king is above the law,��� says the SJF.

The King���s personal wealth��was��estimated by Forbes at around $200 million in 2017.�� Following the fairly benevolent rule of his father, Sobhuza II, Mswati III made hasty moves within the lucrative sugar industry by purchasing the majority shares of the RSSC through��Tibiyo TakaNgwane���the faceless, unregistered “national development” fund critics have labeled his own personal ���ATM.���

Tibiyo���s present total worth��was��estimated at around USD 2 billion by a 2013��Freedom House report, and the fund supports Mswati, his 15 wives and scores of children.��As is the tradition in Swaziland with any Royally connected entity, Tibiyo is entirely immune to taxation, civil suits and criminal prosecution. The SJF and other critics are challenging the notion that an entity that doesn���t legally exist but for the benefit of the Royal family, should own 53% of the largest company in the country.

The RSSC made Tibiyo almost $10 Million in profits last year as reported in the company���s 2018 annual report. While this may seem a small amount, it is hugely significant in a country with a population of 1.2 million, 65% of which live in abject poverty. The evicted farmers feel helpless to challenge the��RSSC which Mpisi says is effectively the same as the King.

���The RSSC��is��the royal family and it is another one that cannot be taken to court easily because it is also one with Tibiyo��� and Tibiyo cannot be prosecuted. RSSC is the one that is really oppressing these Swazi people, it is the one taking the wealth,��� says Mpisi.��

In various public��statements��released by the RSSC responding to the SJF���s allegations, they ���state categorically that we [the RSSC] are not aware and have absolutely no involvement in any alleged evictions. We do not own any land in Vuvulane and therefore we do not have any basis to evict anyone.��� The forum has responded publicly refuting the denials and presenting a court issued ejection order from ���portion 28 of [Vuvulane] farm 860��� sealing the fates of Vuvulane farmer leaders Dlamini and Mamba, dating back to 2014 with the RSSC clearly listed as applicants for the order.

The company also has an interesting list of shareholders that the SJF assert are complicit in the evictions. At the time of the evictions in 2016,��Coca-Cola Export Corporation��owned a��1.8% share of the company. Coca-Cola Swaziland���s managing director, Manqoba Khumalo, also sat on the RSSC���s board.��Coca-Cola��has a long history with the kingdom dating back to Apartheid and runs a huge domestic factory under the name��Conco��(Coke concentrate) that supplies over 22 countries across Africa with the concentrate that goes into coke products, and��reportedly��enjoys��a 6% tax rate as opposed to the standard 27.5% rate other Swazi companies pay. Khumalo has also recently been elected to Swaziland���s senate���a prestige critics say just further illustrates the cronyism evident within the kingdom. Coca-Cola Swaziland has yet to��publicly��comment on the issue.

The RSSC���s other major shareholder is South Africa based��RCL Foods which has a 29.1% shareholding and whose parent company��(The Rembrandt Group) also owns international luxury brands (under their��Richemont��division) including��Cartier, Dunhill, IWC watches, Jaeger-lecoultre, Montblanc��and��Chloe. The group���s owner is South Africa’s richest and one it���s most divisive men,��Johann Rupert. Naturally, RCL Foods has denied that the company was complicit in any human rights violations in Swaziland passing the buck on to the RSSC saying�����they have responded with an assurance from [the sugar corporation] that the allegations are untrue,�����according to����South African magazine��Farmer���s Weekly��report.

With over 4 million Swazis estimated living and working in South Africa, the cause is now being championed by various large trade unions including South Africa���s largest, the��Confederation Of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) who��recently visited��the farmers. COSATU alongside others have publicly demanded that the country���s largest retailers stocking Swazi sourced sugar launch an independent investigation into these allegations, including publicly listed stores��Woolworths��and��Pick ���n Pay��who both stock RCL���s product��Selati,��which is one of South Africa���s��biggest selling��brands of sugar. In response to questions put forward by��Farmer���s Weekly,��spokesperson for��Pick n Pay��said they were ���concerned about the allegations [made by the forum] and have put them to our supplier, RCL [Foods].���

Bittersweet hope, trepidation and multinationals

While the SJF���s investigation has yielded thousands of pages of documents���lease agreements dating back to the 60s, leaked reports, contracts, piles of court cases, eviction notices���the reality remains grim for these farmers and their families. They are still currently in legal perdition and have been reduced from once successful and prosperous smallholding farmers to squatters virtually overnight, says Vuvulane farmer Cabangembili.

Our fathers worked for this land. They worked for over 20 years for the British but today they are like squatters, they have no right to live���that has made us lose hope that there is anything the Swazi courts can do for us. There is no hope. The courts don���t respect the law… Swaziland courts are not neutral.

While the RSSC and Royal Family assert that the farmers are lying, the 2013 Freedom House��report��on Swaziland purports an even larger motive for evicting the farmers that transcends just financial gains from the sugar cane, and one that is echoed by various critics of the current regime. The greatest threat to Mswati III and his cronies is the prospect of a financially prosperous, politically independent Swazi middle-class that is not dependent on the state for anything, which would start a wave of public demands for democratic accountability that��could��lead to revolution. In a country where press freedom is non-existent, where dissenting journalists and human rights lawyers are jailed and a ban on opposition parties continues, it seems the King���s fear of independent minded citizens may stifle the country���s future potential even further.

Various international voices have started speaking out on the land crisis including��Amnesty International��in a recent��report��and International Lawyer and former UN Special Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights, Ben Emmerson:

Social justice is in real peril in Swaziland – the sugar farmers are people, are citizens not subjects. It is time to start naming the multi-nationals��who��are profiting from this land grab. The eviction of sugar farmers in Swaziland is a scandal that demands the urgent attention of the UN Human Rights Council. The King���s ransom deserves international condemnation.

Until then, the farmers struggle on, waiting for the next hammer to fall as other members of the community have received eviction notices from the RSSC, says evicted farmer Nicholas Mkhabela, sitting outside the high fences surrounding what was once his community.��

We have resigned to fate ��� everyone will go to heaven [and] everyone will be answerable for their deeds on earth���a King and any ordinary human being���we will all be equal ��� they have already killed us. We do not eat, we have no clothes���we used to work for ourselves.

March 14, 2019

Friday Black

[image error]

Aisha Pedro photographed by Ryan Christopher Van Williams via Flickr (CC).

When my��Nigerian-American��friends��and I��talk about what it means to be��black��in America, we talk about the ways in which we must ensure our��blackness is the right size, the right cut���a digestible version of our identity.��Our��nappy or dreadlocked��hair��might be��considered unprofessional��in one instance, and��a fashion trend��when somebody else does it;��our English��(Pidgin,��Ebonics, Creole)��deemed��sub-standard. We��are��somehow never��enough just the way we are.

Nana Kwame��Agyei-Brenyah���s��debut collection of short stories,��Friday Black,��wields the sharpest tools of the dystopian genre���wild metaphors, stark imagery, and boundary-pushing hyperbole���to grasp at the contours of blackness through the prisms of racism, capitalism, morality, and family with the incisiveness of a tailor informed yet untainted by what is in vogue. (Friday Black just won the 2019 Jean Stein Book Award from Pen America). The��author���s��imagination in this book is like a country where it rains knife-shaped ice, it chills the bones unexpectedly, yet it feels shockingly familiar.

The opening story������The Finkelstein 5������follows Emmanuel��Gyan, a black man, as he tries to negotiate his Blackness with an actual scale that enables him to as it were, dial up or down how black he will be in various situations. This is in a society where a white man can behead five children with a chainsaw in the name of self-defense, and not be found guilty in a court of law. He may dial down his blackness, to say a cool 2.0 when he is in a mall full of white people, or a higher number when among black people. As he grapples with the realities of how he is expected to wear his identity and what that implies, he evolves from a place of docile response to an eventual outburst that is neither shocking nor unfamiliar.

This absurd introduction sets the tone for the rest of the book.��Agyei-Brenyah��will not wait for us to get comfortable: it is not a welcome-to-my-house-please-take-a-seat baptism into race, morality, and other forms of invented American discomfort. In ���Zimmerland��� we meet Isaiah or ���Zay,��� who works in an amusement park of sorts that uses simulations of everyday encounters with stereotyped minorities as a way for (white) people to ���explore problem-solving, justice, and judgement.��� Why would a black man, choose to work in such a place? Does that make him a sellout? Black protesters (and at one point his girlfriend) seem to think so. He is trapped in a��sense. The compounded effect of being black in a racist and capitalist society means that he is at the highest risk of financial insecurity, and will take a job wherever he can get one. The dramatization of Isaiah���s dilemma, and ultimate decision to continue to work in a place where white people pay to shoot black people for entertainment, might be hyperbolic but it is not a shade too far from the everyday reality of how class, and money in a capitalist society (and the lack of it) distorts our attempts at racial solidarity and freedom.�� When I read “Your life is in the hands of someone who doesn’t even know you and thinks you don’t deserve it,” the shock isn’t new, only fresh, and��Murderpaint��� (a synthetic blood in��Zimmerland���s��simulation of white people shooting black people for sport) feels like a product I have actually heard of before.

���Lark Street�����tells the story of��a young man confronted by the physical manifestations of twins his girlfriend has aborted hours before,��bringing up��a��prickly debate��between��morality��and��practicality.�����He says Dad like the way some people say cunt,��� the narrator in ���Lark Street��� says of his aborted son,��Jackie Gunner.��Agyei-Brenyah���s��choice of��tackling��a subject��as polarizing as abortion,��with the��proverbic��blatancy and rhetoric characteristic of a��wizened��Ghanaian tongue��is fascinating;��although��he is a New Yorker,��Agyei-Brenyah��is also a first-generation American of Ghanaian descent.��The��touch of�����Ghanaianness”���through words and expression��that may otherwise be overlooked, whitewashed, or outright��omitted���is��an unusual triumph��and��is��greatly��appreciated��by readers like me (and��apparently��many on Twitter)��who do not often get to see such bits and pieces of our language in literature. The new syncretic images and language, a result of coalescing his multiple perspectives, is refreshing:��there is nothing more Ghanaian than��saying�����My arm is paining me,��� and nothing more American than complaining.

Perhaps none of the stories exhaust the abilities��of��dystopian fiction��and use absurdity as an instrument of torture to eke out the searing truth��quite like the story of Ben in ���The Era.��� The story��is one about a distant dystopian future where people are practically programmed to speak the truth and eschew lies. Ben, the story���s protagonist, finds himself trapped in this era where people, and he in particular, depend on injections in order to have some ���good��� in them, right up until the moment that he realizes that maybe, just maybe, there is a secret liberty to be found in coloring outside the lines.

���The Era�����is��written��like a dream, and the narrative reads like a dream. You can almost see yourself waking from a slumber having had this story as a��dream but instead of forgetting��you remember it,��it stays with you.��When you read a sentence like ���My head feels the way an orange tastes,��� it registers as absurd but there is something inexplicably au fait about it. We are forced to look at our reflection: a species invariably fallible amidst the engineered possibility of perfection, but also with capacity to rebel toward freedom.��In��this story,��the writer seems to suggest that whether humanity exists in the comfort of our modern world or a future dystopia, we��remain��imperfect and rabid. This is a bleak prognosis to give, but the writer offers it without hesitation.

In ���Friday Black,��� people charge into stores on Black Friday, tearing into and trampling over each other like literal zombies just to get a pair of jeans. In deft sentences such as ���Ravenous humans howl��� the main character reports on how commonplace and mundane the hungry violence accompanying Black Friday���s shopping frenzy is, as he enjoys his ���two-dollar menu burgers��� over ���the stench of the freshly deceased.��� As if this image is not stark enough, he��continues ���There are survivors, champions of the first wave, pulling bags stretched to their capacity��� And there are the dead, everywhere.���

Good art, as I see it, must function more like a mirror than make-up or plastic surgery. It seeks to point out, and not to righteously pretend to have all the answers. In��Friday Black, Nana Kwame��Agyei-Brenyah��is successful in holding up society as it is for us to see the depravity that is the effect of organizing society around race and capitalism. If the twists of absurdity leave your insides searing like flavorfully hot spice, you know it is good for you, that it is doing its job.

Algeria 2019���A beautiful line of flight

Algerian students in Paris protesting in solidarity with the uprising back home. Image by Omar Malo, Via Flickr cc.

On March 11, 2019, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, Algeria���s President since 1999, renounced his bid for a fifth mandate and postponed the upcoming presidential elections. After three weeks of peaceful yet massive demonstrations, protesters forced the presidency to put an end to an absurd situation. The incapacitated president is not able to govern. He is not the man holding the nation together. He is merely the symbolic head, the framed picture (le cadre) used by a cartel that controls the state. And the people want the fall of this gang (e-cha’ab yur��d ��sqat al-‘is��ba). Is this a revolution?

Both conjunctural and structural, a revolution brings together many lines of flight. It is a combination of events and movements that break the monotony of the polity. An election that was won in advance thus becomes the occasion for a tide of rebellious bodies to flood the streets. In Algiers, Annaba, Oran, Constantine, Boumerd��s, B��ja��a, a ���peaceful and civilized��� (silmiya wa hidariya) mass has broken the continuum of the never-ending democratic transition that had been appropriated by the regime.

Some lines of flight end in chaos. The popular uprising of 1988 is perceived by many Algerians as the first Arab spring. It forced a reconfiguration of the system of domination, with the adoption of political pluralism, freedom of association and the birth of a dynamic and critical private printed press. It was nonetheless met with violent state repression. The once revolutionary army shot at protesters, killing hundreds. The dramatization of national politics led to the electoral success of a messianic Islamist party (the Islamic Salvation Front), a military coup to prevent the Islamists from running the country and a bloody civil war. More than 150,000 Algerians perished during the Dark Decade.

As the polity was re-ordered, the regime created a hard-segmented world. It aimed at capturing its subjects, ending their flight, entrapping and disciplining them. Privatization was key. After the end of the war, the cartel that controls the state benefited from high hydrocarbon prices. Cronies made fortunes in imports, public construction, as well as in the drug and food industries. National wealth was plundered, public companies privatized, the welfare state undermined. To control popular anger, the regime drew on an ever-growing police apparatus. It offered an alternative between a suspended catastrophe (the repetition of the civil war) or a security-based order embodied by an old man. The youth was trapped, suffocating. Many tried to find their way out through illegal migration. Many died in the sea. Last November, protesters were already in the streets, denouncing this ongoing catastrophe.

Lines of flights move across the organized space of the state to subvert it. Algiers, the capital, was considered to be fortified by anti-terrorist measures, but it is now flooded with joyful and peaceful citizens. The gerontocratic power is hiding, on the very edge of death. A youthful power, popular, sparkling, all-encompassing, is chanting in the streets. Spokespersons of the regime once depicted a childish people in need of discipline. Now the people are jubilant and mature. The government is criminalized. Algerian flags are subversive. The national anthem is once again revolutionary.

All the multiplicities that made the polity are undone and rewoven. For more than twenty years, the cartel constituted around Bouteflika, the army and the technocratic elites formed an heterogeneous coalition. Now, it is falling apart. Members of the ruling FLN are quitting their party and the national assembly. Abdelmajid Sidi Said, the leader of the main trade union (the Union G��n��rale des Travailleurs Alg��riens) and a fierce supporter of the regime, is challenged by his own troops. The National Organization of the Mujahideen, which once revered Bouteflika as a veteran of the war of Independence, is now backing the protesters. Meanwhile, the people, this fantastic creature that had been objectified by the regime, has come back to life as a united multiplicity, a collective body. The youth, this heterogeneous social class, started the movement. It has been joined by parents, workers, middle-class urbanites, Islamists to form a powerful cross-generational, cross-sectoral, cross-ideological movement. ����Protesters repeat an old revolutionary slogan: one hero, the people (un seul h��ros, le peuple). If it is not a revolution, it very much looks like it.

Lines of flight come from inside the polity. Some of them were born in the South and the High-Plateaus region. Far away in the Algerian hinterland, rioters have defied the police state for more than a decade, testing its limits, undermining its authority and forcing it to redistribute a portion of the wealth that was stolen. In the Sahara, social movements trumped the narrative of the suspended catastrophe by organizing peaceful demonstrations and sit-ins. Since the Black Spring of 2001, Kabyle activists have relentlessly defended their culture and their pride while portraying a government of assassins. There is no forgiveness, they said (Ulach Smah Ulach).

Lines of flight also transcend the fixed limits of the nation-state, and connect the rhizomatic polity with other spaces, bodies, experiences. Unruly Algerians traveled across the Mediterranean. They traveled without a visa and burned their passports. Their exile was often already a form of defiance. The current movement is also connected to other uprisings. Algerian protesters learned from the Arab revolutions of 2010-2011. They use similar slogans. They are committed to clean the public space to demonstrate their sense of responsibility, as did their fellow Egyptian revolutionaries in Tahrir. Some influences are unexpected: one of the first messages calling for a massive mobilization on February 22 featured a yellow vest. Transcending the national limits is also a question of solidarity, as leader of the Moroccan Hirak movement, imprisoned Nasser Zefzafi, expressed his supports for the peaceful uprising in Algeria. Mobilized against Omar al-Bashir since the end of 2018, Sudanese protesters also express their solidarity with the Algerian people. These lines of flight will continue to leak, infiltrate and subvert. Soon, Algerian, Moroccan and Sudanese dissidents will inspire others.