Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 223

April 10, 2019

What if postcolonial regimes use stories of your past to justify their rule?

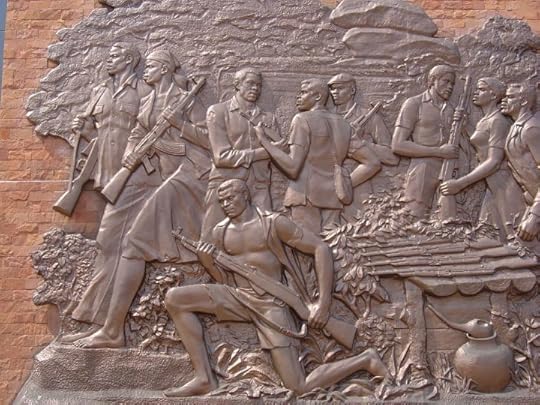

Heroes Acre, Harare, Zimbabwe. Image credit Gary Bembridge via Flickr (CC).

As student activists in the 1960s and 1970s, many black Zimbabweans��agitated and protested against the white nationalism of the Rhodesian Front.��Led by Ian Smith, from��the early to mid-1960s, the��Rhodesian��Front, an organization of local��reactionary��whites,��defied Britain���s order that they negotiate a shared future with the black majority.��Over the next fifteen years, the RF systematically set about removing black people from virtually all aspects of public life, and Smith��declared��that��he didn���t believe in majority rule���”not in a thousand years.” For��black��students, their��politics of liberation found a shared language and organization in support of the nationalist struggle���a rurally-fought bush war being waged by the armed wings of ZANU(PF) and PF-ZAPU.��In 1980,��Zimbabwe gained its independence through negotiated settlement.��Yet the freedom dreams which inspired these protestor���s activism was a far cry from the narrow instrumental anti-colonialism used by ZANU(PF) to maintain its rule after 2000.

Student activism in Rhodesia

In��a recent journal article,��Nationalists with No Nation,��I��explore the stories told by three prominent and committed student activists, whose student politics��against the Rhodesian Front��led them into careers as nationalist leaders.

The first,��Dzingai��Mutumbuka��had been a science student in the mid-1960s, when he disrupted Ian Smith���s Rhodesian Front rallies as the white government prepared for its far-right Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain. His student activism led��Mutumbuka��to join ZANU in the 1970s and he went on to become��Zimbabwe���s highly respected first Minister of Education at independence���responsible for a remarkable set of reforms widely considered to be the party���s biggest success stories. The second, Simba Makoni took a similar path a few years later. Makoni���s protests in the early 1970s led to his arrest and the��largest ever pre-independence demonstration��in 1973. Fleeing Rhodesia for the UK, Makoni too entered ZANU from where he also ended up as a Minister in Zimbabwe���s cabinet at independence. Finally,��Ranga��Zinyemba��too had to flee the country after leading student demonstrations in 1977 against the proposal to conscript black students into the Rhodesian army. Standing on top of an up-turned bin in the square outside parliament, he rallied black students in a speech against the government: ���We will not do this: these are our brothers and our sisters.��� After threats from the government, he enlisted the help of sympathetic white Catholic activists and posing as a trainee priest on his way to a Malawian seminary fled to the UK. He too joined ZANU abroad, but instead of pursuing a career in politics, became an educationalist and returned after independence to work at the University of Zimbabwe.

Politics marshaling history

All of these men distanced themselves from Robert Mugabe���s government after 2000.��Their anti-colonial activist pasts, however, were a useful resource to the party.��By the late 1990s, facing economic decline and widespread civic unrest, the ZANU(PF) government��had��sought to radically re-orientate its justification��to��rule.��Rather than��developmentalism��that emphasized education, jobs and healthcare, the party revived an anti-colonial narrative that took the violent seizure of white commercial land, what became��known as�����Fast Track Land Reform,�����as the completion of the bush war.��This political strategy meant violently upholding what Robert��Muponde��called��a�����virulent, narrowed-down version of Zimbabwean history��� [where] to insist on being different is to invite the title of enemy of the state: it is to invite treason charges upon oneself.�����Using the communications machinery of the state, the party lionized its leaders�����anti-colonial student activism or war records as the source of authority that was required to rule.��Mugabe himself made full use of his own student activist past in this effort. In 2016, he lionized Fort Hare, where he studied in 1950, as “the cradle of African anti-colonial ideology.”

Asserting��one���s��own story

How do you tell your story of political awakening, when��its��narrative has already been claimed?��These��three��answered this question in different ways, but all of which rejected��ZANU(PF)���s post-2000 narrative.��They stitched together alternative nationalist stories, built around different political ideas, that accounted for their much more complicated student experiences at university in Rhodesia��and where it sent them in life.

For��Mutumbuka, this meant��upholding��an��alternative��pragmatic type of ZANU(PF) nationalism that emphasized the benefit he got from his university experiences and which inspired his work��in��the 1980s��transforming a��Rhodesian��education system into a Zimbabwean one.��He said, ���Basically the system needed to be rapidly expanded but the quality maintained. That is what is unique about Zimbabwe up to this day��� [it] is the only country that rapidly expanded education whilst maintaining quality.�����Makoni��similarly distanced himself from the authoritarianism that had come to typify ZANU(PF) rule after 2000 by narrating the story of his career as a drive towards political cosmopolitanism.��In��2008,��Makoni��ran for President as an ���Independent.��� War veterans threatened him with violence and Mugabe called him a prostitute. He finished third behind Mugabe and Morgan Tsvangirai.

Lastly,��Zinyemba��deliberately recalled the joy of his student past:��learning to love literature, overcoming insecurities about his rural background, meeting girls and getting married.�����My life at the University of Rhodesia was perhaps the best experience I���ve ever had,�����he��told me.��Such descriptions formed the basis of��Zinyemba���s��critique of how the ruling party has run down the higher education system��throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

But by affirming an alternative politics of nationalism through��telling their��stories of student activism��against the��Rhodesian Front, these men were��also reclaiming those much more inscrutable and exciting memories of when one came of age.

Zimbabwean stories of student activism in Rhodesia

Heroes Acre, Harare, Zimbabwe. Image credit Gary Bembridge via Flickr (CC).

As student activists in the 1960s and 1970s, many black Zimbabweans��agitated and protested against the white nationalism of the Rhodesian Front.��Led by Ian Smith, from��the early to mid-1960s, the��Rhodesian��Front, an organization of local��reactionary��whites,��defied Britain���s order that they negotiate a shared future with the black majority.��Over the next fifteen years, the RF systematically set about removing black people from virtually all aspects of public life, and Smith��declared��that��he didn���t believe in majority rule���”not in a thousand years.” For��black��students, their��politics of liberation found a shared language and organization in support of the nationalist struggle���a rurally-fought bush war being waged by the armed wings of ZANU(PF) and PF-ZAPU.��In 1980,��Zimbabwe gained its independence through negotiated settlement.��Yet the freedom dreams which inspired these protestor���s activism was a far cry from the narrow instrumental anti-colonialism used by ZANU(PF) to maintain its rule after 2000.

Student activism in Rhodesia

In��a recent journal article,��Nationalists with No Nation,��I��explore the stories told by three prominent and committed student activists, whose student politics��against the Rhodesian Front��led them into careers as nationalist leaders.

The first,��Dzingai��Mutumbuka��had been a science student in the mid-1960s, when he disrupted Ian Smith���s Rhodesian Front rallies as the white government prepared for its far-right Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain. His student activism led��Mutumbuka��to join ZANU in the 1970s and he went on to become��Zimbabwe���s highly respected first Minister of Education at independence���responsible for a remarkable set of reforms widely considered to be the party���s biggest success stories. The second, Simba Makoni took a similar path a few years later. Makoni���s protests in the early 1970s led to his arrest and the��largest ever pre-independence demonstration��in 1973. Fleeing Rhodesia for the UK, Makoni too entered ZANU from where he also ended up as a Minister in Zimbabwe���s cabinet at independence. Finally,��Ranga��Zinyemba��too had to flee the country after leading student demonstrations in 1977 against the proposal to conscript black students into the Rhodesian army. Standing on top of an up-turned bin in the square outside parliament, he rallied black students in a speech against the government: ���We will not do this: these are our brothers and our sisters.��� After threats from the government, he enlisted the help of sympathetic white Catholic activists and posing as a trainee priest on his way to a Malawian seminary fled to the UK. He too joined ZANU abroad, but instead of pursuing a career in politics, became an educationalist and returned after independence to work at the University of Zimbabwe.

Politics marshaling history

All of these men distanced themselves from Robert Mugabe���s government after 2000.��Their anti-colonial activist pasts, however, were a useful resource to the party.��By the late 1990s, facing economic decline and widespread civic unrest, the ZANU(PF) government��had��sought to radically re-orientate its justification��to��rule.��Rather than��developmentalism��that emphasized education, jobs and healthcare, the party revived an anti-colonial narrative that took the violent seizure of white commercial land, what became��known as�����Fast Track Land Reform,�����as the completion of the bush war.��This political strategy meant violently upholding what Robert��Muponde��called��a�����virulent, narrowed-down version of Zimbabwean history��� [where] to insist on being different is to invite the title of enemy of the state: it is to invite treason charges upon oneself.�����Using the communications machinery of the state, the party lionized its leaders�����anti-colonial student activism or war records as the source of authority that was required to rule.��Mugabe himself made full use of his own student activist past in this effort. In 2016, he lionized Fort Hare, where he studied in 1950, as “the cradle of African anti-colonial ideology.”

Asserting��one���s��own story

How do you tell your story of political awakening, when��its��narrative has already been claimed?��These��three��answered this question in different ways, but all of which rejected��ZANU(PF)���s post-2000 narrative.��They stitched together alternative nationalist stories, built around different political ideas, that accounted for their much more complicated student experiences at university in Rhodesia��and where it sent them in life.

For��Mutumbuka, this meant��upholding��an��alternative��pragmatic type of ZANU(PF) nationalism that emphasized the benefit he got from his university experiences and which inspired his work��in��the 1980s��transforming a��Rhodesian��education system into a Zimbabwean one.��He said, ���Basically the system needed to be rapidly expanded but the quality maintained. That is what is unique about Zimbabwe up to this day��� [it] is the only country that rapidly expanded education whilst maintaining quality.�����Makoni��similarly distanced himself from the authoritarianism that had come to typify ZANU(PF) rule after 2000 by narrating the story of his career as a drive towards political cosmopolitanism.��In��2008,��Makoni��ran for President as an ���Independent.��� War veterans threatened him with violence and Mugabe called him a prostitute. He finished third behind Mugabe and Morgan Tsvangirai.

Lastly,��Zinyemba��deliberately recalled the joy of his student past:��learning to love literature, overcoming insecurities about his rural background, meeting girls and getting married.�����My life at the University of Rhodesia was perhaps the best experience I���ve ever had,�����he��told me.��Such descriptions formed the basis of��Zinyemba���s��critique of how the ruling party has run down the higher education system��throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

But by affirming an alternative politics of nationalism through��telling their��stories of student activism��against the��Rhodesian Front, these men were��also reclaiming those much more inscrutable and exciting memories of when one came of age.

April 9, 2019

‘We believed that the only way Africa could be liberated was through a socialist revolution’

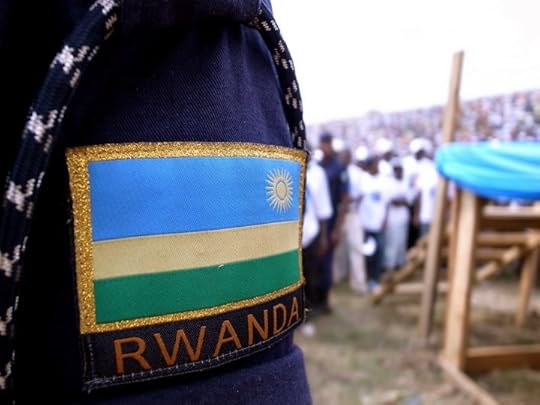

Image credit Miguna Miguna.

Miguna��Miguna,��the��Kenyan activist and lawyer, rose to international prominence��in 2018,��after administering��Raila Odinga���s��unofficial inauguration ceremony��as��Kenya���s ���People President.��� The event��challenged��the legitimacy of��Uhuru Kenyatta���s electoral victory in Kenya���s 2017��presidential rerun,��which��Odinga��and his��opposition��NASA coalition��had��boycotted. Following this��ceremony, the Kenyatta government��expelled��Miguna��from the country��accusing him of treason.��In exile��in Canada,��Miguna��has��remained��one of the��most outspoken and popular��critics of the current Kenyan��regime.

Like many��of��the leading��Kenyan��opposition figures of his generation,��Miguna��cut his teeth��politically��as a student activist��at��the��University of Nairobi in the 1980s. During��that decade,��as��the regime of Kenya���s second president, Daniel arap��Moi, increasingly drove��opposition actors��underground, university students and faculty became��some��of the��only��public��voices of dissent��left��within the country. In response, Moi escalated his repressive tactics��against the university:��closing campuses��on multiple occasions,��authorizing security��forces�����assault��of��student protesters��and even arresting dissident professors and student��activists.

In November 1987,��government forces detained��Miguna��and his fellow student leaders of the Students��� Organization of Nairobi University (SONU)��shortly after��they publicly��challenged��the��Moi���s��regime��at their swearing-in ceremony. In the aftermath of this event,��the student union was��once again banned and��Miguna��and some of his colleagues��were��forced into exile. Miguna��ended up in��Canada��via Tanzania��and Swaziland, where he��eventually��completed his��undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto before studying��law at��the��Osgoode��Hall��Law School of York University in Toronto.

My��recently published article��for the��academic��journal��AFRICA, recounts the��history of the Kenyan student movement during this period. In it, I examine how the National Youth Service Pre-University Training Program (NYSPUT), a��paramilitary��camp��designed by the Moi government in the 1980s to instill discipline and a sense of loyalty to the state in��prospective��university students, actually helped to radicalize a number of students like��Miguna.

Miguna��recently granted me an interview to discuss his time as a student activist and the ways in which these experiences��have subsequently come to shape��his��life in politics.

Luke Melchiorre

Is��there a reason that a lot of��Kenyan��student leaders, like yourself,��came��from a��place like Nyanza��[in Western Kenya], which has been historically marginalized by the Kenyan state?

Miguna Miguna

It was poverty, but it was mainly oppression.��A lot of people from Nyanza fought for the liberation of Kenya.��When independence came,��a lot of Kenyans, especially from Nyanza realized that��there was no difference��between the colonial administration and the independent government. In fact it became worse [in Nyanza], so there was a lot of resentment��against the Kenyan regimes��as I grew up in Nyanza, because it was obvious to even a��young��child like myself��that��[Jomo]��Kenyatta��[the first President of��independent��Kenya]��had taken independence to mean that��only a small clique of Kikuyus��(it was not all Kikuyus)��would benefit from the��independence struggle. So��we grew up��in Nyanza��with eagerness to join the struggle, to uplift the conditions that we saw around��us.

Luke Melchiorre

Prior to your admission to the university,��it was��made��mandatory��in 1984��for all prospective university students��to enter��the��national youth��service pre-university training��program. What did this training program consist of?

Miguna Miguna

It was not actually��even��a training camp. It was a boot camp. It was meant to punish us for having passed our high school exams, having made it to university. It was to prove to us��that��education��was nothing. That all that mattered was that you had��money, you had political power, which you could wield at will against those who believed they had knowledge���like us.

Luke Melchiorre

The��NYSPUT��was��supposedly��designed to instill discipline in universities students like yourself and make you loyal to the regime. Is that what happened in practice?

Miguna Miguna

Exactly the opposite.��The only positive thing I got from the NYSPUT��was that it gave me and others access to the entire��population that��were going to go to university. People I would never have met if I��had just left my home and gone to��the��University��of Nairobi��and others had gone��to��Egerton, Moi��and��Kenyatta��universities.��But now they were going to��Gilgil��[where the NYSPUT was held]��and��now I was meeting all of them.��It��allowed��people like me, who were already politically conscious and growing more conscious and radical, to build alliances, to inculcate a sense of comradeship amongst ourselves,��to emerge as potential��student leaders��and later on national leaders.��And that���s what��we��did. By the time,��we now went to��the university, some of us had already demonstrated our bona��fides��at NYSPUT��and so when we contested��for leadership positions��at the��University of Nairobi and campaigned on radical platforms,��because��we had already demonstrated what we stood for, the students voted for us in��unison.

Luke Melchiorre

What was the political ideology of��you and your��fellow student leaders��at the university?

Miguna Miguna

It was almost like we had formed a��political movement at the University of Nairobi by November 1987. There was the government camp and our camp. We were socialists��in orientation,��we believed in scientific socialism. We believed that the��only way that Africa could be liberated was through a socialist revolution. We then politically said that the people that were governing��Kenya��had betrayed the��dreams of the freedom fighters that fought for independence and that it was time that we actually gained��true��independence. What we had was a flag and a national anthem and an emblem, but there was no freedom.��Our opponents supported the status quo���the Moi/KANU regime. The regime that detained many of its critics, suppressed freedom of the press, expression and association. Their ideology if one could refer to it as that was merely to continue on the same path that Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel��arap��Moi had followed.

Luke Melchiorre

When you look back at your time as a student leader, how, if at all,��do you think��it shaped��your future career in politics?

Miguna Miguna

I have to say it is not the student leadership that shaped my career in��politics. It is my ideological beliefs��and commitments��that did. Whether I was in student leadership or not, it would not��have��changed��my ideology, my commitments and��the trajectory that my life took, but it helped me work with��others, deepen my ideological and��philosophical understanding of society and it made us demonstrate practically��that the edifice on which the Kenyan state and other neocolonial states in Africa stood��was quicksand.

Luke Melchiorre

Finally, what is your relationship now with Raila��Odinga��today?

Miguna Miguna

I��worked with Raila Odinga between 2006 and 2011. At the time, I considered��Raila��to��symbolize the struggle some of us had had for a genuine liberation of Kenya.��I believed then that he could be the leader of a cadre of patriots who were committed to transforming the country and bringing forth social justice. But��I soon realized that��Raila does not represent a new Kenya.��That Raila is neither progressive nor transformative. I realized that Raila���s agenda��[is]��to cement the culture of impunity where privilege vests on those who have occupied positions of power and used those positions to enrich themselves. Raila is not interested in the creation of a merit-based society, which is what I���m committed to.��And��after��he surrendered��and betrayed��the struggle��for electoral justice and social justice��on March 9th,��[2018, the��day��in��which Odinga��famously shook Uhuru Kenyatta���s hand, making peace with him],��I have not spoken��with��him, because there is nothing to discuss. He came to��the airport on March 26, 2018 after my second detention by the Kenyatta regime but we didn���t really speak.��How do you say that Uhuru Kenyatta has perpetrated an electoral fraud and is trying to institutionalize tyranny in Kenya and��it is obvious that that is the case, then tomorrow you say that Kenyatta��is��your��best friend and the people that died in defense of the constitution, the rule of law and democracy, you don���t even mention and you��don���t ask for justice for them? You become nothing but an opportunist and a��hypocrite. And��hypocrites are the swine��of history.

The crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front

RPF rally in Gicumbi, Rwanda 2010. Image credit Graham Holliday via Flickr (CC).

At the end of May 1997, one week after President Mobutu was toppled in a military coup, Judi��Rever, a Canadian reporter for RFI, arrives in the Democratic Republic of Congo���then Zaire���to cover the unfolding humanitarian crisis. She travels south of Kisangani to refugee camps where Hutu refugees have sought safety after a series of attacks. Here, in the eery quiet of a clearing in the forest, she comes across ���dozens and dozens��� of survivors. Some have lost their families and others look as though they are ���on the verge of death.��� They all say they are escaping attacks by the RPF, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, part of the rebel alliance that has overthrown Mobutu (today, the ruling party in Rwanda). Across the border in Rwanda, in a transit camp where Hutus returning from Congo are being registered by the UN, refugees say the same thing: that they fled Rwanda to Congo because the RPF was killing Hutus.

Back in Paris where she lives,��Rever��tries to piece together what she has seen. In the media and in political and humanitarian circles, there is one narrative: that ���an African renaissance��� is beginning in the Congo, heralding a ���new age of peace and security.�����Rever��herself believes, like most people, that during the Rwandan genocide the RPF ���swooped in and routed Hutu extremists responsible for killing Tutsis and moderate Hutus.��� Yet this narrative is ���diametrically opposed��� to what she has seen in both Congo and Rwanda. Her interviews lead her to question everything she has read about the genocide. What unfolds in the remainder of her book,��In Praise of Blood: The Crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front,��is a detailed account of the RPF and their crimes before, during and after the Rwandan genocide.

Drawing from reports by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), which was set up in the aftermath of the genocide to try Rwandans accused of��human rights violations, as well as from��select��interviews with former intelligence officers��and RPF defectors��who used to work for��Kagame, Rwandans in exile, survivors��of massacres,��former investigators,��academics, and others,��Rever���s��account��reveals��the RPF���s methods of operation. It says how��they carried out massacres against Hutu civilians�����with great precision,��������leaving barely a trace,�����what motivated them, and how they managed to evade justice for so many years.��Although these crimes have been documented��for many years��and as early as 1994��by groups��including��The Human��Rights Commission on Rwanda, Amnesty International,��the UN, MSF, and a number of notable scholars,��In Praise of Blood��is notable for��providing more information, both ���qualitative and quantitative,�����about��the RPF���s crimes.

A key element to understanding the RPF���s operations during and after the genocide, is its intelligence wing, the DMI (Directorate of Military Intelligence), which��Rever��describes as the ���main instrument through which crimes were inflicted on Rwandans during the genocide��� and the ���continuing source of control and violence against Rwandans and Congolese.��� Investigators for the ICTR found that while the RPF had killed civilians, it was DMI representatives under orders from��Kagame��who initiated massacres. A controversial revelation in the book, based on the ICTR report and on interviews with former RPF officials, is that a covert group of ���technicians��� trained by DMI before 1994 were trained to, among other things, infiltrate��Interahamwe��Hutu militias and incite them to commit massacres against Tutsi civilians. In some cases, she writes, the RPF even actively killed Tutsi villagers in staged attacks that were blamed on Hutu mobs.

Byumba,��Giti��and�����Claiming Land���

Among the many grisly incidents of violence that��Rever��documents in her book is one which became the ���trademark��� method that RPF used for killing Hutus: the massacre at��Byumba��stadium in April 1994, two weeks into the genocide. Thousands of Hutu refugees had fled to��Byumba��from camps bombarded by��Kagame���s��forces. After three days without food, RPF soldiers urged them to go to the football stadium of the town, promising food, drink and cooking supplies. After the peasants filed into the stadium and settled down for the night, RPF officers opened fire, killing everyone inside. Bodies were buried, but later dug up and incinerated under��Kagame���s��orders;��Kagame��feared that France���s satellite surveillance would find evidence of mass graves.��Rever��writes that this method of controlling access to an area, luring in large groups of Hutus with promises of food and safety, and then killing them or taking them away to be killed elsewhere, was used across the country during the genocide. The RPF���s success in hiding these crimes depended on concealing the ���the evidence by turning human beings into ash.��� Sometimes, she writes, the RPF ���buried the Hutu dead in graves with Tutsis who had been murdered by Hutu militia.���

In Praise of Blood��details��several��other massacres by the RPF,��including��at��Karambi��trading center, where��the��RPF��killed��an estimated 3000 people before President��Habyarimana���s��plane was shot down,��at Ruhengeri where DMI units with civilian cadres massacred Hutus in July and August��of 1994, at��Gabiro��in a guest lodge that had once been the home of Rwanda���s king,��and��at��Giti.��Giti��stands out��as��a ���startling use�����of��RPF�����propaganda��� where RPF��forces massacred Hutu civilians at a primary school��in��Giti��and then��agreed with the town���s mayor that in return��for RPF protection, he would be known as the��only mayor in Rwanda who had ensured that no genocide against��Tutsi took place in his commune.

Why would��Kagame���s��forces undertake such widespread, targeted and horrific killings? Concerning��Byumba, a number of people in the book assert that the RPF���s actions were about ���claiming land in��Byumba, the breadbasket of Rwanda,��� for thousands of Rwandan Tutsis who had grown up in Uganda. Indeed, the narrative thread of RPF���s crimes must be placed in the context of their origins in Uganda, their invasion of Rwanda in 1990 and the decision to shoot down the plane of Rwanda���s president, Juvenal��Habyarimana, widely seen as the event that��sparked the beginning of the genocide. Although most mainstream accounts of the genocide attribute��Habyarimana���s��death to Hutu extremists,��In Praise of Blood��explains through first hand testimonies how RPF engineered the downing of the plane. As soon as it was shot down, between 25,000 and 30,000 RPF troops moved into position to launch an offensive ���which would have required weeks of preparation.��� Several people interviewed in the book believe that the RPF had one main objective which was to ���seize power��� and use the ���massacres as stock in trade to justify its military operations.���

If indeed that was true, it worked: while international organizations and the UN were aware of some of the massacres by RPF, including at��Byumba, the international community viewed these events through a ���different moral lens��� than they applied to the Hutu��g��nocidaires.��Kagame���s��killings were seen as ���reprisal killings��� or ���collateral damage.”

Byumba,��Giti��and�����Claiming Land���

While one might categorize��the��1994��killings by the RPF��as specific to the violence unfolding in the context of��genocide, what happened after the genocide��during the��counter-insurgency��when��Kagame��sent his troops into the DRC under the pretext of hunting down Hutu��g��nocidaires��is arguably��more disturbing, perhaps for the simple reason that unlike the genocide,��Rever��states, it��went on with ���little outcry from the world,��� reaching its peak in 1997.

The 1996 invasion of Zaire forced hundreds of thousands of��Hutu��refugees to return home and ���face a new round of ethnic cleansing.�����Rever��writes how��during this period,��RPF��killed��Hutu civilians in areas under their control�����hill by hill,��� including near military bases, and in caves where thousands��were hiding��from��Kagame���s��soldiers.��Meanwhile, Hutu officials��who were unwilling to support the��Hutu insurgency and joined the RPF were��also��killed, along with their families.��Some��of these��massacres have��been confirmed in reports by��Amnesty��International.

Among the��RPF���s actions��in this period included “false flag” operations. In one incident, based on interviews with former RPF intelligence officers,��Rever��describes��how��RPF staged an attack on a refugee camp in��Mudende, killing��hundreds of��Tutsis. This��helped to demonize��Hutus by putting the blame��for the attack��on Hutu guerrillas��and��persuaded��the US to�����continue training RPF soldiers and supplying Rwanda with military material.���

Although the killings in these years targeted not only Hutu and Tutsi civilians, but also UN observers, Spanish aid workers and a Canadian priest, no action was taken against the RPF internationally. As early as May 1994, during the genocide, a UN refugee agency report documented killings by the RPF. After the genocide, in 2006, a French judge, Jean-Louis��Brugui��re��issued arrest warrants against those involved in the shooting down of��Habyarimana���s��plane and in 2008, Spain issued arrest warrants for 40 of��Kagame���s��senior commanders, but these did not result in any arrests.��Rever��writes that authorities in Europe, North America and Africa refused to extradite those implicated. In 1997, when the Canadian priest was killed by RPF and a witness flew to Nairobi to give a statement to the Canadian embassy, there was no follow up.

The latter chapters of��In��Praise of Blood��offer startling explanations of what was happening in the higher echelons of institutions tasked with pursuing��the RPF��and the ���enormous lobbying, money and influence�����Kagame��used to ���penetrate institutions and people in power.�����Rever��exposes��how a clandestine unit, the Special Investigations Unit, which was��set up by the ICTR in 1999 specifically to investigate crimes by��Kagame���s��army and��relied on testimonies from Rwandan witnesses in exile,��found that their sources��were being intimidated and��disappeared.��The��ICTR��suspended��investigations against��Kagame���s��commanders in order not to lose the cooperation of the Rwandan government in investigating Hutu��g��nocidaires.��Eventually,��Rever��writes,��the SIU was hijacked by Paul��Kagame��himself,��and the Chief Prosecutor,��Carla Del Ponte��removed from her position�����at the behest of the US�����after she made it clear that she intended to indict RPF commanders.

In a stunning revelation that demonstrates just how intertwined the relationship between Rwanda and the US was,��In Praise of Blood��demonstrates how��Kagame��and the US Ambassador at the time agreed to a deal whereby,��rather than going through the ICTR process, the government of Rwanda would have the ���opportunity��� to prosecute massacres by the RPF. In other words, ���the killers would investigate themselves.�����Rever��writes that the ICTR became essentially ���a surrogate of Washington and by extension,��Kagame.��� The UN tribunal closed in 2015, having convicted 61 people, all of them linked to the former Hutu regime. The trial that Rwanda eventually carried out on its own was seen as a ���political whitewash,��� even by Human Rights Watch, which��Rever��demonstrates was primarily interested in massacres of Tutsis in the genocide.

It was not only international institutions and western governments that became intertwined with the powerful interests of the RPF, but also NGOs���specially��the London-based organization African Rights��which��defended the RPF against reports that they had engaged in violence, and was eventually found, according to the book,��to be on the RPF payroll.��The other organization singled out for their refusal to give adequate weight to the RPF killings is��Human Rights Watch��which documented RPF killings,��but��downplayed them��as ���generalized violence.���

For those implicated in��massacres, not only were they not prosecuted, but several moved onto high positions in UN peacekeeping operations;��Patrick��Nyamvumba��who��allegedly��gave the orders for massacres during the genocide��and��was in charge of creating units to ���screen, mop up and otherwise rid the hillsides of Hutu civilians,��� was appointed as Head of UNAMID, the UN-African Union peacekeeping operation in Darfur in 2009. Another man, Jean Bosco��Kazura, allegedly in charge of soldiers who killed civilians east of Kigali at the height of the genocide and at��Gabiro, became the peacekeeping chief of the UN���s force in Mali in 2013.

The Struggle of Memory��against Fear

Any attempt to uncover the carefully buried secrets of a powerful regime is likely to result in reprisals.��In Praise of Blood��describes��what happened to��Rwandans��who��came��forward to testify against��Kagame��and the RPF. While some managed to escape into exile, others were��killed,��disappeared��or imprisoned.��Rever��writes how she��too��became a target, not only in Europe where she travelled for interviews, but also in Canada where she received threatening calls singling out her children.

At the end of her book,��Rever��writes that she chose to focus on the crimes of the RPF and not on the genocide against Tutsis since there already exists a plethora of material about Hutu-on-Tutsi violence. However, for this reason, it is sometimes difficult while reading��In��Praise of Blood��to keep the two narratives in mind and to understand how both unfolded simultaneously within the same time period. Some parts of the book raise questions. For instance,��Rever��writes that eight per cent of the Hutu population actively engaged in killings against Tutsi and that ���the majority of Hutu civilians did not kill their neighbours.��� Others, including Mahmood��Mamdani, whose book When Victims Become Killers tries to make sense of the killings, assert that contrary to��Rever���s��claim, hundreds of thousands of ordinary people participated in the genocide.

Other claims in the book��which may��require further��substantiation��include a citation from the University of Rwanda which estimates that forty thousand civilians had been killed by the RPF in two regions of the country by early 1993.��That is a colossal number by any standard and difficult to understand��how such a large number of killings could go unnoticed��well��before the genocide began.��Disputes over numbers are��common in��the divergent accounts of��the Rwandan genocide.��Rever��estimates that��based on her evidence��and that of the ICTR investigators,��the RPF killed between several��hundred thousand��and one million people.

In Praise of Blood��claims��that��a parallel genocide��against Hutus��took place in Rwanda, a claim which has elicited��substantial debate��from��scholars including��Claudine Vidal and Filip��Reyntjens. Vidal��argues��that��Rever���s��book ���blurs the line between investigation and indictment��� and describes the massacres in such a way as to ���classify them as genocide.��� Rather than ���doing the work of judges��� and trying to apply the legal classification of genocide onto the crimes of the RPF,��she writes��that�����journalists and social scientists��should be calling for investigations equivalent to those carried out��into the Tutsi genocide.��� In other words, ���There is no need for it to be genocide to justify investigation into these massacres.���

A proper judicial investigation would be required to determine whether��or not a genocide against Hutus did take place. Filip��Reyntjens at the University of Antwerp��argues��that��although he is not one to advance the thesis of double genocide, the massacres may indeed��demonstrate an intention to destroy Hutu,��a strong indicator being the separation of Tutsis and Hutus, and the use of help from Tutsis in killing Hutus and sparing Tutsis.��Given that the crimes of the RFP will likely go unpunished, and��that the��judicial truth will not be established,��he says,�����the historical truth can and must be sought.�����To this end,��Rever���s��work remains��significant.

In his book,��Mamdani��writes��that�����Violence cannot be allowed to speak for itself, for violence is not its own meaning. To be made thinkable, it needs to be historicized.�����In her final chapter,��Rever��quotes an opposition Tutsi activist who argues��that the RPF killings are not reprisals for the 1994 genocide against Tutsis, but rather, revenge for 1959, when waves of Tutsi were forced to flee��during the 1959 revolution and��the country transitioned from a Belgian colony with a Tutsi monarchy to an independent Hutu dominated Republic.��Likewise, in��Mamdani���s��work, he makes the claim that ���The failure to address the citizenship demands of the ���external��� Tutsi marked the single most important failure of the��Habyarimana��regime.��� There is no doubt that understanding the deeper roots of��RPF violence, and by extension, the regime in place today, requires venturing back into the complex and difficult history of Rwanda and the region.

The official narrative of the genocide, which claims that Tutsi victims were rescued from Hutu killers by the RPF, has persisted for decades, rendering the stories of one side continuously visible and subject to official commemoration while actively silencing the memories and stories of the other. This narrative has no doubt served��Kagame���s��regime extremely well as he continues to receive��awards,��adulations, over��984 million dollars��in aid in 2015/2016 and unwavering��support��from the likes of Howard Buffet and Tony Blair. Even his decision to rule until 2034,��Rever��notes has drawn ���only tepid criticism��� from Washington and London.

In the words of Theodore��Rudasingwa,��Kagame���s��former Chief of Staff, who spoke in the BBC documentary,��Rwanda, The Untold Story, ���Kagame���s��impunity has reached scandalous proportions,��� and the cost in terms of lives destroyed in both Rwanda and the DRC has been colossal.��In Praise of Blood��is a courageous, powerful and meticulously documented work that counters the narrative on which��Kagame���s��impunity rests, resurrects the memories of countless people, and brings their stories out from the silence and the intricate machinery of fear that the Rwandan regime has worked so hard to maintain.

April 8, 2019

The marginalization of African runners

Image credit Elisabeth via Flickr (CC).

On March 11,��2019,��the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF)���the international governing body of the sport of athletics���published a press release about changes to be implemented in track and field���s most prestigious competitions���the Diamond League.��One proposed change, in particular, that is rattling the running community, is that the longest distance��race��to be held will be the 3,000��meters. While mourning the�����death of the 5k�����some are asking: to what extent is this deliberately exclusionary of��East Africans?

Hobby joggers can rejoice, because indeed the tremendously popular recreational event��run on city streets and not tracks,��will likely continue to grow.��But for the Kenyans and Ethiopians who have been dominating long distance running��on the track��for the past��five decades, and to whom average runners get to compare their mediocre times, this seems��regressive��in many ways.

The��athletic��federations from Kenya and Ethiopia, have been quick to point this out. On March 14,��Athletics Kenya called the change ���illegitimate.��� Then, the��Ethiopian Athletics Federation called out��the��IAAF���s research��that led to this decision,��and criticized that although it ���included��detailed research and discussions with athletes, coaches, fans, and broadcasters,��there is no record that shows a platform was provided for long distance athletes particularly from East Africa.��� Two days prior, Ethiopian legend, Haile��Gebreselassie,��also pointed��to��the��disproportionate��affect the change would have on East African countries.

The Diamond League in many ways is the cr��me de la cr��me of track and field.��Even in comparison to the Olympics, for countries like Ethiopia��and Kenya, which can only send three athletes per event,��open track races offer more opportunities for their��abundance of talent to produce world records and the most competitive performances.

Further, the prize money is unbeatable.��Each competition has prize monies beginning with $10,000 for first place, $6,000 for second and $4,000 for third. The final prize monies amount to��$50,000, $20,000, 3rd��$10,000, and decrease incrementally to 8th��place.��In 2018, Ethiopian men secured positions one through��five��in the 5,000m. In 2017,��they also took four of the top eight positions.

The notion that��a thirteen-minute running��race��is boring for most fans to��watch is not a��novel��concern to most track fans.��(In any case, most live or delayed broadcasts of major track and field meets, shows the start of these races, usually cut away to show field events, then return for the last two laps of the race for the proverbial big finish.) Making the sport more popular has been central to conversations about athletics��over��the last��few��years.��Lack of sponsorship flexibility, poor race commentary,��and interpreter-less interviews with��African athletes unable to explain their��race strategies��and personal biographies��in non-native languages��and reduced to monosyllabic answers in English,��are among the oft-cited reasons for the lack of popularity.

This��is��probably��what Sebastian��Coe, the president of the IAAF means, when he says that�����we can make it even stronger and more relevant to the world our athletes and our fans live in today.���

As the representatives at the Ethiopian Athletics Federation explicitly indicate, who��precisely�����we��� means is hardly defined, and plainly exclusionary.��Histories��of financial embezzlement��(at the center of which is an African athletics official, deployed there to represent the continent���s athletes, but instead enriched himself)��and being curiously headquartered in the wealthy city-state of Monaco, have not exactly imbued the IAAF with widespread trust.��The��IAAF��have considerable power over the fates of East African runners, who have��singlehandedly brought the sport of running��to far more competitive heights.

Aren���t these runners the best placed to determine what gives the sport its relevancy? Unfortunately, the IAAF doesn���t seem to agree.

Lumumba lives

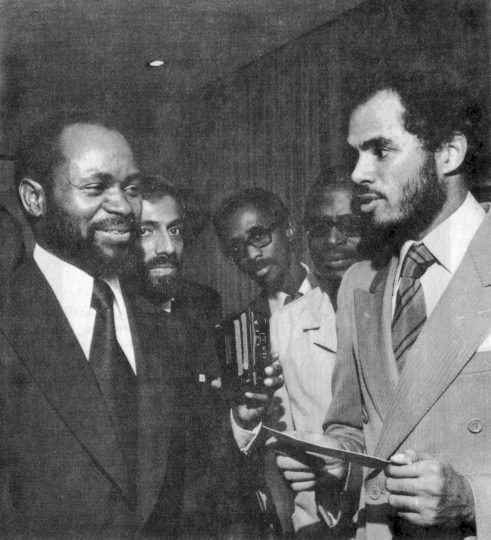

Lumumba in Montreal in July 1960. Image credit Archives de la Ville de Montr��al via Flickr (CC).

On January 17, 1961, Patrice Lumumba, the Congo���s first Prime minister,��was assassinated, together with his friends Maurice��Mpolo��and Joseph��Okito. Lumumba had made powerful enemies in Brussels and Washington. And the Belgian and American governments were directly involved in his assassination. Lumumba had been a champion of Pan-Africanism and African nationalism. After his death, he became ���Africa in its entirety,��� as Jean-Paul Sartre wrote at the time.

What is Lumumba���s ���political afterlife��� nearly sixty years later? In Belgium, several cities have recently renamed streets and squares after Lumumba, responding to grassroots��campaigns led in great part by Afro-descendent activists. The stakes around Lumumba���s memory in the Congo���s former colonial metropole��are diverse. But the most interesting mobilizations around his name are by young black Belgians who are willing to go against Belgian society���s ingrained racism and are forcing political parties to��take position on the colonial past.

The configuration is different in the Congo, where Lumumba was officially proclaimed a national hero in 1966. In recent years, Joseph Kabila (who just stepped down as president after 18 years in power) has multiplied references to Lumumba and the circumstances around the Congo���s decolonization. Kabila has not always been consistent in his historical references���in 2004, when he addressed the Belgian parliament, he praised the memory of Leopold II and the Belgian ���pioneers��� who colonized Central Africa. However, as his relation with the Western countries that initially welcomed his arrival to power soured, Kabila realigned himself more closely with the rhetoric of Congolese nationalism and did not fail to remind Belgium of its crimes in the Congo���including the assassination of Lumumba.

Within the field of Congolese politics, a diversity of actors claim Lumumba as a figure of inspiration. During the recent presidential elections, Antoine��Gizenga���s��Unified��Lumumbist��Party rallied behind the candidacy of Emmanuel��Ramazani��Shadari, Kabila���s handpicked successor. Yet, this did not stop supporters of Martin��Fayulu, the candidate for the opposition platform��Lamuka, to call their champion a ���people���s soldier��� who was�����ready to die for the Congo��� like Lumumba. And when F��lix��Tshisekedi, the (contested) winner of the elections, was sworn-in as president, he of course paid homage to the sacrifice of Lumumba��in his inaugural speech��(Tshisekedi��also praised, at much greater length, the memory of his late father Etienne, a central figure in Congolese public life��for��decades��and��who had��noticeably��entered politics as a staunch anti-Lumumbist��in 1960).

Contradictory appropriations of Lumumba���s memory are nothing new in the Congo. However, in��my contribution��to recent special issue��of the journal��AFRICA��on student politics, I show how Congolese students in the 1960s succeeded in mobilizing��Lumumbism��to promote a cogent project of radical transformation for the young nation (in ways that contrast with the ���consensual��Lumumbism��� in today���s political class).

Before the death of Lumumba, most of the students who had taken part in politics had done so from a position of self-proclaimed moderation. They emphasized their educational credentials and expertise as the source of their political legitimacy and criticized politicians like Lumumba for their ���populist excesses.��� But the assassination of Lumumba created a shock that shifted political outlooks within student circles.

Students became much more aware and critical of the colonial matrix of higher education and more generally of the necessity to further decolonize Congolese society. After Mobutu came to power in 1965, he coopted many student activists and their ideas. There is no doubt about Mobutu���s duplicity in all of this (and he also violently repressed student��movements��while trying to��capture��their��aura), but his engagement with student political radicalism resulted in a real program of cultural decolonization.

A major element in the students��� attraction to the figure of Lumumba in the 1960s was his worldwide aura as an icon of liberation. The assassination of Lumumba had created extremely strong emotional reactions around the world, and through their association with��Lumumbism, students entered a field of anticolonial left cosmopolitanism.

With Lumumba, Congolese students accessed an international political space where the language of third-worldism, pan-Africanism, non-alignment and a diversity of socialist idioms allowed them to engage political constituencies around the world. By contrast, the production of history around Lumumba today is more cacophonic and fragmented.

It is striking to note for instance that on June 30 of last year, the day when Brussels officially inaugurated its Lumumba square,��Sindika��Dokolo���s��Congolais��Debout��movement organized a large rally in the streets of the Belgian capital to demand Kabila���s immediate departure from power.��(Dokolo��is a rich businessman whose fortune derives from his father���s business activities in the Congo under the Mobutu regime and from his own connections in Angola as the husband of billionaire Isabelle dos Santos, the daughter of former autocrat President Eduardo dos Santos; the fact that��Dokolo��tried to profile himself as a sworn opponent of Kabila���s��regime of��generalized corruption was��therefore��maybe��not without contradictions).��Dokolo���s��rally and the inauguration of the Lumumba��square suggested different political priorities.��The Afro-descendent activists who had lobbied the city council for the creation of the Lumumba square��had��worked closely with a Belgian left party��known for��supporting��the Kabila��regime��in the name of anti-imperialism.��Many of��of��these activists��defined themselves as Afropeans,��claimed inspiration from Latin American��decolonial��thought, and��revisited��the colonial past to denounce ongoing racist structures in Belgian society.��By contrast, the people who marched with��Dokolo��were both much less interested to participate in Belgian political processes and memory debates, and much more intractable in their opposition to Kabila.��They��acted as members of the Congolese diaspora��with their minds set on immediate change in the Congo.��The separation between these two groups��was��in no way��absolute.��Dokolo��and the anti-Kabilists��actually stopped by the Lumumba square before the beginning of��their rally, but the gaps in political imagination and praxis were not less clear.

There may not be equivalents today of the third-worldism��and anti-colonialism that empowered Congolese students��in the 1960s��and allowed��them to use memories of Lumumba to��fight politically at home while forging��connections with like-minded activists abroad.��Yet, Lumumba���s afterlife is certainly not over.��His name continues to inspire new generations.��In the Congo as well, despite the various appropriations of��Lumumbism��by members of the political establishment,��Lumumba remains a figure of liberation and of resistance to the oppression of power.

April 7, 2019

Back to class

Car guards in��Maboneng, a hipster neighborhood in Johannesburg. Image credit Francisco Anzola via Flickr (CC).

South African political discourse is scattered with uses of the word ���class.��� Whether it is referencing the plight of a South African working class, or the shrinking of South Africa���s middle class. Its widespread use captures that different social categories exist, but these are frequently being framed only through race. Little popular effort is made to understand what the nature of those categories are, what determines them, and how they relate to each other, if at all.

���Class��� comes with a cluster of different meanings. In South Africa, the interpretation that reigns views class as a hierarchical scale, measuring given attributes such as income, education level or occupation. In this arrangement, the different positions only have quantitative content; sometimes arbitrarily defined. Hence, those belonging to a ���middle class��� might literally be taken to be those earning the median income of a country, with the upper or lower class formulaically placed above or below that. Class formations are estimated around these markers.

For the late American Marxist sociologist Erik Olin Wright��this is a��gradational��concept of class, where classes are like different floors of an apartment building: what distinguishes them is that by some factor (in this analogy, levels of a building), one class is simply what the other is not. As categories, their proliferation is mostly self-contained. For example, anyone living on the third floor of an apartment building is perfectly capable of living their lives without ever meaningfully interacting with those living above or below them.

So, where there are inequalities between categories, one���s excess is not understood as having something to do with another���s lack. Policy interventions targeted at uplifting those who lack, is framed in the language of��disadvantage��and focused on��giving those deemed to be disadvantaged the hallmark attributes of those who aren���t. In recent years, this thinking has found expression in the rhetoric of��classism, a kind of class-based prejudice or discrimination. As the American literary theorist,��Walter Benn Michaels,��neatly phrased it, ���to eliminate classism- [is] to eliminate people���s obstacles to success, [to] give poor people a chance to become rich.���

In South Africa, one of these attributes is education. The most intense political struggle in recent South African history is the #FeesMustFall��movement. It continues to rally (with understandable fatigue) for free tertiary education. In a country facing the challenge of mass youth unemployment, a competitive job market demands that unless one seeks joblessness, a university education is crucial. Professional employment is thus seen as an emancipatory ticket for those whose backgrounds are poverty and destitution. Bestowing more young people with university degrees becomes an instrument for creating a more just and equal society.

The trouble with much of the #FeesMustFall��discourse is that although rightly calling for free education, it nonetheless presupposes that��individuals��are first responsible for working hard to acquire the necessary high school qualifications to enter university, and assuming they do, only then will the barriers to their entry and stay (such as tuition, accommodation and textbook fees) be eradicated. From that point, it���s up to them to ensure that they graduate successfully to�� become a lawyer, accountant or engineer. Once there, their high earnings will��trickle down��to their families and neglected communities. The personal uplift of the graduate represents the uplift of the population. The problem is, extreme cleavages in South African society mean very few get to go to university to begin with.

Simply, university education should be free for��anyone��who wishes to go. The issue is that��when it���s lauded as a long-term solution to poverty and inequality within the very structure that sustains poverty and inequality��en��masse, it can���t help but smuggle in and reinforce the classic liberal myths of meritocracy. Too easily, South Africans narrowly view our unemployment crisis as arising because too many people lack professional skills. This misses how that is itself an outcome of the economic structure, meaning it���s questionable as to whether or not doubling the amount of university graduates��is something that the labor market could absorb, especially given that graduate unemployment is already high.

Given the circumstances, as much as we understandably view a university education as a useful��commodity��for having a shot at a better life, any real emancipatory and egalitarian project must additionally ask��why��people have different jobs,��why��some of those jobs are more economically rewarding than others and��why��having an education (and an ever increasing amount of it) remains the only way by which they can be acquired, and even so��why��so many are systematically excluded from the opportunity to do so.

Here is where understanding class as a��social relation��is illuminating. Olin Wright provides an integrated approach to a relational concept of class��by drawing from Karl Marx���s account of class as derived from production relations characterized by exploitation and domination, and Max Weber���s account of class as derived from market relations characterized by opportunity hoarding. What undergirds both conceptions is the notion that class is chiefly a social relation. To simplify it, consider siblinghood as a social relation, in that someone can���t be a sibling unless they have a brother or sister.

Unlike siblinghood, these relations matter because they imply relations of concrete power. To occupy a certain class position means to have varying degrees of control over economic resources in society. In the Weberian tradition, one way this control is exercised is over access to economic opportunities like high paying jobs. The ability to be in a high-paying job, is causally connected to the status of others being in low-paying jobs. By way of social closure through exclusionary barriers to those jobs such as needing strong educational credentials, their special and rewarding status is protected, and a ���middle class��� is formed.

For Marx, the central division is created through property rights that afford capitalists exclusive control over the means of production. Broadly speaking then, the class structure contains capitalists who are defined by control over the means of production, the middle class over skills and education, with the working class excluded from both. But as Wright astutely observed,��these positions dictate not only what is materially distributed, but also what activities are possible.

Although one might be lucky��enough to have a high-paying job as a management consultant in some high-rise building in��Sandton��(Johannesburg���s financial center), they are nevertheless dominated because the freedom to fully determine one’s own ends is absent. Private control over the means of production means people have to submit themselves to the labor market to perform labor deemed necessary by those controlling the means of production. People don���t choose jobs that will make them most fulfilled, but ones that will help them comfortably survive. The overwhelming majority of our days are spent availing ourselves for work we are compelled to do by subordinating ourselves to the interests of capital, and let���s be honest, most people��(correctly)��hate their jobs.

Getting a better job, or a better position in a firm might lessen the extent at which someone���s daily activities are controlled, but in all cases, it still involves exploitation. Because��the chief interests of the property-owning and shareholding class is maximizing the return on those investments (in an unforgivingly competitive environment), the value of work performed by employees is ever the more appropriated way to safeguard profits.��It’s the reason why in spite of labor productivity steadily increasing throughout the years, real wages have continued to stagnate.

Ahead of the May 2019 elections, South Africa���s main political parties are making a pivot towards young people, prioritizing their concerns such as free education and packaging it in the in the popular language of identity emerging from #FeesMustFall��and #RhodesMustFall. During this moment, the youth���s proficiency at using social media as an arena for agitation established them as a constituency capable of dominating media coverage. Combined with there being�� 6 million people under the age of 30 yet to register, it���s obvious why political parties are giving them special attention.

Still, polls show that young South Africans overwhelmingly��intend to vote��for the ruling African National Congress (ANC). At face value, it makes sense why many would find the��ANC and in particular its president Cyril��Ramaphosa, appealing.��Ramaphosa��strikes a lot of South Africans as a��capable technocrat��able to usher the country back to political and economic stability, adept at bringing both unions and businessmen to the��negotiating table. But considering the ANC and its many sins, not the least��of which is its dismal record on free education, how did the once radical, anti-establishment rhetoric of the university steps so quickly go back to viewing the establishment warmly? This double-take is especially puzzling for a group of South Africans��unbeguiled��by age-old and deep-seated attachments to the ruling party.

It is here where the class analysis proves insightful. For Marx, the history of the world is the history of class struggle, which meant that, ���it is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.��� Crudely stated, Marx believed that people���s material, economic conditions, is what drove their ultimate ideas about the world. Therefore, people���s political and economic interests are at once closely determined by their prevailing position within a class structure.

In its 25 year reign, the ANC���s rule has mostly preserved existing social relations. While basic service provision has enormously expanded, striking class inequalities abound.��Ramaphosa��will likely hark back to former president Thabo Mbeki���s neoliberal policies and salvage the middle class that Jacob Zuma���s years of personal accumulation squeezed. For the young South Africans in the midst of their university studies or already in the halls of corporate South Africa, a��Ramaphosa��presidency presents the renewed strength of the professional class, and the security of career mobility within it.

That said, other young South Africans find resonance with the left-leaning Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). This, despite many of them also being located in more or less the same class position as those who would favor the ANC. While these young South Africans have the right consciousness, it���s justifiably questionable as to whether or not the EFF gives them a credible voice. Julius Malema is the EFF leader and a seeming advocate for the working class, who at the same time has close and acknowledged ties to dubious characters involved in South Africa���s illicit tobacco trade, on top of other high-ranking EFF members being embroiled in tender fraud and pyramid schemes designed to swindle the poor.

For a while now, South Africa���s��leadership can accurately be described���using terms made fashionable by American writer and activist Glen Ford (of��Black Agenda Report)���as a black (mis)leadership class.��In a��talk��given at the Riverside Church in Harlem, whose pulpit has been graced by both Martin Luther King Jr and Nelson Mandela, Ford had this to say about America���s own Black (mis)leadership��class:

It is a class that sees its own personal, financial and societal interests as being synonymous with the progress of black people as a whole. This class, does not seek transformation of society, it seeks only, their own elevation within the existing structures. The rest of black America, as far as they���re concerned, is supposed to applaud their individual success, and we���re also supposed to call that black progress, no matter what is actually happening to the masses of black people at the bottom. It��is the politics of putting black faces in high places, and to hell with those of us stuck at the bottom, or, those of us who are below the bottom.

It���s cynical to say, but what���s true for a lot of our political leaders is that what they want is power; to��attain or preserve it. Political power is not a means to an end, but the end in and of itself. Beware the politician whose overwhelming ambition is to get elected, or as Weber warned in��Politics as A Vocation, who ���live off��� politics. Regardless of where��their ideological commitments lay, any politician whose main interest is in entrenching the position of the political elite, and not transforming it, must be called exactly what they are: a reactionary.

In fact, as sociologist��Karl van��Holdt��recently argued, corruption and political patronage in South Africa are themselves processes of class formation. Where the established White-controlled private sector fences opportunities for accumulation around its own deeply-rooted networks as well as increased globalized��financialization, a counter political-economy has emerged where jobs and opportunities through state owned enterprises and state projects are more accessible routes for business and entrepreneurial pursuits, all the while cloaked in the language of ���radical economic transformation.���

This turn was made possible by a political moment substantially but uncritically preoccupied with the politics of identity and��difference. The EFF���s race-first posture, for example, maligns White South Africans as irredeemably racist, asserting that their political and economic interests coalesce around that fact��qua��their whiteness. In the popular political imagination, this conversely suggests that Black South Africans equally possess uniform political and economic interests. Racialized identity, is falsely��conflated��with political constituency- leading to the idea that a middle class, Black voter for the center-right Democratic Alliance (DA) is somehow betraying their interests.

Believing that the political and economic interests of Black South Africans naturally align further depoliticizes South African politics, not only in the favor of those claiming to champion a radical vision (to mask fantasies for power or enrichment), but for those trying to obstruct a radical vision as well. A vote for the ANC might as well be a vote for the DA.��Barring their differences on affirmative action and land reform, they���re both hitched to a neoliberal economic path combining economic austerity with reigning in the power of trade unions. Why people��don���t��vote for the DA, is because it���s still perceived��as a White party, even though the DA is set to wither in size come May as White South African liberals hedge their bets on��Ramaphosa.

Make no mistake, this isn���t to claim that concerns around race, gender or sexuality are irrelevant. Instead, it���s to caution against a false consciousness that gradually comes to see these categories as fixed and static, rather than contingent upon history��and socially constructed ��� the former view producing those categories in the first place, when the goal of anti-racism is to eventually transcend them, just as a goal of socialism is abolishing class structure. Viewing everything principally through the prism of identity obfuscates how class positions beget sharply different political and economic interests, which if ignored, can only ever maintain economic inequalities.

Neoliberalism is perfectly competent at sweeping up identity politics for its survival.

For instance, there was a bit of a lament earlier this year when then CEO of ABSA, Maria Ramos (she also previously served as director-general of the national treasury and her spouse is former finance minister, Trevor Manuel) announced that she would��be retiring, meaning that there would be no female running any of South Africa���s 40 largest listed companies on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Instead of taking issue with the fact that Ramos��pocketed��R37.6 million in the 2017 financial year thus earning fifty one times more than the average��R600 000��a year salary at ABSA, Black twitter focused on how this wasn���t real empowerment plainly because Ramos is not Black woman.

Young South Africans have become nascent professionals with some authority over other workers, more control over what work they do and how they do it, and real opportunities to earn their income outside of wages by organizationally ascending –�� at this point their choice sets and powers are much different from an ordinary, mostly Black, wage-laborer. This locates them in a��contradictory class position, one that has features of both labor and capital, that dominates as it is dominated. It is for this reason��that inasmuch as the identity politics moment has foregrounded crucial complaints about recognition and inclusion, without a firm understanding of class politics they also risk distancing a lot of young South Africans from the bigger working classes.

It��does so through a political mode of�� ���wokeness��� that���s mainly bothered by discursive transgression. This makes forging solidarity (not ���allyship���) with the (Black) working class majority difficult, for their systemic miseducation often means that they exhibit greater degrees of social conservatism in ways many of us urban, culturally liberal types now find unacceptable. Once again, it holds��individuals��as primarily responsible for shaping their attitudes, where a failure to display the correct etiquette warrants censure. Appraising education in the form of ���unlearning��� as the leading engine of social change cruelly overlooks how pervasively structured and overdetermined by their material and ideological circumstances��all��individuals are. In doing so, it limits the scope and reach of its activities and concerns to elite spaces like universities and corporate workplaces.

Any serious Left project must accordingly then target structures and not people. The heart of Left politics throughout history has always been complaining not about��who��gets assigned into certain positions, nor simply about what people��say, but about paying attention to��why��those positions exist in any case, which in turn drives what people do and say. As the Guinea-Bissauan and Cape Verdean revolutionary��Amilcar��Cabral once eloquently said on the topic of racism, ���Many people lose energy and effort combating shadows. We have to combat the material reality that produces the shadow.���

In France, the criminally underreported��gilet��jaunes��is illustrating what a cross-sectional solidarity that rises above the initial challenges of cultural difference, might look like. The discontent first erupting as general working class anger over Emmanuel Macron���s presidency has graduated to a movement with a revolutionary vision for French society. Admittedly, any movement with a vague substance risks politicization by right-wing elements, and true enough, the French establishment slandered them as a mob of fascistic and xenophobic ���troublemakers.���

But persisting now in its sixth month, the movement has incorporated students and trade unions to crystallize a once aimless rage into a��movement��that identifies as�����neither racist or sexist or homophobic��� but instead

proud to stand together, with our differences, to build a society based on solidarity. We are enriched by the diversity of our discussions, as hundreds of assemblies develop and propose their own demands.��The[se��demands] have to do with real democracy, with social and tax justice, with work conditions, with environmental and climate justice, with the end of discrimination.

At the moment, a South African Left outside of the EFF remains dispersed and fragmented. Parties with trade-union origins like the Workers and Socialist Party (WASP), as well as the fledgling Socialist and Workers Revolutionary Party (the SWRP, an offshoot of the National Union of Metalworkers South Africa), adopt the same militant Marxist-Leninism shared by the EFF.�� But unlike the EFF, they lack a Black nationalist slant and find themselves unable to exude youthful appeal, remaining associated with the statist-authoritarianism of the failed Soviet experiments. Worryingly, the freshly launched Capitalist Party of South Africa (blasphemously abbreviated as the ZACP, a clear reference to the now hapless South African Communist Party)��has gained strong visibility on social media, articulating a clear albeit woefully misguided vision for South Africa.

Capitalism in South Africa is failing. This is evident in South Africa���s extreme inequality, mass unemployment, underemployment and precarious employment. Widespread poverty persists as profit-serving automation knocks, while climate-change catastrophe ravages our neighbors. Hardship and despair finds expression in crime and violence, with poor and working class women and children mostly at the receiving end. South Africa must urgently embrace a fact that is being acknowledged elsewhere: the economy is fundamentally broken, and needs desperate restructuring.

This is where the state of the Left measures up embarrassingly against the state of the ruling political and business elite. In the midst of the State Capture Commission of Inquiry (a public inquiry into government corruption under former President Jacob Zuma), many expressed shock when Angelo��Agrizzi, former COO of BOSASA (a government contracting company), openly admitted that he was racist. It was just unthinkable that the political elite could aid racist capital in their accumulation. But capitalism is driven by a logic that���s indifferent to prevailing cultural relations. The bourgeoisie becomes the most organized, capable of uniting admitted racists and those who once fought them. Unless challenged,��no solidarity is stronger.

Besides trade unions defending South Africa���s dwindling traditional, industrial working class, class struggle is undertaken by NGOs and grassroots movements who only have capacity to organize around single-issues of pressing and immediate concern to those they affect. So,��Abahlali��baseMjondolo��(the shack dwellers) fight against evictions and for affordable public housing. The��Amadiba��Crisis Committee fights against profiteering mining companies threatening to deprive them of their communal land, and for other communities who haven���t witnessed the benefits of mining. Equal Education campaigns for quality primary and secondary education, while The Casual Workers Advice Office works to protect neglected but growing in number casual-laborers, like domestic workers, who lacking a site of organization are especially vulnerable.

At some point in his book, Olin Wright makes mention of a poster showing a working class woman leaning on a fence, with text saying that, ���Class consciousness is knowing which side of the fence you���re on. Class analysis is figuring out who is there with you.��� For too long, South Africans have eschewed a material awareness of their respective economic positions relative to others, and the divergent collective interests generated by the economic and political order.

The future of South Africa���s Left demands a renewed working class movement, one that works tirelessly to develop worker���s capacity to transform and democratize the economy. This is necessary to ensure that whatever alternatives become possible have at their core a democratic, hardworking base, capable of resisting the fierce fight that finance capital will wage, and to guarantee that progress doesn���t come with the repression and dogma that���s characterized other failed experiments throughout history.

There��are no quick fixes to eroding capitalism. A rejuvenated Left demands mass participation and unity, and that comes from being willing and able to draw from all sections of society.��#FeesMustFall��in 2015 showed glimmers of how a well-organized and engaged youth could form a multi-racial, class-cutting coalition of the kind that resembled the United Democratic Front of the 1980s, a non-racial coalition of workers, religious leaders, and students, mobilizing successfully towards the end of apartheid.

South Africa���s political and economic situation is tremendously bleak. While socialism has long been dismissed as utopian, what���s really utopian is believing that after 25 years more of the same will bring something better. Many are right to call for radical economic transformation, but it has to be pursued by a strong and unified Left, one that doubles down on the practical while emphasizing that in liberating us all from class domination and exploitation, socialism deepens democracy, unlocks freedom, and replaces��alienation with social bonds truly able to realize a non-racial, non-sexist and non-homophobic society.

April 4, 2019

How to film a revolution

revolution and solidarity.

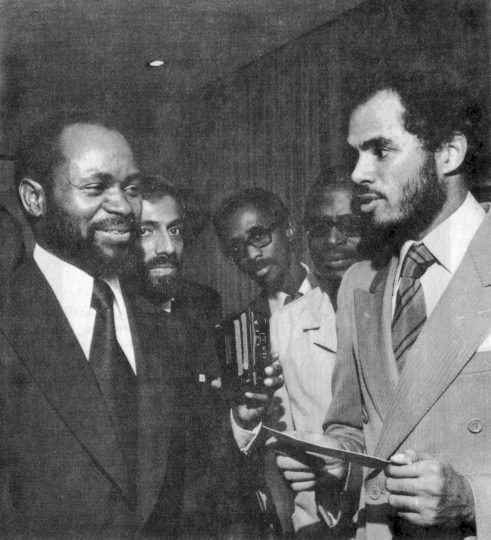

Samora Machel and Robert Van Lierop at the United Nations in 1977. Photo courtesy of Robert Van Lierop, credit Machel Van Lierop via the African Activist Archive.

A��dark-skinned man in fatigues��tiptoes across a��log��amidst dense��forest, automatic machine gun slung over his shoulder.��A��South African accented voice reports with��news anchor���s smoothness on the 1971 uprising in��New York���s��Attica prison. Armed men and women wade through��a��stream as��the��voiceover��shifts to discuss��the��expansion��of��the��liberation wars in Southern Africa. This is how��African��American��filmmaker��Robert Van��Lierop��introduces��the��audience to��FRELIMO��(Frente��da��Liberta����o��de��Mo��ambique, or Mozambique Liberation Front),��in his��1972��documentary,��A Luta Continua��(The Struggle Continues). These��soldiers��are��fighting��the Portuguese military for control��of��Mozambique.��But it���s��clear in the opening scenes that their��struggle��has meaning for��battles��against racism��and exploitation��the world over.