Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 222

April 17, 2019

Voice of the Cape

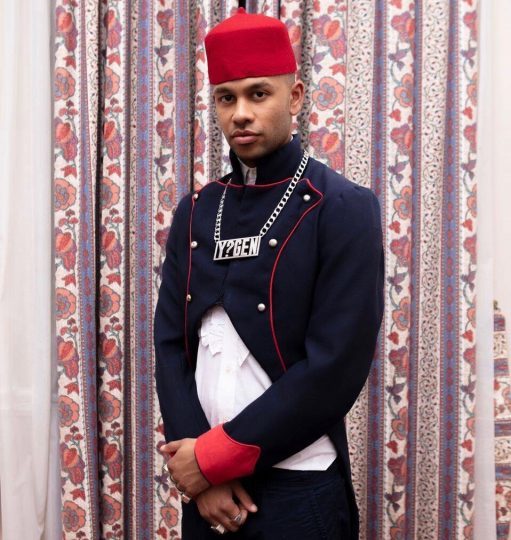

Boeta Shaakie and YoungstaCPT. Image credit YoungstaCPT.

A clock ticks. A slow, but augmenting stream of traffic echoes in the distance as the��athaan, the Muslim call to prayer begins. A young man, who we recognize as the rapper��YoungstaCPT��aka Riyadh Roberts, greets a passer-by he encounters along a bustling road. A street vendor in his distinct Cape sing-song accent attempts to entice pedestrians to buy his produce.��YoungstaCPT, arrives at a home, to a ���khutbah��� (sermon) in full swing. A group of men passionately debate the state of affairs within their communities on Cape Town���s Cape Flats. The latter refers to the collection of lower middle class and working class townships and suburbs where the majority of the city���s mostly��Coloured��residents live. High levels of violence, grinding poverty,��the highest��murder��rate in South Africa��and the frustration of youth living in this bleak environment, dominate their discussion. They mull over possible solutions before��YoungstaCPT��is heard asking his grandfather,��Boeta��Shaakie��Roberts, his thoughts. ���It���s very disappointing, what���s happening with the youth��� says��Boeta��Shaakie. ���But this problem can be rectified,��� says the old man.

This is, ���Pavement Special,����� the first track on��YoungstaCPT���s��debut album ���3T.���

Boeta��Shaakie���s��appearance on the first track is not a novelty; he narrates the album through snippets of conversations that Roberts recorded back in 2012. Containing 22 tracks, ���3T��� introduces us to the nuances of life in Cape Town and the experiences of many young��Coloured��people living in post-apartheid South Africa. It also gives an intimate window into the artist���s personal and emotional headspace.

In 1652, the Dutch settled in the Cape of Good Hope with the intention of setting up a refreshment station, however this evolved into a colonial expansion of the region. Swiftly, they began importing slaves for labor purposes, one of the first slaves to arrive was in 1653 from Batavia, now known as Jakarta. The indigenous Khoi people largely resisted the colonizers attempts to change their nomadic pastoralist traditions, and the Dutch also heavily relied on them for trade purposes. As a result, slaves were mainly imported from the Indonesian Archipelago, a��region already impacted by the Dutch colonial expansion, whilst other slaves were brought from different parts of Africa (mostly Madagascar and Mozambique) and some from South Asia. The Cape Colony rapidly became a cultural melting pot���a new creole culture emerged with the mix of cultures, ethnic groups, languages and religions now mirrored in the offspring of these groups. These people eventually became labelled as ���Coloureds��� by the colonial state and their new creole language of Afrikaans was born. Eventually comprising around 8.8% of the national population, Coloured people are a national minority, but make up a majority in Cape Town and the Western Cape province; they also make up the largest group of Afrikaans speaking people in the country. During the racist policies of the Apartheid era, Coloured people weren���t favored by the social and economic hierarchy which left whites at the top of the triangle, nor were they considered on the bottom, the way other Black people now referred to as Africans were placed. Post-Apartheid, the African National Congress (ANC) instituted a policy of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) or affirmative action designed to redress the economic injustices of the past and give people of color economic privileges that white people already have. Some Coloureds claim this policy is applied on the reverse order of preference based on the original hierarchical triangle of the old system, placing them���once again���somewhere in the middle.

Cape Town happens to be the birthplace of hip hop in South Africa. The genre���s local origins can roughly be traced back to the early 1980���s where music and other elements of the hip hop culture including graffiti and breakdancing were also embraced. The earliest hip hop groups in the city and the country, such as Black Noise, Prophets of Da City and Brasse Van Die Kaap, were all Coloured and from the Cape Flats. Overwhelmingly, their lyrics and appearance were politically charged and socially conscious. This hip hop scene in Cape Town was overwhelming independent, but was eventually displaced as hip hop���s center by a new commercial scene, which evolved in Johannesburg. The genre evolved and expanded through other cultural and linguistic influences, an example of this is artists beginning to rap in other languages such as Tswana or Zulu. A new hip hop scene is now also beginning to emerge in Durban, on the country���s east coast which also adds a nuanced layer to the country���s hip-hop scene.

YoungstaCPT has principally been viewed as a Cape Town and Coloured rapper. He has been criticized by some outside of the Cape, for not presenting himself as a black artist, as say AKA. What is clear, however, is that YoungstaCPT brings nuance to the Black experience by not simply looking at it through a homogenous lens of blackness. As for being associated with Cape Town, YoungsaCPT briefly relocated to Johannesburg where he built a reputation as a freestyle rapper, for dominating on other people���s songs, and working with producers such as Ganja Beatz. He opted to return to Cape Town and work from there. YoungstaCPT tells me that he wanted to change the scene in Cape Town and the way people perceive hip hop from the city, something he hopes to achieve with ���3T.����� It is a testament to his influence that he won the South African Hip Hop Music 2017 Award for lyricist of the year. The competition that year included��the legendary Stogie T��and��young rapper Shane Eagle, both rappers made in Johannesburg and national stars. (On Instagram, Stogie T welcomed the release of ���3T.���)

YoungstaCPT is a musical prodigy of sorts, having dropped an epic 30 mix tapes and several EPs.��It is surprising that ���3T��� is his debut album.

YoungstaCPT. Image credit Imraan Christan.

YoungstaCPT. Image credit Imraan Christan.An ambitious artistic feat, ���3T��� does an impressive job of reflecting a range of themes including colonization and residual mental slavery. In addition to drugs, the competitive nature of the hip hop industry, jealousy, colorism, the appropriation of Cape Coloured vernacular, celebrating women, among others. There���s also YoungstaCPT���s own personal struggles with balancing his faith (he is Muslim) and also succumbing to human vices.

Musically, the song line up captures the artist���s diverse hip hop influences. ���VOC��� (the title is a play on the Dutch multinational which introduced colonialism to the Cape Colony, here reshaped as ���Voice of the Cape���). Meanwhile, ���To Live and Die in CA��� (CA, the local car number plate, stands for Cape Town) clearly reflects the nostalgia for 1990���s West Coast hip hop and rappers such as NWA and Snoop Dogg. Tracks like ���Sensitive,��� ���Old Kaapie��� and ���Mother���s Child��� have a trap sound resembling Migos and Drake. Finally, tracks like ���Just be Lekker��� and ���Kaapstad Naaier��� reflect the eclectic beats preferred by Kendrick Lamar.

���Young Van Riebeeck��� (YVR), the first single released from this album, came out in November 2018. Roberts gave us an exhilarating jolt, whetting our appetite to what was to come.�� The title of the song stems from a tongue in cheek play on the name,��Jan Van Riebeeck. A Dutch navigator and the colonial administrator for the Dutch East India Company, Van Riebeeck was considered by whites as the founding father of modern-day Cape Town and White Afrikaans speakers.

His raps also reflect common experiences of a sizeable minority, the Cape Coloured community (and within this group the Cape Malay community), a demographic that often feel overlooked and underrepresented within the broader society. YoungstaCPT illuminates important issues to a mainstream audience who wouldn���t necessarily have access to this information otherwise. He is shifting and re-shaping the dialogue on identity politics.

Roberts tells me that the idea behind the song came from years of research and self-realization with regards to the colonial history of Cape Town, slavery and the consequential legislated racial segregation policies of later years which officially ended in 1994.

A principal policy of Dutch colonizers was to segregate races and religions, which the British, while they abolished slavery, continued (It is a little known fact that the British introduced the pass system to control the movement of slaves). In 1910, years after the Anglo-Boer War, when Whites unified to govern South Africa at the expense of the Black majority, the Black population��which included Coloureds, began to be stripped of more of their land. In 1948, the National Party won Whites-only elections and introduced Apartheid nationwide, this included aggressively enforcing a series of laws which classified people into racial categories with Whites at the top, stripping people of their political rights, dictated where people could live (Group Areas Act) or spend their social time (which beach they could swim in or which parks their children could play in), go to school (the quality of education they could have access to), what kind of professional work they could do and how much they could earn. YoungstaCPT���s own family suffered from these racist policies. Boeta Shaakie, originally from Simon���s Town, at the southern end of the Cape Peninsula, married YoungstCPT���s grandmother, moved to central Cape Town to live with his wife���s family who were living in District Six, a multi-racial, mostly Woloured area in the city center. The family was forcibly removed from District Six by the state, who had declared it a White���s only area in the 1960���s. They ended up in Ocean���s View, a Coloured township close to Simon���s Town.

���I realized how heavily ingrained the official Jan Van Riebeeck crest is in the culture of our society���the legacy of this colonizer is celebrated everywhere. It���s still the center of the official city of Cape Town���s coat of arms and it���s even embedded in my former high school, Wynberg Boys��� crest. There is a statue of Jan Van Riebeeck in the city center. People are desensitized, they���re blind to all of this���, YoungstaCPT tells me.

Wynberg Boys is a former white school close to where YoungstsCPT grew up. (YoungstaCPT was born in 1991, one year after the National Party began negotiating with the formerly banned African National Congress for a new political system for South Africa.��By then schools were slowly desegregating.)

Roberts expresses that his inspiration for the lyrics came from recognizing and acknowledging the past but flipping the narrative to re-imagine the future. He imagined a slave revolt, where a slave leads his companions and overpowers the colonial master, to take control of and re-define the future. He envisioned��the slave leader��not only��as an activist, but��also��someone who also embodies super human qualities to inspire young people to create a brighter future.

Taking Jan van Riebeek to the barbershop and cutting off his whole mustache

You was worried about the waves, I was worried about the slaves

Now you standing there amazed

Go tell the mense what���s my name

It���s the Cape crusader

Young Van Riebeek

YoungstaCPT���s artistry is markedly different from anyone in South Africa���s music landscape. His work is intricately connected to his lived experiences at the intersection of color, race, class��and religion. He reveals these nuances��in��his personal identity, shares his vulnerability with his audience by reflecting on his internal conflicts and personal struggles through his music.

Roberts is a practicing Muslim, and hails from a devout Muslim Cape Malay family; he was raised by a single mother and his grandmother was a madrassah (Islamic school) teacher. The rapper was born, raised and despite his ascent to pop and cultural icon status (the only Cape Malay male to do so), continues to live in the community he grew up in on the Cape Flats.

The term Cape Malay is generally used to describe a sub-group of people who also fall under the umbrella term Coloured people. Cape Malays are Muslims whose mixed ethnic ancestry includes Muslim slaves brought from the Bahasa Malayu or Malay speaking groups on the Indonesian Archipelago. Whilst Muslim slaves were brought from other parts of Africa and South Asia, the majority were from the Indonesian archipelago. With the result, the Malay language became the dominant language (prior to the emergence of Afrikaans, the new creolized language) of communication amongst Muslims and slaves who were extensively excluded from colonial education. The term Cape Malay became a formal state racial classification during the Apartheid era to define creole Muslim people from the Cape who were culturally distinct from Indian Muslims that were categorized as Indian. The legacy of this racial classification imposed on creole Muslims in the Cape still heavily permeates the fabric of society. Conversations around racial classifications in South Africa is highly political. In light of being a young democracy whose citizenship has access to more information, there is a movement of people with differing viewpoints to identity politics and labels who are opening up new dialogues to dissect and challenge the status quo.

YoungstaCPT is a co-founder of the ���Y? Generation Enterprise���, an organization started by young men from the Cape Flats. The organization heavily invests into social and professional programs to uplift youth in the area through music internships, music school tours and organizing community drives to raise material goods for low income families in the area. During our interview, he received a text message from his childhood best friend, currently serving jail time, requesting the rapper to recharge his cell phone credit. This passion for and sustained personal connection to the people and the region that prominently features in his artistry through his lyrics and visual aesthetic choices provides a cultural capital and authenticity that some local artists lack.

In a country still heavily racialized and economically segregated but also culturally divided post its first democratic election in 1994, Roberts��� music and voice contributes an important nuance to the contemporary discourse. The rapper is uniquely positioned within the South African music landscape, where he is broadly considered a mainstream star for his sound. However, his music cannot be divorced from underground hip hop. This is demonstrated by the nature of his lyrics which reflect the intersection of his various personal identities.

Roberts tells me that through listening to his favorite rappers Method Man and Redman as well as other rappers of the early 1990���s, from an early age, he became aware of the complex nature of personal identity and socio-political issues. He became increasingly drawn to this kind of music. With nostalgia, he remembers dragging his mother out to the local shopping mall to buy CDs and marvels at the fact that she permitted him to listen to certain songs despite some of their overtly adult themes. ���They would rap about drugs, gangs and at the same time about Jesus and going to church. I couldn���t relate to the going to church part, but I realized that what they were singing about were things that were happening all around me. Kids I was growing up and going to mosque with were also doing drugs and joining gangs,��� he says.

He wasn���t aware of the degree of his music���s influence till people started reacting positively and engaged with him through social media by tagging him in posts and Instagram stories as well as DM���ing him. His Instagram followers list organically grew from 12,000 followers to over 130,000 within the space of three years. He realized the reach of his music, and decided that it was important to use his platform to make a consciously positive difference to society.

���I���m aware that so many young people listen to me, when they don���t even listen to their parents. With this album, I want to help educate the youth on important issues within our society, inspire them to be proactive and give them hope for the future���, he tells me.�� He goes on, ���what they don���t realize is that it���s important to sit down and listen to our elders who have been through so much adversity. They have the knowledge to help us move forward in this life. Roberts becomes emotional, tears up, as he remembers his grandfather���s closing words in the album outro.

���Out of the dirtiest water, comes the whitest lily���all the lily needs is the water���s nutrients to survive. You have to look into the past and think of the benefits and the negatives���extract the good and make the negative a positive,��� Boeta Shaakie advises, near the end of ���3T.���

April 16, 2019

Laboratories for violence

Boko Haram burned villages and fields, from the UNHAS helicopter. Image credit Roberto Saltori via Flickr (CC).

In February 2019, the Republic of Chad dispatched a convoy of more than 500 men to Nigeria, in support of the fight against Boko Haram. The latter had grown in strength a few months before Nigeria���s February presidential elections, hence the support from Chad. In early March, humanitarian agencies were also alarmed by the forced return of thousands of Nigerian refugees��from Cameroon to territories allegedly occupied by Boko Haram.

Between 2017 and the first half of 2018, Boko Haram appeared to be on the decline. The heads of state of the Lake Chad sub-region (Cameroon, Nigeria, Niger and Chad) have repeatedly proclaimed Boko Haram���s defeat. In Cameroon, for example, at a presidential campaign in the town of Maroua, President Paul Biya triumphantly declared that Boko Haram has been pushed out of the country. Of course, Biya went on to win his seventh term as president of Cameroon and his supposed victory lap over Boko Haram was celebrated again at his inauguration in late 2018 as well as in his New Year���s speech in January 2019.

The trend of claiming victory over Boko Haram wasn���t limited to Paul Biya alone. President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria adopted the same approach, making the defeat of Boko Haram central to his re-election campaign which he won on March 6 2019.��President Buhari repeatedly claimed that Boko Haram was ���technically defeated��� and no longer controlled localities in the country.

However, the optimism of the leaders of the Lake Chad region���Buhari, Biya, Idris Derby of Chad, Mahamadou Issoufou of Niger���about the defeat of Boko Haram is today tempered by the resurgence of deadly attacks in the region. Boko Haram carried out multiple attacks on January 25, simultaneously in many localities including the villages of Goshi and Tourou in the Mayo-Tsanaga Division of Cameroon. Between March 9 and 26, about 40 civilians and soldiers were killed, more than 100 homes burned and several women kidnapped in a series of Boko Haram attacks in the Diffa region in Niger.

Contrary to the claims of the Nigerian president and his officials, Boko Haram is far from been ���technically defeated��� as there has been increased attacks on civilians in the northeast of Nigeria. Instances of attacks include the Metele attack carried out on three military bases in Borno state on November 17 and 18. Security sources stated that at least 44 soldiers were killed in the attacks and a large store of arms and military equipment carted away by the insurgents. These recent attacks are proof that the Nigerian President has failed to keep his 2015 presidential campaign���s promise to eradicate the jihadist group. The shadow of Boko Haram also hangs over the islands of Lake Chad, which has become the group���s new sanctuary.

While the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) created by the countries surrounding Lake Chad has gained significant ground in the fight against the jihadists, it is clear that this purely military response has failed to completely stem the violence. On the contrary, it has sometimes given rise to the sect���s pockets of resistance. Indeed, after each setback inflicted by the security forces, Boko Haram fighters retreat into the different dormant cells on the outskirts of Lake Chad to metastasize. The more they are harassed, the better they take advantage of porous borders to rebound.

The inability of the regional military forces to combat the Boko Haram insurgents, in our opinion, stems from the lack of will to adopt a broader approach including protecting civilian populations, as well as addressing the root causes of endemic violence in this region. A more robust approach would have brought together different stakeholders to fashion out a plan to protect people and communities. In the face of insurgent challenges, state forces must be aware of their commitment to respect human life and dignity. They must contribute to building peace and preventing future atrocities, even in the context of an asymmetric war against an invisible enemy. In July 2018; a short video of an ad hoc execution in northern Cameroon of two young women and their children, provided visual evidence of the abuses and crimes committed by certain elements of the military in the name of fighting terrorism.��These abuses have sometimes expanded Boko Haram���s pool of potential recruits. Indeed, in the 1980s, the forceful response of the Nigerian state led to the strengthening of the Maitatsine insurgency, which is seen today as a precursor to Boko Haram.

One of the ways in which the Boko Haram insurgency can be addressed is through the ���push-factors,��� addressing the underlying conditions that have��created fertile ground for Boko Haram recruitment, notably bad governance, endemic corruption, mismanagement, poverty and the state���s lack of legitimacy.��Today, corruption has become a way of life in both Cameroon and Nigeria, particularly within the army and police. Millions of dollars officially released to fight insecurity have actually fueled a vast system of ���makeshift��� funds for corruption.

This endemic corruption has created a vast ���underclass��� that for the most part has given up on democratic political solutions and instead relies on access to the looted ���spillover��� to assure survival. This ���underclass��� is prime recruitment fodder for Boko Haram recruiters. Stakeholders must recognize that if these issues are not resolved in a transparent manner, all other measures will only be temporary solutions. Failure to tackle inequalities and social frustration could eventually lead to the emergence of another insurgency.

Throughout its existence, the group has also exploited the Almajiri���s��system��of education. The countries of the Lake Chad region are characterized by the coexistence of two consistent schooling systems operating in parallel, and often oblivious of each of other: the western-style and the Islam-based systems. In Nigeria for example, despite the federal government efforts to integrate modern school curriculum into the Qur���anic school system, about 10 million children of primary and secondary school enrollment age still are not attending formal western schools. Instead, the majority of them are enrolled into the Qur���anic schools.

This situation is all the more problematic insofar as a western-style education is the only guarantee for promotion in the public service. In other words, the great mass of Qur���anic school graduates finds themselves unemployed. In this context, Boko Haram���s speech denouncing corruption and inequalities created by the postcolonial state has motivated popular support. States must find a way to create a bridge that would allow a graduate of the Arab school system to integrate Koranic schoolchildren into a government curriculum.

Finally, there is a need to define a concerted border policy and ensure the effective presence of state authority in some neglected areas, such as the Mandara Mountains or the Lake Chad Islands. The border areas have always been very important sites of violence in the Lake Chad Basin, due to the absence of state authority. Boko Haram���s thriving in border zones reveals the frontier as a space in which there is “an institutional vacuum,” manifesting what John Galaty calls ���an entropic theory of borders.��� Igor Kopytoff���s “internal frontier” model interprets such interstices between states as laboratories for the creation of new social and political forms, where mutability of border identities and the possibilities of wealth creation generated by arms are on offer, especially to young men. Areas like the Mandara Mountains are indeed places where the political state has often refused to exercise its full authority because of the profits that illicit relationships afford state officials. If states continue to be absent in these areas, we will witness ongoing violence even after the defeat of Boko Haram.

April 15, 2019

Bridging visual distance

From the series After Migration,

James Jean and Patrice Worthy, photographed in New York City, United States, 2016, wearing original designs from the fashion line Ikir�� Jones by Wal�� Oy��jid��.

Image credit Rog Walker for Ikir�� Jones ��.

The artist Alfredo��Jaar��has said that ���we are the sum of all the stimuli we receive,�����and certainly images, whether in the form of illustrations, videos or photographs, make up an influential portion of that stimuli.��In a world plagued by mass shootings, hate crimes, and the stubborn persistence of a range of discriminatory -isms, perception of social difference is critical for determining the relationships we have with each other.

Another Way Home,�� on view at Open Society Foundations OSF in New York contemplates the impacts of images in our lives. The exhibition is part of the Moving Walls series, an initiative of the Open Society Documentary Photography Project, which has been sharing socially-relevant documentary practice for 20 years. As the 25th iteration of Moving Walls,��Another Way Home��takes on the issue of migration by featuring eight projects created by 13 artists from around the world.��The exhibition, co-curated by Yukiko Yamagata and Siobhan Riordan,��can be viewed online��or��anyone in New York��can view it onsite until��July 2019 at Open Society Foundations�����New York offices.

From the series The Right to Grow Old. ���First as lookouts and later into full-fledged gang members, neighborhood children are groomed young by their brothers, cousins, and neighbors. The slow process of recruitment is only viable as communities have little in the way of alternatives for abandoned youths with nothing to lose.��� ��� Tomas Ayuso, San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

From the series The Right to Grow Old. ���First as lookouts and later into full-fledged gang members, neighborhood children are groomed young by their brothers, cousins, and neighbors. The slow process of recruitment is only viable as communities have little in the way of alternatives for abandoned youths with nothing to lose.��� ��� Tomas Ayuso, San Pedro Sula, Honduras.Image credit Tomas Ayuso �� 2017.

Working through the mediums of video, mural, newspaper and various modes of photography, each of the bodies of work offers nuanced interpretations of how migration effects families, communities and individuals���those who travel and those who stay behind. Whether through fashion photography representing African migrants as regal or virtual reality film deployed as a means to reunite families, the artists in Another Way Home��bring to the fore a kaleidoscopic array of perspectives that, in the past, have existed outside the frame of images recording migrants and migration. Indeed, one of the central elements of the Moving Walls selection process is demonstration of immersive connection with people and places featured in the works. Through those strong relationships, the nerve channels that link people to ideas of��home��are experienced and documented intimately by the artists.

Immense power rests with those who are the creators of art and media. This power may manifest in different ways,��ranging��from exploitation to cooperation. Having considered the contact zones of image-power associated with the exhibition holistically, Siobhan Riordan, Project Head of the Documentary Photography Project,��remarked to me that ���a big question that impacts every part of an exhibition down to the curatorial framework and process itself is, how do you decentralize power and whose voices are at the table every step of the way?���

One critical manner in which the question of power has been incorporated relates to how language is presented. In both the exhibition space and in the accompanying catalog, the languages of��the people featured��in each project���in this case Spanish and Arabic���are privileged over English as primary languages. English translations of project descriptions are available, though in situ you must actually lift the sheet of paper containing the primary language to see English text revealed beneath. In the��catalog, the primary languages are encountered first and the book must be turned upside down on the following pages for English to be read. These physical interventions can be seen as ephemeral simulations of migratory experience and��they��act as reorientations of language hierarchy.

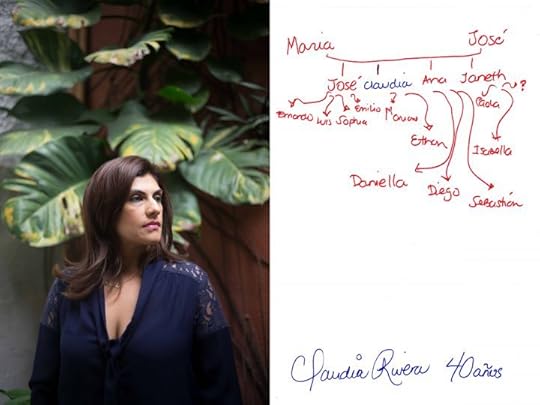

From the series Welcome to Intipuc�� City. Claudia Rivera, 40 years old, is a doctor. Her family immigrated to the United States in 1983 when she was seven years old to escape the civil war. After living for many years in the United States, she decided to return to El Salvador. Claudia���s hand drawn family tree includes family members��� names written in red for those living in the United States and in blue for those living in El Salvador. As the drawing indicates, Claudia is the only member of her family still living in El Salvador. San Salvador, El Salvador, September 2017.

From the series Welcome to Intipuc�� City. Claudia Rivera, 40 years old, is a doctor. Her family immigrated to the United States in 1983 when she was seven years old to escape the civil war. After living for many years in the United States, she decided to return to El Salvador. Claudia���s hand drawn family tree includes family members��� names written in red for those living in the United States and in blue for those living in El Salvador. As the drawing indicates, Claudia is the only member of her family still living in El Salvador. San Salvador, El Salvador, September 2017.At the level of the artists��� practice, when documentary works such as those featured in��Another Way Home��are generated through ongoing conversation and co-creation, the power embedded in art and media is distributed and the works more effectively represent the stories of the people being depicted. Within the exhibition, the��project,��Welcome to��Intipuc����City, displays portraits of people and domestic spaces in El Salvador juxtaposed with hand-drawn family trees indicating who has or has not migrated.��Powerfully, some of the family trees and portraits indicate only a single family member remaining in El Salvador, while images of homes reveal the marks of United States American culture on the landscape.��The artists behind the project, Jessica����valos, Koral��Carballo and Anita��Pouchard��Serra,��speak to bridging the distance between viewers and subjects of their work:

We live in contexts where audiences read less and less and opt for viral and content-poor publications. Images are powerful elements that allow us to approach that audience saturated with content and bring them closer to the protagonists.

The sentiment of closeness can also be found in The Right to Grow Old, a project by Honduran photojournalist Tomas��Ayuso. This project offers a poetic collection of images from Honduras, Mexico and the United States tracing the resilient lives of Honduran migrants in different stages of their journeys towards security, as they experience physical and social borders along the way. On the impact of images,��Ayuso��says:

With images that depict current issues in an in-depth manner we can develop empathy and understanding. Sometimes images become clarion calls and trigger social movements into action. Images that tell stories are crucial not only in societies, but at the local level and down to the individual.

From the series Live, Love, Refugee. ���I wish to become a dragon and burn the scarves and everything in that tent.��� ��� Kawthar, 16 years old, Lebanon. Kawthar was beaten and raped on her wedding night after being married to a 32-year-old Syrian man from a nearby refugee camp. Image credit Omar Imam ��.

From the series Live, Love, Refugee. ���I wish to become a dragon and burn the scarves and everything in that tent.��� ��� Kawthar, 16 years old, Lebanon. Kawthar was beaten and raped on her wedding night after being married to a 32-year-old Syrian man from a nearby refugee camp. Image credit Omar Imam ��.Though it exists permanently online, the exhibition itself could benefit from a few more public showings and events that would challenge new audiences to confront the works. Moving Walls does however go beyond a static show as the artists behind each of the projects are also given a Fellowship grant to continue their existing project or develop a new body of work. This aspect of Moving Walls is particularly powerful as it circulates their work outside the limitations of the gallery space, resourcing the artists to enhance the impact of their social practice, engaging further with their respective communities through their own public programming, book production, additional research and immersive content creation.

Through its adroitly designed display of documentary projects���which are accompanied by detailed information and captions, often with reflections from those appearing in images���the��Another Way Home��exhibition is effective in challenging the dominant regimes of knowledge that disparage migrants and migration.��The projects in the show��work to collapse distance and deepen the awareness viewers have of people in different migration contexts. Indeed, it is not images themselves which brand people as immigrants or refugees, rather,��that work is performed by ideological discourse��deployed for political means.��Depending on what preconceptions about migration issues viewers bring to the exhibition, the depth and care infused into the works can operate in different registers for conveying representation, critical (un)learning, and expanding and reshaping the internal image indexes that guide how we interpret the world around us.��In this��way,��Another Way Home��represents a model contemporary media initiative, as it transcends the exhibition walls by encouraging us to reflect on��how the images we encounter affect us, how we see each other and ultimately, how we may live together.

April 14, 2019

Frontiers of dystopia

Military members from the Cameroonian Armed Forces. Image credit Kyle Steckler for the US Navy.

���President��Biya��cannot be considered an equal of Mr.��Kamto, who is a citizen like everyone else, and must stop thinking himself otherwise,��� Ren�� Emmanuel��Sadi, Cameroon���s��minister of communication��and government spokesperson,��told��RFI��(Radio France International)��in an��interview��last month.

Maurice��Kamto��is a��former distinguished law professor at the University of��Yaounde, and, more importantly,��leader of the��Mouvement��pour la��Renaissance du Cameroun��(MRC).��The MRC��was formed in 2012 and participated in��legislative��elections the next year.��Despite performing��dismally, winning just one seat in Cameroon���s National��Assembly, Kamto���s��emergence as an opposition figure has rankled the ranks of the regime in power.��At present,��Kamto��and��several��MRC��members��are in��detention at Yaound�����s��Kondengui��prison. A��military tribunal has��charged��Kamto��and hundreds of his supporters with�����rebellion,��������hostility against the homeland,��� ���sedition,��� ���incitement to insurrection,��������offense against the president of the republic,�����and�����the destruction of public property,��� among other offenses.��If��found guilty, the accused��could��face sentences ranging between five years in prison to��the death penalty.

Kamto��and his comrades��� predicament is fascinating as his party���s demands are far from radical. In any functional democracy���what��Biya��claims Cameroon is���they��wouldn���t be in detention today. Kamto, who by��most standards��is a political moderate,��is a lawyer who��served on an International Law Commission of the UN from 1999 to 2016, and one of two representatives who argued��the Cameroon government���s position in the territorial dispute with Nigeria over the��Bakassi��peninsular. The International Court of Justice ruled in Cameroon���s favor in 2002.��Kamto���s��role led to his appointment��to a senior post in the country���s��Ministry of Justice��in 2004. However, he would resign in 2011��without providing any��singular��reason��besides stating that his was a patriotic act meant to signal his commitment��to continue working for the rebirth of a more prosperous Cameroon.��One year later,��he��launched��the MRC as a convergence of a handful of small political parties.

The MRC leaders were arrested on January 29th this year, two days after dozens of his party members were targeted with live ammunition in the port city of Douala for participating in an unauthorized protest march against the stuffing of ballots and other irregularities that marred the recent presidential elections, which��Kamto��claims he won.��In Cameroon, permissions for such public gatherings are granted by administrators appointed by the regime in power. Most of these administrators are card carrying members of the ruling Cameroon Peoples Democratic Movement (CPDM). Following the repression on January 27th in Douala, about 50 France-based Cameroonians vandalized the Cameroon embassy in Paris, replacing��Biya���s��portrait with��Kamto���s. The Cameroon authorities are claiming the MRC directed their actions.

Facing the most sustained challenge to his 37-year-old reign, the 86-year-old��Biya���s��new mandate is marked by deteriorating security across the national territory, including though not limited to a��three-year insurgency in the English-speaking regions where some Anglophones fed up with five decades of marginalization are fighting for secession; Boko Haram attacks in the Northernmost region and the Eastern region, rendered restive by armed groups from neighboring Central African Republic.

Ren�� Emmanuel��Sadi, a veteran of the��Biya��administration who��has held several portfolios in the last decade��(if you follow Cameroonian politics,��it���s him you���ll see defending��Biya��or pumping up his boss to Western media), was reacting to��Kamto���s��attorney,��Eric��Dupont-Moretti,��relaying��the request of his��client��to meet and discuss��the country���s political challenges��with President Paul��Biya.

Kamto��is the most recent figure in an exhausting list of political actors whose offer for dialogue with Cameroon���s president has been rebuffed publicly.

In his��RFI interview,��Sadi��used the occasion to remind Moretti that his role in the matter was confined to representing his client against the charges he���s been accused of��rather than�����posturing as a mediator�����and�����making��clumsy arguments and��surreal demands�����regarding the last elections.�����Everyone knows, including��Mr.��Kamto, that he didn���t and couldn���t have won the presidential elections,��� said��Sadi.

Despite the massive boycott of the elections in most of the��English speaking��regions, low voter turnout in the rest of the country, allegations of ballot stuffing and ghosts voters, the elections were declared free by the country���s electoral commission, which is dominated by members of��Biya���s��ruling CPDM, and fake observers whose affiliation with Transparency International were discredited even before the final results were announced.

Sadi��was speaking for a government that has returned to its pre-liberalization posture of the 1980s when state institutions like the judiciary and law enforcement were weaponized to silence political opposition to the increasingly repressive tendencies of��Biya���s��then young regime. Sadi��was talking to RFI,��the public broadcaster of France, the one permanent member of the UN Security Council that, many in Cameroon believe, holds the key��to overcoming the country���s��ongoing��political and security impasse. France has repeatedly protected��Biya���s��regime. For Cameroonians, one��phone call from the����lys��e��could��possibly��compel��the regime��to��invite its opponents to��the negotiating table.

The most amusing revelation in Sadi���s��statement to RFI happened while he was elevating Cameroon���s president above his political opponent of the moment, calling him an “ordinary citizen.” With that he managed to confirm the long-held notion that President��Biya��views himself as a monarch.

Of course,��Sadi��sounded assured, but the reality is the country���s rising debt, rotting infrastructure, youth unemployment,��ethnic and linguistic tensions,��political repression, and increasing insecurity on multiple fronts does not persuade keen observers that all is well. Sadi���s��boss might have scored another term under questionable circumstances,��but Cameroon today remains what late Poet��Bate��Besong��described as a country, ���jolted by the rascality of government customized role models who have allowed the allure of office and filthy lucre to push them to do the most unlawful, most immoral, most indefensible.���

Indeed,��Cameroon remains the post-colonial jigsaw puzzle that President��Biya��inherited from independence-era French ally,��Ahmadou��Ahidjo, who governed from 1960 to 1982. The similarities don’t end there, as Biya is certainly resorting to the repressive tendencies that characterized��Ahijdo���s��22-year rule.��If��Sadi��sounded like a relic of a bygone era, so, too, does the idea that dialogue with political opponents���be they Anglophone separatists, imprisoned former political allies, political opponents and ordinary citizens alike�����diminishes the president���s standing and stature. Yet the spokesperson���s posture is emblematic of the country���s recent backslide to a repression that many Cameroonians once believed was entombed alongside the martyrs who fell on the frontlines of the struggle for a more tolerant and liberalized country.

April 13, 2019

The politics of ethical deception

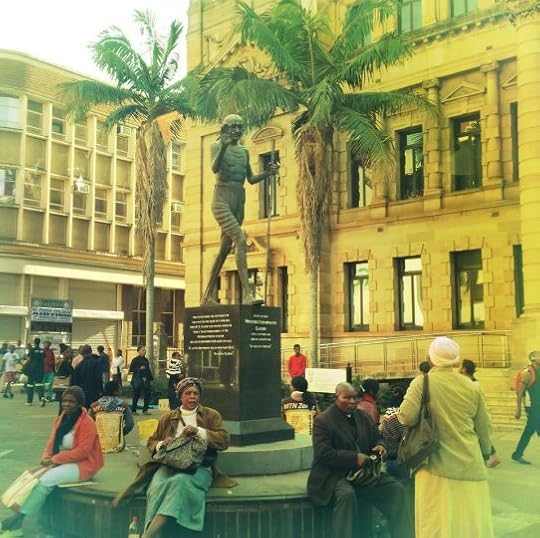

The Gandhi state in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Image credit Christine Henske via Flickr (CC).

Mohandas��Karamchand��Gandhi��keeps��making news on��the��African continent��as��the furore��over his statue in Ghana��or��the��proposed statue in Malawi��raise debates��over��his��attitude to Africans,��his belief in the redeeming qualities of the British Empire��and��his��defense of white minority rule in South Africa. In response,��there has been a virulent denial from those with a stake in Gandhi���s status as pioneering anti-racist fighter during his sojourn in Africa. If in India there has been an investment in myth of Gandhi as non-racial icon, in South Africa Gandhi also has his defenders. Most notably,��Ela Gandhi,��his granddaughter.

Ela Gandhi, 78,��is the daughter of��Manilal, Gandhi���s second son. She grew up Durban and was involved in the anti-Apartheid struggle (she spent nine years under house arrest) and became an MP of the ruling African National Congress, in 1994. She retired from politics in��2004.

An opinion piece she wrote��at the end of last year��in��The Mercury, a popular daily newspaper in Durban,��strains to find a way to continue the myth��and iconography��of��her grandfather.��Before dealing with the substantive issues in her article,��let���s��dismiss the simplistic notion that opposition to Gandhi is due to a book that��Goolam��Vahed and��I co-authored in 2015.��To believe that is to treat the symptoms rather than the cause.��A chronological look at protests exposes the��hollowness��of this claim.��In 2003, for example,��debates around Gandhi���s problematic iconography were expressed at Gandhi Square in Johannesburg through contestation of��his��statue erected there.��Reginald Legoabe��opposed the statue on grounds��that�����Gandhi never thought much of African people�����(City Press,��9��November 2003). In 2007, copies of a booklet by Velu Annamalai,��Gandhi: A Stooge of the White South African Government��were��distributed��in South Africa.��In April 2015, before our��book��was released, Gandhi���s statue was vandalized in Johannesburg by protestors��demonstrating with placards reading�����Racist Gandhi must fall�����and the hashtag #GandhiMustFall was circulated on social media.

To blame��the��book for African opposition to Gandhi in Ghana, Malawi, and elsewhere is disingenuous, for it��ignores the fact that a new generation of African activists��seek to��challenge both romantic narratives of de-colonial struggles and��the��present-day��neocolonial activities of countries like India and China.��Officials in New Delhi announced they would cancel hundreds of university scholarships to Ghanaians, for example, as collective punishment to the next generation: what a message that sent,��both to intimidate the youth (unsuccessfully) and to get their parents��� generation to back-track (successfully) on the Gandhi statue���s removal.

In her article, Ela Gandhi does exactly what she accuses us of in our book, by selectively quoting from one Anil Nauriya as an example of Gandhi���s pro-African stance. Arguing that Gandhi said some nice things about Africans cannot exculpate him from the voluminous evidence of anti-African racism and his attempt to cozy up to white racist, colonial rule while in South Africa.

Gandhi���s time in prison provides a cameo of his approach to Afro-Indian relations. It is here in 1909 that his activism, as Isabel Hofmeyr shows, crystalizes in wanting Indians inside and outside prison�����not to be classed as native��� I have made up my mind to fight against the rule by which Indians are made to live with Kaffirs and others.�����Gandhi petitioned the authorities to be given the same privileges as White prisoners. He saw�����a boundary that could not be crossed and that is a line marked by the native.�����This is��just��a��snippet��of a host of racist statements that Gandhi made post-1906.

When Africans, Coloureds and��Whites (specifically��parliamentarian��W.P.��Schreiner) joined in an historic delegation to��London��in 1909 to try��to��ensure that the forthcoming Union of South Africa would not disenfranchise ���non-Whites,��� Gandhi��also travelled there,��but refused to join this historic alliance��which��saw major shifts,��especially from the leader of the��Coloured African Peoples Organization (APO)��Dr Abdurrahman,��who��joined��African allies as part of a united front.

Why did Gandhi insist on standing alone?��In South Africa he��had marked out a path that argued that Indians deserved the franchise because of their status as British subjects. Now that Africans and��Coloureds were doing the same he could not contemplate joining them. This was a mix of strategy (Indians had India),��as much as a racist��antipathy towards Africans and��Coloureds, and��witnessed by��his insistence that Indians not be lumped with them.��In the face of this��Anil Nauriya writes��that�����Gandhi sought to join forces in 1909 with WP Schreiner in lobbying efforts in England to garner rights for Indian and Africans in South Africa.�����It is this kind of attempt��to sanitize Gandhi that would make��Mohandas��wince.

Gandhi���s��passive resistance comes imbued with a sense of Indian superiority and African inferiority. Witness one of Gandhi���s lieutenants,��A.M. Cachalia, in 1908:�����Passive resistance is a matter of heart, of conscience, of trained understanding. The natives of South Africa need many generations of culture and development before they can hope to be passive resisters in the true sense of the term.”

Manilal Gandhi��(Ela��Gandhi���s father)��stated in 1951 that Africans��were ���impetuous��� and lacked the necessary discipline to embark on a defiance campaign.��Following the Defiance Campaign of 1952, Durban-based��journalist Jordan Ngubane warned that the�����treatment meted out to African leaders and African contributions by important sections of the��Indian��press��(in India)��at times does little to cement Afro-Indian relations��� The impression is being sedulously created that the African leaders of the struggle are juniors to their Indian counterparts.���

These issues have been hashed many times and��I��could��have overlooked��Ela��Gandhi���s��cringing defense were��it��not for two things. The first is the��scorn��for the position taken by the Dalit leader Ambedkar,��who she cannot even name��yet��accuses of being a pawn of the British. It is now the stuff of history that Ambedkar sought to expose how the Hindu caste system was fundamental��to the oppression of the Dalits and��how he��sought ways to ensure that their status was not confined to the very category that humiliated and degraded them.��Gandhi reacted in 1932��to��force Ambedkar to relent in��what��has��come to be known as��the Poona Act.

Let��us forget Gandhi���s bullying and acknowledge that Ambedkar was central to��situate��caste oppression and representation��at the��center of the political demands of Dalits. As��Anupama��Rao puts it:�����the events of 1932 marked Ambedkar���s entrance on the national stage as a powerful critic of Congress nationalism,��an insurgent thinker, and a reluctant founding father whose ideas of radical equality were well beyond the time.�����Rao goes on to show how�����Ambedkar used the demand for separate representation as a way to translate the negative identity of Dalits into a collective political interest.�����But for Ela��Gandhi,��like her grandfather, Dalits cannot think for themselves,��being no more than��dupes of the British.

The second��incident��is Ela��Gandhi���s��response to the visit of the butcher of Gujarat,��Narendra Modi.��Keeping in mind that��Ela��Gandhi��wants us to develop an ethical politics in South Africa,��Modi���s visit��presented an opportunity��to do��just��that. But instead��of taking a stand,��since Modi stands for everything her grandfather did not (from industrialization to nuclear arms��to designer outfits),��she��instead��paraded him around the Phoenix Settlement.��Professor��Shiv��Visvanathan wrote��in response to Modi���s visit:

I was appalled and agitated when I saw Ela Gandhi welcome him to Phoenix Farm.���I was reminded of a comment by a historian who said, “today every party rewrites history”��� The Right, especially the RSS, was opposed to Gandhi and had little to do with the national movement.���There was an even greater irony in Modi���s trip as the RSS, of which he was a��pracharak��(full-time worker), was opposed to Gandhi.���I do not know what Modi thought while he sat in the wood planked train. But, I was wondering whether at that moment the RSS and its ilk thought of apologising to Gandhi and the nation for the assassination.���I was for one moment expecting an apology for the 2002 riots. An apology would have made history doubly alchemic, if he had used his sense of the truth commission to offer a new sense of reconciliation in Gujarat.��It would have made the train ride another turning point in history. Yet, Modi is not moved enough.

In the face of this for Ela Gandhi��to call on us to pursue some kind of ethical politics is tantamount to the Gupta brothers��calling on us to take a stand against��corruption.

Israel and Palestine: The South African alternative

Image: Alisdare Hickson (via Flickr CC).

��� Edward Said, 1999There can be no reconciliation unless both peoples, two communities of suffering, resolve that their existence is a secular fact, and that it has to be dealt with as such��� Once we grant that Palestinians and Israelis are there to stay, then the decent conclusion has to be the need for peaceful coexistence and genuine reconciliation.

The situation in Palestine is dreadful. The United Nations warns that the Gaza Strip will be incapable of supporting human life by 2020. Palestinians in the occupied territory have been demonstrating every week since March 2018 against the loss of basic service provision due to Israel���s land, air and sea blockade which now enters its 12th year. Over the course of these demonstrations, 190 ordinary Palestinians were killed and 28,000 were injured. The United Nations has said that Israel may have been guilty of committing war crimes by deliberately targeting unarmed civilians with live ammunition.

In 2003, Tony Judt infamously declared that Israel was ���an anachronism.��� Consider, that the western democratic world almost unanimously decries any state which is founded upon an ethno-nationalist ideology, accompanied with some marriage of religion and state, as well as the inevitable relegation of groups of people outside this ideal-type to second-class standing, systematically or otherwise. Consider again, that this state, is effectively Israel.

Let���s be clear, and unapologetically so: Israel, in its current, Zionist form (which is a self-described Jewish and democratic state that simultaneously denies both integration of and self-determination to Palestine), must be opposed. That claim, however, is quite different from claiming that Jews have no right to exist. The Israeli government���s very project has been leading us to needlessly conflate the two, and falsely believe that protecting against the latter claim depends on sustaining Israel���s current form.

It���s obvious to say that opposing Afrikaner nationalism is not tantamount to opposing Afrikaner people. Equally, to oppose Zulu nationalism is not to oppose Zulu people. This is as much the case in opposing Zionism, and its adoption as the chief ethos underpinning Israel. As Israel���s raison d�����tre, Zionism maintains that Jews possess a pre-ordained, biblical right to the Israel and Palestine territories, an entitlement sharpened by the desire for a Jewish sanctuary after the horrific genocide that was the Shoah. Beyond this, it seeks a fundamentally Jewish character in the governance of the Israeli state, or as Virginia Tiley put it, for its public institutions to enshrine ���permanent Jewish ethno-nationalist ascendancy.���

Here���s the thing. While Israel���s original inception understandably depended on a legitimate, initial victimization, it now sustains itself through a constant re-victimization in spite of things being markedly different from the time it was created. In doing so, it purports to face perpetual existential threat from Palestinian belligerents by first creating the very conditions for Palestinians to seek belligerence, and predictably crying victim when Palestinians are unsurprisingly, belligerent.

Leaving that aside, at this point of a struggle that has become so depressingly protracted, debates about the manner by which Israel came to fruition are a non-starter. The harder but more pressing question is how to bring the dispute to a viable resolution and to the satisfaction of both parties���the only way to guarantee long-lasting peace. The international consensus prefers a two-state solution. This, would presumably be partitioned along the pre-1967 borders with the right of return for Palestinian refugees, have East Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital as well as the guaranteed demilitarization of Palestine and subsequent withdrawal of the Israel Defense Forces.

But, in a conflict so outstretched and with painfully stalled and sporadic negotiations, conditions can only quickly or gradually deteriorate. The resounding failure of the international community to hold Israel to any serious grain of accountability for its systematic aggression has seen it develop the kind of unabashed hawkishness that may very well be beyond restraint.

All other things remaining the same, the persistence of the blockade in the Gaza Strip could soon lead to a scale of deprivation and squalor that would forcibly expel Palestinians residing there. If the Israeli government���s aggression remains unchecked, its violent persecution could escalate to fit the terms used to describe the treatment of the Rohingya in Myanmar, the Yazidis in Iraq and Syria, or the Nuer in South Sudan.

Illegal settlements encroaching into Palestinian land are unlikely to subside any time soon either. As things stand, the West Bank is a jumbled patchwork of Israeli settlements weaving through Palestinian towns. There are more than 600,000 settlers estimated to be in the West Bank who have institutionalized their stay by building thriving businesses, schools, hospitals and universities���it���s hard to imagine that this firmly entrenched community can simply be uprooted without opposition.

Even in the best case scenario of a successfully negotiated two-state solution, the outcome is unlikely to be beneficial for Palestine. Israel has so thoroughly destroyed their infrastructure and state apparatus that an emergent Palestinian state would steadily assume a neo-colonialist, bantustan-like dependence on Israel. Either way, what���s almost certain in every case is continuing hostility towards the Palestinian people, precisely because the essence of Israel���s current existence and the coherence of its project depends on the presence of an overblown threat to it, one first imagined, then reified.

The Israeli government has invested so much in fashioning the spectre of an Islamist-gevaar that it won���t dissipate once Palestine is fully self-determining within its own borders. If anything, it might birth a more bellicose Israel. Palestine, in becoming an ordinary, fully-fledged state, would in Israel���s mind deserve a fully-fledged provocation if deemed necessary. It is not wholly inconceivable that such a provocation may teeter towards a war-like militancy, if not fully spiral into war itself.

As an alternative, one post-Zionist future for Israel and Palestine envisions a secular, constitutional democracy built on a bill of rights guaranteeing universal adult suffrage, non-sectarianism, and the achievement of equality and dignity for all. It is the only option that retains the possibility for some kind of restorative justice scheme for atrocities suffered by both sides. Whatever the balance of culpability turns out to be (which is an unhelpful preoccupation to start with), the dispensing of justice should have reconciliation as its ultimate goal.

Once again, Jews should obviously remain in Israel. That isn���t contingent on Israel remaining a Jewish state. When concerns arise about the threatened security of the Jewish people in a single state (having their origins in Islamophobic tropes about what would happen if Jews became a minority), they are easily rebutted by reference to the guaranteed protections a bill of rights would provide. Whatever concerns about the lingering second-class citizen status Palestinians would have in a single state, they are abated by the prospect of redress programs to account for generational and ongoing disadvantage���and perhaps even a return to Israel���s more radical economic roots.

This isn���t to naively view the one-state state solution as a panacea. Important questions about its feasibility, as well as around the actual wishes of the Palestinian people naturally spring up. Admittedly, not only is the political will almost completely lacking under the leadership of�� returning Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, but it would expectedly be absent in Palestine. The Palestinian people have become so desperate for a break from the brutality of the Israeli government that the short to medium term emancipatory agenda has to be focused on campaigning for a relaxed blockade, the release of arbitrarily detained prisoners, and the provision of essential services.

Inside Palestine, political leaders lack a united front. Hamas and Fatah are fractious as ever, with many disaffected, younger Palestinians feeling that both sides are more concerned about acquiring political power and weakening their rivals than they are about Israeli Occupation. Indeed, the strength of any resistance looks elusive when the political structures that have until now dominated such efforts behave in ways that divide, all the while America muscularly rallies behind the Israeli government ahead of Donald Trump���s so called ���deal of the century.���

Due to the hostile political landscape, inspired leadership elsewhere is scarce. Many influential politicians, journalists and commentators find themselves in hamstrung positions where even the slightest criticism of Israel and its policies evokes career-destroying backlash. Look at what happened to Marc Lamont Hill, formerly of CNN. Look once more at Ilhan Omar, and the bitter smears targeting her since she called out the undue influence that pro-Israel lobby groups have on American foreign policy. In France, Emmanuel Macron is pushing forward legislation that would classify anti-Zionism as ���one of the modern forms of anti-Semitism.���

But leadership need not come solely from America. Unlike most parties who will probably be pinned to frustrating political and moral compromises, South Africa is uniquely placed to exert unapologetic moral leadership. This role has been earned seeing as not only did we successfully negotiate a largely peaceful settlement following Apartheid to the astonishment of the rest of the world, but two decades on, can take cognizance of what worked, what didn���t and what could���ve been done differently. We are the modestly successful test case for a unitary constitutional democracy after a long, bitter conflict.

For now, South Africa���s role has been fairly tame. By belonging to a host of softly outspoken countries, our foreign policy movements have typically been in calling for a two-state solution, the withdrawal of IDF forces from Gaza, and kicking off a set-piece of diplomatic censures such as recalling ambassadors when violence flares up. Honestly speaking, our lack of political and economic capital renders most of these actions toothless. What still remains untapped, is our potential for moral leadership.

During our own struggle against a racist, Apartheid state, South Africa was once at a crossroads where after years of protest to no avail, the future of the country was uncertain. What happened in 1955, became a seminal moment in South Africa���s Apartheid history. The adoption of the Freedom Charter was led by what was then known as the Congress Alliance, a multi-racial political alliance co-ordinated by the African National Congress (ANC) and bringing together radical movements consisting of Blacks, Whites, Indians and Coloureds, a large segment of which were Jewish and Muslim���all united in their opposition to the ethno-nationalism embodied by Apartheid.

The Freedom Charter���s adoption is rightly considered a centerpiece of the Apartheid struggle. It would capture the popular imagination of South Africans by its audacious presentation of an alternative social order, one picturing a non-racial South Africa where ���no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of the people.��� The demands made in the Freedom Charter were a forerunner to our present Constitution which is widely considered the most progressive in the world, and was brought about after a painstaking, multilateral negotiation effort in the 1990s.

So then, what can South Africa do by way of concrete action? It can start by boldly favoring the one-state solution as a foreign policy position. Crucially, this can���t happen simply by paying lip service to the idea, but must include real efforts aimed at supporting, coordinating and mobilizing activists from the movement and giving them the platforms plus resources to rally the cause���much like was done during Apartheid for our own freedom fighters in exile across the world.

Building this resistance capacity is a commitment already undertaken by the ruling ANC. At its 52nd National Congress in 2007, it committed to ���lead efforts to strengthen and coordinate a broad-based Palestinian solidarity movement��� and to ���become a leading part of the world-wide movement, which includes South African civil society, supporting the struggle and campaigns led by Palestinians.���

But, taking stock of what���s developed in the situation 10 years later, at its 54th Congress the ANC ���calls on the Palestinians to review the viability of the two state solution in the light of the current development.��� It���s welcomed that the ANC is moving to downgrade the South African embassy in Israel, and it must now take the one-state alternative seriously.

Even if it doesn���t create the appetite, reviving the one-state solution would serve well to inject new energy to a conflict that���s been dismayingly stagnant. It might even scare Israel to double down on the two-state solution.

Recall, that in 2007, then Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert had this to say after the Annapolis Conference: ���If the day comes when the two-state solution collapses, and we face a South African-style struggle for equal voting rights (also for Palestinians in the territories), then, as soon as that happens, the State of Israel is finished.��� Olmert went further, saying that, ���The Jewish organizations, which were our power base in America, will be the first to come out against us, because they will say they cannot support a state that does not support democracy and equal voting rights for all its residents.���

By the modern Israeli state���s own admission, the only way to undercut its near-irrefutable, seeming moral high ground (without being called an anti-Semite), is not in striving toward a state of affairs that would retain its rhetorical feasibility (the two-state solution), but for one that would render it rhetorically obsolete (a single, secular and democratic state). The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement would have more force if Israel was not just a quasi-Apartheid state, but an Apartheid state proper.

That said, the South African government (regardless of the strength of the Apartheid analogy) should also enact boycotts, divestments and sanctions against Israel. Fixating on what the situation in Israel and Palestine should appropriately be called, although once being a relevant consideration raised in good faith, has slowly become beside the point. Now, it���s being weaponized as the favorite red-herring of the Israeli government���s apologists who swiftly come to the government���s defense by claiming that because Israeli citizens of Arab-Palestinian descent have access to the same formal rights as their Jewish counterparts, it therefore means Israel technically can���t be an Apartheid state.

Whatever you call it, the Israeli government is carrying out gross human rights and international law violations in Occupied Palestine. It does so in ways that all at once resemble an Apartheid state, a settler-colonial one and just about any regime which systematically oppresses an ethnic group. What���s more, with them now unashamedly passing laws like the Nation State Law, which symbolically yet unequivocally declares that self-determination in Israel is unique to Jews, the Israeli government signals a slow march rightward obsessed with preserving the purity of a ���Jewish Volk������one that if followed through to its logical conclusion, will have unspeakable consequences for anyone outside of that identity.

To directly quote Netanyahu on this: ���Israel is the nation-state of the Jewish people and them alone.���

Truth be told, the persistence of the more than 50-year occupation demonstrates that as far as Israel is concerned, it���s sustainable. All that���s changed is its trajectory, one inevitably heading towards a single state albeit one extremely Jewish. So long as Israel remains a Zionist state, its relationship to the Palestinian people will necessarily be contemptuous. For this reason, the case for a single, constitutional and democratic state is a persuasive moral and ideological counterweight that begins by questioning the nation-state form of social organization, the soul of Israel���s project.

The unavoidable question is whether or not it is practically feasible. The real question, is why those two issues should be taken up separately. South Africa can legitimize calls for the one-state solution by insisting that what made our struggle mostly successful, flawed as our society still is now, was by acknowledging the hopelessness of the situation and looking beyond the limitations of what was viewed possible.

To be sure, South African moral leadership can only go so far, that���s undeniable. Although, despite the appearance of a pro-Israeli onslaught that dominates the height of media coverage, moods are shifting and conditions more amenable. New studies show that increasingly, ordinary Americans are open to a one-state solution of equal rights and citizenship. The One Democratic State Campaign initiated by mostly Palestinian and Israeli activists is reviving calls for a single state, and before its official launch in May, is gaining some traction (see here for its visionary proposal, and here for criticism of some of its aspects).

Even in Israel, beneath the triumphant posture of Netanyahu���s Likud party, the sides aren���t so clearly marked. Writing for The Atlantic, Israeli author Micah Goodman remarks that most ordinary Israelis have ���lost their sense of conviction��� and that they are ���confused.��� The problem, as Goodman notes, is that the Israeli Right and Left are trading alternate but extreme visions of dystopia and chaos: for the the Right, it���s the catastrophe of withdrawal, for the Left, the catastrophe of remaining. For ordinary Israelis, this misleadership means being tied to a schizophrenic horseshoe of manufactured anxiety and fear.

What accelerated change in Apartheid South Africa during the 1980s amidst a climate of mass unrest (as we are witnessing now in the Gaza Strip and West Bank) as well as increased state-securitization from then hardliner president P.W Botha (who bought weapons from Israel), was the re-articulation of a social order where any and all could imagine their place. The advent of the United Democratic Front in the 1980s, a multiracial coalition of trade unions, religious groups and students, massively revived the Freedom Charter���s vision of a united South Africa, one that the Apartheid government greatly feared. Behind the slogan ���UDF Unites, Apartheid Divides��� clarity dawned where confusion once fogged.

This renewed internal struggle, revitalized the international struggle which eventually culminated in widespread boycotts, divestment and sanctions���in the view of many, this was the tipping point that toppled Apartheid.

When Tony Judt correctly denounced Israel as an anachronism, he wrongly concluded that the one-state solution would come only at the behest of American leadership. Almost 16 years on, it is clear that this leadership won���t come from the US, no less when controlled by Trump (who is just more forthright about Washington���s standard pro-Israel position shared by mainstream Democrats and Republicans alike). Granted, US support is ultimately a necessary condition for an eventual solution, but South Africa can help generate sufficient conditions for a lasting one.

From the Jordan river to the Mediterranean sea, Israel and Palestine belongs to all who live in it, Jew, Muslim or Christian, and no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of people.

April 12, 2019

Rwanda has an opposition problem

Paul Kagame speaking at the UN General Assembly in 2015. Image credit Cia Pak via Flickr (CC).

At the start of March 2019, Anselme Mutuyimana, the spokesperson of the United Democratic Forces of Rwanda (FDU-Inkingi),��an opposition coalition,��was found dead in Gishwati National Forest. At 30 years old, his death is tragic, yet unsurprising.

Mutuyimana���s death comes just three months after the acquittal of Diane Rwigara���the 2017 would-be presidential candidate and outspoken critic of Rwanda���s President Paul Kagame���and her mother, Adeline, of what the three-judge Kigali High Court bench called the ���baseless��� charges of inciting insurrection and forging endorsement signatures. Though their family���s substantial assets were auctioned off before they were granted bail in October, the drop of the Prosecutor General���s appeal in January seemed to signal to the world that Rwanda was finally ready to accept not only opposition but true gender parity in politics.

Though in January, it appeared as if she would be the last, Rwigara was certainly not the first opposition figure to face persecution during President Kagame���s tenure. Seven years earlier, another female presidential candidate��and the leader of��FDU-Inkingi, Victoire Ingabire, was sentenced to a 15-year prison term on similar charges.��Ingabire��had��formed��FDU-Inkingi in��exile in 2006. She served over eight years of that sentence before being released, along with 2,100 other prisoners, in September,��2018.��At the time of��her release,��Ingabire��said it��marked ���the beginning of the opening of political space in Rwanda.��� Given the fate of her spokesperson, perhaps she spoke too soon. Mutuyimana���s death marks the continuation of an almost decade-long pattern of mysterious disappearances and deaths, as well as arrests, torture, and imprisonment of numerous opposition figures and journalists.

Just a month before the 2010 Rwandan presidential elections, Andre Rwisereka, leader of Rwanda���s Democratic Green Party and presidential candidate, was discovered near Butare with��his head almost completely severed. That same year former Lieutenant general Kayumba Nyamwasa was shot in the stomach in Johannesburg, South Africa; he survived. The journalist investigating the attempted assassination, however, was killed in Kigali several days later. New Year���s Day, 2014: Patrick Karegeya, former head of intelligence in Rwanda, was found strangled in his hotel room in Johannesburg; he had been living in exile since 2007, after being jailed twice in his home country. May 2017, FDU member Jean Damascene Habarugira, was summoned to a meeting with security officials. Several days later, his family was called to retrieve his body from a hospital. Just a month before the release of Victoire Ingabire,��in August 2018, FDU-Inkingi Vice President Boniface Twagirimana, was arrested along with eight other party members on charges of ���forming an armed group with the intent to overthrow the government of Rwanda.��� Less than a month later, the Rwandan Correctional Service reported Twagirimana missing from a headcount following an unannounced transfer from one prison in Kigali to another in the southern district of Nyanza. Twagirimana is believed dead.

And now Anselme Mutuyimana.

The question of who is responsible for the precarious existence of Rwandan opposition party leaders and journalists is one that, frankly, will not have an answer any time soon. To speculate on the identity of the individual or group that shared decision-making authority regarding any of these cases is to flirt with participation in what the late Okwui Enwezor called ���the disaster mongering of the Western media… that make[s] Africa seem less than a nurturing place��� and which all-too-frequently creates only tragic narratives of an��Africa populated exclusively by heroes and villains.

Conversely, to ignore the concreteness of these abuses���either by foregoing reporting on the subject within its full context or by refusing to ask hard questions of the Kagame administration���would be to achieve a slightly different end to the same imperialistic role. The Western journalist, observer, analyst, tiptoes the line on which one side lies “disaster mongering” and on the other lies the rubber stamp of approval routinely provided by the likes of Tony Blair and Bill Gates. Rock. And hard place.

Keeping this mind, it is difficult to imagine a stronger correlation than that which exists between the deaths, disappearances, and imprisonment of so many opposition party members and the re-elections of an executive who has not only been the de facto leader since 1994, but who also won the opportunity to stay in power until 2034 through a 2015 constitutional referendum that 98 percent of voters approved following a spontaneous petition signed by four million Rwandans. It is more difficult still to imagine a more fitting connection than that which forms between Kagame���s ominous words of warning immediately following the death of Karegeya and the recent revelation by a Johannesburg magistrate that all four suspects in his killing were Rwandan nationals. Given these details, it is difficult to resist the potentially maleficent, albeit journalistic,��urge to connect certain dots despite their being viewed from a distance both geographic and cultural. When a country���s own journalists are prevented from doing their work due to arrest or worse, what then is the role, if any, of the Western/foreign journalist? Who, without the bias described by Enwezor, is left to ask hard questions, and what can be achieved by hard questions when they are posed to a politician as adept as Kagame?