Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 26

September 11, 2016

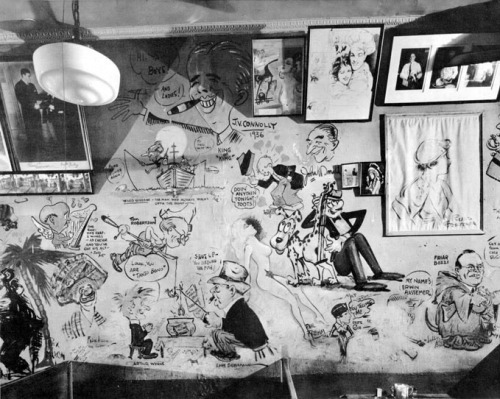

Faces on the wall

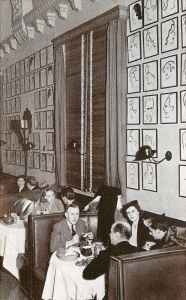

People love seeing celebrities in a restaurant. Trouble is, celebrities can’t sit around in restaurants all the time. Solution: put a photograph or a cartoon of them on the wall, suggesting that they are regulars, liable to walk in at any moment.

In the United States the custom developed first in urban theater districts, in places visited frequently by publicity-seeking performers after the show.

Sardi’s in New York City [shown above] is still famous for its walls of caricatures of stars of the moment and of the past. Sardi’s tradition began in 1927, reportedly inspired by the custom in Parisian cafes. But Vincent Sardi could have found precedents in the United States too.

An early instance was Chicago’s Chapin & Gore’s of the 1870s. Located in the vicinity of McVicker’s Theatre, it was a place where “exceedingly well dressed, fast-looking men” hung out with women suspected of questionable character (a suspicion that applied to any woman without a male escort). Not only did actors make it onto Chapin & Gore’s wall but also the city’s mayor, newspaper publishers, and leading industrialists. Another room displayed what temperance advocates described as “indecent and obscene” caricatures of European notables, which a court ordered removed in 1878.

Another 19th-century precedent, dating back to at least the early 1890s, was Otto Moser’s café in Cleveland, still in business today but not at its original location. Once within walking distance of seven theaters, its walls were lined with playbills and autographed photos of performers.

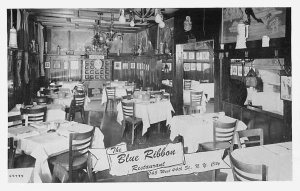

In New York City, as early as 1910 Joel’s Bohemian Refreshery adorned its walls with cartoons and photographs of entertainers, some drawn by Carlo de Fornaro. The café was not only popular with Broadway performers but also with Mexican rebels and others opposed to the presidency of Porfirio Diaz, aided by de Fornaro’s pen and brush. The Blue Ribbon, opened near Times Square in 1914 and closed in 1975, was also decorated with caricatures and photographs.

In New York City, as early as 1910 Joel’s Bohemian Refreshery adorned its walls with cartoons and photographs of entertainers, some drawn by Carlo de Fornaro. The café was not only popular with Broadway performers but also with Mexican rebels and others opposed to the presidency of Porfirio Diaz, aided by de Fornaro’s pen and brush. The Blue Ribbon, opened near Times Square in 1914 and closed in 1975, was also decorated with caricatures and photographs.

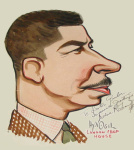

Challenging Sardi’s for nationally-known wall fame was Hollywood’s Brown Derby restaurant, which opened in 1929 and closed in 1985. Lore has it that caricatures of movie star patrons from the nearby studios began to go on the walls after a Polish artist agreed to exchange his artwork for meals. He achieved fame as “Vitch,” later mailing his sketches from London where he had a career as a pantomimist. Like Sardi’s, the Brown Derby employed many a sketch artist over the decades, however few restaurant artists stayed on the job as long as the Detroit London Chop House’s Hy Vogel [“Prince” Mike Romanoff shown below].

Challenging Sardi’s for nationally-known wall fame was Hollywood’s Brown Derby restaurant, which opened in 1929 and closed in 1985. Lore has it that caricatures of movie star patrons from the nearby studios began to go on the walls after a Polish artist agreed to exchange his artwork for meals. He achieved fame as “Vitch,” later mailing his sketches from London where he had a career as a pantomimist. Like Sardi’s, the Brown Derby employed many a sketch artist over the decades, however few restaurant artists stayed on the job as long as the Detroit London Chop House’s Hy Vogel [“Prince” Mike Romanoff shown below].

Today, a repro Brown Derby lives on, so to speak, on the grounds of Disney Studios, complete with caricatures (of course). Which reminds me of the inquiring reporter exploring a number of Dallas restaurants adorned with celebrity photos. He asked the manager of a national chain restaurant in 1982 whether it was really true that Cary Grant had eaten there, in Dallas. Not exactly, admitted the restaurant’s publicity director, but the actor had been to one of the chain’s other units. Somewhere.

It’s rather surprising that Cary Grant’s picture was even on a restaurant wall in 1982 since he made his last movie in 1966. Given that fame doesn’t last long, those who manage picture walls tend to rearrange them from time to time. What to do with outdated celebrities, stars no one has heard of? In the 1970s Sardi’s moved old-timers to “memory lane” on the second floor, while the owner of Miller’s Coffee Shop in Little Rock AR admitted at the restaurant’s closing in 1970 that a few years earlier many of its caricatures had been given away or simply papered over.

An equally sad fate has befallen regular patrons of Palm steak houses. The tradition of drawing and painting caricatures of famous and faithful customers directly on the walls began at the original Palm on 45th street in New York City [shown above] during the Depression. Later, it continued at locations around the country, but in recent years many of the images have been destroyed due to remodeling and closures.

When you think about it, restaurants’ fortunes are as shaky as those of celebrities.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

August 28, 2016

Dining for a cause

During the Civil War, fairs were held in over twenty Northern cities to raise funds for the United States Sanitary Commission, a private organization that supplemented the Union Army Medical Corps’ efforts to care for wounded soldiers.

New York state held five fairs, in Albany, Poughkeepsie, Rochester, Brooklyn, and New York City. The Brooklyn and New York City “Sanitary Fairs” were massive endeavors resulting in donations of enormous amounts — $300,000 and $1,000,000, respectively — to the Sanitary Commission.

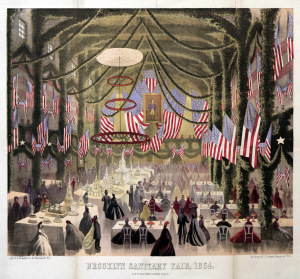

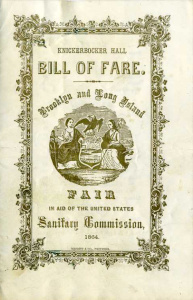

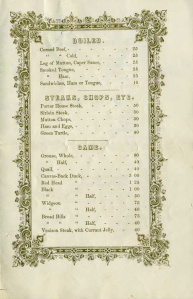

The fairs featured music, displays of art and curiosities, tableaux vivants, and other entertainments. Restaurants were an especially popular attraction. This week, a friend whose ancestors were involved with the Brooklyn fair gave me a wonderful printed-in-gold bill of fare from that fair’s Knickerbocker Hall Restaurant.

The fairs featured music, displays of art and curiosities, tableaux vivants, and other entertainments. Restaurants were an especially popular attraction. This week, a friend whose ancestors were involved with the Brooklyn fair gave me a wonderful printed-in-gold bill of fare from that fair’s Knickerbocker Hall Restaurant.

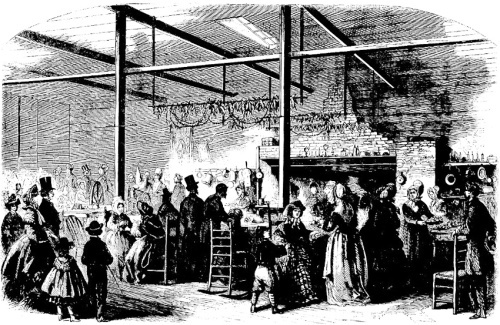

There were two main eating places at the two-week-long Brooklyn & Long Island fair, the larger one located in the temporary, specially built two-story Knickerbocker Hall located next to the Brooklyn Academy of Music [shown above]. The other restaurant, The New England Kitchen, occupied another temporary building across the street [shown below].

The Refreshment Committee in charge of the two restaurants was quite successful in getting donations of food supplies, including almost $20,000 worth of wine. But public opinion nixed serving wine, along with holding raffles, as improper for a fair in the “City of Churches.” So the wine was given instead to the New York Metropolitan Sanitary Fair which was held about a month after Brooklyn’s, in April of 1864.

The Refreshment Committee in charge of the two restaurants was quite successful in getting donations of food supplies, including almost $20,000 worth of wine. But public opinion nixed serving wine, along with holding raffles, as improper for a fair in the “City of Churches.” So the wine was given instead to the New York Metropolitan Sanitary Fair which was held about a month after Brooklyn’s, in April of 1864.

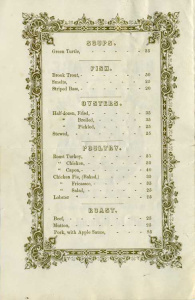

Despite the absence of wine, the Brooklyn fair outdid the Metropolitan NYC fair in how much money its  eating places cleared. Compared to the Metropolitan NYC fair, the Brooklyn menu was simplified, with no relishes or fruit, and few soups, cold dishes, or pastries. Brooklyn netted $24,000 for the cause, while the Metropolitan fair cleared only a little over $7,000 because, unlike Brooklyn, they received little donated food (uh, what happened to the wine?). Brooklyn’s New England Kitchen added perhaps as much as another $10,000 for the Sanitary Commission.

eating places cleared. Compared to the Metropolitan NYC fair, the Brooklyn menu was simplified, with no relishes or fruit, and few soups, cold dishes, or pastries. Brooklyn netted $24,000 for the cause, while the Metropolitan fair cleared only a little over $7,000 because, unlike Brooklyn, they received little donated food (uh, what happened to the wine?). Brooklyn’s New England Kitchen added perhaps as much as another $10,000 for the Sanitary Commission.

Brooklyn’s Knickerbocker Hall Restaurant, which could seat 500 at a time and took in about $2,000 a day, was under the direction of the men’s refreshment committee, while the New England Kitchen was run by a committee of women. The Kitchen was tremendously popular, serving 800 to 1,000 persons daily. But it occupied too small a space and, as the commemorative volume issued by the fair noted, would have made a greater profit had it been able to accommodate larger crowds.

Brooklyn’s Knickerbocker Hall Restaurant, which could seat 500 at a time and took in about $2,000 a day, was under the direction of the men’s refreshment committee, while the New England Kitchen was run by a committee of women. The Kitchen was tremendously popular, serving 800 to 1,000 persons daily. But it occupied too small a space and, as the commemorative volume issued by the fair noted, would have made a greater profit had it been able to accommodate larger crowds.

Unlike the Knickerbocker, the Kitchen’s bill of fare did not replicate that of a fine restaurant. Nor did the Kitchen follow the prevailing custom of hiring Afro-American men as waiters. The Kitchen used (white) women volunteers who served meals dressed in mid-18th-century costumes that visitors found ugly yet fascinating. For a set price of 50 cents, considerably less than a typical dinner composed from the Knickerbocker Hall’s a la carte menu, they served a down-home meal of such things as pork & beans, brown bread, applesauce, baked potatoes in their jackets, hasty pudding, and cider. Food was eaten from old china with a two-tined fork. The Kitchen also hosted events such as spinning wheel demos, apple paring bees, and an actual wedding.

Though it’s hard to draw a straight line from The New England Kitchen to women’s tea rooms of the early 20th century, it is notable how many tea rooms adopted a similar theme, right down to the old-style cooking fireplace and spinning wheel. It was also significant that so many women assumed executive and managerial positions on fair committees, especially in the New England Kitchen, and it’s probable that many of them remained active in public life after it ended.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

August 15, 2016

“Come as you are”

Before restaurants adopted the expression, it was used by churches, with a double meaning that referred both to dress and to the shame of past deeds.

However, in restaurants it simply meant that patrons could wear their everyday casual clothes.

In the hospitality field, the slogan took hold first in the West. In the teens and 1920s, it was commonly used by hotels and resorts. It may seem odd that a resort where people swim, golf, and play tennis would require women to wear dresses and men to wear jackets to dinner, but that was not uncommon in the 1920s, especially in the East. In fact, the custom can still be found today, but it stands as a quaint re-enactment of past times as much as anything.

The western attitude toward casual dress in hotels, resorts, and restaurants spread slowly and was not without some resistance. Oddly, it met the greatest resistance from a business operating in the West: the Fred Harvey company that ran eating houses for the Santa Fe railroad.

The Harvey company required men to wear jackets in its dining rooms – even before electric fans and regardless of hot weather. If a man refused to wear a jacket, he would be served only at an adjoining lunch counter. In the early 1920s the Harvey company fought an Oklahoma Corporation Commission decision that threw out Harvey’s jacket rule. But Oklahoma’s supreme court ruled in favor of Harvey, declaring that the company had the right to require jackets. “Unlike the lower animals, we all demand the maintenance of some style and fashion in the dining-room,” said the decision.

Full-scale formal dress – white tie and tails for men and women wearing long evening gowns – was never common in this country. Nonetheless etiquette advisors who wrote for women’s magazines liked to suggest the opposite, flattering (and confusing) their readers with rules followed only by the upper, upper reaches of high society. However, even if formal wear was rarely necessary, there was an expectation that diners in a nice restaurant or hotel dining room would at least wear what we now refer to as business attire. The St. Regis Hotel in New York City advertised widely in 1908 that it was a comfortable, homey hotel opposed to snobbish dress rules, yet making it clear that “The wearing of a business suit bars no one from admission or service.”

As widely as she was published and read, etiquette maven Emily Post never seemed to be in tune with most Americans. During the depths of the Depression she continued to insist that women should wear suits, hats, and gloves to a restaurant lunch and dinner dresses in the evening. Even at a summer resort, she declared, women should wear cover-up shoes when dining out. “Bare-toed sandals with evening dresses are too revolting to mention,” she wrote.

Following World War II as young families were established and the suburbs spread, things began to change radically. The restaurant industry realized that finding a babysitter or dressing up the whole family was a barrier to restaurant going for many. Instead families were turning to informal roadside places. “Drive-ins, with their motto of ‘Come as You Are, Eat in Your Car,’ have a siren call for parents with insoluble sitter problems,” observed the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1960.

Chains also got the message. A 1963 Bonanza advertisement proclaimed low-priced steak dinners plus “No tipping – Children ½ price – Come as you are – Western atmosphere.”

Meanwhile, in the late 1960s, in the midst of the hippie upheaval, Gloria Vanderbilt recommended the “little black dress” as always correct for dining in a fine restaurant. But informality was winning as women wearing pants gained acceptance even in luxury New York City restaurants in the early 1970s, a rule change stimulated no doubt by a damaging recession.

Meanwhile, in the late 1960s, in the midst of the hippie upheaval, Gloria Vanderbilt recommended the “little black dress” as always correct for dining in a fine restaurant. But informality was winning as women wearing pants gained acceptance even in luxury New York City restaurants in the early 1970s, a rule change stimulated no doubt by a damaging recession.

By the late 1970s dress codes had been relaxed to the point that many upscale restaurants were minimally satisfied if their customers at least wore “dressy casual,” which usually meant designer jeans, shirts with collars, and no short-shorts, tank tops, or halter tops. Some chains accepted t-shirts as long as they weren’t white, but everyone agreed that patrons had to wear some kind of shirt and shoes.

Today, as Alison Pearlman has written in her fine book Smart Casual, the bond between fancy formal restaurants and gourmet dining has been loosened further by affluent young professionals in the creative industries. If they wear hoodies and jeans to work they expect to do the same as they sample innovative dishes at a hip restaurant.

And yet, along with the relentless trend toward casual dress, the tendency to show off in public persists, possibly as strongly as in the late 1890s when women of New York’s “smart set” took to the cafes to display the latest fashions.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

July 31, 2016

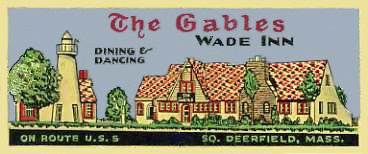

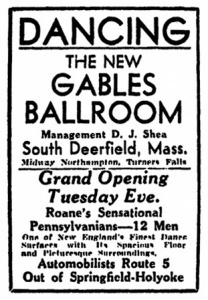

The Gables

I have a weak spot for corny roadside attractions, such as the scaled down lighthouse in front of The Gables restaurant in South Deerfield, Massachusetts, pictured here on a matchbook cover. The first time I saw it a while ago I wondered why it was there, and what the story was about the little commercial complex that appeared to be a bit down and out at that time.

And now I know – sort of. The lighthouse and its connected cottage were a gas station, while the main building was run as a roadside lunch spot when it began in business. Combination gas station/lunch rooms became commonplace in the 1920s and 1930s when more and more people began taking recreational drives through the countryside.

Exactly when the twin businesses were launched remains a question. My guess is the late 1920s, definitely by 1930, at which time they were operated by Charles M. Savage. He had long been a co-owner/manager of the Hotel Lathrop in South Deerfield, which was sold in 1928.

In 1931 a local builder completed a large building next door, south of The Gables. Oddly enough, it was intended as an indoor golf course, but instead was run as a dance hall by Dennis Shea, owner of the Shea Theater in Turners Falls, and later by a succession of others. Rudy Vallee and other nationally known acts performed there. In the 1950s it became a roller rink and then, in the 1970s, an auction house [pictured below as it looks now]. During its tenure as a dance hall and roller rink it was also known as The Gables, just like the restaurant (to confuse future researchers I’m sure!).

In 1931 a local builder completed a large building next door, south of The Gables. Oddly enough, it was intended as an indoor golf course, but instead was run as a dance hall by Dennis Shea, owner of the Shea Theater in Turners Falls, and later by a succession of others. Rudy Vallee and other nationally known acts performed there. In the 1950s it became a roller rink and then, in the 1970s, an auction house [pictured below as it looks now]. During its tenure as a dance hall and roller rink it was also known as The Gables, just like the restaurant (to confuse future researchers I’m sure!).

At the time the matchbook shown above was produced, The Gables restaurant was conducted by William Wade who also ran the Wade Inn on State Street in Northampton MA.

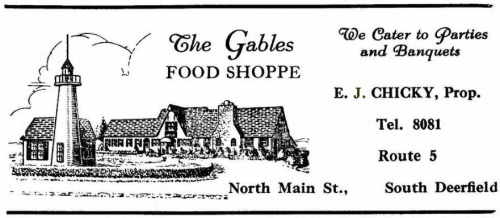

By 1936, The Gables restaurant had passed into the hands of Edward J. Chicky, also of Northampton. If the illustration in the advertisement from 1939 is accurate, the building had been extended on the left by then. It was now known as The Gables Food Shop, “food shop” being a popular name for a restaurant at the time.

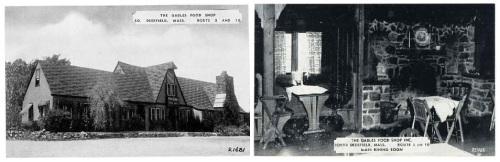

After Chicky, it was owned by others, including Guido “Guy” Zanone, previously proprietor of the Bernardston Inn, who bought it in 1941 [see above], then Frank and Veronica Shlosser in 1946. The Shlossers enlarged it in 1955, advertising in 1956 that it had colonial atmosphere and facilities for 350. It was a popular place for wedding receptions, club lunches, and business organization meetings.

The Shlossers continued to run it until the early 1970s, when it was sold again. It stayed in business as a restaurant and banquet house through most of the 1980s, serving beef, seafood, and chicken parmesan, among other dishes. Later it was occupied by an antique shop known as the Lighthouse.

Recently it has gone on the market once again. I wish someone would reopen it as a 1940s film-noirish roadhouse.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

July 17, 2016

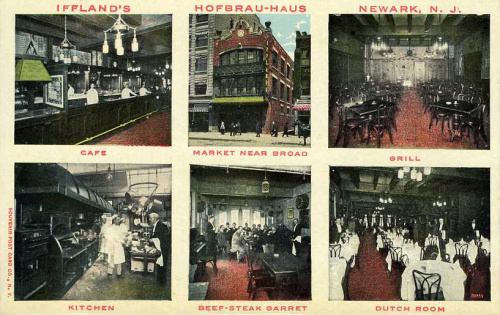

Find of the day: Iffland’s Hofbrau-Haus

Summer is the season for flea markets. A day at Brimfield this week yielded few thrills, unfortunately, yet I did find this interesting postcard of a Newark NJ restaurant.

Iffland’s was established on Market street in Newark in 1867, just one year after John Iffland immigrated from Germany at the age of 25. [He is pictured here at about 51.] A few years later he moved to 187 Market, the location shown on the postcard.

Iffland’s was established on Market street in Newark in 1867, just one year after John Iffland immigrated from Germany at the age of 25. [He is pictured here at about 51.] A few years later he moved to 187 Market, the location shown on the postcard.

Many of his patrons were businessmen, possibly of German heritage. Newark had a large German population. It also had many breweries, most of them run by German-Americans. Undoubtedly he served local beer, but he also imported beer from Germany. In the 1880s, when his business seemed to be more saloon than restaurant, Iffland ran advertisements in the German-language newspaper New Jersey Deutsche Zeitung announcing that he was serving beer imported from Munich. He also imported Salvator, a strong beer created to fortify those fasting during Lent.

It’s quite likely that by the time the postcard was produced, probably ca. 1910, John Iffland had retired and turned the business over to his two sons, Henry and John Jr. Perhaps it was they who installed the restaurant’s “beef-steak garret,” taking advantage of the popular fad for groups of men to hold dinners where they bonded while drinking beer and eating steaks with their bare hands. Possibly the restaurant’s kitchen was located in the basement, explaining why Iffland’s had a beefsteak garret rather than the typical “beefsteak dungeon” or “den” in an ominous looking cellar.

John Iffland died in 1917 and the business closed about that same time, allegedly because anti-German sentiment occasioned by the country’s entry into World War I on the side of the Allies against Germany, along with the impossibility of importing beer from Germany, had made it unprofitable.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

July 10, 2016

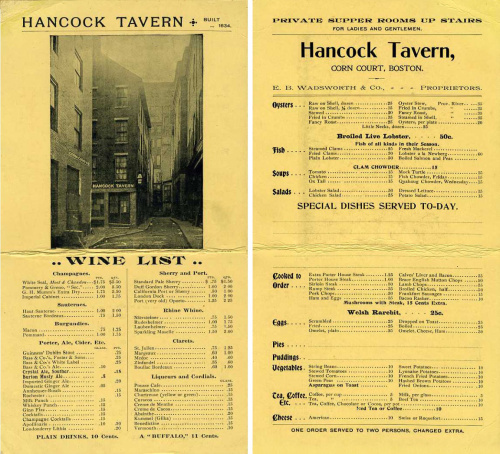

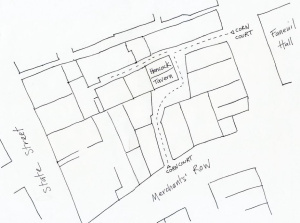

Find of the day: Hancock Tavern menu

When I found this menu from Boston’s Hancock Tavern [shown front & back] at a flea market my first question was how old it was. As soon as I began researching I learned that proprietor Wadsworth & Co. had taken over in 1897 and that the building pictured was torn down in the spring of 1903. That narrowed things down.

At that point I thought I knew enough to consider the question of the tavern’s history, starting with “Built 1634″ as noted on the menu.

Then, everything began to unravel, including the menu’s date.

I discovered that Edward & Lucina Wadsworth had reopened the Hancock Tavern in 1904 at “the identical site of the original historic structure.” Which had been razed. It took a while to figure that one out but I eventually determined that the reborn Hancock Tavern was located in the rear, Corn Court side, of a new office building facing on State Street. [sketch of map fragment shows Corn Court and Hancock Tavern in 1867]

I discovered that Edward & Lucina Wadsworth had reopened the Hancock Tavern in 1904 at “the identical site of the original historic structure.” Which had been razed. It took a while to figure that one out but I eventually determined that the reborn Hancock Tavern was located in the rear, Corn Court side, of a new office building facing on State Street. [sketch of map fragment shows Corn Court and Hancock Tavern in 1867]

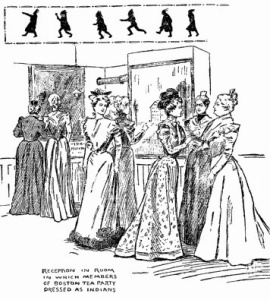

Then I found a story about a menu like mine found in a collection of items related to the Hancock Tavern — similar except that it said “Visit the Historic Tea Room Up Stairs. In this room the ‘Boston Tea Party’ made their plans, and dressed as Mohawk Indians to destroy the tea in Boston harbor, Dec. 16, 1773.” Since mine simply says “Private Supper Rooms Up Stairs for Ladies and Gentlemen,” I decided that it probably dates from the reincarnated Hancock Tavern, which would put it between 1904 and approximately 1910.

Much bigger mysteries surrounded the history of Hancock Tavern. By the late 19th century legends about the tavern abounded, beginning with the notion that it dated from 1634 as the continuation of a tavern begun by Samuel Coles. It was also said to have hosted John Hancock, exiled French king Louis Philippe, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and French foreign minister Talleyrand. But the grandest legend concerned the conspirators in the “Boston tea party.” Beginning in the 1880s, the various proprietors of the Hancock Tavern spun historic tales about this.

In December of 1898, the Daughters of the American Revolution, dressed as Colonial maids, met at the Hancock Tavern to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the tea party. On the wall was a somewhat more detailed inscription, likely put there by the Wadsworths: “In this room the Boston tea party made their plans and dressed as Mohawk Indians, and went to Griffin’s (now Liverpool) wharf, where the ships Beaver and Eleanor and Dartmouth lay, and threw overboard 342 chests of tea, Dec. 16, 1773.” Later, the Wadsworths produced a souvenir booklet of historic lore.

In December of 1898, the Daughters of the American Revolution, dressed as Colonial maids, met at the Hancock Tavern to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the tea party. On the wall was a somewhat more detailed inscription, likely put there by the Wadsworths: “In this room the Boston tea party made their plans and dressed as Mohawk Indians, and went to Griffin’s (now Liverpool) wharf, where the ships Beaver and Eleanor and Dartmouth lay, and threw overboard 342 chests of tea, Dec. 16, 1773.” Later, the Wadsworths produced a souvenir booklet of historic lore.

But the link between the tavern and the Revolution, as well as its ancient status, were thrown into doubt in 1903 when City Registrar Edward W. McGlenen announced that the just-razed building that had housed the Hancock Tavern had been erected between 1807 and 1812. Furthermore, he said, its predecessor on the same site, a two-story house, had not been granted a tavern license until 1790, ruling out any associations with the Revolution. He also showed that Samuel Coles’ Inn, reputedly built in 1634, was an entirely separate property, thereby demolishing the Hancock Tavern’s claim to be Boston’s oldest tavern. The legends, he said, had developed from a number of fanciful books and articles from the 19th century that were in conflict with town records.

And so my menu, though still more than 100 years old, lost some of its charm.

On the bright side, though, I learned a few things about the operation of 19th-century taverns. I learned that Mary Duggan, widow of the first licensee, ran the tavern for a number of years after her second husband died. In addition to supplying the finest liquors, she advertised in 1825 that she had engaged a “professed COOK” who would have soup ready from 10 to 12 o’clock (then the standard time to eat soup), and would prepare supper parties “at the shortest notice.”

I also realized how much turnover there was in the tavern business. During most of the 19th century the Hancock Tavern was leased out to a succession of proprietors who either handled its alcohol and food service or the entire operation, which included lodging.

It fell on hard days sometime before the Wadsworths took over in 1897. Their energetic attempts to raise its historic value may have sprung in part from the fact that it had spent some years as a gambling den. In a city with many old buildings, most Bostonians did not care about it.

Having the bad luck to be located in what was fast becoming Boston’s financial district, the building was doomed, but the legend of Hancock Tavern’s link to the tea party lived on. The Arkansas Gazette reported in 1976:

June 27, 2016

Cooking with gas

As part of my research into how restaurants worked in past times, I’ve looked into their cooking methods, in particular the kind of fuel they used. Like all nuts and bolts questions, it has been difficult to nail down.

As part of my research into how restaurants worked in past times, I’ve looked into their cooking methods, in particular the kind of fuel they used. Like all nuts and bolts questions, it has been difficult to nail down.

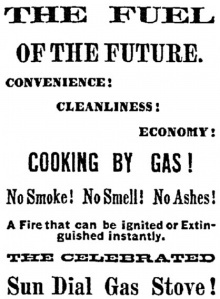

I wondered when public eating places began to switch from wood and coal to a more modern fuel such as gas. In the 19th century and well into the 20th, “artificial” gas was manufactured by heating coal. Gaslights were available as early as the mid-1810s in some places, and the first patent for a gas stove was given in the 1820s, but cooking with gas was rare, and didn’t occur in any public eating places that I could find.

I wondered when public eating places began to switch from wood and coal to a more modern fuel such as gas. In the 19th century and well into the 20th, “artificial” gas was manufactured by heating coal. Gaslights were available as early as the mid-1810s in some places, and the first patent for a gas stove was given in the 1820s, but cooking with gas was rare, and didn’t occur in any public eating places that I could find.

At least 50 urban areas had gas works making gas by 1850. In that decade a number of patents were granted for gas cooking stoves. Stoves were marketed for domestic use, but there is evidence that some commercial users were interested in them too. In 1853 the Astor House in New York City experimented with gas cooking by roasting a turkey. In 1855 a manager of the National Hotel in Washington, D.C., applied for a patent for a gas stove. By the late 1850s Shaw’s Gaslight Cook Stove was available. It could be attached to a gas line with a hard rubber tube and was described as useful in restaurants, especially in the summer because “the heat arising from it is scarcely perceptible.”

But coal remained the fuel most often used in restaurant and hotel kitchens for most of the 19th century and even into the 20th – despite its drawbacks. Roger Horowitz described in his book Putting Meat on the American Table how difficult cooking with coal could be, particularly for baking and roasting. Not only was the cook unable to see what was happening but also, he wrote: “The fire had to be monitored carefully, as opening the ‘drafts’ to admit oxygen could lead coals to burn too fast, but limiting the drafts too much made it hard to reach good cooking temperatures. As coal was slow and difficult to light, enough had to be introduced to supply sufficient temperatures and cooking duration; on the other hand, putting in too much coal could burn the meat or even damage the stove by overheating the fire box.”

A vivid picture of how coal stoves operated was painted by a NYT story in 1903. The reporter visited a large hotel with a battery of over 20 stoves lined up in a row. The heat was overpowering and it took four or five “firemen” to stoke the stoves so that the heat never flagged. The fires needed to be rebuilt about three times a day and two of the stoves were kept going at all times in case the kitchen received an order. Of course kitchens became dirty [see photo from 1916] and quantities of ashes had to be hauled out.

A vivid picture of how coal stoves operated was painted by a NYT story in 1903. The reporter visited a large hotel with a battery of over 20 stoves lined up in a row. The heat was overpowering and it took four or five “firemen” to stoke the stoves so that the heat never flagged. The fires needed to be rebuilt about three times a day and two of the stoves were kept going at all times in case the kitchen received an order. Of course kitchens became dirty [see photo from 1916] and quantities of ashes had to be hauled out.

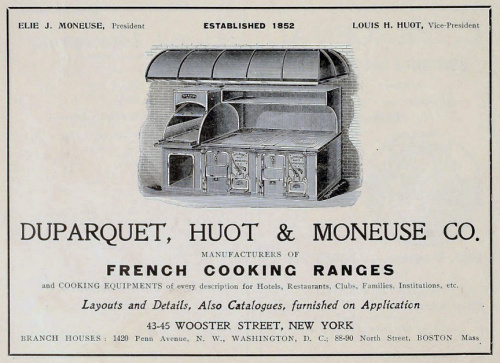

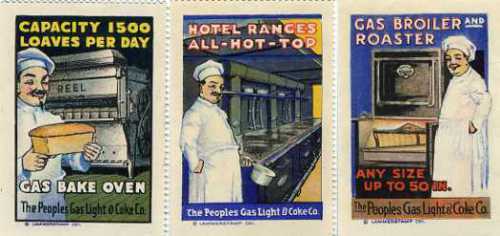

Whatever the shortcomings of coal, it would appear that most chefs preferred it, especially when grilling meat. Although a New Haven CT stove company advertised gas as “the fuel of the future” in 1879 [see above], it would remain merely a concept in professional kitchens for some time. Far more kitchens used French-inspired coal stoves such as those sold by the Duparquet company [pictured, 1910] or manufactured in San Francisco by the John S. Ils company. Delmonico’s adopted gas ranges but Chef Charles Ranhöfer announced in 1894 that he was going to have gas removed from the restaurant’s kitchen. He much preferred to cook with house-made charcoal. The Waldorf tried electric ranges but rejected them after a few weeks. Only a few chefs interviewed in a NYT story spoke up for gas, though the Hoffman House’s chef G. N. Nouvel overcame his reluctance and adopted gas in 1895, doing away with the problem of “having fires ready and just right.” He predicted its use would become universal in hotels and restaurants “sooner or later.”

The use of professional gas stoves advanced somewhat during World War I when coal prices went up. In New York City, the Consolidated Gas Company reported that it had replaced coal stoves in a large number of professional kitchens within a two-week period in 1917. The Hotel Knickerbocker’s three kitchens took out all coal-burning appliances, replacing them with 84 feet of gas ranges, nine salamanders, three broilers, and a number of smaller gas appliances. Healy’s, Browne’s, and Pabst’s were a few of the restaurants that got rid of coal and installed five or more sections of gas ranges. Similar events were taking place in Boston’s large kitchens. [see Schrafft’s modern gas kitchen, 1938, when NYC still depended on manufactured gas]

The use of professional gas stoves advanced somewhat during World War I when coal prices went up. In New York City, the Consolidated Gas Company reported that it had replaced coal stoves in a large number of professional kitchens within a two-week period in 1917. The Hotel Knickerbocker’s three kitchens took out all coal-burning appliances, replacing them with 84 feet of gas ranges, nine salamanders, three broilers, and a number of smaller gas appliances. Healy’s, Browne’s, and Pabst’s were a few of the restaurants that got rid of coal and installed five or more sections of gas ranges. Similar events were taking place in Boston’s large kitchens. [see Schrafft’s modern gas kitchen, 1938, when NYC still depended on manufactured gas]

Though it was available in certain areas sooner (Pittsburgh was the center of the industry in the 1880s), natural gas made its debut through much of the United States in the 1920s, encouraging its use in restaurants. It arrived in San Francisco in 1929, at a price lower than manufactured gas; in 1930 a survey revealed that gas was the main fuel for restaurant cooking in San Francisco, with coal a distant second. Electricity was commonly used for smaller appliances such as coffee urns, toasters, and waffle irons.

In the 1930s, two periodicals came out dedicated to the use of gas and electricity in restaurant and institutional kitchens. Cooking for Profit was launched in1932 by Gas Magazines, Inc., and Food Service, published by Electrical Information Publications, began in 1938. Both were filled with stories and advertisements for their respective energy sources and appliances, including Vulcan, Garland, and Hotpoint ranges. Stories in Food Service hailed restaurants and chains with all-electric kitchens such as the B&W Cafeteria in Nashville, while Cooking for Profit championed gas users such as the Greenbrier resort in West Virginia and the Nation of Islam’s Salaam restaurant in Chicago.

In the 1930s, two periodicals came out dedicated to the use of gas and electricity in restaurant and institutional kitchens. Cooking for Profit was launched in1932 by Gas Magazines, Inc., and Food Service, published by Electrical Information Publications, began in 1938. Both were filled with stories and advertisements for their respective energy sources and appliances, including Vulcan, Garland, and Hotpoint ranges. Stories in Food Service hailed restaurants and chains with all-electric kitchens such as the B&W Cafeteria in Nashville, while Cooking for Profit championed gas users such as the Greenbrier resort in West Virginia and the Nation of Islam’s Salaam restaurant in Chicago.

Natural gas was slow to arrive everywhere, including some large cities. New York City, Philadelphia, Boston and the rest of New England, Portland OR, Spokane and Seattle WA, Wisconsin, and Florida were not served with natural gas until after World War II, no doubt delaying the broad adoption of gas appliances in those places.

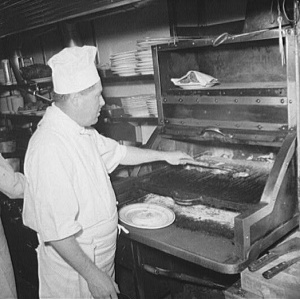

Today, most restaurants have both gas ranges and a variety of electric cooking devices, and perhaps a charcoal broiler too [pictured]. Might there even be a few chefs who swear by coal?

Today, most restaurants have both gas ranges and a variety of electric cooking devices, and perhaps a charcoal broiler too [pictured]. Might there even be a few chefs who swear by coal?

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

June 12, 2016

Ladies’ restrooms

Public restrooms have been in the news lately because of conflict over transgender rights, but I have been wondering about them for quite a while as part of my project to understand how restaurants developed.

Public restrooms have been in the news lately because of conflict over transgender rights, but I have been wondering about them for quite a while as part of my project to understand how restaurants developed.

We assume that restaurants will have restrooms for their customers today, but when did they become commonplace? And when did restaurants make an effort to specifically accommodate women with separate toilets? I am still not 100% sure about the answers.

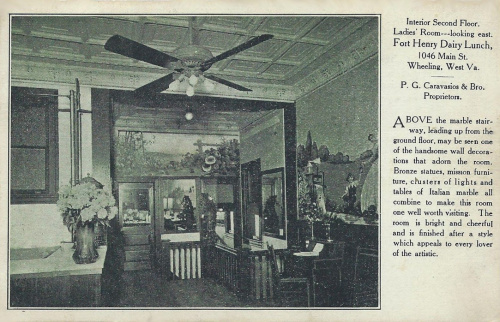

Researching the history of sanitary facilities in restaurants has proved to be very difficult, starting with what terms to search for. Even today both “bathroom” and “restroom” are somehow inadequate. Yet restroom is better to capture the historical fact that those restaurants that had facilities for women usually were outfitted with more than toilets and sinks. They also had space – and many still do – where women could take care of little chores such as repairing their hairdos, or simply rest. [restroom shown below, ca. 1920s]

Prior to the 1860s, most public toilets were outdoors, behind saloons and restaurants, and the same was true of private dwellings. Flush toilets were quite rare in the United States until the 1880s, according to Suellen Hoy’s 1995 book Chasing Dirt: The American Pursuit of Cleanliness. Outhouses were commonplace throughout the 19th century and well into the 1930s in homes in rural areas and poor neighborhoods.

The earliest ladies’ restroom I’ve found in a restaurant was in an elegant Chicago hotel. It’s likely that other hotels were similarly equipped, even though hotel bedrooms with private bathrooms were rare. According to a story in 1864, the Chicago restaurant welcomed women diners and invited them to simply “call in for a rest, without intrusion, or being thought an intruder.” “Every provision has been made for the convenience of ladies,” the story said, “and a toilet-room specially apportioned to their use.” This would have been welcome news to women at a time when public accommodations for them were sorely lacking.

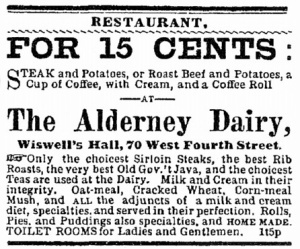

The restaurants that had toilets and restrooms for women seem to have been the more substantial ones that enjoyed prominence in their communities, as was often true of restaurants in leading hotels. So it was surprising to discover that an inexpensive lunch room, Cincinnati’s Alderney Dairy, had a toilet room for women in 1878.

Though still rare, the number of ladies’ rooms in restaurants grew in the 1880s with the spread of indoor plumbing and city sewers. According to a story from 1889, restrooms in fashionable restaurants were “sumptuously furnished” with velvet couches, floor to ceiling mirrors, and marble basins. Perfumes, face powders, rouges, lotions, ivory brushes and combs, as well as hat pins were supplied.

Yet, to put the lavish restroom described above into context, the supply of ladies’ rooms in restaurants and offices was still inadequate in the 1890s. In 1891 a restaurant in Portland ME felt justified to advertise that it had “the finest Ladies’ room east of Boston,” a considerable area. Often tall office buildings were constructed with ladies’ rooms only on the top floor. Even though women were increasingly taking jobs as clerical workers in offices, developers did not want to give up income-earning space to facilities for women on each floor. (Men, on the other hand, were supplied with small closets with a urinal-sink on each floor.)

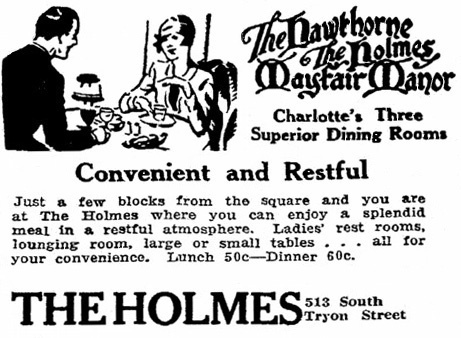

Although the 1890s is often cited as the decade in which indoor plumbing took huge leaps, it is notable that restaurants continued to advertise ladies’ rest rooms throughout the 1920s [above advertisement, 1930], indicating that it had not yet become something that could be taken for granted despite the increase in women going to restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

May 15, 2016

All you can eat

Except for the patrons of rarefied restaurants for whom exquisitely hand-crafted miniature food represents the triumph of artistic appreciation over animal hunger, most people like food in quantity. Even if they do not eat a great deal, they like the idea that they could if they wanted to.

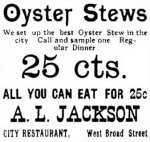

Restaurants advertising free seconds — or thirds — can be found in the 19th century, one example being the City Restaurant in Elyria OH in 1896 [shown here]. But it wasn’t until the Depression of the 1930s that the all-you-can-eat idea became a newsworthy phenomenon. In response to declining business, restaurants such as Childs in the East and Boos Brothers in the West took advantage of falling food prices by offering patrons as much of whatever they wanted for a set price of 50 or 60 cents.

Restaurants advertising free seconds — or thirds — can be found in the 19th century, one example being the City Restaurant in Elyria OH in 1896 [shown here]. But it wasn’t until the Depression of the 1930s that the all-you-can-eat idea became a newsworthy phenomenon. In response to declining business, restaurants such as Childs in the East and Boos Brothers in the West took advantage of falling food prices by offering patrons as much of whatever they wanted for a set price of 50 or 60 cents.

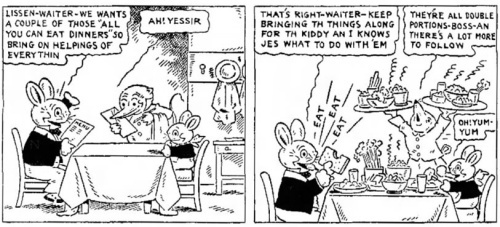

In this Depression experiment restaurant proprietors learned something important about how people react when offered unlimited food. A few people went crazy, stuffing down as much as they could [below: Peter Rabbit cartoon by Harrison Cady, 1933], but most didn’t eat more than they normally would. If they overindulged in anything, it was desserts.

All-you-can-eat as an adaptation to challenging economic conditions did not altogether disappear with the end of the Depression. Many restaurants found that having one night a week when they offered a special deal on a particular food, especially fried chicken or fish, could fill the house on a perpetually slow weeknight or help to build business generally.

Smorgasbords based on Swedish hors d’oeuvres tables also made their debut in the 1930s. At Childs and other Depression all-you-can-eat restaurants patrons relied on a server to bring their order, but smorgasbords introduced a novel approach: patrons helped themselves to relishes and appetizers from an attractively laid out table, and were then served with their main course as in a traditional restaurant.

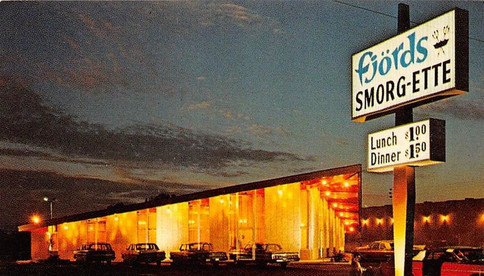

The smorgasbord idea, it turned out, was a step on the way to the all-you-can-eat buffet. In the 1950s and 1960s chains developed whose entire business plans were based on bargain-priced buffets abounding with macaroni and cheese, chow mein, fried chicken wings, and “sparkling salads,” i.e. jello. Chains divested smorgasbords of their ethnic overtones even as some continued to call themselves by that name. In California, the word “smorgy” emerged (variations included smorga, smorgee, & smorg-ette). Rather than using round smorgasbord serving tables with food presented in decorative bowls and platters, high-volume chains tended toward cafeteria-type service with stainless steel pans.

California smorgys displayed seeming cultural diversity, with Ramona’s Smorgy, Mario’s Smorgy, and Gong Lee’s Smorgy. I’m still trying to grasp the concept behind Johnny Hom’s Chuck Wagon/Hofbrau/Smorgy in Stockton CA, the town that may have merited the title of smorgy capital of the U.S.A.

Along with the Swedish smorgasbord tradition, the spread of buffets and smorgys nationwide may have been aided by the $1.50 midnight spreads in Las Vegas casinos, which in the 1950s gave all-you-can-eat a popular culture imprimatur.

Opinion has been divided as to whether all-you-can-eat (or the more genteel “all-you-care-to-eat”) restaurants tended to serve cheap and inferior food. Many restaurants stressed that they baked daily, made their own sauces, or used fresh vegetables. “At Perry Boys’ Smorgy Restaurant, an inexpensive price doesn’t mean a cheap product,” according to an advertisement listing brand name foods in use. Yet, a 1968 restaurant trade journal seemed to suggest otherwise judging from its advice that “attractive buffet fare based on low-cost foods is essential.” For Quick Chicken Tetrazzini, it recommended mixing pre-cooked diced chicken with condensed mushroom soup and serving it over noodles.

As popular as all-you-can-eat restaurants were in the 1960s and 1970s, they suffered in the public relations department. They often undermined their own mini-industry with insults slung at each other. Is it helpful while touting your own restaurant to remind the public that “the words ‘all you can eat’ often mean quantity at the expense of quality”? And what does it say about the many restaurants advertising fried perch specials when a competitor says of its fish: “This is NOT frozen perch”?

Likewise some operators took an unfortunate “the customer is not always right” stance by posting signs that warned patrons to take no more than they could eat [see above]. This was directed at those, admittedly a small minority (but still!), who came equipped with plastic-lined handbags or special pouches in their coats in which to stow food to carry away. Meanwhile, other proprietors denounced these warning signs as an insult to guests.

Customers with huge appetites were another species of problem that most all-you-can-eat restaurants tried to be philosophical about, figuring above-average consumption would be balanced by the light eaters. Proprietors told themselves that the man who downed 90 steamed clams, or the one who swallowed 40 pieces of fried chicken, would provide free advertising when he boasted at work how much he ate. Families were prized customers, construction gangs less so. And they dreaded school football teams. Some restaurants located near the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor found it necessary to put restrictions on salad bars.

Let’s face it, since the fall of Rome, gorging has been seen as unattractive. Restaurant owners and employees sometimes expressed disgust at customer behavior such as grabbing food off trays as staff tried to replenish buffets. “It’s disgusting,” said the proprietor of a Dallas all-you-can-eat steak restaurant, adding, “Some of them just ought to be led off to a big, old hog trough.” Another manager admitted that workers called customers “animals” in private. “You lose your appetite working in a place like this,” said one.

As a reporter wrote of Las Vegas buffets in 1983, “If I ever see another metal pan of mashed potatoes awash in melted margarine, another sea of macaroni salad, another ‘medley’ of canned corn, carrots and peas . . .” Stop right there!

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

April 24, 2016

Taste of a decade: 1880s restaurants

In the 1880s a wider range of foods became available to people living in cities, allowing restaurant menus to became more varied. Cold storage warehouses and refrigerated rail cars brought cheaper Chicago beef and out-of-season produce. Mechanically frozen ice, free from the impurities of lake ice, became available. Cheese and butter, once made on farms, now came from factories. Fresh fruits and vegetables remained luxuries for most people, however, and meat and potatoes dominated menus.

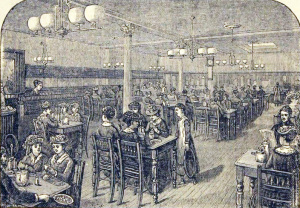

Larger, better capitalized restaurants installed electric plants that provided brighter lighting and badly needed ventilation systems.

The public demanded, and began to get, lower restaurant prices, quicker service, and more flexible meal times. The dining public expanded. Boarding houses that furnished meals as part of the rent were replaced by kitchenless rooming houses whose residents went to restaurants for dinner. More hotels switched to the European plan, freeing guests to eat wherever they chose rather than pay an inclusive charge for room and meals. New types of ready-to-eat food purveyors came on the scene, such as all-night lunch wagons and dairy cafes that specialized in simple, inexpensive meals such as baked beans and cereal with milk.

The public demanded, and began to get, lower restaurant prices, quicker service, and more flexible meal times. The dining public expanded. Boarding houses that furnished meals as part of the rent were replaced by kitchenless rooming houses whose residents went to restaurants for dinner. More hotels switched to the European plan, freeing guests to eat wherever they chose rather than pay an inclusive charge for room and meals. New types of ready-to-eat food purveyors came on the scene, such as all-night lunch wagons and dairy cafes that specialized in simple, inexpensive meals such as baked beans and cereal with milk.

New ethnic groups arrived on American shores, among them Eastern European Jews and Southern Italians. Many settled in the East but others spread to cities throughout the westward-growing nation. They brought with them new cuisines, tempting the more adventurous eaters among the settled population.

Temperance coffee houses and soda fountains continued to thrive, particularly in Boston where authorities were always looking for ways to curb drinking.

As the rise of department stores and downtown retail shops brought women into city centers, restaurants catering specifically to them appeared on the scene.

But not everyone was welcome at restaurant tables, or in the society at large. Southern states made segregation the law, keeping Black Americans out of white-owned restaurants. Racially motivated legislation cut off Chinese immigration to the U.S. and encouraged hostility toward Chinese already in the country, mostly in the West, motivating many to move eastward and introduce curious diners to new foods.

Highlights

1880 On the second floor of its newly expanded NYC department store, Macy’s restaurant for shoppers seats 200. – In the silver-mining town of Virginia City NV, restaurants serve food from all over the world, including “fruits from every country and clime.”

1880 On the second floor of its newly expanded NYC department store, Macy’s restaurant for shoppers seats 200. – In the silver-mining town of Virginia City NV, restaurants serve food from all over the world, including “fruits from every country and clime.”

1881 In December, Edmund Hill, proprietor of Hill’s confectionery restaurant in Trenton NJ totals up the proceeds of what he calls a “very satisfactory” year in which the business took in $18,146, netting him the handsome sum of $677.33 in wages and profit.

1882 Richmond’s Café in New Bedford MA informs customers that “The Café will be in charge of a lady . . . who will bestow especial pains upon lady patrons, taking charge of whatever parcels may be left in her care while the owners are out shopping.” – In Boston Charles Eaton and a partner open a temperance soda fountain and lunch room called Thompson’s Spa which goes on to become a local institution.

1882 Richmond’s Café in New Bedford MA informs customers that “The Café will be in charge of a lady . . . who will bestow especial pains upon lady patrons, taking charge of whatever parcels may be left in her care while the owners are out shopping.” – In Boston Charles Eaton and a partner open a temperance soda fountain and lunch room called Thompson’s Spa which goes on to become a local institution.

1883 One year after passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Rockaway Oyster and Chop House in Fresno CA advertises to prospective customers that it has “all white help.” Everyone, of course, understands that white means “not Asian.”

1885 In Boston and other large cities customers flood into cheap restaurants near railroad depots and wharves for 10-cent noon meals. Menus are chalked up on boards and customers eat rapidly without removing coats or hats.

1885 In Boston and other large cities customers flood into cheap restaurants near railroad depots and wharves for 10-cent noon meals. Menus are chalked up on boards and customers eat rapidly without removing coats or hats.

1886 It is considered newsworthy when a federal judge orders a restaurant in Little Rock AR to serve a Black juror along with his fellow white jurors. A report notes that it was “the first time a negro enjoyed his repast at the leading hotel in the state and among white people.”

1887 After gathering menus from 40 prominent hotels from all over the country, a collector determines that salmon is the fish most often listed, and that it is found on menus across the United States, including Knoxville TN, Detroit MI, Milwaukee WI, Salt Lake City UT, and Cheyenne WY.

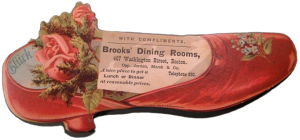

1888 At Chicago’s New York Kitchen, where a nickel buys Ham and Beans Boston Style or “One-third of a Pie, any kind,” the dining room is lighted by a Mather Incandescent Electric System and cooled by a steam-powered exhaust fan. — In Boston Brooks’ Dining Rooms is equipped with a telephone.

1888 At Chicago’s New York Kitchen, where a nickel buys Ham and Beans Boston Style or “One-third of a Pie, any kind,” the dining room is lighted by a Mather Incandescent Electric System and cooled by a steam-powered exhaust fan. — In Boston Brooks’ Dining Rooms is equipped with a telephone.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016