Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 27

April 13, 2016

Anatomy of a corporate restaurant executive

It strikes me that much more has been written about and by chefs than those restaurant personnel who mostly work behind a desk. Business people lack the glamour of knife wielding chefs. They are not surrounded by flames. They have no dishes named after them.

It strikes me that much more has been written about and by chefs than those restaurant personnel who mostly work behind a desk. Business people lack the glamour of knife wielding chefs. They are not surrounded by flames. They have no dishes named after them.

But Frederick Rufe’s career in restaurants was as interesting as many chefs’ and he was undoubtedly more influential in shaping the dining experiences of countless restaurant patrons over his career of nearly 40 years. His entire working life had a single focus. In a 1974 interview he stressed, “Everything I’ve ever done has been with food.” As a management executive he was closer to the soul (or soullessness, depending how you see it) of both the upscale and the midscale American corporate-owned restaurant of the 1960s and 1970s.

Born in New Jersey in 1922 he came from a humble background, growing up in a one-parent household with his mother, who was a factory worker, and a brother. While a student at a teachers’ college, he spent one summer as a waiter for a Pennsylvania resort, leading him to detour from a teaching career to one in food service. Following WWII army duty (working in food supply), he obtained a degree from Cornell’s School of Hotel Administration, which excelled in turning out top hospitality industry executives.

He then went to work in Miami Beach as food and beverage manager at large hotels there, among them the Monte Carlo, Algiers, and Deauville. He was not shy about promoting himself. Aiming for a catering manager job in a hotel without such a position, he “invented” it for himself. He took over a vacant room, bought a desk, put up draperies, and hung out a “Catering Manager” sign. When challenged by his boss, he successfully convinced him that the hotel needed someone – him – in that position.

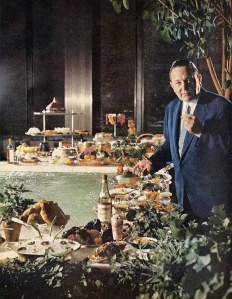

He joined Restaurant Associates in New York in the mid-1950s as the company was entering its most creative phase. RA was going from managing coffee shops and cafeterias to developing theme restaurants, some in the luxury class. In 1956 Rufe was made general manager of RA’s Newark Airport restaurants which included the famed Newarker, its kitchen headed by the inventive Swiss chef Albert Stöckli who would go on to the Four Seasons [pictured here]. Rufe helped develop the Four Seasons, the Forum of the Twelve Caesars, and La Fonda del Sol. At a time when out-of-season fruits and vegetables equalled the height of luxury, he obtained shipments of melons and new asparagus from the West for the Four Seasons, as well as miniature vegetables that allowed power-lunching VIPs to minimize awkward bites. With James Beard’s help he brought the blind cook Elena Zelayeta from California to plan Mexican and Spanish dishes for La Fonda del Sol.

He joined Restaurant Associates in New York in the mid-1950s as the company was entering its most creative phase. RA was going from managing coffee shops and cafeterias to developing theme restaurants, some in the luxury class. In 1956 Rufe was made general manager of RA’s Newark Airport restaurants which included the famed Newarker, its kitchen headed by the inventive Swiss chef Albert Stöckli who would go on to the Four Seasons [pictured here]. Rufe helped develop the Four Seasons, the Forum of the Twelve Caesars, and La Fonda del Sol. At a time when out-of-season fruits and vegetables equalled the height of luxury, he obtained shipments of melons and new asparagus from the West for the Four Seasons, as well as miniature vegetables that allowed power-lunching VIPs to minimize awkward bites. With James Beard’s help he brought the blind cook Elena Zelayeta from California to plan Mexican and Spanish dishes for La Fonda del Sol.

Amiable and worldly, Rufe could be mistaken for a European sophisticate. He was on James Beard’s holiday dinner guest list, and had easy access to the food columns at major newspapers where he promoted RA’s restaurants with recipes and interviews. While manager of the Latin-themed La Fonda del Sol, he explained to a reporter that a “broiling wall” of revolving stuffed flank steaks was based on a setup he had observed at an inn in Peru on a menu-collecting tour of South America with La Fonda’s chef John Santi. He was known for focusing on detail, so much so that his travel notes were said to look like research for a doctoral dissertation.

Amiable and worldly, Rufe could be mistaken for a European sophisticate. He was on James Beard’s holiday dinner guest list, and had easy access to the food columns at major newspapers where he promoted RA’s restaurants with recipes and interviews. While manager of the Latin-themed La Fonda del Sol, he explained to a reporter that a “broiling wall” of revolving stuffed flank steaks was based on a setup he had observed at an inn in Peru on a menu-collecting tour of South America with La Fonda’s chef John Santi. He was known for focusing on detail, so much so that his travel notes were said to look like research for a doctoral dissertation.

In 1964 he took on the task of rescuing the Top of the Fair, a failing de luxe restaurant atop the Port Authority’s heliport building adjoining the World’s Fair grounds. He was made a RA vice-president in 1967 and two years later put in charge of food operations at LaGuardia and Kennedy air terminals, as well as other airports in the Northeast. “Our places are genuine restaurants,” he insisted, “not just places to grab a quick meal and dash to your plane.”

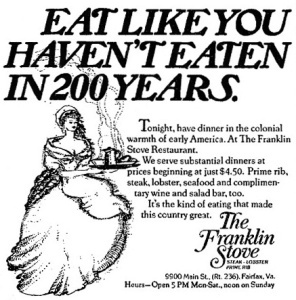

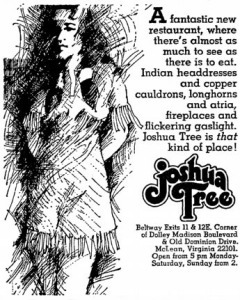

After a shift in RA’s direction, Rufe left for the Marriott Corporation where he was soon made VP of its dinner house division of moderate-priced theme restaurants in the DC area. The recession of the 1970s was on and Rufe explained in the press that Americans wouldn’t pay for $25 French dinners any more. Marriott’s new dinner houses were geared to more modest lifestyles. Phineas Prime Rib, Joshua Tree, Franklin Stove, Port O’Georgetown, and Garibaldi’s were management-driven eating places where every detail was arrived at through consumer research and economic calculation. Lunch was not profitable, so dinner only. No reservations because that resulted in less than 100% occupancy. Short menus with only America’s favorites, beef and seafood. All-you-can-eat salad bars. Fireplaces and ceiling beams evoking old-time hospitality. Friendly college student servers speaking from scripts. Cooking by step-by-step recipe cards. No chefs.

After a shift in RA’s direction, Rufe left for the Marriott Corporation where he was soon made VP of its dinner house division of moderate-priced theme restaurants in the DC area. The recession of the 1970s was on and Rufe explained in the press that Americans wouldn’t pay for $25 French dinners any more. Marriott’s new dinner houses were geared to more modest lifestyles. Phineas Prime Rib, Joshua Tree, Franklin Stove, Port O’Georgetown, and Garibaldi’s were management-driven eating places where every detail was arrived at through consumer research and economic calculation. Lunch was not profitable, so dinner only. No reservations because that resulted in less than 100% occupancy. Short menus with only America’s favorites, beef and seafood. All-you-can-eat salad bars. Fireplaces and ceiling beams evoking old-time hospitality. Friendly college student servers speaking from scripts. Cooking by step-by-step recipe cards. No chefs.

At first the formula was wildly popular with modal guests – suburbanites with $15,000 annual incomes who ordered $6.95 meals and cleared out in 1.5 hours. “Seventeen million dollars and no chefs,” Rufe boasted in January of 1975. However, by 1978 competition was up and profits were down. Marriott decided to sell off its dinner house division and some of the restaurants closed under the new owner.

At first the formula was wildly popular with modal guests – suburbanites with $15,000 annual incomes who ordered $6.95 meals and cleared out in 1.5 hours. “Seventeen million dollars and no chefs,” Rufe boasted in January of 1975. However, by 1978 competition was up and profits were down. Marriott decided to sell off its dinner house division and some of the restaurants closed under the new owner.

After a few years as director of food and beverage planning and development for Hilton International, Rufe retired, returning to Stroudsburg PA where he continued as a consultant.

Needless to say, the chain dinner house formula he helped develop prevails today, demonstrating that there is a sizable market for restaurants with pleasant decor, parking, clean bathrooms, and palatable fare that is affordable.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

March 28, 2016

Surf ‘n’ turf

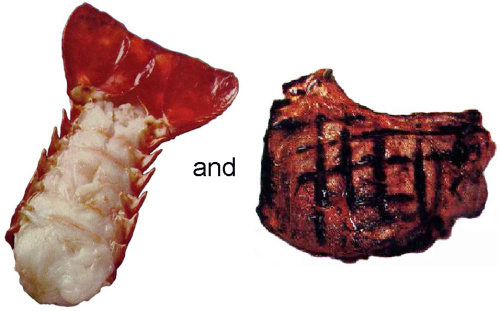

In the 1960s steak and seafood dinners became popular across the U.S. The lobster component of the dinner was frozen lobster tails from South Africa. Since the 1930s South African lobster tails had been appearing on restaurant menus. In 1937 Naylor’s Sea Food Restaurant in Washington D.C. offered a simple $1.00 Lenten special of Broiled African Lobster Tails with Drawn Butter, French Fried Potatoes, and Sliced Tomatoes.

In the 1960s steak and seafood dinners became popular across the U.S. The lobster component of the dinner was frozen lobster tails from South Africa. Since the 1930s South African lobster tails had been appearing on restaurant menus. In 1937 Naylor’s Sea Food Restaurant in Washington D.C. offered a simple $1.00 Lenten special of Broiled African Lobster Tails with Drawn Butter, French Fried Potatoes, and Sliced Tomatoes.

The imported lobster tails roused Maine to mount a campaign to convince consumers to stick with Maine’s lobsters. Advertisements appeared in newspapers in 1937 stating that frozen lobster tails were inferior to Maine lobster, and in fact weren’t lobster at all! Rather, the notices said, they were clawless crawfish, aka spiny or rock lobsters. At that time, South African lobster tails – the only edible part as far as humans were concerned – were being sold at 1/3 the price of Maine’s. In 1938 Maine lobsters appeared in the marketplace with an aluminum disk attached to the claw stating they were a product of Maine.

The imported lobster tails roused Maine to mount a campaign to convince consumers to stick with Maine’s lobsters. Advertisements appeared in newspapers in 1937 stating that frozen lobster tails were inferior to Maine lobster, and in fact weren’t lobster at all! Rather, the notices said, they were clawless crawfish, aka spiny or rock lobsters. At that time, South African lobster tails – the only edible part as far as humans were concerned – were being sold at 1/3 the price of Maine’s. In 1938 Maine lobsters appeared in the marketplace with an aluminum disk attached to the claw stating they were a product of Maine.

Despite the campaign, imported lobster tails did not stop arriving from South Africa. After WWII a NY importer began flying them in from Cuba. Soon big shipments were also coming from Brazil, Australia, and New Zealand.

Despite the campaign, imported lobster tails did not stop arriving from South Africa. After WWII a NY importer began flying them in from Cuba. Soon big shipments were also coming from Brazil, Australia, and New Zealand.

I had hoped to figure out why it was not until the early 1960s that restaurants began to combine lobster tails with beef, calling the combination surf ‘n’ turf, beef ‘n’ reef, etc. So far I haven’t been able to “crack” that one. It wasn’t a totally novel idea: in 1931, for instance, the LaJolla Beach & Yacht Club offered a “special steak and lobster dinner” for $1. Yet it took 30 more years after the cheaper lobster tails came to America for the surf ‘n’ turf vogue to begin.

Even though they could be dry and somewhat tough compared to Maine lobsters, ever-practical American diners liked rock lobster tails because it was easier to get the meat out of the shell without making a mess.

In 1964, a restaurant in Van Nuys CA combined steak and lobster tails for $3.00, making the combo cheaper than a steak dinner and affordable enough that it quickly caught on around the country as a “special dinner,” one likely to be chosen by middle-class diners for an anniversary or New Year’s Eve. Surf ‘n’ Turf was not likely to appear on the menus of luxury restaurants — but let’s be honest – there were very few luxury restaurants then, and even now they make up a small percentage of all restaurants. It was a dish more suited to a middle-class restaurant such as Schrafft’s, which in 1970 ran humorous advertisements suggesting their “Beef and Reef” platter was perfect “for executives who are tired of making important decisions.”

In 1964, a restaurant in Van Nuys CA combined steak and lobster tails for $3.00, making the combo cheaper than a steak dinner and affordable enough that it quickly caught on around the country as a “special dinner,” one likely to be chosen by middle-class diners for an anniversary or New Year’s Eve. Surf ‘n’ Turf was not likely to appear on the menus of luxury restaurants — but let’s be honest – there were very few luxury restaurants then, and even now they make up a small percentage of all restaurants. It was a dish more suited to a middle-class restaurant such as Schrafft’s, which in 1970 ran humorous advertisements suggesting their “Beef and Reef” platter was perfect “for executives who are tired of making important decisions.”

The public’s love of lobster tails paired with steak continued through the 1970s, even as prices rose. By the late 1970s Surf ‘n’ Turf could easily run to $11.95 and more, and in Washington, D.C. restaurants were caught substituting Florida tails for the superior South African ones. By the 1990s, S&T’s desirability had faded. No doubt it can still be found today here and there, but, like cheesecake and baked potatoes with sour cream and chives, it would scarcely be the restaurant sensation it was in the 1960s and 1970s.

The public’s love of lobster tails paired with steak continued through the 1970s, even as prices rose. By the late 1970s Surf ‘n’ Turf could easily run to $11.95 and more, and in Washington, D.C. restaurants were caught substituting Florida tails for the superior South African ones. By the 1990s, S&T’s desirability had faded. No doubt it can still be found today here and there, but, like cheesecake and baked potatoes with sour cream and chives, it would scarcely be the restaurant sensation it was in the 1960s and 1970s.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

March 20, 2016

Odd restaurant buildings: “ducks”

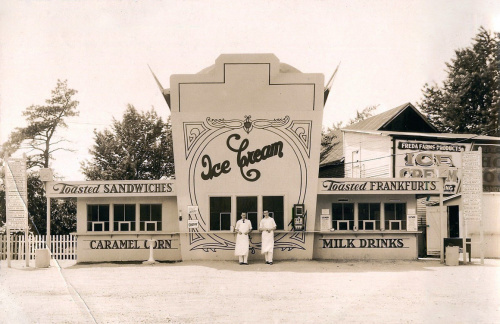

Ducks are commercial buildings that look like what they sell, as illustrated by the Freda Farms ice cream stand in Berlin CT. The term was actually inspired by a Long Island store that sold ducks (to eat). It has been generalized to apply to any buildings that looks like some familiar object or animal, etc, whether or not their merchandise is related. These types of buildings are also known as programmatic or mimetic architecture.

Though they reached a peak of popularity in the late 1920s and early 1930s, ducks trace back much further in history. An introduction to Jim Heimann’s book California Crazy by David Gebhard links the mimetic architecture of the last century to garden buildings of the 18th century and even earlier. One of the first examples in the United States was the 65-foot elephant of Margate NJ built in1881 to attract attention to a real estate development.

Though they reached a peak of popularity in the late 1920s and early 1930s, ducks trace back much further in history. An introduction to Jim Heimann’s book California Crazy by David Gebhard links the mimetic architecture of the last century to garden buildings of the 18th century and even earlier. One of the first examples in the United States was the 65-foot elephant of Margate NJ built in1881 to attract attention to a real estate development.

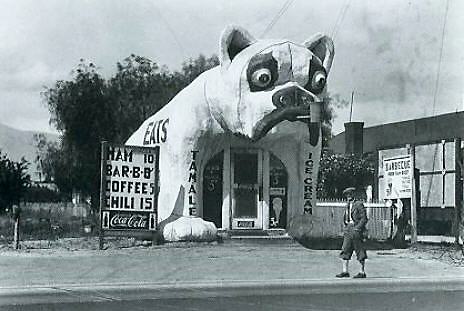

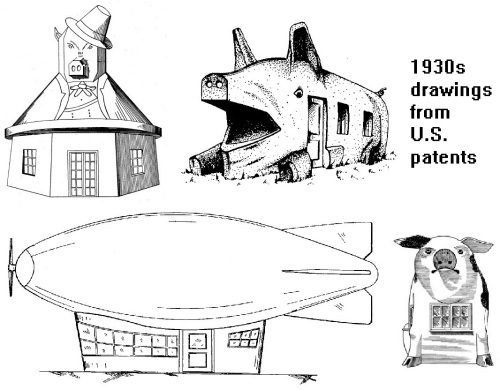

In addition to housing stores and offices, many ducks have featured restaurants over the decades. They have taken the shape of all kinds of animals, kegs, barrels, ships, castles, cups, coffee pots, bowls, hats, chuck wagons, dirigibles, items of food, shoes, and windmills.

The earliest duck I have found was a café planned for Cincinnati in the shape of a huge beer cask in 1902. Unlike later examples, though, it was meant to occupy a location in a row of Main Street storefronts. Most later ducks, arriving with the spread of car ownership in the late 1920s and early 1930s, occupied empty lots in developing areas of cities. Not too surprisingly, southern California’s car culture provided a nurturing environment. In addition the climate was favorable to the somewhat makeshift carnival-type structures, while the city’s movie industry supplied inspiration. As Los Angeles grew, giant dogs, toads, ice cream freezers, shoes, and other bizarre apparitions sprang up along the roadside, vying for the business of passing motorists.

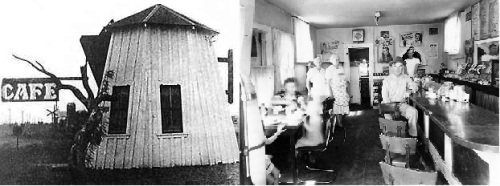

The link between the movie industry and roadside fantasy was straightforward in the case of Harry Oliver, a leading designer who brought magic to sets for movies such as Scarface, The Good Earth, and Mark of the Vampire. Oliver designed windmill-shaped buildings for the Van de Kamp bakeries and drive-ins as well as a storybook building occupied by the Tam o’ Shanter Inn.

If architecture is about the enclosure of space, ducks are architecture only secondarily. In most cases mimetic architecture describes a building that serves more as advertising sign than as an innovative enclosure of space. Once a customer stepped inside a giant pig or coffee pot, all whimsy faded away as the interior revealed itself to be a standard rectangle as shown here in one of the many coffee-pot ducks that could be found across the U.S.

If ducks say anything about American restaurants, it is that they are only partially about food.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

March 6, 2016

Dining with the Grahamites

In the early 19th century many Americans had fairly wretched meals at home. No doubt some fared better but the historical record is full of spoiled meat, rancid butter and fats, sour bread, and rotting fruit. Diets were heavy with meats, fried food, and pastries, but few fresh fruits or vegetables. Strong condiments were used to hide bad tastes. Heavy drinking was common as was “dyspepsia” (indigestion).

In the early 19th century many Americans had fairly wretched meals at home. No doubt some fared better but the historical record is full of spoiled meat, rancid butter and fats, sour bread, and rotting fruit. Diets were heavy with meats, fried food, and pastries, but few fresh fruits or vegetables. Strong condiments were used to hide bad tastes. Heavy drinking was common as was “dyspepsia” (indigestion).

In this context, the dietary reforms advocated by Sylvester Graham in the 1830s seem somewhat less extreme than they are often portrayed. A graduate of Amherst College and a Presbyterian minister, he began his career at a church in New Jersey but soon left to take a job with a temperance organization. Upon expanding his belief that drinking was morally and physically unhealthy by including foods and non-alcoholic beverages that should also be avoided, he went on the circuit as an independent lecturer.

Hoping to curb “unnatural appetites”(yes, of all kinds), Graham identified foods that should not be eaten because they were overstimulating. In addition to alcohol, they were coffee, black and green tea, and condiments such as pepper and mustard. He also targeted all meat and foods that were indigestible, among them raw cucumbers and radishes, gravies, melted butter, pastry, and cakes. He believed the perfect consumables were bread and water, assuming the bread was unbuttered, made of whole wheat flour, and baked by a female family member, not by a servant or commercial baker.

Graham was disliked for being overbearing and ridiculed as a scientific fraud, but his lectures and books nonetheless won fervent disciples, including a number of well-known abolitionists. A few of his followers started boarding houses for “Grahamites.” So far I have found three in New York City, two in Boston, and one in Rochester NY in the 1830s and 1840s.

Graham was disliked for being overbearing and ridiculed as a scientific fraud, but his lectures and books nonetheless won fervent disciples, including a number of well-known abolitionists. A few of his followers started boarding houses for “Grahamites.” So far I have found three in New York City, two in Boston, and one in Rochester NY in the 1830s and 1840s.

Like all boarding houses, Graham houses often operated as small hotels, with some guests staying for months, maybe years, but also transients who might be there for only a couple of days. Some guests only ate at the house, either regularly or for a single meal. The houses were small and could not accommodate many diners; certainly they were not full-scale restaurants, yet they were public eating places of a sort.

Graham boarding houses ascribed to Graham’s scientific system of living. Though mostly focused on diet, it also emphasized taking daily cold showers and sleeping on straw mattresses rather than feather beds. Meals – consisting of no more than three items — were to be eaten six hours apart at the same precise time every day. A sample Graham diet for one of the boarding houses was advertised in the New York Tribune in 1843 as follows:

Monday – Pea soup, vegetables, fruit and plum pudding.

Tuesday – Baked peas, vegetables, fruit and apple custard.

Wednesday – Vegetable soup, rice and prune pie.

Thursday – Vegetables, boiled bread pudding, cream and fruit.

Friday – Vegetables, fruit, pumpkin or potato pie.

Saturday – Bean soup, vegetables, rice or sweet potato custard.

Sunday – Baked beans, Yankee bread, cream pie and fruit.

The sweet items listed above would have used a small amount of molasses rather than sugar. No butter or lard was used in baked desserts. All dishes were served warm, not hot, without seasonings other than a bit of salt. A recipe for pea soup was given by Asenath Nicholson, founder of the Graham Boarding House on Beekman Street in New York City, and author of Nature’s Own Book [frontispiece at top]. For pea soup, she wrote, “Boil [peas] till beginning to be soft, with a little pearlash [to reduce acid content] – then change the water, and when well cooked, add a little thickening of flour.” She gave two recipes for “coffee,” one made of burnt bread, the other of potatoes.

Nicholson also codified other food rules for Graham boarding houses. Mashed potatoes were out because they did not involve chewing. Stale bread, on the other hand, was desirable because it did require chewing. Pastry was “an abomination.” Warm bread and buckwheat pancakes were “both highly injurious.” Butter was “at best . . . a questionable article.”

The house that Graham and his family lived in is in Northampton MA [pictured here as it looks today] and since 1984 has been a popular restaurant open for breakfast and lunch. Looking over its current menu, I note very few things Graham would permit on his table. It’s likely that only one dish would meet his approval, though it might violate the rule against too many heterogeneous foods in the same meal:

Veggies, Fruits and Nuts Salad – A large salad with tomato, red onion, green peppers, corn, sunflower seeds, candied walnuts, fresh apple slices and dried cranberries… 12.00

I’m pretty sure he would order the red onion removed and certainly would not like the choice of dressings, especially Honey Mustard. Please!

[below: pitchers of coffee at Sylvester’s Restaurant today]

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

February 28, 2016

Deep fried

As I read the morning newspaper a sentence by the head of a local restaurant dynasty caught my attention. “We all have fryolator oil running through our blood veins,” he said.

As I read the morning newspaper a sentence by the head of a local restaurant dynasty caught my attention. “We all have fryolator oil running through our blood veins,” he said.

The speaker was Andrew Yee. His family enterprise includes a newly acquired retro diner, several popular bars & grills, a sushi restaurant, and a venerable Polynesian showplace, the Hu Ke Lau, begun by his father in the mid-1960s.

I was delighted to find the quotation because I was in the midst of researching deep-fried food in American restaurant history. Also because it is rare that topics such as cooking oil come up in reviews and discussions of restaurants. Yet nearly every restaurant kitchen contains a bubbling vat of it.

And always has.

Think about how often you have been enveloped in a miasma of aged cooking oil fumes while passing a restaurant’s outdoor ventilating fan. In 1978 restaurant reviewer Phyllis Richman visited a regional restaurant expo filled with demonstrations of deep frying; she subtitled her Washington Post story “The smell.” Her experience was nothing new. In 1887 neighbors complained about the odor coming from a Cleveland OH “French fried cake baker” using cottonseed oil, which had recently come on the market as a replacement for high-priced lard.

Not that lard fumes would have smelled much better. In 1849 a journalist’s plan to survey the flourishing “eating houses” of lower Manhattan was cut short by the overpowering “smell of fried grease before we got through the first street.” Not surprising when you consider that fried oysters were a top menu attraction and had been for at least a century, probably longer.

The number of deep-fried foods eaten in the 19th century was extensive, including oysters, doughnuts, fish and fish balls, clams, potatoes, all kinds of fritters, “corn dodgers,” brains, chicken, and even parsley.

Deep fat frying in the home in the 1800s was frequent, as far as I can tell. But that changed as kitchens were transformed from rough workrooms to adjunct living areas. For some time now the restaurant industry has benefited from the fact that most home cooks dislike deep frying in their own kitchens and would rather have restaurants prepare their French fries and onion rings.

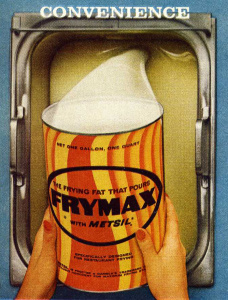

When the Pitco Frialator was invented in 1918 it quickly became standard equipment in restaurant kitchens because it extended the life of cooking oil, reducing costs and improving food quality. Oils were developed that would not break down under high temperatures. Then frying kettles came out with built-in thermostats adjusted to type of food.

When the Pitco Frialator was invented in 1918 it quickly became standard equipment in restaurant kitchens because it extended the life of cooking oil, reducing costs and improving food quality. Oils were developed that would not break down under high temperatures. Then frying kettles came out with built-in thermostats adjusted to type of food.

Profits from the value added to inexpensive foods by deep frying in the 1930s were a boon to struggling restaurants. A 1938 article in The American Restaurant, a trade magazine, estimated that many deep-fried dishes – among them sole, potatoes, oysters, and croquettes – could be priced at four or five times their cost. A restaurant in Duluth MN, The Flame, boasted in an advertisement (to the trade, not the public!) that it had built an “enviable reputation” for fried food through using “tons and tons of Primex.”

Profits from the value added to inexpensive foods by deep frying in the 1930s were a boon to struggling restaurants. A 1938 article in The American Restaurant, a trade magazine, estimated that many deep-fried dishes – among them sole, potatoes, oysters, and croquettes – could be priced at four or five times their cost. A restaurant in Duluth MN, The Flame, boasted in an advertisement (to the trade, not the public!) that it had built an “enviable reputation” for fried food through using “tons and tons of Primex.”

The successful marketing of frozen foods in the 1960s expanded restaurants’ deep-fried selections. Breaded, frozen French-fried shrimp became a top seller. Once only available in Gulf Coast restaurants, by 1960 shrimp appeared on restaurant menus all over the U.S. In 1969 a Gallup Survey rated it America’s favorite deep-fried food in the fish category; in 1973 it ranked #1 among all deep-fried foods.

The successful marketing of frozen foods in the 1960s expanded restaurants’ deep-fried selections. Breaded, frozen French-fried shrimp became a top seller. Once only available in Gulf Coast restaurants, by 1960 shrimp appeared on restaurant menus all over the U.S. In 1969 a Gallup Survey rated it America’s favorite deep-fried food in the fish category; in 1973 it ranked #1 among all deep-fried foods.

Deep-fried chicken ranked third favorite, after shrimp and potatoes, to the disappointment of fans of pan-fried chicken, which was becoming a rarity in restaurants in the 1960s.

Deep-fried chicken ranked third favorite, after shrimp and potatoes, to the disappointment of fans of pan-fried chicken, which was becoming a rarity in restaurants in the 1960s.

Drive-in restaurants relied heavily on deep frying. According to a 1961 Drive-In Magazine, “There was a time not long ago when a deep fat fryer and a neon sign were practically all you needed to put yourself in the drive-in business.” But competition was becoming fierce as fast food chains challenged drive-ins’ popularity with young diners, the customers most attracted to deep-fried food and least afraid of its dietary consequences.

Despite the profitability of deep-fried food, two perils faced restaurants: dark breading and sogginess. Both were due to incorrect frying temperatures, and frying kettles and oil that had not been maintained properly. Customers had a strong preference for fried food that was “golden brown,” but not too dark or hardened into a shell. As an article about “lethal” truck stop fare put it: “You strike a chicken leg and the crust falls away in a curved sheet to disclose a sight best forgotten.” The problem of greasy, limp French fries was cited by Gallup as customers’ second biggest complaint.

But neither darkness, greasiness, nor calories dampened the popularity of deep-fried food. Deep-fried appetizers dominated menus of 1980s chain restaurants designed to appeal to a young adult demographic. At West Coast Froggy’s Cafés (specializing in “food and fun” – and fat) seven out of eight appetizers on a 1980 menu came out of the frialator.

It’s likely we all have oil in our veins.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

February 21, 2016

When coffee was king

For decades coffee was the beverage most restaurant patrons drank with their meals.

For decades coffee was the beverage most restaurant patrons drank with their meals.

But not right away. Coffee houses were popular gathering spots for business men in the Colonial era and in the early Republic but there is no way of knowing how often coffee accompanied meals in those times. Many coffee houses advertised that it was available all day long, but it’s likely it was outsold by alcoholic drinks.

Then coffee began to gain greater importance as the temperance movement developed in the 1830s. A restaurant owner in Providence RI was an early convert to the role of coffee in reforming heavy-drinking Americans. A religious magazine hailed him for his decision to replace liquor with coffee, stating “If a man must, from habit, drink at 11 o’clock, let him drink ‘Hot Coffee’ and patronize Mr. Dinneford.” In those days 11:00 a.m. was the traditional time for a ‘dram.’

So almost from the beginning coffee was associated with a sober, alert, and morally superior approach to life.

From the mid-19th century into the 1890s most inexpensive restaurants charged 5 cents for a cup, though it might cost a couple of cents more or less. Move up a step to a higher grade eating place, such as Mouquin’s, a popular French table d’hôte in New York City, and a cup would cost 10 cents. Luxury restaurants of the 1890s, such as Delmonico’s, were likely to charge 25 cents for coffee, a sum that would buy a whole dinner in a common lunch room.

The importance of coffee to restaurants grew in the 20th century, especially at popular-priced eateries where the price of a cup remained 5 cents. By the early 1920s, the amount of coffee imported into the U.S. had more than tripled since 1880. At “quick lunch” places, individual table & chair combos that looked like school desks were designed with a hole in the top to hold the all-important coffee mug. Already by 1904, some horse-drawn lunch wagons provided cardboard containers for coffee orders to go.

Restaurant proprietors and customers alike agreed that “coffee makes the restaurant” and that you could tell a good restaurant by its coffee. Even when sold at a low price it was profitable, especially at lunch counters where service costs were low. Most diners ordered coffee with their meals in the 1920s, even at the ritzy Waldorf Astoria. No one, it seemed, cared that famous French chef Auguste Escoffier had laid down the rule, “Never serve coffee except at the end of the meal.”

Restaurant proprietors and customers alike agreed that “coffee makes the restaurant” and that you could tell a good restaurant by its coffee. Even when sold at a low price it was profitable, especially at lunch counters where service costs were low. Most diners ordered coffee with their meals in the 1920s, even at the ritzy Waldorf Astoria. No one, it seemed, cared that famous French chef Auguste Escoffier had laid down the rule, “Never serve coffee except at the end of the meal.”

In the 1930s and 1940s, a nickel a cup didn’t seem enough to many restaurateurs who raised their prices to 10 cents. Those that did not had reason to regret it in 1944 when the war caused the federal government to order that restaurants not charge more for coffee that they had in October 1942. For most places this meant 10 cents, but chains such as the Automat, Bickford’s, Thompson’s, B&G Sandwich Shops, and the Waldorf System were stuck with nickel-a-cup until late in 1950.

Prices continued to tick upwards after that. By the mid-1970s 25 cents a cup was standard in the average restaurant. (Even then, there were customers who bristled at paying more than 5 cents!) Often restaurants softened the blow of price increases by offering free refills to those ordering full meals. Still prices rose, and even chains such as Wendy’s raised their price to 30 cents while Friendly’s went up to 35 cents in 1977. Ten years later, one dollar a cup was commonplace.

In the 1970s and 1980s, higher priced coffee beans, along with fast food chain competition, and the rise of soft drinks with meals reduced the popularity of coffee and dealt a blow to coffee shop restaurants. Coffee shops had been the fifth most popular type of eating place according to a 1976 National Restaurant Association survey, but by the mid 1980s they were slipping badly. Philip Langdon, author of a book on chain restaurants titled Orange Roofs and Golden Arches, observed that many coffee shops had restyled themselves as “family restaurants” in an attempt to draw the dinner crowd.

In the 1970s and 1980s, higher priced coffee beans, along with fast food chain competition, and the rise of soft drinks with meals reduced the popularity of coffee and dealt a blow to coffee shop restaurants. Coffee shops had been the fifth most popular type of eating place according to a 1976 National Restaurant Association survey, but by the mid 1980s they were slipping badly. Philip Langdon, author of a book on chain restaurants titled Orange Roofs and Golden Arches, observed that many coffee shops had restyled themselves as “family restaurants” in an attempt to draw the dinner crowd.

Around the same time a series of SCTV comedy sketches made fun of the mythical polka-loving residents of Leutonia and their fondness for “cabbage rolls and coffee,” marking a new attitude to coffee with lunch or dinner that branded it as the choice of unhip elderly diners.

Coffee retains its popularity as a stand-alone beverage today, but less as an accompaniment to meals. Gone are the days when Maxwell House coffee and Cory coffeemakers reigned – when 90% of restaurant customers ordered coffee with their meals (1935) – and when the trio “Cleanliness, Comfort, Coffee” were enough to assure a restaurant of success (1955).

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

February 6, 2016

A fantasy drive-in

I am fascinated by restaurants that are bizarrely at odds with their location, climate, and cultural environment. Such as Polynesian restaurants in Arizona.

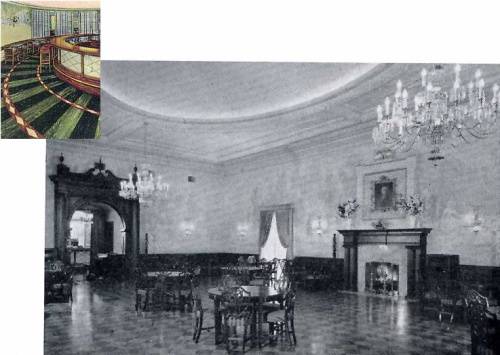

Drive-ins make sense in car-obsessed Southern California, but a grandiose drive-in such as Carl’s “Colonial” with an Old South theme in Depression-era Los Angeles? With architecture inspired by Southern plantations and white female servers costumed as Southern belles and top-hatted coachmen? With an ornate mahogany doorway leading from the staid dining room into a streamlined moderne barroom? [see below] And a thoroughly modern, thermostatically controlled stainless steel kitchen turning out spaghetti and turkey with New England dressing?

All societies offer some form of escapism, traditionally wild festivals where revelers are released from everyday roles and inhibitions. But restaurants such as Carl’s offered a different kind of escapism that shored up inhibitions and insured that roles were strictly adhered to. Far from allowing revelry or role reversal, gracious Southern dining took place in a forbidding room decorated with murals of slaves picking cotton and a portrait of George Washington looming from above the mantle. [shown above; the murals are barely visible] Only white girls were allowed to dress as Southern belles; ice water and rolls were dispensed by dark-skinned “mammies.”

Yet in another way Carl’s was totally in sync with its environment. A Los Angeles Times story in 1940 noted, “Los Angeles restaurants serving American food often reflect the architecture of other lands.” Undoubtedly part of the explanation for the scenographic quality of Carl’s – and many other unusual theme restaurants in Southern California – was that they played to tourists’ fantasies. And why not, since a hefty 25% of restaurant revenue was estimated to come from tourists?

The “Colonial” Carl’s, on the corner of Crenshaw and Vernon, was built by the Los Angeles Investment Company and leased to its operators, Carl B. Anders and A. V. Spencer. The area was under development with about 13 new stores on Crenshaw skirting the residential subdivision of Viewpark. When Carl’s opened in 1938 there were close to 1,000 homes in Viewpark with more underway following the company’s acquisition of acreage that had housed the Olympic Village in 1932. Under restrictive covenants, houses could be sold only to white buyers.

The “Colonial” Carl’s, on the corner of Crenshaw and Vernon, was built by the Los Angeles Investment Company and leased to its operators, Carl B. Anders and A. V. Spencer. The area was under development with about 13 new stores on Crenshaw skirting the residential subdivision of Viewpark. When Carl’s opened in 1938 there were close to 1,000 homes in Viewpark with more underway following the company’s acquisition of acreage that had housed the Olympic Village in 1932. Under restrictive covenants, houses could be sold only to white buyers.

Despite serving up to 4,000 customers a day, many of them groups such as women’s and businessmen’s clubs, Carl’s Colonial in Viewpark went out of business in 1953. After a brief run as Martha’s Restaurant, it was torched in 1954, destroying the building that had cost the fabulous sum of $115,000 when it was constructed.

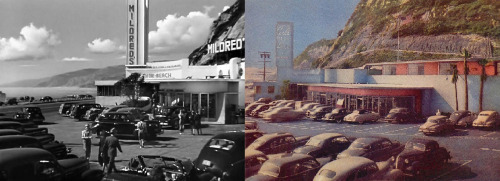

Carl’s in Viewpark was one of five in the Carl’s chain (not to be confused with Carl’s, Jr.). The first was opened in 1931 on Figueroa and Flower as a simple hamburger stand built to serve people attending the 1932 Olympic Games. It was so successful it was enlarged three times in four years, serving up to 5,000 people daily in 1937. The chain became known for its multi-purpose restaurants that included a drive-in component as well as full-service dining rooms, banquet facilities, outdoor dining patios, and cocktail lounges. Other Carl’s included one on the Plaza in Palm Springs, one on the Pacific Coast Highway that was featured in the movie Mildred Pierce, and one on East Olympic Blvd. at Soto Street.

According to John T. Edge, Southern theme restaurants have recently resurfaced in Los Angeles.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

January 19, 2016

Farm to table

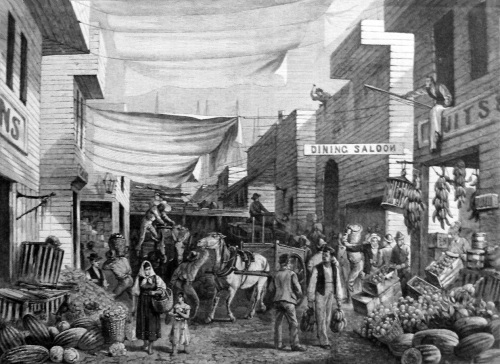

We might imagine that in the past the food served in restaurants was grown or raised fairly close to where it was consumed, perhaps that it came from farm to table without delay. Undoubtedly this was true in much of the 19th century when sellers brought their produce as well as live animals to city markets. [NYC’s Washington Market above, ca. 1850s]

Also, some 19th-century restaurants obtained fresh foods directly from farmers and hunters. A Detroit proprietor solicited suppliers with an advertisement in 1861 that said, “Farmers, hunters and others with game of any kind will please call upon William Carson, Carson’s Dining Saloon.”

Yet people living in cities still longed for food grown and raised in front of their eyes. They loved vacationing at country resorts that grew their own food. In 1858, for example, a typical notice appeared in a Baltimore paper about The Seven Fountains in the Blue Ridge Mountains where “The Table is abundantly supplied with Vegetables, Butter and Milk fresh from our own Farm and Dairy.”

Dairy products were perhaps the least satisfactory foods for city dwellers who did not keep their own cows, mainly because of the threat of sick cows kept penned up in and near cities and fed with swill. Milk that arrived from afar also presented dangers since there was always a good chance it might not be fresh.

Dissatisfaction with the milk supply opened up opportunities for dairies near cities. In the 1870s some began to operate urban “dairy lunch” rooms which became quite popular in the following decades. Washington, D.C., was full of them. One near the Treasury building adopted a decorating scheme with hanging baskets of plants, cages of canaries, and papier mâché cow heads. In Boston, the new Oak Grove Farm café seemed almost too good to be true. A reporter admitted he thought at first it was “a con.” But the café was indeed supplied by an 800-acre farm with 150 cows, as well as hothouses where lettuce and tomatoes were grown.

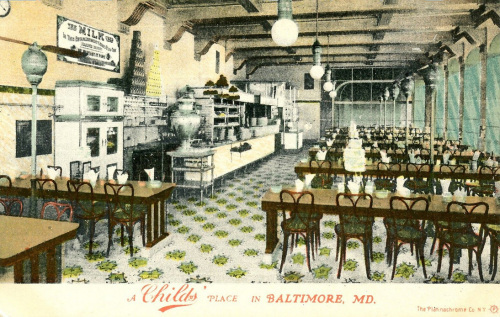

Childs, the first sizable chain of restaurants in the US, built its reputation on its dairy farms in New Jersey. Started by six farm-raised brothers in 1889, three ran the lunch rooms while the other three managed the chain’s dairies and truck farms.

In the late 19th-century some Americans balked at the modern food system altogether. Food traveled great distances by rail, much of it ending up parked for indefinite periods in cold storage warehouses. In them it suffered from fluctuating temperatures that damaged taste and texture, as well as sometimes causing the growth of bacteria. A prominent NYC physician declared that when he ordered game in a restaurant, “I make the waiter interview the chef to make sure that no cold storage game will be sent to fill my order.”

As the century turned, people were paying more attention to where their food came from. Due to the growth of the meat packing industry, factory production of butter and cheese, improved transportation, and cold storage facilities, traditional farm industries had largely disappeared. Despite seemingly positive pronouncements such as, “It is to the modern methods for the preservation of foodstuffs that we owe in great measure the lengthy bills of fare provided by our hotels and restaurants,” many people felt food had lost something. Some had come to fear it.

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 addressed impurities in food, but critics wanted more. A few years later efforts were mobilized to subject cold storage warehouses to periodic inspections, to label all food with the date it arrived, and to set limits on how long food could be stored. Foreshadowing the “Truth in Menu” laws of the 1970s, which wanted to bar restaurants from claiming that frozen food was fresh, some laws demanded that restaurants inform patrons if food had come from cold storage.

In this context restaurants supplied by their own farms proudly proclaimed that fact. A restaurant operator in Harrisburg PA who used home-grown food hit upon a novel slogan: “Farm to face.” In Denver a café advertised that its farm food cost no more than food that had been stored. In NYC the Craftsman restaurant promised that patrons would enjoy “all the wholesome products people crave in a city” delivered daily from their farm.

In this context restaurants supplied by their own farms proudly proclaimed that fact. A restaurant operator in Harrisburg PA who used home-grown food hit upon a novel slogan: “Farm to face.” In Denver a café advertised that its farm food cost no more than food that had been stored. In NYC the Craftsman restaurant promised that patrons would enjoy “all the wholesome products people crave in a city” delivered daily from their farm.

During World War I, eating places linked to farms served all social classes — from the quick lunch in Flint MI that promised lower prices by “cutting out the middle man” to fashionably smart tea rooms such as “At the Sign of the Golden Bull” in Boston. Its tea room, grill room, and affiliated Deerfoot Farm store were designed by Tiffany Studios, and outfitted with Grueby tiles, Flemish oak tables, and leather benches.

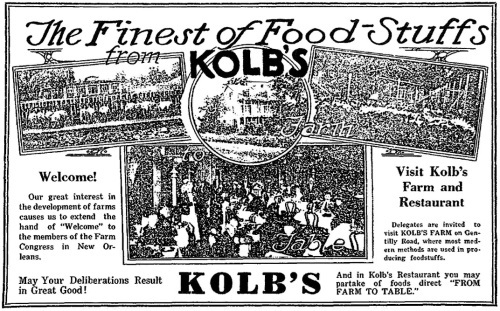

Starting around 1915 and lasting into the early 1920s, a US Post Office-backed “Farm to Table” movement encouraged consumers to have farmers ship them fresh food via parcel post. Its goals were to lower food costs while aiding farmers. In November of 1919, the B. F. Goodrich company supported a Farm to Table week in which consumers were to drive to rural areas to buy provisions from farmers. At least one restaurant which ran a farm, Kolb’s in New Orleans, adopted the slogan. In the late 1920s the Miami FL chamber of commerce encouraged restaurants to buy local, arguing that it was not only healthy to serve more fruits and vegetables but good for farmers and the Dade County economy.

Starting around 1915 and lasting into the early 1920s, a US Post Office-backed “Farm to Table” movement encouraged consumers to have farmers ship them fresh food via parcel post. Its goals were to lower food costs while aiding farmers. In November of 1919, the B. F. Goodrich company supported a Farm to Table week in which consumers were to drive to rural areas to buy provisions from farmers. At least one restaurant which ran a farm, Kolb’s in New Orleans, adopted the slogan. In the late 1920s the Miami FL chamber of commerce encouraged restaurants to buy local, arguing that it was not only healthy to serve more fruits and vegetables but good for farmers and the Dade County economy.

Although there continued to be some restaurants that grew their own food throughout the US, the movement petered out in the Depression. A 1932 correspondence course for those interested in opening a rural inn warned that growing one’s own food or buying it in the country did not pay. Instead, it advised, it was best to buy groceries, meats, and dairy products from city wholesale dealers. Greater status was attached to having foods available year round. According to Susanne Freidberg’s book Fresh: A Perishable History, in the 1930s the Schrafft’s chain listed how many miles the food they used traveled. Freidberg writes that “the makings of a vegetable salad together racked up 22,250 miles,” demonstrating “technology’s conquest of borders, distance, and seasons.”

After the Second World War, industrial food production grew rapidly as did the restaurant industry which turned increasingly to convenience food products made specifically for commercial and institutional meal service. By the 1960s frozen foods included pre-prepared heat-and-serve entrees.

In the 1970s convenience foods became controversial as their use spread. The decade saw the advance of farm-themed restaurants using convenience foods, on the one hand, and, on the other, a growing number of restaurants and consumers rejecting factory food. In 1973 architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable expressed displeasure with “the unfulfilled promise [of] the American way of life,” one symptom of which was “the oversize restaurant menu suggesting farm-fresh succulence and delivering precooked food .” Meanwhile, even as farm-theme restaurants hung farm implements on their walls of recycled barn siding, Alice Waters at Chez Panisse and other California restaurateurs were buying produce from local farmers, leading a movement that would burgeon in the 1980s and continue into the 21st century.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

January 10, 2016

Between courses: masticating with Horace

Having made a lot of money in the importing business early in life, Horace P. Fletcher [1849-1919] retired and became a popular health guru known as the “Great Masticator.” He let people know how they could eat less and reduce their food budget, have better digestion, and get more enjoyment out of eating. His ideas attracted quite a bit of attention in the early 20th century.

Not that everyone agreed that chewing food to pulp – at least 30 chews according to the scientific system of Fletcherism — was how they wanted to experience the joys of degustation. Nor would everyone want to witness someone Fletcherizing.

Take oysters. Who would want to go to a restaurant with someone who chewed oysters until all that remained was pulp? And then see him remove the residue from his mouth saying, “The juice is all out of this. The stomach does not need it.” This uncomfortable moment might well take place in an elegant dining room such as at New York’s Waldorf Astoria.

Dairy lunch rooms — with their simple a la carte menus of cereals, milk, potatoes, and other starches – were his favorite places to eat. But, he often stayed at deluxe hotels and ate in their dining rooms. Throwing aside their sumptuous menus, he had no qualms at all about ordering highly irregular – not to mention cheap — meals, often omitting meat or anything resembling a main dish.

Dairy lunch rooms — with their simple a la carte menus of cereals, milk, potatoes, and other starches – were his favorite places to eat. But, he often stayed at deluxe hotels and ate in their dining rooms. Throwing aside their sumptuous menus, he had no qualms at all about ordering highly irregular – not to mention cheap — meals, often omitting meat or anything resembling a main dish.

In 1904, in a hotel dining room, he ordered hash brown potatoes, which he ate with a spoon, and half a French roll. He used the other half for dessert, after pouring over it a mixture of cream and sugar he whipped together. His waiters undoubtedly got small tips but at least he gave them something to talk about for months afterward.

A lunch room repast might be something such as a leaf of lettuce with only oil for dressing, two pancakes, and a cup of custard. He drank coffee slowly, taking a sip and holding it in his mouth for 30 seconds.

In 1912 he ate nothing but potatoes for 58 days. Testing by scientists showed that his strength and endurance did not suffer as a result of his diet.

Despite his extremism – and his fondness for potatoes and candy – his stress on eating less meat, eating more slowly, and not swallowing barely chewed food may have served his followers well. He was a hero to many people, particularly dentists who were overjoyed with his appreciation of teeth.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

January 3, 2016

Restaurant-ing with Mildred Pierce

Many Americans are familiar with the story of the fictional Mildred Pierce, the mid-century wife and mother who kicks out her unemployed, philandering husband and becomes the family’s breadwinner so she can support her two daughters, especially her musically talented older daughter Veda.

Mildred Pierce was the main character in James M. Cain’s novel of the same name, the star of a melodramatic 1945 black & white film-noir with Joan Crawford, and the protagonist in a color HBO miniseries with Kate Winslet.

Lacking experience other than housewifery, Mildred turns to restaurants for work. Starting as a waitress, she builds a home-based business as purveyor of pies to restaurants, then opens a restaurant of her own, building it into a small chain in greater Los Angeles.

Although the three renditions of the story differ, they all feature Mildred’s restaurant career. Why did Cain choose this line of work for Mildred? I suspect he wanted something that readers would believe a woman could succeed in. Though I have no direct evidence, I feel sure he based Mildred’s career on that of the much-publicized Alice Foote MacDougall of 1920s fame whose success story was told repeatedly in magazines and syndicated newspaper columns. In the 1927 column “Girls Who Did,” MacDougall, then pushing 60, was headlined as “A Girl Who Never Expected to Enter Business and Who Has Become a Dealer in Wholesale Roasted Coffee and Owner of Four Restaurants.”

But – oh dear – MacDougall’s empire went into receivership in the early Depression, shortly after Mildred Pierce launched her restaurant chain. Of course most movies demand suspension of disbelief on the part of viewers, but let’s just admit that 1931 was not a favorable time to go into business. The 1935 National Handbook of Restaurant Data dismally reported that “75% of the women who open restaurants fail within the year.” Mainly, it said, due to lack of capital and knowledge of business management.

Cain, who stuffs his novel with copious details about running restaurants, must have been aware of this problem because he had Mildred, er, entertain her husband’s former business partner Wally to insure a favorable start-up. In the book she builds up to a total of three restaurants. The first, located in a house and specializing in chicken and waffles, actually conforms to the path many women of the 1920s and 1930s took starting small restaurants and tea rooms that served home-like dishes in domestic settings. Her second, a luncheonette in Beverly Hills, is somewhat believable despite being in a high rent area. Her third, on the other hand, a swanky beachside resort, is a reach.

Cain, who stuffs his novel with copious details about running restaurants, must have been aware of this problem because he had Mildred, er, entertain her husband’s former business partner Wally to insure a favorable start-up. In the book she builds up to a total of three restaurants. The first, located in a house and specializing in chicken and waffles, actually conforms to the path many women of the 1920s and 1930s took starting small restaurants and tea rooms that served home-like dishes in domestic settings. Her second, a luncheonette in Beverly Hills, is somewhat believable despite being in a high rent area. Her third, on the other hand, a swanky beachside resort, is a reach.

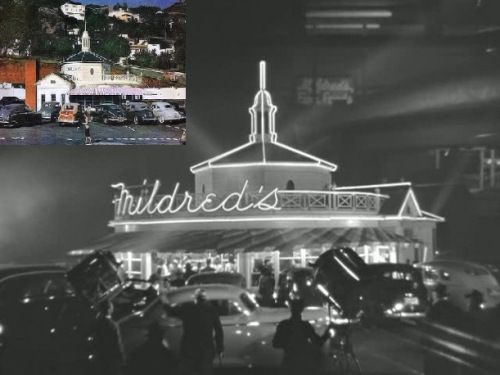

Advancing farther on the unlikelyhood scale, the 1945 movie threw caution aside and had Mildred with five restaurants in only four years. Even the fantabulous Alice took 10 years to get to four! What’s more, all but one of Mildred’s had drive-in curb service, even though women rarely owned drive-ins. Plus, many drive-ins closed during the war because of gasoline rationing that limited driving.

Of the five restaurants depicted in the 1945 film, three are identifiable as actual restaurant locations, while the identity of the other two is unclear.

#1 – the new Dolores drive-in on Sunset Blvd. & Horn (inset top left; movie still in b&w)

#1 – the new Dolores drive-in on Sunset Blvd. & Horn (inset top left; movie still in b&w) #2 – supposed to be Beverly Hills, but location unknown and possibly not an actual restaurant at all (movie still)

#2 – supposed to be Beverly Hills, but location unknown and possibly not an actual restaurant at all (movie still)

3 – unidentified but appears to be a real drive-in (movie still)

3 – unidentified but appears to be a real drive-in (movie still)

#4 – exterior shot filmed at Carl’s Sea Air on the Pacific Coast Highway (movie still on left; Carl’s postcard on right)

#4 – exterior shot filmed at Carl’s Sea Air on the Pacific Coast Highway (movie still on left; Carl’s postcard on right)

#5 – Carpenter’s restaurant on Glendale & Colorado shown fleetingly (not a movie still)

#5 – Carpenter’s restaurant on Glendale & Colorado shown fleetingly (not a movie still)

The slow-moving HBO series follows Cain’s book more closely than the 1945 movie. (As in the book, there is no murder.) There are only three restaurants, all movie creations: 1) the model house from the Pierce Homes development once owned by Mildred’s ex-husband; 2) the Beverly Hills luncheonette; and, 3) a seaside estate which doesn’t look a bit like it’s in California.

In the book and at several points in the 1945 movie Mildred, who we are told comes from the lower-middle class, runs up against the upper class, always getting bruised in the encounters. As a restaurant historian, one of the most interesting lines to me occurs when she meets the snobby mother of her daughter’s boyfriend. Mildred recognizes her but forgets that she had once interviewed to be her housekeeper and was humiliated by the woman. She tries to place her, asking if she has ever been to her restaurant and the woman replies haughtily, “But I don’t go to restaurants, Mrs. Pierce.” It would have been more believable in the East, around 1900, but still an interesting comment on the unexalted status of restaurant-ing.

Cain, who was also a gourmet, an amateur cook, and a magazine food writer on topics such as “Midnight Spaghetti,” “Crepes Suzette,” and “Carving Game Duck,” befriended Alexander Perino when he was headwaiter at The Town House and suggested Perino open his own restaurant which he famously did in 1932. Restaurants also figured in Cain’s books The Postman Always Rings Twice and Galatea, both of which involve the betrayal and murder of husbands.

In Cain’s Mildred Pierce, Mildred ends up broke, restaurantless, alienated from Veda, and living with her ex-husband, both of them ready to pursue a life of heavy drinking.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016