Jan Whitaker's Blog, page 25

January 8, 2017

Restaurant wear

Although affluent women of the upper classes patronized restaurants in the 19th century, they usually did not do so unless they had a respectable male escort, preferably a brother, father, or husband. Respectable women were not supposed to appear too much in public view, and only in select eating places such as the dining rooms of leading hotels.

But as the century ended the situation began to change. Dining and entertaining in restaurants became fashionable and women appeared in public during the daytime without an escort, whether at lunch or afternoon tea. And they wanted to be seen.

The idea that there was a certain type of clothing right for these occasions began to take hold. Around 1900 the terms restaurant wear, restaurant gown, and restaurant frock proliferated in newspaper stories that reported on what stylish women were seen wearing in Paris restaurants.

It was a sign that restaurant-going had truly arrived. It no longer inevitably carried the stigma of vice and moral peril. Even though the majority of American women, especially those living in small towns and rural areas, might never see the inside of a swank tea room or café, those reading the society pages could imagine all eyes on them as they entered an elegant restaurant dressed in the latest style.

In 1903 women of Tacoma WA who followed their paper’s “Fashion Hints from the Shops” learned that black silk costumes for restaurant going were “quite the thing.” The prettiest gowns had skirts with flouncy semi-trains and a pleated top with velvet bows in front worn with a long fringed silk scarf.

Top tea rooms and restaurants became stages for virtual fashion shows. Clever dressmakers were said to “haunt” tea rooms to get ideas of the latest styles. In New York, Delmonico’s and Sherry’s were prime spots to see the pleats, flounces, laces, scallops, eyelets, and ribbons of the much be-decked outfits of 1905. The wisdom of the day had it that women went to such places not for the food, but to see what other women were wearing.

[image error]Those traveling in the open autos of 1909 wore heavy, unattractive coats to protect them from road dirt and grime. But the bright side, pointed out the Philadelphia Inquirer, was that the coats were loose enough around the shoulders that “really elaborate costumes may be worn beneath them without harm.” The example, hard to appreciate in the black and white drawing here, was a coral pink restaurant frock with braided trim and crocheted buttons topped with a hat sporting what were mysteriously described as “vivid coral wings.”

Enormous attention was paid to women’s necklines with the new interest in restaurant wear. Time and again readers were warned not to confuse restaurant wear with formal wear. The rules were firm. Formal wear meant revealingly plunging necklines, bare arms, and no hat. Restaurant wear, by contrast, meant a frontal coverup, with a moderate neckline or even a high choker-style collar. The dress must have sleeves and the costume was to be topped off with a hat.

But rules are often broken. According to Julian Street’s 1910 magazine article titled “Lobster Palace Society,” gauche gold-trimmed Babylonian restaurants such as the Café de l’Opera in New York’s Times Square made every effort to seat women with low necklines prominently on the ground floor.

[image error]The 1920s featured a new silhouette, as shown in this advertisement for glamorous gowns in 1922 as sold in Philadelphia’s Frank & Seder department store. Hats were getting smaller in the 1920s and 1930s, sometimes replaced with hair ornaments.

[image error]Far from the Depression dampening the wish to get dressed up and go out on the town, the repeal of Prohibition in 1933 introduced a new fashion category, the cocktail dress. Tailored looks prevailed, and in 1938 a fashion columnist chided women who instead chose “luscious, romantic, billowy” frocks to wear to restaurants and nightclubs, sternly telling them that “such fragile, pale bits of formality are not worn!”

[image error]The trend toward simplification and informality continued in the 1940s with a wartime preference for plain, dark dresses as shown here. By the mid-1950s many women reportedly tried to pass off sundresses as appropriate for the cocktail hour (verdict: “Nothing could be more incorrect for after-five-wear.”) while teens couldn’t see why they shouldn’t wear jeans to a restaurant. Not nearly special enough, reasoned the columnist Dorothy Dix. Advice thrown aside, the casual trend continued.

Since the 1970s “restaurant wear” has come to refer mainly to uniforms for restaurant staff.

© Jan Whitaker, 2017

January 1, 2017

2016, a recap

It has been a great blog year. After 8½ years and 381 posts, it’s nice to report that my blog is still growing. I’ve accepted that it won’t ever be a blockbuster, but I am cheered that I get more readers all the time. 2016 also stands out for including my best day ever as measured in page views, doubling the total from my last best day. And 34 posts, many of them old ones, got more than 1,000 views this year.

I hear from a lot of readers via e-mail, many of whom have information about a restaurant I’ve written about or ideas for future topics. Some of them are doing their own research. Recently I heard from an author in France asking about restaurants that provided customers with telephones at their tables. I’m always happy to share my sources with them, though of course I can’t perform individual research.

Warm thank-yous to all my readers, subscribers, commenters, linkers, and likers. Happily, only one post I’ve written has attracted trolls. I am perfectly willing to approve comments that disagree with my slant on things or correct mistakes, but I don’t accept hostile comments that attack me or another reader. Nonetheless, thanks to trolls for boosting my stats!

It’s heartening to see that many of my old posts still have power to attract readers, such as the ones on parsley, uncomfortable seating, or the buying power of a nickel. Posts on once-beloved restaurants such as Wolfies in Miami and Miss Hulling’s in St. Louis continue to draw thousands of readers each year.

What’s coming up? More books are being written on the history of restaurants, so expect to see reviews of Ten Restaurants That Changed America (Paul Freedman), Restaurant Republic (Kelly Erby), and Dining Out in Boston (James C. O’Connell). And my list of ideas for future posts never shrinks — in fact it’s longer than ever. There are quite a few in the pipeline, such as restaurant fashions for women diners, The Bakery in Chicago, and the 19th century’s cheapest-of–cheap eateries.

Wishing everyone happy restaurant-ing and a good new year.

December 18, 2016

Holiday banquets for the newsies

In the 19th and early 20th century, newspapers were sold on city streets by young boys, and a few girls. Some of the children – who could be as young as 5 years old — were homeless while others came from poverty-stricken families. Their meals could be few and far between and they were always hungry.

But on Christmas Day, or a day close to it, they ate well thanks to the annual custom of newspapers, philanthropists, mayors, and others who organized feasts for them. Some of the dinners were held in orphan homes and public buildings, but many took place in restaurants.

[image error]Turkey was the typical featured food of the newsboys’ dinners. In 1875 the Telegram gave a dinner at Henri Mouquin’s restaurant on Ann Street in New York for over 1,000 boys and a handful of girls. The menu was roast turkey, mashed potatoes, rolls and butter, finished with cake, pie, coffee, and oranges. Nearly identical meals were given across the country for decades to follow, some accompanied by cranberry sauce and side dishes such as corn, peas, celery, and pickles. After dinner the children sometimes received a box of candy to take with them.

The newsboys of Kansas City MO, guests of the mayor, hailed turkey in a little ditty they shouted in a procession from City Hall to Staley & Dunlap’s restaurant on Main street in 1895.

Who are we? Who are we?

We are the newsboys of K. C.

We are the stuff; that’s no bluff;

We eat turkey and never get enough.

A dinner held in a Dallas restaurant in 1899 had a menu that departed radically from the customary dishes [see below]. There was no turkey or pie. And not only was the menu organized into the old-fashioned categories of Fish, Boiled, Roasts, and Entrees, they were not presented in the traditional order of appearance. It also contained quite a variety of assorted dishes, some of them unusual. “Boiled Rallet of Beef” might have referred to Rilettes of beef, which was beef cooked to mush and served on toast.

[image error]Boisterous behavior during dinner was expected. The boys cheered loudly for their hosts and entertainers, producing a noise level often described as deafening. Food fights were typical. At the Chequamegon restaurant in Butte MT in 1902, a report said the children “yell, whistle, throw biscuits at each other and occasionally land on each other’s jawbones with a dislocated leg of the bird.” Dinner sponsors often egged on high spirits by giving the newsies tin horns and firecrackers.

As much as the newsboys and newsgirls enjoyed the holiday dinners, the charitable events had their detractors. Reformer Florence Kelley criticized the dinners as well as the newsboys’ lodging houses found in some cities because they encouraged children to work and live independent of their families. She criticized New York City in particular for making newsboys into heroes. Rather than being seen purely as victims, as would be the case today, the boys were often regarded as spunky survivors with potential to succeed in life despite their rough style of living and lack of schooling.

[image error] In the early 20th century, states tried to limit child labor. Girls under 14 were barred from jobs involving selling. Boys under 10 could not sell papers and those aged 10 to 14 had to obtain written parental consent before a badge was issued to permit them to sell papers in the streets. Still, the dinners continued through the 1920s and 1930s. In the 1930s Bishop Cafeterias in seven cities held annual newsboys’ dinners to honor the chain’s late founder Carl Stoddard who had been a newsboy as a child.

Newsboys’ dinners could sometimes be found into the 1960s, but the children were absent, having been replaced with adult news vendors.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

December 11, 2016

Multitasking eateries

For centuries people have grabbed something to eat wherever they happened to be. Maybe they bought a baked potato from a roving street peddler, got tamales from a lunch cart, or stopped at a stand for a hot dog.

The places they got their food were usually not full-scale restaurants with waiters, complete meals, and sit-down service. The food and surroundings were often rudimentary. In the 20th century, and now, many catch-as-catch-can eateries were combined with other types of businesses.

Gas stations are a prime example. But only once have I come across a lunchcounter installed inside the garage itself as shown here. Along with coffee and grub, it looks like customers could just grab a fanbelt off the wall at this homespun Arkansas café.

As was true of gas stations, eateries were often provided to serve people who stopped to take care of other chores, whether filling up their gas tank – or getting a haircut. Combining a quick lunch stand with a barber shop was outlawed in Duluth MN in the 1920s, perhaps because customers were finding hairs in their soup?

But I have to admit it was handy that the W-Bar-W Steak Ranch in Kennesaw GA was combined with a pawn shop in the 1960s. If hungry diners’ appetites exceeded their funds, they could pawn their watches.

And certainly it was convenient to have your shoes shined while you ate.

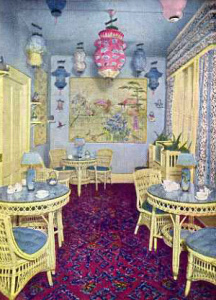

How about some tea or bouillon while you wait for the dentist to work on your teeth? Unlike most other providers of refreshments, Dr. Arthur Cobb of Buffalo NY did not try to make money from his color-coordinated Japanese Tea Room.

How about some tea or bouillon while you wait for the dentist to work on your teeth? Unlike most other providers of refreshments, Dr. Arthur Cobb of Buffalo NY did not try to make money from his color-coordinated Japanese Tea Room.

Of course it has always been common to combine places of amusement with opportunities to eat a bite. In the 1850s men looking for an evening of entertainment might go the Washington Hall Restaurant and Pistol Gallery. After consuming “Beverages and Edibles” guests could enjoy rifle and pistol practice upstairs. Given the “beverages,” it sounds like a recipe for disaster to me.

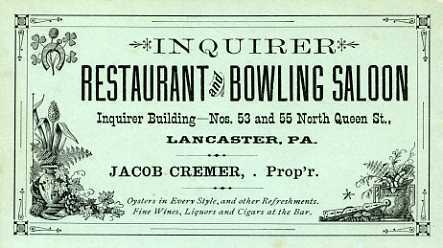

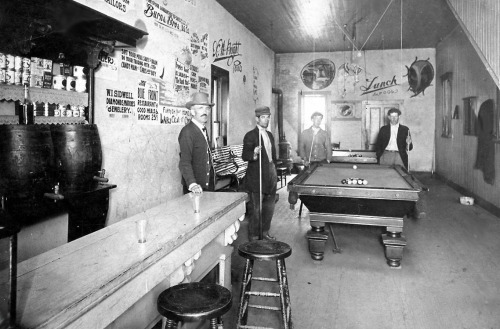

Bowling, pinball, and billiards were also frequently accompanied by eats as the following images show.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

November 30, 2016

Famous in its day: the Blue Parrot Tea Room

“Hoity toity” was how a resident of Gettysburg PA in the 1980s remembered The Blue Parrot Tea Room in its heyday.

“Hoity toity” was how a resident of Gettysburg PA in the 1980s remembered The Blue Parrot Tea Room in its heyday.

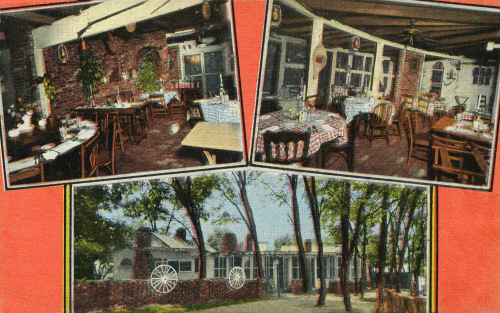

The tea room opened in 1920 on the Lincoln Highway (aka Chambersburg street) through Gettysburg [pictured above, before 1928]. Known initially as the Blue Parrot Tea Garden (rendered on its large lighted sign in pseudo-“Oriental” lettering), it was a soda fountain, candy store, and lunch spot at first. It quickly earned a reputation as an eating place for “discriminating” diners, according to its advertisement in the 1922 Automobile Blue Book [shown below]. Later advertising described the restaurant as modern, sanitary, and perfect for people who ran an “efficient table” at home.

Its creator was Charles T. Ziegler, who spent years on the road as a salesman for a Chicago firm, returning to his hometown to open a gift shop in 1916 with the then-trendy name of Gifts Unusual. His shop featured imported articles such as Japanese household items and kimonos. In 1917 he bought the building his shop was in, turning it into a tea room a few years later.

The tea room’s artistic decor, elements of which had reportedly come from England and Belgium, was of great interest to Gettysburgers. The sign on the front of the building was illuminated with 275 small lights (this was before neon). Thirty feet in length and topped with a blue parrot, the Gettysburg Times declared it “one of the most pretentious between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.”

In 1927 a visitor noted fine aspects of the Blue Parrot that he observed, many vouched for by their brand names, such as Shenango China and Community Silver. He was pleased to note that the kitchen was shiny and spotless and even the potato peeler was “cleaned to perfection.” He was also gratified by the back yard area where “every fowl is killed, cleaned and dressed by the kitchen staff.”

The Blue Parrot remained the place to go for decades. Local colleges held dinners there, as did fraternal organizations and women’s clubs. Guests included bishops, Washington dignitaries, Harrisburg business men, and traveling celebrities. A high point came in 1926 when Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and Gloria Swanson and her husband, the Marquis de la Falause, stopped for dinner on a chauffeured road trip following the New York funeral of Rudolph Valentino.

The Blue Parrot remained the place to go for decades. Local colleges held dinners there, as did fraternal organizations and women’s clubs. Guests included bishops, Washington dignitaries, Harrisburg business men, and traveling celebrities. A high point came in 1926 when Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and Gloria Swanson and her husband, the Marquis de la Falause, stopped for dinner on a chauffeured road trip following the New York funeral of Rudolph Valentino.

The Blue Parrot could be counted on to furnish special holiday meals for Thanksgiving, New Year’s Day, and Easter. In 1924 it published the following menu for Thanksgiving Dinner, served from 11 am to 9 pm.

Grape Fruit

Oyster Cocktail

Bisque of Tomato

Celery Olives

Salted Nuts

Roast Vermont Turkey English Filling

Giblet Gravy Cranberry Jelly

Orange Sherbert [sic]

Mashed Potatoes Green Spinach au Egg

Waldorf Salad

Hot Mince Pie Lemon Meringue

Pineapple Parfait Chocolate Ice Cream

Mixed Fruit Ice Cream

Mints

Café Noir

Dinners at the Blue Parrot in the 1920s ran from $1.25 to $1.50, while lunches were often 75 cents. The tea room advertised its prices as moderate, yet probably they would have been out of reach for many of Gettysburg’s working class residents. In the 1930s Depression the Blue Parrot, like so many other restaurants, was forced to lower its prices considerably. In the mid-1930s it offered lunch platters at 30 cents and New Year’s and Thanksgiving dinners for as little as 50 cents.

No doubt the end of Prohibition was a life saver for the Blue Parrot. As soon as beer became legal in 1933, Ziegler opened a Blue Parrot Tap Room and Grill on the second floor, with extended hours, Pabst Blue Ribbon on tap, and 10-cent crab cakes and sandwiches. He was at the head of the line for a full liquor license when they became available a few months later. The bar and grill had a western slant with rustic log cabin decor, knotty pine paneling, and a wagon wheel light fixture, all likely designed to appeal to a wide range of male customers.

In 1944 Ziegler sold the business to Gettysburg’s fire chief, James Aumen, who ran it for the next ten years, after which it had a succession of owners. Even in recent times, the original name has continued as the Blue Parrot Bistro, and now the Parrot.

In 1944 Ziegler sold the business to Gettysburg’s fire chief, James Aumen, who ran it for the next ten years, after which it had a succession of owners. Even in recent times, the original name has continued as the Blue Parrot Bistro, and now the Parrot.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

November 19, 2016

A hair in the soup

Until the 1920s the catchphrase “hair in the soup” referred to something that was a trivial problem. In other words, just remove it and keep on eating.

Until the 1920s the catchphrase “hair in the soup” referred to something that was a trivial problem. In other words, just remove it and keep on eating.

And then women started wearing their hair short.

Manufacturers of hairpins, barrettes, and hairnets felt desperate as sales of their products fell off drastically. But Edward Bernays, a pioneer in the new field of public relations, had an idea of how to revive business. He found safety experts who warned of the dangers of women working without hairnets and getting their hair caught in machinery. Also, under his guidance health experts emerged who recommended hairnets for waitresses to avoid contaminating food.

State legislatures and municipalities began to pass laws and ordinances requiring servers, mainly women, to wear hairnets or headbands [shown above, 1920s]. In Richmond VA the health commissioner advocated a hairnet requirement, saying he had witnessed waitresses with bobbed hair shake their heads to get hair out of their eyes, risking loose hair falling in food.

In the decades that followed consumers became hairnet watchdogs, sending off letters to newspapers asking why waitresses weren’t wearing hairnets or restraining hairbands. Newspapers took up the role of consumer protectors, asking health departments to investigate. Health departments around the country responded to complaints by making special visits to targeted restaurants.

In the decades that followed consumers became hairnet watchdogs, sending off letters to newspapers asking why waitresses weren’t wearing hairnets or restraining hairbands. Newspapers took up the role of consumer protectors, asking health departments to investigate. Health departments around the country responded to complaints by making special visits to targeted restaurants.

Did the agitation about hair in restaurant food result in more sanitary conditions? Probably not, and not even when it resulted in waitresses covering or restraining their hair.

The reason was that special visits to restaurants interrupted the regular health inspection work by strapped health departments, stealing time from monitoring more serious issues.

In 1967 a Greensboro NC paper’s “Hot Line” surveyed 19 restaurants and found widespread noncompliance with state regulations calling for head coverings. In this case, however, the county health director said he felt head coverings were a minor health concern compared to issues such as improper refrigeration or spoiled food. In fact, he said, in annual restaurant inspections the absence of head coverings accounted for only a 10 point loss out of a total 1,000-point perfect score. He concluded that it was a misuse of time for his department to make special visits to check for head coverings.

Today, in fact, the federal Food and Drug Administration does not generally require restaurant wait staff to adopt hair restraints, though it does require restraints for those who prepare food. And there is the question of whether there are actually any negative health effects of swallowing a stray hair. Probably not.

On the other hand, there is little doubt that most Americans find it disgusting.

On the other hand, there is little doubt that most Americans find it disgusting.

Usually when diners find a hair in food at a restaurant, they immediately stop eating it. Researchers have found that “contamination psychology” is deeply irrational and not influenced by logic. Experiments in which a cockroach was brought into contact with food resulted in disgust so deep that subjects could not overlook even the briefest contact. If the food was later decontaminated they still would not eat it, even if they recognized that all traces had been removed. According to Richard Beck in Unclean: Meditations on Purity, Hospitality, and Mortality, “The rule seems to be “once in contact, always in contact.’”

A significant aspect of the disgust reaction to hair in food seems to be that it was once part of someone else’s body. (One’s own hair does not elicit the disgust response.) The reaction may be stronger if the body or behavior of the other person is viewed as socially unacceptable. In the 1920s some people disapproved of bobbed hair on women; in the 1960s there were people offended by long hair. Take the woman from Pulaski IL who wrote to a newspaper about the lack of hairnets in 1968: “When we enter a restaurant and notice a loose long-haired employe we leave. There is no law YET that we have to eat hair, nor eat with the Hippies, nor anything that resembles them.”

In the 1970s male servers were also sometimes the target of complaints if they had long hair or bushy beards.

But times change. Some restaurant patrons did not object at all to servers with long hair, especially if they were young and attractive like the “Grog Shop girls.” Grog Shops were part of the Stouffer’s company, a restaurant chain that had a history of strict policies on waitress garb, banning seamless hose and requiring waitresses to wear lace-up oxfords, girdles, and hairnets. However, when the Grog Shops opened in 1970, Stouffer’s dressed waitresses in micro-mini skirts, boots, and blouses with plunging necklines and asked them to wear their hair long and loose. I seriously doubt that health departments got a lot of complaints about the absence of hairnets.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

November 6, 2016

When presidents eat out

By now Americans are used to seeing presidential candidates chomping on corn dogs, pizza, Philly cheese steaks, and other hearty food of the people. For some – but not all — food eaten on the campaign trail has been quite a departure from their usual preferences when eating out.

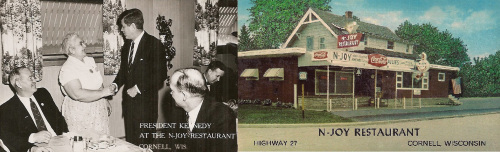

It is certainly hard to imagine that John F. Kennedy normally patronized down-home restaurants such as the N-Joy Restaurant in Cornell WI which he visited on a campaign stop. The N-Joy was known for its homemade salad dressing and chicken dumpling soup, but not for chicken in champagne sauce, a specialty of the elite La Caravelle in New York. La Caravelle also supplied a French chef for the Kennedy White House and edibles for JFK’s airplane trips. He also enjoyed Washington’s Jockey Club, which he made famous through his patronage and later became a favorite of the Reagans.

It is certainly hard to imagine that John F. Kennedy normally patronized down-home restaurants such as the N-Joy Restaurant in Cornell WI which he visited on a campaign stop. The N-Joy was known for its homemade salad dressing and chicken dumpling soup, but not for chicken in champagne sauce, a specialty of the elite La Caravelle in New York. La Caravelle also supplied a French chef for the Kennedy White House and edibles for JFK’s airplane trips. He also enjoyed Washington’s Jockey Club, which he made famous through his patronage and later became a favorite of the Reagans.

Like the Kennedys, the Reagans enjoyed dining in the best restaurants, at least before Ronald Reagan was wounded in a 1981 assassination attempt. They liked Le Cirque in NYC and Jean-Louis in Washington, the latter visited by the Reagans just eight days before the shooting. But even apart from security pre-checks, a presidential visit to a restaurant could be a very complicated matter. Before the Reagans dined with friends for an after-theater repast at Le Cirque the restaurant was visited multiple times by the city’s health and fire departments as well as FDA inspectors. Ronald Reagan’s birthday dinner at Jean-Louis required that the restaurant accept no other guests that night.

It’s hard to know how often presidents ate in restaurants in the 19th century. Possibly it was easier for them then, before 1902 when the Secret Service was created following President McKinley’s assassination in 1901. Probably many of them made their way to Delmonico’s and many, many hotel dining rooms. Harvey’s in Washington claimed it had been the “Restaurant of the Presidents since 1858” – the administration of James Buchanan – and it became famous in the Civil War when the Lincolns ate there. Presidents Garfield and Grant were said to enjoy Francesco Martinelli’s table d’hôte in New York City. Martinelli’s and Harvey’s were pretty nice restaurants compared to the cheap New York cellar where Chester Arthur ate corned beef and coffee just as he was about to take office in 1881.

It’s hard to know how often presidents ate in restaurants in the 19th century. Possibly it was easier for them then, before 1902 when the Secret Service was created following President McKinley’s assassination in 1901. Probably many of them made their way to Delmonico’s and many, many hotel dining rooms. Harvey’s in Washington claimed it had been the “Restaurant of the Presidents since 1858” – the administration of James Buchanan – and it became famous in the Civil War when the Lincolns ate there. Presidents Garfield and Grant were said to enjoy Francesco Martinelli’s table d’hôte in New York City. Martinelli’s and Harvey’s were pretty nice restaurants compared to the cheap New York cellar where Chester Arthur ate corned beef and coffee just as he was about to take office in 1881.

Theodore Roosevelt showed a taste for lively night spots. As Governor of New York, he patronized Shanley’s, a popular NYC resort, and as president was known to frequent the Café Boulevard [pictured above]. He also visited Antoine’s in New Orleans, as did Presidents Taft, Harding, and Coolidge.

Miserable meals on the campaign trail were a hallmark of the failed presidential campaign of William Jennings Bryan in 1908, and of his political career generally. According to a Collier’s magazine article, in over 12-years traveling the country he had earned the dismal honor of being a “Quick Lunch Hero.” He had eaten at over 1,700 railroad lunch counters, gulping down “mummified food” and “historical eggs.”

President Wilson might have applauded Bryan for his no-frills meals. During WWI Wilson called upon the country to embrace “the simple, wholesome, nourishing dishes which mother used to make,” gladdening the managers of the earnest, squeaky-clean Childs restaurant chain which quickly shifted to a wheatless wartime menu by substituting rice and corn meal dishes.

Whether by circumstance or taste, Harry Truman was a humble diner. He was a fan of Dixon’s Chili Parlor in Kansas City MO, where the chili was made without onions, garlic, tomatoes, or chili powder. He is shown above visiting Dixon’s on his way home for the holidays, on December 23, 1950. After leaving office he and his wife Bess drove across country, according to a 2009 NY Times story, eating “a lot of fruit plates at roadside diners.” One of their stops was at the Princess Restaurant in Frostburg MD, still in business today complete with a “Truman booth.” In 1958 Truman’s finances improved when Congress passed the Former Presidents Act, ensuring former presidents would get pensions and Secret Service protection, but somehow I doubt that this transformed him into a gourmet diner.

Whether by circumstance or taste, Harry Truman was a humble diner. He was a fan of Dixon’s Chili Parlor in Kansas City MO, where the chili was made without onions, garlic, tomatoes, or chili powder. He is shown above visiting Dixon’s on his way home for the holidays, on December 23, 1950. After leaving office he and his wife Bess drove across country, according to a 2009 NY Times story, eating “a lot of fruit plates at roadside diners.” One of their stops was at the Princess Restaurant in Frostburg MD, still in business today complete with a “Truman booth.” In 1958 Truman’s finances improved when Congress passed the Former Presidents Act, ensuring former presidents would get pensions and Secret Service protection, but somehow I doubt that this transformed him into a gourmet diner.

Although it’s probably true that Truman genuinely enjoyed Dixon’s chili and JFK really liked La Caravelle’s chicken in champagne sauce, it’s hard to know how much presidential restaurant choices were based on esthetic as opposed to political factors. President Carter had a tendency to eat in popular restaurants – such as KC’s Arthur Bryant’s [pictured above], NYC’s Mama Leone’s, and (surprisingly) Aunt Fanny’s Cabin. Were those strategic choices? If still in business today, it’s certain that Aunt Fanny’s Cabin would not be on the approved list.

According to John Mariani in America Eats Out, Presidents Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter generally weren’t big on restaurant going. Nixon, who came from a restaurant family, would sometimes go for dinner at Trader Vic’s in the Capitol Hilton near the White House. He was also said to be a devotee of NYC’s Colony where he was allowed to bring his dog into the main dining room. But the president who was hardest to keep in the White House was George H. W. Bush who enjoyed Italian (I Ricchi, DC), Chinese (Peking Gourmet Inn, Falls Church VA), seafood (Mabel’s Lobster Claw, Kennebunkport ME), and Tex-Mex (Rio Grande Café in Texas).

Apart from patronizing restaurants, often making them famous overnight, presidents can greatly influence the entire industry. For example, Franklin Roosevelt’s election was responsible for the repeal of prohibition in 1933, so critical to restaurants’ survival, while President Carter’s dislike of the three-martini lunch led him to champion cutting the deduction on business meals as part of a tax reform plan. He failed but eventually the deduction was reduced to 50%. Apparently the reform was not as disastrous to the industry as they had predicted.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

October 23, 2016

Spooky restaurants

Montmartre in Paris was the birthplace of what would come to be known in the U.S. as the theme restaurant. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Parisian entrepreneurs conjured up fantasy atmosphere in strange and unsettling forms. Themes included assassination, imprisonment, death, hell, and that harbinger of bad luck, the black cat.

As much devoted to drinking and entertainment as food, Montmartre’s ghoulish restaurants, cafes, and cabarets inspired Americans to duplicate them. Needless to say, both in France and in America such places were heavily geared to tourists and considerably short of good taste.

One Paris establishment, the Cabaret du Néant, deliberately transgressed the boundaries of decency serving wine in skulls (thankfully artificial), using coffins for tables and x-rays to turn patrons into skeletons, and – worst of all, in 1915 – digging trenches in the backyard so patrons could experience World War I warfare conditions while dining by candlelight.

In 1896 the Cabaret du Néant, renamed the Restaurant of Death, had been recreated in the Casino in New York’s Central Park, right down to a candelabra made of “skulls and bones.”

In 1896 the Cabaret du Néant, renamed the Restaurant of Death, had been recreated in the Casino in New York’s Central Park, right down to a candelabra made of “skulls and bones.”

Greenwich Village’s Moulin Rouge used coffins and skulls in its advertising, though whether it carried the theme over to its interior is unknown. It was padlocked in 1924 for serving liquor illegally. Columbus OH had a nightclub known as The Catacombs in the Chittenden Hotel [at top of page] but I was not able to learn anything about it other than that it was doing business in 1941.

On the whole, black cats and jails gained greater popularity in the U. S., both themes inspired by Montmartre. New York City’s Black Cat had many lives [shown above], being declared dead with regularity and then reappearing. San Francisco also had a Black Cat, opened in 1911, but it sounds as though it was quite tame, filled with ferns and potted palms and an orchestra hidden behind a screen. Perhaps another Black Cat Café in San Francisco, or maybe this one transformed, operated from the 1930s into the 1960s as a center for bohemians and beats as well as a gay clientele.

On the whole, black cats and jails gained greater popularity in the U. S., both themes inspired by Montmartre. New York City’s Black Cat had many lives [shown above], being declared dead with regularity and then reappearing. San Francisco also had a Black Cat, opened in 1911, but it sounds as though it was quite tame, filled with ferns and potted palms and an orchestra hidden behind a screen. Perhaps another Black Cat Café in San Francisco, or maybe this one transformed, operated from the 1930s into the 1960s as a center for bohemians and beats as well as a gay clientele.

As sinister animals go, rats and bats were also celebrated. Greenwich Village’s café, The Bat, was said to have a “macabre interior” similar to Paris’s famed Le Rat Mort (The Dead Rat). It’s likely that the advertising of both made them out to be far more sinister than they were.

As for jail restaurants and cafés, they were fairly numerous in this country. The first, labeled dungeons, opened in New York City and were places where patrons sat on crude boxes in cellars and ate steaks with their hands. They were particularly popular with men’s groups and conventioneers. In the 1920s and 1930s, restaurants and drinking places with jail themes, often with servers dressed as jailers or prisoners, appeared in Los Angeles, Indianapolis, and even a small town in Iowa. Strangely, San Francisco’s Dungeon restaurant of the 1920s, complete with cells and wardens, etc., served waffles rather than steak. But then sometimes it’s hard to keep themes on track.

I’ve been working on a future post on truly scary restaurants, ones where outbreaks of food poisoning have occurred.

Meanwhile, whether or not you find a spooky restaurant to hang out in for Halloween, have a good holiday!

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

October 16, 2016

The “mysterious” Singing Kettle

A veil of ominous mystery has spread over the remains of a California roadside tea room once known by the homey name Singing Kettle.

A veil of ominous mystery has spread over the remains of a California roadside tea room once known by the homey name Singing Kettle.

It was located near the summit of Turnbull Canyon, high above the San Gabriel Valley, on a winding road running through the Puente Hills in North Whittier. The road was completed in 1915, opening up a route filled with what many regarded as the most impressive views on the entire Pacific Coast.

Today young people drive into the “haunted” canyon at night determined to be frightened to death. Gazing out car windows they eagerly tell each other tales they’ve heard of satanic rituals, murders, and human sacrifice, hoping that behind that fence are unspeakable horrors they might be lucky enough to witness. Even the Singing Kettle tea room, perhaps because remnants of its entrance are visible from the road, has become enmeshed in dark fantasies.

Why am I laughing?

Because it strikes me as funny that a tea room from the 1920s and 1930s could be associated with horror and paranormal events. Or even that people would find its existence mysterious, wondering why it was ever there or what it really was.

I suppose that given enough time and imagination mysterious auras can envelop any mundane place, even a deserted mall or a parking garage. But still, finding a tea room scary is like being frightened by a club sandwich.

I have experienced a somewhat similar attitude before. I gave a talk on tea rooms of New York City when my book Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn came out in 2002. Afterwards a man in the audience came up and asked me why I didn’t mention the darker aspects of tea rooms. He was certain that a lot of them had been speakeasies and houses of prostitution.

Really? If that had indeed been the case, why would I not have mentioned it? It would be a good story. I’ve found no evidence of prostitution in tea rooms. Only rarely were tea room proprietors found selling liquor during Prohibition. A few places in Greenwich Village were raided in the early 1920s, and here and there the mob would open a joint and call it a tea room, though that was purely a ruse. I feel certain it was impossible to order a diet plate or a Waldorf salad in a mob tea room.

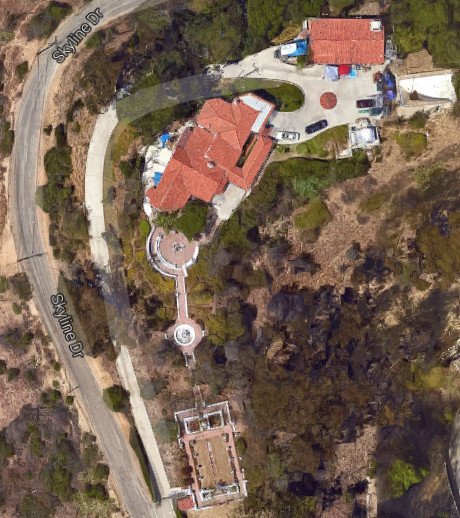

The dining area of the Singing Kettle tea room was up the hill from the pergola entrance shown on the black and white postcard above. As can be seen from a bird’s-eye view of the property, terraced stairs with fountains and shrubbery led up to the main tea room which today appears to be a residence. The view while dining would have been spectacular.

The tea room was frequented by students and staff from Whittier College, the Whittier Chamber of Commerce, and women’s clubs. It was a popular place for business meetings, card parties, wedding receptions, and bridal showers. Weddings were held in the inner courtyard of its entrance pergola.

I have not been able to discover the identity of the Singing Kettle’s proprietor. The area was filled with citrus and avocado groves and it’s possible that it was run by the wife of a grower. It’s even possible that major Southern California agricultural land developer, Edwin G. Hart, was involved in the business. That might explain why he promoted the tea room in a 1927 advertisement for his new residential development, Whittier Heights. (When he developed Vista CA he built an inn where prospective customers could stay.)

I have not been able to discover the identity of the Singing Kettle’s proprietor. The area was filled with citrus and avocado groves and it’s possible that it was run by the wife of a grower. It’s even possible that major Southern California agricultural land developer, Edwin G. Hart, was involved in the business. That might explain why he promoted the tea room in a 1927 advertisement for his new residential development, Whittier Heights. (When he developed Vista CA he built an inn where prospective customers could stay.)

The Singing Kettle was in business from 1927 until at least 1936, but probably not much longer. It surely would not have survived gasoline rationing during WWII.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

With many thanks to the reader who told me about the Singing Kettle.

September 21, 2016

Famous in its day: Aunt Fanny’s Cabin

Famous, but also infamous in its day because of how it portrayed the South before the Civil War and Emancipation as a world of smiling slaves who loved serving the kindly white people who held them captive.

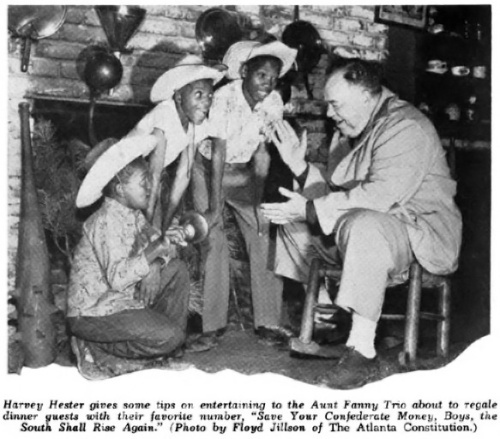

Beyond its costumed mammy servers and the Black children who boisterously recited the menu, sang, danced, and proclaimed the South would rise again, the proprietors of Aunt Fanny’s Cabin restaurant in Smyrna GA created a legend regarding its name and building which appropriated and falsified the life story of a living woman.

According to an oft-told tale, the restaurant’s core building was a relic of the Civil War era and the home of a former slave, Fanny Williams, who spent her last years sitting on the restaurant’s front porch telling of the war and its aftermath. At her death in 1949 legend had it that she was very old, her age ranging from somewhere in the 90s to much older. She was “about 112 years old” when she died, restaurant owner George Poole told a reporter in 1982.

Indeed there was a real Afro-American woman named Fanny Williams. However it was revealed after the restaurant closed in the 1990s that she was born after the Civil War and had never lived in the cabin, which itself dated from the 1890s. Poole’s estimate of her 112 years had been preposterous – only a few dozen people worldwide were known to have attained that age — but newspapers had been much inclined to lax reporting when it came to Aunt Fanny’s Cabin. Far from an ancient rural yokel, she was about 81 when she died, a city dweller in Atlanta, and active in raising funds for her church there. How willingly or why she adopted the ex-slave persona is unknown.

Fanny Williams was a servant to a wealthy Atlanta family named Campbell. She was in service to socialite Isoline Campbell McKenna in 1941 when McKenna opened a tea room-style eating place on family property near their summer home. She named it Aunt Fanny’s Cabin, hosting ladies’ luncheons, bridge clubs, and bridal showers. She leased the business in 1947, selling it to lessees Harvey Hester [pictured above instructing his employees] and Marjorie Bowman in 1954. They elaborated the Aunt Fanny legend, enacted in what are known as “Blacks in Blackface” scenes where cheerful servers sang, danced, and even joined patrons in singing “Dixie,” the anthem of the ante-bellum South. The restaurant’s third owner, George “Pongo” Poole, continued the tradition into the 1980s, although when a cabaret tax was demanded, dancing by the Black boys stopped. However, they continued to carry yoke-style wooden menu boards around their necks while they shouted out the menu offerings [child waiter shown below in 1949 before the menu boards were used].

The restaurant drew Georgians from Smyrna and Atlanta, as well as visitors from all over the country and the world. It was a tour bus stop, and a favorite of President Jimmy Carter and conventioneers such as members of the American Bar Association. Those who complained about the roles played by Black servers and the implicit celebration of slavery were characterized by proprietors as “Northern liberals,” though there is evidence that some Southerners and Westerners were also critical.

It became standard procedure when reporting on the restaurant to quote Poole about how his staff loved working there and was part of a big happy family. When interviewed, Black women servers would invariably attest to their love of the job and how they never felt insulted. To what extent this was a genuine expression on their parts is unknown.

It became standard procedure when reporting on the restaurant to quote Poole about how his staff loved working there and was part of a big happy family. When interviewed, Black women servers would invariably attest to their love of the job and how they never felt insulted. To what extent this was a genuine expression on their parts is unknown.

What is known is that many of the elements that characterized the restaurant had been subjects of contention for a long time. A 1964 survey by Wayne State University researchers showed that most Black respondents found terms such as , Aunt Jemima, auntie, mammy, spook, and darkie offensive. Many white people, especially in the South, did not understand this, and thought that calling an elderly Black man or woman Uncle or Aunt/ie was a mark of respect. As for “mammy,” despite the affection many Southerners felt for the Black women who had cared for them when they were children, it had been rejected by many Americans long before the 1960s. In the 1920s the National Organization of Colored Women’s Clubs mobilized massive opposition to a Washington, D.C. memorial to mammies proposed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. “One generation held the black mammy in abject slavery; the next would erect a monument to her fidelity,” said the club women’s official statement in 1923.

Georgia Senator Julian Bond said in the 1980s that he had little attraction to Aunt Fanny’s Cabin but could imagine that younger Blacks might find it “cute.” A journalist with the Atlanta Constitution who visited the restaurant in 1984 reported that he saw numerous Black patrons.

So, what’s the story? Did the degree of tolerance or even liking that some Black people expressed for Aunt Fanny’s Cabin mean that it held no offense to people of color? Did it mean that those who complained were thin-skinned trouble makers with an elevated sense of their own dignity who couldn’t take a joke? Did it mean, as a 1982 Washington Post story argued, that the years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were part of a post-racial age in which slavery, forced segregation, and lynching had largely ended and any remaining blatant prejudice was due simply to a few “obnoxious rednecks”?

I cannot be absolutely certain that there has never been a Black-owned restaurant that celebrated plantations, “pickaninnies,” and “mammies” of the Old South, but all the mammy restaurants I know of, mostly in business from the 1930s to the Civil Rights era of the 1960s, were white-owned. And dressing Black women servers in mammy get-ups was so commonplace back then that at times I’ve wondered if wearing that costume was a waitressing job requirement for dark-skinned women.

After the death of owner George Poole, Aunt Fanny’s Cabin struggled and subsequent owners could not revive it. It closed for the last time in 1994, sometimes recalled as partly a victim of “political correctness.” Based on the understanding that the original portion of the restaurant’s building had been a slave cabin, the city of Smyrna proposed to move it downtown to be used as a visitors’ center. After a historic structures report revealed it dated from the 1890s, the city decided to go ahead with the project on the grounds that the restaurant had itself been a significant part of the city’s history.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016