Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1534

October 14, 2013

The Five Rules Every New CEO Should Follow

Last week, an executive who was on the verge of being promoted to head his large global publicly traded company asked for my advice on how to be effective as a brand new CEO. I gave him a list and he was so appreciative that I was motivated to write a blog about it. There were five recommendations on my list:

1) Grow the Pie

The most fractious and difficult thing to do in an organization is to take resources away from someone who is used to receiving them. For this reason, growing the revenue pie is critically important to the success of a CEO’s reign. If a CEO attempts to reallocate the existing resources in order to improve the organization’s prospects, endless fights and a firestorm of protests will ensue.

If instead, the focus is on increasing revenues, investment capacity will increase and new resources can be funneled to growth priorities without needing to cut absolute resources to non-priority areas. Over time, as the revenues grow, the non-priority areas will become an ever-smaller piece of the puzzle and when the success of the priority areas has been made manifest, the CEO can shut down the non-priority areas without much hassle or fuss.

2) Follow Due Process

CEOs really don’t have to follow due process. For example, they have the power to sack anyone they want. However, it is critically important not to do that because everybody watches with a keen eye and wonders whether they will be objects of arbitrary decisions as well. Suck it up and suffer until such time as a manager who you would rather remove immediately can be given feedback and a fair chance to improve. That is a lesser evil than to establish in your team’s mind that you make up your own rules.

3) Consult Whenever Possible

Consult wherever and whenever possible with your team before making decisions, even if it drags out the decision-making. This is because your team needs to feel and function genuinely like a team. As CEO, there will be times when you have to make a decision without any support from your team because from your CEO perspective you can see that it is the right decision and your team can’t. You can get away with these decisions without destroying the team dynamics, but only if you save it for very rare occasions.

4) Set High Strategy Standards

The easiest thing for managers to do is to avoid making the explicit choices that are essential for quality strategy. But mediocre strategy results in lots of work for little reward. So it is critical for a new CEO to establish that direct reports have the responsibility for making logically consistent and unique strategy choices in their areas of responsibility. You need to signal that you won’t create their strategy for them but will help if asked — because nothing is more important than having a high bar for strategy.

5) Maintain a Big Tent

The new CEO needs to signal from inception that the organization will be a big tent that welcomes diversity, not a monoculture with only people who resemble the CEO. It is much harder to find the requisite personnel for a monoculture and the reward if you do find them is that they are less effective!

My favorite ‘CEO’ of all time is former Baltimore Orioles baseball manager Earl Weaver, who won multiple World Series Championships with rag-tag assortments of personalities that were arguably the most diverse that baseball has ever seen. He could always sign or trade for players to fit in his tent because of the breadth and inclusiveness of his definition of ‘fit’. My least favorite is Pete Rose who insisted that every player manifested the ‘Charlie Hustle’ persona for which he was famous in his former life as a superstar player. Rose traded away players who ‘didn’t fit’ and built monoculture teams that hustled their way to persistent mediocrity.

I encouraged the new CEO to act immediately on these five recommendations because in the rough-and-tumble world of the modern CEO, second chances are rarely given. And if a CEO starts off reallocating the existing pie, declaring force majeure, acting unilaterally, accepting mediocre strategy and closing ranks to only the comfortable colleagues, the die gets cast pretty quickly. So make those first few moves deliberately — and in accordance with this list.

Meet the New Face of Diversity: The “Slacker” Millennial Guy

In the past, men demonstrated their manliness at work by mooning the trading floor (to quote one conversation I had recently) or pounding their chests à la Alpha-Ape (to quote someone I interviewed a few years back). “Come back with your shield or on it,” a partner used to joke in the 1980s whenever someone in my husband’s BigLaw firm went to court. Extreme schedules remain a key metric of manliness. “He’s a real man; he works 90-hour weeks. He’s a slacker; he works 50 hours a week,” commented a Silicon Valley engineer.

And men are paid handsomely for putting in such hours. An important new study by Youngjoo Cha and Kim A. Weeden reports that the wage premium for “overwork”—working more than 50 hours a week—has risen sharply. In 1979, there was actually a wage penalty for overwork; but this turned into a wage premium after the mid-1990s. Because men tend to overwork more than women, the rising overwork premium raised men’s wages more than women’s, and has effectively erased the advantage women gained by increasing their higher education levels.

All this helps explain why, according to one survey, 75 percent of male executives are married to homemakers. It’s simply not possible to work 90 hours a week and see to your own basic needs – much less support someone else’s career. It works the other way, too: with only one salary to rely on, those husbands need all the wage premium they can get. But there’s an impact of these kinds of arrangements – he works all of the time, she does all the housework – on organizations. A recent study reported that male managers in such marriages found organizations with egalitarian gender attitudes less appealing and were more likely to give women low job evaluations.

This mindset, created by the peculiar demography of upper-level management, is increasingly out of sync with most of the workforce. Younger men increasingly want schedules that work around family needs — just as women have been demanding for years.

While the media, consumed with the idea of “mommy wars” and “queen bees,” has largely missed the tug of war that has emerged among men, sociologists have been busy uncovering the change. Statements like that of the Silicon Valley engineer who expressed resentment at his manager’s demands by saying, “[he] doesn’t have two kids and a wife, he has people that live in his house, that’s basically what he has,” as reported by Marianne Cooper, are increasingly common among younger men. “It’s akin to winning a pie-eating contest where the prize is more pie,” observed a law firm associate, rejecting law firm partnership as a goal.

This creates a big gap between older men and their protégés. Katherine Kellogg, in her important study, found that the brotherhood of surgeons was dominated by Iron Men who see themselves as “the biggest, baddest SOBs around, beating up on the meddies [medical residents] and beating upon radiologists.” Iron Men live for the operating room, dismiss post-op care as boring, scorn rest (“I am hardcore and I need no sleep!”), and brag that a surgical residency program has a 110 percent divorce rate (“Guys would come in married, get divorced, get remarried, and get divorced again”).

What’s intriguing is that many younger men won’t play the game. Kellogg studied four Boston hospitals’ response to a new accreditation requirement that surgical residents be limited to 80 hours a week, down from the traditional 120-hour schedule.

Women supported the new 80-hour rule—no surprise—but so did many Millennial men. Kellogg found three main groups of such men:

One group, which she termed “patient-centered men,” wanted to spend more time listening to patients. This highlights the point, too often forgotten, that 24/7 work ethic often compromises work outcomes—a finding reported in a variety of industries, including Silicon Valley and consulting. Another group rejected Iron Men’s work-all-the-time ideals. “You want to get home to see your kids. You want to see your kids grow up,” said one. For a third group, the issue was not work-family balance but manliness itself. They found the Iron Men’s macho displays off-putting and inconsistent with their image of what it took to be an egalitarian man, a self-image that was important to them. In one hospital, all these groups banded together and changed residents’ schedules to observe the 80-hour a week rule.

In this, Millennial men are joining another group of longstanding skeptics: blue-collar men. While elite men “often view ambition, dynamism, a strong work ethic, and competitiveness as doubly sacred because they signal both moral and socioeconomic worth,” as Michèle Lamont has written, blue-collar guys disagree. To them, this looks more like selfishness. Lamont’s 2000 study quotes a bank supply salesman: “A person that is totally ambitious and driven never sees anything except the spot they are aiming at.” An electronics technician agreed, criticizing people who are “so self-assured, so self-intense that they don’t really care about anyone else…. It’s me, me, me, me, me.”

This cross-class disagreement also emerges clearly in Naomi Gerstell and Carla Shows’s study contrasting emergency medical technicians with physicians. The doctors typically devoted their lives to work and had wives dissatisfied by their inattention to family life. The EMTs also worked longer hours than their wives but were involved in everyday fathering in ways doctors were not, picking kids up from day care or school and staying home when they were sick. EMTs used shift swaps to facilitate child care. Many worked overtime only after consultation with their wives, who vetoed it when they felt the work would interfere with family needs. Others refused overtime completely. “I will totally refuse the overtime. Family comes first for me,” said one.

These EMTs sound a lot like the Millennial surgeons. Both groups of men are reinventing the meanings and the metaphors of work. The surgeons who aligned against the Iron Men abandoned the image of staff surgeon as hierarchical warlord, replacing it with an image of a team coach. “They referred to chiefs as ‘coaches’ rather than ‘commanders,’ to [senior residents] as ‘team members’ rather than ‘wingmen…’ and to interns as ‘rookies’ or ‘good prioritizers’ rather than as ‘beasts of burden.’”

Millennial men are beginning to do what women have done for decades: to work as consultants or start their own businesses that give them the flexibility for better work-family balance. A forthcoming study of New Models of Legal Practice by the Center for WorkLife Law (which I direct) documents lawyers in their prime who left large, prestigious law firms so they could practice law in ways that allow them to be more involved in children’s lives. When he started his own virtual law firm, said a former in-house lawyer, “I had a two-year old and a baby and I definitely wanted to be at home and spend time with my kids and my wife and I saw there was an opportunity.” Being able to work at home, for him, was “a big benefit.” Big Law refugees signal the growing generational divide among elite men about what it means to put family first, and what it means to be a man.

Like blue-collar guys, these younger professional men have different understandings of ambition and different ideals of fatherhood. If they’re unable to change their organizations to allow time for family life, like the young surgeons were, they will leave. (Big Law, take note.)

Increasingly, managing fatherhood involves difficult conversations about what it means to be a good father, an ideal worker, and a “real” man. Today, managing diversity is not limited to women, LGBTQ individuals, or people of color. Diversity also means managing men who aren’t like you—and don’t want to be.

Applying a Face Cream Can Help You “Save Face”

Research participants who had been induced to recall awkward moments such as walking into opposite-sex restrooms showed a decrease in embarrassment if they applied what was described as a restorative cream to their faces (an average decline of 1.69 on a zero-to-10 embarrassment scale), says a team led by Ping Dong of the University of Toronto. The findings show that people can metaphorically “save face” by use of a physical product – yet another demonstration that many psychological metaphors have physical spillovers. The researchers point out that the study was conducted in Asia, where concepts of losing and saving face are more pervasive than in the West.

The Age of Social Products

We are moving from a world in which physical products are separate to one in which they are connected. Computers were just the beginning. Appliances and engines now send alerts when they need to be serviced. Cameras upload their photos automatically. Vending machines trigger their own restocking. Crops feed and water themselves.

This shift has many monikers: “The Internet of Things” and “The Internet of Everything” are two of the most popular. But the history of the Internet suggests that this is just the beginning. The real change will happen when products aren’t just connected, but social. Instead of the Internet of Things, we should be thinking about the Social Network of Things. To take advantage of this shift, you need to start thinking about the social life of your products.

What makes the Internet of Things possible is the confluence of multiple technologies: inexpensive sensors, wireless networks, and cloud computing. The ability to access data and computing resources from anywhere means that products don’t need to have computers and memory built into them. They can just use the cloud. Put sensors, a simple processor, and a wireless connection together and you have the makings of an intelligent and connected product.

The Internet of Things is already expected to transform customer service, business models, and advertising. But we should remember the evolution of the Internet. The early days (Web 1.0) was about computers talking to computers. A few years later (Web 2.0), people started talking to people. The Internet was disruptive as a connected infrastructure, but it became explosive when it got social.

Today, most of the discussion about the Internet of Things is about products being connected. But just because your product is connected doesn’t make it social. For products, the real revolution will come when objects aren’t just passing information back and forth, but collaborating around a shared purpose.

This insight is behind Google’s recent acquisition of Waze for $1.1 billion. Google already has the best map and traffic program, so why would they want another one? Was it just to keep it out of the hands of Apple or Facebook? We think not.

Among other things, Waze cracked the code on social products. Google Maps is a data network, while Waze is a social network, in this case of cars, phones and people. Waze creates a constantly updating repository of traffic information, much like Wikipedia creates a dynamic repository of encyclopedic information. However, in this case, it is cars, phones and people who are collaborating to create the body of knowledge. Waze provides a glimpse of how the car can become a social device by using the little data created by each individual car and driver. According to the head of Google Maps, the goal is “to harness the power of Google technology and the passion of the Waze community to make it easier to navigate your daily life.”

Waze shows us how the cars of the future will not only connect to each other but also leverage the collective intelligence of that community of connected cars. We can see this in other areas as well. Connected e-readers already help every individual reader benefit from the actions of the community. Nike is betting on a future with connected shoes, where each individual shoe learns from the data aggregated from a network of connected shoes. Social products leverage the power of the community to learn from other products.

So how do you create a social product?

First, you need a product that is smart and connected. You can build your own (like the thermostats and home alarms from Nest) or use someone else’s device. It might be a smartphone (think Waze), a consumer device with open APIs (like Nike’s FuelBand), or a commercial device with a strategic alliance (like Opower and electric utilities).

Second, you need to make the product social. This requires a platform where people and products are connected in a collaborative network. Each individual product and each user benefits from being part of a community of fellow products and users. For example, Nest’s thermostat and smoke detector work together. When the alarm detects carbon monoxide, it tells the thermostat to turn off the furnace.

In the case of Waze, each car and driver benefits from the information gleaned and aggregated from the community of cars and drivers. That’s not all. A Department of Transportation study demonstrates how cars of the future will talk to each other. Cars within 1,000 feet of one another will send out their speed and location to the others, which will then notify the driver as needed. Google’s driverless cars will be able to make adjustments automatically. In this future state, is it the cars that are driving, or the social networks?

If you are considering building a strategy around social products, you have a few choices. You need a connected product, a social network of people, a social network of products, and a collaborative platform for interaction, data exchange, and analytics. The good news is that you don’t have to do all of this yourself.

Instagram leveraged an existing connected product (smartphone camera) and an existing collaborative platform (Facebook) to create a social network of connected camera-phones.

Qualcomm Life is creating a new collaborative platform to transform existing connected devices (for mobile health and fitness) into social products. Recognizing they also needed a social network of people, they recently purchased HealthyCircles to help physicians, patients, and families coordinate care and support.

Nike is creating an entire ecosystem of connected products (Hyperdunk+ shoes), social network of products (FuelBand), social network of people (Nike+), and collaborative platform (Digital Sports).

The Age of Social Products will change the basis of competitive advantage. Companies have traditionally focused on product supremacy, outdoing their competitors with better features and attributes. In an age of social products, competitive advantage comes not from product features but from network effects. Companies succeed by having products that better leverage the intelligence of the network of other connected products. This is a shift in mindset from standalone-product thinking to connected-platform thinking.

The Age of Social Products is dawning. Companies that create products that are smart, connected, and, most importantly, social, will not only survive, but thrive.

October 11, 2013

Why Law Firm Pedigree May Be a Thing of the Past

Have you ever heard the saying: “You never get fired for buying IBM”? Every industry loves to co-opt it; for example, in consulting, you’ll hear: “You never get fired for hiring McKinsey.” In law, it’s often: “You never get fired for hiring Cravath”. But one general counsel we spoke with put a twist on the old saying, in a way that reflects the turmoil and change that the legal industry is undergoing. Here’s what he said: “I would absolutely fire anyone on my team who hired Cravath.” While tongue in cheek, and surely subject to exceptions, it reflects the reality that there is a growing body of legal work that simply won’t be sent to the most pedigreed law firms, most typically because general counsel are laser focused on value, namely quality and efficiency.

There’s no question that the legal industry is going through upheaval. Law schools are shuttering and powerful old firms have fallen. In Dina’s recent article “Consulting on the Cusp of Disruption,” she and co-authors Clayton Christensen and Derek van Bever argue that despite the disruption in consulting and in law, there will always be complex, high-stakes problems for which a brand-name, solution shop firm will be required, but that as disruption marches up-market and more problems find commoditized solutions, there will be a thinning at the top of the pyramid. Only those firms that can change quickly enough to meet their clients’ increasing demands for greater value will survive.

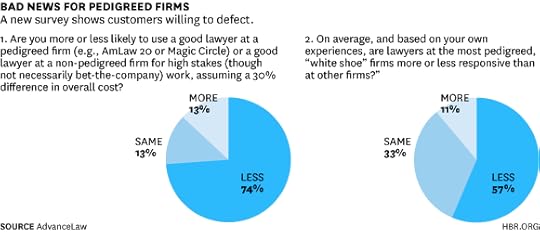

A recent survey of General Counsel at 88 major companies conducted by AdvanceLaw (an organization founded by Firoz) supports this argument. The results suggest that GCs are increasingly willing to move high-stakes work away from the most pedigreed law firms (think the Cravaths and Skaddens of the world)… if the value equation is right. (Firms surveyed included companies like Lenovo, Vanguard, Shell, Google, NIKE, Walgreens, Dell, eBay, RBC, Panasonic, Nestle, Progressive, Starwood, Intel, and Deutsche Bank.) The results of the two questions the survey asked are below.

That 74% of GCs preferred the less pedigreed firm under the circumstances described in question 1 reaffirms that clients are becoming more and more comfortable with using a wider range of firms. Moreover, in the U.S., the current cost premium for an AmLaw 20 firm relative to, say, an AmLaw 150 or 200 firm is typically far more than 30%. Factoring in lower hourly rates as well as the greater efficiency most clients say the other firms deliver, we are likely talking about an overall cost premium in the 60+% range.

What can also seem non-intuitive is that only 11% of GCs surveyed felt that pedigreed firms, despite the price premium, actually were more responsive (a key element of client service). However, this actually mirrors Firoz’s experience at AdvanceLaw, where firms of varying sizes and pedigree are successfully unseating AmLaw 20 and Magic Circle incumbents on high stakes work (e.g., a recent M&A deal valued at $500 million; national trial counsel for a significant multi-state class action). These firms have been receiving impressive evaluations from GCs and in-house counsel on responsiveness, expertise, quality and efficiency. One reason for this is that top talent is increasingly dispersed, not residing solely at the most pedigreed of firms.

This AdvanceLaw survey suggests that clients are serious about moving high-stakes work away from the most pedigreed (and expensive) law firms. So, are white shoe firms feeling the impact of this mindset change? When we examined revenue per lawyer (a proxy for a law firm’s ability to command a price premium) across a sample of firms, we found that growth was highest among non-pedigreed firms. Our sample of 15 especially highly reputed firms (including the likes of Cravath, Skadden, and Sullivan) experienced an average increase of only 2.9% in revenue per lawyer over the 5-year period from 2007-12. In comparison, a sample of 15 smaller, comparatively less known firms posted average growth in revenue per lawyer of 12.7% in the same period.

Surprisingly, many (though not all) pedigreed firms are choosing to not yet compete on value, arguing that this would diminish their future ability to compete for the shrinking pool of high-stakes / high-margin work. However, as the survey and financial analysis reveal, this ends up opening the door for other law firms (as well as non-traditional providers) to slip in and chip away at what we all once assumed were unassailable relationships between the most pedigreed law firms and their clients.

But it would be unwise to count out white shoe firms’ ability to adapt over the long run. Their higher margins could be reinvested into client service innovations. They also have the potential to roll out differentiated lower cost solutions (as some have already begun doing in the form of contract lawyers). Of course, there are many challenges to any of these strategies, not the least of which is firm culture. But make no mistake: the competition for market share in the legal space is tough and getting tougher.

How Twitter’s Leadership Drama Explains its Success

One founder pushed aside in the early days of the company, his name scrubbed from its founding story. Another ousted from the CEO role by a co-founder, former boss, and seed investor. That founder himself booted from the CEO role later on by VCs, only to watch the company’s initial CEO return to the day-to-day operations alongside yet another chief executive, who joined well after the founding.

This is the origin story of Twitter, at least according to New York Times reporter Nick Bilton, whose forthcoming book on the subject is excerpted in the Times’ Magazine this week. And it’s a far cry, he asserts, from the version that the company and its current leadership have repeated to the press.

Bilton’s account of how the company actually got its start reads like high drama, but is it at all surprising? Not to those who’ve been through a few startups, or studied the challenges that founders face. Earlier this year, Harvard Business School professor Noam Wasserman published The Founder’s Dilemmas, the result of a decade’s worth of survey data on the challenges startups face. His work suggests that Twitter didn’t just succeed in spite of all the drama Bilton reports, but to some extent because of it. Put another way, the frequent swapping out of executive roles at different stages has almost certainly been key to Twitter’s success to date.

If that seems counterintuitive, consider the “fundamental tension” that Wasserman presents in his book (and in a 2008 article for HBR): founders can choose to be “rich” or to be “king.” Of course, they may end up neither, but Wasserman’s research finds they seldom end up both:

The “rich” options enable the company to become more valuable but sideline the founder by taking away the CEO position and control over major decisions. The “king” choices allow the founder to retain control of decision making by staying CEO and maintaining control over the board—but often only by building a less valuable company. For founders, a “rich” choice isn’t necessarily better than a “king” choice, or vice versa; what matters is how well each decision fits with their reason for starting the company.

The path to value typically requires a change in leadership, not because VCs are somehow nefarious, but because they recognize that different stages of a startup require different kinds of leaders. As Wasserman wrote for HBR:

A technology-oriented founder-CEO, for instance, may be the best person to lead a start-up during its early days, but as the company grows, it will need someone with different skills.

That fits Jack Dorsey, who became Twitter’s first CEO after playing the role of lead engineer as the product was being developed within co-founder Evan Williams’ previous company Odeo. Williams, who previously had sold Blogger to Google, later took the reins and managed the company for two to three years. Sure enough, the company’s growth soon warranted yet another shift, and the board put COO Dick Costolo in the CEO role.

These shifts are the stuff of truly riveting journalism, but aren’t surprising. As Wasserman summarizes:

When [founders] celebrate the shipping of the first products, they’re marking the end of an era. At that point, leaders face a different set of business challenges. The founder has to build a company capable of marketing and selling large volumes of the product and of providing customers with after-sales service. The venture’s finances become more complex, and the CEO needs to depend on finance executives and accountants.

Sound like anyone you know? From Bilton: “Dorsey had also been managing expenses on his laptop and doing the math incorrectly.” Continues Wasserman:

The organization has to become more structured, and the CEO has to create formal processes, develop specialized roles, and, yes, institute a managerial hierarchy. The dramatic broadening of the skills that the CEO needs at this stage stretches most founders’ abilities beyond their limits.

That proved true even for the relatively more experienced Williams.

Nor is it surprising that these shifts caused drama within the team.

Four out of five founder-CEOs I studied resisted the [appointment of a new CEO], too. If the need for change is clear to the board, why isn’t it clear to the founder? Because the founder’s emotional strengths become liabilities at this stage. Used to being the heart and soul of their ventures, founders find it hard to accept lesser roles, and their resistance triggers traumatic leadership transitions within young companies.

But there is one insight from Wasserman’s research that does push back on the narrative presented in the Bilton piece: the focus on executives’ shortcomings as a motivation for change. No doubt Dorsey and Williams did each struggle with the managerial challenges of such a fast-growing company; everything we know about startup leadership predicts as much. What Wasserman points out, though, is that these challenges are the result of executive success more than failure:

Success makes founders less qualified to lead the company and changes the power structure so they are more vulnerable. “Congrats, you’re a success! Sorry, you’re fired,” is the implicit message that many investors have to send founder-CEOs.

And Twitter has no doubt been a success, at least if Williams and Dorsey hoped to be rich rather than king. (Interestingly, Williams is mentioned in Wasserman’s HBR article for having bought back control of Odeo from investors, in order to restore his kingship.)

From the perspective of value creation, what investors ultimately care about, the executive shifts at Twitter were probably critical to the company’s continued growth. When the case study on Twitter is eventually written, it will likely be less about personal drama and more about the leadership transitions necessary for startup success.

Don’t Treat Your Career Marathon Like a Sprint

In high school, I was on the cross-country running team. I was only a decent athlete, and midway through the season, my coach demoted me to the “B team.” I wanted to prove to him I deserved to be back on the “A team,” so I launched into my first “B race” at a far faster pace than normal.

I was leading the pack almost the entire way, and, even though my legs were burning, I thought that I could win, get a shiny medal, and more importantly, get my deserved promotion higher up the team pecking order. My coach was thrilled by my “all in” performance. Coming down the last ½ mile of the 3 mile race, however, my legs turned to jelly and I fell from the lead all the way to the back. I even threw up at the end of the race. Afterwards, my coach asked what happened.

I think he knew the answer, and most of us who work in competitive fields know it too. I hadn’t paced myself. I lost my race because I treated a three-mile run like a 100-meter dash. As a result, I had no energy in reserve for the last, most important stretch.

It’s possible in the realm of knowledge work, too, to work so hard for so long under so much pressure that we run out of energy, not just to the detriment of our family lives or our mental and physical well-being, but also with terrible consequences for our long-term job performance. Yet many of us launch into our workweeks, six-month projects, and even whole jobs as 100-meter dashes, seemingly oblivious to the long race over uneven terrain we are actually running.

According to a recent Families and Work Institute study, one third of employees report chronic overwork. Those reporting chronic overwork cite:

Extreme job demands, in that they are given more work than can be reasonably accomplished even in 60 hour workweeks

Expectations that they stay connected to work remotely (email, phones, text) after work hours

The inability to avoid “low value-added” tasks such as paperwork or unnecessary meetings

Having too many projects to work on at one time, diminishing their ability to focus and prioritize among projects and creating too many interruptions and distractions.

As a believer in work-life balance, I often make the argument that “all in” and “work before all” corporate cultures and work expectations are actually enemies of sustained high performance. Smart companies, who know they stand to gain most by retaining the talent they develop, know better than to make their people choose between employer and family.

However, I also firmly believe that the problem is circular, and a worker’s own lack of balance can lead to chronic overwork, and, by extension, to poorer work performance over time.

A few months ago, I was at a Leadership Summit for the Thirdpath Institute, an organization that advocates for work-life balance. One speaker told an anecdote that stuck with me. It was the story of a man who ran a small law firm, talking with a potential client. The client questioned whether to hire this firm because it had advertised itself as a family-friendly workplace. “What happens when an emergency comes up during my case?” asked the prospect. “How do I know you’ll be able to respond?”

“We can respond better because we have a balanced approach,” explained the attorney. “And here’s why. We prioritize better, are staffed more appropriately, schedule time for long-term planning, and yes, allow for time outside of work for our lawyers to have full family lives. Because my lawyers aren’t chronically overworked, they have the capacity – in terms of time, energy, and mental focus – to respond effectively to your crisis situations. We are much more able to rise to these occasional challenges because we don’t treat every day like a crisis.”

He got the client.

In a highly competitive global economy, employers need people to put in full days working hard, and sometimes to put in longer days than others. But if workloads are draining more energy than is being replenished, the pace cannot be sustained. How many talented contributors do we lose because of extreme job demands? How much productivity and quality do we sacrifice because of accumulated fatigue? Occasional overwork may be a necessity, and even embraced by ambitious men and women trying to make the “A team.” Chronic overwork leaves everyone, employees and managers, in the dust.

Case Study: A Short-Seller Crashes the Party

When the well-known hedge fund manager and short-seller Jeremiah Hughes first put Terranola in the spotlight, issuing ominous warnings about unsold products, a looming patent expiration, and flawed growth projections, the considered judgment of the executive team was to do nothing.

“I refuse to dignify this attack with a response,” said Henry Guillart, the CEO, just hours after Hughes had given his initial negative presentation at an investor conference in New York. That decision turned out to have serious consequences. Terranola’s stock began tanking that afternoon, precipitating a slide that took the Seattle-based company’s reputation, employee morale, and ability to raise capital along with it.

A month later, when Hughes mounted a second attack, everyone expected Terranola to counter. But behind closed doors, its leaders were torn: They realized that responding this time might lead to even more trouble.

(Editor’s Note: This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.)

The Power of the Power Bar

Terranola is the company behind those granola bar machines you see on every kitchen counter nowadays. It’s hard to believe that little more than a decade ago people didn’t even think of making their own snack bars at home. That’s a testament to the speed and thoroughness with which Terranola has dominated the business sector it invented.

By now everyone has heard the story of how the company’s flagship product, the Express bar-making machine, came to be. Henry Guillart had been running an organic food distributor when he came across a sandal-wearing inventor in a Whole Foods store demonstrating what was then called the Power Bar Press. It was ugly, clumsy, and expensive, but Henry immediately saw its potential and bought the idea. He renamed his company and put a team of engineers to work solving the product’s mechanical, food safety, cost, and design flaws. When the Express finally emerged, it was a peach: simple, speedy, and elegant. Henry positioned it for several customer segments at once: gadget lovers, foodies, hikers, moms packing their kids’ lunches, and people with dietary restrictions, such as nut allergies.

The business model centers on the old razor blade strategy: Sell the machine at just above cost and make high margins on the system’s consumable element – patented plastic pods. These come in fill-it-yourself kits for consumers who like to exercise their creativity: If they’re tired of cinnamon-oat-raisin, they can make pistachio-millet-honey-blueberry. The pods are also available prepacked with nuts, grains, dried fruits, and flavorings for Express owners who simply like using their gadgets.

Half a dozen companies worldwide are licensed to manufacture the machines and pods and sell them to retailers and distributors, paying royalties to Terranola on each sale. So although the company makes almost no money on the machines, it earns a profit of about 15 cents on each pod, not to mention additional licensing fees from food brands, such as Kellogg’s and Nature’s Promise, that are keen to be associated with a wildly popular product.

Investors adored the Terranola story. When the Express launched, sales of food bars in the United States were already $2 billion annually and expanding by double digits. Europe and Asia were the next frontiers. Terranola’s first five years of sales were unprecedented for kitchen gadgets, and revenue soared to $1.1 billion. Competitive products came on the market, but none were as popular as the Express. Michelle Obama bought one for the White House, and the president gave one to David Cameron as a Christmas gift. Terranola’s market cap skyrocketed to $8.1 billion, and even then many analysts remained bullish, saying that household penetration of Express machines could increase threefold in the United States and Canada alone.

Yet the company also attracted a lot of short-sellers – investors who borrowed shares from a brokerage and sold them, hoping to buy them back later at a discount, return them, and pocket the difference. At the stock’s peak, nearly a third of shares were sold short. It seemed that many market players, notably Jeremiah Hughes, thought the Terranola story was too good to be true.

Doom and Gloom

Hughes was the founder of a hedge fund managing more than $6 billion in assets. He had become known for bringing down overvalued companies by shorting their stock and then publicly shaming them. The first thing he did in his 20-minute presentation at the Council of Value Investors was to show, on the basis of household income and food bar consumption data, that Terranola might conceivably be able to double its sales in the coming years, but it certainly couldn’t triple them. Then he made a few ominous comments about warehouses full of unsold pods and launched into an analysis of threats to the company’s intellectual property – specifically the looming expiration of a key patent on Terranola’s pods and the possibility that its own licensees would soon be able to make identical, lower-priced ones for use in the Express or copycat machines. He argued that the company’s current effort to get a patent extension was bound to be unsuccessful, because its so-called technical improvement consisted of a trivial change – making the pods fluted rather than smooth.

In a final flourish, Hughes recalculated Terranola’s likely earnings per share at just one-third the level that was being bandied about by the bulls. “Once the patent expires next year,” he told the crowd in the Waldorf Astoria ballroom, “this business model will crumble – just like an old, stale granola bar.”

A.J. Densmor, Terranola’s CFO, saw those words on Twitter about one minute after Hughes had uttered them. An agitated Henry burst into his office only a few seconds later. “Jeremiah Hughes is talking trash about us!” he nearly shouted.

“I know,” A.J. said.

They called in the company’s investor relations and PR chiefs and, after a long discussion, agreed to hunker down and watch how the situation played out. “Everyone knows that a short-seller is just trying to make money for himself by driving the stock down,” Henry insisted. “This will blow over.” A.J. wanted to believe him. But of course Hughes’s presentation was a tipping point. It irrevocably changed the way investors perceived Terranola.

A week later A.J. spoke up. “We have to rebut,” he told Henry. “We’ve got a legitimate chance for a patent extension. Investors need to know that.”

Henry shook his head. “What he’s doing is unethical and immoral, and I’m not going to get down in the mud with him. I know the investors will come around.” Confident words. But A.J. sensed a deep discomfort in the CEO, as if Henry was afraid to tangle publicly with Hughes.

As CFO, A.J. was painfully aware of the consequences of the stock slide, which now amounted to 20% from the peak, with no bottom in sight. Beyond the intangibles of poor publicity and anxious employees, a sinking share price wreaked havoc with the company’s compensation structure, which relied on stock options as incentives. Even more important from a strategic perspective, creditors would balk at further loans until the uncertainty was resolved, making it harder for the company to raise money.

The timing of all this was particularly bad. Terranola had been moving forward with A.J.’s plan to acquire all six of the licensees that made Express machines and pods. With the company’s share price sinking and its cost of capital rising, those deals might have to be put on hold. But if they didn’t go forward and the patent expired, the licensees might indeed become competitors, and Hughes’s prophecy would be self-fulfilling.

In subsequent weeks, as the stock sank to 30% below its peak, Terranola’s silence created an information vacuum into which all sorts of rumors and speculation rushed. One analyst pointed out that although the company’s earnings were spectacular, often beating forecasts by 40%, its sales were more modest, typically meeting forecasts or bettering them by just a little. “How is that possible?” she asked, implying that the books were somehow being cooked. Shareholders began contacting the company, demanding that it do something. Still Henry refused to respond.

But when his marketing chief got a tip that a global snack industry website was about to publish an interview with Hughes about Terranola, A.J. could tell that Henry was ready to reconsider. He suggested a meeting of the executive team to plan a response or even launch a preemptive attack, and the CEO agreed.

The discussion was heated. There were calls for a lawsuit against Hughes. Someone suggested that they advise the New York attorney general’s office to initiate a case against him for stock price manipulation. Terranola’s chief counsel floated a plan to ask shareholders to demand the physical certificates for their shares, preventing brokers from lending them to short-sellers and possibly forcing people like Hughes to cover their positions. A.J., for his part, said the company should launch an aggressive PR campaign, encouraging reporters to examine the company’s assumptions and forecasts in detail.

But everything changed when the Hughes interview appeared the next day.

A Veiled Threat

“What’s your reaction to Terranola’s silence about your analysis?” the interviewer had asked.

“I’m impressed by it, to be honest,” Hughes replied. “I would have thought they’d do what ExSolv did back in the 1990s. ExSolv claimed to have a technology for extracting oil from sand. Investors didn’t believe the hype, so they shorted it, and the company fought back tooth and nail. They told shareholders to request immediate delivery of their stock certificates. They hired private investigators to find out who was spreading misinformation. They even sued one fund manager. They damaged a lot of people’s reputations and cost a lot of people a lot of money. And lo and behold, the company turned out to be a fraud. That’s chutzpah!

“I’ve come to believe that the harder a company fights me, the more likely they are to be lying. So I’ve always got more ammunition in store. I always know a lot of things that I don’t say publicly. I wait and see how a company is going to react – I let them take the lead. If they come after me with lawsuits and investigations and accusations, I let them have it. And in the case of Terranola, believe me – well, enough said.”

A.J. went to Henry’s office after reading the interview. The two men were thinking about the same thing: Hughes’s cryptic reference at the Waldorf Astoria to warehouses full of unsold pods. For a long time Terranola had been buying machines and pods from its licensees to sell through its website and branded sections in department and big-box stores. As a result, it booked hefty royalty payments before the products were actually in consumers’ hands. That’s why the company’s earnings were so much better than its sales.

But A.J. knew perfectly well that much of this inventory was indeed being stored, and that the ingredients in the prepacked pods would have to be discarded if they sat around too long. He’d repeatedly told Henry that they should stop the practice or they’d risk being accused of self-dealing and juicing the company’s earnings. But he’d also figured that the problem would go away when Terranola acquired the licensees. Unfortunately, it seemed that Hughes had somehow found out. He probably didn’t have enough solid information to go public, but if pushed, he would undoubtedly dig around and get it. A.J. could only imagine how that would look to analysts and to Terranola’s shareholders. Would the share price – and, indeed, the company – ever recover?

Just then the chief marketing officer, Janet Washington, came in. She’d read the interview with Hughes too, but she didn’t know about the royalties practice, so she was puzzled by his comments.

“What was he talking about?” she asked.

Henry and A.J. were silent.

“I think we should go ahead and get aggressive with him,” Janet said. “Who is he to tell us what we can do? The sooner we get our side of the story out there, the better. When can we start?”

Question: How should Terranola respond to the short-seller’s accusations?

Please remember to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

What It’s Like to Work for Jeff Bezos (Hint: He’ll Probably Call You Stupid)

Ever wondered what it's like to work at Amazon? Or to be one of its competitors or potential acquisitions? Or even to be related to founder Jeff Bezos? Look no further than this lengthy piece by Brad Stone, whose book on Bezos and his company comes out in later this month (natch, that's an Amazon link). On my first question, Bezos isn't a particularly nice boss. Amazon's culture is "notoriously confrontational," with Bezos regularly embarking on what employees call "nutters," which largely consist of him shooting off phrases like "Are you lazy or incompetent?" "I'm sorry, did I take my stupid pills today?" and "If I hear that idea again, I'm gonna have to kill myself." And yet many people who work there thrive in this environment and generally find that Bezos is right on target when he flippantly dismisses an idea or prioritizes a customer complaint over being civil to his underlings.

And unlike many top companies that offer employees flexible working arrangements and other perks, Amazon gives new employees "a backpack with a power adapter, a laptop dock, and orientation materials," and reimburses only part of their public-transit passes. This is a huge jump from the 1990s, however, when "Bezos refused to give employees city bus passes because he didn't want to give them any reason to rush out of the office to catch the last bus of the day."

As for my second and third questions, you're going to have to read the article. In particular, what happens when Stone tracks down Bezos's biological father is astonishing.

Barbarians at the GateMaking the Leap Into Developed Markets London Business School

How will established companies in the U.S., Europe, and Japan respond when companies from emerging markets invade developed economies with "good-enough" substitutes for what the incumbents have been successfully selling in the homeland? It's going to happen sooner or later. Tata Motors, for example, is expected to launch a full-scale attack on American markets with its ultra-cheap cars. When the assault comes, companies can take a lesson from Gillette, which dealt with a similar threat from Bic's cheap disposable razors in the 1990s. By introducing disposable-razor innovations such as lubrication strips, Gillette seized the initiative and essentially redefined the market, writes Costas Markides. Gillette "managed to convince consumers that they should expect more from their razors and that Bic was not really 'good enough' for them." This kind of nimble response from tough, wily corporations in the developed world will likely limit the invaders' success in wresting market share from the incumbents, Markides says. —Andy O'Connell

HabitsWhy You Can't Stop Checking Your PhoneBoston Globe

Forming habits is one of the ways we become more productive. Essentially, our brains create shortcuts when it comes to things we do often, like turning off the lights, thereby saving our mental bandwidth for times when we need to make an important decision. This is all well and good, explains Leon Neyfakh, except when it comes to checking your phone while you drive.

With distracted driving, which injured 387,000 people and killed 3,331 more in 2011, the impulse has been to increase public awareness (filmmaker Werner Herzog directed this 30-minute stunner of a campaign, for example). But that approach may not work. Your phone programs your brain to habitually check it. And when checking text messages or Twitter becomes a neurological shortcut, we may not even be aware we're picking up our phones, particularly because the act of driving preoccupies our prefrontal cortex, which controls inhibition. So how do we make ourselves, and others, safer? Some suggest social campaigns to make checking phones in certain situations socially taboo. Or we can fight habit with habit, teaching our brains that there are times when we should turn our phones off.

Rashomon in Silicon Valley All Is Fair in Love and TwitterNew York Times Magazine

Hope you like start-up soap operas. In this downright juicy excerpt from Nick Bilton's forthcoming book Hatching Twitter, we finally get to the bottom of the social network's origin story. And it ain't what developer and self-proclaimed Twitter inventor Jack Dorsey has peddled all these years (among other things, he supposedly invented Twitter on a playground, or when he was 8 years old, or because he was fascinated with trains and maps).

There are far, far too many wonderful details to squeeze in here (like the time Ev Williams told Dorsey, “You can either be a dressmaker or the CEO of Twitter," but not both, or when Dorsey insisted that employees use Twitter rather than text messages, which resulted in a six-figure monthly bill). But the most resonant aspect of the piece is that after Dorsey was essentially forced out as CEO, he spun his own origin story, portraying himself as the heart and soul of Twitter in order to maneuver his way back to the top of a company he once struggled to run. In the end, Bilton reminds us that the creation of Twitter was truly a collaborative effort. Some people are making a ton of money because of it. Others, like Noah Glass (heard of him?), the man who actually came up with the name "Twitter," aren't.

Self-Absorbed with an Open Wallet? The Millennial Male Is Not Who You Think He Is Adweek

Traditionally, American men between the ages of 18 and 34 have been a lucrative target for marketers. But, says Sam Theilman at Adweek, the recession and lingering underemployment have made the millennial generation a very different breed of youth from their counterparts of old. Collectively, millennials carry an eye-popping $1 trillion in student loans, even though only a quarter of the males among them managed to get a degree. Just 62% of millennial men have jobs; half of those work less than full time. And they’re not being paid much for their efforts. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the gap between productivity and real hourly compensation has never been wider, which means they’re doing a lot more work for a lot less money.

The upshot: Millennials are poor, which is making them very frugal consumers. New cars are beyond them, and even cable is too expensive. More than a third still live with their parents. Unless the economy starts generating better-paying jobs, they’re unlikely ever to turn into the kind of consumers the Baby Boomers and Gen Xers were at their age. —Andrea Ovans

BONUS BITSWhen Things Go Badly

Why It's So Hard for Companies to Make Digital Transformations (Sloan Management Review)

Blackberry, Disruption, and Woulda, Coulda, Shoulda (Learning by Shipping)

The U.S. Debt Ceiling Crisis Explained (The Guardian)

Overcoming Fragmentation in Health Care

America is a nation of innovators and entrepreneurs. We are a nation that cares for our fellow citizens, yet we have failed to create a health care system that fully meets the needs of people in this country. Health care is fragmented, and the quality of care varies widely, which leads to unsustainable health care spending.

As the Affordable Care Act (ACA) continues to be implemented, we are seeing increased access to insurance coverage for many. But the ACA does little to address fragmentation, quality of care, and the sustainability of the financial model for U.S. health care — how health care is paid for. More work is needed to achieve the drastic change in market forces that is necessary to create a sustainable health care system. To achieve this, we must reduce fragmentation of care, ensure that the highest quality care is delivered in all settings, and build a sustainable health-care financial model.

Addressing Fragmentation

Health care is experiencing a significant trend of consolidation through mergers and acquisitions. At Mayo Clinic, we have chosen a different path — a path focused on sharing our most scalable product: our knowledge. We believe that fragmentation and variability in care may best be addressed by creating tools to share knowledge than can be used by providers as they care for patients in their own communities.

At the foundation of our approach is a knowledge-management system — an electronic archive of Mayo Clinic-vetted knowledge containing evidence-based protocols, order sets, alerts and care process models. This system, which can be made available to physicians in any location, brings safer care, better outcomes, fewer redundancies, and ultimately cost savings for our patients. Ask Mayo Expert, one of the many tools in our system, helps physicians deliver safe, integrated, high-quality care. Through this system, physicians can find answers to clinical questions, connect with Mayo experts, search national guidelines and resources, and find relevant educational materials for patients. This knowledge is updated in real time and made widely available.

We have used this knowledge-management system to support the creation of our Mayo Clinic Care Network, an affiliation model rather than a merger or acquisition model. This tool supports health care professionals in their communities, enabling them to provide better care locally at lower cost. This network has been built over two years and includes 21 health systems and hospitals in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Mexico — all of which use Mayo Clinic-vetted knowledge so that other patients can benefit from our 150-year history of innovating and improving patient-centered care.

Addressing Uneven Quality

The proliferation of mandated quality measures and programs is daunting and some would argue has done little to improve quality and transparency for health care consumers. Quality in health care must be based on a comprehensive look at the entirety of a patient’s experience. It is alarming to see more than a two-fold variation in health care quality across the country. Streamlining quality of care can be difficult, which is why we’ve incorporated the use of engineering principles to improve our quality outcomes, safety, and service. We purposefully design, implement, and systematically diffuse quality-improvement efforts at all of our locations around the country. Through this commitment, Mayo Clinic physicians and scientists have contributed more than 400 peer-reviewed papers on quality improvement in the last five years.

The promise of the emerging science of health care delivery is profound, some say game-changing, in its ability to both reduce costs and improve quality. The full potential will be realized through the distribution of the right tools and resources. One such resource is the work of Optum Labs, which we formed with Optum earlier this year. Optum Labs, an open R&D facility with a unique set of clinical and claims data, is being used to drive advances that will improve health care for patients and our country. We are now inviting others — providers, life science companies, research institutions, consumer organizations, and policy makers — to be part of Optum Labs. This opportunity to apply world-class analytical tools to both cost and quality will provide the evidence necessary to deliver care that reduces costs and increases quality at the same time. This effort will allow health care to finally measure value for patients and payers.

Creating a Sustainable Future

Investment in health care is critical at this time. At Mayo Clinic we are investing in new areas of research that will define the future of health care, such as individualized medicine and regenerative medicine. We are also intentionally investing in our most precious resource: our staff. We constantly strive to have the most talented health care workforce anywhere in the country and are investing in their growth and knowledge expansion. For example, we have initiated team-based methods to enhance learning about new regenerative-medicine therapies that help us tailor diagnostics and hold promise to teach the body to heal itself from within. We use the same team-based learning approach to drive ongoing improvement in the quality of care through the discipline of the science of health care delivery.

Just as the private sector must continue to fund research, the same is true for government. Funding for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies is essential for the health of Americans and the economic vitality of our country. Recent reductions in research funding put our nation’s competitiveness, economic security, and future at risk.

We also must embrace the elusive goal of value — higher quality of care at lower cost. We need a payment system that recognizes the spectrum of health care delivery across primary, intermediate, and complex care while rewarding the quality and value of each. This includes all payers — both private insurance and government-funded programs, particularly Medicare. The sustainable growth rate should be replaced with new, negotiated payment models that tie reimbursement to quality outcomes across the spectrum of care.

To transform health care in America into high-quality, patient-centered care that the nation can afford, we must address fragmentation, we must address variable quality, and we need to create a sustainable health-care financial model. Collaboration is key. Mayo Clinic has a long history of innovation focused on improving the value of health care, but we can accomplish much more by working together — integrating and sharing knowledge with one another.

Together, we must create the future of health care, a sustainable future that Americans expect and deserve.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

Why Less Choice Is More in Health Insurance Exchanges

Doubts About Pay for Performance in Health Care

Coaching Physicians to Become Leaders

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers