Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1533

October 15, 2013

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the November 2013 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the November issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Cartoon Caption Contest at the bottom of this post. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in next month’s magazine and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

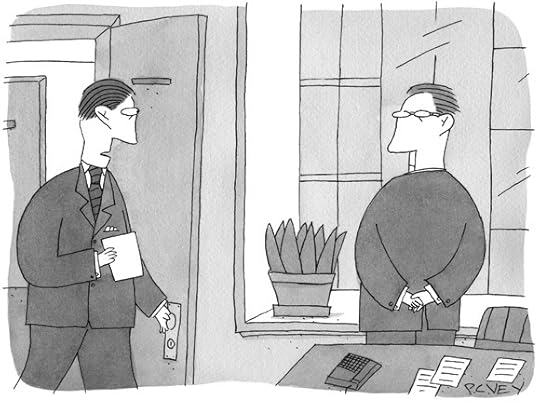

“I have the preliminary report on interesting things to look for in the building across the street.”

PC Vey

“I’d like to start out as CEO and then settle into a lower position once my student loans are paid off.”

Randy Glasbergen

“This had better be good.”

Paul Wood

“It’s always sad when senior management beaches itself.”

Michael Shaw

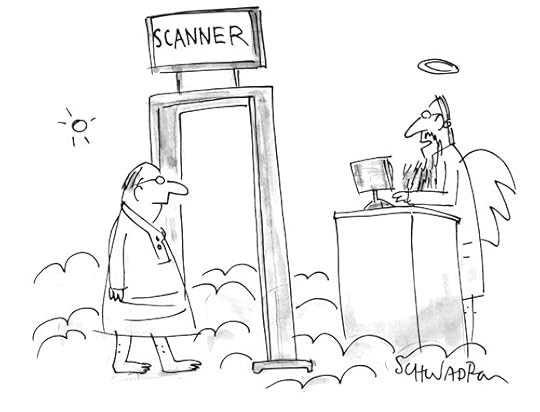

“We just need to make sure you didn’t take it with you.”

Harley Schwadron

“What’s the advancement program here other than waiting for someone to die?”

Bob Vojtko

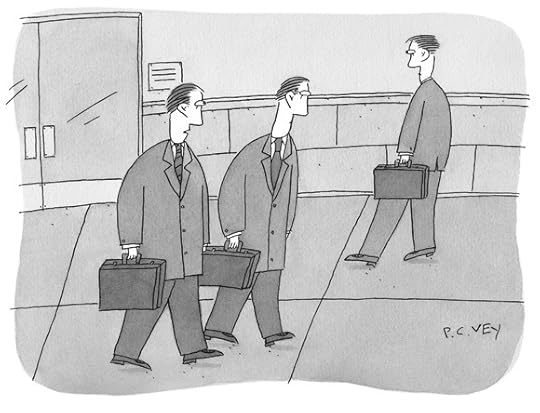

“My media strategy has always been to go home and watch TV.”

PC Vey

And congratulations to our October caption contest winner, Eugene Evon of Novato, California. Here’s his winning caption:

“IT really failed us with these new keyboards.”

Cartoonist: Paul Kales

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your own caption for this cartoon in the comments field below — you could be featured in next month’s magazine and win a free book. To be considered for the prize, please submit your caption by Monday, October 21, 2013.

Cartoonist: Susan Camilleri Konar

The Three Decisions You Need to Own

CEOs face countless decisions. The best executives understand which ones they need to focus on and which ones they can delegate. While the obvious decisions that CEOs need to get right involve strategy and competitive advantage, too many executives delegate away three critical decisions that they need to own: decisions about goals, resource allocation, and people.

Goal setting: As a rule, CEOs don’t give enough attention to setting goals. The greatest mistake they make is to look in the rearview mirror at what they did last year or at what their competition did. The brilliant decision-makers look at the runway ahead.

Resource allocation: These decisions are big because some competitive moves need disproportionate resources. When resources are allocated from the bottom up instead of from the top down, they get out of sync with what the senior team is trying to accomplish. At many companies the total cash investment in acquisitions, R&D, and fixed assets has not earned back its cost of capital after adjusting for the time lag in realizing incremental benefits. That outcome reflects the wrong allocation and/or ineffective execution. Some activist shareholders are finding gaps in CEO performance by doing this calculation.

People and Organization: In late 2010, GE CEO Jeff Immelt decided to give country managers P&L responsibility for all of GE in their countries and have them report to vice chairman John Rice, who would be stationed in Hong Kong. It was the first time a vice chair would be based in an emerging market. It reflected the reality that a lot of GE’s growth will be coming from the developing world, and the leaders have to be there. As Keith Sherin, then GE’s CFO put it, “This is where the growth is. We are shifting our center of gravity.” Such decisions might be unpopular and break a lot of traditions, yet they set the future course of the company. Decisions to displace people are even tougher, yet when I studied 82 CEOs who failed, I saw that the most common reason for failure was putting the wrong person in a job and then not dealing with the mismatch. Most of the time CEOs know in their gut when someone is not fit for the job, but they don’t do anything about it. It’s hard to admit the error, or they have a psychological bond with the person or think they can coach him or her. Sometimes it’s a matter of misjudging performance because they don’t dig into the causes. Today most if not all industries are impacted by digitization—mobile technology, big data, and the like. It has a tremendous effect on which people are more critical than others.

One CEO of a large Indian company has been bringing a lot of younger people into senior jobs because of their digital experience. It’s been hard for him to bypass some long-serving executives, but he had the spine to make those decisions. Great decision-makers stay on top of these three areas, because these are the three areas that have the most impact on whether or not your strategy will be executed. Don’t delegate them away. This article is adapted from the HBR interview with Ram Charan, You Can’t Be a Wimp, Make the Tough Calls found in the November 2013 issue of HBR.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Don’t Make Decisions, Orchestrate Them

How to Minimize Your Biases When Making Decisions

How P&G Presents Data to Decision Makers

Three Keys to (Much) Better Decisions

India’s Secret to Low-Cost Health Care

A renowned Indian heart surgeon is currently building a 2,000-bed, internationally accredited “health city” in the Cayman Islands, a short flight from the U.S. Its services will include tertiary care procedures, such as open-heart surgery, angioplasty, knee or hip replacement, and neurosurgery for about 40% of U.S. prices. Patients will have the option of recuperating for a week or two in the Caymans before returning to the U.S.

At a time when health care costs in the United States threaten to bankrupt the federal government, U.S. hospitals would do well to take a leaf or two from the book of Indian doctors and hospitals that are treating problems of the eye, heart, and kidney all the way to maternity care, orthopedics, and cancer for less than 5% to 10% of U.S. costs by using practices commonly associated with mass production and lean production.

The nine Indian hospitals we studied are not cheap because their care is shoddy; in fact, most of them are accredited by the U.S.-based Joint Commission International or its Indian equivalent, the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals. Where available, data show that their medical outcomes are as good as or better than the average U.S. hospital.

The ultra-low-cost position of Indian hospitals may not seem surprising — after all, wages in India are significantly lower than in the U.S. However, the health care available in Indian hospitals is cheaper even when you adjust for wages: For example, even if Indian heart hospitals paid their doctors and staff U.S.-level salaries, their costs of open-heart surgery would still be one-fifth of those in the U.S.

When it comes to innovations in health care delivery, these Indian hospitals have surpassed the efforts of other top institutions around the world, as we discussed in our recent HBR article. Today, the U.S. spends $8,000 per capita on health care; if it adopted the practices of the Indian hospitals, the same results might be achievable for a whole lot less, saving the country hundreds of billions of dollars.

A key to this is that, faced with the constraints of extreme poverty and a severe shortage of resources, these Indian hospitals have had to operate more nimbly and creatively to serve the vast number of poor people in need of medical care in the subcontinent. And because Indians on average bear 60% to 70% of health care costs out of pocket, they must deliver value. Consequently, value-based competition is not a pipe dream but a reality in India.

Three major practices have allowed these Indian hospitals to cut costs while still improving their quality of care.

A Hub-and-Spoke Design

In order to reach the masses of people in need of care, Indian hospitals create hubs in major metro areas and open smaller clinics in more rural areas which feed patients to the main hospital, similar to the way that regional air routes feed passengers into major airline hubs.

This tightly coordinated web cuts costs by concentrating the most expensive equipment and expertise in the hub, rather than duplicating it in every village. It also creates specialists at the hubs who, while performing high volumes of focused procedures, develop the skills that will improve quality. By contrast, hospitals in the U.S. are spread out and uncoordinated, duplicating care in many places without high enough volume in any of them to provide the critical mass to make the procedures affordable. Similarly, an MRI machine might be used four to five times a day in the U.S. but 15 to 20 times a day in the Indian hospitals. As one CEO told us, “We have to make the equipment sweat!”

U.S. hospitals have been developing similar structures, but there are still too many hubs and not enough spokes. Moreover, when hospitals consolidate, the motive often is to increase market power vis-à-vis insurance companies, rather than to lower costs by creating a hub-and-spoke structure.

Task Shifting

The Indian hospitals transfer responsibility for routine tasks to lower-skilled workers, leaving expert doctors to handle only the most complicated procedures. Again, necessity is the mother of invention; since India is dealing with a chronic shortage of highly skilled doctors, hospitals have had to maximize the duties they perform. By focusing only on the most technical part of an operation, doctors at these hospitals have become incredibly productive — for example, performing up to five or six surgeries per hour instead of the one to two surgeries common in the U.S.

This innovation has also reduced costs. After shifting tasks from doctors to nurse practitioners and nurses, several hospitals have even created a lower tier of paramedic workers with two years’ training after high school to perform the most routine medical jobs. In one hospital, these workers comprise more than half of the workforce. Compare that to the U.S. system, where the first cost-cutting move is often to lay off support staff, shifting more mundane tasks such as billing and transcription onto doctors overqualified for those duties — precisely the wrong kind of task shifting.

Good, Old-Fashioned Frugality

There is a lot of waste in U.S. hospitals. You walk into a hospital in the U.S., and it looks like a five-star resort; half of the building has no relation to medical outcomes, and doctors are blissfully unaware of costs. By contrast, Indian hospitals are fanatical about wisely shepherding resources — for example, sterilizing and safely reusing many surgical products that are routinely discarded in the states after a single use. They have also developed local devices such as stents or intraocular lenses that cost one-tenth the price of imported devices.

These hospitals have also been innovative in compensating doctors. Instead of the fee-for-service model, which creates an incentive to perform unnecessary procedures and tests, doctors at some Indian hospitals are paid fixed salaries, regardless of how many tests they order. Other hospitals employ team-based compensation, which generates peer pressure to avoid unnecessary tests and procedures.

Innovation has flourished in the U.S. in the development of new pills, clinical procedures, devices, and medical equipment, but in the field of health care delivery, it appears to have been frozen in time. In too much of the U.S., system, health care is viewed as a craft and each patient as unique. But by applying principles of mass production and lean production to health care delivery, Indian doctors and hospitals may have discovered the best way to cut costs while still delivering high quality in health care.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

Intelligent Redesign of Health Care

Why Less Choice Is More in Health Insurance Exchanges

Doubts About Pay for Performance in Health Care

The Power of Restraint: Always Leave Them Wanting More

The setting: the spectacular office of one of the most respected names in entertainment, a senior executive in the motion picture industry. The players: the executive, accompanied by his bevy of direct reports and support staff, plus a CEO friend of mine and his chairman (we’ll call him Mr. Chairman).

The meeting was unusual in its purpose. Mr. Chairman, who does not come from the entertainment industry, wanted to share his epiphany on how movie-makers should rethink the categorization of movie genres. His hypothesis was that movies should not be called romantic, horror, thriller, etc., but instead use a schema inspired by psychologist Abraham Maslow’s famous “hierarchy of needs” that might better explain and predict which movies are likely to succeed.

After the regular pleasantries, Mr. Chairman, a soft-spoken and even-keeled individual, began sharing his new taxonomy for the movie industry, scrawling some sketches along the way. The meeting moved along quickly and positively. Within minutes, curiosity was piqued, and by the 10-minute mark the entertainment mogul and his entourage were engrossed. After about 20 minutes, they seemed enthralled, having embraced several of “wow moments” described by Mr. Chairman.

Precisely at this high point of excitement, around the 25-minute mark of the meeting, Mr. Chairman glanced at his watch and announced that he had already taken a meaningful amount of their time and should leave now. He asked them to follow up if any of his thoughts stuck. With some bewilderment goodbyes were said, and that was it — meeting done and wrapped up in just under 30 minutes.

But, of course, a long-term relationship ensued.

For my CEO friend it was a career life lesson: “Leave them wanting more.” But this was not a Machiavellian strategy born out of a premeditated plan. It was the natural product of Mr. Chairman’s innate leadership, humility, patience, emotional intelligence, and introverted disposition. With those qualities come self control, and an instinct for when to apply restraint.

There’s a common misperception that extroverts are the best leaders and sales people. Adam Grant at the Wharton School has conducted studies showing that “ambiverts” (people who are a mixture of extrovert and introvert) are actually the most effective in sales, followed by introverts and then extroverts. In a three-month study of 300 sales people, ambiverts generated 32% more revenue than extroverts, and 24% more than introverts.

It is not that extroverted behavior is bad, but rather that when it’s not leavened with restraint and listening, it can be limiting. Most extroverts would have loved exciting an audience as Mr. Chairman did — and likely would have had trouble ending the meeting as he did, instead over-selling to the point of diminishing returns.

The power of restraint is a lesson that cuts across all aspects of our lives. It is a lesson that I have tried to internalize after writing a book and now numerous blog posts with editors exceptional at, yes, editing. It is not just about grammatical correctness or even structure, but a centrifugal type of editing that teaches the discipline of choice, and restrains one from making the mistake of over-telling, over-selling.

In business, we don’t edit enough. Any list of three top priorities invariably includes an “a,b, and c” below each one — which really means a list of nine. It is always a challenge to maintain focus on what truly matters — “the big rocks in the jar” as Stephen Covey would often say. Covey talked of filling a jar that represents life. You need to start with bigger rocks (the largest priorities, such as family and health) before you put in the medium size rocks, smaller pebbles, sand, and water. If you go in that order, everything fits in the jar. Going the other way does not work (just try it), and crowds out the things that really matter.

To practice more restraint, to stay focused on the things that really matter, consider the following:

Start with self-awareness. Susan Cain, author of the book Quiet , has a simple online “quiet quiz” to let you know if you lean toward introversion or extroversion.

Delegate, don’t command and control. Effective managers and leaders understand how to motivate with just enough direction to get multiplier-force leverage, because people feel a true sense of ownership. Micromanagement is a symptom of an inability to delegate and of letting your desire to do overwhelm your need to lead.

Sell with more judo and less karate. This is an analogy I use often to stress, similar to the delegation point above, the important of allowing people to come to their own conclusions and using that to create intrinsic motivation to get the task done.

Quality over quantity of voice. We all know the rare type of individual who does not talk often, but when she does, everyone listens. There is tremendous power in increasing one’s listen-to-talk ratio and then choosing the right moments for expression. Quality of comment usually matters more than the quantity of comments.

Leave them wanting more. This was the key lesson from Mr. Chairman. When you lead a meeting, ask yourself each time it ends if you left people wanting more. Consider cutting — at least mentally — your meeting time by at 20-30% to make sure you focus on the right things first, and to understand that your goal may be to have them wish for more time, or even another meeting.

Ultimately Mies van der Rohe’s got it right. His “less is more” maxim extends beyond architecture to a principle we should use much more in business practice.

Are You on the Red Team or the Blue Team?

Among male participants in a competition experiment, those who chose to represent themselves with red trapezoidal symbols on a scoreboard proved to have blood-testosterone levels that were about 10% higher than those who chose blue trapezoidal symbols, says a team led by Daniel Farrelly of the University of Sunderland in the UK. Those who chose red didn’t perform any better on the competitive task, however. It’s unclear whether the color choices were the result of learned or innate associations, the researchers say.

Can You Invent Something New If Your Words Are Old?

Is “Orange Is the New Black” or “House of Cards” a TV show? We can watch them on our smartphone, tablet, computer or TV. And, unlike traditional TV shows, which are released an episode per week, we can watch the whole season at once, totally disrupting the sense of time the television channels have taught us to expect. And yet, as Kevin Spacey recently pointed out at the Edinburgh International Television Festival, we still talk about that form of media in terms of its traditional viewing source. It’s still a TV show, even if it’s more like an episodically-punctuated-video-feed.

Many of our words are archaic, not just “TV show.” How many of us still say, “Will you tape that show for me?” when no tape is involved. We talk about albums, records, and filming. We “dial” and “hang up” the phone. At the tollbooth, we “roll down the window” even though we’re not rolling anything. We refer to a child as a “carbon copy” of her dad. Even our icons are out of date. You click a magnifying glass to search. (Perhaps Sherlock Holmes, somewhere, approves.) You click a floppy disc to save. (Do your kids even know what that is?) Your mail icon is an envelope. (Too bad for the post office that you don’t need a stamp.)

The words and images we use to describe things affect our thinking. What if the words we use are limiting the solutions we can create?

What if instead of being asked to create a “TV show”, we were asked to create a story using video? Would it open our mind to more options than broadcast or cable TV? A YouTube channel? Vine or Instagram videos? Something entirely different? What if, when you need a package for your new product, instead of thinking of a package as a separate container to be discarded, it was part of the product itself in some way? Would it still be a package? Would it still need to be thrown out? At a much simpler level, will the solution change if we change our words from “satisfying customer needs” to “delighting customers”? What if we “thrill our customers with easy service” instead of “making it easy to talk to customer service”? Just by using different language, we can find more ways to be innovative in how we approach problems and opportunities.

Language is paradoxical. In some ways, it doesn’t keep pace with the rate of societal and technological change (e.g., TV show, carbon copy) and in others, new words are created almost daily in response to our fast-changing world (e.g., selfie, MOOC). There is a balance between using the past to understand the present and guide the future, on the one hand, and on the other, creating something fresh that leaves the old behind. We need analogies to understand the new (eg, horseless carriage) yet they also hold us back by it constraining our thinking (eg, horseless carriage).

So I have a challenge for you. Watch your language and the language of those around you. See what words you are using and how you’re using them. Do they help you and your organization move forward? View the world differently? Open your mind to new possibilities? Or do they constrain how you view the world?

And when you change the words, does the world change as well?

October 14, 2013

What the Great Fama-Shiller Debate Has Taught Us

It’s a little hard to imagine a Nobel Prize in physics being shared by (1) a guy famous for advancing a particular hypothesis and (2) a guy famous for relentlessly attacking that hypothesis. This of course is what the Nobel committee has done with this year’s economics award, with the added Hegelian twist of giving another third of the prize to a guy who came out somewhere in between. Thesis (Gene Fama)! Antithesis (Bob Shiller)! Synthesis (Lars Peter Hansen)!

This is, to a certain extent, further evidence that economics isn’t a science like physics is a science (and yeah, yeah, the economics Nobel isn’t a real Nobel prize). But that’s not because economists are all frauds — it’s at least partly because economics is harder than physics. And the interaction over the decades between the differing ideas of Fama and Shiller, while maybe not exactly scientific, has certainly been enlightening, and had a huge impact on the world.

Like a lot of people, I know much more about Fama and Shiller than about Hansen. That’s partly because Fama and Shiller have been willing (downright eager, in Shiller’s case) to explain their work to the public, while Hansen apparently prefers to sit in his office and do math. It’s also because Fama and Shiller are the obvious poles of the debate, while Hansen is one of a number of people who have been plowing the extensive acreage between them. I think he got the Nobel nod (instead of somebody like Andy Lo, or Mordechai Kurz, or Roman Frydman) because he was (1) very early to the game, (2) a macroeconomist (the Nobel people generally seem more comfortable with macro than with finance), and (3) most suited to being shoehorned into a narrative of steady scientific progress. It’s also possible that Hansen just got the prize because his work is so great and/or has spawned lots of productive further research, but I’m really in not in a position to judge that — his stuff is really dense. So I’m not going to pretend that I know much about his contributions; you need to go elsewhere for that.

Fama and Shiller, though, are people I spent years thinking about, reading about, and talking to for a book I wrote a few years ago. I could go on about them forever, but here’s the very short version of why they’re important:

Fama studied finance at the University of Chicago’s business school in the early 1960s, then started teaching it there. This was a time of great ferment in financial research at Chicago and a few other campuses, occasioned by the arrival of a few new ideas and a few more big computers. At the annual meeting of the American Finance Association in 1969, Fama presented a paper (published the next year in the Journal of Finance) summing up what he and others had learned about stock market behavior over the previous decade and sketching out a way forward. “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work” laid out the evidence that stock market prices were hard to predict using past price behavior (that is, they followed a “random walk”) and even information about corporate performance, and that professional investors generally failed to beat the market. He suggested taking things a step further, and testing whether the stock market was actually “efficient” in the sense that it “provide[d] accurate signals for resource allocation.”

The way to test this, Fama said, was in conjunction with a theory of “market equilibrium under uncertainty.” The main model available at the time was the Capital Asset Pricing Model, which says that a stock’s returns over time should be commensurate with its riskiness in relation to the overall market. Early tests of CAPM came out reasonably well, and by the end of the 1970s Fama’s former student Michael Jensen was (in)famously declaring that “I believe there is no other proposition in economics which has more solid empirical evidence supporting it than the Efficient Market Hypothesis.”

Research into stock market prices had also been popular at MIT in the 1960s, and MIT’s Paul Samuelson even authored the first paper mathematically demonstrating that a rational stock market would be a random, unpredictable one. But Samuelson never believed that real-world markets approached this ideal, and MITers were critical of the hardening Chicago conviction that they did. Shiller, who got his Ph.D. from MIT in 1972, devised his own test of market efficiency, asking in a paper published in the American Economic Review in 1981, “Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends?” His answer: Why yes they do!

Shiller’s paper was hugely controversial at the time, and if you bring it up with old-guard finance professors they still tend to grumble about it. Perhaps his claim that the Efficient Market Hypothesis was “one of the most remarkable errors in the history of economic thought” had something to do with that. But within a few years — especially after the market crash of 1987 — it was widely accepted that yes, stock prices did appear to be much more volatile than the economic and corporate fundamentals that they were supposedly reflecting and predicting. For a time most finance scholars still argued that it was impossible to say until after the fact when exactly market prices were out of line, but the tech stock bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s changed a lot of minds about that.

It didn’t change Fama’s mind. He still contends that those who speak of market “bubbles” are being intellectually sloppy. But his students have with his encouragement documented lots of apparent market inefficiencies, and his own empirical work has done as much damage to the EMH as he proposed it in 1969 as Shiller’s has. In a study published in the Journal of Finance in 1992, Fama and co-author Kenneth French found that, contrary to earlier evidence, the Capital Asset Pricing Model didn’t do a very good job at all of explaining stock market returns in the U.S. from 1941 through 1990. Fama and French chose to try to save EMH by jettisoning CAPM and replacing it with their own multi-factor risk model in which the small-stock effect and the value stock effect are said to “explain” price behavior (others have since added other factors). But it’s just as valid to hold on to CAPM and label these effects market inefficiencies. As CAPM loyalist Fischer Black of complained of Fama and French in 1993: “They don’t want to hear about theory, especially theories suggesting certain factors or securities are mispriced.” But Fama had framed his hypothesis in a way that it could be tested, and has been pretty relentless about testing it. You can applaud that without embracing his conclusions.

Meanwhile, Shiller, for all his criticisms of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, still seems to endorse a very loose version of it. He has shown that asset prices have a tendency to overshoot, but he’s nonetheless generally a big believer in financial markets, frequently arguing that what we need are more markets and more ways to hedge our risks. His extracurricular activities, from his books to the Case-Shiller real estate price indices he co-created, are best seen as attempts to educate market participants and get them to do a better job of setting prices.

Fama’s main work outside of academia has involved advising the big small-stock index-investing firm Dimensional Fund Advisors, founded by his former students David Booth — after whom the Chicago business school was renamed in 2008 after he gave it $300 million — and Rex Sinquefield. His research also played a big role in the creation and rise of the index investing industry in general. And his most important and consistent message through the years, that it’s really hard to beat the market, remains really good advice.

So I’ll admit that it’s an odd combination of Nobel Prize recipients. But it’s not necessarily an incorrect one.

Always, Always, Always Show Up

Three years ago, as I was putting the finishing touches on my book Dare, Dream, Do, a friend sent me a link to a contest sponsored by Oprah. The prize was your own talk show. Immediately, I was thrilled by the giddy fear I feel when I know I’ve got to take something on.

Almost simultaneously, I began to explain to myself why this audition was a no-go: I would have to take a day off of work, drive from Boston to New Jersey, fill out a lengthy application, get up long before dawn to be one of the first 500 people in line, and subject myself to the humiliation of a cattle call in a Kohl’s parking lot. As I told all of this to my friend Liz, she gently observed, “I find it ironic that you are writing a book daring people to dream, but you won’t.”

That was all I needed. I pride myself on not giving up. So I went. As you may have surmised, I didn’t win my own talk show. I didn’t even make it past the first cut. After all the work of getting to the audition, waking up early, thinking about what I was going to say, and carefully selecting my most Oprah-worthy outfit (!), I stumbled. While I gave my elevator pitch, my nervousness made me note-dependent, my affect flat, and my voice monotone: there was nothing about my thirty seconds that would inspire people to dream and disrupt. Afterward I was deflated. Disappointed. I’d suited up and shown up (at 3 o’clock in the morning, no less) to my dream, but some small part of me held back. I made myself go, but I didn’t pour my whole soul into it. I hadn’t given up, but I hadn’t really shown up, either.

I’ve always repeated the mantra “never, never, never, never give up.” These words of Winston Churchill’s have rallied me for years; they are a core tenet of our family motto, and hang, framed, on the wall just inside the front door of our home. But I’ve started to wonder if not giving up is sufficient. Of course persistence is essential. But I wonder if the pluck of true grit embodied by the words “never give up” has morphed into a euphemism for something more fatalistic: I won’t give up… but I’m still sort of waiting to get picked by life’s lottery.

Last year, for example, I was approached about a senior management role at a fast-growing Boston start-up, but ultimately they didn’t offer me the job. There are likely a variety of reasons why things didn’t work out, but I have since learned that my not “showing up” was a contributing factor. There was nothing in my behavior that would indicate that I passionately wanted in. As with my Oprah audition, I’d really, really wanted it – so much that my instinct was to hide just how much.

Jules Pieri, who was recently named one of 2013’s Most Powerful Woman Entrepreneurs by Fortune Magazine, is a woman who is now reaping the rewards of standing up. Pieri is the Co-founder and CEO of The Grommet, a retail site devoted to promoting innovative, undiscovered products and the stories behind their makers. In 2012, Japanese e-commerce giant Rakuten invested in The Grommet and the company has been soaring ever since. But her path has not been scattered with rose petals – for years the site survived on a slender budget, living from one desperately needed cash-infusion to the next when no VCs would invest major capital during the 2008-9 recession. Pieri made many personal sacrifices to keep her dream alive: she did not take a vacation for three years, she was unable to regularly visit her mother in Detroit who was battling cancer, and her son had to get emergency financial aid to stay in college. Jules never gave up—but she also fully showed up, day after day.

A look at some of the research has convinced me that maybe Woody Allen was right, and 80% of success really is just showing up. According to Keith Simonton, professor of psychology at UC Davis, the odds of a scientist writing a groundbreaking paper (defined as the number of citations in other works) is directly correlated to the number of papers that the scientist has written — not to how smart the scientist is.

Rob Wiltbank, professor of strategic management at Willamette University, tracked the returns of the Angel Oregon Fund and found no material difference in the returns of the winners and the finalists in various pitch competitions over a 10-year period.

We all dream about winning, but it’s the showing up that counts.

Even though we can’t necessarily control the outcome. Sarah Ban Breathnach said, “When you use expectations to measure a dream’s success, you tie stones around your soul. Dreams may call for a leap of faith, but they set the soul soaring.” There are no regrets when we invest ourselves fully and show up to ourselves. Happily, we get lots of chances.

I’ve recently had one of those chances. Another opportunity has come up that I’m well qualified for, and I recently learned that I made the short-list, largely because I raised my hand and said, “I want this.”

Dreaming is at the heart of disruption. Whether we want to disrupt an industry or our personal status quo, in order to make that terrifying leap from one learning curve to the next, we must dream. The good news is that the causal mechanism for achieving our dreams is always, always, always showing up: and as we show up, our future will too.

Intelligent Redesign of Health Care

The health care industry has survived economically by cross-subsidizing margin shortfalls in one activity with the revenues generated from others. But the very existence of these cross-subsidies is symptomatic of deep flaws in the health care reimbursement system. As we move forward we need to be mindful of two principles that must be at the heart of any fundamental health care reform: “no margin, no mission” and “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” As the era of health care cross-subsidization ends, these principles must guide our actions.

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is seeking to reduce its cost structure by redesigning its health-care-delivery model to reflect the true costs of care (the early stages of the project were described in a 2011 Harvard Business Review article by Robert S. Kaplan and Michael E. Porter). To obtain an understanding of the costs, the center is applying a combination of two management tools: process mapping from industrial engineering and activity-based costing from accounting. Specifically, the center wants estimates of:

The costs of caring for groups of patients with similar conditions

The actionable cost savings from process improvement

The benefits from better utilization of capacity

The center will then tie the cost to patient-outcome measures, which will enable it to design a system that improves the quality of outcomes, motivates efficiency and improved capacity utilization, reduces costs, and assures patients and providers that any cost improvements will not reduce the quality of care delivered. The belief is that this kind of intelligent redesign will be less dangerous for patients than the across-the-board cuts of line-item expenses mandated by government and administrative entities.

The project requires clinicians to learn process mapping and cost-accounting tools that are not taught in medical school or residency. Intelligent redesign starts, therefore, with teams of clinicians and business analysts working side by side to examine processes of care.

The first step in the assessment of a health-care-delivery model involves a step-by-step mapping of each event in a patient’s complete care cycle. A high-level example of the output of this exercise is shown in the exhibit “New Head and Neck Patient Registration at the MD Anderson Cancer Center.”

For costing purposes, the maps must identify who performs each step and estimate the time spent by each resource (person or piece of equipment) at that step. Due to the unique circumstances of individual patients, the map includes decision nodes, which allow alternative care paths to be followed when appropriate for the patient’s specific circumstances. Each colored box in the exhibit represents a different category of health care provider. Circles indicate the time estimates for each step in the process. Diamond-shaped boxes represent steps that may or may not be needed in a process, depending on patient characteristics, and the probability estimates of the next step is indicated in the adjacent percentages.

Project team members with finance expertise contribute by supplying the cost rate for each person and equipment involved in the care processes. The direct costs of supplies and drugs are added to each process and finance team members again contribute by accurately assigning support costs that formerly were allocated arbitrarily as so-called “overhead costs.” The sum of all these elements represents the cost of each care process.

The new approach produces accurate, detailed, and transparent costs for each care process as well as the cost of all the unused capacity in the system. The results are often surprising; for example in the pilot project described in Kaplan’s and Porter’s 2011 HBR article, one finding was that most providers’ existing cost systems underestimate the cost of new patient evaluation services by 15% to 20%. And by tracing costs accurately to care processes, any improvements in a process can be easily translated into actual cost reductions. Among the improvements identified in the pilot were:

A process change in anesthesia assessments producing a cost reduction from about $250/case to $160/case, without adversely affecting any outcome;

Redeployment and realignment of personnel allowing for a 16% decrease in staff in the center

A 19% increase in the number of patients seen

Rather than forcing a trade-off between mission and margin, process-improvement opportunities identified through this kind of analysis usually enable the provider to reduce costs while simultaneously improving clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction through reduced wait times and more timely, higher-quality medical care.

These projects do, however, require institutional commitment because mapping clinical and administrative processes and tying each process to its resource costs are not currently part of routine business operations. Physicians, therefore, need to take the lead in unlocking the tremendous potential in these tools by collaborating with administration, finance, and performance-improvement teams to control costs, improve quality, and eliminate the waste and excess capacity we all acknowledge exists in our health care system.

Once we stop cross-subsidizing health care delivery, we can build a reimbursement system that is accurate, transparent, and a stimulus for continuous improvements. A value-based system that is based on knowledge of the efficient processes and costs incurred over an entire cycle of care will enable health care organizations to negotiate a fair price for care and be rewarded for delivering higher quality care at a lower cost.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

Why Less Choice Is More in Health Insurance Exchanges

Doubts About Pay for Performance in Health Care

Coaching Physicians to Become Leaders

Emerging Market Firms Need a Diaspora Strategy

Emerging market diaspora populations have been on the rise, thanks to the continued march of globalization, and today’s diaspora communities are better connected with their homelands than ever before. That’s due both due to increasing information flows (e.g. democratized communication technologies like Skype) and more physical touch points (e.g. more global travel and larger immigrant communities). Emerging markets and their indigenous companies should see this as an opportunity to boost their competitiveness. But first they require a better understanding of the “jobs” diaspora members are trying to do when they re-engage with their home country or culture, and need to align their strategies to fulfill them.

Why does the diaspora matter? Clearly one reason is remittances: according to the World Bank, over $400 billion was sent back to developing countries in 2012. In Nigeria for example, recorded remittances rose from $2 billion in 2000 to $20 billion in 2010 (a whopping 26% annual growth rate). These transfers feed directly into the domestic economies of emerging markets and boost growth, but they do not necessarily push the country up the development ladder. However, there are two important stages of innovation that do help push emerging markets up that ladder: one involves borrowing developed market technologies and knowledge and adapting them to form new domestic industries (addressing domestic non-consumption); the other involves taking existing domestic technologies or products and exporting them to developed markets. The latter is a vital part of the final climb from developing to developed status — no economy has managed the climb without spawning globally competitive brands. In their October 2013 HBR article on diaspora marketing, Nirmalya Kumar and Jan-Benedict E.M. Steenkamp make the argument for diaspora as a cost-effective platform for emerging market companies seeking to build a global brand.

The knowledge and technology transfer stage, however, is where most developing markets are focused today. Diaspora can play a crucial role in this process for three reasons:

They often achieve above-average success in immigrant communities, and wield influence across many levels of society. As such, they are well-positioned to use their expertise and capital to facilitate knowledge transfers and bridge the gap between emerging and developed countries.

They are inherently motivated to develop their countries of origin.

They are low-touch (or no-touch), compared to non-diaspora investors. They already understand the risks and know how to navigate them.

Today most emerging market countries and their companies have a haphazard approach towards engaging their diaspora. The result is that remittances have grown strongly, but coordinated transfers that build up capabilities have not kept up. To address this imbalance and reap the benefits of the diaspora opportunity, a more targeted approach is required.

Understand the motivations of diaspora communities

The first step is to understand what makes diaspora communities tick. Universities provide a helpful analogy. When engaging with a university after graduation, every alumnus is trying to do a “job”. Sometimes it is a functional job, like improving one’s knowledge on a certain topic or investing for financial gain. Most of the time, however, it is a social or emotional job, like reconnecting with friends, “paying the university back”, or being recognized by peers.

Similarly, diaspora communities can engage their native country with functional jobs (e.g. financial gain) and social/emotional jobs (e.g. self-discovery, need for belonging, family assistance etc.). These social and emotional needs often outweigh the functional needs, and also need to be balanced with obligations in the “host” country.

Emerging market institutions and companies should know their diaspora, not just demographically, but by the jobs they are trying to achieve. University alumni campaign programs often invest disproportionately to understand motivations through detailed surveys. Similar efforts should be directed at diaspora communities to create a “jobs-based segmentation” that facilitates how resources are deployed.

Create engagement opportunities at all levels

In order to foster broad diaspora engagement, emerging market institutions and companies should create opportunities for diaspora communities to be involved at all levels. Some diaspora members may be interested in moving “back home” to take up a position at a local firm, while others may have family obligations in their host country and prefer to provide part-time consulting advice. Still others may need to first be convinced that their efforts will bring just rewards.

Emerging market institutions and companies have limited resources — in terms of capital, people and technology — to court their diaspora, so it is important to seek highly leveraged ways of creating opportunities. Universities often achieve leverage by creating communication channels through alumni leaders, who are not paid employees but have dotted line reporting relationships with the central organization. Through local meetups, these leaders give alumni the opportunity to engage with the school with just their information and ideas. Emerging market companies and institutions can also have community engagement managers who organize local diaspora meetups and act as information liaisons between both sides.

Technology also provides an excellent means of creating engagement opportunities. Even busy overseas professionals with families may be able to spare a few hours a week to mentor young entrepreneurs or act as consultants to domestic companies via web or mobile platforms.

Measure impact and reward engagement

It is important to define the right metrics and measure them steadfastly. If the goal is technology transfer, an appropriate metric may be how many new ventures or products were launched with assistance from diaspora members. If long-term infrastructure buildout is key, the focus could be on diaspora participation in these projects. Universities with strong alumni outreach programs are particularly good at tracking and refining metrics for alumni participation in various campaigns.

Another consideration is how to reward exemplary members of the diaspora. The pre-eminence of social and emotional factors in the “jobs” the diaspora are trying to do hints that most of their incentives should be non-monetary, e.g. national recognition or status. Peer influence through diaspora community sub-groups, for example, is likely to be more effective at driving wide participation than the promise of financial rewards. It is important that these reward incentives are aligned with the right performance metrics.

Ideally, any emerging market’s diaspora strategy should be led by a coordinating body (like the government) and embedded in the operating priorities of the country’s institutions. But the private sector also has a role to play in pursuing more opportunistic lines of diaspora engagement, and companies can step in to lead the way in the absence of an effective government approach. Ultimately, if emerging market institutions and companies are to capture the diaspora opportunity and translate it into competitive advantage, a step change is required in their diaspora engagement models.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers