Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1530

October 21, 2013

Does Bigger Data Lead to Better Decisions?

Many scholars, from decision scientists to organizational theorists, have addressed this question from different perspectives, and the answer, as for most complex questions, is “it depends.” Big Data can lead to Big Mistakes. After all, the financial sector has been flooded with big data for decades.

A large body of research shows that decision-makers selectively use data for self-enhancement or to confirm their beliefs or simply to pursue personal goals not necessarily congruent with organizational ones. Not surprisingly, any interpretation of the data becomes as much an evaluation of oneself as much as of the data.

How can organizations avoid such pitfalls and turn “Big Data” into a safe opportunity? Decade-old research provides some pointers. It is not Big that matters, it is Diversity that matters. Big is old – retailers and financial institutions have had big data for decades.

But Diversity is new. Take large retailers. Sure, they have had enormous databases for long time now. But marketers are only now connecting data from loyalty programs in physical stores with data not only about how the same customers behave on the company’s website, but also how the same or similar customers anywhere in the world behave on other websites – ranging from news sites to car sites to movies sites – all tracked using cookies. They can then link this data with in-depth market research as well as social media data from Twitter or Facebook.

This kind of linkage is reaping rich rewards. A leading Telco company we have worked with was able to increase market share by more than 20% in some countries without increasing the marketing budget by leveraging behavioural and transactional data from social and general media.

Some innovative companies are connecting data traditionally used by banks to assess the credit score of loan applicants with information ranging from mobile phone usage data to online social media relations data, in order to better and faster assess the creditworthiness of a micro-loan applicant. What can a phone bill tell us about the chances that someone will repay a loan? Or even about the creditworthiness of the people that the applicant is connected to online?

Of course, management scholars and practitioners have long recognized the benefits of diversity. It’s widely accepted that heterogeneous teams are more creative than homogeneous ones. Diversity, if managed well, yields divergent thinking and the pooling of a broader base of knowledge results often in better strategic choices.

The point we stress here is that diverse data confers similar benefits. And it’s worth noting in this context that in statistics and data science as well the key quality measures in data are not the size of the dataset but metrics like variance and entropy, which effectively capture the data’s diversity.

So perhaps we shouldn’t be talking about Big Data making decisions better, but about Diverse Data connecting the dots using new technologies, processes, and skills. We need to connect the dots or we risk drowning in Big Data.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Don’t Trust Anyone Who Offers You the Answer

Forget Business Plans; Here’s How to Really Size Up a Startup

Why You Should Crowd-Source Your Toughest Investment Decisions

The Three Decisions You Need to Own

How to Turn Employees Into Value Shoppers for Health Care

Here in the U.S., we fret that our health care system costs too much. We pay too much for diagnostic imaging, drugs, laboratory tests, surgical procedures, and almost everything else. But, given the structure of health insurance, the question should not be “Why are prices so high?” The question realistically should be “Why are prices not even higher?”

Patients are protected by insurance from most of the costs of the care they select and have no reason to shop for the best price. Deductibles and coinsurance expose us to some expenses, but the really expensive tests and treatments appear to many patients to be free. We get past our out-of-pocket cost sharing maximum before we get past the hospital elevator.

The lack of price sensitivity on the demand side of the health care market cannot but influence strategies on the supply side. Why discount prices when you won’t get more customers? Why not raise rates and use the revenues to build new facilities, hire new staff, and acquire new clinical technology? Why invest research dollars in developing innovations that are cheaper as well as better? Why not develop new products that offer minor performance improvements in exchange for major price increases? Does this not sound like our health care system?

Reference Pricing Payoff

One antidote to aggressive pricing by providers is reference pricing by purchasers. Under reference pricing, the employer categorizes drugs by therapeutic class and procedures by geographic market and establishes a limit to what it will pay within each category. The consumer must pay the full difference between the price charged and the limit established by the employer. This contrasts with copayment designs, in which the consumer pays a fixed dollar amount regardless of the price charged, and with coinsurance designs, in which the consumer pays only a percentage (typically 20%) of the price difference. Payments above the employer’s reference price are not subject to the consumer’s annual out-of-pocket cost sharing maximum.

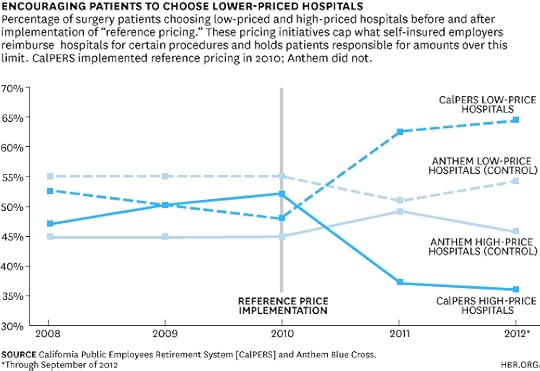

In January 2010 the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) implemented a reference pricing initiative for patients undergoing total knee and hip replacement surgery. The alliance purchases insurance coverage for 1.3 million public employees, dependents, and retirees in California, of which approximately 450,000 are enrolled in its self-insured PPO product. CalPERS was annoyed with having to pay rates ranging from $20,000 to $120,000 for the same procedure at different hospitals, without any indication that higher price was associated with higher quality. It established a reference price limit of $30,000 and identified 41 “value-based” hospitals that charged less than this limit, performed well on quality metrics, and were well distributed geographically. It then launched a communications initiative to its members emphasizing that if they used these value facilities they would be subject only to traditional cost sharing but if they used the higher-priced facilities outside of this group they would incur significant financial liabilities.

The results were striking. The number of CalPERS members selecting low-priced hospitals for their orthopedic procedures increased by 21.2% in the year after implementation, while the number selecting high-priced facilities fell by 34.3%. The percentage of CalPERS members using hospitals with prices below the payment limit rose from 48% in year before implementation to 63% in the year after, and the shift to value hospitals was sustained in the second year.

These changes in patient choices would have surely been even larger if the hospitals whose prices initially exceeded the CalPERS limit had not reduced their rates in response to the new benefit design. Across the high-priced hospitals as a group, prices for knee and hip replacement declined by an average of 34.3%. Across the state as a whole, including initially low-priced facilities, prices for CalPERS fell by 26.3%.

The combination of increased preference for low-priced facilities and price reductions at high-priced facilities saved CalPERS $3.1 million in the first year after implementation. Savings for the first two years exceeded $6.0 million. CalPERS is now expanding reference pricing to ambulatory surgery.

The Long-Term Goal

Reference pricing is no panacea for the inefficiencies of the U.S. health care system. It does not help with the complex decisions about which treatment is appropriate for which patient. Its focus is on price, not quantity. To function well, reference pricing requires valid and publicly available information on price across competing providers. It works best for tests and treatments where there is only limited variation in quality, or where variation in outcomes can be dealt with by directing complex cases to well-established Centers of Excellence.

Reference pricing is being applied by the Safeway grocery chain to laboratory tests and to diagnostic imaging modalities such as MRI and CT. The WellPoint insurance plan has instituted reference pricing for drugs in several markets. Health plans and Internet-based start-ups are aggregating provider price data and combining it with information on the employers’contribution limits to make transparent for each consumer exactly how much he or she will have to pay at each hospital or clinic. Some major employers, such as Lowe’s and Boeing, have established benefit designs that channel patients needing cardiac and orthopedic procedures to the Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins, and other major hospitals in exchange for price and quality guarantees.

It is important not to commit the common error of overestimating the short-term implications of a new initiative and underestimating its long-term implications. Other firms implementing reference pricing may not achieve the CalPERS first-year savings. But the long-term goal of reference pricing is not just to reduce costs to employers but to increase consumer awareness of price and quality differences across providers. Reference pricing is part of a larger effort by employers to transform employees from passive insurance beneficiaries to active shoppers for value.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Britain’s Patient-Safety Crisis Holds Lessons for All

An Obstacle to Patient-Centered Care: Poor Supply Systems

India’s Secret to Low-Cost Health Care

Intelligent Redesign of Health Care

Design as a New Vertical Forcing Function

From Microsoft’s latest radical reorganization and subsequent purchase of Nokia’s devices unit to Google’s acquisition of Motorola, it’s clear that after decades of horizontal integration, high tech is in an age of increased verticalization. Samsung is customizing ARM Holdings’ processor chips, and Google is producing everything from operating systems to consumer hardware. What is driving this change? The objective today, for companies like these, is to control the end-to-end customer experience as much as possible. As Apple demonstrates, in order to deliver coherent experiences across multiple touchpoints — ideally, all of them — you need control. And to meaningfully convert this control into consumer value, you need design.

Design has emerged as a new forcing function in the historical cycle of business integration. It’s what lets companies monetize the intangibles — especially the all-encompassing “experience.” The ability design has to make this possible is fairly well understood, as evidenced by Apple’s continued profitability. The lesson is not that Apple makes simple, beautiful, shiny proprietary objects, but that it creates value by considering the consumer experience holistically.

Careful attention to design means Apple’s retail environment feels consistent with the way its brand is presented online, just as its industrial design supports its interactive experience. Increasingly, its devices are always-open touchpoints, and therefore continuous revenue generators. Your iPhone is more valuable because it syncs seamlessly with your iPad and MacBook; the value of all these devices is enhanced because you know exactly where to go should you have a question about how something works. It’s a level of control over the details that would be impossible in an aggressively partnership-driven industry.

Unfortunately for many companies, the scramble for verticalization is primarily reactive, and it will take time for them to create real value from the reorganization. Apple is firmly established, and as one of the world’s most profitable companies, it has the resources to continue investing in bolstering its position. On the other end of the business spectrum, nimble consumer-driven startups like Pinterest and Square attract significant attention from consumers while driving new types of engagement. No wonder it seems that established technology providers have little choice but to reorganize around consumer experience, and establish greater control. If they don’t, they may not survive this industry-realigning disruption.

But a shift toward increasing control means more than just addressing the functional side of holistic consumer experience. It’s one thing to have all the capabilities your business requires under one roof; it’s quite another to have the courage, vision, and culture to use them to present a coherent experience to your consumers. Making a well-designed, end-to-end consumer experience your top priority requires substantial organizational shifts, and a radically different management mindset. Microsoft’s reorganization was their first step, and replacing the PC-biased Steve Ballmer is a critical second. Apple’s creation of a new SVP of Retail and Online Stores position for former Burberry CEO Angela Ahrendts indicates that their emphasis on highly integrated, user-experience-focused premium devices is here to stay.

Being design-driven means more than simply applying design; it’s surprisingly easy to fail at that. We already see companies addressing this new forcing function through the rise of design leadership, but it remains to be seen if the culture of these companies can truly shift to become design-driven. Google appears to have what it takes, but it’s not at all clear where Sony, BlackBerry, or Dell will end up. There’s already talk of computer OEMs being dead in the water, in fact, and this is surely not the only category of high tech that will be left out in the cold when this cycle is complete. Regardless of what happens, consumers stand to be the primary beneficiaries of this industry shake-up, while companies look to design for an edge in the battle for their hearts and minds.

Under Certain Circumstances, a Warning Label Can Boost Sales

Smokers who saw a cigarette ad that also warned about the risk of smoking bought fewer packs than those who hadn’t seen the warning, unless they were told the packs would be delivered 3 months later. Under those circumstances, people who saw the warning bought 6 times more packs than those who hadn’t seen the warning, says a team led by Yael Steinhart of Tel Aviv University. The warning message increased the ad’s trustworthiness, an effect that became more pronounced when there was a long time lag between the warning and the behavior it was aimed at; the higher trustworthiness boosted sales.

Take Your Show on the Road

Once in a blue moon, a brainstorming session produces an idea that is so blindingly good that people wonder not only “why aren’t we doing that already?” but even: “why isn’t everyone?” As someone who helps businesses conduct “war games” to inform their strategy-making, I suppose I see these moments more than most people; the whole point of these exercises is to devise new marketplace forays and anticipate competitive responses. But still, they are very rare.

So I’ve been especially impressed that one such idea has come up repeatedly in separate games we’ve staged recently. It has made me think I should consider it more closely, and share it more broadly.

The idea is as simple as this: why not have a mobile demonstration van for products, to take a fully-equipped, immersive selling experience to customers’ own sites? The managers who express this idea in our simulated competitive games aren’t thinking of some simple shelving-units-on-wheels format – the kind of oversized salesman’s bag that’s been hauled out to prospects for decades. They’re envisioning well-designed, self-contained environments, tricked-out with the latest high-tech, high-touch technology.

Take the demonstration vans now being used in the UK by Tyco Security which makes products like security cameras, monitors, and access control systems. The company already had a demo center outside London and a slick tradeshow setup to showcase how these work together in an effective system. Its goal for the vans is to replicate the same kind of experience for the customers who can’t come to them.

The beauty of these vans, and the reason I believe they’ve been dreamt up by managers in very different businesses, is that they perform a wide variety of marketing functions. First, they show the product in the best light, in the hands of an expert user. A food company, for example, outfits vehicles with entire kitchens to demonstrate the most effective and creative ways to use its specialty food ingredients in food service operations.

Just as important, the product is not presented as an isolated thing, but as part of an integrated system that solves a problem. The Tyco vans, for example, also feature building management products from other companies to show how the cameras and so forth connect seamlessly with them. “It’s important for our customers to have hands on access to integrated systems,” the general manager of the business explains, “so they can conveniently evaluate the most appropriate solution for their application.”

The vans are also used to provide education and training. Many products can be complicated to operate or dangerous if used incorrectly, and a van can save a customer from traveling to a training center. Providing education on the broader problem the customer is trying to solve gives the vendor a chance to show why its company’s products are better, safer, and more effective. Thinking even bigger, a vendor can consider what training a customer wants its employees to have in general, and provide it in a convenient environment that also carries reminders of the vendor’s product. A heavy equipment manufacturer, for example, brings trucks to its customers’ plants and provides rigorous safety classes for factory workers. This has helped cement the manufacturer’s brand as the most safety-minded player in the industry. Bringing the skills development that customers should be investing in anyway right to their parking lots is the kind of value-adding service that helps lock in channel partners.

I should note, by the way, that the word “van” doesn’t do these vehicles justice – some are as large as 18-wheelers. And sometimes the experience they bring isn’t even contained within the trailer. One industrial producer of state-of-the-art equipment packs its big mobile units with collapsible exhibits which it can set up quickly at construction sites.

And let’s not forget that the vehicles are also rolling advertisements. Is that a sufficient reason to invest in one? Probably not for your company. But if you think no company would invest in a truck and driver just to make brand impressions, you’ve never seen the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile roll by. This giant hot dog on wheels was originally built some 75 years ago just for the visual chuckle. Not surprisingly, 25 years ago, the company discovered the power of putting “ambassadors” on board, and having them criss-cross America taking part in festivals and parades.

As the Wienermobile shows (and also the LL Bean Bootmobile), there can even be a certain amount of excitement generated by the travels of a company’s mobile unit. Cisco Systems, known for its digital telephone switches and routers, had four 25-foot vans touring the country from 2004 to 2011, to events put on by its channel partners. Its Network on Wheels program showed off new products, emphasizing applications most relevant to a given event (often focused on one vertical industry). To let people know when a van would be in their area, Cisco created Twitter accounts for the vans, which managed to attract over 2,800 followers. The social media channel was another source of feedback to help Cisco hone its marketing messages.

Retailers complain about showrooming, where customers visit expensive brick-and-mortar stores to educate themselves about offerings, only to leave and order their choices from cheaper sellers online. At the B2B level, vans have turned this dynamic on its head, investing in assets explicitly to provide showrooms that educate and raise awareness. The expectation is not that the visit will end with the ka-ching of a cash register. The point is to enrich the customer’s relationship with the brand.

So if you’re in a B2B business – and perhaps even if it’s B2C – spend some time thinking about an idea that keeps coming up in competitive simulation exercises. I see it as a quietly effective strategy that has been rolling along, largely under the radar. It isn’t the version of “mobile marketing” that is all the rage now in business press – but it might be the best way you’ll find to drive sales.

October 18, 2013

How Jeff Bezos Makes Decisions

Over the last 19 years, Amazon.com has revolutionized the way we shop—and for much of that time, journalist Brad Stone has been watching closely. This week Stone, a senior writer at Bloomberg Businessweek, published The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon. I talked with Stone about the evolution of Bezos as a decision-maker. Some excerpts from our conversation:

In the course of your reporting, what did you observe about Bezos’s decision-making style?

Two factors come to mind. The first is an observation made by Rick Dalzell, his right hand guy. He says that Jeff does two things better than anyone else. One is that he tries to find the best truth at the time. That may sound obvious, but Rick says that while a lot of people know what the truth is, they don’t engage their thinking about how the truth may change. Second, Rick says that Jeff refuses to accept the conventional wisdom about the way things are typically done. He thinks about reinventing everything—even small things. Two weeks ago, for instance, Amazon introduced the new Kindle Fire tablets. Ordinarily when tech companies do this, they hold a big press conference. Instead, Jeff brought about two dozen reporters in to see him in small groups. He did all the product demos himself. Everyone left feeling like they had a special session with this dynamic CEO, and Amazon received great press coverage. It’s a small example of how he tries to reinvent how things are done.

Your book describes Bezos berating and belittling employees, and overruling a lot of their decisions even if he has less information than they do. Why does he behave that way?

It’s partly because he demands such excellence out of everyone around him, and he’s always the smartest guy in the room. He’s always pushing people to rise to his level. He really wants people to think big—that’s a frequent phrase around Amazon. When people aren’t exhibiting that We’re-going-to-conquer-the-world mentality, he gets frustrated. But in fairness, a lot of the examples in the book of him behaving that way are older ones, and I think he’s gotten better over time. He has modulated this behavior.

You spoke with an educational researcher who spent time with Bezos when he was 12 years old and attending a gifted-and-talented school. Do you think growing up as the smartest kid in school led Bezos to be overconfident in his decision-making skills?

Well, his confidence does backfire sometimes, and Amazon has made mistakes. In the 1990s, he was convinced the Internet was going to change everything, and he raced ahead without hesitation. He borrowed billions to expand, and it came back to bite him: He thought the runway was longer than it was, and he spent five years [being punished by investors] for that. So there are times when he can be too optimistic. That’s why he bought The Washington Post — he’s optimistic he can create these new businesses on the Internet [even as] the old incumbents are going away. He tends to march ahead without the least hesitation.

You describe Bezos as surrounded by a group of high-level “Jeff-Bots” who mimic his behavior and sayings. When it comes to decision-making, do they serve as Yes Men or can they push back?

The term Jeff-Bot does connote a bit of mimicry, but it’s also about loyalty. Jeff’s leadership style is infectious. The people who do the best at Amazon are the people who absorb his principles. I don’t think the Jeff-Bots are Yes Men—they just have internalized the way Jeff thinks. Amazon is fairly decentralized, and some of these executives run their own businesses and make their own decisions. A great example is Andy Jassy, who was the first official “shadow” at Amazon. For two years, his job was to follow Bezos around as his chief of staff, attending every meeting with him. Andy became an accomplished executive—now he runs Amazon Web Services, which is an incredible business.

Bezos shows a remarkable ability to disregard Wall Street when making decisions. How is he able to do this when so many CEOs can’t?

This wasn’t always the case—really, it’s the payoff for being right. In the late 1990s the Street trusted Bezos, then for five years it didn’t [after he’d grown Amazon too quickly]. But during this time Amazon called its shots predictably and consistently. Bezos ended up basically recruiting a base of shareholders who trusted him and believed his story—people like Bill Miller of Legg Mason. They saw him operating the company with discipline, and they recognized that Amazon was a profitable business but that there were phases where they’d be investing in a new capability [that would hurt profits]. So it’s the credibility of the founder that made the difference. Once you’ve proven that you have the right mix of visionary insight and operating capabilities, Wall Street lets you get away with a lot. There aren’t that many other CEOs who have that credibility. Although she’s not a founder, I think Marissa Mayer has some of it at Yahoo. Larry Page definitely has it, although he wasn’t Google’s CEO the whole time.

Amazon uses some unique decision-making tools: Instead of PowerPoint, meetings begin with everyone reading a six-page memo outlining the issue to be discussed. They have an elaborate system to decide whether to promote people. Would these tools work well at other companies?

Probably not. They’re so highly tuned to the ways that Jeff Bezos processes information. In the book I write that the entire company is really a scaffolding built around Jeff’s brain. It’s set up as if there’s a series of chess boards positioned so that Jeff can play all these games at the same time in a highly efficient manner. Groupon, which has a lot of ex-Amazon people, tried some of these techniques, and it’s a tough sell. Starting a meeting with 20 minutes of silence so everyone can read a memo just isn’t the way most businesses operate, and it’s hard to adjust to that.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Don’t Trust Anyone Who Offers You the Answer

Forget Business Plans; Here’s How to Really Size Up a Startup

Why You Should Crowd-Source Your Toughest Investment Decisions

The Three Decisions You Need to Own

If Everyone Hates the FDA Approval Process, Let’s Fix It

There is one certainty about the current regulatory process for drug approval in the United States and Europe: No one likes it.

Manufacturers are frustrated by the need for large, complex, and lengthy clinical-development programs that often hinge on meeting a single endpoint in one pivotal clinical trial. As a result, the cost to bring a drug to market has been estimated to be well over $1 billion — and it may be much higher. Patients and providers are disturbed by lack of timely access to medicines that show early promise in addressing significant unmet needs. Even regulators, who are responsible for enforcing the current structure, chafe at what manufacturers typically present to them: successful trial results in patients who are carefully selected to show the drug offers benefits but who are not very representative of the broader population likely to receive it. Payers then have a mess on their hands: pressure to pay for premium-priced medications that, when broadly employed, don’t offer much therapeutic benefit over existing alternatives.

Can this process be altered? Yes, but it will require a true reinvention of the regulatory drug-review process that addresses all of the flawed assumptions that exist with the current framework. One potential solution is adaptive licensing (also called “staggered approval” and “progressive licensing”), a novel approach that is currently being discussed by manufacturers, regulators, and other stakeholders.

Under adaptive licensing, the clinical-development program is restructured to allow for early approval of a new compound for a limited, typically high-risk population based on valid clinical measures from smaller human studies. Approval would be revisited at several points along the clinical-development pathway as candidate populations are broadened, longer-term outcomes are evaluated, and risks of treatment are better understood. Indications for treatment would be broadened (or restricted) accordingly at each step.

Initial Reforms Don’t Suffice

I would argue that some of the attempts to streamline the current review process are only minor modifications and fall short of what is needed. For example, the “accelerated approval” pathways used by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for certain drugs have generally been limited to small reductions in the time allotted for evaluation of the traditional submission package or use of “surrogate” endpoints (e.g., reductions in blood levels of a cardiac biomarker rather than reductions in risk of stroke or MI). This latter approach has been controversial, because many proposed surrogates have proven themselves merely to be correlates of disease rather than important components of the causal pathway.

Advantages of Adaptive Licensing

The basic concept at the heart of the adaptive licensing approach is that the review process should be a “learning system.” Breakthrough therapies would be made available to patients much earlier in the regulatory process. Presentation of clinical data to regulators in a stepwise fashion throughout drug development should allow the drug company to better target those patients for whom the benefits of the therapy outweigh the risks and should result in more informed decisions on withdrawing the drug from the market if the risks are simply too great for anyone.

(In the current paradigm, safety concerns are often not raised until well after regulatory approval. The reasons: regulators don’t get any hint of safety issues until they are presented with the submission package, and given the significant investment required to bring the drug to regulatory attention in the first place, manufacturers have no incentive to undertake a full exploration of safety.)

Unanswered Questions about Adaptive Licensing

One is whether current regulatory controls are sufficient to prevent a new medicine from being used for purposes that go well beyond the initial, limited indication. Do manufacturers need to commit to adding their own controls? It also may be the case that manufacturers will need to augment traditional efficacy studies with long-term observational studies that start earlier in clinical development in order to detect potential safety signals much sooner.

It is also clear that little progress on implementing adaptive licensing will be made without explicit cooperation from all stakeholders. All parties must feel that they can participate in confidential discussions that involve full disclosure. An ambitious program created by MIT’s Center for Biomedical Innovation, known as NEW Drug Development ParaDIGmS (NEWDIGS), has been created to serve as this “safe haven.” The program has made substantial progress in convening stakeholder workshops to (a) discuss the promise and pitfalls of an adaptive licensing approach, (b) quantify the potential benefits of adaptive licensing through historical case studies, and (c) develop standards for determining candidate compounds for adaptive licensing.

An Obstacle: The Existing Mind-Set

But the biggest unanswered question is whether we can collectively shift the paradigm enough. I was privileged to be invited to a recent NEWDIGS workshop to help represent the payer community. During the workshop, we discussed an actual compound that had been developed for a rare condition that represented a significant unmet need. The manufacturer had clearly done its homework on adaptive licensing and presented a thoughtful approach to clinical development that featured early authorization based on a clinically-validated endpoint, followed by longer-term studies evaluating both drug safety and “harder” outcomes (in this case, survival).

The initial pushback from regulator and payer representatives (including me) was all-too traditional: “How do we know this endpoint is associated with improved health status for the patient?” “How much bigger and longer would the first study need to be to show impact on survival?”

The frustration was evident on the manufacturer representatives’ faces. It took us until well into the afternoon to realize that we were asking them to chop a traditional clinical-development program into bite-size chunks rather than engaging in a true rethinking of the approval process. They were presenting us with their best approximation of a clinical-development program that would reduce initial investment, provide useful early clinical information, and mitigate patient risk, and we threw the old process back at them. We did eventually arrive at a good place (i.e., discussions will continue based on the adaptive program as presented) but not without a lot of pain.

And so it is clear that yes, adaptive licensing requires cooperation and information-sharing among all stakeholders as well as candidate compounds that meet the criteria for such an approach. But the success of an adaptive approach really only hinges on whether we are willing to shift the current regulatory paradigm — a radical change in thinking about what we as a society want the products of a drug-development program to be, when we want to see results, and how much risk we are willing to bear at each step in the process.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Britain’s Patient-Safety Crisis Holds Lessons for All

An Obstacle to Patient-Centered Care: Poor Supply Systems

India’s Secret to Low-Cost Health Care

Intelligent Redesign of Health Care

Do Apps Have Social Responsibility?

What responsibility does the maker of a fitness social network have for the safety of its users — and the general public? This lengthy investigation by David Darlington takes a close look at Strava, one of biking's most successful sites and apps, which does exactly what a good social tool should: It allows you to track your athletic progress and compare it with others’, all the while tapping into curiosity, self-interest, and social competition — three of the brain's chief dopamine drivers.

But after two people died in connection with the site — a cyclist was killed while attempting to reclaim what's known as King of the Mountain [KOM] status as the fastest rider for a given route, and a pedestrian was struck and killed by a speeding biker two years later — the cycling, start-up, and legal communities were forced to take a close look at whether Strava was creating and reinforcing competition at society’s peril. I won't give away the end of the piece, which involves a potential legal nightmare for any company that asks users to hit an "Agree" button after reading terms and conditions. But the Strava case is prescient as we continue to develop digital technologies that influence the emotions and impulses that make us so darned human.

So SorryWant People to Trust You? Try Apologizing for the RainBritish Psychological Society

When a stranger simply asked people if he could use their phones, just 9% said yes. But if he first said, "I'm sorry about the rain!" (it was, in fact, raining), 47% allowed him to use their phones. This experiment, from a team led by Alison Wood Brooks of Harvard Business School, is part of a series of studies showing that people will trust you more if you apologize for things like the weather, flight delays, and computer glitches, even though these problems are clearly beyond your control. Apologies are a "powerful and easy-to-use tool" for social influence, the researchers say. (What about afterward: Would it be appropriate to say you’re sorry for having apologized in order to manipulate someone’s feelings? Just asking.) —Andy O'Connell

38 Slides’ Worth What I Wish I Knew Before Pitching LinkedIn to VCsReid Hoffman

The year is 2004. Reid Hoffman is armed with a relatively new website and a PowerPoint presentation for a Series B investment pitch at Greylock. Fast-forward 10 years: LinkedIn is a wildly successful social network and publishing platform, and Hoffman is a partner at the very same VC firm that once funded his idea. As an investor, he realized that budding entrepreneurs might gain a lot from — but rarely get to see — other companies' presentation slides. So he published his entire slide deck, complete with his annotations offering context, advice, and ideas about things he should have done differently. If you're an entrepreneur, it's a pretty eye-opening blueprint for presenting your ideas. If you're not (like me), it's one heck of a study into how drastically the digital landscape has changed in a decade. And if you don't have time to view the entire presentation, Hoffman also created a distilled list of funding and presentation myths.

Je Ne Sais QuoiHome Away from Home: What Makes Consumers Support Their Favorite Businesses? Journal of Consumer Research

It's not often that an academic study in a consumer-research journal makes me verklempt, but a paper in the Journal of Consumer Research by Alain Debenedetti of the University of Paris East and two colleagues is, among other things, a paean to a very special place: a homey, welcoming wine bar in France that one of the members of the research team "had regularly visited for many years." If we all had a bar like this on a nearby corner, I’m sure there would be no wars or strife. With its bistro tables and chalkboard menu, it offers a "quintessentially traditional French atmosphere." In studying why people love certain physical spaces, the researchers interviewed the bar's visitors. One says she feels as though she's having "dinner with buddies" when she eats there; another reports that he once quarreled with the owner, but then they made up. Another describes being invited to the bar's special "guest table": "It only occurred once for me. It was great. I tasted wines I did not order, it was a moment of sharing... I had the feeling that I was part of something." Lovely. And so much like the McDonald's on my American street. —Andy O'Connell

Tempest in a Teapot?How Hollywood can Capitalize on Piracy MIT Technology Review

When the rogue file-sharing site Megaupload was shuttered in 2012, legal online revenue for blockbuster films rose. No surprise there. But a new study by researchers at the Munich School of Management and Copenhagen Business School found that worldwide box office receipts for all but the biggest films actually declined. Why? The word-of-mouth promotion that’s crucial for smaller-budget films can’t begin until someone sees it, and that often happens through an illegitimate download from a "torrent" site.

Even a cursory examination of box office figures suggests that more is gained than lost through the piracy sites: 2012 was Hollywood’s best year in history, with $10.8 billion in North American ticket sales and a 6% increase in theater attendance over 2011. There are signs that industry players are beginning to recognize and capitalize on bootlegging. Last spring, for instance, HBO executive Michael Lombardo caught a lot of flak when he declared online piracy of the network’s Game of Thrones to be a “compliment of sorts.” But the first season of Thrones became the best-selling television DVD of 2012 on Amazon, and the third season got better ratings than any other show on HBO. —Andrea Ovans

BONUS BITSWhere Are You Going, Where Have You Been?

Ladies Last: 8 Inventions by Women That Dudes Got Credit For (Mother Jones)

Four Executives on Succeeding in Business as a Woman (The New York Times)

How Feminism Became Capitalism's Handmaiden — and How to Reclaim It (The Guardian)

The Pitfalls (and Upsides) of Partnering with Entrepreneurs

To en·gage ( n-g j ): To pledge or promise, especially to marry; to draw into; to involve; to enter into conflict with

Corporate executives are exhorted daily by well-meaning public leaders that they should support their local entrepreneurs in order to be good corporate citizens and to bolster local economies. But engagement with entrepreneurs is not a question of conscience or moral imperative; it is a question of strategic self-interest. As any experienced corporate leader knows, engaging entrepreneurs has potentially the same spectrum of pleasure and pain reflected in the formal definition, from the prospect of inextricable involvement including conflict, to the promise of partnership, to the happy possibility of union in blissful corporate matrimony and acquisition.

Let’s start with the pitfalls, because these are often ignored or discounted in frothy discussions about the economic benefits of entrepreneurship. Why would companies avoid engaging with entrepreneurs?

Waste of time. One CEO of a NYSE traded company told me recently that he avoids entrepreneurship networking events in his community because he doesn’t want to be overwhelmed by business seekers pushing cards into his hand, to be followed up by annoying calls to sell anything from gadgets to insurance. Instead, his company has a system for screening and studying the 200 or so proposals they receive annually. He is damned if he will pay attention to each persistent business owner, but then damned as a bad community member if he ignores them. His conclusion — disengage from networking events with entrepreneurs.

Legal entanglement. Many corporate executives have been warned by counsel, or have learned the hard way from experience, that listening to the impassioned pitch of a team of startup entrepreneurs may expose them to litigation further down the road in the event that they embark by themselves upon a similar product or service, even if its origins may be totally unrelated to those described by the entrepreneurs.

Commercial incompetence. Many a corporate executive has braved the skepticism of his or her corporate colleagues and plunged ahead into well-intentioned alliances with startups. Often, they come to find that the majority of new ventures don’t understand corporate decision cycles, purchasing requirements, compliance processes, post sales customer service, and the like. Persuaded initially by the entrepreneur’s whiz bang innovation, corporate executives can then find themselves stuck in a morass of very basic coaching and grooming of their young new partners on the one hand, while fending off the cries of delayed shipments or poor quality from customers further down the line.

Financial fragility. Intrinsic in entrepreneurship is a long period of living in a twilight fluctuating between breakthrough market success and breakdown (i.e. going out of business) when revenues are too few too late, and expenses are too many too soon. Many corporate executives fail to realize just how close to the precipice many startups are. But that is the territory of entrepreneurship — even with deep financial backing from the rare venture capitalist or angel investor (yes, these are the exceptions in entrepreneurship, not the rule), long term viability of any venture is far from guaranteed and can leave the corporate partner in the lurch. (No wonder the experienced executive frequently insists that software code be placed in escrow.)

Then there’s the upside. Of course, engagement with entrepreneurs can lead to innovative new products, lucrative investments, new supply chains, advanced technology, and a more creative corporate culture. No one can say with certainty whether or under what circumstances the potential benefits outweigh the potential pitfalls. But if you do believe, as many corporations are learning, that the balance is potentially positive if handled well, then here are a few suggestions for improving the experience and increasing the value:

Define “engagement” at the most senior management levels as a process that has to be learned over a long time, with lots of experimentation and learning from mistakes, in order to derive the benefits of engaging entrepreneurs, whether through contract, investment, or acquisition.

Allow different functions and divisions autonomy to explore different manifestations of engagements with entrepreneurs, whether through supply chain expansion, joint product development, or technology licensing. These are typically handled by different divisions which may be located, culturally and geographically, far from each other.

Encourage learning across the organization. Although action may be diffuse, the different divisions engaging with entrepreneurs for different strategic purposes have a lot to learn from each other, and can systematically share knowledge and experience by regular meetings and conferences.

Distinguish between global, sector-driven, or division-specific involvement and geographically concentrated ecosystem enrichment. A leading global IT company I know has innovation centers in each of the major continents with the purpose of fostering a broad entrepreneurship ecosystem whether it is directly related to the company’s products and technologies or not. On the other hand, I interviewed a leader of a global life sciences company that was concerned solely with tapping into the best, most specialized technology in a carefully prioritized set of products, regardless of geography

Develop a triage function. It is often surprising to entrepreneurs sitting at the edge of the corporation, but in many cases corporate executives have difficulty engaging with other divisions in their own company. Efficient internal networking and channeling is an ability developed over time within the context of specific corporate structures and cultures. Having an executive function that knows how to interface well with the entrepreneurial community while maintaining credibility and contact within the corporation helps mitigate some of the pain of the process.

Avoid dichotomizing between small and large. Research and practice both reach a clear conclusion: entrepreneurship ecosystems evolve in the context of a rich dialog across the entire spectrum of sizes, technologies and growth rates. The emergence of pure “startup communities” is a revisionist myth. The entire spectrum of private sector companies is interdependent in many complex ways.

Many corporations have withdrawn from entrepreneurial partnering having been burned by a greatly disappointing, acquisition or partnership. But effective alliance management with entrepreneurs is a competency that needs to be strategically defined and tactically executed over time, if executives are to learn the art of entrepreneurial engagement.

Three Cognitive Traps that Stifle Global Innovation

Which is the more likely cause of death — shark attack or falling airplane parts? The answer to Nobel prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahnemann’s question is surprising; falling airplane parts. (In fact, you are 30 times more likely to die from a piece of falling airplane than you are at the jaws of a shark.) We have tested this query with senior executives across multiple continents, and they inevitably get it wrong. Why does this happen? Events are perceived as more likely to occur if they are easier to bring to mind. We have the TV special Shark Week and movies like Jaws to remind us of the danger of sharks, but there is no Airplane Debris Week. With unfamiliar, low probability events, disproportionate media coverage can lead to gross estimation errors.

Mis-estimation is not restricted to predicting danger. In business we frequently market to consumers whose experiences are far removed from ours and so we often make assumptions about how these consumers behave.

When we look at markets different from our own we often have little information. While formal information may exist in the form of statistical data from organizations like the World Bank and consulting firms, the information which is most easily brought to mind is from the people we happen to have met, or from the media. Thus, soccer and Gisele rank right at the top of our associations with Brazil, giraffes and Somali pirates with Africa, and ouzo and debt with Greece — whether this is fair or (more likely) not. All of us have a tendency to hang our hats on what we do know no matter how unrepresentative it is. Our work, and this blog, focus on how and why assumptions lead to failures – and what you can do to prevent them.

Avaibility is the first assumption trap. For instance, the dishes seen in British curry houses, such as Chicken Tikka Masala, are far from representative of Indian cuisine. But that’s what’s available; so that’s what the usual Brit thinks of when you talk about Indian food. Similarly, most executives in developed countries have some familiarity with developing countries’ urban, affluent, rapidly growing middle classes. This urban middle class is noticeable – it shares characteristics with many multinationals’ home markets and is far easier for the affluent, professional manager to relate to. Plus, when traveling on business, most executives are in and out of major urban hubs. Consequently the urban middle class receives all the attention, while the less noticeable but potentially far higher growth in the semi-urban and rural markets is ignored.

Here is an easy test to diagnose whether you suffer from availability bias. How do you think people in another country live? Picture this to yourself. Then search “A typical day in the life of a (enter nationality here),” that country’s World Bank Country Profile, and their leading local newspaper . Read the top three search results of each carefully. If the results are far removed from what you visualized earlier, you probably suffer from availability bias.

Confirmation bias is the second assumption trap. When we hold a hypothesis passionately and are confronted with ambiguous information, we latch on to anything consistent with our original hypothesis. The ambiguous data becomes clinching evidence. To give a concrete example: A European multinational had just launched its building material product line in India. Many of the product’s technologically superior features were over-engineered for much of the Indian market. Consistent feedback from the Indian sales force was that the customers were saying: “You are selling gold. We are looking for bronze.” The company, unwilling to let go of their assumptions, maintained that the products were appropriate for the market, but that the local salespeople simply did not have the skill to sell the range. The company’s managers felt vindicated (if briefly) when a global product executive visited India. After hearing numerous customers complain about over-engineered products the executive eventually saw a single, stellar salesperson encounter a high value customer, patiently demonstrate each and every superior product feature, and finally make the sale. Latching on to the prevailing assumption, the executive reported home, citing this one incident in great detail as conclusive evidence that “the products were indeed suitable, salespeople just needed the skills to sell them.” The result: no product changes but large investments in skills training. It took years of losses, and two new country CEOs, before the company realized the folly of its assumptions.

Can you remember the last time you were surprised by a piece of new information — and changed your mind as a result? If not, you might be trapped in confirmation bias.

The third assumption trap is the variance bias, (known to psychologists as out-group homogeneity bias). We see fine-grained differences in groups we identify with, but underestimate variance in distant cultures. We’ve seen Americans who think that New Yorkers and Californians are dramatically different but then talk about “Indians” as if they can be seen as a unified whole. This is a two-way bias. To many Indians, “Americans all love Big Macs”, but India “is a land of many languages and many cultures.” Variance bias leads to the systematic underestimation of opportunities outside the mainstream taste. This provides spaces for local competitors to flourish and grow and may explain why the multinationals successful in many emerging markets are those that have been there for a very long time. They often have a proliferation of brands and variants and importantly, they have learned, over time, to recognize and cater to this diversity.

Variance bias is hard to spot, but ask yourself a question. Do you really think the 1.3+ billion Chinese are less diverse than the 300+ million Americans? If so, sit back, take a deep breath. Now try and explain logically why that would be the case.

Read the local press, be curious, and approach with an open mind. A highly successful country CEO at Legrand, the French multinational, who worked in multiple BRIC countries, told one of our co-authors, “You never fully understand a country until you get lost in its markets.” He used to wander through the main market places, soaking in the experiences. When he was lost, he would call his driver and describe the location where he should be picked up. It is no surprise that this executive went on to global product management and then moved to a larger, and significantly expanded role in an emerging market.

Identifying these three assumption traps will help you get it right the first time, and better innovate for consumers across global markets. Indeed understanding what you don’t know is vital to preventing many a costly failure.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers