Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1527

October 25, 2013

How to Rehabilitate Medicare’s “Post Acute” Services

Among the 20% of Medicare patients who are hospitalized each year, almost half require care after being discharged from the hospital to assist them in their recovery from serious illnesses. These “post-acute” services — home health, skilled nursing, inpatient rehabilitation, and long-term hospital care — are essential. However, under current Medicare policies, their providers have neither produced consistent value nor had the flexibility to meet the changing needs of our patients. Medicare spending on post-acute care has doubled over the last decade, growing twice as fast as physician and hospital spending without clear evidence of improved patient outcomes. Eliminating geographic variation in post-acute care would reduce total Medicare variation by 73%.

In response, President Obama called for changes to Medicare post-acute payment in his 2014 budget. House and Senate committees have scheduled hearings to consider the President’s proposals, and bipartisan Congressional leadership has asked for public comment. As physicians who work on post-acute care improvement for Partners HealthCare, we present four strategies for rehabilitating quality and value in post-acute care.

1. Medicare must continue to develop accountability-driven payment models.

We are excited that new accountability-driven reimbursement models created by the Affordable Care Act such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments reward health systems for providing efficient and effective post-acute care. Partners participates as a Pioneer ACO, and in our first year successfully slowed our rate of cost growth by more than 2.4% as compared to the national benchmark. Participation in the Pioneer ACO has catalyzed multiple efforts to evaluate and invest in post-acute care. Such investments include readmission-reduction and care-transitions initiatives, best-practices and data-sharing collaborations with skilled nursing facilities, and new home-care programs such as telemonitoring, rapid-response home-nursing visits, and home-based palliative-care consultation.

We are optimistic that ACOs and bundled payments will both produce savings and improve quality in the post-acute sector. However, considerable technical challenges remain, particularly for bundled payments. These include determining the proper duration of the bundled episode, target payment rates, and risk-adjustment methodologies.

2. Congress must reform Medicare’s fee-for-service payment systems.

Accountability-driven models such as ACOs and bundled payments are built upon and do not replace the existing fee-for-service payment structure, and significant numbers of providers remain outside these models and continue to bill solely through fee for service. As such, improving fee-for-service payment remains essential, and efforts to do so should be centered on improving value-based purchasing programs and reforming the systems for reimbursing skilled nursing facilities and home health services.

Value-based-purchasing initiatives tie fee-for-service payments to performance on certain quality metrics. In the case of hospitals, many of these metrics are dependent upon care delivered outside hospital walls, such as 30-day readmission rates. This has given hospitals a stake in care delivery both inside and outside of their control and pushed many hospitals for the first time to become invested in post-acute care. Many of these initiatives suffer from design flaws, and providers and Medicare must continue to work together to improve the measure parameters. However, for all their imperfections, these initiatives have turned hospitals into engaged stakeholders in the post-acute space and should be continued to be developed and improved.

Such evolutionary changes are not sufficient for skilled nursing facilities and home health, whose payment systems need to be fundamentally redesigned. Medicare pays skilled nursing facilities “per diem,” encouraging excessive lengths of stay. Local and national health-systems data reveals that the length of stay in nursing homes of patients covered by Medicare Advantage plans, which have greater flexibility in payment than traditional Medicare, are 20% to 50% shorter, on average, than that of Medicare fee-for-service patients.

One promising alternative is a risk-adjusted prospective payment per stay in a skilled nursing facility, similar to the system for hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, and long-term-care hospitals. Based on statistical modeling, we project that a case-based prospective-payment system could be rolled out across fee-for-service Medicare without disrupting provider revenue cycles, would facilitate improvements in patient outcomes, and could save Medicare over $4 billion annually.

The payment system for home care also must be revamped. Currently, home health agencies are paid based on 60-day episodes, which do not match patients’ diverse needs. (Many need just a single home visit while others require many months of intensive ongoing home-based services.) A payment system that flexibly matches reimbursement with care needs, rather than being limited to a time-delineated episode, would provide greater value as well as spur the adoption of innovative home health services such as brief transitional-care visit(s) for home- and non-home-bound patients, intensive care “bursts” (e.g., daily home visits for a defined period), and telemonitoring services.

3. Providers and payers must invest in comparative effectiveness research, quality measurement, and data access.

During the transfer from acute to post-acute care, clinicians must select the right level of care for their patients (e.g., a skilled nursing facility versus a home health service); identify high-quality, post-acute providers; and ensure a smooth care transition.

More comparative effectiveness research is needed to help clinicians make evidence-based decisions about the most appropriate level of post-acute care and deployment of care-transitions programs. In the absence of evidence-based guidelines, well-meaning, risk-averse physicians will err on the side of prescribing post-acute care that’s more intensive than necessary even if there is little evidence that it actually improves outcomes such as readmissions.

Further, existing tools for assessing the quality of post-acute care are not robust enough for clinicians and patients to make informed choices at discharge. To fill this gap, we at Partners are developing our own dashboard of quality metrics for skilled nursing facilities in collaboration with local skilled nursing facilities and other Eastern Massachusetts ACOs. We appreciate the support of many partners in advancing this work, and similar efforts are being replicated in health systems across the country. These health system efforts should be complemented by greater research investments at the federal level.

In addition, Medicare Advantage plans have had greater flexibility (PDF) to develop novel post-acute reimbursement schemes and innovative care-transitions programs than traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Such efforts appear to have reduced hospital readmission rates 13% to 20% compared to traditional Medicare. While balancing the obvious competitive concerns, Medicare should consider opportunities to examine and share Medicare Advantage data and experience to accelerate learning.

4. Medicare must reduce the regulatory burden to enable flexible clinical decision-making.

Clinicians need the flexibility to offer the right level of post-acute care to patients at the time they need it. However, Medicare’s eligibility and administrative rules create logistical headaches and placement restrictions that are both costly and hinder patient recovery. For example, patients must be hospitalized for three days to qualify for care in a skilled nursing facility (the “three-day rule”), limiting discharge options and unnecessarily extending hospital stays. Other regulations include the “25% rule” for long-term hospitals, the “60% rule” for inpatient rehabilitation facilities, and so forth.

These restrictions are meant to limit inappropriate utilization but seem frustratingly arbitrary to providers and patients alike. To balance these concerns, Medicare should waive post-acute eligibility requirements when providers accept accountability for quality and value (e.g., through ACOs). Indeed, Medicare recently began allowing Pioneer ACOs to apply for a waiver of the three-day rule. This is a step in the right direction.

The Way Forward

By providing essential medical and rehabilitation services to patients recovering from acute hospital stays, providers of post-acute care are ideally positioned to improve patient outcomes while reducing health care costs. However, the post-acute-care sector has not achieved its full potential. It can deliver high-quality services but is not always rewarded for doing so; could reduce Medicare spending but has driven cost growth; and gives doctors multiple options for discharge but has restrictive eligibility requirements. Medicare must allow for greater quality, accountability, and flexibility, which will empower health systems to deliver the post-acute care that patients need and deserve.

This piece was adapted from written testimony prepared for a U.S. Senate Committee hearing, which has been postponed indefinitely. Click here to view the full testimony.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Negotiation Strategies for Doctors — and Hospitals

How to Turn Employees Into Value Shoppers for Health Care

If Everyone Hates the FDA Approval Process, Let’s Fix It

Cutting Costs Without Cutting Corners: Lessons from Banner Health

When It’s Wise to Offer Volume Discounts

On the way to a recent barbecue, I dropped by a local gourmet market to pick up ingredients to make my famous Korean-style ribs. While the butcher was initially thrilled with my unexpectedly large 30 pound order, his mood soured when I asked him to thinly slice the ribs “flanken style” (cut parallel to the ribs). After 20 minutes of intense slicing (and several reminders to “slice it thinner”), the meat was ornately packaged and ready to go. Then, out of curiosity – let’s call it “research” – I asked if I was entitled to a volume discount since I was buying so much. Without giving it a second thought, the butcher chopped the per pound price from $8 to $6. As a consumer I appreciated the $60 savings—but as a consultant who helps businesses optimize their pricing, I wondered if the butcher realized how much of the store’s operating profit margin disappeared due to his hastily-considered discount.

In my work with companies on their pricing strategies, I’ve noticed that virtually all managers price according to the mantra of “the more you buy, the lower the per-unit price.” “Why?” I always ask. A common refrain is, “It’s a token of appreciation to our customers.” I agree–it’s important to express gratitude in a business transaction. However, there are many less costly alternatives such as, say, a handwritten thank you card. And remember, not every customer is seeking a discount – so providing one may be costly and go unappreciated. Some managers claim that since customers believe it’s cheaper to sell larger quantities, they feel compelled to provide a lower price. I understand, but since when are the specifics of your company’s cost structure any of your customers’ business?

There are only four primary reasons to offer a volume discount:

To capitalize on the law of diminishing utility: The concept of “the more one person consumes within a period, the less they value a product” is a cornerstone of microeconomic theory. Convenience stores and movie theaters, for instance, understand that thirsty customers are willing to pay a hefty price for the first 12 ounces of a cold soda relative to the next 12 ounces. To entice customers to consume more, the additional per-ounce price is significantly reduced in larger cup sizes. As a result, consumers are often faced with the conundrum of calculating whether it’s worth it to spend an extra 75 cents to double the size of our fountain drinks.

To compete with rivals who offer them: If your close competition provides volume discounts and you believe that by not granting similar price breaks you’ll lose the sale to a rival…trim away.

To lock in customers: In highly competitive markets, volume discounts nudge customers to commit, to the detriment of rivals. If a competitor is entering a market, locking-in customers preserves market share as well as thwarts the new entrant.

To encourage a large order instead of a series of small ones: Pharmacies often offer a discount if you purchase a year-long supply of a common prescription, for instance, instead of filling it monthly. This price break yields higher profits as pharmacies only have to incur the costs of filling a prescription once, instead of twelve times.

Although it’s counterintuitive, there are actually opportunities to increase prices for larger volumes as long as the premium can be justified by providing additional value. Magnums of champagne (1.5 liters) are often sold at more than double the price of individual 750ml bottles. Why? One reason is because it’s more festive (and hence valuable) to show up at a party with a magnum compared to two regular bottles. Magazines, for instance, can sell collections of back issues for a premium if they provide additional value such as special packaging, rare issues, and a collection-wide index.

While there are sound reasons to provide volume discounts, most companies over use them and offer them with too little thought. The next time you are contemplating offering a volume discount, ask yourself, “Do I really have to do this?” Back in my gourmet store, I’d already committed to buying 30 pounds of Korean ribs, discount or no discount. It was a classic case of a manager extending a discount that took a wholly unnecessary slice out of profits.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Make Better Decisions by Getting Outside Your Social Bubble

How Do You Know What You Think You Know?

Timberland’s CEO on Deciding to Engage with Angry Activists

How Jeff Bezos Makes Decisions

High Deductibles Make U.S. Men Less Willing to Be Treated for Health Emergencies

As American employers shift health-care costs onto workers, more have been offering health plans with high deductibles. But those deductibles discourage male patients from seeking treatment, even for serious problems like kidney stones and irregular heartbeats. In the year following a transition to a high-deductible plan, men reduced their emergency-department visits for “high-severity” ailments by 34.4% in comparison with a control group, says a team led by Katy Kozhimannil of the University of Minnesota. Women, by contrast, continued to go to the ED for high-severity ailments, although they reduced low-severity visits.

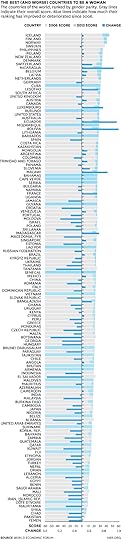

The Best (and Worst) Countries to Be a Woman

The World Economic Forum has just come out with their latest data on global gender equality, and the short version could well be this old Beatles lyric: “I’ve got to admit it’s getting better. A little better, all the time. (It can’t get more worse.)”

I talked with Saadia Zahidi, a Senior Director at the WEF and their Head of Gender Parity and Human Capital. Yes, it’s getting better. Out of the 110 countries they’ve been tracking since 2006, 95 have improved and just 14 have fallen behind (a single country, Sweden, has remained the same). But that’s partly because in some places, there was nowhere to go but up.

And not everyone has improved at the same rates, or for the same reasons.

For instance, in Latin America, several countries surged ahead as more women were elected to political office. That was a trend in Europe, too – much of the improvement in Europe’s scores was due not to women’s increased workforce participation, but instead to the increasingly female face of public leadership. Although those numbers are still very low overall, increasingly women are being appointed (and somewhat more rarely, elected) to public office. “Looking at eight years worth of data, a lot of the changes are coming from the political end of the spectrum, and to some extent the economic one. So much of the [workforce] talent is now female, you would expect the changes to be on the economic front but that’s not what’s happening,” said Zahidi.

And sometimes equality is just another word for poverty. For instance, look at Malawi. They’re one of three sub-Saharan countries where women outstrip men in the workforce, with 85% of women working compared with 80% of men. (The other two are Mozambique and Burundi.) These are low-skilled, low-income professions — just 1% of each gender attends college, and Malawi is one of the world’s poorest countries. This is a bleak contextual picture… and yet Malawi is number one in the world in terms of women’s participation in the labor force.

Then there’s the Philippines. They’re ranked fifth in the world on gender parity because even though they rank 16th the world in terms of the percentage of women working, “the quality of women’s participation is high,” says Zahidi. Women make up 53% of senior leaders, the wage gap is relatively low, and they’ve had a female head of state for 16 out of the last 50 years – which, among other factors, makes them 10th in the world in terms of women’s political empowerment. They’ve also largely closed the gap on health and education. They, too, are a reminder that the WEF’s data tracks gender gaps – not development.

But there are a few lessons to be learned from the wealthy Nordic countries at the top of the heap. “The distance between them and the countries that follow them is starting to grow larger because of the efforts they’ve made,” says Zahidi, crediting their progressive policies on parental leave and childcare as examples of the infrastructure that makes it easier for women to participate in the workforce. When the WEF began doing this survey eight years ago, no countries were cracking the 80% mark in terms of women’s parity with men (where a perfect score is 100%). Now, some countries at the top of the list are up to 86%.

“Change can be much faster – or much slower – depending on the actions taken by leaders.”

I asked Zahidi about the across-the-board improvements. Were countries and companies learning from one another? Or were they each proceeding on their own? “This is not something that there’s generally been a lot of exchange on,” she conceded, “But one of the the things the World Economic Forum is trying to do is create that exchange.” They’ve developed a repository of best practices detailing how other companies and countries have overcome their gender gaps. Nowhere are women fully equal across all the realms the WEF tracks — health, education, the economy, and politics.

“To accelerate change, you need to have that sharing of information between companies,” she says. “Thus far, [progress] may not have been based on information exchange but it will have to be in the future — if we want to avoid reinventing the wheel.”

Where does your own country fit in? Take a look at the graphic below. The thick in the background shows the overall equality score – the 2006 score is in gray, and the 2013 improvement is indicated in light blue. (Countries that worsened or stayed the same are only in gray; countries that were not tracked in 2006 are only blue.) The narrow, darker blue line in the foreground indicates how much the country’s relative ranking has changed in the last seven years. Some countries have surged ahead, pushing other countries down on the list.

October 24, 2013

What the Best Decision Makers Do

Ram Charan, coauthor of Boards that Lead, talks about what he’s learned in three decades of helping executives make tough decisions.

Megastores Want to Be Like Mom-and-Pop Shops… Sort Of

You’d be forgiven for wondering if you’re in the right place the next time you walk into a Whole Foods and see hand-written signs, locally-sourced food, and posters promoting a community fundraiser. Whole Foods and other progressive retailers like Starbucks and Lululemon Athletica are increasingly shedding their national standards and conventions to achieve a more local brand image. Even Walmart, which has epitomized national retailing for so many years, is starting to re-think its chain mentality and now places buyers in the field so they can work closely with local farmers. In the words of its executive vice-president and chief merchandising and marketing officer, “This is really the year of localization.”

These chains seem intent on undoing what national brands have worked so hard to achieve in the nearly 100 years that have passed since the first retail chains were established: consistency of product, brand image, and experience. Chains have grown and thrived because consumers have valued their promise of reliability and familiarity. McDonald’s remains the leading fast food brand in large part because people know what they will get, how they will get it, and how they will feel whenever they visit any of the company’s units.

But independent stores enjoy some important advantages. Now that a baseline of quality at most establishments has been set, value is derived less from consistency and dependability and more from other factors like convenience and local appeal. The infiltration of technology into every part of our lives has made many people seek out personal, low-tech/high-touch experiences and relationships with the companies they patronize. At the same time, connective consumer technologies, sophisticated customer profiling, and targeted predictive modeling have made it easier and less expensive for companies to advertise and connect with customers locally. Independent stores have capitalized on all of these changes.

To protect their advantage, forward-thinking national chains are combining their brand recognition and market penetration with a local approach. But at a global multi-billion dollar chain, that takes more than just sending out an email asking staff to emphasize their local roots. It takes organizational, cultural, and operational changes.

Empowering store managers is the most critical shift. Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz makes it clear to store managers they are responsible for what takes place in their stores. “’Howard Schultz is not going to serve any customers — it’s you,’ is what I tell employees,” he says.

Decentralizing the procurement model and process is another key step, from establishing and enforcing quality standards across a distributed workforce to adjusting accounting and logistics systems to work with smaller suppliers. The goal at Whole Foods is to source 20% of its products from local producers, so the chain’s local “foragers” are tasked with scouring area farms, farmers markets, wholesalers/distributors, and mom and pop shops to curate a product assortment that feeds shoppers’ desires for discovery and authenticity. They often also help their sources to scale production and loan them the capital to do so.

There are other operational considerations. Instead of having one national menu that it can print and publish at scale, Smashburger has to create multiple versions because the chain teams with craft breweries in some markets to offer market-specific beer and burger pairings and tailors the barbecue sauce on its burgers to match local tastes. Company executives are willing to incur the additional costs and complexities because the company’s mission is “to celebrate what local people really want to see as interesting ways to think about burgers,” Founder Tom Ryan explains.

Local store marketing has always played an important role in retail promotion, but in the new indie-inspired model, it becomes the lead strategy. Marketing with a local flair involves advertising through outdoor, mobile, and local media, engaging in local events and supporting local groups, and using local references in messaging and product naming. Inside the store, chalkboards and window painting replace permanent, standard-issue signs. Instead of using traditional customer acquisition tactics, stores rely on becoming community centers by hosting tastings and other special events highlighting local sources.

Rather than one person or centralized team managing brand communication through social channels, responsibility for communicating on a store-level is held at each store. The best practice is to use Twitter handles, Facebook pages, and Pinterest boards for each location. These channels connect local shoppers with topics relevant to the community and to the specific store, in addition to supporting system-wide marketing efforts.

For instance, local marketing at Lululemon Athletica is executed through its brand ambassador program. Local fitness instructors receive the brand’s merchandise, give free classes at its stores, and are featured on large posters on store walls in exchange for providing feedback on the products and spreading the word about Lululemon. Rejecting mass advertising and favoring social media is part of what the company’s senior vice president of brand and community, Laura Klauberg, call its “hyper-local innovative approach” to building its brand.

It’s too early to say whether or not this new movement really works. Most people will probably always retain a fondness for their local mom and pop shop. But by embracing new ways to forge customer bonds while emphasizing consistency and reliability, perhaps national chains can have it both ways.

Empathetic Negotiation Saved My Company

Some years ago, one of our family’s trading companies was staring at ruin. We had ordered a large quantity of electrical fixtures from an Indian supplier for resale to our customers. Based on the supplier’s quotation we had offered a good price and had received plenty of orders. We reported this to the supplier and requested that they begin production as soon as possible.

But a few days later, the Indian supplier informed us that the price of each fixture would have to be almost 40% higher than originally quoted, otherwise they could not execute the order. A price increase on this scale would represent a huge loss for us because we would have to honor the price commitments we had made or tell our customers that we could not, after all, deliver the product, which would entail a tremendous loss of credibility, fatal for a company in a highly competitive business.

Panic set in very quickly. In the course of a long phone dialogue with the R&D Manager of the Indian company our Managing Director lost his temper and made some regrettable and insulting comments about the supplier’s capabilities and business practices. It was clear to me that the situation threatened to get bogged down in name-calling and blaming, which was only making a bad situation worse.

Part of the problem, I figured, was that neither side really had realized the dire consequences of this business on the other. We didn’t appreciate the supplier’s constraints and they didn’t really appreciate the extremely difficult position that their refusal to honor their original offer and the cancellation of this order would put us in with our clients. On the other hand, neither had they grasped the opportunities that the deal represented for them. Achieving this kind of empathy after such a rocky start wasn’t something to be done by telephone and e-mail, so I suggested that my Managing Director and I go to India together.

We spent several days in Mumbai and had a series of challenging but ultimately successful meetings with the Indian company. We began by simply asking, without heat or indignation and, most importantly, in a face saving manner, why they had so abruptly changed the terms of the deal. With some embarrassment they explained that their accounting department had not included in the estimate the cost of all the materials needed.

Now we at least understood the motivation, and with that understanding came the realization that we would not get them to budge unless we could give them a good reason to. As things stood, yes, they had not been very competent but at least they were avoiding a big loss. Our best way forward, therefore, was to show them that while the price increase would save them losses, it would also have very negative consequences for them because there was a strong likelihood that their company would be shut out of the Greek market.

But we didn’t present that as a threat. Instead, we pointed out that if the supplier could show flexibility on its price now, both companies could expand cooperation to other products and services, thus gaining a foothold in the larger European Market. In other words, they could think of this project as an investment in growth rather than as a short-term profitable deal. After four days of meetings and extensive discussions we were finally able to agree on a price only 10% above the initial offer, which meant that we would break even on the deal.

What really made the difference? I think part of the explanation is to be found in the fact that we had made this long and costly trip to visit them. They also appreciated the effort we had made to keep our emotional temperature low and to save their face by avoiding intimidating accusations.

But the main factor for this successful outcome was the fact that we had genuinely tried to put ourselves in their shoes and realized the big financial loss they would suffer. Our arguments for reducing the price back to where it had been were not based on our interests but rather on an objective analysis of the risks and opportunities they faced. Moreover, the fact that we did not actually make a profit at the new price was a face-saver for the Indian company as it further demonstrated that both sides were making a sacrifice.

By focusing on the dire consequences for them of their refusal to fulfill an order they had confirmed rather than on the moral rights or wrongs of us having to bear the financial costs of their mistake, we were able to find a way out of the crisis that both sides could live with. Finally, the connection we had forged with the supplier proved a strong foundation for many profitable and successful deals in the years that followed.

It was not only a crisis avoided, it was also a remarkable illustration of the power of empathy in negotiations.

The Sequestration Cuts that Are Harming Health Care

Between October 1 and 17, the federal government ceased all nonessential operations because of a partisan stalemate over Obamacare. Although it is premature to declare this the greatest example of misgovernance in modern U.S. Congressional history, this impasse ranks highly.

One casualty of the showdown was any consideration of changes to lessen the impact of the across-the-board sequestration cuts that began on March 1. The cuts have caused economic and other distress across the nation, including serious impacts within the health care sector. Nearly eight months into sequestration, we can move beyond predictions and begin to quantify these effects.

Consider the following impacts of sequestration on Federal health agencies and activities:

Cuts to the FY13 budget: $1.71 billion or 5.5%

This includes:

A 5.8% cut to the National Cancer Institute, including 6% to ongoing grants, 6.5% to cancer centers, and 8.5% to existing contracts

A 5.0% cut to National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and a 21.6% drop in new grant awards

Among the effects:

703 fewer new and competing research projects

1,357 fewer research grants in total

750 or 7% fewer patients admitted to NIH Clinical Center

$3 billion in lost economic activity and 20,500 lost jobs

Estimated lost medical and scientific funding in California, Massachusetts, and New York alone of $180, $128, and $104 million respectively.

Dr. Randy Schekman, whose first major grant was from the National Institutes of Health in 1978, said winning this year’s Nobel Prize for Medicine made him reflect on how his original proposal might have fared in today’s depressed funding climate. “It would have been much, much more difficult to get support,” he said. Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.) noted the irony that because of sequester cuts, NIH funding was reduced for the research that resulted in Yale’s James Rothman sharing in the 2013 Nobel Prize for Medicine.

Cuts to 2013 budget: $285 Million or 5%

This includes:

$160 Million in cuts to state, county and local government public health assistance, including $33 million for state and local disaster preparedness.

$40 Million in reductions in HIV prevention activities

$25 Million in funding cuts for global polio, measles, malaria, and pandemic flu reduction efforts and the Strategic National Stockpile

$13 Million in reductions in emerging infection disease response

Among the effects: 175,000 fewer HIV tests

Cuts to 2013 budget: $11.08 billion representing a 2% cut in payments to hospitals, physicians, other medical providers, Medicare Advantage insurance companies, and Part D prescription drug plans.

Among the effects:

Some providers have indicated that payment reductions discourage them from accepting Medicare patients.

Cancer clinics have turned away Medicare patients because of reduced reimbursement for chemotherapy drugs.

Private payers facing cuts to Medicare Advantage and prescription drug plans may impose higher premiums or increase cost sharing.

Some administrative functions, including fraud and abuse and quality oversight, face reductions of more than 2%, raising the possibility of increased program costs and reduced quality of care.

Cuts to 2013 budget: $209 Million or 5%

Among the effects:

Reduced food inspections

Fast track review of new “breakthrough” drugs stalled

In 2012, Congress passed legislation to create a new pathway by which potential “breakthrough” drugs could receive expedited approval, financed by new user fees on the pharmaceutical and medical device industries. The breakthrough drugs are intended for the treatment of life-threatening diseases where “preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over existing therapies.” Though 24 drugs have been classified as breakthrough as a result of the law, sequester cuts have prevented the FDA from hiring scientists to implement the fast-track reviews. Ellen Sigal, founder of Friends of Cancer Research notes that, “Because of sequester cuts, FDA reviewers often cannot even attend major research conferences where data on drugs they will review are presented.”

$472 million in cuts: Environmental Protection Agency delays implementation of monitoring sites for dangerous air pollutants and cuts to grants to state regulators.

$386 million in cuts: Indian Health Services resulting in 3,000 fewer inpatient admissions and 804,000 fewer outpatient visits in tribal hospitals and clinics.

2014 and Beyond

Unless repealed or replaced, sequestration requires $109 billion annually in new federal cuts each year through fiscal year 2021. An important difference in 2014 and beyond is that Congressional appropriators may distribute reductions as they choose, provided that Congress agrees on a budget plan. Without such an agreement, cuts will be across the board, as they have been in FY13.

The new agreement among President Barack Obama and the House and Senate ended the government shutdown and averted debt default until early in 2014. The new continuing resolution deadline — January 15 — was set purposefully, as it’s the date when the 2014 round of sequestration cuts are scheduled to take full effect. Between now and then — less than 90 days — Congress has the opportunity to reconsider the structure and impact of sequestration and avert or minimize continuing damage to the health agencies and programs Americans rely on.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Negotiation Strategies for Doctors — and Hospitals

How to Turn Employees Into Value Shoppers for Health Care

If Everyone Hates the FDA Approval Process, Let’s Fix It

Cutting Costs Without Cutting Corners: Lessons from Banner Health

In Praise of Electronically Monitoring Employees

You might think it’s legitimate and appropriate for management to make sure employees aren’t stealing from the business. Apparently, not everyone agrees.

A little while back, a Steve Lohr post at the New York Times described some research , Dan Snow, and I just finished up and published as an MIT Sloan working paper. We had the chance to study a question that business academics and managers alike have been interested in for a while: what happens to performance when companies suddenly get much better information about employee misbehavior? Our results are fascinating, as is the discussion around them.

The companies we studied were restaurant chains, and the misbehavior was theft: servers, bartenders and managers stealing money. This is a big problem, since restaurants are low-margin businesses where theft by the staff can mean the difference between profit and loss. By one estimate, $200 billion each year is lost in the industry due to stealing.

We got to observe what happened at 392 locations across five chains (all of them sit-down places like Applebee’s or Chili’s, although neither of these were part of the research) both before and after they started using Restaurant Guard, a new piece of theft-detection software from NCR. NCR supplied us with the data but did not support the research in any other way. The data covered almost two years and 39 of the 50 states.

Restaurant Guard generates weekly reports for the management of each location that identify, by employee, all instances of suspicious behavior (the service now also includes instantaneous alerts sent to managers’ mobile phones). ‘Suspicious’ here means ‘really suspicious’ — since the accusation of theft is a serious one, the reports only flag behaviors that that match common scam patterns and are difficult to explain any other way. Some of these are quite elaborate. I don’t want to compromise RG by giving away too many details of how it works; if you want a compendium of restaurant industry deviousness, check out the ‘scam bible’ How to Burn Down the House.

The software works by minutely analyzing every transaction that flows through the restaurants’ point of sale (POS) systems. Since staff have to use POS terminals to get anything and everything done — order food, print a check, process payment, and so on — the systems provides a highly detailed and nearly complete record of all activities. NCR combs through all this data and generates reports and alerts for all Restaurant Guard customers.

What happened once Restaurant Guard was in place? Theft clearly went down, but not by much. The average reduction across our locations was a bit less than $25 per week. The real shock was how much overall performance improved. Weekly revenue increased on average by $2975, or 7% of total revenue. Almost $1000 of this increase came from drinks, where margins are highest and theft is most common.

These are huge increases, enough to make a material difference in the overall profitability of the location. And they didn’t fade away over time; they instead persisted for at least several months after Restaurant Guard was adopted.

Why did overall performance improve so much if obvious theft went down so little? I’ll get to that in a minute. First, I want to highlight some comments made in response to Lohr’s post in the NYT. Many people felt that Restaurant Guard was intrusive, unfair, and/or menacing. Comments included:

“Big (restaurant) Brother is watching you.”

“I can’t believe how many commenters are OK with this practice. Just shows how far towards fascism the right wing has pulled us as a country when spying on employees is considered mainstream.”

Let’s clear this up: Restaurant Guard doesn’t engage in surveillance of employees’ personal electronic communications, or any other activity they might reasonably consider private. Instead, it monitors their on-the-job performance, which is exactly one of the things that managers are supposed to do.

It’s ludicrous to say that employees should be free from all monitoring, so are the commenters above just upset that Restaurant Guard does such a good job of it? Do they want people to have a little wiggle room left for theft? Let’s hope not. I’ve written a great deal about the tough economic times faced by working Americans these days, but giving them license to steal from their places of business is not part of any solution I’ll support.

Now, what about those large revenue increases? Where did they come from? Not from the fact that the thieves left (or got fired) and were replaced by honest people; staff turnover didn’t increase significantly once Restaurant Guard was in place. As far as we can tell, performance improved simply because people started doing their jobs better. To oversimplify a bit, once the bad actors saw that theft was closed off to them as an option they realized that their best way for them to take home more money was to hustle more, take better care of customers, and generally be a better restaurant employee. And I imagine that once some people started acting that way the rest of the staff joined in; good behavior is contagious, just as misbehavior is.

The strongest piece of evidence we have for this explanation is the fact that tip percentage went up significantly after Restaurant Guard was in place. It’s hard to see how this would happen if employees got surly or disgruntled about the increased monitoring. Instead, it looks like they started doing the right thing by their employers and their customers. Isn’t that a story we can all applaud?

Research: The Emotions that Make Marketing Campaigns Go Viral

We’re all well aware of the fact that marketing is shifting from a landscape where marketers can utilize mass media to speak at consumers, to one where marketers are simply part of the crowd themselves. The bullhorn of radio, television, print and other one-way interruptive marketing approaches are quickly losing efficacy. So how do you get your brand noticed?

A recent article by Mitch Joel argues that brands must publish more content, that the old standbys of frequency and repetition that worked so well in decades past are still worthwhile today. Truth be told, he’s right. Publishing more content, even if the content isn’t viral or noteworthy, can be a great way to maintain or even grow existing large audiences.

But what if your brand or company doesn’t have an active audience of avid content consumers already? In this case, piles of mediocre content certainly won’t do the trick. If you don’t already have a large built-in audience, you must attract them from elsewhere. Viral marketing is hands-down one of the best ways to do this.

What Can Viral Marketing Actually Do?

Break through the noise

With 5.3 trillion display ads shown online each year, 400 million tweets sent daily, 144,000 hours of YouTube video uploaded daily, and 4.75 billion pieces of content shared on Facebook every day, posting a few blasé blogs on the corporate website just isn’t going to cut it. You’re going to need something that cuts through the clutter.

Create massive brand exposure and free press

Successful viral campaigns regularly produce 1 million+ impressions, with standouts garnering 10x to 100x that number, often crossing over into the mainstream, and picking up free exposure on television and radio and in print media. For instance, in 2012, the viral campaign “Kony 2012” for the Invisible Children organization garnered nearly 100,000,000 views, and was covered by most mainstream news organizations. The campaign has more than 2,000 results in Google News.

Generate high levels of social engagement, sharing, and brand interaction, which can lead to sharp increases in digital brand advocacy.

When Dove’s Real Beauty sketches campaign went viral, it garnered nearly 30 million views in ten days. Additionally, it single-handedly added more than 15,000 YouTube subscribers to Dove’s channel over the following two months, not to mention substantial increases in followers on Twitter and Facebook as well.

Massively improve organic search rankings

In our own experience at Frac.tl, two successful viral campaigns (Dying to Be Barbie and Before & After Drugs: The Horrors of Methamphetamine) were responsible for very sharp increases in organic search traffic to our client’s site. Viral content contributes significantly to primary signals Google uses as part of its ranking algorithm (authoritative links and social engagement).

This graph of the six-month ranking improvements for our client, Rehabs.com, reflects a 750% increase in site visits as a direct result of these viral campaigns. The hump at the beginning occurred at the launch of the first viral campaign which looked at the before and after images of individuals addicted to methamphetamine, with subsequent campaigns like “Is a Barbie Body Possible,” resulting in the sustained increase.

Increase brand engagement

When users engage with brands via content they choose, rather than content they’re given, they are more engaged with the content and the brand.

How Any Business Can Create Successful Viral Content Marketing Campaigns

Lesson 1: Create a Viral Coefficient > 1

Breaking through the noise and going viral is the direct result having a viral coefficient above 1. For the sake of simplicity, viral coefficient can be thought of as the total number of new viewers generated by one existing viewer. A viral coefficient above 1 means the content has viral growth and is growing, and a coefficient below 1 means that sharing growth is diminishing.

So how do you create content that people will share?

Step 1: Write a compelling title

Your title is what attracts new viewers. The more people you can get to consume your content, the more chances you have for getting people to share it. If you can’t get the initial click, your content is dead in the water.

Step 2: Use strong emotional drivers to make people care and share

As Thales Texeira noted, it is important to create maximal emotional excitement quickly. Hit them hard and fast with strong emotions, but remember to keep the branding to a minimum. Heavy use of branding can cause many viewers to disregard the content as spammy or salesy, resulting in loss of interest, abandonment, or even backlash.

When your content is in video form, be sure to give people an emotional roller coaster. This should be done by “pulsing” the emotionally heavy hitting points in your content with breaks or gaps. It is helpful to think of it as “cleansing of the emotional palate.” By creating contrast between the high levels of emotionality and areas of less emotional activation, the audience won’t find themselves becoming bored, satiated, or overwhelmed with too much of the same.

Step 3: Create content the strikes the correct emotional chords

While there is a good deal of evidence to suggest that strong emotions are key to viral sharing, there are a scarce few that indicate which emotions work best.

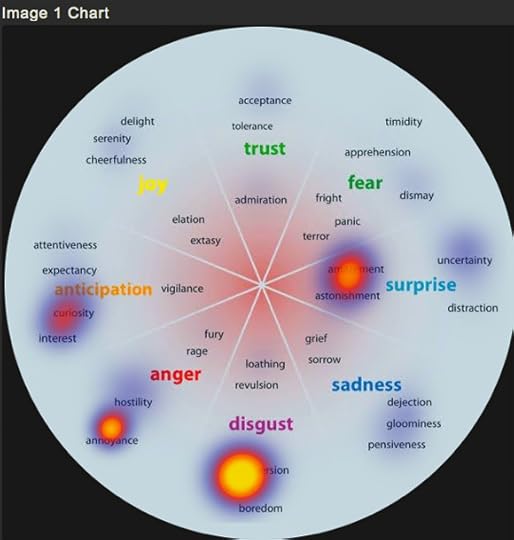

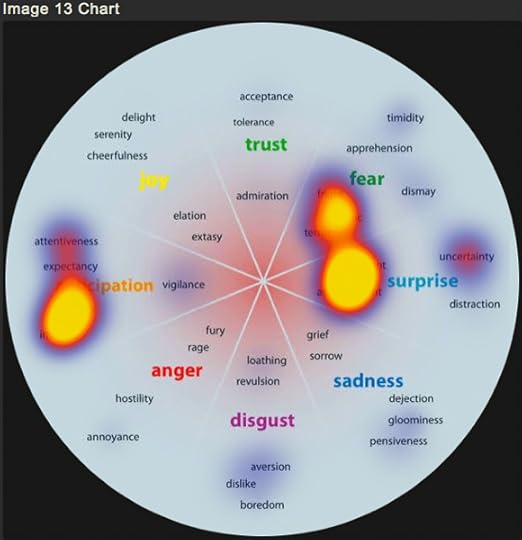

To this end, one of the best ways we’ve found to understand the emotional drivers of viral content is to map the emotions activated by some of the Internet’s most viral content.

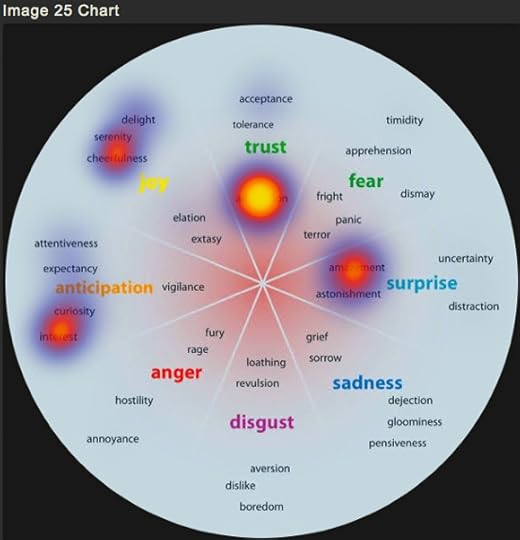

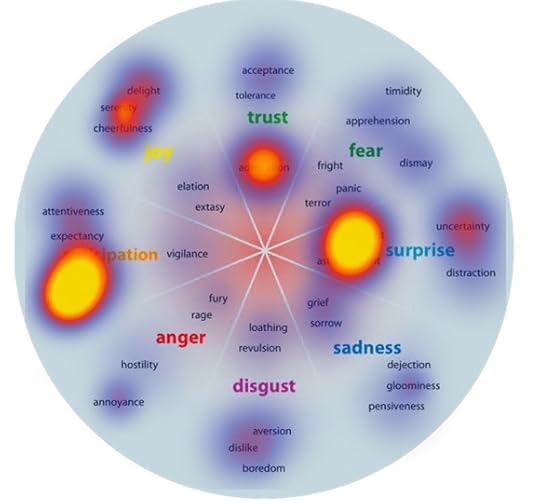

In order to understand the best emotional drivers to use in the content we create, we looked at 30 of the top 100 images of the year from imgur.com as voted on Reddit.com (one of the top sharing sites in the world). We then surveyed 60 viewers to find out which emotions each image activated for them. We used Robert Plutchik’s comprehensive Wheel of Emotion as our categorization. What we found was compelling:

1. Negative emotions were less commonly found in highly viral content than positive emotions, but viral success was still possible when negative emotion also evoked anticipation and surprise.

2. Certain specific emotions were extremely common in highly viral content, while others were extremely uncommon. Emotions that fit into the surprise and anticipation segments of Plutchik’s wheel were overwhelmingly represented. Specifically:

Curiosity

Amazement

Interest

Astonishment

Uncertainty

3. The emotion of admiration was very commonly found in highly shared content, an unexpected result.

Here are a few sample images from the survey (And here are the full results of our research in heatmap form along with their corresponding images.)

Below is a heatmap of the aggregate emotional data, representing the totals compiled.

Lesson 2: Tie Your Brand to an Emotional Message

If strong emotional activation is the key to viral success, how can brands best craft highly emotional messages with their content?

First, think carefully about how your company, product or service is related to a topic or topics that taps into deep-seated human emotions within your target demographic.

The goal is to find the link to an issue that plagues your consumers and relates directly or even tangentially to your brand or product. At the same time, you must make sure that the topic you choose also positively reflects the position of your brand. Using the example of the Dove Face Sketch campaign mentioned above, it is clear that its viral success was the result of its ability to tap into a deep emotional reaction to commonly felt feelings of inadequacy and low self esteem. Dove created a positive emotional reaction by creating solidarity through their campaign. Their content delivered the message “Many women don’t see themselves for how pretty they really are — let’s change that.” Dove’s content engaged strong emotions – even difficult emotions – but managed to win by presenting a more important overarching idea.

Lesson 3: Consider the Public Good

Consider that one of the best ways to create an emotionally compelling piece of viral content that also works well with your brand is to tie your brand to a message for the public good. Brainstorm how your brand might be able to create content that does a public good or that creates awareness, but at the same time activates strong emotional drivers. One excellent recent example was a highly emotionally evocative video campaign from AT&T created to drive awareness for the dangers of texting and driving. AT&T hired famed filmmaker Werner Herzog. The short film has been viewed more than two million times.

Another example comes from a viral ad made for the Metro Trains rail service in Australia. The campaign, titled “Dumb Ways to Die” has created massive awareness through an unexpected, funny, and emotionally jarring video. Since it’s launch, the video has been seen by more than 56 million people. (You can read more about it here.)

To be sure, we are entering an era of marketing that is much more ambiguous, subtle, and not nearly as heavy-handed as it has been in the past. The good news is that there is ample opportunity for those who understand that engaging with audience means touching their hearts and contributing tangibly to their world.

Marketers are no longer in charge of what people see. If you want to get people’s attention, contribute something worthy of consumers’ time and emotional investment.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers