Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1524

October 31, 2013

Stop Paying Entrepreneurs in Lip Service

On an average day, a couple of start-ups will receive their first round of institutional funding in California, Massachusetts, or New York. On that same average day, a number of start-ups will also receive their first round of institutional funding everywhere else in America.

The difference: if you’re an American entrepreneur inside one of the country’s hotbeds of innovation, you’re more likely to succeed.

For policymakers outside of the superhubs hoping to spark a start-up revolution, this is a real problem. While these leaders seem to grasp that entrepreneurship and innovation are the best path to job creation, they’re not doing enough to support the folks who headquarter their businesses outside the superhubs. For the individual entrepreneurs who have a one-in-a-million concept and the skill to execute — the entrepreneur who is willing to risk their income, their reputation, and their existing relationships to relentlessly pursue opportunity — the best option for them is often to get on a plane and build the next growth business in a market where, sadly enough, there already are plenty of existing growth businesses.

Policymakers outside of superhubs need to change that. If you’re asking entrepreneurs, early stage employees, and investors to forgo supercharging their businesses in a superhub, then you need to offset that cost with something else that helps them. In the last article, Max pointed out barriers to entrepreneurship outside of the superhubs along three lines: finding capital, finding talent, and finding the right connections. To make the playing field more level, communities need to solve these problems. But they shouldn’t just stop there — they should explore opportunities to give local entrepreneurs an edge.

The good news for policymakers is that there are already a lot of different experiments going on now to tear down those barriers across the country. Take, for instance, Virginia’s CIT Gap funds. To solve the funding problem, Gap funds makes state dollars available for in state business. Understanding returns will be lower for investors shopping for deals in Virginia, the state invests itself in early rounds for firms committed to staying in state, carrying risk in deals and improving the outlook for later stage investors.

When it comes to attracting talent, Chicago recently launched a technology fellowship to provide financial incentives for young technologists to stay in the city. Municipally funded technology fellowships and other programs like these could do cities a world of benefit in incentivizing local talent to stay local. Similarly, programs that (for example) repay the student debt of engineers who move to your region and work in entrepreneurial firms would help ease one of the hardest problems that most start-ups are facing right now — the engineering talent crunch.

Cities trying to boost their entrepreneurial appeal could take a page from some established entrepreneurial programs. Harvard Business School’s Entrepreneurs-in-Residence program, which brings in folks from around the country to periodically consult with students. They help students test their ideas and, more importantly, provide exposure to professional networks. The Brandery, an accelerator in Cincinnati, also brings in its official mentors from around the country to work with its start-ups — instead of relying on the limited pool of hopefuls from the city. Given the public benefit to having better connected mentorship and investment networks, there’s no reason localities around the country shouldn’t be structuring programs or events to bring in the best mentors, instead of simply settling for the best of what’s around.

Then there’s another route that most policymakers have overlooked. Today, most policy ideas are focused at the company level. The entrepreneur himself is often ignored. It’s a very difficult road for an individual to walk — many who choose to pursue entrepreneurial ambitions do so at great personal risk. They walk away from well-paying jobs. They risk a roof over their head and food on the table. They can lose the ability to provide their families with affordable health care.

Local jurisdictions could step up to deliver a suite of policies to reduce risk for entrepreneurs — cheap health care plans, financial aid for children of entrepreneurs, retirement matching plans — which would give them a distinct edge in terms of not only attracting and retaining entrepreneurial talent, but also in convincing those folks who are on the edge of pursuing their one-in-a-million idea to actually take the plunge.

Many balk at these sorts of recommendations. And we acknowledge they can be hard to pursue from a policy perspective — they’re expensive, they’re risky, and they often require bipartisan support. Skeptics cite public failures like Solyndra and the Loan Guarantee Act. In the realm of entrepreneurship, however, the risk of failure is a necessary condition for success. And if our cities and regions are most concerned with avoiding failure, we will never be able to give local entrepreneurs the platform they need from which to swing for the fences; to try to start the next Google, Tesla, or Square.

A big part of the reason Boston and Silicon Valley look like they do today is because of the investments that the federal government has made since the late 1950s in the SBIC program — which unlocked millions of dollars available for entrepreneurs. Today, the program which provides matching funds for companies investing in small businesses would certainly garner raised eyebrows and push back. But it was effective. And most importantly, it offers our leaders a valuable lesson: building an entrepreneurial ecosystem in your region is possible — but it requires much more than just talk.

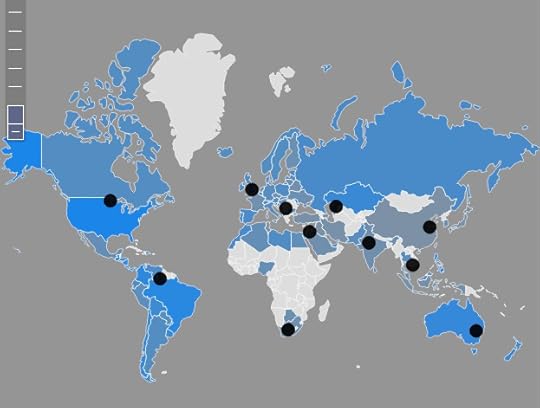

Map: The Sad State of Global Workplace Engagement

Only 13% of employees worldwide are engaged in their jobs, according to 2011-2012 numbers collected by Gallup. What does that mean for where you live and work?

Our map below shows engagement data on the countries polled by Gallup, and includes regional insights into where the problems lie — and how they might be fixed. The numbers only include people who work for an employer, and stretch across industries and sectors. Click here or on the image below to explore the full interactive map.

As you navigate it, some key definitions from Gallup to keep in mind:

“Engaged employees work with passion and feel a profound connection to their company. They drive innovation and move the organization forward.”

“Not engaged employees (we use “unengaged” on our map) are essentially checked out. They’re sleepwalking through their workday putting time — but not energy or passion — into their work.”

“Actively disengaged employees aren’t just unhappy at work; they’re busy acting out their unhappiness. Every day, these workers undermine what their engaged coworkers accomplish.”

For many more insights, download the full report and take a look at our recent roundup of U.S. engagement data.

What to Do When an Online Community Starts to Fail

Success breeds success online. Indeed, if there is one maxim that dominates the fate of digital communities it is that of network effects — the more users participating in a community, the more valuable it will be to new users. As networks like Twitter and Facebook scale, their advantage over nascent platforms becomes seemingly insurmountable. And yet scale is no guarantee of sustainability, as two recent examples illustrate.

In one case, Yelp faces a class action suit by users in California alleging that they deserve to be paid for their contributions, along with allegations by researchers that up to 20 percent of its reviews are fake; in another, MIT Technology Review reports on Wikipedia’s shrinking contributor base and the challenges it faces in attracting new and more diverse editors. These challenges are unlikely to be fatal, but they illustrate the fact that the issues facing mature online communities are both significant and distinct from those faced earlier in their life cycles.

Rewarding Top Users is Important, But Not Enough

Believe it or not, online communities have been the subject of study for at least 20 years at this point, much of which has focused on starting and scaling them. In a 2009 paper examining the life cycle of online communities, researchers Alicia Iriberri and Gondy Leroy of Claremont Graduate University summarize some best practices for communities in the “mature” phase:

Researchers advise that creators and managers facilitate the formation of subgroups, delegate control to volunteer subgroup managers, organize online events, and reward and acknowledge members’ participation and contributions.

This is good advice, but it won’t help Yelp or Wikipedia, both of which helped cement this as best practice in the first place. As the HBS case study on Yelp details, the company’s early success was based in part on the creation of the “Elite Squad,” a user group in the “low thousands” whose active participation was rewarded by invitation to parties in their cities. Similarly, Wikipedia hosts meetups around the world, along with an annual conference.

If catering to existing contributors can’t stem contributor unrest and abandonment, what can? Newer research suggests the key may be knowing when to let certain members go, in order to gain new ones.

Some Community Turnover Is a Good Thing

Contrary to the traditional emphasis on member retention, a 2012 paper by researchers at Boston College suggests that a certain amount of turnover within an online community is a sign of health. They write:

Some turnover may be necessary to allow new members to join. Online communities are not technically limited to a finite size, but people tend not to join once the membership or communication levels are perceived to be too high. Groups that are isolated from outside perspectives can develop biases and insular thinking that leave them susceptible to overconfidence about the group’s ability to collaborate effectively. Thus, some turnover might be necessary to create an influx of unique contributors with new ideas, skills, and information.

The authors test this hypothesis by looking at the likelihood that a Wikipedia entry gains “Featured” status, which is designed to promote the best entries. To approximate community turnover, they look at the average experience of editors who contributed to each entry. They find that there is indeed a sweet spot of experience which beats out entries by both less and more experienced teams. They interpret this as evidence that some degree of turnover translates into better content.

For Yelp, the implication is clear: try to keep your best users happy, but as for the ones so upset that they want to sue you, probably better to let them go. For Wikipedia, the lesson is that editors leaving the community may be an opportunity to bring on new ones, provided they approach it in the right way.

Existing Users Must Help Engage New Ones

The Boston College researchers’ advice for community managers does not bode well for Wikipedia. Managers “should encourage the community to remain open to outsiders,” they write. By contrast, here is Tech Review’s diagnosis of Wikipedia at present:

Since 2007…the likelihood of a new participant’s edit being immediately deleted has steadily climbed. Over the same period, the proportion of those deletions made by automated tools rather than humans grew. Unsurprisingly, the data also indicate that well-intentioned newcomers are far less likely to still be editing Wikipedia two months after their first try.

Compare that to this description of the culture at the community photo site iStockPhoto, as described in a case study by the University of Western Ontario:

The iStockphoto approach to building its collection was unique. Every image submitted was scrutinized by an iStockphoto inspector before being posted to the member-accessible portion of the site. The inspectors, respected members of the iStockphoto contributor community, reviewed the images to ensure they met the company’s standards of content and quality. They approved photos for posting, provided advice on improving images that weren’t accepted and generally mentored contributors new to the stock photo business.

(Emphasis mine.)

Online communities tend to develop a sophisticated set of norms that can serve to discourage new members. (Think hashtags and @-replies on Twitter.) The challenge for community managers is to tie authority within a community to the mentoring of new members, whether formally, through changes in the way the platform calculates authority, or informally, by encouraging established members to lead through example in engaging new ones.

If they take this advice, both Wikipedia and Yelp have their work cut out for them — Wikipedia because of its bureaucratic culture and Yelp because its anti-spam policies tend to marginalize new accounts. But over time both will need to better to balance policies aimed at retention with those aimed at recruitment and mentoring. As in the offline world, communities online can’t underestimate the value of a fresh face.

How to Manage Biased People

By now it’s generally accepted that if senior leaders suffer from cognitive biases their decisions can severely undermine company performance. Yet, leaders are not the only members of organizations that exercise poor judgment: Non-leaders are sometimes irrational too. Bearing this in mind, it is imperative that strategy-setters make explicit allowance for just how cognitively fragile their employees might be – or else they risk not fully understanding why their “perfectly rational” strategies don’t work.

Take the recent case of JC Penney, which hired and abruptly fired its CEO, Ron Johnson, after the major changes he instituted took the company from bad to worse. Johnson’s critics have explicitly accused the former Apple superstar of having suffered from no less than three cognitive disorders during his tenure, including: overconfidence (for failing to test his risky pricing strategy), representativeness (for trying to force the Apple retail model onto JC Penney), and anchoring (for having ignored pricing-related, cognitive biases amongst JC Penney’s customers).

Yet, the workforce that Johnson inherited at JC Penney seemed no less guilty of having their own mental hang-ups, including: defense-attribution bias (for failing to recognize that JC Penney was a sinking ship long before Johnson arrived), Dunning-Kruger effect (for failing to see their roles in making that ship sink), and status-quo bias (for refusing to acknowledge that change was needed). Moreover, in a stunning display of large-scale, bounded rationality, more than 4600 of JC Penney’s head office staff used nearly 35% of the company’s broadband for streaming Youtube during office hours in 2012. In other words, a significant portion of the JC Penney workforce failed to see any connection between their loafing activities and the company’s poor performance.

His own cognitive biases aside, it’s unlikely that any of Johnson’s initiatives would have stuck at JC Penney without first making explicit allowance for the judgment lapses and biased mental dispositions of his new employees. For a firm already in a 6-year slide, how else could he have escaped the associations between his presence and the company’s further decline? By what other means could he have shown how much organizational incompetence was already impeding performance?

Johnson should have directly addressed the biases at the outset, while he forged his strategy. Instead, he fell into the common trap of failing to recognize how organizational biases can derail the execution of that strategy. Perhaps, for example, he felt that firing many of the blatant culprits would solve the problem. It didn’t. Instead, Johnson and new leaders like him need to go deeper into the psyches of lower-level employees. Here are four steps outlining how this might be achieved:

Assess the staff’s personal goals. Let’s be realistic: Having a mission statement too often means very little to low-seniority staff in many organizations. Leaders should recognize that the most common employee goals are more personal in nature: They want job security, good compensation, career progression, etc. Using anonymous surveys, well-structured retreats, and other devices to itemize these goals is an important starting point in overcoming biases that result from misalignment between corporate leaders and the people doing the work. The aim should be to gather a list of the most important goals that characterize what the staff “is thinking about.”

Identify the major bias. Without exhaustively listing the most common employee biases, it suffices to say that the most important one relates to the staff’s misperception of how their goals, their actions, and the company’s strategy are linked. If employees believe that the company’s current direction will ultimately lead to meeting their goals (when it doesn’t) and that a new direction will miss their goals (when it won’t), they will become resistant and inactive and other biases will flow. Hence, the leader must discern, through the examination of those surveys and retreat feedback, whether her staff has an accurate perception of reality.

Lead employees towards logically understanding the fallacies. Once major misperceptions of reality have been identified, it’s vital for you as a leader to publicly demonstrate that those ways of thinking, if accepted and believed, will not lead to the accomplishment of important goals—including those of everyday employees. For example, your staff may highly value job security and defend the status quo; however, if the current strategic direction is leading the company to disaster (as in the pre-Johnson, JC Penney case), as a leader you need to demonstrate the fallacy of the status quo.

Offer an alternative strategy that will still achieve everyone’s goals. Having demonstrated the fallacies, you’re now positioned to win the staff over to your camp in forging, launching, and executing a better strategy. That strategy should aim to meet—in addition to the standard financial and operational performance goals—feasible goals for employees. Where goals are infeasible the leader should explicitly state the reason and logic behind what’s been omitted.

As Ron Johnson learned the hard way, cognitive biases amongst lower-seniority staff can be deadly for even the best of strategies if they go unchecked. But if they’re identified early, executives have a better chance of overcoming them. By demonstrating their potentially negative impacts and transparently offering strategic alternatives to employees, senior leaders can get the buy-in they need and avoid the mistakes of JC Penney’s now-ousted CEO.

Why You Should Make Your First Price Offer Very Specific

It’s well known that you get an advantage by making the first move in a price negotiation: If you’re the seller, for example, and you offer a price before the buyer does, a higher quote from you will lead to a significantly higher agreement price. But you can increase that advantage by stating your offer as a precise, rather than a round, number, says a team led by David D. Loschelder of Saarland University in Germany. In an experiment involving customers in an antique shop, when a 1910 oak writing desk from the Jugendstil period was offered for €1,185, the average agreement price was €1,046.19; if the opening offer was €1,200, the final price was just €929.50 (customers didn’t actually buy the secretaire; they were simply asked to settle on a price).

October 30, 2013

It’s 5 O’Clock. You Should Have Waited Until Now to Buy Your World Series Ticket.

Earlier today, as I was sitting in our Boston-area HBR office debating whether or not to shell out $2,056 (not including beer and other necessary snacks) for a chance to sit in the freezing cold with thousands of my closest friends to watch a bunch of hairy dudes make history, I overheard a colleague admit that he, in fact, has tickets to tonight’s game.

The joy he must have felt, compared to my yearning and awe, is just one of the reasons why the prices for tonight’s game have gone up in the day leading to the game, so much so that tonight’s tickets may be the highest-priced ever. This last-minute increase is a rare phenomenon, according to pricing expert and ticket aficionado Rafi Mohammed. Traditionally, he explained, prices tend to go down in the days leading up to a big game, but there are four factors that make this situation an entirely (excuse the pun) different ballgame:

The first five games have been pretty thrilling, with only one of which ended with a lopsided score. The odds are pretty slim that a boring blowout is in the cards for the Red Sox and Cardinals.

There’s an opportunity to see the Red Sox win the World Series at home, something that hasn’t happened since 1918, giving the high price an additional “historical value” in people’s minds.

The city is just plain excited, and the closer a person can get to that excitement, the better. The social capital of saying “I’m going to the game” at the water cooler is worth a lot.

This is Boston, a city that, despite having won several World Series, hasn’t forgotten its 86-year championship dry spell. And because it’s been a little more than six months since the Boston Marathon bombing, the “Boston Strong” sentiment is deeply felt by much of the city (and the Red Sox themselves).

All of these factors are putting more value in the price of a seat — but many of the people who bought tickets right after game five may have jumped a little too soon.

“People could have been shrewder and could have waited until today to buy,” said Mohammed. “Everyone became very excited after game five, so asking whether or not it’s good price or not wasn’t important — they just wanted to buy a ticket and mitigate risk. But if you wait and can be flexible on seats, you can get in on a lower price.” That’s why, if you feel daring, waiting until a few hours before the game may give you the best deal — indeed, at the time of writing, there are 376 tickets under $2,056 available on the same site that provided the average above.

And if the series extends to a seventh game? Prices may skyrocket even higher due to any extra fun afforded to winning a World Series on Halloween. “Basically, you’ll have to mortgage your house,” Mohammed said, only half, I imagine, in jest. But let’s hope we don’t end up in that situation tomorrow, shall we?

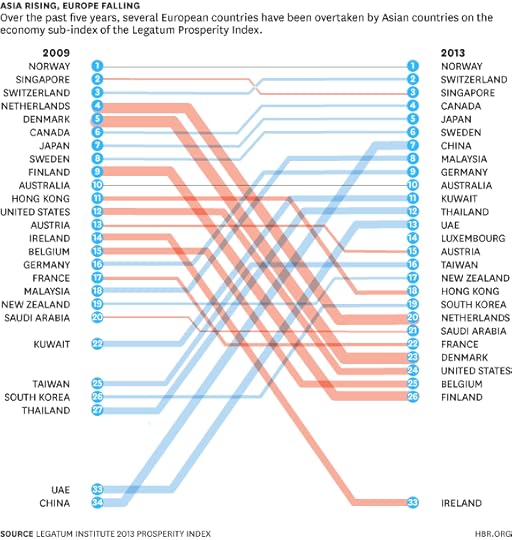

Four Major Changes in Global Prosperity

It was Abraham Maslow who gave us that famous observation — “when the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” We all understand the implication: Anyone attempting to solve an ambiguous problem should start out in possession of a broad set of tools.

It is curious, then, that we continue to fall into the trap of reaching for one dominant tool for measuring the success of nations –- a narrow gauge of economic growth — and believing that the fixes it suggests are the one way to achieve progress.

Of course economic success is important –- most obviously in providing citizens with the things that make life better (healthcare, education, etc.) -– but only up to a point. Wealth alone does not make for a happy and successful society. Measuring success based solely on wealth, therefore, misses the many nuances of human wellbeing. National prosperity should be defined as much by human freedom, sound democracy, vibrant society, and entrepreneurial opportunity as it is by a growing economy.

Over recent years, governments too have increasingly begun to realize that focusing on GDP growth alone does not necessarily lead to improvements in living standards of their citizens. Put simply, what’s good for increasing GDP may not be good for the long-term betterment of society. The outcome of this is the realization that what we measure needs to catch up with what we value.

Over the last seven years, the Legatum Institute has been at the forefront of this “beyond GDP” discussion. Our annual Prosperity Index –- the 2013 edition of which we released yesterday –- measures national prosperity based on eight core pillars that combine “hard” data with survey data. The result is the most comprehensive assessment of national prosperity of its kind.

This year the Prosperity Index offers five consecutive years of comparable data. The world has changed a lot over the last five years, and events have occurred that changed the course of history for millions of people — the financial crisis of 2008, the Arab Spring, and the ongoing civil war in Syria, to name just a few.

In assessing national prosperity, considering trends over five years of data allows us to step back from the twists and turns of specific circumstances and, instead, consider the general direction of travel. And so what do we observe from this vantage point? Here are four observations that stand out.

Global Prosperity is Rising. Despite the tumultuous events of the last five years, global prosperity is actually still on the rise. This is driven by big technological advancements, as more and more people gain access to infrastructure vital for commerce and entrepreneurship to thrive. Also driving global prosperity are huge advancements in global health (especially across sub-Saharan Africa). For example, life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa has risen by more than three years just since 2010.

Latin America is Rising. The Prosperity Index shows that Latin America is a region on the rise, demonstrating steady economic growth. Countries such as Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and Panama perform well on economic measures. In fact, in the last five years, every single country in Latin America and the Caribbean (with the exception of Jamaica) has improved its economic performance in the Index.

Europe’s Loss is Asia’s Gain. The trend from Latin America adds to a wider observation that a new economic order is emerging. As many Western countries – predominantly European countries – have fallen from being among the top-performing economies in the world, they have been replaced at the top by Asian countries. Malaysia, China, and Thailand now rank among the top 15 countries on economic measures, occupying rankings that, five years ago, were held by countries such as Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, and Ireland.

Bangladesh overtakes India. For the first time, Bangladesh has overtaken India, ranking 103rd overall, compared to 106th for India. The two countries have been moving in opposite directions since 2009. India has fallen down the rankings on six of the eight pillars of prosperity, while Bangladesh has improved its position on six of the eight. India has declined most dramatically in Safety & Security, the Economy, and Governance. The data show that Bangladeshis live longer, healthier, and safer lives than their Indian counterparts.

Using a broad framework for measuring success allows for a clear-eyed understanding of the factors that both promote and restrain prosperity. This – to borrow Maslow’s terminology – provides the policymaker with tools beyond just a hammer with which to fix problems.

The path to prosperity for nations is complex. The history of human progress reveals a wide array of factors that combine to propel nations forward on their journey of development. The precise combination and ordering of these elements may be debated and questioned, but the truth remains: national progress – much like human progress – is comprised of a complex blend of different factors.

The Prosperity Index, much like Maslow’s most famous contribution (the hierarchy of needs), attempts to provide a framework to understand and measure some of the most important factors that drive progress and development.

When Making a Big Decision, Think: “Eddie Would Go”

Last month ESPN premiered a documentary as part of its “30 for 30” series. Its subject is Eddie Aikau, the legendary Hawaiian lifeguard, big wave surfer, and ocean explorer.

As someone born and raised in Hawaii, I’ve always admired Aikau. On the beach at Waimea Bay, he gained renown for rescuing more than 500 swimmers in distress. Later, his love for the Hawaiian people and culture prompted him to join the Hokule’a—a bold quest to travel by canoe from Hawaii to Tahiti (a distance of 2,600 miles) using only the stars for navigation. When the Hokule’a capsized in a storm, Aikau attempted to save the crew by paddling solo on his surfboard to the nearest island — 12 miles away — to get help. He was never seen again.

Today the phrase “Eddie Would Go” remains a piece of Hawaiian culture. In my home state you’ll find the saying on bumper stickers and t-shirts. The phrase refers to a particular kind of decision-making — and a willingness to embrace risks and do the right thing, even if it’s a little scary.

Although the comparison may seem incongruous, in my life as a management consultant, the phrase “Eddie Would Go” often comes to mind when I look at the way managers and companies make risky, high-stakes decisions.

The key ingredients for high stakes decision making are facts, faith, and fortitude.

There are numerous instances where we find clients don’t have all the facts. But this is increasingly less frequent. “Knowledge is becoming democratized,” Clayton Christensen, Dina Wang, and Derek van Bever noted in their recent HBR article “Consulting on the Cusp of Disruption.” Increasingly, having the facts is a given, which makes faith and fortitude more important.

Of course, having faith (“I believe in a future opportunity”) and fortitude (“I have the courage and perseverance to see it through”) can be hard. It is not a core competence you can build or acquire. It isn’t something you can easily be trained to have or summon at will. Nor is it necessarily rational. But I don’t think it is only something that you are only born with.

I believe faith and fortitude comes from love. You can call it passion, devotion or zeal — anything you hold dear. Any high stakes decision has an upside and a downside. Faith and fortitude can be defined when your love and passion for the upside are greater than the fear of the downside. Someone is drowning in a torrential river. If you jump in, your life is at risk. If it’s a stranger, you may not jump in. If it’s your sworn enemy, you almost certainly won’t jump. If it’s your child, you won’t hesitate.

It’s the same in business. Do you buy that company? Do you launch that new product? Do you run that risky ad? Do you take prices up? Do you promote that person? There are emotional components to each of these decisions. Often, the difference between a go and no go decision is not about the profits or probability — it’s about passion. The fear of downside is always much clearer and much more real than the potential of the upside. The Innovator’s Dilemma can be expressed as when the love of winning tomorrow is less than the fear of losing today.

As Tina Turner sang, “What’s love got to do with it?” There are at least four kinds of love in business. First, I’ve seen it as a love for a specific consumer group. For example, executives who work in the pet industry tend to love pets and people who love pets. They have a missionary zeal to serve those consumers. Second, great innovators have a love for the art of the possible. They believe discovery is in it of itself a good. Third, brand builders love their brands and react with the swift fury of a mama bear protecting her cub whenever anyone attacks their brand. Finally, for some it is simply a love of winning and keeping score by profits and your stock price.

My observation is that companies and leaders that exhibit the first two kinds of love in business succeed more often in the long-term, because they look forward and outside. The last two loves are inherently a rear-view mirror and navel gazing. And if I had to pick between a missionary vs. a mercenary motivation, I bet on the former to overcome the Innovator’s Dilemma.

Sometimes facts can only point us in the direction. It takes emotion, passion and love to actually jump. Because love makes us do crazy things.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

How Anxiety Can Lead Your Decisions Astray

The Big Lesson from Twelve Good Decisions

When It’s Wise to Offer Volume Discounts

Make Better Decisions by Getting Outside Your Social Bubble

Are You Ready for a Chief Data Officer?

By now, everyone knows that there is huge potential in data. From reducing costs by improving quality, to enriching existing products and services by informationalizing them, to innovating by bringing big data and analytics to bear, data are showing themselves worthy across the board. Still, data do not give up their secrets easily. And most readily admit their organizations are unfit for data.

With all the excitement (and anxiety) surrounding big data and advanced analytics, it is not surprising that many organizations are naming Chief Data Officers (CDO) to manage their data needs. But I fear that too many organizations have sold the title short and are missing the opportunity to define a truly transformative role. You must be ready for a journey that, sooner or later, will touch every department, job, and person.

You don’t need a Chief Data Officer to put basic data management capabilities in place. Too many companies are a full generation behind, and acquiring those capabilities in a hurry may be necessary. But it does not demand a CDO.

You shouldn’t need a CDO to improve regulatory reporting. This is not to say that you don’t need to improve regulatory reporting — simply that it shouldn’t take a true C-band effort to lead the data work needed to do so.

You don’t need a CDO to ensure your IT systems talk to one another. Nor do you need a CDO to help analytics take root throughout the company. Both tasks are important, but they don’t demand a CDO.

A company only needs a Chief Data Officer when it is ready to fully consider how it wishes to compete with data over the long term and start to build the organizational capabilities it will need to do so. You need to be ready to charge him or her with fully exploring what it takes to compete with data. To gain some real end-to-end experience — perhaps making a concerted effort to try out advanced analytics in the hiring process, improve content in financial reporting, bring more data to decisions made by the senior team, and improve the quality of data used in marketing. To conduct enough tightly focused trials, free from the usual day-in, day-out encumbrances, so you can compete in a comprehensive fashion and at lightning speed.

The obvious question, “How do we use data to enhance our existing plans?” is not the critical one. If you’re still asking this, you’re not ready for a CDO. Rather, the most important questions are, “How does data allow us to do things that we’ve not thought we could do?” and “What if a competitor, perhaps one we hadn’t thought of as a competitor before, gets there first?” The distinction here is the ruthless determination to sort out which are part of a company-wide strategy and how they fit with and accelerate other strategies.

It is important to think through organizational implications. Even the most basic data strategy, if well executed, will require new people, new structures, and new thinking. Just consider, if you seek a string of profitable innovations, you probably need data scientists, to set up both a data lab and a data factory, and the stomach to deal with the messiness of innovation. Similarly, becoming data-driven involves the deepest cultural change that is fundamentally incompatible with a command-and-control management style. Silos are the mortal enemies of the data sharing needed to affect this strategy.

You’re only ready for a Chief Data Officer if you’re ready to develop a stone-cold sober evaluation of what it will take to succeed with your selected strategy and make some tough choices. When you expect him or her to drive something like the following:

Building a data-driven culture is probably our best bet. It is consistent with our values. There’s no kidding ourselves — we have a long way to go. Training and hiring are critical, so we need HR to step up its game.

We have to pay a lot of attention to big data. But in today’s environment, we probably cannot attract and retain the PhDs it would take to be on the leading edge. Let’s keep an eye on our competitors, especially the small fry, and partner up with a couple of leading universities and analytics companies. We need to aggressively import ideas from those on the leading edge.

We need to work aggressively on quality. We saved big time in the areas where we focused. People don’t use data they don’t trust. So we can’t be data-driven without it. Our Six Sigma program is decent enough, and our first choice is to leverage that effort for data.

Finally, you’re only ready for a Chief Data Officer when you have the courage to act. Seeing the opportunity that such a statement offers and seizing it are very different things. It’s plain enough that everyone makes decisions, just as everyone creates and uses data and so can impact quality. It will take real courage, over a long period, to drive data into every nook and cranny of the organization.

I’ve argued elsewhere that a full-on data revolution will, in time, change every industry, every company, every department, and every job. So there is some urgency here. Still, for most, when it comes to hiring a Chief Data Officer, “go slow to go fast” is the right approach. Go slow in reserving the title for a long-term, transformative role. You’ll go faster because you’ll not straightjacket your thinking to the issues of the day.

Employee Engagement Drives Health Care Quality and Financial Returns

Hospital systems in the U.S. are at a crisis point. Among the many changes ushered in with the new health care law is the shift to value-based purchasing, which ties a system’s Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements to the quality of the services it provides. For many systems, the mandate will now be to improve clinical processes and ensure a high-quality patient experience — an outcome highly dependent on the commitment, dedication and skills of a hospital’s employees who have an enormous impact on the overall patient experience. In fact, with a potential 2% loss in reimbursements for hospitals that cannot meet specific patient satisfaction and quality of care outcomes, the link from employee actions to patient experience to financial results could not be more direct. Losses amounting to millions of dollars for many hospitals and systems that receive half or more of their funding from government reimbursement are possible. It is, quite literally, a make-or-break moment for financial sustainability.

In other industries, this service-profit chain (first articulated in a classic 1994 Harvard Business Review article and recently updated) has been recognized for decades. Now, hospitals have little choice — and much to gain — from embracing it themselves. As Towers Watson’s research with clients shows, when hospitals create an engaging and high-performance-oriented work experience, they not only improve patient satisfaction, but also quality of care outcomes. Both are core criteria in meeting incentive goals under value-based purchasing.

Currently, however, creating such an experience is a challenge for many hospitals. In Towers Watson’s most recent global workforce study, less than half (44%) of the U.S. hospital workforce overall was highly engaged. That leaves a large proportion of employees across all workforce segments feeling somewhat disconnected from their hospital system and its goals, and unsupported to some extent in doing their jobs well. The study also shows a strong relationship between employees’ level of engagement and their likelihood to remain with their employer, with just 17% of the highly engaged hospital workers interested in other employment options versus 43% of the disengaged group. Improving engagement therefore carries another important advantage for the many hospitals already competing to find and keep a dwindling supply of people with critical skills, especially in clinical areas.

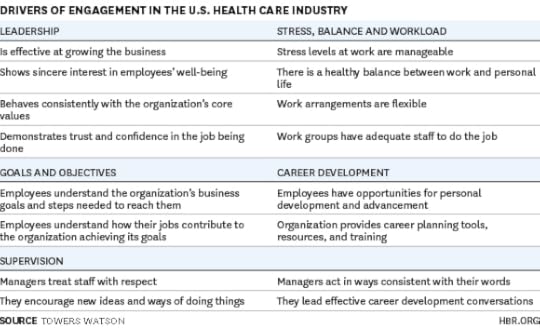

So what can the industry do to raise employee engagement and lay the groundwork for its own service-value chain? First, hospitals need to accurately diagnose the issues through research techniques that measure levels of engagement and identify the specific drivers that affect those levels for different groups within the system. Second, they need to translate those drivers into a set of actions and behaviors that are realistic, meaningful and sustainable. As with medicine itself, diagnosis without corresponding “treatment” will not bring about lasting improvement.

The exhibit below outlines the drivers of an engaging work experience within the health care industry, as derived from Towers Watson’s global workforce study through regression analysis. These broad drivers are, in fact, common to most of our clients across the health care industry. Where critical differences arise is in the way in which each hospital has to institutionalize its own unique set of behaviors and actions across its functions, roles and departments.

A Case in Point

MedStar Health, the largest health care delivery system and one of the largest employers in Maryland and the Washington, D.C. region — with 10 hospitals and more than 100 outpatient clinics and physician offices — offers an excellent example of this process. It set out on a multi-year undertaking to understand and improve employee engagement. A key initial step was to conduct a system-wide engagement survey that collected data on topics from leadership and communication to elements of the patient experience. This latter focus was instrumental in understanding how employees viewed the patient experience and their own role in shaping it.

MedStar leaders also knew that improving employees’ engagement could not be a one-time or one-off activity — or, as one cynic referred to it, the human resources “flavor of the month.” Rather, the leaders had to make decisions that would make an engaging work experience part of the organizational fabric. The health system set a five-year stretch goal for engagement, which was embedded into leaders’ performance management goals at the hospital and department level, ensuring that everyone was pulling in the same direction and held accountable for the same critical behaviors.

One of MedStar’s areas of focus was to assure that the system had strong supervisors who could set clear goals and manage employees to them. To help managers improve their own skills in this area, MedStar launched a four-day training session for more than 2,000 managers. One focus of the session was to bring the entire organization onto a single performance management system. While the organization’s actual employee engagement levels remain confidential, through these two actions — integrating engagement measures into managers’ goals on a unified platform and providing training on how to achieve those goals — MedStar has seen continued improvement year over year and it is well on its way to achieving its five-year goal.

Many hospitals that hear stories like MedStar’s struggle to get approval for the soft-skill development needed to strengthen engagement amid tightening budgets and increased cost scrutiny. One effective approach we’ve found is to first measure engagement, then demonstrate the link between employee engagement and the patient experience, and then lastly tie it to financial returns. While there are dozens of examples of this relationship in industry research, it often doesn’t hit home with a hospital’s leaders until they view it with their own system’s data. We’ve worked with several systems to analyze patient and employee data and validate the link between higher engagement and a better patient experience, and we’ve seen firsthand how powerful that demonstration can be. For instance, by comparing employee attitude data with various organizational metrics from our clients’ systems, we’ve found that when employees believe their organization truly values quality care — and also get the support they need on the job — their patients are more satisfied, they take less sick time and have fewer on–the-job accidents, and health outcomes are better. Much the same dynamic can be seen around quality outcomes. At a large system with hundreds of health care facilities, for instance, we found that units scoring in the top percentiles on positive organizational culture had blood-stream infection rates and mortality rates significantly lower than in units scoring at the bottom percentiles on positive organizational culture.

While improving their technology, creating partnerships across the care continuum, and building Accountable Care Organizations are important pieces of the care-transformation puzzle, administrators can’t forget that patient care is delivered by their employees. Engaging those employees around the behaviors and skills that drive clinical excellence and a positive patient experience is going to be a key factor in determining whether a hospital thrives – or even survives – in this new environment.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Why Can’t U.S. Health Care Costs Be Cut in Half?

Bringing Outside Innovations into Health Care

How to Rehabilitate Medicare’s “Post-Acute” Services

The Sequestration Cuts that Are Harming Health Care

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers