Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1531

October 18, 2013

Cutting Costs Without Cutting Corners: Lessons from Banner Health

Cost cutting is difficult in any industry, but it’s particularly challenging in healthcare, where organizations are simultaneously undergoing a major transformation to improve care and the patient experience. In a hospital setting, cost-reduction is often equated with cutting corners, and so is perceived as antithetical to care providers’ values, and typically creates high levels of employee and patient dissatisfaction. Resetting a health system’s cost structure also implies greater centralization and standardization, which goes against the grain of local facility leaders and clinicians.

There are two keys to successful cost-cutting in healthcare: the first – necessary but not sufficient — is to apply proven tools and tactics from industrial engineering, lean, six sigma, and business process reengineering; the second is to align the initiative with the organization’s mission and culture, and engage clinical and administrative staff across the organization to collaborate in the process. Here’s how Banner Health, one of the nation’s largest health systems, did it. Similar to health systems across the country, during the financial crisis Banner experienced substantial declines in patient volume and reductions in reimbursements amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars. Nonetheless, between 2012 and mid-2103, Banner has captured nearly $70 million in savings, and by 2017, the savings will contribute $256 million annually to its bottom line. The $5 billion nonprofit system achieved this by embracing the following four tenets in a cost reduction approach that is aligned with core values in healthcare—enlisting the empathy, collaboration, and engagement that characterize the best care delivery.

Vision before action

Banner’s leaders made a conscious choice to eschew industry benchmarks in the cost initiative. Rather than setting savings targets based on the performance of other health systems, they set their sights on realizing a 4.4 percent margin within three years on the lowest reimbursement received.

Next, the 10-member senior leadership team used a variety of means, such as town halls, and videos of executives explaining the plan, to clearly and repeatedly communicate the urgent need for cost reduction as a requirement for process redesign across the system that would ultimately improve patient care. This helped squelch rumors of impending layoffs and reduce the stress and fear that inevitably accompany cost cutting.

In making the case for change to its 36,000 employees, Banner’s leadership described how cutting costs would enable the system to invest in new initiatives, such as an accountable care organization and a network of community-based outpatient clinics, which would enable Banner to better coordinate, standardize, and integrate care delivery, eventually improving population health.

Finally, the leadership team, in partnership with Booz & Company, invited people from across the system to collaborate in cost reduction. Instead of imposing cuts and process redesigns from the top down, Banner’s leaders wanted physicians and administrators, practice groups of line managers from different facilities, and department managers and staff to work together to find innovative solutions that would simultaneously enhance patient experience, clinical quality, and financial sustainability. This decision to be inclusive and collaborative was essential to identifying tens of millions of dollars in savings while ensuring support of front-line leaders and staff.

Walk the talk

The team began by attacking the system’s general and administrative (G&A) expenses. By identifying opportunities to fundamentally change how administrative services were delivered, the senior executives led by example and communicated a willingness to do their part in cutting costs by focusing on their own departments first – a messaging that helped dampen organizational resistance to change.

All of Banner’s C-suite leaders served on the leadership team for the G&A project. This ensured their commitment to the effort and created support for tough decisions—even when those decisions directly affected their own bailiwicks. They also set the ground rules that aligned the project to Banner’s values: cost-cutting would be done by empowered, cross-functional teams, whose recommendations would be respected and accepted whenever possible; changes that could negatively affect care delivery or patient experience would be unacceptable; and a soft landing would be provided for any employee whose job was eliminated.

With these rules in place, 8 cross-functional teams—each composed of middle managers, a consultant guide, and a sponsor from the leadership team—were formed. During an intensive 8-week pilot, each team was trained and then it analyzed the cost structure of one function and recommended cost reduction tactics. The pilot culminated in a day-long meeting of the senior leadership in which 123 recommendations were reviewed and 116—valued at $104 to $133 million annually or 18 to 24 percent of Banner’s G&A expense—were approved. Among the approved recommendations were opportunities to save nearly $4 million in HR administrative cost by deploying more self-service technology supported by a shared services organization, nearly $8 million from insourcing second physician reviews of inpatient charts, and up to $3.5 million by creating an internal facility for drug compounding and packaging. By the end of 2012, the first year of implementation, Banner captured $31 million in G&A savings.

Capitalize on success

Banner’s leaders used its G&A success to extend the optimization program to its clinical operations, starting with Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, the system’s flagship teaching hospital in Phoenix. It was also experiencing significant challenges associated with delivering tertiary and quaternary care, its teaching mission, high staff, test, and equipment expenses, all of which contributed to a 10 percent decline in net patient revenue per discharge.

As with the G&A project, a steering committee composed of the facility’s senior leaders was formed. It applied the same ground rules and again cross-functional teams were created. In addition, Banner made a special effort to engage the hospital’s physicians—by including them on the teams and soliciting their ideas through forums. At Banner Good Samaritan, as at any hospital, physicians are key leaders and influencers. Their in-depth knowledge of clinical functions and operations, their ability to drive revenue generation, and the direct effect they have on patient care and quality make it essential that they support and participate in cost reduction efforts.

When the physicians at Banner Good Samaritan began to see how the optimization teams were authorized and encouraged to identify inefficiencies and enhance care delivery and the patient experience, they freely gave their time and worked extra hours with the teams. The results: the optimization program at Banner Good Samaritan identified ways to reduce its cost structure by 15% and in the next 12 months realized $15 million in direct savings.

Banner’s senior leaders expanded on this second success by immediately starting a third project at the Banner North Colorado Medical Center, a community hospital. The optimization teams at Banner North Colorado followed the same process used at Banner Good Samaritan and identified savings opportunities valued at 17 percent of its labor and non-labor cost base and captured more than $13 million in annualized savings in the first year.

Shape the culture

With the potential for step-wise cost reduction established, as well as an approach in which hundreds of team members could be enlisted to generate savings in a variety of settings, Banner’s leaders moved to extend the cost cutting effort across the system. Leadership created an optimization office reporting to the CFO to facilitate cost reduction projects, train new team members, and document and disseminate results across the system. System-level teams were enlisted to share best practices, and in early 2013, Banner launched a system-wide optimization program encompassing all of its 23 acute-care hospitals and healthcare facilities. In scaling the effort, the system began to reshape its culture—creating a mindset of cost consciousness throughout the workforce.

Banner’s approach applies time-honored business cost-cutting methods to clinical settings. More importantly, it tapped into the high levels of integrity, empathy, and engagement among healthcare providers. The result is akin to turning on a light bulb—it releases the energy needed to truly transform the quality and cost of care.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Britain’s Patient-Safety Crisis Holds Lessons for All

An Obstacle to Patient-Centered Care: Poor Supply Systems

India’s Secret to Low-Cost Health Care

Intelligent Redesign of Health Care

Can You Visualize a 3D Object from a Diagram?

High “spatial ability” in adolescence, including the capacity to visualize 3D objects from 2D patterns, is a statistically significant predictor of later creativity in science and technology, says a team led by Harrison J. Kell of Vanderbilt University. In a longitudinal study of intellectually talented American 13-year-olds, spatial ability predicted 7.6% of the variance, 30 years later, in the participants’ likelihood of holding patents and being authors of refereed publications. The findings support the argument that in omitting assessments of spatial ability, SATs and other standard college-admission tests fail to measure a dimension of cognitive ability that has crucial real-world significance, the authors say.

How “Dilbert” Practically Wrote Itself

To mark his contribution to the hallowed halls of management comedy, we’re profiling Dilbert creator, Scott Adams, in this month’s issue of HBR. He was kind enough to lend us his 550-page tome Dilbert 2.0: 20 Years of Dilbert, where he reveals that more than a handful of the comics documented in his legendary workplace strip actually came straight – sometimes verbatim – from his readers’ work-lives, and his own.

Adams started cartooning while working at Pacific Bell Telephone Company (later acquired by AT&T), after being repeatedly passed over for promotion. “The day you realize that your efforts and rewards are not related, it really frees up your calendar,” he says in his book, “I had time for hobbies.” Some of the first Dilbert doodles appeared on the whiteboard in Adams’ cube, and it was one of his coworkers who suggested the name of the title character.

As you may have guessed, the office milieu gave Adams all the material he needed.

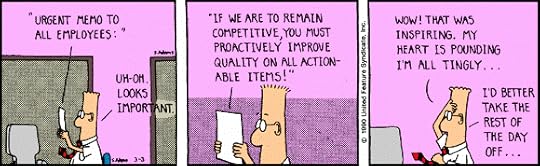

In the early days of Dilbert – March 1990, when the strip appeared only in a few newspapers – Adams included a direct quote from a memo written by the then-VP of engineering at Pacific Bell.

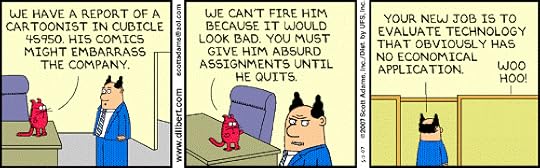

Inevitably, an employee of the VP mocked in the strip shared copies with his staff. But because it would be a strike to morale to fire a popular employee for making jokes, Adams insists that his bosses opted for a different management approach.

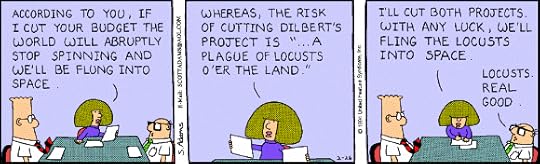

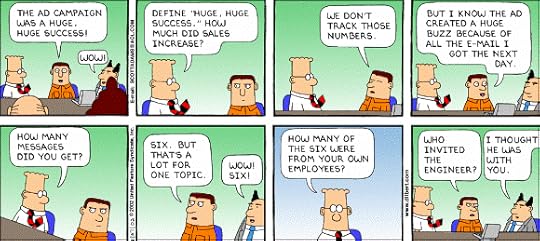

This, of course, backfired. “The more absurd my job got, the funnier my comics became,” the cartoonist mentions in the book. Adams’ boss once sent him to a budget meeting in his place, where he told the meeting leader point-blank that slashing the budget wouldn’t matter “because my project wasn’t terribly important.” The project wasn’t funded, but the experience inspired this cartoon:

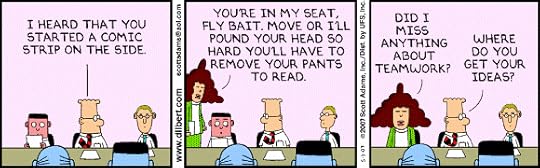

Adams also recounts that he sat in on pretty much the exact meeting below. “I played the part of Dilbert,” he says.

As the strip gained in popularity, reader suggestions started flowing in. One of his most requested themes was that classic corporate IT dilemma of a lost password.

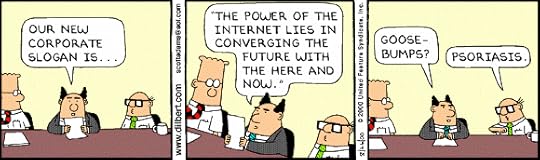

Sometimes he didn’t even have to write any text himself – the following slogan was taken verbatim from a company mission statement:

In the book, Adams reports that “many of the suggestions I get from readers start with, ‘A coworker of mine has this annoying habit.’ No matter how random or obscure that habit is, I always feel like I know that person too.” Like the colleague he calls “the Topper”:

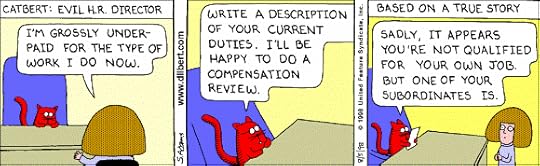

Then there’s the ruthless HR director, who deals lethal blows with a smile:

Or that employee whose sick-day excuses are just barely passing:

Yup, we’ve all been there. And, of course, that’s where Dilbert’s appeal comes from. Scott Adams just made the humdrum funny, and without much exaggeration. “People who haven’t experienced the corporate world surely think I make up this stuff,” he says. But, as those who have been soothed by Dilbert’s workplace satire over the years know: Management truth can be stranger – and funnier – than management fiction.

For more, read the full Life’s Work interview with Scott Adams, or listen to the podcast version: Scott Adams on Whether Management Really Matters.

October 17, 2013

Scott Adams on Whether Management Really Matters

The Dilbert creator talks with HBR senior editor Dan McGinn. For more, read his book How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big: Kind of the Story of My Life.

Don’t Trust Anyone Who Offers You the Answer

Two and a half thousand years ago, the Greek philosopher Socrates was put on trial for corrupting the youth of Athens and failing to respect the gods; he was sentenced to death for those crimes.

The real motivation behind the charges, however, seems to have been that Socrates had exposed broad intellectual corruption among those in power. He was killed because of his concern for truth — by showing that the elites of Athens did not share his concern and that they knew much less than they claimed to know.

A couple weeks ago here in Singapore I met a man who reminded me of Socrates: Nassim Taleb (the author of Black Swan and more recently Anti-Fragile). Socrates exposed his contemporaries’ pretentions to knowledge, and Taleb is serving a similar function today. Taleb, like Socrates, is, I believe, a rare honest man.

The evening I went to hear Taleb speak I fully anticipated that he’d annoy me deeply — that I was just going to hear an obnoxious rant about the pernicious impacts of the modern financial industry, one of his favorite subjects. His writings had often struck me as arrogant, meandering diatribes against caricatures of groups (typically economists, bankers, and business school professors), and I thought I’d hear much of the same that evening.

Instead, I encountered, I believe, a rare honest man, someone who cared more about truth than being liked. It was unusual to hear someone answer the majority of the questions thrown at him with, “I don’t know. How can I know that?” He did rant about business school professors who profess to have answers for everything but who, he claimed, often know very little (disclosure: I’m a business school professor). I was standing right next to him during that one, and felt fortunate for the accident because I agreed with him, and it was nice to hear someone being truthful.

But the business school professors are only partly to blame for their pretensions to knowledge. The people they speak to — their audience — want answers to questions. Responding “I don’t know” is, I believe, too often seen as a sign of incompetence or as a dereliction of duty (to give answers). Our hypothetical business school professors may be giving their audiences what they want but not necessarily what they need. The audience wants answers, but it actually needs truth. (I won’t do bad philosophy here and try to give a definition of “truth.”) And that desired truth may not be available to anyone: even the best, most honest inquiries can conclude inconclusively. That’s a truth, I’d conjecture.

In Plato’s Apology, we are told that Socrates’ friend Chaerephon asked the Delphic Oracle whether Socrates was the wisest man in Athens, and that she responded affirmatively. According to the legend, Socrates found himself confronted with a paradox: he was profoundly ignorant and yet he was the wisest of all men. To try to resolve the paradox, he assigned himself the project of figuring out what the other people in Athens knew. He interrogated statesmen, generals, and other elites, and concluded that, despite their claims to the contrary, they knew very little. Finally, he decided that the Oracle could be right because he knew that he didn’t know much, while the others knew little but thought they knew much. Knowing he was ignorant made him wise.

Socrates is now a respected historical figure whose name nearly everyone reading this post will know. What’s easy to forget is that his story has been passed down through history because he was an honest man who above all knew he didn’t have the answers. In Socrates, we see his self-acknowledged ignorance as a virtue. Strangely, in our current, radically more complex world it seems that we want “experts” always to have the answers. I propose instead that in business, politics and life in general, that we should consider seriously respecting our contemporaries whenever they display Socratic humility and let us know they don’t know.

It may sound like sycophantic hyperbole to say that I saw in Taleb (who, like Socrates, is a squat, solid figure with a bit of a paunch) a modern-day Socrates. He seemed to be a man who values truth more than getting on some Top 10 list or getting shares and likes on social media. Unfortunately, I found his honesty quite rare. I hope he continues to corrupt the youth and disrespect the gods for a very long time.

In the meantime, consider that the person without answers — the one who says, “I don’t know!” — might be the most responsible, respectable person at the meeting table.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Why You Should Crowd-Source Your Toughest Investment Decisions

The Three Decisions You Need to Own

Don’t Make Decisions, Orchestrate Them

How to Minimize Your Biases When Making Decisions

Forget Business Plans; Here’s How to Really Size Up a Startup

If you want to really understand a firm’s strategy—whether it’s a start up or Fortune 500 firm–you need only two documents: the compensation plan and the pricing plan.

Forget about business plans, PowerPoint presentations, executive speeches, media interviews, strategy memos, or org charts. Forget about brochures, YouTube videos, and blogs. Most of that stuff isn’t meaningful—it won’t give you deep insights into the firm’s value proposition and the employee behaviors it really rewards. And in some instances, some of these documents can actually lead you astray and impede your ability to really understand the company.

In my work as an investor, an operating executive at growth companies, a mentor to startups, and a business school lecturer, I’ve come to believe that the quickest way to understand a company’s model is to look at these two documents.

Financial incentives are the key tools used to implement a strategy. How firms incent their employees–especially the sales team—and how they incent their customers and the marketplace are the true effectuation of their strategy. Yes, there’s a lots of managerial research suggesting that there are other motivations besides money that drive employee behavior, and that shoppers are driven by elements beyond pricing. But for most of us, money remains really important, and it’s the factor that’s easiest to observe when judging how well a firm’s strategy will work.

When I am meeting a company for the first time and I ask for the pricing and compensation plan upfront, I often get blank stares. “Don’t you want to see our investor deck or business plan?” the founders will say. Yes, I reply, but later. These two documents are more important.

When I get my hands on these plans, I read them while imagining that I’m an actual employee or customer. If I’m an employee, I ask questions like: Are my earnings capped? Am I incented to be constantly closing deals or delaying until new sales periods? Am I more heavily incentivized to up-sell, to support existing clients, or win new ones? If I’m a customer, I ask: What is this pricing plan encouraging me to do? Am I rewarded for buying more, and if so when? Am I incented to buy one service or product over others, or a combination of products?

When I look over these documents, I’m frequently surprised by how the financial incentives do not align with publicly-stated strategy. Sometimes they’re directly at odds. I am also surprised how often “C” level executives don’t know the details of those plans and can’t explain why they are what they are. In my experience, if the C-suite doesn’t have a deep understanding of how it’s financially motivating employees to behave in ways that create value and exactly how its prices will attract and retain buyers, the company’s story is not going to end well.

Let me offer a few examples.

I remember taking over a large research firm’s sales organization. The stated corporate strategy was to meet the needs of clients by providing world-class research to help support clients’ decision-making process in technology purchases. When I examined the compensation plan, however, it revealed that sales reps could not “make their numbers” (and earn bonuses) unless they had also sold certain quantities of other non-research services. This is the kind of mismatch I look out for when I try to reconcile stated strategy with a comp plan: In this case, selling research was our company’s core strategy, yet the sales staff was incented to divert energy to sell something completely different.

Or consider a B2B software company I know. Its stated strategy was to become ubiquitous, and to leverage their widely-used platform to sell new kinds of software and grow revenue. Yet when you look at the pricing plan, you’ll see it charges a flat rate for each copy of its application, regardless of the identity of the customer. A little research would reveal that customers hated the flat-rate pricing: They complained that there were “power users” and “occasional users,” and that prices should reflect that.

The company made no change in that pricing, and seemed disappointed when its market share topped out at 60%. But if you really understand the pricing problem, you instantly understand the limit to their penetration: The flat-rate pricing meant that clients couldn’t justify offering the software to infrequent users, whose usage wouldn’t provide enough value to warrant the price. Therefore, the company’s pricing didn’t really reflect their strategy of becoming ubiquitous. In fact, their real strategy was to try to boost short-term profits by maintaining margins on incremental sales. This strategy didn’t work our well: Eventually a competitor entered the market and offered an ‘enterprise license’ for unlimited purchases, and within three years the original company’s market share was under 10%.

At Intralinks, where I was CEO in the early 2000s, our team innovated a totally new pricing model to drive rapid adoption. Earlier in the company’s history, it had charged clients a certain fee for every use of our application, plus extra charges based on how much memory or storage each client used. That caused clients to be picky about how many users had access to our application, slowing adoption. We shifted to a model in which we sold a certain “inventory” of usages of our service–say 150, which was then drawn down over time, and then refilled. (Much like pay-as-you-go mobile minutes.) With that simplicity, bookings went up over 600% in the first year and market share reached 72%.

So if you really want to understand what any company is really trying to accomplish, get your hands of the compensation and the pricing plan. The investor deck may tell a carefully-scripted story, but these two documents tell the real truth.

High Stakes Decision Making An HBR Insight Center

Why You Should Crowd-Source Your Toughest Investment Decisions

The Three Decisions You Need to Own

Don’t Make Decisions, Orchestrate Them

How to Minimize Your Biases When Making Decisions

Do Customers Even Care about Your Core Competence?

A provocative—possibly apocryphal—story has the late C.K. Prahalad, the guru of “core competence,” doing a strategy audit for a huge Indian conglomerate. The company, Prahalad tells the CEO, is simply too complex and diverse. It needs to shed a few divisions and find and focus on an integrative core competence. “Actually,” the CEO responded, “we do have a core competence that unites us: we’re very, very good at winning government contracts.”

The fundamental challenge around strategic core competencies today is that too many of them appear designed, debated and deployed from the enterprise-out rather than the customer/client-in. When Prahalad and Hamel published their classic HBR article The Core Competence of the Corporation in 1990, they called out three essential criteria: difficult for competitors to emulate or imitate; reusable throughout the enterprise for enabling products and service; and, last but not least, a contributor to perceived and experienced customer value and benefit.

Unfortunately, the core competence criteria make it too easy for organizational leaders and even entrepreneurs to be more introspective about how they create value for customers than more externally aware of how customers can drive value creation for them. In other words, the focus understandably centers on measurably improving the perceived core competence—selling better, manufacturing better, marketing better, hiring even better talent, cutting costs better. The customer is the ultimate beneficiary of these enhanced core competencies—not the driver or determinant.

So WalMart’s gargantuan core competencies of buying power, supply chain management and logistical superiority guarantee the “everyday low prices” its customers crave and demand. FedEx’s competencies in digital and transportational networks are its innovation platforms. Disney’s core competencies of characters and creative storytelling shape virtually everything it does.

But serious problems of disconnect arise when customers and clients turn out to be more consumers of core competencies than active contributors to them. Who doubts Microsoft’s technical core competencies in software, networking and gaming technologies? But who authentically believes the one-time juggernaut is better understood, better appreciated and better connected to its users? The same is equally and painfully true of Nokia and Blackberry, as well. JC Penney and its failed CEO Ron Johnson had many admirable and effective core retailing and merchandising core competencies. But no one would seriously argue that the company’s efforts were determined by a “customers-in” rather than a perceived “competencies out”approach.

This destructive drift and disconnect are challenges that Web 2.0 companies like Amazon, Google, Twitter, Facebook and Netflix simply don’t have. Why? Because, as Web 2.0 companies, both their strategic and technical architectures are firmly rooted in network effects and real-time feedback. The customer is intrinsically woven into the core competence and the core competence is strengthened and enhanced by increased customer participation.

Incidentally, this holds true even for a quasi-Web 2.0 company like Apple. From the moment Jobs saw the Alto in Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center, he grokked that digital technologies had to be more than beautifully designed devices—they needed to be vehicles for superior UI and UI-User Interfaces and User Experiences. By making design and software subservient to UX, rather than the other way around, Apple’s core competence in design is more accurately described as a core competence in committed user engagement.

Netflix offers a cruder but simpler core competency clarification. Reed Hastings would have been foolish to define Netflix’s core competence as the ability to just-in-time deliver desired DVDs through the mail—even though that was undeniably a core competence for a decade. His company always defined its value proposition from the customer viewing experience in rather than the delivery vehicles out. Core competencies began with the desired and desirable customer experience, not the cultivation of proprietary and/or inimitable internal expertise.

The superficial interpretation would declare this a call for customer-centricity. But it’s not. The real takeaway should be around re-thinking and re-architecting how you can empower customers and clients to add value to your core competencies—however broadly or rigorously defined.

Core competencies should be platforms for customer—and customer-sensitive supplier—collaboration, not proprietary silos of exclusive expertise. How do you get your best or most typical customers to willingly, cheerfully and innovatively re-engineer themselves around your core competencies in ways that enhance both? (This theme is examined in greater depth in my eBook.)

Exploring how to creatively and cost-effectively externalize core competencies is now as much an insurance policy as invitation to innovate. If you’re not making more customers more core to your competencies, you are defaulting to enterprise drift. Give your customers the tools and the opportunity to make your core competencies more valuable to the both of you.

Britain’s Patient-Safety Crisis Holds Lessons for All

In August, Dr. Donald M. Berwick presented the report from the independent National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England (A Promise to Learn — A Commitment to Act: Improving the Safety of Patients in England) to Prime Minister David Cameron in London. The “Berwick Report” reflects on serious problems at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust that arose over several years, and the abysmal care received by patients at the trust’s Stafford Hospital in Stafford, England, during that time. I served on the advisory group, and I’m still asking how a trusted organization could deteriorate so completely without the leaders’ awareness or action? Could it happen elsewhere? How can we, as leaders, prevent these failures in the future?

As the report makes clear from the outset, there are lessons for all leaders in this story. I still see examples of what happened at Mid Staffs in even the best of hospitals. As we in the United States juggle major structural and operational changes and try to secure our financial systems as revenues fall, we must keep our promise of safety and high quality to every patient, every time. I offer three recommendations to ensure that we keep these promises to those who depend on our leadership.

1. Close the gap between the front office and the frontline

The leaders at Mid Staffs were focused on closing substantial financial gaps. This is a familiar and understandable concern and is usually the number one agenda item in many executive offices. But too often, I see leaders focusing on the monthly financials while losing connection to the work and care at the bedside.

Earlier in my career, I had the chance to visit leaders such as Jack Welch (GE), Paul O’Neill (Alcoa), and Ralph Larsen (Johnson & Johnson). Each described a core part of their weekly work as “walks of shame.” They described their regular visits to see the work going on at the frontlines and being both ashamed and humbled when they saw the impediments to quality and the risks to safety. They’d return to their offices inspired to improve processes and remove barriers for the people doing the frontline work. They were committed to listening to the concerns that staff shared, seeing the complicated workarounds that broken processes necessitated, and leading change in order to make quality the priority. They created and maintained a close connection to frontline staff — what Jim Womack, the expert in lean production and thinking, calls “going to gemba” — Japanese for “the actual place.”

At Mid Staffs, instead of this essential connection, there was a yawning gap. When frontline workers raised concerns about staffing levels, experience on the night shifts, and supply shortages, the Mid Staffs leaders walked away from leading. They stayed away from the wards, rebuffing the expert knowledge that could have protected dignity and saved lives. The staff came to work each day filled with anger and desperation and, in many cases, took out their frustration on the helpless patients in their care.

Leaders need to build reliable processes to hear the staff. Some of the best leaders I know have created effective ways to ensure daily interaction among all leaders, caregivers, and patients. Rob Colones, CEO at McLeod Health in Florence, South Carolina, has every senior leader start his or her day by rounding on units and talking with staff and patients. John O’Brien, former CEO at Cambridge Health Alliance and the University of Massachusetts Health System, held monthly breakfast meetings with any staff who had been patients in the system that month or who had family in the hospital. At the breakfasts he asked, “What rules did you break to make your care great?” His agenda became lowering or removing those barriers staff were working around.

2. Ask four questions

On my visits to health care organizations, I often ask these four questions to assess the overall level of quality and to understand how the leaders drive for best performance:

Do you know how good you are?

(I’ll look at the dashboards or other quality reports they use to measure performance. I’ll also ask about the qualitative methods the leaders use to understand the patients’ views on their care.)

Do you know where you stand relative to the best?

(Most often, leaders look at their own performance. But when they know how big the gap between them and the best performers is, they are inspired to change.)

Do you know where the variation exists?

(Most leaders still look at averages and miss the opportunity to build will for improvement by assessing the entire range of performance across various providers and departments.)

Do you know the rate of improvement over time?

(Many leaders overestimate their progress. The data on rates of change over time compel new improvement progress.)

These questions help focus attention on the right things and set the right priorities. They communicate the necessity of understanding quality as a living, changing thing, not as a static metric. And they also impart a healthy dose of competition — the kind that leverages curiosity and pride to generate learning.

3. Build reliable and effective ways to hear the voices of the patients and family members

The Mid Staffs leaders used only basic methods to hear the voice of their patients and family members. The most effective leaders have reliable and vibrant ways to seek out input from patients and families on designs of services, programs, and care models. Effective leadership creates easy ways for patients to offer complaints and reliable processes to respond to patients and resolve the issues. This requires much more from leaders than reviewing survey results. Leaders in the best systems have ways to hear the good and bad outcomes of care, and they have effective systems for improvement.

At Ryhov Hospital in Jönköping, Sweden, patients now administer their own dialysis treatments, in much the same way as we now bank for ourselves at ATMs and fill our own gas tanks. This innovation developed because the frontline staff had strong, trusting, and supportive relationships with the patients they cared for and had strong improvement skills. The mid-level leaders could assess the real effects of personalized care and measure the impact against all aspects of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim: simultaneously improving the health of their population, improving the quality of care they received, and reducing costs per capita. And the senior leaders, having built a culture of patient-centeredness and improvement, could see the potential for new care models in hearing the voice of the patients.

The failures of leadership at Mid Staffs had to do with attention. Their attention was on their finances — understandable and even appropriate these days. But attention isn’t limitless, and faced with financial and business model pressures unlike any we’ve seen, it’s easy to spend too much of it on the wrong things. All of us need to pay attention, in person, to the work at the frontlines. We need to pay attention to our systems for building effective teams to execute on work and improve. And we need to pay attention to creating and maintaining reliable ways to seek, hear, and integrate the voices of our teams, and the voices of our patients.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

An Obstacle to Patient-Centered Care: Poor Supply Systems

India’s Secret to Low-Cost Health Care

Intelligent Redesign of Health Care

Doubts About Pay-for-Performance in Health Care

Simple Food Rituals Increase Enjoyment

People who were induced to follow ritualized behaviors such as stirring and pouring liquid and rapping their knuckles on a desk reported greater enjoyment of subsequent food-consumption experiences, says a team led by Kathleen D. Vohs of the University of Minnesota. For example, those who unwrapped and ate first one half, then the other half, of a chocolate bar rated its flavor as 5.58, on average, on a 1-to-7 scale, versus 5.22 among those who hadn’t followed the simple ritual, and their willingness to pay for the chocolate was 73% higher.

Stop Being Fooled by List Prices

Consumers love a deal. For many of us, a reflexive trigger to purchase is the emotional rush of scoring a big discount. Notice how virtually everyone who buys an engagement ring somehow gets a deal through a “friend of a friend” or a common refrain amongst car salespeople is “I’m not making much off this deal?” Call me a cynic, but my hunch is the sellers did just fine on these transactions.

Clear empirical proof of this “consumers love a deal” axiom is J.C. Penney’s recent pricing debacle. Convinced that consumers were sick of playing the fake discount game, CEO Ron Johnson pledged to stop the madness. Mr. Johnson bet big on a new pricing policy: instead of weekly flyers advertising blow-out discounts, the general merchandise retailer moved to offering low prices every day. Unfortunately for its stockholders, the bet went bad…way bad. Wall Street’s initial enthusiasm over the former Apple executive’s strategy propelled Penney’s stock price to close to $43 (2/12) and then, in great part due to the failure of this new pricing strategy, shares fell to close to $16 by the time of Mr. Johnson’s departure in April 2013. Still unable to reverse this downward spiral, last week Penney’s stock dipped below $8.

What’s interesting is that Penney’s prices were indeed low. Based on an informal price comparison amongst retailers, The Washington Post concluded “Everyday prices at J.C. Penney were comparable to the sale prices at Macy’s and Kohl’s.” Lesson learned: Low prices aren’t enough – consumers need to feel as if they are getting a deal…even if they aren’t.

Offering “deals” is a key pricing strategy for most sellers. Deals fulfill an innate consumer need as well as provide a call to action to purchase (“only available this weekend”). One seller that has based its business strategy on promotional deals is Jos. A. Bank. While “buy 1 at full price and get 2 for free” offers are routinely their norm, the clothier outdid itself last December with a “buy 1, get 7 for free” deal. If you paid full price for one suit, they’d throw in two additional suits, 2 shirts, 2 ties, and an Android phone! Are these deals real? In 2003, then New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer investigated Jos. A. Bank’s pricing policies and found that less than 1% of all sales of suits, trousers, formal wear, and blazers were sold at full price. Note to those who paid full price: I’ve got some swamp land in Florida that would be a perfect winter getaway for you!

You’d think that by offering such generous deals, Jos. A. Bank would barely be making ends meet. Not so. The company reported a healthy 58% gross margin in its last annual report (FY 2012). Lesson learned: offering the appearance of deals is profitable for sellers.

Are list (or original or manufacturer-suggested) prices fraudulent? No – sellers should be able to set (or manufacturers suggest) whatever price they want. What needs to change is how consumers view these prices – which should be with a high degree of skepticism and a clear understanding that these are not what the market has deemed the right prices to be. This can be challenging. In uncertain situations, such as calculating how much a prestigious brand like Hugo Boss is worth, it’s often difficult for consumers to formulate a product valuation. An inflated list price often serves as a reference price that influences one’s estimate of true value. And then, of course, a low discount price elicits a Pavlovian “buy” reaction which seals the deal. An “originally $1,000 but only $400 over the Columbus Day weekend” sale is a powerful sales attractant.

Should original prices that are listed on sales tags be regulated by the government? No – this would be complex to regulate and capitalists should have the freedom to set whatever starting prices they want – remember, a select few paid full price at Jos. A. Bank. But most importantly, let’s not forget the basic concept of caveat emptor – buyers have responsibilities in a transaction too. If public policy makers feel compelled to get involved in this issue, they could require retailers who publish original prices to also provide what the average actual transaction price has been. While I am not in favor of this option, this average selling price would provide a gauge of true market value. But why should companies have to disclose this proprietary data to consumers and rivals?

This “high original but super-discounted today” pricing strategy game is fueled by how customers make purchases. Is this a logical buying decision process? Probably not…but this is how consumers behave. So to prosper, sellers have to master this game and to shop wisely, customers have to temper their primal attraction to “deals.”

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers