Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1536

October 9, 2013

After a Failure, Shame Is Harmful, Guilt Is Productive

Which of these 2 common affective responses to failure was your most salient feeling after your last on-the-job misstep: shame or guilt? If shame, your company is mismanaging employees’ emotional responses to bad outcomes; if guilt, it’s doing the right thing, suggest Vanessa K. Bohns of the University of Waterloo in Canada and Francis J. Flynn of Stanford. By taking such actions as giving you specific feedback and emphasizing the widespread impact of your failures, your boss can minimize shame and maximize guilt, turning you away from despair and disengagement and instilling in you a desire for outward-focused action to redress the source of your guilty feelings.

Get the Right People to Notice Your Ideas

The email arrived the day after a speech I’d given in London. “You’ve definitely given me some food for thought about my career trajectory, and how to use branding to my advantage,” an executive at a management consulting firm wrote. In my talk, I’d emphasized the importance of content creation — blogging, videos, podcasting, or even the creative use Twitter — in enabling professionals to share their ideas and define their brands. “But,” she asked, “what advice do you have for making sure that anything you do is read by the right people?”

It’s a common question: why bother to blog (or use other forms of social media) when it’s so hard to build a following, and you may toil in obscurity for years before finding an audience? Given the seemingly abysmal ROI, isn’t it better to invest your time elsewhere? Indeed, Chris Brogan — now a prominent and successful blogger — revealed that it took him eight years to gain his first 100 subscribers. He was a hobbyist who painstakingly built his fan base over time; most of us simply don’t have the resources or the patience for such a slow-drip strategy.

But despite the fact that you’re unlikely to attract a million readers or “be discovered” overnight, blogging (and its social media brethren) are still a valuable part of professionals’ personal branding arsenal. Here are three strategies I’ve found helpful in ensuring that — sooner or later — the “right people” find out about your work.

The first strategy is to write about the people you’d like to connect with (or the companies you’d like to work for). In a world of Google Alerts, it’s not just large corporations that are monitoring what’s being said about them online. You’re unlikely to get a response from the Lady Gagas of the world, but most executives have lower profiles and are quite reachable. Twitter is particularly useful, especially if you focus on active users with fewer than 5,000 followers. Many top executives fall into this category; it means they’re likely to be paying attention to who is retweeting or messaging them, yet they aren’t overwhelmed by an excessive volume of correspondence. (In fact, proving even my cautionary note wrong, after a recent talk at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, a woman came up to me and said that her friend had created a video that she’d sent to Lady Gaga, who retweeted it and brought it massive exposure.)

Next, consider proactively sharing articles you create. That doesn’t mean spamming people with blast emails touting your latest post, but if a client or colleague asks a question or shares a story that inspires you to write, it’s a great compliment for you to follow up by sending them the piece. Alternately, if someone mentions a business challenge they’re struggling with, it adds to your credibility (and is quite thoughtful) for you to offer to send them a post you’ve written on the matter. And if you’re writing about figures you admire, odds are they’d welcome a quick note from you and a link to the article. (I always make it a point to let talented colleagues like Chris Guillebeau, John Hagel, and Len Schlesinger and his crew know when I’m citing their work.)

Finally, pursue a “ladder strategy” for your content, a concept that author Michael Ellsberg has expounded on. Sure, some people will find your blog accidentally (perhaps through a web search for a particular term), and your friends or colleagues may become early readers. But to build a following over time, start reaching out to fellow bloggers and news outlets that already have a following, and offer to create guest posts. (In my book Reinventing You, I feature finance author Ramit Sethi, who used the technique successfully and has blogged about how to do it.) That will expose new audiences to your work, and perhaps drive them to check out the “home base” at your own blog. It also brands you, as people will associate you with the outlets you write for or the people who have essentially endorsed you by allowing you to guest post. As your following grows, you’re more likely to be discovered by (and impress) “the right people” with your ideas.

As Chris Brogan’s experience shows, it can take years for your readership to grow organically. It’s unlikely that you’ll be “discovered” right away by a top CEO or VC trawling the Internet. But even from Day One, you can begin to reach key players if you’re strategic about the individuals and ideas you cover, proactively share your content (instead of waiting for others to stumble across it), and seek new and bigger outlets to feature your work. Before long, you won’t need to be discovered; the right people will already know who you are.

October 8, 2013

Is Losing Talent Always Bad?

Conventional wisdom might say that the recent departure of Marc Jacobs from Louis Vuitton is terrible news for the company. But if you look a little more closely at the fashion industry you’ll find that turning over your talent isn’t always a bad thing.

Prada is a case in point. Between 2000 and 2010 Prada lost a lot of designers to competing fashion houses, yet its fashion collections were consistently rated as much more creative than the average.

How does that happen? In a recent study (co-authored with Frederic Godart and Kim Claes) I found that when a designer leaves a fashion house to work for competition, he or she tends to stay in touch with friends and former colleagues from the old job. These ties act as communication bridges through which former colleagues can learn what the departed designer is up to in the new job. And when several designers leave to work for different fashion houses, the colleagues staying behind build bridges to lots of companies. This provides them with a lot of creative input for their future collections.

The phenomenon is not confined to fashion. McKinsey consultants famously stay in touch with former colleagues, who have left to to work for other firms, most of which are potential customers. The same thing happens in Silicon Valley where people change jobs across customers and competitors. To be sure, we are not talking about industrial espionage here. The positive effects of communication bridges on creativity come from friends catching up with friends in very general terms about what is going on in their professional lives.

Fashion houses that benefit the most from talent turnover also have long serving creative directors who mentor and befriend the new hires. At Prada, this is Miuccia Prada, who has a long tenure as the company’s creative director.

Prada (the company) gets infusions of fresh ideas every time it hires a new colleague. Prada (the designer) welcomes and helps train the newcomers. When a designer eventually leaves to work elsewhere, after a fruitful stint at Prada, she remains on good terms with former colleagues, spreading the message throughout the industry that Prada is a great place to work and learn. These positive tendencies are reinforced by a culture of transparency and collaboration in the company, as described by CEO Patricio Bertelli in an HBR article.

The messages to the non-fashion world are clear. Don’t part with former employees on bad terms and don’t forget about them. Stay in touch with them as they are your communication channels and ambassadors in the industry. Replace them with talent from different companies to preserve diversity of ideas inside your firm. And make sure senior executives take time to train and socialize the new hires.

Now every time we see someone wearing Prada, let’s think not only about the fashion, but also of the management lessons that we can learn from this company.

It’s Time for Episode-Based Health Care Spending

There is widespread agreement that if the United States is to achieve sustainable levels of health care spending, it must make greater use of payment mechanisms that reward physicians, hospitals, and health systems for the results achieved. The vexing question is how best to make this transition.

Today, payers and providers are using a range of strategies to accomplish this goal, including patient-centered medical homes, value-based contracting, and accountable care organizations (ACOs). We applaud this trend. However, our research and experience have convinced us that the transition to outcomes-based payment will occur more easily if both payers and providers take an intermediate step and make greater use of retrospective episode-based payment (REBP).

REBP focuses on “episodes of care” (any clinical situations that have relatively predictable start and end points such as procedures, hospitalizations, acute outpatient care, and some treatments for cancer and behavioral health conditions). REBP identifies which provider is in the best position to affect the clinical outcomes and total costs associated with an episode of care; it then assesses (through retrospective analysis of claims data) the outcomes achieved and costs incurred during each episode over a specific period of time (e.g., quarterly). The identified providers are then rewarded or penalized based on their average performance across all the episodes.

The desire to jump straight to outcomes-based payment models focused on the total cost of care for an entire population has led many payers and providers to overlook, or give up on, episode-based payment. We believe it is worth reconsidering.

The Advantages

REBP offers a number of advantages. For example, because it uses the current fee-for-services claims system as its administrative platform, it does not require providers to make significant investments in new infrastructure or establish new contractual arrangements with other providers. And because it focuses on acute episodes, REBP acts as a necessary complement to payment and care-delivery models designed to improve prevention and chronic-care management. Furthermore, administering and/or participating in an REBP model can help both payers and providers develop many of the capabilities they will need for total-cost-of-care management. In short, REBP can serve as a bridge to more comprehensive total-cost-of-care approaches.

How Does REPB Work?

In the U.S. health system today, a dozen or more providers may be involved in an episode of care, and each provider typically bills separately. None of these providers is rewarded financially for helping ensure that the desired clinical outcome is delivered with the highest quality at lowest cost across the entire episode.

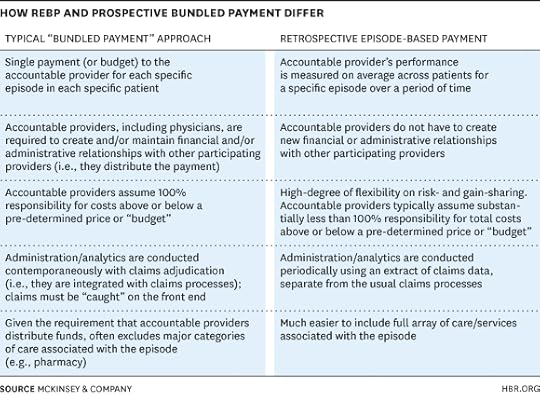

REBP is designed to change that. It is somewhat similar to and shares many of the same goals as the “prospective bundled payment” approach, which calls for making a single payment (or budget) to the accountable provider for all the services used to treat each specific episode for each specific patient. But key differences in design and administration make REBP more scalable in the current U.S. health system.

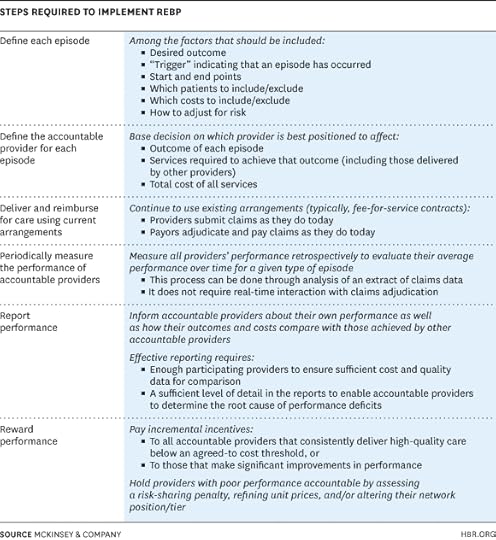

The six core steps required to implement REBP are listed in the exhibit “Steps Required to Implement REPB.”

Why Should Payers Pursue REBP?

Our analysis of data from private insurers, Medicaid, and Medicare suggests that 50% to 70% of all health care spending could be included within episodes of care. REBP establishes end-to-end accountability for more than half that spending.

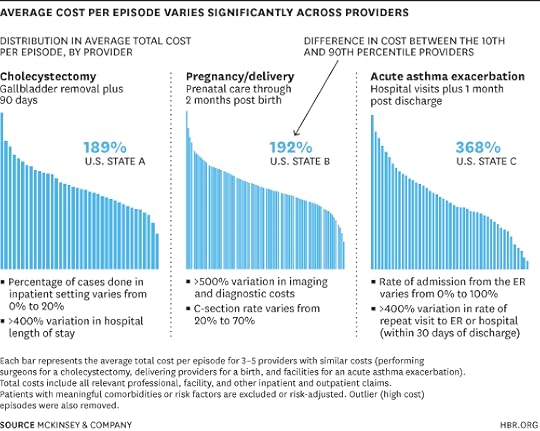

REBP also gives payers a direct way to incentivize providers to reduce health care waste. We have consistently observed that some providers deliver the same or better clinical outcomes at dramatically lower costs than other providers in the same market. The exhibit “Average Cost Per Episode Varies Significantly Across Providers” illustrates variations in average, total per-patient costs for three different episodes in three different states. Even after we excluded patients with certain complicated conditions and adjusted for patient severity, the average cost per episode in each market still varied from 60% to over 300%. Further analysis showed that much of this variation could be explained by differences in practice patterns (e.g., decisions about device selection, diagnostics use, discharge planning, hospital admission).

REBP also offers a quick path forward, because it requires only modest additional infrastructure. We have seen multiple payers define and implement the necessary infrastructure within six months of when they agreed on an episode’s definition. Turnkey analytic vendors are also beginning to emerge.

In addition, REBP gives payers considerable strategic flexibility. Many REBP parameters can be adapted to address local conditions, align with network and member-engagement approaches, and strengthen competitive advantage. Among these parameters are cost thresholds, stop-loss provisions, the degree of gain- and risk-sharing, whether and how to normalize unit prices, and whether to steer members to certain providers.

Finally, REBP gives payers a way to prepare for the future, when episode-based performance management is likely to be a required capability. Most providers do not have access to sufficient claims data to assess performance on their own. If providers are to accept partial or total cost-of-care accountability, payers will need to offer them a performance-management infrastructure to understand clinical outcomes and costs.

Why Should Providers Pursue REBP?

If contractual terms are fair, REBP can deliver meaningful value to acute-care providers in particular. For example, it has the potential to give them a net increase in margin, because many of the sources of savings are either variable costs to these providers (e.g., implantable devices, extra care required for surgical complications) or are associated with upstream or downstream providers (e.g., pharmaceuticals, physical therapy, skilled nursing facility care). REBP can also help acute-care providers reinforce and accelerate existing strategic priorities, such as improving how hospitals influence and partner with physicians, increase adoption of clinical pathways, and reduce input costs.

REBP empowers all accountable providers by reducing the need for payers to monitor clinical decision making (e.g., through preauthorization). It also positions them to assume a stronger role in influencing the performance of upstream and downstream providers.

Strong episode performance has the potential to strengthen a provider’s value proposition to patients, employers, and payers. It may also be grounds for negotiating a stronger network position.

Furthermore, REBP requires providers to make only small, if any, investments in new infrastructure — at least initially. And it will enable them to strengthen their ability to understand end-to-end performance, a capability any providers considering more holistic total-cost-of-care payment models will need.

What Changes Must Payers Make?

To implement REBP at scale, most payers will have to shift their focus from prospective to retrospective models in most markets. Doing so will enable payers to simplify their infrastructure and focus on analytic processes that are separate from claims adjudication. This infrastructure is less invasive, requires less investment, and offers faster time-to-market than do solutions that necessitate material changes to claims-adjudication processes.

Second, payers will need to develop greater technical sophistication to ensure fairness (e.g., through episode-specific risk adjustments) and provider acceptance. They will also have to develop or adopt new standards as they emerge. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s efforts to create standard episode definitions, including through the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative, are a promising starting point.)

Finally, if REBP is to succeed, payers will have to implement it at scale by promoting REBP, whenever possible, across all books of business and all network providers. Most payers should also strongly consider participating in multi-payer efforts to set standards to help overcome common barriers to implementation.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

A Global Online Network Lets Health Professionals Share Expertise

How to Design a Bundled Payment Around Value

Providing High-Quality Health Care to Americans Should Trump Politics

What Gets Measured in Education

The world over, the performance of colleges is under fire. It’s about time that happened, but there should also be serious concerns about the new report cards that are being fashioned for tertiary educational institutions.

The Obama Administration in the U.S., for instance, plans to create a new performance-based rating system with teeth. In future, it says, resources will flow only where tangible student-focused outcomes justify their deployment. Those outcomes will be, most likely, improved retention and graduation rates; fewer wasted credits; lower student debt-burdens; easier access to financial support; greater efficiency estimated by linking progress to degrees and demonstrations of competency, not to credit hours or seat times; more students hired within a reasonable period after graduation; higher salary levels for them; and so on.

Are these useful measures? Of course. Will tracking them prove helpful to college managements? Of course. Will knowing them be relevant to students and families? Of course.

But these are not measures of educational performance; these measure only the efficiency of the educational process. Think, for a moment, of a college as if it were a factory, a pipeline that takes in raw materials and puts them through a structured series of steps that leads to the creation of “finished products,” namely well-educated students. The measurements under discussion are yardsticks of the pipeline’s asset utilization and process efficiency levels. If we improve them, the “factory” will run better.

However, if colleges use only these metrics to evaluate their performance, they will continue to repeat past errors. For, they will be measuring virtually everything except the one thing that matters most: Student learning.

Nonsense, will be the predictable rebuttal; colleges already measure learning. What do you think grades indicate? What do you think degrees stand for? What do you think the Latin on a diploma signals?

Even if you believe that colleges grade, certify, and award degrees accurately, there are grave limitations to the way they do it. Their measurements primarily reward discipline-based knowledge — not the capabilities in critical thinking, analytic reasoning, communication skills, and interpersonal effectiveness that employers most care about and that are essential for students to succeed as adults in the real world.

Research shows that there are links between traditional academic performance and economic status. For instance, students with the advantages that prepare them to test well at one level tend to test well at other levels too. So the fact that students are performing well according to standard measures may have little, if anything, to do with a college’s learning-related performance. It may just have a great admissions office and a powerful brand, taking in talented kids through the front door and not messing them up.

Meanwhile, two great ironies are unfolding. One, while the accuracy of traditional grading stagnates, the ability to carry out true learning-related assessments has advanced with lightning speed. Improvements in the U.S. Collegiate Learning Assessment; the skills-and-employability assessment instruments pioneered by organizations such as Aspiring Minds in India; the algorithms used to track learning in online video games; the analytics that underlie the learning experiences offered by massive open online courses; and US Education Testing Services’ new proficiency profiles and skills instruments are all changing what assessments can lead to. (That’s a topic I will revisit in my next post.)

Two, this is also a time when corporations and executives can help create the outcomes they desire as long as they don’t focus only on helping colleges to boost process efficiency or re-shape curriculums. The corporate world knows a lot about how to evaluate the kinds of learning that matter to it. It’s time business shared that expertise with colleges, and joined them in efforts to build novel tools that will help measure students’ real learning performances.

As a Leader, Create a Culture of Sponsorship

Sexual tension will always exist in the workplace. Affairs happen, and where there’s even the possibility of sex, there’s gossip.

Sex — or the specter of it — haunts sponsorship, prompting men and women to avoid the professional partnerships necessary to achieve their career goals for fear of being censured, fired, or sued. My research shows that 64% of senior men (vice president and above) and 50% of up-and-coming women admit they’re hesitant to initiate any sort of one-on-one with each other lest their motives be misconstrued by their colleagues and rumors start poisoning the workplace. When affairs — or even the perception of one — are present, 70% of women surveyed say the junior female disproportionately bears the brunt, and 53% of male respondents agree. Her career trajectory changes, either because she requests a new position or one is forced upon her. And her reputation takes a dive from which it may never recover.

But while women need to consider the challenges posed by sex, scandal, or innuendo, the responsibility for keeping the relationship safe shouldn’t rest solely on their shoulders. If sponsorship is a two-way street, then keeping that street clear of career-wrecking garbage demands participation from both parties. As a sponsor, you must telegraph relentless professionalism, meet openly, and keep spouses and children literally in the picture.

But as a senior executive with the power to influence or set policy, you do have the wherewithal to make sponsorship safe — by changing the organizational culture in which it’s exercised.

Mandate. In a corporate culture where sponsorship is the norm, close working relationships between senior men and women take on a normality that defies gossip. At Credit Suisse, for example, sponsorship is a company-wide mission supported by senior management. Established by CEO Brady Dougan, Mentoring Advisory Groups (MAG) task a select group of high-potential women with solving business challenges articulated by members of the executive committee, who act as sponsors. Over 18 months, teams of six protégées, two executive board members, and an executive “champion” tackle a critical-to-mission business challenge the firm has identified. Meeting regularly — by phone, email, teleconference, and in person — not only drives the core value proposition but regularizes the one-on-one relationships.

Educate. Become a sponsor evangelist. Spread the gospel to your peers. Enlist the help of HR. Embed sponsorship education into leadership development. “Our goal is to make sure everyone knows what sponsorship is, how it works, who does what, and why it’s important to the success of this firm,” says Keisha Smith, who spearheaded a company-wide program to educate VPs, executives, directors, and managing directors at Morgan Stanley.

Make it matter. Ensure that performance reviews assess sponsorship as a measure of leadership readiness. Again, by making sponsorship a must-have, you’ll swivel a spotlight on every attempt to grow it — nurturing healthy growth while eliminating the dark corners where illicit liaisons are perceived to take root.

Publicize policies. It’s not enough to have corporate policies in place governing sexual harassment or office liaisons. Well-crafted policies deter detrimental behaviors only to the degree that people know about them — and, as I discovered, people don’t know about them: 43% of men and 46% of women don’t know whether their company has a policy on office romance, and 37% of men and 38% percent of women don’t know whether their company prohibits relationships between manager and subordinate.

Push for punishment. There’s often a troubling disconnect between what companies think they are doing to address the problem of sex in the workplace and what they’ve actually accomplished. Policies that are less than airtight or are enforced differentially send a message that some employees are valued more than others and can be excused from punishment should they overstep. At the end of the day, how serious a company is about punishing its offenders says a lot about its culture. “It’s very important [that] a firm’s policies are in line with its overarching mission,” says Annalisa Jenkins, executive vice president of Merck Serono. “If you want to drive equality of opportunity and drive the notion of justice in your organization, you cannot be vague in terms of how you handle these transgressions. The tighter the policy, the more women benefit.”

Sponsors need protégés as much as protégés need sponsors. For the relationship to succeed, it’s incumbent on those in power to use their influence to create a safe environment for sponsorship for all parties involved.

When You’re Innovating, Think Inside the Box

A company noticed a strange anomaly: One of its manufacturing plants had a significantly lower scrap rate. That little finding and its consequences illustrate a point that managers often overlook in their search for innovation: Sometimes it’s better to think inside the box.

Companies spend a lot of time and effort trying to adapt ideas from other industries and other disciplines, but I would guess there’s at least one idea lurking within your own company that you could use to great advantage. That’s why I say think inside the box – the box being your organization. Of course, if there’s a great idea, it’s probably hidden away inside the corporate maze.

That was the case with the company that noticed the lower scrap rate. A lower scrap rate implies a more-efficient manufacturing process. But what was the plant doing differently? Corporate managers went out to take a look.

They found that an engineer at the division, which did injection molding, had developed a way of preprocessing the plastic pellets so that when they were fed into the system, they flowed more smoothly. The machines didn’t have to be cleaned as frequently, and there was less scrap.

The innovation had been applied to most of the machines at the plant, but not beyond. Why? Because the division’s managers hadn’t seen the idea as all that special. It was such a simple improvement – it required just a small amount of inexpensive equipment – that it wasn’t even big enough to be called a “project.” Companywide dissemination of the idea turned out to be easy, and the entire corporation benefited.

Very few companies have cultures that promote dissemination of good ideas. Instead, there are barriers everywhere. Plant managers are too busy to think about other plants’ needs. Divisions that are competing for scarce resources hoard their advantageous ideas. Engineers in one country don’t communicate well with their colleagues in another.

So the reality is you have to go prospecting for ideas within your own company. Here are a few best practices:

Look for anomalies. If your company keeps business-unit dashboards, look for data showing 2X differences. If your unit has a 4% customer-complaint rate, for example, look for a unit with a 2% rate. Why is your group’s rate 2X the other group’s? They’re probably using a different process. Find out what they’re doing right.

Build relationships. Managers typically despise organizationwide meetings, seeing them as time sinks. But don’t be so quick to try to get out of meetings with people from other divisions. Once you get to know them, you can ask: “By the way, how do you handle this or that?” Or “Can I swap engineers with you?” Pretty soon, the ideas will start flowing.

Study acquired companies. After making an acquisition, companies have a tendency to tell their new subsidiaries: “Do it our way.” But before that change happens, look at what the acquired company does well, and find out their M.O. – it might be better than your company’s way.

Study suppliers. Companies that supply to your company can be sources of ideas, either because they do certain things well or they have capabilities you aren’t tapping into. For example, a company that was buying standard printed-circuit boards discovered by chance that they came with wifi capability, a feature that the purchaser hadn’t requested. A circuit board with wifi can send information about the product, such as that a particular component is wearing out. The purchasing company made use of this previously unsuspected capability to offer its customers a component-monitoring service at a higher price point.

Push for a more open culture. I’m always surprised at how many companies don’t publish their measures internally. Try to persuade your company to institutionalize the exchange of information. One company I’m familiar with has developed a culture of best-practice sharing. During the annual budgeting process, each operating division is required to cite two best practices it implemented in the past year. The company also regularly moves managers among divisions to spread knowledge.

Of course, some ways of disseminating knowledge are more effective than others. A lot of companies today use online knowledge-sharing systems. Those can work well, but only if the person who “owns” and manages the system is a subject-matter expert, rather than an IT person whose main role is to keep the server running. A subject-matter expert who is assigned to ensuring that the site is full of ideas can make the difference between a useless and useful system.

It’s often said that one factor hampering people’s ability to learn is that they don’t know what they don’t know. Companies have a different problem: They typically don’t know what they do know. In the quest for ideas, make sure you take time to investigate the innovation that’s happening in remote corners of your own organization.

Executing on Innovation

An HBR Insight Center

How Good Management Stifles Breakthrough Innovation

Capturing the Innovation Mind-Set at Bally Technologies

Good News, Bad News: An HBR Management Puzzle on Innovation Execution

Why Conformists Are a Key to Successful Innovation

Consultants Should All Get Real Jobs

I challenge all consultants to spend some time — at least a year — back in a “real” job, working shoulder to shoulder with the same kinds of people who pay for their advice. So few authors and experts are willing to do this, because they’re afraid. They know it’s much harder to be accountable for a real team, in a real company, for a real project, than it is to critique and advise from the safety of the sidelines.

In 2010, I decided I was guilty of this shortcoming myself. Though I had written three books, a decade had gone by since I’d managed a team or built a product. I had reached the point where no matter how many companies I visited or books I wrote, I couldn’t be sure how much of my advice was good anymore.

How could I advise others on things I hadn’t done in years? Where was my integrity? The only solution was to take off my expert hat for a time and return to a real job. I dropped my commitments for writing and speaking engagements and went back to work with three goals in mind: (1) Learn firsthand how the working world had changed, (2) take a true test of my abilities, in the present day, and (3) discover how much I actually followed the advice I had preached.

From 2010 to 2012 I worked as a team leader for WordPress.com, the 8th most popular website in the U.S. As I describe in my recent book The Year Without Pants: WordPress.com & The Future of Work, it was one of the most amazing and challenging experiences in my entire career. My deepest assumptions were tested and I was forced to reconsider my thoughts on management, leadership, innovation, and more. WordPress.com itself introduced me to ideas about work I’d never experienced firsthand – from how they’ve escaped email overload, to the unusual and often brilliant methods at the heart of the highly productive and passionate culture they’ve cultivated.

As for my three specific goals, they can also serve as a road map for other consultants who are interested to stop teaching and start doing:

Learn for yourself how the working world has changed. It’s well-known that most business people work primarily online today, with laptops and mobile devices, diminishing the need to be in the same physical office with coworkers. My team at WordPress.com was distributed around the world and was on the cutting edge of the latest tools and applications I’d never seen before. And when I began to work in such an environment, I discovered that my ability to lead hinged on earning trust and providing clarity to my direct reports – rather than deploying a fancy management method or strategy. With the smart, self-directed employees on my team (the kind who are now in high demand), I realized less command-and-control leadership was needed and favored guidance and coaching instead.

Test your abilities in the present day. Giving advice is a kind of storytelling. To teach someone a lesson as a speaker or consultant, it’s easy to pull on events from the past and sound very smart. But when you’re managing something in the present, stories are irrelevant: What matters are decisions and outcomes. In a real job, those decisions have deep, emotional, and long term effects – you can’t leave them after a few days or weeks. I hadn’t experienced those pressures in years.

Discover how well you practice what you preach. I’d written books about creativity and decision making, but how would I apply that knowledge to a real product, with millions of customers, and hundred of challenges? For example, my team had never worked on a rigorous schedule or with planned goals and milestones before and I had to figure out how to make these practices fit in their culture (or vice versa). I definitely made some big mistakes, but so far I haven’t heard anyone point out my inconsistencies. If they do, I’ll still be proud. Taking this challenge hopefully taught me new things that will make be a better teacher and advisor.

Of course consulting, teaching and writing are hard to do in their own right. They demand not only expertise but also the ability to translate that knowledge in ways people can use. Starting a consulting practice or writing a book is difficult, and has its own risks and challenges. But they can never be real in the same sense as the jobs the people hiring consultants and buying books have. The stakes for an executive in making a decision are magnitudes larger than for the consultant, however wise and well-paid they might be. No matter how popular he or she may become, a consultant is merely a commentator on the sidelines and not brave enough to get on the field, even just once a decade. We know the world changes fast today, which demands anyone giving advice to step back now and then to match their egos with experience.

Are you brave enough to take the challenge? And if not, how can you explain that decision to your clients?

Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations: Lessons from Year 1

In the three months since their release, the initial results of Medicare’s Pioneer Accountable Care Organization (ACO) program have generated divergent interpretations by analysts and policymakers. Some have pointed to savings and quality improvements in the first year as evidence that the program is off to a promising start to improving the value of care. Others cite the nine organizations leaving the program and the humbling results of a prior ACO experiment in Medicare — the Physician Group Practice Demonstration (PGPD) that ran from 2005 to 2010 — as reasons to be pessimistic.

While both camps have merit, we must keep in mind that after one year, there is still more unknown than known about how the Pioneer ACOs might perform over the long run. It is also important to remember how the Pioneer ACO contracts differ from both the PGPD and current ACO contracts outside of Medicare. By putting the first-year achievements of the Pioneer ACOs in the appropriate context, they look more impressive than they might otherwise seem, although the challenges they face going forward remain daunting.

ACOs are one of the main ways that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) tackles costs. About 250 ACOs contract with Medicare for the care of 4 million beneficiaries. Most chose a one-sided model in the Shared Savings program, under which they are rewarded for savings below a spending target but are not penalized for any spending above the target in the initial three-year contract period. In contrast, the Pioneer program, which began in early 2012 and involved 32 organizations, is a two-sided model that carries penalties for excess spending but also provides greater rewards for savings. Both programs reward ACOs for reporting and performance on quality measures.

The First Year’s Results

In Year 1, spending grew 0.3% for the 669,000 beneficiaries in Pioneer ACOs, which was 0.5 percentage points lower than the 0.8% spending increase for similar beneficiaries in the traditional fee-for-service program. The Pioneer organizations collectively beat their spending targets by $87.6 million in the first year, $33 million of which went to the Medicare Trust Fund. These savings came largely from 13 organizations, in part through reductions in hospital admissions and readmissions. Of the 19 other Pioneers, 17 had spending that did not significantly differ from their targets, whereas two had losses totaling about $4 million.

All ACOs were rewarded for reporting quality measures. Although rewards were not tied to performance in 2012 (they will be in later years), Pioneer ACOs did better on blood pressure and cholesterol control for beneficiaries with diabetes than did managed-care plans, and better on readmissions relative to the Medicare fee-for-service benchmark. Beneficiaries in Pioneer ACOs rated their experience higher on all four patient-satisfaction measures in 2012 than did fee-for-service beneficiaries in 2011.

At the end of the year, seven organizations that did not generate savings decided to transition to the Shared Savings program, and two decided to leave the ACO arrangement altogether. The absence of financial risk in the one-sided model and in the fee-for-service program is presumed to have contributed to their decisions.

A Context for the Performance

There are two bases for comparison: the Physician Group Practice Demonstration program and, outside of Medicare, the hundreds of ACO-type contracts between physician groups and private insurers that cover 15 million to 20 million people under the age of 65.

The PGPD program is seen by many as a bellwether of today’s ACOs. While all PGPD participants improved quality, only two sites achieved the minimum 2% savings in the first year needed to qualify for a bonus. Only four sites had statistically significant savings by the end of the demonstration. Although a greater proportion (40%) of Pioneer ACOs achieved savings in the first year, the PGP experience serves as a reminder of the difficulty of generating savings.

Yet one distinction bears emphasizing. While the one-sided ACO model is a cousin of the Pioneer model, they are distant cousins. Bearing risk for excess spending is a strong incentive to find savings and more likely to promote serious delivery-system changes. The PGPDs, unlike the ACOs created by the Affordable Care Act, were not required to move to such a two-sided model. Thus, the initial Pioneer results may lead a different path than that of the PGPD predecessors.

There are also significant differences between ACO contracts outside of Medicare and those of the Pioneer program. ACOs in Medicare have fewer options for cost control. Unlike private insurer contracts that have the flexibility to lower cost sharing for high-value services or high-quality providers, Medicare ACOs must rely on a standardized cost-sharing structure. They cannot restrict access to physicians outside the organization, putting them at the mercy of clinical decisions that are beyond their control. They cannot achieve savings by referring patients to lower-priced providers, since Medicare prices are more or less uniform. Thus, the only way for ACOs in Medicare to lower spending is to lower utilization. They can forgo wasteful services, find less expensive substitutes, or provide care to patients at home to prevent unnecessary hospitalizations. However, none of these is easy, which makes their 0.5 percentage-point lower spending increase relative to the fee-for-service program look even more impressive.

How the World Is Different and the Same

That decision of nine Pioneer ACOs to leave the program after the first year may well be the most ominous result. This evokes memories of the managed-care backlash, when capitation contracts of the 1990s that placed physician groups at financial risk proved to be unsustainable. In some ways, however, today’s environment is different. Physicians have more experience practicing in integrated delivery systems, contracts now include caps on potential losses, quality bonuses play a bigger role, risk adjustment has improved, awareness of wasteful spending has grown, and the urgency to slow spending has reached fever pitch.

Nevertheless, many institutional realities from the 1990s remain. The basic market failures in health care are still with us. Restraining utilization remains a difficult sell to patients and providers. Moreover, the delivery system is still best when people fall ill; it is less adept at managing population health for an aging nation. As Pioneer ACOs face continued pressure to lower spending without major parallel efforts to protect them from financial risk (like improving the nation’s public health system, medical-malpractice reform, and public education about high and low value care), there is no certainty that the remaining Pioneer ACOs will not someday walk away. Nor is there certainty that one-sided ACOs, mandated to transition to two-sided contracts after three years, will not walk away.

The Bigger Question

At its core, the ACO concept has two objectives: payment reform and delivery-system reform — with the hope that the first will kick start the second. Regardless of whether the Pioneer program or similar contracts in the private sector generate savings or improved quality in the short run, the bigger question is whether they will succeed in changing the nature of the delivery system. Will physicians and hospitals begin to join forces to keep populations healthy? Will providers across specialties climb out of silos in an age of joint accountability? Will patients fare better?

Unlike designing a payment contract, delivery-system reform has no blueprint. It inherently requires changing the culture of medicine — the way providers work with each other, relate to each other, and the way the system perceives patients. It calls on physicians across the specialties to find common ground in a world with shared risks and rewards, to work in teams and coordinate care towards common goals within their organizations. It calls on insurers to help providers identify waste and inefficiency, and patients to be part of the care team. And it calls on our health care economy to see patients less as commodity and financial opportunity and more as populations whose health and dignity the medical profession was envisioned to protect.

The ACO concept is vital because it enables delivery-system reform to make economic sense, and it provides physicians the opportunity to lead in this reform. With 10,000 Americans turning 65 every day over the next two decades, for Medicare, at least, this opportunity will look increasingly like an imperative.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

A Global Online Network Lets Health Professionals Share Expertise

How to Design a Bundled Payment Around Value

Providing High-Quality Health Care to Americans Should Trump Politics

Humility Compensates for Low Mental Ability

Among students with low mental ability, those who were rated by others as highly humble scored about 9% higher on performance measures over a 10-week team task than those who were seen as not humble. Humility’s performance-boosting effect was much less pronounced for highly intelligent people, says a team led by Bradley P. Owens of the State University of New York at Buffalo. The compensatory power of humility for those with low mental ability is probably due to humble people’s teachability, which is a result of their willingness to honestly understand their weaknesses, the researchers say.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers