Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1538

October 4, 2013

You Can Win Without Differentiation

For decades, strategy gurus have been telling firms to differentiate. From Michael Porter to Costas Markides and through the Blue Oceans of Kim and Mauborgne, strategy scholars have been urging executives to distinguish their firm’s offerings and carve out a unique market position. Because if you just do the same thing as your competitors, they claim, there will be nothing left for you than to engage in fierce price competition, which brings everyone’s margins to zero – if not below.

Yet, at the same time, we see many industries in which firms do more or less the same thing. And among those firms offering more or less the same thing, we often see very different levels of success and profitability. How come? What explains the apparent discrepancy?

To understand this, you have to realise that the field of Strategy arose from Economics. The strategy thinkers who first entered the scene in the 1980s and 90s based their recommendations on economic theory, which would indeed suggest that, as a competitor, you have to somehow be different to make money. Over the last decade or two, however, we have been seeing more and more research in Strategy that builds on insights from Sociology, which complements the earlier economics-based theories, yet may be better equipped to understand this particular issue.

Consider, for example, the case of McKinsey. Clearly, McKinsey is a highly successful professional services firm, making rather healthy margins. But is their offering really so different from others, like BCG, or Bain? They all offer more or less the same thing: a bunch of clever, reasonably well-trained analytical people wearing pin-striped suits and using a problem-solving approach to make recommendations about general management problems. McKinsey’s competitive advantage apparently does not come from how it differentiates its offering.

The trick is that when there is uncertainty about the quality of a product or service, firms do not have to rely on differentiation in order to obtain a competitive advantage. Whether you’re a law firm or a hairdresser, people will find it difficult – at least beforehand – to assess how good you really are. But customers, nonetheless, have to pick one. McKinsey, of course, offers the most uncertain product of all: Strategy advice. When you hire them – or any other consulting firm – you cannot foretell the quality of what they are going to do and deliver. In fact, even when you have the advice in your hands (in the form of a report or, more likely, a powerpoint “deck”), you can still not quite assess its quality. Worse, even years after you might have implemented it, you cannot really say if it was any good, because lots of factors influence firm performance, and whether the advice helped or hampered will forever remain opaque.

Research in Organizational Sociology shows that when there is such uncertainty, buyers rely on other signals to decide whether to purchase, such as the seller’s status, its social network ties, and prior relationships. And that is what McKinsey does so well. They carefully foster their status by claiming to always hire the brightest people and work for the best companies. They also actively nurture their immense network by making sure former employees become “alumni” who then not infrequently end up hiring McKinsey. And they make sure to carefully manage their existing client relationships, so that no less than 85 percent of their business now comes from existing customers.

Status, social networks, and prior relationships are the forgotten drivers of firm performance. Underestimate them at your peril. How you manage them should be as much part of your strategizing as analyses of differentiation, value propositions, and customer segments.

Multitasking Makes Managers Less Thoughtful

You’re sitting at a meeting checking your e-mail on your iPad or your texts on your phone. Or, if you’re like the average college student, your attention is divided at least three ways, among the lecturer, your laptop, and your text messages. You think you’re keeping up with it all, but new research from Stanford says you’re not. Studies from Clifford Nass's Communication Between Humans and Interactive Media Lab clearly indicate that those who engage in media multitasking are unable to ignore irrelevant information and have difficulty identifying which information is important. Even watching that stream of type crawl across your television screen during the evening news makes you less likely to retain information from either the program or the crawl. Media multitasking makes managers less thoughtful and more inclined to exercise poor judgment, Nass says. And companies that encourage people to respond instantly to e-mail make the problem worse. At the very least, managers should insist that employees bring no electronic devices to meetings. —Andrea Ovans

Getting the VaporsKodak Moment The Economist

With the European Parliament set to vote next week on whether electronic cigarettes should be regulated as medical products, this is a good time to reflect on the inroads this disruptive technology is making in the slow-moving, not-very-innovative tobacco industry. While smoking is declining in most developed countries, "vaping" is on the rise (in e-cigarettes, a nicotine solution is vaporized — thus the verb). An estimated 7 million people use e-cigs in Europe alone, and sales in the States may triple this year. One analyst says they could outsell cigarettes within a decade. Which some think would be a good thing, from a health standpoint. But will regulators in Europe and the U.S. (the FDA is expected to propose restrictions soon) allow this juggernaut to keep rolling? UK e-cig advocate Clive Bates hopes so: "The market is producing, at no cost to the taxpayer, an emerging triumph of public health." —Andy O’Connell

Because No One's Telling Them They Should Be There Why Are There Still So Few Women in Science?New York Times

Before starting her career as a creative writer, Eileen Pollack was one of the first women to earn a BA in physics at Yale, graduating summa cum laude in 1978. So why didn't she further her education in the subject? Using her own story as an example, Pollack explores the many reasons women still aren't widely represented in the top echelons of science, an issue that becomes even more pressing as STEM becomes shorthand for the future of economic success worldwide. In short, particularly in the United States, it comes down to culture: From high school on, girls and women are receiving signals that science and math aren't cool or viable options. Stories abound about it being a tough life, an assertion Yale astronomer Meg Urry responds to with a succinct "Oh, come on." Pollack says we need to stop losing girls “to their lack of self-esteem, their misperceptions as to who does or doesn’t go into science, and their inaccurate assessments of their talents."

Let Innovators InnovateMedical Innovation: When Do the Costs Outweigh the Benefits? Knowledge@Wharton

Ugh. Health-care costs. One reason your premiums are so high is that your insurance company had to pay top dollar for the scary-looking piece of robotware that removed that thing from that embarrassing part of your body. Should the insurance company refuse to pay for such things and insist that your doctor go back to doing it by hand with a sharp knife? No, says Guy David, a Wharton professor of health-care management. Any initiative to limit payments for innovative technologies would have unintended consequences — such as effectively killing the development of the truly high-value inventions that shorten procedures, save lives, cut costs, and reduce errors. "If you curtail anything, you’re never going to get to the high-value innovation,” he says. —Andy O'Connell

Take Your Pick Challenging the Bing-It-On ChallengeFreakonomics

Oh, the perils of using questionable data in your major ad campaign. In this fascinating takedown (which I first discovered on Slate), economist and Yale Law School professor Ian Ayres takes Bing's assertion that people prefer Bing "nearly 2:1" — a claim he initially thought was implausible – and tries to prove his hunch. Ayres and his students found two elements of Microsoft's research problematic: The company surveyed only 1,000 participants, and it refuses to release the results of its online "Bing-It-On" challenge, which more than 5 million people have taken. So Ayres and co. set up a survey similar in size to Microsoft’s and found that "53 percent of subjects preferred Google and 41 percent Bing (6 percent of the results were 'ties')."

Ayres cheekily suggests that Google might have a legal case against Microsoft. Bing's behavioral scientist, for his part, issued a response and rebuttal. Matt Wallaert explains why the company stopped using the "nearly 2:1" phrase in its marketing material and defends the company's research methods.

BONUS BITSThose Other Things That Happened This Week

The FBI and the Legitimation of the Bitcoinverse (Reuters)

How to Quit in Front of An Audience of 11 Million (Quartz)

Obamacare: The User Experience (Businessweek)

The Cure for Self-Inflicted Complexity

The collective belief that complexity is on the rise is largely an illusion. We’ve inflicted it on ourselves by our primary method of dealing with the complexity that has always been an inherent part of our world. As I’ve argued previously, we attack dynamic complexity by minimizing detail complexity, and thus divide the world into numerous deep knowledge domains – which in turn generates a disquieting level of inter-domain complexity.

This of course begs the question: is this self-inflicted inter-domain complexity a problem? Should we be worried about it?

Because we are notably bad at dealing productively with the inter-domain complexity that we have created, I think it is indeed a problem. Ironically, we are crummy at dealing with it because of the predominance of narrow knowledge siloes – which are of course the self-same knowledge siloes that created the inter-domain complexity in the first place. Kafka would be impressed!

Inter-domain complexity challenges us whenever a hospital patient has co-morbidities (heart and liver problems for example), or a business problem spans marketing and finance, or a political problem bridges foreign relations and domestic economics. The specialists who focus on heart, liver, marketing, finance, foreign relations, and domestic economy frame the problems using their tools, models, and language systems because that is what they know and that is where their confidence lies. It is hard for them to un-frame what they have framed or un-see what they see.

It is not impossible. It is just hard. Typically, every bit of their formal and informal education has taught them to sacrifice detail complexity – to narrow problems to facilitate analyzing them. They don’t actually know how to take two opposing frames, models, and diagnoses, and do something useful with them. In fact, the more expert they are, the less likely they are to ever have done so – even once in their life. So they stick assiduously to something at which they are terrifically good: being narrow, and confidently so.

Furthermore, they tend not to suffer any personal downside from taking a narrow perspective. The heart surgeon doesn’t get blamed if the patient’s liver failed due to the stress of surgery. The marketing executive doesn’t get blamed if the finance executive failed to come up with the capital necessary to fulfill the marketing executive’s grand plans.

Net, there is little training and few rewards for dealing productively with inter-domain complexity.

Were there no heart, liver, marketing, finance, foreign relations, or domestic economy experts, we wouldn’t face inter-domain complexity or the associated problems. However, we would face lots of detail and dynamic complexity. The world is not entirely crazy. There is a reason to specialize in order to try to cut into dynamic complexity, to try to tease out cause and effect relationships and advance our knowledge in various domains.

The key, as with so many things in life, is to get beyond either/or. To move our understanding of the world forward, we need to tackle both detail complexity and dynamic complexity. We don’t want to operate with one gigantic knowledge domain in which our ability to advance knowledge is ponderously slow. But by the same token, we don’t want innumerable knowledge domains that slice and dice our world into such little and incompatible pieces that we advance knowledge that isn’t really powerful for our lives.

I believe that the solution to the self-inflicted problem of inter-domain complexity is the development of a meta-domain: the domain of knowledge about how to integrate across knowledge domains. While this might seem on its face to be an esoteric or even unapproachable knowledge domain, it really isn’t either. There are techniques for tackling fully clashing models from different knowledge domains.

More importantly, these techniques can be taught, though masters of individual knowledge domains tend to fight against the notion that anybody not steeped in their frames, models, and tools can deal with their domain in any useful way.

Perhaps most excitingly, these techniques for dealing productively with inter-domain complexity can be taught to children. In our I-Think initiative at the Rotman School, we’re teaching even elementary school children how to wade confidently into and resolve inter-domain conflicts.

These young people have a blessed characteristic not shared by their adult counterparts: they don’t think what they are doing is strange; they think it is just plain sensible. If we train enough of them, I think we’ll see many positive changes in the years to come. Among them will be a common sense that complexity is dropping, not rising.

This post is part of a series of perspectives leading up to the fifth annual Global Drucker Forum in November 2013 in Vienna, Austria. For more on the theme of the event, Managing Complexity, and information on how to attend, see the Forum’s website.

A Global Online Network Lets Health Professionals Share Expertise

Dr. Junior Bazile, a Haitian physician, scrolled through his handheld device while walking through the wards of a district hospital in rural Malawi. He had recently commented on a discussion on GHDonline.org regarding critical gaps in the diagnosis and treatment of drug resistant tuberculosis. Hours later, he was reading detailed replies from a tuberculosis advisor in Azerbaijan and a medical officer at the World Health Organization. They shared recent publications and discussed the best strategies for how to ensure that patients are treated swiftly and their families and communities protected.

Five years earlier, providers like Dr. Bazile across the globe had a plethora of “how” questions: How do you diagnose recurrent tuberculosis? How do you design team-based care? How can community health workers extend care into the home? How do you design a hospital? But there was no means to obtain answers.

In response, our team at the Global Health Delivery Project at Harvard launched an online platform to generate and disseminate knowledge in health care delivery. With guidance from Paul English, chief technology officer of Kayak, we borrowed a common tool from business — professional virtual communities (PVCs) — and adapted it to leverage the wisdom of the crowds. In business, PVCs are used for knowledge management and exchange across multiple organizations, industries, and geographies. In health care, we thought, they could be a rapid, practical means for diverse professionals to share insights and tactics. As GHDonline’s rapid growth and success have demonstrated, they can indeed be a valuable tool for improving the efficiency, quality, and the ultimate value of health care delivery.

The Launch

Creating a professional virtual network that would be high quality, participatory, and trusted required some trial and error both in terms of the content and technology. What features would make the site inviting, accessible, and useful? How could members establish trust? What would it take to involve professionals from differing time zones in different languages?

The team launched GHDonline in June 2008 with public communities in tuberculosis-infection control, drug-resistant tuberculosis, adherence and retention, and health information technology. Bowing to the reality of the sporadic electricity service and limited internet bandwidth available in many countries, we built a lightweight platform, meaning that the site minimized the use of images and only had features deemed essential.

As access to high-speed internet and handheld devices increased, new features were gradually added to include photos and video data. To foster reliability and engagement, the team decided that activity on the site would be transparent (i.e., there would be no anonymous postings) and moderators would lead the communities. They would stimulate and ensure quality discussions in the communities by reviewing GHDonline’s content daily for precision and accuracy. (We recruited over 30 experts to serve in that role.) The public could read the discussions and posts but only those who signed up could contribute to discussions. Members would sign up at no cost and would create a profile with their name, professional background, and optional photo.

Soon after the launch, a researcher in South Africa asked the tuberculosis community about the protocol for sputum induction — a procedure for diagnosing TB — in outdoor settings. In less than a week, over 20 experts from four continents shared their insights. The researcher followed the suggestions in building her facility’s new outdoor structure for sputum induction.

Even with early successes in terms of membership growth and daily postings to communities, user feedback and analytics directed the team to simplify the user navigation and experience. Longer, more nuanced, in-depth conversations in the communities were turned into “discussion briefs” — two-page, moderator-reviewed summaries of the conversations. The GHDonline team integrated Google Translate to accommodate the growing number of non-native English speakers. New public communities were launched for nursing, surgery, and HIV and malaria treatment and prevention. You can view all of the features of GHDOnline here (PDF).

Growing Participation

These improvements helped attract more participants: As of July 2013, GHDonline hosted 10,000 expert members — engineers, researchers, architects, policymakers, advocates, pharmacists, community health workers, physicians, managers, midwives, program officers, nurses, and social workers — across 170 countries and 10 public communities.

In addition to public communities, GHDonline launched private communities to accommodate global health groups with select membership, including time-limited working groups. As of July 2013, there were 50 private communities.

One, Clinical Exchange, which was launched in 2009 to link Rwandan physicians to Boston-based specialists, has proven incredibly valuable for improving health care delivery. A physician in Rwanda can log onto the GHDonline.org clinical exchange community via the web or send an e-mail to clinical@ghdonline.org to respond to or post a new case in the community. The physician can upload or attach photos of rashes, x-rays, CT scans, or videos.

All members subscribe to instant notifications of activity in the community or to daily or weekly digests. Community moderators select the instant notifications so they can ensure a specialist responds to clinicians in a timely fashion. All members agree to de-identify patients and follow HIPPA guidelines. Images are reviewed by the appropriate subspecialist. Radiologists post readings and formulate curriculum for general practitioners on common radiological findings. Each question that is asked and answered is archived in the community, thus generating an information and image library for training.

A member of the Clinical Exchange community posted a thorough patient history, physical-exam findings, and lab results for second opinions on a 56-year-old male presenting with a history of urinary retention, weight loss, and impotence. Within 20 hours, five clinicians from various specialties had responded. All the Boston and Rwandan doctors agreed on a diagnosis of multiple myeloma and recommended steroid palliation, a drug regimen, and steps for stabilization. As the patient’s condition improved, the doctor who started the discussion in the community submitted updates for members of the community and received further guidance.

Members and moderators have discussed hundreds of clinical cases and have shared over 400 resources, impacting clinical decision making in Haiti, Rwanda, and Malawi. Participating physicians in Boston have grappled with cases of leprosy and neglected tropical diseases and the complexities of end-of-life care.

Adapting to Demands

Unlike a static web page, the GHDonline platform can iterate on content, add discussions, and bridge expertise to respond to the changing landscape of health delivery. For example, after the earthquake in Haiti on January 12, 2010, GHDonline opened a new community to link organizations involved in the emergency response and local organizations in Haiti. In April 2010, the GHDonline team organized a virtual panel in the Health IT community and invited experts to discuss the data and technology needed to rebuild health systems in Haiti.

The success of this panel led to a series of “expert panels” — virtual, asynchronous, one-week conferences convening professionals across specialties to discuss pressing issues in health care delivery — and attracted panelists such as Rwanda’s minister of health and the director of the largest HIV clinic in the United States. (Here’s a list of panels). The increasing access to high speed Internet and mobile devices and applications has also facilitated the success of GHDonline.

Professional Development

As GHDonline.org has improved care for patients, it has also increased professional development and leadership opportunities for members who otherwise might be working in isolation. For example, Dr. Bazile began reading GHDonline daily in 2010. Since then, he progressed from a frequent consumer of community discussions to an active GHDonline user and educator across communities. (Here’s a biography of Dr. Junior Bazile and a graphic of his development as a GHDonline member).

GHDonline’s virtual communities have led to the creation of a broad knowledge base and a professional network. As its progress has demonstrated, virtual networks are ideal mechanisms to create and disseminate the next generation of tools and tactics to generate value for patients and populations.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

Health Insurance Exchanges Fulfill Both Liberal and Conservative Goals

Reimagining Primary Care: When Small Is Beautiful

Getting Big Results from a Small Business Unit

Aggressive Talent Wars Are Good for Cities

California is often ranked among the world’s most inventive regions. But most observers miss one of the major reasons why: the absence of non-compete agreements.

Barring non-competes is one of California longstanding strong talent mobility safeguards. Unlike most other states in the United States, but more like innovative Western European countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, California has rules about allowing job mobility within markets. The California Business Code voids all non-competes agreements between businesses and their employees, while the California Labor Code restricts the ability of corporations to require their employees to pre-assign all inventions, even if unrelated to the job, during the course of employment.

California courts have been so adamant about enforcing the state’s prohibition of non-competes, they’ve held that companies who do not hire or promote talented employees who refuse to sign a non-compete (which would be void anyway if taken to court) are liable in tort and should be subject to punitive damages. They’ve even refused to enforce non-competes that were signed in other states, announcing them contrary to state policy.

Conversely, Boston’s Route 128 tech beltway has not flourished the way Silicon Valley has, in part because of restrictive non-compete agreements. Non-competes have contributed to the more rigid, vertically integrated, and prone to insourcing ethos of Boston’s high tech region.

California’s lack of non-compete agreements is the reason Marissa Mayer could assume the position of CEO at Yahoo! immediately upon leaving its direct competitor, Google. And, as it turns out, it’s the reason California’s cities are some of the most innovative in the world – and provides a model for fueling innovation and economic growth elsewhere.

Job-hopping at all ranks is part of the California knowledge economy, but the policy spills over to the industrial culture too, creating a culture of openness, movement, and networking, where companies know that the talent wars are a repeat game. Even though Californian companies face a higher risk that their best talent will leave, they also recognize the long-term benefits of talent mobility. And industry leaders learn to view the departure of employees not only as a loss (because of course there is a loss) but also as potential gain, in which former employees may eventually return, bringing new skills back with them.

Although most companies are keen to reduce turnover, a stunning number of new studies demonstrate how high employee turnover actually contributes to economic growth. Research by Matt Marx (Sloan) and Lee Fleming (Berkeley) finds that after Michigan began to allow non-compete agreements, the state experienced a brain drain of its best talent. Many decamped for California, especially those inventors with the most-cited patents. In another recent study on VC investment and non-competes, Yale SOM professors Samila and Sorenson conclude that mobility restrictions not only impede entrepreneurship and start-up ventures, they slow the overall economic growth of a region. Studying a decade’s worth of data on over 300 metropolitan areas in the United States, including patent filings, levels of VC investment, and level of entrepreneurships, the study finds that relative to states that enforce noncompetes, an increase in venture capital in states that either void or restrict non-competes has significantly stronger positive effects on regional patenting rates, start-up rates, and job growth. In response to an identical influx of local VC, states that do not enforce non-competes experience twice the increase in patents, double the birth of new companies compared to states that enforce them, and three times the employment growth of non-compete enforcing states, benefiting not only the start-up segment of a region but also incumbents.

There is also a motivational aspect in allowing people to leave and encouraging them to stay using positive, rather than negative, incentives. In recent behavioral studies, my collaborator On Amir (Rady UCSD) and I find that participants bound by non-compete agreements and other post-employment restrictions did not perform as well and were less motivated to stay on task than those unbound. Participants in our experiments were more likely to quit the task and to make errors when they were asked to sign non-competes. Garmaise (Anderson UCLA) finds that non-compete enforcement strongly reduces executive mobility and shifts compensation from bonuses and performance-based pay to a heavy reliance on a fixed salary.

In other words, performance carrots work better than restrictive sticks. Think about it: human capital is not a static resource in the way real estate or building materials serve a construction company. Human capital is both a resource and a living subject who makes constant judgments, decisions, and choices about the quantity and quality of outputs.

If you can’t legally restrict your talent from leaving, you’d find better more motivating approaches to retain it.

Capturing the Innovation Mindset at Bally Technologies

Bally Technologies, a leading provider of gaming systems for casinos, has earned more than 60 awards for innovation in just the last four years. It increased R&D spending from 7-8% of revenue before 2009 to 11-12% of revenue starting in 2010, and maximized the return on that increased investment. The result: Its return on assets tripled, from an industry-lagging position below 4% to an industry-leading position above 12%. How did Bally Technologies do it? Through an innovation excellence framework.

This framework is not new; we introduced a similar mind-set in an earlier post with 3M. But while the foundational elements are the same, Bally Technologies uses them in a distinct way. It has a more rigorous organization structure that divides responsibilities between the innovation team and development team, and strengthens management around the opportunity pipeline. The company combines this with an intense focus on execution and weekly course correction — but also uses innovation as a means to get the employees energized.

Bally Technologies has achieved great success, but only after making this framework its own. Using the five tenants we introduced before, here’s a breakdown of how the company does just that.

Innovative companies find the right opportunities by providing forums for customer voices and for researchers to proactively look for new technologies to benefit customers.

Bally Technologies uses customer panels to understand the voices of its customers and to shape new opportunities. Focus groups are also used to understand how engaging the games are, whether they need to be redesigned or fine-tuned, and whether the opportunity needs to be shaped before it becomes practical. This is done in specially designed rooms, where customer behavior can be observed without the customers becoming distracted.

Moreover, researchers regularly attend trade shows and seminars that showcase next-generation technology. This helps them come up with breakthrough ideas to explore.

Innovative companies create an environment that fosters the right balance between current and future with “and thinking.”

Bally Technologies has several mechanisms to sustain “and thinking.” Its Innovation Lab focuses on ideas and technologies two to five years out, not all of which come to fruition. Once a technology prototype has been focus-group tested and a viable business model is established, it is handed over to a new product development team in the mainline business units. These teams have disciplined processes to get the technology to market, generally with a one- to two-year product horizon.

This multilevel structure ensures that the day-to-day operations of quarterly and annual performance are not disturbed until the opportunity has matured, with predictability and repeatability that can be managed by the operations team. At the same time, Bally Technologies has a portfolio of ideas and patents that ensure the organization will stay relevant in the future.

Innovative companies create systems, structures, and work environments to encourage resourcefulness and initiative.

Bally Technologies actively emphasizes innovation. “We bring to market a steady stream of innovative products and solutions. This is possible because our employees are resourceful and have an innovative mindset, and we create the right climate for them by continuing our commitment to R&D across games products, systems, and interactive technology,” Bally Technologies’ President and Chief Executive Officer Ramesh Srinivasan told us.

Bally Technologies has created a rich set of structures, systems, and rewards to encourage resourcefulness and innovation, including cash awards like the Patent Disclosure of the Quarter ($5,000) and the Patent Disclosure of the Year ($25,000). There are also “challenges” to which any employee or group of employees can respond — an organization-wide crowdsourcing approach. For example, one specific challenge was, “What is the next wave of ideas that can be used to take advantage of location-aware mobile technology for our casino customers?” Responses are vetted for viability and patentability, and the winners are submitted to the annual Best in Bally Leaders in Innovation Award.

Finally, it has Kaizen events where both salaried and hourly employees gather together for a week, mapping processes in order to solve problems and streamline operations. The Kaizen events create not only fresh ideas but also a spirit of learning and cooperation through the company. Team presentations at the end of the week have become a powerful and proud part of Bally Technologies’ culture.

Innovative companies focus on the right set of outcomes. They tailor what is measured, monitored, and controlled to suit their focus, and strike the right balance between performance and innovation.

Bally Technologies prides itself on being practical and focused on outcomes. Every senior executive submits a weekly report that answers three questions:

What are three things in your world that are going well?

What are three things in your world that are not going well?

Are there any exceptional employee behaviors that need to be recognized?

A summary report is then sent to all executives; this creates an openness to share weaknesses, aligns priorities, and helps keep the focus on things that matter most. Take, for example, a plane heading from Boston to Phoenix. If that flight’s trajectory were just a degree off, it would end up in the Grand Canyon. But the fact is that planes are more than a degree off 95% of the time, and most planes land where they are supposed to. How do they do it? One key reason is dynamic course correction. The weekly report and the actions taken to respond serve the same purpose for Bally Technologies. It helps the company to take actions in time to make a difference.

Innovative companies have strong mechanisms to ensure a continuing focus on expanding the pie, by effectively converting nonconsumers into consumers, and providing richer solutions to current consumers.

Instead of focusing only on individual games and machines, Bally Technologies expands the pie by creating systems that connect the entire gaming floor. This provides the casino operators an enterprise-wide view of what works, what doesn’t, and what actions to take to improve performance. It then builds on that foundation to deliver the same great game experiences on mobile devices as on the casino floor and extend a casino’s ability to market, engage, and monetize their customers on these new distribution channels with its iGaming Platform.

The innovation mind-set is a game-changing asset for companies as well as individuals. Innovative companies like Bally Technologies create the structure, systems, and culture to enable their people to think and do things differently in order to achieve extraordinary success.

Executing on Innovation

An HBR Insight Center

Good News, Bad News: An HBR Management Puzzle on Innovation Execution

Why Conformists Are a Key to Successful Innovation

Implementing Innovation: Segment Your Non-Customers

Can Internal Crowdfunding Help Companies Surface Their Best Ideas?

Customers Care More About a Line’s Length than How Fast It Moves

A word of caution to companies that pool their customers into one queue with multiple servers: In deciding whether to join a line, customers care a lot more about line length than number of servers. Even if it’s moving quickly, a long line can put customers off, according to a team led by Yina Lu of Columbia University. The team’s study of supermarket customers showed that a line of 10 people can have a large impact on purchases, and increasing the queue length from 10 to 15 customers would lead to a 10% drop in sales.

Just Make a Decision Already

Strategic decisiveness is one of the most vital success attributes for leaders in every position and every industry, but few leaders understand where it comes from or how to find more of it. It is not surprising that picking one strategic direction and then decisively pursuing that direction are hallmarks of good leadership, if not boilerplate management skills. The big mystery is why these obviously important skills are still rare enough to distinguish excellent leaders from average managers.

In researching Why Quitters Win, I came to recognize the three primary sources of decisiveness — nature, training, and incentive — and also how you can manipulate them to claim an advantage for yourself and your organization.

1. Decisive By Nature. In a 2010 study, Psychologist Georges Potworowski at the University of Michigan found that certain personality traits (e.g., emotional stability, self-efficacy, social boldness, and locus of control) predict why some people are naturally more decisive than others.

When faced with two equally attractive strategic options, timid, less emotionally stable leaders who fear upsetting anyone will let the debate drag on for weeks or months before selecting a compromised Frankenstein solution that both sides can merely tolerate. At the end of the year, the team is moderately satisfied with their moderate impact on a smattering of moderately important objectives. The team successfully achieves mediocrity, which is then reflected in the leader’s mediocre performance ratings.

More decisively gifted mangers make it clear from the beginning that they will carefully consider both sides of the argument, but will ultimately choose what they judge to be best for their team. They make the decision early on, and move quickly to enlist both sides in executing her decision. Some members of the team are not thrilled with the choice but are quietly pleased to finally have some clarity of direction. The team makes significant progress in the chosen strategic direction, which is reflected in their high performance ratings.

2. Decisive By Training. In the mid-1990s, researchers Shelley Taylor of UCLA and Peter Gollwitzer at NYU discovered that when contemplating a decision we have not yet made, virtually everyone will temporarily exhibit the same personality traits — neuroticism, low sense of control, pessimism — that the Michigan study linked to indecisiveness. As soon as we make the decision and begin charting the steps for executing it, our brains automatically switch gears. All of the sudden, we feel confident, capable, and in control — the perfect mindset for behaving more decisively.

In other words, all of us have the potential to be decisive or indecisive. In a given day, most of us slip in and out of a decisive mindset. The excellent leaders in Kevin Wilde’s study have simply learned how to make “decisive” their default setting. That initial decisiveness puts them in a more decisive mindset which begets even more decisiveness and so on.

Paradoxically, it seems the best way to slip into a decisive mindset is to make a decision. But in my experience, simply training people to apply a simple process with a clearly defined start and end point gives them the emotional permission they need to get the ball rolling with that first decision.

3. Decisive By Incentive. In 2006 Agilent Technologies CEO, Bill Sullivan decided that his managers’ decisions were not keeping pace with the rapid industry changes. Within just 3 years, the company’s mangers leaped from the 50th percentile in decisiveness (relative to industry peers) up to the 82nd percentile. How?

Together with his head of Global Talent, Kirk Froggatt, Sullivan created a simple “speed to opportunity” metric in which they periodically asked every employee to rate their manger on decisiveness. The simple metric made Agilent’s managers constantly aware that timely decisions are both valued and rewarded in their organization.

Neither the training mentioned above, nor incentives like Agilent’s decisiveness metric invalidate data-gathering, collaboration, and critical thinking skills. These skills should be baked into the decision process itself. The point is to clarify for managers that all of these skills are merely means to the true end goal of making a decision. If the end result is not a timely decision, then it doesn’t matter how much collaboration or critical thinking took place.

October 3, 2013

How Goldman Sachs Drifted

Steven G. Mandis of Columbia Business School discusses his book, What Happened to Goldman Sachs: An Insider’s Story of Organizational Drift and Its Unintended Consequences.

How to Design a Bundled Payment Around Value

The traditional fee-for-service reimbursement model is widely acknowledged to be a major driver of escalating health care costs. Because it rewards the volume of treatments, not the medical outcomes produced, it offers no way for the industry to reward its best providers and for patients to seek them out. It also penalizes cost reduction since eliminating unnecessary procedures leads to lower reimbursements.

For this reason, many health care practitioners and policymakers advocate a new bundled-payments model that reimburses providers with a fixed fee for delivering all the services required to deliver a complete cycle of patient care for a specific clinical condition. Bundled payments (BP) have the potential to reward providers that deliver more value to their patients — better outcomes at lower costs.

In practice, however, bundled payments have struggled to gain traction. One reason is many bundled-payment contracts use artificially short time horizons, not a complete cycle of care, which cause the contract to be similar to a traditional fee-for-service model. Another reason is these new contracts are negotiated at the payer-administrator level in a zero-sum cost-shifting process. Insurers strive to lower the prices they pay while the hospital’s contract administrators attempt to preserve top-line revenues. Physicians, left on the sideline while these new contracts are being forged, are further distanced from the new payment model because they often lack experience in measuring patient outcomes and have little confidence in their costs.

To understand how to address these concerns, an academic team from Harvard Business School brought together a group of orthopedic surgeons from the Boston Shoulder Institute and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, a Boston-based insurer, to create a new BP model focused on patient value. While the final price for the contract has yet to be negotiated, we believe that the structure and development process used to create this bundle can inform other providers and insurers about how to create bundled-payment contracts that benefit all the stakeholders: providers, insurers, and, most importantly, patients.

The Motives of the Pilot’s Members

The Harvard researchers believed that their expertise in value-based health care delivery could help the physicians and the insurer construct a superior BP contract in which the insurer paid a lower price, providers preserved their financial margins, and patients enjoyed superior outcomes. Rather than a zero-sum negotiation, such a new contract would be a win-win for insurers, providers, and patients.

The surgeons (all physicians from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital) participated because they wanted a reimbursement model that rewarded providers for delivering better medical outcomes for their patients at a lower cost. They were already measuring their patient outcomes and were in the process of introducing a costing approach that would enable them to participate in a new payments model.

Harvard Pilgrim agreed to join the effort because it recognized that traditional payment models were unlikely to help control rising health care costs. With regulators increasingly prone to challenge rate increases and employers unwilling to accept premium increases, the insurer felt that a BP model, co-created with clinicians, represented an attractive path for offering lower prices to its customers while preserving their access to the best providers.

The team has been meeting every two weeks over the past four months to design a BP model for a pilot project. The key elements of the project are the following:

Defining the Bundle

The working team selected damage to rotator-cuff tendons as the clinical condition to be bundled. Rotator-cuff repair (RCR) is a high-volume procedure with a definable cycle of care for which there is substantial variability in outcomes across physicians. Therefore, the team believed that RCR surgery offered an opportunity to improve outcomes and standardize treatment around best processes.

The team members wanted to define a cycle of care that corresponded to the medical condition of the patient. They selected a care cycle that starts with the initial pre-op appointment and concludes one year after the day of surgery. They agreed that this period would allow short-term surgical complications to emerge and be addressed within the bundle and that the recovery time would be sufficient to meaningfully measure patient outcomes.

The procedures and resources in the bundle would include pre-op appointment and testing, use of the operating room and facility services on day of surgery, surgeon, anesthesiologist and support staff, clinic visits, in-hospital drug and laboratory tests, and post-surgical physical therapy.

Two issues had to be addressed. First, although the bundle is tied to achieving measurable outcomes during the year, no business organization in any industry will wait that long for payment. Harvard Pilgrim agreed, therefore, to pay most of the bundled price 30 to 60 days after the surgical event; the remainder would be held back until the guaranteed outcome could be assessed at the 365-day mark.

The second issue was Harvard Pilgrim’s existing IT system, which had been designed to support the fee-for-service model. The insurer agreed to bypass the system and use manual procedures in the pilot study to track and bill patients and pay providers.

Selecting the Patient Population

The team’s goal was to be as inclusive as possible in specifying the patient population while incorporating the appropriate risk adjustments. The team identified a core group that would capture at least 80% of the potential RCR population. It also created risk-adjusted tranches to include patients who, based on medical evidence, had a higher intrinsic risk of failure due to medical comorbidities, age, body-mass index, and other factors and adjusted expected outcomes and a pricing differential for patients in each tranche.

Specifying Outcomes and Guarantees

The surgeons reviewed the clinical literature and their own research to select, with the insurer, the outcomes that matter most to patients. These included a mix of objectively measurable outcomes, such as rotator-cuff strength and the rates of complications that occur during operations, and subjective patient-reported outcomes such as pain, the ability to perform activities of daily living, and satisfaction with their outcomes.

The bundle incorporated the metrics in two ways. First, payments would be made to physicians and the hospital only if patients achieved specified minimal performance in each area. Second, if outcomes exceeded a more ambitious performance level, the insurer would make incremental bonus payments.

Such outcome-based guarantees and incentives are rare in traditional top-down bundled-payment contracts created without the input of frontline physicians. These contracts typically involve compliance with certain procedures (such as timely administration of pre-operative antibiotics) that may be easy to agree on and implement but may be peripheral to the ultimate patient outcome. The Boston Shoulder Institute surgeons and Harvard Pilgrim agreed that their set of metrics could provide patients better experiences and could be used to attract more patients to high-value providers.

To enhance transparency, the insurer intended to clearly communicate to patients, ahead of time, a price for the complete treatment cycle and the outcomes that could be expected. The physicians agreed to provide outcomes data to the insurer throughout the care cycle.

Ensuring Patient Engagement

Everyone recognized that the engagement of both patients and external professionals involved in the RCR cycle of care was critical for the project’s success. Toward that end, the Boston Shoulder Institute agreed to identify downstream physical therapists and to train, certify, and compensate them. The physicians also planned to conduct extensive patient pre-op education on narcotics, discharge, and physical therapy as well as provide 24-hour turnaround for all telephone calls, same-day office visits for urgent care, and a phone call from the physician’s office on the first day after surgery.

Harvard Pilgrim agreed to design new, innovative plans whose features included waiving such liabilities as co-payments if a member chose a high-value RCR provider for the surgery. The insurer expected to publicize the BP pilots through media and employer channels to attempt to drive increased volume to these high-value providers.

Estimating Costs

The Boston Shoulder Institute wanted to enter the negotiation with an in-depth understanding of all its costs over a typical RCR-care cycle, something that it could not learn from its existing costing systems. The Harvard Business School team helped the institute’s physicians and staff apply time-driven activity-based costing to measure the costs across the full cycle of care. They began by taking a careful inventory of resource needs and usage for each process in the cycle.

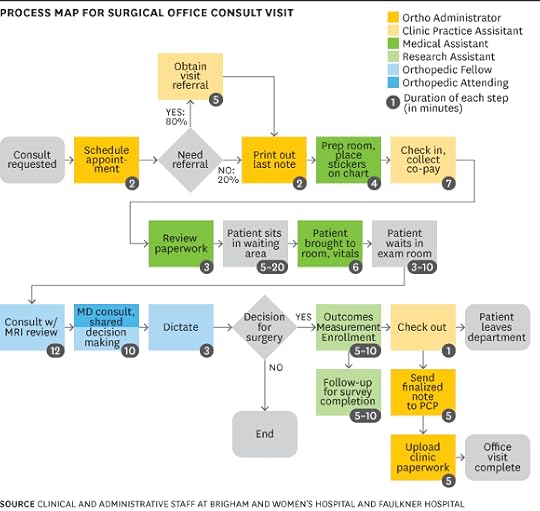

The figure “Initial Surgical Consultation” shows the detailed map for the first process. At each step in this process, the team identified the personnel and equipment required and measured the time consumed by each resource in performing that process step.

The team then accessed data from hospital and physician departmental budgets, the human resources system, and the equipment and facilities databases to estimate the “capacity cost rate,” the cost per minute of each person and piece of equipment used in the care cycle. It also calculated the cost of space used by each resource or clinical and administrative process. The team combined the time and cost estimates to obtain the total cost for surgical treatment of rotator-cuff tears.

Setting the Price

Going into the price negotiation, the Boston Shoulder Institute’s aim is to achieve better patient outcomes and thereby earn a margin over the actual costs incurred. This will come in several ways: the bonus payments for consistently producing superior outcomes; more business driven to them by the insurer because of the better outcomes; and, with a higher volume of patients, more cost-efficient processes. Harvard Pilgrim’s objective is to achieve a bundled price that represents a discount from its fee-for-service payments to facilities, clinicians, and therapists for the RCR care cycle (along, of course, with the superior outcomes). Looking down the road, it believes that if it can extend the new BP model to other conditions, it will be able to reduce its premiums and differentiate itself by offering superior, guaranteed outcomes.

Boston Shoulder Institute physicians and Harvard Pilgrim are now waiting for senior management at Partners HealthCare, the parent of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, to review the proposed bundle and to negotiate the price for a trial period. The trial would allow the physicians, hospitals, and therapists to learn how to work together under the new arrangement and set the foundation for a long-term contractual relationship.

***

Throughout the project, the Harvard researchers have kept the discussions focused on the prize: aligning provider and insurer incentives to deliver more patient value. The interactions have given the providers confidence that the costs assigned to the clinical treatments were accurate and have assured the insurer that the provider’s costs will be be based on clinical best practices and high capacity utilization. Over time, as more provider organizations agree to outcome-based bundles, Harvard Pilgrim believes an informed market will introduce competitive pressures to sustain a fair sharing of value between providers and insurers.

All participants have been impressed by the collaborative ethos of the working group. Conversations are open and frank. Rather than a traditional negotiation about who bears which costs, the face-to-face interactions have built trust that is enabling the insurer and physicians to arrive at a win-win value-based solution.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

Health Insurance Exchanges Fulfill Both Liberal and Conservative Goals

Reimagining Primary Care: When Small Is Beautiful

Getting Big Results from a Small Business Unit

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers