Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1541

October 1, 2013

Health Insurance Exchanges Fulfill Both Liberal and Conservative Goals

The new health insurance market places—the exchanges set up under Obamacare—have become the hot health policy topic. Will they work or won’t they? The focus is on the near term. And no one should doubt that what happens in the next few months is extremely important—as former cabinet officer Wilbur Cohen said, good policy is 1% inspiration and 99% implementation. Vital though near-term effectiveness is, the exchanges hold a longer-term potential—they can help reshape the organization, delivery, and financing of insurance. Simply put, we think that the health insurance exchange—supported at various times by both liberals and conservatives—may well fulfill the health reform dreams of both. To see why, one need only recall what conservatives and liberals want.

Conservatives want people to be free to choose the insurance plan that best matches their preferences. They want insurers to compete with one another on the basis of price and service. They are convinced that if people can shop freely for the plans they want and insurers must compete actively for their business, everyone will gain: customers will get coverage that matches their preferences, and insurers will become more cost- and quality-conscious than they now are. Conservatives also recognize that many people will need financial help in order to afford health insurance, and they have embraced such aid.

Liberals want universal coverage. While they accept competition, they believe that regulations are also necessary to hold down the growth of health care spending and promote the adoption of improved modes of delivering care. Liberals believe that market pressures, by themselves, will be too weak to prevent hospitals, doctors, and other providers from sustaining what economists call ‘rent seeking’ activities. Left to voluntary action, system-wide reforms, such as the adoption of health information technology and new provider payment practices that lower costs and increase quality of care, will proceed with glacial slowness.

The health insurance exchanges have the potential to fulfill the hopes of both conservatives and liberals. By design, the exchanges will intensify competition by requiring insurers to offer the full range of plans to customers. By providing software and counseling, the exchanges will help consumers make informed comparisons among these offerings. The exchanges will initially serve only individuals and employees of companies with no more than 50 employees. But in 2016 the exchanges will open to companies with 51 to 100 employees. In 2017, they may open up to still larger businesses and to state and local governments. If the exchanges do a good job, most businesses may well be glad to rid themselves of administering a vexatious form of compensation that has nothing to do with their main business activities. If and when that happens, the exchanges will have become the instrument for realizing the conservative dream—free individual choice and tough, head-to-head competition among health insurers.

To do a good job the exchanges have at hand a number of important regulatory powers along lines that liberals have long endorsed. To prevent information overload, the exchanges can protect consumers from being overwhelmed with plans that have no meaningful difference. The exchanges can require insurers to offer certain standardized plans so that customers can easily compare price and service. They can set standards for the quality of care paid for by plans, bar plans that do not meet quality or price standards, and selectively contract with those that do. They can post data on the quality of care provided by hospitals, physicians, and others. They can advertise such information to help consumers make informed choices or, more aggressively, require plans to offer incentives for people to use high-quality, low-cost health care services and providers. Exchanges could also create incentives for insurers to encourage or require providers to apply research findings from analyses of comparative effectiveness.

In addition, the Affordable Care Act has set in motion a large number of pilot programs, experiments, and demonstration projects involving new methods of paying for care and organizing providers. These innovations include bundled payments and accountable care organizations. Not all of these innovations will succeed. But if some do, the exchanges will be in a position to encourage or require their adoption. And if exchanges cover a sizable fraction of the insured population, they will have the clout to change the delivery system. (For further discussion, see our Perspective article entitled “Only the Beginning – What’s Next at the Health Insurance Exchanges?” in the September 26, 2013 New England Journal of Medicine.)

Many conservatives still decry the ACA. Many liberals still regret that health reform did not include a public option or was not Medicare for all. We think that conservatives and liberals alike are failing to see that the ACA holds the seeds of fulfillment for the core objectives each has long sought.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

Reimagining Primary Care: When Small Is Beautiful

Getting Big Results from a Small Business Unit

How We Revolutionized Our Emergency Department

September 30, 2013

The Importance of Spatial Thinking Now

In its 375 years, Harvard has only ever eliminated one entire academic program. If you had to guess, what program do you think that was and when was it killed off?

The answer: Harvard eradicated its Geography Department in the 1940s, and many universities followed suit.

The timing couldn’t have been worse, really. Shortly after the elimination of Geography here at Harvard, the discipline underwent a quantitative and computational revolution that eventually produced innovations like Google Maps and global positioning systems, to name just two. Seventy years later we are paying for a prolonged lack of spatial thinking at American universities. There are too few classes that enable learners to improve their spatial reasoning abilities, with maps and visualizations being of course the most central artifacts to such improvements. The problem is simple: not enough people know how to make maps or handle spatial data sets.

In the meantime, spatial thinking, visualization, contemporary cartography, and the other core competencies of geographic education have never been more relevant or necessary. As this forum has made clear, data visualization is an emerging, important discipline, and spatial thinking—geography—is a fundamental skill for good data visualization.

When talking about data visualization many begin with the assumption that it’s a new thing, freshly formed in this big data era. Visualization is not new, and it’s much older than the “Napoleon’s March” example cited by Edward Tufte as the best information graphic. For centuries, people have measured and mapped out worldly phenomena. We were collecting and mapping information long before the printing press. Libraries supply us with limitless evidence of visualization masterpieces that predate any automated computation, let alone big data, like Gerardus Mercator’s revolutionary map of the world in 1569:

That’s not to say nothing’s new about this moment in time. What is new is the recent integration of spatial thinking and computing. The current rise of what I prefer to call computational visualization is an obvious and logical extension of human practices that are as old as lines in the sand. But this idea that visualization is new hinders teaching and learning about the act of visualization. Without the proper context, “dataviz” discussions and “data science” curricula neglect the important lessons and huge contributions from the past, contributions that can inform everything from design principles to teaching and learning.

As I look out on the world of data visualization, I see a lot of reinventing of the wheel precisely because so many young, talented visualizers lack geographical training. Those interested in a 21st century career in visualization can definitely learn a lot from 20th century geographers like Jacques Bertin, Terry Slocum, and Cynthia Brewer, and they will identify pre-existing principles, cognate scholarship, and countless masterpieces that are extremely useful guides.

Which brings us back to the sheer lack of geographical training available. Recommitting to a geography curriculum in both our high schools and universities will be crucial to effectively developing a generation of great data visualizers who can tackle our challenges. Quantitative spatial analytics offer vital insights into the world’s most important domains including public health, the environment, the global economy, and warfare.

Without geography—or any teaching that emphasizes spatial thinking—the focus will remain on the data, and that’s a mistake. Yes, data are undeniably important but they are not holy. Data are middlemen. Even the term “data visualization” overemphasizes the role of the middleman, and mischaracterizes the objective of the activity. Nobody wants to see data; nobody learns from that. The best visualizations never celebrate the data; instead they make us learn about worldly phenomena and forget about the data. After all, who looks at the Mona Lisa to think about the paints?

Which Management Style Will China Adopt?

The three nations that, in one way or another, lead the global economy at the moment are the United States, Germany and China. They lead it in very different ways.

For the United States and Germany, strong multinational corporations and technological innovation are the driving factors. In the case of the U.S., innovation is driven by a can-do spirit and a healthy appetite for risk, with established corporations and startups introducing some of the world’s most important and game-changing technologies. In Germany, a commitment to product quality and engineering excellence has been key both for multinationals and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Up to this point, China’s economic development has been focused on cost competitiveness and the adoption of foreign-developed technologies and innovations. Its global impact has been due mainly to its massive scale. The global financial crisis, however, marked the beginning of a new period in China’s economic history. China can no longer rely predominantly on foreign consumption as an engine for growth. It has to develop domestic consumer markets and orient its production towards them. Furthermore, rising wage costs make it highly unlikely that China can continue to grow by being the factory for many of the world’s simpler products.

To move itself forward and to move up the value chain, China needs to begin developing a management system and, more important, a culture for technological and product innovation. Germany and the U.S. offer the two main — and quite contrasting — models.

The U.S. business community benefits from a long tradition of newcomers taking risks on entirely new product categories and technologies and leapfrogging companies that have lost their competitive edge. One need only look at the technology industry for a basic idea of how this plays out. Another trait of U.S. firms is that decisions are usually made in a top-down fashion, depending only on one or a few leaders’ approval, which can allow for rapid adaptation and changes in direction.

The advantages of the U.S. approach to managing innovation are quicker market penetration of new products, broad brand recognition in new markets, and attention to customer feedback which can be used to improve future generations of products. The weakness, one could argue, is that product quality may suffer, leaving the door open for other firms (possibly from other nations) to step in.

German corporations have historically been big innovators in terms of technology and product quality. However, because of cultural resistance to risk and a widespread preference for stability, larger German corporations of late have not been able to capitalize on new ideas to as great a degree as American ones. Management in German firms is also much more horizontally organized. If a decision is to be made, it must be approved in a time-consuming process by multiple individuals or groups. Even after it’s been decided at the top, the process may be slowed by levels below if there is insufficient buy in. (These traits are less pronounced with Germany’s more nimble SMEs.)

The advantages of the German approach to managing innovation are high product quality and well-thought-out services that accompany those products. The downside is that new products can be late to market, and truly disruptive innovations few. Even when German companies come up with disruptive ideas, they can miss discovering their immense market potential (witness the saga of the German-invented MP3 player). Disruption and rapid scaling-up seem to fit better with the U.S. psyche. It is important to keep in mind, though, that as far as market and sales potential are concerned, the German approach — while more restrained — can be lucrative and self-sustaining.

What does this mean with regard to China’s future path? In both the U.S. and Germany, the argument is often made that the freer people are in a society or an economy, the more innovation is likely to result. Innovation is bound to happen when people are taught from a young age to challenge the norm. However, the democracy-innovation nexus should not be overstated. Historically speaking, German companies displayed an innovative spirit long before the country was a democracy. That suggests that democracy is not necessarily a requirement for innovation.

That part of the historic record sounds like potential good news for today’s China. But it is crucial to recall what Germany did have as assets at the time: a strong engineering tradition, a strong adherence to the rule of law as well as a quickly rising focus on intellectual property rights. On that basis, risk taking and innovation were properly rewarded. Today’s China, though, does not yet have the engineering and legal traditions Germany has. It also still lacks on the other key ingredients in the innovation formula.

How about Chinese firms finding inspiration in the U.S. model? The trait that Chinese firms share with U.S. ones is the ability and inclination to bring a new product to market quickly, although generally still at a low level of product sophistication. Where Chinese firms still have a lot of catching up to do is in making adjustments based on customer feedback after a product hits the market. Bringing a new product to market rapidly and improving its quality based on empirical evidence from customers is the true value of the U.S. approach. It stands to reason that Chinese firms will manage to absorb that lesson before long. The continental size of the Chinese market and the increasing sophistication and quality demands of Chinese consumers will likely ensure that.

Still, that does not yet solve Chinese firms’ problems of indigenous innovation. The big question is whether they can find their own equivalent of the Yankee spirit of going for radical product innovation, or develop something more like the German model of constant innovation to keep one’s products on the cutting edge globally.

All that can be reliably said at this stage is that Chinese leaders recognize the challenge. They have begun a process of encouraging innovation and are revamping educational structures and priorities. Some of China’s leading universities have started up programs dedicated to honing the innovation potential of the country’s future managers.

It’s also likely that both the “German” and “American” approaches to management are going to be practiced in China. The country’s state-owned enterprises, whether partly privatized yet or not, are more “German” in their character. They have to obtain a lot of buy-in, including from political stakeholders, and thus are likely to follow a more slow-moving, horizontal management approach. In contrast, privately owned firms in China are bound to follow the more nimble top-down U.S. model.

The ultimate outcome of China’s corporate and innovation journey of course remains highly uncertain. One thing is for sure, though — it will be fascinating to watch.

Implementing Innovation: Segment Your Non-Customers

Some of the most successful and disruptive innovations stem from a company’s ability to tap into demand from non-customers in its market category. The challenge, of course, is to identify why these people aren’t customers already. Once you know why potential customers aren’t buying your product, you can develop innovations to make your product more appealing to them.

Unfortunately, a focus on known customers and share of the existing market is ingrained in the processes and metrics of companies. As a result, they have less systematized data about their noncustomers. You can improve the odds on succeeding through innovation if you fix this data problem by treating non-customers as a segmentation problem and apply some of the discipline of marketing research.

The key is to segment according to reasons for not buying products in your category. In my experience, these typically fall into one of six categories:

Economic: People lack access to cash or credit

Functional: The product does not help people achieve what they want to achieve

Educational: People don’t know how to use the product or even what it can do

Access: People can’t buy the product because it is not readily available to them

Social: The product doesn’t conform to religious or social norms

Emotional: The product triggers negative emotions.

The global swimwear company Arena used this categorization as a framework for segmenting non-customers. They first hypothesized a list of non-swimmers, then they analyzed the barriers inhibiting the potential demand of each segment, and finally they developed a set of new products that could overcome some of these barriers.

One attractive segment they identified were beginners who went to the pool a few times and then gave up. The principal problem for this group was functional: they struggled to develop good breathing technique. Breathing is perhaps the biggest challenge for novice swimmers. Poor breathing creates problems with executing strokes, making it harder to move comfortably in the water. It is one of the most common reasons that novices give up learning to swim and turn to non-water gym activities.

This insight led Arena to develop a new device, called the Freestyle Breather, a pair of plastic “foils” or “fins” that can be attached to most marketed goggles. The Freestyle Breather has three main functions: it facilitates inhalation by enhancing the bow wave, making it easier to breathe into the air pocket; it secures inhalation by protecting the mouth and nose from splashes and water drops; and it reduces over-rotation of the head and body because swimmers feel less anxiety and risk of breathing water.

Swimming with a Freestyle Breather makes the pool experience so much easier for beginners that it has the potential to convert many novices into regulars at their local pool. Arena reckons that there’s potential to more than double the global population of regular swimmers.

Another segment Arena identified was Muslim females, who experience social barriers to swimming. They want to be able to move fluidly in the water but they can only swim when their body is fully covered. Unfortunately, swimming in traditional cotton bodysuits is uncomfortable both during the swim and after (cotton body suits take a long time to dry off). After studying groups of Muslim women using the traditional swimsuits, Arena applied its expertise in performance materials to design a line of swimwear that conformed to religious norms, was comfortable in the water, and dried quickly.

Of course, you won’t capture all your potential marketspace through this exercise. But if Arena’s experience is anything to go by, simply sorting non-customers into the categories described here and analyzing barriers blocking potential demand gets you a very long way. Companies should be doing more of it.

Executing on Innovation

An HBR Insight Center

Why Large Companies Struggle With Business Model Innovation

Innovation Isn’t Just About New Products

Three Signs That You Should Kill an Innovative Idea

We Need a New Approach to Solve the Innovation Talent Gap

Reimagining Primary Care: When Small Is Beautiful

The attempts to “fix” the U.S. healthcare system have taken at least one well-worn market-based path: strive for economies of scale. Hospital consolidation is on the rise, a trend that shows no signs of abating as providers try to streamline back-end operations and deploy big data analytics in hopes of improving outcomes and lowering costs. Businesses try this every day.

However some primary care physicians are looking at the exact opposite approach: de-scaling and taking cost out by radically simplifying their practices as a way to make them clinically, financially, and personally sustainable.

What makes these practices different? 1) Each is based on relationship quality rather than production volume; as a result, each is smaller than the average U.S. practice; 2) Visits are longer and the doctor may provide a broader range of services with minimal support staff; 3) They have business plans that demonstrate how their model can be financially sustainable; and 4) Each used their variation on the general model to offer greater satisfaction to their patients as well as to their own personal and professional lives.

My colleagues Leonard Marcus, Barry Dorn, and I met three such physicians in the course of researching our book, Renegotiating Healthcare: Resolving Conflict to Build Collaboration. We recently revisited them to see how the evolution of their distinct approaches to primary care might inform the larger discussion of the future of healthcare.

Dr. Pamela Wible of Eugene, Oregon, had considered leaving medicine. She contemplated waiting tables so that she could have more meaningful interactions with people. She was burning out working in a typical large practice with its fast-turn appointments and gatekeeper-to-specialists role for the primary care provider. Instead of tying on an apron and heading to the local diner, she turned to her patients and asked them to help her reimagine a model medical practice. They gave her more than 100 pages of ideas.

The result is something as unlike the typical primary care practice as you can imagine: It is a living room-like setting with minimal electronic equipment. Wible is the only staff. Patients never have to wait in a waiting room. Appointments start on time and are 30 to 60 minutes long. Conversation and physical touch are central to diagnosis. Wible chose to cut the size of her practice to restore some balance to her life and to have more meaningful relationships with her patients. Thanks to lower overhead, she is able to earn a full-time salary working part time. ”It’s actually very easy to run a solo ideal medical clinic in 2013,” she said. She now consults with physicians and hospitals nationwide as they learn to design true patient-centered practices.

Dr. Gordon Moore of Rochester, New York traveled a parallel path. He could not see a way toward a viable financial future given the expenses of a traditional primary care practice with a large support staff. Like Wible, he decided to practice solo to minimize costs though he eventually added a nurse when his practice reached 400 patients. Even with the additional duties of scheduling, greeting, and billing, he found that he could spend more time with patients and was deriving great personal and professional satisfaction from these relationships. He made himself available 24/7 to his patients yet they called him less than when he was the on-call physician in a larger practice; he granted full access to them and they, in return, were greatly respectful of his time.

Moore left his practice in 2008 to help build a movement around what is called the Ideal Medical Practices or IMP. Not limited to solo practitioners, IMP rests on the pillars of access to care, time for relationship to build, and comprehensive, coordinated care and services. Patient experience is the critical variable for both controlling costs, improving outcomes, and keeping physician caseload manageable. There are now 500 IMP practices nationwide.

Dr. Richard Donahue had been the only year round physician on the island of Vinal Haven, Maine for a decade. He said that his patients frequently told him that if he couldn’t treat something, they’d learn to live with it rather than incur the expense and take the time to travel to the mainland for treatment by a specialist. He said that this pushed him to continually improve and expand his skills so that he could meet patient needs. He has taken his “island doc” philosophy to the city and is currently Medical Director of a family-oriented concierge practice that serves “CEOs to social workers” in Boston.

There are, of course, challenges. According to Dr. John Brady of Ideal Medical Practices, these are often administrative as initiatives such as basing payment on productivity do not take alternative practice models into account. It can also be harder for small independent or solo practices to coordinate care with a large hospital system or specialists. However these can usually be overcome through planning, technology, and tenaciousness.

Practices like these are a tiny minority yet they highlight important issues for our health care system. First is that a system designed by policy makers and business interests may look markedly different from how two critical stakeholders envision it: doctors and their patients. Those differences may have implications for both costs and outcomes. Second, when patients have a meaningful, trust-based relationship with their primary caregiver, they may actually ask less of the overall system: fewer optional tests and unnecessary trips to the emergency room, for example. Third, it may be useful to ask primary care physicians to do more for fewer patients.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

Getting Big Results from a Small Business Unit

How We Revolutionized Our Emergency Department

How to Get Health Care Innovations to Take Off

Time to Hang Up on Voice Mail

Who writes with fountain pens? When did you last prepare transparencies or exchange faxes? RIM? RIP. Sic transit gloria mundi. When once-innovative technologies descend—decay?—into anachronism, it’s time to put them out of your misery. Disconnect enterprise voice mail. Now. Be honest—you don’t really want to leave a 90-second message after the beep and you certainly don’t care to listen to one. You’ve got faster, better and friendlier ways to communicate.

You’re already using them. There’s not a Fortune 2000 enterprise worldwide that wouldn’t enjoy a healthy productivity jolt by ridding itself of this tool that’s degenerated into handicap. Who do you know in your organization uses it well? By contrast, which colleagues leave voicemails secure in the knowledge that you will never—ever—retrieve them? (Surely you would never do such an ambiguously unethical thing….)

That the technology is in decline is no secret. In 2012, Vonage reported its year-over-year voicemail volumes dropped 8%. More revealing, the number of people bothering to retrieve those messages plummeted 14%. More and more personal and corporate voicemail boxes now warn callers that their messages are rarely retrieved and that they’re better off sending emails or texts. Consequently, informal individual policies have metastasized into de facto institutional practice. Is that wise?

The truly productive have effectively abandoned voicemail, preferring to visually track who’s called them on their mobiles. Irritated office workers, by contrast, despair that their desk phones can’t display who’s called and when. They’d be far better off if office calls were forwarded to their devices with the relevant Caller IDs attached. Yes, unified communications protocols and technologies were supposed to address these gaps but they’re taking an inordinately long time to do so as other messaging alternatives improve. Google Voice and other audio-to-text transcription services could also obviate the aural inefficiencies but, frankly, few organizations have bothered to make that investment.

The result is the worst of both worlds: A legacy system drag on organizational productivity and individual confusion around the technology’s role and relevance in getting work done. That’s wasteful. What’s worse, it signals enterprise laziness and complacency. What’s the big deal? If people want to call, they’ll call; if the want to text, they’ll text; if they want to email, they’ll email. More choice is used as an excuse for not thinking through how individuals and teams should be productively communicating.

Focus and ingenuity come as much from useful constraints as usable options. Back when I did use voice mail, the most important constraint I implemented was limiting messages to no more than 30 seconds. I had friends and colleagues who were leaving one, two and even 4 minute messages. This wasn’t good when you’re calling in between flights. Now, of course, the only voicemails I listen to are from people I don’t know. (Talk about inefficient!)

Which raises a provocative point: For most organizations, the only people who matter going into voicemail are customers and clients! How smart and customer-centric is that?! Not very. Voicemail’s technical flaws and shortcomings reveal something very important about the customer engagement future. Nobody wants to be put in voicemail anymore and it’s quite likely that customers and clients aren’t listening to your voicemail messages either.

But for everyone inside the firewall, it’s long past time to end the futile and time-wasting games of telephone tag. A communications medium that was once essential has become as clunky and irrelevant as Microsoft DOS and carbon paper. You want to have better, faster and more responsive communications inside your organization and save some money besides? Have an online conversation about online communications—and unplug your voicemail system. If you’ve got a problem with that, don’t bother to comment. But do feel free to call me and leave a message.

The Act of Choosing a Treatment May Boost Its Effect on You

For people who have a need to feel in control, making a choice about health treatments strengthens their chosen treatment’s psychological component, says a team led by Andrew L. Geers of the University of Toledo in Ohio. For example, people who put a hand in ice water for 75 seconds reported less pain (20 versus 24 on a scale up to 44) if they were given a bogus pain-prevention cream; but for high scorers on a “desire for control” test, the effect was more pronounced if they were able to select between two (equally bogus) creams. The findings are part of a growing body of research showing that patient involvement enhances treatment effectiveness.

Can Internal Crowdfunding Help Companies Surface Their Best Ideas?

Crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter and Indiegogo have proven adept at channeling funding – millions of dollars in cases like the Pebble watch – to innovative new products and projects, often by previously unknown inventors and designers. Can larger companies employ the same type of system to find and fund internal innovation?

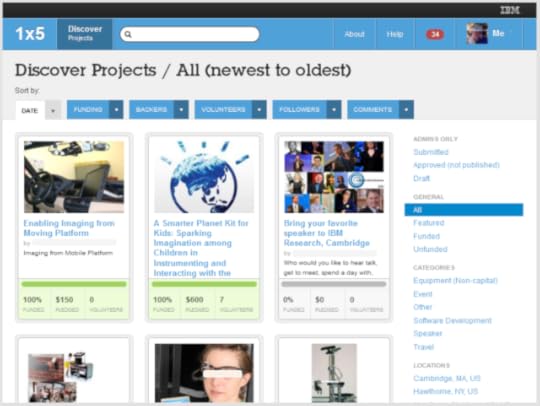

IBM has been experimenting with such “enterprise crowdfunding,” where the company gives its employees a small budget and encourages them to commit it to each others’ proposed projects. The experiments are the subject of an academic paper by IBM researchers, and the results have been promising, with a few surprises – crowdfunding may help improve morale, for instance. I spoke with one of the authors, Michael Muller about what he and his team have discovered. Following is an edited version of our conversation.

Tell us a bit about the experiments with crowdfunding at IBM.

IBM has been interested in finding different ways to support innovation inside of companies — inside of IBM and inside of clients companies — for a long time. When we bring it inside the enterprise, what we call enterprise crowdfunding, several things are different.

Number one, we don’t have people use their own money An executive allocates a budget to the participants in the experiment. In our first case, a vice president in research allocated $100 to each of the 500 people in his organization. There was a website that was inspired by Internet crowdfunding websites, where members of the organization could propose projects, and members of the organization could take their $100 and spend it on each others’ projects. The trial lasted about a month and the funds where available on a use-it-or-lose-it basis, meaning you could only spend it on somebody else, not on yourself. And at the end of the trial, if you didn’t spend the money you didn’t get to keep it. A second trial in research was at IBM’s Almaden research center [in San Jose, California]. The third trial was in a relatively large IT part of IBM, roughly 5500 people strong.

What kinds of projects were funded?

Many addressed a bunch of technical challenges that we have been having. I don’t think they were new inventions here so much as they were making technology available so that people could have new thoughts around the technology which would then lead to inventions, we hoped. In the first research project people had said that they needed access to a micro-tasking site — an example of this would be Mechanical Turk — and it was hard to negotiate how to do those payments through the standard IBM channels. It was funded and the vice president moved heaven and earth to get that through the IBM purchasing organization. And I have seen conference papers based on the data that were collected through the use of that particular set up. In that case, not only did the project go through, but it’s enabling useful research.

There were also some other projects that addressed morale issues and the culture.

Several of the proposals had to do with things that people would have to do together in order to participate in it. One was “afternoon beverages”. It was at a standard time and if you came for afternoon beverages you are going to talk to you peers and network. Another was simple small-scale pieces of athletic equipment, generally speaking for shared use. The theme seemed to be over and over again, ‘We’ll do this together, we’ll use this together, we’ll talk to each other, we’ll meet each other.’

What was participation like?

We ran this really not knowing what to expect. We knew the standard figures for social media, where about 10% of the people would be pretty active, or at least somewhat active. Then the 90% of the people would maybe occasionally contribute or mostly look around to see what was going on. We had those kinds of expectations in mind, and what happened really surprised us: we had well over 45% participation.

We had thought, well maybe it’s going to be the case that the higher you are in the organization — the more influential you are — the more likely you are to get funding. We found the reverse, actually. People as high as IBM fellows were making proposals that did not get funded; it was really grassroots. Since then we have done two other trials and in one of them the effect of rank in the organization was a complete wash, no statistical effect at all.

You found considerable participation across geographies, correct?

Unlike the two research groups, the IT group from the third experiment was geographically distributed across 29 countries and a bunch of different divisions. We thought maybe geography will get in the way, and we found that people collaborated pretty easily across geographical boundaries. For a proposal that was successfully funded, it was well over eight countries among the various investors.

We felt maybe even though geography didn’t get in the way, maybe people sharing a common geography might still give an extra oomph, and it turned out that [it] did. If you share the country you are a bit more likely to invest. A few other “things-in-common” worked similarly. If you share the division you are more likely to invest. If you are on the same large-scale international working group or team you are a bit more likely to invest. But none of these stopped people, they just gave people an additional encouragement.

What can you say about the motivation of the participants?

Especially on sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo, people often invest in order to get something. Many of the product-oriented projects are actually kind of a pre-order, like the famous Pebble watch. We made available to people the ability to specify that if you invest $10 of the money that the vice president gave you, than you’ll get this, if you invest $50 you’ll get that. It turned out very little of that seems to matter to people. What matters to people is that they can see shared utility amongst themselves, or for clients, or for IBM, or for customers. When we did this project with the IT department, everybody we interviewed knew exactly who is going to benefit from the project; it was almost uncanny the way that they had worked it out. Within the research organization people said things like, ‘There are projects here that can benefit all of us’; ‘I need access to these resources and I am not the only one.’ The individualistic model based on Internet experiences was transformed, behind the firewall, in to a series of community projects.

What about follow-through on the projects? And how did you deal with the allotment of staff time toward funded projects?

Not everything is completed — I think more than 50% is — but we don’t have as accurate a tracking on that as I wish we did. In the Research crowdfunding trials, if people got their funding, then they had to run the projects while they still did the rest of their jobs.

The IT department was again different. By allowing you to propose the project they were making a commitment that they could spare you for some percentage of your time, if the project was approved.

So what do we know about where this will work?

If the individual budget for a person is $100 or is $2,000, it works. If the domain of the projects you can propose is wide open, or if it is limited to software technology innovation projects, it works. It works if there is no limit on how much or how little a budget can be, or if there are strict rules. It seems to be very flexible.

What don’t we yet know?

We don’t know how big is too big, how little is too little. We don’t really have a sense yet of what correct amount of money to allocate per person in order to get a budget spent. I think we want to do more work on your question, which was a follow-through question. Are there projects that are doomed at the outset and shouldn’t be allowed in? We don’t know that yet. We think that enterprise crowdfunding increases employee engagement, but we don’t really have the numbers to prove that.

What advice would you give companies who want to try this?

It’s important for the sponsor to say what kind of innovation he or she wants to see, and what is out of bounds. Also, organizations should actively campaign to get everybody involved, otherwise money doesn’t get spent, which can at least be fixed by over allocating the money. People should be considering not why the project would be good for them or for a narrow little slice of people, but what the community value of the project is.

We also need active campaigns by the project proposer, and people were extremely ingenious. One of my favorite examples was that the people promoting a 3D printer put up signs next to all of the regular printers, saying: ‘Don’t you wish you were printing on a 3D printer right now?’ They got funded. There was a project in the Almaden research centers in which, because there are some remote members of that organization, people wanted to set up social robotics, a robot on wheels that could run around the corridors and be the social presence of the remote researcher. They went out and borrowed one, and it went up and down in the corridors and advertised the project. And they got funded.

It was definitely the wisdom of the crowd speaking here. One of our old IBM mantras goes: ‘None of us is as smart as all of us.’ We really need all of our brains engaged on these things.

Executing on Innovation

An HBR Insight Center

Why Large Companies Struggle With Business Model Innovation

Innovation Isn’t Just About New Products

Three Signs That You Should Kill an Innovative Idea

We Need a New Approach to Solve the Innovation Talent Gap

September 27, 2013

Story-driven Data Analysis

Great analysts tell great stories based on the results of their analyses. Stories, after all, make results user-friendly, more conducive to decision-making, and more persuasive.

But that is not the only reason to use stories. Time and time again in our experience, stories have been more than an afterthought; they have actually enabled a more rigorous analysis of data in the first place. Stories allow the analysts to construct a set of hypotheses and provide a map for investigating the data.

We recently worked with a department store retailer and a team of analysts looking for creative insights into customer loyalty. Based on our work with a department store expert, we started out with a storyline, a narrative hypothesis, according to which a customer experiences different journeys through the department store over time and rewards the retailer with a certain level of loyalty.

How will these journeys unfold? Does the customer start in cosmetics and then move into clothing? Does she go from the second floor to the first floor to buy a handbag to match a new outfit? Does she have shopping days where she takes a lunch break in the restaurant before continuing her shopping? Do less loyal customers make different journeys from more loyal ones?

In other words, we were interested not just in what customers were buying, but in the mechanics of how they make their purchases and how this may make them loyal. After the analysis, the true story of a customer’s path to loyalty is in fact revealed.

Where do these stories come from? In our experience, they can come either from the experience of an expert in the sector or brand, as was the case in the previous example, or from qualitative research using observation or in-depth interviews.

We recently advised a telco client in developing the “jobs to be done” for a range of new products and services. We interviewed consumers and heard their own stories of how they go about using their mobile devices throughout the day. The general narrative hypothesis we drew from listening to these stories is that consumers cobble together mobile solutions to suit their lifestyles.

One consumer revealed that he actually owns two SIM cards for the same smartphone and told us in what context he changes from one to the other. Another customer told us about the parental control and other relevant apps and browsing that she has discovered and collected and which facilitate her lifestyle as a mother.

What we are seeing here is a multi-usage context (characterized by two SIM cards) and a “Mobile Mommy” context, each of which calls for a distinct analysis and possibly different products/services to be developed subsequently. In other words, we found that the customers’ homemade solutions could be used by brand managers to identify what kind of data to gather and what kind of analysis to perform.

The analyses will in their turn enrich the initial stories and lead to deeper insights. What is important here is that the storyline, told before the analyses, enables an authentic human element to surface that would be more difficult to extract from the data alone

In order for a story to truly enable analytics, the story development process needs to be rigorous. We use the framework of Grounded Theory to ensure that the data and overarching storyline inform each other and are coherent with each other. The idea is for the analyst to navigate back and forth between the data and the developing story to ensure a good balance between the creative narrative and the analytics that reveal the facts and details of the story.

The enabling storyline should not be too restrictive: it needs to support the development of the plot and characters as they emerge from the analysis, but without bias. Conversely, the storyline can suggest specific questions to be asked of the data for a more in-depth analysis.

In a world that’s flooded with data it becomes harder to use the data; there’s too much of it to make sense of unless you come to the data with an insight or hypothesis to test. Building stories provides a good framework in which to do that.

Design Lessons From iOS 7

With over 200 million devices upgraded to Apple’s iOS 7 in just five days, it is clear that Apple has another success on its hands. Revamped in just eight months (an unheard of timeframe for an OS redesign), iOS 7 represents the first major software release under Sir Jony Ive’s leadership of Apple’s software group. Throughout the new OS, his influence is easily identifiable, in both good ways and bad.

iOS 7 represents a final and emphatic break from skeuomorphism – design that takes its cues from physical objects — something that has been a raging debate in design circles for years. (You can read about it here, here, here, and here.) But within this break from skeuomorphism lies a great commitment to realism. This iteration of iOS is easily the most intricately tied to the iPhone hardware. Its connections to the sensors of the device allow it to behave according to the laws of physics, making it feel of this world, as opposed to drawing on simple visual metaphors.

This, more than anything, represents both the true breakthrough of iOS 7 and is the primary evidence of Sir Ives’ touch. For years, Ive has obsessed as much about the internal construction of Apple hardware as he has over the external design (jump to minute 3:25 of this video to hear him gush about a thermal system). This unrelenting focus on the marriage of a device’s internal workings with its external experience is what gives Apple products their specific appeal and quality. Ive has done the same thing with iOS, obsessing over the internals of the phone and building an operating system that takes the maximum possible advantage of them. The result is an OS that feels alive, responsive, and modern.

Imperfections

But iOS 7 is not perfect. The easiest targets for criticism are the garish color palette and the unreadably-thin typefaces which have inspired their own meme, though they make more sense now that we have seen the color lineup for the iPhone 5C. The icon grid put forth by Ive’s team is mathematically precise, but lacking in many areas digital designers have been refining for years, such as color choice, visual appeal, and metaphor. Finally, Apple continues its stubborn refusal to introduce dynamic information into the top-level experience of the OS. Yes, the control panel is better than before, but Android and Windows Phone are much more dynamic with their home screens, enabling users to gather crucial information without requiring an app to be launched. This lack of glance-able information and user-customizable interfaces is going to become a very real crutch soon enough.

At its core, iOS 7 represents a new foundation for the world’s most profitable mobile platform. And as a first offering, it has great promise. Unfortunately, it does not yet fully live up to its potential, which is how Apple has worked historically. The first generation of OS X was a revolution, but it was laggy and buggy. The first Macbook Air suffered multiple problems before becoming the laptop it is today. Even the first generation of iOS was locked down before establishing the mobile developer ecosystem. This is Apple’s pattern: release a revolutionary experience and then relentlessly iterate and perfect it over time.

Strategic Risks

However, this launch is different than previous efforts and presents two primary risks to Apple. The first is that Apple’s competitors are also building extremely compelling mobile ecosystems. Android, long lamented for its design shortcomings, is starting to gain traction from an experience standpoint, with influential designers like Twitter’s VP of Design, Mike Davidson, adopting the OS for the first time.

Secondly, the rapid adoption of iOS 7 could potentially serve as a negative for the developer community. Updating an application from iOS 6 to iOS 7 requires more than simply updating graphics and preparing the software for the new phones. iOS 7 is fundamentally different and requires some serious rework to ensure that an application feels native to the system. This level of effort should be compensated, and indeed some developers are gearing up to charge for their iOS 7 apps, but consumers have been conditioned to getting OS upgrades for free and the press is already calling out developers for “double dipping”. One party in this exchange is bound to feel frustrated. The consumer will be unwilling to pay and the developer may be frustrated at giving so much work away. With Android continuing its marketshare dominance and Windows Phone finally emerging as a viable option, this could represent an inflection point where more developers begin looking at other platforms first.

After six years of iteration on the original iPhone OS, iOS 7 is a refreshing reset. Without a doubt, Apple’s new operating system will look and feel dramatically different a year from now. It will take advantage of the hardware in new and innovative ways and has the potential to once again reshape our expectations of what our mobile devices are capable of. The big question for Apple will be whether or not consumers are willing to travel along this road of iteration once more.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers