Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1545

September 23, 2013

How to Make a Job Sharing Situation Work

Job sharing — splitting a full-time position into two part-time jobs — is an increasingly popular flexible work arrangement. But is it really possible to share a job with another person? How can you make what looks good on paper work in reality?

What the Experts Say

“There are a wide variety of reasons to choose a job sharing arrangement — it might be to take care of a dependent, to work another job, or to advance one’s education,” says Stew Friedman, a professor of management at the Wharton School and author of Total Leadership: Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life. Lotte Bailyn, a professor of management at MIT’s Sloan School of Management and co-author of Beyond Work-Family Balance: Advancing Gender Equity and Workplace Performance, agrees, noting that people often pursue a job share because they want less stress in their lives. Whatever your reason, it’s up to you (and your partner) to make the situation work. Joan Williams, a law professor and the founding director of the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California’s Hastings College of the Law, believes that any job can be shared if done intelligently and thoughtfully. Here’s how:

Choose the right partner

If you have a say in the matter, be sure to select someone with whom you can easily communicate, collaborate, and disagree. These arrangements often require difficult conversations about prioritizing work, office politics, and personal matters so you want to be sure you pick someone compatible. But don’t seek out your perfect clone either. These situations work best for you — and for the company — says Bailyn, if the job sharers have complementary skills, experience, and perspectives.

Decide how to divide up the work

“There are a number of ways to slice any given job,” says Williams. “It’s important to conceptualize all different parts and divide them up in the most effective way.” Some people split the work by each taking responsibility for certain tasks. This is called the “islands model” or a “job split.” Others share the same workload and simply divide up the days (usually with a bit of overlap). This is called the “twins model” and is often the simpler of the two. The model you choose will depend on the nature of the job and what preferences and skills each of you bring to it.

Communicate, communicate, communicate

“For job-sharing to work well, both parties must zealously convey and seek information from the other,” says Friedman. “Think ‘mind meld.’” Ideally this communication should happen face-to-face, says Bailyn, but many job sharers use other ways to connect, including email, phone, and Skype. Use this time to agree on work priorities, discuss any issues that have come up, pass off work if necessary, and check in about how things are going generally. “You can’t leave anything unspoken. It has to be very explicit,” says Williams.

Secure your supervisor’s support

If you proposed the arrangement, make sure your boss is onboard. “It’s possible to be successful in an organization that doesn’t generally support job sharing but not if your manager is against it,” says Williams. “If your supervisor doesn’t support it, it’s probably not going to work.” Ask your boss for feedback regularly. Be vigilant about communicating with her about the arrangement. When Friedman was a senior executive at Ford Motor Company, a pair of his direct reports shared a job. “What made it work so well was their willingness to go the extra mile to keep me and others informed about how they were coordinating their work; this gave all those involved a sense of confidence and trust that this was a good deal not just for the job-sharers but for our company,” he says.

Manage expectations and perceptions

Indeed, it’s not only your boss who needs to be informed. Anyone you work with—colleagues, clients, vendors—needs to know how to reach each of you and who they can expect to respond when. Some job sharers will share an email account and phone number. Others automatically cc their other half when responding to any email. The key is to make sure it’s a seamless experience for everyone around you. “All those who interact with you should experience a unity of understanding and purpose,” says Friedman. And any time you talk about the arrangement, focus on how it benefits the organization. “The main thrust of communications with co-workers and clients should focus on the benefits to others, especially the ‘two heads are better than one’ argument,” says Friedman. “Others want to know how this set-up will be good for them, not for you.”

Battle the bias

Bailyn says that one of the biggest barriers to making these situations successful is the attitude of others. In fact, some people perceive any flexible arrangement as a sign that you aren’t committed. Williams has observed this stigma in her research at the Center for WorkLife Law. “In most organizations this is seen as an ‘odd duck’ arrangement,” she says. The best way to challenge this bias is to excel at the work. “Make it very clear that you’re meeting the norms the organization has for people who are dedicated to the job,” says Williams.

Give it time

Once you’ve settled on an arrangement that you, your partner, and your boss think will work, try it out. Set a pilot period and experiment with how you split the work and communicate. Then tweak as necessary. “It’s good to give the process a bit of time to work out the kinks and get people used to it. After some experience, most people react positively,” says Bailyn. No matter how long you’ve been sharing a job, it’s a good idea to continually reassess and make adjustments based on what’s working for each of you, your boss, and the organization.

Principles to Remember

Do:

When selecting a partner, choose someone you can easily communicate, collaborate, and disagree with

Ask your boss for feedback regularly — be vigilant about communicating with her about the arrangement

Make sure it’s a seamless experience for your co-workers and anyone outside your organization

Don’t:

Leave anything unspoken — talk to your partner regularly

Assume everyone will be fine with the arrangement — combat bias by excelling at your shared work

Set the details in stone — it’s better to experiment and make adjustments as necessary

Case study #1: Experiment with the arrangement to find what works

Gretchen Anderson had been working as a consultant to the Katzenbach Center at Booz & Company for a few months when the opportunity to take on the role of center director came up. Gretchen knew one of the center’s leaders, Jon Katzenbach — she’d worked at a firm he’d previously founded— and was excited about the opportunity to work with him again. But she was a new mother, and only wanted to work 50% time. Fortunately, another consultant who had been with the firm for almost eight years, Carolin Oelschlegel, was also interested in the position. She was based in London and had recently started working 80% time for lifestyle reasons — “there are so many things I wanted to do outside of work and I wanted the time to do them,” she says.

Gretchen and Carolin spoke once by phone and each had a strong sense that they would work well with the other so agreed to put their collective hat in the ring (each dedicating 50% to the role). Such job-share arrangements are not common at Booz & Company, but the leaders at the Katzenbach Center were eager to make it happen.

Initially, they thought they could split the work by region: Gretchen could cover North America and Carolin would take Europe. But they soon realized that this division felt artificial and ineffective. Next, they tried working on the same projects, passing them back and forth, but that didn’t feel efficient either. Eventually, they decided to carve out two buckets of work: immediate requests from client teams, which required a response within 24-48 hours, and longer term projects.

Immediate requests are now resolved by whoever is available and online at the time. For the longer-term projects, they collectively designate a lead who can bounce the work back to her partner as necessary, relying on the other’s feedback and re-allocating when demands shift or projects end. They manage this hybrid between the “twins” and “islands” model by staying in constant contact: “We’re in touch by email every day, even on Gretchen’s off days and we always know where the other is,” says Carolin.

While they were initially diligent about keeping those around them apprised of how they divided the work, their bosses and co-workers now trust them to sort it out. “How we divide our work is neither of interest nor of concern,” says Gretchen. “They seem to trust that things will happen — and to let us sort it out on our own.”

There have been unexpected benefits to sharing the job as well. For example, since their time is limited, they both push each other to focus on the most important priorities. “We have two peoples’ judgment call on what really needs to get done,” Gretchen says.

Case study #2: Put respect first

Several years back, Ryan Frischmann decided he wanted to get into software development so he applied for a job as a lead developer at a small start-up in Rochester. During his interview, he learned that the role would be shared with a current employee who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. The idea was that they would do the same job until his co-worker got too sick to work or passed away.

Ryan recognized that this was a unique situation but he was willing to give it a try. “I thought it would be a great learning experience personally and professionally,” he says. The arrangement allowed his colleague the flexibility he needed to continue working and gave Ryan the opportunity to learn from a more experienced colleague.

The two men shared the same role and responsibilities — Ryan worked full time at the office while his colleague worked from home when he was able to.

Ryan believes that the most important element in making their relationship work was respect. “I made sure he made the final decision on anything new in the development pipeline,” he says. “My colleague had built the software from scratch. He felt it was an accomplishment and so did I.” Ryan also worked to gain his co-worker’s trust. “I had to demonstrate to him that I understood his coding and methods. When he was sicker, he told me and the others that he was leaving his software in capable hands. This meant a lot to me.”

The job share lasted for nine months before Ryan’s co-worker died, and Ryan has carried on in the role. He says the experience has inspired him. “My partner had a lot of pride in his work and completed some of his best work when he was very sick. I never anticipated the effect it would have on me personally.”

When Big Companies Support Start-ups, Both Make More Money

In the technology world, we’ve seen the tremendous impact that eBay has made in helping small e-commerce businesses get off the ground. Many of them started off selling merchandise from their apartments or homes, and some evolved to become power sellers. Today there are hundreds of thousands of people around the world making their living selling merchandise on eBay. In its turn, eBay has made commissions from every single transaction that has occurred on its platforms.

Now imagine if eBay went beyond providing a technology platform and entered the field of business incubation in a meaningful way, It’s an idea that could have a huge impact. Sellers making $3,000 a month could be coached to get to $15,000 a month. Those making $25,000 a month could perhaps get to $100,000 a month.

Consider, also, Apple and Google. Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android have fueled a global bonanza in app development. Millions of apps have proliferated the world. Some of these generate decent revenues. Most stagnate. But if these two companies took business incubation seriously, and instead of just offering technical guidance on building apps, also offered business guidance, the impact on global GDP would be tremendous.

In the start-up world, there’s a big focus on business incubators such as YCombinator–perhaps too much focus. As we think about the forces that could help more businesses grow into substantial economic engines, it’s important to look at the role that big companies can play, too. Some of them are already providing important platforms that can help small companies get off the ground. But over time, I see the potential for big companies to do much more.

I routinely meet companies that are growing smartly by leveraging platforms provided by big companies. In 2007, I met Kirk Krappe, CEO of a small startup called Apptus. Kirk and his two cofounders Neehar Giri and Nathan Krishnan had earlier done a venture-funded startup called Nextance. Nextance was an enterprise software company providing contract management software. It raised $60 million in venture capital, and eventually failed. The team then decided to take their domain knowledge and start Apptus as a cloud-based contract management software company.

This time round, they decided to take no venture capital. They chose to build the company on Salesforce.com’s Force.com platform, which kept development costs low. The team was able to bootstrap the company, and within a couple of years, shot to $5 million in revenue. Recently, they have received a large influx of funding of $37 million from a group of investors including Salesforce.com.

The beauty of this model is that Salesforce.com has made available a cloud platform-as-a-service upon which entrepreneurs can rapidly and cost-effectively build businesses. The eco-system works really well, and Salesforce.com takes a percentage of the revenues for products built on their platform.

Today, thousands of developers are building on Salesforce.com’s multiple cloud platforms. They all pay royalties to the corporation. Thus, if Salesforce.com were to enter the field of business incubation, helping these companies grow their businesses, the economic benefit would be staggering.

And Salesforce.com itself would also benefit from the increased royalties that would increase their revenues and profits.

The best thing about the corporate incubation model is that it is a win-win for both the corporation and the small business, and it doesn’t have to worry about the startups being fundable by VCs.

Microsoft’s BizSpark program supports 72,000 small businesses building on their various platforms. Oracle’s partner network has a million companies. These massive eco-systems are gold mines of entrepreneurial potential.

As usual, over 99% of these eco-system partners are not venture fundable. But many of them can become $1 million, $5 million, or $20 million a year businesses.

Brian Knight, CEO of Pragmatic Works is one such entrepreneur. Brian has navigated the Microsoft eco-system, and built a $12 million dollar company around the SQL Server platform.

Even on a less mature platform such as SAP’s HANA – a big data analytics platform – entrepreneurs are building significant businesses. Chris Carter, CEO of Approyo, is a great example. Even though SAP only has a couple of thousand entrepreneurs developing on HANA at this point, Chris has already achieved close to a million dollars in revenue developing on it.

Imagine how many Brian Knights, Chris Carters and Kirk Krappes are out there!

If only we could plug the knowledge gaps in these millions of entrepreneurs, and help expand the middle of the pyramid, Capitalism 2.0 would be within reach.

It is, in fact, within reach. Especially, if the corporations wake up and play a bigger part.

We Need a New Approach to Solve the Innovation Talent Gap

My brother-in-law, Joel Murphy, and his brother Erik run a family business called Murphy & Associates in Seattle. It’s an IT and business consulting staffing business that: (a) recruits top programmers and program managers; (b) identifies key projects at large tech companies; and (c) makes a match. The service allows large companies to rapidly staff up and down. Top talent can work part of the year for full-year pay without ever having to search for a job or worry about paperwork. The key to its success is how well Murphy & Associates evaluates talent. They go beyond the resume and interview and instead focus on key projects employees worked on, using their industry expertise and deep network to discern whether the projects were truly successful, and then they cross-check the impact of the person.

What if this model existed on a larger scale to help staff innovation and growth strategy initiatives for big business?

I previously wished for a Shark-Tank for Corporate America to create more efficient capital markets to fund great innovation ideas bogged down by bureaucracy. But capital isn’t the only problem facing big businesses that want to innovate. Many companies lack the right talent to take on important new projects that could help create the business’s next big category.

Just this year I’ve spoken to more than three CEOs who are excited about huge opportunities for category creation or big innovation, but each is stuck figuring out with how to staff it. Often they tell me that because their innovation is very similar to a previous successful business launch–the analog could range from a technology like Netflix to a consumer product innovation like the Swiffer–they’d love to hire a person who’d been a key player in those projects. I routinely hear comments like: “Who was on that team? Who did what? Finding those people would be awesome!”

In theory that should be easy to do. In practice it’s not, because success has many fathers. The teams that create breakthrough products are large. The projects last a long time, and team members come and go. By the time a product is a clear-cut success, vital team members have moved on. And if a product becomes a breakout hit, you can be sure that many people who were only peripherally involved will claim more than their fair share of success. I remember talking to someone who was a core member of the team that developed a $500 million breakthrough innovation. He recounted meeting numerous strangers who claimed they’d played a key part. He would sometimes respond: “I’m glad to meet you, because I didn’t realize you had such an important role on my project.”

Observing this problem, I’ve begun wondering: What if there was a talent exchange model that wasn’t people and skill centric, but rather project and role centric?

Said differently, I think the existing talent evaluation models should be reversed. Right now the model starts with people, then skills, then accomplishments. Validating the information is getting better (due to innovations such as LinkedIn’s endorsed skills), but most accomplishments are not vetted.

My colleague, Jody Kirchner, and I brainstormed the following: What if LinkedIn, search firms, and VCs flipped the flow. What if, instead of looking at resumes, they began by looking at recent successful products, then identified and validated who was on those teams, including their roles, responsibilities and personal results. Only at the end would you begin to focus on individual people.

The first step is to build a searchable database of the biggest innovations, successes and toughest problems in business. A good amount of this is available already via HBR, or key lists like Fortune 100’s top fastest growing companies or Nielsen’s Breakthrough Innovation Report. The key is to create searchable details around the situation, complication and resolution. What was the original context before the success? What were the biggest barriers? How did they solve for it? The more detail, the easier it will be for other companies to identify analogs for them to explore.

The second step is to identify the team that drove the results. I think this will be easy, as I’ve discovered that core members of a team have memories like elephants. They remember intricate details, key make or break moments, and especially who was involved and who really contributed (and who did not). The teams could be self-regulated…you can identify yourself as a member of the team, but a good part of the team needs to approve.

The third step is to highlight the specific roles and responsibilities each core member had. Who was the project manager? Who was the technical lead? Who sold the idea into key stakeholders? Did this person add or detract from team chemistry? And importantly, would this project have been as successful without this person?

Finally we need a step that identifies what our CEO, Steve Carlotti, and I like to say are the 3F’s needed to drive truly extraordinary growth—Facts, Faith and Fortitude. Finding the facts is the easy part. Having the faith to believe in something that doesn’t yet exist and the fortitude to persevere are two entirely different things. Finding a way to verify this, even if by qualitative endorsement by others on the team, is critical to finding the right people.

We believe the data to synthesize this exists – and existing social media networks can help us validate. The question is: who will get it done? If someone can accomplish this, many companies will benefit.

Executing on Innovation

Special Series

Recognize Intrapreneurs Before They Leave

The Right Innovation Mindset Can Take You from Idea to Impact

When You’re Innovating, Resist Looking for Solutions

Research: Middle Managers Have an Outsized Impact on Innovation

How Your Brand Can Beat Goliath

There was once a running joke at Virgin Mobile when it came to our marketing spend: What Virgin Mobile would spend in one year, AT&T would spend on one episode of “American Idol.”

Many disruptive brands struggle with how to best manage their marketing budgets while they strategize around how to dethrone their incumbent Goliaths. Smaller companies, of course, don’t have the advertising spends to compete with their competitors on traditional vehicles, and they’re far more susceptible to shifts in the competitive landscape. A simple budget cut can render them “dark” during peak months on TV, causing their consideration levels — a key metric for brand directors trying to compete — to dwindle. Marketing execs then end up “re-launching” their own brands to new audiences on a loop in a struggle to make up for lost time.

This is exhausting and, more importantly, it isn’t working.

If ever a David were to save his strength to fight Goliath, the first step would be to eliminate needless spending on changing campaigns for re-brands, and focus more time on changing the conversation. Literally.

Social conversation is the only way small brands can get an edge on the big guys.

True brand affinity — or brand “lust” as we like to call it at Virgin — breaks down into three key ingredients: Rational, cultural, and emotional. The Goliaths typically play in the rational space; this is the arena that appeals to the part of the brain looking for a good deal. The core campaign message is very specific and clear, and it’s usually about value. The problem is, when several competitors share the same rational message about value, the Goliath with the loudest voice (i.e., the highest media spend) wins.

For your brand to break through, you need to appeal on two more nuanced dimensions: cultural and emotional. You need to create and share a point of view that your prospects find enlightened and unique. And to express that point of view is to speak your mind freely — as a brand — not about what you have on sale, but about something bold that will stir a customer’s interest.

Cultural marketing starts by creating your own topical breaking news about trends your customers care about, making your brand hyper-obsessed about a specific niche or topic. When you tap into something that your audience can relate to, you’re tapping into something cultural. Lululemon, for example, talks about yoga. Nike talks about fitness. But sometimes the delineation isn’t always clear.

At Virgin Mobile, we tapped into something more abstract: the absurd phone etiquette that seemingly preoccupies us all. It wasn’t about showing a happy customer using Instagram; it was instead about the relatable folklore surrounding a woman who’d rather Instagram a pizza she was eating than respond to her jilted ex’s desperate texts.

This example taps into two cultural and relatable norms – our smartphone-obsessed society and a relationship gone bad. They require more thought and customization than typical marketing messages around the rational, but also result in an ownable voice that Goliath can’t touch.

Emotional marketing is even more nuanced. It requires tapping into, or reacting to, a larger, more shareable moment. And above all else, it requires a mastery of the element of surprise to create something emotional. If a cultural trend occurs, the response that creates an audience reaction is not to align with it, but to buck it. That, in turn, makes the moment emotional. And true emotion is what fuels something shareable.

During the wake of the recession in 2009, we at Virgin Mobile faced the awkward decision to potentially cancel our music festival (as others had done, fearing that fans couldn’t afford the ticket). At the time, swine flu and job layoffs headlined the nightly news. Our goal was to put forth a new energy that would focus on optimism. We embraced the cultural winds and declared our festival free of charge to the public. We created a VIP lounge whose admittance was only offered to those who had been laid off (and those guests were pampered accordingly).

“Pink Slip Pinatas” were hung from trees and for a brief moment, young fans could celebrate a day of free music instead of stressing about getting a job. Virgin Mobile FreeFest was born with an announcement that earned nearly 500 million earned impressions and to this day (literally to the day — the 5th annual FreeFest was just held two days ago), the festival raises hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for homeless youth, celebrating good karma and the right to pay it forward. Similarly, that same year, Hyundai offered it’s legendary offer to buy back cars from people who lost their jobs.

Owning a breakthrough moment. A social conversation. These are admittedly scrappy tactics and taken alone, don’t make a cogent, annual marketing strategy. To really master this art on the cheap, you have to create a platform that can leverage traditional vehicles that gain mass reach while complementing them with the “fairy dust” of social storytelling that adds folklore to your brand and forges true emotional connection to reach the consumer.

Another good way of thinking about it is via the lens of a political campaign, which typically involves two forms of marketing: traditional (e.g., TV ads, billboards) and seeded. For example, a political candidate may run an ad that says she favors gun control — a marketing message that speaks to rational. The campaign’s social storytelling, however, may spread images that remind us of recent shootings to create context around the marketing message. “Haven’t we had enough? Isn’t it time we elect someone who controls our guns?” The social conversation tees up the ad, which is designed to reach as many people as possible with a simple, memorable message.

Here’s the way that works at Virgin Mobile. We would run ads that spread our core message: “For $35 a month, you get unlimited messaging and data and only 300 voice minutes.” Our seeded message on social channels was simply the following: “You don’t need voice minutes. No one talks on the phone anymore. In fact the people you talk to on the phone are people you probably don’t want to talk to (e.g., the cable guy, airlines, etc.).” Both seeded and traditional worked hand in hand. And if budget cuts killed our TV media (and oftentimes, they did), our social conversation was alive and well.

Goliath will always have the luxury of being omni-present in the consumer’s field of vision. But Goliath is not nimble. And to truly win a crowd, you need to pivot to tell the right stories they want to hear at the right time.

Women Lose Out to Men on Competitive Exam After Doing Better on Noncompetitive Test

Women perform more poorly than men on the highly competitive entrance exam for French business school HEC Paris, even though the same women had performed significantly better, on average, than the same men on France’s pass/fail, less-competitive national baccalauréat exam two years before, says a team led by Evren Ors, a professor at the school. As a consequence, the pool of admitted candidates contains more men than women. Once women are admitted to HEC, they tend to outperform their male classmates. Tournament-like competitive contests may lead to gender differences in performance, the authors say.

September 20, 2013

The Curious Case of Summer’s Hottest Food Item: The Pretzel Roll

If you’re like me and watch far too much television, this summer’s pretzel roll ads felt like salty lasers incessantly burning their promotions into your hungry heart. No fewer than five large American restaurant chains peddled an offering encased in a pretzel-like bread.

To begin: There are two burgers; one at Ruby Tuesday (which involves a cheeky yet alarmingly named photo-sharing promotion called “Fun Between the Buns“):

And one at Wendy’s, which was touted by a spokesperson as ”among the top-performing burgers that Wendy’s has ever tested”:

Sonic offered a pretzel hot dog:

Dunkin’ Donuts fashioned a sandwich involving roast beef (but don’t worry, you can get any sandwich in a pretzel roll, too):

And now Honey Dew has decided a pretzel bun is the perfect edible jacket for eggs, cheese, mustard and chicken sausage, described by Boston.com as a “culinary collision of sorts.” Or as my friend wrote on Instagram, along with a photo of the commercial, “What the HELL?”

What the hell, indeed. As a snacking aficionado and retired conspiracy theorist (I read the entire Warren Commission report at 13) my sleuthing instincts have naturally gone into overdrive. Why so many pretzel rolls at so many chain restaurants? What’s the endgame? What does this all mean? After weeks of thought, excessive tweeting, and concern among friends, I narrowed down the possibilities to three:

The pretzel lobby and/or a clever consultant duped the country.

Everyone is playing copycat.

Pretzel rolls really are simply that delicious and I should just stop it with my righteous concern.

Indeed, pretzel rolls are pretty much engineered for maximum pleasure. Michael Moss, a New York Times reporter and author of the book Salt Sugar Fat talked me through some of the benefits of the bread. “Salt is one of the three most powerful ingredients,” says Moss, referring to the title of his book. “When it’s on the outside of the food, it’s the first thing that touches the saliva and hits the pleasure center of the brain.” The other attribute that helps the product out is its dual crunchy/soft texture. “The more different textures you can get into one bite,” explains Moss, “the more wowed the brain is.”

For the case of brevity, let’s say Theory 1 is off the table (this is seemingly no edible Watergate scandal). The answer to my all-consuming mystery, however, may just be a mixture of Theories 2 and 3. And it’s a window into the cyclical nature of how restaurant chains manage risk and give their customers “new products,” all the while maintaining (and sometimes boosting) profit.

It “screams gourmet” while evoking both Brahms and John Philip Sousa.

Before getting into why all the restaurants under the summer sun put pretzel items on their menus, it’s important to understand what pretzel bread stands for. I’m not kidding.

The history of the pretzel, of course, stretches through Germany and France. “It’s been around since 6 AD,” says Richard George, a professor of business administration and food marketing at Saint Joseph’s University. “If you were in Bavaria, you would get it everywhere.”

Nowadays in America, pretzel bread is a popular upscale pub food — and if you watched the above commercials, you would have noticed that both Wendy’s and Sonic pepper their ads with quality references that evoke an luxurious sentiment.

According to Bruce Horovitz at USA Today, that’s hardly accidental. Wendy’s pretzel burger, which was billed by the company as “the most anticipated new product in recent history,” closely followed the rise of hot pretzels “in the casual-dining sector and even in some fine dining restaurants” as well as in Europe, where pretzel rolls are common. And apparently what makes Wendy’s buns unique is that they are “artisan baked,” their tops “hand cut prior to baking giving each pretzel bun a unique appearance.” In other words, your burger is churned out in a way to make it seem like it isn’t.

Similarly, Sonic told Bloomberg Businessweek’s Vanessa Wong that their pretzel roll “screams gourmet, so the value score is very high with customers.”

This infusion of a European sensibility with words like “artisan” and “gourmet” is deliberate. Tim Ettus, the director of operations at Sparks & Honey, a data-driven advertising newsroom that helps synchronize brands with culture, points out that food indulgences, complexity, and hybrids are currently en vogue, what with the cronut and other European pastry-like items becoming popular. And the idea of “craft” is huge: “There’s a sex appeal and respect for things that are made with a great attention to detail.”

The pretzel roll isn’t just Euro-chic, however.

In a statement, a Sonic spokesperson also stressed that their product is based on a sacred piece of Americana: “We used a baseball theme to advertise our pretzel dogs, as nothing beats a hot dog and a pretzel at the ballpark. We just found a way to combine these two favorites.” Stan Frankenthaler, the executive chief and vice president of product innovation at Dunkin’ Donuts, echoed this sentiment in a statement. “Using [pretzel bread] as a carrier on a sandwich, or in other creative ways, is a nod to a nostalgic food memory that guests find appealing, not only for its taste, convenience and quality, but for the fun behind it.”

So if you’re following, the pretzel roll is an upscale food item that evokes European sensibility, American patriotism, hip pubs, nostalgia, and fun.

How did such items end up on multiple summer menus?

The restaurants I contacted said they couldn’t speak to the motives of why other companies came up with a pretzel-related item for their summer menus, but were happy to talk about how they go about new product development.

“When we create new menu items, the culinary team goes through a rigorous development process to be sure that we are serving the best-tasting product to our guests,” says Stan Frankenthaler, executive chief and vice president of product innovation at Dunkin’ Brands. In a statement, Sonic claims “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. We began testing the pretzel dog some time ago and we generated significant media attention around the launch of the product.” The company spokesperson continues: “I can’t answer for why others chose to copy what we are doing, but we are thrilled with the success we have had with pretzel dogs.”

Now, this information, combined with Wendy’s declaration of the “most anticipated new product in recent history,” doesn’t actually answer any questions about who came up with the idea first (though Sonic makes a good go of it). Without being privy to product development knowledge at all the restaurants involved (or being an actual investigative reporter), it seems pretty darned impossible to crown the Edison of fast food pretzel bread. But it may not even matter, because truly coming up with an innovative product may not be as important as copying someone else.

“If you ask a restaurant or chain why they imitate someone else, they’ll say ‘no,’ but it happens throughout history,” says Oded Shenkar, author of Copycats: How Smart Companies Use Imitation to Gain a Strategic Edge. “It may be McDonald’s imitating White Castle’s standardization of hamburger production, or the copying of the Nespresso capsule. And, of course, there’s the imitation of the actual product itself,” which has fueled, for example, the generic drug industry.

It’s easy to turn up your nose at the idea of imitation — it’s pretty much the opposite of the notion of innovation everyone’s so into — but Shenkar urges a different perspective: that a copy may be a smarter business move than creating something original. “For one, there are those who want to associate their product with the original, and offer a lower price or introduce it to a different market. Then you can tinker with it and claim something better.”

In addition, he told me “the imitator often gets a better return than the innovator.”

“At the end of the day, it’s not about being the pretzel pioneer,” he says, offering what might be the most sober bottom line to the trend. “It’s about who makes money out of it.”

What’s really important is that a company knows how to imitate really well — a skill many companies may or may not have (one can imagine Honey Dew’s breakfast sandwich falling into the latter category). None of the pretzel-loving companies I contacted would give me any financial information about their foodstuffs, only telling me that their products did well and were popular with customers. Of course, no decent PR person is going to say anything otherwise. But it’s possible that Pretzeltime Summer 2k13, which I had attributed to utter foolishness (or even some invisible sodium-speckled hand), may actually have been a pretty shrewd strategy. Besides, says Shenkar, “a business model or ingredients can’t really be copyrighted. There are very few things to defend.” And when something is clearly popular, be it in pubs or in other fast food restaurants, there’s very little risk in throwing together a similar item to see how it sticks.

“When somebody does seem to strike a gusher that’s attractive, it makes perfect sense that everyone would copy it,” adds Michael Moss. For his part, Richard George is surprised the pretzel bread trend didn’t happen sooner.

Did you solve the mystery of the pretzel roll?

It turns out there probably wasn’t an actual mystery in the first place (sorry to disappoint). “I don’t think it’s a big deal,” Richard George told me about the pretzel roll trend, and given his extensive experience with the food industry, he’s probably right.

What we’re seeing is a regular phenomenon that hinges on restaurants making relatively foolproof bets, with your mouth the unwitting target. Not only are companies copying other companies, they’re copying themselves. The success of Taco Bell’s Doritos Locos Taco, while a slightly more complex product and situation, isn’t lost on anyone.

“The food industry is astonishingly risk-averse,” Michael Moss says. “The majority of new food products fail, which is dangerous because it’s so expensive. What tends to happen is that you don’t see new products, but things that pretend to be new and are slightly different.” Just throw a burger in a different bun and voila!

In addition, Stan Frankenthaler, the executive chief and vice president of product innovation at Dunkin’ Brands, says that that his company has found “menu items that are ‘familiar with a twist’ tend to resonate well with our guests” (if you watched the Ruby Tuesday ad this might sound familiar). Dr. George sees this often. “The same old pastrami and rye gets boring,” he says. “The salty taste and the texture [of pretzel buns] make it a party in your mouth.”

But will all this rapid imitation succeed in the long run? According to the folks at Sparks & Honey, making a legitimate cultural breakthrough in food takes more than just a bun. “Food is social currency,” says Dan Gould. “You want people to talk and take pictures of it.” Tim Ettus agrees, pointing to social currency as “what’s determining success” in products across industries. He also says that the people driving huge food trends aren’t necessarily copying other restaurants — they’re looking to adjacent spaces like design and the art world to get ahead of the curve. “If you’re a QSR [Quick Service Restaurant] and want to get ahead of the others, you want to be looking there instead of in the food space.”

And you can be sure that fast food restaurants are already onto what’s next. “They’re always one step ahead,” says Richard George, but always careful to maintain a balance. ”We like new things, but we like equilibrium. We like tension, but not too much. We’re always throwing a party for our mouth.”

Stop Assuming Your Data Will Bring You Riches

“We have a treasure trove of data, it’s highly valuable”.

“If we can unlock the value of all our data, we will have a wholly new revenue stream”.

“Hedge Funds will love our data — they will practically buy any set of data that might give them a potential edge”.

These are just a sample of thoughts from clients in recent months who were excited about the prospect of creating new businesses and new sources of revenue in what seems to be a lucrative new area. Big Data. Analytics. Content Innovation.

In some cases, they’re right. But then again, in a surprising number of cases, they aren’t. The opportunity, which seemed immense on the outset, turned out to be disappointingly smaller after a thorough evaluation. Fortunately, the organizations that took the effort to truly understand the value of their data were able to execute appropriately. Very importantly, they were able to avoid costly technology and implementation programs that would have surely fell short of usage and revenue expectations.

Here are four steps your organization can take in order to understand the value of your data, and to plan for potential monetization:

Clarify whether it’s really your data

Sounds obvious, doesn’t it? Unfortunately, this may be the most common mistake that organizations make. They assume that if they collect the data, and house it in their systems, it must be their data. Or if they collect data and then add a proprietary methodology to it, that automatically qualifies it as proprietary data. Or if they create analytics from raw, underlying data, and subsequently barter the analytics, they must be able to charge hard dollars at a later stage. All of these assumptions may be true…but are more likely false. Unless you have written data contracts in place that clearly allocate ownership of data and derivative works, you may not be able to do anything with the data.

To evaluate data ownership, enlist the early help of domain experts — content specialists and legal counsel who understand how data is created, stored, manipulated, packaged, distributed, and commercialized.

Categorize the datasets you have identified into three buckets: “data we own”, “data customers own”, and “data third parties own” to ensure added clarity.

Quantify (as much as possible) the value-add of any derived data versus the original data, in order to be in a better position to create mutually agreeable data usage and revenue share agreements with suppliers and co-creators of the data.

Understand who would value it, why, and how much

This is easier said than done. In speaking with over a hundred end-users of data over the past year (in Financial Services, Healthcare, Technology and even Nonprofits), I have come to realize that your target customer may not be your traditional customer. For example, a product evaluating nonprofit organizations may be highly useful to a wealth manager seeking to help his client to select a charity as part of a value-added tax efficiency service. Or a healthcare data offering evaluating physicians’ perceptions on a new drug may be useful not only to brand managers at pharmaceutical companies, but also to portfolio managers at asset management firms seeking to find promising investment opportunities.

Identify target customers by casting a wide net across potential users, and performing customer interviews to establish their “jobs to be done” (as Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen says). Determine where their current data gaps are, and evaluate if your datasets can fill those gaps, either as raw data or in a more processed, analytical format.

Test user perceptions with a range of potential data offerings. End-users vary in their level of sophistication of data usage, and some may immediately see the value of the raw data, whereas others may want to be given visual examples of the value the data can bring. As one client once told me, “It’s as if I were at a farmers’ market with all the most amazing fruits and vegetables, and I can think of a hundred recipes that I would love to prepare.” It’s clear that he saw the potential of the raw data. Others may not wish to (or be able to) be the chef, and prefer to be the diner at the restaurant, where they have a menu of dishes that they would rather choose from. Both are eventual consumers of the raw materials, and both should be served!

Ask prospective customers to assign a gut-check ranking — ”High”, “Medium” and “Low” — to the individual datasets and metrics and note these preferences respectively in green, orange and yellow. End-users’ initial reactions are generally quite pragmatic and representative of their overall assessment of value, utility, and willingness-to-pay. As the customer interviews progress, the color-coded matrix will come to life, and can help prioritize where the opportunities truly lie.

Frame up realistic aspirations for monetization

At this point, many companies get to work and prepare detailed financial projections that show how many new sales they can achieve every year, what their proposed pricing is, what the year-on-year percentage increase will be. Sometimes that makes sense. And sometimes it backfires – what if the monetization potential is not really that big? How do you ensure that your execution is commensurate with the revenue opportunity?

Set yourself a target that is big enough for you to pursue and that you feel is worth your organization’s time and effort. The innovation consulting firm Innosight often refers to “$50 million in 5 years” as a reasonable target for a brand new business. For you, it may be different.

Ask yourself “What would it take to get to that target?” Data can be commercialized in a number of ways: via annual subscriptions, via once-off consulting and integration fees, via custom content development, via research and advisory services, and via new analytics development. Ask yourself how many of these are truly viable. Consider comparable offerings from competition and their pricing structure. In many cases, you may come to an epiphany that your target is just not reasonable.

Understand whether the data provides more value than just the new standalone revenue. You may come to the conclusion that your original $100 million target was unrealistic, but $10 million is achievable. Do you decide to stop? Well, it depends. Sometimes the revenue may be small in absolute terms, but the data capability may be complementary to your current, core business. The value may be in the combination of the two, which can drive significantly higher core business revenues.

Test, learn, and tweak

Now that you have a realistic revenue aspiration and have decided to continue pursuing this opportunity, you turn to execution mode. If you are sure about the opportunity in front of you and your ability to execute, this may work. However, if you are new to the data and analytics game, and are not sure whether you can be successful due to a multitude of ambiguities, you may need a different approach.

Highlight the areas in which you think you may fail, and create test programs to evaluate your ability to execute. Do you have the ability to provide real-time data 24×7? Will customers really pay what they alluded to in the interviews? Will your data distribution partner really be motivated to work with you, or will they have other priorities? These are all crucial parameters that will determine whether your data can really be commercialized. They need to be addressed, and solved before launching a business in earnest!

Create tangible success criteria that will allow you to either determine whether you can solve the problem, or whether you can learn something that will help you make a go/no-go decision. For example, a test could be “validate subscription business model via direct sales by securing three signed customer contracts within three months”, or “create dashboard of [specific number and type of] metrics which 100 end-users test, validate and give suggestions for improvement, within three months.”

Implement the test programs with defined roles and responsibilities for the Test Program Owner, as well as the execution team. Ideally, the team should be small, 100% dedicated to the pilots, and cherry picked for their domain knowledge in content, as well as their ability to work in an agile, entrepreneurial environment.

The results of the test programs can help get you to a more informed view on whether you go ahead with implementation, whether you stop, or whether you need to make some modifications to your business model and/or execution.

In following this overall process above, you can clarify what data you own, and how valuable it is (and to whom). You can frame up realistic aspirations for monetizing your data, and you can prove your right to succeed by testing (and overcoming) areas of potential failure. You can therefore move from an unsubstantiated assumption about the value of your data, to a more informed understanding of its worth in terms of its use to current and prospective customers, its standalone commercialization potential, and its potential to enhance your current business.

Stop Feeling Guilty About Napping at Work

"Is taking the high road truly a sustainable strategy, or does it merely delay the inevitable?" asks writer Sam Grobart of Apple, who interviews CEO Tim Cook, chief designer Jonathan Ive, and head of software Craig Federighi to gauge how the trio is thinking about innovation in a market that has Android licking its lips. But Cook and his team have no interest in a race to the bottom. "We've never had an objective to sell a low-cost phone," Cook says, emphasizing that they're "not in the junk business." And while there's ample competition from Android – the top operating system in the U.S. has been the Google-based system for three years – 55% of all mobile activity actually comes from iOS. "Does a unit of market share matter if it's not being used?" Cook asks.

But big questions remain. Will the company's phones make headway in China, where there's ample brand appeal but not as much personal cash flow? Are the expectations of Apple lovers backfiring on the company’s share price, now that breakthrough innovations have been sparser? And as rivals get better and better at strategizing like Apple, how should Apple's strategy change?

Window Dressing Ain't Cutting ItBabes Beyond Boards20-First Blog

While efforts to boost the numbers of women on corporate boards have been working, Avivah Wittenberg-Cox reminds us that there's much more to be done. "Welcoming a few non-executive women to your Board has little impact on what companies look like inside," she writes, arguing for progress on executive committees as well. Focusing on France and the U.S., Wittenberg-Cox takes note of the gaps between the percentage of women on boards and on executive committees (26% and 11%, respectively, in France; 22% and 18%, respectively, in the U.S.), and argues that waiting for a trickle-down effect is problematic. There's little proof that having more women on boards leads to more female executives, so waiting may be a massive waste of time. Considering women’s education levels and purchasing power, "can companies afford to window dress their Boards without actually harnessing the benefits of balance throughout their organizations?"

If You're Angry and You Know It…Most Influential Emotions on Social Networks RevealedMIT Technology Review

Do we share things out of joy, anger, sadness, or disgust? New research by Rui Fan and team at China's Beihang University finds that "anger is more influential than other emotions" when it comes to galvanizing online communities, "a finding that could have significant implications for our understanding of the way information spreads through social networks." Analyzing data from Weibo, the researchers found that people whose tweets fell into an "angry" category were more likely to pass the sentiment on, with joy coming in second. Emotions like sadness or disgust tend not to take root to the same extent. There are, of course lots of questions about whether these emotions translate to other languages and cultures. But when it comes to China, two types of events tend to provoke the most anger: foreign policy conflicts and social issues like "food security, government bribery, and the demolition of homes for resettlement."

The American Dream, IndeedImmigrants Lacking Papers Work Legally — as Their Own BossesLos Angeles Times

The battle over immigration reform in the U.S. is complicated (and that’s an understatement). But amidst employment crackdowns, differing state laws, and battles over visa rules, many undocumented workers are finding a way to work that's perfectly legal and benefits U.S. workers and the economy: They're starting their own LLCs. And while this type of legal work has been allowed since 1986, advances in technology, combined with a younger generation that largely grew up in the U.S., may be increasing the number of people who turn to being their own boss. While it's difficult to track this trend in a quantifiable way, one study found that "25,000 workers living in Arizona became self-employed in 2009," a 8% jump from the previous year.

Carla Chevarria, a 20-year-old Phoenix resident and owner of a successful graphic design company, can't even drive in the U.S., or work for other people. But she can hire people to work on national campaigns. The irony isn't lost on her: "They say we're taking money and jobs and don't pay taxes. In reality, it's the opposite. We pay taxes. We create jobs. I'm hiring people — U.S. citizens."

No Snoring, Though The Science Behind What Naps Do For Your Brain — And Why You Should Have One TodayFast Company

Naps! Who doesn't like naps? Maybe your boss, particularly if you snooze at your desk. While this nice roundup from Beth Belle Cooper doesn’t break any new ground, it's the perfect collection of research and insights that could very well convince your higher-ups, colleagues, and employees that a little shut-eye is good for productivity. Cooper examines the health benefits of napping, how a few z’s improve memory and learning, and why dozing off can help prevent burnout. For people like me who wake up extraordinarily cranky from naps, she offers some tips on how to find out what kind of nap suits you best. Consider it a gift from Cooper to us to you to your pillow.

Bonus BitsWell, That's Depressing

I Am An Object of Internet Ridicule, Ask Me Anything (The Awl)

Women Earn $11,500 Less Than Men Annually (The Guardian)

The World’s Leading Development Economists Can’t Agree on How to Tackle Inequality (Washington Post)

Recognize Intrapreneurs Before They Leave

Any CEO can tell you that finding ideas is not the always the problem. The real issue is selecting and spreading the best ideas, testing quickly, and executing flawlessly. An “innovation engine” is an organization’s capability to think and invest in long-term opportunities along with the competence to drive continuous innovations for top-line growth each year.

To build your innovation engine, your firm must excel at operationalizing ideas from your energized people who are willing to do everything they can to fight off internal resistance without creating chaos. This is your bench of corporate innovators: your intrapreneurs.

You already have natural intrapreneurs in your company. Some you know about, but most are hiding. These individuals are not always your top talent or the obvious rebels or mavericks. But they are unique and certainly the opposite of “organization men.” When you find them and support them correctly, and magic will occur.

Intrapreneurs can transform an organization more quickly and effectively than others because they are self‐motivated free thinkers, masters at navigating around bureaucratic and political inertia.

In a firm with 5,000 employees, we’ve found, there are at least 250 natural innovators; of these at least 25 are great intrapreneurs who can build the next business for your firm.

Failed Leadership

Many senior leaders, surprisingly, are actually afraid to promote out-of‐ the‐box thinking for fear of losing their best employees to success and then to competitors; this is a sure sign of failed leadership.

Tomas Chamorro‐Premuzic argues that 70% of successful entrepreneurs got their business idea while working for a previous employer. These talented individuals left because the environment did not have an intrapreneurial process to pitch their ideas–and their bosses were unbearable. We find that smart people leave companies to start their own ventures because their firms did not believe in intrapreneurship as a critical tool for growth.

Successful Intrapreneurs

Based on our work with corporations, we have discovered six patterns of successful intrapreneurs:

Pattern #1: Money Is Not the Measurement. The primary motivation for intrapreneurs is influence with freedom. They want to be rewarded fairly, but money is not the starting point for them. Reward and compensation are a scorecard of how well they are playing the game of intrapreneurship.

Pattern #2: Strategic Scanning. Intrapreneurs are constantly thinking about what is next, one step into the future. These passionate change agents are highly engaged, very clear, and visibly consistent in their work and interactions. They are not sitting around waiting for the world to change; they’re figuring out which part of the world is about to change, and they will arrive just in time to leverage their new insights. Learning is like oxygen to them.

Pattern #3: Greenhousing. Intrapreneurs tend to contemplate the seed of an idea for days and weeks between calls, meetings, and conversation. As they shine more light on it, the idea becomes clearer, but they don’t yet share it. They know that others may dismiss it without fully appreciating it — so they tend to ideas in their greenhouse, protecting them for a while from potential naysayers.

Pattern #4: Visual Thinking. Visual thinking is a combination of brainstorming, mind mapping, and design thinking. Only after an exciting insight do intrapreneurs seem able to formulate and visualize a series of solutions in their head—rarely do they formulate just one solution. They do not act impulsively on a solution immediately, keenly aware of the need to honor the discovery phase for the new solution, giving it time to develop and crystallize.

Pattern #5: Pivoting. Pivoting is making a significant, often courageous, shift from the current strategic direction. It sounds scary and unfathomable to most mature organizations, although it’s often what is needed to resuscitate a dying company.

For example, Steve Jobs pivoted Apple from being an education and hobby computer company to a consumer electronics company. Wipro of India pivoted from being a small vegetable oil manufacturer to a software outsourcing powerhouse. CEO Tony Hsieh of Zappos pivoted from selling only shoes to becoming an online customer experience company. (In 2009, Amazon bought Zappos for $1.2 billion.) Jeff Bezos pivoted Amazon from being the world’s largest online megamall that sold everybody else’s stuff to selling its own hardware—the Kindle line of readers. This strategy has paid off well—as of this writing, Amazon owns about 60% of the e-reader market share, and its market capitalization value is north of $100 billion.

Pattern #6: Authenticity and Integrity. The intrapreneurs we studied demonstrate the attributes of confidence and humility, not the maverick-like behavior often associated with successful corporate innovators. They all, however, exuded high self-awareness and sense of purpose.

You can begin a senior-level conversation about intrapreneurship by addressing the following important questions about building a bench of intrapreneurs:

What is your organization’s definition of a corporate intrapreneur?

How does one become a successful intrapreneur?

How can you find intrapreneurs within and outside your company?

What are methods and tactics to develop intrapreneurs and intrapreneurial teams? How can your organization implement them to nurture your intrapreneurs?

Successful companies with their own innovation engines understand how to find, develop, and retain intrapreneurs. In order to outcompete, they promote and nurture a small start‐up environment within a large organizational structure that embraces continuous experimentation to find the next big thing.

Executing on Innovation

Special Series

The Right Innovation Mindset Can Take You from Idea to Impact

When You’re Innovating, Resist Looking for Solutions

Research: Middle Managers Have an Outsized Impact on Innovation

What’s the Status of Your Relationship with Innovation?

Redefining the Patient Experience with Collaborative Care

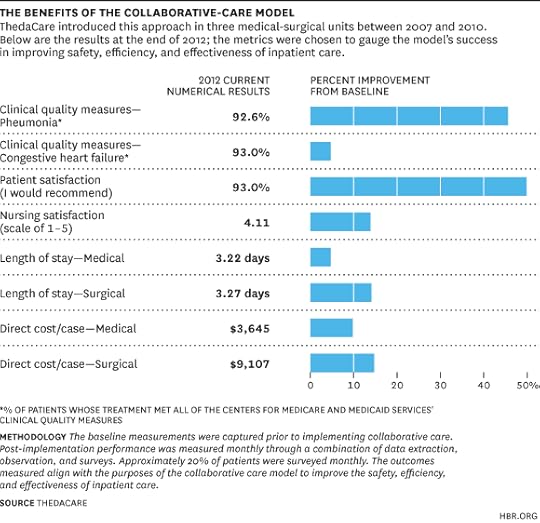

It’s a common patient complaint about the people involved in their care: “Sometimes the left hand doesn’t seem to know what the right hand is doing. I don’t feel everyone is working together.” To address this issue, nurses at ThedaCare employed lean techniques to create a patient-centered, team-based model that’s producing solid results.

Based in Appleton, Wisconsin, ThedaCare is a five-hospital health system with 26 clinics, other allied services, and more than 6,000 employees. It has been a pioneer in applying lean methodology in health care in order to tackle quality and cost issues. It began its lean journey in 2003 and has made considerable progress. For example, its accountable-care-organization partnership with Bellin Health, a health care system in Green Bay, Wisconsin, presently has the lowest cost per Medicare beneficiary among 32 pioneer ACOs, and the ThedaCare Physicians group was ranked first in quality performance statewide in 2013 by Consumer Reports.

ThedaCare opened its first “collaborative care” hospital unit in a medical-surgical unit at Appleton Medical Center in 2007 after 18 months of interdisciplinary planning led by nurses. A second was introduced in a medical-surgical unit at Theda Clark Hospital in Neenah in 2009, and a third in another medical-surgical unit at Appleton Medical Center in 2010. By 2013, all eight medical-surgical units in the two hospitals had been converted to the collaborative-care model.

The results to date show that the inpatient-care model is succeeding in improving safety, efficiency, and effectiveness. For the first three units, costs and length of stay declined, and quality and patient and nursing satisfaction improved. Some metrics improved immediately (within the first month); others over a period of six to nine months. A new process that required the pharmacist, rather than a nurse, to be responsible for “admission medication reconciliation” (a process that ensures that the patient’s list of medications that he or she is taking at home is accurate and can be used as a baseline for prescribing medication during his or her hospital stay) reduced the errors per patient admission to zero from between 1.25 and 1.5.

Team Care at the Bedside

The collaborative-care model replaces inconsistent, fragmented hospital care. A bedside-care team composed of a physician (“medical expert”), nurse (“care-progression manager”), pharmacist (“medication expert”), and discharge planner (“transitional-needs coordinator”) collaborates — with patient and family input — to develop a single care plan that is continuously updated in daily team huddles. On admission, the team gathers the patient history, performs a physical assessment, determines an anticipated discharge date, and works backward from this date to build a coordinated plan of care.

Using evidence-based guidelines linked to the electronic medical record, the nurse manages the patient’s care progression, and the bedside pharmacist contributes to optimizing management of the medication. The physician leads the clinical assessment and planning process but as a team member/partner. The discharge planner assists the team in devising the best transition plan post hospitalization.

This patient-centered approach minimizes duplication of effort, puts people in roles that leverage their skills and accelerates clinical learning as teammates teach each other. Staff use “tollgates” — purposeful timeouts that are a lean concept — to analyze the patient’s status and remove obstacles in delivering care.

Struggles — and Lessons — from the Journey

Despite the progress, the collaborative care model has had its challenges and remains a work in progress. For example, program designers learned belatedly that the new model requires a different kind of unit leader: a team-builder, coach, and mentor. A “collaborative-care spread team” consisting of clinical experts in the model, a project manager, organizational development specialists, and others guide the nurse managers through their unit’s preparation and implementation phases, supporting their leadership development every step of the way.

One challenge that’s currently being addressed is how to both maintain essential standard work across units and accommodate the requirements of clinical specialties. Some adaptation for certain patient types, like the short-stay surgical patients, has been needed to continue to meet the model goals. As with the original design, these adaptations were made using lean tools for ongoing process improvement.

Another ongoing challenge is getting private-practice physicians who use ThedaCare hospitals to fully engage. To help address this issue, hospital medical directors meet with independent physician groups to share essential elements of the model and determine how they can be applied to doctors’ workflows. (Garnering the full participation of ThedaCare-employed physicians has gone more smoothly.)

ThedaCare’s experience with collaborative care offers salient lessons:

Start from scratch. ThedaCare started by designing a new delivery process rather than adding to the existing process. Starting fresh sparks uninhibited creativity; it encourages “why can’t we” instead of “we can’t” thinking.

Follow a methodology. The design team fully used lean methods such as rapid-improvement events, value-stream maps, and visual-management concepts. That ThedaCare turned to hospital nurses to lead the program design reflects the lean tenet of asking people closest to the work to improve it. (For more information on how to apply lean techniques in health care, see this article.)

Fully use the talent. Collaborative care addresses one of health care’s greatest sources of waste and defects: the underutilization of skilled labor. Too often, highly trained staff work below their scope of expertise — for example, doctors doing what nurses not only can do but also probably do better. Nurses coordinating patients’ care progression and pharmacists managing medications represent big wins for patients and other stakeholders.

Involve the patient. The voice of the patient was a critical input in developing the collaborative-care approach. Patients participated in rapid-improvement events and were members of the development team. Patients anxious to know when they would likely go home were the impetus to providing a discharge goal on admission and focusing on the course of care needed to meet that goal. Patients voicing distrust because they were asked the same question multiple times by different clinicians during their admission laid the foundation for an admission process conducted jointly by the care team.

Invest in intentional thinking. Another lean tenet is assessment before action. Two examples: the 18 months that ThedaCare spent planning the new model and the care team huddles before, during, and after patient visits to assess and reassess the patient’s care plan.

Support strategy with infrastructure. Changes in the hospital facility were made to implement the new approach. They included converting semi-private patient rooms to private rooms and replacing the traditional nursing stations with decentralized alcoves located just outside of the patient rooms, where teams can huddle before and after visiting patients. A whiteboard was put in the patient’s room so staff could summarize the care plan, timeline, and other relevant information for patients and families. And the supply server was redesigned so it could be restocked outside patient rooms but would be easy for care providers to access medications (kept in locked compartments) and other things. This reduces the time that it takes for nurses to gather supplies, allowing them to spend more time with patients.

Communicate quality. In general, patients have basic expectations about their hospital experience — they want reassurance that providers care about them, communicate with one another, and are competent. Involving the patient in care planning, summarizing the plan on the in-room whiteboard, and following work standards that provide reliable outcomes communicate to patients that they are receiving quality care.

The progress to date of ThedaCare’s collaborative care model is evidence that patient-centered teamwork can improve the quality and lower the cost of care.

Follow the Leading Health Care Innovation insight center on Twitter @HBRhealth. E-mail us at healtheditors@hbr.org, and sign up to receive updates here.

Leading Health Care Innovation

From the Editors of Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine

Leading Health Care Innovation: Editor’s Welcome

Why Health Care Is Stuck — And How to Fix It

Getting Real About Health Care Value

Understanding the Drivers of Patient Experience

A Better Way to Encourage Price Shopping for Health Care

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers

![traditionalvscollaborative[2]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1418063128i/12655004._SX540_.gif)