Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1360

September 26, 2014

Find the Best Local Markets to Drive Growth

As families settle back into school, parents start to worry about the viruses that naturally spread when children cluster together in classes. My colleague Tim Joyce and I have found a similar viral phenomenon with superconsumers — our term for people who buy big volumes of a product or service, but who often can be convinced to buy even more.

But instead of spreading germs, superconsumers spread growth.

Tim and I observed this while using big data to better understand the habits of superconsumers. First, we found that they tended to cluster together at a local geographic level. In our work with clients, we call these local areas “super geos.” Second, we found that these super geos had a network effect — in these areas, even people who don’t qualify as superconsumers tend to spend more on the product in question. Finally, we found that these super geos made it easier for companies to develop growth strategies. These super geos were local profit pools that were concentrated and big enough to offer big ROI upside for marketing and sales.

Per capita sales of a category can vary wildly across different parts of the country. We wondered if this was a random phenomenon. So we built several models regressing hundreds of macro-economic, category, consumer, and competitive variables to figure out what was driving higher per capita spending. Having a wide variety of variables was critical to get a complete picture.

Sometimes it’s not immediately obvious why some geographic markets are such big consumers of a particular product. For instance, the best markets for top-sliced bread (think hot dog buns) tend to have had three to four times the profit dollars versus the average local market. What makes them unique? It turns out that these super geos tended to be in areas with high concentrations of elementary schools (which serve lots of bun-oriented lunches), warmer climates (more year-round bun usage at cookouts), and a strong lead grocer (which gives the bun-maker more willingness to invest to gain more shelf space). While we don’t know if super geos make superconsumers or vice-versa, we do know that in each instance it is not random. Certain local markets have the right ingredients to ripen demand.

Second, we found that within and adjacent to these super geos, non-supers spent more on the category than the average non-super nationally. This network effect reflects the power of “word of mouth,” which McKinsey says is the primary factor for 20-50% of all purchase decisions. Given that superconsumers are the most insightful and articulate consumers of a specific category, it is no surprise their influence is felt by regular consumers nearby.

In one entertainment category, for instance, non-supers who lived near superconsumers spent 20% more than the average non-super. This is like peer pressure with children. If you give one child a treat, the other children want one, too. This also works broadly in other areas like private label brands. In some cities (such as Las Vegas), $1 out of every $3 spent at the grocery store go to private labels; in other cities (such as New York), the ration is one-in-eight. If you see enough friends using store brand products, you’re more likely to consider it and buy it yourself.

Finally, when we analyze the economics of these super geos we find that these are attractive local profit pools waiting for companies to get after. In some cases, the top 10 super geos have accounted for 50-60% of the incremental profit pool for companies. This can meaningfully change the ROI equation for how a company goes to market. National marketing may make sense for efficiency sake when only one-in-ten consumers is a superconsumer. But if superconsumers account for one-in-four customers ina particular market, shifting from TV to digital marketing may make sense, because digital can very precisely find and reach superconsumers.

Some companies we talk to are beginning to question the core assumptions of their growth strategy. Ideas like economies of scale (manufacturing, sales, and marketing) are still relevant, but may have diminishing returns. National plans/strategies have long been efficient, but their effectiveness is in question as the US, in particular, is increasingly diverse in demand. Most European, Asian, and Latin American executives would laugh at the idea of a “continental” growth strategy. One wouldn’t assume the demands of Belgians, Luxembourgers, and Dutch are the same because they are part of Benelux, right? Yet, the vast majority of growth strategies we encounter fundamentally assume all Americans are more or less the same irrespective of where they live. “National average” may be two of the most misleading words in business.

Precision business models and one-to-one marketing may still feel out of reach for some. But perhaps the compromise between mass marketing and CRM is “GRM” — geographic relationship marketing. Super geos seem to show that the decision between a mass marketing/scale driven business model or a precision/niche business model is a false choice. And the best of both worlds is possible.

Women Negotiate Better for Themselves If They’re Told It’s OK to Do So

In an experiment, few women who applied for administrative-assistant jobs entered into negotiations about their wages, and of those who did, more negotiated them downward than upward, say Andreas Leibbrandt of Monash University in Australia and John A. List of the University of Chicago. For example, a typical comment from a female applicant was that the posted wage of $17.60 per hour “exceeds my expectations. I am willing to work for a minimum of $12.” But if the applicants were explicitly told that the wages were “negotiable,” more women negotiated them upward than downward, by a ratio of more than 3 to 1.

Read Fiction with Your Coworkers

I have to confess that I have never entirely understood the concept of “summer reading” for adults. In the Northern Hemisphere (especially the northern part of the Northern Hemisphere, where I live) the three months of summer offer a rare chance to be outside in weather that is actually enjoyable. Kids are out of school, colleagues are out of the office, and, if you’re lucky, weekends are out of a suitcase by some sort of body of water. Who has time to read?

But in fall and winter, the longer nights are perfect for curling up with a book. So when I recently heard about a new nonprofit, Books@Work, dedicated to bringing pleasure reading to the workplace, it seemed like the ideal opportunity to dig a bit deeper. I spoke with Ann Kowal Smith, Executive Director of Books@Work, about how reading groups can make a difference at the office. What follows is an edited version of our conversation.

HBR: You describe Books@Work not as a book club, but as a “voluntary seminar.” What’s the distinction?

In a book club, people come together in a very informal way. Our programs are led by a professor, and the professor brings a degree of expertise about a text that he or she is very passionate about. At the same time, the goal of the program is not to focus on the text alone, but to use the text as a window to exploring ideas. I often think of it as a hybrid between a college seminar and a book club.

Who participates?

A large part of our target audience is the 60% of the American adult population who hasn’t had the chance to go to college. It gives the folks who don’t usually get company-sponsored professional development a chance to have a turn. At the same time, we have found that cross-functional and cross-hierarchical programs – where participants from the shop floor are sitting next to the division president – can play an important social role in the organization.

Have you seen any impact on the organization itself, or is this mostly just a fun “perk”?

Sharing these books is a way to get to know each other better. We’re also talking to supervisors and asking, “Are employees more engaged, working better as a team, more innovative? Has there been a difference in retention?” While it is early days, we have seen quite a few cases already of supervisors telling us that they’ve seen people more willing to speak up, to share an idea, to disagree – it’s a lot more comfortable to practice in the seminar and then in the workplace, especially if it’s very hierarchical.

What are some of the books that you have seen spark the best discussions?

It varies group by group – there’s not one magic book. But we are adamant about using never using a business book or a self-help book or a “how to” book. Some of the books that have been the best well-received are the ones you wouldn’t think would be interesting in the workplace. The conversations are so much richer.

In one company, a professor led a discussion of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence and the group started talking about the similarities between what was happening in [Gilded Age New York] and what we see in society today.

Another example is David Guterson’s Snow Falling on Cedars, where one of the big themes is the strong “us and them” feeling in the community after WWII. Although this had nothing to do with the workplace of the readers, they had recently gone through a merger and got to talking about the struggle to become one community.

The very first book we did was with a group of female cafeteria workers. They read Germinal by Emile Zola. It’s a hard book. It’s about the working conditions of a mine in the 19th century. Zola really gets at the question, “Why do some people have higher standards of living?” and other core class issues. What the professor told me was that the participants loved it, and she did, too – she got a very different perspective from the one she hears in her college classes with undergrads. She said she’ll never teach the book the same way again.

Are there books that have just fallen flat?

There are some that are just too arcane. They become a bit challenging. One group struggled with Gulliver’s Travels. Another read Annie Proulx’s Close Range: Wyoming Stories, which is the short story collection that includes “Brokeback Mountain.” “Brokeback” is actually one of the more uplifting stories in the book — it’s a dark book. So while the book spoke to everyone, everyone said reading it was a slog. Even a book that frustrates people still gives them something to reflect on.

I think I know what you mean. I recently read The Orphan Master’s Son, which is this really compelling story about North Korea, and it was a great book but a hard read, emotionally.

Exactly.

I can’t help but think to some people, this might seem like an imposition on their personal time – a further incursion of work into personal life. Do you ever have any negative reactions from employees to this project?

We’ve never had a situation when someone was so forced into doing it that it heavily impinged on their personal time. Everyone has the option to say, “This isn’t for me.” Our offer is not, “this would be good for you, so you should do it.” It’s more, “We think you might enjoy this, and we’d love to provide it for you as an extra.” Generally the discussions happen at least partly on company time, so they’re not using personal time except to read the book.

If someone wants to “try this at home,” so to speak, what’s the key to guiding an effective discussion in a work context?

Pick a book that has broad human themes that are not necessarily related to a particular workplace, but let the reader stand in someone else’s shoes. The closer you get to the workplace, the more instrumental it feels and the harder it is to get people excited and engaged. When the book is totally unrelated, it’s amazing how many links the readers find back to [their work]. The facilitator should let people find the connections themselves not tell them what they should be discussing.

September 25, 2014

How Google Manages Talent

Eric Schmidt, executive chairman, and Jonathan Rosenberg, former SVP of products, explain how the company manages their smart, creative team.

September 24, 2014

Two Forces Moving Business Closer to Climate Action

This week, CEOs and world leaders met at the UN to talk climate. In the run-up to these high-level talks, many companies and some relatively new voices from the business community have been sounding both the alarm and the rallying cry for action. At the same time, the cost of renewable energy has dropped very far, very fast. It’s a perfect storm bringing us to two important tipping points: one of belief and commitment to action, and one of economics.

But there’s still a major disconnect happening in one other area: the relationship between business and citizen consumers.

First, though, a few of the highlights from the business community:

In June, former U.S. Treasury Secretaries Paulson and Rubin joined New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg in issuing the Risky Business Report, a pithy, hard-hitting look at how much climate change is “already costing local economies” billions and the hundreds of billions of assets and property at risk in the coming years.

In July, General Mills — nobody’s idea of a radical company — expanded the pro-climate lobbying group BICEP beyond the usual suspects (Nike, Starbucks, Ben & Jerry’s) to add a distinctly mainstream voice to the call for policies like a price on carbon. Kellogg’s officially joined the group yesterday as well.

Last week, “The Better Growth, Better Climate” report from the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate exploded the myth that we have to choose between building a prosperous, expanding economy and doing it in a way that protects our shared home and resource base (also called the planet).

This week, an important coalition of coalitions, We Mean Business, launched with its own report and commitment by large organizations to recognize the reality of climate science and the ability to act on it. One exciting offshoot of We Mean Business, called RE100 launched as well, with Swiss Re, Mars, IKEA, and others making the bold commitment to use 100% renewable energy. (Disclosure: I’m on the steering committee of RE100 this group working to bring in corporate members.)

This week, the World Bank, representing a group of 73 countries and 1,000 businesses — including many of the world’s largest — issued their own commitment to pricing carbon.

The cherry on top of the sundae this week was the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation — a $900 million pool of money that originally came from oil fortunes — announcing it would divest itself from fossil fuel companies.

This is all representative of the first tipping point: The large-scale commitment and belief in climate action in the private sector. If it’s not clear by now, this is no longer a fringe movement in business. The CEO leaders of the parade, like Richard Branson and Unilever’s Paul Polman, took the stage at The Climate Group’s climate week launch event in New York on Monday. Polman implored the world’s governments to stop heeding those companies, presumably the fossil fuel giants, with enormous political influence: “Don’t just listen to the few voices getting disproportionate air time, but to the majority of business now — they’re asking for a price on carbon, and more support for cleaner technologies and efficiencies.”

Polman and Branson are expected at these meetings now, but more leaders are joining. Apple’s Tim Cook spoke as well, saying “the time for inaction has passed,” and commenting that we don’t need to accept any “tradeoff between economy and environment — both are doable if you innovate and set the bar high enough.”

As it turns out, that bar doesn’t have to be so high after all. What’s really compelling about the new reports is the data on how cheap it’s becoming to slash carbon.

This is the second tipping point that will really drive action: The economics behind a clean economy shift are very strong. The We Mean Business report cites an internal rate of return of 81% (that’s a ridiculous payback) on energy efficiency in the U.S., and an IRR of 27% for those companies with the most aggressive, science-based goals and actions on climate. Even the most “expensive” options like renewables are becoming cheap so fast that it’s making CFOs’ heads spin. Even those hippies over at asset manager Lazard calculate that the cost of solar PV technologies has dropped nearly 80% in five years. Assuming that we’ll lose money by radically cutting carbon has become a radically outdated idea.

So business is moving closer to going all in on this clean economy thing, making what I call the Big Pivot toward a new way of doing business. A couple notes of caution though before we break out the bubbly, though. Two other pillars of society — government and citizens — need to make headway as well. Government doesn’t have a great track record of global negotiations on climate policy, but local and regional action is more robust, with 46 carbon markets globally covering a small but respectable 12% of emissions.

We citizen consumers need to step up, too. I brought my family to the amazing climate march on Sunday in New York. Hundreds of thousands of people made their voices heard. But there was a large dose of anti-corporate, anti-capitalist messaging in the crowd. I get it — business does some nasty things and the obsession with short-term profit maximization above all other definitions of business value is a pathology that’s dangerous for society and for business. But it’s not helpful to cast all companies into the same lot.

Companies in the clean economy world, a large and growing industry worth trillions, want action on climate and carbon, and they want it badly. But so do other mainstream companies. I marched in the business section (if you could call it that) on Sunday. Executives and employees from Unilever and Seventh Generation were there, but so was David Crane, the CEO of utility NRG, which currently uses coal for the majority of its energy. Crane is another one of those CEO voices making real noise – he’s “mad as hell” and wants a clean energy revolution. Crane’s treatise first asks all of us to think about our energy and put up solar panels. He’s smart to ask for consumer action and policy changes — both will make it much easier for NRG and other energy companies to chart a new, cleaner path forward.

It’s easy to march against the current system, but harder to commit to something to march for. Bringing the voice of the people and business in line is another tipping point we need to foment. Business can’t thrive unless the planet and society are thriving as well. But the reverse is true also — we can’t build a prosperous future without the resources and innovation that business provides.

The tipping points the business community is hitting are critical, but we need a society-wide movement, working together without creating unhelpful divisions. The climate isn’t a citizen issue or business issue — it’s an everyone issue.

Why We Hide Some of Our Best Work

Your employer can track your every move, no matter where you sit in the organization. Often, the impulse is to scrutinize all behavior — through real-time performance data, for instance, and open workspaces — so that nothing unproductive or unethical can lurk in the shadows.

But that much transparency can have a dampening effect on performance. Creativity and productivity suffer because the desire for control is so great. And that’s not an acceptable tradeoff, even in an age of reputation management, because this also happens to be an age of innovation and complex problem solving.

You can see these consequences in the results of a behavioral study at LEGO: Parents staged their kids’ childhoods with such a heavy hand — subjects’ bedrooms were “meticulously designed” and “suspiciously tidy” — that they left little space out in the open for truly creative play. The kids responded to living in such a highly controlled environment, with close parental surveillance, by stashing their favorite toys out of view. One boy hid a shoebox filled with “magic poisonous mushrooms” under his bed. Bottom line: The kids wanted privacy so they could play more freely and inventively — and to get it, they resorted to hiding the things they really cared about.

Workers similarly conceal their most creative thinking and problem solving from management when they feel scrutinized, because they fear retribution for not following carefully prescribed norms. It’s easier that way. They appear to be falling in line, doing what’s expected, so they’re left alone. Unfortunately, this also means they’re not sharing the improvements they’ve created and the lessons they’ve learned. It’s one of transparency’s biggest traps (for more detail, see my recent article in HBR). Managers think they’re seeing more in an utterly transparent environment, but they actually end up seeing less.

In a world where anything visible is likely to be assessed or evaluated, people respond as you would expect them to: They keep the most important things under wraps in an effort to manipulate what others think of them. The incentives run counter to authenticity, productive deviance, and simply getting work done efficiently.

Consider what’s happened in health care reform, particularly in recent reforms to how hospitals conduct rounds. Patients and family members are now being included in rounding discussions, which means some of the conversations that doctors and other care providers used to have amongst themselves have become taboo. While Socratic method may have previously been the norm for teaching residents, getting something wrong in front of the patient and family would result in a loss of credibility. And having the patient witness real-time problem-solving in a complex diagnosis may cause more anxiety than relief.

What’s the solution? Finding the sweet spot between transparency and privacy. HBS researcher Bethany Gerstein and I observed a smart approach at the liver transplant ward at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center: Do the problem solving and teaching in a private space, before conducting rounds. That frees caregivers to make their rounds more transparent and family-centered, because the messy work of discovery has already happened backstage.

As one senior member of the rounds explained, “We actually do the pre-rounds to get everyone on the same page.” It helps the team “come up with a solidified message so that when we talk in rounds in front of the family, the plan is clear.”

All this jibes with what my colleagues and I have observed in other organizations. When people can solve problems without a spotlight shining on them, they become less defensive and, as a result, more creative and productive.

You may find that to be true in your own work. What’s more, your employer doesn’t have to sacrifice the benefits of transparency to ward off its ill effects. Chances are, you’ll end up sharing more of what you learn if you aren’t afraid it will be used against you in a performance review or somehow put your reputation at risk (as in the hospital rounds example). After all, the LEGO study subjects were all too happy to share their secret toys and ideas with the researchers — because there was no penalty for doing so.

We Don’t Have to Ditch Capitalism to Fight Climate Change

The risk of climate change is real, immediate, and very serious. If the vast majority of the doctors I consulted told me that consuming copious amounts of butter significantly increased my risk of a heart attack, I would take out a little “insurance” and cut back on my butter consumption. It is of course possible that the 95%+ of scientists who have explored the topic and the National Scientific Academies of every major nation are mistaken, and that the uncontrolled emissions of greenhouse gases pose no risk of destabilizing the climate. Personally, I hope so. But I don’t think it makes any sense to gamble that this is the case.

Our world and our economy need to face the risks of uncontrolled climate change — the sooner the better.

Yet, the publication of Naomi Klein’s new book This Changes Everything earlier this month and the claim by many of the marchers at this Saturday’s climate march that “Capitalism is the enemy” raises another risk: that in our struggle to address climate change we will turn on the wrong enemy. I’m in complete agreement with Ms. Klein that as a society we should be doing something about climate change, and doing it at scale. But the first step isn’t to dismantle capitalism.

In fact, we know how to address the problem of climate change, and it doesn’t require ditching the market economy. Instead, it relies on harnessing it. We need to stop acting as though dumping heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere is costless and set a price on carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions. We need to stop subsidizing fossil fuels; the world is currently spending about $500bn to subsidize oil, gas and coal. (That’s not much less than some current estimates of what it would cost us to build a carbon free economy.) And we need to subsidize research into new energy technologies so that entrepreneurs can one day bring them to market. We’re currently spending less than $2 billion a year on clean energy research – that’s less than 5% of what we’re spending on health related research, and less than 2% of what we’re spending on defense orientated work.

Nothing in human history has approached the power and flexibility of competitive markets to create economic prosperity, trigger innovation, and support political and individual freedom. Real capitalism – a capitalism in which inputs are properly priced, where information is widely shared, and where there are no favors for the few — is one of humanity’s greatest inventions. But when it comes to carbon we’re not looking at real capitalism or truly efficient markets. If we were, we would see an explosion of innovation that would expedite the transition away from fossil fuels. We’re already seeing corporations all over the world invest in carbon-free energy, in efficiency, and in business models that limit environmental impact. With the right kind of policy reform this trickle has the potential to become a flood.

Both the marchers and Ms. Klein have a point, of course – namely that even though we know what to do, we’re not doing it. She thinks it’s because we’re the victims of evil capitalists. It is certainly true that political action on climate change would benefit from reforms aimed at limiting the influence of incumbent industries. We need to make it clear that our commitment is to a capitalism in which it’s not ok for corporations – or wealthy individuals – to use their money to bend the rules of the game in their own favor.

But there is more to it than that. Climate change is particularly hard to tackle because we’re not very good at trading off current pleasure to reduce future pain. We’re a species that smokes, fails to go to the gym, and takes on credit card debt. In the same way, we’d prefer to believe that climate change isn’t happening and that if it is we can delay dealing with it.

Our failure to address climate change is thus ultimately a failure of democracy. We need to build a social movement that can insist that our leaders put in place the policies that will enable us to deal with the threat of climate change. And while we may struggle with longer-term priorities, we’re also a species that will do almost anything to ensure the welfare of our children. We need to rediscover the old idea that responsive, democratically controlled government has a central role to play in ensuring that the rules of the game are fair, and in dealing with problems like climate change: tough, long-term collective action problems that can only be addressed by the state.

But that doesn’t mean that we should abandon capitalism. With the right policies, capitalism properly understood is perfectly well equipped to prepare us to face the risk of large scale climate change. In fact, it’s the only thing that can.

How to Prioritize Your Innovation Budget

Here’s the scene: A problem has come up with one of your supply chain vendors, threatening to delay timely shipment of your product. At the same time, a potential opportunity appears that, with some exploration and investment, could lead to a new generation of products down the road. Which do you respond to first?

You probably reach for your firefighter’s hat to extinguish the short-term problem. And therein lies a bigger problem. Leaders and organizations are under more stress than ever to do two things simultaneously: deliver on today’s pressing commitments by troubleshooting and refining processes; and find and invest in innovation opportunities that will create tomorrow’s success. How your organization responds to this stress in allocating scarce resources is a crucial but often unaddressed issue. The natural bias is to respond immediately to what is in front of you (like answering endless emails as they come in, for instance). The problem is, this instinct crowds out longer term, innovative thinking.

We’ve talked to many organizations in this bind. One of them told us, “We’re playing non-stop ‘Whac-A-Mole’ here.” At another, the unfortunate mantra was, “The urgent drives out the important.” But we’ve found that many leading organizations are able to overcome this bias, diverting significant resources away from today’s requirements to fund the innovations that will deliver tomorrow’s value. To find out how they do this, we focused on the two key questions underlying the challenge: How much is your organization spending on innovation? And how much do you think it should be spending?

This seems basic, but often people just don’t know the precise answer or haven’t thought in these simple terms. When we recently put these questions to a CEO, he said he guessed his organization was currently allocating 5% of their spending to innovation (new products and services), but added that they really should be investing 10-15%. He went on to say that the insatiable demands of today’s operational turbulence were robbing him and his organization of ability to invest in the future.

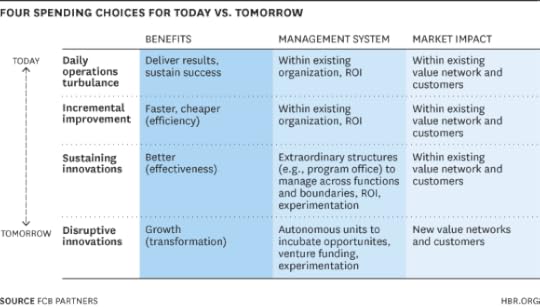

We reflected on this, and on the broader context we’ve seen in our work, and created four high-level buckets into which resources and money can be poured:

Daily Operations. This is purely about executing within an existing and stable operating model.

Incremental Improvement. This includes most of the myriad Lean and Six Sigma continuous improvement projects that drive improved efficiency and effectiveness within an existing management and organizational structure.

Sustaining Innovation. Here, a breakthrough change is achieved by modifying the operating model or crossing internal boundaries. It requires an extraordinary management structure such as a program office, value stream manager, or process owner to drive this type of investment, but it uses the current value network to reach current customers.

Disruptive Innovation. This significant breakthrough in the organization’s operating model and value network facilitates the achievement of growth in a new market, disrupting the entrenched players. This usually requires incubation and protection of a new venture in an autonomous unit.

Looked at this way, spending creates distinct impacts and benefits that can be balanced and adjusted across the today/tomorrow spectrum.

We asked managers from a variety of industries at a recent conference (and in an online survey) the same question, but asked them to specify how they were allocating resources between these four categories. Here, on average, is what they estimated they were currently spending:

85% of their resources on day-to-day operations

5% on incremental improvements that produced faster, cheaper, better sameness

5% on small sustaining innovations

5% on big, disruptive innovations

When we asked the managers what a better proportion might be, their answers were:

75% on day-to-day operations

5% on incremental improvements

10% on sustaining innovations

10% on big, disruptive innovations.

What our rough diagnostic confirms – not so surprising, perhaps – is that the battle between today and tomorrow rages on, and that tomorrow is losing. But the exercise also reveals that organizations instinctively feel they should be spending more on innovation. Easier said than done – but it can be done, and done well. Any organization attempting to shift the weight of its spending toward investments in creating future value must do three things:

Segregate funds for improvement and innovation. You need to measure spending across the four categories, and then be disciplined about segregating funds for improvement and innovation. In the absence of this clear segregation, the turbulence of day-to-day operations will devour the lion’s share of resources. Go ahead and do the math on your current allocation; you’ll likely find that more than 90% of your resources are devoted to keeping the lights on. Many leading IT organizations have recognized this problem and manage their budgets in three buckets: operations, maintenance, and innovation. They aggressively attempt to drive down the portion of their spending on operations and maintenance from 90% to 60%.

Tame the turbulence. This means identifying the root causes of the day-to-day operational turbulence and addressing them in a systematic, sustainable manner. The rules for smoothing the turbulence of day-to-day operations are few but powerful:

Do less. Much less. Initiate fewer projects. Track fewer measures. Get better at ending “zombie” projects, those efforts that have failed but no one wants to declare dead. At Sloan Valve, CIO Tom Coleman told us that they only launch a few major programs each year because that allows them to staff and integrate these initiatives with much higher quality.

Allow the important to triumph over the urgent. Prioritize resources carefully. Create clear policies about who can launch new projects and rigorously hold sponsors accountable for outcomes. Too often, organizations behave as if resources are free and capacity is infinite. Neither is true.

Take time before you reach for that fireman’s helmet. More time spent early on to find the root cause of a problem can save money in symptom management later. One leader explained this approach as “slow trigger, fast bullet.” Why is your vendor always having problems that become yours? Maybe you need a new vendor.

Create new organizations and controls for innovation. You need to develop organizational structures and controls that are appropriate for both sustaining and disruptive innovations. Today’s operations and incremental improvements can be managed within the traditional management structure, a command-and-control hierarchy, but tomorrow’s sustaining innovations and big, disruptive innovations need new organizational structures and controls. It’s too easy for revenue-producing parts of the business to poach resources from innovation projects and teams that are not (yet) contributing to the top line. They need to be protected – made autonomous, with their own dedicated budgets, resources, and leadership – until they are. And innovations need measures and controls which reflect their experimental approach to learning as they chart new territory with unpredictable outcomes. Performance should be measured by market momentum (such as new targeted customers or partners, deal size, and PR buzz).

In the battle between today and tomorrow, today will win every time unless the organization consciously, strategically decides to extend a helping hand to tomorrow. The first step is to measure spending against the four choices above. Do you like what you see? Are you willing to do something about it if you don’t? Remember, you’re making a crucial choice about your company’s future.

4 Ways to Retain Gen Xers

The economy’s slow but steady improvement should be good news. But employers may find a cloud lurking behind the sunny forecast: They are at risk of losing some of their most valuable talent — and they may not even realize it.

These aren’t the usual suspects. Instead of the 50-something Baby Boomers and the Millennials in their late 20s and early 30s, I’m talking about Generation X, demography’s long-neglected “middle child.” Numbering just 46 million in the United States, Gen X is small compared to the 78 million Boomers and 70 million Millennials. Yet proportionate to their size, Generation X may be the cohort with the most clout.

Now in their late 30s and 40s, Xers make up the bench strength for management. They are the skill bearers and knowledge experts corporations will rely on to gain competitive advantage in the coming decades. Approaching or already in the prime of their lives and careers, they are prepared and poised for leadership.

Yet their career progress has been blocked by Boomers who are postponing retirement and threatened by impatient Millennials eager to leapfrog them. They’re frustrated – and, having played it safe during the years of economic uncertainty, are now facing what may be their last chance to grab for the golden ring.

A 2011 survey from the Center for Talent Innovation (CTI) showed that 37% of Gen Xers have “one foot out the door” and were looking to leave their current employers within three years. Ding, ding, ding. The clock is ticking. The U.S. Labor Department’s August Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, popularly known as “the quit rate” because it measures the number of people voluntarily leaving their jobs, is the highest since June 2008, when the economy was in recession.

What can employers do to retain their talented Gen Xers? Here are four options:

Give Xers the chance to be in charge. CTI research found that nearly three-quarters of Gen Xers (70%) prefer to work independently. Among those who like being their own boss, over 80% say the reason is that they value having control over their work. Highly self-reliant, Xers are individual players who “work well in situations where conditions are not well defined, or are constantly changing,” according to a generational report from the Society of Human Resource Management. Placing Xers in charge of high-visibility projects is a way to spotlight their abilities.

Show them the route to the top. Mentoring and sponsorship programs that match mid-level managers with senior-level executives not only provides opportunities to enrich Xers’ career experience; such relationships help pave the path to top leadership positions.

Encourage entrepreneurial instincts. Following in the footsteps of generation-mates like Dell computer founder Michael Dell, chief Googlers Larry Page and Sergey Brin, and Sara Blakeley, who created the multimillion-dollar Spanx empire, nearly 39% of Gen X men and 28% of Gen X women aspire to be an entrepreneur. Why not let them test their wings with a company-sponsored venture than risk having them fly the coop?

Offer flexibility. Extreme jobs — characterized by workweeks of 60-plus hours, unpredictable workloads, tight deadlines, and 24/7 availability — are the norm for Gen X, with nearly a third (31%) of Xers making over $75,000 a year slogging through schedules that never stop. Flexible work arrangements, including reduced schedules, are checked off as “very important” for 66% of Gen X women and, significantly, 55% of Gen X men. Even childless employees yearn for better work-life balance to pursue their own interests.

Generation X may feel they’re the “wrong place, wrong time” generation, caught in a chronological squeeze between the Boomers and the Millennials. For smart employers, though, Gen X is in exactly the right place at the right time — seasoned skill bearers and experienced knowledge experts endowed with a work ethic that gives wings to their soaring ambition.

Employers can retain restless Xers by responding directly to their concerns: offering them a chance to test their leadership potential through work-sponsored entrepreneurial opportunities, a safety valve to alleviate the pressures of their extreme lives, and a way to celebrate the varied passions and commitments that make this talented cohort so valuable.

Collect Your Employees’ Data Without Invading Their Privacy

Research shows that businesses using data-driven decision-making, predictive analytics, and big data are more competitive and have higher returns than businesses that don’t. Because of this, the most ambitious companies are engaged in an arms race of sorts to obtain more data, from both customers and their own employees. But gathering information from the latter group in particular can be tricky. So how should companies collect valuable data about time use, activities, and relationships at work, while also respecting their employees’ boundaries and personal information?

In helping our customers adopt people analytics at their own companies, we’ve worked directly with legal teams from large companies around the world, including over a dozen in the Fortune 500. We’ve seen a wide range of cultures, processes, and attitudes about employee privacy, and learned that in every case there are seven key points that need to be addressed for any internal predictive analytics initiative to be successful:

Find a sponsor. The team that’s proposing the data analysis needs to have real power and motivation to change the business based on the findings. Most need a sponsor in a senior-level position for this kind of institutional support. First, this person can help balance opportunistic quick wins with a long view of how predictive analytics fits into strategic plans. He or she should also explain why the data collection and analysis is so important to employees across the organization, and can serve as the person ultimately accountable for ensuring that the data stays private. In many cases, if a company’s legal team doesn’t see strong sponsorship and support, they are likely to de-prioritize approval of the initiative — to the point where it may be forgotten entirely.

Have a hypothesis. Before you start collecting data, decide why it’s needed in the first place. For one, legal departments can’t often approve a project without an objective. But in addition, the team proposing the project needs to be clear and transparent about what they’re trying to accomplish. This includes having a tangible plan for what data is being sought, what changes will be made based on the findings, how the results of these changes will be measured, and the return on investment that justifies the time and energy put into the project.

The hypothesis can be as specific as “underperforming customer accounts are not getting as much time investment as high-performing accounts,” or as general as “correlations will be found between people analytics metrics and business outcome x,” but the outcome needs to matter. Projects without a purpose confuse people and incite skepticism, setting a bad precedent for future analytics efforts.

Default to anonymity and aggregation. There is more to be learned by examining the relationship between sales and marketing as a whole than there is by examining the relationship between James in sales and Elliott in marketing. Analytics initiatives are not the place for satisfying personal curiosity. In our work, we use metadata only, usually beginning with email and calendar. By default, we anonymize the sender and recipients’ email addresses to their departments. To further protect anonymity, we aggregate reporting to a minimum grouping size so that it’s not possible to drill down to a single person’s data and try to guess who they are. This removes the possibility of even innocent snooping.

If you can’t let employees be anonymous, let them choose how you use their data. In a few cases, business objectives can’t be met with anonymous data. Some of our customers, for example, conduct social network analyses to identify the people who make important connections happen across disparate departments or geographies. After identifying these key “nodes” in the social graph, managers will interview them and then help them influence others. In a case like this, the best approach is to ask permission before gathering the data in one of two ways:

Using an opt-out mechanism is the simplest. Employees are sent one or more email notifications that they will be included in a study, with details on the study plan and scope. They have to take an action (usually clicking a link) to be excluded from the study.

Opt-in earns a bit lower participation, because recipients have to take the action in order to be included in the study. More sensitive legal teams may require an opt-in.

Whether it’s opt-out or opt-in, the worker should know what’s in it for them. We find that the most relevant reward is access to data — after all, most people are curious how they compare with their peers across various dimensions. We provide people with personal, confidential reports that compare their own data to organizational benchmarks, and this helps give them an incentive to participate. Real, personalized data also helps to make the message about the study interesting, cutting through the inbox noise so the opt-in gets attention. And if you don’t have the ability to give people back their own personal data, you can promise future access to some form of aggregated study results to reward them for participating.

Screen for confidential information. Then screen again. Certain teams, such as legal, HR, or mergers and acquisitions, will be dealing with more sensitive matters than normal, and their data may need greater protection. Whether data will be gathered from humans, electronic sources, or both, sensitive information should be screened out in two ways:

Don’t gather it in the first place by configuring the instrument to exclude keywords, characteristics, or participants that would indicate sensitivity.

Re-validate and remove any data that wasn’t screened by the initial configuration, because both people and software can miss the meaning of textual information. Perform a second validation before sharing the data with the final audience.

Don’t dig for personal information. Every person experiences interruptions in their workdays for personal reason — dentist appointments, children’s activities, etc. At the same time, by policy, some companies protect their employees’ privileges to use company systems for personal reasons. Regardless of policy, there really isn’t much business value in looking analytically or programmatically at data about peoples’ personal lives, and we automatically exclude it from our dataset. The bottom line is that employees have a human right to personal privacy, as well as significant legal rights that vary in different countries. Personal matters should be handled by managers, not by analytics initiatives.

For additional protection, consider using a third party. It is common in some applications for a third-party vendor to perform the data cleansing, anonymization and aggregation, so that the risk of privacy violations by employees of the enterprise is removed. This work can be performed by third parties even within the firm’s firewall, if desired. But there’s an important caveat: Companies that handle sensitive data should follow security practices, like background checks for their employees who have access to the data, and should not, in general, use subcontractors to perform their work.

The opportunity in data and predictive analytics, particularly people analytics, is huge, which makes it especially important that companies take a responsible and proactive approach to privacy. By collecting and using data in a way that respects and rewards employees, leaders remove friction points in the adoption of increasingly valuable analytical capabilities. The seven practices outlined will help clear the path for pioneering programs and build an organizational culture that prizes and rewards analytical thinking at all levels.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers