Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1362

September 23, 2014

We Can’t Talk About Inequality Without Talking About Talent

Anyone thinking about democracy and capitalism today needs to take account of Thomas Piketty’s monumental book, Capital in the 21st Century. There lots of similarities between his argument and the one I make in my most recent HBR article. We both look squarely at the same phenomenon — income inequality — and have similar interpretations and I am thrilled at the huge positive impact that he has had on this important issue.

There are also important differences — or complementarities, I would like to believe. To begin with, he is a macroeconomist and as such he sees natural resources, capital, and labor as the prime drivers of economic productivity. From this perspective, inequality is a function of the accumulation of capital, which provides control over natural resources, principally land, and allows the capitalist to collect increasingly huge rents from such ownership. I concur that during most of the 20th Century, that was a pretty good way to explain income inequality.

But I’m a business strategist and from where I’m looking, the game has changed dramatically in the past 50 years. Talent has become the critical force in the economic equation, more important than either raw materials and labor, and a worthy if not overwhelming adversary for capital.

To be fair, macroeconomists don’t view human resources as completely generic “labor.” Many have worked on the returns to skills and returns to education, showing that labor is more highly paid if it is educated and skilled and also that it increases business productivity. However, they don’t see talent as a distinctive actor in the economic equation, an opponent of capital independent of labor.

But my take is that talent is now a force in its own right. Every capital-intensive business is threatened by the proverbial two-kids-in-a-garage who might demolish it, without the benefit of either capital or natural resources. Whether they are Hewlett and Packard, Jobs and Wozniak, or Page and Brin, established and accumulated capital has everything to fear from the power of talent. And increasingly, this talent is aimed at taking all the spoils. Its implicit goal is to be the moral equivalent of equity capital. It wants to capture all of the upside. And it wants to turn equity capital into the moral equivalent of debt — it should earn a fixed return on its investment and nothing more.

To be sure, Piketty does note (with some incredulity) the rise of the “supermanager” as an economic agent but in the end, he still sees capital accumulation by investors as the main source of inequality and the biggest challenge to the functioning of the modern economy. I think that recognizing the importance of talent enhances the quality of the picture. As I argue in my article, managerial and entrepreneurial talent has started to extract a huge share of economic rewards, at the expense of both traditional capital and traditional labor.

The second enhancement that I would suggest to the Piketty narrative is to draw a distinction between the real economy and the capital markets. The real economy is the one in which real companies, individuals and governments buy and sell real things for real prices. Macroeconomists (such as Piketty himself) add up these real transactions to produce numbers like Gross Domestic Product.

The capital markets, however, are not the real economy. The value of stocks and bonds are not directly determined by economic actions or events. They are driven by expectations of future economic actions and events. Market participants imagine what will happen in the future and pay prices for securities — whether stocks, bonds or real estate investments — that reflect their beliefs about the future value of such securities. That future may or may not happen but in the intervening time, those who make such projections define the value of those instruments with their shared expectations.

This may sound like semantics, but one of Piketty’s key observations is that a vast amount of capital was “wiped out” during the crises of the two World Wars and the Great Depression in between. I see things a bit differently. Yes, hard physical assets like buildings and machinery in France, Germany, and England were indeed destroyed by bombs in the great wars. But those losses pale in comparison to the paper losses on the value of financial securities caused by lower expectations about future economic performance, which is what Piketty observed as the destruction of capital.

In my view, however, paper losses on financial securities don’t necessarily equate to the destruction of capital. There is a story (possibly apocryphal) about Hong Kong’s richest billionaire, Li Ka-Shing, that illustrates this point. In the middle of the great Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, a huge one-day fall in the value of Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index drove down the market value of his holdings by close to US$10 billion, then the largest one day fall in an individual’s fortune ever recorded.

Asked by a reporter about how he felt about this, Li reputedly replied that he hadn’t lost a single dollar: “What have I sold in the last day? Before the price drop, I owned a set of assets. After the drop, I own the same assets. I am no poorer. Their earnings prospects were the same the day before and the day after. Had I sold, I would have been poorer, but I didn’t.” He was absolutely right and the value of his holdings soon returned to more than their previous glory. The same happened to capital in the modern democracies after World War II. The resurgence of capital values in the 1950s was not about the creation of new assets to replace those destroyed by war but rather a re-evaluation of assets that had largely always been there.

The distinction is important because managerial talent is largely rewarded through the expectations market, though equity-based compensation. That opens up the possibility (I would suggest certainty) that managers will focus on shaping (or even manipulating) expectations more than creating real economic value in the form of products, services, and jobs.

The bottom line is that we need a richer story about inequality that takes into account the importance of talent and the difference between the real economy and the capital markets. Saving democratic capitalism from itself will need that understanding, because what’s going wrong with our economy is a vicious dynamic in which a talent elite not only appropriates an ever-greater share of economic rewards but also channels its energies away from economically productive activities. To me, the key challenge to democratic capitalism in the 21st century is talent, not capital.

September 22, 2014

Boards Are Terrible at Their Most Important Job

The chief responsibility of any board is management of the senior executive. Yet a recent Bridgespan Group survey of nonprofit CEOs found that nearly half (46%) got little or no onboarding help from their boards. As one executive put it, “The board essentially said, ‘We’re glad you’re here. Here are the keys. We’re tired.’”

When it comes to managing the CEO, many boards underperform.

This shortcoming is understandable, especially for nonprofit boards. Board members are mostly volunteers. They’re busy. They have other jobs. And according to a 2010 report by BoardSource, such individuals are typically brought on for their professional expertise and ability to represent constituents — not for their talent in managing people.

Books and articles abound on how to manage the arrival of a new leader. Yet for many nonprofit boards, access to good advice hasn’t changed lackluster behavior. In an effort to understand why, we surveyed top executives across the U.S. (214 responded), reviewed the literature, and interviewed 30 experts, board members, and newly hired executives. Our findings revealed a number of pitfalls and led to a handful of recommendations aimed at boosting a board’s performance where it counts the most: onboarding and supporting a new CEO. While these suggestions came out of our research on nonprofits, they are applicable to any board bringing on a new leader.

1. Lay the groundwork for the new leader. Even before the recruiting begins, make clear what skills and attributes the organization needs in a new leader. Consider the organization’s potential growth, restructuring, new programs, and strategies. “I help my clients do a mini-visioning session before we start looking for a new CEO,” says search executive Anthony Tansimore, vice president of leadership impact at Olive Grove. “This helps the board define their goals for the future and what they need to do to get there.”

Once the new CEO is selected, boards should also try to facilitate a connection between the incoming and outgoing leaders. Zach Bodner, CEO of the Oshman Family Jewish Community Center, says that he had weekly appointments with the interim executive director months before he officially started. “[The interim executive director] made a comprehensive agenda of different topics we needed to cover,” recalls Bodner. “From our conversations, I developed a learning plan and an action plan.” It covered, among other things, what to say at his first staff meeting and goals for the first 30, 60, and 90 days.

2. Collectively set priorities. Our survey showed that 39% of respondents felt their board was ineffective in helping set first-year priorities. “The board and the incoming CEO must agree on what their accomplishments should be, and in what timeframe,” says Tom Adams, author of The Nonprofit Leadership Transition and Development Guide. “If that discussion never takes place, the board and the new leader will likely form clashing assumptions about what is expected and when.”

To reach a common understanding of the new CEO’s main goals, create a leadership agenda that does several things: clarifies the organization’s priorities; outlines action plans, roles, and milestones for each priority; and identifies gaps in organizational ability or capacity to achieve them.

3. Get clear on roles. Only 50% of the leaders we surveyed said their boards were clear about how they would work together in the first few months on the job. Questions to consider include: who sets the board meeting agenda, what decisions will the board participate in, and how frequently should the board chair and CEO communicate? The more detailed a board can be with their new CEO about expectations, the less likelihood problems will arise later. One board chair of an international youth development organization recalled how the new executive director received “no guidance on how to interact with the board,” an oversight that created tension and mistrust several months into his tenure.

Role definition should also be clear for departing leaders, particularly founders or leaders who are retiring. Often these people want to stay closely engaged, which in the long term can confuse the staff, create divided loyalties, and sow doubt about the competence of the new leader.

4. Go slowly in orientation to go fast on the job. The survey revealed 58% of CEOs were dissatisfied with their first few months of onboarding. “Too many leaders are fighting fires from day one, and they miss a critical window to understand and assess the organization and build strong relationships,” says Tim Wolfred, author of Managing Executive Transitions: A Guide for Nonprofits. “As a result, they get off to a limping start and could end up playing catch-up for years.”

To ensure that the new leader has time to gain a sense of the organization’s strengths and weaknesses, the board may initially keep some day-to-day duties off the new leader’s plate. In some instances, the board chair takes on a mentoring role, becoming the new CEO’s partner in the onboarding process. But onboarding is not just the chair’s responsibility. It’s also a good idea to set up a transition committee—composed of board members and staff—to develop an orientation plan to introduce the new executive to staff, board members, funders, and other stakeholders. The plan also should include assembling important documents and scheduling briefings on functional and programmatic areas, steps that get the leader into the flow of the organization.

5. Make performance management routine. Fully 66% of the CEOs we surveyed reported that their boards failed to establish concrete measures and milestones, including regular feedback and guidance, for their first-year performance assessment.

The board and the CEO should set a timeline to meet, perhaps starting with a 90-day informal check-in and then set an initial formal review at the six-month mark. This is in addition to frequent conversations with the CEO and board chair. The board also should be proactive about providing support to the executive director. One powerful way to accomplish this is to hire an executive coach. Amy Saxton, CEO at youth development nonprofit Summer Search, gratefully accepted a board member’s recommendation that she work with a coach. “She knew that I needed someone who wasn’t associated with the organization to help me think through how to approach situations,” said Saxton. “It wasn’t a sign of my weakness; it was recognition that all leaders need support, especially when they’re taking on a new role.”

While these five recommendations may not be terribly surprising, it is surprising that so few board employ them. All boards have the capacity to ensure that their organizations hire and support strong leadership. They just have to make it a priority.

This article is based on “Boosting Nonprofit Board Performance Where It Counts,” published by Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Scotland’s Vote Didn’t Clarify the Path Forward

Scotland voted against independence on September 18 with a clear, though not overwhelming majority. But the vote hasn’t really settled the issue: on the contrary, the lead-up to the referendum, and its aftermath, will have a deeply traumatic impact on the UK as a whole. And the political dynamics surrounding the vote have troubling historical resonance, which UK and European leaders should heed.

The London government’s wide-ranging promises of greater devolution of powers to Scotland comes with a serious catch: many English parliamentarians believe that now they should make decisions on their own (without Scottish interference) on key issues such as education, health and welfare, which are not matters of identical concern for the whole UK.

This raises a fundamental problem for future British politics. The convention of the unwritten British constitution is that the party or parties that have a majority of seats in the UK parliament should form the government. But in the future, a government produced in this way may well not be in a position to enact the sort of laws for England that its voters would prefer. Labour is better represented in Scotland (and Wales) than the Conservatives: there might well be a Labour majority in the UK and hence a Labour government, while the English constituencies would have a plurality of Conservative or UKIP (anti-EU) members of parliament. So would there be a separate English government, which voted on education, social services, transport, and of course their fiscal consequences, while the UK government just thought about defense and foreign policy? The resulting constitutional mess would prompt further pressure to escape from the old Union of England (and Wales) with Scotland that dates back to 1707.

The political and economic arguments that drove towards the vote will not simply disappear. Independence-seeking Scots will continue to see the highly successful small states of Scandinavia as an attractive model: these countries have a powerful social democratic tradition. Norway, in particular, with its gigantic revenue from North Sea oil and gas looks like a template. Most of the British gas reserves are off the Scottish coast, though they are probably not substantial enough to sustain a Norwegian-type welfare economy. Many Scots also don’t like the global role of the UK (and the defense costs that go with that role). They think that life would be easier without the entanglements that seem to them just the afterlife of an empire that has really ceased to exist.

The Scottish campaign was also about escaping from an economic arrangement that shackles Scotland to the City of London and finance. Scotland had a bad experience with modern financial innovation, with two banks, RBS and HBPS, that tried to be global players and then failed catastrophically in the financial crisis. Worry about dominance by remote financial institutions is a sentiment that would have appealed to the greatest Scottish economist, Adam Smith. Smith’s greatest work, The Wealth of Nations of 1776, was underpinned by the belief that British commercial policy was distorted by the interests of the London merchant community, and looked for a way out of its hegemonic tutelage.

It is also easy to see other parts of the UK – say Wales, or northern England – feeling the attractions of those still-valid Scottish concerns. London and the South-East would be left on their own as an enclave of a rich global financial elite (maybe a version of Switzerland, or Singapore). Such transitions, when they occur, are never smooth and painless. It was probably the sheer inconvenience and uncertainty about the path to independence that tipped the scales in the referendum.

Are there any good historical parallels to the painful constitutional debate that is only just beginning? The uneasy relationship of England and Scotland – with the resulting shift in attention of other European regions such as Catalonia and northern Italy to their grievances with the existing political and constitutional framework of the nation-state – has overtones of the tensions that increasingly tore apart the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the decades before the First World War. In the Dual Monarchy, as formed by the constitutional compromise of 1867, Austria and Hungary had their own parliaments, but a common emperor and a common foreign policy and external tariff.

A brilliant (and only very recently translated into English) trilogy of novels by a Hungarian aristocrat, Miklós Bánffy, elegiacally describes the descent of the Habsburg Empire into chaos. Bánffy thought it his main task to castigate retrospectively his class – the political elite – for the confusion, and a break-up which left everyone worse off and much more embittered. He describes the system of the old monarchy as based on the “historical and emotional existence of an illogical fact.” His characters quarrel over exactly the sort of issues that divide modern Britons – should there be anything other than a common foreign policy? Should there be separate national central banks? How would devolution affect the allocation of credits to different parts of the Empire? Bánffy describes a parliament where the law-making process degenerated into time-wasting procedural tussles, and everyone waited for some political earthquake that would clean up the system. Sound familiar?

The three Bánffy novels – They Were Counted, They Were Found Wanting, and They Were Divided – had biblical titles and included a biblical epithet – Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin – from the writing on the wall at Belshazzar’s drunken feast foreboding the end of the Babylonian kingdom. The intricate story of the Habsburg collapse into nationalism and particularism forms a powerful Mene Tekel for the travails of contemporary Europe. Once the rigor of separatist logic is systematically applied to any political system, it disintegrates. And that disintegration is costly.

Getting Past a Career Setback: An Example and a Test

Managers often think about their careers in terms of winning and losing. Winners ascend the corporate ladder and get the praise, recognition, bonuses, and top jobs. But what about those whose careers are sidetracked or derailed when passed over for a key assignment or big promotion? Or those who find themselves on the short end in the latest reorganization or merger selection? Are these “losers” out of the running for career advancement, or can they regain their footing, refocus their sights, and continue to rise?

Very few managerial careers proceed upward in a straight line. So, the real challenge for career success is not just how to “win” the next promotion, but also how to rebound from the next defeat, as we explain in our article in this month’s HBR.

Here’s a case example. With a background in both strategy and finance, Sheila was an up-and-coming manager at a well-known consumer products company. When her firm decided to invest in start-ups, she was asked to put together a team to make it happen. Over the next year, she recruited a small group of professionals, targeted a number of sectors that would make a difference for the company, created a process for sourcing and managing minority investments, and began to make deals.

Eventually her team ended up with a portfolio of investments that caught the attention of the CFO and CEO because some were bringing new technologies into the company’s supply chain, and others were hinting at new business models for engaging with customers. Soon she was meeting regularly with the senior executive team about deals and overall strategy. Unfortunately, her success made her direct supervisor and the head of corporate strategy jealous – and they engineered a reorganization that moved the innovation team under the strategy office and left Sheila as an individual contributor.

Naturally, Sheila was upset. She went through the emotional stages of loss, anger, and bargaining. She made her case for regaining the team to the CEO and several other executives, but soon discovered that while all were happy with her work, no one wanted to intervene or offer her a different role.

Through this process, Sheila realized that while her boss and others had probably acted poorly, she was partly at fault for not managing the relationships and politics more effectively. While she was basking in the glow of attention from the C-suite, she had not helped her supervisor or other peers receive enough credit. This insight helped distance her from the problem, so she could stop blaming others and start thinking about what to do next.

After several months of emotional churning, Sheila decided to focus on Plan B –figuring out what she really wanted to do instead of trying to overturn an “injustice.” Through discussions with a number of trusted advisors, she realized that her work of the past several years had given her fantastic contacts, experience, and credibility in the innovation world. This led her to think about launching her own start-up by combining a couple of struggling new ventures with some additional funding.

At the same time, a few discrete inquiries revealed that a private equity firm was very interested in having her roll up some consumer-based start-ups into a new business. And an innovative manufacturing company offered her a job as head of “strategic partnerships.” Of course, Sheila still had her job – and could even pursue other roles – in the consumer products company if she wanted to stay.

As she examined herself and her environment, she realized she had more opportunities than she could possibly pursue. Eventually she chose the strategic partnerships role with the manufacturing company – not only because it was an interesting challenge, but also because it would give her an opportunity to pay more attention to relationships and politics. She could leverage her past experience and use it as a springboard to continue her development.

The key to Sheila’s eventual rebound is that she used her setback as an opportunity to learn, reflect, and regroup. This allowed her to treat the situation not as a frustrating failure, but as an act of liberation – to get off of the path she was on and to consciously choose whether to continue it or select an alternative.

The lesson here is that careers aren’t just about “winning.” In fact, for most people, success requires an ability to turn inevitable losses around. And that takes time. Note that Sheila did not rush, give in to anger, or rashly jump ship. She used the setback as a chance to rethink her career, collect feedback from others, and wait for the right opportunities to present themselves.

How well do you rebound from career setbacks? Take our assessment to see whether you could improve.

How to Tell If You Should Trust Your Statistical Models

Predictive analytics often sounds a bit like quantum mechanics: fiendishly complex to look at and wildly counter-intuitive. So when someone sells you a tool, how can you verify that the black box is fit for its purpose or even lives up to the vendor’s claims?

Of course, there never are ironclad guarantees around prediction; the future can have more shapes and colors than we ever imagined. But you’ll be more likely to get the best out of your predictive analytics if you ask the following basic questions in evaluating new predictive models:

Q1: Are the data good? Make sure the data used, as well as the processes that generate and organize it, are of the highest possible quality, and that you fully understand them. As a hedge fund manager who applied data-driven trading strategies once said, “You can spend endless time and resources only to find eventually a bug in your data.”

You can get problems even with the best data. In a recent study of the daily close prices of S&P500 stocks, we “discovered” what looked like striking patterns in stock movements. When we looked more closely, we found that the patterns were explained by the fact that what was meant by the “close price” of a stock is very loosely defined. The term had multiple definitions, all of which were applied, including, for instance, the “last price before 4 PM” and the “last price reported in the closing auction.” Once we defined the term more narrowly, the patterns disappeared. We imagine that many other people will fall into a similar trap and see patterns where none exist because they haven’t thought hard enough about what the data they’re looking at actually are.

Q2: Does the model tell a story? Sound models usually tell a clear story. If the predictive analytics you’re using don’t give you one, beware—the models may need to be refined. This is not to say that the story has to be what you expect or that it has to be a simple one-line statement. It is rather that the story has to be understandable to the people basing their decisions on it. It is not about avoiding complex statistical models, which of course are often necessary, but about having thought through, refined, and simplified the models enough to be able to understand them.

Q3: Is the math as simple as it can be? It’s natural to assume that the model that does the most with the most variables will be the best model. But theory, such as Statistical Learning Theory in Machine Learning, teaches us that predictability typically first improves and then deteriorates as model complexity increases, so adding complexity should not be a goal in itself. This is precisely why describing a model using a simple story that makes economic sense is often a good sign of a refined model with the right level of complexity. Of course, there are equal risks to oversimplifying the math, so don’t go too far in that direction either. Einstein is often quoted as saying, “Everything should be as simple as it can be, but not simpler,” a good principle to apply to predictive analytics.

Q4: Is the predictive accuracy stable across different, fresh data? All too often analysts study historical data to develop a model that explains that data and then apply the model to the exact same data to make a prediction about the future. For example, developing a credit scoring model using data of past defaults and then testing the model on that same data is an exercise in circularity: you’re predicting what you’ve explained already. So make sure that your analysts apply the model to fresh data in new contexts. More importantly, check that the predictive accuracy of the models is reasonably close to how well the model succeeded in explaining the data it was developed to explain; prediction accuracy should be similar across multiple environments and data samples.

Q5: Is the model still relevant? Confirmation and other behavioral biases, along with the “sunk cost” fallacy, often encourage people to see predictability where there is none, especially if there was some before. But if the data don’t support your predictions, you should be prepared to jettison your model—possibly multiple times. Even if your model has a track record, you should still test whether it remains relevant to the economic and business context. Using predictive models of demand developed during growth years or for a price sensitive market segment may fail miserably when market conditions change. This makes predictive analytics by nature risky: they are valid as long as the reality they were developed in, the data describing a specific market during a specific time, is also valid.

Developing and applying predictive analytics requires a delicate balance between art and science. A deep contextual understanding with very honest interpretation and story development should be balanced with hard facts and statistical analysis. And always keep in mind that the most predictive analytics models can become fully non-predictive in a fortnight—just imagine how some financial models looked the day after the Lehman collapse.

Why We Should Teach Entrepreneurship to Disadvantaged Students

Can we afford to shut the door on bright, motivated would-be entrepreneurs whose ideas could one day change the world? I don’t think so, but that’s exactly what’s happening all around the globe.

Young people with the potential to become business leaders are too often unable to get past the disadvantages of poverty and a lack of access to knowledge and support.

Look in any low-income area, whether it’s a favela or a rural village or a run-down section of an American city, and you’ll find young people with the characteristics needed for entrepreneurship: curiosity, confidence, and a propensity to break rules. The latter trait is an important part of the mix. In a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, young people who engaged in “more aggressive, illicit, risk-taking activities” tended to score higher on learning-aptitude tests, had greater self-esteem than their peers, and were more likely to undertake entrepreneurship ventures as adults.

It makes sense that rule-breakers are well-positioned to start businesses. Entrepreneurs are more comfortable setting their own rules than staying within limits set by others, and they often have little respect for authority — educational, cultural, or even legal.

Young would-be entrepreneurs in low-income areas have another factor in their favor, though calling it an advantage may seem strange or callous. Adverse personal or economic environments can be motivational for risk-taking. Many research studies have found a link between poverty and entrepreneurship. Whether it’s because of a lack of job skills and employment options or some other factor, this too makes sense. When you’re facing adversity, even a highly risky venture seems like a better option than staying where you are.

But future business leaders in poor areas lack two crucial things that have been shown to be crucial for entrepreneurs: direction in how to pursue their goals in focused, responsible, productive ways; and safe spaces where they can try, and fail, and try again, and where the impact of negative consequences can be cushioned.

My organization, NFTE, tries to provide both of those elements in classroom settings in dozens of U.S. communities and nine additional countries.

Some entrepreneurs scoff at the value of classroom learning. But when NFTE teaches entrepreneurship to underserved and disadvantaged students, we find that the classroom setting allows teachers to serve as mentors and provide direction, showing students how they can use their abilities and circumstances to succeed in business. Teachers arm students with business skills such as writing a business plan, marketing, and calculating profit and loss. The classroom also gives would-be entrepreneurs the chance to innovate and disrupt without negative consequences. The results can be both life-changing and economically positive.

Jordan Brooks, an NFTE alumnus from Maryland, was always a risk-taker. “I spent most of my childhood as a rebellious young man who constantly got himself in trouble — then in deeper trouble as I tried to cover things up with more bad decision,” he says.

But Jordan had unusual skills and abilities: “I can read people, understand people, find the ‘why’ in people,” he says. After taking an entrepreneurship course, he started to see things differently. Before being in entrepreneurship classes, he’d been doing design work as hobby, spending hours buried in a copy of Adobe Photoshop that a neighbor had given him.

Thinking like an entrepreneur allowed him to “recognize the potential business opportunity in this … and make it possible,” he says.

Realizing his hobby could be productive and profitable for him, he started a local graphic design company — Threshold Graphics — which he projected would make him $22,000 a year in profit while he was still in high school. With a new focus, Jordan became his high school valedictorian and is now working full-time as a graphic designer for Deltek, an enterprise software company.

Hundreds of millions of new jobs will be needed in the next quarter-century, and that means many more entrepreneurs will need to create many new companies. But the world will miss out on the talents of thousands of at-risk young people who are would-be business leaders unless a greater effort is made to teach and nurture the world’s smart, confident, disadvantaged rule-breakers.

5 Tips for New Team Leaders

I’ve been a new manager five times in my career: once as a first-time manager at Google going from being a teammate to leading peers, three times as I was promoted within Google, and most recently as the new Chief Revenue Officer for UberConference, a teleconferencing startup in San Francisco. What I’ve found is that success out of the gate is normally tied to being truly open to learning, communicating openly and honestly, and ultimately being prepared to take action when you know where the team needs to head.

To that end, here are the key things I’ve learned along the way:

Over-communicate. When someone new joins a team, it generally creates some nervousness. Everyone wants to know what you’re going to change and where you’re going to take the direction of the team. Be as open and transparent about what you’re thinking as quickly as possible. You can start by outlining your 30-day plan. While you may not have any opinions specific to the business yet, you can tell people what you want to learn about and evaluate. Additionally, the more transparent you can be, the more comfortable people will feel being similarly candid with you. You may not know your strategy, but you can certainly talk about your values, priorities, and observations.

Ask questions. I make a rule that about 50 percent of the words coming out of my mouth should end with a question mark in the first 30 days. I’m also explicit with people that all I plan to do is ask questions in the first month (which helps me hold myself accountable to that!). When I first became a manager, I was introduced to the concept of being a “knower” versus a “learner.” A knower assumes she has the answers, whereas a learner will admit that she doesn’t — even if she has significant experience. Being genuinely excited about the opportunity to learn and understand what’s going on within the company builds credibility, and generally makes you more approachable.

Figure out what people really want to do. In one of my new roles at Google, I managed a woman who was in the sales organization as a Demand Management representative. After chatting with her about her career aspirations and what got her most excited to get out of bed in the morning, I realized that she had real untapped talent on both the creative and analytical fronts. I didn’t really have a role for her yet, but knew she was being underutilized. I shifted her to being my “analyst,” which basically meant someone who would work with me on whatever big project I was tackling. She ended up being one of the top performers in our organization, and now is part of a global SWAT team that helps fundamentally rethink key go-to-market tactics. You probably have a lot of people just like her in your organization. Meet with all of your direct reports for at least an hour within your first week. Ask them about what they really enjoy doing and what they aspire to be doing in the next 2–3 years. It’s often the case that the role the individual is in today isn’t necessarily fully utilizing their skills or motivating them to be their absolute best. Quick changes in role definition can turn a solid player into a rockstar.

Get your hands dirty. Spend time doing the work that your team actually does. Not only does this help establish you as someone who leads by example, but you also learn first-hand about all of the different challenges that people experience every day. At UberConference, we have every new member of the team spend a week as a guest member of our customer support team. As a result of those experiences, everyone is far more connected to our customers, and changes to the product, tools, and messaging are implemented immediately because that first-hand experience creates passion. If you can understand what it’s fundamentally like to be on the front lines, you have unique perspective when making larger strategic decisions and communicating them to your team.

Be decisive. Once you have a good lay of the land, explicitly lay out your vision and then plan to start moving toward it. People feel less unrest when they understand the bigger picture and can see where things are heading. In my experience, this is often the hardest thing to do when you’re new, and also the hardest to recover from if you don’t do it. At Google, I relocated to Australia to run our Asia Pacific sales organization. I got this opportunity despite knowing nothing about the region and never having been a sales representative — or having managed a sales team, for that matter. I immediately saw what I perceived to be workflow and sales skill issues. Rather than calling them out and putting a plan in place to address them, I kept trying to slowly mold things into a different state. I kept second-guessing myself and worrying that the sales team wouldn’t get behind the changes that I knew needed to happen. About six months into the job, a couple of the top reps came to me, pointed out that they knew what I really wanted, and told me they wished that I had just laid out the changes I wanted and asked people to up their game.

Being new is rarely easy, but if you’ve taken the time to be a learner and to get to know your team, chances are they will follow you when you step up and lead.

Map Out Cultural Conflicts on Your Team

When you’re on a global team, cultural differences can be complex and can often seem contradictory. The biggest challenge comes when differences are complex in surprising ways.

Here’s a letter I received from an executive at automotive supplier Valeo, a French company with big client bases in Germany and Japan, and a growing presence in China.

Hi Erin,

After attending your presentation at our annual conference last week, I’ve been thinking about the invisible cultural boundaries impacting the effectiveness of my global team.

When I moved to China, I thought the difficulty would be in bridging the cultural differences between Asians and Europeans. And it is true that the Asian members of my team are uncomfortable with the way our French and German members publicly disagree with them and give them negative feedback. I’ve coached the team members on how to moderate their approaches and reactions to work more effectively together.

But to my surprise, the most serious difficulties we have on the team are between the Chinese and the Japanese. The Chinese gripe that the Japanese are slow to make decisions, inflexible, and unwilling to change. The Japanese complain that the Chinese don’t think things through, make rash decisions, and seem to thrive in chaos. Not only do these two Asian groups have difficulty working together, but also the Japanese in many ways behave more like the Germans than like the Chinese—something I never anticipated.

I’d appreciate any thoughts and suggestions you may have.

Olivier

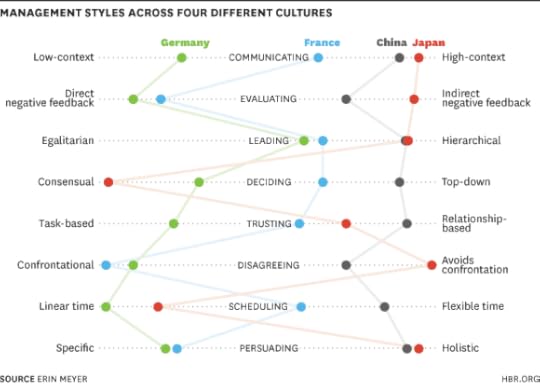

Olivier had attended my course at INSEAD on Culture Mapping. In this course we analyze the positions of various cultures on eight behavioral dimensions. The process and the eight dimensions are explained in the May 2014 HBR magazine article: Navigating the Cultural Minefield.

I love Olivier’s letter because it provides a perfect example of how the culture mapping process can help to move beyond sweeping assumptions and to instead tease out the specific cultural dynamics that impact effectiveness. Here is my response:

Dear Olivier,

Start addressing your problem by creating a simple culture map using the eight scales. Plot out each culture on the eight dimensions and draw a line connecting all eight points. This line represents the overall pattern of that culture on the map. I’ve done that for you with the four cultures from your team.

Now check the lines for Japan and China. On several scales, they are close together. As you’ve experienced, both the Chinese and Japanese cultures are less comfortable with direct negative feedback and open disagreement than Europeans. Reflecting that fact, on scales 2 (Evaluating) and 6.(Disagreeing), the Europeans are on one side and the Asian cultures on the other. But in most cases, the Japanese perceive the Chinese as very direct — note the difference between these cultures on scale 2 (Evaluating). The French see the Germans in the same way.

Next, take a closer look at scales 4 (Deciding) and 7 (Scheduling), and you’ll see the likely source of the frustration on your team. Although in Japan, like China, there is a strong deference to authority (scale 3, Leading), Japan is a consensual society where decisions are often made by the group in a bottom-up manner. That means decisions take longer, as input from everyone is gathered and a collective decision is formed. By contrast, in China decisions are most often made by the boss in a top-down fashion (scale 4, Deciding). Once the decision is made, there is a great rush towards the finish line.

Furthermore, the Japanese have a linear-time culture (scale 7, Scheduling). They build plans carefully and stick to the plan. Being organized, structured, and on time are all values that the Japanese share with their linear-time German colleagues. Indeed, on both scales 4 (Deciding) and 7 (Scheduling), the Japanese are rather close to the German culture, far from France and quite far from China.

In comparison, the Chinese (especially younger Chinese in big cities working for public companies such as yours) tend to make decisions quickly and to change plans often and easily, valuing flexibility and adaptability over sticking to the plan. On these two scales, (Deciding and Scheduling), the Chinese are closer to the French than to the Japanese.

Given these differences, it’s understandable that your Japanese and Chinese team members are having difficulty working together. Can the problem be solved? Absolutely. The next step in improving these dynamics is to increase the awareness of your team members about how culture impacts their effectiveness.

All the best,

Erin

What about your own global teams? What are the likely sources of cultural difficulties you’ll encounter with them? Over the years I’ve built up quite a lot of data on cultural differences and I’ve drawn on that work to provide pair comparisons for a number of counties, which you may find useful in working that out. You can see the comparisons on this interactive exercise:

Melanoma Incidence Is Much Higher for Flight Crews

Airline pilots’ and cabin crews’ incidence of the dangerous skin cancer melanoma is about twice that of the general population, and their death rate from the disease is 42% higher, according to a New York Times report of a scholarly analysis of 19 studies. The reason is unclear, but the researchers point out that exposure to the sun’s ultraviolet A radiation, a melanoma risk factor, is twice as great at 30,000 feet as at ground level, and airplane windows provide only minimal protection. The researchers suggest that crews wear sunscreen when they’re aloft.

The Salary Gap Between Stingy and Generous Companies Is Growing

What’s behind rising income inequality: the pay difference between janitors and CEOs, or the gap between how well different employers pay each position? Income inequality in the U.S. has historically more about the former. But a new NBER paper argues that the increase in inequality in recent years is actually driven largely by the latter.

Increasingly, the paper suggests, your income is driven by the company you work for, not just where you fall on the org chart.

The paper — by Erling Barth of the Institute for Social Research, James C. Davis of the Boston Census Research Data Center, Richard Freeman of NBER, and Alex Bryson of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research — looked at workers’ earnings*, as well as how much companies were paying in wages per worker. They discovered that from 1992 to 2007, the bulk of the increase in income inequality can be explained by a growing inequality in how well different firms pay.

The researchers considered the possibility that this finding reflected a sorting of talent. What if the top companies were attracting all the most skilled workers, and that’s why they were paying more? That dynamic is real, they discovered, but it explains only a small part of the trend. Instead, the majority of the growing gap between how well firms pay seems to be a difference in wages for similar roles.

“The road to understanding increasing inequality in the U.S. lies [in] the divergence of compensation for similar workers among establishments and firms,” wrote Freeman in an essay about the difference in how different hotels pay their workers, which he believes illustrates his research.

In some ways, though, hotel workers are not the typical case. While wage inequality between firms appears to be growing across geographies and without regard to worker productivity, it does vary by industry and pay grade.

The increasing inequality between companies is sharpest in finance, insurance, and real estate, followed by communications. And it is most pronounced for the highest paid workers. So rising inequality is less about every CEO getting paid more than it is about the top finance executives leaving their peers in the dust.

In his October HBR article on skyrocketing executive pay, Roger Martin relates a startling fact:

“The top 25 hedge fund managers in 2010 raked in four times the earnings of all the CEOs of the Fortune 500 combined.”

This squares with Freeman and his colleagues’ research. Making the top 0.1% isn’t just about making it to the top; you have to make it in the right industry and even then in the right firm. Financiers are leaving CEOs behind; hedge funders are putting bankers to shame.

We’re used to thinking about inequality as management vs. labor, but that is increasingly only one part of the picture. The growing divide between firms — and particularly how they pay their executives — deserves scrutiny as well.

*The compensation measure includes all labor compensation reported to the IRS, including bonuses and stock options.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers