Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1361

September 24, 2014

Money Matters More for Well-Being in Rich Countries than in Poor

Contrary to popular belief, people’s level of satisfaction with money and the material aspects of life has a stronger impact on their subjective well-being in wealthier countries than it does in poorer nations, according to Gallup surveys of adults in 158 countries. In developed societies, money is crucial for comfortable living, whereas in poor, rural areas, shelter and food can sometimes be obtained without money, via barter or subsistence agriculture, say Weiting Ng of SIM University in Singapore and Ed Diener of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the Gallup Organization.

What a Changing UK Can Learn from Multinationals

Following Scotland’s rejection of independence in the September 18 referendum, David Cameron, the British Prime Minister, has enlarged the scope of Britain’s constitutional debate. It is no longer a dialogue about increased powers for the Scottish Parliament, but a discussion about the relationships between the UK as a union of four nations and each of those four nations (England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, as well as Scotland).

The newest element of that wider dialogue is the idea that consideration is needed about the position of England. Previously, there has been a presumption that there was no need for a disaggregation of the interests of the UK as a whole and England, on the grounds that it contains 85% of the UK population.

The change in perception reveals a paradox. The Scottish referendum reflected a perception on the part of a substantial minority that the UK, dominated by England, had too much influence over Scotland, both direct and indirect. The view now held by many in England is that it is wrong that all members of the UK Parliament can vote on legislation applying only in England when the existence of separate parliaments in the other three nations precludes any reciprocal power of influence for politicians elected from England (the famous West Lothian Question).

These issues are not new to leaders of burgeoning multinational companies, in particular when they originate from the U.S.; for many of these, in fact, the domestic market still accounts for the majority of sales. Indeed, there is a parallel between these tensions in a governmental setting and those observable in multinational companies with geographical divisions for markets outside the home market but no separate division for the home market.

Tensions arose typically in three stages as a company internationalized. First, U.S. companies first started with establishing an international division, not so different from the Scottish office and Minister in the British government. Yet, and particularly before globalization made international experience a must for high potential executives, it was sometimes difficult for “international” to gain a voice at corporate against the preponderance of domestic concerns. So despite the establishment of the international division, internationalization languished. This is not dissimilar from the growing concern in Scotland since the 1980s that the British government was not sensitive to the specific needs of Scotland, and that its policies were perhaps better suited to England.

Devolution, the transfer of legislative and executive powers to a Scottish government and parliament, in 1999, was meant to address this concern. The corporate parallel was the regional headquarters that many multinational corporations created in the second stage of internationalization, each with its own regional CEO, who had a voice at corporate headquarters. With enough autonomy each region could adjust to specific local market needs.

Yet the broader problem of home market dominance did not disappear because not everything could be handled autonomously and the “share of voice” of the regions in the important decisions that still had to be made centrally remained small. What’s more, channeling regional interests via a single executive at corporate headquarters created a bottleneck, as one person could not provide representation for the region on all issues. Companies soon realized that centralization or regionalization was not a black and white choice; many key strategic and operational decisions had to be made in a dialogue. To structure the dialogue, many started using “decision grids” specifying the roles of different managers for specific decision classes on a continuum from inputting information to making the decision.

But even with this grid, regional managers often became bottlenecks and decisions continued to favor domestic concerns, throttling the internationalization process. Choices in strategy, labor relations, product specification, and advertising were often poorly suited to other regions around the world. And by remaining excessively home centric the multinational often deprived itself of access to unique skills and learning opportunities at the periphery.

To resolve this problem, many multinational corporations have restructured still further in a third stage through the creation of a “Home Region,” which puts domestic operations on the same organizational footing as the various regions in key decision-making. This solution is akin to what Cameron is now contemplating in the UK with the possible creation of an English Parliament and government, distinct from those of the United Kingdom, and similar in role and power to the Scottish institutions.

As multinationals have found, such a restructuring will involve greater ambiguity in the allocation of decision-making power and a deeper dialogue around decisions affecting both jurisdictions. As Cameron and his parliamentary colleagues embark on this debate, they would do well to consider the experience from those corporate restructurings.

September 23, 2014

How to Make Fossil Fuel Divestment Really Matter

The Rockefellers’ announcement that the family’s philanthropic trust would begin divesting from fossil fuels was a highly symbolic moment in the campaign against climate change. The nation’s most iconic oil family will no longer be profiting from the fuel sources responsible for overheating the planet.

But do such gestures actually help slow global warming? Divestment has its critics, and some analysts believe its direct effects will be limited. But the Rockefellers’ move may have more impact, for a key reason: their stated commitment to transition the divested funds to clean energy investments. The $50 billion to be divested is a drop the fossil fuel market’s bucket, but to the much smaller clean tech market it’s a tidal wave. And early-stage clean tech is particularly in need of an influx of capital.

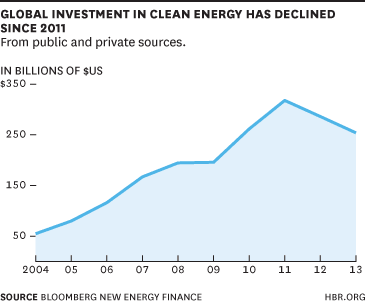

Last year, venture capital investments in clean tech totaled a mere $2.8 billion, according to Dow Jones. That marked a 50% decrease from its peak of $5.3 billion in 2011, despite the fact that venture capital funding overall has been increasing.

Some time shortly after the recession, venture capitalists decided clean tech wasn’t all it was cracked up to be, and started making bets elsewhere — mostly in internet start-ups. If the divestment movement can reallocate capital toward clean technology companies, that could have a far greater impact on mitigating climate change than divestment alone.

Later stage clean energy investments — like projects to deploy wind and solar — have remained somewhat more popular than early-stage start-ups, but are nonetheless down in recent years. Global clean energy investment also peaked in 2011, at $317 billion, and was down 20% from that peak in 2013. Cheaper natural gas prices have only made it harder for the still-nascent sector to attract investment.

The role for funds like the Rockefellers’ is to take the long view, investing in clean energy while others are distracted by the fracking boom or Snapchat’s valuation. Divesting from fossil fuels is just one small step — the giant leap is channeling that money into clean energy.

To Build Influence, Master How You Enter a Room

An airline industry executive has been promoted regularly for more than two decades because he’s good in a crisis. He’s cool, competent, and authoritative when the rest of the team is panicking. But now he finds himself in charge of a huge swath of the company — and a large number of employees. And the board is asking for something different from him: he needs to motivate people. For that, he has to emote — to show people he cares — something he’s hidden for over twenty years. Where to start? How can you wield influence while being empathic? It begins with how you enter a room.

Be aware of your unconscious cues. When you stand, are you taking up all of your space, or do you shrink into corners? When you move, do you move confidently, or do you slink? When you’re sitting alone, do you slouch or sit straight? When I began working with that airline executive, I noted that his tendency was to walk into a room as invisibly as possible. His shoulders were slumped, his eyes were down. In discussion, it turned out he had been bullied as a young teen for about five years. His body had borne the trace of that misery ever since. And he wasn’t even aware of the price paid in his posture — and in his day-to-day work. He couldn’t connect with others because he was afraid. In a crisis, however, he put aside his fears and focused on the job at hand.

There are two essential points here. The first is that you’re always signaling about your intentions and feelings, and so is everyone else. The second point is that most of the time you don’t pay conscious attention to all those signals — either the ones you’re putting out or the ones others are sending to you. Your unconscious mind handles all that. It determines an extraordinary amount of the relationships you have with other people and your influence upon them. Thus it’s essential to get a handle on these unconscious cues. Once you’ve formed a picture of yourself and have either embraced what you see or resolved to improve it, then you’re ready for the next step.

Focus on a key emotion. Think about the charisma of an actor like Kevin Spacey. How does he achieve it? Most people think of charisma as something you’re born with, but in fact we all have our charismatic moments. Think of a time when you’ve walked into a meeting, or come home to your significant other, and been asked without preamble, “What happened?” You’ve been brimming over with some news — either good or bad. You’re excited, or in despair, or triumphant, or whatever the case is. That’s charisma. It’s really about focus.

You need to focus your emotions before any meeting, conversation, or presentation. Most of us go through our days with lots on our minds — what Buddhists call “monkey mind” — and we think of one thing and then another like the random movements of a pinball in one of those old fashioned machines. That’s not charismatic. It’s just a to-do list. And it doesn’t compel attention. But the people who are able to free their minds of the usual daily detritus and focus on one emotion find that they compel attention. We are hard-wired to notice strong emotions in others. We have mirror neurons that fire (without us being conscious of them) when we see someone else in a state of great excitement, or anger, or delight. They leak their emotions to us; we are infected with them. That’s how they take over a room.

And finally, have something interesting to say. If you’re going to wield influence, you need to know what you want to be influential about. And you’d better have done your homework because once all eyes are upon you, everyone will expect you to have something worthwhile for them.

That’s how you build influence. Take inventory of how you habitually position yourself in front of the world and repair if necessary. Then, focus on a key emotion for any important meeting. And third, the place where most leaders mistakenly start, be prepared with something interesting and relevant to say. Leaders often start with content because it’s the natural job of the conscious mind. But connection, or its lack, begins in the unconscious mind.

Customers Are Better Strategists Than Managers

I was once appointed CEO of a company in need of a turnaround. We made trusses and frames for houses, and one morning, after I’d been on the job about three months, I found myself staring out my window, watching the trucks and forklifts below. I thought: What am I doing here? Can I, on the fingers of one hand, list the ingredients of success in this industry?

In the weeks and months that followed, the senior management team and I made a number of major decisions about the company’s future. As a team, I observed, we were busy doing things and making changes, all of which made sense to us as managers. But as time progressed, I returned to these questions, over and over: How well do we know what our customers want? How well do we know what our suppliers and employees expect? What would it take to meet those needs better than our competitors could?

In short, I’d begun to think in a way that I’d now call “strategic.” Up until that point, most of my focus had been on saving the company from ruin, which had led largely to “operational” thinking — worrying about the proper staffing numbers, the ratio of overhead costs to direct costs, the prices we were paying for supplies, how machinery was utilized in the plant, the overstocking and obsolescence of products used in manufacturing, the cash flow for the business, that sort of thing.

It was after I left that job and started working as a consultant that the penny finally dropped: I realized I’d been looking at the business from the inside out. From that perspective, all I could see was the activity that consumed my day. I also realized that customers and other stakeholders have the opposite perspective. Their view is outside-in, and that’s what makes them good strategists.

Think about it: As a customer, how often do you ask yourself, “Why don’t they…?” When you go to a department store, do you note which products should be added or removed? If you could have your way with the store’s presentation, would you change the layout, the lighting, and perhaps the color scheme? How about the service? No shortage of suggestions there, right? So it goes with airlines, telephone companies, banks, every organization you deal with — you’re continually redesigning strategic factors such as product range, presentation, and customer service. We all do it.

Now try doing that for own your organization. Suddenly it’s much harder, because it requires an outside-in view. Here are my suggestions for making it easier:

Tap your stakeholders. If your company’s two-day offsite involves a group of senior executives getting together to develop a strategic plan, and they do so right there and then, my guess is it’s not a strategic plan at all. It’s an operational plan. Your management team is most likely looking inside-out, and it surely doesn’t have all the answers. It probably hasn’t even asked the right questions.

Effective leaders listen. They observe. And they translate what they learn into strategy. Hubris has no place in outside-in thinking and effective strategy development. You have customers and other stakeholders who are dying to share their ideas about how you should change your company in ways that will make them even greater supporters. So empower them to do that.

Conduct interviews to understand your stakeholders’ needs. You want to hear, for example, how customers decided to buy from you or from the competition. You want to hear how employees committed to join your organization or decided to leave to work somewhere else, how suppliers agreed to enter into contracts to provide you with goods or services when they had a choice, how partners signed up to sponsor your events when there were plenty of others options on offer. You’re looking for insight into their “journey” with the organization, to put this in marketing terms. On the criteria that emerge from their stories, you want to know how your organization performs — and what suggestions people have for improving your competitiveness.

Each interview should take place soon after the customer’s shopping trip, the supplier’s experience with your company, and so on. Wait too long, and people will forget important details and convey only vague impressions.

Go beyond your current customers. Interview potential stakeholders, too. That includes customers and others who are currently dealing with your competitors — but also those who interact with neither you nor your rivals. In the wine industry, you would talk to people who don’t drink wine — beer and cocktail consumers, for example — in order to appreciate why they prefer these other beverages, understand fully any objections they might have to wine, develop ways to eliminate any barriers to purchase, and figure out how to appeal to them in order to disrupt their pattern of choice. This is how you glean insights into new areas of competitive advantage (also known as blue ocean opportunities).

Listening is important, but you also have to determine who to listen to — that is, work out who your key stakeholders are. That will help you adjust your company’s positions on the factors that matter.

To Innovate in a Big Company, Don’t Think “Us Against Them”

“This seems like pie-in-the-sky wishful thinking. Have you actually seen this done?”

I often hear this question when I visit companies and speak about how to make an innovative idea less terrifying to high level executives. The skepticism is warranted. There are plenty of pundits arguing that big companies need to innovate, and pointing out that it is difficult to do so. Far less often do we hear how it really comes together, especially inside a large organization.

But it does happen. Take the case of Janssen, the pharmaceuticals arm of Johnson & Johnson, which created a breakthrough innovative program called Immersion.

The idea started with two Janssen employees, Annick Daems and Enrique Esteban, who were spearheading an initiative to increase the company’s diversity of thought and experience. As part of this effort, they discovered that the majority of employees who were advising Janssen on emerging markets had never set foot in those countries. They also identified another problem common within large organizations: employees working in silos. Both of these problems seemed like great opportunities for their initiative. But that would require an ambitious new project.

They approached Adrian Thomas, head of Global Market Access and Global Public Health, about providing employees with in-country experiences working alongside colleagues from other silos within Janssen. Their proposal would solve a diversity and inclusion problem, but the impact on the company’s bottom line wasn’t clear. However, Thomas, a physician by training, realized that what Daems and Esteban were proposing could be a mechanism for finding scalable solutions to global health problems.

Under Thomas’ leadership, with critical support from senior leadership within the organization, including chairman of pharmaceutical global strategy Jaak Peeters, Immersion has become a global health program with a simple mandate: identify specific problems in specific locations, like Hepatitis C in Romania or aging in Poland. Then assemble small, cross-silo teams and get them in-country to find ways to better deliver healthcare access in that emerging market.

Three years in, Immersion’s projects are quietly gaining traction.

Daems and Esteban initiated what some would say is impossible: As individuals, they were able to innovate within a huge corporation. What were the secrets to the success of the Immersion project?

1. They overcame short-term thinking. A majority of public companies pledge allegiance to short-term profit over long-term vision. Call it an organization’s survival instinct. Managers, whose annual reviews hinge on quarterly gains, see no return on investing in what appear to be their employees’ pipe dream projects.

And yet management sponsorship is crucial for any ambitious initiative. Even highly motivated employees such as Daems and Esteban could not have overcome the drag of short-term thinking and made Immersion a reality without their advocates, Thomas and Peeters, in upper management. They were willing and had the authority to test the project, and they could persuade their peers to forego near-term profit for a potential long-term payoff.

2. They let go of conventional planning and productivity measures and embraced a discovery-driven process. In a large enterprise, the more checklists an enterprise can adhere to and the more codified its processes, the greater the productivity and the higher the margins. When implementing an innovative idea, this modus operandi must be abandoned in favor of a discovery-driven or emergent process. This often means each project will have its own trajectory. Some will start slowly, quietly building momentum, while others skyrocket, then crash.

With Immersion, an early obstacle for participants was the idea of starting from scratch: there were no templates and no assignments. If you were interested in a project, you could decide for yourself how you would tackle it. In some cases, even the projects themselves were amorphous at first. This freedom to explore ideas and try new things without pressure to produce immediate financial results was critical to creating projects that could yield long-term results. Such as a biomarker initiative, the development of a traceable substance that detects a specific disease, which is now underway. Not every project has been so successful, but Janssen understands that this doesn’t throw the validity of the whole initiative into question.

3. They cultivated a “we are them” mentality. Literature on innovation tends to frame the relationship between spry innovators and the staid status quo as a David versus Goliath battle, but the challenge for large organizations is to acknowledge that David and Goliath must work together rather than fight each other. Janssen knows that Immersion must cross silos (departments, regions, countries, and more), temporarily pulling people from one P&L to work on a project whose success may accrue to another P&L. Creating a spirit of internal cooperation and cohesion has been crucial.

Cultivating a “we are them” mentality is equally important in building external alliances. As Guy Nuyts launched an Immersion project to treat hepatitis C in Romania, he realized that achieving their goal of treating 80,000 people by the year 2020 would require the participation of a much larger group of stakeholders. The focus needed to shift away from selling medication to raising awareness, increasing screening, and treating patients. Says Nuyts: “The best part of Immersion is solving problems in a holistic way: there is no doubt that this is the future of healthcare.” In Romania, as Janssen has focused on long-term results rather than on short-term sales, they received an invitation from the Romanian Minister of Health to work together to eradicate Hepatitis C in Romania. Again, holistic thinking and a “we” mentality are paving the way for innovation.

Implementing innovative ideas is an exacting endeavor. But the payoffs can be huge in terms of creating value for the company and personal fulfillment for the employee. For many at Janssen, Immersion has become the best part of their work. The long view is tough by definition — because it’s long. But the question is not should you take the long view, but rather – how can you afford not to?

Do You Know Who Owns Analytics at Your Company?

At a corporate level, who has ultimate responsibility for analytics within your organization? The answers I most often get are “Nobody” or “I don’t know.” When I do get a name, it often differs depending on who I asked—a marketing executive points to one person, while finance identifies someone else. That isn’t good. How can analytics become a strategic, core component of an organization if there is no clear owner and leader for analytics at the corporate level?

As predictive analytics becomes more commonplace, companies are grappling with how to better organize and grow their analytics teams. Analytics requirements can span business units, database and analysis systems, and reporting hierarchies. Without someone in a position to navigate across that complex landscape, an organization will struggle to move beyond targeted analytics that addresses just one part of the business at a time. It is also impossible to maintain consistency and efficiency when independent groups all pursue analytics in their own way. Who will champion enterprise-level analysis as opposed to business unit–level analysis?

Today, most companies have multiple pockets of analytics professionals spread throughout the organization. Years ago, one group, often marketing, decided it needed analytics support and so that group hired some analytics professionals. Over time, other groups did the same. As a result, different parts of the organization have independently had success with analytics. However, those pockets are still often completely standalone and disjointed. When I meet with analytics professionals in an organization, I’ve seen analysts from different parts of an organization begin the session by introduce themselves to each other — because our meeting is the first time they’ve ever met. It is time to connect these groups, elevate analytics to a strategic corporate practice, and assign executive leadership to oversee it.

The title isn’t the important part—the role is. In some cases, it might be a Chief Analytics Officer (CAO) or a VP of Analytics. The point is that someone has to have corporate-level ownership of analytics and access to the C-suite to drive analytics initiatives and tie them to the right corporate priorities.

Where should the CAO report? In most cases today, the CAO doesn’t report directly to the CEO, but to another member of the C-suite. This, too, might change over time. However, the key is that the CAO has the support of, and access to, the C-suite to drive analytics deeper into and more broadly across the organization. But wherever he or she lands, the CAO should be viewed neutrally — a Switzerland of the executive suite. The CAO should be under an executive that naturally spans all of the business units that have analytical needs, such as the Chief Strategy Officer, the CFO, and the COO.

It is often easier to see where a CAO role should not report. For example, marketing analytics is quite important to many organizations. However, if the CAO reports to the CMO, then other business units such as product development or customer service might not feel that they get equitable treatment.

I am not suggesting that the CAO come in and consolidate all analytics professionals within one central team. I have written in the past that what works best is a hybrid organization with a small centralized team supporting the distributed, embedded teams. This is sometimes, but not always, called a Center of Excellence model. Leaving successful teams in place within the units where they currently sit is fine. The key is for the CAO and his or her corporate-level team to begin to provide extra support for the distributed teams, to ensure efficiency of spend and effort across the teams, to ensure the impact of analytics is being measured consistently, and to champion the cause for new, innovative analytics possibilities that are identified.

As predictive analytics specifically and analytics in general continue to permeate organizations and change how business is done, it is imperative to put the proper emphasis and leadership in place to ensure success. An analytics revolution is coming. Creating a role such as a CAO is one way to demonstrate a firm commitment to joining the revolution.

If you can’t say who owns analytics in your organization, I suggest you consider fixing that today.

CEOs Get Paid Too Much, According to Pretty Much Everyone in the World

Rumblings of discontent about executive wages, the 1%, and wealth gaps know no borders. And neither does fierce debate about income inequality in general. But until now, it’s been relatively unclear how much people think CEOs should really make compared to other workers on a global scale.

In their recent research, scheduled to be published in a forthcoming issue Perspectives on Psychological Science, Chulalongkorn University’s Sorapop Kiatpongsan and Harvard Business School’s Michael Norton investigate “what size gaps people desire” and whether those gaps are at all consistent among people from different countries and backgrounds.

It turns out that most people, regardless of nationality or set of beliefs, share similar sentiments about how much CEOs should be paid — and, for the most part, these estimates are markedly lower than the amounts company leaders actually earn.

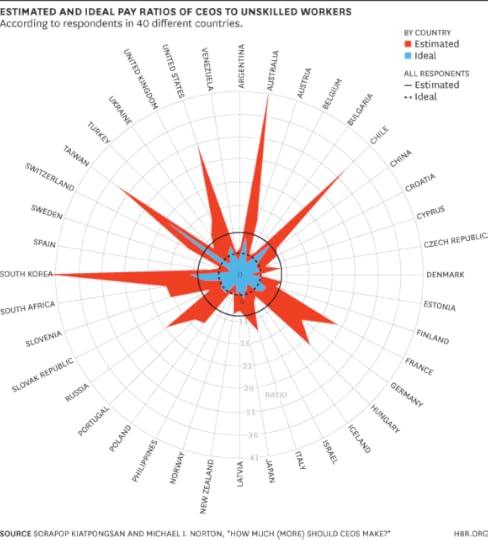

Using data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) from December 2012, in which respondents were asked to both “estimate how much a chairman of a national company (CEO), a cabinet minister in a national government, and an unskilled factory worker actually earn” and how much each person should earn, the researchers calculated the median ratios for the full sample and for 40 countries separately.

For the countries combined, the ideal pay ratio for CEOs to unskilled workers was 4.6 to 1; the estimated ratio was about double, at 10 to 1. But there were some differences country to country. People in Denmark, for example, estimated the ratio to be 3.7 to 1, with an ideal ratio being 2 to 1. In South Korea, the estimated gap was much larger at 41.7 to 1. The ideal gap in Taiwan was particularly high, at 20 to 1. This is what the breakdown looks like, country by country:

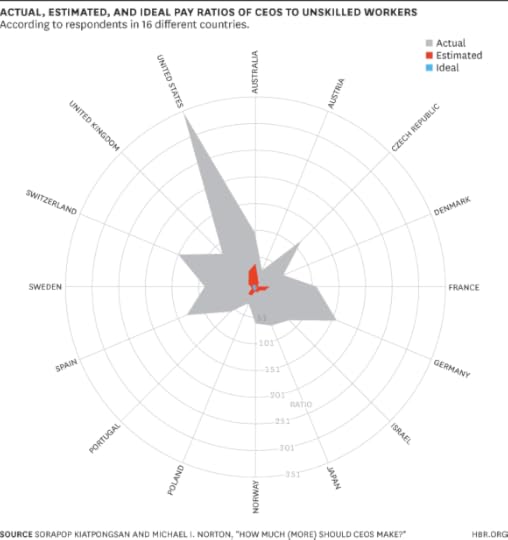

And how does this compare with how much CEOs really earn? Here’s the data for 16 countries where the data is available; as Kiatpongsan and Norton note, it “includes the estimated and ideal data from [the other chart], but both are so much smaller than the actual pay ratios that they are nearly invisible”:

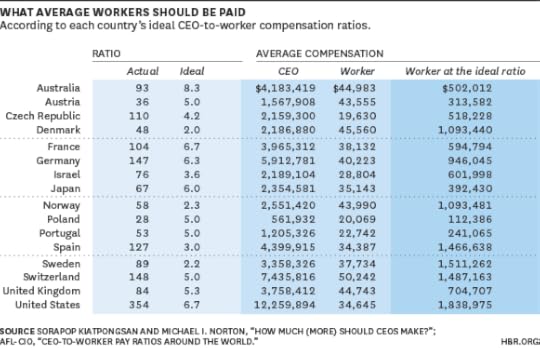

My colleague Walter Frick and I calculated the ideal wages for average workers if CEO compensation remained the same, based on the same 2012 average CEO pay data used by the researchers. Even workers in the country with the largest desired ratio difference (Australia at 8.3 to 1) would be hypothetically making over $500,000 a year, while those in countries that emphasized the need for a smaller gap (Denmark, Sweden, and Norway at around 2 to 1) would earn over a million (note: the ISSP and AFL-CIO numbers do not align perfectly, so there is a slight difference between the wages of unskilled and average workers):

Taken together, these numbers say a lot, even if the latter chart isn’t exactly based on real life. Importantly, though, it’s not just the starkness of the data that’s striking — it’s the thinking behind them. While the estimated pay ratios Kiatpongsan and Norton found did differ based on, say, political leanings, the ideal pay ratios were similar across the board:

Note, for example, that respondents who “strongly agreed” that differences in income were too large estimated a much larger pay gap between CEOs and unskilled workers (12.5:1) than respondents who “strongly disagreed” (6.7:1; Table 2). Yet, the ideal ratios for both groups were strikingly similar (4.7:1 and 4.8:1), suggesting that whether people agree or disagree that current pay gaps are too large, they agree that ideal gaps should be smaller.

When it comes to other beliefs — ranging from the importance of working hard or having a lot of job responsibility — differences among people didn’t result in major shifts in how much CEOs should get paid, either.

“My coauthor and I were most surprised by the extraordinary consensus across the many different countries in the survey,” Norton says. “Despite enormous differences in culture, income, religion, and other factors, respondents in every country surveyed showed a universal desire for smaller gaps in pay between the rich and poor than the current level in their countries.”

We’re currently far past the late Peter Drucker’s warning that any CEO-to-worker ratio larger than 20:1 would “increase employee resentment and decrease morale.” Twenty years ago it had already hit 40 to 1, and it was around 400 to 1 at the time of his death in 2005. But this new research makes clear that, one, it’s mindbogglingly difficult for ordinary people to even guess at the actual differences between the top and the bottom; and, two, most are in agreement on what that difference should be.

“The lack of awareness of the gap in CEO to unskilled worker pay — which in the U.S. people estimate to be 30 to 1 but is in fact 350 to 1 — likely reduces citizens’ desire to take action to decrease that gap,” says Norton. Though he notes some movement on that front, including an unsuccessful vote in Switzerland to cap the ratio at 12 to 1 in 2013 and recent protests by fast food workers in the U.S.

He also emphasizes that “many of the heated debates about whether CEO pay should be capped or the minimum wage increased are debates based on an extreme lack of knowledge about the true state of affairs. In other words, both liberals and conservatives fail to accurately estimate the actual current gaps in our pay. Our hope is that presenting the data to all sides might force people to examine their assumptions about whether some people are making more than they would like, and others less.”

Give Your Unsung Office Heroes a Raise

The single most important thing you do at work is interact with other people. That’s the key insight from Workspaces that Move People, the HBR feature I co-wrote with Greg Lindsay and Jennifer Magnolfi.

If it sounds like unprovable generic wisdom, academic puffery, it’s not. We have data, collected from workers who wear sensors that measure how people talk to one another, who talks with whom, how people move around the office, and where they spend time. Consistently the data shows that what we call “collisions” — chance encounters and unplanned interactions between knowledge workers, both inside and outside the organization — is what improves performance. We’ve engineered spaces to increase collisions and watched performance follow, whether it’s bumps in productivity or even raw jumps in sales. It’s important to note that we don’t collect data on the content of interactions. It’s the act of mingling itself that seems to goose performance.

This may strike some as just wrong. Americans, especially, like to think about productivity in terms of the individual. We measure performance based on contributions like lines of code, number of widgets produced, tasks completed, or answered e-mails. The idea that being away from your desk — your work! — is not only good, but the best thing you can do with your time seems strange.

It shouldn’t. Let’s play it out with a simple hypothetical example. Suppose you figure out a new way to do something at work, saving you 4 hours per week. Over a year, you’ll save 208 hours.

Now imagine you spent 10 hours teaching your work hack to 10 of your colleagues. At the end of the year your productivity increase would be about 5 percent lower: you’d only save 198 hours. But your 10 colleagues would save a total of 2080 hours. So if you hacked your work and kept a laser focus on your individual productivity, and don’t get up from your desk to teach others, you’ve lost an opportunity at gaining back 1,882 hours for the company.

Obviously, it’s better to get up and talk to others about your hack. But that’s a hypothetical; does this happen in the real world?

Yes, it appears it does. Here’s an example: In one of our projects, we studied an IT firm that configures multi-million dollar server systems. Employees were paid based on how quickly they configured systems, which took them 5 minutes to 8 hours per task. Using the wearable sensors central to our work, we measured who spoke with whom using and captured the exact start and end times of their tasks.

Our analysis revealed certain people whom almost everyone ended up speaking with during a task. After talking with this informal expert, people completed a task in about a third of their normal time. They were getting tips on how to complete their task.

Over the course of a month, the informal experts’ ability to interact with others helped the team save approximately 265 hours of work. But here’s the key: because they were helping others, these informal experts’ individual productivity was statistically average, thus they were paid less than the people they were helping, since pay was based on individual productivity.

Organizationally, this makes no sense. The company incentives were set up to limit group productivity by making everyone focus on individual productivity. Those who brought the most value — the informal experts — were penalized with lower pay for helping the team perform better.

Unfortunately this is all too common. Workers feel pressure to focus on themselves and their own productivity because that’s how they’re judged and ultimately rewarded. Individually-focused incentives make us lose sight of the larger picture: working together towards common goals requires, above all, communication. So why aren’t we recognizing and rewarding communication?

The best way to start to change is to restructure financial incentives to reward that behavior and create bonuses based on group targets, encourage people to share information and work together to help the entire company succeed.

However, we can’t view these incentives in a vacuum. They simply won’t work in companies that culturally discourage sharing and communication. If bosses are chewing out their employees for taking a long lunch break, incentives won’t work. If companies don’t promote people who are great enablers, instead focusing on individual performers, incentives won’t work. Companies have to build sharing, relationships, and communication into their DNA.

So encourage people to eat lunch out with a colleague, take coffee breaks together, and sit with each other during work hours. Socializing at work shouldn’t just be acceptable, it should be expected. The whole reason we’re in companies, after all, is because we can do things together that we can’t do alone. Helping your colleagues needs to be the norm. That’s the only way we’ll succeed as individuals.

Immigrants’ Willingness to Trust Is Affected By Where Their Mothers Were Born

Immigrants to Europe whose mothers were born in countries with higher levels of interpersonal trust are themselves more likely to show greater trust, says Martin Ljunge of the Research Institute of Industrial Economics in Sweden (fathers’ birth origins are less important). A 1-standard-deviation increase in the trust level in the mother’s country corresponds to an individual having higher trust by an amount equivalent to half the effect of having an upper secondary degree. Although researchers view high-trust individuals — those who believe “most people can be trusted” — as more likely to get cheated and to have lower incomes, a higher overall trust level in a society appears to promote economic success, adoption of information technology, and physical health.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers

![venturecapitalists[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1411603393i/11254468._SX540_.png)