Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1357

October 2, 2014

Technology Questions Every CMO Must Ask

Marketers today encounter a mind-boggling array of technologies. CMOs I talk to are swamped by meeting requests from technology vendors, and most feel an acute pressure to climb on the tech bandwagon. But they worry about the massive distraction of full-scale technology assessments—and about the risk of buying expensive tools that don’t live up to their potential.

My colleagues and I believe CMOs can make better technology sourcing decisions by asking five fundamental questions. The first two focus on avoiding the all-too-common trap of treating each technology decision in isolation.

1. Will the technology advance a critical marketing priority? This seems like an obvious consideration, but we often see the technology tail wagging the marketing dog. Plenty of the new tools have the potential to add value in an absolute sense, which is why they appear on CMOs’ radar screens in the first place. But the real question is how much value the tool under evaluation adds relative to other possibilities.

Marketers who ask this question make individual technology assessments in the context of the overall marketing priorities that a given tool will address. It’s hardly rocket science. But this common-sense discipline often falls victim to a combination of poor planning and siloed decision-making—for example, when individual marketing teams independently make narrow, channel-specific technology choices without accounting for interdependencies and appropriate sequencing.

2. Will the tool add balance to the marketing technology portfolio? It’s useful to categorize marketing technologies into three buckets. The first helps a company deliver more personalized marketing content and experiences to customers and prospects (especially through digital media). The second allows marketers to use data and analytics to reach better decisions. The third improves the effectiveness and efficiency of core marketing workflows. These buckets are interlinked. For example, marketing automation technology helps deliver personalized content and offers to large numbers of individual customers on a scale that would be unfeasible using traditional manual processes.

Over time, marketers should strive to build a technology portfolio that is balanced across the three buckets. So any individual technology assessment needs to account for how a given tool fits into the architecture of the overall portfolio.

In many ways, acquiring a new technology is the easy part. The harder part is getting people to use it—which raises three additional questions.

3. Is the organization culturally ready to adopt the new technology? Like technologies elsewhere, marketing technologies can unsettle long-held views and ways of working. Changing these attitudes and behaviors requires a multi-pronged approach: championing by senior leadership, evangelism by believers on the marketing front line, and active involvement of middle managers in encouraging the change. This “sponsorship spine” is at the core of effective change management and raises the odds of disciplined, deliberate adoption. Success requires identifying desired adoption behaviors, anticipating resistance and challenges, and having a deliberate mitigation plan — all before acquiring a new technology.

4. How readily can current marketing workflows integrate the new technology? To take one example: a number of new technologies can improve the analytic power of marketing test-and-learn processes. But many marketers still treat test-and-learn as an adjunct to their main creative and campaign-management workflows. If test-and-learn remains a sideshow, the impact of these new technologies on marketing outcomes will necessarily be limited. It’s only when core marketing processes are overhauled to integrate ongoing testing and iteration (so-called agile marketing) that the value of the new technologies will be realized.

5. Do potential users have the skills they need to benefit fully from the technology? Even when marketers are excited about a new tool, they may lack the skills and capabilities to use it. While most vendors do provide training and support, it may be inadequate to an organization’s needs. Additional training and other support—even new hires—may be required to bridge the capability gaps. Hence, the technology assessment needs to include a plan (and a budget) for whatever additional training and capability investments are needed.

Questions like these are part of the playbook of technology buyers in other parts of the enterprise, who have been adopting new technologies for more than two decades. Marketing is a relative newcomer to this game, which is why so many CMOs feel overwhelmed. The good news is that a well-planned technology diligence process—a process that anchors individual decisions in a larger context and focuses on creating the right environment in terms of sponsorship, process changes, and capabilities—can significantly improve the odds that marketing’s many new technologies will deliver on their promise.

When a Simple Rule of Thumb Beats a Fancy Algorithm

For a retailer, it’s extremely useful to know whether a customer will be back or has abandoned you for good. Starting in the late 1980s, academic researchers began to develop sophisticated predictive techniques to answer that question. The best-known is the Pareto/NBD (for negative binomial distribution) model, which takes a customer’s order history and sometimes other data points, then simulates whether and how much she will buy again.

Actual retailers, though, have tended to stick with simpler techniques, such as simply looking at how long it has been since a customer last bought anything, and picking a cutoff period (nine months, say) after which that customer is considered inactive.

This resistance to state-of-the-art statistical models has frustrated the academics. So, a decade ago, marketing professor Florian von Wangenheim (now at the ETH Zurich technical university in Switzerland) and his then-student Markus Wübben (now an executive at a tech incubator in Berlin) set out, in Wangenheim’s words, to “convince companies to use these models.”

To do this, Wübben and Wangenheim tested the predictive accuracy of Pareto/NBD and the related BG/NBD model against simpler methods like the “hiatus heuristic” — the academic term for looking at how long it’s been since a customer last bought anything — using data from an apparel retailer, a global airline, and the online CD retailer CDNow (from before it was acquired by Amazon in 2001). What they found surprised them. As they reported in a paper published in 2008, rule-of-thumb methods were generally as good or even slightly better at predicting individual customer behavior than sophisticated models.

This result wasn’t a fluke. “I’ve seen much more research in this area, many variables have been added to these models,” says Wangenheim. “The performance is slightly better, but it’s still not much.”

One way to look at this is that it’s just a matter of time. Sure, human beings, with “their limited computational abilities and their incomplete information,” as the great social scientist Herbert Simon put it, need to rely on the mental shortcuts and rules of thumb known as heuristics. But as the amount of data that retailers are able to collect grows and the predictive models keep improving, the models will inevitably become markedly better at predicting customer behavior than simple rules. Even Simon acknowledged that, as computers became more powerful and predictive models more sophisticated, heuristics might lose ground in business.

But there’s at least a possibility that, for some predictive tasks at least, less information will continue to be better than more. Gerd Gigerenzer, director at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, has been making the case for decades that heuristics often outperform statistical models. Lately he and others have been trying to define when exactly such outperformance is most likely to occur. This work is still ongoing, but in 2011 Gigerenzer and his colleague Wolfgang Gassmaier wrote that heuristics are likely to do well in an environment with moderate to high uncertainty and moderate to high redundancy (that is, the different data series available are correlated with each another).

Citing the Wübben/Wangenheim findings, Gigerenzer and Gassmaier (why so many of the people involved in this research are German is a question for another day), posited that there’s a lot of uncertainty over if and when a customer will buy again, while the time since last purchase tends to be closely correlated with every other available metric of past customer behavior. Ergo: heuristics win.

There are other areas where the heuristic advantage might be even greater. Financial markets are rife with uncertainty and correlation — and the correlations are strongest when the uncertainty is greatest (think of the parallel downward trajectories of lots of different asset classes during the financial crisis of 2008). Sure enough, while sophisticated financial models performed poorly during the recent financial crisis, simple market heuristics (buying stocks with low price-to-book-value ratios, for example) have withstood the test of time. Along those lines, Gigerenzer has been working with the Bank of England to come up with simpler rules for forecasting and regulating financial markets.

“In general, if you are in an uncertain world, make it simple,” Gigerenzer said when I interviewed him earlier this year. “If you are in a world that’s highly predictable, make it complex.” In other words, your fancy predictive analytics are probably going to work best on things that are already pretty predictable.

Does Your Sales Team Know Your Strategy?

Frank Cespedes, HBS professor and author of Aligning Strategy and Sales, explains how to get the front line on board. For more, read his article, Putting Sales at the Center of Strategy.

Fighting Ebola Means Managing Fear

The worst-ever outbreak of Ebola — a hemorrhagic fever that has in the past killed nine out of 10 people that contract it — is raging through the West African countries of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, with consequences so dire that the Liberian Minister of Defense characterized it as “… spreading like wildfire, devouring everything in its path.”

In this so-called Hot Zone, a term made famous by the 1994 book, more than 2,000 Africans of all ages and from various socioeconomic backgrounds have already died, and the World Health Organization estimates that as many as 20,000 fatalities might occur before the epidemic is contained. Both the U.S. Center for Disease Control’s head, Tom Frieden, and the operations director of Doctors without Borders, Bart Janssens, have described the situation as “out of control.”

One reason why it has been so difficult to tackle the Ebola crisis is fear, which prevents healthcare workers from grappling effectively with the situation. Fear can hobble an organization; for instance, recent research shows that at Nokia, fear led to paralysis, isolating the headquarters from the marketplace and rendering it unable to respond to a fast-changing situation.

The younger of us, a pulmonary and critical care physician, just returned from the Ebola outbreak’s epicenter in Guinea, where he was deployed by WHO to treat victims of the disease. The elder, a management teacher, studies how organizations react under conditions of uncertainty and fear.

We recently compared notes, and identified four practices seen in the fight against Ebola that have been particularly effective in managing uncertainty and fear.

Contain fear by engaging with the problem first-hand. Fear can be debilitating and contagious, so the root problem usually keeps growing, assisted by organizational hesitancy. Good practices remain undiscovered because of a reluctance to engage first-hand with the challenges.

During earlier Ebola outbreaks, healthcare workers often wouldn’t administer intravenous fluids for fear that if they accidentally pricked themselves, they would be condemned to the same fate as their patients. Over time, healthcare workers realized that inadvertent needle sticks more commonly occur while placing plastic covers on needles. That led to the creation of simple protocols that now allow them to treat patients with intravenous fluids while protecting themselves.

Use structured approaches. Processes may seem to be pedestrian responses to crises, but they become sources of comfort in situations where uncertainty and fear prevail. The task of learning more about Ebola is complicated by the fear of becoming exposed to the infectious bodily fluids of patients. The first line of protection is personal protective equipment, spacesuit-like garments that reduce the risk of infection by covering every inch of the caregiver’s skin. Still, the death of several healthcare workers during the current epidemic is a reminder that PPE suits aren’t always enough.

The risk of exposure is highest when medical workers remove their PPE suits. At the treatment sites administered by Doctors Without Borders, relying consistently on protocols for donning (putting on) and doffing (removing) protective clothing has resulted in a greater feeling of security. By insisting on those routines, a major element of fear has been reduced, sparing healthcare workers one major thing to worry about.

Flexibility must complement routines. We have to stay flexible in changing and competitive situations. The World Health Organization’s decision to send critical care physicians to Guinea — the first time it has ever done so — stemmed from the recognition that a large, fast-changing, and uncertain epidemic cannot be controlled by routines alone; it’s also necessary to learn quickly. Placing critical care physicians on the front lines ensured a better understanding of the illness.

These specialists learned what was needed by way of care by staying in direct contact with patients. By mixing process-controlled treatment with direct contact that fostered quick learning, the mortality rate was brought down from the historical 90% to an estimated 40%-50% even before antiviral medications became available.

Resource-constrained environments demand unique perspectives and responses. Relying on unconventional perspectives in business helps our ability to flex and break out of the status quo. The lack of state-of-the-art technologies in West Africa’s treatment centers has forced physicians to rely on their basic senses for diagnosis, and the resource-constrained environment has also forced healthcare workers to take on multiple roles, as both nurses and doctors.

These dual roles expand experts’ awareness of the entire process of patient care, allowing them to think about tackling the cycle of Ebola contagion in different ways. That only works, though, when doctors are flexible and agree to play non-traditional roles.

Fighting fear is tough. But as the global campaign against the Ebola pandemic has shown, both process and innovation have been part of what has allowed for progress in this crisis.

How We’ll Stereotype Our Robot Coworkers

Robots are coming to the workplace, including in seemingly social roles such as receptionist, shopping assistant, waiter, bellhop, and personal assistant. If you have a chance to visit Kita-Kyushu airport in Japan, you can see a robot receptionist shaped after a famous Japanese animation character in Galaxy Express 999. It cannot fully replace the human receptionist, but plays a supporting role for answering simple requests and questions. Likewise, there is a high chance that you will have a robot companion in your workplace in the near future, raising the issue of human-robot relationships in the office.

In social relationships, including those that form at work, non-task related characteristics such as personality play an important role. The same thing is true for human-robot interactions, since humans perceive robots as social actors. The challenge for robot designers, then, is to build robots with personality. This sort of anthropomorphic design of social robots is already commonly accepted all over the world.

But what kind of personality should a robot have? What sort of robot do you want to have as a colleague at your workplace? Do some robots need to be stern, while others are friendly? Should robots take breaks to socialize around the water cooler?

My research has emphasized the role of stereotypes in human-robot interactions. In my experiment, participants rated security robots with stereotypically male names and voices as more useful than female ones. Previous research by others has found that the public prefers female-gendered robots working in home settings.

This raises a number of questions for social robots in the workplace. When is it appropriate for robots to be designed to play to our expectations, and when does doing so promote harmful stereotypes? Certainly men can perform housework and women can be great security guards; in these cases, designing robots to meet users’ expectations could serve to further cement gender biases.

In cases where workers have fewer expectations – say, new roles around the office that are only possible with a robot – the story only becomes more complicated. Social psychology relies on models of attraction based on both similarity and complementarity.

To understand what that means, consider interpersonal relationships: you may think a person is attractive because you share common characteristics, such as, attitude and personality. On the other hand, you may fall in love with a person who exhibits characteristics that you wish you had. In some cases, two introverts may be attracted; in others, an introverted person who wants to be more extroverted may be attracted to extroverts. If we apply these two competing theories to the relationship between human and robot, new questions pop up. Should a robot colleague be loaded with a personality similar to the members of its team? Or should it have a markedly different one, to round out the group?

As any manager knows, personality conflict can undermine a team’s success, so these are not idle questions.

Human-robot relationships are not the same as interpersonal relationships, but we may see some parallels in how human can develop relationship with artificial agents. Human relationships evolve as time passes. Eventually, we will see the same thing with human-robot relationships, as shown in the movies Robot and Frank. But between now and then, lots of decisions must be made about what sort of personalities we want robots to have. In making them, we’re likely to learn as much about ourselves as we are about robots.

Apple: Luxury Brand or Mass Marketer?

It’s easy to make a case that Apple is now positioning itself to become more of a provider of luxury-level technology. Between recent high-profile hires from the fashion and watch industries to the rumored 18-karat gold Apple Watch, some observers are fretting about the company’s trend toward catering to the highly profitable 1%, possibly at the expense of the rest of us.

Tech blogger John Gruber and The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer both expressed concern recently about Apple abandoning middle class roots. Meyer writes:

So far, Apple has been a company focused on the mainstream, on the mass consumer, in an era where the most reliable profits could be found in the luxury market. Apple has catered to, if not the poorest quartile of American society, then the thing we used to call a middle class.

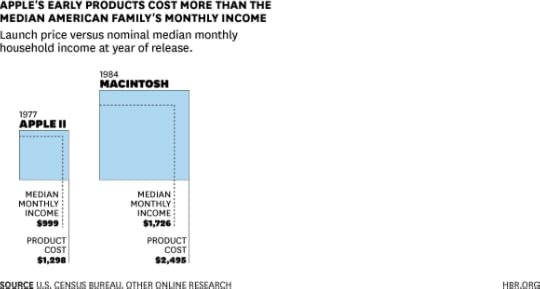

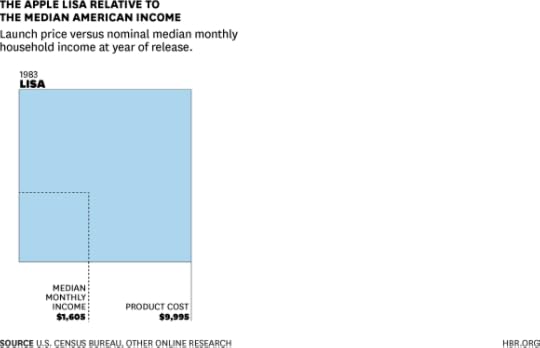

But is that really right? To understand the cost of Apple products that we associate with mass market success, we mapped the U.S. introductory prices of some Apple products against figures for median monthly household income during the year each product was introduced. (Income data is from the U.S. Census and device cost is from online research). Let’s start with two early landmark products:

Early Apple products required much more — 45% more in the case of the Macintosh — than the median household’s monthly earnings. Forget the poorest quartile of American society; a computer that cost about a third of a car is hardly aimed at the middle class. But that’s not just a function of the company’s focus on upscale, high-margin hardware; it’s the story of the price of computing and a historical look at Moore’s Law.

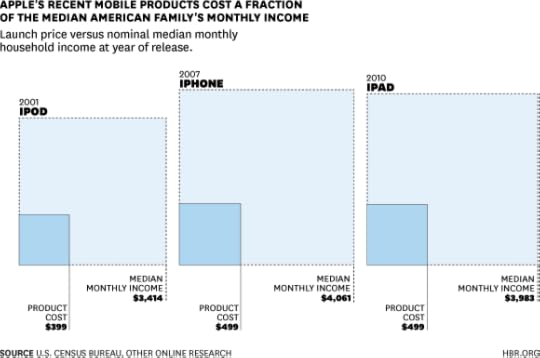

Since those early days, did Apple’s products become more available to the middle class? Yes:

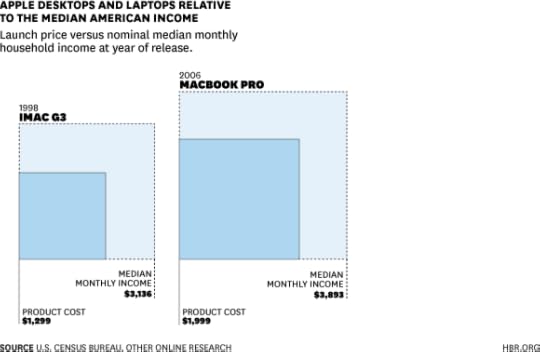

And no:

The mobile devices above all are what brought Apple closer to the middle class. At launch, they cost about 10-12% of median monthly income, far less than desktops (40%) and notebooks (50%) of the same general era. Apple’s current product line (we used 2013 income, the most recent available), is even more affordable: The iPhone 6 will eat up less than 5% of monthly median household income, while the 6+ will take up less than 7%. Computers have come down, too: iMacs will run 25% of median monthly household income and MacBooks 30%.

That certainly feels more like a middle class play — beautiful things for everyone — but even these numbers don’t quite reflect reality. First, our costs only account for getting base models out of the store. They don’t include the cost of upgrades such as more memory or bigger screens, and they don’t include ongoing costs like software, or data, or media, or apps, which in a year can easily double a device’s acquisition cost. For example, the base model iPhone 6+ consumes 7% of the monthly median income. Upgrade that to the high-end model, and add a year’s worth of $50/month data and $50 of apps and music and the cost jumps to 27% — still much better than an original Mac, but not cheap. A maxed out MacBook quickly scales past 50% of of median monthly income, too.

Second, despite the fact these are still relatively expensive gadgets, they may feel more affordable, because our appetite for debt is much more voracious now. Today, you can walk into an Apple Store, sign up for a credit card and pick a product now, something that was close to impossible even in the 1990s.

We also can’t visualize qualitative value. It could be that people believe a MacBook Pro is worth it, even if it’s a financial stressor to acquire one.

But for evaluating the raw cost of the transaction compared to middle class wealth, this is a simple and reasonable way to see how Apple stacks up offering egalitarian products, and it turns out, the idea that Apple makes products for the masses is at best only recently true, and that’s still probably a stretch.

In fact, going back as far as 2009, watchers have documented how Apple has struggled to reach mass markets, like India’s. Then, iPhones were “priced far beyond the reach of even many middle-class Indian consumers.” That struggle hadn’t improved much as recently as last year, when Apple still hadn’t cracked the top 5 smartphone vendors in the country. In China, the black market is showing how the phones aren’t priced to crack the middle class market there, either: A New York Times article notes a “glum” sign, that smugglers are slashing prices on their black market phones because demand is “drying up” even before the devices officially go on sale in the country, noting that “the iPhone is simply one option among many, as local companies like Xiaomi and Meizu Technology rival Apple in terms of coolness while charging less than half the price.”

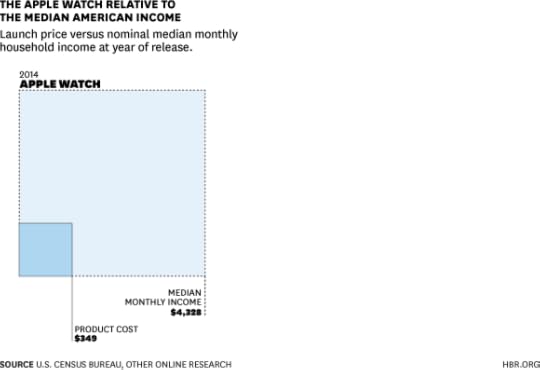

As for Apple Watch, the impetus for much of the concern over Apple’s supposed shift away from the middle class, its affordability falls in line with the other mobile devices, with base models setting you back just over 9% of a median household’s monthly income:

But remember that Watch is pretty much tethered to the iPhone; as a package the percentage will go up — a base model iPhone plus base model Watch plus data and apps will cost about 28% of median monthly household income.

Still, think of this: Even if that gold Apple watch does debut at $4,999, as Gruber fears, that’s 115% of monthly median household income. In other words, what we’re calling an anti-egalitarian luxury item won’t be as expensive as the Apple II or the Macintosh were when they debuted. That doesn’t make the gold watch more egalitarian. It makes the original Mac, like many Apple devices after it, an extremely luxurious product never intended for the middle class.

If change is happening at Apple, it doesn’t seem like it’s moving from egalitarian provider of mass market tech to gadgets for the wealthy. Rather, Apple seems like it’s moving from high-end electronics company to something more like a luxury fashion brand, moving away from focusing on user experience and magnificent industrial engineering as driving forces, and moving toward a company that offers trendiness, status, and individuality first, then nailing down the mechanics of the things. (Bendgate, anyone?) If that’s true, the almighty “experience” is going to have to change because the person looking for an expensive watch, as Gruber has noted, cares first, and more, about how it looks and what it says about them, not what apps they can get for it. “It just works” may give way to “it just looks great.” In this vein, it will be interesting to watch how Apple Stores evolve under former Burberry CEO Angela Ahrendts’s watch. Will Geniuses be replaced with trend-setting fashion consultants?

Finally, for fun, we couldn’t resist adding one more chart. This one represents the cost of the Apple Lisa, a Macintosh precursor and a project that Steve Jobs was kicked off of:

If you had about seven months of the median household’s earnings in 1983 sitting around, you could have had a Lisa.

Why Your Team Needs Rookies

Hiring managers often view newcomers to their organizations as not only long-term assets but also short-term burdens: people who need to be inducted, trained, and given lighter loads as they get up to speed, inevitably slowing everyone else down.

But that doesn’t have to be the case. In my research studying how inexperienced people tackle tough challenges, I’ve consistently found that rookies (whether they are freshly minted university graduates or experienced professionals coming from other organizations or functions) are surprisingly strong performers.

Because they face significant knowledge or skill gaps, they are alert, move fast, and work smart. While they’re not well-suited for tasks that require technical mastery or where a single mistake is game-ending, they are particularly adept at knowledge work that is innovative in nature, when speed matters and the environment is quickly changing. Consider science and technology, fields in which information is doubling every nine months and decaying at a rate of 30% a year, thereby rendering as much as 85% of a person’s technical knowledge irrelevant in five years’ time. For many professionals today, the ability to learn is more valuable than accumulated knowledge.

Our study found three things rookies are especially good at:

1. Tapping networks of experts. Having little knowledge and insight themselves, newcomers have no qualms about seeking guidance from others. Our study found that rookies are four times more likely to ask for help and 50% more likely to listen. They seek expertise 40% more than their experienced peers, and when they do, they connect with five times as many people.

Take Jeff, an IT manager at the financial services firm Vanguard. When he was abruptly put in charge of vendor management, an area in which he had no experience, he felt completely out of his element. But his response was to systematically reach out to 25 people with deep experience in the field, and within a few weeks, he had built a big network of experts to tap for advice.

If you want access to more knowledge, consider putting a rookie on the job and telling her it’s OK not to have all the answers herself. With one expert, you’ll get one expert; with a newcomer, you get access to many more.

2. Forging new territory. Clueless about whether a new idea or opportunity is impossible (or just plain hard) to achieve, rookies readily explore new frontiers. With added pressure to succeed and nowhere to retreat to, they are also more likely to improvise, get resourceful, and focus on meeting basic needs to push their long-shot projects through.

For example, at Reputation.com, CEO Michael Fertik never tells new business development staff how to start the sales process or size deals. “In absence of knowing, they often just start the conversation at the top of the organization [and] many of them end up bringing in far greater-sized deals than the experienced staff does,” he explains.

If you want someone to tackle a tough challenge or seize an unheard of opportunity, a rookie might be your best bet.

3. Accelerating innovation. Newcomers face a steeper learning curve, but, because they’re mindful of the gap and want to gain ground, they often deliver results faster. In our comparative study, rookies scored 60% higher than experienced colleagues on the timeliness of their output. They’re cautious at first as they gather data and study a situation, but once they jump in, they move quickly, making them perfectly suited for lean and agile development projects.

When eBay revamped its induction program to ensure that new hires weren’t just learning about the company but also immediately contributing to it, the results were impressive. Once directed to jump in and share their ideas without holding back, the 2013 college recruits submitted an average of 25% more ideas for patents, and more that led to formal submissions, in their first few months of work than the rest of the company.

Use your rookie talent to generate fresh ideas, experiment, deliver quick functionality, and get rapid feedback from your customers.

Rookies are far more capable than most people expect. Instead of putting them through basic training, ask them to make a difference right away. They don’t necessarily need more management; they need to be put in the game, pointed in the right direction, and given permission to play.

One final note: Anyone can display what I call “rookie smarts.” The real game-changer is ensuring that your entire team is able and willing to adopt the newcomer’s mindset when necessary—mobilizing experts, forging new territory and accelerating innovation – no matter their age or career stage.

Wind Turbines Could Take the Punch Out of Hurricanes

If 78,000 giant wind turbines had been positioned off the coast of New Orleans in 2005, they not only could have provided a lot of electrical power, they also would have sucked so much energy out of Hurricane Katrina that the storm surge would have been cut by 71% and wind speeds would have been reduced by as much as 57%, according to a Wall Street Journal report of a study that relied on computer modeling. Large arrays of offshore wind turbines, although expensive to build, could take enough energy out of the wind to break the “feedback loop” of wind speed and wave heights that makes hurricanes so destructive, the scientists say.

5 Ways to Work from Home More Effectively

More people are foregoing a lengthy commute and working from home. Whether you are a full-time freelancer or the occasional telecommuter, working outside an office can be a challenge. What are the best ways to set yourself up for success? How do you stay focused and productive? And how do you keep your work life separate from your home life?

What the Experts Say

The days when working from home conjured an image of a slacker in pajamas are rapidly disappearing. Technological advances and employers looking to lower costs have resulted in more people working outside an office than ever before. By one estimate, telecommuting increased in the U.S. by 80% between 2005 and 2012. “The obvious benefits for workers include flexibility, autonomy, and the comfort of working in your own space,” says Ned Hallowell, author of the forthcoming Driven to Distraction at Work. And done well, working from home can mean a marked increase in output. A Stanford University study last year found that the productivity of employees who worked from home was 13% higher than their office-bound colleagues. People often feel they make more progress when working from home, says Steven Kramer, a psychologist and author of The Progress Principle, and “of all the things that can boost people’s work life, the single most important is simply making progress on meaningful work.” Here’s how to work from home effectively.

Maintain a regular schedule

“Without supervision, even the most conscientious of us can slack off,” says Hallowell. Setting a schedule not only provides structure to the day, it also helps you stay motivated. Start the day as you would if you worked in an office: Get up early, get dressed, and try to avoid online distractions once you sit down to work. Whether you just started working at home or you’ve been doing it for months or years, take a few weeks to determine the best rhythm for your day. Then set realistic expectations for what you can accomplish on a daily basis. “Make a schedule and stick to it,” says Kramer. Make sure you give yourself permission to have downtime. If you have to work extra hours on a project, give yourself some extra free time later on to compensate.

Set clear boundaries

When you work at home, it’s easy to let your work life blur into your home life. “Unless you are careful to maintain boundaries, you may start to feel you’re always at work and lose a place to come home to,” Hallowell says. That’s why it’s important to keep the two distinct. One way to do that is to set aside a separate space in your home for work. You also want to make sure your friends and loved ones understand that even though you are at home, you are off limits during your scheduled work hours. “If the doorbell rings, unless I’m really expecting something, I’ll ignore it,” says Kramer. That not only helps you stay focused, but makes it easier to get out of work mode at the end of the day. “Schedule your time with your family, and with yourself,” says Kramer. “Put those on your daily calendar as seriously as you would your work.” And don’t worry about stopping for the day if you’re on a roll with a project. Pausing in the middle of something will make it easier to jump into the task the next day — a tip that is valid for everyone, but especially those working from home. “Ernest Hemingway would try to leave the middle of a paragraph at the end of the day,” says Kramer, “so when he sat down again, getting started wasn’t hard because he knew where it was going.”

Take regular breaks

It may be tempting to work flat out, especially if you’re trying to prove that you’re productive at home. But it’s vital to “take regular ‘brain breaks,’” says Hallowell. How often is best? Researchers at a social media company recently tracked the habits of their most productive employees. They discovered that the best workers typically worked intently for around 52 minutes and then took a 17-minute break. And these restorative breaks needn’t take any particular form. “It can be as simple as staring out the window or reading the newspaper,” says Hallowell, anything to give your brain an opportunity to briefly recuperate. “The brain is like any other muscle. It needs to rest,” says Kramer. “Go for a walk, get some exercise, stretch. Then get back to work.”

Stay connected

Prolonged isolation can lead to weakened productivity and motivation. So if you don’t have a job that requires face-time with others on a daily basis, you need to put in the extra effort to stay connected. Make a point of scheduling regular coffees and meetings with colleagues, clients, and work peers. Get involved with professional organizations. And use online networking sites like LinkedIn to maintain connections with far-flung contacts. Since visibility can be an important factor in who gets promoted (or scapegoated) back at the office, check in as often as you can with colleagues and superiors. “Tell people what you’re doing,” says Kramer. Share some of the tasks you’ve accomplished that day. “It’s critically important not just for your career, but for your psychological well-being,” he says.

Celebrate your wins

When you’re working on your own at home, staying motivated can be difficult, especially when distractions — Facebook, that pile of laundry, the closet that needs organizing — abound. One smart way to maintain momentum is to spend a moment or two acknowledging what you have been able to accomplish that day, rather than fixating on what you still need to do. “Take some time at the end of the day to attend to the things that you got done instead of the things you didn’t get done,” says Kramer. You might also keep a journal in which you reflect on that day’s events and note what you were able to check off your to-do list. The daily reminder of what you were able to finish will help create a virtuous cycle going forward.

Principles to Remember:

Do:

Make a schedule and stick to it

Focus on what you’ve accomplished at the end of each day to keep yourself motivated

Create a dedicated workspace and let your family know that you are unavailable during work hours

Don’t:

Try to work all day without regular breaks — your productivity and motivation will suffer

Isolate yourself — go the extra mile to meet up with colleagues and peers to talk shop

Neglect to check in regularly with colleagues and bosses — it’s important to make yourself ‘visible’ even if you aren’t in the office

Case study #1: Stay organized and adjust

Freelancing from home for Heather Spohr, a writer and copywriter based in Los Angeles, wasn’t her choice. After 10 years in the corporate world, she was laid off from a six-figure sales job in 2008, but “I had a baby at home, so I just sort of shifted my focus,” Heather says. Today, she writes articles for everyone from parenting and banking sites to “car companies, drug companies, beauty companies, you name it,” she says.

Despite wanting to keep regular working hours, Heather often finds that the pressures of finding new writing jobs in addition to executing the ones she’s already landed often push her into overtime. “It can be very hard maintaining a schedule because freelancing is so feast or famine,” she says.

To give more structure to her working life, she sits down each Sunday evening after her kids have gone to bed and maps out of the following week. “I’m huge on lists,” she says. “I make daily schedules and prioritize tasks. Then everyday I revise that schedule because things come up.” She also makes it a habit to include an hour of flex time into her daily schedule. That way, “if my sitter’s going to be an hour late, it’s not going to wreck my day,” she says. “Once I started doing that, my stress level dropped considerably.”

She insists on taking regular breaks, setting a timer that goes off every 45 minutes. “Then I give myself 5 to 10 minutes to get up, get a snack, look at Twitter, play Candy Crush, whatever,” she says. “At first I felt guilty for doing it, but I would remind myself that when I worked in an office, I’d get interrupted so much more than that. Even with these breaks, I’m still getting more done.”

What Heather finds most challenging is the isolation. “I’m very social and extroverted, and I love being surrounded by people,” she says. To combat loneliness, she schedules time with fellow writers and friends for face time. She has also found a thriving network of other work-at-home writers in various online discussion groups. “There are lots of people I’ve clicked with through Citigroup’s Women & Co. group and LinkedIn, and there will be chat rooms I’ll pop into to say hello and connect,” she says.

Case study #2: Maintain work-life boundaries

When Catherine Campbell launched her own branding and strategy business in Asheville, North Carolina, earlier this year, she already had some experience working from home. Her last job, as marketing director for a copywriting agency, was a virtual one, but she knew that launching her own company would require more discipline. “Managing my time and not overworking was going to be the biggest challenge,” she says.

From the start, Catherine set strict rules for keeping her work life distinct from her home life. “It’s all about boundaries and mindset,” she says. She never uploaded work emails to her phone, so that she wouldn’t be tempted to check messages at all hours of the day. She is only available on Skype by appointment and explicitly states in her email signature that her working hours are 9am to 5pm EST. “When you leave a traditional office, you’re often done for the day,” she says. “You have to approach it the same way when maintaining a home office.”

She also tries to block out the first hour of each day to check email, do her own promotion and marketing, and make a list of daily goals. ”Allowing what I call a quiet hour for myself just to get focused and to knock out some of the smaller tasks allows me to really jump into the larger client work for the rest of the day,” she says. She also makes it a point to leave the house everyday, rain or shine, at 5pm. “I go for a walk, pick up my son, go to a networking group, grab that last item for dinner, or meet with a friend or colleague to talk shop,” she says.

She also doesn’t sweat the times when she has to work late on a project because she gives that time back to herself later on. “It’s what I would call ‘smart scheduling,’” Catherine says. “You say to yourself, OK, I have this extra client this week or this project emergency so I’m going to work these two nights. But then I’m going to cut back on Friday and get out of the office at 2 pm.”

“Working from home is always a fine line,” she says. “You have to learn how to give and take with yourself so that your business doesn’t take over who you are.”

September 30, 2014

Each Employee’s Retirement Is Unique

When people have been around a long time, you tend to take what they bring to the table for granted and you don’t realize what you lose until they go.

I remember the havoc raised by the retirement of our family company’s store manager in Piraeus. He was intimately familiar with every single one of our customers all over Greece, their distinctive preferences and whims. If it was a customer’s birthday you saw their name on the top of his daily to-do list.

He was able to combine respect and familiarity in communicating with customers and he knew how to apply his sense of humor. I often got the impression that clients shopped in our store more because of the pleasure of interacting with him than because of the quality and price of our products. It was fun to do business with Gerassimos Antzoulatos.

We realized that his replacement, although one of our most successful and trusted salesmen, would be unable to fill the gap his absence created. He simply didn’t have the ability to connect as well. My father and I discussed how we could recapture Gerassimos’s empathetic approach to business.

Our solution was to make his retirement gradual: start by staying away one day a week, then two, then three, and so on. He was happy with the arrangement because he dreaded not coming into work as much as we were dreading not having him. We gave him the title of “Company Coach” so that he could have an official transition role and be clearly focused on training, and gradually, over time, he was able to pass on his approach to managing to his successor.

The Gerassimos experience made my father and myself aware of the importance of preserving the skills of our retirees. On our side, the company needed to ensure that the departure of trusted and experienced people would not deprive it of their valuable skills and know how. In order to prevent this happening, we needed to get retirees like Gerassimos involved in coaching their replacements and monitoring their performance. So we created a “retirement kit” for retiring employees, along the lines of the deal we had worked out with Gerassimos.

Of course, “gradual retirement” through coaching replacements didn’t work with everyone so we were flexible, adapting the kit to accommodate individual needs. Some people, for example, wanted a clean break when retirement came. So the HR Department would explain the process to people approaching retirement and, as needed, tailored the deal to the needs and preferences of each person. I can remember asking one employee to write down in detail of how he carried out his job. In all cases, however, an extra fee was paid for the retiree’s extra work.

We started the process a year ahead of each employee’s retirement. We would involve retirees in the selection of their successors and discuss with them what skills needed transferring and what the best way was to go about it. During a coaching period, the retiree would give us regular updates we would get regular feedback regarding progress and offer suggestions for follow-up coaching and development.

When the final retirement day arrived, we hosted an event in the retiree’s honor at which we presented him or her with a company award and a certificate acknowledging their contribution. We also encouraged them to attend company staff gatherings after retirement. In this way they could feel that, although their careers may have ended, they still remained an integral part of the business.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers