Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1356

October 6, 2014

3 Terrible Strategies for Companies Seeking Growth

Some call . Some call it a never-ending recession. Some call it a disconnect or a decoupling. Some call it a not-quite recovery.

Here’s the truth. Econ doesn’t have a word for whatever we’re in…because whatever we’re in flouts the so-called laws of economics. Quarterly results look great; job growth is “up;” and financial markets are ebullient. So why are so many still worse off than they were before? Why hasn’t all this “growth” actually translated into a real feeling of prosperity? And – as so many CEOs would like to know – is there any way to make money in this era of perma-semi-stagnation?

Most leaders seem to think they have three choices:

Option 1: Shine it with gold and sell it to the super rich. Make it a “luxury”! Rebrand! Make the logo platinum! Add a fleet of maids and an entire army of butlers to it, if you have to!

Witness the rise of the ten thousand dollar cocktail, the million-dollar pair of jeans, luxury doggy spas (Wagsworth Manor: “a luxury retreat for the furry elite”). Nokia tried it with phones—and went down in flames. The UK tried it with an entire economy, turning the once great city of London into a ghost town of global oligarchs who own entire blocks, but spend barely a few weeks there. It’s a strategy of appeasement: trying hardest to placate the strongest.

Why doesn’t the gambit of merely trying more and more desperately to please the every idle whim of the super-rich work? After all, they’re the people who still have money left, right? It doesn’t work well for a simple reason: there simply aren’t enough of them, and they simply can’t spend enough on consumption, to make up for the world’s falling middle classes. Your profit margins might rise, temporarily, but soon you’ll be furiously adding another platoon of maids or regiment of butlers, daubing platinum gilding on top of the gold leaf. It’s a losing game played more and more desperately for a shrinking prize.

Option 2: Sell to the rising global “middle classes” instead! Forget appeasement…let’s flee! To the very edges of the world, if we have to.

Except when you think about it, that doesn’t work either. The rising “middle classes” are significantly poorer than the ones that are falling. A middle class person in India makes maybe $10k a year and a middle class person in America used to make $50K. So sure: you can flog the same junk to the so-called rising global middle classes. But before that’s a valid strategy, they’ll have to rise a lot faster and a lot further than they probably can, given a stagnating global economy.

Option 3: Fleece the falling. After all, it’s true that they might be falling — but they’ve got credit cards and home equity. And on the back of that debt, says the most desperate junior vice president at Useless Widget Co, we can grow our profits! It’s the story of the “growth industries” of the last decade. The pawnshop economy. Casinos, payday lenders, private prisons, insta-on-demand-McWorkers serving everyone else who can barely afford them five dollar triplex mega soy mocha latteccinos. Fine print clauses in impossibly long contracts to hit people with hidden fees.

Can you earn a few extra pennies by fleecing people? Sure you can, Scarface. But here’s what you can’t earn: an organization worth building. Consider the sad, predictable story of embattled payday lender Wonga. Your customers will despise you. Your employees will hate working for you. Society (or at least Germany, Sweden, Australia, and Canada) will fight you. You’ll be vilified…and sooner or later, the regulators will force you to change. It’s a losing battle; one fought merely for marginal pennies of short-term gain that are already shrinking.

Finding cleverer, crueler ways to turn a more poisonous profit?

That’s not what strategy’s about at all.

Strategy is about building an institution that can compete. Competitiveness isn’t merely short-term profitability. It is about all the things that underlie lasting, healthy prosperity. It means having not just a “vision statement” but a passion. Not just a mission but a point. It’s about doing something that matters.

Appeasing, fleeing, and fleecing are precisely the wrong strategies for an age of stagnation—because if you employ them, what are you, really? Just another agent of stagnation. And so, sooner or later, your destiny will inevitably be stagnation.

Skepticism Is Warranted When It Comes to Facebook Likes

Facebook Likes are so valuable to people promoting products, songs, and movies that a thriving business known as “Like farming” has sprung up, and you can buy 1,000 Likes for $50 (same price for 5,000 Twitter followers or 200 Google +1s). In a study reported by Pacific Standard, researchers who paid for Likes found that unlike real Likes, fake Likes tend to rush in all at once or in blocks of a few hundred a day, and fake Likers are generally older. Also, in comparison with real Likers, a higher proportion of fake Likers are male.

Why Tesco’s Strengths Are No Longer Good Enough

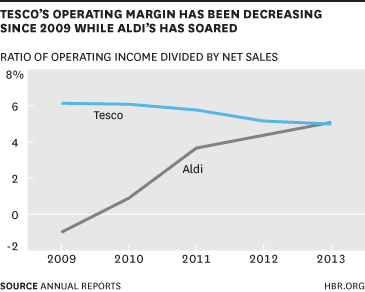

Troubles at Tesco, the UK’s leading retailer, are mounting. If round after round of profit warnings was not enough – group operating profits fell 20% between 2011 and 2013 and are likely to fall another 30% in 2014 — the company recently announced it had overstated its first-half profit by about $400 million. The “accelerated recognition of commercial income and delayed accrual of costs” undoubtedly flatters short-term results, but it soon catches up with you, as four suspended senior executives have found out. Tesco, the success story of the British retail scene for the last 20 years, has suddenly fallen from grace. How did this happen?

Successful companies are notoriously prone to pursuing tactical fixes rather than confronting strategic problems. They exhort their people to try harder, introduce overhead cost reduction programs, and reorganize – anything rather than admit that their strategy needs an overhaul. Fiddling the books is normally the last resort, when all else has failed. It is also often a sign of impending bankruptcy, but this shouldn’t happen at Tesco. It is still the biggest player in the UK supermarket scene by a mile, but unless it opens its eyes to its strategic challenges and begins addressing them effectively – i.e., shows a little more Strategic IQ – it will continue to spiral down.

UK retail, like the rest of the developed world, is witnessing a few big long-term trends. Private label (retail-branded merchandise) has been growing for years – since Sainsbury and Marks & Spencer invented it over 100 years ago – increasing in quality and forcing down brand premiums. It provides consumers with a viable, lower cost alternative to the manufacturer branded products. Tesco came to the party much later in the 1980s but ended up winning with its “good-better-best” private label lines, setting the industry standard for how to play the private label game.

The rise of convenience store chains is another big trend in the UK. Consumers are increasingly shopping for a few items every day rather than waiting for the weekly or monthly supermarket trip. There have always been convenience stores in the UK, but the shabby, independent corner shops are giving way to sparkling new outlets run by the supermarket chains full of fresh merchandise, albeit at premium prices. Of the big supermarket chains, Tesco was the fastest to pick up on this opportunity in the early 1990s (with Tesco Metro and Tesco Express), and it remains in the lead.

And of course, online shopping is the other big trend that started at the turn of the century. Why travel to a supermarket for the monthly big shop if you can buy it online and have it delivered? Tesco was quick to pioneer in this area with the launch of tesco.com in 2000 and is still the leader in the UK.

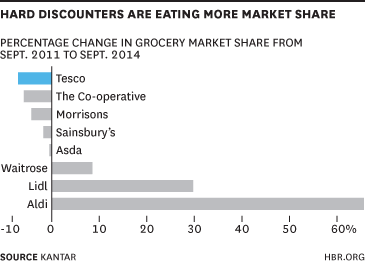

So with such a track record of strategic innovation, why has Tesco been blindsided by the hard discounters like Germany’s Aldi and Lidl? In the last three years, these two companies have rapidly gained share and now account for more than 8% of the market, while Tesco has lost more than 2% share, down to 28%.

Aldi opened its first UK store in 1990, but made little progress then. UK consumers didn’t seem to want to shop in cheap looking stores with only 1000 private label items on offer and minimal service. And yet Germans, even those with Porsches, shopped at Aldi. The hard discount format accounts for as much as 40% of the German market, and for some good reasons.

Aldi offers not just low prices, but convenience. There are over 4,000 Aldi stores in Germany – they are everywhere. Tesco’s idea of convenience, like most of the large UK chains, is small outlets in high-traffic locations stocked with a narrow line of products, many of them fresh food, at prices that are far higher than in the supermarkets. This is all very well for the rich punters prepared to forgive Tesco for its gouging, but for the majority of UK consumers, this premium isn’t viable. German consumers, in contrast, get convenience and quality merchandise at lower prices so they can afford the Porsche! Everyone shops at Aldi.

Now UK consumers are discovering that Aldi is good for them too. This is partly because they have gone through tough times in the recession and wages are stubbornly low. It is also because Tesco has raised prices in the UK to pay for its less profitable international ventures, which has left it vulnerable at home. (Wal-Mart, the world’s number one retailer, is also guilty of this – it makes most of its money in the U.S. and spends it in international markets. As a result, dollar stores have gained significant ground in the U.S.)

Finally, Aldi is growing because it is tailoring its offering to the UK market. Blindly transporting a retail concept across international borders is seldom a recipe for success. But Messieurs Barnes and Heini, joint managing directors of Aldi UK, have added more fresh products and up-market lines at prices 15-20% below those of regular UK supermarkets. The goal is to attract the British middle classes, and it appears to be working. Aldi UK sales grew from $6.3 billion to $8.6 billion in 2013, and operating profits increased 65% to $422 million. The company plans to double the number of outlets in the UK to 1,000 by 2022, and it won’t stop there if Aldi Germany is any indication.

You might wonder how anyone can make money with such low prices. The answer is simple – selling more. Hard discounters aim for twice the volume with the same fixed costs so they can make the same returns at half the gross margin. Aldi’s sales per employee are already twice those of Tesco in the UK.

Tesco and fellow major UK supermarket chains seem to be frozen like the proverbial bunny in the headlights in the face of these discount convenience stores. But Tesco, with the biggest purchasing power, the best experience of private label, and strongest track record of strategic innovation, is hurting more than most.

And talent knows where the future lies. In its latest annual report, the Times places Tesco 23rd in its ranking of top 100 graduate employers in the UK, down from 15th last year; Aldi moved up from 6th to 4th place.

Many thousands of discount convenience stores are going to appear in the UK over the next decade. Tesco must decide whether it is prepared to risk cannibalizing its other formats and compete in this segment or be left behind. In the past, Tesco has demonstrated it has the wherewithal to add many more convenience stores a year than the target of 60 Aldi is setting itself, and it has consistently shown itself to be one of the first to embrace new formats. Whether they can do it this time depends on the strength of their leadership. Distractions caused by fiddling the books will not help.

October 3, 2014

Impact Investing Needs Millennials

As impact investing tries to make the move from philanthropic thought experiment to powerful instrument for global change, a vital demographic and financial reality is emerging — it’s going to be millennial investors (particularly those inheriting or building significant private wealth) who make or break it.

Since the term was coined in 2007, impact investing — the idea that private capital can be deployed to alleviate pressing social needs like access to clean water, affordable housing or preventative healthcare while returning a financial profit — has attracted significant public and media attention. However, impact investing’s legitimacy as an alternative asset class remains elusive.

Impact investment continues to suffer from limited transaction flow and anemic dollar commitments. Most relevant to stunted growth, however, is cultural resistance — the inertial apathy of traditional financial players who are wary of novel, risky investment structures and skeptical about trading some amount of profitability for social return. Without the commitment of commercial financiers to include impact investments in their core portfolios, or pressure from mainstream investors to insist that they do, impact investment’s route to scale is uncertain.

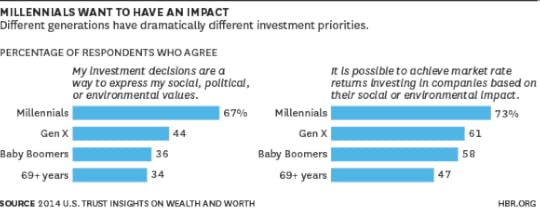

Enter the millennials (the roughly 80 million Americans born between 1980 and 2000, and their peers around the world), who conceive of financial return differently, and more expansively, than their elders. For millennials, pressing social problems are not just the preserve of philanthropists or governments. Millennials consistently cite social impact as one of the most important roles of business. Of all the generations alive today, millennials are the most willing to trade financial return for greater social impact, according to “Millennials and Money,” a 2014 study from Merrill Lynch’s Private Banking and Investment Group.

According to another study, U.S. Trust’s “Insights on Wealth and Worth,” wealthy millennials are almost twice as likely as their grandparents to regard their investments as a way to express social, political, or environmental values (see chart), and nearly three-quarters of millennials believe that it is possible to realize market-rate returns investing in companies based on their social or environmental impact.

These opinions matter. Millennials are poised to share in the largest intergenerational wealth transfer in human history — one widely-cited estimate puts its value at $41 trillion in the United States alone by the year 2052.

Millennials therefore represent a sizeable, well-capitalized cohort of investors with a generational commitment to furthering the social good and a desire to engage their peers — and parents — in doing likewise. As recent events show, they are beginning to act on these principles. At the recent Nexus Global Summit on Innovative Philanthropy at the United Nations, which we attended, 600 largely millennial-aged participants from 41 countries representing nearly $750 billion in private and family wealth spent three days exploring and sharing case studies of social investments. Some of the investments had the sophisticated deal structures of large corporate transactions, some showed private sector engagement driving infrastructure development and quality-of-life improvement, and all demonstrated growing connections between policy and profit at national and international levels.

When we contrast our inspiring experience at Nexus alongside the still-limited impact- investment landscape, we conclude that three actions will be critical to accelerating the mobilization of capital by millennials and allowing impact investing to scale to a projected $1 trillion market by 2020.

First, private-sector entrepreneurs need to keep identifying opportunities to build companies that can accept and use impact capital to grow to scale, providing an increasing capacity for deal flow. Some commentators have compared the opportunity presented by impact investing to the early days of venture capital. We find such comparisons premature, but agree in one respect: to scale, impact investing will require a small contingent of ambitious investors prepared to make sizeable bets on promising entrepreneurs in order to demonstrate the asset class’s viability.

Second, millennials should vote with their wallets and demand that retail banks, wealth managers, and advisory firms provide a suite of financial products that range across the risk/return/impact triangle. Wealth management firms acknowledge that they are not yet positioned to give impact investing equal footing to conventional investments. In the “Millennials and Money” report we cited above, Merrill Lynch described one client’s impact investment as “a tricky undertaking for both client and advisor…the collaboration, in many ways an experiment, is ongoing.” For the same investment, the report asks, “what measures should be used to judge the social impact of these investments? How long should you wait for that impact to take hold, let alone a profit stream?” These are the questions investors are looking to advisory firms to answer, not just ask.

Of course, not all millennials will inherit or create millions in personal wealth. But our generation is remarkably consistent in attitude, regardless of financial position — 92% say business success should be based on more than profit. Millennials also believe in the power of private capital. More than half of millennials in the same study (conducted by Deloitte) believed that business, not government, will have the greatest impact in solving society’s most pressing challenges. We expect that wealthy millennials will pave the way for the mainstreaming of impact investment products for their peers as well as their Baby Boomer and Generation X parents and grandparents, whatever the size of their portfolios.

Third, growing impact investing will take collaboration and cooperation. Public- and private-sector actors will need to partner with academia to aggregate information on impact investing deal activity, compile best practices in impact measurement, reduce transaction costs, and inspire new participants through social engagement. The first report of the U.S. National Advisory Board on impact Investment is an important first step; the next challenge for government is to design and foster a supportive regulatory environment, one that regards private capital as positive force to be harnessed, and impact investors as partners in social progress.

We anticipate that millennials’ growing commitment to impact investing on multiple dimensions — dollars committed, deals completed, financial returns achieved, and development goals addressed. Most importantly, however, we look forward to a growing alignment of developed world capital with a social conscience, driven by one of the core millennial mantras: doing well by doing good.

The Most Innovative Companies Don’t Worry About Consensus

Consensus is a powerful tool. When CEOs set out to conquer new markets or undertake billion-dollar acquisitions, we’d hope they’d at least sought out some consensus from their trusted advisors. We hope they’d be as sure as possible that their teams are ready, that their strategies are sound, and that they’d done their diligence.

The problem with consensus is that it’s expensive. And while it’s worth the cost of consensus in the pursuit big, bold moves, it’s often crushing to small experimental ones.

Consider the story of Nick. Nick is a typical manager at a one of the world’s most successful widget companies. He’s well respected, but far from the top of his organization. The good news for Nick’s company is that Nick has some great ideas; ideas for new ways of producing and distributing widgets that have never been thought of before. Nick’s company is also lucky that Nick has read The Lean Startup. Nick readily grasps the value in testing his ideas before asking for any full-scale operation.

Like a good student of the lean start-up, Nick plans out a cheap test for his latest idea, “Widget 2.0.” He determines that he can take just $10,000 to determine if Widget 2.0 has legs. If the test goes well, he’ll figure out the next step. If not, he’ll get back to his day job.

Inside most companies, this is where the problem kicks in.

Nick’s company is like most companies — only a small number of key executives have real authority to distribute cash and try new things. Everyone else is happy to defer responsibility (generally terrified of approving a failed experiment). But like most hierarchical organizations, Nick’s managers and their managers expect to be informed of his ideas before they make their way to the big boss. Even though there is only one check writer, there are a lot of potential naysayers. So Nick sets out to convince his key “stakeholders” to support his test plan for Widget 2.0. He has meeting after meeting and slowly gets people on board. Finally they approve his $10,000 dollar test.

The test fails, and Nick goes back to his day job. Success, right?

Not really.

In the last few decades executives have started to get wise about the value of systematically testing new ideas. Whether it was Rita McGrath explaining the importance of identifying risk in inherently risky ventures, Rosabeth Moss Kanter encouraging leaders to let their small experiments proliferate, or Eric Ries and Steve Blank teaching us the value of systematic experimentation and innovation accounting, the message has been clear: constantly testing new ideas is vital in the search for organic growth.

The reason testing is so vital is because it minimizes the investment required to eliminate uncertainty. In so doing, you increase the speed of innovation and decrease the cost of failure.

In the case of Widget 2.0, Nick’s company appeared to understand the value of his experiment… but their process got in the way. Consensus didn’t just slow Nick down, it dramatically increased the cost of his test. If Nick made $120,000 a year and he spent just a month trying to drive consensus around the project, the cost of his salary during the month of meetings doubled the cost of the experiment. If Nick had a small team working for him, seeking consensus may have quadrupled the cost of the experiment. And that’s not even accounting for the executives’ time that he had to sit down with.

Again, consensus can be a powerful tool. Consensus can be used to ensure multiple perspectives are looked at in any decision process. Consensus can help us honor fiduciary responsibilities. But it’s is slow, it’s messy, and it’s expensive. It eats away at the value of experimentation.

Milton Friedman once argued that the beauty of private capital is that it streamlines the act of experimentation in a capitalist society. Instead of driving consensus, “the market breaks the vicious circle [of having to convince a variety of stakeholders].” Individual entrepreneurs only need to persuade a few empowered parties that their ideas “can be financially successful; that the newspaper or magazine or book or other venture will be profitable.” To drive those same benefits inside our firms, consensus needs to be sought only where necessary.

So the challenge to managers is determining how to manage the consensus tax. How do you avoid investing in mediocre ideas, but still act with the speed and efficiency that helps you increase your ROI and get more at bats?

1. Acknowledge that not all investments are the same. Some investments are inherently complex and difficult to test systematically or at low cost. Often, these investments require that we drive consensus and be as sure as possible before we experiment. Others, however, are far less risky. If I can spend $10,000 for a one-day experiment that will tell me if a product won’t work in the future — that’s cheap. (That’s basically the same cost as the pro-rated salaries of a 100-person business unit on a 90-minute call.)

Managers in the modern organization need different processes for different types of investments. If your organization has one pathway for funding you’re doing it wrong. Either, you’re not considering the complex investments deeply enough or you’re crushing the small ones.

2. Push decision authority as low as possible. Senior executives are busy. As much as they want to control everything in the organization, it’s simply not realistic. To be nimble and innovative, part of the key is pushing decision authority as low as possible (but not lower).

What’s as low as possible? That’s going to change from situation to situation. But the key is acknowledging that the more senior you make your decision makers, the more waste you’ll require of those looking to experiment. It’s much better to have a slightly less qualified decision maker that is empowered to act on a much shorter timeline than to force decisions all the way to the top. If the latter is your approach, the only thing that will happen is your execs will end up drowning in a sea of meetings and nothing will ever get done.

To push decisions down, you need to limit your downside. Make sure that you hire smart people who you’d trust to make a good decision (not just order-takers). Make sure that you clearly define what success is for an experiment. And make your corporate mission and boundaries well known and well defined. If you do each of those things and distinguish between experimental investments and more meaningful operational investments, you’re already going to be in a good spot.

3. Don’t punish failure. Punish waste. Most executives are happy to point up the chain in order to avoid retribution. They’d rather not make a decision, because decisions can fail to pay off. It’s a lot easier to coordinate an additional meeting than to take the heat for another investment.

If you truly want to innovate, it’s important not to punish failure. Similarly, it’s not alright simply not to punish people at all. The type of punishment that I’ve seen work well is punishing waste; those who waste resources by failing twice the same way or those who waste time by being satisfied sitting in meeting after meeting without getting anything done. If you have an intrapreneur out there pushing the boundaries, learning new things, and adapting, you’re likely to have success in the future.

As Joe Bower once explained to me – “In pursuit of the novel, small is beautiful.” I’m more convinced than ever that he’s right. In part because small limits downside. But in part, because it also limits the need for consensus. In your search for innovation, it’s vital that you use consensus with some discretion. It’s a powerful tool, but it’s not for every occasion.

Integrate Analytics Across Your Entire Business

An Accenture survey conducted last year found that only one in five companies said that they were “very satisfied” with the returns they’ve received from analytics to date. One of the reasons analytics is working for the companies in this select group is because they tend to deploy analytics technologies and expertise across the breadth of the enterprise. But the survey also found that only 33% of businesses in the U.S. and Western Europe are aggressively adopting analytics across the entire enterprise. This percentage marks an almost four times increase in the trend of enterprise-wise adoption compared to a survey conducted three years earlier, but the question must still be asked — how can we improve this number?

Cross-functional analytics can be a challenge to implement for a variety of reasons including functional silos and a shortage in analytics talent. Yes, these obstacles can seem daunting at first, but our experiences tell us that they are not insurmountable. Following are tips organizations can follow to drive a horizontal focus on analytics and achieve their desired business outcomes, such as customer retention, product availability, or risk mitigation.

Identify the right metrics that “move the needle.” First, senior management should decide on the business goal for an analytics initiative and the key performance indicators to track that will put them on the right path toward success. For a high-performing retailer, we found that customer retention, product availability, labor scheduling, product assortment, and employee engagement were all leading indicators to driving growth and profitability for the company. Selecting the right critical metrics is a cornerstone of success as it brings focus and clarity on what matters most to the business.

Establish a center of gravity for analytics. Next, create an Analytics Center of Excellence (CoE) that spans the enterprise. A CoE is a team of data scientists, business analysts and domain experts from various business functions — sales, marketing, finance, and R&D, for example — that are brought together to facilitate a cross-pollination of experiences and ideas to find solutions to a variety of business goals. The CoE itself is organized into pods — generally made up of four to six people, with each person offering a different skillset — that are deployed across the business to solve problems that span multiple functions.

Develop a robust root cause analysis capability. Once CoE is created, the pod teams should perform root cause analyses to support the performance management process. The retailer example mentioned above used root cause analysis to answer the question around what factors contributed to an unsuccessful marketing promotion. They tested hypotheses by asking questions such as: were results poor because of the marketing message, pricing and bundling, product availability, labor awareness of the promotion or did a competitor have an attention-grabbing marketing campaign happening at the same time? A successful CoE model provides a company with the capability to not only answer these questions with validated cross-functional insight, but also to determine the best decision around what to do next.

Make collaborative decisions. Using a CoE affords functional managers the ability to make collaborative and informed decisions. They are not left alone to develop root cause analysis insights in a vacuum. Rather, as a team, the managers and the CoE are able to make decisions and take actions based on the insights garnered together. To accomplish this, it is critical to establish a forum with the cross-functional business leaders to share and visualize the data and interpret the insights for the purpose of decision making.

As an example, a consumer products company used a weekly executive management meeting as the forum to discuss the CoE’s insights and make decisions based on the outputs. In this instance, the head of the Analytics CoE was the facilitator of the meeting and focused the executives’ time on the decisions that needed to be made based on the important insights the data identified versus the noise that should be ignored (e.g. to better understand the effectiveness of a new product launch). The combination of data science, advanced visualization, and active decision making — along with an impartial facilitator with deep content expertise — was key to collaborative and effective decision making.

It’s important to note that once data-driven decisions are made and actions are set in motion, companies should track their progress against the metrics that were established at the start of their analytics journey. If goals are not being realized, they should repeat the process to understand the root causes of an issue that will help them achieve their business goals. In one instance, a bank’s Analytics CoE delivered such consistently positive results that the company formally branded all analysis coming out of the CoE so the business leaders could be aware of its quality and credibility outright. The branding encouraged business leaders to trust the insights and act on them faster.

When a company expands its analytics purview from functional to horizontal, it opens the door to greater opportunities and successes. While removing silos and taking a teaming approach to analytics is part of an internal virtuous cycle, another cycle is also created — the attained results are experienced by the customers and will keep them coming back for more.

Regular Exercise Is Part of Your Job

When we think about the value of exercise, we tend to focus on the physical benefits. Lower blood pressure, a healthier heart, a more attractive physique. But over the past decade, social scientists have quietly amassed compelling evidence suggesting that there is another, more immediate benefit of regular exercise: its impact on the way we think.

Studies indicate that our mental firepower is directly linked to our physical regimen. And nowhere are the implications more relevant than to our performance at work. Consider the following cognitive benefits, all of which you can expect as a result of incorporating regular exercise into your routine:

Improved concentration

Sharper memory

Faster learning

Prolonged mental stamina

Enhanced creativity

Lower stress

Exercise has also been show to elevate mood, which has serious implications for workplace performance. I’m willing to bet that your job requires you to build interpersonal connections and foster collaborations. Within this context, feeling irritable is no longer simply an inconvenience. It can directly influence the degree to which you are successful.

There is also evidence suggesting that exercise during regular work hours may boost performance. Take, for example, the results of a Leeds Metropolitan University study, which examined the influence of daytime exercise among office workers with access to a company gym. Many of us would love the convenience of free weights or a yoga studio at the office. But does using these amenities actually make a difference?

Within the study, researchers had over 200 employees at a variety of companies self-report their performance on a daily basis. They then examined fluctuations within individual employees, comparing their output on days when they exercised to days when they didn’t.

Here’s what they found: On days when employees visited the gym, their experience at work changed. They reported managing their time more effectively, being more productive, and having smoother interactions with their colleagues. Just as important: They went home feeling more satisfied at the end of the day.

What prevents us from exercising more often? For many of us, the answer is simple: We don’t have the time. In fairness, this is a legitimate explanation. There are weeks when work is overwhelming and deadlines outside our control need to be met.

But let’s be clear: What we really mean when we say we don’t have time for an activity is that we don’t consider it a priority given the time we have available.

This is why the research illuminating the cognitive benefits of exercise is so compelling. Exercise enables us to soak in more information, work more efficiently, and be more productive.

And yet many of us continue to perceive it as a luxury; an activity we’d like to do if only we had more time.

Instead of viewing exercise as something we do for ourselves—a personal indulgence that takes us away from our work—it’s time we started considering physical activity as part of the work itself. The alternative, which involves processing information more slowly, forgetting more often, and getting easily frustrated, makes us less effective at our jobs and harder to get along with for our colleagues.

How do you successfully incorporate exercise into your routine? Here are a few research-based suggestions.

Identify a physical activity you actually like. There are many ways to work out other than boring yourself senseless on a treadmill. Find a physical activity you can look forward to doing, like tennis, swimming, dancing, softball, or even vigorously playing the drums. You are far more likely to stick with an activity if you genuinely enjoy doing it.

A series of recent studies also suggest that how we feel while exercising can influence the degree to which it ultimately benefits our health. When we view exercise as something we do for fun, we’re better at resisting unhealthy foods afterwards. But when the same physical activity is perceived as a chore, we have a much harder time saying no to fattening foods, presumably because we’ve used up all of our willpower exercising.

Invest in improving your performance. Instead of settling for “getting some exercise,” focus on mastering an activity instead. Mastery goals, which psychologists define as goals that center on achieving new levels of competence, have consistently been shown to predict persistence across a wide range of domains. So hire a coach, enroll in a class, and buy yourself the right clothing and equipment. The additional financial investment will increase your level of commitment, while the steady gains in performance will help sustain your interest over the long .

Become part of group, not a collective. One recommendation aspiring gym-goers often receive is to find an exercise regimen that involves other people. It’s good advice. Socializing makes exercise more fun, which improves the chances that you’ll keep doing it. It’s also a lot harder to back out on a friend or a trainer than to persuade yourself that just one night off couldn’t hurt.

But there’s another layer to this research—one that is well worth considering before signing up for an exercise class this fall.

Studies indicate that not all “group” activities are equally effective at sustaining our interest.

We are far more likely to stick with an exercise regimen when others are dependent on our participation.

As an illustration, consider the standard yoga or pilates class. Each involves individual-based tasks that require you to work alone, albeit in the presence of others. Both activities technically take place within the context of a group, however in these cases the “group” is more accurately described as a collective.

Research suggests that if you’re looking to establish a routine that sticks, exercising as part of a collective is preferable to working out alone, but it’s not nearly as effective as exercising as part of a team. So consider volleyball, soccer, doubles tennis—any enjoyable, competence-enhancing activity in which your efforts contribute directly to a team’s success, and where if you don’t show up, others will suffer.

Regardless of how you go about incorporating exercise into your routine, reframing it as part of your job makes it a lot easier to make time for it. Remember, you’re not abandoning work. On the contrary: You’re ensuring that the hours you put in have value.

Being Bilingual Makes You Better at Non-Linguistic Tasks

In a small study, bilingual people were about a half second faster than monolinguals (3.5 versus 4 seconds) at executing novel instructions such as “add one to x, divide y by two, and sum the results,” say Andrea Stocco and Chantel S. Prat of the University of Washington. The findings are in line with past studies showing that children born into bilingual families exhibit superior performance on non-linguistic tasks. The experience of flexibly applying rules when speaking multiple languages may strengthen bilinguals’ executive functioning, the researchers say.

An Open Office Experiment That Actually Worked

Nowadays many people regard open-plan offices with skepticism — remnants of a once-cool work space fad that led to more distraction than innovation. As this article explains, there are downsides to too much transparency.

But we at The Bridgespan Group decided to test that conventional wisdom six months ago when we moved 70 employees from offices and cubicles on two floors of a building in Boston’s Back Bay to a dramatically different space fashioned out of the gutted top floor of a tower four blocks away.

It was a bid to tear down hierarchies and invigorate our already collaborative culture, and so far the experiment has been a success. The open layout has increased productivity, energy and connectedness. But the journey from a traditional office to this new space where everyone shares work benches, tables, lounge areas, and first-come-first-served private rooms took careful thought and planning.

The planning

Just over a year ago, 22 staff members — drawn from all roles and functions — gathered in our raw, unfinished new space for two and a half days to explore what to do with it. A team from Architects of Group Genius facilitated decision-making, joined by our building architects from CBT. Our challenge was to design a dramatically different kind of office that would enhance teamwork and insight around the projects at the heart of our work advising non-profit organizations. We also wanted to provide a much broader array of work space choices for all staff every day, yet keep costs down, befitting our own non-profit status (and budget!).

We broke into groups to think about the environments where we did our best work; we took field trips to spaces built for knowledge workers and created a spectrum of design schemes, from next-to-normal to radical. (A smaller group had already spent months researching design concepts, listening to TED talks on sound and space, and visiting innovative organizations.)

During the process, many of us thought back to the mid-summer week when the air conditioning system in half of our existing offices had suddenly failed. Forced to squeeze into the cooler space and share offices, cubicles and desks with colleagues, staff started working together in casual ways outside pre-planned meetings and appointments. Could we duplicate this happy accident in our new space? The literature told us that workers want personalization and choice. What if we achieved that not by offering a fixed office or cubicle, but by giving each staff member, at every level, many choices of where to sit and how to work every day, and within each day, as well as large flexible spaces for people to meet, brainstorm, and otherwise collaborate.

Photo credit: © Anton Grassl/Esto

Photo credit: © Anton Grassl/EstoThe execution

At the end of our design lab, we handed off to our architects a “radical” plan which they built out over the next few months.

It included:

an open café, where staff bump into each other making coffee, or making sandwiches and catch up or take care of business

a “laboratory” space with tables, sofas and white boards at the heart of the office, where teams meet and discuss work previously done in closed conference rooms

a large, closed-off library space with lots of natural light that we call the “quiet car,” where people can work without interruption

several small comfortable seating clusters throughout the office for small-group conversations

a bank of small private rooms for people to use when they truly need privacy for meetings, phone calls, or individual work–but no private offices even for the most senior staff

sitting and standing work stations where people can park themselves day-to-day

glass-walled conference rooms so most meetings are seen by everyone, even if they aren’t heard

background noise masking, so that conversations in the open are heard as mild hubbub rather than distinct, distracting words

lockers in which staff can keep personal items

You can find more photos on this page of CBT’s website and at The Daily Muse.

Photo credit: © Anton Grassl/Esto

Photo credit: © Anton Grassl/EstoThe results

Six months in, we continue to be amazed at how differently we work in the new space and how much the spirit of our office has changed. We used to make appointments to see each other; now, we often just run into each other, and all kinds of new ideas emerge from these unplanned collisions of two or three or four people.

Formal meetings are routinely held in the open areas, where it’s easy to bring in someone else on the spur of the moment—just because they’re passing nearby, or sitting in view.

We want our new space to remain dynamic, and keep improving. To that end, we created a “Way We Work” group, which holds regular community check-ins, and crafts new ways to solicit and act on feedback, including anonymous input. Our new office space is not so much built to last as built to change. And that spirit seems to be rubbing off on all of us who work in it.

October 2, 2014

How Thomson Reuters Is Creating a Culture of Innovation

It’s not easy for big companies to innovate. As Steve Blank, Clay Christensen, and many others have pointed out, once firms reach a certain size, most of their resources (and investment dollars) are rightly devoted to executing and defending their existing business model. Moreover, the skills that are cherished and rewarded for achieving current results differ from those that aid in discovery and experimentation, both of which are needed to drive innovation. As a result, fostering a true culture of innovation in big companies is often an aspiration rather than a reality.

If this is the case in your company, then it might be worthwhile to look at the experience of Thomson Reuters, a $12.5B global information solutions company. The company’s strategy of fueling growth through acquisitions served it well for many years – but this approach also reduced the focus on innovation. While many managers were developing new products and services for their own businesses, they were not leveraging innovation across the enterprise, and some were relying too much on acquisitions to drive both innovation and growth.

To reverse this, senior leadership took a number of steps. First they agreed to shift funding from small, incremental acquisitions to innovation. In early 2014, they established a “catalyst fund” – a pool of money that internal innovation teams could use for doing rapid proof of concept on new ideas. The fund was announced on the company’s internal website and teams from anywhere in the businesses were invited to submit their suggestions.

To access the fund, teams had to complete a simple two-page application about their idea, the potential market, and the value to the customer (what problem was being solved). The teams with the most compelling ideas were given an opportunity to present and defend their idea to the innovation investment committee, which included the CEO, CFO, and a few other senior executives. In the first month, five “winners” were announced and then immediately publicized on the Thomson Reuters internal web site. This triggered a great deal of interest, and a steady flow of applications.

The company also took a number of other steps, driven by a newly appointed executive sponsor and a full-time innovation leader, to make innovation a priority. Developed after talking with dozens of people both inside and outside the company, these steps included:

Building innovation metrics (such as number of ideas being considered, and amount of revenue from new products/services) into business unit operating reviews, so business leaders would pay attention to the pipeline and commercialization cycle time of new ideas.

Appointing “innovation champions” in every business – i.e., credible leaders who would help their business presidents implement programs and processes to move the needle on the innovation metrics. For example, the champions created a common terminology for innovation across the company so that everyone referred to the same types of innovation (e.g. product vs. operational) and referenced the same stages (e.g. “ideation” and “rapid prototyping”). They also built an online Thomson Reuters innovation “toolkit” that employees could use to educate themselves about innovation, run innovation events, and work through the process of translating ideas into commercial opportunities.

Creating an innovation “network” on the intranet site where internal entrepreneurs could share their stories and ideas, and get connected to others who were interested in solving customer problems in new ways.

Orchestrating a communications campaign with blogs, articles, and video interviews with internal innovators.

Organizing an “enterprise innovation workshop,” with representatives from every part of the business, to identify and plan ten specific innovations that leverage existing company assets – and implement them in 100 days or less.

In the spirit of innovation, all of these steps were initiated as experiments to focus on learning, adjusting, and figuring out what would work. For example, the innovation metrics were sharpened as the definitions of innovation evolved, and the experience of the first few innovation champions helped clarify criteria for selecting additional ones. Also, all of these steps were carried out with as much transparency as possible, so that all Thomson Reuters employees would not only know what was happening, but could contribute to the effort as well.

The results of all this work have been impressive. Innovation is now one of the hottest topics in the company. The innovation “network” is the most visited site on the company’s intranet, and more than 250 ideas were submitted by employees for consideration at the enterprise innovation workshop, some of which are already being implemented. Several Catalyst Fund projects, which span multiple business units, also are now being prototyped and piloted with customers and most of the businesses have a robust portfolio of innovative ideas that are moving through the pipeline. So although there is still much to be done, and the jury is still out, clearly the momentum for innovation is building.

There is no magic formula for how big companies can reinvent themselves. The innovators’ dilemma is still alive and well and is not easy to overcome. But the experience of Thomson Reuters shows that progress is possible – particularly if leaders use the lessons of innovation to build the innovation culture.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers