Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1358

September 30, 2014

How to Deal with Bullies at Work

You’ve got a difficult, manipulative boss or maybe an intensely competitive and rude colleague. Is it bullying, bad manners, or merely the normal competition of a workplace?

Healthy competition and even some aggression can make for a creative work environment where people push one another to better performance. But a bully can destroy a victim’s core sense of self, and limit their ability to be productive.

So how do you identify what is at work in your workplace? Are there gender differences in perceptions and reaction? What’s the best way to deal with the different scenarios?

In this interactive Harvard Business Review webinar, executive coach Michele Woodward shares the playbook she has developed for identifying and diffusing difficult people in the workplace.

Woodward is a Master Certified Coach, who coaches executives and trains other coaches–she is considered “a coach’s coach.” In this webinar, Woodward provides a step-by-step guide with practical tips for dealing with the difficult people in the workplace.

We Need Better Managers, Not More Technocrats

Digital technology is the biggest agitator of the business world today. Mobile technology, social media, cloud computing, embedded devices, big data, and analytics have radically changed the nature of work and competition. And digital innovations will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Technology has tremendous potential to be the engine of increasing human, organizational, and economic prosperity.

However, digital technology is not the true story. Digital transformation is. Fulfilling technology’s potential will require leaders to recreate the way their institutions operate in a world of digital ubiquity. Leaders need to engage their people in a process of redefining how they work and what their companies do. Digital transformation is therefore the key managerial imperative for today’s business leaders.

So, are large corporations – or, more specifically, the leaders of those firms – ready to face the challenge? Or as Richard Straub of the Peter Drucker Society of Europe puts the question, “are managers equipped – in terms of skills, competencies and courage – to lead us toward the Great Transformation?”

Our research shows that some companies are ready, but they are in the minority. Over the past four years we have studied more than 400 large global firms around the world. We’ve talked with their executives and examined their performance. We’ve worked to understand how they approach all things digital, and what they have achieved. Our overarching conclusion is that, while many companies undertake digital initiatives, most do not manage to bring about transformative change.

There are, however, some inspiring exceptions. The companies we call “Digital Masters” are different. They use digital technology to drive significantly higher profit, productivity, and customer benefits. They take advantage of the transformative potential of digital technology to radically redesign how their organizations operate and compete.

Digital Masters achieve so much more because they maintain a dual perspective on the transformation they must bring about. The first one is the most straightforward: they make smart investments in digital technology to innovate their customer engagements, and the business processes and business models that support them. The second is too often forgotten. Digital Masters build strong leadership capabilities to envision and drive transformation within their companies and their cultures. They innovate the practice of management for a digital world. Along both lines, leadership capabilities are required to turn digital investment into the digital advantage that can lead us to greater human, organizational, and economic prosperity.

So, in a time of brilliant technological advances, the decisive and scarce source of advantage is actually leadership capability. What does this entail? Four key elements stand out in the Digital Masters we studied : their visions, their engagement of employees, the governance systems they establish, and the IT/business synergies they seek.

Digital transformation starts when you create a transformative vision of how your firm will be different in the digital world. Codelco, a Chilean mining company, started its digital transformation by picturing how it could improve its operations with real-time awareness and then automation, including driverless trucks. Its leaders are now envisioning ways to substitute machines for humans in the most dangerous underground environments – changing the economics of the whole company in the process. Codelco’s leaders were not handed a blueprint for the digital future of the mining industry. They drew it. By pursuing their vision they are profoundly enhancing safety and quality as well as productivity.

But vision is not enough. You need to engage employees in making the vision a reality. Peter Drucker was on to this truth many years ago, writing that “your first and foremost job as a leader is to take charge of your own energy and then help to orchestrate the energy of those around you.” Digital technology brings the possibility of real-time employee engagement on a global scale. When used well, new tools can give a voice to your employees, encourage collaboration across organizational boundaries, and foster new ways of working. This is where managerial innovation happens. Pernod Ricard CEO Pierre Pringuet puts it this way: “We needed to create new interactions where they did not previously exist. This networking of collective intelligence has been instrumental to speed up the group’s digital transformation at every level of our organization.”

But, as Drucker also said, “unless commitment is made, there are only promises and hopes, but no plans.” Even with vision and engagement, it is difficult to channel an organization’s energies. That’s where digital governance comes in. In many companies, coordination, and sharing tend to be unnatural acts. Yet, the biggest benefits of digital transformation come exactly from engaging in these acts of cross-silo coordination and sharing. A senior executive in an international banking group highlighted: “Digital impacts firms globally, across traditional silos. It requires more coordination when we are making decisions and conducting actions, compared to the way we do business usually.”

Finally, digital transformation requires executives to break down silos at the leadership level. In the ranks of Digital Masters, business and IT leaders fuse their skills and perspectives so that they drive digital transformation together. Zak Mian, a senior IT executive at Lloyds Banking Group, explains: “What gives me confidence is that although we know we need to continue to adapt and learn, the shared agenda and integration of business and IT teams is now in our DNA.”

Driving digital transformation is not an impossible task or arcane art. It doesn’t require that you hire away Google’s top talent or spend 20% of revenue on technology every year. It does require some level of human capital and investment, of course, but the main requirements are time, tenacity, and leadership. With these, knowledgeable companies can assemble the elements of technological progress into a mosaic not just once, but continuously over time. Digital Masters, in short, keep making digital technologies work for them even though the technologies themselves keep changing.

Regardless of industry or geography, businesses will become much more digitized in the years to come. It’s inevitable. But we do not subscribe to the view that technocrats will therefore become the new managerial masters. Quite the contrary, leadership and human-centric organizations will remain the path to innovation, fulfilling work, and value creation.

So let’s end with another line from Peter Drucker: “What you have to do and the way you have to do it is incredibly simple. Whether you are willing to do it, that’s another matter.” If managers want digital innovation to yield greater prosperity, at the level of their firm or at the level of our economy, the time to start leading digital transformation is now.

This post is part of a series leading up to the annual Global Drucker Forum, taking place November 13-14 2014 in Vienna, Austria. Read the rest of the series here.

When Talent Started Driving Economic Growth

I came out of a standard Keynesian economics education at Harvard College in 1979. It was remarkably closed: from what I could tell, we read Chicago economists, from whom the supply-side movement arose, exclusively to mock them.

But I graduated into an economy that was couldn’t be explained by applying the tools I had been taught. And within three years of my graduation, unemployment hit 10.8%, inflation 13.5%, and the prime rate 21.5%. It was supposed to be it impossible for all of those things to happen at once.

To try to figure out what was really going on, I started reading stuff by the people we were taught in class to mock. In due course, that led me to the work of Robert Mundell, a Canadian who would go on to win a Nobel Prize in 1999. I even went to see him in his bohemian New York apartment, filled with his abstract art (painting seemed to interest him more than economics at the time).

That meeting in turn led me to a fascinating 1978 book called The Way the World Works by Jude Wanniski, a journalist. Mundell and Wanniski had better descriptions of what was happening in the economy than did my Keynesian professors, so I applied that lens to better understand the economy as it unfolded in the 1980s.

Looking back, it’s become clearer to me just how situated in time the supply-side movement was. It was no accident that Arthur Laffer drew his famous curve on a napkin in 1974, that Wanniski wrote his book in 1978, and that the US tax system changed totally in 1982. The mid-1970s was an inflection point in American history: the moment when talent became recognized as the engine of economic growth. And with that recognition, economic power shifted to its suppliers. Some of the highlights:

In 1975, baseball players fought for and were awarded free agency by arbitrator Peter Seitz — and salaries for athletic talent across all professional sports quickly skyrocketed.

In 1976, the famous LBO firm KKR was formed and starting charging its clients 2% of assets under management and 20% of the upside they created for their clients, opening the door to massive wealth accumulation for high-flying fund management talent.

Also in 1976, Michael Jensen and William Meckling wrote their famous article that set loose a frenzy of stock-based compensation for executives that would made todays CEOs richer than the wildest dreams of their 1960s counterparts.

In 1977, the movie Star Wars was released, with sequels following in 1980 and 1983. In the wake of this epochal hit producer George Lucas negotiated an unprecedented deal from Paramount Pictures for 50% of the gross profit (i.e. before overhead and marketing and distribution costs) of his next project, the 1981 blockbuster Raiders of the Lost Ark, in exchange for directing and producing the movie, which made him a multi-billionaire and changed the balance of power between stars and studios.

The journey of supply-side economics from a napkin in 1974 to the White House in 1980 did not take place in a vacuum. It took place in the fertile environment of the 1970s when the world woke up to the importance of talent and its incentives. And when the world did, talent responded: “You are right. I deserve more, in fact lots more.”

As with all theoretical revolutions, supply-side economics revealed its shortcomings when put to use and its star has now faded. But it held sway in the halls of power in the early days of the talent revolution — a decade whose seismic shift is still sending out aftershocks.

Xbox Polling and the Future of Election Prediction

For generations, pollsters have used probability polling (think of the Gallup polls quoted on the nightly news) as their go-to method to forecast the outcomes of elections. But cost increases and concerns about accuracy have called the method into question. A new form of polling called non-probability sampling — opt-in surveys on the internet, prediction markets, and even polls on gaming systems — has emerged as an improvement, and a viable replacement.

First, let’s take a look at probability polling, which works like this: ask a random sample of likely voters who they would vote for if the election were held that day, and the answer is almost as accurate as asking everyone. This method has worked relatively well in countless election cycles, but it’s growing more difficult to receive accurate results. One reason: the rise of cell phones. For a period in the 1980s nearly all likely voters owned a land-line; now the catalog of likely voters is spread over landlines and cell phones, or both, which makes it hard to figure out what the sample really is. In other words, where are all of the likely voters? The next problem is non-response error. Not all likely voters are equally likely to answer the poll, if contacted. This error is due to simple things like differences between demographics (e.g., some groups are more likely to answer calls from unknown numbers) and more complex things like household size. In other words, which likely voters are responding to polls, and do they differ from likely voters who don’t?

There are serious selection issues with non-probability samples as well — just like probability samples, they are prone to coverage and non-response errors — but the data is so much faster and cheaper to acquire. For example, in 2012, my colleagues and I collected opinions on the U.S. Presidential election from Xbox users by conducting a series of daily voter intention polls on the Xbox gaming platform. We pulled the sample from a non-representative group of users who had opted-in to our polls. In total, over 350,000 people answered 750,000 polls in 45 days, with 15,000 people responding each day and over 30,000 people responding 5 or more times. At a small fraction of the cost, we increased time granularity, quantity of response, and created a panel of repeated interactions.

But the raw data still needed to be turned into an accurate forecast. With our Xbox data, we first needed to create a model that incorporated the key variables of the respondents. We did this by determining the likelihood that a random person, from any given state, would poll for Obama or Romney on any given day, based on state, gender, age, education, race, party identification, ideology, and previous presidential vote. Then, we post-stratified all possible demographic combinations, thousands per state, over their percentage of the estimated voting population; for transparency we used exit poll data from previous elections. Finally, we transformed the Xbox data into an expected vote share — by detailed demographics, and probability of victory, for all states.

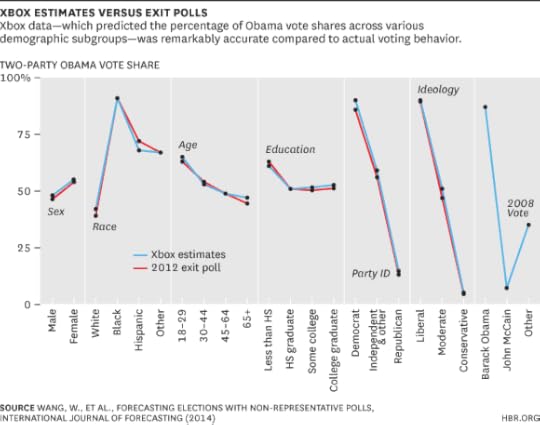

In the below figure, you can see the accuracy of the Xbox pre-election estimates compared to exit-poll data.

As you can see, our forecasts were accurate — even compared with the best aggregations of the traditional polls — and they provided detailed demographic insight as well. Further, we were able to gain a new understanding of the movement (or lack thereof) of swing voters, because we had so many repeated users. The accurate forecasts, new relevant insights, and ability to easily update daily, all came at a much lower cost than traditional probability polling.

Yet there are meaningful groups of researchers that cling to the past, even as more papers confirm our findings. Their argument is that declining response rates don’t affect results in a major way, so why worry and innovate?

Yes, it is possible that our Xbox polls would be slightly less accurate in other domains or with smaller samples. But within a few years, there’s no doubt that traditional polls will lose their statistical power and become less accurate.

Xbox polling, and other forms of non-probability polling, will be an increasingly crucial tool for campaigns and advertisers in future elections. Campaigns have the capacity to target detailed demographic groups, or individuals, with messages specifically designed for them. And, because non-probability polling allows for continually updated forecasts for specific demographic groups, they can be even more efficient at targeting and delivering those messages.

Do Academically Marginal Students Benefit from College? The Data Says Yes.

A study of Florida high-schoolers whose grades were just good enough for admission to a public university shows that higher education provided significant financial benefits for these students: 8 to 14 years after high school, their earnings were 22% higher than those of peers who hadn’t gone to college, with male students showing the largest gains, says Seth D. Zimmerman of Yale. These benefits outstrip the costs of college attendance, he says.

Scotland’s Future Is Bright; the UK’s Might Not Be

In the run up to the Scottish independence referendum, the large-country voices that dominated the international discussion converged on a near consensus that small countries are inferior to larger ones, with worse prospects and higher risks; that the pro-independence movement’s motivation was cultural nationalism and an angry defensiveness against the world; and that independence would do significant damage to an open, liberal international order.

When Alan Greenspan, Paul Krugman, and Niall Ferguson all agree on something, it’s a sign that the consensus is either very right — or very wrong. Commentators from big countries would have done well to consider the experiences of the many successful small advanced economies in Northern Europe and Asia. To be sure, there are some less successful small countries as well. But there are dangers in adopting a binary, black and white perspective on the benefits of national scale.

Correctly interpreting the Scottish debate matters as we think ahead. What should we now expect in Scotland and the UK? And will there be more independence movements elsewhere, with disruptive changes in the international economic and political system? I’ll offer some small-country perspectives on these issues.

Scotland’s economic future is bright. Gordon Brown said during the campaign that Scotland’s fight should not be with London but with globalization. There is clearly something to this; while declines in manufacturing employment have hit the Scottish economy hard, manufacturing has also been in decline as a share of GDP across the advanced economies over the past 25 years. But neither is this the full story. There was no UK strategy to enable Scotland to develop alternative engines of growth, as other small advanced economies were able to do. Scotland has been trying to compete in the global economy with one arm tied behind its back.

The key issue has been the absence of micro-economic policy levers that Scotland can use to better position itself. Although there was heated debate about whether Scotland would continue to use the British pound, this is a second-order issue (most successful small countries do not have a freely floating exchange rate). What does matter is the ability to set economic policy in a way that reflects local context.

Scotland has the intrinsic qualities of successful small advanced economies: an educated population, social capital, and competitive firms. And with the referendum giving it greater ability to pursue a coherent economic strategy, it will likely do even better.

The UK’s future in the EU is uncertain. The consensus view seems to be that the UK is now more likely to stay in the European Union. This optimism is partly because of arithmetic, as Scottish voters are more pro-EU. I hope that this is right. Both the UK and the EU would be significantly diminished if the UK left.

But the events of the past several weeks create room for doubt. At a tactical level, the apparent carelessness with which London treated the Scottish vote until the last weeks raises questions as to whether the government can lead a serious national debate about the UK’s future in Europe in the context of a possible referendum. And at a deeper level, the Scottish debate revealed that the UK thinks of itself as a large country, which it is not. Globalization has reduced the effective size of countries, with external forces limiting the degree of domestic policy autonomy. As small countries know well, independence is never complete and trade-offs need to be made.

For the UK, regional integration is a vital part of its ability to project economic and political power. Although the UK foregoes some independence as an EU member, leaving the EU would not restore fully autonomous status. As soon as the UK began to negotiate free-trade agreements, it would find out that is not independent. But these limits on its independence do not seem to be recognized in the UK debate. To the extent that the UK thinks about itself as a large country, it is more likely to make incorrect strategic decisions about Europe. Because of this, I would put the odds on a British exit at above 50/50.

A wave of independence movements is unlikely. There has been much excited talk about the wave of independence movements that will follow the Scottish vote. But I think these predictions are overblown for two reasons.

First, Scotland was a special case. There were significant devolved powers in place, an existing government and administrative machinery, specific cultural and political history, and an agreement by the UK government to the terms of the referendum. These conditions apply in very few other prospective countries.

Second, the Scottish debate has reminded everyone that being a successful small country is demanding. Although the challenges of being a small country were substantially exaggerated in the Scottish debate, small countries do face hard economic realities: higher risk exposures, costs, and market disciplines. Independence is no panacea, particularly in a more turbulent, complex world. Not every small country succeeds.

As a result, although there are powerful centrifugal forces at work as globalization puts existing political structures around the world under pressure, for the most part this will not look like Scottish-style independence campaigns. Regions and cities will continue to get additional powers (as in the U.S.) and decision-making on many issues will become more local. But where the motivation for independence is at least partly economic as opposed to cultural, the economic realities are generally likely to mean devolution short of full independence. It is instructive that support for Welsh independence plummeted after the Scottish vote, I suspect partly because of an increased awareness of the challenges of full independence.

The international system is weakening – but large, not small, countries are the problem. It is clear that many countries are turning inwards, that there is declining public support for an open global system, and that international institutions, such as the WTO, are struggling. But it is a stretch to see the Scottish independence referendum as part of this backlash against globalization.

Indeed, for Scotland to succeed, it needs to be even more deeply engaged in the global economy. Scotland sees this, with clear declarations of intent in the campaign to be open to the rest of the UK, the EU, NATO, and so on. More broadly, successful small countries are highly open and internationally engaged, have been deeply engaged in the process of globalization over the past 25 years, and are active supporters of an open, rules-based, liberal order. To understand the problems with globalization, it is more useful to look around the G20 table — not at small economies.

A key challenge for the global system is that big countries no longer want to underwrite it, and are not adapting themselves at home to a changed environment. Indeed, a recent Pew survey showed little support for free trade and investment in large advanced economies. Large-country commentators on Scotland who worry about nationalism and insularity may want to spend more time talking about challenges closer to home.

Overall, the Scottish debate should remind us that current institutions, approaches and borders are under significant stress. Disruptive changes in the global economic and political system over the past few decades (which will likely continue), together with the declining effectiveness of current policy approaches, combine to create pressures. Balancing integration and interdependence with the demands of democratic legitimacy and local context will be a demanding challenge. There will be experimentation and innovation as people figure out the best way forward. And if the past few decades are any guide, small nations will be among those leading the way.

September 29, 2014

Beware the Analytics Bottleneck

Within the next three years there will be over 20 billion connected devices (e.g. oil pipelines, smart cities, connected homes and businesses, etc.) which can empower the digital enterprise — or intimidate them. With the pace of digital “always on” streaming devices and technology innovation accelerating, one might think technology would continue to pose a challenge for businesses. Historically, new technologies from the mainframe to client server and ERP — while enabling organizations to pursue new business goals — became a bottleneck to progress. This is due to constraints like lengthy implementation processes and inflexibility to adapt as business conditions changed. Turns out that isn’t the case today. There is a new, even more elusive, bottleneck: the organization itself and its ability to adopt and adapt big data and analytics capabilities.

Based on our work with clients in a variety of industries from financial services to energy, here are three ways we’ve seen organizations embrace the analytics opportunities of today and transform from being the constraint into being the change agent for their company’s future.

Don’t be overwhelmed — start slower to go faster: Given the ferocious pace of streaming data, it can be challenging for many organizations to glean data insights at the same speed and determine the right data-driven decisions and actions to take. To avoid getting overwhelmed by all the data and the possible opportunities it could uncover, companies should slow down and just focus on the things that matter — it’s much easier to focus on resolving five issues that could truly make a difference instead of 500 issues that might help the business.

Once the shortlist of focus areas is determined, organizations can then more effectively chase their desired outcomes by doubling down their analytics efforts in data automation and embedding insights in decision processes to help achieve their wanted results, quicker. This should also be done in tandem with continuing to drive analytics adoption in the business for an even bigger benefit.

An upstream energy equipment manufacturer, for example, used this approach to better understand the amount of time production equipment sat idling. The company knew there was huge value in solving the idle problem, but it could not do so leveraging traditional technologies as the data volumes were too large (i.e. 300,000 locations, approximately 20 machines per location, 2-300 data points per machine, and 45 millisecond sensor sample rates). Using a Big Data Discovery platform and methodology, within 10 weeks the team was able to show more than $70M in savings from analysis from a subset of the locations and could analyze the data at high speeds (e.g. 13,500 sites, 20 TB, 15 seconds to render).

Technology doesn’t have to be exposed (Keep the complexity behind the curtain): Organizations shouldn’t be reticent to explore new technologies and experiment with their data to improve the effectiveness of their analytics insights for key decision processes. Machine learning, or the growing set of data discovery and analysis tools used to uncover hidden insights in the data, is a sophisticated technology that can do just this. Its data exploration capabilities and simplicity are also becoming necessities to ensuring competitiveness in the connected world.

Machine learning techniques can aid a company to: learn from past behavior and predict behavior of new customers (e.g. risk models to predict consumer risk to default), segment consumer behavior in an optimized, market friendly fashion (e.g. customer lifestyles modeled from geo-location data on cellphones), or conduct crowd simulation models where each customer’s response to a reward is modeled. This is just a snapshot of possibilities; many more types of outcomes from machine learning are also possible.

For example, one retail bank applied machine learning to its customer analytics and achieved a 300% uplift on sales campaigns compared to a control group. Despite this lift, the bank was experiencing relatively slow adoption in the retail channel with many branch managers still using traditional methods of relationship selling. To improve the adoption rate the bank focused on a change program that dumbed down what qualified leads meant and also showed the managers the WIIFM (“What’s in it for me?”) approach to show how this would help them achieve their goals.

Make faster decisions for faster rewards: It’s important for businesses to sense, analyze, interpret and act fast on the data insights as competitive advantages will likely be more fleeting than long lasting in the hypercompetitive world. With this, we are seeing a fundamental shift in strategic decision making that is powered by big data discovery, a capability that accelerates the time to insight.

As an example, a large bank used a data discovery capability to gain deeper insight into their customer experience strategy and understand why there was a drop off in customer satisfaction. The data discovery analysis took weeks instead of months, where a team of data scientists, functional experts and business analysts worked to tag, filter and find correlations in the data, and how it differed by customer segments. The analytics team discovered that the bank’s most affluent customer segments were the most digitally savvy, and they were dissatisfied with their digital experience, online and on their mobile devices. The bank thought service fees were the issue, and while they were a strong issue overall across all customers, it wasn’t the most important issue for their most profitable customers. As a result, the bank changed their customer experience strategy by altering their approach to service fee refunds and enabling wealth advisers to connect with customers digitally.

It’s a reality: Data is going to keep growing and technology options will follow the same trajectory. Organizations shouldn’t run from this new digital reality, but learn to embrace it by adopting and adapting their analytics strategies to remain competitive. By applying the power of data and analytics techniques such as machine learning, a firm can make smarter, faster decisions for their business and its customers, and actively disrupt their industry.

The Bash Bug Is a Wake-Up Call

By now we’ve all heard about the immediate threat posed by the Bash bug, which a security researcher discovered last week. Also known as the Shellshock bug, the software flaw exploits a vulnerability in a standard piece of software code called the Bash Shell, whose functions give users command over computer systems that are based on Linux and Unix. That means attackers can take control of your systems and run any command they wish.

Bash is a far bigger threat than Heartbleed. Heartbleed gave hackers access to personal data, like passwords. But Bash threatens the emerging Internet of Things—the global system of smart, connected products and services. That may includes GE jet engines, wind turbines, and MRI machines; Apple’s MacBooks; Amazon’s ecommerce systems; JPMorgan Chase’s accounts; Nest thermostats, and even your DVR. All these can now be controlled by attackers. The good news is that companies, open source communities, and government organizations are rushing to fix the problem and solutions have already been posted.

Bash won’t be the last threat of this magnitude, and that fact should force us to address a simple fact: The Internet of Things enables new levels of convenience and efficiency, but its comprehensive connectivity also exposes households, companies, and whole economies to attack. We can’t address every Bash bug-type discovery as a one-off. Company executives, open-source software community leaders, and government organizations have to get their act together. They must join forces and work proactively to create systems and processes that anticipate weaknesses, defend against attacks and enable rapid, coordinated fixes.

We need three levels of response to get ahead of these problems. First, all companies are at risk. Executives need to take this seriously and network security has to have a place on the CEO’s and Board of Directors’ agenda. Just as we need financial audits to ensure the integrity of business, we need continuous security audits of all IT-enabled products and services to ensure that customers and businesses are not at risk. This may even mean redesigning systems to enable automatic updates and easy lockdowns in case of an emergency.

Second, organizations need to create an emergency response team and plan that can swiftly react and solve problems once vulnerabilities are detected. It should work like any effective emergency preparation: Executives should plan for worst-case scenarios and run their organizations through the drills to ensure that they’re ready to handle problems as they may arise. Experience has shown that this can’t be relegated to the lower levels of the IT organization. Instead executives from all functions need to be involved in the response plan.

Third, companies, open source community leaders, and government organizations need to coordinate their activities to proactively detect weak spots in our digitized and networked devices, services, and infrastructure. The vast majority of the world’s internet and software infrastructure relies on solutions developed in open-source software communities. Over the past two decades these communities of developers, composed of volunteers and firm-sponsored employees, have proved themselves brilliant at creating code. However, no software system is perfect and open source code — like proprietary solutions — can have mistakes, omissions, or simply not be capable of evolving with ever-changing networked computing systems. Open-source software works on the principle of “many eyes can find any bug,” however, both the heartbleed bug and the shellshock bug allowed entry into core systems because there were simply not enough people looking critically at open-source code to detect and defend the networks.

Now is the time for companies, communities, and governments to proactively add resources to the core computing infrastructure and test it for vulnerability in a systematic fashion. While academic and government organizations like CERT (at Carnegie Mellon University) are doing an admirable job in raising awareness about security threats, more must be done. Taking a cue from the banking system, the computing industry needs to develop an approach that prioritizes proactive stress-testing, detection, and updating to anticipate problems and prevent them from occurring. This proposal is not so far out of reach. Already, competitive companies cooperate in various open-source foundations (e.g. Linux, Apache, Perl) to create software solutions. To address the security problem will take similarly effective cooperation and organization among the participants, but it also requires the will to succeed. There is too much at stake not to do it.

The Ways Big Cities Think About Large-Scale Change

Change on a grand scale requires people to come together in new and different ways, and to reimagine what’s possible. This kind of change is hard, but it’s not impossible.

In 2010, Living Cities, a long-standing collaborative of 22 of the world’s leading foundations and financial institutions, created the Integration Initiative to accelerate the pace of change in U.S. cities. We worked with five cities tackling seemingly intractable challenges such as urban revitalization in Detroit and education and health in Newark.

In our work with America’s cities and a cross-section of public and private sector leaders, we are learning a lot about what works — and what doesn’t — to lead and drive this kind of change. But these aren’t just lessons for the social sector. Much of what we’ve learned is relevant to leaders of any type of organization or partnership that want to catalyze change in the face of complex challenges.

Get the right players to the table. Change happens only when the right mix of partners, with the right experience, knowledge, and power are at the table. The problems that the cities in our initiative were taking on could not be solved by one individual, institution, or sector. Too often, actors that were fundamental to achieving the desired results were not yet involved in existing efforts — that’s why the efforts weren’t working. We asked cities to start from the results that they wanted to achieve, and then to determine who needed to be at the table in order to achieve them. Often, this meant bringing people together who were not used to working together.

We saw the greatest success when tables identified strong chairs who had credibility in multiple sectors, were willing to push the group to prioritize, and were committed to changing how their own institutions worked in order to push others to do the same. Indeed, achieving their goals required significant behavior change from multiple players who didn’t necessarily see themselves as part of the same systems even though they served largely the same families and neighborhoods. For example, although a school superintendent and the head of a community development bank have historically had little occasion to talk to each other, they both play an important role in connecting underserved communities to jobs and essential services such as education, training, child care, health care and housing, and ensuring that those opportunities exist in the first place.

In Cleveland, our work was focused on leveraging the hiring power of universities and hospitals to create economic opportunity for neighboring residents. Senior leaders from all of the universities and hospitals came together, in an unprecedented collaboration, to create universal employee metrics that tracked employment goals and outcomes across the institutions so that they could better understand the hiring landscape, and design interventions to better equip residents for jobs.

Reimagine roles. Not only do you need to bring together folks with diversity of thought and experience, but those leaders also need to challenge long-held orthodoxies that can limit progress. Being open to reimagining roles allows all of the partners and resources at the table to be put to their best use.

In Minneapolis and St. Paul, local government and foundations took on roles that were far from what is generally expected of them. To realize The Corridors of Opportunity’s goal of ensuring that the imminent build out of the regional transit system provided benefits to low income people beyond access to public transportation, the Metropolitan Council, a quasi-governmental planning agency, established a $5 million annual grant program and a new five-person office to oversee projects that would provide access to jobs, housing, health clinics, child care and other essential services. The funding and oversight of these projects was a role typically played by philanthropy and nonprofits. But the partners knew that having the public sector lead this effort would be more sustainable than a loose collaborative of nonprofits with the need to constantly fundraise. And The Saint Paul Foundation filled financing gaps, using loans, loan guarantees and even equity investments — investments commonly associated with banks or other private investors, but likely too risky for traditional lenders until there was a more proven track record.

Build, measure, learn, and declare. The most successful cities have adopted a lean “build, measure, learn” approach. They use data to measure, in real time, whether their indicators are trending up, learn whether their approaches are working and then stay or change course as needed.

This is not an easy task. Standard performance metrics for these big audacious outcomes do not exist. For example, there is no agreed-upon way to measure urban revitalization. One promising example here, however, is StriveTogether’s Theory of Action for bringing about large-scale change in education, from cradle to career. The theory of action, which has been adopted by cross-sector partnerships in cities across the country over the past two years, is a specific articulation of quantitative, measurable outcomes or ‘community level outcomes and core indicators’.

The cities have taken this approach one step further. A willingness to “declare” or speak publicly about the desired outcomes is transformative because it puts all partners on the hook for the results. Through “learning communities” all five participating cities come together to share successes and failures, and to collectively grapple with questions. Where partners were reluctant to publicly commit to or prioritize outcomes, it took much longer to move from talk to action.

There is no formula or roadmap to follow for large-scale change. While each approach will be different, we’ve learned that a willingness to challenge the status quo, making sure the right people are at the table, using data to continuously improve, and making a public commitment to goals is essential to success.

How Companies Can Learn to Make Faster Decisions

SpaceX had a problem. Managers at the aerospace manufacturer wanted to make faster decisions for one of their big clients — NASA — by finding alternatives to the high volume of meetings and cumbersome spreadsheets used for tracking projects. Initially, NASA sent a fax (yes, a fax) whenever they had a query, which SpaceX added to a list of outstanding questions. The company then assembled a weekly 50-person meeting to review product status information contained in spreadsheets, addressing each question individually before sending the responses back to NASA.

SpaceX’s dilemma is not an uncommon one. In today’s organizations, the speed of decision making matters, but most are pretty bad at it. One-third of all products are delivered late or incomplete due to an inability or delay in decision-making, according to research from Forrester Consulting and Jama Software. Others at Gartner cite “speed of decision making” as the primary obstacle impacting internal communication. No doubt you’ve been part of a team that waited… and waited… for a higher-up to make a decision before you could resume your work.

These small delays compounded over thousands of decisions soon becomes death by a thousand cuts. According to Forrester, for every hour a product teams spends on heads-down work, they spend 48 minutes waiting on decisions. That equates to more than 3.5 hours of “wait time” in an average eight-hour work day. If a company cuts wait times in half, it can gain more than $370,000 annually in productive time across a 25-person team. This doesn’t even account for the bigger opportunity captured by a company if they can avoid delivering products late to market.

The good news is that companies are finding ways to make better, faster decisions.

SpaceX increased communication in order to speed up their process. Using collaborative technology, NASA now has direct visibility into each project and can identify which SpaceX engineers are working on a specific component. Importantly, they can also start a conversation with these engineers in order to make decisions in real-time. The collaboration system allowed SpaceX to cut its average wait time for defining product requirements by 50% and eliminated the costly weekly four-hour status meeting.

Something similar happened at a large manufacturing firm, which set out to reduce wait times associated with development of its semiconductors. At this company, each product had 250 variations for global distribution, so the complexity quotient was high. Most of the review time was spent in a typical linear process, waiting for one person to make a decision or finish their part before the next person could start work. This approach was incredibly time consuming, requiring three people to drive the review process over a six-month period.

To speed this up, the company implemented advanced collaboration technologies to create review processes that would work in parallel with one another. Rather than waiting for a decision before the next person could begin work, the company brought many people into the process earlier in the cycle so several decisions could be made simultaneously. The collaboration system contained everything related to the product in a central location and used constructs similar to social networking — rather than emails and spreadsheets — to communicate and manage the complexity in real time. This new approach allowed everyone to look beyond their discreet tasks by providing more context about the entire project. As a result, the company fostered more discussions between individuals working on related parts of the product and employees ultimately made faster and better decisions.

These deeper insights also allowed engineers to identify instances where work being done by one team was duplicative or related another team, creating opportunities to reuse core design elements across multiple product lines. It also helped them avoid the need to make many individual, time-consuming decisions in isolation.

The results were dramatic: The global company reduced the review cycle to just one person owning the process, which took a single month. Prior, it took three people and six months, so that’s an 18-fold, or 90% reduction, in time.

This firm and SpaceX, which are clients of Jama Software, both adopted an approach of purposeful collaboration using technology to streamline decision-making. And behind both approaches are a few key tenants that can apply to any company:

Offer a shared vision. Many companies relegate team members to perform specific tasks or only communicate certain components of information to various groups, without providing the big picture. This creates a very limiting, myopic view. SpaceX wanted to provide better communications with NASA so they brought them deeply into the process by sharing decisions as they were being made. By offering everyone on the team — even when it’s thousands of people across different companies – a shared vision, all stakeholders can be in synch and employees can deliver better results.

Encourage more problem solving. Managers should foster an environment where employees seek information to answer questions themselves, rather than sitting back waiting to be assigned their next task. Employees should communicate and collaborate freely with one another, locating experts in certain areas of focus so they can gain insights on their own. When a product designer at the semiconductor company had a question, for example, she knew exactly who was working on the related test case or software specification so she could get her questions answered immediately rather than waiting for information to be sent to her.

Make decisions in parallel. Decisions at organizations are typically made in a linear fashion, but it doesn’t have to be that way. When teams get stuck in the old way of doing things — Decision A first, then Decision B, then Decision C and so on — we create passive teams. In the case of developing and delivering semiconductors, the company enabled multiple teams to simultaneously make decisions related to a product, and insights from one team could help others make faster decisions.

New collaboration systems that engage teams in the decision making process can be effective, even transformative, particularly for companies building complex software and technology products. However, improving decision-making relies on much more than implementing new technologies — it also requires a significant cultural shift. Managers need to let go of the command-and-control approach wherein they only disperse the necessary information to specific teams for fear they may become distracted by additional insights. Rather, they should empower employees by providing them with all the information and trust them to make the right decisions.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers