Ryan Holiday's Blog, page 19

April 28, 2020

Life Comes at You Fast. So You Better Be Ready.

In 1880, Theodore Roosevelt wrote to his brother, “My happiness is so great that it makes me almost afraid.” In October of that year, life got even better. As he wrote in his diary the night of his wedding to Alice Hathaway Lee, “Our intense happiness is too sacred to be written about.” He would consider it to be one of the best years of his life: he got married, wrote a book, attended law school, and won his first election for public office.

The streak continued. In 1883, he wrote “I can imagine nothing more happy in life than an evening spent in the cozy little sitting room, before a bright fire of soft coal, my books all around me, and playing backgammon with my own dainty mistress.” And that’s how he and Alice spent that cold winter as it crawled into the new year. He wrote in late January that he felt he was fully coming into his own. “I feel now as though I have the reins in my hand.” On February 12th, 1884 his first daughter was born.

Two days later, his wife would be dead of Bright’s disease (now known as kidney failure). His mother had died only hours earlier in the same house, of typhoid fever. Roosevelt marked the day in his diary with a large “X.” Next to it, he wrote, “The light has gone out of my life.”

As they say, life comes at you fast.

Have the last few weeks not been an example of that?

In December, the Dow was at 28,701.66. Things were good enough that people were complaining about the “war on Christmas” and debating the skin color of Santa Claus. In January, the Dow was at 29,348.10 and people were outraged about the recent Oscar nominations. In February, when the Dow reached a staggering 29,568.57, Delta Airlines stock fell nearly 25% in less than a week, as people argued intensely over a message from Delta’s CEO about passengers reclining their seats. Even in early March, there were news stories about Wendy’s entering the “breakfast wars” and a free stock-trading app outage that caused people to miss a big market rally.

And that was just in the news. Think about what you busied yourself with at home during that same period. Maybe you and your wife were looking at plans to remodel your kitchen. Maybe you were finally going to pull the trigger on that Tesla Model S for yourself—the $150,000 one, with the ludicrous speed package. Maybe you were fuming that Amazon took an extra day to deliver a package. Maybe you were frustrated that your kid’s room was a mess.

And now? How quaint and stupid does that all seem?

Depending on the day you look, years of market gains have now been taken back. 47 million people are projected to be added to the unemployment rolls in the US. The death count from what was dismissed as a mere respiratory flu and the left’s latest hoax is now inching towards 170,000 and there are millions more confirmed cases worldwide. There have been runs on supplies. Hospitals are maxing out ventilators. The global economy has essentially ground to a halt.

Life comes at us fast, don’t it?

It can change in an instant. Everything you built, everyone you hold dear, can be taken from you. For absolutely no reason. Just as easily, you can be taken from them. This is why the Stoics say we need to be prepared, constantly, for the twists and turns of Fortune. It’s why Seneca said that nothing happens to the wise man contrary to his expectation, because the wise man has considered every possibility—even the cruel and heartbreaking ones.

And yet even Seneca was blindsided by a health scare in his early twenties that forced him to spend nearly a decade in Egypt to recover. He lost his father less than a year before he lost his first-born son, and twenty days after burying his son he was exiled by the emperor Caligula. He lived through the destruction of one city by a fire and another by an earthquake, before being exiled two more times.

One needs only to read his letters and essays, written on a rock off the coast of Italy, to get a sense that even a philosopher can get knocked on their ass and feel sorry for themselves from time to time.

What do we do?

Well, first, knowing that life comes at us fast, we should be always prepared. Seneca wrote that the fighter who has “seen his own blood, who has felt his teeth rattle beneath his opponent’s fist… who has been downed in body but not in spirit…”—only they can go into the ring confident of their chances of winning. They know they can take getting bloodied and bruised. They know what the darkness before the proverbial dawn feels like. They have a true and accurate sense for the rhythms of a fight and what winning requires. That sense only comes from getting knocked around. That sense is only possible because of their training.

In his own life, Seneca bloodied and bruised himself through a practice called premeditatio malorum (“the premeditation of evils”). Rehearsing his plans, say to take a trip, he would go over the things that could go wrong or prevent the trip from happening—a storm could spring up, the captain could fall ill, the ship could be attacked by pirates, he could be banished to the island of Corsica the morning of the trip.

By doing what he called a premeditatio malorum, Seneca was always prepared for disruption and always working that disruption into his plans. He was fitted for defeat or victory. He stepped into the ring confident he could take any blow. Nothing happened contrary to his expectations.

WATCH: Ryan Holiday speaks about premeditatio malorum

Second, we should always be careful not to tempt fate.

In 2016 General Michael Flynn stood on the stage at the Republican National Convention and led some 20,000 people (and a good many more at home) in an impromptu chant of “Lock Her Up! Lock Her Up!” about his enemy Hillary Clinton. When Trump won, he was swept into office in a whirlwind of success and power.

Then, just 24 days into his new job, Flynn was fired for lying to the Vice President about conversations he’d had with Sergey Kislyak, the Russian ambassador to the United States. He would be brought up on charges and convicted of lying to the FBI.

Life comes at us fast… but that doesn’t mean we should be stupid. We also shouldn’t be arrogant.

Third, we have to hang on. Remember, that in the depths of both of Seneca’s darkest moments, he was unexpectedly saved. From exile, he was suddenly recalled to be the emperor’s tutor. In the words of the historian Richard M. Gummere, “Fortune, whom Seneca as a Stoic often ridicules, came to his rescue.”

But Churchill, as always, put it better: “Sometimes when Fortune scowls most spitefully, she is preparing her most dazzling gifts.”

Life is like this. It gives us bad breaks—heartbreakingly bad breaks—and it also gives us incredible lucky breaks. Sometimes the ball that should have gone in, bounces out. Sometimes the ball that had no business going in surprises both the athlete and the crowd when it eventually, after several bounces, somehow manages to pass through the net.

When we’re going through a bad break, we should never forget Fortune’s power to redeem us. When we’re walking through the roses, we should never forget how easily the thorns can tear us upon, how quickly we can be humbled. Sometimes life goes your way, sometimes it doesn’t.

This is what Theodore Roosevelt learned, too.

Despite what he wrote in his diary that day in 1884, the light did not completely go out of Roosevelt’s life. Sure, it flickered. It looked like the flame might have been cruelly extinguished. But with time and incredible energy and force of will, he came back from those tragedies. He became a great father, a great husband, and a great leader. He came back and the world was better for it. He was better for it.

Life comes at us fast. Today. Tomorrow. When we least expect it. Be ready. Be strong. Don’t let your light be snuffed out.

The post Life Comes at You Fast. So You Better Be Ready. appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

April 21, 2020

All You Need Are a Few Small Wins Every Day

We have a false picture about how success happens. Because we often see only the results and almost never the process of things, we tend to think that the finished product—a book, being in shape, being wise—is impressive, and therefore the process by which that event was created must have been equally brilliant.

In fact, it’s usually the opposite.

Success, like the proverbial sausage, is much less pretty when you see how it’s made.

I make no pretensions about being wise or in shape, but I do know books well. I also remember equally well how I thought authors created them back when I was solely a reader. I assumed it must be some magical, special process.

If only that were so…

The single best rule I’ve heard as a writer is that the way to write a book is by producing “two crappy pages a day.” It’s by carving out a small win each and every day—getting words on the page—that a book is created. Hemingway once said that “the first draft of anything is shit,” and he’s right (I actually have that on my wall as a reminder).

While it would be wonderful if books could be created through raw genius, if we could spit fire each time we sat down at the keyboard, that’s not how it goes. Instead, the best writers have routines that put their asses in the chair and create opportunities to move the ball slightly forward each day. Enough of these small actions strung together—reviewed, dissected, iterated upon—produces publishable work.

It might even produce things that sell like crazy or take people’s breath away.

That might be less glamorous, but the upside is that it means it’s much more accessible.

Businesses are also built by humble means—good ones, anyway. Sure, the WeWorks of the world get all sorts of attention for their ambitious plans for taking over the world, and their stratospheric valuations can make it seem like a viable strategy. But just as often, these companies collapse or implode, and in the end not even the bones or foundation remain… because they never existed in the first place. They were fictions, created in a flash while no one was watching.

Trees that grow tall and live long grow slowly—especially at first—but then grow steadily. They may be underground a long time, and a vulnerable sapling for longer still, but like a good idea or a new habit, once the roots are in, they’re hard to dislodge. So it goes with businesses and net worths. Plutarch tells the story of a rich Delian ship-owner who was asked how he built his fortune. “The greater part came quite easily,” he said, “but the first, smaller part took time and effort.”

How does that work?

Creating anything of consequence or magnitude requires deliberate, incremental and consistent work. At the beginning, these efforts might not look like they are amounting to much. But with time, they accumulate and then compound on each other. Whether it’s a book or a business or an anthill or a stalagmite, from humble beginnings come impressive outcomes.

A friend of mine, Pete Williams, once surprised me with a stat a few years ago: 10% improvements across just, say seven, categories in a business would combine to mean doubling your profits.

This is the approach that I apply to my writing, to my business, and my personal life: When I am not creating, I look for areas I can make small tweaks. How can the subject lines of my emails be better? Could my art be better? Where do I have leaks (of time, money, energy) in my business? Are there habits or systems that are holding me back? What groundwork can I lay now that might come in handy in the future? What investments can I make? What deals can I make (or renegotiate) to improve the health of my finances or the quality of my products?

In one of his most famous letters to Lucilius, Seneca gives a pretty simple prescription for the good life. “Each day,” he wrote, “acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes, as well and after you have run over many thoughts, select one to be thoroughly digested that day.”

One gain per day. That’s it.

George Washington’s favorite saying was “many mickles make a muckle.” It was an old Scottish proverb that illustrates a truth we all know: things add up. Even little ones. Even at the pace of one per day.

The Stoics believed it was the little things that added up to wisdom and to virtue. What you read. Who you studied under. What you prioritized. How you treated someone. What your routine was like. The training you underwent. What rules you followed. What habits you cultivated. Day to day, practiced over a lifetime, this is what created greatness. This is what led to a good life.

“Well-being is realized by small steps,” Zeno would say looking back on his life, “but is truly no small thing.” Which is why today and every day, you need to think about those little things. They are worth sweating. You need to create good habits. You need to stick to your rules. You can’t make excuses to yourself, saying “Oh, this doesn’t matter.”

Because it adds up. Because it determines what you’ll accomplish, and what you won’t. Most important, it determines who you are.

No longer naive about the process, today I focus on improving a little bit every day, personally and professionally. I know that cumulatively this has enormous impact. It’s not as sexy as transformative reinvention or bold, risky bets, but it’s dependable and it works. It’s something I control.

No one can stop me from showing up. From getting better in the areas that most people don’t pay attention to. From what I do when nobody’s watching.

Epictetus called it fueling the habit bonfire. That’s what I try to do day in and day out.

Even this article is an example. How it turned out is a far cry from where it started—as an idea on a notecard, to an item on my to-do list which became a commitment I honored, which became a piece I spent time on across several days, which I returned to when I had tweaks and improvements, which was edited by a team, and then finally published.

Is it the best thing ever written? Absolutely not. But I am better for writing it, and it is better for the work I put into it, and the piece I write next will be better still.

The post All You Need Are a Few Small Wins Every Day appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

April 6, 2020

The Important Thing Is to Not Be Afraid

In scary times, it’s easy to be scared. Events can escalate at any moment. There is uncertainty. You could lose your job. Then your house and your car. Something could even happen with your kids.

Of course we’re going to feel something when things are shaky like that. How could we not?

Even the Stoics, who were supposedly masters of their emotions, admitted that we are going to have natural reactions to the things that are out of our control. You’re going to feel cold if someone dumps a bucket of water on you. Your heart is going to race if something jumps out from behind a corner. These are things the Stoics openly discussed.

They had a word for these immediate, pre-cognitive impressions of things: phantasiai. No amount of training or wisdom, Seneca said, can prevent us from having these reactions.

What mattered to them, and what is urgently needed today in a world of unlimited breaking news about pandemics or collapsing stock markets or military conflicts, was what you did after that reaction. What mattered is what came next.

There is a wonderful quote from Faulkner about this very idea.

“Be scared,” he wrote. “You can’t help that. But don’t be afraid.”

A scare is a temporary rush of a feeling. Being afraid is an ongoing process. Fear is a state of being.

The alertness that comes from being startled might even help you. It wakes you up. It puts your body in motion. It’s what saves prey from the tiger or the tiger from the hunter. But fear and worry and anxiety? Being afraid? That’s not fight or flight. That’s paralyzation. That only makes things worse.

Especially right now. Especially in a world that requires solutions to the many problems we face. They’re certainly not going to solve themselves. And inaction (or the wrong action) may make them worse, it might put you in even more danger. An inability to learn, adapt, to embrace change will too.

There is a Hebrew prayer which dates back to the early 1800s: כל העולם כולו גשר צר מאוד והעיקר לא לפחד כלל. “The world is a narrow bridge, and the important thing is not to be afraid.”

The wisdom of that expression has sustained the Jewish people through incredible adversity and terrible tragedies. It was even turned into a popular song that was broadcast to troops and citizens alike during the Yom Kippur War. It’s a reminder: Yes, things are dicey, and it’s easy to be scared if you look down instead of forward. Fear will not help.

What does help?

Training. Courage. Discipline. Commitment. Calm. But mainly, that courage thing—which the Stoics held up as the most essential virtue.

One of my favorite explanations of this idea comes from the Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield. “It’s not like astronauts are braver than other people,” he says. “We’re just, you know, meticulously prepared…” Think about someone like John Glenn, the first American to orbit the earth, whose heart rate never went above a 100 beats per minute the entire mission. That’s what preparation does for you.

Astronauts face all sorts of difficult, high stakes situations in space—where the margin for error is tiny. In fact, on Chris’ first spacewalk his left eye went blind. Then his other eye teared up and went blind too. In complete darkness, he had to find his way back if he wanted to survive. He would later say that the key in such situations is to remind oneself that “there are six things that I could do right now, all of which will help make things better. And it’s worth remembering, too, there’s no problem so bad that you can’t make it worse also.”

That’s the difference between scared and afraid. One prevents you from making things better, it may make them worse.

After the stock market crash in October 1929, America faced a horrendous economic crisis that lasted ten years. Banks failed. Investors were wiped out. Unemployment was some 20 percent. Herbert Hoover, who’d only been in office barely six months when the market collapsed, tried and failed repeatedly for the next 3.5 years to stem the tide. FDR, who succeeded him, would have never denied that things were dangerous and that this was scary. Of course it was. He was scared. How could he not be? Yet what he counseled the people in his now-legendary first inaugural address in 1933 was that fear was a choice, it was the real enemy to be fought. Because it would only make the situation worse. It would destroy the remaining banks. It would turn people against each other. It would prevent the implementation of cooperative solutions.

And today, whether the biggest problem you face is the coronavirus pandemic or the similarly dire economic implications—or maybe it’s both those things plus a faltering marriage or a cancer diagnosis or a lawsuit—you have to know what the real plague to avoid is.

This life we’re living—this world we inhabit—is a scary place. If you peer over the side of a narrow bridge, you can lose the heart to continue. You freeze up. You sit down. You don’t make good decisions. You don’t see or think clearly.

The important thing is that we are not afraid. That we don’t overthink things. That we don’t get distracted with the worst-case scenario on top of the worst-case scenario on top of the collision of two other worst-case scenarios. Because that doesn’t help us with what’s right in front of us right now. It doesn’t help us put one foot in front of the other, whether it’s on a spacewalk or a tough business call. It doesn’t help us slow our heart rate down whether we’re re-entering the earth’s atmosphere or watching a plummeting stock portfolio. It doesn’t help us remember that we’ve trained for this, that there is a playbook for how to proceed.

Remember, Marcus Aurelius himself faced a deadly, dangerous pandemic. His people were panicked. His doctors were baffled. His staff and his advisors were conflicted. His economy plunged. The plague spanned fifteen years of his reign with a mortality rate of between 2-3%. Marcus would have been scared—how could he not have been? But he didn’t let that rattle him. He didn’t freeze. He didn’t relinquish his ability to lead. He got to work.

“Don’t let your imagination be crushed by life as a whole,” he wrote to himself, as it was happening. “Don’t try to picture everything bad that could possibly happen. Stick with the situation at hand, and ask, ‘Why is this so unbearable? Why can’t I endure it?’ You’ll be embarrassed to answer.”

The crisis could have crippled him. But instead he stood up. He not only endured it, but he was a hero. He saved lives. He prevented panic from turning the battle into a route.

Which is what we must do today and always, whatever we’re facing.

We can’t give into fear. We have to repeat to ourselves over and over again: It’s OK to be scared, just don’t be afraid. We repeat: The world is a narrow bridge and I will not be afraid.

We have to focus on the six things, as Chris Hadfield might say, that we can do to make it better. And we can’t forget that there are plenty of things we can do to make things worse. Foremost among them, giving into fear and making mistakes.

Rather, we have to keep going. Like the thousands of generations who have come before us. Because time marches in only one direction—forward.

March 31, 2020

Will You Choose Alive Time Or Dead Time?

A few years ago, I was really stuck. I had accepted a one-year consulting contract that required me to commute from Austin to Los Angeles. It paid very well, but the gig was a disaster.

Everything was in chaos. No one could get anything done. We were at the complete mercy of a Wall Street hedge fund and a bunch of lawyers who were battling for control of the company.

I was frustrated. After I ran into a brick wall multiple times, it was like learned helplessness. What could I do? What was the point? I decided to just sit there and collect my checks while I waited for my contract to end.

Then I remembered a piece of advice I had gotten from the author Robert Greene many years earlier. He told me there are two types of time: alive time and dead time. One is when you sit around, when you wait until things happen to you. The other is when you are in control, when you make every second count, when you are learning and improving and growing.

Robert knows a lot about alive time and dead time. Although most people think of him as an incredibly productive and accomplished writer of amazing books, they don’t know about the 20 years he spent in obscurity, working something like 80 different jobs — most of which he hated—where he was at the mercy of horrible bosses.

As he said, “The worst thing in life you can have is a job that you hate, that you have no energy in, that you’re not creative with and you’re not thinking of the future. To me, might as well be dead.”

This does not mean you should quit your job immediately if you don’t love it. What Robert did during those years greatly influenced his writing. He wasn’t dead in those dead-end jobs; he was alive — researching, learning, studying, and observing the forces he would document in 48 Laws of Power, The Art of Seduction, Mastery, and The Laws of Human Nature.

So I decided I would make the absolute most of every moment while I was stuck in L.A.

I could not control what was going on with the board of directors, but I could choose how to spend my days. I decided to make the next several months a kind of work-study program. I was going to learn everything I could about people, about myself, about the factors that had created this crisis. I was also going to fill every nonworking second with productive reading and research.

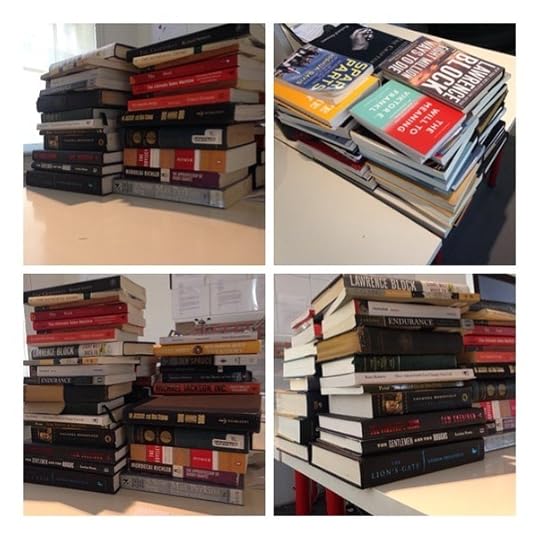

Here is my desk and the books I read in that time (compare that to a shot from earlier that summer):

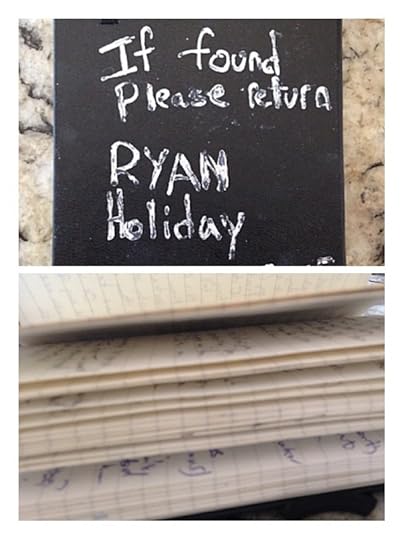

Here is the notebook I filled, writing a daily note to myself (I decided I would open the journal every day before checking email).

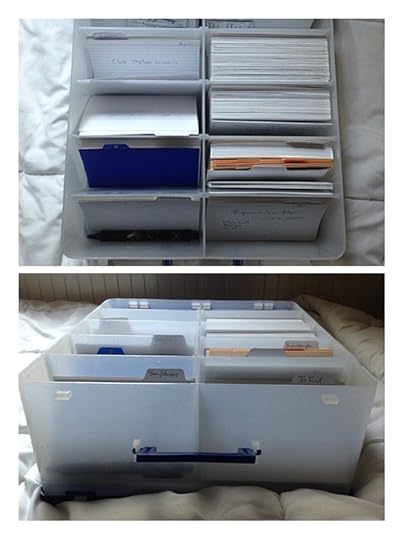

Here is the box of notecards I filled. I am most proud of the second box because these notes became my book, Ego is the Enemy.

As frustrated as I was with that consulting gig, it was actually the perfect place for me to research and meditate on that book I was thinking about writing. (You could say the obstacle was the way.)

Life is constantly asking us, Is this going to be alive time or dead time?

A long commute. Are we going to zone out or listen to an audiobook?

A delayed flight. Are we going to get in a couple of miles by walking around the terminal or shove a Cinnabon into our face?

A tour of duty or a contract we have to earn out. Is this tying us down or freeing us up?

That’s our call.

In Ego, I told the story of Malcolm Little. In 1946 he was arrested for trying to fence an expensive watch he’d stolen. In his apartment, police found jewelry, furs, an arsenal of guns, and all his burglary tools. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison. He could have served his time simply counting the days. He could have planned his next crime spree. Instead, he started reading. He literally copied the dictionary word for word. Every minute he wasn’t in his bunk, he was in the library. That was how Malcolm Little was transformed into Malcolm X.

Why did Malcolm X wear glasses? Because he literally wore his eyes out reading in prison.

But the trade-off was worth it. Those five years he served were some of the most productive of his life. He breathed in every second while his fellow prisoners rotted away.

So many people are busy thinking about the future that they miss the opportunities right in front of them. We think the future is something that happens, rather than something we make.

We think, This is just a job; this is just a crappy couple of [months, minutes, weeks]. It doesn’t matter. We tell ourselves that we’re just doing this to pay for school or because we have to. That no good can come out of it, except the direct deposit every two weeks.

I carry this medallion with me everywhere I go…

Like Robert says, if you’re going to think like that, you might as well be dead. Your mind apparently is.

We have to choose to make every moment a moment of alive time. We have to decide to be present. To make the most of whatever is in front of us.

Might it be better if we were totally free; if we weren’t stuck in traffic or at the airport or on some dumb assignment from our idiot boss? Sure. But we aren’t.

So what are we going to do about it? We are going to find some advantage.

Pick up a book. Pick up a pen. Pick up the phone.

Open your eyes. Open your ears. Open your mind.

There is plenty you can get out of this. Plenty you can do to make this productive, purposeful time—even if the situation is not completely in your control.

Resist the temptation to let silly politics or wanderlust distract you. Resist the resentment or the despondency. These things won’t help you. Only hunger and determination will.

In the 1960s, French political protesters used the slogan Vivre sans temps mort(live without wasted time). That’s what great leaders and artists have done, even in terrible conditions like a prison sentence, an exile, a bear market or a depression, military conscription, even being sent to a concentration camp (see Viktor Frankl). Through their attitude and approach, they transformed their circumstances into something that fueled greatness.

They asked themselves, alive time or dead time? They answered with their actions. Can you?

As they say, this moment is not your life. But it is a moment in your life. How will you use it?

March 17, 2020

How To Recover When The World Breaks You

There is a line attributed to Ernest Hemingway — that the first draft of everything is shit — which, of all the beautiful things Hemingway has written, applies most powerfully to the ending of A Farewell to Arms. There are no fewer than 47 alternate endings to the book. Each one is a window into how much he struggled to get it right. The pages, which now sit in the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, show Hemingway writing the same passages over and over. Sometimes the wording was nearly identical, sometimes whole sections were cut out. He would, at one moment of desperation, even send pages to his rival, F. Scott Fitzgerald, for notes.

One passage clearly challenged Hemingway more than the others. It comes at the end of the book when Catherine has died after delivering their stillborn son and Frederic is struggling to make sense of the tragedy that has just befallen him. “The world breaks everyone,” he wrote, “and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills.”

In different drafts, he would experiment with shorter and longer versions. In the handwritten draft he worked on with F. Scott Fitzgerald, for instance, Hemingway begins instead with “You learn a few things as you go along…” before beginning with his observation about how the world breaks us. In two typed manuscript pages, Hemingway moved the part about what you learn elsewhere and instead added something that would make the final book — “If people bring so much courage to this world the world has to kill them to break them, so of course it kills them.”

My point in showing this part of Hemingway’s process isn’t just to definitively disprove the myth — partly of Hemingway’s own making — that great writing is something that flows intuitively from the brain of a genius (no, great writing is a slow, painstaking process, even for geniuses). My point is to give some perspective on one of Hemingway’s most profound insights, one that he, considering his tragic suicide some 32 years later, struggled to fully integrate into his life.

The world is a cruel and harsh place. One that, for at least 4.5 billion years, is undefeated. From entire species of apex predators to Hercules to Hemingway himself, it has been home to incredibly strong and powerful creatures. And where are they now? Gone. Dust. As the Bible verse, which Hemingway opens another one of his books with (and which inspired its title) goes:

“One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth forever…The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to the place where he arose…”

The world is undefeated. So really then, for all of us, life is not a matter of “winning” but of surviving as best we can — of breaking and enduring rather than bending the world to our will the way we sometimes suspect we can when we are young and arrogant.

I write about Stoicism, a philosophy of self-discipline and strength. Stoicism promises to help you build an “inner citadel,” a fortress of power and resilience that prepares you for the difficulties of the world. But many people misread this, and assume that Stoicism is a philosophy designed to make you superhuman — to help you eliminate pesky emotions and attachments, and become invincible.

This is wrong. Yes, Stoicism is partly about making it so you don’t break as easily — so you are not so fragile that the slightest change in fortune wrecks you. At the same time, it’s not about filling you with so much courage and hubris that you think you are unbreakable. Only the proud and the stupid think that is even possible.

Instead, the Stoic seeks to develop the skills — the true strength — required to deal with a cruel world.

So much of what happens is out of our control: We lose people we love. We are financially ruined by someone we trusted. We put ourselves out there, put every bit of our effort into something, and are crushed when it fails. We are drafted to fight in wars, to bear huge taxes or familial burdens. We are passed over for the thing we wanted so badly. This can knock us down and hurt us. Yes.

Stoicism is there to help you recover when the world breaks you and, in the recovering, to make you stronger at a much, much deeper level. The Stoic heals themselves by focusing on what they can control: Their response. The repairing. The learning of the lessons. Preparing for the future.

This is not an idea exclusive to the West. There is a form of Japanese art called Kintsugi, which dates back to the 15th century. In it, masters repair broken plates and cups and bowls, but instead of simply fixing them back to their original state, they make them better. The broken pieces are not glued together, but instead fused with a special lacquer mixed with gold or silver. The legend is that the art form was created after a broken tea bowl was sent to China for repairs. But the returned bowl was ugly — the same bowl as before, but cracked. Kintsugi was invented as a way to turn the scars of a break into something beautiful.

You can see in this tea bowl, which dates to the Edo period and is now in the Freer Gallery, how the gold seams take an ordinary bowl and add to it what look like roots, or even blood vessels. This plate, also from the Edo period, was clearly a work of art in its original form. Now it has subtle gold filling on the edges where it was clearly chipped and broken by use. This dark tea bowl, now in the Smithsonian, is accented with what look like intensely real lightning bolts of gold. The bowl below it shows that more than just precious metals can improve a broken dish, as the artist clearly inserted shards of an entirely different bowl to replace the original’s missing pieces.

In Zen culture, impermanence is a constant theme. They would have agreed with Hemingway that the world tries to break the rigid and the strong. We are like cups — the second we are made we are simply waiting to be shattered — by accident, by malice, by stupidity or bad luck. The Zen solution to this perilous situation is to embrace it, to be okay with the shattering, perhaps even to seek it out. The idea of wabi-sabi is precisely that. Coming to terms with our imperfections and weaknesses and finding beauty in that.

So both East and West — Stoicism and Buddhism — arrive at similar insights. We’re fragile, they both realize. But out of this fragility, one of the philosophies realizes there is the opportunity for beauty. Hemingway’s prose rediscovers these insights and fuses them into something both tragic and breathtaking, empowering and humbling. The world will break us. It breaks everyone. It always has and always will.

Yet…

The author will struggle with the ending of their book and want to quit. The recognition we sought will not come. The insurance settlement we so desperately needed will be rejected. The presentation we practiced for will begin poorly and be beset by technical difficulties. The friend we cherished will betray us. The haunting scene in A Farewell to Arms can happen, a child stillborn and a wife lost in labor — and still tragically happens far too often, even in the developed world.

The question is, as always, what will we do with this? How will we respond?

Because that’s all there is. The response.

This is not to dismiss the immense difficulty of any of these ordeals. It is rather, to first, be prepared for them — humble and aware that they can happen. Next, it is the question: Will we resist breaking? Or will we accept the will of the universe and seek instead to become stronger where we were broken?

Death or Kintsugi? Fragile or, to use that wonderful phrase from Nassim Taleb, Antifragile?

Not unbreakable. Not resistant. Because those that cannot break, cannot learn, and cannot be made stronger for what happened.

Those that will not break are the ones who the world kills.

Not unbreakable. Instead, unruinable.

***

P.S. The Obstacle is the Way is on sale for $1.99 as an ebook in the US and Canada (and £3.32 in the UK). Get your copy today. We’re offering a 20% discount on our Obstacle is the Way coin and pendant at the Daily Stoic store as well (use code OBSTACLEDISCOUNT).

March 10, 2020

Here’s Some Stuff Worth Carrying With You Everywhere

WATCH: Ryan Holiday talks about his everyday carries

One of my favorite quotes is from Robert Louis Stevenson: To know what you like is the beginning of wisdom. He also says it’s the beginning of being old, but I ignore that part.

The point is I make a point to find out what I like and stick to it. While I am generally pretty minimalist—the Stoics were not big on extraneous possessions—I do have a handful of things that are of great utility (or meaning) to me and I carry them with me. And that’s the purpose of today’s piece: to show you what is in what you might call my “everyday carry.”

Some of these things are cheap. Some of them are not. Some of them are replaceable, others are not. To Seneca, the key was to be able to live—and act—as if all one’s possessions were equal, to live without worry of losing. I can’t say that I’m there yet, but I try to be.

I also try to know what is best so I don’t waste time and energy with flawed design or products that make my life worse.

Apple Watch — Our lives are tick… tick… ticking away. I like having the reminder on my wrist. At the same time, I don’t use it for any form of alerts or messaging. Honestly for me, it’s just an expensive pedometer/run tracker. It has actually helped me swim better because I don’t have to count laps. I post my swims/runs on Instagram and people ask what kind of watch it is all the time. Literally the most popular watch in the world!

Wedding ring — I have to be honest, I don’t wear my wedding ring everyday. Not because I don’t love my wife, but because I am afraid of losing it in the pool and also it gets too hot in Texas (and your hands swell). But I do carry my marriage with me everywhere. I cannot recommend getting married highly enough. I have a whole chapter on the importance of finding a partner in Stillness is the Key for a reason.

Signet ring — You’ll notice in most of my author photos that I am wearing a black agate signet ring. This was my grandfather’s ring, and he left it to me when he died. Wearing it makes me feel connected to him. When I’m not wearing it, I wear a Memento Mori signet ring (which has Marcus Aurelius’ famous quote on the inside: You could leave life right now… let that determine what you do and say and think). People have been wearing signet rings for thousands of years, I love the symbolism of it, and here’s a piece we put together on the history of them.

Power Wash Tee (or vintage tee) — Being able to wear and dress as I please is important to me—at least the freedom of it is. So I am in a T-shirt most days. I basically live in the American Apparel Power Wash Tee, which is the standard American Apparel T-shirt but treated so it mimics a shirt that has been washed roughly 50 times. Unfortunately, the company is basically a ghost ship these days, so the shirts are harder to find than they used to be. If I’m not wearing one, I usually wear vintage concert t-shirts, either that I bought myself or I found on Etsy (if you care about the environment, wearing vintage clothes is actually a basic thing you can do to reduce your footprint).

Memento Mori challenge coin — In my left pocket, I carry a coin that says Memento Mori, which is Latin for ”remember you will die.” On the back, it has one of my favorite quotes from Marcus Aurelius: “You could leave life right now.” I firmly believe the thought of our mortality should shadow everything that we do, not in a way that is depressing, but liberating. It should let you cut out bullshit, it should let you decide how you’re going to treat other people and let yourself be treated, and it should determine the quality of the work that you’re going to do.

Amor Fati coin — In my right pocket, I carry another coin that says Amor Fati on the front, and the line Friedrich Nietzsche called his formula for greatness on the back: “Not merely bear what is necessary… but love it.” The reason? To constantly remind myself that nothing bad can really happen—there is only fuel. That everything I face can be of some purpose. The line from Marcus Aurelius was that a blazing fire makes flame and brightness out of everything that is thrown into it. The artist that turns pain and frustration and even humiliation into beauty. The entrepreneur that turns a sticking point into a money maker. The person who takes their own experiences and turns them into wisdom that can be learned from and passed on to others. The Stoics talk about it over and over: we don’t get to choose so much of what happens to us in life, but we can always choose how we feel about it, whether we’re going to work with it or not. Why on earth would you choose to feel anything but good? Why would you choose not to work with it? What would that accomplish? Those are the questions I have to remind myself of.

A book — You should always have a book with you. Always. People often assume something about me: that I’m a speed reader. It’s the most common email I get. They see all the books I recommend every month in my reading newsletter and assume I must have some secret. They want to know my trick for reading so fast. The truth is, even though I read hundreds of books each year, I actually read quite slow. In fact, I read deliberately slow (more on this below). But what I also do is read all the time. I am always carrying a book with me. Every time I get a second, I crack it open. I don’t install games on my phone—that’s time for reading. When I’m eating, on a plane, in a waiting room, or sitting in traffic in an Uber—I read. There’s no trick, no secret, no shortcut. I like B.H. Liddell Hart’s old line that sometimes the longest way around is the shortest way home. If you put the time in, you get the results. If you are serious about wanting to commit to being a better reader, I think you’ll like the reading challenge I put together.

Journals — I only have to carry these with me when I travel (the rest of the time they stay at home) but when I do, I lug them everywhere. In the first one—a small blue gold-leafed notebook—I write one sentence about the day that just passed. Then in a black Moleskine, I quickly journal yesterday’s workout (how far I ran or swam), what work I did, any notable occurrences, and some lines about what I am grateful for, what I want to get better at, and where I am succeeding. Last is The Daily Stoic Journal where I prepare for the day ahead by meditating on a short prompt; the key is setting an intention or a goal for the day that I can review at the end of the day. I got asked a lot on podcasts and at events and appearances for Stillness Is The Key about the best way to develop stillness in your life. Journaling is usually at the top of that list, and so I put together this comprehensive guide to journaling.

Pen (stolen from the last hotel I stayed in) — I always carry a pen with me to mark up the book I am carrying. As I said above, I’m a slow reader. I take notes, I ask questions, I mark anything that sticks out at me as I read—passages, words, anecdotes, stories, info. It’s what the best readers do, period. It’s called “marginalia.” Then I fold the bottom corners of the pages of the particular passages I want to come back to and when I finish a book, I go back through and transcribe them onto notecards for my commonplace book.

AirPods — I balked at the price too, but turns out they were worth every penny. Not just because I never get frustrated with tangled wires, but because it helps me leave my phone in my pocket. The more that it’s in my pocket, the more alive, present, and in control I am. Cal Newport calls it “digital minimalism”—the idea that we need to be in control of these technologies rather than be controlled by them. Because as my watch and Memento Mori coin are reminding me, this is my life and it’s ticking away every second. I want to be there for it, not staring at a screen.

iPhone — The phone is probably the antithesis of philosophy but unfortunately a part of modern life (and work). I use it only for music, podcasts, calls, and emails. No alerts. No social media. No news. No watching TV or movies. It stays in the pocket most of the time (thanks to the AirPods). For tips on using your phone less, try this piece I did a few months ago.

***

There’s a beautiful story about a Buddhist teacher named Ajahn Chah. He lifts a crystal goblet from his side table and holds it up to the sun. “Do you see this glass?” he says to his students. “I love this glass. It holds the water admirably. When the sun shines on it, it reflects the light beautifully. When I tap it, it has a lovely ring. Yet for me, this glass is already broken. When the wind knocks it over or my elbow knocks it off the shelf and it falls to the ground and shatters, I say, ‘Of course.’ When you understand that this glass is already broken,” Chah says, “every minute with it is precious.”

That’s what I try to remind myself with all of these things, especially the ones that really mean something to me: that the cup is already broken. The ring is already lost. The screen on the phone is already cracked. My dog-eared copy of Meditations just fell apart. Ownership—much like existence—is transitory. So while I prize these possessions, they are also a great reminder of how ephemeral all of this is. The Stoics talk a lot about detachment, loosening the hold that possessions have on us, embracing the truth of uncertainty, having the ability to enjoy whatever is in front of you, whether that’s a brand new Tesla or a beat-up Taurus. “He is a great man who uses earthenware dishes as if they were silver,” Seneca wrote, “but he is equally great who uses silver as if it were earthenware.”

That’s the idea. You don’t have to abstain from having nice things. If you can afford it, or if it was given to you, what’s the point? What you do have to reject is the idea that they say anything about you as a person. You have to reject the idea that these things are somehow special because they are valuable or because other people desire them. The Stoics would urge us to remember that things don’t make the man.

March 3, 2020

This Question Will Change Your (Reading) Life

When I was a teenager, I began a habit that would change the course of my entire life. I don’t mean to overstate it — it was simple, just a question I would ask the people I met — but without it, I’m not sure who I would have turned out to be.

Every time I would meet a successful or important person I admired, I would ask them: What’s a book that changed your life?* And then I would read that book. (In college, for instance, I was lucky enough to meet Dr. Drew, who was the one who turned me on to Stoicism.)

Who I asked the question to first, or how I came to the habit, I can’t recall, but the results stayed with me. I can reel off the titles of the books that came out of it like they are tattooed on my body:

48 Laws of Power

Meditations

Autobiography of Malcolm X

History of the Peloponnesian War

What Makes Sammy Run?

Man’s Search for Meaning

The question that produced these books as answers was not borne of idle curiosity. It was my way of cutting through a personal conundrum, which was this:

I loved books and was very hungry for the good stuff — what Tyler Cowen has called “quake books.” The ones that shake you. That knock everything over and turn it upside down. But I also understood that there are so many books out there, and only so much time. It was overwhelming.

Which books should I read? Should I read books about physics or books about history or books about self-improvement? And even if I knew the genre I preferred, which authors should I read and why? Should I read new books or old books? The books getting rave reviews or the classics or the ones on the featured table in the front of the store?

I didn’t know. So this question was my hack.

If a book changed someone’s life — whatever the topic or style — it was probably worth the investment. If it changed them, I thought, it might at least help me.

What resulted was a kind of ad-hoc reading list of transformational books and surprise rabbit holes that I would have never expected. Because the books that change people cut across the entire spectrum of intellectual pursuits: philosophy, psychology, literature, poetry, and self-help. The discrete topics of those books, individually, are as varied as the individuals who answered this question.

You could fill up an entire life of reading with just these books and that would be enough.

Eventually, I applied this little trick beyond just people that I met. Whenever I read interviews of interesting people and they mentioned a book that was particularly influential or important to their development, I would buy it.

I didn’t need to be told in person. I didn’t even need to be the one asking the question. (The New York Times By The Book column is a good place to start)

I read an interview where Neil Strauss mentioned John Fante’s Ask the Dust, so I bought it, read it, and fell in love with it…and in reading about John Fante, I learned that he’d been influenced by Nietzsche and Knut Hamsun, so I read both of them. Napoleon and Alexander Hamilton were changed by Plutarch’s Lives (and so were about a million other people across history), so of course, I read it. I heard that Phil Jackson recommended his players read Corelli’s Mandolin, and that Pete Carroll recommends The Inner Game of Tennis. Lots of successful people have reading lists that they either post on their blogs or that have been compiled by biographers after their deaths. I made my way through those too, book by book.

This strategy has lead me to some busts, of course, Elon Musk supposedly loves Twelve Against The Gods, but I didn’t quite get what the fuss was about (the used copy I bought cost $139). I saw entrepreneurs I admired who swore by Ayn Rand and read Atlas Shrugged, and even in my early twenties, I thought it was a bit ridiculous. Tim Ferriss loves Zorba the Greek, but it didn’t do it for me. But even in these books, I got something out of them. I got more out of them than I would have gotten from most of the forgettable titles the New York Times was slating for review or whatever was tearing up the bestseller lists at that moment.

Socrates supposedly said that we should employ our time improving ourselves by other men’s writings, and that in doing so we can “come by easily what others have labored hard for.” Yes. That’s the point of literature — it is the accumulation of the painful lessons humans have learned by trial and error. For 5,000 years we’ve been recording this knowledge in books. The more hard knocks we can avoid by reading them, the better. (This quote, attributed to Mark Twain, says it well: “The man who does not read good books has no advantage over the man who can’t read them.”)

Not only have we been creating books for thousands of years, but humans — particularly the smart and successful ones — have been reading them for just as long. We’ve been reading on cuneiform tablets, on scrolls, on books created out of stretched animal skins, and now on mass-produced paperbacks and via Audible. Over those centuries, there has been an incredible filtering mechanism working for us, finding and highlighting the books that contain the most wisdom.

That’s why I started asking people for the books that changed their lives. We should seek out the literature that has shaped the people we admire and respect — we can cut down even on the discovery costs of looking for those books. They’ve given us a shortcut to the treasure map.

Everybody seems to want a mentor. Meanwhile, they’re passing up the opportunity to learn directly from the people who taught the people you aspire to be like. When someone like John McCain spends his whole life raving about For Whom The Bell Tolls, why would you not check it out? Clearly, it got him through some shit. Peter Thiel credits Rene Girard and Things Hidden Since The Foundation Of The World with shaping his worldview. Clearly, it’s made him some money—you’re not going to pick that up? Angela Merkel—Forbes’ number 1 most powerful women twelve of the last thirteen years—lists Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina and Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov as her favorite reads. Add them to the list!

The people you admire or want to be like in your own space, something made them the way they are. They didn’t come out of the womb that way. It wasn’t only experiences that contributed to what they know and how they think. Right now I am reading How The Classics Made Shakespeare…which is literally a book about all the books that taught the greatest playwright who ever lived.

Why not try to find these books? You’re just going to figure it all out on your own? You’re going to just pass on this opportunity for connection? (I’ll tell you, there is nothing people like hearing more than thoughtful questions about their favorite book or author.)

C’mon.

Send an email. Raise your hand and ask a question. Stop by office hours. Dig through old interviews.

Then…

Go to the library. Pull up Amazon and buy the cheapest used copy you can find. “Borrow it” from a friend.

Whatever it takes.

And after these books change you, as wells as other books you discover on your own, you have one important job: You have to pay it forward.

Because that’s what we’re trying to do here — we’re trying to help others learn from the wisdom of other’s experiences. We’re trying to filter the good stuff to the top — to upvote it — to make it even more readily available than it was in our own lives.

That’s why I keep my own list now, of books to base your life on. It’s why I run my reading list newsletter each month. And it’s why I’ll almost always stop, no matter how tired I am or how many emails I have in my inbox, to respond when people ask: What books changed your life? What do you think I should read?

Because it’s the most important question in the world.

***

* There are other versions of the question you can ask:

“What book do you wish you read earlier in life?”

“What book shaped your career as a _______ more than any other?”

“Is there a book out there that really changed your mind?”

“I’m dealing with ___________ right now; what authors would you recommend on that topic?”

______

Want To Take Your Reading To The Next Level?

We’ve created a challenge at Daily Stoic that’s perfect for you: Read to Lead: A Daily Stoic Reading Challenge

Reading is the shortest, most established path to total self-improvement. We know intuitively that this is true. The question is: what active steps are we taking toward our better selves, to improve every aspect of our lives, to ensure success? We created the Read To Lead challenge as a way to give you an answer to that question.

February 27, 2020

There’s No Such Thing as ‘Quality’ Time

When you’re too busy aiming for it, you miss the moments in front of you

It’s one of those lines we throw out casually: “I want to spend more ‘quality time’… ” whether it’s with friends, with family, with your kids, or with yourself.

While the phrase certainly comes from a good place, there’s a disconnect: The perfectionist side of our brain, fueled by movies and Instagram, wants everything to be special, to be “right.” But that’s an ideal that the busy, ordinary, doing-the-best-we-can versions of ourselves can’t always live up to.

The result? An inevitable sense of disappointment. We feel awful for the deficiency, so out of guilt, we plan elaborate vacations. We project enormous expectations and pressure on ourselves. We think “Oh, if only I had more money, or a better job, or lived in France where the child care benefits were different, then I could be happy.”

That’s not fair. And it’s also damaging.

The reason is that there is no such thing as “quality time.” Jerry Seinfeld, who has three teenage kids, put it well:

I’m a believer in the ordinary and the mundane. These guys that talk about ‘quality time’ — I always find that a little sad when they say, ‘We have quality time.’ I don’t want quality time. I want the garbage time. That’s what I like. You just see them in their room reading a comic book and you get to kind of watch that for a minute, or [having] a bowl of Cheerios at 11 o’clock at night when they’re not even supposed to be up. The garbage, that’s what I love.

To be fair, Seinfeld is the master of the mundane. Banality has made him a near-billionaire. But there is a deeper truth to what he’s getting at. Special days? Nah. Every day is special. Every minute can be “quality time.”

I remember when my book The Obstacle Is the Way first starting making its way through professional sports, I was invited to see the Seahawks training camp up in Renton, Washington. I had just gotten married and my career was really firing, so I asked Seahawks head coach Pete Carroll how coaches manage to make a personal life work with such insane hours. Pete, who has been married for more than 40 years, looked at me and said, “You have to find the moments between moments.”

It’s something I’ve seen inside the buildings of most of the sports teams I’ve visited. Yeah, the coaches and staff often get there before the sun comes up and leave long after it’s gone down. Yeah, they travel a lot. But their families are always around. They’re doing lunches and dinners at the office. They are taking time between sessions to sit and talk, to hang out, to work out, to do things together.

It’s all about the moments between the moments for ordinary people, too. I’ve never understood parents who complain about “being a chauffeur” to their kids. “What am I, your driver?” they say. Sure, it can be a pain in the ass to drive your kids around. To day care. To school. To a friend’s house. To a doctor’s appointment. To soccer practice. Sometimes it can feel like this is all parenting is — driving a little person around. For free.

But instead of seeing the drive as an obligation or an inconvenience, why not choose to see it as a gift? A moment between moments. In fact, it’s a lot of moments. Even better, it’s captive time. You are stuck together! This is wonderful. This is what you wanted, right? An opportunity to connect? To bond? To have fun? So use it!

As many parents with older children will tell you, something changes when kids are in the car with you. Suddenly, you’re not the parent. You’re just a companion, a fellow human being equalized by traffic. Kids will share things in the car they wouldn’t say anywhere else. Better yet, when their friends are in the car too, you fade into the background and suddenly you can watch how your kid is with other people. It’s like you’re a detective watching through one-way glass. You’ll learn things about your own son or daughter that you’d never know otherwise. You’ll get a glimpse into who they are in a way they could never articulate to you directly.

This isn’t only true for kids. Some of my best memories with my wife, or friends, have happened in the car. Or when we were sitting at the gate, waiting for a delayed plane. Sometimes these awkward, in-between moments allow for conversations that never would have happened otherwise. Even some of my best writing and thinking have come when I was stuck somewhere I didn’t want to be, or doing something I didn’t want to do. When you’re out of excuses for being busy, when you can’t defer or plan for some idealized future, you’re forced to just make do with what’s in front of you. The distinction between “quality” time and “garbage” time falls away and you’re left with what simply is.

Often when we are trying really hard to attain something, we end up missing the fact that we’ve had it in our hands the whole time. Sure, letting your kids blow off school for a fun day together can be wonderfully special — but so can the 20-minute drive in traffic to school. So can mailing a letter or watching a garbage truck meander through the neighborhood.

All time with your kids — all time with anyone you love — is created equal. What you do with it is what makes it special. Not where. Or for how long. Or at what cost.

Think back to your own childhood. Rushing around to get somewhere on time. Packing for that trip to Disneyland. Getting all dressed for those ridiculous matching group photos. “Why are we doing this?” you asked when you were old enough to notice that it seemed really stressful and not fun. The answer was always something like: “Because we’re a family.” As if you couldn’t be a family anywhere, doing anything. As if you couldn’t do it right here and now.

This is worth remembering in all facets of life: You can be a family without getting dressed and leaving the house. You can be in love in the McDonald’s drive-through. You can be romantic near the eggs at the grocery store. You can be a writer as you ride the elevator down to take out the trash. You can be a good person in how you answer the phone or how you send emails.

There’s a Tolstoy quote I love: “There is no past and no future; no one has ever entered those two imaginary kingdoms. There is only the present.”

When you realize there is no such thing as “quality time,” when you become okay with “garbage time,” you end up getting the best kind of time there is. You get the moment right in front of you.

If you’re looking for parenting advice, I highly recommend you check out Daily Dad. I write a daily email about how to become a better parent, every day. One piece of timeliness advice, delivered to your inbox each morning. It’s free! Check it out here.

February 25, 2020

How Does It Feel To Get Everything You Ever Wanted?

There are two tragedies in life, Oscar Wilde once said: not getting what you want and getting everything you want. The last, he lamented, is much worse.

I wanted to be a writer. I don’t know when that dream started, but for a very long time, I craved accomplishment in this creative calling that very few are lucky enough to make a living in, let alone find success in.

Of course, like most people, I also fantasized about what it would be like to have money, or more specifically, to have lots of it. It’d be cool to be a little famous too, while I was at it. To be connected with or have influence over important people, to be sought after for advice or input. That has to be awesome too, right?

Maybe, apart from the genuine love of writing, that’s what attracted me to being an author. It was a way to have all those things. And indeed, in the last year or so, it has become harder to deny that I have accomplished most of them.

My books have sold extremely well. They have been reviewed in major newspapers and are translated in dozens of languages. Looking at my bank account here, as I write this, I am relieved to say that I don’t really need to think about money anymore. Few authors make that life-changing, generational kind of wealth, but I’ve done well enough to have my and my family’s needs met without worry, probably for good. If that weren’t lucky enough, I regularly get invited to speak with all sorts of interesting people from the worlds of politics, finance, sports, and entrepreneurship, to name a few.

So how does that feel? How does it feel to have everything you ever wanted in life? To have it earlier than you ever could have realistically expected?

I can tell you: It feels like nothing.

Hitting #1 on the bestseller list?

Looking at a comfortable bank balance?

Sitting across the table from some powerful person as they hang on your every word?

Nothing.

In the new Taylor Swift documentary she talks about that moment where 1989 came out and utterly dominated the music industry. “Oh god that was all you wanted,” was the only thought in her head as she won Album of the Year for the second time. “That was all you wanted. That was all you focused on…. You get to the mountaintop and you look around and you’re like, ‘Oh God, what now?’

Ten years ago, I probably would have scoffed at that, whether I was hearing it from a mega-famous mega-millionaire or a grandparent. I know that was my reaction a long time ago to a beautiful passage from F. Scott Fitzgerald:

“From that period I remember riding in a taxi one afternoon between very tall buildings under a mauve and rosy sky; I began to bawl because I had everything I wanted and knew I would never be so happy again.”

But today, I get it. I understand that existential angst. You work so long and hard to accomplish what feel like crazy pie-in-the-sky dreams, then when the opportunity knocks, you answer, and success comes flooding in, you expect the high to last. You expect it will feel wonderful and exciting, but it doesn’t. In fact, it doesn’t really feel like anything at all.

Maybe it feels even worse than nothing because you expected something so different.

I was mowing the lawn when I found out my book hit #1 this year. I saw the email come in and went right back to mowing the lawn. Nothing was different. Nothing changed. I was still me. And when I hit it two more times over the next twelve months? The same…only less because the novelty had worn off. The news wasn’t new anymore.

I wish I could tell you that this feeling is the exception, but it’s probably closer to the rule.

It’s what Olympic medalists feel, it’s what politicians feel the day they are sworn in, it’s what actors feel when they win an Oscar, it’s what scientists feel when they are awarded the Nobel Prize.

We all think some external accomplishment is going to change everything, but it never seems to. It doesn’t change how you see yourself, it doesn’t change how you go through the world, it doesn’t change what you feel like when you wake up in the morning.

Yet even as I write those words, I know most people won’t hear me. We’re hard-wired not to—and to delete them instead. It makes complete sense from an evolutionary point of view why we would believe that achievement will make life better, why it will be worth all the sacrifice and pain, how it will transform and change everything bad in our lives into something good. It’s that drive that has sent many an explorer off on another dangerous voyage into the unknown, kept an inventor in their workshop despite all the wealth and admiration in the world, it’s what made someone want to be not just a king but the king of kings. But just because something is good for progress, doesn’t mean it’s good for a person. You have to learn the lie of our biology by experience.

To be clear, I am not writing this to the person who is still early in their career, who has yet to put that first big win on the board. That person is not ready to hear what I am saying. I am instead writing to the person who has already done it, who is asking, as Taylor Swift and countless other people have before and since asked: What now? What do I do now?

First: Do not deceive yourself. The ‘nothing’ you feel is not because what you did is nothing, or not enough. A second ring is not the answer. It does not prove the existence of the first ring, nor increase its luster. Proving to yourself and critics that this was not an accident is not possible. Advancing higher in the ranks, moving the goalposts a little further back, telling yourself that it will be different next time—this is the definition of insanity (expecting new results from the same inputs).

Second: Do not despair. The problem for most people is that they have put so much pressure on this moment—not when the work is complete, but rather when the achievement is recognized—that when it comes it wrecks them. They turn to drugs. They act out and self-sabotage. Or they quit and walk away. The grief over this lost hope can destroy you. Because you’re not sure what to live for now, you’re even less sure how to keep going.

What you must do instead is realize that what you have been doing is not the problem, it’s the why. You thought that doing important or impressive work will make you happy. This was precisely wrong. It’s that being happy will help us do important and impressive work, quite possibly better and more pure work.

There is a story I wrote about in Stillness is the Key in which Kurt Vonnegut and Joseph Heller, the authors of Slaughterhouse Five and Catch-22, respectively, were once at a fancy party in New York. As they stood in the home of some billionaire, Vonnegut needled his friend.

“Joe,” he said, “how does it feel that our host only yesterday may have made more money than your novel has earned in its entire history?”

“I’ve got something he can never have,” Heller replied.

“And what on earth could that be?” Vonnegut asked.

“The knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

This is actually the best place to work from, to live from.

Over the last year, I have tried to see if I can’t operate from a place of fullness rather than craving, realizing that I already have everything I want and, in fact, have since the moment I was born. That doesn’t mean I’ve stopped working—Joseph Heller didn’t—but it means that I now see the results as extra, not as entitlements or rewards or just dues.

“We are here as if immersed in water head and shoulders underneath the great oceans,” the great Zen master Gensha once said, “and yet how piteously we are extended our hands for water.”

To be alive, that is the accomplishment. To have your health. To have people you love. This is winning. To get to do the work—that’s the reward, not whether the work is recognized. Which is all we control anyway.

Theodore Roosevelt was a published author by age 23. He had wealth, fame, medals and power. But eventually he realized that “far and away the best prize that life has to offer is the chance to work hard at work worth doing.”

I’ve come to realize along those lines that there is a difference between being a writer and an author. What I love, what I should chase is the writing, being an author is about results. That’s why I always found rewards underwhelming. I was focusing on the wrong prize, missing that I had it along.

The irony is that winning great prizes not only feels like nothing, but understood properly should change absolutely nothing! We should accept the honors with gratitude, we should cash the checks (saving the money responsibly), we should enjoy the parties or the praise, and then we should, as soon as possible, get back down to work.

Do the verb, rather than be the noun.

Not to prove anything to anyone. Not to scale a higher mountain because it will feel different. Not to really get our parents to notice this time. Not because flying private is even better than flying first class is better than economy.

No.

We get back to work because the dream is the doing. The lucky break is the opportunity. It’s the process that we have always loved, it’s the joy of realizing our potential that should never get old or let us down.

It is the only fruit that doesn’t underwhelm or spoil.

***

P.S. My latest book Stillness is the Key was an instant #1 New York Times and Wall Street Journal Bestseller. Whether you’ve achieved everything you dreamed of and don’t know what to do now, or you’re feeling overwhelmed, or you need a simple but inspiring antidote to the stress of 24/7 news and social media, Stillness is the Key is for you. I think it’s the best writing I’ve ever done, and I also think it’s the most important topic I have ever written about.

February 20, 2020

Take A Walk: The Work & Life Benefits of Walking

If you’ve ever doubted whether human beings are designed for walking, all you have to do is strap a fussy baby into a BabyBjörn and take them out for a stroll. The crying stops. With each step, the resistance and the kicking and the screaming fades away. It’s almost as if they enter a trance.

Hours can pass and, if you’re moving, whether they’re an infant strapped to your chest or a toddler in a stroller, even an ordinarily troublesome child turns into a dream.

We evolved this way. To travel by foot, to explore, to cover distances both short and long, slowly and steadily. Which is why my point here really has nothing to do with childcare.

Taking a walk works on a racing or miserable mind just as well as a colicky baby. We are an ambulatory species and often the best way to find stillness—in our hearts and in our heads—is to get up and out on our feet. To get moving. To take a damn walk.

For decades, the citizens of Copenhagen witnessed the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard embody this very idea. The cantankerous philosopher would write in the morning at a standing desk, and then around noon would head out onto the busy streets of Denmark’s capital city.

He walked on the newfangled “sidewalks” that had been built for fashionable citizens to stroll along. He walked through the city’s parks and through the pathways of Assistens Cemetery, where he would later be buried. On occasion, he walked out past the city’s walls and into the countryside. Kierkegaard never seemed to walk straight either—he zigged and zagged, crossing the street without notice, trying to always remain in the shade. When he had either worn himself out, worked through what he was struggling with, or been struck with a good idea, he would turn around and make for home, where he would write for the rest of the day.

In a beautiful letter to his sister-in-law, who was often bedridden, and depressed as a result, Kierkegaard wrote to her of the importance of walking. “Above all,” he told her in 1847, “do not lose your desire to walk: Every day I walk myself into a state of well-being,” he wrote, “and walk away from every illness; I have walked myself into my best thoughts, and I know of no thought so burdensome that one cannot walk away from it.”

Life is a path, he liked to say, we have to walk it. He was by no means alone in believing that.

Nietzsche said that the ideas in Thus Spoke Zarathustra came to him on a long walk. Nikola Tesla discovered the rotating magnetic field, one of the most important scientific discoveries in modern history, on a walk through a city park in Budapest in 1882. When he lived in Paris, Ernest Hemingway would take long walks along the quais whenever he was stuck in his writing and needed to clarify his thinking. Charles Darwin’s daily schedule included several walks, as did those of Steve Jobs and the groundbreaking psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, the latter of whom wrote that “I did the best thinking of my life on leisurely walks with Amos.” It was the physical activity in the body, Kahneman said, that got his brain going.

Freud was known for his speedy walks around Vienna’s Ringstrasse after his evening meal. The composer Gustav Mahler spent as much as four hours a day walking, using this time to work through and jot down ideas. Ludwig van Beethoven carried sheet music and a writing utensil with him on his walks for the same reason. Dorothy Day was a lifelong walker, and it was on her strolls along the beach in Staten Island in the 1920s that she first began to feel a strong sense of God in her life and the first flickerings of the awakening that would put her on a path toward sainthood. It’s probably not a coincidence that Jesus himself was a walker—a traveler—who knew the pleasures and the divineness of putting one foot in front of the other. Indeed, it’s no coincidence that many of the greatest expressions of faith and devotion involve long walks (i.e. pilgrimages) to holy sites around the globe.

Why does walking work? Why has it worked for so many different kinds of people in some many different kinds of careers?

Walking is a deliberate, repetitive, ritualized motion. It is an exercise in peace.

The Buddhists talk of “walking meditation,” or kinhin, where the movement after a long session of sitting, particularly movement through a beautiful setting, can unlock a different kind of stillness than traditional meditation.

Personally, I’ve found that being aware on my walks—being present and open to the experience—has brought me closest to what I assume the Buddhists are talking about. I put the pressing problems of my life away, or rather I let them melt away as I move. I look down at my feet. What are they doing? I notice how effortlessly they move. Is that really me who’s doing that? Or do they just sort of move on their own? I listen to the sound of the leaves crunching underfoot. I feel the ground pushing back against me.

These are things anyone can do on a walk. Things you can do. Breathe in. Breathe out. Consider who might have walked this very trail in the centuries before you. Consider the person who paved the asphalt you are standing on. What was going on with them? Where are they now? What did they believe? What problems did they have?

But I don’t have time you say. Sure you do. Get up earlier. Take your phone calls outside, as I try to do. Do walking meetings instead of sitting ones. Do a couple laps around the parking lot before you go inside. Don’t call an Uber, walk there instead.

We aren’t that different from a baby. Stuff gets us stressed. We have feelings that we can’t quite find the words to explain and process. The world is overwhelming. Our needs aren’t being met. If we are allowed to simply stew in this, of course, we’ll cry and yell and get angry.

The adult must come in and break us out of this. The adult must take us outside and get us moving. Stimulate our senses. Calm our emotions and thoughts down by the rhythm of the walk, by reassuring firmness of the ground underfoot.

The poet William Wordsworth walked as many as 180,000 miles in his lifetime—an average of six and a half miles a day since he was five years old! It wasn’t for the physical fitness benefits that he put in these miles, though it certainly didn’t hurt. He did much of his writing while walking, as lines of poetry came to him, Wordsworth would repeat them over and over again, since it might be hours until he had the chance to write them down. Biographers have wondered ever since: Was it the scenery that inspired the images of his poems or was it the movement that jogged the thoughts?

Every ordinary person who has ever had a breakthrough on a walk knows that the two forces are equally and magically responsible.

Which is why whoever you are and whatever you do, you should do yourself a favor today and take a walk!

–