Ryan Holiday's Blog

November 12, 2025

The Simplest Way To Feel Better In Terrible Times

I’m giving a talk in Seattle on 12/3 as part of the Daily Stoic Live tour—

grab seats and come see me

! I’ll also be in San Diego on February 5 and Phoenix on February 27. More dates will be announced soon—

sign up here

and we’ll let you know when I’m coming to your area.

I’m giving a talk in Seattle on 12/3 as part of the Daily Stoic Live tour—

grab seats and come see me

! I’ll also be in San Diego on February 5 and Phoenix on February 27. More dates will be announced soon—

sign up here

and we’ll let you know when I’m coming to your area.

It’s easy to feel disoriented and disillusioned right now.

There’s so much happening in the world, and so much of it feels terrible. There is dysfunction. There is conflict. There is outright lawlessness. There is corruption. There is cruelty.

But there’s a really simple way to feel better.

I don’t mean turning off the news—though you should definitely do that, as we’ve talked about. I don’t mean taking care of yourself—though that matters too and you should. Go for a run. Meditate. Eat better. Go to therapy. This is all great.

I’m talking about something simpler. Something that works immediately. Something that every wisdom tradition has taught but we keep forgetting:

Do something nice for someone else.

It may seem like a small thing. In fact, it’s everything.

There’s an old story about a boy who comes upon a beach covered in starfish—hundreds, thousands of them washed up on the shore. It’s an appalling, tragic sight. On the verge of tears, he begins throwing them back into the sea, one by one.

“It doesn’t matter,” an adult tells him. “You’ll never even make a dent in this.”

“It matters to this starfish,” the boy says, as he rescues another one.

He’s right. To the person you’re helping, to the person whose burden you are lessening, there is nothing “small” about it. When the Talmud says that he who saves one person saves the world, maybe that’s partly what they meant—you certainly save that person’s whole world.

We get this backwards so often. Despite the expression “all politics is local,” we tend to think big picture before we think little picture. We obsess over grand gestures, complete solutions, systemic change. Meanwhile, there’s suffering right in front of us. A neighbor who needs help. A food bank down the street. A person we could make smile today.

Marcus Aurelius in Meditations talks about a period of his life where he felt like good fortune had abandoned him. And indeed, it certainly looked like it had. There was the Antonine plague, which would kill literally millions of people during his reign. There were wars, floods, and famines. He would bury several of his children. He was betrayed by his most trusted general in what amounted to an attempted coup. He did not meet with “the good fortune he deserved,” one ancient historian noted, “as his whole reign was a series of troubles.”

But instead of throwing himself a pity party, instead of despairing, he rewrote his definition of “good fortune.” It was not getting everything you wanted, he said. No, “true good fortune is what you make for yourself. Good fortune: good character, good intentions, and good actions.

About five years ago, increasingly disgusted by the commercialism of Thanksgiving and Christmas—at least here in the US—I was thinking about just not participating. I hated that every year businesses were expected to offer bigger and bigger sales for Black Friday and Cyber Monday. I hated the clips on the news about people fighting over a deal on a flat screen television. But I decided instead of just writing about it, I would try to do something about it with my own small business.

So on Black Friday and Cyber Monday, we ran a fundraiser for Feeding America, a nonprofit that works to provide meals to families experiencing hunger, instead. I put in the first $10,000 and we raised another $100,000. The next year we did it again and every year since. Cumulatively, we’ve raised something like $1M or 10,000,000 meals for people in need.

Did that save the world? Of course not, but it definitely made someone’s world a little better. And you know what else? It made me and my world better too.

That’s what generosity does, by the way. Yes, it helps the person who receives it but it also changes you into the kind of person who does stuff like that.

Yes, this world is filled with overwhelming, intractable problems. We face massive “collective action problems,” as the economists call them. Systems that seem too broken to fix. Suffering too vast to address.

And yet.

And yet it falls to each of us to do what we can, where we can, with what we have.

Seneca reminds us that every person we meet is an opportunity for kindness. The elderly neighbor sitting alone on their front porch. The parent in the airport trying to wrangle their toddlers and carry-ons through security. The coworker who seems to be overwhelmed. How are you doing? Do you need anything? Can I help you with that? These opportunities are everywhere, every day. The question is whether we see them. Whether we take them.

Of course, you don’t need to donate to a fundraiser to make a difference. Money isn’t the only currency of generosity. You can give your time. Your energy. Your attention. Your patience. Your kindness.

You can go on hoping or holding your breath until you’re blue in the face, Marcus Aurelius writes in Marcus Aurelius. People are going to keep doing what they do. If you want to feel good, if you want to see good…you’re going to have to do it.

I’ve been disappointed and appalled at the idea of SNAP benefits being used as political leverage (to almost complete indifference) here in the U.S the last month. So after seeing our local food bank post about the overwhelming demand they were facing, my wife and I walked over and covered a big hole in the budget. In anticipation of everyone moving the announcements of their Black Friday sales up, we thought, hey, let’s move up our food drive too.

So that’s what we’re doing!

We donated the first $30,000 and I’d love your help in getting to our goal of $300,000—which would provide over 3 million meals for families across the country! (Just head over to dailystoic.com/feeding—every dollar provides 10 meals, even a small donation makes a big difference.)

The point is: It’s on us.

We don’t control what’s happening globally, but we do control how we act locally. We control who we are. We control what we do.

If you want to feel better, do better. Do more.

Give.

Give enough that it hurts…and see how great you feel.

Do something nice for someone else.

It makes life better for them.

And I promise—it will make you feel better too.

November 5, 2025

I Stopped Caring About Results (And Started Getting Them)

The week after my first book came out in 2012 was rough.

I mean, it wasn’t actually rough. I was twenty five. My rent was $900 a month for a beautiful two room apartment in the Garden District in New Orleans. I was with the girl I would eventually marry and I’d just put out my first book.

I should have felt like everything was amazing.

Instead I was in almost debilitating physical and emotional pain…and it was all self-inflicted.

Traditionally books come out on Tuesdays and first week sales account for all pre-orders plus whatever comes in between launch and that coming Sunday. And then, you don’t find out whether you landed on the New York Times bestseller lists until late in the day on Wednesday. In those days, there was another equally important list—put out by the Wall Street Journal—that was made public sometime on Friday.

I’d actually had a great sales week—and great media coverage too—but that middle period of the waiting, that was the reason I was in pain. I was torturing myself in anxiety and anticipation (and alternatively dread) about whether I would make it or not. I’ve said before, but with that first book, Trust Me I’m Lying, I was probably 10% proud of what I’d done and 90% waiting for this news to decide whether I had succeeded or failed. Years of my life had gone into it, I was already so blessed—I got to do my dream, publish a book!—and yet it all hung on how a group of faceless gatekeepers decided to evaluate the numbers that week (because, like so many things in life, even objective sales numbers are not actually objective).

In short, I was doing the exact opposite of what the Stoics teach. I had attached my identity, my happiness, my pride to something I did not control.

So of course I was miserable!

And of course, I was crushed when I didn’t hit the Times list…and only moderately relieved when good news came about WSJ two days later.

I’ll tell you, I’m not proud of how I acted in that interminable waiting period (according to my wife, I was awful to be around). But I am proud of how far I’ve come since then.

I don’t mean I’m proud that I’ve hit the lists a bunch since then (I have) but…that is no longer something I think much about.

I once read a letter where the great Cheryl Strayed kindly pointed out to a young writer the distinction between writing and publishing. Writing is all the things that are entirely in your control—the work, the hours at the desk, the ideas you wrestle onto the page. Publishing is all the things that are not entirely in your control—acceptance and rejection letters, the size of your advance, the sales numbers, the bestseller lists, the reviews, the invitations, awards, how it lands with readers, whether bookstores stock it, press bookings.

It’s not that the publishing stuff is not important, it’s just that in focusing on them, people often ignore the basic things that precede them—the stuff that it is impossible to succeed without.

And this is true in all domains.

Look, from the outside, it probably seems like people like Tom Brady are obsessed with winning. You see them breaking the tablet on the sidelines when the game is going poorly or you hear about how famously competitive they are and this makes sense. Obviously to win that much you have to really care about winning, right?

What Tom Brady’s actually obsessed with, he has said, is trying “to get a little bit better each day.”

He wanted to improve the accuracy of his throws a little bit. He wanted to get the ball out a little bit faster. He wanted to make his reads a little bit better. He wanted to be a little bit better as a leader. He wanted to recover after games a little bit faster. Because it’s getting a little bit better every day, compounded over a long enough time, that leads to results.

It’s the same distinction as writing vs publishing. Brady’s obsessed with performance—his performance—and that translated into a lot of Super Bowl victories.

As I’ve locked more into writing and tuned out publishing, more on the parts in my control than the parts outside my control, the funny thing is that my results have gotten better the more I have flipped this ratio.

It’s a strange paradox. That you could get results by not thinking about them?

I think this is because the fixation on externals, on things outside your control—whether winning a championship, hitting a bestseller list, or making [$$$,$$$$$,$$$$]—carries a hidden cost. It consumes a significant amount of time and energy that would be better spent doing things that actually generate those results. A musician chasing a spot on the charts churns out derivative work, never finding their unique sound. A speaker fixated on the audience’s reaction loses their train of thought. A swimmer who glances over at the competition or up at the finish creates drag and slows down. Have you ever golfed? You know what happens when you pull your head up to follow the ball.

I’m not saying you shouldn’t strive to accomplish great things or to do and be all that you’re capable of—you definitely should. Obviously external results do matter to a degree. If my books stopped selling, my publisher would stop publishing them.

I’m just saying you need to make sure you’re running the right race.

Epictetus quipped that, “You can always win if you only enter competitions where winning is up to you.” The bestseller list? That’s up to the New York Times. Winning a Grammy? That’s up for the Recording Academy. A Nobel Prize? That’s up to the folks in Stockholm. Even competitive goals like being the fastest person in a race or the richest person in the world—these depend on what your competitors do.

What is in your control is showing up, giving maximum effort, following your training, sticking to your principles, pursuing your calling. If that translates to on the field success, great—in fact, it almost always does. If that translates into career recognition, awesome—and again, it usually does.

Many great artists have talked about this—this paradoxical way results tend to be an accidental byproduct, coming to those who don’t directly pursue them. The comedian Mike Myers once said this was his advice for young creators: “Don’t want to be famous…fame is the industrial disease of creativity. It’s a sludgy byproduct of making things.” Bruce Dickinson from Iron Maiden would say in an interview, “I’m not interested in being famous. Fame is the excrement of creativity, it’s the shit that comes out the back end, it’s a by-product of it.” And Viktor Frankl would talk about how “strange and remarkable” it was that Man’s Search For Meaning became such a success because he wrote it not to “build up any reputation on the part of the author.” After the book sold millions of copies, Frankl shared what that taught him: “Don’t aim at success—the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect of one’s dedication.”

Perhaps this is what Eugen Herrigel is talking about in Zen in the Art of Archery. The more you’re aiming, the less you’re focused on your form, the more distracted you are, the more tense you are. Your willful will causes you to miss.

One night just last week, the week after Wisdom Takes Work came out, I was hanging out with my kids when I glanced at the home screen of my phone and could see there was a text from my agent, Steve. I knew what that text was probably about…so I ignored it.

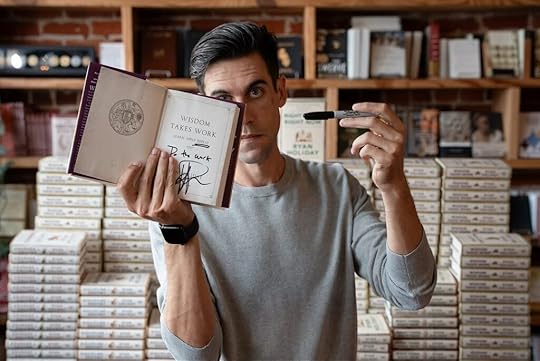

The next morning, after I got my boys to school and went for a run, I was sitting in the anteroom, going over some letters I am reading for my next book. Remembering that Steve was catching a flight out of the country later that day, I called him back. He told me the good news: Wisdom Takes Work debuted at #2 on the New York Times Bestseller list, and is on pace to be the best selling book in the Four Virtues Series.

“That’s incredible,” I said. “Now, I’m going to get back to work.”

Don’t get me wrong—I’m deeply grateful to the readers who got the book on the bestseller list. It’s crazy and humbling. In fact, to the extent I do think about a book’s success anymore, it’s the readers I think about. They not only give me the satisfaction of knowing the work is having an impact, but they give me the great fortune of being indifferent to things like bestseller lists—their trust and support matters more.

In Perennial Seller, I quote Stefan Zweig, “I had acquired what, to my mind, is the most valuable success a writer can have—a faithful following, a reliable group of readers who looked forward to every new book and bought it, who trusted me, and whose trust I must not disappoint.”

In that sense, I was pleased to hear the news that Wisdom hit the bestseller list. I took it to mean that I built that following. It also meant, though, that they trusted me and I had to do my best as a writer to live up to that. I didn’t owe anyone or anything to anyone else. There wasn’t anything else to focus on but that work, which is what I meant when I told Steve I was getting back to the pages in front of me.

Compared to that nervous, anxious, desperate twenty-five year old waiting for good news almost fifteen years ago, I had come a long way. The news hardly changed my opinion about the work I had done…and it didn’t change what I knew about the work I still had to do.

The idea is that you enjoy the process, the part that’s up to you.

This sets you up for good results and it also means that when you’re fortunate enough to get them, they are extra as opposed to validation.

As they should be.

October 29, 2025

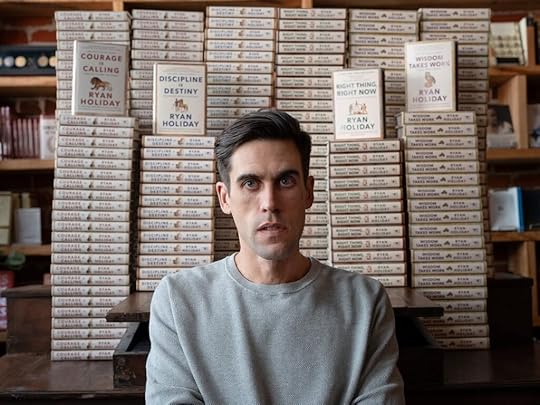

What You Work On Works On You (This is What The Last 6 Years of My Life Have Been)

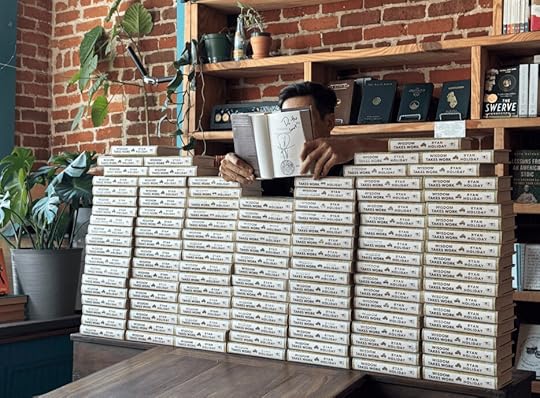

My latest book, Wisdom Takes Work, is officially out and you can get a copy wherever you buy books! Thank you to everyone who has picked up a copy. The support has been incredible—and honestly, a little overwhelming. Our small team here at The Painted Porch is working hard to get every order out the door as fast as we can. If you’re still waiting on yours, we really appreciate your patience. Believe me… I have been working on this series for 6 years—I can’t wait for you to read the new book!

In the summer of 2019, my wife and I took our two sons for a hike in the Lost Pines Forest in Bastrop, Texas.

It was a Saturday or a Sunday.

I had a bunch of articles to write, but I put it aside and decided to spend some time outside with the kids in the shade of the prehistoric loblolly forest about thirty minutes from our house.

It was a lovely afternoon, despite the heat. I always love Lost Pines because it’s a freak of nature. The tall prehistoric loblolly pine trees appear here in the middle of Texas, hundreds of miles further east than most of their counterparts. Much of the forest still shows scars from two 2011 wildfires that burned tens of thousands of acres—one of them the worst in Texas history—only adding to the mystique and making parts feel like a haunted elephant graveyard.

As we wrapped up the hike and took the kids to the playground, suddenly, it hit me. It was a feeling that creative people experience from time to time. You’re in the middle of not working–you’re in the shower or your drifting off to sleep or you’re in the middle of sweeping the floor–and boom, you get hit with an idea. I have run many hundreds of miles in Lost Pines so it was a familiar feeling—I’ve sold business problems and writing problems and personal problems on the trails there.

As I was carrying my son in the backpack, my mind had drifted briefly to the fact that my book Stillness is the Key would soon be released and it would mark the end of what had become a three-book trilogy. What would I tackle next?, I thought. This was 2019. The political situation was a mess. There were wildfires, earthquakes, wars dragging on, terrorist attacks. There was chaos, upheaval, and uncertainty. “A book about courage would be cool,” popped into my head. I shared the idea with my wife. We talked it over along the trail, and by the time we were loading the kids in the car, an idea for one book had become an idea for a series on the four virtues, starting with courage!

And like that, my next creative mountain had been laid out in front of me.

I’ve been thinking about this story lately because here I am, six years later, coming to the end of that series, as the fourth and final book, Wisdom Takes Work, came out last week.

There was a period a couple of years ago where I didn’t think I would be here having completed the series. It was around the halfway mark, working on the second book in the series, Discipline is Destiny, and I hit a wall.

Coming up with the idea for a book—or in this case, a series—is a fun, creative act. Actually creating those books is a work of excruciating manual labor, sitting in a chair, grinding out each consecutive sentence—a process not measured in hours or days, but months and years. It’s a marathon of endurance, cognitive and physical.

For me, in the last decade, I have run not just a couple of these marathons but twelve of them, back to back to back. That’s roughly 2.5 million words across titles I’ve published, articles I’ve written, and the daily emails that I produced in the same period.

During that time, there was a destabilizing, devastating global pandemic. There were fires, floods, and freezes. Demagogues and wars. Market crashes and inflation. Technological disruption. My kids growing up. My wife and I opening and running a small town bookstore.

So I was tired. Just really tired.

I’m not someone inclined to believe in divine intervention. But I needed help . . .

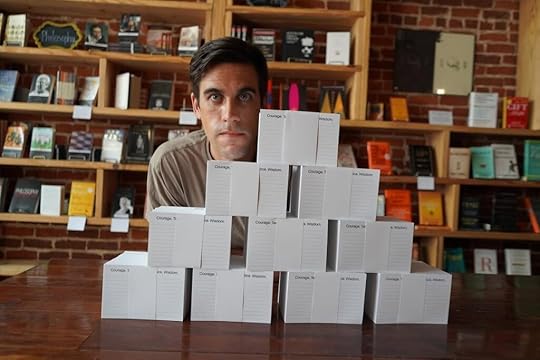

On a sweltering-hot day in Texas, I was sitting at my workroom table in my office above the bookstore. The air conditioner wasn’t working and I wasn’t sure if we could afford another one for the building. It was my 34th birthday. Sweating, exhausted, and on the verge of a crisis of confidence—that I had the wrong topic, I didn’t have the material, and contemplating whether to call my publisher and ask for a delay—I went through boxes that contained thousands of note cards of research. As a whole, they overwhelmed me—what they contained, the way they might fit together to produce a book, seemed impossible to comprehend. I reached out and grabbed one.

It had just two dozen words scrawled in red Sharpie. When was it written? Why had I written it? What had prompted me? All I know is what it said.

Trust the process. Keep doing my cards. When I check them in June—if I have done my work—there will be a book there.

It wasn’t exactly a miracle . . . but defying space and time, I had traveled from the past into the future to deliver a reminder of self-discipline.

And guess what? It was exactly what I needed.

It didn’t save me from the work, of course, but from myself. From giving up. From abandoning the system and process that had served me so well on all those books and articles and emails. In one of the best passages in Meditations, Marcus Aurelius, almost certainly in the depths of some personal crisis of faith, reminds himself to “Love the discipline you know, and let it support you.”

That’s what my note said to do.

I listened.

I began showing up at the office earlier each day to work with my material. Card after card, I sorted them into tiny little piles. Looking for connections, for threads I could follow, for the key that would unlock the book.

Instead of worrying, I used the calm and mild light of the philosophy I have written about in my books. I went for long walks when I got stuck. I tried to follow my routine. I tuned out distraction. I focused. I also sat—just sat—and thought.

I’d love to be able to tell you that shortly after this the book just clicked. But that’s not how writing, or life, works. What actually happened was slower, more iterative, but also in the end, just as transformative.

As I walked that long hallway of doubt and despair, as I kept doing my cards, light began to creep in. Lou Gehrig and Angela Merkel stepped forward from the shadows. After nearly four thousand pages of biographies, Queen Elizabeth entered as a portrait of temperament. Napoleon, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and King George IV jumped out as cautionary tales, stunning examples of self-inflicted destruction. One character after another slowly, painstakingly, chapter by chapter, became discernable.

The book was there, as my note promised me. Now I had to write it.

While a book requires many, many hours of work, these hours come in rather small increments. If I get to the office at eight thirty, I could be done writing by eleven. Just a couple hours is all it takes. Just a couple crappy pages a day, as one old writing rule puts it. The discipline of writing is about showing up. No delays, no procrastination, no digital distractions. Just writing.

The seasons changed. World events raged and spun as they always do. Opportunities, distractions, temptations, they did what they do too—popping up, pinging, nagging, seducing.

Day after day, I kept after it. I trusted the process. I loved the discipline I knew. I let it support me.

As I finished the book, I was still tired. Every writer is tired when they get to the end of a book. Yet, I also felt wonderful. I thought it was to date some of my best writing, but what I was proudest of is who I was while I wrote it. A less disciplined me, a younger me, would have been wrecked by that period where it felt like the book might not come together. I would have acted out. I would have been consumed. But the work had been working on me—as I worked from home on the final pages of Discipline, my five-year-old looked up from his art project and said, “I’m sorry you lost your job writing books, Dad.” Apparently things had been so much less crazy and my boundaries had been so much better that he thought I wasn’t working anymore!

But I was, of course. I was in the process. Doing my cards. Trusting the discipline I knew would lead to the next book, Right Thing Right Now, and the final one, Wisdom Takes Work.

As a result, here I am—having read over 500 books of research, made 10,000 note cards, published 300,000 words (with tens of thousands of additional words cut) and 1,400 pages—drawing the series to a close.

When Edward Gibbon finished The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, he noted his sadness at taking “everlasting leave of an old and agreeable companion.”

I don’t feel that way, though, because of everything I learned during these past six years spent working on the series, the clearest lesson of all is that virtue isn’t something you take leave of. It’s not something you ever fully possess. It’s not something you commit to just for a little while, but for a lifetime.

There’s still a long way to go, but I’m proud of the progress I’ve made. I’m proud of what I have put to the page in each of the four books. And I’m proud of how I’ve improved both as a writer and a person through it all. I am calmer. I am quieter. I argue less. I get upset less. I admit I am wrong more often. I’m a little wiser, a little more disciplined, just, and courageous than I was on that hike in the summer of 2019.

I close the virtues series, but the ideas are still working on me. I am doing my best to live up to them. To be more community-minded. To be braver, stronger, kinder, wiser.

Day by day. Page by page. Struggle by struggle.

I hope you do the same.

…and now I go onto my next project.

If you haven’t checked out Wisdom Takes Work , it would mean so much to me if you could. It came out last Tuesday. Here’s me talking about it on The Daily Show and on The Breakfast Club .

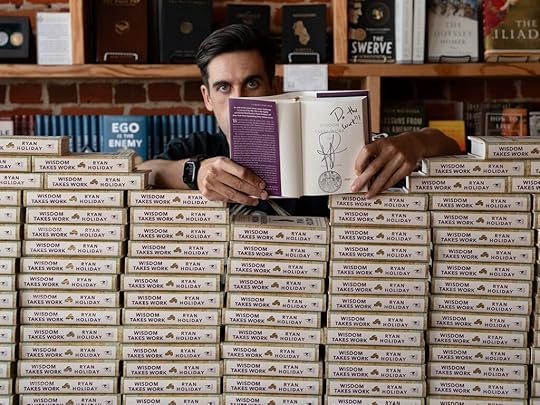

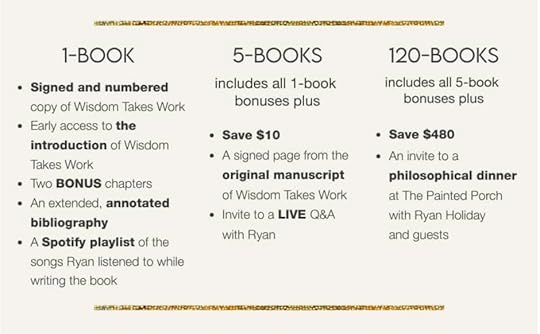

We still have some signed first-edition copies of Wisdom Takes Work left—and will be extending our preorder bonuses for folks who buy the book this week. Bonuses include cut chapters and the annotated bibliography with all purchases, or a signed manuscript and even dinner with me if you buy more copies.

If you’re interested, grab your copy now before it’s too late.

October 15, 2025

Without This, You’ll Never Reach Your Potential

My new book, Wisdom Takes Work, comes out in 6 DAYS! If you’ve gotten anything out of my writing over the years, it would mean the world if you preorder a copy. Preorders are the single best way to support an author and help a book get off the ground. To make it worth your while, I’ve put together a bunch of bonuses—a signed page from the original manuscript, bonus chapters, an annotated bibliography, and more. Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

There I was at 19 years old, sitting across from the great Robert Greene at The Alcove in Los Feliz.

He was talking about all the trouble he was having finding a good research assistant.

I had to restrain myself from jumping over the table.

This was literally my dream job.

Fortunately, before I leapt out of my chair, Robert asked if I might have any interest in giving it a shot.

Thus started for me what Robert calls in Mastery, The Apprenticeship Phase.

It didn’t start with anything glamorous. In the days before AI or even decent software, I spent hours transcribing interviews he had done for his book The 50th Law. I read obscure books he didn’t want to waste time on. I found articles. I worked on his website. I went to libraries and scanned pages. I went through old archives. I tracked people down.

And in between, I asked questions. I listened. I watched. I absorbed his research and note card system, which I continue to use to this day.

Obviously he was paying me, but I always considered having access to him—being able to ask these questions—my actual compensation. The feedback wasn’t always fun, but what would he have normally charged someone as a consultant? How many people would have killed to be able to call him or email him about anything?

When I say I was his apprentice, I don’t mean it like, “Oh, I was his intern for a few months.” I did this for close to 7 years, even after I became the director of marketing at American Apparel. I was even doing it even after I had gotten my own book deal and was working on my first books.

Why?

Because this is how it works.

As the great Jack London writes in his novel Martin Eden, “no matter how peculiarly constituted a man may be for blacksmithing, I never heard of one becoming a blacksmith without first serving his apprenticeship.”

In Wisdom Takes Work—which there are just 6 days left to preorder!—there are multiple chapters on the art of cultivating these mentors and teachers because there is no one who is able to reach their potential totally alone. There is no one who can learn everything they need to learn by trial and error. Wisdom is not a solitary pursuit. It is often a collective effort.

For thousands of years, this is how trades—and life—were taught. Not in a classroom with hundreds of other students, but attached to a professional, who taught, largely by example, until the student was ready to head out on their own. There are some things, the tennis great Billie Jean King would say of her time training under Alice Marble, an eighteen-time Grand Slam Champion, “you can only learn from someone who’s been the best in the world.” Or at least, someone who is world class.

It was from Robert that I learned everything—literally everything—about being a writer. He taught me how to write a book, how to think about books, how to research them, how to market them, how to work with a publisher. He fundamentally taught me, from beginning to end, how the entire process works. In addition to telling me what to do, he showed me how a real pro does the job.

We have to find the people who can teach us and open ourselves to learning from them. Whatever stage of life we’re in, there is someone who knows more than us, who has been through more than us, who can open doors for us.

We are a product of our teachers and our mentors.

There would be no Plato without Socrates. There would be no Aristotle without Plato. There would be no Alexander without Aristotle. There would be no Marcus Aurelius without Rusticus or Epictetus or Antoninus. There would be no Zeno without Crates, and thus there would be no Stoicism without Crates.

Do you know what Crates’s nickname was in ancient Athens? He was known as “the door-opener.” Because that’s what great mentors and teachers do: They open doors to worlds we didn’t even know existed. They invite us into things we wouldn’t have discovered on our own. They help us see possibilities we’d otherwise stay blind to.

How do you find these door-openers? How do you attract their attention? How do you make yourself worth their while?

You have to show yourself as somebody with the hunger to learn and excel. You have to show yourself as somebody who listens. Somebody who is curious. Somebody who is worth teaching. Somebody who is coachable.

Mentors give us books to read. They give us problems to solve. They give us riddles to chew on. They provide an example that inspires or even shames…and sometimes cautions.

The process is not always fun. It will often be painful. As Epictetus would tell his students, having modeled himself on his mentor Musonius, “The philosopher’s lecture hall is a hospital. You shouldn’t walk out of it feeling pleasure, but pain, for you weren’t well when you entered.”

Valuable things are rarely free. An apprenticeship is one of them.

But it’s also priceless.

I wouldn’t be here without it.

There’s no way I can repay Robert for his kindness and his patience and his generosity. But as I explain in the “Grow a Coaching Tree” chapter in Right Thing, Right Now (the third book in the Virtue Series), as well as in the “Be a Teacher” chapter in Wisdom Takes Work, the only thing we can do is pay that forward. The next step is to become a teacher, to help mentor someone else.

Because we learn as we teach.

Because we carry debts from those who helped us—debts that can only be discharged through helping others.

And because, at the end of your career and your life, you’ll be prouder of what you helped others accomplish than what you achieved yourself.

But only if you put the work in now…working as hard to open doors for others as you work to open doors for yourself.

***

For the past six years I’ve been lavishing all my working hours on the Stoic Virtues series and I can honestly say Wisdom Takes Work , the fourth and final book in the series, is the culmination of my life’s work.

There are just SIX DAYS left to pre-order Wisdom Takes Work !

Each time I release a book, I like to do a run of preorder bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, early access to the introduction, bonus chapters, and even an invite to a philosophy dinner at my bookstore, The Painted Porch.

Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

October 8, 2025

Do You Know How To Do A Deep Dive?

My new book, Wisdom Takes Work , comes out in 13 DAYS! If you’ve gotten anything out of my writing over the years, it would mean the world if you preorder a copy . Preorders are the single best way to support an author and help a book get off the ground. To make it worth your while, I’ve put together a bunch of bonuses—signed and numbered first editions, a signed page from the original manuscript, bonus chapters, an annotated bibliography, and more. Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

I thought I knew a lot about Lincoln.

I’ve read biographies—an embarrassing amount of them honestly. I’ve watched documentaries. I’ve interviewed scholars. I’ve traveled to many of the sights. I’ve read many of his favorite books. I’ve immersed myself in the world he lived in. I once stood transfixed, for hours, in front of Krzysztof Wodiczko’s art piece, which projected the faces and experiences of American veterans on the face of Lincoln’s statue in Union Square Park in New York.

I’ve even written about him quite a bit in my books.

So when I sat down to put together what was intended to be Part III of Wisdom Takes Work, I thought I was set.

It turns out I wasn’t even close.

I was stuck and I could not find the words. That might seem like writer’s block but it wasn’t—because writer’s block doesn’t exist. What is real is lacking material and that’s what I was facing.

So I got to work.

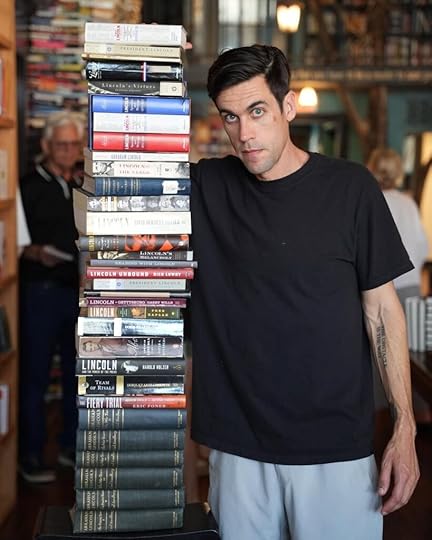

I read Michael Gerhardt’s 496-page book on Lincoln’s mentors.

I read Hay and Nicolay.

I read Doris Kearns Goodwin’s 944-page Team of Rivals.

Still, there was more to know.

So I read David S. Reynolds’s 1088-page Abe, David Herbert Donald’s 720-page Lincoln, and Garry Wills’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book specifically about the Gettysburg Address (Wills’s book has many more pages than the address has words).

I spoke with the documentarian Ken Burns about him, and Doris too.

I went back through the books I’d already read (William Lee Miller, especially, but also Harold Holzer, Joshua Wolf Shenk, and Carl Sandburg).

I read Lincoln’s own writings, his letters and his speeches.

I reviewed my pictures from trips to Gettysburg, Antietam, and Ford’s Theater.

I went, multiple times in the course of writing the book, and looked up at the Lincoln Memorial.

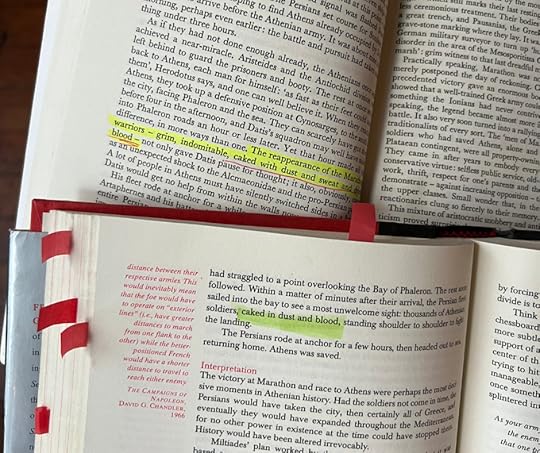

In the end, I spent hundreds of hours reading thousands and thousands of pages on the man. Here’s what that looks like in physical terms.

Basically, what I was doing was a deep dive. Fittingly, Lincoln’s own education was itself a kind of lifelong series of self-directed deep dives. He got his start in law, for instance, when he met a lawyer named John T. Stuart, who allowed Lincoln to borrow some of his law books. “If you wish to be a lawyer,” Lincoln would later tell a young man, “attach no consequence to the place you are in, or the person you are with; but get books, sit down anywhere, and go to reading for yourself. That will make a lawyer of you quicker than any other way.”

His campaign against slavery, too, began by going deep. “He searched through the dusty volumes of congressional proceedings in the State library,” William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner, recalled, “and dug deeply into political history.” His way, Herndon observed, was to dig up a question by the roots and dry it out by the fires of the mind, until he could see it for what it was.

Do you know what Lincoln did after the Civil War broke out? He broke out an old habit, which he’d had since his time in Washington as a congressman: He called for books from the Library of Congress, reading everything he could about strategy and tactics, including books published by his own generals. He was, by the end of the war, according to General W. F Smith, “the superior of his generals in his comprehension of the effect of strategic movements and the proper method of following up victories to their legitimate conclusions.”

Nowhere was this ability to see things plainly more evident than in the Gettysburg Address, which was just 271 words long. You might think such a short speech was easy to write, in fact, it was the descendent of a decade-plus-long deep dive into language, elocution, rhetoric, history, law, politics and the founding ideals of the nation—a word he repeated in the speech five times. It was an expression of the work Lincoln did to get to the “nub” of a subject, as his law partner said. As Wills writes in Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, Lincoln was able to, as a result of his masterful understanding of the issues and opportunity at hand, to effectively redefine and refound the nation in a single speech, in a way that two and a half years of war had not been able to.

Going deep in order to get to the nub of subjects—this is a skill you need to have. Whether you are an author, a politician, a lawyer, entrepreneur, scientist, educator, parent—it doesn’t matter you have to be able to pursue an idea, a question, a thread of curiosity until you’ve wrapped your head completely around it.

In Right Thing Right Now, I spend a lot of time talking about the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, who like Lincoln was able to strike a defining blow against slavery. Obviously this is what we’re talking about when we talk about justice. But how did he do it? Clarkson knew slavery was wrong. He even wrote a convincing essay on it.. But he soon realized that if he was going to do something about it, he would really have to understand slavery—as a business, a logistical enterprise, and a set of cultural assumptions passed down for thousands of years to justify it. So he immersed himself in the abolitionist movement, meeting and learning from the earliest activists, reformers, and freed slaves. He visited slave ships. He would recall that the almost uninhabitable quarters, the chains and grates, filled him “with melancholy and horror,” kindling, he said, “a fire of indignation.” But now his anger was fueled by facts, and he wanted more. He spoke to everyone he could find who had been to Africa, recording their accounts in his notebooks. He scoured records at the Custom House, poring over muster rolls, ship logs, trial transcripts, and insurance files.

Often falling asleep over paperwork, surrounded by his research, Clarkson persisted for years. By the end, no one knew more about the slave trade—he was more informed than many traders and investors themselves, since so much of what they did depended on deliberate ignorance.

You can’t solve a problem you don’t understand. You can’t lead a field you haven’t immersed yourself in. You must go down the rabbit hole. You must go deep. You must swarm the topic.

This has been my approach to pretty much everything I’ve done since dropping out of college. It’s how I figured out how to be a writer. It’s how I figured out how to be a researcher. It’s how I figured out how to be a parent. It’s how I figured out how to run a bookstore. Indeed, my whole life has been built on deep dives.

If our goal is to get not just smarter or more knowledgeable, but wiser, we cannot be content to learn in half measures. We must go as deep as we possibly can. We don’t just read a book on a topic. We have to read everything we can find on it. We don’t just ask a question or find an expert. We have to find every expert we can and ask them every question they’re willing to answer. We don’t just look at what’s there. We have to explore the remotest corners, every facet, from every angle. We have to hear from people we agree with and from people we disagree with. We have to go out and get real experience.

As an old man Marcus Aurelius would reflect on the most important lesson he had learned from his philosophy teacher Rusticus: “to read attentively—not to be satisfied with ‘just getting the gist’ of things.” Go “directly to the seat of knowledge,” he said. Immerse yourself in the craft, business, sport, or profession. Seek out tutors and mentors and peers. Travel. Observe. Ask questions. Go way beyond the “gist.”

The great biographer David McCullough talked about swarming the subjects he wrote about—reading their diaries, their favorite books, biographies of their heroes, newspapers from their time, and, most importantly, spending time in the places they had spent time. “I believe strongly,” he once said, “that terrain, landscape, the physical environment is not just important in understanding someone or something—it’s elemental. Therefore, I go to where things happened.”

The jazz legend Miles Davis didn’t just go down to the club and listen to music. “I would go to the library and borrow scores by all those great composers, like Stravinsky, Alban Berg, Prokofiev. I wanted to see what was going on in all of music,” he explained. All of music. Old stuff. New stuff. The greats. The weirdos. “Knowledge is freedom and ignorance is slavery,” he said, “and I just couldn’t believe someone could be that close to freedom and not take advantage of it.”

The Wright brothers didn’t discover flight through a single epiphany but through countless hours watching birds. “We couldn’t help but thinking they were just a pair of poor nuts,” one Kitty Hawk resident recalled. “They’d stand on the beach for hours, watching the gulls flying, soaring, dipping.” They even studied how paper fell and floated to the ground, again and again.

Wilbur’s notebooks are filled with drawings of birds, notes on flight techniques across species, and how weather affected flight. They include sketches of wind-tunnel tests and designs. Others had observed birds, but no one had gone so deep—or spent so much time—studying the mechanics of flight and wings.

To capture the progression from ignorance to knowledge to wisdom, McCullough used the example of the pilot’s cockpit. You can get a pretty good understanding from someone describing what a cockpit is. An even better understanding from reading about cockpits. An even better understanding from looking at pictures. An even better understanding from watching videos. An even better understanding from sitting in a cockpit. And an even better understanding from flying a plane.

This is our job. To make things clear. To get to the nub of things. To find what is important and discard the rest. To go deep. To swarm.

This, of course, takes time.

It takes curiosity.

It takes patience and persistence.

Most of all, as I put in the title of the new book, it takes work.

***

For the past six years I’ve been going deep on the four virtues, and I can honestly say Wisdom Takes Work , the fourth and final book in the Stoic Virtues series, is the culmination of my life’s work.

The book comes out October 21st, but it would mean the world to me if you could preorder the book from dailystoic.com/wisdom . Preordering a book is the number one thing you can do to support an author as they get a book off the ground. It’s how publishers determine how many copies to print, whether other bookstores will carry it, and where the book will land on the bestseller list.

To make ordering it early worth your while, I put together a bunch of bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, a signed page from the original manuscript, bonus chapters, an annotated bibliography, and a bunch of other stuff. Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

October 2, 2025

This Hobby Can Change Your Life

My new book, Wisdom Takes Work , comes out in a few weeks. Get signed & numbered first editions here !

I have a hobby and it’s weird.

It started in a pretty normal way.

I’d always liked taking walks and then I had young kids.

Because it was often the only way I could get them to sleep–or to keep them out of the house so my wife could sleep–I would spend hours and hours walking on the rural country road that we live on.

It is unpaved and unmaintained by the county or the state, lined with trees, and more frequently crossed by deer and jack rabbits than people. We’d do miles and miles, first in the baby bjorn, then the single stroller and then the double stroller. We see the sun come up or the sun go down. We crunch the frost and the mud. We’d do it in the heat and the cold, on ordinary days, for the interminable months of the pandemic, weekdays and weekends, rain or shine.

It’s a throwback to an older, simpler way of life.

It’s also a throwback to a scene I’ve always remembered from Mad Men, where Don Draper and his family finish their roadside picnic and then nonchalantly throw all their trash into the grass below.

Only out here, because the police don’t seem to mind or our local government is non-existence, they dump tires and old mattresses. They dump debris from construction sites. They dump beer bottles and candy wrappers. They dump out of season deer kills and for some inexplicable and alarming reason, a lot of dead dogs.

At first, this just pissed me off—especially because the nails kept giving me flats. It would make whole segments of the road unwalkable with the kids because of the stench. I tried calling the police and animal control and my local politicians—of course, they did nothing. I put up fake cameras which did nothing to deter. I thought about moving.

But then one morning on my walk with my kids, a thought hit me that was both freeing and indicting. How many times do I have to walk past this litter, I thought, before I am complicit in its existence? Why do I keep expecting someone else to do something about it if I won’t? So I started cleaning it up…and I actually enjoyed it. We started cleaning it up.

I have a bag, one of those sticks with a spike on it, and I go up and down the country roads where we live. I have a claw and gloves (I have gone through many many pairs of gloves). I go down in the gullies by the side of the road picking up soda bottles, plastic bags, food wrappers, nails, and screws. I have disposed of dumpsters worth of garbage over the years. I have loaded tires into the back of my truck and paid to have them properly recycled. (I’ve even paid a contractor to come out with a tractor for some particularly heavy stuff). I have put on face masks and scooped up dead goats, dead calves and dead dogs which I burned or took to the back of my ranch to decompose in a less disruptive place. I have paid my children an ungodly amount of bribes to get them to participate too.

I don’t just do it at home either. I do it when we go to the beach. I do it when we go on hikes. I do it when I’m pacing in a parking lot, taking a phone call. I think I’d want someone to grab this if they saw it, so I’ll do the same.

Does it make a difference? In the big scheme of things, no. Does it create a moral hazard? Maybe. Perhaps word has gotten out—dump your stuff down here because it mysteriously disappears a few days later.

I’m not sure my neighbors have noticed. In fact, one time, as I loaded up a mattress in my truck, someone who lives down the road accosted me, thinking I was the dumper. Honestly, the only time anyone has ever said thanks happened in another country. I was in Greece this summer and I passed a flattened water bottle in the street, which I reached down and grabbed and tossed in a nearby trash can. An old man sitting in a cafe stood up and began clapping and bowing and shouting in unintelligible Greek. I assume he was saying thanks, but maybe he was making fun of me.

I’ll tell you it doesn’t earn you karma, not at least during this lifetime. Despite all the work my wife and I still get a flat tire every month or so.

But that’s not why I do it.

I do it for me.

In a world where everything seems to be falling apart and so much is beyond my control, there is something deeply empowering about this simple, weird act. I can see the difference every time I drive home—the road is cleaner, safer, more beautiful. I’m outside instead of stewing indoors. I’m moving instead of scrolling. I’m solving a problem instead of complaining about it.

There is a Mr. Rogers quote I love. “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news,” Rogers said, “my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’”

We decide what we look for in life—do we get mad at the people making the mess or do we look towards the people cleaning things up? We decide whether to despair or find hope and goodness.

But I actually think we can go further. Do we decide to BE one of the helpers? Do we decide to pick up the trash? Do we take ownership of the things within our control?

That’s what makes the difference…and life better for everyone, but especially you.

***

For the past six years I’ve been lavishing all my working hours on the Stoic Virtues series and I can honestly say Wisdom Takes Work , the fourth and final book in the series, is the culmination of my life’s work.

Wisdom Takes Work is a book about the work of our lives: the work it takes to acquire wisdom. The book is filled with the example and insights of some of history’s wisest people, and how we can follow in their footsteps.

It comes out on October 21st, but is available for preorder over at dailystoic.com/wisdom . Each time I release a book, I like to do a run of preorder bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, early access to the introduction, bonus chapters, and even an invite to a philosophy dinner at my bookstore, The Painted Porch.

September 17, 2025

We Must Not Devolve Into This (Or We Risk 2,500 Years of Progress)

Before we get into it…with the upcoming release of Wisdom Takes Work —the fourth and final book in my Stoic Virtues series —we’re doing a collector’s set of all four books . There’s a limited run of these, so pre-order them here today . I’m also giving a talk in San Diego in February about applying the Stoic virtues to modern life and modern problems. Grab seats and come see me !

On the night of April 4, 1968, Robert Kennedy, then running for president, was about to give a speech in inner-city Indianapolis when he got the news that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated.

It had already been a grueling campaign. It had been a painful few years. And now, another murder, more violence.

Kennedy was the one who had to break the news to the milling crowds that King, their leader, was dead. The crowd, roiling with anger and despair, was on the verge of riot.

His prepared marks woefully insufficient for the moment, Kennedy began to riff. It was a crossroads moment, he said: “In this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in…You can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization. Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.”

To those tempted to move in the direction of hatred and revenge, Kennedy said, “I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling,” for his own brother had been struck down the same way just five years earlier. But he also knew personally what a dark and empty road that was. “We have to make an effort in the United States,” he said, “we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.”

Then, he drew on a line from one of his favorite books, The Greek Way by the classicist Edith Hamilton. On a ski vacation four years earlier, Kennedy was loaned a copy of the book and ended up spending most of the trip holed up in his room, absorbed in Hamilton’s wonderful discussion of what made the Greeks so special, what they can teach us, and how they thought about life. It was from her book that he had read a line by the ancient Greek poet Aeschylus that stayed with him. And there in Indianapolis, from memory, he recited it:

“In our sleep, pain, which cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.”

“What we need in the United States is not division,” Kennedy explained. “What we need in the United States is not hatred. What we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness. [What we need is] love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black.”

He urged the attendees to return home and to pray, and offered them an alternative, a chance to take meaning from this terrible experience. “Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago,” Kennedy said, “to tame the savageness of man and to make gentle the life of this world.”

All over the country similar crowds erupted into mobs, which turned into deadly riots. But in Indianapolis that night, largely because of Kennedy’s words, the people chose peace and restraint over rage and violence.

The reality is that political violence is not unprecedented in American history. It has always been there, lurking beneath the surface of our democracy. In fact, if you’ve read Bryan Burrough’s Days of Rage (or listened to my conversation with Bryan), the statistics are staggering—in 1968 alone, there were over 2,000 terrorist bombings in the United States. The FBI reported more than 2,500 bombings on U.S. soil between 1971 and 1972, an average of nearly five explosions per day. As Burrough put it, perhaps the only thing more startling than those numbers is how completely they have been forgotten by the American public.

If we go back even further, and if you want a really terrifying look at how political violence can consume a republic, I highly recommend Mike Duncan’s The Storm Before The Storm, about Rome and the hundred years of political dysfunction that preceded Julius Caesar. In the book (and in our podcast episode together), Duncan chronicles how the normalization of mob violence, the normalization of assassinations, people breaking the rules, politicians demonizing their opponents, politicians trying to overthrow elections, people thinking that they alone were the solution to the republic’s problems led to the republic’s fall.

So again, political violence has always been there. And it can continue to be there, if we let anger and hatred take more and more of us in their direction. We can follow Rome’s path toward the normalization of brutality, where every act of violence is met with more violence. Or we can choose to go the way Kennedy talked about that night in Indianapolis—the harder path of understanding, compassion, and the ancient wisdom that teaches us to find meaning in our suffering rather than let it consume us. We can choose, as he said, to try to tame the savageness of man.

Look, pluralism is not some nice idea. It is a technology. It was invented out of the hard-won wisdom that Aeschylus talked about, largely by the American pilgrims and then the Founders, who looked backwards at centuries of religious violence. They understood that in a winner-take-all system, people would always be fighting. But in a system that allowed for a multitude of views, for freedom of expression and protecting minority views—even abhorrent ones—where the government did not pick sides, then people of all faiths and beliefs could co-exist.

I do not mean to be kumbaya about this. I also don’t want to dance around the brutality of what happened to Charlie Kirk—a father of two was gunned down by a high-powered rifle on a college campus, bleeding out before he even knew he was dying. I also won’t refrain from denouncing the inane, trollish, and stupid positions he often espoused. Charlie Kirk was a bigot and a misogynist and a homophobe. He also celebrated and encouraged political violence—not just perpetuating the lies about the 2020 election but proudly busing hundreds of people to the Capitol on January 6th, an event that erupted into an insurrection on par with Catiline’s (which he then pleaded the Fifth about in front of Congress).

No one deserves to die. George Wallace did not deserve to be shot. Neither did Martin Luther King Jr or Robert F. Kennedy. Neither did Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Health. (I was incredibly disappointed to see that the murderer Luigi Mangione had once retweeted something I’d said. Talk about missing my message!) Assassins threaten not only individual lives but the very concept of pluralism and free expression. They steal from all of us. Because now we question what we say, we question whether our rights will be respected, we question whether this project–that is to say democracy–will keep working.

We all deserve better than the level of discourse that Charlie Kirk practiced, which was the classic toolkit and style of a demagogue, but discourse is better than murder. Virtue (and just plain human compassion) also demands better than the insensitive and cruel responses to his murder…as well as the anti-democratic and authoritarian rhetoric that politicians have thrown about after. It’s shameful what people have been doing and saying…it’s essential that each of us makes the choice to not be implicated or participate in that ugliness.

I’m reminded of a recent conversation I had with Dr. Laurie Santos on the Daily Stoic podcast. She talked about an essay by the anthropologist Sarah Hrdy, who studies primates and primate interactions. In the essay, Hrdy describes the familiar experience of being crammed on a long, delayed flight filled with dozens and dozens of strangers, all cranky, tired, hungry, and irritable. “And she’s like, ‘if this was any other species,’” Dr. Santos said, “‘they’d be killing each other. No one would leave with their testicles.’ It’s amazing that we get to be in one of the few species where all that happens is somebody says a nasty thing to the flight attendant.”

What keeps us from tearing each other apart on an airplane or in society or in the middle of intense disagreements about religion or policy or events isn’t biology. It’s the social technologies we’ve developed over the past 2,500 years. It’s the political process. It’s rules, the norms, the shared agreements about how we behave and coordinate and cooperate with each other. None of which are guaranteed or permanent or self-sustaining.

They require constant work, constant vigilance, constant choosing.

They require, as Kennedy said, that we make an effort. An effort to love, to understand, to have compassion toward one another, to treat our fellow human beings like fellow human beings.

We desperately need to make that effort. We desperately need to put the genie of political violence back in the bottle.

Because once it gets out, once that Rubicon is crossed, history shows it’s incredibly hard to tame the savageness of man.

September 10, 2025

You Must Avoid Getting Corrupted By This

I’m giving a talk in Austin next week ( only a few tickets left ) and San Diego in February. Grab seats and come see me !

My study of history has led me to believe that there is a kind of dark matter inside the human race.

It’s some combination of evil, cruelty, ignorance, cowardice, mob-ness. It is a kind of dark oppositional energy that goes from issue to issue, era to era. It’s rooted in self-interest, self-preservation, in fear, in not wanting to be inconvenienced, not wanting to change, not wanting to have to get involved. It manifests itself a thousand ways, but once you recognize it, you spot it everywhere.

It’s there in some of our oldest stories. Written in 430 BC, Euripides’ The Children of Hercules is about the plight of the refugee, and how a society is judged by how it treats the weak and vulnerable. The young children of Hercules are driven to the Temple of Apollo in Marathon by a bounty hunter from an angry king, who demands they be handed over to be punished. “They are suppliants and strangers,” the Athenians reply, “Who look to our city for help. / To reject them is to defy the gods.” But the king, obsessed with his vendetta—his goons following his orders—will risk war rather than let these vulnerable people have some measure of peace or safety.

This energy was the motive force behind s the great cruelties of history and the great backlashes too: the Inquisition, the Holocaust, the Confederacy, the exploitation of colonialism, the thwarting of Reconstruction, collaboration in Vichy France, the excesses of the Red Scare and McCarthyism, Apartheid in South Africa, the Rwandan Genocide. And it’s there in modern moments too, big and small, mundane and outrageous: the NIMBY neighbor at a city council meeting to block desperately needed housing, the bullying of librarians, the shrug at another mass shooting, the mob on Twitter gleefully destroying someone, backlash against immigrants (especially when they look different than you), now the backlash vaccines and wind energy, the endless debates (and excuses) while Gaza descends into humanitarian catastrophe.

Gandhi was once asked what worried him most. His reply? “Hardness of heart of the educated.”

When I look around right now, I think of this hardness of heart as one of the big problems of our time. And the way, in the face of it, good people can become utterly exhausted and detached, worn down by years of resisting this energy.

In my book Right Thing, Right Now, I write about Raphael Lemkin, who spent the first half of the twentieth century trying to wake the world up to the atrocities in Armenia and then in Europe.

No one listened. Even as his own family was being murdered in Poland.

So he backed up and decided to start very small. Part of the problem was that new technology had made violence possible on a scale beyond words. “As his armies advance,” Churchill said of Hitler in 1941, “whole districts are exterminated. We are in the presence of a crime without a name.”

Churchill almost always had the right words. Here, he did not.

That’s what Lemkin solved first.

Because the crime had no name, people excused it, denied it, or looked away. In 1943, Lemkin coined the word “genocide” to describe the deliberate destruction of a people. Added to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary in 1950, the word changed the moral arc of the universe.

There it was. It could not be denied.

Lemkin then fought to codify the word into law. At Nuremberg, he all but slept in the hallways as he lobbied for a UN declaration. He hounded reporters, mailed research to politicians, buttonholed diplomats, wrote op-eds. It was good trouble for a good cause. After four years of relentless work, in 1948 the UN passed a unanimous treaty banning genocide—the nameless crime that had claimed Lemkin’s mother. All he could do was weep.

But the fight was only beginning.

The United States refused to ratify the treaty for decades. In 1967, Senator William Proxmire picked up the baton. “The Senate’s failure to act has become a national shame,” he declared. “From now on I intend to speak day after day in this body to remind the Senate of our failure to act and the necessity for prompt action.”

This was not empty virtue signaling. Genocide was happening at that very moment in Nigeria. Soon it would be Bangladesh. Then Burundi. Then Cambodia. And on and on.

Proxmire’s first speech wasn’t successful. Neither was his tenth. Or his hundredth. But he refused to give in to indifference. Across two decades he gave more than three thousand speeches, patiently making trades and deals, steadily winning over the sixty-seven senators he needed.

Finally, in October 1988—twenty years after he began, forty years after Lemkin—Proxmire gave his last speech on the subject, his 3,211th. This time, he could announce victory. The treaty had passed. The world had, at last, a tool to fight humanity’s most nameless crime.

Of course, it would be wonderful if the world were naturally just, if people were automatically good. But they aren’t. It would be wonderful if this was the end of genocide, but obviously, it is isn’t. Terrible war crimes are being committed right now, not just in the Middle East but also in Ukraine and in Sudan. One of the most heartbreaking truths of life is that people not only fail to do the right thing, they often persist in error or evil even after every argument has been made, every procedure followed.

They dig in. They don’t let go.

That was the Southern strategy during segregation—make it so difficult, so painful, so nasty that the North would eventually give up, as it had after Reconstruction.

Which is why the civil rights movement was more than marches. It was endless court cases that took years to be heard, years to win, and were often ignored by Southern officials. When James Meredith sought to integrate the University of Mississippi, Justice Department lawyer John Doar filed hundreds of motions, sat before judge after judge, appealed and appealed again.

“You’ve just got to keep going back,” Doar said. It didn’t matter if an injunction went against them, if governors defied rulings, if mobs surrounded them, if no one cooperated. There was always another motion, another venue, another appeal.

The main thing was that the good guys didn’t quit. They refused to be discouraged. They believed they could—and would—prevail. They stayed with it. They just kept going back, until finally, eventually, they made the tiniest bits of progress.

And the thing about this dark energy is that once it is beaten down somewhere, it finds a new place to pop up. It’s like water: it just pools and then seeks a new outlet. After the famous Brown decision, the Southern energy went into founding Christian “segregation academies” or private white-only schools—effectively creating the Religious Right. Although many modern political issues are complex, when you zoom out, you often see how simple they are: This is somewhere that that energy has found an opportunity to go.

This is an exercise I often do. I mentally put all the specifics aside and I think: What would the people who shouted slurs at Ruby Bridges (or Ernest Green, who I’ve interviewed) as she walked into school for the first time feel about this issue? Or, what about the oligarchs who controlled the levers of power until the Civil War, then fought social reformers during the Gilded Age and then resisted the social safety net during the Great Depression and then fought tooth and nail for isolationism in the run up to WWII (and after too, which is why many senators refused to sign the UN Genocide treaty), what stance would they be drawn to here? I try to think about where the darkness would go—or how it would be rationalized—and I try to go the other way.

In his private writings, we see Marcus Aurelius doing something similar, constantly reminding himself during his own dark and ugly times: Don’t become implicated in the ugliness. Don’t let it infect you. Don’t become cynical or bitter. “Take care,” he writes in Book 7 of Meditations, “that you don’t treat inhumanity as it treats human beings.” Or to put it a more colloquial and modern way: Don’t let the sonsofbitches turn you into a sonuvabitch. Don’t let bad times make you a bad person.

I’m reminded of Montaigne, who, as we have talked about before, faced what might have been even darker times than our own: mass executions, religious wars, persecution, demagogues, bandits, riots, conflict, thousands of people burned at the stake for mostly imagined crimes. He was aghast at the way people treated each other, especially people they disagreed with or didn’t understand. Yet for all the cruelty around him, Montaigne would not be sucked in. As Stefan Zweig would write in the biography I turn to whenever the world seems dark, Montaigne remained human in an inhuman time. He would not get sucked into the dark energy. He would not let inhumanity drive him away from humanity. He would not let the sonsofbitches turn him into a sonuvabitch.

“No one can stop you from that,” Marcus writes. Because, he added. No one can make you do that. It’s a choice. There’s a fountain of goodness there inside us, inside the world. It is up to each of us to make sure that fountain keeps bubbling up. No matter how much shit and evil people try to dump on it.

Don’t let the darkness make you dark.

Don’t let inhumanity deprive you of your humanity.

Don’t equivocate. Call a spade a spade. Condemn evil, cruelty, and injustice.

And keep going back to that fountain of goodness within. As long as you keep going back, “and as long as you keep digging,” Marcus wrote, “it will keep bubbling up.”

No one can stop you from that.

September 3, 2025

The World Lost a Great Man (and my friend) But His Legacy Lives On…

When he was born, he was legally considered less than fully human.

Born in segregated Washington in 1937, George Raveling and his family were second-class citizens, denied basic rights and dignities.

And then it got worse from there. When he was nine, his father died at the age of forty-nine. His mother was committed to an asylum when he was thirteen. Effectively orphaned, this could have been another sad story from a long time ago. Instead, the life of George Raveling became something beautiful, inspiring, and almost unbelievably modern—a classic American story, equal parts Alexander Hamilton and Forrest Gump.

It started with a man named Father Jerome Nadine, a Catholic priest in Brooklyn, who loved basketball (one of his other parishioners was the Wilkens family, whose son Lenny would go on to be an NBA Champion and one of the winningest coaches of all time). He got George a spot at St. Michael’s, a boarding school in Pennsylvania for boys from broken homes, and asked the basketball coach if he could make a spot for the tall young man. Soon enough, the head coach from Saint Joseph’s College, Jack Ramsay, came to his games and told George he would be offering him a college scholarship.

George loved to tell the story of what happened when he went to his grandmother, Dear, to tell her the good news. “I thought I raised you better than that,” Dear said when George told her a college was going to pay for his education to play on their basketball team. “What do you mean?” George said. “I think you’ve done a great job.” “Well, I’m disappointed in myself,” Dear replied, “because I can’t believe that you’re naive enough to think that some white people are gonna pay for you to go to college just so you can play basketball. It makes no sense. They’re tricking you.”

At Villanova, where he did end up with a scholarship (and later a degree in Economics), George led the country in rebounds, only the second black player in the school’s history. In the days before televised basketball, it was often a shock when this integrated team showed up to play southern schools. In 1959, they drove down to Morgantown to play West Virginia. Assigned to guard Jerry West—the future NBA logo—George chased West on a fast break late in the game. When West went up for a layup, George jumped in an attempt to block the shot, colliding with West in the air and sending both of them crashing into the stands. “As we lay there tangled together,” George wrote, “the field house fell silent. I could feel the eyes of the crowd on us, could sense the anger and hostility crackling in the air. In that moment, I feared for my life. But then, something extraordinary happened.” West—“the golden boy of West Virginia, the pride of Morgantown”—got up and then reached out his hand to George. As West pulled George to his feet, the all-white silent crowd erupted into applause. After the game, West ran over as George walked off the court and grabbed him by the arm. “Good game,” West said as he shook George’s hand and looked him in the eyes. “It was a pleasure playing against you.”

After college, he spent time as a traveling assistant and bagman for Wilt Chamberlain, who was getting tons of requests to make appearances at summer camps around the east coast. “I’ll hire you to be my chauffeur,” Wilt told George one day. For a hundred dollars a day, George jumped at the chance to drive Wilt’s purple Bentley convertible from camp to camp, talking basketball and life.

Just these few anecdotes alone would have made George Raveling a living legend. But his rendezvous with history didn’t happen until August 28, 1963. Sent by the father of a friend, 6-foot-four George was recruited to work security for the March on Washington. Standing on the podium a few feet from Dr. King on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, George was one of the first people to greet him as he finished the “I Have a Dream” speech that would change the course of American politics. Accepting the congratulations, King handed George the only existing notes/text (which he had largely ignored in favor of improvisation) of one of the most famous speeches of all time. George tucked it into a book at home—a personalized copy of Truman’s autobiography, which the former president had given him his senior year at Villanova when George played in the East-West All-Star game in Kansas City. There it would sit, safely preserved, for the next few decades until journalists got around to figuring out what had happened to it.

It is a shame that George Raveling’s coaching career is not more well known. He was a great and pioneering one. While an assistant at Villanova, he started recruiting players from the South who, up to that point, were only looked at by historically Black colleges and universities. Players like Johnny Jones and Howard Porter became part of what one sportswriter dubbed “the Underground Railroad,” George’s trailblazing pipeline bringing Southern talent to a predominantly white Northern school. He would later become the first African American basketball coach in what’s now the Pac-12 and went on to go 335-293 over his career, leading programs at Washington State, the University of Iowa, and USC. He won 2 Olympic medals, a gold in 1984 and a bronze in 1988. He coached against John Wooden, Dean Smith, and Bob Knight. He earned his Hall of Fame induction as an X and O’s guy, a recruiter and as a leader of young men to victory.

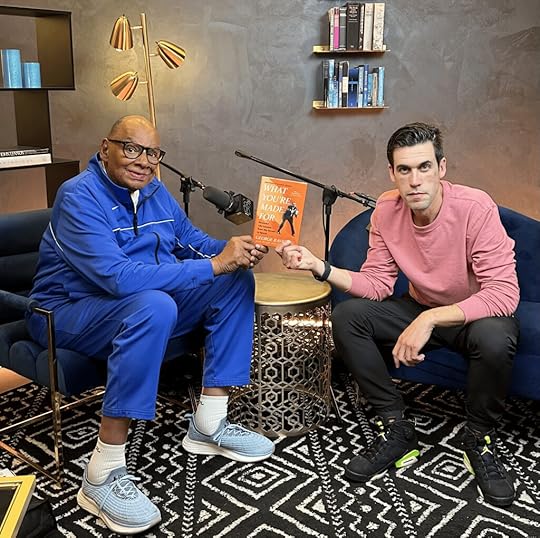

Of course, we remember him most for his contributions to the game slightly off the court. It was George Raveling who, as an assistant coach for the 1984 Olympic Team, steered Michael Jordan to Nike and changed the economics of sports and entertainment and fashion. You might not know this from the movie Air, which is largely about Sonny Vaccaro, but Michael Jordan knows the truth and has always and repeatedly credited Raveling. Ben Affleck tells the story of meeting with Jordan to get his blessing to make Air. Jordan gave the go-ahead, but with two conditions: Viola Davis had to play his mom, and George Raveling had to be in the story. He released a statement this morning after the news of George’s death, thanking him for his decades of friendship and mentorship. “I signed with Nike because of George,” he said of his most famous and consequential business decision, “and without him, there would be no Air Jordan.”

And then there is what George did while he was at Nike. After a twenty-two-year career, he retired from coaching in 1994, and at the age of sixty-two joined Nike as their director of international basketball. He traveled around the world to countries where basketball was a little-known sport, where resources were limited, good coaching was scarce, and talented players had no exposure to college or professional scouts. In an attempt to fix that, in 1995, George developed the Nike Hoop Summit, an annual all-star game featuring the top young players from around the world. Since the inaugural event, to this day, the Hoop Summit has launched the careers of countless international stars: Dirk Nowitzki (Germany), Tony Parker (France), Enes Kanter (Turkey), Luol Deng (South Sudan), Serge Ibaka (Republic of the Congo), Nikola Jokić (Serbia), and most recently, Victor Wembanyama (France).

I, myself, met George in 2015 at a University of Texas Basketball practice. I thought I was just shaking hands with a friendly older gentleman. I did not know that day that I was shaking hands with history–a hand that had in turn shaken hands with Presidents Truman and Ford and Carter and Reagan and Clinton and had held the “Dream” speech.