Ryan Holiday's Blog, page 2

July 30, 2025

Everything (And I Really Mean Everything) Is A Chance To Do This

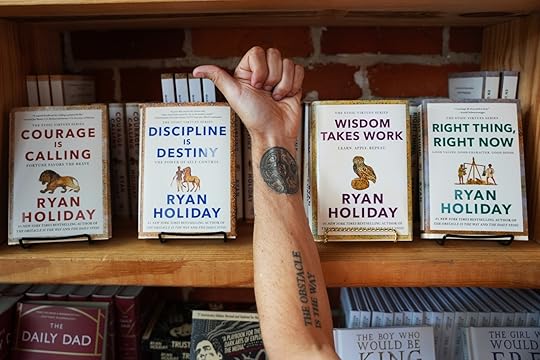

Get the limited edition collector’s set of my series on The Stoic Virtues.

I think people get it wrong.

I know I did.

When the Stoics say that the obstacle is the way, that there’s an opportunity in every obstacle, most of us take that to mean there’s some way to turn adversity into advantage.

We think of entrepreneurs pivoting during a downturn and building a billion-dollar business. We think of an investor buying back their own stock or taking advantage of being underestimated by their competitors. We think of a general using the bad weather as cover. We think of an athlete coming back stronger after an injury. We think of some rejected artist going independent and building their own label.

That’s how I was thinking about obstacles and opportunities when I wrote The Obstacle is the Way in my twenties. The simplest idea at the center of the book is that there are hidden advantages in every problem, that businesses and teams and people can take seemingly impossible situations and triumph over them. “Hard times can be softened,” Seneca writes in one of his essays, “tight squeezes widened, and heavy loads made lighter for those who can apply the right pressure.”

But what I’ve come to understand in the intervening years is that the Stoics were getting at something more profound than the fact that every downside can be flipped into some kind of advantage or transformed into a success story.

They had to.

Because it would be insane (and insulting) to say that terminal cancer was an advantage. Was there a way for Marcus Aurelius to spring forward after he buried another one of his children? Seneca can say that hard times can be softened, but then again, he didn’t have to live like Epictetus, not just through slavery but with a crippling disability from the torture he underwent at the hands of his master.

What I’ve come to understand is that the “opportunity” the Stoics saw inside adversity, big and small, was the opportunity to practice virtue. That is, it was a chance for them to rise to meet an occasion, to do the right thing, to be magnificent or magnanimous, even when they were heartbroken, even when they were being kicked around by life, even when they were dying.

Ok, so what is virtue?

In the ancient world, virtue consisted of four key components:

Courage—bravery, fortitude, honor, sacrifice…

Temperance—discipline, self-control, moderation, composure, balance…

Justice—fairness, service, honesty, fellowship, goodness, kindness…

Wisdom—knowledge, education, truth, self-reflection, peace…

Marcus Aurelius called them the “touchstones of goodness”—guiding principles for how to act, who to be, and how to respond in any situation. And there really is no situation that we can’t use as a way to practice these virtues. Even the hardest, most tragic, most heartbreaking moments of life—a terminal diagnosis, a crippling injury, losing your livelihood, burying a loved one—can be transformed by endurance, by selflessness, by courage, by kindness, by decency.

When I interviewed Francis Ford Coppola on the Daily Stoic podcast, he shared how he’s been getting through a recent tragedy in his own life—losing his wife of 60 years. “There was a Marcus Aurelius quote that really lifted me,” he told me, “which was that ‘if you lose a loved one, honor her.’ In a sense, try to be more like her, and then she’ll live on in your actions. My wife was very good—if someone was alone or sick or something, she’d call them up and be comforting to them. And I’m not like that, you know? So I started to do that. People that I know—some guys my age who have no grandchildren—I call them up and say, ‘Hey, how are you?’ And they are so pleased and so kind. And that’s how I keep my wife in my life.”

Beautiful. And closer to what I think it really means when we say the obstacle is the way.

I’ve tried to apply this formula practically in my business and creative life, but also in the difficulties I’ve faced in my life. The last decade and a half has been good to me in many ways. It’s also been…a lot. There were natural disasters, floods and fires, a freeze that broke the power grid and most of our pipes. A long drought that devastated our livestock and land. A tragic, years-long pandemic that dashed countless plans (nearly killing the independent bookstore we opened in the teeth of it). Disputes with business partners. An employee caught embezzling. Funerals and late-night phone calls with news you never want to get. The company where I made my bones went bankrupt, taking with it not just much of my résumé but what was supposed to be several years’ salary in stock options. There was a falling out with family. Hundreds of thousands of miles on the road. There was getting skunked on the bestseller lists, creative differences, daily battles with procrastination.

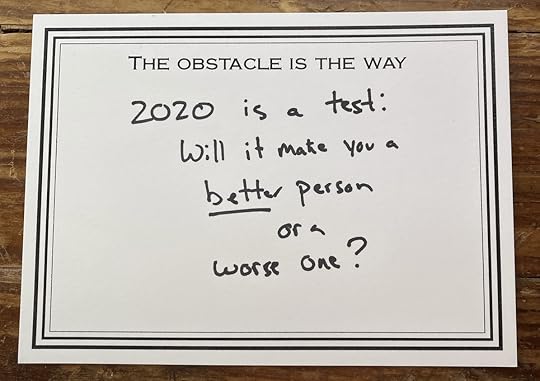

I remember in the early days of the pandemic, I wrote a note to myself along these very lines:

In spending much of that time working on the Stoic Virtues Series—four books, each on one of the cardinal virtues—I have come to more fully understand what the Stoics were getting at: LIFE IS ALWAYS DEMANDING ONE OF THESE VIRTUES FROM US. Always demanding us to be a good person despite the bad things that have happened. To do good in the world despite the bad that has befallen you. And in good times—in the face of the temptations, distractions, responsibility and obligations and obstacles that come with success and abundance—to be humble, to be disciplined, to be decent, to be generous, to hold true to your values.

When I look at the world right now, as frustrated and alarmed as I am by it, what I try to remind myself is that it’s moments like this that demand virtue from us. We don’t control so much of what’s happening. We wouldn’t choose so much of this. But here it is. What are we going to do about it? Who are we going to be inside it?

The fourth and final book in the virtue series, Wisdom Takes Work, is set to come out this fall (but is officially available now for preorder at dailystoic.com/wisdom, where we’re doing a run of preorder bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, early access to the introduction, bonus chapters, and even an invite to a philosophy dinner at my bookstore, The Painted Porch—check out all the bonuses here).

When Edward Gibbon finished The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, he noted his sadness at taking “everlasting leave of an old and agreeable companion.” I don’t feel exactly that way—virtue isn’t something you ever finish or take leave of—but there is something bittersweet about drawing these books to a close.

I’m better for having written them—not just as a writer, but as a person. Of course, I can already see all the things I’d do differently if I were starting over, all I’ve learned since publishing the first book in 2021. But, that’s kind of the point. To get better as you go. To learn from your time here. To put your past self to shame.

One thing I’ve noticed? I am calmer. I am quieter. I argue less. I get upset less. I admit I am wrong more often. There’s still a long way to go, but I’m proud of the progress I’ve made.

That’s how Aristotle described virtue—as a kind of craft, something one gets better at just as one would get better at any skill or profession. “We become builders by building and we become harpists by playing the harp,” he writes. “Similarly, then, we become just by doing just actions, temperate by doing temperate actions, brave by doing brave actions.”

Virtue is not something you demand of others. It’s not a standard you pass laws about or police. It’s not something we flippantly say or conflate with “success.”

It’s something you demand of yourself. It’s something you do. It’s something you use day to day, moment to moment. It’s something that steers the choices you make and the actions you take. It’s something you choose.

And every situation—big and small, positive or negative—is an opportunity to make a virtuous choice.

Will you be brave or afraid? Selfish or selfless? Strong or weak? Wise or stupid? Will you cultivate a good habit or a bad one? Courage or cowardice? The bliss of ignorance or the challenge of a new idea? Stay the same…or grow? The easy way or the right way?

Is it easy to make these choices? Of course not. That’s why I put it in the title of the new book—it takes work.

I finished the Stoic Virtues Series, but I remain committed to the work.

I hope you do the same.

With the upcoming release of Wisdom Takes Work, the team and I at Daily Stoic wanted to do something special, something we’ve never done before—a limited edition collector’s set of all four books in the Stoic Virtues Series. Each set is signed and numbered with a unique title page identifying them as part of the only printing of this series. I’m also throwing in one of the notecards I used to help me write the series (learn more about my notecard system here). There’s a limited run of these, so check them out here today.

July 17, 2025

37 Lessons From The Birthplace Of Stoicism

From my run on a trail overlooking Mt. Olympus.

From my run on a trail overlooking Mt. Olympus.On a fateful day in the fourth century BC, the Phoenician merchant Zeno lost everything.

While traveling through the Mediterranean Sea with a cargo full of Tyrian purple dye, his ship wrecked upon the rocks, his cargo lost to the sea. He washed up in Athens.

We’re not sure what caused the wreck, but it devastated him financially, physically, emotionally. It could have been the end of his story—the loss could have driven him to drink or suicide, or a quiet ordinary life in the service of others. Instead, it set in motion the creation of Stoicism, one of the greatest intellectual and spiritual movements in history.

“I made a prosperous voyage,” Zeno later joked, “when I suffered a shipwreck.”

Indeed, we were all richer for it.

Why am I telling you this? Because I’m in Greece right now with my family for our summer vacation–the birthplace of Stoicism. We didn’t just fly into Athens and take a couple of tours, but decided instead to really cover quite a bit of geography on the trip (2,500km or so by car and boat between Athens, Olympia, Ithaca, Delphi, Patras, Thermopylae, Mt. Olympus, Marathon, Cape Sounio, among others) and I’ve had the wonderful experience of bringing to life Stoic lessons and stories that I’ve been studying, reading, and talking about for decades.

And as I’m stomping around in the places where it all began, I thought I’d riff on some of my favorite lessons and ideas from Stoicism. I was first introduced to this philosophy two decades ago and have since written thirteen books, sent out well over 3,000 Daily Stoic emails, and hosted 500+ Daily Stoic Podcast interviews. I’ve picked up some pretty good lessons along the way. Here are some of my favorites:

[*] “The chief task in life,” Epictetus said, “is simply this: to identify and separate matters so that I can say clearly to myself which are externals not under my control, and which have to do with the choices I actually control. Where then do I look for good and evil? Not to uncontrollable externals, but within myself to the choices that are my own . . .” That’s the fundamental premise of Stoicism, also known as the “dichotomy of control”. If we can focus on making clear what parts of our day are within our control and what parts are not, we will not only be happier, we will have a distinct advantage over other people who fail to do so.

[*] As I wound up the Sacred Way to the Temple of Apollo last week, it occurred to me that I was literally following in Zeno’s footsteps, the footsteps he would have taken when he visited the Oracle at Delphi and received a life-changing prophecy: “To live the best life,” the Oracle told Zeno, “you should have conversations with the dead.” What does that mean? Zeno wasn’t sure…until he made a realization that you may have made yourself: Reading is the way to communicate with the dead. Reading doesn’t just change us, it opens us up to live multiple lives, to absorb the experiences of generations of people. It allows us to gain cost-free knowledge that someone else gained through pain and suffering.

[*] It’s fascinating to me that Epictetus–a Greek slave–ends up intersecting (and interacting) with FOUR different Roman emperors: Nero, Domitian, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius. And do you know who was most influenced by Epictetus? Whose life was most radically changed by his lectures? Marcus Aurelius. So it’s unfortunate Epictetus isn’t more widely known and read—because when he is, he changes lives. And that’s why we’re dedicating a whole month to Epictetus over at The Daily Stoic. In an effort to make his work more accessible, we created a brand new guide called How To Read Epictetus. It’s part book club, part deep dive into the life, lessons, and legacy of this incredible teacher. So if you want to understand why Epictetus is your favorite philosopher’s favorite philosopher (as he was for Marcus Aurelius), then join me and thousands of other Stoics over at dailystoic.com/epictetuscourse today.

[*] Epictetus reminds us that “it’s impossible to learn that which you think you already know.” To the Stoics, particularly Zeno, conceit was the primary impediment to wisdom. Because when you’ve always got answers, opinions and ready-made solutions, what you’re not doing is learning.

[*] A wise man, Chrysippus said, can make use of whatever comes his way but is in want of nothing. “On the other hand,” he said, “nothing is needed by the fool for he does not understand how to use anything but he is in want of everything.” There is perhaps no better definition of a Stoic: to have but not want, to enjoy without needing.

[*] It’s strange how often Stoicism is associated today with “having no emotions,” because all the Stoics are explicit in how natural it is to have emotions, in deed and word. A Stoic feels. We only have a dozen or so surviving anecdotes about Marcus Aurelius, and THREE of them have him crying. He cried when his favorite tutor passed away, he cried in court over deaths from the Antonine Plague. Stoicism isn’t a tool to help you stuff down your emotions, it’s a tool to help you better process and deal with them.

[*] People will piss you off in this life. That’s a given. But before you get upset, stop yourself. “Until you know their reasons,” Epictetus once said, “how do you know whether they have acted wrongly?” That moron who cut you off on the highway, what if he’s speeding to the hospital? The person who spoke rudely might have a broken heart. The Stoics remind us to be empathetic. Almost no one does wrong on purpose, Socrates said. Maybe they just don’t know any better.

[*] In my favorite novel, The Moviegoer by Walker Percy (who loved Stoicism and wrote about it often), the wisest character in the book, Aunt Emily, says there’s “one thing I believe and I believe it with every fiber of my being. A man must live by his lights and do what little he can and do it as best he can. In this world goodness is destined to be defeated. But a man must go down fighting. That is victory. To do anything less is to be less than a man.” That captures Stoicism to me. The Stoics didn’t always win, but they always showed themselves as worthy of winning. Cato’s fight against Caesar was a losing battle. He could have folded, he could have fled, but he didn’t. He gave everything to protect the ideals Rome was founded on, a cause he believed was just. He didn’t succeed, but he did the next best thing: He gave his best.

[*] The ancients didn’t have the advantage of looking down from an airplane to see the world from a 30,000-foot view. They never saw their home in a satellite image. Still, at least twice in Meditations, Marcus speaks of taking “Plato’s view.” “To see them from above,” he writes, “the thousands of animal herds, the rituals, the voyages on calm or stormy seas, the different ways we come into the world, share it with one another and leave it.” For him the exercise was theoretical—the tallest mountain in Italy is about 15,000 feet and as far as we know, he never climbed it. But what he got from this exercise was humility, a better understanding of how small and interconnected we are.

[*] In one of his most famous letters to Lucilius, Seneca gives a pretty simple prescription for the good life. “Each day,” he wrote, “acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes.” One gain per day. That’s it. One quote, one prescription, one story. “Well-being,” Zeno said, “is attained by little and little, and nevertheless is no little thing itself.”

[*] “He who is everywhere,” Seneca says, “is nowhere.” If you want to be great at whatever it is you’re doing, you have to make some choices about what you say yes to and what you say no to. “Most of what we say and do is not essential,” Marcus Aurelius reminds us. “If you can eliminate it, you’ll have more time, and more tranquility. Ask yourself at every moment, ‘Is this necessary?’”

[*] There is a wonderful quote from Epictetus that I think of every time I see someone get terribly offended or outraged about something. I try to think about it when I get upset myself. “If someone succeeds in provoking you,” he said, “realize that your mind is complicit in the provocation.” Whatever the other person did is on them. Whatever your reaction is to their remark or action, that’s on you. Don’t let them bait you or make you upset. Focus on managing your own behavior. Let them poke and provoke as much as they like. Don’t be complicit in the offense.

[*] Courage. Justice. Temperance. Wisdom. They are the most essential virtues in Stoicism, what Marcus called the “touchstones of goodness.” “If, at some point in your life,” Marcus Aurelius wrote, “you should come across anything better than justice, truth, self-control, courage — it must be an extraordinary thing indeed.”

[*] “If your choices are beautiful,” Epictetus said, “so too will you be.” It’s simple and it’s true: you are what your choices make you. Nothing more and nothing less.

[*] It’s a strange paradox. The people who are most successful in life, who accomplish the most, who dominate their professions—they don’t care that much about winning. They don’t care about outcomes. As Marcus Aurelius said, it’s insane to tie your well-being to things outside of your control. Success, mastery, sanity, Marcus writes, comes from tying your wellbeing, “to your own actions.”

[*] It’s possible, Marcus Aurelius said, to not have an opinion. Do you need to have an opinion about the scandal of the moment—is it changing anything? Do you need to have an opinion about the way your kid does their hair? So what if that person is a vegetarian? “These things are not asking to be judged by you,” Marcus writes. “Leave them alone.” Especially because these opinions often make us miserable! “It’s not things that upset us,” Epictetus says, “it’s our opinions about things.” The fewer opinions you have, especially about other people and things outside your control, the happier you will be. Of course, this is not to say that we shouldn’t have any opinions at all, but that we should save our judgments for what matters—right and wrong, justice and injustice, what is moral and what is not.

[*] The occupations of the Stoics could not be more different. Seneca was a playwright, a wealthy landowner, and a political advisor. Epictetus was a former slave who became a philosophy teacher. Marcus Aurelius would have loved to be a philosopher, but instead found himself wearing the purple cloak of the emperor. Zeno was a prosperous merchant. Catowas a Senator. Cleanthes was a water carrier. Once asked by a king why he still drew water, Cleanthes replied, “Is drawing water all I do? What? Do I not dig? What? Do I not water the garden? Or undertake any other labor for the love of philosophy?” What matters to the Stoics is not what job you have but how you do it. Anything you do well is noble, no matter how humble.

[*] The now-famous passage from Marcus Aurelius is that the impediment to action advances action, that what stands in the way becomes the way (which is also the passage that inspired my book The Obstacle is the Way). But do you know what he was talking about specifically? He was talking about difficult people! He was saying that frustrating, infuriating, thoughtless people are opportunities to practice excellence and virtue—be it forgiveness, patience, self-control, or cheerfulness. But it’s not just with difficult people. That’s what I’ve come to see as the essence of Stoicism: every situation is a chance to practice virtue. So when I find myself in situations big and small, positive or negative, I try to see each of them as an opportunity for me to be the best I’m capable of being in that moment.

[*] Every event has two handles, Epictetus said: “one by which it can be carried, and one by which it can’t. If your brother does you wrong, don’t grab it by his wronging, because this is the handle incapable of lifting it. Instead, use the other—that he is your brother, that you were raised together, and then you will have hold of the handle that carries.” This applies to everything. When bad news comes, do I grab the handle of despair or the handle of action? When I’m slighted, do I grab the handle of grievance or the handle of grace? When things feel uncertain, do I grab the handle of fear or the handle of preparation? I don’t get to choose what happens. But I do get to choose how I respond. And if I want to carry the weight of whatever comes next, I have to grab the handle that’s strong enough to hold.

[*] “The things you think about determine the quality of your mind,” Marcus writes in Meditations. “Your soul takes the color of your thoughts.” If you see the world as a negative, horrible place, you’re right. If you look for shittiness, you will see shittiness. If you believe that you were screwed, you’re right. But if you look for beauty in the mundane, you’ll see it. If you look for evidence of goodness in people, you’ll find it. If you decide to see the agency and power you do have over your life, well, you’ll find you have quite a bit.

[*] Over the years, the Stoics have completely reoriented my definition of wealth. Of course, not having what you need to survive is insufficient. But what about people who have a lot…but are insatiable? Who are plagued by envy and comparison? Both Marcus Aurelius and Seneca talk about rich people who are not content with what they have and are thus quite poor. But feeling like you have ‘enough’–that’s rich no matter what your income is.

[*] This was a breakthrough I had during the pandemic. Suddenly, I had a lot less to worry about. I wasn’t doing the things that, in the past, I told myself were the causes of my anxiety. I wasn’t hopping on a plane. I wasn’t battling traffic to get somewhere on time. I wasn’t preparing for this talk or that one. So you’d think that my anxiety would have gone way down. But it didn’t. And what I realized is that anxiety has nothing to do with any of these things. The airport isn’t the one to blame. I am! Marcus Aurelius talks about this in Meditations. “Today I escaped from anxiety,” he says. “Or no, I discarded it, because it was within me, in my own perceptions—not outside.” It’s a little frustrating, but it’s also freeing. Because it means you can stop it! You can choose to discard it.

[*] One of the most relatable moments in Meditations is the argument Marcus Aurelius has with himself in the opening of book 5. It’s clearly an argument he’s had with himself many times, on many mornings—as have many of us: He knows he has to get out of bed, but so desperately wants to remain under the warm covers. It’s relatable…but it’s also impressive. Marcus didn’t actually have to get out of bed. He didn’t really have to do anything. The emperor had all sorts of prerogatives, and here Marcus was insisting that he rise early and get to work. Why? Because Marcus knew that winning the morning was key to winning the day and winning at life. By pushing himself to do something uncomfortable and tough, by insisting on doing what he said he knew he was born to do and what he loved to do, Marcus was beginning a process that would lead to a successful day.

[*] The Stoics kept themselves in fighting shape, they liked to say, not for appearance’s sake, but because they understood life itself was a kind of battle. They did hard things. They sought out opportunities to push their physical limitations. Socrates was admired for his ability to endure cold weather. Marcus Aurelius was a wrestler. Cleanthes was a boxer. Chryssipus was a runner. This wasn’t separate from their philosophy practice, it was their philosophy practice. “We treat the body rigorously,” Seneca said, “so that it will not be disobedient to the mind.”

[*] This was Marcus’ simple recipe for productivity and for happiness. “If you seek tranquility,” he said, “do less.” And then he clarifies. Not nothing. Less. Do only what’s essential. “Which brings a double satisfaction: to do less, better.”

[*] Just because someone spends a lot of time reading, Epictetus said, doesn’t mean they’re smart. Great readers don’t just think about quantity, they think about quality. They read books that challenge their thinking. They read books that help them improve as human beings, not just as professionals. They, as Epictetus said, make sure that their “efforts aim at improving the mind.” Because then and only then would he call you “hard-working.” Then and only then would he give you the title “reader.”

[*] The Stoics come down pretty hard on procrastinating. It’s “the biggest waste of life,” Seneca wrote. “It snatches away each day and denies us the present by promising the future.” To procrastinate is to be entitled. It is arrogant. It assumes there will be a later. Stop putting stuff off. Do it now.

[*] Marcus talked about a strange contradiction: we are generally selfish people, yet, more than ourselves, we value other people’s opinions about us. “It never ceases to amaze me,” he wrote, “we all love ourselves more than other people, but care more about their opinion than our own.” The fundamental Stoic principle is that we focus only on the things that are within our control. Other people’s opinions are not within our control. Don’t spend any time worrying about what other people think.

[*] The Stoics often quote the poet Heraclitus, who said that character is fate. What he meant was: Character decides everything. It determines who we are/what we do. Develop good character and all will be well. Fail to, and nothing will.

[*] It’s called self-discipline. It’s called self-improvement. Your standards are for you. Marcus said philosophy is about being strict with yourself and forgiving of other people. That’s not only the kind way to be, it’s the only effective way to be.

[*] Marcus reminded himself: “Don’t await the perfection of Plato’s Republic.” Because if you do, that’s all you’ll do…wait. That’s one of the ironies about perfectionism: it rarely begets perfection—only disappointment, frustration, and, of course, procrastination. So instead, Marcus said, “be satisfied with even the smallest progress.” You’re never going to be perfect—there is no such thing. You’re human. Instead, aim for progress, even the smallest amount.

[*] Seneca said we have to “choose someone whose way of life as well as words have won your approval. Be always pointing him out to yourself either as your guardian or as your model.” Choose someone who you want to be like, and then constantly ask yourself: what would they do in this situation? In Seneca’s last moment, when Nero comes to kill him, it’s Cato that he channels. It’s where he gets his strength. Even though Seneca had fallen short of his writings in a lot of ways, in the moment it mattered most, he drew on Cato and became as great as philosophy could have ever hoped for him to be.

[*] Some days, Marcus wrote, the crowd cheers and worships you. Other days, they hate you and hit you. They’ll build you up, and then tear you down. That’s just the way it goes. The key, Marcus said, is to assent to all of it. Accept the good stuff without arrogance, he writes in Meditations. Let the bad stuff go with indifference. Neither success nor failure says anything about you.

[*] Seneca said that the key distinction between the Stoics and the Epicureans is that the Epicureans only got involved in politics and public life if they had to. The Stoic, he says, gets involved unless something prevents you. Sometimes I get pushback from people when I talk about anything political with The Daily Stoic. “Why pick a side?” they ask. “You’re going to piss off your audience.” The reason I pick a side is that you have to pick a side. That’s what the Stoic virtue of justice is about. Stoicism says we have to be active—we have to participate in politics, we have to try to make the world a better place, we have to serve the common good where we can. You can’t run away from these things. It has to be a battle you’re actively engaged in—in the world, in your job, in the community, in your neighborhood, in your country, in the time and place that you live.

[*] The reality is: we will fall short. We all will. The important thing is that we pick ourselves back up when we do. “When jarred, unavoidably, by circumstances,” Marcus Aurelius wrote, “revert at once to yourself, and don’t lose the rhythm more than you can help. You’ll have a better grasp of the harmony if you keep on going back to it.” You’re going to have an impulse to give in, your temper is going to get the best of you. Ambition might lead you astray. But you always have the ability to realize that that is not who you want to be, that is not what you were put here to do, that is not who your philosophy wants you to be.

[*] A Stoic is strong. A Stoic is brave. They carry the load for themselves and others. But they also ask for help. Because sometimes that’s the strongest and bravest thing to do. “Don’t be ashamed to need help,” Marcus Aurelius wrote. “Like a soldier storming a wall, you have a mission to accomplish. And if you’ve been wounded and you need a comrade to pull you up? So what?” If you need a minute, ask. If you need a helping hand, ask. If you need a favor, ask. If you need therapy, go.

[*] I spoke at a biohacking conference a few weeks ago where the stated purpose was all about living well into your hundreds. I teased them a little. Why? I said. So you can spend more time on your phone? So you can accumulate more stuff? So you can check more boxes off your to-do list? Marcus Aurelius would’ve asked, as he did in Meditations,“You’re afraid of death because you won’t be able to do this anymore?” We all think we need to, deserve to, live forever. But death is real. Memento mori. None of us has unlimited time. Which is why we have to get serious now. We have to live and be well now.

July 2, 2025

34 Lessons From Writing Every Day for Two Decades

I remember driving home from my high school graduation, excited. I was excited not because I was done with school but because of what I was about to start. I’d been working with a friend to put up my first website.

I was going to be a writer.

I’m sure whatever I wrote that day was terrible but that’s sort of the point. It was the first of many, many days. Two decades of days, in fact. I have been writing almost every day for twenty years. How many millions of words is that? I don’t know.

The published output is pretty decent: sixteen books under my own name. Another half dozen or so ghostwritten. One of them was optioned to be a movie starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, directed by Gus Van Sant (if it ever happens…) Ten million copies sold. Articles in the New York Times, Forbes, USA Today, and Thought Catalogue.

But mostly, I can feel it. I feel like I am just starting to hit my stride, just starting to get the hang of it. If you told me twenty years ago that that’s how long real confidence would take, I don’t know if I could have handled it. Still, I stayed at it and here we are…and I’ve learned a few things along the way, both about craft and about life (the two are more related than you think).

So that’s what I wanted to share today…

– I am very ambitious as a writer. I no longer have any ambitions as an author. I’m not aiming at lists. I don’t think about deals. I rarely even look at sales numbers. I have stopped tracking how other people’s books are doing. What I’m saying is that I have locked into process and tuned out publishing. The funny thing is that my results have gotten better the more I have flipped this ratio. I have also gotten much more content.

– Related…I once read a letter where Cheryl Strayed kindly pointed out to a young writer the distinction between writing and publishing. Her implication was that we focus too much on the latter and not enough on the former. It’s true for most things. Amateurs focus on outcomes more than process. The more professional you get, the less you care about results. It seems paradoxical but it’s true. You still get results, but that’s because you know that the systems and processes are reliable. You trust them with your life.

– And if you’re doing what you’re doing for external rewards, god help you. A Confederacy of Dunces was rejected by publishers. After the author’s suicide, it won the Pulitzer. People don’t know shit. YOU know. So love it while you’re doing it. Success can only be extra.

– Speaking of which, that distinction between amateur and professional is an essential piece of advice I have gotten, first from Steven Pressfield’s writings and then by getting to know him over the years. There are professional habits and amateur ones. Which are you practicing? Is this a pro or an amateur move? Ask yourself that. Constantly. – Professionals work. Amateurs talk a lot about tools. Software does not make you a better writer. If classics were created with quill and ink, you’ll probably be fine with a Word Document. Or a blank piece of paper. Don’t let technology distract you. Helen Simpson has “Faire et se taire” from Flaubert on a Post-it near her desk, which she translates as “Shut up and get on with it.”

– Don’t get caught up trying to please everyone all the time. No one who has ever created anything has escaped criticism. It’s inevitable that some percentage of people will not like what you do. You’ll drive yourself crazy if you think you’re somehow the exception to this. Just stay true to your work and who you are and don’t be too attached to your reputation.

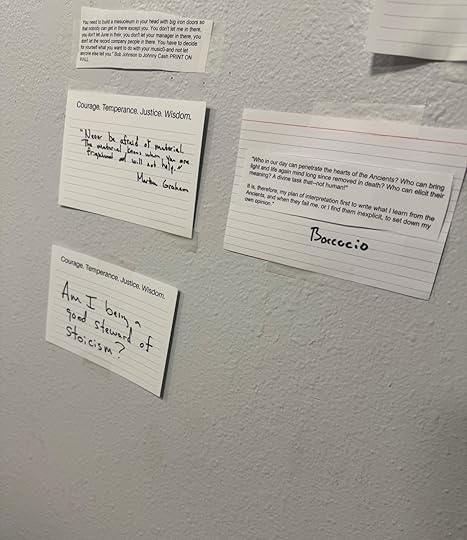

– I’m not sure where I stole the idea from, but I am a big proponent of printing out and putting up good advice and quotes. What goes up on the wall next to where I work can change project to project, but right now, I have a quote from Martha Graham: “Never be afraid of the material. The material knows when you are frightened and will not help.” One from Boccaccio: “Who in our day can penetrate the hearts of the Ancients? Who can bring light and life again minds long since removed in death? Who can elicit their meaning? A divine task that–not human! It is, therefore, my plan of interpretation first to write what I learn from the Ancients, and when they fail me, or I find them inexplicit, to set down my own opinion.” And one from Bob Johnson to Johnny Cash: “You need to build a mausoleum in your head with big iron doors so that nobody can get in there except you. You don’t let me in there, you don’t let June in there, you don’t let your manager in there, you don’t let the record company people in there. You have to decide for yourself what you want to do with your music and not let anyone else tell you.”

– The novelist Philipp Meyer (whose book The Son is an incredible read) told me on the podcast, “You have to be very careful about to what (and to whom) you’re giving the best part of your day.” I fiercely protect my mornings—family first, then writing. My assistant knows not to schedule anything before mid-morning because early calls and meetings don’t just take time—they sap the energy needed for the essential work.

– Writing Trust Me, I’m Lying, I was 90% conscious about what other people might think and 10% following what was in my heart as an artist. The book I am most proud of is my book Conspiracy. The only parts of it I wish I could do differently are the few instances that, in retrospect, I was too conscious of what other people might think (particularly journalists). I’ve flipped the ratio by this point, but I wish I had gotten to that happier place sooner.

– When The Obstacle Is the Way came out, it did okay, but I was already deep into working on what would become Ego Is the Enemy. About a year later, Obstacle really took off—teams like the New England Patriots were reading it, and there was a big article that fueled sales. But by then, I didn’t care as much because I was focused on the next book. I accidentally stumbled into a process that protected me from both disappointment and ego—I was too focused on the next thing to get caught up in good or bad news. Now I always try to start the next project before the last one launches, even arranging my schedule so I’m working the day sales numbers come in, to avoid getting caught up in those ups and downs.

– When I look back on my own writing, the stuff that makes me cringe isn’t necessarily even stuff I was wrong about. What disturbs me is the certainty. I thought I knew, but I didn’t really know. I wasn’t even close to knowing. Ego never ages well, even if it was correct in a narrow instance. My books have gotten longer as I’ve gone on. I don’t think I’m being self-indulgent, I think I am being more fair, more compassionate, more truthful.

– I’ve heard this many times from many different writers over the years (Neil Strauss being one), but as time passes the truth of it becomes more and more clear, and not just in writing: When someone tells you something is wrong, they’re almost always right. When someone tells you how to fix it, they’re almost always wrong.

– Along those lines…I wanted Trust Me, I’m Lying to be titled Confessions of a Media Manipulator. I also should have stuck to my guns about the prologue of Ego is the Enemy (I didn’t want to be in it, they wanted me in it). In creative disputes, the publisher/studio/investors/etc. are not always wrong, but often they are. And even when they’re not, you have to remember that whatever the decision, you have to live with it in a way they do not. I’ve regretted every time I did not go with what was in my heart as an artist.

– Writing is a byproduct of hours and hours of reading, researching, thinking and making my notecards. When a day’s writing goes well, it’s got little to do with that day at all. It’s actually a lagging indicator of hours and hours spent researching and thinking. Every passage and page has a prologue titled Preparation.

– As I was writing The Daily Stoic, I got into it and decided I would just keep going. That’s what started The Daily Stoic email. I’ve written and sent out a meditation on Stoicism every day since—I’d estimate that’s 1,500,000 words? It might seem like a lot of work to write and put out an email every day for almost nine years…and it is! But it’s also one of my favorite things to do, and it has made me so much better. Committing to this has been a forcing function for my productivity. We all need reps. If I only published books, I wouldn’t get nearly as many reps as I have gotten from publishing these daily emails–each one making me a little better at my craft.

– When Winston Churchill was driven from power, he could have wallowed or retired. Instead, he became a one-man media company—publishing 11 books, 400 articles, and giving 350 speeches between 1931 and 1939. He became more famous in the U.S. than in Britain, delivering his message without intermediation. They tried to cancel him, but it didn’t work. That’s what I’ve built with The Daily Stoic. It’s not just an email list but also a YouTube Channel with 2M subscribers, an Instagram account with 3.4M followers, a Twitter account with 600K followers, a TikTok page with 800K followers, and a Facebook page with 1M followers. It’s Stoicism directly to the people.

– I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought of a great line or solved an intractable writing problem while running or swimming. Exercise is also an easy win every day. Writing can go poorly, but going on a run always goes well.

– James Altucher has a great rule that I have stolen: write what you’re afraid to say. If your stuff isn’t scaring you, you’re not pushing yourself enough.

– The guy that spoke before Lincoln at Gettysburg went on for about two hours—his speech was 13,607 words long. Lincoln got up and spoke just 271 words. Think about how short Meditations is. Think about Seneca’s best quotes, how boiled-down and blunt they are. Real insight does not take many words to express. (More on this idea in Gary Willis’ incredible book Lincoln at Gettysburg).

– Near the end of his presidency, Eisenhower asked speechwriter James C. Humes to draft an address. After submitting a draft, Humes was called to Eisenhower’s office to discuss. “What’s the QED of this speech?” Eisenhower asked. Humes was confused. “QED,” he said, “what’s that?” “Quod Erat Demonstrandum,” Eisenhower barked. “Don’t you remember your geometry? What’s the bottom line? In one sentence!” Eisenhower was a brilliant man, but a simple and straightforward one after years in the Army. He had no patience for rambling. This is a good lesson for anyone and everyone when it comes to communication. Don’t dress things up more than they need to be. Don’t hedge. Don’t distract. Speak plainly. Make your point.

– Precisely zero of my sixteen books were immediately accepted by my publisher—and they were right to kick them back at me. In being forced to go back to the manuscript, I got the books to where they needed to be. Hemingway once said that “the first draft of anything is shit,” and he’s right (I actually have that on my wall as a reminder).

– Don’t talk about projects until you’re finished. Save that carrot for the end. Talking and doing fight for the same resources.

– My editor Niki Papadopoulos once told me, “It’s not what a book is. It’s what a book does.” This is why musicians follow the “car test” (how does the song sound in a car driving down the highway). It’s not about whether you like it…but about what it does for the people buying it.

– Vivian Gornick said, “What happened to the writer is not what matters; what matters is the large sense that the writer is able to make of what happened.” As Robert Greene once told me, it’s all material. If you start asking more often, “How can I use this to my advantage?”—your creative output will not only get better, your life will too.

– Speaking of Robert…I’ve talked before about my notecard system—the process I use to research and write my books, which I learned from Robert. As he says, “A lot of books fail because the writer loses control of the research. You are either a master of the material or it’s the master of you.” That’s true beyond books: You either master your to-do list or the day masters you. You either set clear priorities or get lost in trivial tasks. You either build systems or get overwhelmed by chaos.

– A formative lesson for me when I was Robert’s research assistant came when he sent me off to find stories for his writing. I’d spend weeks gathering material and bring back options I thought might work. At one point, looking over what I’d found, he said something like, “Ryan, all your stories are from nineteenth-century white guys. That’s not going to work.” He wanted diversity in his examples—not just so every reader would feel included, but because a book on the laws of power or mastery or human nature would be incomplete if it only drew on white men from the nineteenth-century.

– One more from Robert. He once told me a book needs to be either extremely entertaining or extremely practical—most fail because they fall somewhere in between. He taught me to ask: What role does this book play in someone’s life? Does it justify its cost to the reader? Readers are customers, and many authors forget that, thinking readers are just lucky for whatever the artist creates. Robert helped me see that a book has to do a job.

– My research assistant Billy Oppenheimer recently reminded me of a time I once called him about some piece he was working on, and said, “You know the ‘go for the throat’ story in Courage Is Calling?” (Early in the Korean War, with U.S. forces trapped and the enemy advancing, General MacArthur strode to the blackboard, circled the point of attack, and said, “That’s where we should land…go for the throat.”) “That should be your motto,” I said, “write it down. Don’t spin your wheels or backstory your way into the story—grab the reader by the collar and rip them immediately into the story.

– For a long time, my writing habit was all-or-nothing—either I wrote a lot of words or I didn’t. Over time, I’ve lowered the stakes: now the question is simple: “Did I make a positive contribution to my writing today?” Sometimes that means writing, sometimes editing, adding, deleting. Sometimes I’m home and it’s in my office, sometimes I’m on the road and it’s on a plane or in a hotel room. Sometimes it’s a big contribution, sometimes it’s a little contribution. The line from Zeno was that big things are realized by small steps. That’s what I try to remind myself: every day, just make a positive contribution.

– Related…I once asked one of my favorite writers, Rich Cohen, about how he’s able to be so consistently productive at such a high level. He said he approaches a big project like he approaches a cross-country road trip. “The way you deal with long road trips is you set yourself a minimum number of hours a day, no matter how you feel.” The point is that “not much” adds up if you do it a lot.

– Counterprogramming is key. Writing The Obstacle Is the Way and later launching The Daily Stoic might have seemed crazy. Not just to me—everyone said so. Who was going to care about some obscure ancient philosophy? The world wasn’t exactly clamoring for books or daily content about Stoicism. But that’s exactly why it worked. It was crazy because no one else was doing it. It was different. It stood out.

– The best way to market your writing is to write the marketing into the writing. My explicit mission with Trust Me, I’m Lying was to write an exposé of the media system that would shock and appall anyone who followed the news or worked in marketing world. The book was written to provoke, to challenge, to make people uncomfortable enough that they would talk about it. As Elizabeth Wurtzel put it, “Either you’re controversial, or nothing at all is happening.”

– Nothing is so good that it just finds its audience. You have to bring it to them. As literary agent Byrd Leavell puts it to his clients: “You know what happens if your book gets published and you don’t have any way of getting attention for it? No one buys it.” Plenty of artists can make great work. Not everyone has the dedication to make great work and market it. Marketing is where you distinguish yourself and beat out the talent whose entitlement or laziness holds them back.

– Most of all, I’ve learned to enjoy the work. A few years ago, I was talking to a retired pro athlete and they were telling me how they regretted not enjoying the game as much when they played, that they hadn’t had more fun while they played. It wasn’t a particularly unique insight. I’ve heard it in a million speeches and interviews, but I was in the middle of a particularly hard writing project at the time and not having much fun. I remember thinking: I’ve made it. I’m a pro at this really cool job…why am I not enjoying myself? I’ve made a conscious effort since to appreciate that I get to do this, to not let it turn into a grind or a slog.

June 18, 2025

38 (Or So) Lessons On The Way To 38

There is something melancholic about birthdays. I’m not the first to notice this. Another year has gone by, a wise man once said, and we can’t help but note how little we’ve grown. “No matter how desperate we are that someday a better self will emerge,” he said, “with each flicker of the candles on the cake, we know it’s not to be, that for the rest of our sad, wretched pathetic lives…this is who we are to the bitter end…..inevitably, irrevocably. Happy birthday? No such thing.”

Marcus Aurelius?

Not quite, although Jerry Seinfeld is now a Marcus Aurelius fan, I am happy to report.

I’ve always loved that scene from Seinfeld (which happens when George tells Jerry to stop being his funny self). I’ve related to it on some birthdays but on others, like today, I don’t. I find I have grown quite a bit during most of my trips around the sun, to the point where I hardly recognize the person who first started these posts a decade ago (you can see my birthday posts for 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, and 37 here). I feel like I have changed a lot in the last year and that a better self has and is emerging.

Anyway, as always, here are 38 things I’ve learned in 38 years.

– I put up my first website a few days after I graduated from high school and I’ve been writing more or less every day since. It hit me recently that that means I’ve been doing this for two decades. And you know what? I’m just starting to feel like I’m getting the hang of it. If you told me twenty years ago that that’s how long real confidence would take, I don’t know if I could have handled it.

– This reminds me of an old Zen story. A student approaches a master: How long will it take? Ten years, he says. What if I work really hard? the student asks. Fifteen years, the teacher says. No, you don’t understand, the student says, I am in a hurry. Ok, then, the teacher replies, twenty years. Mastery is not something you can rush. Nor can you rush the opportunities you think you need. When I look back, that’s one thing I am struck by, how lucky I am that most of my biggest opportunities came later. If I had gotten them when I thought I wanted them, you know what would have happened? I would have blown them because I wasn’t ready.

– I’ve been a runner a long time and as I’ve talked about before, the one thing you get asked all the time as a runner is “Are you training for a marathon?” My answer has always been, “No, this is the marathon.” That is, the day-to-dayness, the doing it for no reason other than because, is the real challenge I’m tackling.

– Along those lines…I love the phrase from the college basketball coach Buzz Williams, be an every day guy. “You have to be Every Day,” he says. “There’s no, ‘We’ll do it tomorrow.’ No. We’re doing it today…You gotta do it every day. And if you can’t do it every day, then you’re going to struggle because it is every day.” I try to be an every day writer. An every day runner. An every day father. An every day spouse.

– Anyway, the last couple of months I have been training a little—I want to do the 26 miles from Marathon to Athens this summer. I haven’t done it yet, so I can’t be certain about anything, but I will say after looking at a lot of the training regimes, I haven’t had to change much. Which was my point all along: If you stay ready, you don’t have to get ready.

– A couple of years ago, my wife suggested I read this book called Fair Play by Eve Rodsky. It’s a great book and will definitely improve your marriage. The funny thing is I think the concept of mental load is equally essential in the workplace. If I give someone a task, I should be able to give them effectively all of it—meaning I shouldn’t have to worry about it or them, they should be updating and keeping me informed, if they run into problems they should come to me with the solutions etc. People who can manage themselves go far in life. People who can’t go nowhere.

– Again, it’s always shocking (and humbling) to discover just how hard it is to get good at something. I’ve been doing The Daily Stoic Podcast since 2018 and the long-form interviews since 2020. We’ve done hundreds of millions of downloads and it did well from the jump—so I think I can say people have always liked it—and yet I had a feeling doing an interview last week (approximately my 550th) that I was just getting the hang of it. But you know what? That sensation—that feeling of really being on the inside of something, finally, the clicking that happens after all that work? There is really nothing like it.

– Why am I rushing my kids? I’m rushing them (and me) where exactly? To the end of their childhood…precisely the thing I will soon enough miss desperately. What will I do with this time I am trying to save, what will I do with this time I get to myself after they go to bed? Watch Netflix?

– ‘Rich’ is how much you see your kids, I’ve been saying at Daily Dad. ‘Power’ is how much say you have over your own schedule.

-When I lived in New York, someone told me, “The thing you have to understand about New York is that things just cost what they cost.” This reminds me of Seneca’s famous line about “paying the taxes of life, gladly.” Things cost what they cost–travel costs delays, fame costs critics, kids cost noise, etc etc–and the sooner you learn to pay these taxes gladly, the happier you will be.

– You are what you won’t do for money. Your priorities and principles are demonstrated by what you say no to.

– I had the excruciating experience last year of updating The Obstacle is the Way for the 10th anniversary edition. Honestly, I would not wish re-reading (especially into a microphone for an audiobook) a book you wrote in your twenties on anyone. And again, that’s a book that has been loved by millions of people! There was so much I had to fix. So much I have gotten better at.

-That being said, if I envy anything about that younger version of myself, it’s that I didn’t have much of the self-consciousness I have now. I was freer. Things were simpler. I didn’t know what I didn’t know. I didn’t have the taste to properly judge or understand what I was doing. There is something to be said for that.

– There’s a line in The Great Gatsby where Jay asks Nick Carraway if he’d like to do a little job for him, a way to make some money on the side. Nick declines and says later, that had he answered differently, perhaps the whole course of his life might have been different. When I look at some of the people I used to work for or knew and I see where they ended up, I often think of how had I made even a few different decisions, I could have ended up on a very different trajectory.

– By very different, I mean very different. For instance, it occurs to me now that I was probably being vetted for something by Peter Thiel (I too had written a memoir he’d liked…). I could have gone to Washington in 2017. I’d like to think I was always just a little too independent to get fully sucked into anyone’s orbit. But maybe I just got lucky. The point is: Each of our choices adds up to who we are going to turn out to be.

– I am very ambitious as a writer. I no longer have any ambitions as an author. I’m not aiming at lists. I don’t think about deals. I rarely even look at sales numbers. I have stopped tracking how other people’s books are doing. What I’m saying is that I have locked into process and tuned out publishing. The funny thing is that my results have gotten better the more I have flipped this ratio. I have also gotten much more content.

– The people who are most successful in life, who accomplish the most, who dominate their professions—they don’t care that much about winning. They are obsessed, instead, with improving at the thing they love doing.

– Most labels are unhelpful, too—filmmaker, writer, investor, entrepreneur, executive. These are nouns. But what gets someone to that position? Verbs. Forget the nouns. Focus on the verbs.

– I don’t know what AI will mean or do over the long term. What I can say is that I have gotten a lot out of it. I mean that practically (for instance, it’s helped me fill out graphics and illustrations in my talks and in the Daily Stoic videos), but I also mean personally. As in, in figuring out how to use a new technology, I feel invigorated and improved. I’ve read books about it. Listened to podcasts about it. We talk about it in our weekly staff meetings. I’ve taught my kids about it. It is good to figure new things out. It is good to be a beginner at something again.

– You know what AI isn’t going to replace? Actually, what it will necessitate even more? A good bullshit detector. It may well turn out that the most valuable thing a person can have in this new era is a broad liberal arts education and a strong dose of common sense.

– As I waited at my gate at the airport for an extra hour or so the other day, it occurred to me: This is what anxiety steals from you. Or rather, this is what we steal from ourselves when we are anxious. I could have been at home with my kids, but I had let the remote possibility of traffic override my ability to do that. It occurs to me this is true not just for time, but for the present moments it takes from me and for the conflict it sucks me into. Anxiety is expensive.

– Related…I had an incredible conversation with Dr. Becky Kennedy that every parent—or really just any human—needs to listen to. (If you haven’t read her book, Good Inside, yet…what are you doing?!). In the episode, she defined anxiety as “some amount of uncertainty coupled with our underestimation of our ability to cope.” It reminded me of what Marcus Aurelius writes in Meditations: “Consider all that you’ve gone through, all that you’ve survived.” If these last five years haven’t given you a sense of your ability to cope…I don’t know what will.

– The less news I consume, the more informed I seem to get. “Read not the Times,” Thoreau wrote. “Read the Eternities.” Read old books. Read philosophy. Read history. Read biographies. Study psychology. Study the patterns of history. Read The Great Influenza to be informed about pandemics. Read All The King’s Men and It Can’t Happen Here to be informed about the demagogues of this moment. Read The Moviegoer to understand your listless teenager. Read The Years of Lyndon Johnson to study power and ambition. Read the Stoics. And definitely, definitely, definitely, read Zweig’s biography of Montaigne (which I talk about here).

– I’m not sure I’ve ever opened a social media app and then after logging off thought, “Wow, I’m so glad I did that.”

– Conversely, I have never taken a walk without thinking, after, “I am so glad I did that.”

– I am always glad I jumped in the water. Even when—perhaps especially when—it’s really, really cold.

– It’s also rare that I have regretted asking for help. Sure, sometimes it can be more trouble than it’s worth, but at least I got some practice doing a thing that’s hard–being vulnerable, putting myself out there, connecting with someone.

– At least once a week, someone asks us if we’re going to open a second location of the bookstore. And at least three struggling bookstores have reached out about us acquiring them. The answer is usually a polite “no.” Sometimes it’s “Are you insane?” “Do Not Go Past The Mark You Aimed For” is one of the most important laws in The 48 Laws of Power. Know when you’ve won. Know what enough is. Know your limits.

– A couple of months ago I was working on something in a car from JFK to Manhattan. The car bounced and the Sharpie I was using made a little mark on the door. It was stupid for me to have been using a permanent marker in a moving car, but obviously, the driver didn’t see and I could have just gotten away with it. It was weird how much I had to work myself up in my head to tell the driver when I got out. “If you have to charge me for it, I understand,” I said. It was an uncomfortable little conversation, but I’m glad I had it. I honestly don’t even know if they ended up charging my card for anything, but if they did it was worth it. Calling fouls on yourself is not fun, but it’s a habit you need to build.

– A day or two before my ill-fated talk at the Naval Academy in April, as I was weighing whether I was going to speak up about the book bannings on campus in my remarks, I emailed someone who I really admire. They are a USNA graduate and someone who has served their country for many years with quiet, honorable leadership. I said, hey, I’m thinking about saying something but I don’t want to cause trouble for anyone and I definitely don’t want to get a good person fired (especially if they end up replaced by someone worse.) This is what they wrote back:

“I think you should just speak directly about what you truly believe. That is always a path.”

– I will say, in these deranged times we live in, one thing I have continually taken solace and inspiration from is when smart people or people whose work I respect, take a little time out of their day to say “Hey, I’m not OK with what’s happening,” or use their platform to reiterate basic values like decency, honesty, justice or kindness. Maybe this doesn’t feel like much to them or to you, but we are social creatures. We look around us, we look above and below us and we make our choices based on what we see other people doing. Deciding to stay silent breeds silence and complicity. Speaking up breeds courage and virtue.

– After a flight into LAX and a long drive to Palm Springs, I finally got my family into our hotel room. Then I started changing to go for a run. Are you out of your mind, my wife said. It was 4pm and 104 degrees out. “That’s not self-discipline,” she said, “that’s self-harm.” She’s probably right. It’s a fine line…and sometimes my problem is too much discipline, not too little.

– Something I’ve started saying all the time to employees: “Let’s start the clock on this.” If the bindery says it’ll take six weeks to make another run of the leatherbound Daily Stoic, I want to “start the clock” as soon as possible. I don’t want to add days or weeks by being indecisive, procrastinating, or slow to process an invoice. We don’t control how long others take, but we do control whether we waste time on our end. The project will take six months? Start the clock. You’re going to need a reply from someone else? Start the clock (send the email). Getting the two quotes from vendors will take a while? Start the clock (request it). It’s going to take 40 years for your retirement accounts to compound with enough interest to retire? Start the clock (by making the deposits). It’s going to take 10,000 hours to master something? Start the clock (by doing the work and the study).

– Whenever I go and do something with my kids (like a trip or an activity or an errand) I try to tell myself: Success is wanting to do this again. That is to say, it’s not about accomplishing anything or checking off certain boxes—did we see all the sights, did we get what we needed to get, did we arrive on time or whatever—it’s ultimately whether we got along well enough, enjoyed the experience enough, that at some point in the future they’ll say: “Hey, remember when we went to that concert? Can we do that again?” or “Oh, you’re driving across town to grab that thing? Can I come?”

– For a long time, my writing habit was all-or-nothing—either I wrote a lot of words or I didn’t. Over time, I’ve lowered the stakes: now the question is simply, “Did I make a positive contribution to my writing today?” Sometimes that means writing, sometimes editing, adding, deleting. Sometimes I’m home and it’s in my office, sometimes I’m on the road and it’s on a plane or in a hotel room. Sometimes it’s a big contribution, sometimes it’s a little contribution. The line from Zeno was that big things are realized by small steps. That’s what I try to remind myself: every day, just make a positive contribution.

– It’s important to realize that most of the time people are not playing three-dimensional chess. Most of the time they are slaves to their emotions and impulses. Most of the time they have no idea what they’re doing at all. I’ve been amazed at the degree to which smart people I know manage to convince themselves that what they’re seeing is part of some thought-out plan and thus rationalize what is obviously insane or explain away what would be otherwise deeply alarming. We forget Hanlon’s Razor at our peril.

– When we were working on What You’re Made For, George Raveling—who I think is one of the most remarkable people of the 20th century—said that when he wakes up in the morning, as he puts his feet on the floor but before he stands up, he says to himself, “George, you’ve got two choices today. You can be happy or very happy. Which will it be?” (Voltaire put it another way I love: The most important decision you make is to be in a good mood.)

– The basic most essential of responsibilities: Do not let assholes turn you into an asshole. To not let the cruelty harden you, to not let stupidity make you bitter, to not let outrage pull you down to its level, to not let the sonsofbitches turn me into a sonuvabitch. It is a timeless struggle, as Zweig put it in 1942 about Montaigne in 1562, saying that we must “remain human in an inhuman time.”

– Remember, you don’t die once at the end of your life. You are dying every second that passes. We are going in one direction. Don’t rush through it. Don’t miss it. Have something to show for it.

—

I feel very lucky not just to be 38 but to be here at 38. I have been blessed in so many ways. I have been able to live so much. I’m good. If I get to do another one of these a year from now, I’ll be grateful, but it will be a bonus.

I spoke at a biohacking conference a few weeks ago where the stated purpose was all about living well into your hundreds. I teased them a little. Why? I said. So you can spend more time on your phone? So you can accumulate more stuff? So you can check more boxes off your to-do list? It’s not like these were researchers trying to cure cancer or engineers trying to bring clean water to communities that don’t have it, or scientists trying to solve the climate crisis—people whose services the world desperately needs…yet we all think we need to, deserve to, live forever.

I hope I get a lot more time with my kids and my spouse and my work, I do. But I also understand that I’ve gotten a lot of time on this already—and that too much of it I wasted or didn’t appreciate in the moment.

These 38 years have been good to me, better perhaps than could be reasonably expected. I think I’ve used them well. I hope you do, too.

June 4, 2025

You Are What You Won’t Do For Money

—Today’s newsletter is sponsored by Shortform.

It was a sales pitch, so I take it with a grain of salt, but according to an email I got a few weeks ago, I have a seven-figure opportunity sitting in front of me.

And I’m apparently too stupid or closed-minded to see it.

All I would have to do is partner with a supplement maker and produce a line of supplements connected to the Daily Stoic brand—marketing their ability to help with “calm, clarity, and resilience”—and I could very easily make several million dollars. They’d handle everything: procurement, production, design, fulfillment. I’d just have to lend my brand and my platform to do it.

The only problem? I don’t want to.

I’m not exactly opposed to supplements or vitamins. I actually take a few each morning. I even advertise some on the Daily Dad and Daily Stoic podcasts. Nor am I opposed to making money. I don’t think there is anything wrong with it, and neither did the Stoics (“No one has condemned wisdom to poverty,” Seneca writes in On The Happy Life. “The philosopher shall have considerable wealth, but it will not have been pried from any man’s hands, and it will not be stained with another man’s blood.”)

But I have always declined to do things like Daily Stoic T-shirts and hats and cheap merch: It doesn’t feel right. It doesn’t get me excited. It doesn’t seem like a responsible use of my platform.

So as long as I’m in charge, it won’t be.

I remain a proud capitalist. I have built companies and invested in many others over the years. I make and sell a lot of things for Daily Stoic. But I like the things we make. I believe in them. They were things I wanted to create for my own personal use or that I thought addressed a real need—that they worked commercially was extra. (Nor do I pressure anyone about them. If you don’t like it…don’t buy it! That’s the other part of capitalism when it works well: It is a voluntary exchange.)

I understand that there is a certain privilege in my attitude, which is why I do my best not to judge people in different financial circumstances. At the same time, I have come to believe that we are defined by the things we don’t do for money.

Do you know who Audie Murphy is? He’s the most decorated soldier in American history. Before he turned 21, he fought in nine campaigns, was wounded three times, and received 33 medals for valor—including the Medal of Honor, three Purple Hearts, and every combat decoration the Army offers. Once, against an onslaught of 250 German soldiers and six tanks, Murphy ordered his men to fall back to safety—alone, he climbed into a burning tank destroyer and used its single machine gun to hold off the Nazis for over an hour, single-handedly killing 50 of them, refusing to give an inch of ground, holding the woods until reinforcements came. (Read his memoir, To Hell and Back…it’s incredible.)

After the war, he became an actor and a musician. In 1968, he did another courageous deed: he turned down enormous sums of money to appear in a series of cigarette and alcohol commercials. “How would it look: ‘War Hero Drinks Booze’?” he said. “I couldn’t do that to the kids.”

I was also struck by Harry Truman’s ability to rise up through the corrupt Kansas City political machine without being corrupted. “In all this long career, I had certain rules I followed, win, lose or draw,” Truman explained. “I refused to handle any political money in any way whatever. I engaged in no private interest whatever that could be helped by local, state or national governments. I refused presents, hotel accommodations or trips which were paid for by private parties…I made no speeches for money or expenses while I was in the Senate. I lived on the salary I was legally entitled to and considered that I was employed by the taxpayers, and the people of my country, state and nation.” I was even more struck by his post-presidency years because they stand in such contrast to the practice today: Truman was nearly broke after leaving office. In fact, the reason there is a presidential pension is because people were concerned about a destitute former president! Yet for Truman, this outcome was vastly preferred to compromising his principles.

In Right Thing, Right Now, I tell the story of Martha Graham, who was approached in 1935 with the opportunity of a lifetime: an invitation to present her work at the upcoming Olympics. It was a chance to dance on the world stage, the kind of opportunity that no talented or ambitious person could afford to turn down.

Yet there she was, turning it down.

“Three-quarters of my group are Jewish,” she told the emissaries from Berlin. “Do you think that I would go to a country where they treat hundreds of thousands of their coreligionists with the brutality and cruelty that you have shown Jews?” Shocked that self-interest hadn’t worked—that she wouldn’t look the other way like so many others—the Nazis tried a different tactic. “If you don’t come,” they warned, “everyone will know about it and that will be bad for you.”

But Graham knew precisely the opposite was true. “If I don’t come,” she said, “everyone will know why I didn’t and that will be bad for you.” She may have been a starving artist well into her forties and could have used the money and exposure, but it wasn’t worth her integrity. It wasn’t worth her soul. By acting on her principles, she struck a public blow against an evil not enough people had yet condemned.

Back in April, I told this story on stage at the global gathering of the Entrepreneur’s Organization. Everyone broke out in applause at Graham’s line, but as they say–and as Graham would have experienced–you can’t live on gratitude or respect. It must have been a hard choice. It must have been a scary choice. It was the right thing to do as a person…but it didn’t change the fact that she still had her financial obligations as a businesswoman with dancers to support.

Every entrepreneur knows that struggle. You have your views…and you also have payroll to meet. Or investors to satisfy. Or your ego to fill…

It’s the scene in The Great Gatsby where Gatsby approaches the young Nick Carraway, the cousin of Daisy Buchanan, the love of Gatsby’s life. Ultimately hoping to win back Daisy, Gatsby tries to first win over Carraway. “I carry on a little business on the side, a sort of sideline,” Gatsby tells him. “And I thought that if you don’t make very much…this would interest you. It wouldn’t take up much of your time and you might pick up a nice bit of money. It happens to be a rather confidential thing.”

It’s only later that Nick, understanding more clearly that Gatsby was a gangster and a bootlegger, comes to see that “under different circumstances that conversation might have been one of the crises of my life.” Gatsby was trying to draw him in, hoping to hook him on the money and the lifestyle.

I have not always been good at this and I have gotten myself into some fixes that might have gone badly for me. I sometimes look back at clients and people I worked for in my twenties—and even later—and I feel the urge to take a shower. Growing up, I suspect I heard my parents talk more about financial success than about integrity or ethics. It took time for me to develop both the character and the confidence to be better able to say “NO” to things that gave me the ick or that seemed iffy.

I wrestle with it still. I turned down a talk last year from an organization I thought was a scam. I weighed whether I should cancel another one recently with someone whose politics I find abhorrent.

My reading has helped me get better at this. Perhaps because my inclination was to make money, I found it particularly impressive when people turned down an opportunity to make money. Especially when those people really needed it. Especially when it was a lot of money.

Imagine if you had been offered one of those enormous greenwashing contracts from LIV, a Saudi-backed rival league. Ditching the PGA (and trying to bully their old league into letting them keep their privileges in the process) wasn’t technically illegal. But it was definitely pretty gross.

Rory McIlroy turned down hundreds of millions of easy dollars because he believed that the new league was bad for the game. That where his money comes from matters. That his choices don’t just reflect his own values and priorities, they shape those of the many young players, the future generation of golfers, who look up to him. And that a decision “you make in your life purely for money,” he explained, “doesn’t usually end up going the right way.”

(And by the way, what was his reward for this? His game took a major hit from the distraction and the PGA hung him out to dry!)

But that can be how it goes.

Do you know what they called Truman when he was elected to the Senate? The colleagues who didn’t snub him as a hick referred to him as the “Senator from Pendergast”—implying that he was bought and purchased, in the pocket of Tom Pendergast, the all-powerful Kansas City boss. Truman, who had forgone millions in bribes and deals, still got stuck with a reputation for being corrupt!

If you’re making the right decision because you want to be rewarded reputationally, you’re probably going to be disappointed.

Even though I feel like I’ve made some expensive decisions about what I won’t do in my career—as well as some expensive decisions in how we do what we do (I talk about our manufacturing and import decisions here)—I still have to put up with people accusing me of “$toicism” or being a grifter or whatever. There are plenty of people who dislike the coins we make or the courses we have done—or even the fact that I write books! I turn down all sorts of lucrative ads—from gambling sites and alcohol companies and THC companies and crypto—and still, the comments sections on our videos and the podcast are filled with complaints about advertisers. I’m sure someone will respond to this very email with a disagreement about whoever sponsored it.

That’s something Marcus Aurelius talks about in Meditations—the frustrating experience of “earning a bad reputation by good deeds.” It can even be more galling than that. Someone else will do some kind of Stoic supplement at some point! They’ll probably make a bunch of money from it.

That person will just not be me.

You can’t call it a principle, as the expression goes, unless it has cost you something—money, access, friends, followers, convenience, an opportunity to get ahead.

You shouldn’t call yourself rich unless your hands are clean.

It’s not really your platform unless you decide what goes on it.

You’re not free if you can’t say no.

And you don’t know who you are unless you know what you won’t do for money.

May 21, 2025

This Is Something I’ve Turned To Over and Over Again When The World Seems Dark

But first…Join me live in conversation with my friend and mentor, George Raveling, on May 29th at The Painted Porch Bookshop! George is one of the most remarkable people of the 20th century. He became the first African American basketball coach in what’s now the Pac-12 and went on to have a Hall of Fame career. He was instrumental in bringing Michael Jordan to Nike and has mentored some of the most influential coaches in college basketball. You do not want to miss this event. Get tickets here!

I guess I could try to put into words how much I love this book.

I could try to explain how this 84-year-old book about an obscure 16th-century philosopher is uniquely relevant to our times.

Or I could just tell you I put my money where my mouth is:

I bought 1,000 copies of this book.

Literally.

As in, all the available stock…which I was only able to get after I had my agent connect me with the publisher, Pushkin Press, who I then begged to print one final run before it went out of print.

1,000 copies of Montaigne at The Painted Porch

1,000 copies of Montaigne at The Painted Porch

That is how much I loved this little Stefan Zweig biography of Montaigne.