Ryan Holiday's Blog

October 15, 2025

Without This, You’ll Never Reach Your Potential

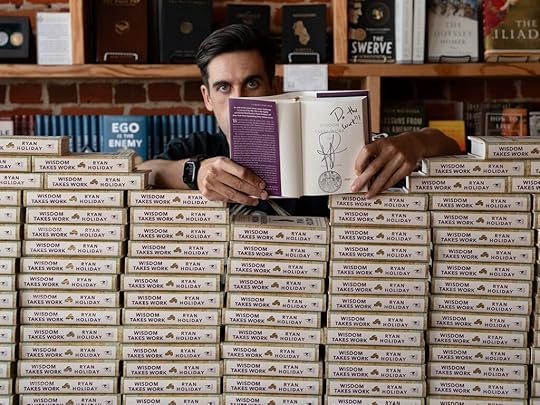

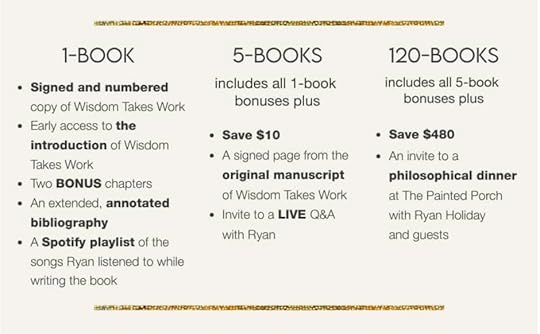

My new book, Wisdom Takes Work, comes out in 6 DAYS! If you’ve gotten anything out of my writing over the years, it would mean the world if you preorder a copy. Preorders are the single best way to support an author and help a book get off the ground. To make it worth your while, I’ve put together a bunch of bonuses—a signed page from the original manuscript, bonus chapters, an annotated bibliography, and more. Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

There I was at 19 years old, sitting across from the great Robert Greene at The Alcove in Los Feliz.

He was talking about all the trouble he was having finding a good research assistant.

I had to restrain myself from jumping over the table.

This was literally my dream job.

Fortunately, before I leapt out of my chair, Robert asked if I might have any interest in giving it a shot.

Thus started for me what Robert calls in Mastery, The Apprenticeship Phase.

It didn’t start with anything glamorous. In the days before AI or even decent software, I spent hours transcribing interviews he had done for his book The 50th Law. I read obscure books he didn’t want to waste time on. I found articles. I worked on his website. I went to libraries and scanned pages. I went through old archives. I tracked people down.

And in between, I asked questions. I listened. I watched. I absorbed his research and note card system, which I continue to use to this day.

Obviously he was paying me, but I always considered having access to him—being able to ask these questions—my actual compensation. The feedback wasn’t always fun, but what would he have normally charged someone as a consultant? How many people would have killed to be able to call him or email him about anything?

When I say I was his apprentice, I don’t mean it like, “Oh, I was his intern for a few months.” I did this for close to 7 years, even after I became the director of marketing at American Apparel. I was even doing it even after I had gotten my own book deal and was working on my first books.

Why?

Because this is how it works.

As the great Jack London writes in his novel Martin Eden, “no matter how peculiarly constituted a man may be for blacksmithing, I never heard of one becoming a blacksmith without first serving his apprenticeship.”

In Wisdom Takes Work—which there are just 6 days left to preorder!—there are multiple chapters on the art of cultivating these mentors and teachers because there is no one who is able to reach their potential totally alone. There is no one who can learn everything they need to learn by trial and error. Wisdom is not a solitary pursuit. It is often a collective effort.

For thousands of years, this is how trades—and life—were taught. Not in a classroom with hundreds of other students, but attached to a professional, who taught, largely by example, until the student was ready to head out on their own. There are some things, the tennis great Billie Jean King would say of her time training under Alice Marble, an eighteen-time Grand Slam Champion, “you can only learn from someone who’s been the best in the world.” Or at least, someone who is world class.

It was from Robert that I learned everything—literally everything—about being a writer. He taught me how to write a book, how to think about books, how to research them, how to market them, how to work with a publisher. He fundamentally taught me, from beginning to end, how the entire process works. In addition to telling me what to do, he showed me how a real pro does the job.

We have to find the people who can teach us and open ourselves to learning from them. Whatever stage of life we’re in, there is someone who knows more than us, who has been through more than us, who can open doors for us.

We are a product of our teachers and our mentors.

There would be no Plato without Socrates. There would be no Aristotle without Plato. There would be no Alexander without Aristotle. There would be no Marcus Aurelius without Rusticus or Epictetus or Antoninus. There would be no Zeno without Crates, and thus there would be no Stoicism without Crates.

Do you know what Crates’s nickname was in ancient Athens? He was known as “the door-opener.” Because that’s what great mentors and teachers do: They open doors to worlds we didn’t even know existed. They invite us into things we wouldn’t have discovered on our own. They help us see possibilities we’d otherwise stay blind to.

How do you find these door-openers? How do you attract their attention? How do you make yourself worth their while?

You have to show yourself as somebody with the hunger to learn and excel. You have to show yourself as somebody who listens. Somebody who is curious. Somebody who is worth teaching. Somebody who is coachable.

Mentors give us books to read. They give us problems to solve. They give us riddles to chew on. They provide an example that inspires or even shames…and sometimes cautions.

The process is not always fun. It will often be painful. As Epictetus would tell his students, having modeled himself on his mentor Musonius, “The philosopher’s lecture hall is a hospital. You shouldn’t walk out of it feeling pleasure, but pain, for you weren’t well when you entered.”

Valuable things are rarely free. An apprenticeship is one of them.

But it’s also priceless.

I wouldn’t be here without it.

There’s no way I can repay Robert for his kindness and his patience and his generosity. But as I explain in the “Grow a Coaching Tree” chapter in Right Thing, Right Now (the third book in the Virtue Series), as well as in the “Be a Teacher” chapter in Wisdom Takes Work, the only thing we can do is pay that forward. The next step is to become a teacher, to help mentor someone else.

Because we learn as we teach.

Because we carry debts from those who helped us—debts that can only be discharged through helping others.

And because, at the end of your career and your life, you’ll be prouder of what you helped others accomplish than what you achieved yourself.

But only if you put the work in now…working as hard to open doors for others as you work to open doors for yourself.

***

For the past six years I’ve been lavishing all my working hours on the Stoic Virtues series and I can honestly say Wisdom Takes Work , the fourth and final book in the series, is the culmination of my life’s work.

There are just SIX DAYS left to pre-order Wisdom Takes Work !

Each time I release a book, I like to do a run of preorder bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, early access to the introduction, bonus chapters, and even an invite to a philosophy dinner at my bookstore, The Painted Porch.

Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

October 8, 2025

Do You Know How To Do A Deep Dive?

My new book, Wisdom Takes Work , comes out in 13 DAYS! If you’ve gotten anything out of my writing over the years, it would mean the world if you preorder a copy . Preorders are the single best way to support an author and help a book get off the ground. To make it worth your while, I’ve put together a bunch of bonuses—signed and numbered first editions, a signed page from the original manuscript, bonus chapters, an annotated bibliography, and more. Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

I thought I knew a lot about Lincoln.

I’ve read biographies—an embarrassing amount of them honestly. I’ve watched documentaries. I’ve interviewed scholars. I’ve traveled to many of the sights. I’ve read many of his favorite books. I’ve immersed myself in the world he lived in. I once stood transfixed, for hours, in front of Krzysztof Wodiczko’s art piece, which projected the faces and experiences of American veterans on the face of Lincoln’s statue in Union Square Park in New York.

I’ve even written about him quite a bit in my books.

So when I sat down to put together what was intended to be Part III of Wisdom Takes Work, I thought I was set.

It turns out I wasn’t even close.

I was stuck and I could not find the words. That might seem like writer’s block but it wasn’t—because writer’s block doesn’t exist. What is real is lacking material and that’s what I was facing.

So I got to work.

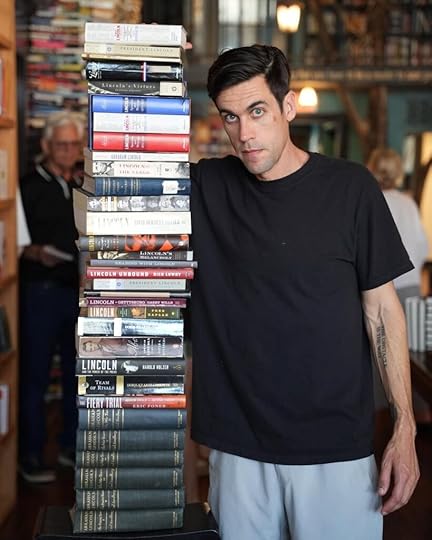

I read Michael Gerhardt’s 496-page book on Lincoln’s mentors.

I read Hay and Nicolay.

I read Doris Kearns Goodwin’s 944-page Team of Rivals.

Still, there was more to know.

So I read David S. Reynolds’s 1088-page Abe, David Herbert Donald’s 720-page Lincoln, and Garry Wills’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book specifically about the Gettysburg Address (Wills’s book has many more pages than the address has words).

I spoke with the documentarian Ken Burns about him, and Doris too.

I went back through the books I’d already read (William Lee Miller, especially, but also Harold Holzer, Joshua Wolf Shenk, and Carl Sandburg).

I read Lincoln’s own writings, his letters and his speeches.

I reviewed my pictures from trips to Gettysburg, Antietam, and Ford’s Theater.

I went, multiple times in the course of writing the book, and looked up at the Lincoln Memorial.

In the end, I spent hundreds of hours reading thousands and thousands of pages on the man. Here’s what that looks like in physical terms.

Basically, what I was doing was a deep dive. Fittingly, Lincoln’s own education was itself a kind of lifelong series of self-directed deep dives. He got his start in law, for instance, when he met a lawyer named John T. Stuart, who allowed Lincoln to borrow some of his law books. “If you wish to be a lawyer,” Lincoln would later tell a young man, “attach no consequence to the place you are in, or the person you are with; but get books, sit down anywhere, and go to reading for yourself. That will make a lawyer of you quicker than any other way.”

His campaign against slavery, too, began by going deep. “He searched through the dusty volumes of congressional proceedings in the State library,” William Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner, recalled, “and dug deeply into political history.” His way, Herndon observed, was to dig up a question by the roots and dry it out by the fires of the mind, until he could see it for what it was.

Do you know what Lincoln did after the Civil War broke out? He broke out an old habit, which he’d had since his time in Washington as a congressman: He called for books from the Library of Congress, reading everything he could about strategy and tactics, including books published by his own generals. He was, by the end of the war, according to General W. F Smith, “the superior of his generals in his comprehension of the effect of strategic movements and the proper method of following up victories to their legitimate conclusions.”

Nowhere was this ability to see things plainly more evident than in the Gettysburg Address, which was just 271 words long. You might think such a short speech was easy to write, in fact, it was the descendent of a decade-plus-long deep dive into language, elocution, rhetoric, history, law, politics and the founding ideals of the nation—a word he repeated in the speech five times. It was an expression of the work Lincoln did to get to the “nub” of a subject, as his law partner said. As Wills writes in Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, Lincoln was able to, as a result of his masterful understanding of the issues and opportunity at hand, to effectively redefine and refound the nation in a single speech, in a way that two and a half years of war had not been able to.

Going deep in order to get to the nub of subjects—this is a skill you need to have. Whether you are an author, a politician, a lawyer, entrepreneur, scientist, educator, parent—it doesn’t matter you have to be able to pursue an idea, a question, a thread of curiosity until you’ve wrapped your head completely around it.

In Right Thing Right Now, I spend a lot of time talking about the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, who like Lincoln was able to strike a defining blow against slavery. Obviously this is what we’re talking about when we talk about justice. But how did he do it? Clarkson knew slavery was wrong. He even wrote a convincing essay on it.. But he soon realized that if he was going to do something about it, he would really have to understand slavery—as a business, a logistical enterprise, and a set of cultural assumptions passed down for thousands of years to justify it. So he immersed himself in the abolitionist movement, meeting and learning from the earliest activists, reformers, and freed slaves. He visited slave ships. He would recall that the almost uninhabitable quarters, the chains and grates, filled him “with melancholy and horror,” kindling, he said, “a fire of indignation.” But now his anger was fueled by facts, and he wanted more. He spoke to everyone he could find who had been to Africa, recording their accounts in his notebooks. He scoured records at the Custom House, poring over muster rolls, ship logs, trial transcripts, and insurance files.

Often falling asleep over paperwork, surrounded by his research, Clarkson persisted for years. By the end, no one knew more about the slave trade—he was more informed than many traders and investors themselves, since so much of what they did depended on deliberate ignorance.

You can’t solve a problem you don’t understand. You can’t lead a field you haven’t immersed yourself in. You must go down the rabbit hole. You must go deep. You must swarm the topic.

This has been my approach to pretty much everything I’ve done since dropping out of college. It’s how I figured out how to be a writer. It’s how I figured out how to be a researcher. It’s how I figured out how to be a parent. It’s how I figured out how to run a bookstore. Indeed, my whole life has been built on deep dives.

If our goal is to get not just smarter or more knowledgeable, but wiser, we cannot be content to learn in half measures. We must go as deep as we possibly can. We don’t just read a book on a topic. We have to read everything we can find on it. We don’t just ask a question or find an expert. We have to find every expert we can and ask them every question they’re willing to answer. We don’t just look at what’s there. We have to explore the remotest corners, every facet, from every angle. We have to hear from people we agree with and from people we disagree with. We have to go out and get real experience.

As an old man Marcus Aurelius would reflect on the most important lesson he had learned from his philosophy teacher Rusticus: “to read attentively—not to be satisfied with ‘just getting the gist’ of things.” Go “directly to the seat of knowledge,” he said. Immerse yourself in the craft, business, sport, or profession. Seek out tutors and mentors and peers. Travel. Observe. Ask questions. Go way beyond the “gist.”

The great biographer David McCullough talked about swarming the subjects he wrote about—reading their diaries, their favorite books, biographies of their heroes, newspapers from their time, and, most importantly, spending time in the places they had spent time. “I believe strongly,” he once said, “that terrain, landscape, the physical environment is not just important in understanding someone or something—it’s elemental. Therefore, I go to where things happened.”

The jazz legend Miles Davis didn’t just go down to the club and listen to music. “I would go to the library and borrow scores by all those great composers, like Stravinsky, Alban Berg, Prokofiev. I wanted to see what was going on in all of music,” he explained. All of music. Old stuff. New stuff. The greats. The weirdos. “Knowledge is freedom and ignorance is slavery,” he said, “and I just couldn’t believe someone could be that close to freedom and not take advantage of it.”

The Wright brothers didn’t discover flight through a single epiphany but through countless hours watching birds. “We couldn’t help but thinking they were just a pair of poor nuts,” one Kitty Hawk resident recalled. “They’d stand on the beach for hours, watching the gulls flying, soaring, dipping.” They even studied how paper fell and floated to the ground, again and again.

Wilbur’s notebooks are filled with drawings of birds, notes on flight techniques across species, and how weather affected flight. They include sketches of wind-tunnel tests and designs. Others had observed birds, but no one had gone so deep—or spent so much time—studying the mechanics of flight and wings.

To capture the progression from ignorance to knowledge to wisdom, McCullough used the example of the pilot’s cockpit. You can get a pretty good understanding from someone describing what a cockpit is. An even better understanding from reading about cockpits. An even better understanding from looking at pictures. An even better understanding from watching videos. An even better understanding from sitting in a cockpit. And an even better understanding from flying a plane.

This is our job. To make things clear. To get to the nub of things. To find what is important and discard the rest. To go deep. To swarm.

This, of course, takes time.

It takes curiosity.

It takes patience and persistence.

Most of all, as I put in the title of the new book, it takes work.

***

For the past six years I’ve been going deep on the four virtues, and I can honestly say Wisdom Takes Work , the fourth and final book in the Stoic Virtues series, is the culmination of my life’s work.

The book comes out October 21st, but it would mean the world to me if you could preorder the book from dailystoic.com/wisdom . Preordering a book is the number one thing you can do to support an author as they get a book off the ground. It’s how publishers determine how many copies to print, whether other bookstores will carry it, and where the book will land on the bestseller list.

To make ordering it early worth your while, I put together a bunch of bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, a signed page from the original manuscript, bonus chapters, an annotated bibliography, and a bunch of other stuff. Just head to dailystoic.com/wisdom before October 21st to claim your bonuses.

October 2, 2025

This Hobby Can Change Your Life

My new book, Wisdom Takes Work , comes out in a few weeks. Get signed & numbered first editions here !

I have a hobby and it’s weird.

It started in a pretty normal way.

I’d always liked taking walks and then I had young kids.

Because it was often the only way I could get them to sleep–or to keep them out of the house so my wife could sleep–I would spend hours and hours walking on the rural country road that we live on.

It is unpaved and unmaintained by the county or the state, lined with trees, and more frequently crossed by deer and jack rabbits than people. We’d do miles and miles, first in the baby bjorn, then the single stroller and then the double stroller. We see the sun come up or the sun go down. We crunch the frost and the mud. We’d do it in the heat and the cold, on ordinary days, for the interminable months of the pandemic, weekdays and weekends, rain or shine.

It’s a throwback to an older, simpler way of life.

It’s also a throwback to a scene I’ve always remembered from Mad Men, where Don Draper and his family finish their roadside picnic and then nonchalantly throw all their trash into the grass below.

Only out here, because the police don’t seem to mind or our local government is non-existence, they dump tires and old mattresses. They dump debris from construction sites. They dump beer bottles and candy wrappers. They dump out of season deer kills and for some inexplicable and alarming reason, a lot of dead dogs.

At first, this just pissed me off—especially because the nails kept giving me flats. It would make whole segments of the road unwalkable with the kids because of the stench. I tried calling the police and animal control and my local politicians—of course, they did nothing. I put up fake cameras which did nothing to deter. I thought about moving.

But then one morning on my walk with my kids, a thought hit me that was both freeing and indicting. How many times do I have to walk past this litter, I thought, before I am complicit in its existence? Why do I keep expecting someone else to do something about it if I won’t? So I started cleaning it up…and I actually enjoyed it. We started cleaning it up.

I have a bag, one of those sticks with a spike on it, and I go up and down the country roads where we live. I have a claw and gloves (I have gone through many many pairs of gloves). I go down in the gullies by the side of the road picking up soda bottles, plastic bags, food wrappers, nails, and screws. I have disposed of dumpsters worth of garbage over the years. I have loaded tires into the back of my truck and paid to have them properly recycled. (I’ve even paid a contractor to come out with a tractor for some particularly heavy stuff). I have put on face masks and scooped up dead goats, dead calves and dead dogs which I burned or took to the back of my ranch to decompose in a less disruptive place. I have paid my children an ungodly amount of bribes to get them to participate too.

I don’t just do it at home either. I do it when we go to the beach. I do it when we go on hikes. I do it when I’m pacing in a parking lot, taking a phone call. I think I’d want someone to grab this if they saw it, so I’ll do the same.

Does it make a difference? In the big scheme of things, no. Does it create a moral hazard? Maybe. Perhaps word has gotten out—dump your stuff down here because it mysteriously disappears a few days later.

I’m not sure my neighbors have noticed. In fact, one time, as I loaded up a mattress in my truck, someone who lives down the road accosted me, thinking I was the dumper. Honestly, the only time anyone has ever said thanks happened in another country. I was in Greece this summer and I passed a flattened water bottle in the street, which I reached down and grabbed and tossed in a nearby trash can. An old man sitting in a cafe stood up and began clapping and bowing and shouting in unintelligible Greek. I assume he was saying thanks, but maybe he was making fun of me.

I’ll tell you it doesn’t earn you karma, not at least during this lifetime. Despite all the work my wife and I still get a flat tire every month or so.

But that’s not why I do it.

I do it for me.

In a world where everything seems to be falling apart and so much is beyond my control, there is something deeply empowering about this simple, weird act. I can see the difference every time I drive home—the road is cleaner, safer, more beautiful. I’m outside instead of stewing indoors. I’m moving instead of scrolling. I’m solving a problem instead of complaining about it.

There is a Mr. Rogers quote I love. “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news,” Rogers said, “my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’”

We decide what we look for in life—do we get mad at the people making the mess or do we look towards the people cleaning things up? We decide whether to despair or find hope and goodness.

But I actually think we can go further. Do we decide to BE one of the helpers? Do we decide to pick up the trash? Do we take ownership of the things within our control?

That’s what makes the difference…and life better for everyone, but especially you.

***

For the past six years I’ve been lavishing all my working hours on the Stoic Virtues series and I can honestly say Wisdom Takes Work , the fourth and final book in the series, is the culmination of my life’s work.

Wisdom Takes Work is a book about the work of our lives: the work it takes to acquire wisdom. The book is filled with the example and insights of some of history’s wisest people, and how we can follow in their footsteps.

It comes out on October 21st, but is available for preorder over at dailystoic.com/wisdom . Each time I release a book, I like to do a run of preorder bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, early access to the introduction, bonus chapters, and even an invite to a philosophy dinner at my bookstore, The Painted Porch.

September 17, 2025

We Must Not Devolve Into This (Or We Risk 2,500 Years of Progress)

Before we get into it…with the upcoming release of Wisdom Takes Work —the fourth and final book in my Stoic Virtues series —we’re doing a collector’s set of all four books . There’s a limited run of these, so pre-order them here today . I’m also giving a talk in San Diego in February about applying the Stoic virtues to modern life and modern problems. Grab seats and come see me !

On the night of April 4, 1968, Robert Kennedy, then running for president, was about to give a speech in inner-city Indianapolis when he got the news that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated.

It had already been a grueling campaign. It had been a painful few years. And now, another murder, more violence.

Kennedy was the one who had to break the news to the milling crowds that King, their leader, was dead. The crowd, roiling with anger and despair, was on the verge of riot.

His prepared marks woefully insufficient for the moment, Kennedy began to riff. It was a crossroads moment, he said: “In this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in…You can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization. Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.”

To those tempted to move in the direction of hatred and revenge, Kennedy said, “I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling,” for his own brother had been struck down the same way just five years earlier. But he also knew personally what a dark and empty road that was. “We have to make an effort in the United States,” he said, “we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.”

Then, he drew on a line from one of his favorite books, The Greek Way by the classicist Edith Hamilton. On a ski vacation four years earlier, Kennedy was loaned a copy of the book and ended up spending most of the trip holed up in his room, absorbed in Hamilton’s wonderful discussion of what made the Greeks so special, what they can teach us, and how they thought about life. It was from her book that he had read a line by the ancient Greek poet Aeschylus that stayed with him. And there in Indianapolis, from memory, he recited it:

“In our sleep, pain, which cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.”

“What we need in the United States is not division,” Kennedy explained. “What we need in the United States is not hatred. What we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness. [What we need is] love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black.”

He urged the attendees to return home and to pray, and offered them an alternative, a chance to take meaning from this terrible experience. “Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago,” Kennedy said, “to tame the savageness of man and to make gentle the life of this world.”

All over the country similar crowds erupted into mobs, which turned into deadly riots. But in Indianapolis that night, largely because of Kennedy’s words, the people chose peace and restraint over rage and violence.

The reality is that political violence is not unprecedented in American history. It has always been there, lurking beneath the surface of our democracy. In fact, if you’ve read Bryan Burrough’s Days of Rage (or listened to my conversation with Bryan), the statistics are staggering—in 1968 alone, there were over 2,000 terrorist bombings in the United States. The FBI reported more than 2,500 bombings on U.S. soil between 1971 and 1972, an average of nearly five explosions per day. As Burrough put it, perhaps the only thing more startling than those numbers is how completely they have been forgotten by the American public.

If we go back even further, and if you want a really terrifying look at how political violence can consume a republic, I highly recommend Mike Duncan’s The Storm Before The Storm, about Rome and the hundred years of political dysfunction that preceded Julius Caesar. In the book (and in our podcast episode together), Duncan chronicles how the normalization of mob violence, the normalization of assassinations, people breaking the rules, politicians demonizing their opponents, politicians trying to overthrow elections, people thinking that they alone were the solution to the republic’s problems led to the republic’s fall.

So again, political violence has always been there. And it can continue to be there, if we let anger and hatred take more and more of us in their direction. We can follow Rome’s path toward the normalization of brutality, where every act of violence is met with more violence. Or we can choose to go the way Kennedy talked about that night in Indianapolis—the harder path of understanding, compassion, and the ancient wisdom that teaches us to find meaning in our suffering rather than let it consume us. We can choose, as he said, to try to tame the savageness of man.

Look, pluralism is not some nice idea. It is a technology. It was invented out of the hard-won wisdom that Aeschylus talked about, largely by the American pilgrims and then the Founders, who looked backwards at centuries of religious violence. They understood that in a winner-take-all system, people would always be fighting. But in a system that allowed for a multitude of views, for freedom of expression and protecting minority views—even abhorrent ones—where the government did not pick sides, then people of all faiths and beliefs could co-exist.

I do not mean to be kumbaya about this. I also don’t want to dance around the brutality of what happened to Charlie Kirk—a father of two was gunned down by a high-powered rifle on a college campus, bleeding out before he even knew he was dying. I also won’t refrain from denouncing the inane, trollish, and stupid positions he often espoused. Charlie Kirk was a bigot and a misogynist and a homophobe. He also celebrated and encouraged political violence—not just perpetuating the lies about the 2020 election but proudly busing hundreds of people to the Capitol on January 6th, an event that erupted into an insurrection on par with Catiline’s (which he then pleaded the Fifth about in front of Congress).

No one deserves to die. George Wallace did not deserve to be shot. Neither did Martin Luther King Jr or Robert F. Kennedy. Neither did Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Health. (I was incredibly disappointed to see that the murderer Luigi Mangione had once retweeted something I’d said. Talk about missing my message!) Assassins threaten not only individual lives but the very concept of pluralism and free expression. They steal from all of us. Because now we question what we say, we question whether our rights will be respected, we question whether this project–that is to say democracy–will keep working.

We all deserve better than the level of discourse that Charlie Kirk practiced, which was the classic toolkit and style of a demagogue, but discourse is better than murder. Virtue (and just plain human compassion) also demands better than the insensitive and cruel responses to his murder…as well as the anti-democratic and authoritarian rhetoric that politicians have thrown about after. It’s shameful what people have been doing and saying…it’s essential that each of us makes the choice to not be implicated or participate in that ugliness.

I’m reminded of a recent conversation I had with Dr. Laurie Santos on the Daily Stoic podcast. She talked about an essay by the anthropologist Sarah Hrdy, who studies primates and primate interactions. In the essay, Hrdy describes the familiar experience of being crammed on a long, delayed flight filled with dozens and dozens of strangers, all cranky, tired, hungry, and irritable. “And she’s like, ‘if this was any other species,’” Dr. Santos said, “‘they’d be killing each other. No one would leave with their testicles.’ It’s amazing that we get to be in one of the few species where all that happens is somebody says a nasty thing to the flight attendant.”

What keeps us from tearing each other apart on an airplane or in society or in the middle of intense disagreements about religion or policy or events isn’t biology. It’s the social technologies we’ve developed over the past 2,500 years. It’s the political process. It’s rules, the norms, the shared agreements about how we behave and coordinate and cooperate with each other. None of which are guaranteed or permanent or self-sustaining.

They require constant work, constant vigilance, constant choosing.

They require, as Kennedy said, that we make an effort. An effort to love, to understand, to have compassion toward one another, to treat our fellow human beings like fellow human beings.

We desperately need to make that effort. We desperately need to put the genie of political violence back in the bottle.

Because once it gets out, once that Rubicon is crossed, history shows it’s incredibly hard to tame the savageness of man.

September 10, 2025

You Must Avoid Getting Corrupted By This

I’m giving a talk in Austin next week ( only a few tickets left ) and San Diego in February. Grab seats and come see me !

My study of history has led me to believe that there is a kind of dark matter inside the human race.

It’s some combination of evil, cruelty, ignorance, cowardice, mob-ness. It is a kind of dark oppositional energy that goes from issue to issue, era to era. It’s rooted in self-interest, self-preservation, in fear, in not wanting to be inconvenienced, not wanting to change, not wanting to have to get involved. It manifests itself a thousand ways, but once you recognize it, you spot it everywhere.

It’s there in some of our oldest stories. Written in 430 BC, Euripides’ The Children of Hercules is about the plight of the refugee, and how a society is judged by how it treats the weak and vulnerable. The young children of Hercules are driven to the Temple of Apollo in Marathon by a bounty hunter from an angry king, who demands they be handed over to be punished. “They are suppliants and strangers,” the Athenians reply, “Who look to our city for help. / To reject them is to defy the gods.” But the king, obsessed with his vendetta—his goons following his orders—will risk war rather than let these vulnerable people have some measure of peace or safety.

This energy was the motive force behind s the great cruelties of history and the great backlashes too: the Inquisition, the Holocaust, the Confederacy, the exploitation of colonialism, the thwarting of Reconstruction, collaboration in Vichy France, the excesses of the Red Scare and McCarthyism, Apartheid in South Africa, the Rwandan Genocide. And it’s there in modern moments too, big and small, mundane and outrageous: the NIMBY neighbor at a city council meeting to block desperately needed housing, the bullying of librarians, the shrug at another mass shooting, the mob on Twitter gleefully destroying someone, backlash against immigrants (especially when they look different than you), now the backlash vaccines and wind energy, the endless debates (and excuses) while Gaza descends into humanitarian catastrophe.

Gandhi was once asked what worried him most. His reply? “Hardness of heart of the educated.”

When I look around right now, I think of this hardness of heart as one of the big problems of our time. And the way, in the face of it, good people can become utterly exhausted and detached, worn down by years of resisting this energy.

In my book Right Thing, Right Now, I write about Raphael Lemkin, who spent the first half of the twentieth century trying to wake the world up to the atrocities in Armenia and then in Europe.

No one listened. Even as his own family was being murdered in Poland.

So he backed up and decided to start very small. Part of the problem was that new technology had made violence possible on a scale beyond words. “As his armies advance,” Churchill said of Hitler in 1941, “whole districts are exterminated. We are in the presence of a crime without a name.”

Churchill almost always had the right words. Here, he did not.

That’s what Lemkin solved first.

Because the crime had no name, people excused it, denied it, or looked away. In 1943, Lemkin coined the word “genocide” to describe the deliberate destruction of a people. Added to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary in 1950, the word changed the moral arc of the universe.

There it was. It could not be denied.

Lemkin then fought to codify the word into law. At Nuremberg, he all but slept in the hallways as he lobbied for a UN declaration. He hounded reporters, mailed research to politicians, buttonholed diplomats, wrote op-eds. It was good trouble for a good cause. After four years of relentless work, in 1948 the UN passed a unanimous treaty banning genocide—the nameless crime that had claimed Lemkin’s mother. All he could do was weep.

But the fight was only beginning.

The United States refused to ratify the treaty for decades. In 1967, Senator William Proxmire picked up the baton. “The Senate’s failure to act has become a national shame,” he declared. “From now on I intend to speak day after day in this body to remind the Senate of our failure to act and the necessity for prompt action.”

This was not empty virtue signaling. Genocide was happening at that very moment in Nigeria. Soon it would be Bangladesh. Then Burundi. Then Cambodia. And on and on.

Proxmire’s first speech wasn’t successful. Neither was his tenth. Or his hundredth. But he refused to give in to indifference. Across two decades he gave more than three thousand speeches, patiently making trades and deals, steadily winning over the sixty-seven senators he needed.

Finally, in October 1988—twenty years after he began, forty years after Lemkin—Proxmire gave his last speech on the subject, his 3,211th. This time, he could announce victory. The treaty had passed. The world had, at last, a tool to fight humanity’s most nameless crime.

Of course, it would be wonderful if the world were naturally just, if people were automatically good. But they aren’t. It would be wonderful if this was the end of genocide, but obviously, it is isn’t. Terrible war crimes are being committed right now, not just in the Middle East but also in Ukraine and in Sudan. One of the most heartbreaking truths of life is that people not only fail to do the right thing, they often persist in error or evil even after every argument has been made, every procedure followed.

They dig in. They don’t let go.

That was the Southern strategy during segregation—make it so difficult, so painful, so nasty that the North would eventually give up, as it had after Reconstruction.

Which is why the civil rights movement was more than marches. It was endless court cases that took years to be heard, years to win, and were often ignored by Southern officials. When James Meredith sought to integrate the University of Mississippi, Justice Department lawyer John Doar filed hundreds of motions, sat before judge after judge, appealed and appealed again.

“You’ve just got to keep going back,” Doar said. It didn’t matter if an injunction went against them, if governors defied rulings, if mobs surrounded them, if no one cooperated. There was always another motion, another venue, another appeal.

The main thing was that the good guys didn’t quit. They refused to be discouraged. They believed they could—and would—prevail. They stayed with it. They just kept going back, until finally, eventually, they made the tiniest bits of progress.

And the thing about this dark energy is that once it is beaten down somewhere, it finds a new place to pop up. It’s like water: it just pools and then seeks a new outlet. After the famous Brown decision, the Southern energy went into founding Christian “segregation academies” or private white-only schools—effectively creating the Religious Right. Although many modern political issues are complex, when you zoom out, you often see how simple they are: This is somewhere that that energy has found an opportunity to go.

This is an exercise I often do. I mentally put all the specifics aside and I think: What would the people who shouted slurs at Ruby Bridges (or Ernest Green, who I’ve interviewed) as she walked into school for the first time feel about this issue? Or, what about the oligarchs who controlled the levers of power until the Civil War, then fought social reformers during the Gilded Age and then resisted the social safety net during the Great Depression and then fought tooth and nail for isolationism in the run up to WWII (and after too, which is why many senators refused to sign the UN Genocide treaty), what stance would they be drawn to here? I try to think about where the darkness would go—or how it would be rationalized—and I try to go the other way.

In his private writings, we see Marcus Aurelius doing something similar, constantly reminding himself during his own dark and ugly times: Don’t become implicated in the ugliness. Don’t let it infect you. Don’t become cynical or bitter. “Take care,” he writes in Book 7 of Meditations, “that you don’t treat inhumanity as it treats human beings.” Or to put it a more colloquial and modern way: Don’t let the sonsofbitches turn you into a sonuvabitch. Don’t let bad times make you a bad person.

I’m reminded of Montaigne, who, as we have talked about before, faced what might have been even darker times than our own: mass executions, religious wars, persecution, demagogues, bandits, riots, conflict, thousands of people burned at the stake for mostly imagined crimes. He was aghast at the way people treated each other, especially people they disagreed with or didn’t understand. Yet for all the cruelty around him, Montaigne would not be sucked in. As Stefan Zweig would write in the biography I turn to whenever the world seems dark, Montaigne remained human in an inhuman time. He would not get sucked into the dark energy. He would not let inhumanity drive him away from humanity. He would not let the sonsofbitches turn him into a sonuvabitch.

“No one can stop you from that,” Marcus writes. Because, he added. No one can make you do that. It’s a choice. There’s a fountain of goodness there inside us, inside the world. It is up to each of us to make sure that fountain keeps bubbling up. No matter how much shit and evil people try to dump on it.

Don’t let the darkness make you dark.

Don’t let inhumanity deprive you of your humanity.

Don’t equivocate. Call a spade a spade. Condemn evil, cruelty, and injustice.

And keep going back to that fountain of goodness within. As long as you keep going back, “and as long as you keep digging,” Marcus wrote, “it will keep bubbling up.”

No one can stop you from that.

September 3, 2025

The World Lost a Great Man (and my friend) But His Legacy Lives On…

When he was born, he was legally considered less than fully human.

Born in segregated Washington in 1937, George Raveling and his family were second-class citizens, denied basic rights and dignities.

And then it got worse from there. When he was nine, his father died at the age of forty-nine. His mother was committed to an asylum when he was thirteen. Effectively orphaned, this could have been another sad story from a long time ago. Instead, the life of George Raveling became something beautiful, inspiring, and almost unbelievably modern—a classic American story, equal parts Alexander Hamilton and Forrest Gump.

It started with a man named Father Jerome Nadine, a Catholic priest in Brooklyn, who loved basketball (one of his other parishioners was the Wilkens family, whose son Lenny would go on to be an NBA Champion and one of the winningest coaches of all time). He got George a spot at St. Michael’s, a boarding school in Pennsylvania for boys from broken homes, and asked the basketball coach if he could make a spot for the tall young man. Soon enough, the head coach from Saint Joseph’s College, Jack Ramsay, came to his games and told George he would be offering him a college scholarship.

George loved to tell the story of what happened when he went to his grandmother, Dear, to tell her the good news. “I thought I raised you better than that,” Dear said when George told her a college was going to pay for his education to play on their basketball team. “What do you mean?” George said. “I think you’ve done a great job.” “Well, I’m disappointed in myself,” Dear replied, “because I can’t believe that you’re naive enough to think that some white people are gonna pay for you to go to college just so you can play basketball. It makes no sense. They’re tricking you.”

At Villanova, where he did end up with a scholarship (and later a degree in Economics), George led the country in rebounds, only the second black player in the school’s history. In the days before televised basketball, it was often a shock when this integrated team showed up to play southern schools. In 1959, they drove down to Morgantown to play West Virginia. Assigned to guard Jerry West—the future NBA logo—George chased West on a fast break late in the game. When West went up for a layup, George jumped in an attempt to block the shot, colliding with West in the air and sending both of them crashing into the stands. “As we lay there tangled together,” George wrote, “the field house fell silent. I could feel the eyes of the crowd on us, could sense the anger and hostility crackling in the air. In that moment, I feared for my life. But then, something extraordinary happened.” West—“the golden boy of West Virginia, the pride of Morgantown”—got up and then reached out his hand to George. As West pulled George to his feet, the all-white silent crowd erupted into applause. After the game, West ran over as George walked off the court and grabbed him by the arm. “Good game,” West said as he shook George’s hand and looked him in the eyes. “It was a pleasure playing against you.”

After college, he spent time as a traveling assistant and bagman for Wilt Chamberlain, who was getting tons of requests to make appearances at summer camps around the east coast. “I’ll hire you to be my chauffeur,” Wilt told George one day. For a hundred dollars a day, George jumped at the chance to drive Wilt’s purple Bentley convertible from camp to camp, talking basketball and life.

Just these few anecdotes alone would have made George Raveling a living legend. But his rendezvous with history didn’t happen until August 28, 1963. Sent by the father of a friend, 6-foot-four George was recruited to work security for the March on Washington. Standing on the podium a few feet from Dr. King on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, George was one of the first people to greet him as he finished the “I Have a Dream” speech that would change the course of American politics. Accepting the congratulations, King handed George the only existing notes/text (which he had largely ignored in favor of improvisation) of one of the most famous speeches of all time. George tucked it into a book at home—a personalized copy of Truman’s autobiography, which the former president had given him his senior year at Villanova when George played in the East-West All-Star game in Kansas City. There it would sit, safely preserved, for the next few decades until journalists got around to figuring out what had happened to it.

It is a shame that George Raveling’s coaching career is not more well known. He was a great and pioneering one. While an assistant at Villanova, he started recruiting players from the South who, up to that point, were only looked at by historically Black colleges and universities. Players like Johnny Jones and Howard Porter became part of what one sportswriter dubbed “the Underground Railroad,” George’s trailblazing pipeline bringing Southern talent to a predominantly white Northern school. He would later become the first African American basketball coach in what’s now the Pac-12 and went on to go 335-293 over his career, leading programs at Washington State, the University of Iowa, and USC. He won 2 Olympic medals, a gold in 1984 and a bronze in 1988. He coached against John Wooden, Dean Smith, and Bob Knight. He earned his Hall of Fame induction as an X and O’s guy, a recruiter and as a leader of young men to victory.

Of course, we remember him most for his contributions to the game slightly off the court. It was George Raveling who, as an assistant coach for the 1984 Olympic Team, steered Michael Jordan to Nike and changed the economics of sports and entertainment and fashion. You might not know this from the movie Air, which is largely about Sonny Vaccaro, but Michael Jordan knows the truth and has always and repeatedly credited Raveling. Ben Affleck tells the story of meeting with Jordan to get his blessing to make Air. Jordan gave the go-ahead, but with two conditions: Viola Davis had to play his mom, and George Raveling had to be in the story. He released a statement this morning after the news of George’s death, thanking him for his decades of friendship and mentorship. “I signed with Nike because of George,” he said of his most famous and consequential business decision, “and without him, there would be no Air Jordan.”

And then there is what George did while he was at Nike. After a twenty-two-year career, he retired from coaching in 1994, and at the age of sixty-two joined Nike as their director of international basketball. He traveled around the world to countries where basketball was a little-known sport, where resources were limited, good coaching was scarce, and talented players had no exposure to college or professional scouts. In an attempt to fix that, in 1995, George developed the Nike Hoop Summit, an annual all-star game featuring the top young players from around the world. Since the inaugural event, to this day, the Hoop Summit has launched the careers of countless international stars: Dirk Nowitzki (Germany), Tony Parker (France), Enes Kanter (Turkey), Luol Deng (South Sudan), Serge Ibaka (Republic of the Congo), Nikola Jokić (Serbia), and most recently, Victor Wembanyama (France).

I, myself, met George in 2015 at a University of Texas Basketball practice. I thought I was just shaking hands with a friendly older gentleman. I did not know that day that I was shaking hands with history–a hand that had in turn shaken hands with Presidents Truman and Ford and Carter and Reagan and Clinton and had held the “Dream” speech.

I liked to say that George was my oldest friend, but that was literally not true, since he and I once went and sat on the porch with Richard Overton, then literally the oldest man in the world at 111. Most of the time, George felt like one of the youngest. Not only was he an avid texter, but he loved to email articles that he read from his iPad on topics as diverse as mastermind groups and AI, leadership principles and personal habits, philosophy, politics, time management, parenting, public speaking, storytelling, and on and on. For someone who taught so many people—regularly taking calls from John Calipari, Shaka Smart, and Buzz Williams—he was always quick to call me his mentor. I didn’t know quite what to make of the compliment, finding it both extremely complimentary but obviously absurd. In time, I have come to see it as just another lesson: We’re never too old to learn and the wisest people remain students all their lives, learning from everyone they can find, including, apparently, people a fraction of our age.

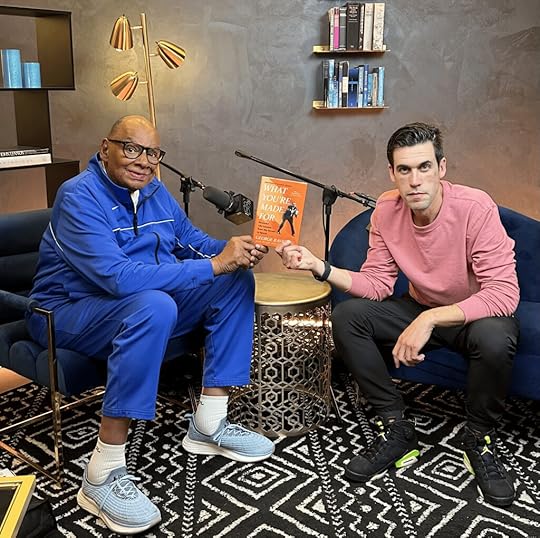

I’m not sure there was a bigger supporter of bookstores than Coach Raveling, who rarely arrived at a meal without books as gifts. He would send me pictures from his weekly trips to Barnes and Noble, whenever he saw any of my books. It was one of the honors of my life to help him fulfill a lifelong dream of writing his own book, What You’re Made For, which he lived long enough to see in stores.

What You’re Made For by George Raveling

What You’re Made For by George Raveling

My only sadness about my time with George is that he had to cancel a book signing he was going to do at my bookstore, The Painted Porch, for health reasons back in May. I was sad not to see him obviously, but mostly sad that he seemed to take needing to cancel something so hard. He was not used to accepting limitations–he had been defying them all his life.

There was not a major figure you could name in the 20th century and not get a story from George about them. I asked him, after Jimmy Carter died, if he ever met him, and he told me about a trip in 1981 to the People’s Republic of China. George was there leading a coaching clinic for 200 Chinese coaches. The clinic was held in Shanghai, and one night he was asked to move out of his hotel room because, he was told, President Carter had unexpectedly arrived at the same hotel and the Secret Service asked that the rooms above, below, and adjacent to Carter’s suite be empty. Despite the inconvenience, George said it turned out to be the highlight of the trip—Carter invited George to have dinner with him to make up for the disruption.

I asked him if he knew John Wooden and he told me not just of coaching against him and their breakfasts together, but that in his coaching column for The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, George had broken the story of Wooden’s retirement after 27 years at UCLA. He told me stories about Kareem and Chamberlain and Sammy Davis Jr. and Kobe Bryant and Bill Russell and Charles Barkley and Bill Walton and of course Truman and Jordan and Phil Knight and his beloved grandmother, Dear. Who would have guessed that that lonely little boy living on the corner of New Jersey and Florida Avenues in Depression-era Washington would have intersected with so many fascinating people?

A life like George’s could have hardened a person, necessitating a narcissism and self-absorption in order to survive in a cut-throat, fast-paced world. I’m sure he was a hard-ass as a coach (one of Michael Jordan’s children told me with a twinkle that although everyone saw George as a kindly old man, he had seen him yell at people). I remember being cc’d on an email about a negotiation George was in and when he didn’t like the terms was blunt and forceful about shutting the whole project down. He was not going to be taken advantage of. It gave me a sense of the strong and savvy coach and executive who had broken down so many barriers and carved out a space for himself—as well as for others as a founding member of the Black Coaches Association.

But for the most part, he was one of the kindest and calmest and supportive people I have ever known. When we would do our calls for the book, it caught me off guard at first. George, before hanging up, would say, “I love you.” I’m not used to that—at least not from people outside my family. But George never hesitated. “I’ve learned that it’s hard for people, especially men, to say ‘I love you,’” he told me. Even with his own son, he noticed that for years it felt uncomfortable for him to say it back. “It’s strange,” George said, “because every one of us has a thirst to be loved, appreciated, acknowledged, respected. And yet, for some reason, we struggle to express it.” So George has made a habit of saying things like, “I appreciate you.” “I respect you.” “I’m glad you’re my friend.” “I’m here for you.” Simple words that so many people rarely hear.

George told me that when he had heard that Jerry West, his friend of 65 years, had died, he found himself shouting, “Oh no, oh no!” When I got a text on Monday night that George had passed, I had a similar reaction. George told me the last text he had sent Jerry was, “I think of you every single day with love in my heart and best wishes for good health and stability. I miss your presence, wisdom, and leadership. Hope to see you soon, my friend. God bless you and your family.” I went back through mine and found a few—a meme he’d sent me about the new pope, an article he thought I should read, a message I had passed along from RC Buford, the CEO of the San Antonio Spurs who had just purchased signed copies of George’s book for a bunch of people in their organization, including all their players.

Of course, no one is totally surprised when someone dies at the age of 88. And I know George wouldn’t have been either. In one of my favorite passages in his book, George writes about thinking of his life as a basketball game in its final quarter, with just a few minutes left on the clock. “For me,” George writes, “I know what time it is…which is to say, near the end. There’s no way around that. In fact, at my age I’m closer to something like double overtime or extra innings.” He lived accordingly–which is to say gratefully–and tried never to leave anything undone or unsaid.

In July, I had checked in on how he was feeling. He replied:

It’s been a marvelous 88 years(6/27/37) on planet Earth!! You changed my life forever!! Each day I’m in search of strategies that will allow me to Grow personally and professionally!! thanks for believing in me!!!! thanks for investing in me!! God bless you and your family!

I told him I loved him and I missed him.

It’s true.

We all did and do.

***

—Today’s newsletter is sponsored by Shortform

Add Shortform to your ToolkitTime is the ultimate constraint to productivity and learning, it is always ticking away. So when there are tools that optimize your time, make sure and keep them in your tool kit. One of those indispensable tools is Shortform.

Shortform is a nonfiction book summary service that has truly raised the bar in its domain. Shortform distills each book’s core ideas with chapter breakdowns, analysis, commentary, and even counterpoints from other sources, allowing you to deepen your understanding, fast.

They even have all of Ryan’s books on Stoicism!

Ryan’s readers get a free trial and 20% discount on the annual subscription.

August 29, 2025

Why I Ran A Solo Race From Marathon To Athens (And What It Taught Me)

I remember exactly where I was.

Twenty years ago, I was working in Hollywood. On my lunch break, I was at Philly’s Pizza on La Cienega and Olympic, reading The 33 Strategies of War by Robert Greene. In a chapter about the “divide-and-conquer” strategy, Robert writes about the Athenians’ legendary stand against a massive Persian invasion on the plains of Marathon in 490 B.C. After the battle in Marathon, the soldiers had to immediately race back to Athens where a second Persian fleet was on its way to take the city from the sea.

“There was simply no time to rest,” Robert writes. “They ran, as fast as their feet could take them, loaded down in their heavy armor, impelled by the thought of the imminent dangers facing their families and fellow citizens…Within a matter of minutes after their arrival, the Persian fleet sailed into the bay to see a most unwelcome sight: thousands of Athenian soldiers, caked in dust and blood, standing shoulder to shoulder to fight the landing. The Persians rode at anchor for a few hours, then headed out to sea, returning home. Athens was saved.”

Had the tired, dusty soldiers not run from Marathon to Athens, Robert writes, “history would have been altered irrevocably,” as the Persians, in conquering Greece, would have crushed the Athenians’ nascent democratic experiment that went on to shape the western world. Perhaps there would be no such thing as Western civilization.

I had previously read about the Battle of Marathon in Herodotus’ Histories but this was so much more vivid, I actually understood what was happening and why it mattered. There in the pizza shop, I was struck by the way the same historical event could be transformed in the hands of a different storyteller. I remember being struck in particular by Robert’s line, “caked in dust and blood.”

In any case, I emailed Robert and asked what he read when he was researching this famous event. He told me his sources, which included a book called The Greco-Persian Wars by Peter Green. I immediately ordered it on Amazon, and a few days later (Amazon was a little slower then), I began to read it on my lunch break.

The screenwriter and director Brian Koppelman (Billions, Rounders, Ocean’s Thirteen) talks about “The Moment”—the critical moment in every aspiring artist’s life, when the craft they have long elevated as magic or beyond their grasp suddenly becomes a bit more comprehensible.

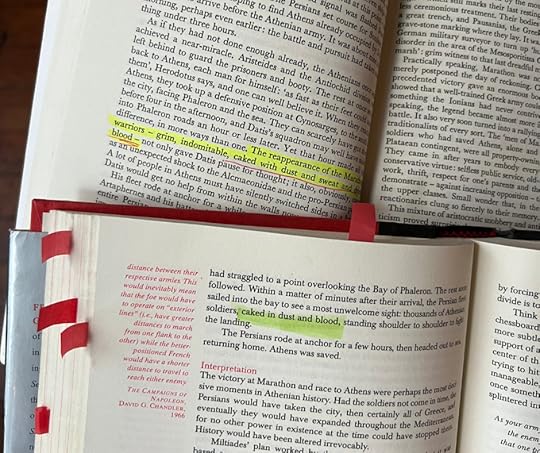

My moment happened about forty pages into The Greco-Persian Wars, where Peter Green writes, “The reappearance of the Marathon warriors — grim, indomitable, caked with dust and sweat and dried blood — not only gave Datis pause for thought; it also, obviously, came as an unexpected shock to the Alcmaeonidae and the pro-Persian party.” It was here that I realized: Oh, this is how it works. This is what a researcher, a writer, a storyteller does: they read a collection of books on the same event, filtering the many details through their own lens based on their own tastes, which they then shape into their own style to make something new.

The passage from The Greco-Persian Wars (top) that Robert Greene used in The 33 Strategies of War (bottom).

It was a breakthrough moment for me. A little peek behind the curtain of the previously intimidating craft that I was drawn towards. A realization that on the other side of the books I admire and love is just another human being doing a job. And I’m a human being too, so maybe if I work hard enough, I can write books too.

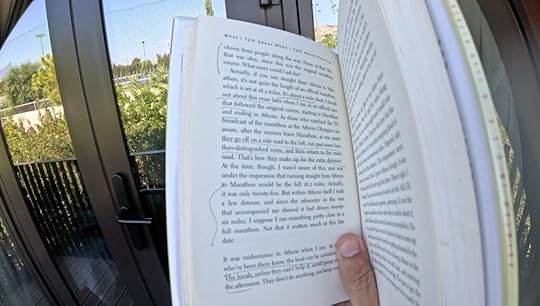

Now, there was nothing in either of the Green(e) books about the fact that one could still go to Greece and run the course the Athenian soldiers, caked in dust and blood, ran from Marathon to Athens. But not long after, I read what became another all-time favorite book, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which Haruki Murakami writes about running “the original marathon course” all alone, not as part of “an official race.”

Re-reading “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running”

I had been a runner for a long time, and the one thing you get asked all the time as a runner is, “Are you training for a marathon?” My answer was always, “No, this is the marathon.” That is, the day-to-dayness, the doing it for no reason other than because, is the real challenge I’m tackling.

That’s how I thought about running basically from the moment I left organized sports as a kid. It’s, as Murakami talks about in one of my favorite passages in What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, both exercise and a metaphor. “Running day after day,” he writes, “bit by bit I raise the bar, and by clearing each level I elevate myself. At least that’s why I’ve put in the effort day after day: to raise my own level. I’m no great runner, by any means. I’m at an ordinary—or perhaps more like mediocre—level. But that’s not the point. The point is whether or not I improved over yesterday. In long-distance running the only opponent you have to beat is yourself, the way you used to be.”

Combined with my longtime fascination with the way that ancient, original Marathon tipped the balance of history, Murakami’s quiet account of running it alone—not for a medal or a crowd, but simply to raise his own level—planted the idea of one day running it myself. It had been sitting in my mind for some fifteen years when my wife and I started planning a trip to Greece with our two boys this past summer.

Along with bringing to life the places I’ve been reading about for years and years—Olympia, Ithaca, Delphi, Thermopylae, Mt. Olympus and more—finally, I was going to try to run from Marathon to Athens.

After looking at a lot of the marathon training regimens out there, I didn’t have to change much. (Which was my point all along: If you stay ready, you don’t have to get ready). The only real shift was being more deliberate than usual about running in as many different environments and conditions as possible.

I went for long runs up switchbacks in Palm Springs, along the Santa Ana River in California, on mountain trails in Utah (where I was warned to look out for a very protective mother moose and her two calves) and as I often do, around Lady Bird Lake in Austin, and through the eerie elephant graveyard of the burned-out forest of Bastrop State Park.

Training in Sundance, UT

I ran in 105-degree heat. I ran on steep inclines. I ran before dawn, at altitude, on cement, gravel, sand. And once we got to Greece, I trained at the Acropolis. I trained in Ithaca. I trained running up Mount Olympus. I went on hikes with my family. I swam in the Aegean Sea. As Epictetus says, the goal when we come up against adversity—as I knew I often would during the long, hot, solitary run from Marathon to Athens—is to be able to say, “This is what I’ve trained for, for this is my discipline.”

Training in Greece

Swimming in Greece

At 6:51 a.m. on July 13, I stood at the starting point of the original Marathon route. I wasn’t nervous. And I was nervous about not being nervous. But the stillness came from training. I had done the work.

It was not the prettiest of courses, and I was the only one out there. I ran on sidewalks. I ran on the shoulder of busy roads. I ran along shopping centers and autobody shops. I ran on the side of a freeway and through underpasses. There was a brief period where you had a peek at the ocean, but most of it was industrial and gritty. It was entirely asphalt excepting a few brief moments of rocks by the side of the road.

Three and a half miles in, I came to the ruins Murakami writes about in What I Talk About When I Talk About Running,

“As those who watched the TV broadcast of the marathon at the Athens Olympics are aware, after the runners leave Marathon, at one point they go off on a side road to the left, run past some less-than-distinguished ruins, and then return to the main road.”

It is perhaps the only part of the book I disagree with. I wouldn’t say they are “less-than-distinguished” ruins. I would say they are some of the most impressive and meaningful ruins in the entire world. I was incredibly struck by them. In particular, I was struck by a giant mound surrounded by trees—the burial mound of the 192 Athenians who died at Marathon, to whom we owe basically all of Western civilization. Theirs was not to reason why, Tennyson famously wrote about another group of soldiers on an impossible mission. Theirs was but to do and die. Or as the Spartan monument says, tell a stranger passing by that here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

In part, Stoicism itself, the philosophy that I am lucky enough to write about, is rooted in the epic heroism of those Athenian soldiers. Not just because they saved Greek civilization, but because they were held up by the early Stoics as models of the four virtues—courage, discipline, justice, and wisdom—that they themselves strived to live up to. The Stoa Poikile—literally the “Painted Porch”—where Stoicism was founded, earned its name not because the porch itself was painted, but because a series of famous paintings lined its walls.

We’re told by ancient historians that of all the “great deeds” depicted in the Stoa Poikile, none was more prominently displayed than the Battle of Marathon. One 1st-century B.C. writer writes that the Athenian general Miltiades “was given a special honor…When the battle of Marathon was painted, his picture was placed first among the ten generals, and he was shown urging on his men and joining battle.” Again, this wasn’t just a 26-odd-mile run for those soldiers sweltering under armor, caked in dust and blood. It was an existential fight. The fate of Greece—and with it, the future of the world—was on the line. The sheer bravery and strength of those Athenians, covering the very distance I was now running, powered me through the next seven or eight miles.

A little over halfway in, I was still feeling good. And I found myself thinking about what the Stoics say about undergoing a hard winter’s training: we train, we do hard things, we challenge ourselves—physically, mentally, spiritually—so that when life throws its own challenges at us, we have something to draw on. We have proof. Evidence that we are someone who can do hard things. Someone who can keep going. Someone who has done the training.

25 km into the run

But then I entered what Courtney Dauwalter, one of the great ultramarathoners of all time, calls the “pain cave”—where you hit the edge of your mental and physical limits. When I interviewed Courtney on the Daily Stoic podcast, she talked about how she gets excited when she reaches her pain cave during a long run. Instead of thinking about the pain and discomfort, she thinks about exploring how far back the cave goes, what’s inside it, how she might chip away at the back wall to push it just a little farther away for next time.

With about 3 miles left, I was as deep in that cave as I think I’ve ever been as a runner. It was 90 degrees now and it didn’t matter how much water I drank, I could not get hydrated. I had trouble reading the map on my phone, my brain basically wasn’t working. It’s clear afterwards that I had sunstroke or was in the early stages of it. Whatever time I was hoping for fell away, and it was really just whether I was going to continue or not. Epictetus talked about only entering competitions where winning is up to you. I tried to remind myself that I was not doing this for an outcome. There was no time or goal I was chasing. Doing this thing I had never done before, elevating myself, raising my own level—that was the real competition. And winning it was up to me. As long as I don’t quit, I thought, I’ll probably make it to the other side.

I would have loved to have finished stronger, but I ran into a complete wall. There wasn’t much I could do—physically or mentally. Both my mind and body were begging to quit. I thought of the Kipling lines in If—

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on”

I held on. I didn’t quit. I gutted it out. I finished.

After finishing, I was wrecked. The story about Pheidippides is that when he finished the journey back to Athens, he delivered his message and then immediately died. I didn’t exactly do that, but I did throw up in one of the oldest and most beautiful stadiums in the world. I threw up before the long drive back to my hotel. And when I got to the hotel, I threw up several more times. I couldn’t keep down even water.

In the days after the run, once I was somewhat back in command of my faculties, I thought about what I could have done better. I could have managed the nutrition side of things better. I could have started a little bit earlier so that I could have finished before it got as hot as it did on the final miles.

In a word, I could have been wiser. Obviously, discipline is incredibly important, but without the virtue of wisdom—understanding the right place to apply that discipline and how to support that discipline—you can get yourself in some very rough spots. And so discipline is something we have to moderate with wisdom. The wisdom of, What is the best plan? What is the best nutrition? How do you not get wrecked by the heat? How do you take care of your body?

Seneca talked about how the only people he pitied were those who hadn’t been through adversity or experienced difficulty. Because they will never know what they’re capable of.

What I took most of all from running the Marathon is that I am a person who is capable of doing hard things. I know that because I did a hard fucking thing.

And I take that with me.

August 20, 2025

You Can Choose To Be Great, But Not What You’re Great At

I think it’s safe to say that no one is great at anything by accident.

So in one sense, greatness is a choice.

We choose to be great.

You get to decide, ‘I’m going to take this craft, sport, talent, profession, discipline, genre, or subject as far as I am capable of taking it.’

That’s up to you.

But on the other hand, I don’t know if you get to choose what you’re great at. I don’t want to be too mystical about it, but I think what we get called to do is a confluence of circumstances that are not up to us. When we’re born—not up to us. Where we’re born—not up to us. If we’re male or female, short or tall, from a rich family or a poor one—not up to us. Why does this light me up and that lights you up? Why does math come easy to some but not to others? Why does this genre of music grab you instead of that one? Why is it writing for me and picking stocks for you? Teaching yoga for one person, teaching chemistry for another?

I don’t know, but I don’t think it is up to us.

There is something a little bit unfair about this. I think about this with my friend Paul Rabil, who I got to work with on his book The Way of the Champion. Paul is considered the greatest lacrosse player of all time. He chose to be great. In the book, he talks about a coach who told him the key to being a great lacrosse player was simple: take one hundred shots a day. If you get one hundred reps a day, every day, eventually, you’ll get an offer to play D1 lacrosse. He promised them.

And you know what, that’s exactly what Paul did, getting a full scholarship to play at Johns Hopkins and winning two national championships and All-America honors all four years. But it wasn’t all sunshine and roses. His calling for the game was actually a kind of curse. Because even though it’s one of the oldest sports in history, lacrosse is a fringe sport to say the least, so when Rabil got drafted to the pros first overall, it didn’t mean making millions of dollars, signing big endorsement deals, or playing before huge crowds and national TV audiences the way it does in some professional sports. No, his rookie wage was $6,000 a year. Games were played in small high school and college stadiums, often with just a few dozen fans in the stands. And there were no national TV broadcasts, just the occasional grainy webstream on some little-known site tucked in the corners of the internet.

He was the LeBron James of a sport for which transcendent greatness meant relative obscurity, as it continues to mean for the best lacrosse players in the world.

More recently, I had a great conversation with Candace Parker on the Daily Stoic podcast. She is also one of the greatest to ever play her sport. She played for the University of Tennessee under Pat Summit, where they won two NCAA championships in 2007. In 2008, she was drafted number one overall in the WNBA. She was the Rookie of the Year and the MVP in her first season. She’s won two gold medals and her jersey is being retired this year by two separate teams. Yet, there are far fewer accomplished NBA players—maybe even basketball players who play overseas—that you’ve never heard of that make more money in a season than she did throughout her entire career.

Is that fair? I don’t know if fair is the right word. It’s just what it is. And what it’s always been. Jim Thorpe, one of the greatest athletes of all time, got to choose to be great, but he didn’t get to choose that he was born in 1887. He didn’t get to choose that he lived decades before sports became big business. He didn’t get to choose that professional football players of his time made less than the average college football player makes today.

It isn’t only athletes in less popular sports or from bygone times, of course, who can be world-class yet poorly paid or recognized. The best middle school teachers. The world’s leading experts on this niche topic. The once-in-a-generation talent at that obscure skill. The woman at the daycare I used to send my son to who could put thirty toddlers down for a nap at once, when I struggled to do it with just one. The list could go on and on. There are so many people out there who are utterly extraordinary at what they do, but whose greatness—for one reason or another—doesn’t translate into mass appeal, doesn’t command high compensation, doesn’t receive the recognition it deserves.

I think about this with myself. I write books about Stoicism. If I wrote about something with more mass appeal or if I wrote romance novels or if I ghostwrote celebrity memoirs, maybe I would sell more books, make more money, or be known by more people.

Now, you might say, oh, why don’t you just switch to one of those things? Well, that’s the whole dilemma, right? Paul Rabil and Jim Thorpe could have switched to other professions, maybe. But Candace Parker can’t switch to the NBA. I have written books about other things, but I can tell you, it’s just not what lights me up. It’s not what gets me excited. It’s not what I feel called to try to be great at. Maybe if I had been involved in the design process, I would have chosen to be lit up by something else. But they didn’t consult me. It wasn’t up to me that writing about an obscure school of philosophy is what I find endlessly fascinating.

What is up to me is whether I choose to take it as far as I am capable of taking it.

And this is no small thing. I would actually argue there is a moral imperative to take your talents as far as they can go—irrespective of what the market says about them. After Rabil took his talents as far as they could go—multiple championships and MVP awards, two gold medals with Team USA, 10 All-Star teams, and the all-time record for career points in professional lacrosse—in 2018, he founded the Premier Lacrosse League, a pro league that rivaled and then overtook the 20-year incumbent. The PLL today has a major media rights deal with ESPN, pays its athletes full-time salaries with equity, and includes investors like The Chernin Group, the Raine Group, billionaire Joseph Tsai, NBA star Kevin Durant, and many others.