34 Lessons From Writing Every Day for Two Decades

I remember driving home from my high school graduation, excited. I was excited not because I was done with school but because of what I was about to start. I’d been working with a friend to put up my first website.

I was going to be a writer.

I’m sure whatever I wrote that day was terrible but that’s sort of the point. It was the first of many, many days. Two decades of days, in fact. I have been writing almost every day for twenty years. How many millions of words is that? I don’t know.

The published output is pretty decent: sixteen books under my own name. Another half dozen or so ghostwritten. One of them was optioned to be a movie starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, directed by Gus Van Sant (if it ever happens…) Ten million copies sold. Articles in the New York Times, Forbes, USA Today, and Thought Catalogue.

But mostly, I can feel it. I feel like I am just starting to hit my stride, just starting to get the hang of it. If you told me twenty years ago that that’s how long real confidence would take, I don’t know if I could have handled it. Still, I stayed at it and here we are…and I’ve learned a few things along the way, both about craft and about life (the two are more related than you think).

So that’s what I wanted to share today…

– I am very ambitious as a writer. I no longer have any ambitions as an author. I’m not aiming at lists. I don’t think about deals. I rarely even look at sales numbers. I have stopped tracking how other people’s books are doing. What I’m saying is that I have locked into process and tuned out publishing. The funny thing is that my results have gotten better the more I have flipped this ratio. I have also gotten much more content.

– Related…I once read a letter where Cheryl Strayed kindly pointed out to a young writer the distinction between writing and publishing. Her implication was that we focus too much on the latter and not enough on the former. It’s true for most things. Amateurs focus on outcomes more than process. The more professional you get, the less you care about results. It seems paradoxical but it’s true. You still get results, but that’s because you know that the systems and processes are reliable. You trust them with your life.

– And if you’re doing what you’re doing for external rewards, god help you. A Confederacy of Dunces was rejected by publishers. After the author’s suicide, it won the Pulitzer. People don’t know shit. YOU know. So love it while you’re doing it. Success can only be extra.

– Speaking of which, that distinction between amateur and professional is an essential piece of advice I have gotten, first from Steven Pressfield’s writings and then by getting to know him over the years. There are professional habits and amateur ones. Which are you practicing? Is this a pro or an amateur move? Ask yourself that. Constantly. – Professionals work. Amateurs talk a lot about tools. Software does not make you a better writer. If classics were created with quill and ink, you’ll probably be fine with a Word Document. Or a blank piece of paper. Don’t let technology distract you. Helen Simpson has “Faire et se taire” from Flaubert on a Post-it near her desk, which she translates as “Shut up and get on with it.”

– Don’t get caught up trying to please everyone all the time. No one who has ever created anything has escaped criticism. It’s inevitable that some percentage of people will not like what you do. You’ll drive yourself crazy if you think you’re somehow the exception to this. Just stay true to your work and who you are and don’t be too attached to your reputation.

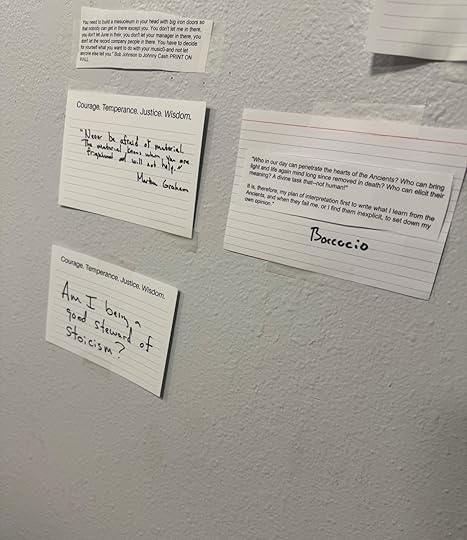

– I’m not sure where I stole the idea from, but I am a big proponent of printing out and putting up good advice and quotes. What goes up on the wall next to where I work can change project to project, but right now, I have a quote from Martha Graham: “Never be afraid of the material. The material knows when you are frightened and will not help.” One from Boccaccio: “Who in our day can penetrate the hearts of the Ancients? Who can bring light and life again minds long since removed in death? Who can elicit their meaning? A divine task that–not human! It is, therefore, my plan of interpretation first to write what I learn from the Ancients, and when they fail me, or I find them inexplicit, to set down my own opinion.” And one from Bob Johnson to Johnny Cash: “You need to build a mausoleum in your head with big iron doors so that nobody can get in there except you. You don’t let me in there, you don’t let June in there, you don’t let your manager in there, you don’t let the record company people in there. You have to decide for yourself what you want to do with your music and not let anyone else tell you.”

– The novelist Philipp Meyer (whose book The Son is an incredible read) told me on the podcast, “You have to be very careful about to what (and to whom) you’re giving the best part of your day.” I fiercely protect my mornings—family first, then writing. My assistant knows not to schedule anything before mid-morning because early calls and meetings don’t just take time—they sap the energy needed for the essential work.

– Writing Trust Me, I’m Lying, I was 90% conscious about what other people might think and 10% following what was in my heart as an artist. The book I am most proud of is my book Conspiracy. The only parts of it I wish I could do differently are the few instances that, in retrospect, I was too conscious of what other people might think (particularly journalists). I’ve flipped the ratio by this point, but I wish I had gotten to that happier place sooner.

– When The Obstacle Is the Way came out, it did okay, but I was already deep into working on what would become Ego Is the Enemy. About a year later, Obstacle really took off—teams like the New England Patriots were reading it, and there was a big article that fueled sales. But by then, I didn’t care as much because I was focused on the next book. I accidentally stumbled into a process that protected me from both disappointment and ego—I was too focused on the next thing to get caught up in good or bad news. Now I always try to start the next project before the last one launches, even arranging my schedule so I’m working the day sales numbers come in, to avoid getting caught up in those ups and downs.

– When I look back on my own writing, the stuff that makes me cringe isn’t necessarily even stuff I was wrong about. What disturbs me is the certainty. I thought I knew, but I didn’t really know. I wasn’t even close to knowing. Ego never ages well, even if it was correct in a narrow instance. My books have gotten longer as I’ve gone on. I don’t think I’m being self-indulgent, I think I am being more fair, more compassionate, more truthful.

– I’ve heard this many times from many different writers over the years (Neil Strauss being one), but as time passes the truth of it becomes more and more clear, and not just in writing: When someone tells you something is wrong, they’re almost always right. When someone tells you how to fix it, they’re almost always wrong.

– Along those lines…I wanted Trust Me, I’m Lying to be titled Confessions of a Media Manipulator. I also should have stuck to my guns about the prologue of Ego is the Enemy (I didn’t want to be in it, they wanted me in it). In creative disputes, the publisher/studio/investors/etc. are not always wrong, but often they are. And even when they’re not, you have to remember that whatever the decision, you have to live with it in a way they do not. I’ve regretted every time I did not go with what was in my heart as an artist.

– Writing is a byproduct of hours and hours of reading, researching, thinking and making my notecards. When a day’s writing goes well, it’s got little to do with that day at all. It’s actually a lagging indicator of hours and hours spent researching and thinking. Every passage and page has a prologue titled Preparation.

– As I was writing The Daily Stoic, I got into it and decided I would just keep going. That’s what started The Daily Stoic email. I’ve written and sent out a meditation on Stoicism every day since—I’d estimate that’s 1,500,000 words? It might seem like a lot of work to write and put out an email every day for almost nine years…and it is! But it’s also one of my favorite things to do, and it has made me so much better. Committing to this has been a forcing function for my productivity. We all need reps. If I only published books, I wouldn’t get nearly as many reps as I have gotten from publishing these daily emails–each one making me a little better at my craft.

– When Winston Churchill was driven from power, he could have wallowed or retired. Instead, he became a one-man media company—publishing 11 books, 400 articles, and giving 350 speeches between 1931 and 1939. He became more famous in the U.S. than in Britain, delivering his message without intermediation. They tried to cancel him, but it didn’t work. That’s what I’ve built with The Daily Stoic. It’s not just an email list but also a YouTube Channel with 2M subscribers, an Instagram account with 3.4M followers, a Twitter account with 600K followers, a TikTok page with 800K followers, and a Facebook page with 1M followers. It’s Stoicism directly to the people.

– I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought of a great line or solved an intractable writing problem while running or swimming. Exercise is also an easy win every day. Writing can go poorly, but going on a run always goes well.

– James Altucher has a great rule that I have stolen: write what you’re afraid to say. If your stuff isn’t scaring you, you’re not pushing yourself enough.

– The guy that spoke before Lincoln at Gettysburg went on for about two hours—his speech was 13,607 words long. Lincoln got up and spoke just 271 words. Think about how short Meditations is. Think about Seneca’s best quotes, how boiled-down and blunt they are. Real insight does not take many words to express. (More on this idea in Gary Willis’ incredible book Lincoln at Gettysburg).

– Near the end of his presidency, Eisenhower asked speechwriter James C. Humes to draft an address. After submitting a draft, Humes was called to Eisenhower’s office to discuss. “What’s the QED of this speech?” Eisenhower asked. Humes was confused. “QED,” he said, “what’s that?” “Quod Erat Demonstrandum,” Eisenhower barked. “Don’t you remember your geometry? What’s the bottom line? In one sentence!” Eisenhower was a brilliant man, but a simple and straightforward one after years in the Army. He had no patience for rambling. This is a good lesson for anyone and everyone when it comes to communication. Don’t dress things up more than they need to be. Don’t hedge. Don’t distract. Speak plainly. Make your point.

– Precisely zero of my sixteen books were immediately accepted by my publisher—and they were right to kick them back at me. In being forced to go back to the manuscript, I got the books to where they needed to be. Hemingway once said that “the first draft of anything is shit,” and he’s right (I actually have that on my wall as a reminder).

– Don’t talk about projects until you’re finished. Save that carrot for the end. Talking and doing fight for the same resources.

– My editor Niki Papadopoulos once told me, “It’s not what a book is. It’s what a book does.” This is why musicians follow the “car test” (how does the song sound in a car driving down the highway). It’s not about whether you like it…but about what it does for the people buying it.

– Vivian Gornick said, “What happened to the writer is not what matters; what matters is the large sense that the writer is able to make of what happened.” As Robert Greene once told me, it’s all material. If you start asking more often, “How can I use this to my advantage?”—your creative output will not only get better, your life will too.

– Speaking of Robert…I’ve talked before about my notecard system—the process I use to research and write my books, which I learned from Robert. As he says, “A lot of books fail because the writer loses control of the research. You are either a master of the material or it’s the master of you.” That’s true beyond books: You either master your to-do list or the day masters you. You either set clear priorities or get lost in trivial tasks. You either build systems or get overwhelmed by chaos.

– A formative lesson for me when I was Robert’s research assistant came when he sent me off to find stories for his writing. I’d spend weeks gathering material and bring back options I thought might work. At one point, looking over what I’d found, he said something like, “Ryan, all your stories are from nineteenth-century white guys. That’s not going to work.” He wanted diversity in his examples—not just so every reader would feel included, but because a book on the laws of power or mastery or human nature would be incomplete if it only drew on white men from the nineteenth-century.

– One more from Robert. He once told me a book needs to be either extremely entertaining or extremely practical—most fail because they fall somewhere in between. He taught me to ask: What role does this book play in someone’s life? Does it justify its cost to the reader? Readers are customers, and many authors forget that, thinking readers are just lucky for whatever the artist creates. Robert helped me see that a book has to do a job.

– My research assistant Billy Oppenheimer recently reminded me of a time I once called him about some piece he was working on, and said, “You know the ‘go for the throat’ story in Courage Is Calling?” (Early in the Korean War, with U.S. forces trapped and the enemy advancing, General MacArthur strode to the blackboard, circled the point of attack, and said, “That’s where we should land…go for the throat.”) “That should be your motto,” I said, “write it down. Don’t spin your wheels or backstory your way into the story—grab the reader by the collar and rip them immediately into the story.

– For a long time, my writing habit was all-or-nothing—either I wrote a lot of words or I didn’t. Over time, I’ve lowered the stakes: now the question is simple: “Did I make a positive contribution to my writing today?” Sometimes that means writing, sometimes editing, adding, deleting. Sometimes I’m home and it’s in my office, sometimes I’m on the road and it’s on a plane or in a hotel room. Sometimes it’s a big contribution, sometimes it’s a little contribution. The line from Zeno was that big things are realized by small steps. That’s what I try to remind myself: every day, just make a positive contribution.

– Related…I once asked one of my favorite writers, Rich Cohen, about how he’s able to be so consistently productive at such a high level. He said he approaches a big project like he approaches a cross-country road trip. “The way you deal with long road trips is you set yourself a minimum number of hours a day, no matter how you feel.” The point is that “not much” adds up if you do it a lot.

– Counterprogramming is key. Writing The Obstacle Is the Way and later launching The Daily Stoic might have seemed crazy. Not just to me—everyone said so. Who was going to care about some obscure ancient philosophy? The world wasn’t exactly clamoring for books or daily content about Stoicism. But that’s exactly why it worked. It was crazy because no one else was doing it. It was different. It stood out.

– The best way to market your writing is to write the marketing into the writing. My explicit mission with Trust Me, I’m Lying was to write an exposé of the media system that would shock and appall anyone who followed the news or worked in marketing world. The book was written to provoke, to challenge, to make people uncomfortable enough that they would talk about it. As Elizabeth Wurtzel put it, “Either you’re controversial, or nothing at all is happening.”

– Nothing is so good that it just finds its audience. You have to bring it to them. As literary agent Byrd Leavell puts it to his clients: “You know what happens if your book gets published and you don’t have any way of getting attention for it? No one buys it.” Plenty of artists can make great work. Not everyone has the dedication to make great work and market it. Marketing is where you distinguish yourself and beat out the talent whose entitlement or laziness holds them back.

– Most of all, I’ve learned to enjoy the work. A few years ago, I was talking to a retired pro athlete and they were telling me how they regretted not enjoying the game as much when they played, that they hadn’t had more fun while they played. It wasn’t a particularly unique insight. I’ve heard it in a million speeches and interviews, but I was in the middle of a particularly hard writing project at the time and not having much fun. I remember thinking: I’ve made it. I’m a pro at this really cool job…why am I not enjoying myself? I’ve made a conscious effort since to appreciate that I get to do this, to not let it turn into a grind or a slog.