Ryan Holiday's Blog, page 18

June 23, 2020

You Must Live an Interesting Life

When I was starting out, I got a really good piece of advice. An author told me: If you want to be a great writer, go live an interesting life.

He was right. Great art is fueled by great experiences.

Or, if not “great” experiences, at least interesting or eye-opening ones.

That very encounter would illustrate that for me. I would go on to work for that writer for several years, seeing up close what profound psychological issues can do to a person and watching—and experiencing—the emotional wreckage this creates. I would look back on this period with regret… were it not for all the material it opened my eyes to and the cautionary tale it remains to me.

I don’t think this advice is limited just to writers.

Why was Seneca so wise? How has his philosophy been able to reach through the centuries and still grab readers by the throat? It’s because he had a wide swath of experiences to draw on, he had lived in such a way that he understood life.

Think about it: Seneca studied under a fascinating and controversial tutor named Attalus (who was later exiled). He started a legal career. Then he got tuberculosis and had to spend 10 years in Egypt, where he lived with his uncle Gaius Galerius who was prefect of Rome. Then on the journey back to Rome, a terrible shipwreck killed his uncle. Once in Rome, he entered politics, where his career was ascendant until he was exiled and nearly executed by the jealous emperor. He spent eight years on the distant island of Corsica before he was brought back to Rome to tutor Nero. Seneca served as consul. He became an investor. He had a wife. He had a son (who may have died tragically). He hosted parties. He did scientific experiments. He managed his family’s estates. He enjoyed gardening—“a hobby he found deeply sustaining,” biographer Emily Wilson writes, “and also informative as a way to think about how cultivation can be achieved.” He wrote letters and essays and speeches and poems and comedies and tragedies. He attended philosophy classes and civic center meetings and gladiatorial games and court hearings and theatrical performances. He served as consul, he tried to protect Rome from Nero’s worst impulses. He wrote plays. He wrote letters.

Of course he was wise. Look at all he experienced!

Branko Milanović recently wrote about just how uninspired the resumes of the young people he sees are:

He/she graduated from a very prestigious university as the best in their class; had many offers from equally prestigious universities; became an assistant professor at X, tenured at Y; wrote a seminal paper on Z when he/she was W. Served on one or two government panels. Moved to another prestigious university. Wrote another seminal paper. Then wrote a book. And then… this went on and on. You could create a single template, and just input the name of the author, and the titles of the papers, and perhaps only slight differences in age for each of them.

I was wondering: how can people who had lived such boring lives, mostly in one or two countries, with the knowledge of at most two languages, having read only the literature in one language, having travelled only from one campus to another, and perhaps from one hiking resort to another, have meaningful things to say about social sciences with all their fights, corruption, struggles, wars, betrayals and cheating. Had they been physicists or chemists, it would not matter. You do not have to lead an interesting life in order to understand how atoms move, but perhaps you do need it to understand what moves humans.

If you want to be a philosopher, if you want to be a good entrepreneur or a good coach or a good leader or a good parent or a good writer, you have to understand the world. You have to cultivate experiences. You have to see adversity first-hand. You have to take risks. You have to go do stuff.

Without this, not only are you boring, but you are sheltered and stupid. Marcus Aurelius said that no role is so well-suited to philosophy as the one we happen to be in. That’s true, but also we will be more well-suited to our roles if we had a wide breadth of experiences, and if we learn from all of them.

Emerson spoke of something very similar. He noted how fragile the “specialists” are:

If our young men miscarry in their first enterprises, they lose all heart. If the young merchant fails, men say he is ruined. If the finest genius studies at one of our colleges, and is not installed in an office within one year afterwards in the cities or suburbs of Boston or New York, it seems to his friends and to himself that he is right in being disheartened, and in complaining the rest of his life. A sturdy lad from New Hampshire or Vermont, who in turn tries all the professions, who teams it, farms it, peddles, keeps a school, preaches, edits a newspaper, goes to Congress, buys a township, and so forth, in successive years, and always, like a cat, falls on his feet, is worth a hundred of these city dolls. He walks abreast with his days, and feels no shame in not “studying a profession,” for he does not postpone his life, but lives already. He has not one chance, but a hundred chances.

So go live an interesting life.

How do you do that?

Well, life is always presenting you with opportunities. A road diverges in the woods, and we have a choice. The safe one and the dangerous one. The one that pays well and the one that teaches a lot. The one that people understand and the one they don’t. The one that challenges us and the one that doesn’t.

It’s the cumulative result of these choices that leads to a life worth writing about, or a life worth being written about. The person who chooses safety, familiarity, the same thing as everyone else? What perspectives will they gain that will allow them to be distinct, unique or wiser than others? What will the person who never risks hope to ever gain?

This will be a hard road, no question. There will be failure. There will be pain. You will kick yourself, at times, when you see people you went to high school with settling into nice houses or being recognized before you. You will envy, when you’re struggling, what seems like the easier path. You will wish you took it too sometimes.

But you have to remember, this is all adding up. You are putting in work. You are lifting weights. You are building a biography.

Nowhere is this more important than in the arts. One of the benefits of being an artist is that everything that happens to you—no matter how traumatic or frustrating—has at least one hidden benefit: It can be used in your art. A painful parting can become a powerful breakup anthem. Melancholy mixes in with your oil paints and transforms an ordinary image into something deeply moving. A mistake creates an insight that leads to an innovation, to a new angle on an old idea, to a brilliant passage in a book.

The writer Jorge Luis Borges spoke to that last benefit well:

A writer—and, I believe, generally all persons—must think that whatever happens to him or her is a resource. All things have been given to us for a purpose, and an artist must feel this more intensely. All that happens to us, including our humiliations, our misfortunes, our embarrassments, all is given to us as raw material, as clay, so that we may shape our art.

But make no mistake, this raw material is necessary for all professions of any importance.

In my own life, I have failed. I have traveled. I dropped out of college. I’ve started businesses and closed them. I’ve made money, lost money. Moved to different places, including a ranch. Met good people and bad people. Followed good people and bad people. Watched the rise and fall of American Apparel. Been in rooms where important things happened. Seen bureaucracy and incompetence up close, and excellence too. Been in rooms with important people (who turned out to be not very impressive). I’ve gone through pain. I’ve gone through loss. I’ve messed stuff up. I’ve had my hopes dashed. I’ve been surprised beyond my expectations.

I remember going through something tough once and my mentor Robert Greene giving me a shorter version of Borges’ advice.

It’s all material, he said. You’ve got to use this.

Everything that happens in your life can be used for something useful, whether it’s your writing, your relationships, or your new startup. Everything is material. We can use it all. Whether we’re a baseball player or a hedge fund manager, a psychiatrist or a cop. The issues we had with our parents become lessons that we teach our children. An injury that lays us up in bed becomes a reason to reflect on where our life is going. A problem at work inspires us to invent a new product and strike out on our own. These obstacles become opportunities. These experiences and failures and experimentations and setbacks and discoveries converge to give you what David Epstein calls range.

“As I write in Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World,” Epstein explained when I interviewed him for Daily Stoic, “your ability to take knowledge and skills and apply them to a problem or situation you have not seen before… is predicted by the variety of situations you’ve faced… This is true whether you’re training in soccer or math. As you get more variety… you’re forced to form these broader conceptual models, which you can then wield flexibly in new situations.” He then sums up research on how people find meaning and fulfillment, “Our insight into ourselves is constrained by our roster of previous experiences. We actually have to do stuff.”

The line from Marcus Aurelius about this was that a blazing fire makes flame and brightness out of everything that is thrown into it. That’s how we want to be. We want to be the artist that turns pain and frustration and even humiliation into beauty. We want to be the entrepreneur that turns a sticking point into a money maker. We want to be the person who takes their own experiences and turns them into wisdom that can be learned from and passed on to others.

So go look for fuel. Take the more interesting road.

Go live a life that is not boring.

Your work—and the world—will thank you for it.

The post You Must Live an Interesting Life appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

June 20, 2020

13 Lessons Marcus Aurelius Learned From His Father

How did Marcus Aurelius become Marcus Aurelius? How did a boy of relatively ordinary bloodlines etch his name so impressively into history? How did a man given absolute power, not only not become corrupted by it, but manage to prove himself worthy of the responsibility?

The answer is simple: The examples he was provided by his own stepfather made him into the person he became.

That’s something worth thinking about today—on Father’s Day—whether you’re a mom, a dad, a son or a daughter.

It wasn’t destiny or fate nor a fancy education that shaped Marcus. In fact, he was homeschooled by his grandparents during early childhood. Around the age of 12, a handful of tutors were selected by the emperor Hadrian, who saw something in the boy. But this was relatively common for the rich in those days. In fact, it’s an eerily similar background to Nero, who as we know, turned out rather differently.

Seneca, years earlier, instructing Nero, had spoken about the need to “choose yourself a Cato,” a model whose life can guide your own. For Marcus that man was Antoninus, a man who according to French philosopher Ernest Renan, Marcus considered “the most beautiful model of a perfect life.”

At some time near the end of his life, Marcus sat down and wrote what he learned from Antoninus. It’s an impressive list, one that we can learn from today in our own lives and more urgently, use to inspire our own children and shape a better future.

1: To Love Philosophy

Antoninus “honoured those who were true philosophers, and he did not reproach those who pretended to be philosophers, nor yet was he easily led by them.” The study of philosophy is something that lasts a lifetime… and the earlier it begins the better.

2: To Read And Study Widely

Antoninus had a “liberal attitude to education,” Marcus’ biographer Frank McLynn writes. He thought a person should seek to be useful, “not just masters of their disciplines but also well versed in politics and the problems of the state.” Yet Antoninus was hardly a bookish nerd—he was active and attentive to the world around him. When Marcus talks about throwing away his books and focusing—about being a good man and not just talking about one—it’s Antoninus he is referencing.

3: To Be Decisive

Antoninus had a remarkable “unwavering adherence to decisions,” Marcus tells us. “Once he’d reach them,” there was no hesitation, only resolute action. A leader, a father, a human being must be able to decide.

4: To Be Humble

On the emperor Hadrian’s deathbed, he summoned Antoninus. It was time to hand over the crown. Antoninus pushed back. With this “indifference to superficial honors” we’re told, Hadrian was certain he made the right decision in making Antoninus his heir. Marcus said he revered “His restrictions on acclamations—and all attempts to flatter him.” Imagine how powerful this was for Marcus when it came time for him to assume the throne. He saw that power didn’t have to corrupt, and he also knew that he had the power to resist it.

5: To Keep An Open Mind

Marcus liked the way Antoninus “listened to anyone who could contribute to the public good.” When historians later credited Marcus for his ability to get the best out of flawed people, they were acknowledging Antoninus’s influence. When Marcus would later talk about being happy to have been proven wrong, this too was a well-formed lesson from his stepfather.

6: To Work Hard

Antoninus was known to keep a strict diet, so he could spend less time exercising and more time serving the people of Rome. Marcus would later talk about rising early, working hard and doing what his nature and job required. That work ethic wasn’t inborn—it was developed. He learned it from example.

7: To Take Care of His Health

We said Antoninus was known to spend less time, not no time, exercising. Marcus praised “His willingness to take adequate care of himself… He hardly ever needed medical attention, or drugs or any sort of salve or ointment.”

8: To Be A Good Friend

Antoninus was “what we would nowadays call a ‘people person’,” McLynn writes. “He felt at ease with other people and could put them at their ease.” Even towards those disingenuous social climbers, Marcus admired how he never got “fed up with them.” This was particularly important for Marcus who appears to have been naturally introverted—his earnest efforts to serve the common good, to be a friend to all? That too was taught.

9: To Be Self-reliant

Antoninus showed Marcus that fortune was fickle. He “carried a spartan attitude to money in his private life, taking frugal meals and reducing the pomp on state occasions to republican simplicity.” Frugality and industry was the only way to guarantee financial security. Marcus said, “Self-reliance, always”—what a lesson for a father to teach a son.

10: To Look To Experts

When the plague hit Rome in 165 CE, Marcus knew what to do. He immediately assembled his team of Rome’s most brilliant minds. As McLynn explains, his “shrewd and careful personnel selection” is worthy of study by any person in any position of leadership. But “this, in particular,” Marcus said he learned from Antoninus: the “willingness to yield the floor to experts—in oratory, law, psychology, whatever—and to support them energetically, so that each of them could fulfill his potential.”

11: To Take Responsibility With No Excuses

Hadrian was known for his globe trotting and a tendency to seek some peace and quiet abroad when Rome was particularly chaotic. Other emperors retreated to pleasure palaces or blamed enemies for issues during their reign. In pointed disapproval, Marcus praised Antoninus’ “willingness to take responsibility—and blame—for [the empire’s needs and the treasury].”

12: To Not Lose Your Temper

Antoninus had what all truly great leaders have—he was cool under pressure: “He never exhibited rudeness, lost control of himself, or turned violent. No one ever saw him sweat. Everything was to be approached logically and with due consideration, in a calm and orderly fashion but decisively, with no loose ends.” It’s what Marcus was constantly reminding himself (and what inspired our Daily Stoic Taming Your Temper course). “When you start to lose your temper,” Marcus wrote, “remember: there’s nothing manly about rage.”

13: To Be Self-Controlled

“He knew how to enjoy and abstain from things that most people find it hard to abstain from and all too easy to enjoy. Strength, perseverance, self-control in both areas: the mark of a soul in readiness—indomitable.”

These were all lessons Marcus carried with him his whole life. They guided the most powerful man on the planet through many trying times. So much so that he recounted them in his private journal late in life. And we’re still recounting them close to 2,000 years later.

The things you teach your kids will shape their future. And their children’s future. So make sure you’re setting a good example. If your children were to write down what they learned from you on their deathbed, what would they write? You have the ability to shape that everyday. So start, now.

The post 13 Lessons Marcus Aurelius Learned From His Father appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

13 Lessons Marcus Aurelius Learned From His Father(s)

How did Marcus Aurelius become Marcus Aurelius? How did a boy of relatively ordinary bloodlines etch his name so impressively into history? How did a man given absolute power, not only not become corrupted by it, but manage to prove himself worthy of the responsibility?

The answer is simple: The examples he was provided by his own stepfather made him into the person he became.

That’s something worth thinking about today—on Father’s Day—whether you’re a mom, a dad, a son or a daughter.

It wasn’t destiny or fate nor a fancy education that shaped Marcus. In fact, he was homeschooled by his grandparents during early childhood. Around the age of 12, a handful of tutors were selected by the emperor Hadrian, who saw something in the boy. But this was relatively common for the rich in those days. In fact, it’s an eerily similar background to Nero, who as we know, turned out rather differently.

Seneca, years earlier, instructing Nero, had spoken about the need to “choose yourself a Cato,” a model whose life can guide your own. For Marcus that man was Antoninus, a man who according to French philosopher Ernest Renan, Marcus considered “the most beautiful model of a perfect life.”

At some time near the end of his life, Marcus sat down and wrote what he learned from Antoninus. It’s an impressive list, one that we can learn from today in our own lives and more urgently, use to inspire our own children and shape a better future.

1: To Love Philosophy

Antoninus “honoured those who were true philosophers, and he did not reproach those who pretended to be philosophers, nor yet was he easily led by them.” The study of philosophy is something that lasts a lifetime… and the earlier it begins the better.

2: To Read And Study Widely

Antoninus had a “liberal attitude to education,” Marcus’ biographer Frank McLynn writes. He thought a person should seek to be useful, “not just masters of their disciplines but also well versed in politics and the problems of the state.” Yet Antoninus was hardly a bookish nerd—he was active and attentive to the world around him. When Marcus talks about throwing away his books and focusing—about being a good man and not just talking about one—it’s Antoninus he is referencing.

3: To Be Decisive

Antoninus had a remarkable “unwavering adherence to decisions,” Marcus tells us. “Once he’d reach them,” there was no hesitation, only resolute action. A leader, a father, a human being must be able to decide.

4: To Be Humble

On the emperor Hadrian’s deathbed, he summoned Antoninus. It was time to hand over the crown. Antoninus pushed back. With this “indifference to superficial honors” we’re told, Hadrian was certain he made the right decision in making Antoninus his heir. Marcus said he revered “His restrictions on acclamations—and all attempts to flatter him.” Imagine how powerful this was for Marcus when it came time for him to assume the throne. He saw that power didn’t have to corrupt, and he also knew that he had the power to resist it.

5: To Keep An Open Mind

Marcus liked the way Antoninus “listened to anyone who could contribute to the public good.” When historians later credited Marcus for his ability to get the best out of flawed people, they were acknowledging Antoninus’s influence. When Marcus would later talk about being happy to have been proven wrong, this too was a well-formed lesson from his stepfather.

6: To Work Hard

Antoninus was known to keep a strict diet, so he could spend less time exercising and more time serving the people of Rome. Marcus would later talk about rising early, working hard and doing what his nature and job required. That work ethic wasn’t inborn—it was developed. He learned it from example.

7: To Take Care of His Health

We said Antoninus was known to spend less time, not no time, exercising. Marcus praised “His willingness to take adequate care of himself… He hardly ever needed medical attention, or drugs or any sort of salve or ointment.”

8: To Be A Good Friend

Antoninus was “what we would nowadays call a ‘people person’,” McLynn writes. “He felt at ease with other people and could put them at their ease.” Even towards those disingenuous social climbers, Marcus admired how he never got “fed up with them.” This was particularly important for Marcus who appears to have been naturally introverted—his earnest efforts to serve the common good, to be a friend to all? That too was taught.

9: To Be Self-reliant

Antoninus showed Marcus that fortune was fickle. He “carried a spartan attitude to money in his private life, taking frugal meals and reducing the pomp on state occasions to republican simplicity.” Frugality and industry was the only way to guarantee financial security. Marcus said, “Self-reliance, always”—what a lesson for a father to teach a son.

10: To Look To Experts

When the plague hit Rome in 165 CE, Marcus knew what to do. He immediately assembled his team of Rome’s most brilliant minds. As McLynn explains, his “shrewd and careful personnel selection” is worthy of study by any person in any position of leadership. But “this, in particular,” Marcus said he learned from Antoninus: the “willingness to yield the floor to experts—in oratory, law, psychology, whatever—and to support them energetically, so that each of them could fulfill his potential.”

11: To Take Responsibility With No Excuses

Hadrian was known for his globe trotting and a tendency to seek some peace and quiet abroad when Rome was particularly chaotic. Other emperors retreated to pleasure palaces or blamed enemies for issues during their reign. In pointed disapproval, Marcus praised Antoninus’ “willingness to take responsibility—and blame—for [the empire’s needs and the treasury].”

12: To Not Lose Your Temper

Antoninus had what all truly great leaders have—he was cool under pressure: “He never exhibited rudeness, lost control of himself, or turned violent. No one ever saw him sweat. Everything was to be approached logically and with due consideration, in a calm and orderly fashion but decisively, with no loose ends.” It’s what Marcus was constantly reminding himself (and what inspired our Daily Stoic Taming Your Temper course). “When you start to lose your temper,” Marcus wrote, “remember: there’s nothing manly about rage.”

13: To Be Self-Controlled

“He knew how to enjoy and abstain from things that most people find it hard to abstain from and all too easy to enjoy. Strength, perseverance, self-control in both areas: the mark of a soul in readiness—indomitable.”

These were all lessons Marcus carried with him his whole life. They guided the most powerful man on the planet through many trying times. So much so that he recounted them in his private journal late in life. And we’re still recounting them close to 2,000 years later.

The things you teach your kids will shape their future. And their children’s future. So make sure you’re setting a good example. If your children were to write down what they learned from you on their deathbed, what would they write? You have the ability to shape that everyday. So start, now.

The post 13 Lessons Marcus Aurelius Learned From His Father(s) appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

June 16, 2020

33 Things I Stole From People Smarter Than Me on the Way to 33

Last year was the first year I really forgot how old I was. This year was the year that I started doing stuff over again. Not out of nostalgia, or premature memory loss, but out of the sense that enough time had elapsed that it was time to revisit some things. I re-read books that I hadn’t touched in ten or fifteen years. I went back to places I hadn’t been since I was a kid. I re-visited some painful memories that I had walled off and chosen not to think about.

So I thought this year, for my birthday piece (more than 10 years running now—here is 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, and 32), I would revisit an article I wrote several years ago, which has remained popular since I first published it: 28 Pieces of Productivity Advice I Stole From People Smarter Than Me.

I’m not so interested in productivity advice anymore, but I remain, as ever, focused on taking advice from people smarter than me. So here are some of the best pieces of advice—things I try to live by, things I tried to revisit and think about this year—about life.

Enjoy. And remember, as Seneca said, that we are dying everyday. At 33, I don’t say to myself that according to actuary tables, I have 49 years to live. I say instead that I have already died three and one-third decades. The question is whether I lived those years before they passed. That’s what matters.

–George Raveling told me that he sees reading as a moral imperative. “People died,” he said, speaking of slaves, soldiers and civil rights activists, “so I could have the ability to read.” He also pointed out that there’s a reason people have fought so hard over the centuries to keep books from certain groups of people. I’ve always thought reading was important, but I never thought about it like that. If you’re not reading, if books aren’t playing a major role in your life, you are betraying that legacy.

-Another one on reading: in his autobiography, General James Mattis points out that if you haven’t read widely, you are functionally illiterate. That’s a great term, and one I wish I’d heard earlier. As Mark Twain said, if you don’t read, you’re not any better than people who can’t read. This is true not only generally but specifically on specific topics. I am functionally illiterate about many things and that needs to be fixed.

-Sue Johnson talks about how when couples or people fight, they’re not really fighting, they’re just doing a dance, usually a dance about attachment. The dance is the problem—you go this way, I go that way, you reach out, I pull away, I reach out, you pull away—not the couple, not either one of the people. This externalization has been very helpful.

-The last year has certainly revealed some things about a lot of folks that I know or thought I did. But before I get too disappointed, I think of that beautiful line from F. Scott Fitzgerald at the beginning of The Great Gatsby (discovered on a re-read): “Whenever you feel like criticizing any one, just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.”

-I’ve heard this many times from many different writers over the years (Neil Strauss being one), but as time passes the truth of it becomes more and more clear, and not just in writing: When someone tells you something is wrong, they’re almost always right. When someone tells you how to fix it, they’re almost always wrong.

-It was a French journalist who was writing a piece about Trust Me I’m Lying who happened to tell me something about relationships. LOVE, he said, is best spelled T-I-M-E. I don’t think I’ve heard anything truer or more important to my development as a husband or father.

-Also, Seinfeld’s concept of quality time vs. garbage time has been almost as essential to me as Robert Greene’s concept of alive time vs. dead time. I would be much worse without these two ideas.

-A few years ago I was exploring a book project with Lance Armstrong and he showed me some of the texts people had sent him when his world came crashing down. “Some people lean in when their friends take heat,” he said, “some people lean away.” I decided I wanted to be a lean-in type, even if I didn’t always agree, even if it was their fault.

-When I was in high school, I was in this English class and I shared something with the discussion group we were in. Then later, I heard people use what I had said in their essays or in presentations and get credit for it. I brought this up to the teacher later, that people were using my ideas. The teacher looked at me and said, “Ryan, that’s your job.” I’m very glad she said that and that I heard it at 16.

-Another thing about being a writer. I once read a letter where Cheryl Strayed kindly pointed out to a young writer the distinction between writing and publishing. Her implication was that we focus too much on the latter and not enough on the former. It’s true for most things. Amateurs focus on outcomes more than process. The more professional you get, the less you care about results. It seems paradoxical but it’s true. You still get results, but that’s because you know that the systems and process are reliable. You trust them with your life.

-Speaking of which, that distinction between amateur and professional is an essential piece of advice I have gotten, first from Steven Pressfield’s writings and then by getting to know him over the years. There are professional habits and amateur ones. Which are you practicing? Is this a pro or an amateur move? Ask yourself that. Constantly.

-Peter Thiel: “Competition is for losers.” I loved this the second I heard it. When people compete, somebody loses. So go where you’re the only one. Do what only you can do. Run a race with yourself.

-This headline from Kayla Chadwick is one of the best of the century, in my opinion. And true. And sums up our times: “I Don’t Know How To Explain To You That You Should Care About Other People.”

–Tim Ferriss always seems to ask the best questions: What would this look like if it were easy? How will you know if you don’t experiment? What would less be like? The one that hit me the hardest, when I was maybe 25, was “What do you do with your money?” The answer was “Nothing, really.” Ok, so why try so hard to earn lots more of it?

-It was from Hemingway and Tobias Wolff and John Fante that I learned about typing up passages, about feeling great writing go through your fingers. It’s a practice I’ve followed for… 15 years now? I’ve probably copied and typed out a couple dozen books this way. It’s a form of getting your hours, modeling greatness so that it gets seeded into your subconscious. (For writing, you can substitute any activity.)

-Talked about re-watching earlier. The scene from Tombstone still stays with me (and also sums up our times):

Wyatt Earp:

What makes a man like Ringo, Doc? What makes him do the things he does?

Doc Holliday:

A man like Ringo has got a great big hole, right in the middle of himself. And he can never kill enough, or steal enough, or inflict enough pain to ever fill it.

Wyatt Earp:

What does he want?

Doc Holliday:

Revenge.

Wyatt Earp:

For what?

Doc Holliday:

Bein’ born.

-Steve Kamb told me that the best and most polite excuse is just to say you have a rule. “I have a rule that I don’t decide on the phone.” “I have a rule that I don’t accept gifts.” “I have a rule that I don’t speak for free anymore.” “I have a rule that I am home for bath time with the kids every night.” People respect rules, and they accept that it’s not you rejecting the [offer, request, demand, opportunity] but that the rule allows you no choice.

-Go to what will teach you the most, not what will pay the most. I forget who this was from. Aaron Ray, maybe? It’s about the opportunities that you’ll learn the most from. That’s the rubric. That’s how you get better. People sometimes try to sweeten speaking offers by mentioning how glamorous the location is, or how much fun it will be. I’d be more impressed if they told me I was going to have a conversation that was going to blow my mind.

-I’ve been in too many locker rooms not to notice that teams put up their values on the wall. Every hallway and doorway is decorated with a motivational quote. At first, it seemed silly. Then you realize: It’s one thing to hear something, it’s another to live up to it each day. Thus the prints we do at Daily Stoic, the challenge coins I carry in my pocket, the statues I have on my desk, that art I have on my wall. You have to put your precepts up for display. You have to make them inescapable. Or the idea will escape you when it counts.

-Amelia Earhart: “Always think with your stick forward.” (Gotta keep moving, can’t slow down.)

-I was at Neil Strauss’s house almost ten years ago now when he had everyone break down what an hour of their time was worth. It’s simple: How much you make a year, divided by how many hours you realistically work. “Basically,” he said, “don’t do anything you can pay someone to do for you more cheaply.” This was hard for me to accept—still is—but coming to terms with it (in my own way) has made my life much, much better. It goes to Tim’s question as well: What would it look like if this were easy? Most of the time, it means getting someone to help.

-”No man steps in the same river twice.” That’s Heraclitus. Thus the re-reading. The books are the same, but we’ve changed, the world has changed. So it goes for movies, walking your college campus or a Civil War battlefield, and so many of the things we do once and think we “got.”

-”Well begun is half-done” is the expression. It has been a long journey but slowly and steadily optimizing my morning has more impact on my life than anything else. I stole most of my strategies from people like Julia Cameron (morning pages), Shane Parrish (wake up early), the folks at SPAR! (no phone in the AM), Ferriss (make before you manage), etc. (You can see more about my morning here.)

-”Your last book won’t write your next one.” Don’t remember who said it, but it’s true for writing and for all professions. You are constantly starting at zero. Every sale is a new sale. Every season is a new season. Every fight is a new fight. If you think your past success guarantees you anything, you’re in for a rude awakening. In fact, someone has already started to beat you.

–David French: “Human beings need forgiveness like we need oxygen—a nation devoid of grace will make its people miserable.”

-Dov Charney said something to me once that I think about a lot. He said, “Run rates always start at zero.” The point there was: Don’t be discouraged at the outset. It takes time to build up from nothing.

-I read this passage in a post from Chris Yeh, which apparently comes from a speech by Brian Dyson:

“Imagine life as a game in which you are juggling some five balls in the air. You name them—work, family, health, friends and spirit … and you’re keeping all of these in the air. You will soon understand that work is a rubber ball. If you drop it, it will bounce back. But the other four balls—family, health, friends and spirit—are made of glass. If you drop one of these, they will be irrevocably scuffed, marked, nicked, damaged or even shattered. They will never be the same.”

–There is no party line. That’s what Allan Ginsberg’s psychiatrist told him when he asked for the professional opinion on dropping out of college. This is good advice for life. There is no party line on what you should or shouldn’t do. And if you think there is, you’re probably missing stuff.

–James Altucher once pointed out that you don’t have to make your money grow. You can just have it. It can just sit there. You can spend it. Whatever. You don’t have to whip yourself for not investing and carefully managing every penny. The reward for success should not be that you’re constantly stressed you’re not doing enough to “capitalize” on that success.

-At the same time, I love Charlamagne’s “Frugal Vandross.” The less expensive stuff you have, the less there is to worry about.

-I’ve talked before how I got my notecard system from Robert Greene. Only later did I realize—to steal a concept from Tyler Cowen—that doing notecards is an effective way to “do scales.” Meaning: How do you practice whatever it is that you do? What’s your version of playing scales or running through drills? For me, it’s the notecards. That’s how I get better at my job. Do you have something like that?

–Ramit Sethi talks about how you can just not reply to stuff. It felt rude at first, but then I realized it was ruder to ignore the people I care about to respond to things I didn’t ask for in the first place. Selective ignoring is the key to productivity, I’m afraid.

-Before we had kids, I was in the pool with my wife. “Do you want to do laps?” I said. “Should we fill up the rafts?” “Here help me dump out the filter.” There was a bunch of that from me. “You know you can just be in the pool,” she said. That thought had not occurred to me. Still, it rarely does. So I have to be intentional about it.

**

Who better to close another year, another piece than with the Stoics. “You could be good today,” the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote. “But instead you choose tomorrow.”

That quote haunts me as much as it inspires me. And it does a lot of each. It’s worth stealing if you haven’t already.

The post 33 Things I Stole From People Smarter Than Me on the Way to 33 appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

June 9, 2020

It’s Always the Time to Act Bravely

In light of everything that’s going on in this world, I wanted to revisit one of the most important (to me) chapters in Stillness Is the Key .

To see people who will notice a need in the world and do something about it… Those are my heroes. — Fred Rogers

In Camus’s final novel, The Fall, his narrator, Clamence, is walking alone on a street in Amsterdam when he hears what sounds like a woman falling into the water. He’s not totally certain that’s what he heard, but mostly, riding the high of a nice evening with his mistress, he does not want to be bothered, and so he continues on.

A respected lawyer with a reputation as a person of great virtue in his community, Clamence returns to his normal life the following day and attempts to forget the sound he heard. He continues to represent clients and entertain his friends with persuasive political arguments, as he always had.

Yet he begins to feel off.

One day, after a triumphant appearance in court arguing for a blind client, Clamence gets the feeling he is being mocked and laughed at by a group of strangers he can’t quite locate. Later, approaching a stalled motorist in an intersection, he is unexpectedly insulted and then assaulted. These encounters are unrelated, but they contribute to a weakening of the illusions he had long held about himself.

It is not with an epiphany or from a blow to the head that the monstrous truth of what he’d done becomes clear. It is a slow, creeping realization that comes to Clamence that suddenly and irrevocably changes his self-perception: That night on the canal he had shrugged off a chance to save someone from committing suicide.

This realization is Clamence’s undoing and the central focus of the book. Forced to see the hollowness of his pretensions and the shame of his failings, he unravels. He had believed he was a good man. But when the moment (indeed moments) called for goodness, he slunk off into the night.

It’s a thought that haunts him incessantly. As he walks the streets at night, the cry of that woman—the one he ignored so many years ago—never ceases to torment him. It toys with him too, because his only hope at redemption is that he might hear it again in real life and then seize the opportunity to dive in and save someone from the bottom of the canal.

It’s too late. He has failed. He will never be at peace again.

The story is fictional, of course, but a deeply incisive one, written not coincidentally in the aftermath of the incredible moral failings of Europe in the Second World War. Camus’s message to the reader pierces us like the scream of the woman in Clamence’s memory: High-minded talk is one thing, but all that matters is what you do. That the health of our spiritual ideals depends on what we do with our bodies in moments of truth.

It is worth comparing the agony and torture of Clamence with another more recent example from another French philosopher, Anne Dufourmantelle, aged fifty-three, who died in 2017 rushing into the surf to save two drowning children who were not her own. In her writing, Anne had spoken often of risk—saying that it was impossible to live life without risk and that in fact, life is risk. It is in the presence of danger, she once said in an interview, that we are gifted with the “strong incentive for action, dedication, and surpassing oneself.”

And when, on the beach in Saint-Tropez, she was faced with a moment of danger and risk, an opportunity to turn away or to do good, she committed the full measure of devotion to her ideals.

What is better? To live as a coward or to die a hero? To fall woefully short of what you know to be right or to fall in the line of duty? And which is more natural? To refuse a call from your fellow humans or to dive in bravely and help them when they need you?

Stillness is not an excuse to withdraw from the affairs of the world. Quite the opposite—it’s a tool to let you do more good for more people.

Neither the Buddhists nor the Stoics believe in what has come to be called “original sin”—that we are a fallen and broken species. On the contrary, they believe we were born good. To them, the phrase “Be natural” was the same as “Do the right thing.” For Aristotle, virtue wasn’t just something contained in the soul—it was how we lived. It was what we did. He called it eudaimonia: human flourishing.

A person who makes selfish choices or acts contrary to their conscience will never be at peace. A person who sits back while others suffer or struggle will never feel good, or feel like they are enough, no matter how much they accomplish or how impressive their reputation may be.

A person who does good regularly will feel good. A person who contributes to their community will feel like they are a part of one. A person who puts their body to good use—volunteering, protecting, serving, standing up for—will not need to treat it like an amusement park to get some thrills.

Virtue is not an abstract notion. We are not clearing our minds and separating the essential from the inessential for the purposes of a parlor trick. Nor are we improving ourselves so that we can get richer or more powerful.

We are doing it to live better and be better.

Every person we meet and every situation we find ourselves in is an opportunity to prove that.

It’s the old Boy Scout motto: “Do a Good Turn Daily.”

Some good turns are big, like saving a life or protecting the environment. But good turns can also be small, Scouts are taught, like a thoughtful gesture, mowing a neighbor’s lawn, calling 911 when you see something amiss, holding open a door, making friends with a new kid at school. It’s the brave who do these things. It’s the people who do these things who make the world worth living in.

Marcus Aurelius spoke of moving from one unselfish action to another—”only there,” he said, can we find “delight and stillness.” In the Bible, Matthew 5:6 says that those who do right will be made full by God. Too many believers seem to think that belief is enough. How many people who claim to be of this religion or that one, if caught and investigated, would be found guilty of living the tenets of love and charity and selflessness?

Take action.

Pick up the phone and make the call to tell someone what they mean to you. Share your wealth. Run for office. Pick up the trash you see on the ground. Step in when someone is being bullied. Step in even if you’re scared, even if you might get hurt. Tell the truth. Maintain your vows, keep your word. Stretch out a hand to someone who has fallen.

Do the hard good deeds. “You must do the thing you cannot do,” Eleanor Roosevelt said.

It will be scary. It won’t always be easy, but know that what is on the other side of goodness is true stillness.

Think of Dorothy Day, and indeed, many other less famous Catholic nuns, who worked themselves to the bone helping other people. While they may have lacked for physician possessions and wealth, they found great comfort in seeing the shelters they had provided, and the self-respect they’d restored for people whom society had cast aside. Let us compare that to the anxiety of the helicopter parents who think of nothing but which preschool in which to enroll their toddler, or the embezzling business partner who is just one audit away from getting caught. Compare that to the nagging insecurity that we feel knowing that we are not living the way we should, or that we are not doing enough for other people.

When the Stoics talk about doing the right thing, know that they are not just advocating for common good. They are thinking of you, too. We should do the right thing not just because it’s right but because if we don’t, it will be impossible for us to respect ourselves. The hardest person to be is the coward or the cheat, for though they get out of doing difficult things, they feel the most shame in the quiet moments when they are alone.

If you see fraud, and do not say fraud, the philosopher Nassim Taleb has said, you are a fraud. Worse, you will feel like a fraud. And you will never feel proud or happy or confident.

Will we fall short of our own standards? Yes. When this happens, we don’t need to whip ourselves like Clamence did, we must simply let it instruct and teach us, like all injuries do.

That’s why twelve-step groups ask their members to be of service as part of their recovery. Not because good deeds can undo the past, but because it helps us get out of our heads, and in the process, helps us write the script for a better future.

If we want to be good and feel good, we have to do good.

There is no escaping this.

Dive in when you hear the cry for help. Reach out when you see the need. Do kindness where you can.

Because you’ll have to find a way to live with yourself if you don’t.

In life, you should always act with the Four Stoic Virtues in mind: courage, wisdom, temperance, and justice. A great way to keep these virtues in mind is Daily Stoic’s Four Virtues medallion . Keep it in your pocket or by your side always, to remind yourself of the importance of these virtues and the need to exemplify them every day.

The post It’s Always the Time to Act Bravely appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

June 2, 2020

This Is Why You Have to Care

Then, as now, there was a lot of noise.

There were people who had their own agendas. People who wanted to compromise. People who wanted to explain it away. People who thought there were bigger problems.

One of the most powerful scenes in the history of cinema captures all of this coming to a head. Daniel Day-Lewis as Lincoln is surrounded by grousing and squabbling cabinet members as he pushes for passage of the 13th Amendment. He slams his open hand down on the table. It buys a second of silence.

“Now, now, now,” he says. “We are stepped out on the world’s stage, the fate of human dignity is in our hands… See what is before you. See the here and now, that’s the hardest thing, the only thing that accounts.”

I think of this scene often, but especially lately. Because there are many people who seem to be unable to do that. Who seem to think the situation we are in follows along the same partisan lines as the rest of the ongoing culture war. There seem to be many people who think there is something to argue about here, that it can be explained away, that this is just an extension of that discussion we’ve been having as a society for some time now about “privilege.”

No.

The fact that my publisher sends me early copies of books before they are released, that’s a privilege. Something I didn’t earn, something that can disappear, something that I enjoy but am not entitled to.

Not being gunned down in the street by hillbilly vigilantes? Not having the life slowly squeezed out of me on suspicion of some minor crime?

That’s not a privilege.

That’s a constitutional right. Actually, it’s more than a constitutional right. According to the Founding Fathers and many philosophers before and since, the rights to life and liberty and property are beyond constitutional: They are inalienable.

The right not to be murdered, to not be harassed by people with guns, to not be targeted, exploited or incarcerated unfairly, to speak your mind, to pursue your religion, for your home to be a safe haven, these are not things that governments give to their people. These are things that God—or generations of evolution and progress—have endowed us with at birth, and we in turn give governments the powers to protect.

All of us.

What you are seeing in the video where a police officer kneels on the neck of a black man crying for air and his mother, what is happening in a video where a black man is strangled to death over selling cigarettes on the street, what has been occurring in my county where Latinos are targeted with ticky-tack traffic violations so they can be detained and then deported, is a betrayal of that compact. It’s a heinous violation of the rights of human beings.

Right here. Within your borders. Filmed for you to watch on your television or phone.

It is essential that you see it this way. Because when you do, you realize that this affects you, it affects everyone. Directly. Urgently.

Black. White. Rich. Poor. Young. Old. Republican. Democrat. Socialist. Idiot. If that’s threatened for one person, for one community, it’s threatened for all people.

I’ll say it again: Not being extrajudicially murdered is not a privilege, it’s not an “exception,” it’s more than a tragedy. To try to categorize it as those things is to woefully fail to describe the injustice that is being done in modern America (and elsewhere). Callous indifference to suffering by the authorities towards minorities or the poor or the voiceless is not just a lamentable fact of modern life, it’s an active crime.

In real life, Lincoln said that if slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong. If kneeling on an unarmed, compliant man’s neck for nine minutes is not wrong, nothing is wrong. If chasing down someone you think was maybe breaking into a house (not your house, even) and then blowing them apart with a shotgun in broad daylight is not wrong, nothing is wrong. If putting children in cages is not wrong, nothing is wrong. Even if those were the only examples ever, that would be important. That in and of itself would suffice as a major issue that would need to be addressed, before it got worse.

But of course, they are not the only examples.

The moral imperative to do something about it is ancient. Marcus Aurelius wrote two thousand years ago that “you can also commit an injustice by doing nothing.” The Stoics believed that harm to one was to harm all. Martin Luther King explained this idea of sympatheia beautifully. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” he said. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

I understand that this might not be what you want to hear from me. I write about self-improvement. I write about philosophy. I write about history. That’s true.

But what do you think the point of the study of those three things are? It’s not so you can make a little more money. It’s not so you can live in your own bubble or have interesting dinner conversations. It’s so you can be better. So you can do the right thing when it counts.

You have to realize that if the state can find ways to deprive someone of their rights, then they can find ways to deprive you of yours. In fact, this is an inexorable law of power, whether it’s held by segregationists or Stalin, bureaucrats following orders or malevolent dictators. When you give power an inch, it takes another. When you allow evil to happen because you are not its victim, it will inevitably find its way to you—or if not you, to someone you love, or to your great-great-grandchildren.

That’s what Martin Niemöller’s famous poem “First they came…” is about. You know it:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Niemöller’s words were not theoretical. He tolerated, even complied with, policies he didn’t agree with. He rationalized them assuming his Christian church would be protected. For a while, it was. But in the end, Niemöller found himself in Dachau, where he nearly died. Someone later asked how he could have been so self-absorbed, so silent when it mattered. “I am paying for that mistake now,” he said, “and not me alone, but thousands of other persons like me.”

Well, here we are, stepped out on the world’s stage again. Can you see that? Can you see that everyone is watching? Can you grasp the here-and-now? Can you feel what is in your hands?

It’s the hardest thing, but it’s the only thing that counts.

Everything else is noise. Everything else is wrong.

Now. Now. Now.

The post This Is Why You Have to Care appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

May 26, 2020

How Marcus Aurelius Conquered Stress (and the Rest of Us Can Too)

To say that Marcus Aurelius had a stressful life would be a preposterous understatement.

He ran the largest empire in the world. He had a troublesome son. He had a nagging and painful stomach issue. There was a palace coup led by one of his closest friends. Rumors that his wife was unfaithful. The Parthians invaded the Roman client-state of Armenia, triggering a war that would last five years.. The Antonine Plague struck in 165 CE and killed, by conservative estimates, more than 10 million. The River Tiber had one of the worst floods in history, destroying homes and livestock and leaving Rome in famine.

Should we be surprised that he talks openly in Meditations about his anxiety? About losing his temper? That he sometimes felt ground down and exhausted by life?

Of course he did.

He had all our problems and more.

He was besieged by stress.

And yet that’s exactly why he inspires us. Because he conquered that stress, just like we can.

“Today I escaped anxiety,” he writes. “Or no, I discarded it, because it was within me, in my own perceptions—not outside.”

How did he do that? What can he show us about slaying that demon of stress that we all suffer from?

A lot.

For starters, the fact that we even know about his anxiety is because of one of those strategies. It was in the pages of his journal that Marcus worked through his problems. Instead of letting racing thoughts dominate his mind and drive him crazy, he put them down on paper. It was also in these pages that Marcus prepared himself for difficulties in advance. He reminded himself that the people he was going to meet during the day would be troublesome, he reminded himself that things were not going to go perfectly, he reminded himself that getting angry never made things better.

By taking the time to journal and write, he was chipping away at his anxiety, just as we all can–in the morning, at night, on our lunch break. Whenever.

To calm his anxiety, Marcus was also constantly trying to get perspective. Sometimes he zoomed way out. He meditated on his insignificance. “The infinity of past and future gapes before us,” he wrote, “a chasm whose depths we cannot see. So it would take an idiot to feel self-importance or distress.”Other times, he zoomed way in, telling himself to take things step by step, moment by moment. No one can stop you from that, he said. Concentrate like a Roman, he said, on what’s in front of you like it’s the last thing you’re doing in your life.

Don’t worry about what’s happened in the past or what might happen in the future.

This idea of being present is key to overcoming our stress.

We are often anxious because of what we fear will happen next, or after what happens next. We worry about worst case scenarios. We dread potential obstacles. But Marcus, from Epictetus, knew that “Man is not worried by real problems so much as by his imagined anxieties about real problems.”

That’s why Marcus Aurelius spent some much time trying to be present, reminding himself to return to the present moment where nothing is “novel or hard to deal with, but familiar and easily handled.”.

Like all busy people, Marcus Aurelius had a million things going on. But he also knew that much of what people expected of him or even that he found himself focusing on was not important or necessary. So to reduce stress, he tried hard to separate the essential from the inessential.

“If you seek tranquility, do less.” But then he makes a critical clarification, “Or (more accurately) do what’s essential… Because most of what we say and do is not essential. If you can eliminate it, you’ll have more time.”

Was there stuff he had to do that he didn’t want to do? Problems he was stuck with that he’d rather not be stuck with? You bet. That’s life.

Which is why he, and all of us, have to practice acceptance.

That’s all we need, he said, willing acceptance at every moment. You can scream “until you turn blue” and curse the world “as if the world would notice!” Or you can “accept the obstacle and work with what you’re given.”

Finally, Marcus Aurelius worked hard to be a good friend to himself. Although he was firm and strong and self-disciplined, he did not whip himself. He knew that it was inevitable that he would mess up. We all do.

The key, he said, is to just focus on getting back on track. Don’t dwell. Don’t call yourself an idiot. Don’t smack your forehead in anger.

No, “get back up when you fail,” he said, “celebrate behaving like a human.” “When jarred, unavoidably, by circumstances,” he said, “revert at once to yourself, and don’t lose the rhythm more than you can help. You’ll have a better grasp of the harmony if you keep on going back to it.”

It would be wonderful if we didn’t have to do any of this.

If life was easy. If things always went right.

That’s just not possible though.

Stress is an inevitable part of life. It is the friction of the plates of our responsibility rubbing against each other.

But if stress is inevitable, anxiety and anger and worry are not. Marcus believed that these things were a choice. That we could work past them, through them, that we could discard them, as he said, because they are within us, or at least up to us.

We can slay our stress because it’s not an external enemy.

It is an inner battle.

The post How Marcus Aurelius Conquered Stress (and the Rest of Us Can Too) appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

May 19, 2020

Can You Be Still?

Odysseus is the greatest hero in all of literature.

He fights for ten years at Troy and then, in a stroke of brilliance, manages to end the war with a clever trick.

Then for another ten years he fights his way home—facing storms, temptation, a Cyclops, deadly whirlpools, food shortages, the underworld, and a six-headed monster to return to his beloved wife and son.

Arriving in Ithaca, Odysseus finds his kingdom drained by thirsty suitors who will not leave. One against 100 men vying to court his wife—he defeats them all, returning to the bed and the woman and the boy he had missed so badly.

A true hero, no? A timeless icon of perseverance, commitment and duty.

Or maybe not. Maybe Odysseus is a tragic figure. Maybe he’s someone to pity. Because in reality—to the extent there is realness in all myths—he’s actually a broken, selfish addict.

It’s easy to miss unless you read all the way to the end of the poem. In fact, in some translations it’s cut off. In others it is simply ignored.

See, the first thing a normal healthy person would do upon returning home from such an epic odyssey, would be to celebrate, to breathe a sigh of relief, to enjoy it. But what does Odysseus do? He doesn’t express gratitude to the gods for guiding his journey. He doesn’t take a well-deserved rest or appreciate all that remains—including his sweet wife, his only child and his aging father—despite his prolonged absence.

Instead he seizes this moment, as Emily Wilson beautifully translates, to deliver this insane speech to his long-suffering wife:

But now we have returned to our own bed,

As we both longed to do. You must look after

My property inside the house. Meanwhile,

I have to go on raids, to steal replacements

For all the sheep those swaggering suitors killed,

And get the other Greeks to give me more,

until I fill my folds.

Twenty years away… and the first thing he wants to do is leave again! How sad is that? How tortured a mind must be to make that priority number one?

You sit with that scene for a moment and you begin to realize that maybe it wasn’t fate that caused all these problems for Odysseus, it was his own restlessness. It was his inability to be still. The monsters he fought and fled on the long journey home weren’t external, they were internal. And then you realize the truth of what the Stoics said: there’s a fine line between being courageous and being reckless.

If you’ve ever read the Tennyson poem about Odysseus, this last oft-ignored bit from Homer’s version might shine a whole different light on what Tennyson was actually getting at. It’s not that Odysseus is the brave striver, who refuses to yield, “made weak by time and fate, but strong in will.” It’s actually that he’s addicted to the road, to work, incapable of peace. Tennyson wasn’t praising Odysseus, he was weeping for him, damning him with his own nature:

Yet all experience is an arch wherethro’

Gleams that untravell’d world whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnish’d, not to shine in use!

…

‘T is not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

Of course, Odysseus isn’t unique. He is us. He’s the human condition in a nutshell. As Blaise Pascal put it, “all of humanity’s problems stem from our inability to sit quietly in a room.” Because we cannot be happy, because we can’t just be, we waste years of our life.

We go begging for trouble. We invent problems. We busy ourselves. We neglect our families. We flee, as Seneca once put it, from ourselves. Then we justify it, pride ourselves on it, point to our restlessness and call it ambition or responsibility.

There is a haunting clip of Joan Rivers, well into her seventies, already one of the most accomplished and respected and talented comedians of all time, in which she is asked why she keeps working, why she is always on the road, always looking for more gigs. Telling the interviewer about the fear that drives her, she holds up an empty calendar. “If my book ever looked like this, it would mean that nobody wants me, that everything I ever tried to do in life didn’t work. Nobody cared and I’ve been totally forgotten.” Here is someone who thinks she is nothing and doesn’t matter if she isn’t doing something for even a few days. It’s one of the saddest things a person has ever said without realizing it.

The Odyssey, like this unwitting admission from Rivers, is a cautionary tale. It is a beautifully epic reminder that stillness is the key to that which we all seek. “People try to get away from it all,” Marcus Aurelius said, “to the country, to the beach, to the mountains. You always wish that you could too. Which is idiotic: you can get away from it anytime you like. By going within. Nowhere you can go is more peaceful—more free of interruptions—than your own soul.” There, said the man who had the means and the power to justify doing anything and going anywhere, is where you “reach utter stillness.”

Stillness is how you connect to yourself and others. Stillness is where true happiness comes from.

Indeed, that’s the mistake the ceaselessly busy make. They think they are better for the frenzy, in fact, it’s the moments of stillness that afford them the ability to be so busy. Stillness was where Joan Rivers did her best writing—no one can write without quiet and reflection. Stillness, ironically, is how Odysseus waited out six-headed monsters and ship-swallowing storms. It wasn’t in rushing out to sea or to the next meeting or to the next opportunity. Stillness was how he connected with Penelope, it was the marriage bed he had made for them, that he so brilliantly described that made her realize that this unrecognizable man was the husband who had been gone so long.

The events of the world have conspired in this moment to demand that you ask yourself:

Where is all this rushing taking you? What direction was Odysseus pointing his ship? We are rushing toward death. A life of restlessness is not what we’re after. A life filled with endless activity… in the end, it is nothing. That’s not where meaning comes from.

No one is saying that Odysseus should just lay back and lounge for the rest of his life—but if he can’t take even a few minutes with his family after that long of an absence, something is wrong with him. Turns out the war with Troy was the sideshow—the real battle was in this guy’s head and heart… fought against the fear of not doing something, of not being in motion constantly, of the mistaken prospect that to be still was to be dead. And so it is for you.

We fight the curse of ambition and drive.

There is no greatness that is not at peace, Seneca reminds us. There is no greatness if we cannot be. We must take the odyssey within. We must be still.

The post Can You Be Still? appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

May 12, 2020

You Must Stare This Scary Fact in the Face.

If you have ever looked at much ancient or medieval art, you’ll notice something:

Death is everywhere.

The French painter Philippe de Champaigne’s famous “Still Life with a Skull,” which shows the three essentials of existence—the tulip (life), the skull (death), and the hourglass (time).

The beautiful anonymous German engraving from 1635 that features a standing, smiling skeleton aiming a crossbow.

The towering wall of hundreds of smiling skulls unearthed at the ruins of the Great Temple in the Aztec capital.

The famous cadaver tombs of Europe.

The plastered Jericho skulls filled with soil and decorated with seashells from some 9,500 years ago.

There’s even a church in Rome made almost entirely out of the bones of the dead priests that have worked there over the centuries.

And this is a trend that has continued up through the modern era. One of Vincent van Gogh’s earliest works is “Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette.” There is even an early—though mostly forgotten—Walt Disney cartoon called “Silly Symphony” which is five minutes of dancing skeletons doing also sorts of funny but macabre things. And in 2007, an artist in Richmond, Virginia named Noah Scalin who spent an entire year making a “skull-a-day” out of anything he could get his hands on.

Why is death so common in art?

It’s because death is common in life. And it was once even more common.

Take someone like Marcus Aurelius. His father died when he was just a boy. His grandparents shortly after. He lost his adopted father and cherished mentor. Of his children, eight died before he did. His 15-year reign was flooded with wars abroad and plagues at home.

Even his last words. In 180 CE, having led Rome through the worst of the Antonine Plague, which killed more than 10 million people, Marcus began to show symptoms of the disease. By his doctors’ diagnosis, he had only a few days to live. He sent for his five most-trusted friends to plan for his succession and to ensure a peaceful transition of power. Bereft with grief, these advisors were almost too pained to focus. “Marcus reproached them for taking such an unphilosophical attitude,” biographer Frank McLynn writes. “They should instead be thinking about the implications of the Antonine plague and pondering death in general.”

“Weep not for me,” began Marcus’s famous last words, “think rather of the pestilence and the deaths of so many others.”

Memento Mori. Remember we are mortal.

It’s a constant theme in art because it’s a fact that’s as easy to forget as it is scary to think about. It’s unpleasant. And besides… given all our modern advancements in technology, isn’t it a little fatalistic? Isn’t there a chance we may live forever?

There’s nothing quite like a global pandemic to wake us up from our silly fantasies.

Less than two months after the Chair of the 7th District of the New York City Council Health Committee poked fun at the “#coronavirus scare,” the now sobered Mark Levine announced the potential need for temporary graves in public parks. Parks, hospital ships, refrigerated trucks, and other “makeshift morgues” filled faster than the hospitals did and by the end of April, New York City “ran out of space” for its dead.

Maybe we all should have been a little more prepared, a little stronger and tougher… a little less convinced that we had escaped the fate of those that lived long ago.

They certainly tried to warn us, in their writing and by example.

Moses said, “Teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom.” Michelangelo said, “No thought exists in me which death has not carved with his chisel.” The essayist Michel de Montaigne was fond of the ancient Egyptian custom where during times of festivities, a skeleton would be brought out with people cheering “Drink and be merry, for when you’re dead you will look like this.” Shakespeare wrote, “Every third thought should be my grave.” Mozart said, “As death, when we come to consider it closely, is the true goal of our existence.” And Tolstoy said, “If we kept in mind that we will soon inevitably die, our lives would be completely different.”

That’s over 3,000 years of wisdom on the same theme… a theme which predated and continued long after each of them… and will continue after us as well.

For most of history, memento mori was more than “art,” it was a practice. Desks were staged with skulls to remind people of the urgency of life. On their walls hung paintings of skeletons, hour glasses, extinguished candles, wilting tulips. In their pockets they carried memento mori medallions and watch keys. It “wasn’t just a generalized response to mortality,” says Elizabeth Welch, an art curator at the Blanton Museum, “but instead specifically a performative social leveling that could be used by Late Medieval Christians to think about mortality and the inevitability of physical decay.”

The physical manifestation of a memento mori helped our ancestors process the pain that followed them around each day. The bodies on the streets and battlefields didn’t create panic, but priority, humility, urgency, appreciation.

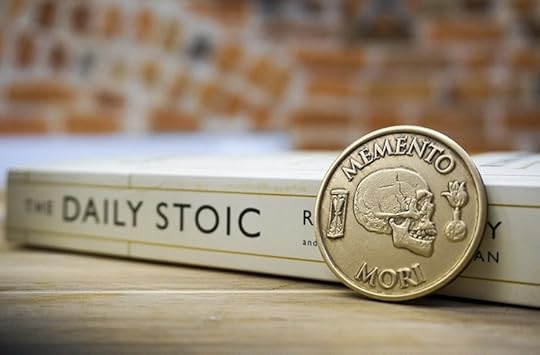

I’ve talked about my own Memento Mori, a two-sided coin, before. On the front it has a rendering of Champaigne’s Still Life with a Skull painting. On the back, it has Marcus Aurelius’s quote: “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.” Except I cut off the last part—as a reminder that there isn’t even time to go through the whole quote.

But my real memento mori practice begins when I brush my teeth in the morning and when I brush them before bed in the evening. There, propped under my bathroom mirror, I have a chunk of an old Victorian tombstone. How it left that cemetery and came to be for sale, I don’t know and don’t want to know.

But I know that it sobers me and sets me right each time I look at it. Because the piece had just one word on it. It says, “Dad.”

Somebody who so identified with that word they wanted it on their tombstone; who lived and died and whose gravestone eventually even fell into disrepair. Who were they? How did they pass? Are they missed? Were they famous? It doesn’t matter. They are gone now. Almost certainly, they were gone too soon. They left behind a family. They will never walk or speak or love or cry again.

And so it will go for me. And so it will go for you.

I said before that this theme in art continues. One of the performance artist Marina Abramovic’s most interesting pieces features her lying on her back, completely nude, mimicking those ancient cadaver tombs. Laid on top of her in the exact same position is a female skeleton, representing… “the last mirror we will all face.” It is a beautiful, haunting reminder of the “before and after” that every single living body ultimately experiences. Marina’s piece has echoes of the Latin expression Hodie mihi, cras tibi. The skeleton is saying to the artist, “Today it’s me, tomorrow it’s you,”

We must remember, especially now, that life is ephemeral, that life is finite, that life is fragile. This should humble us… but also empower us.

It should put everything in perspective. When my son comes to the stairs and calls me to come play, I have no problem stopping because it could be the last time that he asks me. When I think about my work and phoning it in today I think about how lucky I am to have today. So I try to live—not just during a pandemic—with the awareness that I may not be spared. That a virus has no mercy. That it does not care about what I’ve built or who I am important to.

It doesn’t care about any of us. Death is indifferent, and it is ruthlessly, inevitably victorious.

That was the purpose of the once ever-prevalent memento mori art—to remind people that death is ever-present.

This could be your last day on this planet. As wonderful as it would be if there was no such thing as death, we have to use death as a tool, we have to use it as a spur to move us forward, we have to use it as a reminder of what’s truly important and we have to be made better for the fact that we don’t know how much time we have. We never do. And we never will.

Memento Mori.

The post You Must Stare This Scary Fact in the Face. appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

May 5, 2020

This Is What a Good Day Looks Like–According to Marcus Aurelius

It’s humbling to think that Marcus Aurelius, the head of the most powerful empire on earth, had the same amount of hours in the day as you.

Just 24.

So how did he get it all done?

How did he have time to be a king, a philosopher, a writer, a husband? To pass laws and judge cases? To lead troops into battle and guide Rome through a terrible plague? And do this while remaining good? Without being corrupted by the temptations or the stress of his position?

Well, routine had something to do it. He was a man of habit—all the Stoics were. They understood, as Aristotle did, that we are what we repeatedly do. That excellence is a habit.

For Marcus, the day started early. “At dawn, when you awake,” he wrote, “know that you are getting up to do the work of a human being.” There was no time to stay under the covers and stay warm.

It was early in the morning, we think, that Marcus did his journaling. He would spend a few minutes with the blank page, writing down his thoughts, clearing his mind, reminding himself of what was important.

Next, he prepared himself for the day to come. “The people you will meet today,” he said, “will be ungrateful and mean and shortsighted and frustrating.” But Marcus knew that he couldn’t let these people implicate him in their ugliness. He had to stick to what he knew was right.

It’s likely that Marcus tackled his most important tasks first. He didn’t believe in procrastination and wanted to tackle things when he was fresh. “Concentrate on what’s in front of you like a Roman,” he said. “Do it like it’s the last and most important thing in your life.”

From his stepfather, Antoninus, Marcus had learned how to work long hours—how to stay in the saddle. He writes in Meditations that he admired how Antoninus scheduled his bathroom breaks so he could work for long, uninterrupted periods.

Marcus didn’t shirk hard work. He did his duty. And he didn’t whine about it. “Never be overheard complaining,” he wrote, “not even to yourself.”

But what about stress? Marcus processed his stress by getting active. He regularly carved out time to hunt or ride on horseback. There are too many wrestling and boxing metaphors in Meditations for him not to have trained and regularly practiced those sports.

WATCH: Daily Stoic’s video on Marcus Aurelius’ daily routine

WATCH: Daily Stoic’s video on Marcus Aurelius’ daily routine

As a Roman, he also would have regularly frequented the baths. Some of these baths, located in Budapest, still exist. You could sit in the same hot and cold thermal pools in which Marcus would have “washed away the dust of earthly life,” as he put it. You can probably see why this would have been such an important part of his daily routine—getting clean. Having some quiet. Stepping away from his work for a minute. Invigorating the body with hot and cold or maybe even a massage.