Ryan Holiday's Blog, page 15

January 5, 2021

From America’s Oldest Veteran, Here Are 9 Lessons On Living

This article was originally published in February 2017. Richard Overton passed away on December 27th, 2018 at age 112 . R.I.P.

Richard Overton is the oldest living veteran in the United States. 110 years old. He was drafted at age 36 in 1942 at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. He fought in the Pacific—Hawaii, Guam, Palau and Iwo Jima—in World War II. He also happens to live down the street from me. Still.

When I saw online that he was having trouble affording the cost of an in-house nurse and care that would allow him to continue living at home (in the house he partly built with his own hands after returning from the war), I of course, donated and then I reached out to his third cousin to see if I might be able to come by and meet this great man.

There was a generation of Americans who used to sit on their porch and enjoy life as it happened. Richard is one of the last living members of that generation. Sitting on that porch with him, shooting the shit, I picked up a few things I wanted to share with you. He ate ice cream out of a coffee cup, I asked questions.

He humored me, I tried to be as little of a bother as possible. I won’t pretend we had a particularly deep conversation, though I think anything that comes out of the mouth of a person older than a century has a certain intrinsic wisdom to it.

I walked away that afternoon with a feeling of having experienced something very special. It made me hopeful, to be around a man who had seen and lived through so much and was still sitting there on his porch. It made me sad too (what would it have been like to have another 20 years with my own grandfather?). Mostly, I just wanted to share what I learned with you.

The man’s a treasure. I hope you’ll help keep him on that porch for as long as he wants to sit there.

Take It Day By Night

I asked Richard, other than God—he’s a faithful man—if he had a secret for living this long. “A secret? No, no secret,” he said. “Just live it.” Day by day?, I asked. He shook his head. At 110, day by day is too long. “Take it day by night,” he said.

Forget What The Doctors Say

Everyone I know that aspires to live for a very long time is obsessive about their health. Everyone I know that’s actually lived for a very long time doesn’t seem to think about it at all.

I realize that’s purely anecdotal but it’s hard to sit next to a man who has been alive 110 years old and still smokes 10 to 12 cigars a day and not think maybe it’s all a bit of a crapshoot. The man drinks his whiskey, smokes his cigars, eats his ice cream. He does what he wants. And he’s still here. Good for him.

It’s All Very Simple

How does it feel to be the oldest veteran? “Never think about it.” You seem very calm and relaxed. Have you always been that way? “Yes.” Do you think about dying? “Nothing I could do about it.”

Like I said, there is a certain sagacity to anything uttered by someone who has been alive that long. There is also a simplicity and a finality to the answers. A younger person would pontificate, would chatter, would argue this way or that way. Richard gives you his one-word answer.

Maybe it’s because he’s old and tired, but it just as easily might be the fact that after all those years complicated things become very simple. No reason to think about dying.

Of course you learn how to forgive people. Sure, he’s calm and relaxed, it’s the only way to be. A couple words is all you need when you’ve seen it all.

Just Sit There

I’ve mentioned Richard’s porch a couple times. It’s a wonderful thing. In East Austin, they’re tearing down most of the old houses and building cool looking new ones.

You know what they’re not putting back on them? Porches.

You can’t even see the street from my house; the builder put a 10 foot fence around the whole thing. But Richard spends four or five hours a day out on his, on a chair he refers to as his throne.

He showed me the railing that rings the porch and the waist-high plants which go around it. Want to know why they’re there, he asked? It was because women used to wear skirts and he wanted them to be able to sit comfortably and privately.

The man just enjoys life on that porch, enjoys the present moment, maybe remembers the past a little. I asked him what he thinks about up there. “Different things,” he said. “I look at the trees.” I did too. It was nice.

History Is Very Short

It’s fascinating to think that when Richard was born, Theodore Roosevelt was president. Overton is the oldest living American veteran now, but when he was born, Henry L. Riggs was still alive.

Riggs was a veteran of the Black Hawk War (1832) and he was born in 1812… and Conrad Heyer, the Revolutionary War veteran and the oldest and earliest person to be photographed (born in 1749) was still alive when Riggs was born. Three overlapping lives: that’s all it took to get back to before even the idea of founding the United States.

Richard’s brother fought in the first World War. He told me he remembered seeing Civil War veterans around when he was a kid. Not many, but they were there. It was Texas—those men fought to keep his mother in slavery. How long ago all that horribleness seems.

How recent it is at the same time. I’m bringing my son over to meet Richard soon. He’s three months old. I want him to shake hands with a man who walked the earth when TR was in the Oval Office, who shook hands with Obama, who lived through the Spanish influenza, who stepped foot on more Japanese islands than he should have had to, who came home after fighting for this country and had to put up with segregation, who bought a house for $4,000 and lived in it for 70 years (it’s now worth more than 100x that), who worked for some of the most famous governors in Texas (Ann Richards was his favorite), who at 110 is still going strong.

A Wise Man Knows Nothing

Another observation about really old people: They’re never the ones that try to tell you what to do. A 40-year-old will stop a stranger on the street and tell them to pull up their pants or remind a young woman she needs to smile more.

An octogenarian and beyond just lets people do what they do. I asked Richard if he had any advice for young people: “I don’t know.” I asked him again later, “Never get in trouble.” They say that Socrates was wise because he knew how little he knew. I think that’s the real lesson in aging, a certain humility and indifference.

An acceptance of other people, that they’ll find their own way and they don’t need your moralizing. Besides, staying alive is a full time job.

Know What You Like (And Hold Onto It)

I mentioned it above, but Richard has been living in the same house in Austin since coming home at the end of World War II. He refuses to leave, either—he likes it there.

He’s got a couple of old cars in the driveway too. Knowing what you like is the first step to wisdom and old age, said Robert Louis Stevenson. There’s something comforting in the thought of Richard being happy and active in his community, enjoying life and sitting on the same porch for over seven decades.

In an age that promotes constant change, Richard’s message in a way is the opposite. Find what you like and stick with it.

Community Is the Key to Everything

Richard pointed across the street—the cactus, he planted that. The porch across the street? He helped build that. The electrical pole on the corner—it used to have an unsafe number of houses connected to it until he called and called and the power company finally fixed it.

He told me the story of a woman who fell into the cactus and how he helped her out and helped her pull out the thorns. A woman drove by while we sat there and waved. For over half a century, he’s been a watchdog in that neighborhood, helping people, making it better.

Now that he’s outlived nearly every relative on earth, the community is helping take care of Richard. His third cousin—do you even know your third cousin, would they help you?—comes by almost everyday to sit with him and talk.

His third cousin is the one who is keeping Richard in his home and looking out for him. That’s community. That’s family.

Enjoy the Absurdity of Life

The most animated Richard ever got was when he told me a story about the enormous pecan tree in his front yard. It seemed like an ordinary tree to me, until he told me his dog planted it seventy years ago. They had a pecan tree in the back, and the dog would grab the nuts and bury them in the front yard.

With glee, Richard told me how eventually the tree grew and now it’s so big it’s nearly pushing up the foundation of his house. He loved the absurdity of it—a dog planting a tree! He was laughing at it still, seven decades later. The philosopher Chrysippus supposedly died laughing at a donkey eating his figs.

It occurred to me that it wouldn’t be a bad way for Richard to go someday either, sitting on his porch, thinking about his dog, laughing at the tree that’s going to outlast all of them, and many of us.

It’s a shame on this nation to me that Richard Overton, at 110 years old and as our oldest living veteran, is having to ask for money on the internet to stay in his home and pay for medical care.

Who doesn’t agree that our oldest living hero deserves to be taken care of?

It’s been my belief that America has always been great and it’s great because of men like Richard. It’s great because when his third cousin created a GoFundMe campaign, thousands of people do show up to help. But they shouldn’t have to.

Richard and his family shouldn’t even have to ask. (I’ll ask for them though: Please keep helping!)

But I don’t want to end this on a negative note. Because political dysfunction aside, Richard is still here and he doesn’t look like he is going anywhere. I was lucky to meet him and learn from him. I hope I’ve been able to pass along a little of what that was.

I have no idea how long I will live for, or what old age will look like for me, but I feel more connected to the past after meeting Richard. I could feel his wisdom and his energy and am better for it. Meeting him was one of the treats of my life.

So I’ll end this piece by thanking him—for that—and for what he’s done for the rest of us the 110 years he has been on this planet.

The post From America’s Oldest Veteran, Here Are 9 Lessons On Living appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

December 29, 2020

The Secret to Better Habits in 2021

There’s nothing like a global pandemic to obliterate your habits.

When you’re locked in your house, working from home, when your routine is disrupted, when everything that’s happening in the world seems to be negative, it’s easy to say screw it. Or, it’s easy to tell yourself—as I wrote about recently—that you’ll get back on track when things go back to normal.

It’s understandable. It’s widespread. We’ve all made compromises in the last year—we’ve had to. The problem is the promises we’ve made to rationalize those decisions, to keep them going even though we know they aren’t serving us well.

I’ll start eating salads for lunch when I’m back at the office. I’ll stop snacking when the kids are back on a schedule. I’ll get back to working out when I can safely go to the gym. I’ll get off social media when there is less news to follow—then, I’ll start reading books again.

The Stoics—who survived their own plagues and exiles and moments of crisis—knew that this was no way to live. How much longer are you going to wait, Epictetus would ask? You could be good today, Marcus Aurelius reminded himself, but instead you choose tomorrow.

Now is now. Now is the time to live well, to bring arete (excellence and virtue) into our lives. To make it a habit. We all want better habits—and if we want to be better people, we’ll have to have better habits. And as we start a new year, there’s never a better time.

Think Small

One of the best pieces of advice from Seneca was actually pretty simple. “Each day,” he told Lucilius, you should “acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes, as well.” Just one thing. One nugget. This is the way to improvement: Incremental, consistent, humble, persistent work. Your business, your book, your career, your body—it doesn’t matter—you build them with little things, day after day. Epictetus called it fueling the habit bonfire. The filmmaker, entrepreneur, author, former governor of California, professional bodybuilder, and father of five Arnold Schwarzenegger gave a similar prescription for people trying to stay strong and sane during this pandemic: “Just as long as you do something every day, that is the important thing.” Whether it’s from Seneca or Epictetus or Arnold, good advice is good advice and truth is truth. One thing a day adds up. One step at a time is all it takes. You just gotta do it. And the sooner you start, the better you’ll feel… and be.

Think Long-Term

In his book Atomic Habits, James Clear talks about something he calls “The Plateau of Latent Potential.” This plateau can be likened to bamboo, which spends its first five years building extensive root systems underground before exploding 90 feet into the air within six weeks. Or to an ice cube, which will only begin to melt once the surrounding temperature hits 32 degrees (or the resulting water that only boils at 212 degrees). Just because it sometimes takes longer than we’d like to see the results of our efforts doesn’t mean that our efforts are going to waste. In fact, most of the important work—the build up—won’t seem like it’s amounting to anything, but of course it is. Plutarch tells the story of Lampis, a wealthy ship-owner who was asked how he accumulated his fortune. “The greater part came quite easily,” Lampis supposedly answered, “but the first, smaller part took time and effort.” Any goal we have will take time and effort to accomplish, and beginning it will most likely be harder than finishing. But we have to keep going, because habits and hard work compound. Remember always that greatness takes time. Most importantly, remember what Zeno said: that greatness “is realized by small steps, but is truly no small thing.”

Develop the Muscle

As part of one of the Daily Stoic challenges, I quit chewing gum. Gum is probably the least bad habit you could possibly have. But I wanted to flex the muscle; I wanted to prove that I could quit something just for the sake of quitting it. And every time I see gum, or I think about wanting to have gum but don’t give in—that helps reinforce for me that I’m the kind of person that can decide to stop doing things that I don’t want to do anymore. So if you want to become a person that can do something hard like giving up alcohol, start by doing something easy like giving up gum. The logic applies to good habits. If you want to become a person that writes books, for instance, start by becoming a person that writes in a journal for 15 minutes every morning. As Epictetus said, “Capability is confirmed and grows in its corresponding actions, walking by walking, and running by running… therefore, if you want to do something, make a habit of it.” There is nothing more powerful than a good habit, nothing that holds us back quite like a bad habit. We are what we do. What we do determines who we can be. So if we want to be happy, if we want to be successful, if we want to be great, we have to develop the capability, we have to develop the day-to-day habits that allow this to ensue.

Use Good Habits to Drive Out Bad Habits

When a dog is barking loudly because someone is at the door, the worst thing you can do is yell. To the dog, it’s like you’re barking too! When a dog is running away, it’s not helpful to chase it—again, now it’s like you’re both running. A better option in both scenarios is to give the dog something else to do. Tell it to sit. Tell it to go to its bed or kennel. Run in the other direction. Break the pattern, interrupt the negative impulse. The same goes for us. As Epictetus said, “Since habit is such a powerful influence, and we’re used to pursuing our impulses to gain and avoid outside our own choice, we should set a contrary habit against that, and where appearances are really slippery, use the counterforce of our training.” When a bad habit reveals itself, counteract it with a commitment to a contrary virtue. For instance, let’s say you find yourself procrastinating today—don’t dig in and fight it. Get up and take a walk to clear your head and reset instead. If you find yourself cutting corners during a workout or on a project, say to yourself: “OK, now I am going to go even further or do even better.”

Build A Routine

It’s strange to us that successful people, who are more or less their own boss and are clearly so talented, seem prisoners to the regimentation of their routines. Think about Jocko Willink waking up at 4:30 a.m. every morning. Isn’t the whole point of greatness that you’re freed from trivial rules and regulations? That you can do whatever you want? Ah, but the greats know that complete freedom is a nightmare. They know that order is a prerequisite of excellence. They know that in an unpredictable world, a good routine is a safe haven of certainty. They know that when you routinize, disturbances give you less trouble… because they’re boxed out—by the order and clarity you built. Well, it’s when things are chaotic and crazy, when the world feels like it’s falling apart—this is when we need routine more than ever. Follow the kind of routine that Marcus Aurelius followed every day (like I detail in this video) or the practice that Seneca followed with his evening journaling. Get up early. Be deliberate. Exercise. Set up and stick to a diet. Create limits and order. Clean your house. Attack problems or projects that have piled up. Eisenhower famously said that freedom was properly defined as the opportunity for self-discipline, and so it is with disorder—it’s an opportunity to create order.

Use Incentives

Around the time I wanted to become someone who spends less time on their phone, I was invited to a challenge on the habit-building app SPAR!, which is basically the most addictive and rewarding app I’ve ever downloaded, to not touch my phone for at least 10 minutes after I woke up. I’d been sleeping with it in the other room for years, but I still usually grabbed it first thing in the morning. The challenge came with a powerful incentive — each time I failed, I’d have to pay $10. At first you do the daily deed just so you don’t lose money. But the real draw was that it meant I could focus on being present with my son in my first waking moments. Soon, I started challenging myself to stretch 10 minutes into 30, then 45, then an hour. Now some mornings, if I am writing, I might not touch my phone until lunch. On those days, I’m happier and more productive.

Put Up Reminders

I’m not sure where I stole the idea from, but I’m a big proponent of printing out good advice and putting it right in front of your desk, or wherever you work everyday. So you cannot run from the advice, so you see it enough times that it becomes imprinted in your mind. The first quote I ever did this with was an admonishment from Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. I was 19 years old and it was exactly what I needed to be told—it was how I reminded myself to get off my ass, to stop being lazy, and to work hard. Now, over my desk I have a picture of Oliver Sacks. In the background he has a sign that reads “NO!” that helped remind him (and now me) to use that powerful word. If you walk into the locker room of any professional sports franchise or elite D-1 level program, you’ll see the walls are tattooed with precepts and reminders (The Pittsburgh Pirates even have “It’s not things that upset us, it’s our judgement about things” in their clubhouse in Florida. Iowa football has “Ego Is the Enemy” in their weightroom.”) On the Daily Stoic podcast, I asked 2x NBA champion and 6x All-Star (and fan of Stoicism) Pau Gasol about the role these precepts play in sports:

Athletes appreciate pointers and directions. Quotes kind of hit home, as far as there’s a message, like “Pound the rock.” As far as resilience, you just keep pounding the rock. That was a big one for the spurs. Just keep pounding the rock. If you hit it a thousand times or two thousand times, you might not see a crack, but it’s that next hit, that next pound where the rock will crack. You just got to keep at it, keep at it, keep at it. So pound the rock. It’s something that a lot of other coaches have acquired and then shared in their locker rooms.

Reminders are powerful. They make you better. They give you something to rest on—a kind of backstop to prevent backsliding.

Choose Your Surroundings Wisely

Who we are surrounded by influences more than any other factor, who we will become. Goethe once said “Tell me who you spend time with and I will tell you who you are.” As Seneca wrote, “Even Socrates, Cato, and Laelius might have been shaken in their moral strength by a crowd that was unlike them; so true it is that none of us, no matter how much he cultivates his abilities, can withstand [the influence of their surroundings.]” We seem to understand that a young kid who spends time with kids who don’t want to go anywhere in life probably isn’t going to go anywhere in life, either. What we understand less is that an adult who spends time with other adults who tolerate crappy jobs, or unhappy lifestyles is going to find themselves making similar choices. Same goes for what you read, what you watch, what you think about. Your life comes to resemble its environment (Ben Hardy calls this the proximity effect). So choose your surroundings wisely.

Hand Yourself Over to a Script

In 2018, we did our first Daily Stoic Challenge, full of different challenges and activities based on Stoic philosophy. It was an awesome experience. Even I, the person who created the challenge, got a lot out of it. Why? I think it was the process of handing myself over to a script. It’s the reason personal trainers are so effective. You just show up at the gym and they tell you what to do, and it’s never the same thing as the last time. Deciding what we want to do, determining our own habits, and making the right choices is exhausting. Handing the wheel over to someone else is a way to narrow our focus and put everything into the commitment. That’s why Whole30 is so popular. You buy a book and follow a regimen, and then you know what you’re doing for the next month.

To kick off 2021, we’re doing another Daily Stoic Challenge. The idea is that you ought to start the New Year right—with 21 great days to create momentum for the rest of the year. If you want to have better habits this year, find a challenge you can participate in. Just try one: it doesn’t matter what it’s about or who else is doing it.

Keep Going Back to It

The path to self-improvement is rocky, and slipping and tripping is inevitable. You’ll forget to do the push-ups, you’ll cheat on your diet, you’ll get sucked into the rabbit hole of Twitter, or you’ll complain and have to switch the bracelet from one wrist to another. That’s okay. It doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. I’ve always been fond of this advice from Oprah: If you catch yourself eating an Oreo, don’t beat yourself up; just try to stop before you eat the whole sleeve. Don’t turn a slip into a catastrophic fall. And a couple of centuries before her, Marcus Aurelius said something similar:

When jarred, unavoidably, by circumstance, revert at once to yourself, and don’t lose the rhythm more than you can help. You’ll have a better group of harmony if you keep on going back to it.

In other words, when you mess up, come back to the habits you’ve been working on. Come back to the ideas here in this post. Don’t quit just because you’re not perfect.

—

No one is saying you have to magically transform yourself in 2021, but if you’re not making progress toward the person you want to be, what are you doing? And, more important, when are you planning to do it?

As Epictetus famously said 2,000 years ago: “How long are you going to wait before you demand the best for yourself?” He’s really asking, how much longer are you going to wait until you demand the best of yourself? How much longer are you going to wait to start forming the habits that you know would be responsible for getting you to where you want to go?

With that, I’ll leave you with Epictetus once more. It’s the perfect passage to recite as we set out to begin a new year, hopefully, as better people:

From now on, then, resolve to live as a grown-up who is making progress, and make whatever you think best a law that you never set aside. And whenever you encounter anything that is difficult or pleasurable, or highly or lowly regarded, remember that the contest is now: you are at the Olympic Games, you cannot wait any longer…

There’s only 24 hours left to sign up to join me in the Daily Stoic New Year, New You Challenge .

New Year, New You is a set of 21 actionable challenges—presented one per day—built around the best, most timeless wisdom in Stoic philosophy. Each challenge is specifically designed to help you:

Stop procrastinating on your dreams

Learn new skills

Quit harmful vices

Make amends

Learn from past mistakes

Have more hope for the new year

And much much more…

21 challenges designed to set up potentially life-changing habits for 2021 and beyond.

There are over 30,000 words of exclusive content that I don’t post anywhere else. Each day also has an audio companion from me, weekly group Zoom calls, a Slack channel for accountability, and a lot more.

It’s one of my favorite things I do each year and really enjoy interacting with everyone in the challenge. Click here to learn more .

The post The Secret to Better Habits in 2021 appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

December 22, 2020

The (Very) Best Books I Read in 2020

We are doing a 2021 New Year New You Challenge . Please join us !

Man. What a year.

There’s not much you can say about 2020 that doesn’t include some curse words, but I will say this: It provided plenty of time for reading. It provided plenty of things that needed to be read about—from leadership to pandemics to civil rights to elections—this was one of those years that sends you to… well, I would say “the bookstore,” but that was hard, too.

Anyway, I read a lot. As I’m sure you did too.

Every year, I try to narrow down all the books I have recommended and read for this email list to just a handful of the best. The kind of books where if they were the only books I’d read that year, I’d still feel like it was an awesome year of reading. (You can check out the best of lists I did in 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012 and 2011.)

My reading list is now ~250,000 people, which means I hear pretty quickly when a recommendation has landed well. I promise you—you can’t go wrong with any of these.

The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History by John M. Barry

There is something surreal about reading a book published 15 years ago about an event 100 years ago that just happens to nail exactly what’s happening in this moment (his book Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How it Changed America is also good and equally timeless.) Barry’s haunting book covers in definitive, gripping detail the Spanish flu: a global pandemic which staggered nations and cities and the brightest medical minds of the time. “It’s only the influenza,” confident officials repeated. “It’ll be over soon,” they reassured. And then the President of the United States caught it… (I’m talking about Woodrow Wilson, of course). Because the more things change, the more they stay the time. Because history is the same song happening on repeat. Anyway, reading this book at the beginning of the pandemic was not only educational, but it has helped shape my family and businesses’ responses to the crisis. Barry writes of the relief people felt when the Spanish flu seemed to be winding down. They thought it was over, but actually only the first wave was done. “For the virus had not disappeared. It had only gone underground, like a forest fire left burning in the roots, swarming and mutating, adapting, honing itself, watching and waiting, waiting to burst into flame.” You cannot relax yet. You cannot drop your shield, as the Spartans would say. You must continue to protect the line. The health of your neighbors depends on it. And I joked in February that I was deliberately not going to read The Road by Cormac McCarthy this book because of the pandemic. In truth, I got it down from my shelf and sat on my bedside table while I worked up the courage to read it again. My feelings were well-founded, because on the night I finished, all I could do was walk quietly into my son’s room and sob while he slept. The Road is just one of the most beautiful and profound depictions of struggle and sacrifice and love ever put down on the page. Worth reading again!

Leadership: In Turbulent Times by Doris Kearns Goodwin

This is an absolutely incredible book. I think I marked up nearly every page. The book is a study of Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, FDR and Lyndon Johnson, and it is so clearly the culmination of a lifetime of research… and yet somehow not overwhelming or boring. Distillation at its best! I have read extensively on each of those figures and I got a ton out of it. Even stuff I already knew, I benefited from Goodwin’s perspective. This is the perfect book to read right now—a timely reminder that leadership matters. Or as the Stoics say: character is fate. Or as I wrote about in this piece about leadership during the plague in ancient Rome: when things break down, good leaders have to stand up. After Goodwin, I picked up Leadership in War: Essential Lessons from Those Who Made History by Andrew Roberts, who I find to be funny, insightful and quite good at capturing the essence of unique historical figures. I also recommend Roberts’ biographies of Churchill and Napoleon (you can listen to my interview with Roberts here). As I said, now is the time to get perspective and to learn from the past.

Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch

I’ve raved about some of my favorite epic biographies before: Robert Caro’s LBJ, William Manchester’s Churchill, Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, Well, add another to the list. Taylor Branch’s definitive series on Martin Luther King Jr. and the American civil rights movement has not only been riveting, eye-opening and humbling, it’s been the perfect vehicle to help me understand what’s happening in the world right now. I finished Parting the Waters and immediately picked up Volume II, Pillar of Fire. I’ve come to believe that one of the best ways to become an informed citizen in the present is not to watch the news, but to read history. The actor Hugh Jackman said in an interview a few months ago that he’s been getting his news by keeping his eye on the big picture—going through the Ken Burns catalog and reading books like Meditations. “That’s the way you should understand events and humanity,” he said, “with that sort of 30,000-foot view.” If you want to understand what’s happening in the United States right now as it pertains to race, get off Twitter and read these books. On that note, I re-read Invisible Man, first published in 1952, in light of the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. There are many “anti-racist” reading lists floating around, but how many of the books on those lists will still be readable in 70 years? Do yourself a favor and read this. It’s not going anywhere because it is timeless—and sadly, very timely. I also learned so much from Edward Ball’s Life of a Klansman (and when I interviewed him) and just as much from Albion W. Tourgee’s A Fool’s Errand (Albion was one of the legal advisors in Plessy v. Ferguson). Strongly recommend one or both of these books to anyone who wants to become better informed instead of more partisan. My study of this history has been ongoing, but I feel I have learned far more these books than I have from the trendy white fragility books going around. Also if you’re interested, here’s a step I have taken in regards to Confederate monuments (that is: literal white supremacy monuments, as you’ll learn in these books and some of my interviews on the topic) in my town.

More…

I really can’t leave it at just three books. I loved Cecil Woodham Smith’s books, Florence Nightingale and The Reason Why: The Story of the Fatal Charge of the Light Brigade. I loved Julian Jackson’s biography of de Gaulle and McCullough’s biography of Truman. I loved even more Wright Thompson’s The Cost of These Dreams. The best thing I read about writing was Steinbeck’s Journal of a Novel. The best two bits of philosophy I read were Plutarch’s How to Be a Leader and Carlin Barton’s Roman Honor: The Fire in the Bones (an expensive primer on the Stoics, really—but very good). As far as kid’s books goes, we read The Scarecrow together many times. Every night we read A Poem for Every Night of the Year (edited by Esiri Allie). We’ve also done several tours through the stories in Fifty Famous Stories Retold by James Baldwin. Finally, I spent a lot of time with Marcus Aurelius during the pandemic… because he himself lived through one. The big thing I took away, which pertains to so much of what’s in these books: “You can commit injustice by doing nothing. “Be free of passion but full of love.” “No, it’s not unfortunate that this happened, it’s fortunate that it happened to me.”

Of course, I also put out a book this year, Lives of the Stoics , which debuted at #1. I also released a box set of The Obstacle Is the Way , Ego Is the Enemy and Stillness Is the Key . You can get them anywhere books are sold OR we have signed, personalized editions in the Daily Stoic store . They make great gifts!

But most importantly, I hope you join me in the Daily Stoic New Year, New You Challenge .

New Year, New You is a set of 21 actionable challenges—presented one per day—built around the best, most timeless wisdom in Stoic philosophy. Each challenge is specifically designed to help you:

Stop procrastinating on your dreams

Learn new skills

Quit harmful vices

Make amends

Learn from past mistakes

Have more hope for the new year

And much much more…

21 challenges designed to set up potentially life-changing habits for 2021 and beyond.

There are over 30,000 words of exclusive content that I don’t post anywhere else. Each day also has an audio companion from me, weekly group Zoom calls, a Slack channel for accountability, and a lot more. It’s one of my favorite things I do each year and really enjoy interacting with everyone in the challenge. Click here to learn more .

The post The (Very) Best Books I Read in 2020 appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

December 15, 2020

There Is No Such Thing as Normal— So Stop Waiting for It

We’ve heard it.

We’ve said it.

When things go back to normal.

I found myself thinking that this very morning as I took my sons for our morning walk. How much longer is it going to go on like this?

It’s understandable of course. This all feels very strange. A pandemic that has disrupted our lives. Everything seems so polarized. The election is still being contested. This is not how stuff usually is, right?

But of course, that’s not true at all. Any student of history knows that 2020 is hardly abnormal.

A hundred years ago we had a pandemic much worse than this one…in the middle of a world war. We had a great depression after that. There was a pandemic in the ‘50s. In ‘68, not only were there massive civil rights protests and riots, but there was also a flu pandemic that killed some 100,000 people in the U.S. and over a million across the globe. In fact, I defy you to find me a single “normal” decade in American history.

The last two decades have hardly been peaceful and simple. They began with a contested election and legal challenges. They were followed by a terrorist attack that left 3,000 dead. Then we had a financial crisis on par with the Depression. Now here we are, simultaneously facing a pandemic, a nationwide protest movement, and an economic crisis.

The Stoics were fond of quoting Heraclitus: the only constant is change.

It’s true, but the funny thing is that even change seems to rhyme with itself, if not outright repeat.

As the Bible tells us, “The thing that hath been,” we read in one part, “it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun… That which hath been is now; and that which is to be hath already been; and God requireth that which is past.”

Did Marcus Aurelius read Ecclesiates? Or did he discover for himself that, “Whatever happens has always happened and always will, and is happening at this very moment, everywhere. Just like this.”

“Time is a flat circle,” Rustin Cohle says in the first season of True Detective. “Everything we have done or will do we will do over and over and over again forever.” And so it was that another generation found out about Nietzche’s idea of “eternal recurrence.” Did Nietzsche read Marcus? Did Nic Pizzolatto read Nietzsche? Or Marcus? Or Ecclesiastes?

Or is this realization just something you can’t help but pick up if you’re paying attention?

It’s interesting to observe that Marcus’s reign was not really that different from the reign of Vespasian. It was filled with people doing the same things: eating, drinking, fighting, dying, worrying, and craving. Can you imagine if, during the crises he faced, he chose to “just wait for things to go back to normal” instead of doing, well, anything?

Everything that happens is normal. There is nothing unusual about any of this.

Life is life. The only surprise is that we’re surprised.

Sure, you’d rather not be working from home. You’d love to be traveling freely. Maybe you would like anyone to have been president rather than Donald Trump. But who is to say having or not having these things is “normal?”

And you can’t just wait them out.

Because what you’re waiting to end…is life. It’s now. It’s the present moment.

One of the reasons to study history is that it gives you perspective. Distance has the effect of sanding down the edges and smoothing the transitions between things. When you read about the Great Influenza, when you immerse yourself in the characters of Shakespeare, when you visit a Civil War battlefield or an ancient castle, you gain a better understanding of how similar the past was to the present. How the more things change, the more they stay the same—how our petty plans and projections have very little impact on the tides of time. There’s nothing to take personally.

It just is.

History is violent. History is hard. History is confusing and overwhelming. History didn’t care about the people who had to live through it. History is like this because history is just a recording of life, and life is like that.

But does that mean we can’t have peace or happiness within this chaos? That because there is no such thing as “normal” we should be anxious and depressed?

On the contrary!

I remember once reading a book about the archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann—the adventurer who found the lost city of Troy. In the 1860s, he immigrated to America and worked his way across the country on a variety of jobs. It was incredible to notice that this guy had lived through the Civil War, which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, and it never even appeared in his diaries or changed his plans. He had found his own personal normal inside the craziness of world events. He’d simply gone on with his life.

In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera writes, “No matter how brutal life becomes, peace always reigns in the cemetery. Even in wartime, in Hitler’s time, in Stalin’s time, through all occupations… against the backdrop of blue hills, they were as beautiful as a lullaby.”

That’s what I came to realize on my walk this morning. Yeah, this time is weird. It’s maybe not what I’d want, if I had a choice. But I don’t have a choice, because this is just life.

Why should I pine for it to be over or different? What matters is right now. What matters is the quiet hour we had together on that road. What mattered was the sunrise coming up behind us. What matters is that the last eight months have been eight months of being alive—and I chose to live them.

How much longer will it be like this? How much longer until the next change?

No one can say. Nobody knows anything for certain except that change will eventually come.

If people could manage to find happiness and purpose and stillness amidst war, under the rule of tyrants, through plagues far worse than this one, what excuse do we have?

None. This is normal.

This is life.

Accept it and love it.

The post There Is No Such Thing as Normal— So Stop Waiting for It appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

December 8, 2020

25 Things I’ve Learned From a Decade of Podcasts

In his letters—the pre-digital medium for distant long-form conversation—Seneca instructs his friend Lucilius to find one thing each day that will fortify him against death, despair, fear, or adversity. Just one thing. One nugget. And that’s what most of Seneca’s letters to his friend are about. They have a quote in them. Or a little prescription. Or a story. But in each case, Seneca is explicit. Here’s your lesson for the day, he says. Here’s your one thing.

Obviously that’s the logic behind the daily emails I write (Daily Stoic and Daily Dad) but it’s also the way I try to live. Every time I listen to a podcast or record one myself, I try to walk away having grabbed at least one little thing. That’s how wisdom is accumulated—piece by piece, day by day, book by book, podcast by podcast.

So today, I wanted to honor that Stoic process by sharing some of the lessons I’ve picked up over a couple thousand hours of listening to podcasts, being interviewed on podcasts, and interviewing people for the Daily Stoic podcast (which you can subscribe to here and here). And with over 30 million downloads of Daily Stoic’s episodes so far, I get really excited to think about how much cumulative knowledge that’s created for people.

But here’s some top-line stuff you can use right now:

***

Interviewing is a skill like any other. It seems easy—aren’t we all good at having conversations? No we are not! I’m always looking to see masters at work and I try to learn from them when I get a chance to watch. Trying to myself, and seeing how hard it was, has been a great lesson.

Brian Koppelman’s podcast is called The Moment. It’s about the critical moment in every aspiring artist’s life. When the craft they have long elevated as magic or beyond their grasp suddenly becomes a bit more comprehensible. When they begin to see the medium in a new way. When they realize that on the other side of the work they admire and love is just another human being. And I’m a human being too—which means that if I work hard enough, I can do the same thing. I wrote about my moment here.

What should a person do after they screw up? What can they do? It occurred to me when I was asked to be on Lance Armstrong’s podcast a couple years back. What does Lance call his podcast? He calls it The Forward. Because that’s really the only thing you can do in life: go forward. That’s what Lance is trying to do with his life now. You don’t have to like him. You don’t have to forgive him. But move on and move forward, is all he can do.

It’s not fair. When I interviewed Tim Ferriss for the Daily Stoic podcast, he advised that we strip those three words out of our vocabulary. Because they are impotent and meaningless. Because they don’t do anything but make us upset or make us believe we don’t have options. We talked about that Epictetus line, “It is not things that upset us, but our judgements about those things.” “Fair” is an opinion we have about an objective reality we’re in.

Also from Tim. Tim has always stressed the value of evergreen long-form content. As he told me in my interview with him, “Long-form content isn’t dead; it’s simply uncrowded and neglected. I double-down when formats are out of favor.”

Matthew McConaughey told me why he shut down his production company and his music label. “I was making B’s in five things. I wanna make A’s in three things.” Those three things: his family, his foundation, his acting career.

Another from McConaughey. He told me he’s known in Hollywood as “a quick no and a long yes.” What a great expression! Before he says yes to doing a movie, he sleeps on it for ten days to two weeks in the frame of mind that he’s not going to do it. If he sleeps well, he doesn’t do it. If the thought that he has to do it wakes him up at night, he does it.

An amazing chat with James Altucher on his podcast inspired my piece on envy and jealousy and a thought exercise I still do. We’re usually envious of certain aspects of a person’s life. Instead, picture that you can change places with them in every way. Would you? The answer is always no. You gotta stay on your path. Don’t be distracted by others.

The legendary basketball coach George Raveling told me he sees reading as a moral imperative. “People died,” he said, speaking of slaves, soldiers, and civil rights activists, “so I could have the ability to read.” If you’re not reading, if books aren’t playing a major role in your life, you are betraying the legacy that they left for the generations after them.

An essential piece of advice I got from the author Steven Pressfield: There are professional habits and amateur ones. Which are you practicing? Is this a pro or an amateur move? Ask yourself that. Constantly.

I asked Jocko Willink what his advice would be for someone reeling from the events of the pandemic. “Really, it just comes down to having humility.” People who accept reality can change and adapt. People who let their ego get out of control and deny the severity? Those are the people he’s been seeing get their asses kicked.

Just a few more years, we tell ourselves. Just until I make enough money. These are the lies we all tell ourselves, the rationales for why we’re doing the thing we hate or being the kind of person we’d rather not be. The brilliant comedian and writer Pete Holmes called it the lie of the “One Last Job.” It’s the lie that bank robbers tell themselves, just as comedians or musicians do—one more tour, one more album, then I’ll slow down. But it never happens. You could leave life right now, Marcus Aurelius reminds us. We have to let that determine what we do and say and the jobs we take and the work we do.

Pop star Camila Cabello talked about that metaphor from Stillness about looking at the human race as a single person and yourself as an individual part of that person. Just like it’s not the hand’s job to be the best eye, Camilla said, “It’s not everybody’s job to be number one. It’s just your job to be you. The world needs you to be you.”

Wright Thompson’s book The Cost of These Dreams was one of the books I recommended everyone should read in 2020. I liked his line in our interview, “It’s over now—was it worth it?”

I was surprised to hear Olympic gymnast Dominique Dawes say that she doesn’t miss or reminisce on being at the Olympics or standing on the podium. “When I dream about exciting moments and memories in my life, those don’t come up… It’s those moments with your family. It’s those moments with your spouse. It’s those moments knowing you planted an amazing positive seed in a stranger’s life. Those are the moments that fulfill us.”

I asked one of my favorite writers, Rich Cohen, about how he’s able to be so consistently productive at such a high level. He said he approaches a big project like he approaches a cross-country road trip. “The way you deal with long road trips is you set yourself a minimum number of hours a day, no matter how you feel.” The point is that “not much” adds up if you do it a lot. That what Zeno said too: “Well-being is realized by small steps, but is no small thing.”

The great basketball coach Shaka Smart said something similar. He tells his players not to figure out their priorities, but to figure out their priority. “The root of the word ‘priority’ is singular… It was a singular word—the one thing. In modern times, we’ve turned it into ‘priorities,’ but then all of a sudden it turns into eight, ten, 15 things and that defeats the purpose.” Just do one high-quality thing every day, he said; it adds up.

Another great basketball coach, Buzz Williams, told me that he keeps a list of what-ifs. Ten times a day, he asks himself, “What if?” What if the college basketball season is canceled? What if we can’t travel for recruiting? What if I experimented with a new routine? “The what-if scenarios force me to think how I can be prepared no matter which way this all unfolds. Because on the other side of this… the people who are going to be the most successful are the ones that can pivot the quickest.”

One of the first greek words I ever came across was in a lyric of a MxPx song: “First step to Kairos is to take the shells out of our eyes.” I’ve always wondered, what the hell does that mean? I finally got to ask MxPx singer and songwriter Mike Herrera, what the hell does that mean? It’s his spin on the biblical line about hypocrites: “First take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the splinter out of your brother’s eye.”

We do a bad job imagining ourselves on the other side of the judgment we swiftly render against other people. As Billy Bush told me, “We have to be able to fail. We have to tell our children, ‘It’s OK to fail and to not be at your best and to screw up, and then build yourself back up.’ People have to allow other people to do that. It’s not sustaining to not allow people to do that because, at some point, it’s going to be you looking for that welcoming, empathetic embrace.”

Along similar lines, Rich Roll said, “It’s only through weathering obstacles and grappling with difficulties and you know making mistakes that we truly learn who we are and as a consequence grow.” (Or the obstacle is the way …)

Austin Kleon talked about being a parent: “You have to be the kind of man that you want them to be. You have to become the kind of human being that you want them to become.” Marcus Aurelius was talking about being a human being: “Waste no more time arguing what a good man should be. Be one.”

I loved what the philosopher Quill Kukla said on Tyler Cowen’s podcast about why they love boxing: “From a philosophical point of view, why is boxing good for me? I think philosophers who only do philosophy and nothing else tend to be bad, boring philosophers… I think that if you just do philosophy, you literally don’t have material… Imagine if you were a stand-up comic, and all you did is sit there and try to write comedy all day long. You wouldn’t have any material.”

Danica Patrick talked about the surreal reality that’s been her life as an international celebrity. “It made me realize that the stuff that we see—the celebrities, the magazines we pick up—we just think, ‘Oh, they’re famous.’ No, they’re being made famous. Somebody’s paying for that… So early on, I realized that there’s a lot of bullshit out there. And that there’s an agenda behind everything.” This is something I try to remember whenever I see someone getting attention and wonder, “Why am I not getting that?”

One of the great perks of my life is getting to have regular conversations with one of the great writers of our time, Robert Greene. We recently decided to record one of those conversations. I asked him about what I think is the thread through all his books, something which is also in short supply these days: an unflinching commitment to reality, even when it’s inconvenient. “Whenever I hold a belief, or I’m writing a book,” Robert explained, “I always start with the premise that I’m probably wrong, that i’m actually quite ignorant, that my idea is pretty stupid. And I look at the evidence on the other side and I examine it and I try to convince myself that my initial idea was right. And if it isn’t, then I change it.”

***

The line from Zeno was that we were given two ears and one mouth for a reason. That reason? To listen more than we talk.

Today and everyday, we should try to honor the Stoic virtue of wisdom. Get your one thing.

Two ears, one mouth.

Listen accordingly.

You can subscribe to the Daily Stoic Podcast here (Daily Dad here). Also, we have signed copies of all of my Stoic books (including the limited leatherbound edition of The Daily Stoic) available at Daily Stoic’s web store.

The post 25 Things I’ve Learned From a Decade of Podcasts appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

December 1, 2020

This Is the Real Virus to Fear

I found out a few days ago that a friend caught the virus.

I was worried. I felt sorry for them. I was also frustrated. Because it wasn’t COVID they had been infected with, but a different virus related to it: the virus of conspiracy.

Its symptoms presented almost immediately. Along with delusions were the corresponding symptoms of callousness and selfishness and deliberate ignorance.

I was sad.

This was a smart person. A good person!

But here they were, telling me suddenly about their doubts on the efficacy of masks and sending me links to some discredited COVID denier. Over the coming weeks, I would watch them become increasingly radicalized and disconnected from reality; a process that while thankfully not nearly as deadly as COVID, was equally merciless and unstoppable.

This idea that there are other forms of contagion to be worried about during a pandemic is, unfortunately, not a new one. Two thousand years ago, Marcus Aurelius, in the middle of the Antonine Plague, would say that “an infected mind is a far more dangerous pestilence than any plague. One only threatens your life, the other destroys your character.”

It strikes me that the last several months have revealed a few different forms of mental infections.

The first, of course, is conspiracy theories. When we are overwhelmed, hurt, and scared, we tend to grasp for something, anything, that explains the unexplainable. There is a simplicity to the idea that the pandemic is really a hoax, or that 9/11 was an inside job. Somehow it’s actually less scary to believe that it’s all made up, or that your own government is out to get you, than it is to grapple with the idea that they fell down on the job. A world with a cabal of child traffickers operating in plain sight is somehow actually less terrifying than a world of senselessness and chaos and horrible things that happen for no reason.

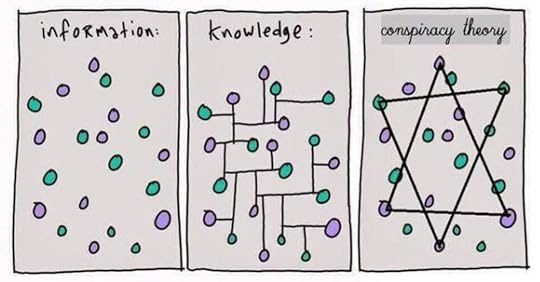

Are there such things as real conspiracies in the world? Of course. I wrote a book about an actual one! But I love the meme designed around a cartoon from the great Hugh MacLeod:

Another common virus is the virus of radicalization. It is this insidious process, initiated by some foreign outside influence, by which we’re drawn into an increasingly opaque world of ideas—one video, one book, one sermon after another. It starts small, a couple of tweets here and there. But then they converge, like cells forming a tumor, and before you know it that tumor is cancer and it’s metastasizing. It’s attacking our body. It’s using our own brain against us. Suddenly, the information that contradicts what we’ve picked up is confirmation of it. They say sunlight is the best disinfectant, but now if you see the sun is shining it’s only proof that the darkness is everywhere.

And so one conspiracy theory leads to another and another and the next thing you know, you’re a raving asshole at best, or worse, a dangerous lunatic.

The irony should not escape us: In the early 2000s, after the heinous attacks of September 11th, the radicalization of young men and women by their exposure to extremist Islamic views became a major topic of discussion at Senate subcommittee hearings and on cable news roundtables. Today, radicalization has come home—brought ashore by our own technologies and media—and it’s just as close-minded, extreme, and violent.

It’s also created people who are totally unreachable. That is how powerful cognitive dissonance can be—impervious to reason, to evidence, to moderation, to critics, to friends and family to get back to the real you. What started as a question or two becomes an elaborate universe, a false reality we inhabit. Some people end up so brainfucked, it’s likely we’ll never get them back.

The problem with conspiracy theories and their radicalizing effect is how related they are to another infection—in fact, they are often comorbid with each other. I’m talking about the infection of cruelty and callousness.

The cancer starts intellectually, but it does its real damage emotionally…

One would think that people who believe that COVID-19 was a biological weapon unleashed upon us by the Chinese would then be taking the risks very seriously, but somehow it’s the opposite: these are also the anti-maskers. (“But it’s uncomfortable!” “But I’m in good shape, why do I have to be inconvenienced?!” “You can’t make me!!!”) These are also the people trying to squint at the numbers to explain away the death toll. These are the ones saying, “Oh, but a lot of these people would have died anyway. They were old, you know.”

Just open everything back up, they say, let the virus run its course…a course that will include many more freezer trucks full of bodies, that will include the preventable losses of so many loved ones. It’s insidious how the virus works, no matter the situation. Show somebody a video of a black man being gunned down in the street and instead of the normal, human reaction of pain and compassion, the mind now plugs in reasons they don’t have to care. What about black-on-black crime? Blue Lives Matter too! But did he have a criminal record?!

It’s the certainty. It’s the closed-offness. Just as COVID can take away your ability to taste or smell, others among us lose their ability to feel.

When Marcus Aurelius was talking about destroying your character, this is what he was talking about. To me, the people ranting at city council meetings, screaming at cashiers, or making up fake doctor’s notes to get out of wearing a mask seem far sicker to me than most of the people I know who have caught the virus. I have a friend whose husband, being overheard expressing some caution about COVID, had his face licked by a colleague who believed the whole thing to be a hoax. You know who does that? A sick person. A person who has not only been infected in a way that has made them deranged, but whose insecurity about that has turned them into a bully.

That was the saddest thing about hearing that my friend had suddenly become an anti-masker. This is a good person. A decent Christian who has always been generous, kind, respectful. Yet they had picked up some beliefs—been corrupted—by something that now violates the most essential teaching in their religion: the commandment to love our neighbors. To love them as we love ourselves. To protect the sick and vulnerable and the meek.

Do not think you are exempt or immune from this corrupting virus. If ordinary people living on the same block as you can be radicalized by falling down internet rabbit holes, if the toxic media (and social media) culture we’re in can nurture and feed unfathomably dark and awful views, then what do you think it’s doing to you? Do you think you yourself might be getting radicalized by your own filter bubble? Are you doing a good enough job holding up every impression and opinion to be tested? Or are you, too, in a less dangerous way, being swept up in the passions of the crowd, however fringe or alt or mainstream that crowd may be?

Radicalization is the scourge of our time. Ordinary people who share an enormous amount in common are being turned against each other. People who are polite and friendly and would help a stranger change a tire on a rainy night on the side of the road are being turned into weapons in a war that helps no one but advertisers and trolls and power-hungry populists.

Of course, most of us are smart enough or emotionally stable enough that we can’t be deceived by the most absurd propagandists. There’s no spiritual hole in us, so we can’t be manipulated by an Alex Jones or whomever, right? Good. But there is another mental virus out there—one that the pandemic has brought out in otherwise smart and rational people.

When things are hard, when things are scary, when we’re tired, when we’ve had a run of bad luck: magical thinking kicks in.

This will all be over soon, we convince ourselves. This one thing will solve all our problems. Our ex is going to walk through the door any minute now. The pandemic will just disappear because we want it to. This kind of thinking makes us feel better, sure, but…that’s just not how it works.

Just ask Chris Christie. He knew he had a lung condition. He knew that testing was not perfect. He knew he should have been wearing a mask at the big White House event. But he told himself, “No, this is a safe space.” Like a lot of people, he probably thought, “This is important, I’ll make an exception.” Or he thought, “I don’t want to deal with the hassle or the awkwardness—I’ll just hope it works out.”

And for Chris Christie and the White House Rose Garden party, we can plug in: “But I really want to see my folks for the holidays.” “It was just a small get together with friends.” “But my kids miss going to school.” “I really want to believe that racism is a thing of the past.”

Well, that’s not how it works.

The last few months have been a great example of the costs that come when magical thinking doesn’t materialize and the chickens come home to roost. When hope is your strategy, you get caught unprepared. When you expect problems to solve themselves, you are disappointed. When you don’t listen to advice because it’s unpleasant or comes with difficult obligations, when you focus on short-term solutions or disregard risks, you’ll find even bad situations can be made worse.

I love this little video: Just because you’re over it, doesn’t mean it’s over yet.

Marcus Aurelius reminds us that we have to see not what the enemy wants us to see, but what is really there. He works through, in Meditations, stripping things of “the legend that encrusts them,” of removing the magical thinking that distorts our picture of the world. You can’t go around expecting Plato’s Republic, he said—the world is harsh, problems are real and no amount of hope makes it otherwise.

We must be on guard.

Not just against COVID-19, but of the other illnesses that its stresses and uncertainty can bring about. What good is surviving the virus—and most people will survive COVID-19, thankfully—if the cost is being a horrible person? If, in so doing, you blatantly rejected your obligations as a human being? If you mocked and dismissed the suffering of the people who are not as fortunate as the rest of us? You think you’re dunking on the other side… really, you’re dunking on yourself.

We have to be kind. We have to be thoughtful. We have to see through the haze.

We can’t deny it, either. Or else we won’t be able to protect ourselves.

Exciting news! We have signed and personalized copies of my books available in the Daily Stoic store. We’ve also got the leatherbound edition of The Daily Stoic back in stock, too. Check out my original trilogy on Stoicism, my latest bestseller Lives of the Stoics, and all the others.

The post This Is the Real Virus to Fear appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

November 25, 2020

Here’s How to Give Thanks—Not Once a Year—but Every Day

The modern practice of this Thanksgiving holiday here in America is that we are supposed to take the time to think about what we’re grateful for. And the candidates are usually pretty obvious: We should be grateful for our families, for our health, that we live in a time of peace, for the good laid out in front of us. All the usual suspects.

I agree, these are important things to recognize and appreciate. It’s also good to have a specific day dedicated to that occasion. So by all means, celebrate.

But over the last few years, I have come to practice a different form of gratitude. It’s one that is a little harder to do, that goes beyond the cliche and perfunctory acknowledgment of the good things in our lives, but as a result creates a deeper and more profound benefit.

I forget how I came up with exactly, but I remember feeling particularly upset—rageful if I am being perfectly honest—about someone in my life. This was someone who had betrayed me and wronged me, and shown themselves to be quite different from the person that I had once so respected and admired. Even though our relationship had soured a few years before and they had been punished by subsequent events, I was still angry, regularly so, and I was disappointed with how much space they took up in my head.

So one morning, as I sat down early with my journal as I do every morning, I started to write about it. Not about the anger that I felt—I had done that too many times—but instead about all the things I was grateful for about this person. I wrote about my gratitude for all sorts of things about them, big and small. It was just a sentence or two at first. Then a few days later, I did it again and then again and again whenever I thought about it, and watched as my anger partly gave way to appreciation. As I said, sometimes it was little things, sometimes big things: Opportunities they had given me. What I had learned. A gift they had given me. What weaknesses they had provided vivid warnings of with their behavior. I had to be creative to come up with stuff, but if I looked, it was there.

A few months later, I came across a viral article about a designer who had gone through a painful divorce. Prompted by his work computer to change his password every 30 days, he decided to use this medium as a chance to change his life. The password he chose: Forgive@h3r. And at least once per day for the next month, often multiple times a day, he found himself typing in that phrase over and over. Each time he got to work, each day when he got back from lunch, when his computer would go to sleep while he was in a meeting or on the phone: Forgive her. Forgive her. Forgive her.

It struck me that there was something similar about my gratitude exercise and the small success I had. It was easy to think negative thoughts and to get stuck into a pattern with them. But forcing myself to take the time not only to think about something good, but write that thought down longhand was a kind of rewiring of my own opinions. It became easier to see that while there certainly was plenty to be upset about, the balance of the situation was still overwhelmingly in my favor. Epictetus has said that every situation has two handles; which was I going to decide to hold onto? The anger, or the appreciation?

Now in the mornings, when I journal, I try to do this as often as I can. I try to find ways to express gratitude not for the things that are easy to be grateful for, but for what is hard. Gratitude for that nagging pain in my leg, gratitude for that troublesome client, gratitude for that delayed flight, gratitude for that damage from the storm. Because it’s making me take things slow, because it’s helping me develop better boundaries, because some flights are going to be delayed and I’m glad it wasn’t a more important flight, because the damage could have been worse, because the damage exposed a more serious problem that now we’re solving. And on and on.

Donald Trump once tweeted “Happy Thanksgiving to all–even the haters and losers!” I’m not a fan, but I must admit that he has a point. We should be giving thanks, even to the “haters and losers.” Actually, that’s who we should be thanking in particular. It’s the “haters and losers” who point out our flaws, keeping us humble if we have the sense to listen. It’s the “haters and losers” whose examples we heed, even if only as guides for what not to do. The point is: There is something to be thankful for in everything and everyone. Even the life of Donald Trump, itself filled with a lot of hating and losing, offers lessons to us all. Mostly, what kind of person not to be. What kind of person to raise our kids not to be.

This is part and parcel of living a life of amor fati. Where instead of fighting and resisting what happens to you, you accept it, you love it all. It’s easy to be thankful for family, for health, for life, even if we regularly take these things for granted. It’s easy to express gratitude for someone who has done something kind for you, or whose work you admire. We might not do it often enough, but in a sense, we are obligated to be grateful for such things. It is far harder to be grateful for things we didn’t want to happen or to people who have hurt us. But there were benefits hidden in these situations and these interactions too. And if there wasn’t, even if the situations were unconscionably and irredeemably bad there is always some bit of us that knows that we can be grateful that at least it wasn’t even worse.

“Let us accept it,” Marcus Aurelius wrote to himself in his own journal some two thousand years ago, “as we accept what the doctor prescribes. It may not always be pleasant, but we embrace it —because we want to get well.” The Stoics saw gratitude as a kind of medicine, that saying “Thank you” for every experience was the key to mental health. “Convince yourself that everything is the gift of the gods,” Marcus said, “that things are good and always will be.” This isn’t always easy to do, obviously, we should try to do it because the doctor asked us to try this experimental procedure—and because the old way isn’t working well either.

I’m not saying it will be magic but it will help.

So as you gather around your family and friends this Thanksgiving or Christmas or any other celebration you might partake in, of course, appreciate it and give thanks for all the obvious and bountiful gifts that moment presents. Just make sure that when the moment passes, as you go back to your everyday, ordinary life that you make gratitude a regular part of it. Again—not simply for what is easy and immediately pleasing.

That comes naturally enough, and may even go without saying. What is in more desperate need of appreciation and perspective are the things you never asked for, the things you worked hard to prevent from happening in the first place. Because that’s where gratitude will make the biggest difference and where we need the most healing.

Whatever it is. However poorly it went. However difficult 2020 has been for you.

Be grateful for it. Give thanks for it. There was good within it.

Write it down. Over and over again.

Until you believe it.

P.S. Today’s article is brought to you by something I use and have used daily and weekly for going on two years: ButcherBox . ButcherBox delivers high quality, grass-fed meat to your doorstep once a month—my wife and I basically haven’t bought meat from the store since we started using it. We’re having a delicious turkey from ButcherBox at our dinner table this holiday . So I love it, and would definitely recommend it to anyone who likes to cook and eats meat. Sign up now and you’ll receive 6 free steaks in your first order—all 100% grass-fed, grass-finished New York strips and top sirloins. ButcherBox is all-natural, animal welfare certified and never ever given antibiotics. Plus, shipping is always free. Hard to beat. Enjoy!

The post Here’s How to Give Thanks—Not Once a Year—but Every Day appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

November 17, 2020

This Is Why Our Leaders Should Be Stoic

It was a dark time for the Republic.

Institutions had stopped working. Interminable foreign wars dragged on. Norms—the old way of doing things—seemed to have broken down. There had been election fixing and the passage of preposterous legislation. Corruption was endemic.

So when a certain popular politician reached out to a senator on the other side of the political aisle to dangle an offer that might make both of them more powerful, it might have seemed like more of the same.

Not to Cato, a philosopher-cum-politician. He wanted nothing to do with the powerful general Pompey’s attempt at an alliance via marriage—perhaps to Cato’s daughter or niece. Although the ladies of Cato’s household were excited at the prospect, Cato was decisively not.

“Go and tell Pompey,” he instructed the go-between, that “Cato is not to be captured by way of the women’s apartments.”

It’s one of those moments that seems admirable through its purity, and high-handedness. Politics shouldn’t be done that way; good for him for staying above it. Yet on closer inspection, it’s one that leaves the historian with considerable doubt. It was principled, but was it politically wise? Was it effective?

Humiliated and angry, Pompey turned to Julius Caesar, who received him with open arms. United and unstoppable, conjoined through marriage to Caesar’s daughter Julia, the two men would soon overturn centuries of constitutional precedent. Civil war soon came.

“None of these things perhaps would have happened,” Plutarch reminds us, “had not Cato been so afraid of the slight transgressions of Pompey as to allow him to commit the greatest of all, and add his power to that of another.”

Rome during this storm is an increasingly cliché reference point these days, but we turn to it because the parallels are there. Thousands of years have passed, and people are still people. Politics is still the same business. Cato remains, as he was then, a complicated figure who should both inspire and caution us.

Cato was a pioneer of the filibuster, blocking any legislation he believed contrary to the country’s interests—blocking even discussion of it. He condemned his enemies loudly and widely. He refused even the slightest political expediency. Cicero observed that Cato refused to accept that he lived amongst the “dregs of Romulus.”

His overweening purity became a vice unbecoming of a philosopher.

It also backed Caesar into a corner. It gave him the very evidence he needed to make his argument: The system isn’t working. I alone can fix it.

Politics can sometimes seem, especially from a distance, like a Manichean struggle between good and evil. In truth, there is always gray—and the good, even the Catos, are not always blameless. Cato’s inflexibility did not always well serve the public good.

At the same time, Cicero, a peer of Cato, provides an equally cautionary example. He was a believer in the republic, but he was also ambitious. He struggled to balance his personal ambitions with his love of Rome’s institutions. In politics, he said, it’s better to stand aside while others battle it out and then side with the winner. Yet he abhorred violence and corruption. After one brave citizen, an artist, stood up to Caesar’s face during a performance, Cicero offered to make room for him in the good seats. “I marvel, Cicero,” the man retorted, “you should be crowded, who usually sit on two stools.” Cicero tried to play it both ways and in the end, accomplished less than Cato—and still died just as tragically.

Does that mean it’s hopeless? That the path for politicians or disgusted citizens is either martyrdom or Vichy-like collaboration?

No, and although we tend to see philosophers as abstract or theoretically thinkers, in fact the Stoics who would come to lead Rome in the years to come learned much from this turbulent period.

Marcus Aurelius, who would step into Caesar’s shoes several generations later, wrote to remind himself that one could not “go around expecting Plato’s Republic.” He knew that it was essential to compromise and collaborate. For example, he historian Cassius Dio compliments Marcus Aurelius for his ability to get the best out of flawed advisors and reach across the so-called aisle to get things done.

Arius Didymus was the Stoic entrusted with advising Caesar’s heir, Octavian. A key element of his instruction was in the virtue of moderation. Although we tend to see “moderate” as a political slur today—just as Cato sometimes did—in truth, it is the key to successful leadership. Moderates are the grease that the wheels of government depend on, and their ability to compromise and accomplish things prevents the ascendency of fringe groups from seizing power for their own ends.

Seneca took this balancing act to even higher levels, managing to hold his nose well enough to get five productive and peaceful years out of the Nero regime. Nothing about that situation pleased him, yet it’s hard to argue that the period of Quinquennium Neronis, those first five years of Nero’s reign, wasn’t the best possible outcome of a bad situation.

George Washington, who took Cato as a personal hero, worked hard to manage his temper better than his idol. The job of a leader, he said, was not simply to follow rigid ideology, but to look at all events, all opportunities, all people through the “calm light of mild philosophy.” This phrase, despite being a phrase from a play about Cato, was quite difficult for the real Cato to follow. It was key to Washington’s greatness, however. His moderation and his self-restraint were what guided America through the revolution and its first constitutional crisis. In a single, tumultuous two-week period in 1797, historians have pointed out, Washington quoted that same line in three different letters. And later, in Washington’s greatest but probably least known moment, when he talked down the mutinous troops who were plotting to overthrow the U.S government at Newburgh, he quoted the same line again, as he urged them away from acting on their anger and frustration.

Unfortunately, we have lost our ability to speak to and study this kind of wisdom. The last time Stoic philosophy was brought to the public political stage, by the brave Admiral James Stockdale, it was all but laughed off for not playing well on television. Today, leaders and the social media mob have absorbed Cato’s stridency without his principles, not realizing what fodder this is for the Caesar’s and would-be Caesar’s of our own time.