Paul Finch's Blog, page 8

July 29, 2020

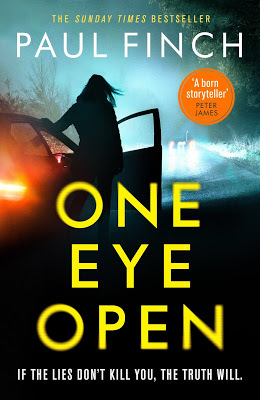

A couple of snippets from ONE EYE OPEN

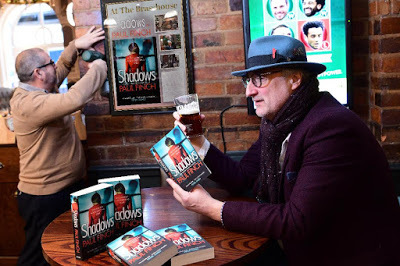

Yesterday, this happened …

Hopefully, that video speaks for itself, but in a nutshell, advance copies of my next novel, ONE EYE OPEN , arrived at our pad, which was something of an unexpected pleasure. It will also give me the opportunity to read a couple of choice snippets for you all … which I’m going to do very shortly in this post.

Before we get onto that, I should also mention that today I’ll also be reviewing and discussing the claustrophobically chilling (and all-round excellent) psycho-thriller, THE RESIDENT, by David Jackson.

As always with my book reviews, you’ll be able to find that at the lower end of today’s post. But if you don’t like reading reviews before you’ve read the books yourself, I still urge you to get hold of this one. Jackson is a high-quality thriller writer, and THE RESIDENT is knife-edge stuff all the way through. As I say, my full review is at the bottom end of today’s post, in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

However, if you’ve got a bit of spare time first, why not check out …

One Eye Open

As you’re probably sick of me saying by now, ONE EYE OPEN is my first book for Orion, and it’s a stand alone crime thriller, which pitches an Essex Traffic officer into a world of robbery, double-dealing and murder.

As promised, I’ll shortly be reading a couple of clips from the finished book.

As promised, I’ll shortly be reading a couple of clips from the finished book.

But before then, for your delectation (and my complete and shameless self-aggrandisement), here is the back-cover blurb, followed by a short handful of quotes from the 25 NetGalley reviewers to thus far give it the big thumbs-up.

YOU CAN RUN

A high-speed crash leaves a man and woman clinging to life.Neither of them carries ID. Their car has fake number plates.In their luggage: a huge amount of cash.Who are they? What are they hiding?And what were they running from?

YOU CAN HIDE

DS Lynda Hagen, once a brilliant detective, gave it all up to raise her family.But something about this case reignites a spark in her...

BUT YOU'LL ALWAYS SLEEP WITH ...

What begins as an investigation soon becomes an obsession.And it will lead her to a secret so dangerous that soon there will be nowhere left to hide.

ONE EYE OPEN ‘I absolutely loved this stand alone masterpiece’. – Beverley S.

‘Fast paced action, dramatic shootouts and an overwhelming sense of threat’. – Jen L.

‘A rich police thriller from an author who always gives a great insight to the world of criminals and the police who go after them’. – Pat C.

‘Breathtaking, shocking and dark!’ – Samantha L.

And now, while my head shrinks back to its normal size, here are a couple of short(ish) readings from the book, provided by yours truly.

In this first one, it’s a cold winter’s day as DS Lynda Hagen pursues a potential witness to a crime into an abandoned holiday park …

In this second one, ex-racing driver, Elliot Wade, finds himself in a fast car with two shady characters, and a lot to prove …

Okay, hope you guys enjoyed those. As I say, ONE EYE OPEN is available for purchase from August 20 in all your usual outlets. Hope you’re interested enough to take a punt.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE RESIDENT by David Jackson (2020)

THE RESIDENT by David Jackson (2020)

OutlineSchizophrenic serial killer, Brogan, his hands still red with the blood of his latest victims, is on the run from the police in the heart of an urban sprawl. But when all avenues of escape seem to be closed to him, he seeks refuge in the empty end-house of a rather run-down terraced row. Unexpectedly, this doesn’t just give him the ability to lie low, because when he investigates the property thoroughly, forcing his way up into the loft, he finds that the dividing wall between this and the next property is incomplete, along with the next dividing wall after that, and the next one and so on.

In short, Brogan finds that he can access all the houses on this side of the street without the official occupants even knowing that he is there … so long as they don’t come up into their attics.

With a jolt of intoxicating pleasure, it slowly dawns on the killer, who never plans very far ahead, that this empty house can be much more than just a useful hiding place.

The problem is that his mind is divided neatly in two, one half more conciliatory but still unstable, callous and inclined to a sexual enjoyment of violence, the other half clever, scheming and sadistic. Occasionally, these two distinct personalities, who occupy Brogan’s head both at the same time, fall out with each other, but mostly they exist in a state of symbiosis, and they are completely in sync when it comes to the way that Brogan should be spending the next few days. Because not only can he creep down into the houses when their owners are out, feed himself and rummage around among private possessions in order to steal, he can also learn all there is about his new hosts, and start to play games with them, alternately antagonising them, making fun of them, frightening them, setting them against each other, the outcomes of which he can watch from the safety of the loft space overhead.

And it’s not as if there isn’t plenty of material for him to work with. Eighty-year-old Elsie is one occupant, an elderly lady who lives alone and is now suffering from mild dementia. Carers visit from time to time, but mostly she is vulnerable and very easily played with.

Then there is Jack and Pam, a middle-aged couple who clearly love each other even though they squabble like cat and dog, and blame each other whenever anything goes wrong (and are out a lot of the time, their property left ripe for plundering); they too make easy targets for manipulation.

Last but very far from least, there is Collette and Martyn. This pair are of particular interest to Brogan, because they are only in their twenties, Collette beautiful and sweet and, Brogan suspects, a little sad.

What fun he is going to have with her in particular.

This is certainly one of the shortest synopses I’ve ever written for one of my online book reviews, quite simply because you’ve already got the crux of it, and to say more might give away vital spoilers.

Suffice to say that Brogan, the new unknown resident in the terraced row, is going to enjoy himself a great deal at the expense of his various unwitting hosts. But it isn’t going to go all his way. Anything can happen in the next few days, things he won’t be expecting at all, and while the situation is unlikely to end well for those who officially live here, it could easily go badly for him too …

Review The Resident is certainly not the first ‘hider in the house’ scenario I’ve encountered in crime and thriller fiction. I’m pretty sure there was even a movie called Hider in the House once. However, there is no idea these days that is original, and in any case, this is without doubt the most intense, dramatic, best-plotted and most enjoyable version of the grand old theme that I have ever read. It’s not a massive tome, coming in at just over 300 pages, but it literally flipped by because almost every one of its short, concise chapters ends on a cliff-hanger as taut as piano wire.

Brogan himself is a fascinating antagonist. We only get to learn about his many terrible crimes through the bizarre conversations that occur inside his head, which we hear in full, and which as well as being subtly informative both about him and his grotesque track-record, are also chilling in their depiction of criminal insanity, and at times wildly if darkly funny.

Yes, there are some comedic elements in this grim tale, but it’s not for the faint-hearted. I even had to stifle a snigger or two at the thought of Brogan, a mad killer, happily making himself at home in others people’s houses, cooking beans, buttering toast, stirring tea, while the actual occupants are out at work, though God knows, it would be an unspeakable invasion of privacy if it were to happen in real life.

You probably wouldn’t care as much for the characters wrapped up in this horror if you didn’t gradually come to see them so clearly, and this is another neat touch by David Jackson. When the killer first arrives in his improvised refuge, neither he nor we know anything at all about the population of this terraced row, but that’s okay, because we learn about them as Brogan does and at exactly the same pace, by listening to their interactions through trapdoors or watching them through peepholes in the ceiling.

While Jack and Pam are perhaps a little bit stock, Elsie is a wonderful creation. I can imagine that a veteran actress would have a lot of fun with this part in any screen adaptation. Her tragic situation, which you might expect to cast her as one of life’s forgotten victims and maybe a constant mope, is enlivened by the return of her maternal instincts (long buried, but always there) and the feistiness with which she treats her carers when she starts to suspect they are humouring her about the ‘return of her deceased son’.

The other stars of the show, though, are the final couple in the terraced row, Collette and Martyn, though Collette is the more important of the two, at least where Brogan is concerned.

In classic ‘beauty and the beast’ fashion, Brogan doesn’t just desire her physically; the more he gets to know about her, the more he subconsciously likes her, and the more he starts to think of her as a potential companion rather than a victim. In concert with this, the more he starts to distrust and finally hate her husband, Martyn, which developing ménage à trois gives us some of the most intense and emotionally dramatic sequences in the book.

But all the thrills and chills aside, in a relatively quickfire piece of writing, David Jackson has created several such exceptional dynamics, which crank the readability of The Resident up to top notch. You really feel for everyone, and really need to know what’s going to happen next.

Of course, getting back to Brogan and the terrible situation he has engineered and soon ends up trapped in – and this is the real heart of the story, the part that works so well for me – he may increasingly take Collette and Elsie’s side, he may view them both (but mainly Collette) as lost, abused and neglected, as a twosome who deserve so much more than life has dealt them, so it’s no wonder he sees himself reflected there. But this isn’t going to be reciprocated, because to the likes of Collette, Brogan will always be a monster. That’s the underlying darkness in this tale, and its cleverness. Though you live inside his head with him and get to know him well, though you even start to empathise a little … you never forget that Brogan is a monster.

Read The Resident . It’s a superb, fast-paced thriller, weaving multi-layered characters into a scenario from Hell that will have you both shuddering and snickering all the way through.

As always, I’m now going to try and cast this saga. Just a bit of fun – who would ask me? – but here are the main actors I would choose, were I putting this cracker on the screen:

Brogan – Max IronsCollette – Lupita Nyong’oElsie – Gemma Jones Martyn – Samuel Anderson

Hopefully, that video speaks for itself, but in a nutshell, advance copies of my next novel, ONE EYE OPEN , arrived at our pad, which was something of an unexpected pleasure. It will also give me the opportunity to read a couple of choice snippets for you all … which I’m going to do very shortly in this post.

Before we get onto that, I should also mention that today I’ll also be reviewing and discussing the claustrophobically chilling (and all-round excellent) psycho-thriller, THE RESIDENT, by David Jackson.

As always with my book reviews, you’ll be able to find that at the lower end of today’s post. But if you don’t like reading reviews before you’ve read the books yourself, I still urge you to get hold of this one. Jackson is a high-quality thriller writer, and THE RESIDENT is knife-edge stuff all the way through. As I say, my full review is at the bottom end of today’s post, in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

However, if you’ve got a bit of spare time first, why not check out …

One Eye Open

As you’re probably sick of me saying by now, ONE EYE OPEN is my first book for Orion, and it’s a stand alone crime thriller, which pitches an Essex Traffic officer into a world of robbery, double-dealing and murder.

As promised, I’ll shortly be reading a couple of clips from the finished book.

As promised, I’ll shortly be reading a couple of clips from the finished book. But before then, for your delectation (and my complete and shameless self-aggrandisement), here is the back-cover blurb, followed by a short handful of quotes from the 25 NetGalley reviewers to thus far give it the big thumbs-up.

YOU CAN RUN

A high-speed crash leaves a man and woman clinging to life.Neither of them carries ID. Their car has fake number plates.In their luggage: a huge amount of cash.Who are they? What are they hiding?And what were they running from?

YOU CAN HIDE

DS Lynda Hagen, once a brilliant detective, gave it all up to raise her family.But something about this case reignites a spark in her...

BUT YOU'LL ALWAYS SLEEP WITH ...

What begins as an investigation soon becomes an obsession.And it will lead her to a secret so dangerous that soon there will be nowhere left to hide.

ONE EYE OPEN ‘I absolutely loved this stand alone masterpiece’. – Beverley S.

‘Fast paced action, dramatic shootouts and an overwhelming sense of threat’. – Jen L.

‘A rich police thriller from an author who always gives a great insight to the world of criminals and the police who go after them’. – Pat C.

‘Breathtaking, shocking and dark!’ – Samantha L.

And now, while my head shrinks back to its normal size, here are a couple of short(ish) readings from the book, provided by yours truly.

In this first one, it’s a cold winter’s day as DS Lynda Hagen pursues a potential witness to a crime into an abandoned holiday park …

In this second one, ex-racing driver, Elliot Wade, finds himself in a fast car with two shady characters, and a lot to prove …

Okay, hope you guys enjoyed those. As I say, ONE EYE OPEN is available for purchase from August 20 in all your usual outlets. Hope you’re interested enough to take a punt.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE RESIDENT by David Jackson (2020)

THE RESIDENT by David Jackson (2020)OutlineSchizophrenic serial killer, Brogan, his hands still red with the blood of his latest victims, is on the run from the police in the heart of an urban sprawl. But when all avenues of escape seem to be closed to him, he seeks refuge in the empty end-house of a rather run-down terraced row. Unexpectedly, this doesn’t just give him the ability to lie low, because when he investigates the property thoroughly, forcing his way up into the loft, he finds that the dividing wall between this and the next property is incomplete, along with the next dividing wall after that, and the next one and so on.

In short, Brogan finds that he can access all the houses on this side of the street without the official occupants even knowing that he is there … so long as they don’t come up into their attics.

With a jolt of intoxicating pleasure, it slowly dawns on the killer, who never plans very far ahead, that this empty house can be much more than just a useful hiding place.

The problem is that his mind is divided neatly in two, one half more conciliatory but still unstable, callous and inclined to a sexual enjoyment of violence, the other half clever, scheming and sadistic. Occasionally, these two distinct personalities, who occupy Brogan’s head both at the same time, fall out with each other, but mostly they exist in a state of symbiosis, and they are completely in sync when it comes to the way that Brogan should be spending the next few days. Because not only can he creep down into the houses when their owners are out, feed himself and rummage around among private possessions in order to steal, he can also learn all there is about his new hosts, and start to play games with them, alternately antagonising them, making fun of them, frightening them, setting them against each other, the outcomes of which he can watch from the safety of the loft space overhead.

And it’s not as if there isn’t plenty of material for him to work with. Eighty-year-old Elsie is one occupant, an elderly lady who lives alone and is now suffering from mild dementia. Carers visit from time to time, but mostly she is vulnerable and very easily played with.

Then there is Jack and Pam, a middle-aged couple who clearly love each other even though they squabble like cat and dog, and blame each other whenever anything goes wrong (and are out a lot of the time, their property left ripe for plundering); they too make easy targets for manipulation.

Last but very far from least, there is Collette and Martyn. This pair are of particular interest to Brogan, because they are only in their twenties, Collette beautiful and sweet and, Brogan suspects, a little sad.

What fun he is going to have with her in particular.

This is certainly one of the shortest synopses I’ve ever written for one of my online book reviews, quite simply because you’ve already got the crux of it, and to say more might give away vital spoilers.

Suffice to say that Brogan, the new unknown resident in the terraced row, is going to enjoy himself a great deal at the expense of his various unwitting hosts. But it isn’t going to go all his way. Anything can happen in the next few days, things he won’t be expecting at all, and while the situation is unlikely to end well for those who officially live here, it could easily go badly for him too …

Review The Resident is certainly not the first ‘hider in the house’ scenario I’ve encountered in crime and thriller fiction. I’m pretty sure there was even a movie called Hider in the House once. However, there is no idea these days that is original, and in any case, this is without doubt the most intense, dramatic, best-plotted and most enjoyable version of the grand old theme that I have ever read. It’s not a massive tome, coming in at just over 300 pages, but it literally flipped by because almost every one of its short, concise chapters ends on a cliff-hanger as taut as piano wire.

Brogan himself is a fascinating antagonist. We only get to learn about his many terrible crimes through the bizarre conversations that occur inside his head, which we hear in full, and which as well as being subtly informative both about him and his grotesque track-record, are also chilling in their depiction of criminal insanity, and at times wildly if darkly funny.

Yes, there are some comedic elements in this grim tale, but it’s not for the faint-hearted. I even had to stifle a snigger or two at the thought of Brogan, a mad killer, happily making himself at home in others people’s houses, cooking beans, buttering toast, stirring tea, while the actual occupants are out at work, though God knows, it would be an unspeakable invasion of privacy if it were to happen in real life.

You probably wouldn’t care as much for the characters wrapped up in this horror if you didn’t gradually come to see them so clearly, and this is another neat touch by David Jackson. When the killer first arrives in his improvised refuge, neither he nor we know anything at all about the population of this terraced row, but that’s okay, because we learn about them as Brogan does and at exactly the same pace, by listening to their interactions through trapdoors or watching them through peepholes in the ceiling.

While Jack and Pam are perhaps a little bit stock, Elsie is a wonderful creation. I can imagine that a veteran actress would have a lot of fun with this part in any screen adaptation. Her tragic situation, which you might expect to cast her as one of life’s forgotten victims and maybe a constant mope, is enlivened by the return of her maternal instincts (long buried, but always there) and the feistiness with which she treats her carers when she starts to suspect they are humouring her about the ‘return of her deceased son’.

The other stars of the show, though, are the final couple in the terraced row, Collette and Martyn, though Collette is the more important of the two, at least where Brogan is concerned.

In classic ‘beauty and the beast’ fashion, Brogan doesn’t just desire her physically; the more he gets to know about her, the more he subconsciously likes her, and the more he starts to think of her as a potential companion rather than a victim. In concert with this, the more he starts to distrust and finally hate her husband, Martyn, which developing ménage à trois gives us some of the most intense and emotionally dramatic sequences in the book.

But all the thrills and chills aside, in a relatively quickfire piece of writing, David Jackson has created several such exceptional dynamics, which crank the readability of The Resident up to top notch. You really feel for everyone, and really need to know what’s going to happen next.

Of course, getting back to Brogan and the terrible situation he has engineered and soon ends up trapped in – and this is the real heart of the story, the part that works so well for me – he may increasingly take Collette and Elsie’s side, he may view them both (but mainly Collette) as lost, abused and neglected, as a twosome who deserve so much more than life has dealt them, so it’s no wonder he sees himself reflected there. But this isn’t going to be reciprocated, because to the likes of Collette, Brogan will always be a monster. That’s the underlying darkness in this tale, and its cleverness. Though you live inside his head with him and get to know him well, though you even start to empathise a little … you never forget that Brogan is a monster.

Read The Resident . It’s a superb, fast-paced thriller, weaving multi-layered characters into a scenario from Hell that will have you both shuddering and snickering all the way through.

As always, I’m now going to try and cast this saga. Just a bit of fun – who would ask me? – but here are the main actors I would choose, were I putting this cracker on the screen:

Brogan – Max IronsCollette – Lupita Nyong’oElsie – Gemma Jones Martyn – Samuel Anderson

Published on July 29, 2020 08:04

July 12, 2020

All the chills of Christmas this dark July

So, we had blistering sunshine in March and April, pouring rain and bitter winds in June, and now … we’ve got Christmas in July.

Well, it’s not strictly true that we’ve got Christmas in July, but as the jacket art is now ready for the three Christmas books I intend to bring out this autumn, I thought this might be an opportune time to give you your first glimpse, and maybe to chat a little about the plans I’ll put into force once this strangest summer of all has ended.

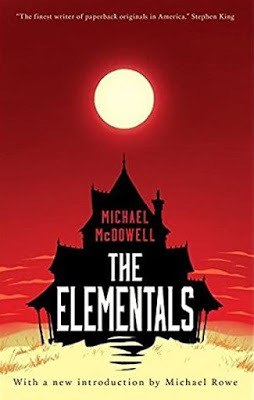

Which reminds me that – even though the virus is still with us, and many holidays have been cancelled, and the weather is pathetic compared to the weather we had in spring – it is still summer. So, in keeping with that, today I’ll also be reviewing and discussing one of the best summertime horror novels I’ve ever read: THE ELEMENTALS by the late, great Michael McDowell.

If you’re only here for the McDowell discussion, then that’s fine, as always. Just shoot on down to the lower end of today’s blog, and you’ll find it in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

Before then, however, if you’ve got a bit of extra time, I’m going to talk a little about …

Scary stuff this Christmas

Readers who follow this column regularly, will know that I’m a big fan of Christmas-themed scare-fare. Now, I assure you that this doesn’t mean I think about the festive season from January to December. I like all the seasons, and I particularly enjoy horror fiction (folk-horror would be the thing for this, I guess) that encompasses these different times of year with their various special days and ancient festivals.

But winter, and Christmas in particular, has always been a biggie in this regard. If you need proof of that, don’t take my word for it. I mean, I might have written many Christmas ghost and horror stories, but it’s a tradition that goes way back to MR James, Charles Dickens and beyond. So, there is a kind of precedent for it, to say the least.

By the way, I’m not comparing myself to those masters of the short form, but I do like to think I’ve got a decent track record when it comes to this sort of thing. Hence, I thought this year I’d try to package some Christmas specials – some ‘Christmas annuals’, as they used to say in comic parlance – and put them out there in print.

Two of these will not be unfamiliar, though I did feel it was about time they got something of a reboot.

First of all, we have:

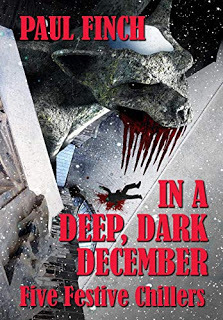

IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBERFive Festive Chillers

First published in 2013, though some technical hiccups saw it briefly removed from Amazon a couple of years ago, which obliterated the 30-odd approving reviews it had garnered, this is a collection of five Christmas stories and novellas, all supernatural in tone, all horrific in theme.

The table of contents is as follows:

The Christmas Toys

Midnight Service

The Faerie

The Mummers

The Killing Ground

You may wonder why I’m bringing it out again. Well, the truth is that I’m not really. It remains available as an ebook as it always was, but one complaint I received back in the day was that it never existed in print. Well … from this autumn it will do, under the above newly-designed wrap from the original artist, the indefatigable Neil Williams.

Yes, it’s the same stories that appeared electronically, but for the first time ever (in English) it will now be available in paperback too. On top of that, I’m very excited to announce that it will also be coming out in Audible, as narrated by actor, Greg Patmore, who did such a storming job with last year’s autumn release, SEASON OF MIST .

In a similar mood but much newer, the second festive collection I’ll be bringing out towards the end of this year is:

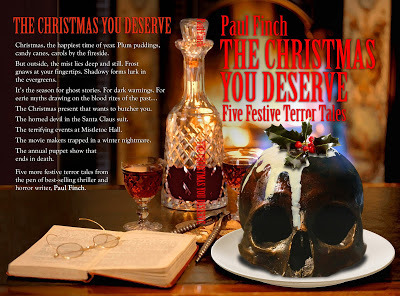

THE CHRISTMAS YOU DESERVEFive Festive Terror Tales

This is another collection of horror stories and novellas set in and around the Christmas season. But these you won’t have seen together in a single collection, electronically or otherwise … until now. Here’s the table of contents:

The Merry Makers

The Unreal

Krampus

The Tenth Lesson

The Stain

This too will be available in print, as an ebook and on Audible (yet again, with Greg Patmore providing the silken tones). As before, enjoy the marvellous cover art created by Neil Williams.

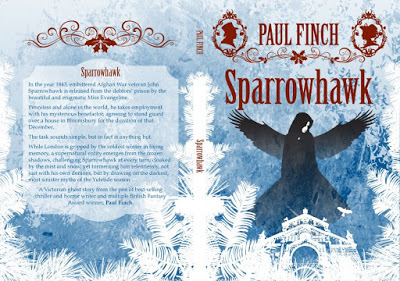

Last of the three, we’re back in familiar territory again, but with a completely new look. This one is:

SPARROWHAWK

People may recall that this Christmas-themed horror / romantic / Victorian novella first appeared in 2010 from Pendragon Press, and that it was shortlisted for the British Fantasy Award in the capacity of Best Novella the following year. In due course though, the print-run ended, and it was available from that point only as an ebook.

Well, the ebook remains and can be acquired as we speak. But this autumn there’ll be a brand new paperback version and again, it will be coming out on Audible (courtesy of Mr Patmore).

For those unaware, the story is set during the bitter winter of 1843, and follows the fortunes of an Afghan War veteran, who, on release from the debtors’ prison is tasked with protecting a mysterious house in Bloomsbury against an unknown enemy, a duty that unleashes a literal smogasbord of Yuletide terrors.

To round up, I apologise for talking Christmas in early July, but I do like to drop hints about what’s coming in the months ahead. If you continue to watch this space, there’ll be many more details – links, background info etc – posted here as the summer finally wanes and the darker months draw on.

Now okay, I know it’s pretty dark and gloomy outlook at present, but I promise you that this distinctly is not the case in the book I’ve chosen to review this week. Read on if you don’t mind getting sunstroke simply from the written page.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE ELEMENTALS

by Michael McDowell (1981)

OutlineThe Savages and McCrays are a prosperous pair of families. Born into the Deep South elite, Alabama aristocracy from way back, they lack for absolutely nothing.

Head of the Savage household, Dauphin, is a multi-millionaire and still relatively young. He’s known far and wide as a thoroughly nice guy, and is married to former beauty queen, Leigh, ex of the McCrays, which is where the link between the two families comes in. The McCrays, in their turn, live under the shadow of their patriarch, Lawton, a hugely successful businessman who is now standing for Congress, while his son, Luker, who lives in New York, is so well-fixed professionally that, at the drop of a hat, he can afford to take the entire summer off and vacation in the South.

And yet for all this gold-plated privilege, there are deep strains within the two families, equally deep animosities and even deeper divisions.

Lawton McCray, for example, is separated from his wife, Big Barbara, and reviled by Luker, who views him as the worst kind of ruthless capitalist but as a dangerous man too, because in the spirit of the Old South, where he was born, Lawton will stop at nothing, even crime and violence, to get what he wants. Due in no small way to this unhealthy arrangement, Big Barbara is an unreformed alcoholic, which has left her a silly, unthinking woman, who Luker can also barely tolerate, though recognising that there’s no real evil in her, he does his best. All that said, Luker himself has no dealings with his own ex-wife, from whom he is very acrimoniously divorced … to such an extent that his teenage daughter, India, who has lived with him most of her life, has been raised to dread the mere mention of her mother’s name. India, in fact, though a free-spirited, well-educated New York girl, often struggles because of her father’s domestic prejudices, whether they are merited or not, scarcely knowing how to react to her grandparents.

And then there is the infamously bad-tempered Marian Savage, Leigh’s mother-in-law, whom Luker also hates – or perhaps that should be hated, because we open the narrative at Marian’s funeral. Just in case none of what we’ve so far learned is dysfunctional enough, the funeral service, which is very poorly attended, is interrupted halfway through by an age-old Savage tradition, Dauphin opening his mother’s casket and stabbing her in the heart. Apparently, this is now the custom at all Savage funerals on account of a non-too-distant ancestor being unfortunately buried alive.

So far so Southern Gothic, you may think, and yes, we are firmly in that sun-soaked, uber-melodramatic territory. But The Elementals is also a ghost story, and it isn’t long before we arrive at the scene of the haunting.

At the close of the funeral, the two famlies head south to Mobile, on the Gulf Coast, where they are both part-owners of Beldame. This is basically a narrow spit of sand extending far out into the ocean (though often, the high tide renders it an island), the extreme tip of which is occupied by a row of three beautiful Victorian houses. Here, year-round warm weather (gloriously so in summer), blue skies, an even bluer sea, and complete isolation, always provide a relaxing break. The older members of the two families are completely besotted with the place and have been coming here since the 1950s. Even India, who has never been before, doesn’t much care for her relatives and would rather be in New York, is stunned when she first arrives. She can’t believe how lovely it is, even if oddities emerge almost straight away.

The third house in the row, for example, is owned by neither the Savages nor the McCrays (no one seems to know who owns it) and is succumbing to an immense sand dune, which has built up alongside it and is now slowly engulfing the entire structure.

In due course, this third house will start to cause serious problems, though at first all is well.

It’s unusually hot, even for Southern Alabama, and the two families are just glad to have got away from it all, and now unwind in the taciturn but fastidious care of Odessa, the Savages’ black servant, who’s been with the family since before the Civil Rights Movement but who stays with them because she is treated like a relative, even though she herself doesn’t behave this way.

During this languid time (when the livin’ is very easy!) other quirks of Savage/McCray family life emerge in full keeping with the oddball Southern Gothic tradition. Though Luker is well regarded by his family, he swears and profanes freely in front of them all, including his mother, and thinks nothing of sunbathing naked in the presence of his 13-year-old daughter (a liberal approach to life that she returns in full). But none of this seems out of place here at Beldame, where the sun beats down, the sea laps, the sands continually shift, and time literally seems to stop (the families never follow any kind of itinerary when they’re here, they just let the day and the mood take them).

And yet throughout, there is a clear feeling that, despite the summer lassitude, all is not well. The families love Beldame, but it’s soon evident that they are wary of the place too, particularly the third house, though no one seems to be willing to say why, especially Odessa, even though she – or so India suspects – knows most.

The youngster finally starts to wheedle it out of her elders just what the problem is, learning that the third house has been a blot on this picturesque coastline for quite some time. The reasons for this seem to vary. It’s not exactly an eyesore, but it’s been empty and unclaimed for so long that it’s decaying as well as disappearing into the sand. It seems especially weird though that third house is still fully furnished inside, almost as if someone still lives there. And yet neither the McCrays nor the Savages ever go in to look around.

Most interesting to India, though, are the third property’s ghostly aspects.

There are only one or two stories to this effect, and they have the aura of campfire tales. For example, a bunch of school friends once swore blind that they saw a naked fat woman walking around on the third house’s roof.

When India commences her own investigation of the third property, she immediately detects a presence and later learns that Odessa had a little girl once, Martha Ann, who disappeared here but was presumed drowned, India concludes that the third house is haunted by the child’s ghost. Odessa, finally breaking her silence, simply replies that it isn’t so.

Martha Ann is indeed dead, she says, but what occupies the third house is not her ghost. It is something much, much worse …

Review

Michael McDowell wrote several successful novels, but died at the tragically young age of 49, which on the evidence of The Elementals , was a major loss to genre fiction.

Because, in short, this is a very frightening ghost story.

Not only that, it tips all expectations on their head. Sun, sea, sand. Hardly scary, you may think. Well, you’d be wrong. An affluent southern family: handsome men, gorgeous women, heated passions – all the ingredients of a domestic melodrama rather than a horror story, right?

Wrong.

Wrong, wrong, wrong.

It’s a bit of a culture shock when you first start reading The Elementals . Because the one or two minor macabre details aside – Marian Savage’s funeral, Luker’s utter (and never fully explained) hatred for his ex-wife – it does feel as if you’ve strayed into a Tennessee Williams play. But that doesn’t last long. Because Beldame (which in Old English used to mean ‘witch’, of course), is so well-realised a location that it really is a place apart. Its atmosphere is one of strangeness, dreaminess, and yet all the time, right from the outset, the sinister presence of the third house is there, just on the corner of our vision.

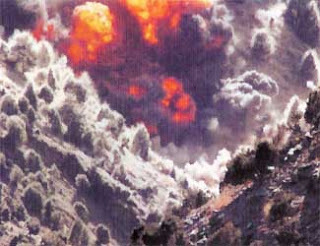

All of this feeds nicely into the plot’s slow-burn development. We certainly have a lengthy period when nothing really seems to happen, the family re-acclimatising to Beldame, sunbathing, sleeping, engaging in idle conversation, and yet odd, unnatural things do happen. At first, they are small, and eerie rather than frightening. But they come more and more regularly, the sense of foreboding gradually growing, until finally the occupants of the third house, disturbed from their slumbers by both India’s curiosity and Lawton’s villainous schemes, explode out in some of the most terrifying ways imaginable.

But I think what works best for me in The Elementals is not so much the increasingly scarier story, but the unknowable nature of the antagonists.

I don’t want to say too much about them because I don’t want to spoil things more than I already have. But as you are likely to guess from an early stage, these aren’t ghosts or even demons in the conventional sense. This is something else entirely. Luker McCray only calls them ‘elementals’ because he can’t think of any other way to describe them, but it’s highly appropriate. Because whatever they are, they are part of this place, and always have been.

It certainly makes for a intriguing conflict: the time-honoured, all-powerful southern clan coming up against an infinitely more ancient and immovable force, something intangible and yet sentient, something that is intricately connected to this lonesome spit of land, so much so that it can control the sand, the air and the water, and yet something that can strike at its opponent in any number of ghastly and horrifying ways – and trust me, these are ghastly.

You may have to wait a little while for them, but the moments of horror, when they come, are literally hair-raising.

As I say, apart from the catastrophe of losing Michael McDowell as a person, we also lost a prodigious talent, and what I imagine would have been a plethora of such clever and spine-tingling tales.

If you’ve not read The Elementals , you must do. It was first published in the 1980s, but it’s a timeless chiller in the best way, and I’m not remotely surprised that Poppy Z Brite referred to it as ‘surely one of the most terrifying novels ever written,’, or that Stephen King described McDowell as ‘the finest writer of paperback originals in America,’ while Peter Straub called him ‘one of the best writers of horror in this or any other country’.

And now, here we go again. I’m going to be bold (or stupid) enough to try and nominate my own cast should this very fine horror story ever hit the screen. If only I had the power to make it happen in reality:

India McCray – Lara Decaro

Odessa Red – Viola Davis

Luker McCray – Joe Kinnaman

Lawton McCray – Woody Harrelson

Big Barbara – Rebecca Front

(The picture at the top is not mine, but despite searching online, I couldn't find an owner. If anyone has an issue with me using it without a credit, just let me know and I'll add a credit immediately, or even remove it).

Published on July 12, 2020 03:06

June 21, 2020

Cops and killers from page to big screen

Okay, we’re not quite there yet … and no, I’m not talking about the end of lockdown (though it feels closer than it was). I’m referring to ONE EYE OPEN, my next cop novel, which is due for publication across all platforms on August 20. In fact, it’s so close now that today I received my first tweet from a NETGALLEY reviewer about how much they are enjoying it.

Talk about a nice way to start the day.

Of course, one of the things that always enters an author’s mind as the publication of their new novel appears on the horizon is ‘will this be the one?’ Not just the breakout novel, but the one that hits the top of the charts and stays there? The one that means the staff in your local branch of Waterstones actually start to say ‘hello’ to you? The one that gets adapted into a multi-million dollar movie?

We all live in hope of course, but just to prove that it can happen sometimes, today I thought I’d look at some of those awesome cop thrillers that went before me and then hit the light fantastic a second time when Hollywood got hold of them.

In that same spirit, I’ll also be reviewing and discussing IN THE WOODS by Tana French – a superb police novel which, while it didn’t become a blockbusting movie, went on to become a successful TV series (see above).

In that same spirit, I’ll also be reviewing and discussing IN THE WOODS by Tana French – a superb police novel which, while it didn’t become a blockbusting movie, went on to become a successful TV series (see above).If you’re only here for the Tana French review, no worries. Get straight on down to the lower end of today’s post. But if you’ve got some extra time on your hands, you might also be interested in …

Screen cops who were on the page first

Though I’ve written lots of movie scripts, two of which actually got made into movies, I’d reserve a special place in my heart for any novel of mine that received the film treatment.

I’m not sure why. Perhaps it’s just that with something you hatched yourself and have then lived and breathed for month on end, sweated over, bled over (etc), characters you gave birth to, nurtured and developed (etc), it would just be so damn cool to see someone else’s take on the same story, especially if they were putting Hollywood-type money into it, and even more especially with a major league talent behind the lens.

Of course, whenever this happens, authors aren’t always happy with the outcome no matter how much money it might earn them from the cinema-going public.

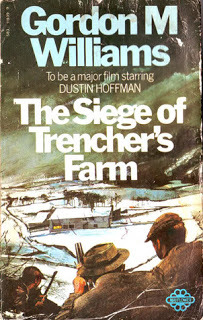

Of course, whenever this happens, authors aren’t always happy with the outcome no matter how much money it might earn them from the cinema-going public. Stephen King famously didn’t like Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 reimagining of his 1977 novel, The Shining , while Gordon Williams was furious when, in 1971, Sam Peckinpah turned his 1969 novel, The Siege of Trencher’s Farm , into the controversial and violent Straw Dogs .

I’m not sure how I’d have reacted in either case, given that both movies made a bomb at the Box Office and probably re-energised the sales of the original books to some tune. A bigger issue for me might be the occasionally-heard complaint that a film version has overtaken the book in terms of fame … even to the point where the book itself has all but vanished from public awareness.

A couple of obvious examples of this spring to mind. Most people remember Alfred Hitchock’s 1972 serial killer thriller, Frenzy , but very few even know that it was adapted from Arthur Le Bern’s 1966 novel, Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square . Likewise, we all remember Hitch’s even more sensational slasher horror, Psycho , but who outside students of the genre is even aware that it came from Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel of the same name?

Again, I’m not sure how I’d respond. In truth, I think I’d just be happy that Hollywood was taking a punt. But again, just to prove the point that it can also happen with my genre, here, in no particular order, are …

Ten Major Cop Movies You (Quite Possibly) Didn’t Know Started Life as Novels

1 Bullitt (1968)

1 Bullitt (1968)Long years have passed but most movie fans still fondly recollect the late, great Steve McQueen’s superb performance as Frank Bullitt (top), a San Francisco police lieutenant, who, when he loses his mob supergrass to hitmen, makes it his personal mission to catch the bigwig who gave the order. They also remember the astonishing car chase, at the time one of the greatest ever committed to film.

Not many know that this cinema cop classic came to us straight from Robert L Fish’s 1963 novel, Mute Witness . Swap a few names and the San Fran setting for New York, and it’s a very similar tale.

2 Cop (1988)

2 Cop (1988)James Woods puts in a mesmerising shift as amoral LAPD detective, Lloyd Hopkins, whose talent is recognised by his superiors, but who is also considered a risk-taker. As such, when he investigates the death of a politically active call girl and concludes it’s the work of an unidentified serial killer, the top floor won’t trust him. Hopkins, who already has problems at home, has no option but to go it alone.

It sprang from a more famous original novel in this case, James Ellroy’s 1984 classic, Blood on the Moon , the first in a Lloyd Hopkins trilogy. Similar thrills, similar politics, but with an even grittier 1970s setting.

3 Hell is a City (1960)

3 Hell is a City (1960)Stanley Baker is pitch perfect in Val Guest’s famous Brit Noir, in which a tired Manchester DI is so determined to nail an old foe who has recently staged a violent jailbreak and might already be responsible for another robbery, that his failing marriage takes second place. Riding the British New Wave film movement, the producers happily left London and hit us with some real northern grit.

In the original, in 1954, Maurice Procter introduced us to Detective Chief Inspector Martineau in the pacy Somewhere in the City , the first of a whole series of gritty hard-hitting thrillers set in the bleakly industrial North.

4 The Big Heat (1953)

4 The Big Heat (1953)Vintage Noir, as Glen Ford takes on the mantle of small-town cop looking into the suicide of a fellow officer, only to uncover a rat’s nest of intrigue, corruption, prostitution and murder. ‘Master of Darkness’ Fritz Lang added many horrorish moments, including a real shocker in which low level thug Lee Marvin throws scalding coffee into the face of gangland moll, Gloria Grahame.

Originally written by William P McGivern, The Big Heat appeared episodically in The Saturday Evening Post in 1953, only hitting the bookstalls much later as a complete novel. Every bit as tough as the film.

5 Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988)

5 Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988)Yes, you heard that right. Disney/Amblin’s big ‘live action plus animation’ hit of the late 1980s actually started life as a comedy suspense novel. In the movie, you’ll recall that Bob Hoskins is the down-on-his-luck detective who has spent most of the 1940s drunk but who, when called on to check the suspicious antics of cartoon star Roger Rabbit’s wife, Jessica, uncovers a fiendish conspiracy.

In Gary K Wolf’s 1981 original, Who Censored Roger Rabbit? , the story differs quite a bit, the toons mostly from comic strips, but sexy Jessica still gets to say that she’s ‘not bad, just drawn that way’.

6 The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)

6 The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)One of the great action movies of the 1970s, Joseph Sargent’s high tension tour-de-force follows the capture of a New York subway train and its passengers by a gang of highly organised hijackers under the control of a ruthless British former-SAS soldier (a steely Robert Shaw) who will kill anyone that defies him, while Transit Lieutenant Walter Matthau coolly attempts to outmanoeuvre them. A crime classic.

John Godey’s 1973 novel of the same name follows the same course as the film, with some differences in terms of characters but the same ingenious plot twists that would give the movie its wow factor.

7 Bunny Lake is Missing (1965)

7 Bunny Lake is Missing (1965)Perhaps not strictly a ‘cop movie’, more a ‘psychological thriller’, though Detective Superintendent Newhouse (Laurence Olivier) is the main investigator and a key character when toddler Bunny Lake goes missing from her London nursery school, the top cop increasingly turning curious about her stressed single parent (Carol Lynley) as there is progressively less evidence that the child ever existed.

Evelyn Piper’s 1957 original is set in New York and focusses much more on the terror and trauma of the shunned single mother as she searches for her child alone. Both however, are regarded as masterpieces.

8 In the Heat of the Night (1967)

8 In the Heat of the Night (1967)Virgil Tibbs, a black police detective from Philadelphia, is accused of murder while visiting a Mississippi town, but eventually forms an alliance with the racist chief of police, teaching him the error of his ways and at the same time helping him catch the real killer. Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger give unforgettable star turns in this groundbreaking thriller, which was much applauded by the Civil Rights movement.

John Ball’s original novel of 1965 told the same story, though the setting is South Carolina and Tibbs is a cop with Pasadena PD. Its huge success kickstarted a whole series of Virgil Tibbs novels.

9 The Detective (1968)

9 The Detective (1968)Frank Sinatra gives what is generally regarded as a career best performance as Joe Leland, a veteran NYPD sergeant, whose ‘no nonsense’ approach to his job holds his team together when a disgusting murder leads them into a world of vice and exploitation. A grown-up and high-quality mystery thriller, one of the first ever to openly confront such new-fangled issues as pornography and gay prostitution.

Roderick Thorp’s original 1966 novel was a cutting-edge slice of Noir in an age when that genre hadn’t yet dated. Concerns a PI, not a cop, but still packed with grown-up material and frank police speak.

10 Die Hard (1988)

10 Die Hard (1988)Everyone’s favourite Christmas action movie, NYPD reject John McClaine taking on a whole posse of deranged terrorists when they take over LA’s Nakatomi Tower but make the mistake of capturing his exec wife in the process. It made stars of Bruce Willis and Alan Rickman and set a new high bar when it came to full-on Hollywood shoot-em-up. Very few know that it was the sequel to The Detective (above.).

Roderick Thorp wrote Nothing Lasts Forever in 1979, with creaky retiree, Joe Leland, taking on the terrorists in LA’s 40-storey Klaxon Tower. Amazingly, 73-year-old Sinatra almost got the part in the film.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

IN THE WOODS

IN THE WOODS by Tana French (2007)

OutlineDuring a gorgeous summer in Knocknaree, in the lush countryside outside Dublin, three 12-year-olds sleepwalk into tragedy. A close-knit group of friends, they are Jamie, Adam and Peter, and they are living life as only carefree youngsters can, spending each day of their school holidays romping through the sun-drenched meadows and woods – particularly through the woods.

Where one day something terrible happens.

When the evening arrives and the trio still haven’t come home, their parents get concerned and the police start searching. Of Jamie and Peter there is no trace, but Adam is found dazed and uncommunicative, his shoes and socks soaked with blood. His catatonic state persists, and even when he recovers sufficiently to talk, he has no memory of what happened in the woods. The police, meanwhile, continue to search, but find nothing.

We then rush forward two decades, to a time when the adult Adam, now an English-accented detective with the Dublin Murder Squad, returns to the same place during a sunny summer uncannily similar to that one all those years ago, to investigate with his colleagues, detectives Cassie Maddox and Sam O’Neill, what looks as if it may be the ritual slaying of a 12-year-old girl, Katy Devlin, whose brutalised body has been found on a druidic sacrificial slab at a partially excavated archaeological site.

Adam, who has renamed himself ‘Rob’ in order to put distance between himself and the traumatic events of all those years ago, was partly inspired to join the Gardai because of that unspecified but dreadful incident (and more importantly, by the imposing men who investigated it), but now that he’s back here in Knocknaree, he is increasingly discomforted by his fogged memories and by a brand-new case that in many ways is reminiscent of the old one.

Initially, Rob is ably assisted by Cassie, who in truth is a better all-round copper than he is, and who provides strong personal support because their friendship surpasses professional buddy-buddyism by a big margin. Having originally joined the Squad as misfits, they naturally gravitated together, and their relationship, though strictly platonic, has become extraordinarily close, the twosome getting on so well that they spend most of their off-duty hours together, cooking, drinking, and laughing raucously at each others’ bad jokes, often into the early hours of the morning, at which point they’ll happily crash on each others’ couches.

In terms of the case, they have a number of lines of enquiry. The archaeologists on the site, most of them students, are a mixed bunch, but the shy, nervous Damien Donnelly, who actually found the body, seems like an oddball, while the site’s unofficial ‘foreman’, an angry hippy type called Mark Hanly, is cocksure and irritable, and immediately catches Rob’s eye as someone he doesn’t particularly like. Equally worth investigating, however, is Jonathan Devlin, Katy’s father, who isn’t just the main organiser of ‘Move the Motorway’, a pressure-group looking to divert a new road, which will otherwise devastate the local natural woodland (and obliterate the archaeological dig!), but who Rob remembers from childhood. Jonathan Devlin wasn’t a respectable middle-class man back then, but a local lout, who used to cause trouble in the surrounding district, and who was certainly hanging around in the woods, or so Rob seems to recall, on that day when his young friends disappeared. At the same time, the introverted Devlin family are themselves under pressure from unknown persons, Jonathan claiming to have received threatening phone-calls, while there is even a suggestion that Katy, a promising dance student, might have been the victim of a recent attempted poisoning. The household itself is in flux, the family members constantly at odds with each other, all of them viable suspects in their own way, while the emotionally vulnerable Rob finds the victim’s fetching older sister, Rosalind, a particularly taunting and distracting presence.

No more distracting, though, than his memories of Knocknaree as a child, before the Celtic Tiger, when the area was poorer but quieter and less suburban, or the mysterious fate of his two friends, which, when one of Jamie’s hair-clips is found near the scene of Katy Devlin’s death, he becomes convinced is connected to this present day crime.

Frustrated by this and by the investigation team’s failure to hit paydirt with any of their leads, and under huge pressure from his boss, gruff old-schooler, Detective Superintendent O’Kelly, Rob opts to try and jumpstart his memories by camping out alone overnight in the woods close to the scene of the crime.

Which will prove to be a catastrophic mistake …

ReviewTana French’s debut novel and dark psychological thriller, In the Woods , made a huge impact on first arrival, sparking a popular TV series and a whole list of Dublin Murder Squad mysteries. It has won almost universal acclaim for its detailed study of an outwardly confident but secretly tormented police hero, whose journey through a complex, distressing murder case is compromised by his memories of a similarly harrowing experience during his own childhood.

The book has also won hefty praise for neatly capturing the Irish zeitgeist of the early 21st century, not just disdaining the dewy-eyed American view of Ireland as a rural idyll of green hills and flame-haired beauties, but also criticising the more materialistic era of short-lived affluence during the 1990s and early 2000s, and putting the deluge of financial difficulties spilling from the ensuing property bubble into a real context.

I approached the book well aware of all this praise but have no real quibbles with any of it. In the Woods does all these things very well indeed. It is also sumptuously written (unusually so for a thriller) and is populated by a plethora of memorable characters.

The hero, Adam ‘Rob’ Ryan, has certainly been to Hell and back. His personal dynamic is quite fascinating, the awful truth lurking in his subconscious but his constant and torturous attempts to recollect it fruitless, a personal trouble that grows steadily more intrusive as the narrative progresses. And yet, Tana French doesn’t use this as a device purely to elicit our sympathy. More than once, for example, it is hinted that the younger Rob’s bizarre memory lapse might have been convenient for him, and that, though he was young when this grim event happened, he wasn’t prepubescent, and so it’s not beyond the bounds of possibly that he himself was in some way culpable. Of course, we readers think we know differently because we can see into Rob’s head, and we know that he is indeed a lost and bewildered soul, but if you think about it, that still doesn’t make him innocent.

The juxtaposition to Rob is of course Cassie Maddox, his fellow investigator and best friend, and in some ways, this is where I have one of my few doubts about In the Woods . For me, Cassie is just a bit too perfect: attractive in the best kind of way (i.e without being overtly, daftly sexy), very empathetic, very intelligent, intuitive, analytical and sharp-eyed. In short, an all-round excellent person as well as a quality copper, she seems a little bit too good to be true, and in that regard detracts quite a bit from our main character, who appears weak and incompetent by comparison, and irritatingly inclined to self-pity.

On top of that, while their close friendship feels natural enough – square pegs will always seek each other out when all the others are round – there are times when the duo strike me as being more like matey students than murder detectives, raucously bantering when off-duty, playing silly jokes on each other while putting the world to rights, staying up all night drinking despite being in the middle of a challenging child-murder investigation. It made a nice change to see male and hero leads presented as friends rather than lovers, but from the very beginning, I couldn’t help wondering how long this was going to last.

But despite all that, which I won’t pretend didn’t spoil the book for me a little, the central relationship still works on the whole, the duo forming an effective focal point for the story, and though they are both remarkably young for homicide detectives, investigating the case believably and authoritatively.

By contrast, most of the other police characters are a little bit stock, though I did enjoy rough-edged Detective Superintendent O’Kelly, whose complete disregard for political correctness reminded me persuasively of my own senior supervisors back in the day, at one point casually dismissing a male officer’s headache as ‘womanly shite!’

The suspects, of course, come thick and fast, and as well as adding depths of mystery, form a well-framed microcosm of Irish society, one of the author’s key aims with this novel, I suspect, showing us everyone from the money men at the top of the tree, who are still looking at ways to expand their empires, to the struggling middle-classes left so bereft after the era of prosperity ended, to the scruffy young idealists who still believe that digging up ancient Irish history is more important than the creation of fast roads to stimulate business. The fact that they’re all framed as potential murder suspects is a clever move. It’s certainly the case that very few people here are completely right or completely wrong, and none are cast as being so pure that they’re beyond murder (not even our main hero).

In addition to all this, Tana French has done her research in terms of police procedure. She’s been accused in some quarters of ditching reality altogether by creating a Dublin Murder Squad when there actually isn’t one. But whether this should be a cause for concern is moot. In the Woods is French’s own book, so in truth she can do what she wants with it, and she never pretends that it isn’t a work of imagination. I do feel that she’s been influenced more than she perhaps should be by the American style of cop fiction, wherein the most gruesome murder cases are handled by a couple of plucky detectives virtually on their own, while in reality – certainly in the UK, and maybe in Ireland too – what appears to be a ritualistic child-murder would see the creation of a dedicated taskforce.

But again, it’s all about entertainment. Tana French is not in the business of writing police textbooks. In the Woods is a thriller, a genre that isn’t honour-bound to replicate real life blow-for-blow, and having reduced the number of investigators, and dispensed with most of those by-the-book protocols that sometimes clutter up crime fiction plotlines, it’s a thriller that fulfills one of its key ambitions nicely by rattling along at an enjoyable pace

It’s a big book, running to 600 pages, but I was so hooked that I read it inside a week. Perhaps it’s a tad overwritten. Beautiful descriptions are not to everyone’s taste in a novel like this, while I found the repeated pop culture references a bit unnecessary, but there can’t be any real complaint when a big, solid chunk of a novel keeps you so engrossed that you get through it so quickly. Strongly recommended.

Regulars on here may know that I often like to round up each of these reviews by casting the work for an imaginary TV adaptation. Well, it’s not required in this case, given the enjoyable Irish television series of 2019.

Published on June 21, 2020 03:04

May 18, 2020

Why I won't be writing about the lockdown

… in the near future.

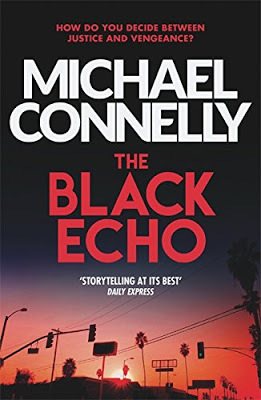

I have to add that caveat because you can never say ‘never’ in any aspect of life. Though for the moment I’m firm. This will be the main gist of today’s chat. In addition to that, however, I’ll update you on where we’re at with my forthcoming new novel, ONE EYE OPEN, and, in reflection of our current dark and silent streets – where in the minds of many, violent criminals are running amok – I offer a detailed review and discussion of a crime classic, Michael Connelly’s astonishing Harry Bosch debut, THE BLACK ECHO.

If you’re only here for the Harry Bosch chit-chat, that’s fine. As always, you’ll find it at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Feel free to pop down there straight away and have your say. However, if you’ve got a little more time to spare, here’s the latest on …

One Eye Open

One Eye OpenThus far, my new novel is still in the pipeline for an August release. I’m loving this cover, which for once actually encapsulates a scene from the novel, and I can now reveal the blurb that will appear on the back of the book.

I won’t say too much more about it at present, except that it’s a free-standing crime thriller set in the leafy southeast of England, where far too many gangsters (both homegrown and otherwise) are getting comfy, and brings in a new set of hardbitten police characters who are determined to bring justice back to the neighbourhood.

But enough from me. Time to let my publishers, Orion, do the talking ...

If the lies don't kill you, the truth will

An electrifying, high-octane thrill ride; the new must-read standalone from a Sunday Times bestseller. You won’t be able to tear yourself away! Dark, gritty and always at the edge of your seat, this unforgettable new outing from master-craftsman, Paul Finch, will appeal to fans of Stuart MacBride, Mari Hannah and Alex Cross.

YOU CAN RUN

A high-speed crash leaves a man and woman clinging to life. Neither of them carries ID. Their car has fake number plates. In their luggage: a huge amount of cash.

Who are they? What are they hiding?

And what were they running from?

YOU CAN HIDE

DS Lynda Hagen, once a brilliant detective, gave it all up to raise her family.

But something about this case reignites a spark in her...

BUT YOU’LL ALWAYS SLEEP WITH...

What begins as an investigation soon becomes an obsession. And it will lead her to a secret so dangerous that soon there will be nowhere left to hide.

ONE EYE OPEN

***

And now, on a gloomier note …

Writing up the lockdown

I’ve recently been fascinated to hear that several editors and agents of my acquaintance have put it online that at present they aren’t interested in lockdown-based novels. Clearly, this suggests that they are being hit with a number of pitches set during this crisis.

On the face of it, this doesn’t surprise me at all. It’s certainly a strange new experience that we’ve all been plunged into, and I’m not just talking about the sight of animals suddenly feeling free to wander our city streets again (though that in itself is an eye-opener and surely worth a book of some sort).

Last Friday night, I took my daily exercise by walking down into Wigan town centre at around 9.30pm.

To describe the place as a ‘ghost town’ would be under-selling it. Streets that would normally be throbbing with nightlife were silent and pitch-dark. Out here in the provinces we are used to seeing our shops boarded, our arcades permanently shuttered. But our pubs? Our restaurants? Our fast food vendors? At that time of the week, there’d normally be crowds of revellers on every street-corner. But on this occasion, quite literally, there was no one anywhere. And all the time I was out – all told, for about three hours – perhaps one or two cars passed me by. The eeriness of it was tangible.

To describe the place as a ‘ghost town’ would be under-selling it. Streets that would normally be throbbing with nightlife were silent and pitch-dark. Out here in the provinces we are used to seeing our shops boarded, our arcades permanently shuttered. But our pubs? Our restaurants? Our fast food vendors? At that time of the week, there’d normally be crowds of revellers on every street-corner. But on this occasion, quite literally, there was no one anywhere. And all the time I was out – all told, for about three hours – perhaps one or two cars passed me by. The eeriness of it was tangible.But if I thought the streets of the town were strangely bereft, how different it was again whenever I veered through parks and finally headed into the woods near my own home. Now, these places wouldn’t be bouncing even on a normal Friday night, but I was still in Wigan, in the heart of Greater Manchester, and yet, with the ambient noise of distant traffic completely absent, I could have been in the New Forest or the Lake District or the Highlands of Scotland.

It was just me, alone amid acres of deep, shadow-filled thickets, over the top of which arched an early summer night-sky ablaze with constellations I hadn’t seen so clearly for many a long year, if ever. Again though, the blanketing silence was so oppressive that enjoyment remained elusive. The odd twinkle of lamplight from a suburban avenue or someone’s back window might penetrate the lattice of branches and leaves, but it added no comfort because there were no sounds of life to accompany it.

It was just me, alone amid acres of deep, shadow-filled thickets, over the top of which arched an early summer night-sky ablaze with constellations I hadn’t seen so clearly for many a long year, if ever. Again though, the blanketing silence was so oppressive that enjoyment remained elusive. The odd twinkle of lamplight from a suburban avenue or someone’s back window might penetrate the lattice of branches and leaves, but it added no comfort because there were no sounds of life to accompany it.No, I’m not at all surprised that some thriller and horror writers are looking to utilise this strange and unearthly experience we’re all sharing – at least as a background, if not the main story.

One bane of our thriller writer lives in the modern age has been the advent of personal technology. You’re rarely alone (and therefore rarely in danger) these days because you don’t need to find a working payphone to call for help. In fact, most of us don’t just carry around the capability to contact others, but the capability to film crimes as they occur, to photograph suspects and even covertly record suspicious conversations. But it doesn’t feel like that at present. Because no one knows from one minute to the next how effectively the emergency services will be able to respond.

Will our overstretched police force rush out to incidents they may consider to be of lesser importance – such as reports of prowlers, or weird noises in a back alley, or a distant scream that may not necessarily have been a vixen on heat – but which to the average citizen, especially alone at night, might be of serious concern? How quickly can we receive medical help if we need it? Will a doctor or nurse even be able to see you if you’re in a state of shock because you’ve had a bad fright?

All these questions, and others like them, have potentially made the lockdown a prime hunting ground for writers whose main job is to scare their readers.

But I have to say – and this is NOT A CRITICISM of those who are seriously considering this – I’m not among them.

There is no doubt that, however this thing ends, it’s been an event we will all remember for the rest of our lives, with varying degrees of pain and sadness. It’s certainly not something any of us will forget, even if we want to try.

The news media have had a field day of course. This is by far the largest story that any of them have ever covered and probably ever will, and they are determined to milk it for everything they can. All of a sudden, everyone on television is an expert. We’ve had anchor men and women making all kinds of apocalyptic statements like ‘this is the new normal’ or ‘we need to adapt to a new world’.

But you know … they might be correct. Even a broken watch is right twice a day.

But you know … they might be correct. Even a broken watch is right twice a day.And that’s one of the most frightening things to me. Are we seriously saying that for the rest of time, or at least the rest of our lives, close social interaction between human beings will not be viable? Frankly, it doesn’t bear thinking about. Will markets, nightclubs, cruise ships and public swimming pools really become things of the past? Do people of a certain age see no future at all where they aren’t confined in their own homes?

It’s certainly the case that there’ll be changes of some sort and that we won’t like them.

I can’t speak for other authors, and would never be so arrogant as to try, but for all these reasons I’m seeing little in the lockdown to get creatively excited about. Partly, it’s because I have to enjoy what I’m writing, even if the subject-matter is traumatic and terrible – in fact usually, the more traumatic and terrible it is, the better I like it. But I write fiction, so when something traumatic and terrible is happening in real life, it’s another matter entirely.

The other thing is that, as I’ve already intimated, we can’t second-guess what the world will be like when the lockdown is over. We’ve already mentioned that there may be significant changes (alternatively, there may be none at all, but at present we’ve no clue). I’m certainly not the only writer I know who is worried that his/her output of fiction thus far may have become irrelevant this last couple of months because it now refers to a different experience of life. Up to very recently, nearly all of us have been writing about a world that had barely heard about the Coronovirus, about societies that couldn’t imagine lockdowns or social distancing.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that we’ll never get back to normal. But even our health experts can’t predict things with any certainty. So, for this reason as well, I’m finding it very difficult dredging up any enthusiasm to write about this disaster.

Am I saying that, as a writer, I’ll never go there ever?

Most definitely not. If complete normality does return, this calamity might eventually be looked back on as nothing more than an ugly blip in the ongoing progress of all our lives. In that case, it may in due course become the perfect nail on which to hang some dark and dangerous stories. But until that time, as long as COVID-19 remains an ongoing tragedy, with thousands of more people dying each week than we are used to, medical staff worked to the bone, and so many of us trapped in our own homes, or facing unemployment or the collapse of the businesses we’ve worked so hard to build, it’ll remain a no-go area for me.

Again, though … this is NOT a criticism of those who are willing to give it a whirl. Everyone is their own person, we are all different, and as I mentioned, there are very understandable reasons why a few of us might be prepared to get stuck in straight away.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE BLACK ECHO by Michael Connelly (1992)

THE BLACK ECHO by Michael Connelly (1992)OutlineHieronymous ‘Harry’ Bosch is an astute, hard-working detective with a sharp eye and a mean-as-sin attitude, not just with the crims, but even with his fellow cops if they aren’t doing the job properly. On top of that he’s well known in his native Los Angeles, having closed some high profile cases and even seeing some of his exploits fictionalised in a pacy TV show (as a result of which he was able to acquire himself an enviable pad high in the Hollywood hills). He ought to be one of the stars of the LAPD’s elite Robbery-Homicide Division, but there are more than a few strikes against him.

First of all, he speaks his mind, even to the brass. Secondly, he likes to go it alone, taking chances and following leads even if the rest of the team aren’t up to speed, his personal safety a secondary consideration. Thirdly, and most recently, he uncharacteristically used excessive force in his pursuit of ‘the Dollmaker’, a serial killer whose grotesque, crypto-artistic depredations had the whole city terrified. Having shot the guy dead while he was unarmed, Bosch was bound to come under the microscope, but in the highly politicised world of the LAPD’s higher ranks – where the unashamed jockeying for position is an embarrassing art-form all of its own – it was the perfect opportunity to divest the department of a loose cannon, hence Harry was busted down to Hollywood Homicide, where he would be safely out of the public eye.

Bosch is a professional, though, and gets on with the job, and when sent to check out a body found in a drainage pipe near the Mulholland Dam, he doesn’t share everyone else’s casual assumption that this is just another junkie who’s OD’d, even though the body is that of Billy Meadows, a known heroin addict who has died with a hypo in his arm. Harry doesn’t merely call on his basic detective skills to deduce that Meadows was murdered, he also recognises the victim personally.

A Vietnam vet, Bosch was once part of an infantry unit whose speciality was underground infiltration, pursuing the Viet Cong through their limitless networks of tunnels. Meadows was part of the same outfit, which, given that his corpse was dumped in a tunnel, is surely no coincidence.