Paul Finch's Blog, page 4

December 6, 2022

Festive eeriness from Christmases long ago

Well, it’s almost that time of year again. It’s cold and gloomy out there, but fairy lights are twinkling in windows, street vendors selling fir trees on foggy corners, and shop windows glowing with toys, tinsel and that distinctive warm and rosy light.

Yes, Christmas is just around the corner, so that’s what I’ll be talking about today. To begin with, I’m going to read you all a brief extract from SPARROWHAWK, my Christmas novella of 2010, which made it onto the final ballot of the British Fantasy Awards. But in addition to that, I’ll be reviewing THE HAUNTING SEASON, an anthology of atmospheric Christmas and winter ghost stories, published for the festive season last year by Sphere (unusually, with no individual editor credited). Apologies to all concerned that this review is in effect a year late, but I only acquired this book late last December, so there was no real opportunity to review it then in time for Christmas Eve. It’s still available anyway, so hopefully this review will not be wasted.If you’re only really here to let me entice you to THE HAUNTING SEASON , then by all means take a sleigh ride to the bottom end of today’s column where you’ll find the review, as usual, in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

On the other hand, you could bear with me a little longer, and I’ll take you to another haunting Christmas …

Long, long ago

SPARROWHAWK remains my personal favourite piece of work. I wrote it intentionally as my ode to Victorian era ghostly fiction but also to the Christmas season, my favourite time of year, and a celebration that I’ve never really been able to separate from thoughts of the supernatural.

As a child, the magical, mystical nature of Christmas was almost tangible to me. It wasn’t just the midwinter atmosphere: the long darkness, the icicles, the snow flurries. Or that huge range of Christmas folklore and mythology: the elves in the evergreens, Loki and the mistletoe spear, St Boniface and the sacred oak, Belsnickel, Krampus etc etc. It was the fact that this was a holy feast, it was Heaven-sent, which basically gave you full permission to believe in the fantastical.

As a child, the magical, mystical nature of Christmas was almost tangible to me. It wasn’t just the midwinter atmosphere: the long darkness, the icicles, the snow flurries. Or that huge range of Christmas folklore and mythology: the elves in the evergreens, Loki and the mistletoe spear, St Boniface and the sacred oak, Belsnickel, Krampus etc etc. It was the fact that this was a holy feast, it was Heaven-sent, which basically gave you full permission to believe in the fantastical. The Son of God had genuinely been born in a stable in Bethlehem on Christmas Day over 2,000 years ago, an angel taking the glad tidings to local shepherds, wisemen from the East following a star so they could pay tribute. A miracle for sure, which surely meant that other miracles happened around this time of year too.

Father Christmas, as we called him in Britain (or Santa Claus in the States, Sinterklass in the Netherlands, Père Noël in France) was real (of course he was real!) because he was a saint, who if he didn’t actually personify in the shape of a chubby old man in a red cloak and a fur-trimmed hood, at least imbued the season with jollity and good will – something that happened at no other time of year I was aware of.

Many supposedly true ghost stories I’d heard involved manifestations specifically at Christmas.

It’s a moment when ‘the hopes and fears of all the years’ are close to us, and so the spirits – in that time-honoured fashion of A Christmas Carol – often visit as heralds, bearing warnings about the future or disapproving messages concerning the way we’ve lived our lives to that date.

(One of the eeriest I ever heard featured Geoffrey de Mandeville, a brave knight of the 12th century, but in later life a robber baron, who was doomed after death to ride around the perimeter of his long-demolished castle every Christmas Eve in a cloak and armour soaked with the blood of his victims).

(One of the eeriest I ever heard featured Geoffrey de Mandeville, a brave knight of the 12th century, but in later life a robber baron, who was doomed after death to ride around the perimeter of his long-demolished castle every Christmas Eve in a cloak and armour soaked with the blood of his victims). In light of all that, it seemed perfectly natural to me to both read and write ghost stories at Christmas. The two clearly went hand in hand, and of course it wasn’t just me. Umpteen classical authors had already done the same thing.

As such, those who follow this column regularly will know that, each year in December, I try to publish a free-to-read Christmas ghost story on here. The truth is that it’s often a toss-up whether I’m able to do this because time doesn’t always allow (though I’ll be trying again in the days ahead). But

SPARROWHAWK

was a particularly good effort on my part, if I say so myself, even though it did eventually run to just under 30,000 words.

As such, those who follow this column regularly will know that, each year in December, I try to publish a free-to-read Christmas ghost story on here. The truth is that it’s often a toss-up whether I’m able to do this because time doesn’t always allow (though I’ll be trying again in the days ahead). But

SPARROWHAWK

was a particularly good effort on my part, if I say so myself, even though it did eventually run to just under 30,000 words. It was first published by Pendragon Press at Christmas 2010 and later short-listed for the British Fantasy Award, only losing out to my good mate and all-round excellent writer, Simon Clark, so I can hardly complain. Despite that, I remain completely happy with this novella, genuinely feeling that it hit every target I was aiming at. But of course, I can’t really be the judge of my own work; that’s up to my readers. However, a couple of years ago, with the Pendragon version now long out of print, it was republished in paperback by my own small publishing house, Brentwood Press, and released on Kindle and Audible as well, the latter version admirably read by that wonderful actor, Greg Patmore.

I won’t say anymore because this is turning into a bit of a hard sell, which is not what I wanted to do. Instead, I’ll let the book do the talking, or a little bit of it. Here, as promised, is a short extract from SPARROWHAWK , which I recorded a couple of days ago. Perhaps give it a listen if you’ve got a few minutes spare, and see what you think, hey?

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE HAUNTING SEASON

by Various (2021)

THE HAUNTING SEASON

by Various (2021)

A beautifully presented anthology of original Christmas and winter-themed ghost stories, mostly set in the past and with a decidedly Gothic aura. Before we get into it, I’ll let Sphere, the publishers, give you their own official blurb:

Winter, with its unsettling blend of the cosy and the sinister, has long been a popular time for gathering by the bright flame of a candle, or the warm crackling of a fire, and swapping stories of ghosts and strange happenings.

Now eight bestselling, award-winning authors – master storytellers of the sinister and the macabre – bring this time-honoured tradition to vivid life in a spellbinding collection of new and original haunted tales.

Taking you from a bustling Covent Garden Christmas market to the frosty moors of Yorkshire, from a country estate with a dreadful secret to a London mansion where a beautiful girl lies frozen in death, these are stories to make your hair stand on end, send shivers down your spine and to serve as your indispensable companion to the long nights of winter.

So curl up, light a candle, and fall under the spell of The Haunting Season …

The telling of ghost stories at Christmas and in the depths of winter is one of our most time-honoured literary traditions. I’ve waxed lyrical many times on this blog about the joy to be found in spinning spooky yarns while seated around the fire with snow-laden winds whipping at the window.

The likes of Charles Dickens and MR James, of course, dined out on the tradition, while even Shakespeare mentioned it. Anyone recall the throwaway line in A Winter’s Tale ? ‘A sad tale’s best for winter. I have one. Of sprites and goblins.’

Many writers have followed in these venerable footsteps since, with the net result that Christmas, or midwinter – because not all the stories in The Haunting Season are specific Yuletide celebrations – now sits alongside Halloween as the time for eerie tales. And I am so delighted, I can’t stress that enough – I am SO delighted – that now at last, after what seems like an eternity, we see a major publisher getting in on the act.

Though no single editor is credited for The Haunting Season , it excites me no end to see that this beautifully bound and illustrated anthology comes to us from Sphere, an imprint of Little, Brown. Does this mean that we’ll see further commissioning of original short fiction by the major houses? Time (and sales) will tell. But I’m cautiously optimistic, because this outing in particular has been quite successful.

On the subject of caution, that is one of the most notable features of this particular collection, I feel. It’s a cautious, or careful, exploration of the supernatural field, rather than a full-on dive into it. There are lots of effective tales here, though very few (if any) absolute spine-chillers, and nothing that is likely to shock. Of the eight stories contained here, there is only one I’d classify as a ‘horror story’, and that one is also subtle and meaningful. But there is also much here about subtext and undertone, the majority of which comes from a feminist persuasion. Which is absolutely fine by me, and works very well in this context, and which is also understandable because of the eight contributing authors, seven are women.

I will admit to being a tad perplexed that the bulk of these tales are set in that timeless Victorian/Edwardian timeloop, where so much ghostly fiction of the classical variety dwells. That makes for a slightly less diverse collection than I was expecting, but even now in the 21st century, that era remains our go-to period for Gothic fiction, so one can’t complain too much.

There is also, maybe, an over-preponderance of upper-crustiness in The Haunting Season . There are several country house tales here, while more than a few characters derive from the ruling class. But I reiterate, this was often the way of it with the Victorian ghost story tradition, so I see no real harm.

The stories themselves, without exception, are exquisitely written, are populated by memorable personalities (Natasha Pulley, for example, utilising characters from her very successful Watchmaker of Filigree Street series), and hit us with a range of supernatural antagonists.

Inevitably, of course, in that great custom of the Victorian ghost story, there are many mysteries to be solved.

For example, in Laura Purcell’s The Chillingham Chair , a spirited young woman is unable to attend her sister’s wedding thanks to a broken foot incurred during a riding accident. However, the wheelchair she is confined in now seems to develop a life of its own and attempts to impart a warning message, possibly about the potential fate of her sister …

The one contemporary tale I referenced, The Hanging of the Greens by Andrew Michael Hurley, presents us with a story inside a story, and a protagonist who must venture into the back of beyond to get the answers he seeks, though I found this contribution to the book particularly disturbing – it’s certainly a new twist on the festive chiller – so more about this one later.

Other stories meanwhile, while not exactly mysteries, hint strongly at the troubled pasts of those individuals participating, and leave much to the reader’s own (hopefully dark) imagination.

Bridget Collins’s A Study in Black and White is a great example. In this eerie outing, an unpleasant man on the run from his misdemeanors rents a 17th century house in the countryside. Intent on staying there alone, he soon becomes aware of an unseen presence, a presence that enjoys a game of chess, though it appears even more to enjoy winning.

Likewise in Thwaite’s Tenant by Imogen Hermes Gowar, the central character is displaced from one threatening location to another, which turns out to be even worse, though the exact details of what happened there are initially elusive. I enjoyed this one thoroughly, so a little more on this later.

Perhaps the most mysterious of all the stories in The Haunting Season is Monster by Elizabeth Macneal. It features a selfish protagonist on the trail of an elusive prize and entering a realm so soaked in mythology that it’s almost unreal. More on this one later, too.

For straightforward terror, meanwhile, though with a deep subtext, we go to Kiran Millwood Hargrave’s Confinement , wherein a woman suffering in the grip of a terrifying supernatural foe, may actually be at the mercy of her own tortured psyche. A poignant tale, this one, as well as a scare-fest, it has meaning far beyond the pages and remit of this anthology, so more about this one later as well.

Equally strange and delightful reads are provided by Natasha Pulley with The Eel Singers , in which a close group of friends take a trip out of London to the wintry fen country, only to encounter some locals who are not quite the welcoming crowd they anticipated, and Jess Kidd with Lily Wilt , in which a professional photographer of the dead falls in love with his latest project, a beautiful and delicate young woman recently deceased, and uses black magic to restore her to life, only to find that she is a long way from the woman she once was (or is she?).

All round, The Haunting Season does exactly what it says on the cover, delivering a bunch of original short fiction, all expertly and sumptuously written (there isn’t one dud in that regard), all flavoursome of the deep winter, and all offering hints of that gentle horror, or should we perhaps say ‘pleasing terror’ that so earmarks the traditional ghost story for Christmas. If that’s what you’re looking for, you’ll find it here.

And now …

THE HAUNTING SEASON – the movie

Okay, no film maker has optioned this book yet (as far as I’m aware), and I honestly don’t know how likely it is, but as this part of the review is always the fun part, here are my thoughts just in case someone with cash decides that it simply has to be on the big screen in time for next December.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium of ghost stories. Of course, no such film or TV series can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual but festive circumstances, which require them to relate spooky tales. It could be that they’re marooned at a snowbound coaching inn and keeping each other company around the Christmas Eve fire, or perhaps are regaling Mr Dickens with recollections of their own experiences after he amuses his guests at a Yuletide dinner party with the first chapter of A Christmas Carol.

Without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

Thwaite’s Tenant (by Imogen Hermes Gowar): A woman, fleeing with her child from a brutal husband, seeks refuge in a desolate house used by her father for his assignations with various mistresses. But she finds it a dark abode where the many memories of male cruelty refuse to lie at rest …

Lucinda – Charlene McKenna

Father – Jim Carter

Mrs Farrar – Rita Tushingham

Monster (Elizabeth Macneal): A younger son, insanely jealous of his horticulturist brother and unmanned by his beautiful wife, seeks greatness by searching for dinosaur bones on the Jurassic Coast. When he uncovers a fully intact plesiosaur skeleton, it’s a wondrous moment, but it comes at a ghastly psycho-supernatural price …

Victor – Darren Boyd

Mabel – Kelly MacDonald

The Hanging of the Greens (by Andrew Michael Hurley): A former vicar recalls the event that cost him his faith: a trip to a lonely farm in the snowswept Bowland hills, to offer an apology from a troubled parishioner to the couple he believes he offended. But a terrifying truth awaits him there …

Edward Clarke – Dominic West

Joe Gull – Jack O’Connell

Confinement (by Kiran Millwood Hargrave): A woman returns to England from India pregnant. But the difficult labour and birth is made worse by the story she has heard that her nearest neighbour was an evil woman hanged for baby-farming. Is the nightmarish figure that now haunts the new mother a figment of post-natal depression, or something even more terrible? …

…

Catherine – Sophie Turner

Published on December 06, 2022 06:06

December 1, 2022

Never Seen Again hangs in place of honour

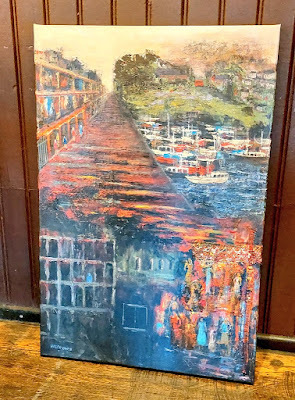

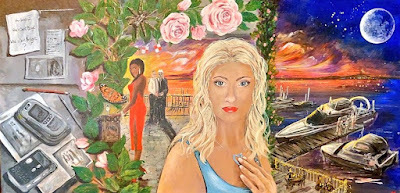

As you can see, Helen Roberts’ remarkable and beautiful interpretation of my recent crime novel, NEVER SEEN AGAIN, is now framed and hanging on the wall in our living room, in a place of honour.

When we originally set out on this road, I had no idea what the final outcome would be. But here it is … and even though much has happened, I still feel hugely honoured that anyone, let alone someone as talented as Helen, would take it on themselves to create an original painting based on any book of mine. I appreciate that my snapshot doesn’t really do the painting justice, but as Helen has recently sent through some notes outlining the main influences she took from the novel, I thought I’d get up close and a bit more personal with the picture, and relay these to you myself on video.

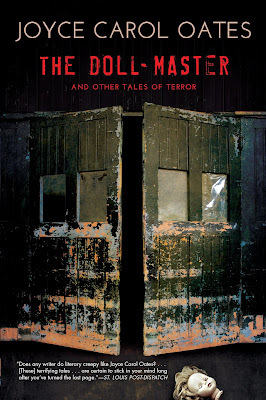

You’ll find that below, along with some short story news. In addition to that, because we’re again on the subject of mystery-thrillers but with an undercurrent of the arts, I’ll be reviewing THE DOLL-MASTER, another exquisite collection of shorts by that mistress of literary dark fiction, Joyce Carol Oates.

If you’re only here for the Oates review, shoot down to the lower end of today’s blogpost, where you’ll find it, as usual, in the Thrillers, Chillers section. If on the other hand, you haven’t yet had enough for my novel-to-painting chatter, stick around for …

All on canvas

I don’t want to repeat too much of my previous blogpost today, so I’ll keep this introduction short and sweet. You’ll hopefully recall that, last summer, a challenge was put to the Birmingham Art Zone to transform my crime novel of 2022, NEVER SEEN AGAIN , into a single canvas.

In my mind, this would be an artistic interpretation of the whole novel, rather than an alternative book-cover or an advertising poster, though in speaking to the artists interested in participating, I made no requirements at all. It was to be entirely up to them what they did (a little bit like the notes I send out to those writers who compete to appear in my

TERROR TALES

anthologies: “DO what you DO”).

In my mind, this would be an artistic interpretation of the whole novel, rather than an alternative book-cover or an advertising poster, though in speaking to the artists interested in participating, I made no requirements at all. It was to be entirely up to them what they did (a little bit like the notes I send out to those writers who compete to appear in my

TERROR TALES

anthologies: “DO what you DO”). You may ask why Birmingham was chosen instead of my native Northwest. Well, that’s because Birmingham’s Westside Business Improvement District, with whom I’ve become very friendly in recent years, were hugely supportive of the idea and threw it out to their local artists.

The three painters who eventually undertook the challenge – Helen Roberts, the eventual winner, and runners-up, Helen Owen and Paula Gabb – did, frankly, an incredible job. Any one of their finished works could have taken first place.

It was extraordinarily difficult to choose between them, especially as it was live on news camera in the Velvet Music Rooms and the ladies were all standing there in front of me, when the decision was made.

It was extraordinarily difficult to choose between them, especially as it was live on news camera in the Velvet Music Rooms and the ladies were all standing there in front of me, when the decision was made. Having pondered the winner for a couple of weeks now, all I can really say about why I chose this one over the others is because of the way the central figure in it, Jodie Martindale, immediately hooked me with those hauntingly beautiful eyes, and said: “Come and find me, please. I was kidnapped six years ago. No, we don’t know who by. Yes, I’ve never been seen or heard from since. But I’m still alive. So please, send someone to find me.”

But enough. Rather than keep waffling on via keyboard, here’s a video I shot once we’d got the painting framed, in which I present some of the info that was transferred over to me by Helen Roberts herself. A quick word of warning: if any of you haven’t read the novel yet, and are still hoping to, there may be one or two SPOILERS here, so it might be an idea to only watch this video when you’ve turned the final page.

So, there we go. Apologies for my slightly rough and ready approach and shoddy camerawork. I’m no expert at this sort of thing, but hopefully you’ll find it interesting. (One detail I’ve stupidly neglected to mention, is the pendant that Jodie is touching so delicately at her throat. That is the symbol of the United Nations Blue Heart campaign, which raises awareness around the globe about human trafficking. A beautiful touch of Helen’s own).

Short story updates

I have one or two other things to report as well, which I’m quite excited about.

Proof that my TERROR TALES anthology series is as strong as it ever was, if not stronger, has finally arrived in the form of a number of the stories included in last year’s TERROR TALES OF THE SCOTTISH LOWLANDS gaining the attention of Ellen Datlow, that inestimable editor of the Best Horror of the Year series along with countless other high-end horror anthos.

To start with, Steve Duffy’s

The Strathantine Imps

, which for me absolutely nails the folk horror vibe I look for in this series but in an all-new and subtly terrifying way, has been chosen for full reprint in

BEST HORROR OF THE YEAR 14

(as I knew it would – just ask the author, and he’ll confirm that I told him this on first reading it).

To start with, Steve Duffy’s

The Strathantine Imps

, which for me absolutely nails the folk horror vibe I look for in this series but in an all-new and subtly terrifying way, has been chosen for full reprint in

BEST HORROR OF THE YEAR 14

(as I knew it would – just ask the author, and he’ll confirm that I told him this on first reading it). But the laurels don’t end there. Five other stories featuring in LOWLANDS have been singled out for special mention in Ellen’s annual longlist of the year’s best horror, which also appears in BEST HORROR OF THE YEAR 14 .

They are: The Moss-Trooper by MW Craven, Drumglass Chapel by Reggie Oliver, Herders by Willie Meikle, Birds of Prey by SJI Holliday and The Fourth Presence by SA Rennie.

Now, all told, that’s a substantial chunk of TERROR TALES OF THE SCOTTISH LOWLANDS , I hope you’ll agree. And as editor of the series, I’m really delighted that we’re winning such acclaim. If you’d like to know what the TERROR TALES books are all about, you can always check them out for yourself … HERE .

On a personal but not entirely dissimilar note, I’d like to mention, if you’ll permit me, that a story of mine from 2021,

Uncaged

, as first published in

THEY’RE OUT TO GET YOU

, edited by Johnny Mains, has also made the longlist in

BEST HORROR OF THE YEAR 14.

I must admit to being very happy with this. I don’t get time to write many short stories these days, so when I do put them out there, it’s gratifying to see them recognised.

On a personal but not entirely dissimilar note, I’d like to mention, if you’ll permit me, that a story of mine from 2021,

Uncaged

, as first published in

THEY’RE OUT TO GET YOU

, edited by Johnny Mains, has also made the longlist in

BEST HORROR OF THE YEAR 14.

I must admit to being very happy with this. I don’t get time to write many short stories these days, so when I do put them out there, it’s gratifying to see them recognised. Uncaged is a slightly unusual one for me in that it’s set in the distant past (a hint of future novels to come, perhaps?), at the height of the Roman Empire in fact, but its contents concern events that I trust will be familiar enough to put a thrill of fear even into the most modern bloodstream.

Hopefully, without beating my own drum too much, Can I also draw

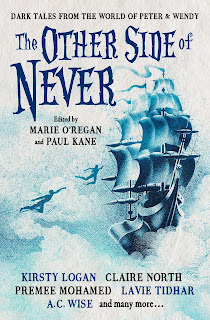

Hopefully, without beating my own drum too much, Can I also drawyour attention to another short story of mine, No Such Place , which will appear next year in a the fantasy/horror anthology called THE OTHER SIDE OF NEVER . I think you can see for yourself that this one will contain dark stories inspired by the many legends surrounding Peter Pan. The editors in this case are the ever-energetic Paul Kane and Marie O’Regan.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE DOLL-MASTER

by Joyce Carol Oates (2016)

THE DOLL-MASTER

by Joyce Carol Oates (2016)

Joyce Carol Oates is one of the most revered authors working in America today, and the creator of a phenomenal body of work, which includes 58 novels, plus numerous plays, novellas and collections of short stories and poems. She’s also been the recipient of countless awards and honours and has five times been shortlisted for the Pullitzer Prize. Fortunately for those of us who prefer our fiction dark, Oates, while a keen advocate for social justice, often focusses on the grimmer aspects of life in her writing, and as such is a regular creator of high-quality horror and thriller literature

Fans of the short form are particularly well-served by Oates, whose eerie and mysterious tales have appeared regularly in magazines and anthologies, and as already stated, are often published in special single-author collections, all of which are worth checking out. The Doll-Master , which appeared in 2016, is only one such. Here is the blurb that graced its back cover:

Six terrifying tales to chill the blood from the unique imagination of Joyce Carol Oates.

A young boy plays with dolls instead of action figures. But as he grows older, his passion takes on a darker edge...

A white man shoots dead a black youth creating a media frenzy. But could it have been self-defense as he claims?

A nervous woman tries to escape her husband. He says he loves her, but she's convinced he wants to kill her...

These quietly lethal stories reveal the horrors that dwell within us all.

One of the most interesting aspects of Joyce Carole Oates’ writing in the darker genres – and we shouldn’t be surprised by this, because her remit goes much further afield than that – is her ability to spin scary stories that are a world away from the more conventional realms of ghosts, monsters, goblins and psychopaths. I mean, don’t get me wrong, she’s more than capable of straying into all these territories, especially the latter. But Joyce Carole Oates’ fiction is invariably set in the mundane realities of everyday folk.

Terrible things invariably happen, but usually in circumstances the majority of us would recognise: broken homes, dysfunctional families, impoverished neighbourhoods, the aberrant minds of people who are basically unable to cope. She doesn’t judge. You almost never get anyone who is evil for evil’s sake. Likewise, though there is gore and violence, it rarely goes over the top. And contrivance is never on show. There is certainly nothing in The Doll-Master that would make you think the situation couldn’t genuinely occur. This makes every one of her short stories so much more of a gut-punch than it would be otherwise. It also may explain there is something of a pattern in this particular collection, quite a few of the stories ending ambiguously, leaving distinct uncertainty in the mind of the reader, and strongly hinting that in real life, serious problems are never just packaged away and done with. There will always be an aftermath, there will regularly be a second twist in the story that you never saw coming.

As The Doll-Master contains only six stories (all quite lengthy, novelettes really), I won’t do what I usually do with collections of stories, which is select the ones I liked the best and talk about them in extra detail. Instead, I’ll run through them all in chronological order. And as I always enjoy doing some fantasy casting at the end, I’ll do the same here, only will invent a TV series adaptation and pick out a few actors for each episode (all in the spirit of having a laugh of course).

The Doll-Master

Young Robbie falls in love with his female cousin’s new Barbie doll and steals it from her bedroom after she suffers an untimely death. But when his irritated father takes it away, he grows up in desperate need of replacements, and thus embarks on a mission to secretly collect abandoned dolls. At the same time, very disturbingly, local children start disappearing …

The unreliably narrated tale of an out-and-out psychopath, both his formation and the execution of his crimewave, as seen through his own eyes from earliest youth to young adulthood. Oates is renowned for her grim slices of ‘real-life’ horror, but even though, as with most other stories in this book, the ending to this whistle-wetter is left open (to an extent), it’s probably one of the closest in the book to the traditional macabre tale. Not because it’s filled with slasher-type nastiness, but because fear and dread are the thing, and Oates drip-feeds them in with a true master’s touch. A conte cruel from the top drawer.

In our imaginary TV show:

Robbie – Harry Gilby

Mother – Lena Hall

Soldier

Brandon Schrank, a young white misanthrope, is charged with murder when he shoots a black youth in what he claims is self-defence. The country is soon divided over the matter and a heated, even violent debate follows, neither Schrank’s supporters nor his detractors particularly concerned about whether he is innocent or guilty, instead concentrating on trying to best each other. The mystery persists, though. What happened that night when Schrank says he was attacked? …

Probably the most thought-provoking story in the book, an assessment of America’s current race issues and bizarre gun culture, and the massive passions generated on both sides of the debate, all seen through the prism of a fictional but melodramatic news story in which the actual facts are difficult to ascertain. Neither a thriller nor a horror story, but bone-chilling and prophetic in the extreme when you consider that it was written several years before 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse became famous for shooting three people during a public order situation in Wisconsin.

In our imaginary TV show:

Brandon Schrank – Tom Holland

Gun Accident: An Investigation

Hanna, a schoolgirl from a humble home, is delighted when her favourite teacher, the beautiful, stylish and sophisticated Mrs McClelland, requests that she access her palatial home several times while the McClellands are out of town to look after the plants and the cat. Neither Hanna nor her teacher are aware of the tragedy that will unfold when Hanna’s drug-crazed cousin, Travis, learns about this convenient arrangement …

A dark and disturbing little vignette, which is certainly a crime story, but not something you’d classify as a mystery or a thriller. If anything, it’s more a slice of social drama, a grim tale that you could really picture happening in towns where there are haves and have-nots, and where those at the very bottom of the scale have slipped into anarchic oblivion (a situation that rarely resolves itself with one-off tragedies). Yet another powerful read.

In our imaginary TV show:

Hanna – Parker McKenna Posey

Travis – Chosen Jacobs

Mrs McClelland – Julia Stiles

Equatorial

Audrey, a neurotic heiress, accompanies her ambitious academic husband on a holiday to Ecuador, but in due course becomes convinced that he has not just brought a secret mistress along with him, who is somewhere in the party they are travelling with, but also that his plan is to commit murder while they are here and so clear the way for a new relationship …

The longest story in the book and for me the least effective, though that’s primarily because, though this is yet another tale in which the author purposely cuts the narrative short, allowing us to insert the denouement ourselves, in this instance we seem to take an awfully long time getting there, and when we did, I couldn’t help feeling short-changed. This is all the more disappointing because the tension and suspense that Oates generates in the body of this narrative is immense. Equatorial has all the basics of a dark and intense psychological thriller, but in this case the lack of pay-off is detrimental.

In our imaginary TV show:

Audrey – Natascha McElhone

Henry – Patrick Dempsey

Big Momma

Violet’s over-stressed single mom moves them both to a new town and in Violet’s case, to a new school. Dumpy and unattractive, Violet feels lonely and self-conscious among all these new kids, but gradually befriends an eccentric local family, who make her welcome in their ramshackle home and keep promising that one day they will introduce her to a mysterious personality known only as Big Momma …

Probably the most ‘horror’ of all the horror stories in this collection, and easily one of the best in terms of its gleefully fiendish premise. We’re in vintage Joyce Carole Oates territory with this chiller, focussing on one of society’s misfits whose efforts to find acceptance backfire on her in the most gruesome and ghoulish way, though in this case she falls prey to her fellow misfits (proving that there is almost nobody nice in the world of Ms. Oates). This is one the old Pan Books of Horror Stories would have been happy to publish. Marvellously horrible.

In our imaginary TV show:

Violet – Milly Bobby Brown

Mr Clovis – Holt McCallaney

Mystery Inc.

A serial poisoner working under the fake name Charles Brockden is intent on acquiring a beautiful, old-fashioned bookshop in an idyllic seaside town, and so launches a careful scheme to dispose of its current owner, the elegant and friendly Aaron Neuhaus. He’s done it before and anticipates no problems, but this time finds himself in a new and frightening predicament …

We end on another high note, with just the sort of low-key suspenser that Oates excels in, something that wouldn’t be out of place in Alfred Hitchcock Presents or perhaps Thriller , as once fronted by Boris Karloff. It doesn’t really matter that in this one you can see the end coming. What works best here is the cat and mouse game played between two like-minded protagonists, the stakes at the end of which could not be higher. Thoroughly enjoyable and a fine way to found off what is overall an exceptionally good if quickfire selection of distressing stories.

In our imaginary TV show:

‘Charles Brockden’ – James Frain

Aaron Neuhaus – Ian McKellen

So, that’s The Doll-Master . I’ve been a Joyce Carole Oates fan for many a year now, usually having read her short stories in anthologies and magazines. This was the first of her actual collections that I made an effort to get hold of, and it certainly won’t be the last. So, keep tuning into this blog, and you’ll find much more from America’s grand mistress of dark letters.

And you could do a lot worse than start with this one.

Published on December 01, 2022 03:16

November 17, 2022

A first - and a fantastic 'fusion of the arts'

All I can really talk about today is what happened to me yesterday. Because it was, without doubt, the best day of my working life. It was a day in which three very talented artists each presented to me their own interpretation of my latest novel.

Yes, that’s correct. Three remarkable ladies had each taken the trouble to condense my 130,000-word thriller, NEVER SEEN AGAIN, into a single canvas. The only role I had yesterday was to attend this presentation in Birmingham and choose the winner, but believe you me, that was no small thing.

So, today’s blog will tell the story of how all of this came to pass.

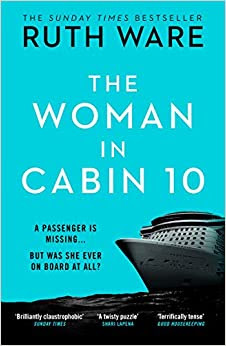

In addition today, on the subject of solid mystery-thrillers (sorry, blatant bit of self-glorification there), I’ll be reviewing Ruth Ware’s compelling novel, THE WOMAN IN CABIN 10 . Anyone who’s only here for that and isn’t particularly bothered about the book-to-painting story, scoot straight down to the lower end of today’s column, the Thrillers/Chillers section, where you’ll find that review.

In the meantime though, why don’t we discuss …

A fusion of the arts

A fusion of the arts

That’s the way this incredible new idea was first pitched to me by Mike Olley (left), boss of Birmingham’s Westside BID, and his wife, Lorraine Olley (below), a popular singer, businesswoman and media personality down in the West Midlands, while we were all sitting in The Brasshouse pub in Birmingham last summer, talking generally about our careers and interests.

I’d just happened to mention that I was an amateur art collector, and was toying with the idea of commissioning an artist to produce a painting about the life and (often dirty) work of my main cop character, DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg, for when I recommence the Heck series next year.

I’d just happened to mention that I was an amateur art collector, and was toying with the idea of commissioning an artist to produce a painting about the life and (often dirty) work of my main cop character, DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg, for when I recommence the Heck series next year. What I’d been looking for, I said, was an actual painting. Not just a new book cover that would work for retailers, and not an advertising poster. But an original piece of art, condensing many aspects of Heck’s life and investigations into a single image that we could then use as part of the promotional campaign in 2023, but which would mainly be for hanging on the wall in our lounge.

Mike and Lorraine seemed fascinated by this concept. ‘A fusion of two art-forms,’ they called it. ‘That would be something different and new.’

On reflection, I had to agree. The creation of book covers is an art in itself of course, while high quality illustrations have been used inside books throughout the entire history of publishing. But this would be slightly different. This challenge would require an artist who was not an illustrator or a book jacket designer to interpret an entire novel in one image.

The more we discussed it, the more it became evident to me that Mike and Lorraine were seriously interested in the subject. In the end, Mike suggested that, while my plan to commission an artistic portrayal of Heck was something I already had in hand, he would be interested in doing something similar with my more recent non-Heck thriller,

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

.

The more we discussed it, the more it became evident to me that Mike and Lorraine were seriously interested in the subject. In the end, Mike suggested that, while my plan to commission an artistic portrayal of Heck was something I already had in hand, he would be interested in doing something similar with my more recent non-Heck thriller,

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

. Birmingham Art Zone

Mike put the concept to the Birmingham Art Zone, a group of highly talented artists dedicated to bringing artistic endeavour to the whole community of the West Midlands. Only then – certainly in my case – did it become apparent just what an enormous challenge this was going to be.

NEVER SEEN AGAIN is a 400 pages long thriller, concerning a violent kidnapping that has now become a cold case, a burned-out reporter trying to revive his career, corruption in the City of London, organised crime, a serial murderer called the Medway Slasher, a whole nest of dirty cops and the disgraceful scandal of international sex-trafficking.

How do you ask an artist to depict all of that in a single frame?

Well, that wasn’t for me to say. I only wrote the book. The three intrepid artists who undertook the challenge – Paula Gabb, Helen Owen and Helen Roberts – would need to decide for themselves what went into their pictures and what was left out. And thus they embarked on ‘this massive task’ as one of them described it to me, beavering away in their respective studios, with only a couple of months realistically available in which to create.

A difficult choice

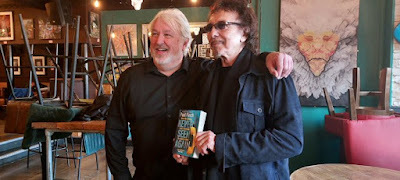

Roll forward to this week, and we come to the grand unveiling – Judgement Day, as Lorraine cheerily called it – held on November 16, down at the Velvet Music Rooms on Broad Street, the artery at the beating heart of Birmingham’s cultural life.

The press were in attendance, which was lovely to see, alongside some very special guests indeed, not least Tony Iommi, legendary lead guitarist of rock/metal pioneers Black Sabbath. That made it even more unbelievable for me, having been a heavy rock fan since I was at junior school, so the moment when Tony asked me to sign a copy of

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

for him (see right) was almost more than I could handle.

The press were in attendance, which was lovely to see, alongside some very special guests indeed, not least Tony Iommi, legendary lead guitarist of rock/metal pioneers Black Sabbath. That made it even more unbelievable for me, having been a heavy rock fan since I was at junior school, so the moment when Tony asked me to sign a copy of

NEVER SEEN AGAIN

for him (see right) was almost more than I could handle.When the paintings were revealed one by one, each one then presented to me by the artist responsible, I was actually very unnerved. I’ve had no formal training as an art critic, I just know what I like. But on this occasion, quite frankly, I liked all of them.

At no stage had I prescribed what I wanted the artists to paint (who would I be, to tell an artist how to do their job?). But secretly I’d hoped, as I’ve already hinted, that I wouldn’t just get an alternative piece of jacket art or what you might describe as a screen-grab, i.e. a single moment from the novel represented in oils. I was looking for an interpretation of the whole thing, if that was possible.

And as it turned out, it was … because that is exactly what I got in all three cases.

If I tell you now that none of the three were losers and that I loved them all equally, and only in the end chose one because that was the purpose of the exercise, you might consider it a cliché tossed out casually to prevent anyone feeling bad. But actually it would be 99.9% true.

I couldn’t believe the standard of the three images I was confronted with.

I couldn’t believe the standard of the three images I was confronted with. All three artists had taken a deep, deep dive into the novel, producing wondrous and tumultuous depictions, any of which, even taken out of context, would immediately have spoken to me about my book.

Of course, none of this made it any easier, choosing, but though Helen, Helen and Paula were all standing watching at the time, to their everlasting credit they remained bright-eyed and happy all the way through. They’d all bought fully into the concept and were delightful with me both before and after the final decision was made.

Photo-finish

The two runners-up, in no specific order, were Paula Gabb’s and Helen Owen’s paintings.

Paula’s piece, as seen above, took a ‘journalistic’ angle on the book, recreating all the salient moments in the narrative visually, throwing them together as though they were photographs on a storyboard, connecting them with concise but crucial notations.

Her attention to detail was astonishing: nothing relevant from any of those key moments was absent from her painting. It told near enough the whole story, very succinctly.

Helen Owen’s piece, meanwhile, on the right, offered what I considered to be a very (perhaps the most) ‘artistic’ interpretation.

Helen Owen’s piece, meanwhile, on the right, offered what I considered to be a very (perhaps the most) ‘artistic’ interpretation. Not entirely abstract but strongly leaning that way.

Very effectively stylised, areas of light and colour interspersing with darker, more menacing imagery to indicate the many highs and lows the characters in the novel undergo, semi-subliminal gravestones in the background hinting at the fate of so many.

And through the middle of it all, a road leading not so much to redemption as to uncertainty, which I felt nicely underlined the conclusion to the novel, wherein the evil, while it is certainly evaded, is not necessarily defeated, which in its turn then poses the questions: when will it reappear, and what form will it take next time ... and will we be ready for it?

The winner

The winner – and I’m not kidding when I repeat that this was a photo-finish – was Helen Roberts’ version of NEVER SEEN AGAIN .

The first thing that struck me about this particular piece of work was the face of Jodie Martindale in its very centre, staring out at me with the most hauntingly beautiful pair of eyes. Those who’ve read the novel will recollect that Jodie was kidnapped six years before the narrative really commences, and though her boyfriend, who was also taken, was found zip-tied and shot through the back of the neck only a couple of days later, Jodie herself has never been heard from since.

Jodie is thus the central character in NEVER SEEN AGAIN even though she barely appears in it. She is the person whom our flawed heroes finally unite in order to try and find, putting everything on the line, including their lives. Her beauty and intellect, and her reputation as a good person, pervade the entire story, intensifying the tragedy of her unsolved abduction – and to suddenly see her looking out at me like that, literally locking gazes with me, was a near mesmerising moment.

The rest of the painting is also filled with meaningful symbols, so many that I suspect I’d need to dedicate a different blogpost to assessing them all, along with many other key moments and personalities from the book. Anyway, here I am below, presenting the winning artist, Helen Roberts, with her prize.

I don’t want to talk too much more now about this event for fear of getting self-indulgent, but I will add that a video telling the whole story of the ‘paint-off’ competition, which was filmed up here in my home town, Wigan, as well as down in Birmingham, is now in production and will be launched at a Birmingham venue in the New Year.

Because I obviously haven’t posted enough pictures of this major event in my life, here are one or two more. In addition, if you feel I haven’t written enough about it either, you can read a lot more HERE .

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE WOMAN IN CABIN 10

by Ruth Ware (2016)

THE WOMAN IN CABIN 10

by Ruth Ware (2016)

Outline

Laura ‘Lo’ Blacklock is an ambitious and talented travel journalist, who on the surface has it all. A glamorous job with uber-cool mag, Velocity, great talent, a hunky American boyfriend, Judah, who also happens to be a successful reporter (and who absolutely adores her), and now an opportunity to travel on the Aurora, one of the world’s most luxurious holiday yachts, which will shortly be making its maiden voyage to the Norwegian fjords to check out the Northern Lights.

But Lo, who has a more fragile personality than many might realise, was recently terrorised in her London flat when a masked burglar broke in and helped himself to her valuables while she was present. Though she was physically unhurt, the result is nightmares, insomnia, a series of terrifying flashbacks and an increasing reliance on alcohol and prescription pills to get her through each day. This stew of self-medication ends up clouding her judgement badly, which leads to a fall-out with Judah, who has turned down a massive job offer in New York in order to stay with her, a huge sacrifice that she is almost indifferent to.

When she finally arrives on the Aurora, which is owned by British business mogul, the effortlessly smooth Lord Richard Bullmer, she experiences a degree of lavishness she never knew existed, and finds herself in the company of a range of wealthy and eccentric socialites, none of whom, in Lo’s distressed and crotchety state, seem entirely ‘right’.

Among others, there is Cole Lederer, a handsome, vaguely predatory photographer; Alexander Belhome, a pompous, corpulent hedonist; Chloe Jenssen, a beautiful model, and her wealthy investor husband, Lars; and Archer Fenlon, a rugged, Yorkshire-born outdoorsman, who seems very out of place here. Lord Bullmer himself is the dominant character, though his life isn’t entirely perfect, as his wife, Anne, is also present, a sad, frail woman who is vastly wealthy in her own right but currently in the middle of a losing battle with cancer (not that Bullmer seems to be especially affected by this).

If nothing else, Lo is glad to see a couple of fellow journalists, though Tina West is a waspish rival whom she doesn’t trust, while Ben Howard, though a former lover of Lo’s, is a confident swaggerer even in this society, which galls her, and, because he once shared Lo’s bed, is now inclined to take liberties with her, which she also doesn’t like.

For all that she feels out of her depth, Lo is determined that her trip on the Aurora, and the write-up she will give it, will be her big break in travel-writing. But on the first night of the cruise, things take a turn for the totally surreal.

Lo, still emotionally exhausted and already on her way to being drunk, is preparing for her first real evening in the company of the rich and famous, and so pops next door, to Cabin 10, to borrow some mascara. A young woman she hasn’t seen before, who appears very flustered to have suddenly come face-to-face with one of her fellow travellers, provides the missing cosmetic and then slams the cabin door in Lo’s face.

Lo gets through the evening by continually dosing herself with alcohol, though she notices that the young woman from Cabin 10 doesn’t appear. Later, back in her own cabin, very drunk, Lo is just dozing off when she is disturbed by the sound of a scream next door, and then a loud splash, as if something hefty has been tossed overboard. Staggering out onto her veranda, Lo is appalled to see what looks like a body submerging between the dark, foam-covered waves. She also spots what looks like a smear of blood on the glass partition separating her from the veranda attached to Cabin 10.

Convinced the young woman she saw there has been murdered, and equating it with her own experience during the London burglary, Lo makes a big fuss, but when the yacht’s security chief, Johann Nilsson, takes charge, she is startled to learn that Cabin 10 is unoccupied. It was booked, but the expected guest was unable to attend, and no one has been in there since. They check the cabin out together, and it is stripped and bare. In addition, there is no trace of any blood.

The next day, Lo and Nilsson make a tour of the vessel, but nowhere does she see anyone who resembles the woman from Cabin 10. Instead, she is introduced one by one to the helpful and improbably good-looking Scandinavian crew, though none of them are able to assist her. Everyone who is supposed to be on board is present and correct; no one is missing.

If nothing else, Lo still possesses the mascara she borrowed from the woman, which, to her mind at least, is proof of what she thinks happened. But Nilsson is not impressed, arguing that the mascara could have belonged to anyone. When, later on, the mascara goes missing too, Lo demands an explanation, and Nilsson finally gets frustrated with her, pointing out that her combined diet of drugs and alcohol is hardly making her a reliable witness, and that her constant questioning of people is becoming a nuisance.

Still convinced that she met someone in Cabin 10, but also aware that she has skewed her own sense of reality in recent times (now suspecting that everyone on board is watching her and whispering), Lo wonders if there might be something in Nilsson’s assertion that she has basically made a huge and embarrassing faux pas. Helpless to do anything else, she tries to relax in the yacht’s spa, hoping to get it together, only to fall asleep and then wake up and see a message written on the steamy mirror: STOP DIGGING …

Review

The Woman in Cabin 10 first appeared in the wake of The Girl on the Train , and obvious analogies were drawn, the main heroine’s struggles with alcoholism fuddling her attempts to work out whether she is genuinely a witness to criminal activity or simply imagining it and bamboozling her efforts to call on the assistance of others.

The really big difference with The Woman in Cabin 10 , though, is that Ruth Ware takes her story out of the suburbs, where so much modern day psychological noir is located, and plonks it down in one of the most isolated spots you can imagine: a small cruise-liner, far out in the North Sea, where, once the internet has gone down, contact with the outside world is all but impossible.

This is a very neat idea, but Ware intensifies the tale all the more by moving it away from the normal ‘blue sea / blue sky’ cruise ship experience, plunging us into the far north, a realm of cloud, bitter rain and dark, cold seas. On the few occasions Blacklock is able to go ashore, she’s on the rugged Norwegian coast, where spume explodes from the rocks, and any footpath or road invariably leads steeply uphill in its attempts to navigate the dizzying slopes of the fjords.

So, once Lo Blacklock reaches a solid conclusion that she’s onto something – not just that she witnessed a murder but that she herself is now in peril – the sense of discomfort becomes overwhelming. Especially as she still has no way to identify the killer (or killers). Ruth Ware, like all good thriller writers, now works this scenario for everything she can. In scenes as tense as a hangman’s rope, Lo moves among her fellow passengers and the yacht’s highly efficient staff, watching every one of them carefully, and seeing (or imagining) all kinds of oddities and idiosyncrasies that might lead her to suspect them.

The tension mounts as the vessel encroaches on its first scheduled stop, Trondheim, where the journalist knows she’ll be able to get ashore and speak to the police, meaning that, if she’s going to become a victim herself, it will need to happen before then.

The extra layer of oppression that Ware adds through the device of Lo’s booze-fuelled anxieties only worsens her predicament, mainly because it means that other characters don’t believe her. On the other hand, we the readers know that she’s onto something. For all Lo’s acute paranoia and pernicious self-doubt, we shared the incident involving Cabin 10 with her. Despite her wibbly-wobbly recollections, we saw it happen for ourselves.

In that regard, the ‘unreliable narration’ technique didn’t entirely work for me.

On a not dissimilar subject, if there’s a weakness in The Woman in Cabin 10 , I think it’s rooted in the character of Lo Blacklock herself. She is both physically and mentally enfeebled by her bad experiences. Which is fair enough. But it’s turned her into someone rather unpleasant. While you might agree with her assessment that the Aurora is all about rich people enjoying a holiday at the expense of poor people, you can’t help cringing at her whiny snappiness. Yes, she’s had a hard time, but she’s supposed to be a professional journalist, someone whose grand plan is to travel the world, reporting on all kinds of troublesome situations, so you can’t help feeling that she could make a bit more of an effort to get back in the saddle.

Aside from that, I had one other complaint, and that lies with the rollcall of secondary characters, many of whom are little more than background figures throughout, potential suspects initially but so undeveloped as to gradually disappear from view as the story proceeds. This serves to reduce the mystery factor in The Woman in Cabin 10 until we reach the point where, when we finally uncover the culprit, it’s a bit of a ‘ho-hum’ moment.

But as someone who enjoyed this book and read it quickly, I’d argue that its mystery elements purposely end up playing second-fiddle to the slowly mounting air of fear and distrust, and above all, to the suspense. It’s relatively early in the story when we learn that Lo Blacklock isn’t losing her mind but has uncovered vicious criminality, and once that is established, the tension ratchets up unnervingly quickly.

Who is the guilty party here? Which of these pleasant and gregarious people is actually a scheming murderer? But much more pertinently, especially in the final third of the narrative, surely they’ve now decided that they can’t let Lo live? So, at which point will they strike? How will they do it?

I have to say that there’s no particular gut-thump at any stage in The Woman in Cabin 10 , no horrifying shock that completely knocks you off kilter, but all these minuscule criticisms aside, I found this a smart and satisfying thriller. Claustrophobic, twisty and very pacy in the second half (with a steadily mounting sense of jeopardy), and written in Ruth Ware’s usual spare and easily accessible style, I tore through it in a couple of days.

Just don’t take this book with you on an ocean cruise. Or, who knows … maybe to get the most out of it, you should.

And now, in my usual ill-advised fashion, I’ll attempt to cast this property in the hope some big noise in film or TV is looking to put it on the screen and comes calling for my advice. Unlikely, I know, but it’s all in fun.

Lo Blacklock – Millie Brady

Lord Richard Bullmer – Richard Armitage

Ben Howard – William Moseley

Tina West – Naomie Harris

Carrie – Thomasin McKenzie

Cole Lederer – Mark Strong

Johann Nilsson – Joel Kinnaman

Published on November 17, 2022 07:47

November 8, 2022

West Country ghouls ride out into world

Well … both Halloween and Bonfire Night have been and gone, and I haven’t posted anything about either of them. Yes, a whole month has passed since I last blogged. I can only apologise about that. In particular, I had a huge October blog lined up. I was going to talk about horror movies, picking five of my favourites from each decade between 1930 and 2020. Ninety years of celluloid horror. How much fun would that have been? Not that everyone else doesn’t seem to have had a similar idea.

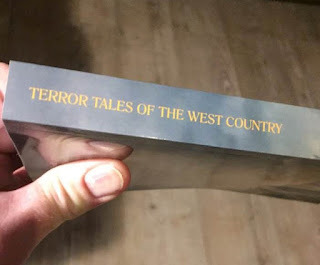

Well … both Halloween and Bonfire Night have been and gone, and I haven’t posted anything about either of them. Yes, a whole month has passed since I last blogged. I can only apologise about that. In particular, I had a huge October blog lined up. I was going to talk about horror movies, picking five of my favourites from each decade between 1930 and 2020. Ninety years of celluloid horror. How much fun would that have been? Not that everyone else doesn’t seem to have had a similar idea.Unfortunately though, in my case the time just ran out. I’ve just been too busy bringing TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY along the final furlong into publication, which has now happened, I’m delighted to say, and making vital edits to my first medieval epic for Canelo Books (the title has now been settled on, but I can’t reveal that until we reveal the cover also, which hopefully will be soon).

It is still the season of mist and horror though, so if nothing else, at least today’s book review can match the mood. It’s Clay McLeod Chapman’s compelling account of Satanic horror breaking out in the heart of suburban America, WHISPER DOWN THE LANE.

If you’re only here for the Chapman review, no problem. You’ll find it, as usual, in the Thrillers, Chillers section at the lower end of today’s column.

Before that though, a quick reminder that we’re finally …

Out in the world

Out in the worldYes, TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY is finally out there, it’s an actual thing, it is moving around in the hands of readers and reviewers alike (for proof of the latter, check out the unfolding response on the excellent VAULT OF EVIL , truly one of the best horror anthology review sites in the world). It’s also, as you can see from this pic, a solid chunk of a volume, easily the fattest of the series to date (primarily because it contains several truly wonderful but longer-than-usual stories).

Hopefully, people will enjoy this one as much as they’ve enjoyed the others.

TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY is the 14th volume in the series thus far. Those who’ve followed them from the beginning will know that I first began editing these books in 2011, when they were published by Gray Friar Press.

However, five years ago, with

TERROR TALES OF CORNWALL

, the operation was taken over by

TELOS PUBLISHING

.

However, five years ago, with

TERROR TALES OF CORNWALL

, the operation was taken over by

TELOS PUBLISHING

. The original intention behind the series was to make a whistle-stop tour of the UK, each anthology focussed on a different geographic area, the stories all linked to that region’s unique folklore, mythology and history.

And to date, the writers have done me very proud indeed, with numerous stories chosen for Year’s Best type editions and so forth. The books have also boasted a succession of truly wonderful covers, provided at first by Steve Upham, but later on, for the nine most recent editions, by Neil Williams, all of which have caught the eye far and wide.

The idea first came to me, believe it or not, back in the 1970s, when I was on holiday in the Lake District, where I acquired several volumes of the Fontana series, Tales of Terror, most of which were edited by R. Chetwynd-Hayes, and even though I was only a teenager at the time, I was so impressed that I just knew I had to do something similar when I was older.

Anyway, to cut a long story short, TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY is now out in the world. So … come on, you guys. Go and get it.

When crime meets art

I’ve also been busy this last couple of weeks with a project I can’t talk about too much yet, though I hope to be very voluble about it indeed later this month.

Anyone who follows me online generally will know that NEVER SEEN AGAIN , my most recent crime thriller, has been chosen as the subject for an arts competition in Birmingham, the painters participating each charged with producing their own interpretation of the novel. As I say, I can’t be too vociferous about this yet, but you can read a little bit more about it HERE and HERE if you want to.

Suffice to say that a film crew came up to my home town of Wigan at the end of October, to interview me about it, to talk about the inspiration behind NEVER SEEN AGAIN , and behind my writing in general, and of course, the fusion of two very different art forms, painting and writing as part of a process, which ultimately must see 130,000 words of text condensed down into a single canvas (some challenge, when you consider it).

Anyway, above is a shot of me being interviewed on the matter by West Midlands media personality, the lovely Lorraine Olley. It was a great day when we did this. I can’t wait to tell you folks all about it. Stay tuned.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

WHISPER DOWN THE LANE

by Clay McLeod Chapman (2022)

WHISPER DOWN THE LANE

by Clay McLeod Chapman (2022)

Outline

We enter this dark drama, which of course, is inspired by true-life incidents, in two different time streams. First of all, we join contemporary art teacher, Richard Bellamy, at a cute suburban school in Danvers, Massachusetts, where not only does he command the affection of his pre-teen pupils and the respect of most of the other staff, he’s recently entered into a relationship with another teacher, the slightly punky Tamara, and is now in the process of winning the trust of her son from a previous marriage, Elijah.

However it’s not all peachy. We open with Richard coming into work on his birthday, and finding one of the school’s pets, a rabbit called Professor Howdy, dead on the sports field, having been mutilated in gruesome, near-ritual fashion. Not only that, a birthday card has been inserted into its stomach cavity, which, when Richard opens it, says simply ‘Circle Time’, which he assumes refers to the team-building exercise the school’s staff usually indulge in each time before commencing work, though the incident remains horrible and baffling.

Richard is a relatively new teacher in Danvers, but apart from the endless scrutiny he inexplicably receives from beady-eyed principal, Mrs Condrey, he is very happy. The school is hardly a challenge; Danvers, which was once solid rustbelt, has been ‘Disneyfied’ in keeping with the modern politically-correct age. He thus tries to focus on his work and his relationship with Tamara and Elijah, but the rabbit incident won’t leave his mind, especially as there has recently been an uptick in the amount of graffiti appearing on the school’s toilet walls, including Satanic images like ‘666’.

The next moment of unpleasantness is more mundane. Elijah gets in trouble for hitting another kid, supposedly in defence of a pretty but withdrawn pupil called Sandy. It’s not a big deal, but while Richard is sorting it out, he receives a curious phone-call, someone breathing at the other end of the line but refusing to speak …

Switching back to 1983, we meet a nervous young child called Sean Crenshaw, who, in company with his highly-stressed mother, is fleeing their family home and starting a completely different life in a town they’ve never been to before. Greenfield, Virginia.

We quickly gauge that Sean’s mother is seeking to escape an awful relationship back home, and determined to make a clean break. At first it looks as though she’s succeeded, working more than one job to get herself and her son afloat again, Sean enrolled at the local school, Greenfield Academy, and when school is out, being minded by kindly neighbours. One of these in particular, Miss Betty, is especially helpful. While he’s in her house one day, Sean sees a faded photograph of a little boy who he’s never met in real life. Miss Betty tells Sean that this is her son who died, but because of the poor quality image, Sean comes to think of him as the ‘Grey Boy’ and finds the picture disturbing.

Even aside from this, Sean’s life in Greenfield is not all it might be. Once the word gets around school that he and his mother are welfare cases, other kids start to mock and bully him. When a particularly mean specimen called Tommy Dennings leaves bruises on his body, Sean’s mum, who is under pressure herself from the authorities regarding her own parenting skills (presumably owing to events in their former life), demands an explanation, but Sean is too frightened to tell her the truth. At the same time, he speaks a lot about his favourite teacher, Mr Woodhouse, who is young and energetic and disguises many of his lessons as games, and his mother begins to wonder exactly what their relationship is. Sean is equally stressed because though he insists that everything is all right and that he really likes Mr Woodhouse, he suspects that he’s not giving his mother the answer she wants.

Then the word gets out that Mr Woodhouse has been playing a game with the kids called Whisper Down the Lane, a kind of Middle-American version of Chinese whispers. In itself it’s harmless, but then, one of the messages he has his pupils pass from one to the next refers to Lucky Charms, a range of marshmallows currently disapproved of by a local group of watchful mothers, who are concerned about the supposed pagan symbology contained within the branding.

Rumours start spreading that something may be wrong at Greenfield Academy. Some children have been having bizarre nightmares (though they’ve never admitted that these occurred after they’d watched the Michael Jackson video, Thriller ), while others talk a lot about the many games Mr Woodhouse likes to play with them. Under heavy pressure from his mum, Sean finally cracks and tells a whopping lie, namely that their teacher likes to play a game called Horsey, in which they are all naked …

Back in the present day, Richard Bellamy’s odd experiences continue. During one lesson, he has the children make pinatas out of papier-mâché. Most create images of animals, but at the end of the lesson, he finds one that seems to represent a young child. It’s also been painted grey. No one in class will admit to having made it, and Richard then notices that someone has signed it ‘Sean’. Of course, there is no one in his class with that name.

Another name now occurs to him, seemingly from nowhere. ‘Mr Yucky’.

Later on, he is cheered up when Tamara offers to let him use her old garage as an art studio. Richard gave up painting some time ago, but now starts over, immediately sketching an image of a beautiful woman with a grey-toned boy in the background. He thinks the picture could represent his mother, who was very pretty, but it might also depict a beautiful woman called Miss Kinderman, a psychiatrist who once introduced him to a doll that was similar in looks to a Cabbage Patch Kid. Its name was Mr Yucky, she told him, and it was called that because he could tell all his yucky stuff to it.

Increasingly wondering what is happening and why these strange half-memories are bombarding him, Richard then loses Elijah at the Fall Harvest Fair. It didn’t help that he was fleetingly mesmerised by the sight of Mr Stitch, the grey-faced scarecrow at the heart of the corn maze. Thankfully, Elijah is located safe and well by Sandy’s mother, Jenna Levin, a handsome but rather humourless woman, who doesn’t seem to like Richard by instinct. Inevitably, Tamara, who gets extremely angry very easily, is unimpressed.

As she drives them home fast, ranting and raving, Richard is reminded of his own mother, when he was a young boy, driving them at dangerous speed away from their old life to a town called Greenfield. When they get home, he finds the cat, Weegee, hanged and gutted. Not wishing to fuel the atmosphere with further anxiety, Richard conceals the carcass in his studio. Then he notices an item of mail that arrived earlier that day. It is addressed to ‘Sean’ and when he opens it, contains a single newspaper clipping. It is at least two decades old, and discusses the fate of a former teacher called Thomas Woodhouse, who, despite having recently been acquitted on appeal of ritually abusing his pre-teen pupils, has still served extensive prison time, and has now committed suicide …

Back in the early ’80s it’s all hands to the pump as the school kids, taking their lead from Sean, and at the coercive behest of their parents, tell lies about Mr Woodhouse. Miss Kinderman is a key instigator, using various eccentric methods to get Sean to open up even more, dressing as a scarecrow on one occasion, but mostly utilising the hideous grey doll, Mr Yucky.

The stories have grown with the telling. Mr Woodhouse wasn’t acting alone. Other members of the faculty were involved too, and sometimes the children were taken out of school to attend Black Masses in derelict graveyards. All kinds of vileness was indulged in. Inevitably, when Mr Woodhouse goes on trial, Sean is the star witness. It hurts him deeply that he’s continuing to tell bare-faced lies. He knows it’s very wrong, but this is what Miss Kinderman, and more importantly, his mother seems to require from him.

Afterwards of course, Sean and his mother become the centre of all conversation. People are now sympathetic to them. At last, they seem to have friends. Though not everyone commiserates. When a brick is thrown through Sean’s window, he senses that it’s an unhealthy kind of attention people are paying to them. When the part of the school where Mr Woodhouse used to teach is burned down, he detects the mob mentality lurking beneath the surface of the townsfolk.

Very much against his will, but still playing along, Sean is invited to appear with his mother and Miss Kinderman on a popular television talk-show. During the course of a sensationalist TV circus in which no lurid detail is left unaired, Sean is semi-hypnotised by the sight of the Grey Boy, who sits in the audience and waves at him …

Back in the present, we now know for certain that Richard Bellamy and Sean Crenshaw are one and the same. Richard thought he’d put Sean – the Grey Boy, the Cabbage Patch Kid – away, tucked him into the back of his brain, and had forgotten him along with that whole terrible period of his early life.

But someone else – God only knows who? – clearly hasn’t forgotten, and it seems they are determined to raise the Satanist terror all over again, this time in Danvers, and to put another popular teacher, Richard Bellamy, at the centre of it …

Review

The infamous Satanic Panic originated in 1980 with the now discredited memoir, Michelle Remembers , in which a Canadian psychiatrist, Lawrence Pazder, claimed that, while treating a patient called Michelle Smith for depression, he unlocked repressed memories of horrific abuse suffered during childhood in the midst of brutal Satanic ceremonies. The book became a huge seller, mainly through the shocking possibility that ordinary, everyday children might be suffering the most depraved forms of ritual abuse, not just at the hands of perverse and twisted parents, but while in the safekeeping of so-called care-workers. This appalling fear was exacerbated three years later by the McMartin Pre-School trial in Manhattan Beach, Los Angeles, wherein allegations were made (again, most of which were later refuted) that pre-teen children had been taken to Black Masses by kindergarten staff, where they had suffered torture, rape and been forced to watch animal mutilation and human sacrifice.

Rumours wildfired that such incidents were not isolated and were in fact the work of an organised, international cabal of devil-worshippers, whose very raison d’être was to do the most evil things imaginable, including the murder and molestation of infants. This ‘moral panic’ as it became known, eventually swept the US and much of the rest of the western world, engulfing entire towns, and creating a latter-day witch hunt of terrifying size and scope, which caused the break-up of families and communities, and the jailing of numerous individuals, many of whom, though they were later exonerated, would feel like outcasts for the rest of their lives.

It’s not essential that you know this in order to fully appreciate Whisper Down the Lane , but it can only help if you do. Because what Clay McLeod Chapman has done with this book is create an enthralling mystery-thriller set against that simmering background of fear and paranoia.

It’s a fictionalised version of the real events, of course, but it’s no less powerful for that.