Paul Finch's Blog, page 3

August 3, 2023

Order 'Terror Tales of the Mediterranean'

Today, I’m delighted to present you with details of this year’s volume in my folk horror-themed anthology series, TERROR TALES. In 2023, as you can see, it will be TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN, which, as of today, is available for pre-order right HERE.

Today, I’m delighted to present you with details of this year’s volume in my folk horror-themed anthology series, TERROR TALES. In 2023, as you can see, it will be TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN, which, as of today, is available for pre-order right HERE. This is always one of my favourite parts of the anthology-creation process, hitting you with Neil Williams’ amazing artwork and listing the stories, both fiction and non-fiction, that you’ll find inside, and of course, teasing you with a few brief snippets from some of the incredible tales that will be gracing the new book’s pages.

I’ve made no secret that this year, for the first time ever, we’d be venturing into countries outside the United Kingdom, a potential sign of things to come. But more about that later, along with lots more concerning the contents of this year’s volume.

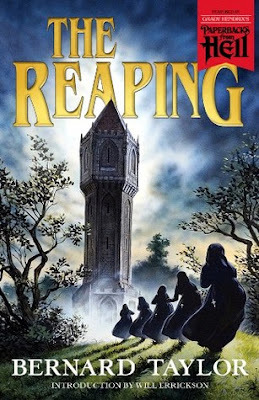

When it comes to this week’s book review, alas, I’m unable to maintain synchronicity, as I haven’t got a Mediterranean-themed novel to hit you with. But, seeing that the TERROR TALES books primarily contain new horror stories of British origin, it’s probably (vaguely) thematic to pull in a British author who was very famous in his day for writing short, sharp shockers: Bernard Taylor. As such, I’ll also be offering a detailed review of Taylor’s recently republished 1980 horror novel, THE REAPING.

As usual, if you’re only here for the Taylor review, feel free to scurry on down to the bottom of his column, where you’ll find it in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

And now, today’s main event …

I reiterate that TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN can now be preordered HERE . It will only be published in the autumn, but if you want to reserve your copy for the very first day of its actual existence, why waste time?

If that doesn’t persuade you, here, for your delectation, is the back-cover blurb, followed by the full Table of Contents:

TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN

The Mediterranean. Sun-bleached ruins, azure seas, foaming wine. But history’s cruellest tyrants reigned here, delighting in blood and torture. Myths tell of snake-haired harridans and one-eyed giants, of humans cooked on spits, of curses, scourges, and devious deities who played with men’s souls like pawns in chess …

The poison apples of Aegle

The human sacrifice on Crete

The beautiful predator of Palermo

The damned souls on Poveglia

The evil artefact at Koyuluk

The blood-drinking baron of Emporda

The demon attack in Vatican City

Includes terrifying tales by Jasper Bark, Simon Clark, Steve Duffy, Paul Finch, Sean Hogan, Carly Holmes, David J Howe, Maxim Jakubowski, Gary McMahon, Mark Morris, Reggie Oliver, Peter Shilston, Don Tumasonis and Aliya Whiteley.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Catacomb by Peter Shilston

Duo of Darkness

On Our Way to the Shore by Maxim Jakubowski

Belmez

Meet in the Middle by Aliya Whiteley

Island of the Damned

The Lovers by Steve Duffy

When Madmen Ruled the Earth

The Wretched Thicket of Thorn by Don Tumasonis

The Blue Room

This Haunted Heaven by Reggie Oliver

Born of Blood and Mystery

The Quiet Woman by Sean Hogan

Holy Terrors

The Teeth of the Hesperides by Jasper Bark

Cyclops

Reign of Hell by Paul Finch

In Human Guise

Mistral by Mark Morris

Ghosts of Malta

Mammone by Carly Holmes

Extinctor Draconis

Vromolimni by David J Howe

The Other Devils

Gerassimos Flamotas: A Day in the Life by Simon Clark

Lord of the Undead

Should Not Be by Gary McMahon

And while we’re at it, why don’t I try and tempt you with some juicy snippets:

There was a girl-child whose clothing looked at least two hundred years old, but who from her skin and hair might just have fallen asleep; but beyond her a man in priestly robes had lost his nose and his cheeks, and his eyes had decayed to blank milky globules; and further on the soldier in the chased steel breastplate, who was perhaps a mercenary from the Renaissance period, had lost his flesh entirely, and now grinned mindlessly with a naked skull …

Peter Shilston – The Catacomb

The shirt ripped and the boy’s knees gave out, he crumpled, and the man still did not stop. He hunched over, arranged the boy, stretching out his arms and legs, then reached into the boy’s stomach. His hand was in the boy’s stomach, material was pulled out, something wet, it separated into strands. The man put the strands into his mouth and chewed, he put more into his mouth, he kept chewing …

Aliya Whiteley – Meet in the Middle

The water bulged. Something vast was coming up from deep below, and the sound was that of a wellington boot being slowly lifted from a pool of thick, gelatinous mud. The lake sloshed around the edges as the thing heaved itself out, and when it fell back, the water level dropped by at least a foot. Sally took a step back, her eyes not quite comprehending what was in front of her. It was dark and seemed to suck the light into it. The redness from the lowering sun cast shadows over the creature, and it glistened as the water fell from it in sheets …

David J Howe – Vromolimni

Why the Mediterranean?

I’ve already been asked that a couple of times, even though I haven’t talked a great deal about this anthology yet. It’s a very good question. After all, there are several locations in the British Isles that we haven’t yet visited, the South Coast being one, the Midlands, the Northeast, etc. Why are we suddenly venturing so much farther afield?

Well, I’ve never made any pretence that

TERROR TALES

was first inspired by the Mary Danby-helmed

Tales of Terror

series, most frequently edited by R. Chetwynd-Hayes, which came out from Fontana Books in the 1970s. They followed a similar format to ours, but tended to cover broader regions than we do. However, they didn’t stop at the shores of Great Britain.

Tales of Terror from Outer Space

was a very popular title of theirs, along with

European Tales of Terror

and

Oriental Tales of Terror

.

Well, I’ve never made any pretence that

TERROR TALES

was first inspired by the Mary Danby-helmed

Tales of Terror

series, most frequently edited by R. Chetwynd-Hayes, which came out from Fontana Books in the 1970s. They followed a similar format to ours, but tended to cover broader regions than we do. However, they didn’t stop at the shores of Great Britain.

Tales of Terror from Outer Space

was a very popular title of theirs, along with

European Tales of Terror

and

Oriental Tales of Terror

. Now, I’m not following that series religiously. I’m not here to ape everything that Mary and Ron did, great ambassadors for British horror though they were, but if the TERROR TALES series is to have real longevity, it can’t just pour out spooky tales gleaned from a single country.

We’ve already branched out a little.

TERROR TALES OF THE SEASIDE

(2013), for example. Okay, it solely featured folklore and fiction from the British coastline, but it was all corners of the country, from Scotland to Kent, while

TERROR TALES OF THE OCEAN

(2015), which won considerable praise, ranged widely across the Seven Seas.

We’ve already branched out a little.

TERROR TALES OF THE SEASIDE

(2013), for example. Okay, it solely featured folklore and fiction from the British coastline, but it was all corners of the country, from Scotland to Kent, while

TERROR TALES OF THE OCEAN

(2015), which won considerable praise, ranged widely across the Seven Seas. But the truth is that, though I’m very keen to complete our own TERROR TALES tour of the United Kingdom, and will be doing exactly that, I’m now looking more and more overseas, taking regular deep dives into the mythic and folkloric culture of lands far away.

Of course, we can’t do every country on Earth. There are various reasons for this, not least that I only have time to edit one of these books per year, and so that would be an impossible target. But we can do regions, and TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN will be the first.

What may follow from that in the future is anyone’s guess, though I’m pretty sure I’ve stated in an earlier blogpost that some corners of the world, while they are rich in tales of mystery and magic, and are planted thick with homegrown authors, would be difficult territory for me to venture into. TERROR TALES OF THE CARIBBEAN, for example, would be a perfect fit for this series. What greater source for this kind of material could there be than the land of hoodoo. But the Caribbean has a wealthy literary tradition of its own and boasts numberless talented writers, many of whom are unknown to me. The same would apply, sadly to Central and South America, to those various regions of the United States, to the Far East, even to Ireland. All those titles would be well worth including in this series, but our readers would be much better served by editors homegrown in those lands, who wouldn’t miss a trick in pulling the absolute best scare fare they could from their native soil.

This applies less to regions like the MEDITERRANEAN , which so many of us are already very familiar with. So, while TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN is an exciting new venture, and there are others in a similar vein that we can do in the future, it’s not possible yet to put together a full list of prospects.

But never fear; there are lots – and I mean lots – of other subjects we can tackle: TEROR TALES OF MONSTERS … of the SUPERNATURAL … the OCCULT … the mind truly boggles.

But never fear; there are lots – and I mean lots – of other subjects we can tackle: TEROR TALES OF MONSTERS … of the SUPERNATURAL … the OCCULT … the mind truly boggles. Just keep watching this space. Who knows what we’ll hit you with next.

But for the meantime, one final reminder that TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN , which on its own will throw you in the path of numerous horrific entities, both real and imaginary, is out in the autumn, and ready to pre-order. Get it HERE .

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE REAPING

by Bernard Taylor (1980)

THE REAPING

by Bernard Taylor (1980)

Outline

Family man, shopkeeper and wannabe artist, Tom Rigby, is your archetypal suburbanite. He’s suffered grievous losses in the past, his wife and several children having died in a terrible accident, but he is positive about life, he works hard and does what he can, mainly with the assistance of his caring older sister, Em, to look after his remaining brood, in particular his youngest son, Simion, with whom he is very close.

While, by his own admission, he is not exactly handsome, Rigby has a certain ‘everyman’ charm, which has attracted a new girlfriend, Ilona. She is younger than he is by several years and has a well-paid job as a makeup artist in the film industry. The downside of this is that Ilona is frequently away on location, meaning that she and her beau spend long periods apart, able only to communicate by letter. To cope with this, Rigby throws himself into his painting, which is not of such quality that it’s likely to make him a fortune, though at least it keeps him happy.

Then something happens that has the potential to change everything. After a local art exhibition in which his recent canvasses play a prominent role, Rigby is approached by a Mrs Weldon, a pleasant, efficient woman, who explains that she is housekeeper for a Miss Stewart, an elderly spinster who occupies a large country house down in Somerset, and who would like to hire an artist to paint a portrait of her niece, Catherine. Significant money is offered, but at first Rigby resists because he is planning to go on holiday with Ilona. Then, at the last minute, when Ilona has to cancel, work again getting in the way of their relationship, Rigby accepts the commission.

When he arrives at Woolvercombe House, where he expects to be spending the next few weeks, it isn’t an especially shabby place, but it isn’t modern, and there is an air of remoteness. Only a handful of staff keep things running: Miss Weldon herself, who retains an aura of firm control, a burly Cockney handyman, Hathaway, and a German-accented manservant and chauffeur called Karl, whose manner Rigby finds deferential but also strangely mocking. There is also Dr Macintosh, a Scottish-born medical practitioner, whose regular presence at the house is never really explained.

When he is introduced to Miss Stewart herself, who otherwise he is told he will rarely meet, she is extremely aged, a hunched, veiled and odorous figure, who occupies a shadow-filled garret in the upper echelons of the house. While Rigby doesn’t take an instant dislike to her, he doesn’t find her a warm presence. She is particularly dismissive of the job she has hired him to do, and speaks disparagingly of her niece, leaving him mystified about why he is being paid so much money.

More mysteries follow. When Rigby spies women in monastic robes and cowls walking in the manor house gardens, he is advised that they are novice nuns, who, by some agreement made in the distant past, are lodged at Woolvercombe in the days prior to their travelling out to the missions, though he likely won’t meet them. They never, for example, come into the main part of the building, not even to eat, as they have their own quarters and refectory, and are here basically to spend their time in contemplation. So, if the guest would oblige everyone by treating the nuns’ small corner of the property as private, all will be well.

Rigby has no intention of getting to know the nuns. As far as he’s concerned, he is here to do a job, one that he hopes will only last a couple of weeks, and when it’s done, he’ll take the money and cheerfully head back to Ilona. But Mrs Weldon, for one, appears surprised that he expects his time here to be short, and encourages him to take as long as he needs. Rigby still intends to get this over and done with, but then he meets Catherine, the niece, an ethereal beauty in her late twenties, who is quietly spoken and makes for enchanting company.

She sits for Rigby often, though not as often as he’d like. Several times, things happen – either she is unwell or has had a minor accident – to prevent her attending his studio, which threatens to extend his stay. At the same time, the manor’s other curiosities pile up.

One night Rigby hears female screaming somewhere on the property, which Mrs Weldon dismisses as unimportant. On another occasion, while walking in the grounds, he accidentally comes close to several of the young nuns and is astonished to hear most irreverent language. He also detects, in a very overgrown section of the estate, a mysterious stone tower, which stands to considerable height. Whether it’s a folly, or something of functional significance he can’t say, though it’s an extravagant item. On yet another occasion, probably more disturbingly than anything he has dealt with up to now, he must rebuff an unexpected homosexual advance from Karl.

However, things take a turn for the really strange, when, later that same night, he hears Catherine out on the darkened landing being menaced by Hathaway. On offering her sanctuary in his room, he is shocked to learn that the apelike handyman has been a continual threat to her all the time she’s been here. When he advises her to complain either to her aunt or Mrs Weldon, she explains that Hathaway has been employed at Woolvercombe a long time and so nothing will happen. In fact, she regards Rigby’s room as the only possible place of refuge, and as such, the inevitable happens. She falls into his arms and they become lovers.

Despite this pleasant interlude, Rigby still wants to leave Woolvercombe as soon as possible to resume his own life (suffering no inconvenient guilt about having several times bedded the innocent Catherine!), but his departure is repeatedly hampered.

First of all, there are the endless delays with the painting. Then, when it is almost complete, his car breaks down for no obvious reason, Hathaway explaining that he’ll need to send away for a new part. After that, as if the breakdown isn’t enough, Karl loses the car keys.

Rigby is furious, especially as there is so little he can do. Increasingly, it feels as though he isn’t going to be allowed to leave Woolvercombe House …

Review

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, Bernard Taylor earned himself a reputation as one of the quiet men of pulp fiction, a professional author of high talent who could turn his hand to almost anything – and indeed he did, his output ranging from horror to murder mystery to romance.

These days, it is probably his horror range that is best remembered. Even there though, Taylor was something of an enigma, specialising in creating contemporary tales that proceeded at their own pace, were subtle rather than gory, but were so intriguing that they’d draw you in anyway, often only hitting you with the horror element late in the day (and usually, they were all the more effective for that).

A master of the slow-burn then, Taylor became a household name among the horror aficionados of his era, though it’s probably true to say that, in terms of sales, he never really rose to the topmost rank. And if he ever did, he didn’t stay there for long, inevitably succumbing, as did so many others, to the downturn of interest in horror from mass-market publishers in the 1990s.

If for no other reason than this, it’s great to see this fine author being given a new lease of life by Valancourt Books who, yet again, are here unearthing for us another half-forgotten gem.

For all this, The Reaping is very much a book of its time. We are firmly in occult-related territory, the eerie presence of nuns, an unexplained building deep in overgrown woodland, the matriarchal nature of the Woolvercombe estate, and explicit sex, of which there is quite a bit, all hinting at devilry of the old school.

Does it all work?

Well, it’s an involving mystery, for sure. As per the author’s normal style, it doesn’t shower us with blood at every turn, or hit us with jump-scares and other fleeting terrors, but the more that is revealed about the increasingly macabre Woolvercombe House, the more we invest in it.

As we approach the grand finale, we find ourselves deeply engrossed in the story and very eager to know what kind of ritual nastiness lies at the heart of it. And you can’t ask for much more than that with a thriller.

If there’s any weakness with The Reaping , I think it lies with the main character, Tom Rigby. Yes, he’s an ordinary bloke, who has almost wandered into this tale of terror off the street, but there’s a degree of self-absorbtion that makes him a little unattractive, not to mention a tad unbelievable. A case in point is the moment when he queries the sounds of female distress that he’s heard late at night: evidently something unpleasant is happening, and yet he is very easily fobbed off. In addition, he becomes trapped at Woolvercombe House because he is told that his car has broken down … and because he doesn’t investigate it himself or attempt any repairs off his own bat.

These are minor quibbles, of course, but later on it gets a little more serious. When Rigby leaves the property having completed the painting, he is not impeded by anything as bothersome as feelings for Catherine, the vulnerable young woman he has been sleeping with, which feels like a glaring flaw in his character in 21st century eyes. More serious yet, potentially very serious actually, is his failure to contact the police when, quite late in the tale, it is reported that a girl he recognises as having been one of the nuns on the estate – a person he found very distressed at one point – has been discovered dead.

In fact, Rigby’s unwillingness to contact the police at any stage in this story did become quite irksome for me, because he isn’t at Woolvercombe long before he uncovers evidence of quite significant law-breaking. Again though, I suspect this owes more to the period in which the book was written rather than any kind of flaw in the narrative. The 1970s was not a decade in which personal responsibility was encouraged.

All that aside though, this is a neatly packaged little horror novel, with a very different (albeit in some ways, quite Gothic and traditional) concept at its heart, which, perhaps if the mechanics of it aren’t as fully explained as I would like, still leads us to a grotesque, visceral and very unexpected denouement. It also contains one slam-bang twist in the tail, which I for one never saw coming and which is almost worth the admission price on its own.

Check out The Reaping if you can. It’s a great example of the criminally underrated Bernard Taylor working at the peak of his powers, uninterested in the ‘one death every three or four pages’ thing that seems to be a requirement of much modern horror, hitting us instead with an effective slow-burn mystery-thriller that rises to a spectacularly chilling climax.

And now, as always, I shall endeavour to cast this tale in eager (maybe rather hopeful) anticipation of its adaptation for the screen. They wouldn’t come and ask me, obviously, but we can still have a bit of fun with it, can’t we:

Tom Rigby – Matthew Macfadyen

Catherine – Thomasin McKenzie

Ilona – Gemma Arterton

Mrs Weldon – Sophie Okonedo

Hathaway – Paul Anderson

Karl – Reece Shearsmith Dr Macintosh – Ken Stott

Published on August 03, 2023 04:05

July 17, 2023

Sun, sea, sex ... and horrors that defy myth

A bit of a taster blogpost today. A few thoughts in advance of any real announcements concerning TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN, which hopefully will be published by TELOS in the autumn. From my point of view, the book is almost now complete, so in this installment I thought I’d throw out some crumbs to whet your appetites.

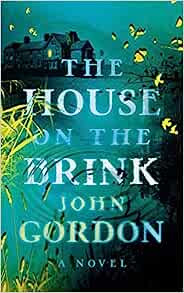

The TERROR TALES books are for the most part folk horror anthologies, so I thought it would also be appropriate today if I offered a detailed review of a short novel that is often considered to be one of the quintessential forays into folk horror from that first wave of interest in the subgenre at the end of the 1960s: John Gordon’s THE HOUSE ON THE BRINK.

If you’re only here for the John Gordon review, that’s absolutely fine. Scroll down to the lower end of today’s blogpost and you’ll find it, as usual, in the Thrillers, Chillers section. Do it straight away. I won’t mind. On the other hand, you might first be interested in, especially as so many of you will likely be going here in the next few weeks …

Terrors of

the Med

Terrors of

the Med

To quickly recap on the TERROR TALES anthology series, it’s mainly focussed to date on the British Isles. So, for example, we’ve had TERROR TALES OF THE COTSWOLDS , the WEST COUNTRY , the SCOTTISH LOWLANDS , CORNWALL , and so forth. There are 14 volumes in total to date, each one containing original horror fiction relevant to the geographic region, interspersed with snippets of real-life terror, folklore, mythology, unexplained mysteries and the like.

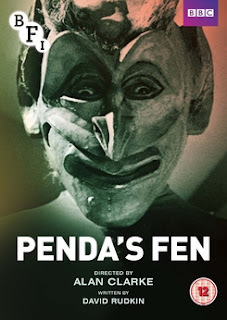

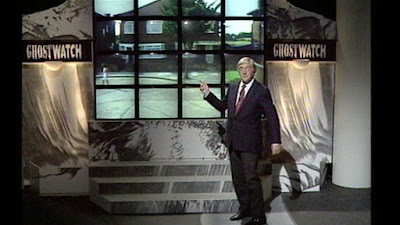

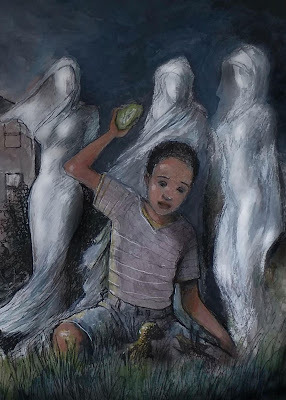

With TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN (check out the various pics scattered throughout this post to give clues about what’s coming - see how many you can identify), I’m obviously no longer just focussing on my British homeland, but starting to look a little farther afield. Hopefully readers will enjoy this one just as much as those that have gone before.

With TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN (check out the various pics scattered throughout this post to give clues about what’s coming - see how many you can identify), I’m obviously no longer just focussing on my British homeland, but starting to look a little farther afield. Hopefully readers will enjoy this one just as much as those that have gone before. I should hasten to point out that, even though for this 15th volume in the series I’ll be throwing my net over most of the Mediterranean Sea and its adjoining lands, I’ll purposely be ignoring the culturally very different region we call the ‘Middle East’ – Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Libya, Egypt and so forth – but that’s only because they will hopefully be the subject of a book planned for later in the series called ‘Terror Tales of the Middle East’.

Even then, the Mediterranean will easily be the largest specific geographic region that we have covered in this series to date, comprising much of the south shore of Europe and the north shore of Africa. But it’s a region that is familiar to the majority of us, boasting a benign climate characterised by low rainfall, hot, dry summers and mild winters. As such, its lovely landscapes and flora are instantly recognisable: rocky hills covered in scrub and cacti, arid plains, rich pine and cedar forests, cypress trees, olive groves. ‘The Med’, as we call it, has become the go-to place for the traditional summer holiday, but you won’t need me to tell you there is so much more to this fabled realm than sun, sea and sex.

Even then, the Mediterranean will easily be the largest specific geographic region that we have covered in this series to date, comprising much of the south shore of Europe and the north shore of Africa. But it’s a region that is familiar to the majority of us, boasting a benign climate characterised by low rainfall, hot, dry summers and mild winters. As such, its lovely landscapes and flora are instantly recognisable: rocky hills covered in scrub and cacti, arid plains, rich pine and cedar forests, cypress trees, olive groves. ‘The Med’, as we call it, has become the go-to place for the traditional summer holiday, but you won’t need me to tell you there is so much more to this fabled realm than sun, sea and sex. Its esoteric history is beyond compare with almost anywhere else.

It is commonly regarded as the Cradle of Western Civilisation. David Attenborough called it the ‘First Eden.’ Colossal empires have risen and fallen in this place. Epic wars have been waged. The most ancient cultures flourished here, leading to astonishing advances in human thought, language and artistry. Inevitably though, there is a darker side too.

It is commonly regarded as the Cradle of Western Civilisation. David Attenborough called it the ‘First Eden.’ Colossal empires have risen and fallen in this place. Epic wars have been waged. The most ancient cultures flourished here, leading to astonishing advances in human thought, language and artistry. Inevitably though, there is a darker side too.In the ancient Mediterranean past, fact is much interwoven with fiction, truth with mythology, a confusion of beliefs and certainties that has spawned some of mankind’s most terrifying tales, bequeathing us generations of monsters so unimaginably foul that it took the mightiest heroes to conquer them: everything from Talos to the Minotaur, from the sea-dragon, Cetus, to multi-limbed Geryon, one-eyed Polyphemus and Typhon, surely the most ferocious creature that ever stalked the Earth. The gods themselves were rarely better, unleashing curses and scourges on peoples they deemed to have failed them, sending earthquakes and typhoons to destroy entire cities.

Even lesser deities like nymphs and satyrs were maleficent, playing callous games with humanity, delighting in trickery and deceit, putting their own pleasure (and their lust) first.

There’ve been dark times in real history too: nations enslaved, vast libraries torched, innocents thrown to lions, free-thinkers burned at the stake. Both politics and religion have led to astonishing acts of cruelty in the supposed name of progress. It is little wonder that so many of the Mediterranean’s grand but crumbling ruins echo to the savagery of the past and are now the haunt of tragic ghosts and spirits relentlessly re-enduring their torments.

There’ve been dark times in real history too: nations enslaved, vast libraries torched, innocents thrown to lions, free-thinkers burned at the stake. Both politics and religion have led to astonishing acts of cruelty in the supposed name of progress. It is little wonder that so many of the Mediterranean’s grand but crumbling ruins echo to the savagery of the past and are now the haunt of tragic ghosts and spirits relentlessly re-enduring their torments. Any potential readers new to the Terror Tales series should know that, as editor, I tend to favour supernatural horror, and by that I’m talking monsters, ghosts, faeries, demons, witches and all kinds of eerie and unexplained mysteries. Note, I’m NOT stating that this book will only contain fiction underpinned by folklore, mythology or the supernatural – there is as much terror to be found in tales of killers, maniacs and other manmade mayhem – just so long as you know beforehand that anything you encounter in TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN will be as scary and disturbing as possible.

And if you’re looking for specifics – table of contents, artwork, back cover blurb, pre-order details and the like – keep watching this space.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE HOUSE ON THE BRINK

by John Gordon (1970)

THE HOUSE ON THE BRINK

by John Gordon (1970)

Outline

One early summer’s day on the edge of the Wash estuary, the tidal inlet where Norfolk meets Lincolnshire on England’s east coast, a man and a woman are traipsing through the fens when they spy something half-buried in the mud, which looks as though it might be a body. The man investigates and announces that it’s only a rotted old log. The woman is not placated; she feels certain there’s something evil about it.

A few days later, a reserved but smarter-than-average schoolkid, 16-year-old Dick Dodds, attends his Literature Class’s end-of-term party at the lonely riverside house of his wealthy widow teacher, the neurotic Mrs Knowles, who comments that she recently spotted a horrible human-shaped lump of wood on the edge of the fens and concludes that her house has two sides to it, a good side, from which she can often see the distant ‘silver fields,’ and a bad side, the side that faces onto the river, and the mud, where everything is ‘contaminated’.

These are strange comments, which no one present at the party knows how to take, though Mrs Knowles, who is now romantically involved with a local solicitor, Tom Miller, though only a few others are aware of this yet (and even fewer would approve, given that Knowles and Miller are polar opposites) has a reputation for being eccentric, and many put this down either to her unfortunate bereavement so early in life, or her isolated existence in the marsh-side house, or both.

Dick walks home after the party, somewhat cowed by the vast emptiness of the summer holidays stretching ahead of him. Wondering how he’s going to pass his time, he suddenly, in a characteristic impulse, helps himself to a moored rowing boat, and sets off for an impromptu trip down the darkened river. The folly of this quickly becomes apparent. Dick isn’t much of an oarsman, and in any case, he soon loses the oar, and finds himself drifting deep into the fens, beyond which lies only the open sea.

However, the following day, we learn that Dick survived his escapade. The tide pushed him ashore and he had to plough his way back through deep mud. He now returns with close friends, Jim and Pat, insisting that he needs to recover the abandoned boat, but at the same time, he recalls seeing something strange on his way back inland: an unnatural hollow on the water’s edge, almost as if something large had recently dug its way out, and then unidentifiable tracks trailing away through the mire. He says that when he tried to follow the trail, he felt inexplicably frightened. When he locates the trail again, neither Jim nor Pat see anything curious about it, but Dick still feels frightened and disoriented, putting on such a show that his friends decide he’s making it up and trying to scare them.

Dick goes back to the trail on his own later, following it across the marshy land until it passes close by a farmhouse, which he’s never visited before. While he’s there, a girl of his own age comes out, and tells him that her name is Helen.

They aren’t natural allies, Dick, who lives in the town and is firmly middle-class, Helen, who lives out here on the open country and whose father is a farm-labourer, but for some reason Dick confides in her, Helen, in return, admitting that, on the night of his river-adventure, she too saw something strange, the indistinct shape of a hideous limbless figure gliding along the trail.

Dick is inevitably drawn to Helen, and she to him, not just because they find each other attractive, but because both of them can sense the mysteriousness of the trail when apparently no one else can. The other kids still don’t know whether to take them seriously, but Pat suggests they go and speak to a certain Mrs Shepherd, a local water diviner, to see if she can cast light on the matter.

Mrs Shepherd, who is quite elderly and grandmotherly, confirms that both Dick and Helen are also water diviners, in other words they are sensitive to the presence of water sources below ground – which might, Dick supposes, explain their odd feelings when they are following the trail. However, for no obvious reason, the woman takes a seeming dislike to Dick, warning him not to take the path of other folk in the vicinity, who have used divination for the wrong purposes.

Feeling better now that they have a possible benign explanation for the trail, Dick and Helen relax a little, only to then speak with Mrs Knowles, who, as jumpy as ever, confesses that she fears a local legend about a walking corpse in the fens, the rotted remnant of a medieval warrior who was left behind to guard the site where King John famously lost his jewels in 1216, and was charged with killing anyone who attempts to rediscover them.

Though Dick and Helen now share a budding romance of their own, Dick, who is fond of Mrs Knowles (she was his favourite teacher, after all), is angry and suspects that her mental deterioration is being exacerbated by the presence in her life of Tom Miller, a shrewd but rather cold man whom the boy is convinced is wrong for her. As for her story about the body in the bog, well, Mrs Knowles is clearly going mad.

The boy doesn’t want any more to do with this, except that he feels drawn to investigate further, finally persuading Mrs Shepherd to talk some more. She admits to him that, whatever force lurks in the marshes, guarding the last resting place of the royal gold, there has never been any danger from it previously because the amateur treasure-seekers who hunt through the fens every weekend never get anywhere near. However, she – a genuine dowser – was recently paid by an influential local man to find it, and she got very close before deciding to back off, and it’s this, she fears, that has awakened the guardian of the trove. Mrs Shepherd won’t admit that the guardian is a millennium-old corpse preserved and in fact mummified in the fens, but she tells Dick firmly to stop looking into the case. She also names Tom Miller as her recent employer.

Despite this, Dick and Helen find themselves following the trail again, attempting to dowse with their own homemade rods. Nothing happens and they are ready to chuck it in, when they are led to a gate in a hedgerow out in the middle of nowhere. They’re about to go through but suddenly sense an unhealthy presence.

Any suspicion that this whole thing is down to their overactive imaginations leaves them at this point, when they spy something waiting in the gatepost greenery: ‘a black bald head, faceless’. And ‘a claw, lifted from the gate’.

It’s real after all, the thing from the mud …

Review

The House on the Brink started life as a YA novel, though interest in the book and the author has expanded far beyond those boundaries in the 50+ years since it was published.

At first glance, it certainly looks as though it belongs in that milieu. In fact, it almost seems to predate the YA era: a bunch of intrepid youngsters – the Famous Five or the Secret Seven – skirting around the edges of the ever-mystifying adult world while spending their school holidays investigating a seemingly supernatural mystery. But in truth there are all kinds of things going on in this novel that are nothing whatsoever to do with that, and which have guaranteed its lasting popularity among much older readers.

To start with, there is undeniably a vibe of MR James.

Montague Rhodes James wrote most of his now near-mythical short stories in the first three decades of the 20th century and focussed primarily on antiquarian scholars searching out age-old artefacts, subsequently triggering curses or awakening terrifying revenants. He is still regarded as one of the world’s foremost ghost story writers, and massively well-read even today, thanks partly to his witty, lyrical and succinct style, but also for his ability to evoke a genuine atmosphere of dread.

The House on the Brink is cut from similar cloth, not just in terms of its subject-matter, but in its style, which is very quick and to-the-point, with scarcely a word wasted, and its setting: the bleak eastern edge of England, an empty, sea-begirt landscape, where the wind sighs constantly through the reeds, and forgotten ruins stand lonesome on the distant mudflats. It’s a richly atmospheric location, and dare I say it, John Gordon works it as effectively as Dr James used to, taking his characters, some of whom live in the town, far out of the normal world into a silent wilderness of wildwood, grassland and black, rippling waterways.

The scene at the gate – ‘a gateway to nowhere,’ as the author himself says (gates, edges and brinks being at least as important in this book as they are in MR James) is particularly frightening, coming upon us unexpectedly and yet written in such concise, matter-of-fact fashion, again as Dr James so often did, that mundane normality and supernatural horror are blended together with shocking effectiveness.

Another reason why The House on the Brink is a must-read today, despite being half a century old (and this may be one of the reasons why Valancourt have brought it back, though whatever the actual reason, I’m glad they have), is our recently rekindled interest in folk horror.

Superficially, there is lots of evidence that The House on the Brink was written at the end of the 1960s. The kids are as inquisitive as their predecessors, yet a tad more streetwise. At the same time, though, they are still polite to adults (imagine that!). They do lots of old-fashioned things, like have picnics and ramble around the countryside on pushbikes. They feel bad when they do the wrong thing, rather than object to being reprimanded for it. One of the girls in the group, Pat, still wears a skirt. Jim, the team joker, given to ribbing Dick at every opportunity, does so in a fashion that is almost genteel. But 1970, when this book first hit the shelves, was also the height of the Age of Aquarius. The counterculture of the ’60s was fading fast, but a desire for unorthodox spirituality remained, and with this came a wave of interest in folk horror. You’ll remember the movies of that era, Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973). TV shows like Robin Redbreast (1970), Penda’s Fen (1974) and Children of the Stones (1976). Even Dr Who got in on the act with The Daemons (1971). Then there were public safety films like Lonely Water (1973), some of which took place in those spooky locations where town met country, where children were suddenly beyond adult supervision, where threats to life and limb often took the form of grim entities.

But this genre was also a celebration of Britain’s landscape and its forgotten cultures and beliefs, the relics of which were scattered across the deceptively tranquil georama of British folklore, and that’s particularly the case in this novel.

I’ve already mentioned the gate to nowhere, the mysterious trail or ‘track,’ as John Gordon calls it, which ostensibly is the route taken by the mummified single remnant of King John’s army, though it’s not actually visible, and may indeed be an ancient route traversed by many strange energies, a ley line or whatever. Then there are the ‘silver fields’ as referred to by the disturbed Mrs Knowles; when Dick finally travels out to them, they are little more than a floodplain lying ankle-deep in seawater and thus reflecting the sky, but in Mrs Knowles’s mind, what we’re really talking about here is a near-but-distant magical realm, occasionally visible but always unreachable (Faerie Land, if you like). Mrs Knowles’s weather-beaten house serves a similar purpose. To the calculating Tom Miller, it’s nothing more than a refuge for his troubled sweetheart and also, probably, a key part of the lucrative future he plans for himself, but to Mrs Knowles it’s a border stronghold, the first (and last) human habitation before the vast sweep of the unknown.

But perhaps the most obviously grown-up part of The House on the Brink is the coming-of-age story.

So many horror and fantasy writers over the decades have trodden this path, reliving their own experience of the transition from childhood through the prism of the scary story, their adolescent unease about the years ahead dressed up as monsters or demons. This is very much the case in The House on the Brink .

Dick Dodds is 16, and in 1970 that meant that his next step was adulthood. Few people then had time for kids who didn’t really know what they wanted, or who were looking for ‘a year out’ or who just wanted to keep on being students. But because attitudes were different, that didn’t mean it was easier for the youngsters. There are times when Dick feels lost in the mysterious emptiness of the landscape, even though he has grown up here. Is this a metaphor for the uncertainties ahead? It’s the same with his and Helen’s relationship. They are still too young to be proper boyfriend and girlfriend … so much so that they’re embarrassed to admit this is what they are, and don’t like it when adults make that assumption. They kiss but there’s not much amorousness there. They’re stuck at that midway stage, on the edge-land. It’s no wonder everything is confusing, particularly the behaviour of the adults in the book, who they no longer view as distant, omnipotent controllers of all their lives, but as near-equals, flawed and troubled themselves, yet whose moods and motivations they still can’t read properly.

All that said, I don’t want to make The House on the Brink sound as if it’s heavyweight stuff. It actually isn’t. At heart, it’s a gentle if very eerie, but also rather straightforward ghost story. It also only runs to 161 pages, so it’s an easy and accessible read. And yet it’s successful at every level. It has well earned its reputation as a classic slice of supernatural nostalgia, which will frighten and delight in equal measure.

And now, for once, I’m not going to bother trying to cast this beast in the event it ever gets adapted for film or TV. This one is all about the young leads, which means it would need genuine teenage actors, and I don’t know enough about the younger end of the current acting market to offer any kind of valid opinion.

Published on July 17, 2023 01:13

June 23, 2023

Key moments that steered me into writing

I hope you can forgive me a few personal moments this week. For some time now, I’ve been pondering an occasional series of articles about those events in my life, those key moments, that steered me towards the writing profession. I held back for a little while. Would it be too personal, too introspective? Or would it be interesting? Well, you guys can judge, because I’m taking a chance and getting that ball rolling today.

In addition, I’m taking this opportunity to remind everyone that about my upcoming two-hander event with my fellow thriller-writer MW Craven in the very near future (it’s only 11 days away, in fact), in Cumbria. So, I’ll be chatting at little about that too.

On which subject, and on a not unrelated note, today would also seem an opportune time to offer a detailed review of Mr Craven’s latest masterwork, FEARLESS, an all-out action thriller set out in the sun-blistered wastes of the Chihuahuan Desert (so, a particularly good one to read this flaming June).

If you’re only here for the Craven review, I’ve no problem with that. You’ll find it as usual in the Thrillers, Chillers section at the lower end of today’s column. Before then, here’s the other stuff ...

Meeting our public

A quick reminder that on Tuesday July 4, MW Craven and I will be chatting to our public in the Kendal branch of Waterstones, and event running 6.30 to 9pm. Mike will be talking about FEARLESS , his explosive new action thriller, and very likely the commencement of a brand-new series, while I, briefly, am veering away from the world of guns, armed robbers and terrorists, to discuss USURPER , my most recent novel, which is also an action adventure, but this one set 1,000 years ago at the height of the Norman Conquest of England.

The overlap is the full-blooded action, folks. Don’t be fooled into thinking that these two books are a mismatch. All that really matters, though, is that we’ll both be there to chat and answer questions about our methods and motivations, any plans we may have for the future and so on, and to sign every book that are put in front of us, not just the new ones. (I also hear that anyone there who buys both books will receive a £5 discount on the total cost!)

Here’s a shot from last year’s event, when Mike was presenting THE BOTANIST and I was presenting NEVER SEEN AGAIN . You’ll notice that my dogs, Buck and Buddy, also got in on the act.

Anyway, Feel free to pop along to the next one, folks. Get your tickets HERE . I guarantee a fun evening.

And now, something else that yet again is not entirely unrelated ...

MOMENTS THAT MATTERED

What on earth is it that could make you want to be a writer?

I suppose on one hand, you could argue that the most basic requirement is to be pompous enough to believe yourself so important that others will pay to read your words.

To be honest, that’s pretty undeniable.

But on the other hand, joining the writing profession is also quite a laudable act.

Firstly, because it means you’re seeking to share wisdom, learning, expertise and even personal interest in a manner that you hope will entertain and inform others. Secondly, because you attach such value to this prospective profession that you are prepared to put in the hard yards, in exchange for rewards which, at best, can be variable and uncertain, and at worst, non-existent. In other words, you’re undertaking a vocation that you really believe in – and that’s surely a good thing, but the fact that you’re doing something ‘good’ may be the best you ever get out of it.

Firstly, because it means you’re seeking to share wisdom, learning, expertise and even personal interest in a manner that you hope will entertain and inform others. Secondly, because you attach such value to this prospective profession that you are prepared to put in the hard yards, in exchange for rewards which, at best, can be variable and uncertain, and at worst, non-existent. In other words, you’re undertaking a vocation that you really believe in – and that’s surely a good thing, but the fact that you’re doing something ‘good’ may be the best you ever get out of it. But of all the writers I’ve met during my life, I can’t name one who ever told me that he or she came into this world with this ambition already hardwired into them. So many, if not all, seem to have muddled their way into the profession.

Even those among us who toyed with the idea of becoming writers when we were young often had other careers to take care of first. Some of these we might have enjoyed a great deal. Others we merely tolerated because we had to get the money in. Either way, they filled our time and thoughts.

But every one of us, I’m certain, has also experienced ‘Damascene moments,’ in other words has suddenly been struck by an astonishing revelation or motivation that we never saw coming, and which, while it might not have jolted us into the world of authorship at that very moment, became a persuasive factor as we continued forward in life.

But every one of us, I’m certain, has also experienced ‘Damascene moments,’ in other words has suddenly been struck by an astonishing revelation or motivation that we never saw coming, and which, while it might not have jolted us into the world of authorship at that very moment, became a persuasive factor as we continued forward in life.Was the spur in fact, that would drive us on towards a very different future.

So … I thought it might be fun over this blogpost and several in the future, to highlight a few of these seminal moments in my own life when the die was indisputably cast, when I realised that there was something vastly more satisfying I could be engaged in.

Now before we start, what I am NOT talking about here is the actual, physical moment when I moved into full-time writing. In my case that was something beyond my control. It involved a series of unexpected redundancies, which, ultimately, though none were welcome at the time, removed that very difficult decision about whether or not to pack my day job in. But that’s not a particularly exciting story. The moments I’m looking for in this new occasional series are those instances of divine inspiration. Those moments when your vision clears, everything falls into place, and your reason for existing in this world is suddenly made very plain to you …

SPUR #1 – GRANADA TELEVISION

One of my greatest inspirations, and I’m aware that I’ll need to explain this, was Granada Television.

My father, Brian Finch, was a screenwriter with a career that spanned four decades, his CV ultimately containing a wealth of successful programmes: Coronation Street , The Tomorrow People , Captain Scarlet , Murphy’s Mob , Bergerac , Hunter’s Walk , Public Eye , All Creatures Great and Small , among many others, culminating of course in the BAFTA he won in 1999 for Goodnight Mister Tom .

Yet, this wasn’t the whole story.

As I grew up in Wigan in the 1960s and early 1970s, my father was a local news reporter and a wannabe writer who was still jobbing his talents around. The earnings weren’t particularly great, of course.

Though I’ve undoubtedly led a mostly middle-class existence, we were a working-class family by origin, my two grandfathers a coal miner and a gasworks foreman. I myself spent my formative years living in a terraced house. I only mention this to show that, as a youngster, I had a very conventional experience of the industrial northern town that was Wigan.

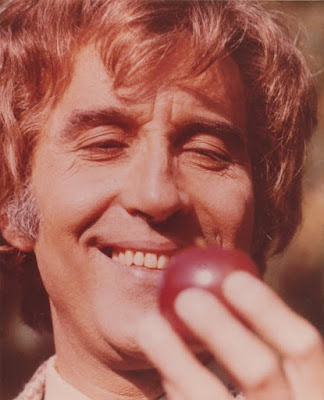

And yet, somehow, as we progressed into and through the 1970s, my father’s writing career blossomed, and more and more celebrities came in and out of our lives. (The image right shows my Dad at a

Coronation Street

party with Violet Carson, aka Ena Sharples, some time circa 1969/1970).

And yet, somehow, as we progressed into and through the 1970s, my father’s writing career blossomed, and more and more celebrities came in and out of our lives. (The image right shows my Dad at a

Coronation Street

party with Violet Carson, aka Ena Sharples, some time circa 1969/1970).I honestly could spin a hundred anecdotes relating to this.

For example, when the phone rang one evening and my mother answered, a boomy and distinctive voice asked: ‘Is Brian there?” When my mother replied, “I’ll just get him for you, Frankie,” the voice said, “How did you know it was me, dear?” My mum: “There’s only one Frankie Howerd.” The voice: “Ooooo!”

Then, there was the script-meeting in our front room for my Dad’s Rugby League drama, Fallen Hero , where the ever-lovely Wanda Ventham (Benedict Cumberbatch’s mum), had to eat some of the most appalling looking cheese sandwiches, which my Dad had just made, and did so without complaint because they’d been working all day and were starving.

In a similar, informal way, my Dad introduced me to Del Henney and Ken Hutchison, two screen hardmen so convincing in those roles that you’ll probably remember them playing the two lead villains in the movie thriller,

Straw Dogs

, but a couple of actors who were also so versatile that they’d play good guys in my Dad’s dramas.

In a similar, informal way, my Dad introduced me to Del Henney and Ken Hutchison, two screen hardmen so convincing in those roles that you’ll probably remember them playing the two lead villains in the movie thriller,

Straw Dogs

, but a couple of actors who were also so versatile that they’d play good guys in my Dad’s dramas.I could go on and on about this, but it would get boring.

The point is that it was all so gradual a process that I wasn’t aware of it being anything unusual. If my Dad casually mentioned that he’d just been speaking on the phone for half an hour to Boris Karloff, it meant nothing to me. These were the sorts of people my Dad knew.

Which brings us back to Granada Television, the home of Coronation Street , and umpteen other shows my Dad worked on.

Granada TV was the brainchild of media mogul, Sidney Bernstein, and one of the original four independent television franchises created in 1954. It covered Manchester, Lancashire, Merseyside, Cumbria, Cheshire, North Wales and parts of Yorkshire, and was praised by TV critics for the distinctively northern and ‘socially realistic’ nature of its programming.

My Dad considered it the thumping heart of independent television in that era. I visited the studio with him again and again over many years, to drop scripts off, to watch the filming of Sherlock Holmes (and get to shake hands with Jeremy Brett), or to stand quietly by while he discussed potential new children’s shows with such diverse TV personalities as Ken Dodd and Charlie Caroli.

When it came to widespread family entertainment, Granada TV was unbeatable. And yet, it never felt like a privilege being there and interacting with those who were integral to it.

Until the early 1980s, when I left civilian life and joined the Greater Manchester Police.

You may wonder, given the background I’ve just outlined, what the hell possessed me.

Well, ever since I was a lad, I’d always wanted to be a copper. Even though I’d been a dab hand at writing stories while at school, in my early adulthood I had no interest in that. I wanted to go out and lock up villains. Even when I was being interviewed for the job at Chester House, the chief superintendent on the other side of the desk said something to the effect of: ‘Your father’s a well-known television writer. Do you not want to do the same thing?’

Well, ever since I was a lad, I’d always wanted to be a copper. Even though I’d been a dab hand at writing stories while at school, in my early adulthood I had no interest in that. I wanted to go out and lock up villains. Even when I was being interviewed for the job at Chester House, the chief superintendent on the other side of the desk said something to the effect of: ‘Your father’s a well-known television writer. Do you not want to do the same thing?’ I gave what a thought was a very honest answer, perhaps riskily honest. I said: ‘I may do at some point, but I’ve no interest in that yet.’

To which he smiled and said: ’Well, if nothing else, we’ll certainly give you lots of grist for that mill.’ (And how prophetic that turned out to be).

But the yearning to write didn’t come yet. In many ways, the job completely absorbed me, left its mark even when I was off-duty. You worked long and difficult hours, were in constant high stress situations, and spent almost every shift dealing with people who were having the worst day of their lives. The difference between dreaming about the police and policing for real is an abyssal gulf.

Some of it was terrifically exciting, but some of it was more than a little bit depressing.

For example, when you went into rooms, often in the most desolate parts of town, that you would never forget as long as you lived ... rooms you would keep on revisiting in your dreams.

On one such occasion, after I’d discharged all my duties as a first responder, I remember stomping up the stairs to the roof of the high rise in question, and gazing bleary-eyed across the silent, benighted cityscapes of Salford and Manchester, finally focussing on that distant neon sign, shimmering cherry-red: GRANADA TV.

A rush of happy memories came back to me. For half a second, at that terrible time in that terrible place, I was relocated back to my early life, when I’d been surrounded by these stars of stage and screen without really knowing it, when I’d been immersed in that atmosphere of entertainment and creativity, which I’d so taken for granted at the time.

I knew there and then that I didn’t just want to go back to that world, I had to.

That was where I belonged. Not this one, as personified by that room downstairs, now in a state of chaos, the world and his brother having arrived (all too late, of course, as we nearly always were).

I’m not sure why my ambition suddenly came alive at that moment. I’d seen the Granada TV sign many times during my police service and thought nothing of it. Yes, I had vague memories of those heady days, but always considered them the distant past, a fantasy childhood that could never have meaning for me long-term. And yet somehow, that night, that sign became the most potent lure.

I signed off at the end of that shift with one objective in mind. I was leaving the cops, and by hook or by crook, I was going to worm my way into my Dad’s world … or something close to it.

(To be continued ...)

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

FEARLESS

by MW Craven (2023)

FEARLESS

by MW Craven (2023)

Outline

Ben Koenig is a US Marshall with the Special Operations Group. Or rather, he was. At present, he’s dropped off the grid. Six years ago, he shot dead a suspect while closing in with his team on an isolated ranch where a particularly loathsome bunch of deviants were making ‘toddler versus attack dog’ movies. The deceased suspect happened to be the son of a leading member of the Russian Mafia. The Russian mob themselves were not involved in the vile racket, in fact they deplored it, but rules are rules, and as such, Koenig was marked for death.

He’s been on the run and lying low ever since.

We join the narrative with Koenig in Wayne County, New York, where, as usual, he is minding his own business. Until he is bewildered to learn from watching TV in a bar that he has made the US Marshals’ ‘Most Wanted’ list.

Even Koenig, skilled as he is, finds it difficult to disappear again when his face is suddenly on every TV screen, and he is subsequently arrested by local cops. However, this is only a ruse. In reality, US Marshals Service director, Mitch Burridge desperately needs to make contact with him. They are old mates who go way back, and Mitch would normally respect Koenig’s desire to stay out of sight, but a very serious situation has now arisen.

In short, Mitch’s pre-grad daughter, Martha, has been abducted. Inevitably, a range of security services are already on the case, but Mitch wants Koenig involved too. Not just because he’s a human bloodhound – the Devil’s Bloodhound, as some crims have come to refer to him – but because at present he’s an unofficial asset. He’s also an apex predator. If Martha Burridge is dead, as her father fears, he wants Koenig to kill those responsible.

Koenig is certainly ideal for this kind of work. Earlier in his career, a raid went south, and he was shot in the head. He survived it, but during the subsequent operation, the brain surgeon discovered that he was suffering a rare degenerative condition called Urbach-Wiethe disease, which normally causes an abnormal fear of just about everything, though in some cases, exactly the opposite can result: the patient finds that they have no fear of anything at all.

In Koenig’s case it’s the latter, which officially at least meant that further service in the field would be problematic. A man without fear could pose a high risk, not just to himself, but to his colleagues. Not wishing to lose a talented operator like Koenig to permanent deskwork, the Service responded by sending him off to train with some of the world’s most elite spec ops, the SAS, the Navy SEALS and so on, where he would compensate for his lack of fear by learning how to make professional judgements based on knowledge and acquired skill. It also meant that, when he finally got back in the field, he was by far the deadliest man in the US Marshals.

Living up to this reputation, Koenig guarantees Mitch that he will find Martha, or discover what happened to her, and will do whatever it takes to make this happen.

The first part of Koenig’s investigation takes him to DC, and Georgetown Uni, where Martha was studying. Her academic supervisor, Robin Marston, is a Marxist professor who regards it as his civic duty to impede law enforcement wherever he can. Koenig has no time for this, and gets rough with Marston, leading the frightened academic to admit that he hasn’t given all of Martha’s files to the Washington PD. However, before Marston can retrieve the info he has held back, he is shot and killed by an unknown female assassin, who takes out a campus cop at the same time.

Perhaps inevitably, Koenig, who’s already knocked Marston around, is blamed, and finds himself back in custody, in a local holding cell. While he’s in there, on suspicion that he’s just another crazy shooter, two white supremacist hoodlums are put in with him, clearly under orders to finish him off. The resulting fight is violent, but it leaves one of the neo-Nazis dead and the other badly injured. Frustrated, the cops look to charge Koenig with murder anyway, only for one of their senior ranks to engineer his escape from the precinct.

Increasingly suspecting that this whole thing is a set-up, and that somehow or other, there is official involvement in the kidnapping of Martha Burridge, Koenig has no choice but to accept the cops’ escape route. At which point he is confronted by an old colleague of his, Jen Draper, a top agent who also happens to hate him. Unsure what to make of this, Koenig stumbles to a halt.

Draper meanwhile, raises her pistol. And fires …

Review

In my opinion, the acid test for any thriller is whether or not it thrills. Does it intrigue you? Does it excite you? Does it keep you hooked? It’s not a genre for which great writing and unforgettable characters are often considered essential ingredients, which makes MW Craven’s work all the more impressive. Because if there is one thing Mike Craven is, it’s a hell of a writer across the board.

First of all, let’s deal with the thriller aspects of Fearless , because they are here in abundance.

A few reviewers have suggested that Ben Koenig will be the new Jack Reacher. At first glance there are undeniable similarities. Like Reacher, Koenig is a drifter out there in the vastness of the US. Also like Reacher, he has a law-enforcement background but is also highly trained in the skills of violence. In addition, though he’s as rough and ready as they come on the outside, he also has a deep moral sense and innate hostility to those who do wrong, at whatever level of society they predate on the innocent. And again, pretty much like Jack Reacher, he encounters these warped individuals plenty often during his ramblings.

But here, to be honest, the similarity ends.

Koenig is not a physical giant who can knock six guys out with a single punch. By the same token, he is still, officially at least, a cop rather than a vigilante, and the investigations he often undertakes are official, albeit the legalities are clouded by the sort of uncertainties that only black ops can generate. (All this said, it would be remiss of me not to mention the amusing moment in the novel, when Mitch Burridge remonstrates with Koenig for going ‘all Jack Reacher’ on them).

If anything, for me, there are probably more links between Ben Koenig and one of Craven’s parallel characters, Washington Poe. At first glance, you might disagree. Poe, you’d rightly argue is a regular police officer based in the north of England, and he is governed by the numerous controls that prevent British cops using extreme methods. But Poe, who also has a military background, resents that. He can function inside the framework, but he doesn’t like it. He’ll readily strongarm villains if it’s required, because he sympathises with the law-abiding public ahead of them. On top of that, he’s an arch-cynic, and displays this attitude with just about everyone, friend and foe alike, and definitely to his superiors. In all these ways, and others, he is similar to Koenig, though Koenig, by the nature of who he is and what he does, and because he has almost no limits imposed on him in his efforts to secure justice, is the next stage along in terms of ferocity.

Koenig also has the fearlessness factor, which is an ingenious way of explaining the recklessness he displays in his pursuit of the novel’s antagonists (and also a good way for the author to make him seem unreliable to his superiors without calling his abilities into question).

If I was to liken Ben Koenig to any other action hero currently bestriding the genre, it would be Robert McCall, as interpreted by Denzel Washington in The Equalizer franchise, because Koenig, while he often keeps tight control of himself, is guaranteed bad news for the opposition in that he’s ruthless and vengeful, and when he tells a bad guy that he’s going to kill him, you know that it’s no idle threat. But also, and this is the most intriguing aspect of Ben Koenig, because he is so amazingly disciplined and methodical.

Because this novel is written in the first person, it’s full of fascinating thought processes, as Koenig makes highly professional assessments of each and every predicament, reminding us constantly about the psychology of the opposition, about the potential of different weapons, about the advantages and disadvantages posed by each new location, about the best vehicles to use, about the distances he’ll need to travel, and the speed he’ll need to travel at, in order to disarm, cripple or kill an opponent, even about the different means available to him, sometimes which he must go out of his way to acquire, to foil sophisticated alarm systems or fox professional security staff.

There is a plethora of such info in Fearless , but at no stage is it intrusive. For me, it illuminates the book, first of all because it assures the reader that our main protagonist is a real professional who knows exactly what he’s doing, and secondly because it offers a full and convincing explanation for why our main hero wins such regular and improbable victories. It absolutely is NOT the case, as we were so used to in Schwarzenegger and Stallone movies, that Koenig just turns up at the crucial moment, often having blundered his way there, and takes out every bad guy either because he has a bigger gun than they do or because they’re just rank poor shots.

And yet this explanatory undertone is all done so succinctly and so interestingly that you can’t help but be seduced by it. And that brings me onto the quality of the writing itself.

Whether he’s describing tense one-to-ones between vividly drawn and distinctive characters (all multi-levelled, not all of them even remotely likeable), whether it’s atmospheric description of the unforgiving badlands or, yes, those frequent, bone-crunching action sequences, Craven hits the mark each time. He’s a wordsmith of high technical skill. He can paint pretty pictures, but he keeps then tight and ultra-believable, and he knows how to let the narrative flow. It’s superb writing all-round, and it totally merits that overly-used honour ‘unputdownable’.

More than likely, you’ll already know what you’re going to get with Fearless , but I’d just reiterate that this is one serious cut above the rest of the action-thriller genre. It’s high-quality work, and all built around an intriguing new character, who frankly, has got film and/or TV written all over him.

And now, here I go with my usual ill-advised attempt to cast this beast before the real film and TV people get their grubby mitts on it. It’s only a laugh, but hell, someone’s got to do it.

Ben Koenig – Sebastian Stan

Jen Draper – Emily Blunt

Mitch Burridge – Forest Whitaker

Peyton North – Scott Adkins

Samuel – John David Washington

Published on June 23, 2023 03:03

May 20, 2023

Gloating over a lavish Terror Tales review

Today, I thought it would be nice to share a really cool review of TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY courtesy of Rosemary Pardoe, editor of GHOST AND SCHOLARS, and one of Britain’s most respected and well-informed experts on the traditional ghost story.

Today, I thought it would be nice to share a really cool review of TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY courtesy of Rosemary Pardoe, editor of GHOST AND SCHOLARS, and one of Britain’s most respected and well-informed experts on the traditional ghost story. Also, in the spirit of TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY, I’ll be running a gallery of folk horror on film, but specifically picking movies that are perhaps less well known or less associated with that genre.

While we’re on the subject of rural horror, I’ll also be offering a detailed review of the late Michael McDowell’s 1979 classic, THE AMULET.

If you’re only here for the McDowell review, that’s A-okay as always. Just hop straight down to the Thrillers, Chillers section of today’s blogpost, and you’ll find it there.

Before then, however, let’s get back into the world of …

Terror Tales

TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY is the 14th in the TERROR TALES series. For anyone who hasn’t encountered these books yet, they are a series of folklore-based horror anthologies, each one set in a different geographic region. They comprise both fiction (mostly original and from some of the best ghost and horror writers in the field) and snippet-length ‘true terror’ anecdotes.

TERROR TALES OF THE WEST COUNTRY kind of speaks for itself. It’s all about England’s mystical West Country. I don’t think I need to say too much more about that. Anyway, the amazing Ro Pardoe of GHOSTS & SCHOLARS fame has finally cast her discerning eye over it, and on the whole seems to approve. I hope she won’t mind if I include a few quotes from her, as we work through her various high points.

Ro heaped praise on the ‘incredibly impressive’ line-up and, in no particular order of preference, singled out a number of specific stories for praise, including Dan Coxon’s

The Darkness Below

, which she likens to Ramsey Campbell at his best, and summarises as ‘when a family visits Gough’s Cave at Cheddar Gorge, are they the same people who come out, and if not, which of them has changed?’ She also mentions Lisa Tuttle’s

Objects in Dreams May Be Closer Than They Appear

, which she calls ‘a fine tale of nightmarish time entrapments, and a Devon house visible on Google Satellite View which is almost impossible to find on the ground (it would have been better for the narrator if it had been completely impossible to find).’

Ro heaped praise on the ‘incredibly impressive’ line-up and, in no particular order of preference, singled out a number of specific stories for praise, including Dan Coxon’s

The Darkness Below

, which she likens to Ramsey Campbell at his best, and summarises as ‘when a family visits Gough’s Cave at Cheddar Gorge, are they the same people who come out, and if not, which of them has changed?’ She also mentions Lisa Tuttle’s

Objects in Dreams May Be Closer Than They Appear

, which she calls ‘a fine tale of nightmarish time entrapments, and a Devon house visible on Google Satellite View which is almost impossible to find on the ground (it would have been better for the narrator if it had been completely impossible to find).’ Inevitably, Ro, an expert on MR James, is exceedingly fond of the volume’s antiquarian stories. Of John Linwood Grant’s The Woden Jug , she writes ‘in Somerset, an apparent stoneware witch-bottle, decorated with a one-eyed face, turns out to be a protection not against witches but against something else entirely’, and calls it ‘a good one’. Ro wastes few words when she likes something, so this is praise indeed.

Another antiquarian tale she enjoyed was Stephen Volk’s Unrecovered , which she says stands out in the volume, adding ‘it begins in familiar territory, with the archaeological excavation of a Wiltshire Anglo-Saxon cemetery, and the sighting of a distant figure with only half a head … but the horror is of a more recent war and the trauma of losing a buddy on the battlefield. I can’t deny that I shed a tear’.

There are three main Dartmoor-set stories in the anthology, an ancient landscape that has proved a happy hunting ground for horror writers going way back, and Ro seems to have particularly enjoyed these. She was pleased that in Thana Niveau’s Epiphyte , ‘the supernatural threat takes an unusual form’, and says of Adrian Cole’s Land of Thunder that ‘a horrific episode in the history of Dartmoor jail produces revenants raised by a much older force on the moor’. But above all, the story she considers the best in the book, is Steve Duffy’s Certain Death for a Known Person . Those who don’t know Steve Duffy’s work need to rectify that, as he’s an author of exceptional skill. Of his story here, Ro writes, ‘I don’t know many authors who could turn what is essentially a Twilight Zone -type plot about Death personified, and an agonising choice that needs to be made into something as introspective and deep’.

As for own contribution, Bullbeggar Walk , which is ‘set on Exmoor, where a church’s stained glass window provides a vivid depiction of the legendary Bullbeggar, a monster created through a disagreement between an Anglo-Saxon and a Norman in the 11the century,’ Ro describes it as ‘effective’.

Well … I told you that she doesn’t waste words.

Secretly, I’m most pleased that Ro likes and appreciates that time that has gone into my own creation of the anecdotal ‘true’ stories that intersperse the works of fiction. These are great fun but time-consuming to research and write. For the most part, reviewers seem to appreciate them, but Ro says of them that they ‘are among the highlights of the book’.

Anyway, the overall review is far more extensive than I’ve quoted here. If you want to read it in full, you’ll need to get hold of Ghosts & Scholars 44 . However, I’d like to thank Rosemary for taking the time and trouble to offer her opinions and provide us with what amounts to a detailed, fulsome and very warm-hearted review of the latest book in the series.

On the subject of TERROR TALES , a few quick words now about the next one in the series, which will be TERROR TALES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN. You may consider that an unusual break-away from our more normal British-set volumes, and it probably is, but I’d draw your attention to the fact that we did TERROR TALES OF THE OCEAN in 2015, which obviously wasn’t British-bound, and maybe was a sign of things to come. After all, in the next two or three years, we’ll have run out of locations in mainland Britain. We opted to visit the Med this time around, with one or two UK locations still remaining, just to freshen things up a little and to check out the lie of the and where our readers are concerned.

I beg no one to entertain even the remotest possibility that this location might not ‘do it for them’ in horror terms. Already, and the book is nowhere near ready yet, we’ve found some visceral terror in the secretive halls of Turin’s satanist university, in the Spanish/Pyrenean castle where a decadent and brutal vampire lurked, and among the mist-shrouded origins of some of that ancient region’s most terrifying monsters … among many others.

And now, just for the hell of it, let’s check out a gallery of …

Lesser known folk horror