Paul Finch's Blog, page 7

December 17, 2020

Anyone up for another seasonal screamer?

Christmas seems to have come astonishingly quickly this year. Too quickly, alas, for the vaccine to really save it. Unfortunately, we’re going to have a very stripped-down version of the festive season in 2020. However, there’s one tradition you can rely on as much this year as in all those past. And that is my annual posting of a seasonal horror story on this blog.

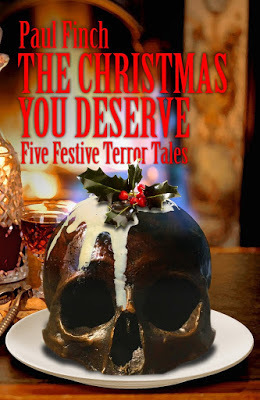

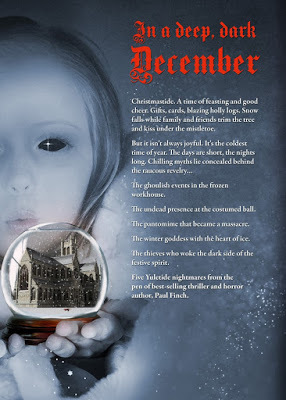

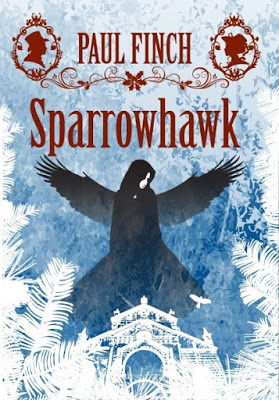

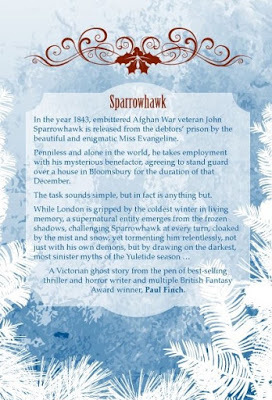

I must admit that 2020 has been an unusually busy year for me on the short story-writing front. Though I’ve been eyebrows deep in my novels as well (ONE EYE OPEN came out in August), I’ve somehow managed to find the time to bring out a new collection of Christmas ghost stories, THE CHRISTMAS YOU DESERVE, to re-issue an older collection and an older novella, IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER and SPARROWHAWK, and to publish via SAROB PRESS a hardback collection of four brand-new folk horror novellas, ILL MET BY DARKNESS.

The upshot of all this is that the short story I’ve posted on here today is a reprint. However, it’s an old and venerable one. It’s only seen the light of day once before, and that was in my first collection, AFTER SHOCKS (from Ash-Tree Press), which won the British Fantasy Award for Best Collection in 2002. Several clues as to the story’s age should reveal themselves as the narrative progresses. For that same reason, I’m confident there’ll be a considerable number of people to whom this tale is completely new.

The upshot of all this is that the short story I’ve posted on here today is a reprint. However, it’s an old and venerable one. It’s only seen the light of day once before, and that was in my first collection, AFTER SHOCKS (from Ash-Tree Press), which won the British Fantasy Award for Best Collection in 2002. Several clues as to the story’s age should reveal themselves as the narrative progresses. For that same reason, I’m confident there’ll be a considerable number of people to whom this tale is completely new. It’s called THE FIMBULWINTER, and while I wouldn’t call it a Christmas story per se, it’s set deep in a very dark December indeed, and hopefully can be categorised as one of my scariest stories of the wintertime.

So, we’ll get straight to it this year. I won’t bore you with any lectures about why we love spooky stories at Christmas. There’s an awful lot of stuff on that subject already out there, I’ve noticed; something to do with this grimmest of all years, I suspect. But before we get going, I’ve at least got time to wish you all a very Merry Christmas and, in case we don’t have contact again before 2021, a Happy New Year (certainly a much happier one than many folk had in 2020).

Hope you enjoy the story …

THE FIMBULWINTER

Manning first suspected there was something wrong when snow fell in mid-October.

Had it fluttered down for an hour and melted, he’d probably have forgotten about it by the following morning. But as it came down thick and heavy, smothering the hills of northern England and continuing uninterrupted for day after day, week after week, his misgivings grew. By November, it covered the entire country and what felt like polar winds were blowing. Bonfire Night was unofficially cancelled; a few hardy souls chanced it, but temperatures were six below that day and it was blizzarding again, so scarcely a firework was seen. Come December, the dales around Heatherby, the Yorkshire town where Manning and his two constables ran the sub-divisional police station, were more like the Russian Steppe. The wolds were wind-blasted tundra; rivers and streams had lain frozen for longer than anyone could remember; climbers and walkers were lost on a daily basis. Things were no better in the town itself: there was traffic chaos, pipes and cisterns broke, power lines came down.

The weather people remained cheerful about it. It was the same all over Europe, Asia and North America, they said. Even Africa was having its coldest spell this century. And anyway, Britain was long overdue a hard winter. We’d been spoiled in previous years. The Met Office admitted some surprise at the protracted severity of the weather, but blamed it on a high pressure system sitting stubbornly over Scandinavia and pulling cold air down from the Arctic. Opinions were divided among Greenhouse Effect theorists, some concerned that it discredited their viewpoint, though as one frizzy-haired, jumper-clad professor insisted on a TV chat show, it could also be considered proof positive that things were “going wrong”, many of his colleagues fearful that the first casualty of global warming was always going to be the Gulf Steam, which tended to keep Britain warm and moist during all but the deepest months of the winter.

Sergeant Manning didn’t know much about the Gulf Stream, but he did know that something was “going wrong”. As he guided his police Range Rover up the precarious road to the Mawby Hill estate on the afternoon of December 13, his wheels crunching and sliding in deep snow, he thought about Geraldine’s odd mood that morning. His wife taught at Heatherby Juniors, and had been working with her pupils on Norse myths. Thus, when she’d drawn back the curtains that day on a world yet again blanked-out, she’d spoken about the legendary winter-of-winters, and how it was supposed to herald the destruction of the world. She’d tried to laugh about it, but only in a sombre way.

Manning hadn’t been listening. Instead, he’d grabbed her from behind, kneading her breasts through her nightie, nuzzling her neck, hoping for a spot of nookie before work. But Geraldine hadn’t responded. The same despondency had settled on her recently that had affected so many others over the last few weeks. Her handsome features were morose and drawn; there were dark circles under her eyes. She wasn’t at school that day; the plumbing was down and they were waiting for engineers to arrive from Huddersfield to fix it, but normally she’d still be up and about. On this occasion, she didn’t even get dressed, let alone start the day’s routine of tidying-up and marking.

Manning wished he had time for such fancies. He didn’t say it openly, but civies made him laugh. There hadn’t been a single day in his entire working life when something as mundane as fractured plumbing had sent him home early. And on a day like this, it was a good thing. Harsh weather kept the criminals at bay, but it brought in a rash of other irritations. There were frequent road accidents for example, not to mention regular checks to make on the district’s more remote hamlets.

On top of all that, a fissure had appeared alongside the trunk road leading south to the M62, and another at the bottom of the seventy-foot escarpment at the top of which sat Mawby Hill. They’d been impressive to look at: yawning cracks in the ground, perhaps a metre or so across and in both cases of indefinite length. He wasn’t sure how deep they were, either, but the snow was pouring in and showing no sign of filling them up. Born and raised in the West Yorkshire coalfields, Manning had seen this sort of thing before and it disturbed him. Heatherby had originally been a farming village located at the confluence of several high valleys. However, it had expanded and changed over the centuries to meet the demands of industry and parts of it, especially those residential districts along its southern edge, had been built on uneven coal tips now long disused. As far as he knew, these were safe, heavily compacted, while more recent and therefore looser workings were further down the valley, out of harm’s way. It was just possible though, that the extreme cold had caused some kind of subsidence. Manning wasn’t taking any chances; he’d fenced the cracks off with traffic cones and bright yellow incident tape, just about every inch he had in the station, and was now waiting for word from HQ. Inevitably, in this weather no one was able to do anything in a rush.

Now he had an even weirder job on. Someone on Mawby Hill had reported children frightened by “a very tall man”. As he reached the estate and slowed to a halt at the end of the first street, he wondered just how tall you had to be to frighten the kids of Mawby Hill. Since the pit closure, the estate was almost fully unemployed and what youngsters there were tended to be tearaways.

The road ahead, meanwhile, was bare of life, arrowhead flakes sweeping over it. No-one had gritted, so every surface was deeply buried. Parked cars were visible as rounded hummocks. The Pennine hills, which always made for a scenic backdrop, were indistinguishable from the sky. The few Christmas decorations sparkling from windows had a meagre, half-hearted look about them. Theoretically, white Christmases were adorable, but the weeks and weeks of persistent snow, and the endless problems it caused in a country not geared up to deal with it, were subduing everyone’s mood.

Slowly, Manning gunned the Range Rover forward, the windscreen wipers thudding. Aside from that, there was a muffled silence. He prowled the streets with painstaking slowness, but saw no-one at all, let alone “a very tall man”. He didn’t doubt that something had gone on, however. Even this weather, too cold for children to sit in class, would not be too cold for them to go out snowballing. So, it was hard to explain why they weren’t. He grabbed his radio. “Manning to Six!”

“Go ahead, sarge,” came a tinny voice from the Comms Suite at Slaithwaite.

“Yeah, Jen. I’m on the Mawby now. No trace of anything unusual. No trace of anything, in fact. I’m not happy, though. Think I might knock on a few doors.”

“Received, sarge. Listen ... before you do, can you look at a ‘vulnerable’?”

Manning groaned. Likely as not, this would mean a trip to some even more remote spot. He was glad he had his shovel in the back. “What about 1415, Jen?”

“Negative on that, sarge. I can’t raise Marty.”

“What do you mean you can’t raise him?”

“Not answering his radio, sarge. You know what he’s like.”

Manning snorted. He knew exactly. Marty Culvin was a long serving street-bobby but prone to extreme laziness. Days like this were ideal for parking up somewhere and having a snooze. He’d often turn his radio down so as not to be disturbed by static. “Keep trying him, Jen. And when you get him, tell him he’s in for a bollocking. Let’s have the details.”

*

Charlie Hardaker had been a gamekeeper during his working life. Now he was retired. Very, very retired.

Manning stood by the broken-down door, staring at the corpse in the middle of the kitchen. He’d been in the job twenty-five years, most of it spent in inner city areas of Bradford and Leeds, and had seen some abominations: a lonely woman who’d died from a heart attack and over the following month had been devoured by her starving Alsatian; a teenage girl raped then macheted, both arms lopped off at the elbows; a motorway crash so severe that one victim’s broken spine had come out through the side of his neck.

But nothing could have prepared him for this.

Thankfully, the snow, which had been billowing in through the open door for the last few hours, covered much of the horror, though Manning could still see enough: the iced blood coating every surface, the indescribable mutilation of the corpse. He took it in at a single glance, before turning away to vomit.

Hardaker, for whatever reason, had gone out through the rear door of his lonely cottage. Whoever he’d met out there had then thrown him back in. Possibly, the wind had closed the door behind the old man, but that hadn’t mattered, because whoever had thrown him in, had thrown him clean through it, bursting it from its hinges and bringing down huge chunks of plaster. It wasn’t clear whether the unimaginably savage beating the victim had taken had come before that or after, but old Charlie’s face was a blackened ruin, the bones smashed inward. Both eyes had ruptured, only blood-glutted sockets remaining. More horrifying than any of this, however, was the actual murder weapon.

It was Charlie’s bottom jaw.

The killer had torn it off and bludgeoned the old man to death with it. It now lay beside him, an angled piece of bone clad in crimson shreds of flesh. Three yellowing teeth were still visible in it.

Manning vomited again before he was able to muster the strength to look around outside the property. The moorland encircling it was a white wilderness, snow whistling across it in spiteful flurries. There was no trace of footprints. Manning doubted that even tracker dogs would make headway in this. He took shelter by the gable wall and tried to contact Comms, but his message broke repeatedly. He plodded back to the Range Rover, now buried to the wheel-arches, and tried to use the force radio. Even that gave out only crackles. From what he could gather, some kind of incident was going on in the neighbouring sub-division. Eventually, he re-entered the house, stepped gingerly past the body and tried to use the telephone in the old man’s hall. Inevitably, it was dead.

He stood there, darkness growing around him. Manning had attended many murder scenes before, and the usual feelings assailed him: revulsion at being there – Hardaker’s house was impeccable, but somehow these dens of death always seemed squalid; anger – the futile yearning for revenge against the faceless murderer was often overpowering; and guilt – no cop in the world could attend a murder without thinking that if he or she had been there earlier it might not have happened, that the helpless victim would not have died unprotected and alone, the law unaware they even existed.

Ordinarily, he couldn’t leave the scene, especially as the broken door meant it was impossible to secure, but this time he had no option. It was vital that CID and Forensics arrived before the evidence deteriorated. He also, laughably, needed to certify death, and that would take a doctor. He glanced around the interior of the house before leaving. Only the kitchen showed signs of physical damage. There was no indication that any other part of the building had even been touched, which suggested that robbery wasn’t the motive. That didn’t surprise Manning; he’d already marked this one as the work of a maniac.

It was only as he climbed back into the Range Rover that he thought about the “very tall man”. It was an ugly notion, but he dismissed it. Mawby Hill was over twelve miles away, which in this weather might as well have been a hundred.

However, by the time he was half way down the rough track to Heatherby, something even more worrying had happened. The swathe of snowy moorland to his left appeared to have fractured. A brand new zig-zag line bisected it in an east-west direction. Manning jammed his brakes on, skidding thirty yards and hitting the kerb before he was able to jump out. He stood gaping. Short of an earthquake, there was surely no explanation for this. He was up in the hills, here. As far as he knew, there’d never been colliery excavation on the northern side of the town.

As far as he knew.

When did that ever mean anything? Who was to say there hadn’t at least been tunnelling? Who was to say the town’s foundations weren’t riddled with galleries now in-filling one after another?

Briefly, he was beset by a nightmarish vision of Heatherby itself, the entire town, subsiding, of horrendous casualties, of a thousand people suddenly rendered homeless in the worst possible weather. He leaped into the Range Rover and set off at a reckless pace, snow spurting out to either side. This was getting way too big for the skeleton staff of a sub-divisional nick. He needed help and he needed it fast.

*

The first thing Manning saw as he approached the police station at the top of Heatherby Market Street, was PC Culvin climbing from the cabin of a farm truck. One or two other vehicles were around, all moving in a reckless hurry it seemed to Manning, but the farm vehicle stood out clearly, as always, caked in mud. It pulled slowly away as Manning drove up. Culvin was walking under the arch towards the personnel door when he glanced back. He stopped and waited. Manning had braked and climbed out before he saw that the PC had been hurt. Culvin’s uniform was dishevelled and the fluorescent green anorak he wore over it streaked with blood. He looked pale and clamped a crimson-blotted handkerchief to the side of his head.

“Have a bump?” Manning asked, keying in the access code.

The PC shook his head groggily. “Can’t remember. Was up on Pit Meadow Lane. Bert Longshaw said someone killed his sheep, battered ’em like. Whole flock.”

“What?”

Culvin shook his head again. They entered the locker room, which was dark and empty, though the central heating had been on full blast for so long that it was stultifying. They stripped off their gloves and anorak. Manning hung his hat on a hook.

“I never got there,” Culvin said. “I was half way up, when I went off the road. Bloody weird, I’ll tell you. One minute I was driving, the next my front wheels’d gone down this hole ... you know, like a crack, but straight across the tarmac. I mean right across it. All jagged.”

Manning felt a twitch at the back of his neck. Bert Longshaw’s farm was four miles east of Heatherby. So … first south, then north, now east. “Go on.”

“Like a landslip, it was. Honest sarge, I’ve been up that road fifty times this year, and I’ve never seen that before.”

Manning nodded. “Course ... if you’d been wearing a belt, it might have been less painful for you.” This was an issue they’d discussed at length several times. Manning had discussed it with many junior officers.

“I was wearing a belt.” Culvin touched the gash on the side of his head, where blood was still seeping. “This happened when I got out. Someone lobbed something at me.”

“Come again?”

“Didn’t see ’em, it was snowing that bad. When I came round, I found a piece of granite the size of a breezeblock. Must have used a bleeding ballista …”

Manning could only stare at him. He was thinking of the strength it took to throw a man through a solid wooden door.

“Good job it only glanced me,” Culvin added. “Good job I had my helmet on an’ all. Bert picked me up about ten minutes later. Reckon I’m going to need stitches and a tetanus.”

Manning nodded, but he was still thinking about Charlie Hardaker. “I can’t let you go for them yet, Marty.”

Culvin stood in amazed silence as his sergeant related what had happened. He might have been a lazy sod, but he was basically a conscientious copper. Five minutes later, he’d popped into the first aid room to get an Elastoplast and some antiseptic, and was then off to the garage at the back to check out the supervision car. He’d stand guard at the Hardaker house until someone relieved him, he said.

“And for Christ’s sake, be careful!” Manning shouted after him from the personnel door. “It’s bad news up there. I’ll be up as soon as I’ve got CID.”

Manning walked down the passage to the office, but heard someone shouting inside it before he even went in. It was Gary Parker, the youngest copper at the nick, and the shift’s front desk clerk and custody officer. When Manning entered, Parker was stripped to his shirt and tie, and trying to raise someone on one of the telephones. He glanced up with what could only be described as immense relief.

“Sarge ... thank God. I’ve been trying to get you. There’s an Operation Response!”

Manning halted mid-stride. “What?”

Parker nodded, his young face pale and bewildered. “Yeah. I don’t know the details ... the line went dead. Something’s going on at Halifax. They need every spare body they can get. A riot, or something.”

“In this weather?”

“I only heard a bit of it.”

Manning struggled to make sense of the situation. “Who were you trying to call?”

“Comms. I can’t get ’em on the radio.” The young officer seemed close to panic. “I don’t know what’s going on!”

“Just keep trying,” Manning said.

Parker did, while Manning picked up a different line and dialled Force HQ at Leeds. There was no response. The number didn’t even ring out. Manning stood back. The control he exercised daily in so smooth and professional a fashion that he barely needed to think about it anymore, was slipping away like water through his fingers. He glanced sideways, to where flakes the size of feathers tumbled past the fogged window. Darkness was falling as well. Another vehicle thundered by at what seemed like suicidal speed, swishing through the snow, headlights glaring. This was wrong ... all wrong.

Manning opened the radio cupboard, took out a new pack of recharged batteries and fitted them into his PR. Changing the frequency, he tried to contact the next division. “Sergeant 1768 Manning, Foxtrot Division to Tango control, over.”

A hiss of static erupted from the receiver, then a voice. It was not the clipped, efficient voice of the average radio-operator however, but a falsetto screech. “Urgent message, repeat, urgent message ... officer injured on ...”

With a crackle, it died away. One of the phones began to ring. Manning turned eagerly, but Parker had already grabbed it. “Hello ... West Yorkshire Police at Heatherby. Yeah ... what ... I’m sorry, love, I didn’t ... what do you mean ... no you’ve got to ... Jesus wept!” He slapped the side of the phone, knocked the receiver against the desktop, then turned to his sergeant. “You’re not going to believe this ... some woman’s just said her husband’s been murdered!”

Manning stared at him.

“Line’s gone dead,” Parker added. “Didn’t even get a name and address.”

Only after what seemed like minutes, did Manning manage to get himself together. “What ... what happened?”

“She was screaming herself hoarse, but it sounded something like the back garden. Someone came over the fence and killed him in the back garden ...”

“And we don’t know where?”

Parker shook his head.

“Dial a recall.”

The PC tried, but again slammed the phone down. “It’s dead! Totally dead. They’ve all gone dead. We’re cut off ... Christ!”

“All right!” Manning snapped. “It’s a blizzard, that’s all! Get it together!”

Parker nodded and tried to calm himself down.

“I’m going up to Charlie Hardaker’s place,” Manning said. “He’s been topped too. Hold the fort, if you think you can manage it.”

He snatched a hi-viz slicker from a row of pegs and left by the front desk; but when he reached the steps, he stopped short. The snowbound town had come alive, vehicles screaming past in both directions, their drivers apparently oblivious to the danger. Some were already showing accident damage. As Manning watched, a Ford Escort went into a horrifying skid and crashed headlong into a lamp post, knocking it backward through a shop window and buckling its own bonnet and fender. Even more astonishing, the Escort driver simply threw the car into reverse, backed up and took off again at high speed, kicking up fountains of slush.

The snow continued to cascade. Where it lay, it was banked against walls in drifts that were maybe six or seven feet deep, but it made no difference: pedestrians were out as well, racing back and forth; some weren’t even wearing coats. The deadened air rang with frantic voices. Manning heard a terrific crash, an explosion of wood and metal. It sounded like a house roof caving in, yet he stood there in a daze, barely noticing as someone approached him. Only at the last second did he turn … just as a solid fist smashed into his jaw.

The next thing he knew, he was lying face-down, his mouth full of hot, metallic fluid.

“Useless pigs!” someone hissed in his ear. A steel-toed boot whumped into his ribs. “Where’s your Orgreave army now when we need it?” The man kicked him again, before lumbering away.

It was several minutes before Manning had come round sufficiently to sit up, ten minutes before he could stand. He suspected his jaw was broken, but knew he didn’t have time to worry about it. He tottered groggily to the Range Rover and climbed inside.

Driving was a nightmare, the blizzard reducing pedestrians to vague phantoms in the murk, obscuring vehicles down to their headlamps. If it was possible, the temperature had dropped even further. The roads were rivers of ice and Manning had several minor collisions before getting out of the town centre. Ordinarily, each one would have meant a written report and probably disciplinary action. Now, he didn’t give them a second thought; he only had one interest, to get up the mountainside.

But it was too late.

He was only halfway to Charlie Hardaker’s house, when he saw the wrecked police vehicle in his headlights. It was lying on its roof, its windows shattered. Black pools of oil were visible around it.

Manning leaped out, torch in hand, and approached. The wind whipped the snowflakes at him like stinging wasps. He ignored it, circling the crashed supervision car. There was no movement from inside, only darkness. Any tell-tale tracks had already been buried.

He halted, peering around, at which point the ground began to shake.

At first, it was a rumble under his feet. He lurched backward, alarmed.

The wrecked shell of the supervision car rattled violently, and from beneath it came another fissure. Initially it was visible only as a deepening groove in the snow, but it made rapid progress, and when the snow fell into it Manning saw a deep, widening split in the road surface. It lengthened speedily, scurrying away towards the Range Rover. He bolted for the vehicle, jumped in and slammed it into reverse …

And a torn-off human head landed on the bonnet.

The first Manning knew there was a thump of metal, and then a waxy white face under a mop of blood-sodden hair was screaming silently through the windscreen. In that first second Manning didn’t recognise it; the eyes had popped out, the mouth gaped wider than was humanly possible. Then he saw the Elastoplast still fastened over the wounded temple.

“Culvin!” Manning shrieked, jamming his foot down.

The head toppled, showing a jagged stump of smoking red meat. A film of blood sprayed over the windscreen, the wipers smearing it in a livid slick. Manning reversed like a madman, the wheels losing their grip repeatedly, the vehicle careering sideways. Still that face of lunacy gaped at him through the crimson fog. Manning looked back through his rear window but saw nothing for the cake of frost. It didn’t matter. He revved harder and harder, the car, borne by its own weight and velocity, turning sideways on the double-glazed surface. Manning fought the wheel, shouting, his lips flecked with froth. He saw himself going over some precipitous edge, turning end on end, beating his cranium to sponge on the roof, engine flames searing his flesh to parchment long before the all-engulfing anaesthesia of death.

But there was no edge. There were no flames. There was only the maelstrom of snow and darkness, the treacherous road of ice, the smashed and laughing face, now pressed against the glass by G-force, imprinting its visage in gore. And something else: the figure pursuing the car down the road. Or rather … the figures.

The Range Rover turned like a top, spinning madly, bouncing kerb to kerb, the world passing it by in a blurry kaleidoscope. But with each revolution, Manning caught flickered glimpses of grey, cyclopean figures bounding down onto the road, pursuing his vehicle like maddened apes, or elephants, or rhinoceroses, or all three merged into some fevered biological blasphemy.

What could throw a man clean through a wooden door?

The ground thundered, or was that the wind, or the constant clash of bodywork on rock and kerb, or Manning’s faltering heart beating a tattoo of terror beyond imagining.

Fleetingly, the empty downward road appeared before him, and he tromped the gas. In his crazed eagerness, he almost overshot, but he righted at the last second, a wall of sparks blazing along the Range Rover’s offside as he blasted down the high verge, hubcaps shearing off like bottle-tops, and then he was moving freely, only the beautiful empty darkness in front. And the crusty gauze of blood, of course. And Culvin’s head, somehow moored to the bonnet, wagging from side to side as though in disapproval. Manning hit his brakes to try and dislodge it, skidding uncontrollably, though at the next bend it flew into the night of its own accord. It couldn’t have done so more impressively had it sprouted bat wings.

Manning righted the wheel as he precipitated forward. His teeth chattered so savagely that he couldn’t utter a prayer of thanks. He couldn’t even check the mirror to see if those fucking hallucinations were still following him. None of that mattered. Escape was all. Escape from this Roller Coaster road. From this cursed town. From this nightmare. And then he remembered Geraldine. At home all day. On her own.

Manning righted the wheel as he precipitated forward. His teeth chattered so savagely that he couldn’t utter a prayer of thanks. He couldn’t even check the mirror to see if those fucking hallucinations were still following him. None of that mattered. Escape was all. Escape from this Roller Coaster road. From this cursed town. From this nightmare. And then he remembered Geraldine. At home all day. On her own. A moan tore from his lips.

He floored the accelerator with everything he had.

*

The Mannings lived at the end of a cul-de-sac on the southern outskirts of Heatherby. Aside from the various new housing estates being constructed atop the south bank of the M62 motorway, theirs was the last district of habitation. Nothing much happened there. The neighbours liked each other. The children were civil. There was no possible danger. Apart from the fact the entire estate was built on a wide plateau long ago reclaimed from a Coal Board slag heap. Steep slopes fell away on three sides of it.

And now they were literally falling away.

As Manning’s Range Rover skidded down the road towards his front door, he saw a gigantic fissure wriggling across the ice at the far end, saw pavement flags upending in the snow, heard the staccato crackle of rocks and boulders as they snapped like rotten bones. When, with an ear-splitting roar, the farthest house vanished from view, toppling backward into a void, it was four doors from his own.

Manning hit the brakes so hard he almost turned the car on its side. Somewhere ahead, a telephone pole came down, cables lashing and sparking like electric eels. There was another explosion of timber and the next house began to slide, its roof lopsiding, windows bursting outward. Was anyone inside it? Was anyone in the street even? Manning didn’t care so long as he found Geraldine. The road juddered beneath his feet as he ran up his drive to the front door. As it opened, cracks spider-webbed over the lintel.

“Geraldine!” he bellowed.

His wife waited in the lounge, white-faced, eyes glazed. She already wore a coat and had a bag in her hand. The television was on, but the screen was a haze of static. Vague figures moved ponderously about in it, someone was screaming. An American newscaster said something about “international calamity”. Manning didn’t care. He wasn’t listening. He took his wife by the hand and dragged her out of the house. As he did, the floor began to tilt. Boards sprang under the carpet. The burglar alarm went off.

Snowflakes danced into their eyes as they blundered towards the car. As they climbed in, Manning saw a branch-line of the fissure working its way along the centre of the street towards him. He turned the vehicle around and sped away with seconds to spare. In the wing mirror, his house distorted as it fell backward out of view. A split-second later, the fissure widened and with the cacophony of an earthquake, the entire southern side of the cul-de-sac slid away, paving, front gardens, houses, cars, all vanishing.

And then he saw something else. Just before he spun around the next corner, the copper glanced down alongside his vehicle and saw something that he simply refused to believe. Something vaguely humanoid deep down in the cleft, its back braced against one rock face, its massive feet planted on the other, its legs bent double, thighs bulging with granite muscles as it strained and heaved and pushed.

Manning tried to blot it from his mind as he drove for the M62. Everyone else had had the same idea, however. The slip-roads were chocka with vehicles packed with frightened people and travelling at furious speeds. Collisions were frequent, skids a constant hazard. Screams and curses echoed over the yowling engines, but no one stopped to swap addresses or demand restitution. No one dared. Behind them, spread in vast panorama, were the twinkling lights of Heatherby. Many of those lights now winked out, in their place the spreading crimson glare of house and shop fires, massive, lumpy figures moving among them.

“It’s the end of everything,” Geraldine said in shaking monotone.

“Don’t talk wet!” Manning spat, but he had trouble getting the words out. “Just ... just a landslide or something. You know ... an earthquake. Pits ... pits have caved in.”

They sped down the access ramp past the first of the new housing estates, onto the yellow-lit motorway, where true Pandemonium reigned. The M62 was a troubled route at the best of times, but now had to be seen to be believed. The traffic was moving, but it was solid as a log-jam, vans and trucks crammed in with the cars, many running five or six abreast, some on the hard shoulder. An unending dissonance of horns and engines raged through the frozen air. That was the west-bound carriageway. Incredibly, east-bound the lanes were deserted. Though maybe that wasn’t so incredible, Manning thought. Because if you went east on the M62, you also went north, into the teeth of the storm ... and whatever it had brought with it.

He pushed his way out onto the crowded motorway, only to be buffeted repeatedly.

“I don’t know where they’re running to,” Geraldine muttered. “There’s no escape ...”

“For Christ’s sake!”

“It’s the Fimbulwinter. It’s happened like the legend said. And now they’ve come back. To reap the discord and reclaim the world.”

She sounded as if she was quoting something, but Manning was too distracted to wonder what. He swore loudly as they crashed into a car in front and then were jolted from behind. Amazingly, the log-jam continued to move, totalled vehicles dragged along with the rest. “What … what’re you gibbering about?” he shouted.

“What I say,” she said. “Them. The giants.”

Manning wanted to slap her and shout at her, tell her that the last thing he needed now was for his wife to go crazy on him. But he’d already seen things that day that defied explanation. That surely couldn’t exist in the world of law, order and science, where up until this morning he had spent his entire life.

That was when the first missile hit the car.

Initially they thought it another collision. Then the second missile struck, crashing over the bonnet with terrific violence. Geraldine screamed. Manning swore.

A house-brick. A full-sized house-brick flung from the embankment like a tennis ball. Two others hit home in quick succession, sending shockwaves through the chassis. By now, missiles were striking other vehicles too, raining down all along the motorway, smashing on roofs and bonnets. As far as the eye could see, snowflakes billowed in the yellow glare of the street-lights, but showers of a more terrible sort were falling with them. Projected from the embankment.

Only then did it dawn on Manning what was happening.

This was an attack. A full-scale, preplanned attack.

An army had emerged from the tempest and overrun him and his people in their own encampment. Then it had herded them down into this narrow gully where their vast numbers were a disadvantage. That army was now deployed alongside, hidden by the driving snow and thanks to those miles and miles of half-built houses on the new estates, provided with stockpiles of ammunition.

He got his foot down hard, but only succeeded in shunting the Jaguar in front. It scarcely mattered, for one second later the black blur of a twirling brick swooped on the Jaguar’s windscreen, staving it in like paper. The Jag went wildly out of control, skidding sideways and flipping onto its side. Manning swerved around it as it exploded. In his rearview mirror, orange flames mushroomed into the air, but still the missiles came down, thrown with horrendous force by the unseen foe, sleeting into the sea of headlights, shattering windows, gashing bodywork. It was the same directly ahead. Bricks, stones, breeze-blocks, girders even, bounced from the roofs and flanks of the sliding cars. Sparks flashed from repeated impacts. There were further detonations, plumes of flame and smoke. Dams of crumpled metal appeared as vehicles, filled only with the dead and battered, careered into one another, tangling wheels and bumpers, losing speed, slithering upside-down. In many places, people were getting out and trying to run, though swarms of missiles felled them. Either that, or other cars cut them down. Broken bodies flew ragged in the air, or rolled in the gutters between grinding, slewing wheels. The stink of petrol was everywhere, the screams and shouts deafening. Manning screamed along with them. He’d long forgotten that he was a policeman. He forced Geraldine down into the foot-space, then ducked himself as a doorstep-sized chunk of brick and ice came glittering at his windshield. By a miracle, the glass held, though it frosted with cracks. He drove on regardless, hitting and knocking things, keeping as low as he could, cringing with every shuddering blow.

A piece of paving stone skittered across his roof, slamming through the front passenger window of an Audi on his right, crushing the skull of whoever was sitting there, spraying the inside of its windscreen scarlet. Even in his dazed condition, Manning heard a male voice going hysterical, the driver maybe, and the howls of what sounded like children from the back. Then the Audi front-ended the rear of a stationary HGV, and fragmented with the force of its erupting fuel tank.

Manning stomped his pedal to the floor to escape the blast, unable to look at the writhing, blazing figures in his rear-view mirror, only to run aground himself, bullocked sideways by an out-of-control van. Another vehicle hit him, this time from behind, spinning him. A second later the Range Rover was stationary, hemmed between smoking wrecks, the icy air seeping into it. Then the driver’s window imploded, and what felt like a fist in a mailed glove hammered into Manning’s cheek. His head flew to one side, and he heard Geraldine crying out and grabbing at him.

“I’m ... I’m all right,” he stammered, his thoughts swimming. A bloodied half-brick lay in his lap.

“Oh my God, George,” she gasped. “You’re bleeding.”

“I’m all right!” he insisted again, though he knew that he wasn’t. Loose bones ticked in the side of his face. Half of his head had gone numb. Fighting off unconsciousness, he kicked open his door and clambered out. “We’ve got ... got to get out of here.

But in both directions now, the motorway was jammed up with burning, twisted vehicles, many skew-whiff or on their sides. Hapless figures milled among the smouldering hulks, climbing over them, or lying trapped, shrieking for help. Close by, a businessman, still in his pin-striped suit but with a cut forehead and broken glasses, was trying to drag a sports bag from the boot of his Bentley.

“For Christ’s sake!” he shouted hysterically. “It’s my life’s savings ... for Christ’s sake, someone help me!”

His bag was trapped, however. Haul as he may, he couldn’t shift it. He was about to shout again when a brick impacted in his open mouth. It sounded like a hammer hitting a pumpkin. His arms flopped bonelessly as he sank to the ground, his head a pulverised mass of brick and bone. Then a missile struck Manning’s shoulder. He went down with a gasp, falling over a mangled car bonnet. He knew instantly that his shoulder was broken. The pain was nauseating.

Black moments passed before he realised that Geraldine was tugging at him. In a daze, he levered himself up and walked. Like a stumbling, drunken man, he allowed his wife to lead him across the motorway, threading through the debris. Behind them, voices still moaned and wept, the deluge of missiles still beat a thunderous tattoo on chrome and concrete. When they reached the north side of the motorway, the unbroken snow on the embankment was too deep for them to make any headway. It was several feet in places, and as they ploughed into it, simply swallowed them to the waist. Sapped of strength, it became a futile battle. They attempted to struggle up anyway, the slope rearing above them like the south face of Everest. Manning, one side of his body leaden and useless, leaking blood by the pint from his slashed-open face, was the first of the two to collapse. He toppled forward, half-burying himself. Compared to the ice-edged wind, the enveloping snow was warm as a blanket.

Slowly and awkwardly, he rolled onto his back, gradually becoming aware of Geraldine hunched down beside him. Somewhere below, the streetlamps winked off post by post. Darkness spread, only islands of flame holding it at bay. The crashing and banging endured with renewed intensity, for tall shadows were now slinking down from the snows, carrying cudgels. Where the rain of bricks ceased, the slamming of clubs – scaffolding pipes, football goalposts, the stems of traffic lights – commenced.

Manning wasn’t interested. He wasn’t cold any more. He couldn’t even feel his broken shoulder. He sensed Geraldine lying down with her head on his chest, her thin, shivering form coating over with flakes.

“How ... many of them, I wonder?” he stammered. “How many rocks in the earth?” she replied.

If Manning could have nodded, he would. “Better ... this way, then.”

“Better this way,” she said.

A quick reminder that, if you enjoyed this story today, there are more Christmas and winter-time ghost and horror stories available in my two collections: THE CHRISTMAS YOU DESERVE and IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER .

(PS: None of the ARTWORK used in today’s blog was commissioned for this story. All of it I found floating around online with no names attached. If any of the creators want to get in touch with me, I will happily add their credits to this post. Or, if they’d rather, I can always take the images down).

December 6, 2020

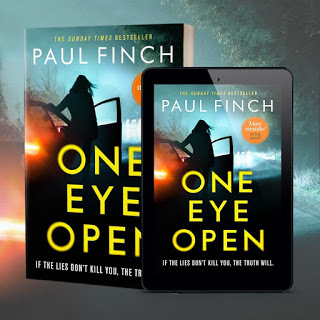

Darker crimes to chill you this Christmas

Well, we’re finally into December, so we can at last start talking all things Christmas again. Not that I haven’t been doing this already, I freely admit. But it occurred to me the other day that there is plenty of Christmas stuff to be discussed where my main novel of 2020, ONE EYE OPEN, is concerned (even though it was published during the summer). It’s set over Christmas after all, and packed with midwinter predicaments.

You’ll hopefully recall that it was a hardcase crime thriller, and in keeping with that dark and dangerous tone, I’ll also today be reviewing the rather excellent THE DARK INSIDE by Rod Reynolds, the fictionalisation of a very dramatic real-life murder case, which makes for a superb suspense novel.

If you’re only here for the Rod Reynolds review, I’ve got no problem with that. Just zoom on down to the lower end of today’s post, and you’ll find it, as always, in the Thrillers, Chillers section. If, on the other hand, you’ve got a bit more time, we can first chat a little about …

A Christmas caper

ONE EYE OPEN, my first crime novel for Orion, was published last August, and while the average man on the street might assume this meant it was going to be a summer read (and I wouldn’t argue with that as I consider it a real page-flipper), it is set during a deep-frozen Christmas and so ought to be a damn good read for the festive season too.

The story itself takes place between mid-December and early January, the centrepiece of it a well-planned but brutal armed robbery, which occurs on Christmas Eve itself. It all happens in the Essex and Suffolk countryside, a part of Britain perhaps not renowned for its plunges into Arctic weather, though this is exactly what occurs on this occasion, and it focusses not on some ace detective or specialist Major Investigation unit, but on a Traffic officer, Lynda Hagen, who, as well as having various lesser enquiries to put to bed, must also look after her demanding family during the Christmas season and take care of her husband, who’s still not fully recovered from a nervous breakdown.

The story itself takes place between mid-December and early January, the centrepiece of it a well-planned but brutal armed robbery, which occurs on Christmas Eve itself. It all happens in the Essex and Suffolk countryside, a part of Britain perhaps not renowned for its plunges into Arctic weather, though this is exactly what occurs on this occasion, and it focusses not on some ace detective or specialist Major Investigation unit, but on a Traffic officer, Lynda Hagen, who, as well as having various lesser enquiries to put to bed, must also look after her demanding family during the Christmas season and take care of her husband, who’s still not fully recovered from a nervous breakdown. The last thing she really needs, of course, is to be dragged into the world of organised crime, multi-million pound heists and gangland shootings.

I’m not going to say any more about ONE EYE OPEN, but will add that, at the time of this writing, it has over 500 glowing reviews on Amazon (but is still there, waiting for more

November 22, 2020

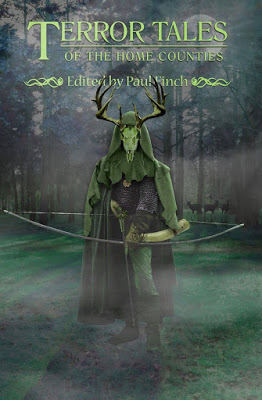

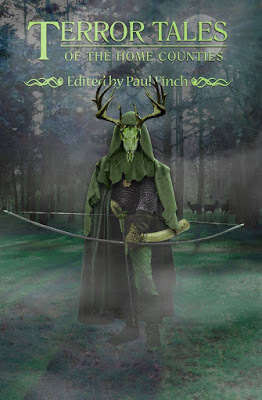

Where lies the future for TERROR TALES?

Today, I’ll be asking the question what does the future hold for my TERROR TALES series? Now, before some smart Alec says ‘you need to ask your publisher, surely?’, I’m talking purely in the aesthetic sense.

Yes, whatever happens with the TERROR TALES series, however long it’s destined to last in its current format, will be entirely down to TELOS PUBLISHING, who’ve done such an amazing job with the last three volumes. The last one in particular, TERROR TALES OF THE HOME COUNTIES, seems to be attracting huge interest online.

But what I’m pondering today is where to go with the substance of the series. Those who follow it will have realised that we are now past halfway in our round-tour of mainland Britain. Okay, we’re not going to complete it in the next year or so. There are still plenty of places to visit here in Blighty. But it will happen eventually, so where do we take TERROR TALES after that?

I have rafts of ideas, but there are lots of issues to talk about.

In addition today, and it’s very in keeping with the main theme, because this is one author whose stories have featured regularly in TERROR TALES, I’ll be reviewing THE BALLET OF DR CALIGARI, Reggie Oliver’s seventh collection of horror stories under the Tartarus Press banner.

For those who don’t know him, Reggie Oliver has often been referred to as the best kept secret in British horror and as the heir-apparent to both MR James (left) and Robert Aickman ... imagine that combination, if you can. He’s also known worldwide for his endlessly inventive scenarios and for the eloquence of his nightmarish prose.

For those who don’t know him, Reggie Oliver has often been referred to as the best kept secret in British horror and as the heir-apparent to both MR James (left) and Robert Aickman ... imagine that combination, if you can. He’s also known worldwide for his endlessly inventive scenarios and for the eloquence of his nightmarish prose. If you’re only here for that review, you can find it at the bottom of today’s blog, as usual, in the Thrillers, Chillers section.

If that’s your main interest today, shoot on down there straight away. However, those with a little more time on their hands, may also be interested in …

Terror Tales from everywhere

I don’t want to get repetitive on you and go again through the whole story behind my TERROR TALES series (in which we’ve so far published twelve titles). Suffice to say that it was inspired by the Fontana Tales of Terror series of the 1970s, which was mostly helmed by Ron Chetwynd-Hayes, and which selected one specific region per volume and would then tell horror stories about it, snippets of true terror interspersing with great works of fiction, some of these old and well-known, others brand new but commissioned from some of the best authors around.

I’ve adopted exactly the same format with the TERROR TALESseries, though whereas Fontana had broader targets:

Welsh Tales of Terror

,

Irish Tales of Terror

,

Scottish Tales of Terror

for example, we’ve narrowed things done a little. Yes, we too have done

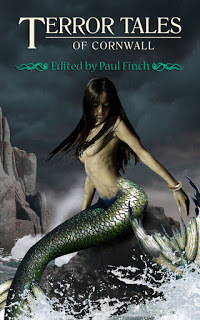

TERROR TALES OF WALES

and

CORNWALL

, as Fontana did, but we started with

TERROR TALES OF THE LAKE DISTRICT

, and went on to do

TERROR TALES OF THE COTSWOLDS

,

EAST ANGLIA

,

LONDON

,

YORKSHIRE

etc etc.

I’ve adopted exactly the same format with the TERROR TALESseries, though whereas Fontana had broader targets:

Welsh Tales of Terror

,

Irish Tales of Terror

,

Scottish Tales of Terror

for example, we’ve narrowed things done a little. Yes, we too have done

TERROR TALES OF WALES

and

CORNWALL

, as Fontana did, but we started with

TERROR TALES OF THE LAKE DISTRICT

, and went on to do

TERROR TALES OF THE COTSWOLDS

,

EAST ANGLIA

,

LONDON

,

YORKSHIRE

etc etc. The big question now, having covered roughly half of the mainland UK, is where do we go once we’ve finished with this little island?

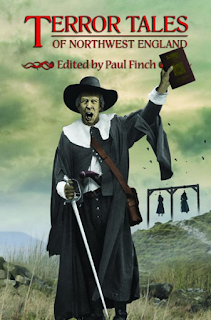

Well, before that, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that I’ve got firm plans for the immediate future. For example, to compliment

TERROR TALES OF THE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS

, we simply must, at some point, publish TERROR TALES OF THE SCOTTISH LOWLANDS. Other British districts that we must go to include THE WEST COUNTRY, THE ENGLISH MIDLANDS, and to balance out

TERROR TALES OF NOTHWEST ENGLAND

, there has to be a TERROR TALES OF NORTHEAST ENGLAND.

Well, before that, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that I’ve got firm plans for the immediate future. For example, to compliment

TERROR TALES OF THE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS

, we simply must, at some point, publish TERROR TALES OF THE SCOTTISH LOWLANDS. Other British districts that we must go to include THE WEST COUNTRY, THE ENGLISH MIDLANDS, and to balance out

TERROR TALES OF NOTHWEST ENGLAND

, there has to be a TERROR TALES OF NORTHEAST ENGLAND. At the other end of the country, meanwhile, THE SOUTH COAST would also be worth a book.

By the way, the reason behind these relatively small target areas is quite simple. Having extensively researched the folklore and mythology that provides the factual palate-cleansers located between the works of fiction in these anthologies, I’ve uncovered vast amounts of scary material, chilling tales purporting to be true and located in all these different regions of the country. It would have been a crying shame to throw much of it away simply because we were taking too large a scope and therefore couldn’t fit it in.

But still we get back to that nagging question: where do we go when mainland Britain is done?

Terror overseas

I’ve never worked on the basis that the writers who produce fiction for these books need to be ‘ethnically correct’ for the region under examination, but I’ve always been insistent that each story must be relevant to that region. However, once you’ve gone overseas, the ethics of this approach become murkier. I’d certainly like to do TERROR TALES OF IRELAND (again, as Fontana did back in the day). I pride myself on knowing plenty of Irish writers. On top of that, Britain and Ireland enjoy a close friendship these days, with much cultural exchange. I strongly doubt that anyone would object if there were one or two British (or American authors) in there as well … so it really wouldn’t be a problem putting this one together.

I’d certainly like to do TERROR TALES OF IRELAND (again, as Fontana did back in the day). I pride myself on knowing plenty of Irish writers. On top of that, Britain and Ireland enjoy a close friendship these days, with much cultural exchange. I strongly doubt that anyone would object if there were one or two British (or American authors) in there as well … so it really wouldn’t be a problem putting this one together. But then, when we go further afield into Europe, it might become more of an issue. I have optimistic plans to take the TERROR TALESseries around the European continent, from the MEDITERRANEAN to SCANDINAVIA, from WESTERN EUROPE to EASTERN EUROPE. I reckon those are four potentially delightful books that I wish I could start editing right now. But the problem is that I don’t know many authors from the countries we would cover. In fact, in most cases, none at all.

I’ve no doubt that I could safely commission a whole bunch of superb fictional horror stories set in all of these lands, but they would be by English-speaking authors, and even though said Brits might know these places inside out, would that be the correct thing to do?

I’d genuinely value opinions on this.

Personally, I’d be inclined to say ‘yes it would’ given that the only other alternative would be not doing these books at all.

However, once you’ve cleared that hurdle, and are looking to take the series even further afield, other complexities arise.

The Americas, you might think, would be the obvious next place for the series to pitch up, North America in particular: it’s primarily English-speaking, plus I know many writers from the US and Canada.

The Americas, you might think, would be the obvious next place for the series to pitch up, North America in particular: it’s primarily English-speaking, plus I know many writers from the US and Canada. What a laugh we’d have with that. Imagine it: TERROR TALES OF THE DEEP SOUTH, TERROR TALES OF THE GREAT PLAINS, TERROR TALES OF NEW YORK, TERROR TALES OF THE WHITE NORTH etc etc etc.

Except that how could I, an Englishman, who has only ever visited the North American continent twice in his entire life, possibly have the temerity to set myself up as editor for an American folklore-based anthology? Surely, it would have to be another American? I mean, don’t get me wrong … I would love to have a go, but I would only attempt this with the tacit permission of the American horror fiction community.

Consider this, and then imagine the even more immense problems if I was to try my hand at editing

Consider this, and then imagine the even more immense problems if I was to try my hand at editing TERROR TALES OF CENTRAL AMERICA or TERROR TALES OF SOUTH AMERICA.

Both those regions have wonderful literary traditions, and again, strong horror-writing communities … but alas, I’d be a total stranger in their eyes (and largely ignorant of their expertise).

The same issues would apply to TERROR TALES OF THE CARIBBEAN, TERROR TALES OF THE MIDDLE EAST or TERROR TALES OF THE FAR EAST. In the latter case, when JJ Strating edited Fontana’s Oriental Tales of Terror back in 1971, at least half the stories were provided by authors of Oriental origin or western writers who were living there. I wouldn’t have the contacts or knowledge to even commence compiling an anthology of that sort.

A better option might be, once we have covered Britain and Europe, to move out of the realm of specifics.

So, for example, TERROR TALES OF THE TROPICS would sit very nicely alongside TERROR TALES OF THE TUNDRA. I couldn’t see that there’d be much controversy there.

So, for example, TERROR TALES OF THE TROPICS would sit very nicely alongside TERROR TALES OF THE TUNDRA. I couldn’t see that there’d be much controversy there.

TERROR TALES OF OUTER SPACE has to be done at some point, if for no other reason than to honour Fontana’s Tales of Terror from Outer Space (I’ve already done TERROR TALES OF THE OCEAN and TERROR TALES OF THE SEASIDE in tribute to Fontana’s original Sea Tales of Terror ).

Beyond that, we could move onto society itself. How about TERROR TALES OF THE INNER CITY, TERROR TALES OF THE SUBURBS, TERROR TALES OF THE COUNTRYSIDE and TERROR TALES OF THE WILDERNESS …?

We could even start looking at the calendar. TERROR TALES OF CHRISTMAS would be an obvious one. Likewise, TERROR TALES OF

TERROR TALES OF CHRISTMAS would be an obvious one. Likewise, TERROR TALES OF HALLOWEEN. But what about TERROR TALES OF SPRING, TERROR TALES OF SUMMER, AUTUMN, WINTER … ? I know what you’re thinking. At the rate we produce these books, which is roughly one a year, we’d all be pushing Zimmer frames before we got even half way through a list like this. But should that stop us trying?

Perhaps our final pursuit, after all this, as the series gradually winds its way towards a stately and inevitable end, is horror culture itself.

These titles would round it all off nicely: TERROR TALES OF THE OCCULT, TERROR TALES OF THE SUPERNATURAL, TERROR TALES OF MONSTERS, TERROR TALES OF FOLKLORE, and finishing it all off maybe, TERROR TALES OF MANIACS.

These titles would round it all off nicely: TERROR TALES OF THE OCCULT, TERROR TALES OF THE SUPERNATURAL, TERROR TALES OF MONSTERS, TERROR TALES OF FOLKLORE, and finishing it all off maybe, TERROR TALES OF MANIACS. Please forgive me for thinking aloud today. That’s often all I do on this blog, if I’m honest. Though I make no apology for dreaming these dreams.

Maybe we’ve been a little bit ambitious, but if anyone has any better ideas, feel free to let me know. You can rest assured, any that are really good will be freely pinched.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE BALLET OF DR CALIGARI

THE BALLET OF DR CALIGARI

by Reggie Oliver (2018)

Reggie Oliver is one of the most readable and elegant purveyors of supernatural fiction working today, and yet his reputation in that field continues to elude many out there in the wider world. This is a minor tragedy in my view because, on merit alone, Oliver deserves to be a household name. At least he is well-recognised within the genre itself, a cause served admirably by Tartarus Press, who to date have brought out seven collections of his stories.

The Ballet of Dr Caligari is the most recent on the list, but is something of an oddity in that it incorporates the best of Madder Mysteries, a much earlier Oliver collection, put out in 2009 in fact but which for various reasons was read by almost nobody. The opportunity to get hold of older material that almost sank without trace through no fault of the author gives added value to this particular collection, of course, though there are many more recent stories in here as well, these congregated in the second half of the book, which makes for a most satisfying whole.

When Reggie Oliver first burst onto the ghost story scene in the early 2000s, he was viewed by many as the heir to MR James, his preferred subject the traditional English supernatural tale though with more than a hint of danger in it. Since then, however, and this is excellently illustrated in The Ballet of Dr Caligari, his style has moved more towards the realms of Arthur Machen and Robert Aickman in that he favours strangeness over the straightforwardly ghostly. And yet Oliver’s work is just as frightening now as it ever was, even if he does tend to tackle slightly more complex subject-matter.

Things that have never changed, however, include his eloquent writing style, his scholarly tone, his mordant wit, his effortless evocation of different times and places and his skilled creation of sad, lost characters, all of it coming neatly packaged in deceptively gentle prose.

Another trademark of Oliver’s are his regular trips down memory lane where his own theatrical career was concerned. Oliver was a successful actor, theatre director, playwright and biographer before he moved into a darker literary world, his supernatural canon subsequently making many visits to Britain’s provincial theatre-land of former decades, the majority of these stories steeped in melancholy, though not always because the author is bemoaning the loss of something wonderful. Oliver never skimps on detail when it comes to the tawdriness of some of the experiences he had back then, be it damp dressing rooms, dingy backstage corridors, unpleasant and even predatory fellow professionals, or maybe just second rate accommodation in seaside towns that time forgot.

The Final Stage is a perfect example in this particular collection. It sees an arrogant young actor injured during rehearsal, knocked unconscious and plunged into a theatrical hell of his own making. Another powerful tale of this ilk, less disturbing but dark and foggy nonetheless, is The Vampyre Trap, an atmospheric murder mystery set in Bradford’s Victorian era theatre district, complete with ghosts, arson and multiple deaths by strychnine poisoning. Though by far the most intriguing and yet repellent study of theatre life in times gone by is Baskerville’s Midgets. Read in the age of diversity, it walks the line somewhat, but like many of these stories, it comes to us from another era, when sensibilities were significantly different. I consider this one quite a special piece as low-key horror stories go, so more about this one later.

Reggie Oliver could never really be regarded as an experimental author, but there are three particular stories in The Ballet of Dr Caligari that are fascinatingly off-the-wall compared to his normal output. The first of these, Tawny, you probably would have to classify as experimental fiction, because the story is told entirely in dialogue between characters who are never formally introduced. Such is Oliver’s skill, however, that this never becomes a problem. It concerns an upper class christening, which is interrupted by the arrival of a huge, shaggy animal, which might be a local farm dog gone astray, or something much more sinister.

The two other stories in the trio, while not what I’d regard as experimental, certainly belong in the school of weird fiction rather than the overtly supernatural, though both are deeply macabre. Probably the more lauded of the two, and probably the most Aickmanesque tale in the whole of this collection, if not the most Aickmanesque tale that Oliver has ever written, is A Donkey at the Mysteries, which tells the story of an adventurous undergraduate who makes a one-man tour of Ancient Greek sites, only to arrive on the island of Thrakonisos, where his investigation of the mysterious Sanctuary of the Great Gods invokes an ancient and malignant power. The third story in this small group, The Head, is equally difficult to categorise, but no less unnerving and no less morbidly chilling. In this one, an eccentric art-dealer receives a terminal diagnosis, and so plans to commit suicide with the assistance of an amoral young taxi driver he takes a fancy to, though it won’t be as easy as either of them expects.

Oliver aficionados may consider that more familiar territory is to be found in Love and Death. In this one we’re firmly back in the world of the recognisably supernatural, but it’s a slower burn than usual, and laced with academic interest. It takes place in Victorian London, where it sees Martin Isaacs, an unsuccessful artist, commissioned to recover a missing work of genius, Love and Death, as painted by Basil Hallward, his former mentor, who has now mysteriously disappeared. But the painting, a classical image in the Renaissance style, is misleadingly beautiful. In reality, it destroys all that it touches. A similar tone is struck by Lady With a Rose, in which a young British artist sets up shop in Rome of the 1960s, where he struggles to make a living until he is summoned to the grand home of Prince Valerio Grandoni, who has an unusual and potentially very dangerous commission for him.

Both of these arts-themed tales are intriguing rather than out-and-out frightening, but they hint at extreme darkness and will keep you glued to the page.

Possibly the dreamiest (and perhaps most meaningful) story in the book, and certainly the most folk-horrorish (if such a word exists), is Porson’s Piece, another deceptively gentle fable. It centres on Jane, an Oxford scholar, who seeks an interview with Bernard Wilkes, a former professor of philosophy now in his 80s. She finds him living in a quaint Cotswolds village, but though he’s still an avowed atheist, he now lives in fear of a nearby strip of land called Porson’s Piece, on which the dead are said to dance.

Of course, no Reggie Oliver collection would ever be worthy of the name if it didn’t contain at least a bunch of Gothic horror stories penned with the sole intention of instilling terror in the reader. This, for me, is where the great man really excels, and The Ballet of Dr Caligari is no exception.

First up is The Game of Bear, co-written with MR James himself, though obviously Oliver added his bit long after Dr James had died, the story at that point incomplete.

It centres on Henry Pardue, fortunate heir to a vast country estate, though endless problems are caused for him by his cousin, Caroline, who feels that with her own small inheritance, she has been ill-treated. When Caroline dies, Pardue hopes the matter is over, but it isn’t … as he will learn for himself that following Christmas Day, during the infamous Game of Bear.

Three other tales, owing purely to the imagination of Reggie Oliver, are worthy to stand alongside this one in terms of how genuinely hair-raising they become: The Devil’s Funeral, which I seriously believe is one of the best and eeriest horror stories of modern times, even though it’s set in a distinctly Jamesian past; The Endless Corridor, an uber-Gothic terror tale reminiscent of the great horror writers of earlier eras, Poe, Shelley, Stevenson and so on; and the titular story, The Ballet of Dr Caligari, a phenomenal piece of dark fiction, which though it draws heavily on the original classic tale, is possibly even more crammed with madness and obsession and certainly no less chilling.

I’ve not even hinted at the synopses behind these three final stories simply because I’ll deal with those in the next section. In the meantime, all fans of short eerie fiction should get hold of The Ballet of Dr Caligari. It’s a mixed bag for sure, but the writing is of the highest quality (as are the illustrations, which are provided by the author himself), and it amply demonstrates what a fine and versatile writer Reggie Oliver is.

And now …

THE BALLET OF DR CALIGARI – the movie.

Okay, no film maker has optioned this book yet (as far as I’m aware). So as always, part of this review will involve me non-too-seriously casting this beast before someone with enough development money comes along and does it for real. Here are my thoughts.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual circumstances that require them to relate spooky stories.

It could be that they are trapped in a cellar by a broken lift and are awaiting rescue (a la Vault of

It could be that they are trapped in a cellar by a broken lift and are awaiting rescue (a la Vault of Horror), or maybe they find themselves in an idyllic country home, where a nervous renovator needs reassurance about his various nightmares (al la Dead of Night).

Without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

(It may look like I’ve spent a fortune on these actors, but remember, for portmanteau horrors they only usually have to work for one day each

November 1, 2020

ILL MET BY DARKNESS - coming your way

I’ve got a little surprise today. Hopefully, readers of this column will consider it a pleasant one. It’s an imminent new publication of mine, which I haven’t mentioned at all until this moment, and which, with any luck, will fit in nicely with everyone’s reading habits as we enter this dark and ghostly time of year. It’s being published by the inexhaustible SAROB PRESS, and is called ILL MET BY DARKNESS. It will only be available as a hardback limited edition and contains four completely new horror novellas of mine, all of which have a distinctly folklorish vibe.

Even if I say so myself, I’ve been busy during this pandemic. Very, very busy in fact. But I’m reasonably optimistic (and praying) that you’ll consider this effort worthwhile.

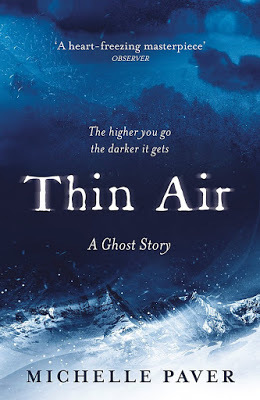

A bit more about ILL MET BY DARKNESS shortly. In addition today, also on the subject of supernatural horror, I’ll be reviewing and discussing yet another of Michelle Paver’s exceptionally frightening novels of the uncanny, THIN AIR .

If you’re only here for the Michelle Paver review, that’s fine. Just head on down to the bottom of today’s blogpost, where, as usual, you’ll find it in the Thrillers, Killers section. But before we do any of that, here are a couple of items of …

Other news

Other news

Firstly, an update on TERROR TALES OF THE HOME COUNTIES, the latest volume in my Terror Tales series, which you may now be aware is available to order (both electronically and in paperback) either from the publisher, TELOS, or from AMAZON. Watch this space for further info regarding other retailers.

I should also remind you that SPARROWHAWK, my Christmas ghost novella of 2010, which has had a recent makeover, is also available both as an ebook and paperback (again) and is now out on Audible too.

On top of that, two other collections of my Christmas-themed ghost and horror stories are newly out in paperback and on Kindle. They are

THE CHRISTMAS YOU DESERVE

and

IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER

.

On top of that, two other collections of my Christmas-themed ghost and horror stories are newly out in paperback and on Kindle. They are

THE CHRISTMAS YOU DESERVE

and

IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER

. And now for today’s big new item of interest …

Ill Met by Darkness

A few months ago, I was approached by Rob Morgan, that fine gentleman at SAROB PRESS, who, if you’re not familiar with them, specialise in publishing collections of supernatural tales, primarily in deluxe, hand-numbered, limited, hardcover editions, and was asked if I’d be interested in writing an all-new collection of folk-horror(ish) fiction; specifically, Sarob were looking at four novellas.

Now, that’s not the kind of offer a writer receives every day. So, even though I was not entirely sure my schedule would permit it, I said yes. That was one of the few good things that happened to me during last summer’s national lockdown, the imposition of which gave me more time to play with than usual, which in its turn enabled me to write ILL MET BY DARKNESS alongside my regular crime novel commitments

I think the thing that really swung it for me was the folk-horror element. For those not in the know (and surely there’s no one left on Earth by now?), folk-horror is a subgenre of horror fiction in which the focus rests on the British ‘old and wyrd’, particularly that half-forgotten world of ancient ritual and arcane belief.

It came to the attention of the wider public in the early 1970s with a famous unholy trinity of British horror movies,

Witchfinder General

(1968),

Blood on Satan’s Claw

(1971) and

The Wicker Man

(1973). With the exception of BOSC director, Piers Haggard, who is alleged to have coined the phrase, it’s unlikely that anyone involved at the time was aware that they were creating folk-horror. Most probably felt they were channelling traditional occult and witchcraft tropes, and weaving them into authentically grimy and realistic British rural backdrops (which was a worthy enough ambition).

It came to the attention of the wider public in the early 1970s with a famous unholy trinity of British horror movies,

Witchfinder General

(1968),

Blood on Satan’s Claw

(1971) and

The Wicker Man

(1973). With the exception of BOSC director, Piers Haggard, who is alleged to have coined the phrase, it’s unlikely that anyone involved at the time was aware that they were creating folk-horror. Most probably felt they were channelling traditional occult and witchcraft tropes, and weaving them into authentically grimy and realistic British rural backdrops (which was a worthy enough ambition). At the risk of sounding ludicrously big-headed, I like to think that I personally carried the folk-horror candle for quite a while after these films were long done and dusted, and well before the subgenre became as widely popular as it is now. Not just because of my own short horror fiction, which has often drawn on British folklore, but through the Terror Tales series I’ve been editing since 2011, an anthology round-trip of the British Isles, each volume attached to one particular region, the stories within (both the fictional and factual) drawing heavily and purposely on the lore and mythology of that region.

Okay, I’m not going to claim that I’m somehow responsible for the resurgence of interest in folk-horror; that would be palpable nonsense. But I’ve long been a fan, and am totally delighted to see it now getting the attention it deserves.

Which brings me back to SAROB PRESS and ILL MET BY DARKNESS. It was not a difficult thing for me to get stuck into. My top drawer has been crammed with folk-horror(ish) ideas for quite a while, and the four that I finally selected I penned in double-quick time, even though, as I say, these are novellas and novelettes rather than short stories. Sarob, I am glad to say, were very happy with them, and the finished result can be ordered right now.

For those who don’t mind their appetites being whetted, here’s a list of the stories included, each one accompanied by a tiny teaser ….

SNICKER-SNACK

One summer evening, Gilpin sets out across London, intending to get his hands on a semi-mythical piece of artwork, a picture once associated with a terrifying monster that no one ever sees and lives. He doesn’t even know if the image really exists, but he is absolutely determined. He will have what he wants, whatever the consequence, no matter how dire …

DOWN TO A SUNLESS SEA

The idyllic island of Crete. Azure seas washing rocky, sun-bleached shores. Inland vistas of vineyards and olive groves. A landscape steeped in myth. Anyone can enjoy themselves here, so long as they don’t delve too deeply behind the party island facade; so long as the distant past is left to rest, and its treasures remain untouched …

THE HELL WAIN

The Forest of Bowland. Lancashire’s best-kept secret. A pristine realm of hilltop, moor and fathomless woodland. When two London gangsters arrive there one Bonfire Night, at the remote village of Hackenthorpe, they have murder in mind. But immediately they’re uneasy. Why is it so quiet? Why is no one around? And yet why do they feel that they aren’t quite alone?

SPIRIT OF THE SEASON

Father Christmas lurks in our consciousness all the year round, not just in December. But his origins are mysterious, enigmatic, almost eerie. When a folklorist sets out to discover the truth behind the jovial myth, it leads him to Wenlock Castle in Oxfordshire, and a Christmas Eve that he and his companions will never forget, assuming they survive it …

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed (I’ll outline the plot first, and follow it with my opinions) … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THIN AIR

THIN AIR by Michelle Paver (2013)

OutlineIt’s 1935, the British Empire is still a thing, and the Raj is the jewel in its crown. It’s also the age of men, a time when adventurous chaps with public school backgrounds must all do their bit to enhance their country’s reputation, which often translates into having dangerous escapades in remote overseas locations (usually after leaving their compliant wives and sweethearts behind to worry bravely and quietly on their own).

Perhaps inevitably, mountaineering scores high on this agenda.

On this particular occasion, the object of the exercise is Mount Kangchenjunga in the Himalayas. At 28,169 feet, it’s the third highest mountain in the world, but easily the most difficult climb, and the worst killer of climbers by a long chalk. Even experienced teams are wary of it as so many who have attempted the peak previously have met with disaster.

We follow the story of this latest attempt through the journal-type memoirs of Dr Stephen Pearce, who is very much a part of that fearless set, though a likeable and unassuming man who is privately tormented by self-doubt. Pearce wasn’t originally supposed to be part of this expedition; he was shortly due to marry into a respected and well-connected family, though uncertainty about the future of ‘domestic bliss’ that apparently faced him led him to break things off, which overnight has made him the talk of London society.