Paul Finch's Blog, page 9

October 31, 2019

Galleries of Darkness - for October, Week 5

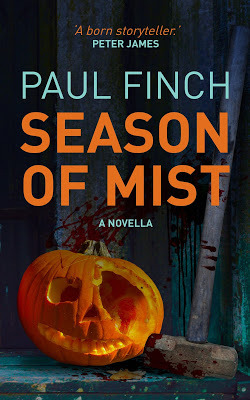

Halloween is finally here, so today I’m pleased to present my fifth and last GALLERY OF OCTOBER DARKNESS. You’ll find it further down the blog. In addition, I’ll be talking some more about SEASON OF MIST, which was my main autumn publication. Again, you’ll find that further down too.

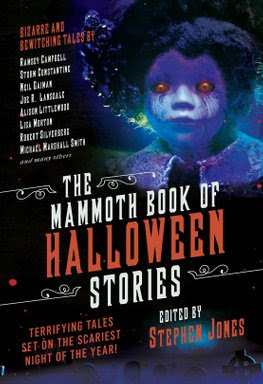

I’ll also be reviewing and discussing in my usual forensic detail - and this is a very timely one, I think you’ll agree - THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF HALLOWEEN STORIES , as edited by the indefatigable Stephen Jones.

If you’re only here for Mr Jones’ latest epic anthology, shoot straight down to the lower end of this column. As always, you’ll find it in the THRILLERS, CHILLERS section.

However, if you’ve got a bit more time, just hang around here a little longer, and we’ll talk a bit about SEASON OF MIST .

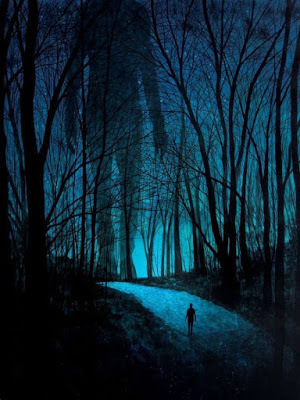

Starry nights, misty woods

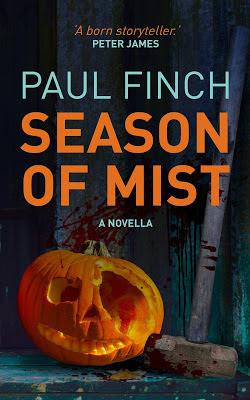

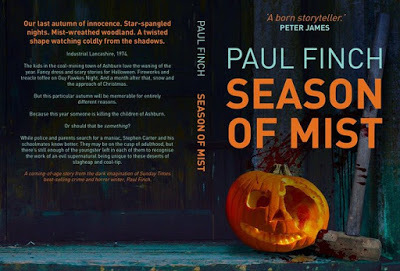

Starry nights, misty woodsI relaunched this novella last September specifically so that it would coincide with the autumn. And now I need to elaborate on that a little, because you could be forgiven for thinking that this book is all about Halloween, and that as we’ve now reached October 31, there isn’t much point reading it (assuming you haven’t done so already).

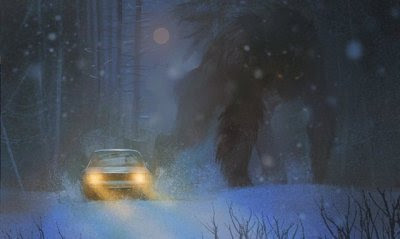

I must refute that. While Neil Williams’ wonderful cover-art is entirely appropriate for SEASON OF MIST because there is a dramatic high-point in it that occurs on Halloween Night, there are similar dramatic events on Bonfire Night and later on, in December, when an autumn of red leaves and mist (just think Sleepy Hollow and you won’t be far wrong) gives way to a winter of snow, ice and hard, glinting frost.

So, please don’t make the mistake of assuming that, now Halloween is over, that’s it, SEASON OF MIST is done. Trust me, it really isn’t. And if you haven’t already taken a chance on it, now is as good a time as any.

Next meanwhile, something that actually is ending ...

The final gallery

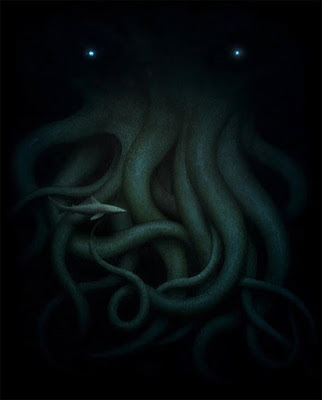

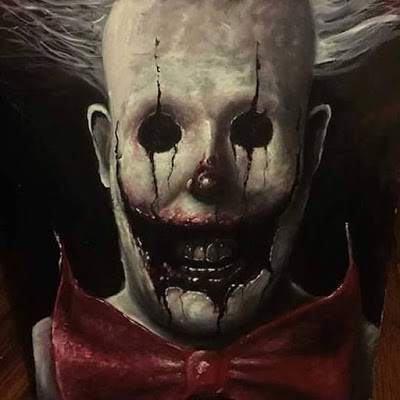

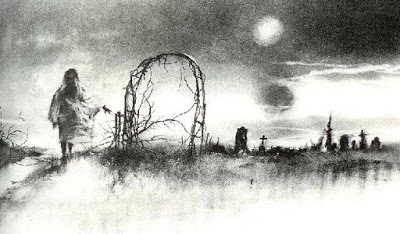

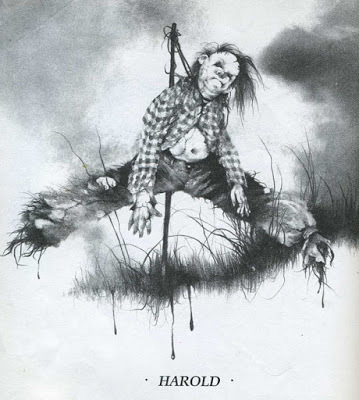

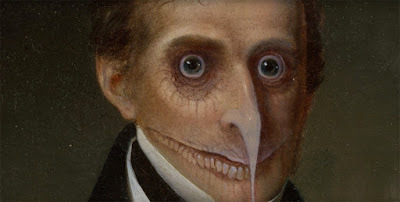

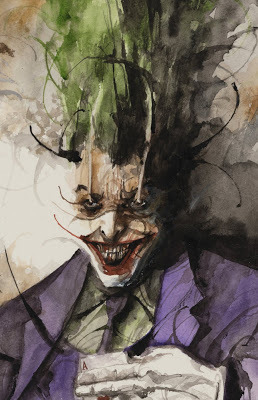

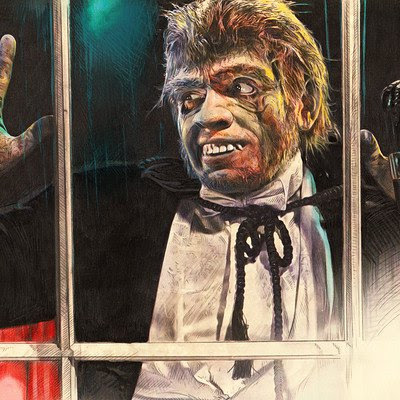

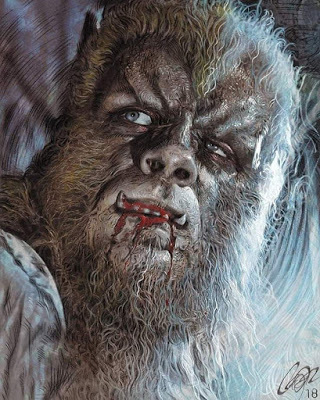

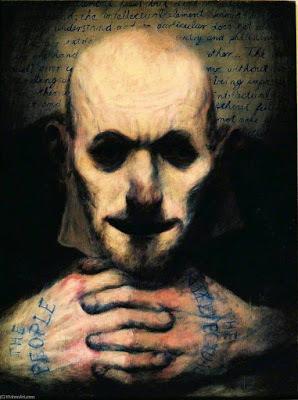

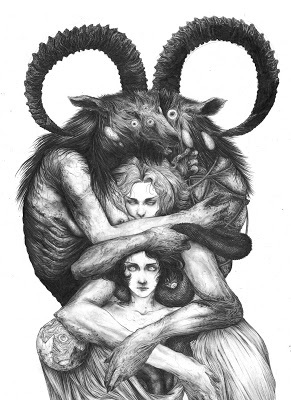

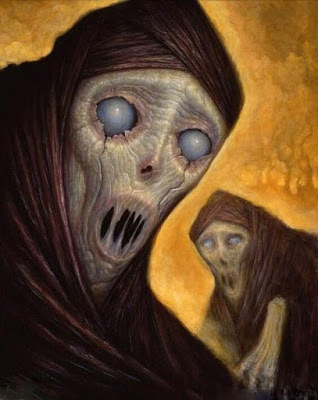

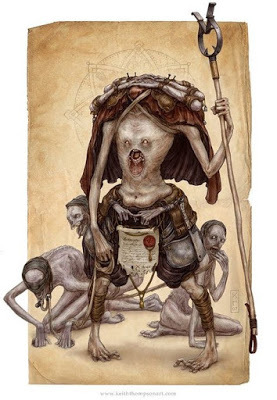

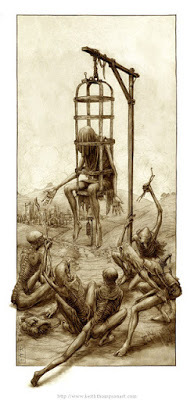

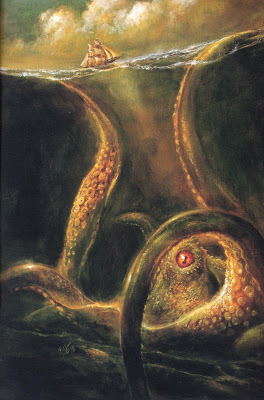

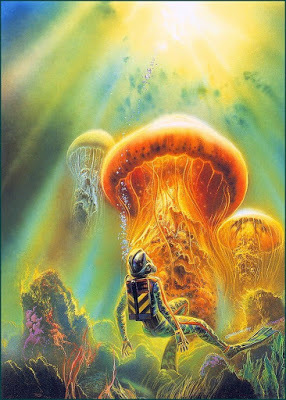

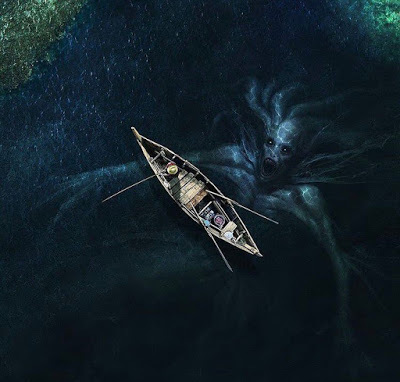

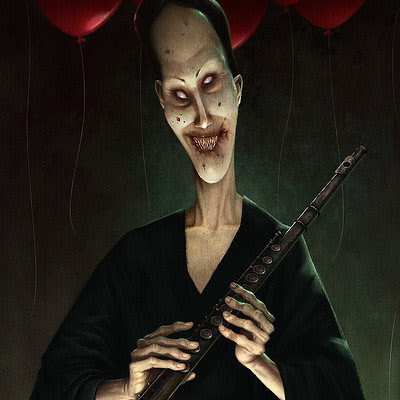

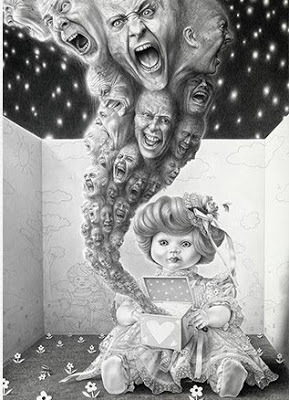

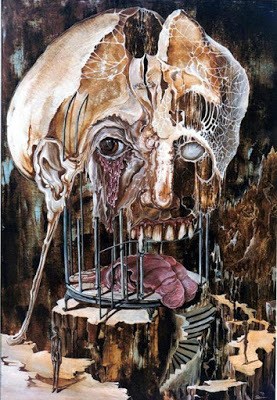

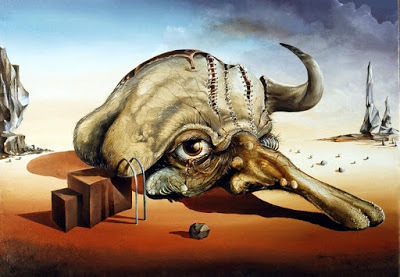

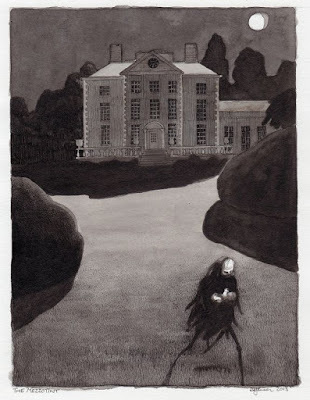

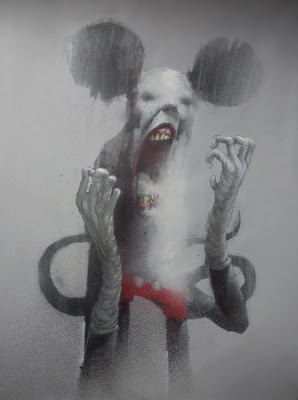

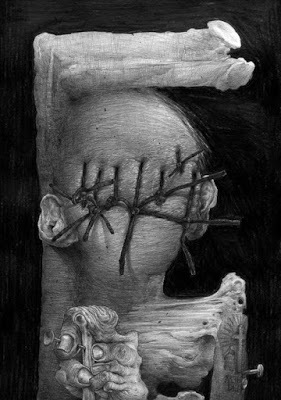

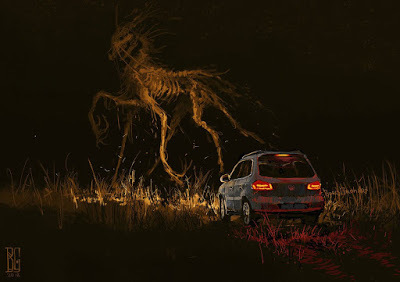

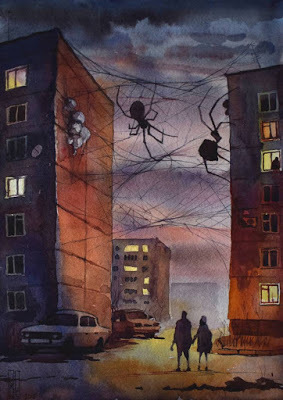

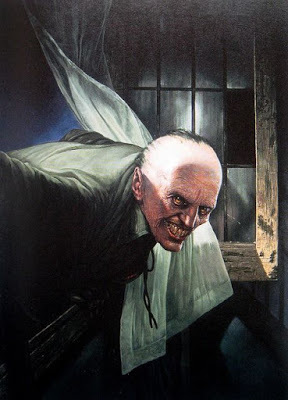

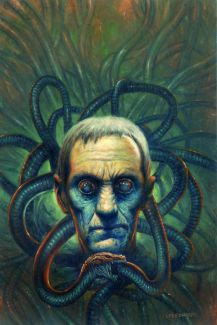

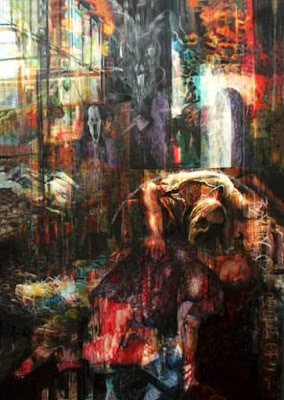

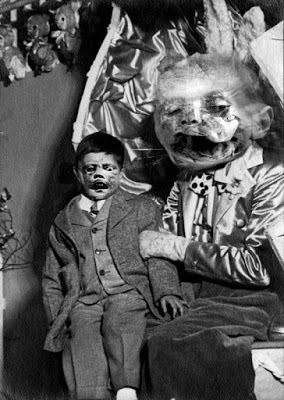

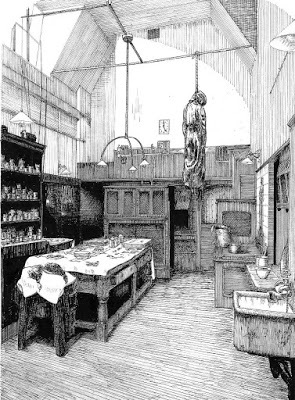

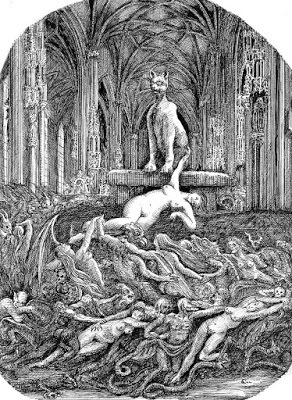

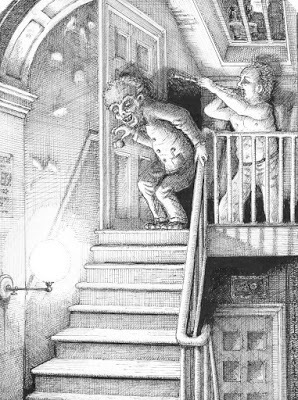

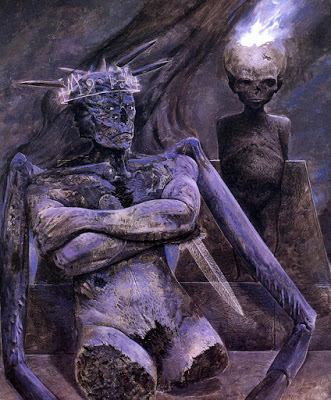

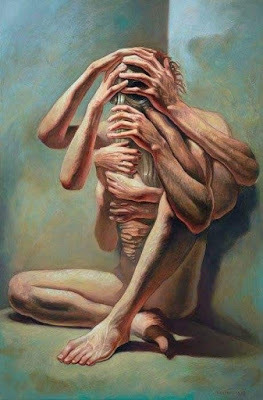

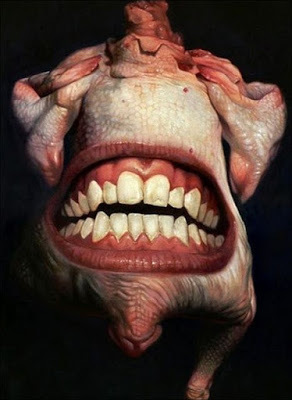

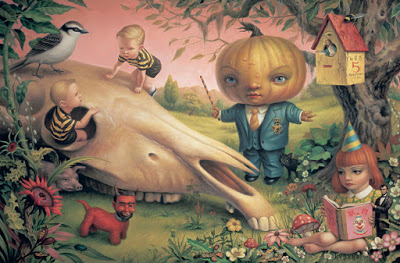

All through this last month, you’ll hopefully have noticed that I’ve been posting what I refer to as GALLERIES OF DARKNESS, each week focussing on 20 different artists - painters, concept guys, book illustrators, game designers and the like - who have occasionally dipped their brushes, nibs, whatever into the darkest inks. We’ve seen some wonderfully scary stuff drawn from some truly fiendish imaginations and realised on canvas, paper, screen etc in the most handsome and evocative ways.

Here, now that October is over, are my final 20.

You can see from the painting at the top of this column - Death as General Rides a Horse , by Edgar Bundy (1911) - that classical artworks, and even modern art done in the classical style, has often dealt with ghoulish subject matter. So, it’s not something new. That notwithstanding, I’ve mostly tried to select only contemporary artists for this series simply because it might help introduce you chaps to a few wonderful talents whom you might not yet have encountered.

Again, I give my customary warning that, though I have never selected anything for these galleries that is simply revolting or obscene, always opting instead for the terrifying and macabre, none of these artists hold back. There is some pretty eerie and twisted stuff on here. So, you have been warned.

Enjoy ...

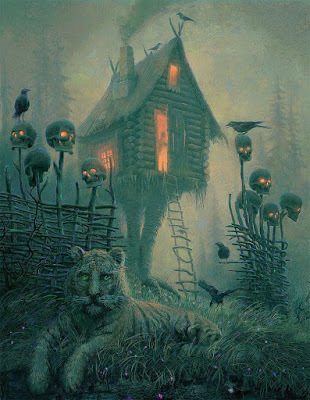

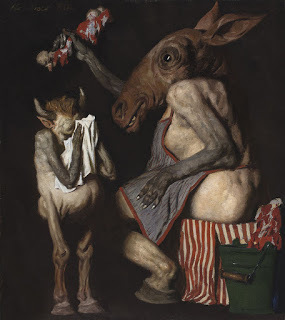

1. ANDREW FEREZ

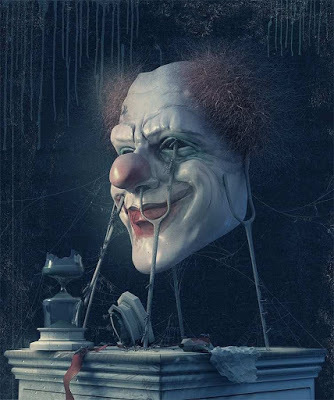

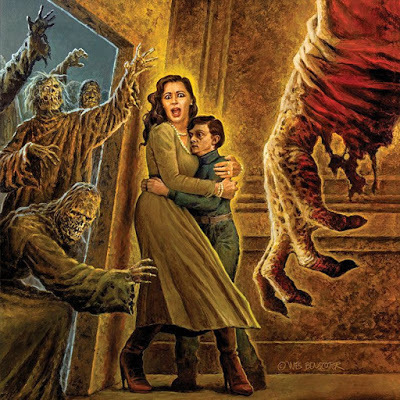

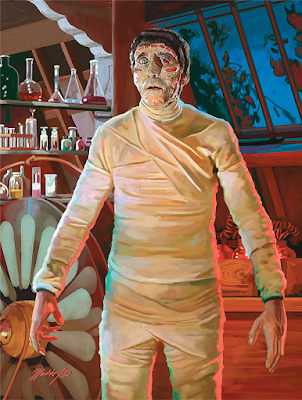

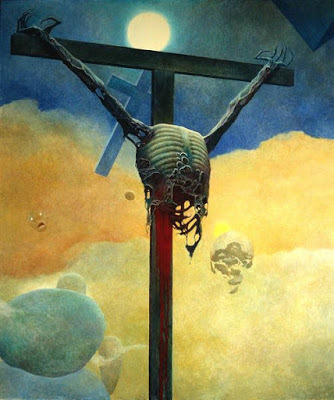

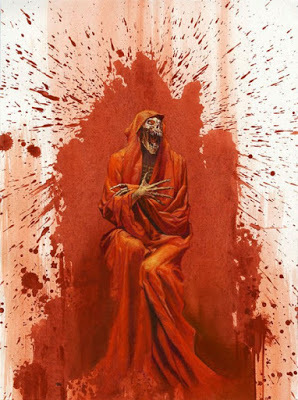

2. WES BENSCOTER

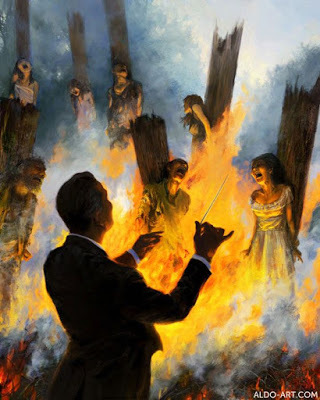

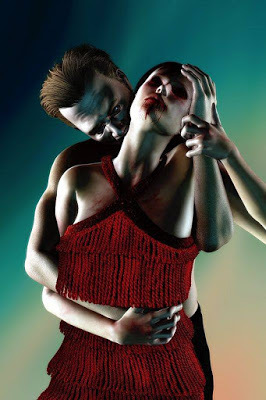

3. ALDO KATAYANAGI

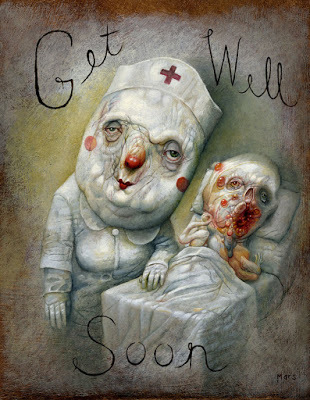

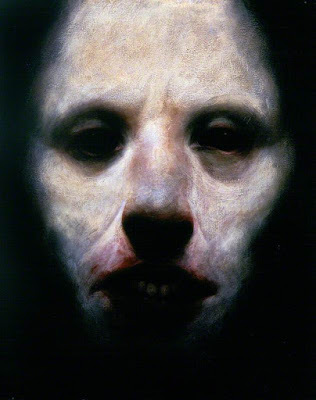

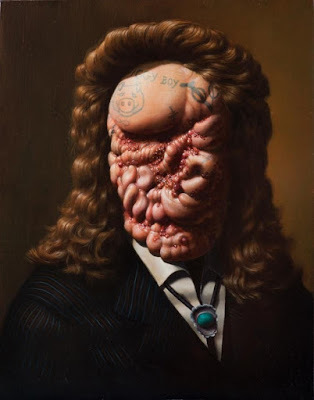

4. CHRIS MARS

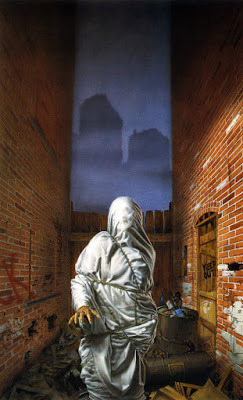

5. VINCENT CHONG

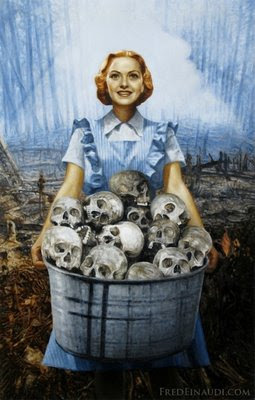

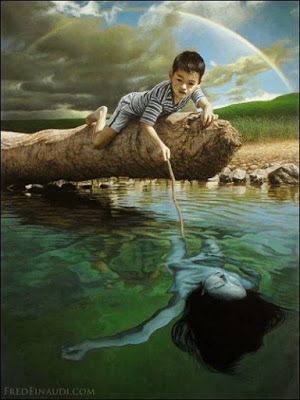

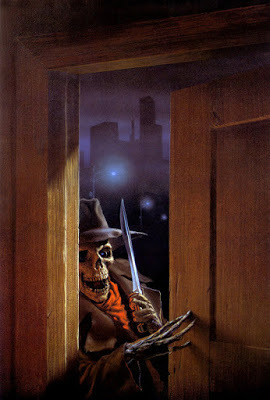

6. FRED EINAULDI

7. ANTON SEMENOV

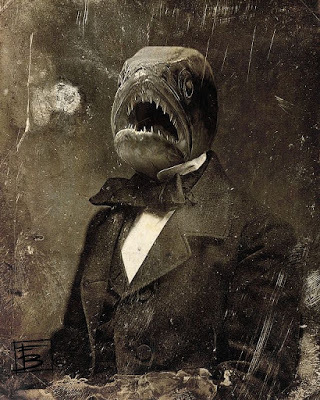

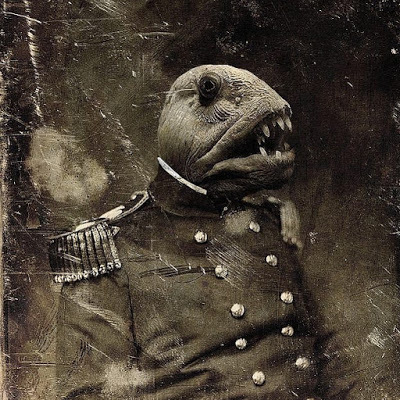

8. GABRIEL ASTAROTH

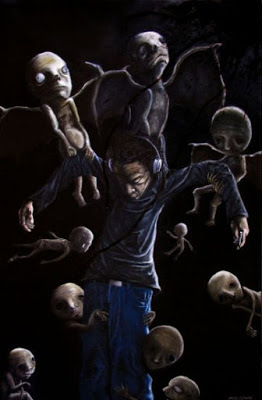

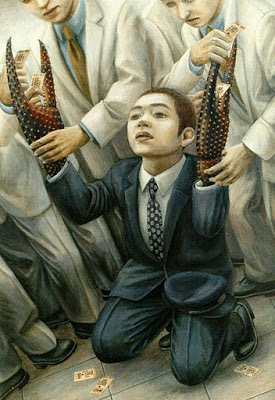

9. JEREMY ENECIO

10. ZACK DUNN

11. STEPHEN GAMMELL

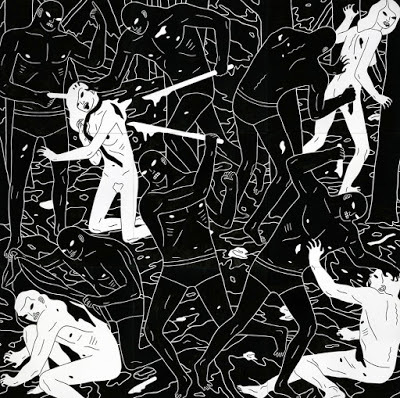

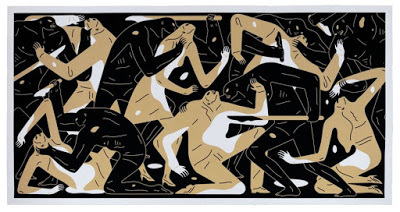

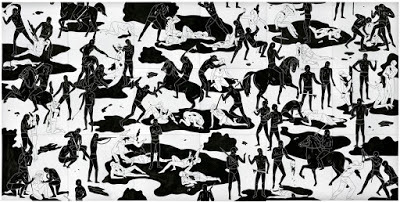

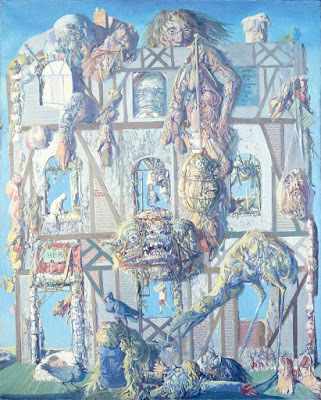

12. CHAPMAN BROTHERS

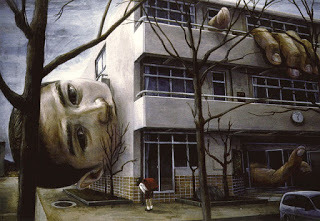

13. KAZUHIKO NAKARUMA

14. BEN BALDWIN

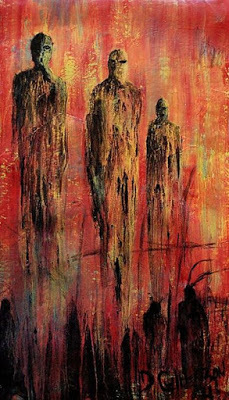

15. DANIELE SERRA

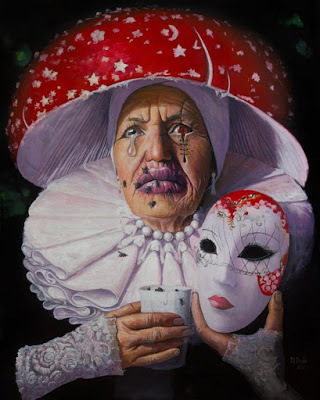

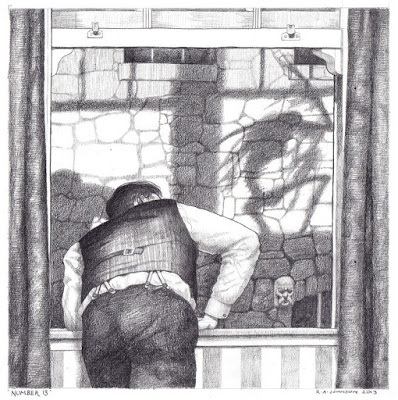

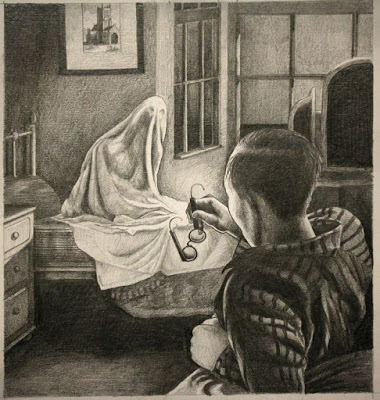

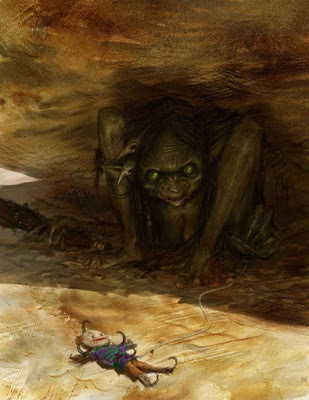

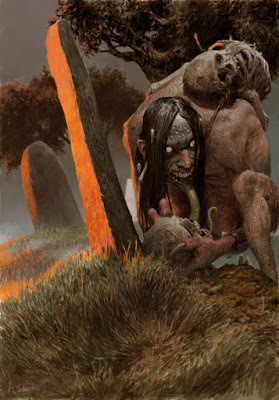

16. RUSSELL MARKS

17. FREDERICK COOPER

18. ALEXANDER REISFAR

19. SVETLIN VELINOV

20. DHOLL

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF HALLOWEEN STORIES edited by Stephen Jones (2018)

THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF HALLOWEEN STORIES edited by Stephen Jones (2018)As the title makes clear, a themed Halloween horror anthology, originally published in time for October 31 last year, though in truth it contains enough spooky tales and timeless treats to be readable at the misty, murky tail-end of any year.

Rather than simply hit you with a succession of brief short story outlines, I’ll first let the publishers give you their own official blurb, which neatly lays out the autumnal chills lying ahead:

Treat yourself to some very tricky stories! Halloween … All Hallows’ Eve … Samhain … Día de los Muertos … the Day the Dead Come Back … When the barriers between the worlds are at their weakest – when ghosts, goblins, and grisly things can cross over into our dimension – then for a single night each year the natural becomes the supernatural, the normal becomes the paranormal, and nobody is safe from their most intimate and terrifying fears.

The Mammoth Book of Halloween Stories brings you a dark feast of frightening fiction by some of the most successful and respected horror writers working today, including Ramsey Campbell, Neil Gaiman, Joe R. Lansdale, Helen Marshall, Richard Christian Matheson, Robert Shearman, Robert Silverberg, Angela Slatter, Steve Rasnic Tem, and many more, along with a very special contribution by award-winning poet Jane Yolen.

Here you will encounter witches, ghosts, monsters, psychos, demonic nuns, and even Death himself in this spooky selection of stories set on the night when evil walks the Earth …

Come the waning of the year, Halloween horror anthologies, much like Halloween horror movies, become a fixture on our ‘want lists’. Given that October 31, with its ghost stories and ghoulish pageantry, is easily the scariest night of the year in the western tradition, but also, for many, and for exactly the same reason, the most fun night too, it’s surely no surprise that writers and editors have visited it time and time again. Almost inevitably of course, those working at the darker end of the literary spectrum have colonised it most. But as a Brit, I’ve long had a beef with Halloween fiction, and this centres around the fact that it’s almost invariably hogged by Americans.

Now, don’t get me wrong – the US has produced some of the world’s greatest horror writers, not to mention novels, stories and film scripts, and I have absolutely no complaints about that. But it’s peeved me many times in the past to pick up a collection of new Halloween fiction and find that, almost without exception, every story relates to the American experience. And whenever I’ve expressed these sentiments to fellow Brits, I’ve been told: “Well, that’s because in the US it’s an old festival, while in the UK it’s fairly new.”

Come on, guys!

In the UK Halloween is NOT new. It’s one of our most ancient celebrations; it’s just that it hasn’t been quite as big a party in recent times because the highlight of our autumn, as imposed upon us by royal decree, Bonfire Night, occurs only five days later.

But now, thankfully, we have an anthology that puts all this right … perhaps understandably so, given that Stephen Jones, one of the world’s most respected and hardest working anthologists, is British. Not that he focusses purely on the UK in The Mammoth Book of Halloween Stories ; far from it. He certainly includes a number of front-running British horror authors – Neil Gaiman, Storm Constantine, Ramsey Campbell, Michael Marshall Smith et al – but there are plenty of Americans in here as well – Richard Christian Matheson, Lisa Morton, Joe R Lansdale and Thana Niveau, among others, not to mention a couple of Aussies in Robert Hood and Angela Slatter, and a Canadian in Nancy Kilpatrick, while at least two of the stories, Memories of Día de los Muertos by the aforementioned Kilpatrick, and the spine-chilling Not Our Brother by the legendary Robert Silverberg, take us to Mexico, where Día de Muertos is not just a holiday but a revered religious fête.

So, rest assured, a wide range of voices and perspectives are on offer in this one, which, as I say, makes a refreshing change, and enables Steve Jones to tackle the many different aspects of this complex, multi-layered festival, and the varied customs wrapped up in it (not all of which, I have to say, are purposely terrifying – the editor himself prewarns us about this in his intro).

But ultimately, of course, for all these different takes, there is a common thread. Halloween is the night on which the realms of the living and the dead are closest to each other, when spirits and other entities, both benign and malignant, can cross over into our world and commune with us. And the late autumn atmosphere of darkness, mist and swirling leaves only adds to this eeriness, and thus provides a backdrop that runs throughout.

It’s all become rather ‘on the nose’ in real life, of course. An interesting essay at the beginning of the book, When Graveyards Yawn , penned by Jones himself, explains how the iconic imagery of Halloween – witches on broomsticks, black cats, jack-o-lanterns – was first popularised in the late Victorian era via the publication in America of spooky postcards. There is little of that to be found in the actual fiction here. Jones is far too astute and eclectic an editor to select anything so obvious (and where it does appear, it is often turned on its head: Lantern Jack by Christopher Fowler, for example, or The Halloween Monster by Alison Littlewood). But the essence of the traditional Halloween remains. In Neil Gaiman’s October in the Chair , for example, a tale redolent of cold, dark autumn nights, the personifications of the months gather at a woodland bonfire to hear October tell the sad story of a lonely boy who runs away from home, befriends a ghost and decides that he never wants to leave its side … ever. While Adrian Cole’s Queen of the Hunt sees a rural cop investigating what looks like an animal-attack fatality but worried by the rapid approach of Halloween, because he knows the weird rituals with which it is celebrated in these parts, and fears that the two may be connected. Equally traditional is Marie O’Regan’s Before the Parade Passes By , wherein a recently-made widow and her young daughter move to a new town, the community of which appears to embrace them … except that Halloween is almost upon them, and the child is increasingly scared by the prospect of the mysterious ‘parade’. Perhaps most atmospheric of all, though, is Storm Constantine’s Bone Fire , which takes us into a pre-industrial age British village, where Halloween is lavishly celebrated, and all kinds of strange and interesting guests are anticipated (more about this story later).

Of course, the real test of any horror anthology is whether it’s frightening or not. The stories it contains can be superbly written and clever as Hell – and all these things are to be found in this tome – but if it doesn’t put a few chills up the reader’s spine, then it hasn’t done its job.

Well, I’m glad to say that The Mammoth Book of Halloween Stories ticked this box too. Particularly memorable in this regard is Her Face by Ramsey Campbell, in which a young boy regularly buys cigarettes for his single mum in the corner shop across the road, but as Halloween approaches, becomes increasingly afraid of the horror masks it is stocking. We also have Robert Silverberg’s previously mentioned Not Our Brother , an intensely frightening Samhain epic, which sees an American collector of Mexican memorabilia head south of the border to spend the Day of the Dead in a remote village, where he aims to persuade the locals to sell him some valuable tribal masks, unaware of the level of resistance he’ll encounter. And The Folding Man by Joe R Lansdale, a classic pursuit horror in which a unstoppable monster is unleashed on a bunch of irreverent teens (again, more about this story later).

These are chilling tales all, showing scare-meister authors at the top of their game, and they’re not the only ones. Angela Slatter’s The October Widow will also creep you out, as will Cate Gardner’s Dust Upon a Paper Eye and Lisa Morton’s The Ultimate Halloween Party App , to name but a few (yet again, more about the first two of that trio later).

All this said, it isn’t just about being frightened. The Mammoth Book of Halloween Stories also contains some serious and thought-provoking fiction. Michael Marshall Smith’ s The Scariest Thing in the World and Alison Littlewood’s The Halloween Monster are both excellent and beautifully written tales, which remind us that man’s deadliest foe, whatever night of the year it is, is man himself. While other contributions, if not exactly head-trips, go way beyond the others in terms of dark, surreal fantasy. A good example is the ever-reliable Steve Rasnic Tem’s strangely affecting Reflections in Black , in which an embittered man travels across the States, looking to hook up with an old girlfriend, and encountering all kinds of Halloween weirdness en route, while Robert Shearman’s Pumpkin Kids is so strange and disturbing that it defies a thumbnail outline – you’ve just got to read it.

And that’s the message for the whole of this book, really. Buy it and read it. It’s not the first Halloween anthology, and it certainly won’t be the last, but I suspect it’ll never have many rivals that can boast such a broad range of story types and Halloween subject-matter.

It was published for Halloween last year, but it’ll work just as well for Halloween this year. So, waste no further time …

And now …

THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF HALLOWEEN STORIES – the movie.

Just a bit of fun, this part. No film maker has optioned this book yet (as far as I’m aware), but here are my thoughts on how they should proceed, if they do.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in.

It could be that we opt for Neil Gaiman’s concept of October occupying a woodland chair while a bonfire blazes nearby, regaling us with chilling stories of the season; or maybe we just fall back on that old chestnut (see what I did there?), with four strangers thrown together in unusual Halloween circumstances, which require them to relate spooky stories … perhaps a late-October party at

The Monster Club

, hosted by Erasmus the vampire. But basically, it’s up to you.

It could be that we opt for Neil Gaiman’s concept of October occupying a woodland chair while a bonfire blazes nearby, regaling us with chilling stories of the season; or maybe we just fall back on that old chestnut (see what I did there?), with four strangers thrown together in unusual Halloween circumstances, which require them to relate spooky stories … perhaps a late-October party at

The Monster Club

, hosted by Erasmus the vampire. But basically, it’s up to you.Without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

The October Widow (by Angela Slatter): Hedgewitch Mirabel travels from one town to the next each Halloween, seducing and sacrificing handsome young men, both to replenish the land and her own youth – as she has been doing for decades. She thinks she is doing good, but ageing Cecil, who can’t forget the loss of his son, has other ideas …

Mirabel – Miranda RichardsonHenry – Asa ButterfieldCecil – Nick Brimble

Dust Upon a Paper Eye (by Cate Gardner): A semi-derelict inner-city theatre is the venue for a strange Halloween Night show, the eccentric oddball, Herr Smithson, having promised to entertain a private audience with lifesize, dancing dolls. But when former homeless girl, Henrietta, is brought in to prepare the dolls’ makeup, she notices something rather peculiar about them …

Henrietta – Florence Pugh Herr Smithson – Phil Davies

Bone Fire (by Storm Constantine): In a pre-industrial age English village, two lasses seek excitement and love as the annual All Hallows celebration approaches. But neither of them are really ready for the mysterious lads they will meet in the Bone Fire smoke …

Emilie – Anya Taylor-Joy Jenna – Mia Goth

The Folding Man (by Joe R Lansdale): It’s Halloween Night, and Jim and his friends, out for a party, make the mistake of mooning a car full of nuns. But this is no ordinary party night, and these are no ordinary nuns, and when they chase the boys and unleash the terrifying ‘folding man’ on them, Jim realises that this will be a Halloween like no other …

Jim – Freddie Highmore

Published on October 31, 2019 01:02

October 23, 2019

Galleries of Darkness, for October - Week 4

Okay, we’re almost there. One week to go and it’s the scariest date in the calendar. Yes, Halloween is only seven days away. That’s relevant to today’s blog for a couple of reasons. First of all, it means that I’ve only got two more of my GALLERIES OF DARKNESS to post. Today’s will be the fourth, while the fifth and final one will appear on October 31 itself. As always, there’re some some cracking if terrifying images here. All you need to do is scoot on down the column and check them out.

The second reason is because I’m now giving you a week’s advance warning that on the evening of October 31, I’ll be at Waterstones, Kendal, partaking in HORROR STORIES FOR HALLOWEEN. More about that shortly, as well.

In addition this week, and again because we are now encroaching on the spookiest night of the year, I’ll be reviewing and discussing the engrossing horror anthology, NEW FEARS, as edited by Mark Morris.

If you’re only here for the NEW FEARS chat, no problem. Just zoom on down to the lower end of today’s blog, which is where I usually post my book-talk, and get on with it straight away. However, if you’re interested in other things I might have to say, I’m going to talk a little bit first about …

Halloween Night, Kendal style

As previously mentioned, it’s official title will be

HORROR STORIES FOR HALLOWEEN

, and I’m very honoured to have been asked to participate in what looks like it’ll be an awful lot of fun, especially as I won’t be the only writer there. I’m delighted to be in the company of Simon Kurt Unsworth, author of, among other titles,

THE DEVIL

’S DETECTIVE

and

THE DEVIL’S EVIDENCE

, and Ray Cluley, author of

WATER FOR DROWNING

and PROBABLY MONSTERS.

As previously mentioned, it’s official title will be

HORROR STORIES FOR HALLOWEEN

, and I’m very honoured to have been asked to participate in what looks like it’ll be an awful lot of fun, especially as I won’t be the only writer there. I’m delighted to be in the company of Simon Kurt Unsworth, author of, among other titles,

THE DEVIL

’S DETECTIVE

and

THE DEVIL’S EVIDENCE

, and Ray Cluley, author of

WATER FOR DROWNING

and PROBABLY MONSTERS.By the sounds of it, we’ll be kicking things off at 7pm (though the shop doors actually open at 6.30pm), and proceedings will commence with me and Messrs. Cluley and Unsworth giving a 15-minute reading each from our own work, all pieces selected for their sheer scariness, I understand. After that, there’ll be questions and answers and, if we’ve hooked enough folk with our blather, some selling and signing of books.

From my own point of view, the event will also be a kind of unofficial launch for my two Autumn titles,

SEASON OF MIST

and

TERROR TALES OF NORTHWEST ENGLAND

.

From my own point of view, the event will also be a kind of unofficial launch for my two Autumn titles,

SEASON OF MIST

and

TERROR TALES OF NORTHWEST ENGLAND

. I’m hopeful that a few of my crime titles will be there as well; they are pretty dark, verging on horror in many cases, so I don’t think they’ll be inappropriate for Halloween Night. The other guys’ works will also be on sale of course.

So, if you’re interested in this kind of thing, there’ll be lots of books to buy and get signed. If you live in the vicinity of Kendal – Cumbria, Westmorland or Lancashire – this is undoubtedly one that you won’t want to miss.

So, if you’re interested in this kind of thing, there’ll be lots of books to buy and get signed. If you live in the vicinity of Kendal – Cumbria, Westmorland or Lancashire – this is undoubtedly one that you won’t want to miss. Just follow the links for more details and, if you decide you’re keen, make sure to get yourself down there for 7pm.

And now, in keeping with the season …

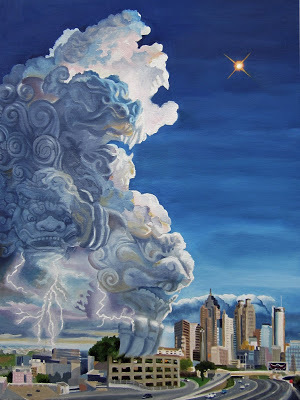

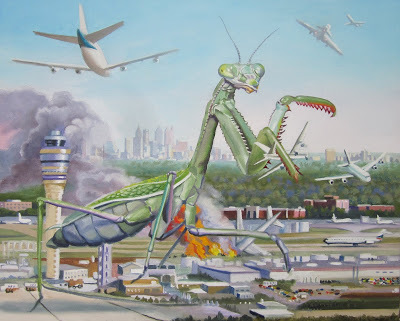

Images of Darkness

Hopefully, regular visitors to this page will now be aware that all through October, in recognition of the approaching date, I’ve been posting galleries of artists who’ve dabbled in the darkness. In short, each Thursday, I’ve focussed on 20 painters, illustrators and the like who have shared some of their deepest nightmares with us, the idea being that when the final gallery goes up on October 31, we’ll have checked out 100 in total.

A quick bit of info before you dive in. Despite my enthusiasm, I’m not qualified to talk in detail about any of these men and women. So, I’m going to let the pictures do the talking. However, what I will say is that most of them are contemporary. I mean, there’ve been some great images of horror painted in the long-ago past; check out The Temptation of St Anthony by Matthias Grunewald (1516) at the top of today’s blog. But those are mostly well known already. By focussing on more recent practitioners, I’m hopeful there’ll be something a bit new here for everyone.

But if you want further detail on any of these individuals. And if you want to enquire about prints, originals, commissions and the like, I’ve posted links wherever possible. Just follow those; some will take you to the artists themselves.

And now my customary last-minute warning.

I’ve not selected any image that I consider to be offensive or plain disgusting. But these pictures were chosen because of their power to disturb and terrify, and the immensely talented individuals responsible for them do NOT hold back. Those of a nervous disposition should tread warily from here in …

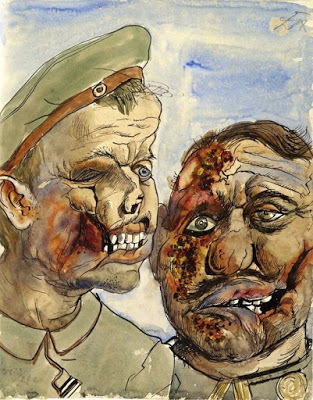

1. KEN CURRIE

2. STEVE UPHAM

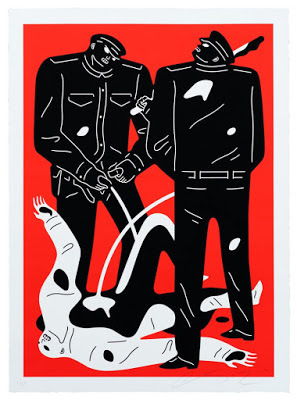

3. CLEON PETERSON

4. BACIUS9

5. KIM MYATT

6. DAVE CORREIA

7. DAVE CULBERTSON

8. LEO PLAW

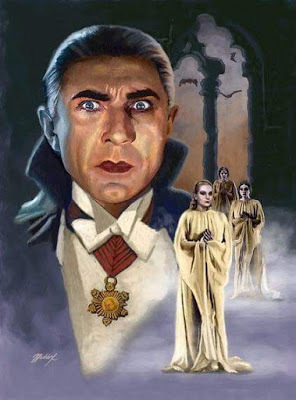

9. MARK MADDOX

10. MICHAEL HUTTER

11. DADO

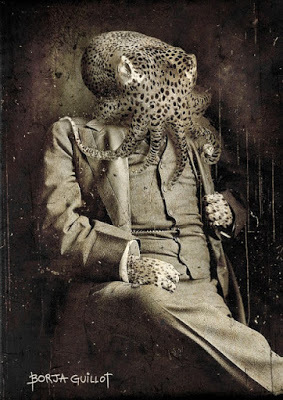

12. BORJA GUILLOT

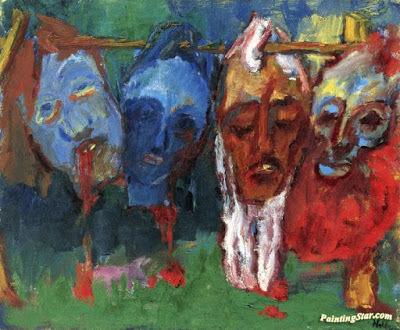

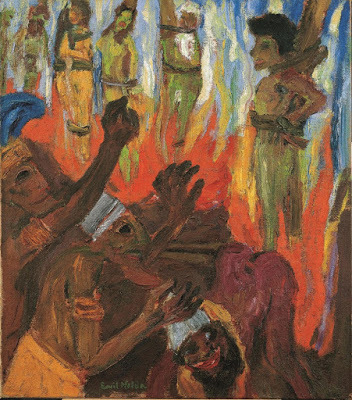

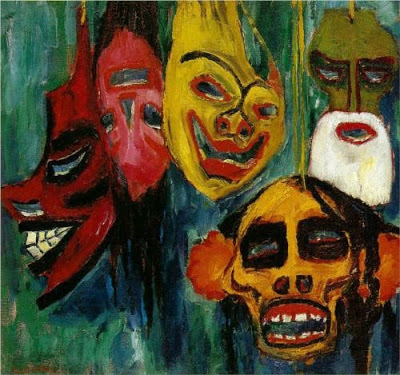

13. EMILE NOLDE

14. ERIC LACOMBE

15. VALERA LUTFULLINA

16. ZDZISLAW BEKSINSKI

17. ALEX KONSTAD

18. ANNA PAVLEEVA

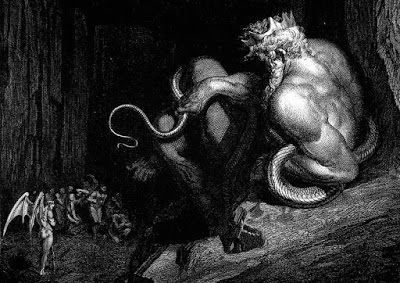

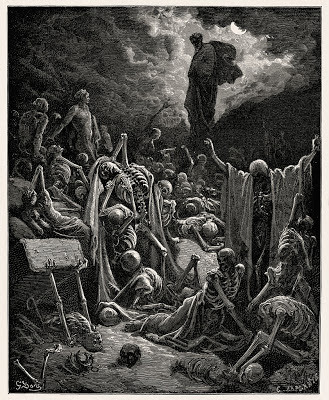

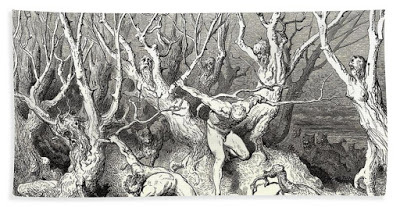

19. PAUL GUSTAV DORE

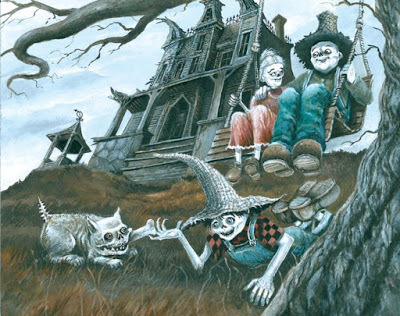

20. GLENN CHADBOURNE

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

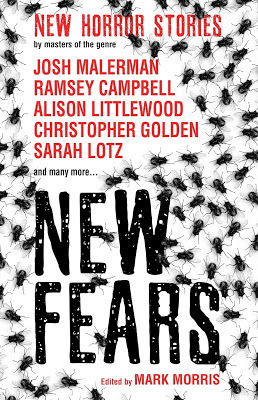

NEW FEARS edited by Mark Morris (2017)

NEW FEARS edited by Mark Morris (2017)The first volume in a sadly short-lived series of horror anthologies from Titan, in which editor Mark Morris attempts to bring together a wide range of original and contemporary scary fiction, and for the most part is very successful.

There would only be one other in the series, New Fears 2 , which we’ll review at a later date, but that’s a sad story in itself because the quality of writing on display here indicates that the New Fears project could have gone on to make a big and prolonged impact in the world of short spooky stories.

First of all, rather than simply hit you with a succession of brief short story outlines, I’ll let the publishers of this first volume give you their own official blurb, which neatly lays out the varied and cerebral chills in wait for you:

The horror genre’s greatest living practitioners drag our darkest fears kicking and screaming into the light in this collection of nineteen brand-new stories. In ‘The Boggle Hole’ by Alison Littlewood an ancient folk tale leads to irrevocable loss. In Josh Malerman’s ‘The House of the Head’ a dollhouse becomes the focus for an incident both violent and inexplicable. And in ‘Speaking Still’ Ramsey Campbell suggests that beyond death there may be far worse things waiting than we can ever imagine...

It seems like aeons since non-themed horror anthologies were a regular fixture on our British bookshelves. The golden age of such appears to have been the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, when Pan and Fontana each brought out an annual volume, their two series eventually running to 30 and 17 books respectively and introducing a whole host of new talent to the scare fare spectrum. With the supposed change in reading fashions since then – which dubious proposition is a whole new blog on its own! – it’s become increasingly difficult for professional publishers to sell collections of original short horror fiction (or so they’ve convinced themselves), so the onus has fallen on the independent market to keep the flag flying, and though a wide range of smaller imprints have done a heroic job, much of their output has sadly flown way under the public radar. Every so often, however, a new title emerges with serious mass-market potential.

The New Fears project was certainly one of these, especially as it had Mark Morris at the editorial helm, a skilled and experienced horror and fantasy author in his own right. Unfortunately, as I’ve already mentioned, such hopes would be unfulfilled, the series only hitting us with two volumes before folding. However, if nothing else, that gives us another two book-loads of intriguing and chilling fiction from the multinational pens of some of the genre’s most exciting names: from some of the all-time old reliables like Stephen Gallagher, Ramsey Campbell and Stephen Laws to relative newcomers like A.K. Benedict, Sarah Lotz and Josh Malerman.

As you’d expect with such a wide range of voices, we get an eclectic procession of stories, the editor consciously and wisely, in my view, looking to draw in every aspect of the current horror scene, though he eschews anything that I’d describe as gratuitous or extreme.

Possibly the most gruesome tale in the book is Brian Keene’s Sheltered in Place , which, as it concerns a mass shooting at an airport baggage-handling depot, horrifyingly underlines a big issue that is currently causing arguments and disputes all across North America today. A less serious tale, though no less blood-soaked, is Stephen Laws’ The Swan Dive , in which a potential suicide is rescued in mid-fall from the Tyne Bridge by a mysterious winged being called Swan, who takes him on a wild, carnage-strewn journey of revenge across the whole wretched city.

Meanwhile, macabre rather than gory – and perhaps an heir to some of those Pan Horror contributions that I referenced earlier – is Sarah Lotz’s mischievous The Embarrassment of Dead Grandmothers , in which young Stephen takes his obnoxious grandma to the theatre, only for the old lady to die half way through the performance, a fact Stephen must conceal when he notices that good-looking Liz from work is also in the audience and chatting her up becomes a higher priority. Also cut from the old Pan Horror cloth, and one of the best and most unsettling stories in the book for my money (with a real jolt of a twist), is Kathryn Ptacek’s Dollies , in which a disturbed child names all her dolls Elizabeth, every so often inexplicably pronouncing that one of them has died from smallpox and placing it on a dusty old shelf. Her parents struggle with this weirdness, but then their daughter is raped, and a real baby is suddenly on the way, and yet again, it seems, the child will be called Elizabeth.

In sharp contrast, subtlety is the order of play with several other contributions. First off, Alison Littlewood delivers an excellent low-key study of a relationship undermined by the merest hint of supernatural evil in The Boggle Hole , while in Nina Allan’s soulful and rather literary Four Abstracts , an art historian travels to an isolated Devonshire cottage, where she must sort out a deceased artist’s various unsold paintings, only to learn that the former occupant had an unhealthy obsession with spiders.

While these stories, and others like them, disconcert you with their restraint, others revel in full-on Gothic horror of the old school.

The best example is surely Angela Slatter’s No Good Deed , (apparently a continuation of a longer narrative, which commenced in a different publication, though it can easily be read as a stand-alone), in which a medieval bride awakens in the tomb where her scheming husband has interred her, having poisoned her and mistaken her for dead, and yet, with the aid of the previous bride, whom he successfully murdered, escapes and plots her revenge. Also on the ghost story trail, AK Benedict’s Departures sees an alcoholic literally enter the Last Chance Saloon in the form of a depressing airport pub where those not yet supposed to have died find themselves gathered. Perhaps a more traditional supernatural chiller is The Salter Collection by Brian Lillie, which sees the ramblings of a deranged logging magnate, as captured on a collection of wax cylinders, reveal a terrible secret.

All that said, there are three particular stories in here that I found especially spooky.

The first two come from Ramsey Campbell and Muriel Gray – Speaking Still and Roundabout respectively – but more about those two later in this review.

The other one is Josh Malerman’s The House of the Head , which is hugely original as well as chilling, and concerns a child’s love for her lavish new doll’s house, only for her to one day notice that a broken doll has infiltrated the happy home, a ghost doll she realises, which is the prelude to a miniature but very alarming (if pint-sized) haunting.

I wouldn’t say that any of the stories in this collection, and there are 19 in total, are genuinely terrifying, at least not in as much as they caused me to lose sleep. However, they are mostly dark and disturbing, and in all cases the quality of the writing shines through. This may officially be a horror collection, but it’s also of strong literary interest. I drew specific attention to Nina Allan’s story in that regard, but nearly all the rest of the stories are exquisitely crafted and make for an all-round excellent reading experience.

And now …

NEW FEARS – the movie.

Just a bit of fun, this part. No film maker has optioned this book yet (as far as I’m aware), but here are my thoughts on how they should proceed, if they do.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. It could be that each segment is an unsolved paranormal case, as handed by one retired and decrepit investigator to a young up-n-comer (al la Ghost Stories), or perhaps they are tales told by a group of travellers who become lost in an underground catacomb and are then confronted by a mysterious monk (a la Tales from the Crypt). But basically, it’s up to you.

Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book, but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for adaptation in a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, come in. It could be that each segment is an unsolved paranormal case, as handed by one retired and decrepit investigator to a young up-n-comer (al la Ghost Stories), or perhaps they are tales told by a group of travellers who become lost in an underground catacomb and are then confronted by a mysterious monk (a la Tales from the Crypt). But basically, it’s up to you.Without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I would choose:

Speaking Still (by Ramsey Campbell):

Recently made widower, Daniel, is convinced that his deceased wife, Dorothy, is leaving phone messages from the afterlife. Close friend, Bill, is very concerned because this clearly isn’t a happy afterlife. Dorothy’s late mother was a dangerous schizophrenic, who so resented being committed that she promised her daughter that she’d be waiting with vengeance after death. Now it seems that this has happened …

Bill – Bill NighyDaniel – Jim Carter

Eumenides – The Benevolent Ladies (by Adam LG Nevill):

Stuck in a dead-end job in a boring Midlands town, Jason is amazed when aloof but sexy Electra agrees to go on a date with him. The only trouble is that she wants to visit the local zoo, which has been derelict for years and has a very dark history …

Jason – Russell ToveyElectra – Genevieve Gaunt

The Abduction Door (by Christopher Golden):

An urban legend becomes real when a child disappears through ‘the Abduction Door’, a mysterious and diminutive hatchway, which comes and goes in the city’s elevators. Her distraught father attempts to follow her, and finds himself in a nightmare world of human-sized ovens and living scarecrows …

The Mother (because our leads can’t all be male) – Katheryn Winnick

Roundabout (by Muriel Gray):

A stubborn council workman is determined to clear ‘the Dark Thing’ off the overgrown Blowbarton roundabout. This mysterious, elusive something has been there ever since a bizarre piece of art rescued from the Afghan desert and erected as an anti-colonialist symbol was removed for distracting motorists. But the intrepid worker doesn’t know what it is or what terrible power his mysterious adversary possesses …

Workman – Paul WhitehouseArtist – Tim Roth

Published on October 23, 2019 23:49

October 17, 2019

Galleries of Darkness, for October - Week 3

Okay, it’s now Week 3 of my OCTOBER GALLERIES OF DARKNESS, and judging from the responses I’m getting on Facebook and Twitter so far, most people seem to approve. This week again, I’ll be focussing on 20 more artists – painters, book illustrators, game designers etc – who’ve made their nightmares so vivid and real that the rest of us can be enjoy them (or be terrified by them) just as much.

On top of that, because it’s still October and the focus remains on extreme darkness, I’ll be reviewing and discussing in my usual forensic detail THE ICE LANDS by Steinar Bragi. This is a very strange and disturbing novel, my first actual venture into Nordic Horror (as opposed to Nordic Noir), and in truth was unlike anything I’d ever read before. I thoroughly enjoyed reviewing it, though it was undoubtedly a challenge.

If you’ve only popped in for THE ICE LANDS review, you can locate it, as usual, at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Hurtle on down there and immerse yourself in it straight away. On the other hand, if you’re in no rush, here are a couple of other things that might be to your liking. Not just our latest Gallery of Darkness – you’ll find that in due course – but this as well …

Darkness in the heart of Wigan

After a strap-line like that you may indeed wonder what I’m about to discuss with you. Well, it’s at least as exciting as it sounds.

Basically, for the third year on the trot, I’m honoured to have been asked to participate in WIGAN NOIR at the Old Courts Courtroom (below, right).

Loosely, it’s part of the Noir at the Bar phenomenon, which first came over to Britain from the USA several years ago, and which sees published crime and thriller writers get up on podiums in the midst of crowded drinking-holes and read out concise chunks from their latest or forthcoming novels (just enough usually to whet the appetites of all those in attendance), and then answer a few questions from guest interviewers.

Loosely, it’s part of the Noir at the Bar phenomenon, which first came over to Britain from the USA several years ago, and which sees published crime and thriller writers get up on podiums in the midst of crowded drinking-holes and read out concise chunks from their latest or forthcoming novels (just enough usually to whet the appetites of all those in attendance), and then answer a few questions from guest interviewers.It’s become a national thing now, and thus far to date I’m flattered to have been asked to partake in these events in Carlisle, Skipton and Manchester. But it’s probably inevitable that the WIGAN NOIR events are closest to my heart, as they happen in my home-town.

Organised by fellow author, the indefatigable Malcolm Hollindrake, these have been very successful occasions thus far, often selling out well in advance. They tick all the usual boxes: the industrial or post-industrial urban atmosphere that often goes with Noir fiction, the bar-room environment, the tough prose with which the audience are invariably assailed. But also the impressive names that have so far been attracted.

This year is no different in that regard. Again, I’m honoured to be sharing a platform with such illustrious northern writers as Caroline England, RC Bridgestock, Dale Brendan Hyde and Nick Oldham.

Unfortunately, I’m delivering this bit of promotion rather late in the day, as the event happens tonight at the Old Courts Courtroom in Wigan (don’t worry, there are several bars), commencing 7pm, with tickets £3 in advance or £4 on the door).

Unfortunately, I’m delivering this bit of promotion rather late in the day, as the event happens tonight at the Old Courts Courtroom in Wigan (don’t worry, there are several bars), commencing 7pm, with tickets £3 in advance or £4 on the door).For my own part, I’ll be taking the opportunity to read from my new novella, SEASON OF MIST , which sees an industrial Lancashire town in the 1970s, Ashburn, living in terror of a serial child-killer, though one particular group of youngsters are enthralled by a local legend of the autumn, which lays the blame firmly at the bloodied feet of an evil spirit called Red Clogs …

This will be a fairly apt choice, I feel, as Ashburn is basically a thinly-veiled Wigan, though it’s the Wigan of my youth – 1974 – rather than the Wigan of today. More than a few will remember it, I’m sure.

Again, I realise this is late notice, but hopefully not too late. Looking forward to seeing some of you there.

And now …

GALLERIES OF DARKNESS – Week 3

Those who’ve checked in with this blog over the last two weeks should be well aware that I’m currently in the middle of a month-long feature concerning artists (painters, illustrators, photographers and such), who have dipped into the ultimate darkness.

In short, each Thursday during October I’ll be posting a different gallery of chilling images as produced by some masters and mistresses of the visual nightmare. As I announced at the start of this month, there’ll be 100 in total, the final 20 to jar your world on Thursday October 31, a date which otherwise needs no introduction. (And even then, trust me, I’ll only have scratched the surface – there is a vast sea of wonderfully disturbing artwork out there).

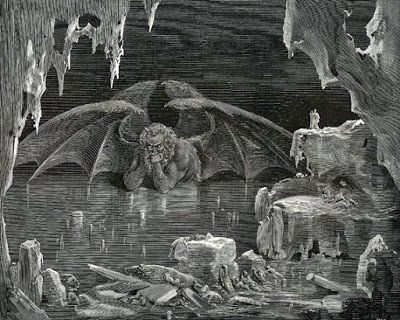

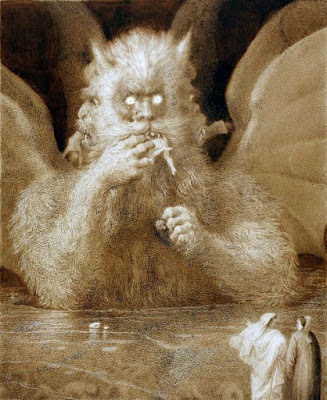

We open today’s blog with the eye-popping Lucifero by Francesco Scaramuzza (was this the model for the monster in Night of the Demon , or what?). But this was drawn as part of Scaramuzza’s monumental illustration of Dante’s Divine Comedy , which took him most of the 1820s to complete, and mainly this month I’m looking to feature more contemporary works, if for no other reason than it should hopefully introduce viewers to some dark artists they perhaps haven’t heard about previously.

I make no apologies for the fact that I don’t talk about these artists in any specific or educational detail. Firstly, I’m not qualified to do that, but as you’ll see from their intricate skills and subtextual immensity, there is way more to be said and debated than I could ever fit in here anyway. However, in most cases you can follow the links, and they will lead you through to much fuller information and, sometimes, online shops for prints, originals and the like.

One final warning: I’ve chosen nothing here simply because it is revolting. To me horror is about frightening its audience not making it sick. But despite that, these maestros of the darkest arts have some pretty harrowing dreams, and when it comes to recreating them for others, they do NOT hold back.

Here we go …

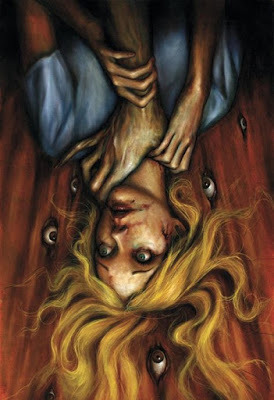

1. GIUM TIO ZARRALUKI

2. MAXIM VEREHIN

3. PLACIDO MERINO

4. ZAKURO AOYAMA

5. ANDREA KOWCH

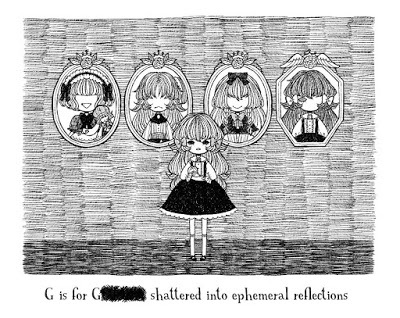

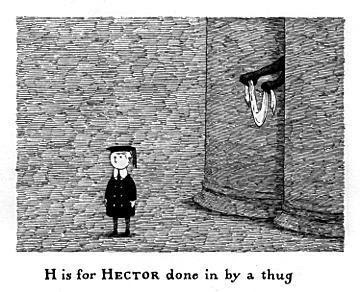

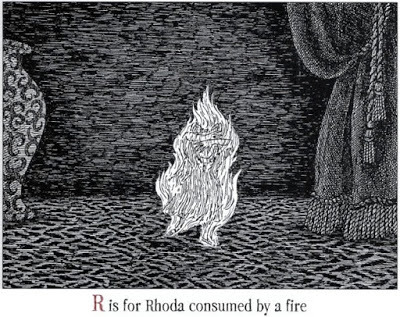

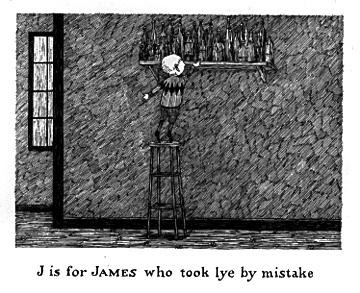

6. CHET ZAR

7. JAKUB ROZALSKI

8. KEITH THOMPSON

9. SABBAS APTERUS

10. VALIN MATHEISS

11. EDWARD GOREY

12. CHRISTIAN REX VAN MINNEN

13. MICHAEL WHELAN

14. GELIY KORZHEV

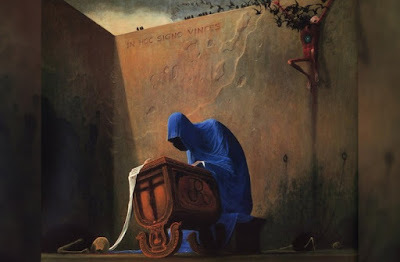

15. NEIL WILLIAMS

16. OTTO DIX

17. RAMSES MELENDEZ

18. STEPHAN KOIDL

19. ESAO EDWARDS

20. HARUMI HIRONAKA

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE ICE LANDS

THE ICE LANDS by Steinar Bragi (2011)

In the aftermath of Iceland’s financial collapse, two young couples and dyed-in-the-wool townies, Hrafn, Vigdis, Anna and Egill, ostensibly friends though there are many strains in their relationships, take a road-trip into their country’s barren, cinder-strewn interior. They have half a mind to check out the unique natural environment, and maybe photograph some glaciers while they are there, though the reality, one suspects, is that they are simply trying to escape from personal pasts that have gone badly awry.

The couples themselves are not entirely happy with each other. They have strong sexual bonds, we come to learn, but the two men, having lost money during the recent crisis, are depressed and struggling, Egill slipping into alcoholism, Hrafn trying to make up his losses by selling drugs. In contrast, the two girls, who perhaps having led worthier professional lives, were less affected by the disaster but now are required to tolerate their menfolk’s misery and cynicism.

If this isn’t difficulty enough, the road-trip itself goes chaotically wrong.

It is out in the middle of nowhere when the travellers are engulfed in an almost unnatural fog, skidding off the road, hitting the outer wall of a crude, rock-built cabin and writing their car off in the process. The cabin’s two occupants, a strange old woman and her even older and infinitely stranger husband, come out to assist and bring the shaken foursome indoors – but there is an air of panic about this, and once everyone is inside, the weird duo promptly sets about barring every door and window.

And from here, the mysteries really begin to flow.

The old couple clearly were not impoverished once but evidently are now. More to the point, their isolated farm is all but a ruin, and surely cannot provide from the arid lands surrounding it. The twosome offers a refuge for their unwilling guests, but are generally non-communicative. For example, they give no explanation for the remains of slaughtered animals which seem to litter the vicinity of their wind-battered stead. Likewise, when Hrafn, Vigdis, Anna and Egill try to get their bearings by exploring the area, they come across the remnants of a village which now lies empty and gutted, with no trace of its former occupants but a palpable air of menace; and as before, no coherent explanation is forthcoming from the elderly couple.

The stranded foursome makes several attempts to get back to civilisation, but events conspire to thwart them. Increasingly, we feel – to our incredulity – they are settling here. And this is despite the legends of the Icelandic interior, which are really quite disturbing, as harsh a terrain as you could find anywhere, nothing but rocks and dirt stretching to every horizon, and some weather from Hell, including a tumultuous and prolonged grit-storm.

Soon, they are treating the farmhouse as their own and virtually ignoring its actual owners, who, oddly, seem to accept this, though deep down, we suspect, they know something our four hapless heroes don’t. It is certainly the case that Hrafn, Vigdis, Anna and Egill spend far too much time waging their own petty wars against each other, brooding on their past failures and taking it on themselves to investigate the deep interior of the cabin – another internal wasteland! – to notice that something very unpleasant is waiting outside …

If books were to be awarded marks for strangeness, then The Ice Lands would be up there with the best of them. Because this is one weird tale, and sorry though I am to admit it, I don’t necessarily mean this in a good way.

To counter that, I wouldn’t say that I found this novel disappointing – it’s an engrossing read, centred around an intriguing mystery – but I did find it dissatisfying. That possibly owes more to the way it was sold, at least in the English language version, than it does to the author’s original intention. In what must be considered a golden age of Nordic crime thrillers, and amid a growing awareness of Nordic horror, it was maybe a bit cheeky of the various blurbsters to pitch The Ice Lands as a tale of darkness and dread. I mean, it is a tale of darkness and dread, but it’s also a lot more than that … we quickly reach the stage, for example, where the narrative itself becomes less important than its subtext.

It’s beautifully written, the awfulness of the desolate locale handsomely described. As you’d expect from a poet, Steinar Bragi can certainly create stark and lasting imagery. But despite this, and despite its enthralling opening, The Ice Lands is not so much a story about four people in peril as much as it is an assessment of Iceland, both the country and the people, and where they stand in the turbulent world of today.

First of all, we have this scenic and yet near-prehistoric landscape, an unforgiving volcanic topography on which only the toughest and most ruthless creatures could ever eke out a living. It is soulless, merciless, a directionless wilderness that seems to go on forever, an illusion (if it is an illusion!), which only intensifies under the horrific Arctic weather, which alternately freezes and fogs the tired foursome stranded in the midst of it.

If that isn’t message enough that this is potentially a bad place, this inner desert is littered with the near-unrecognisable ruins of those who didn’t make it: animals reduced to bones and carrion, human habitations so long abandoned and weather-worn that it’s impossible to tell who once lived here or why they left.

In addition, the undercurrents to all this are those terrible legends of the Scandinavian far north. Trolls, kobolds and other goblin types abound in Icelandic folklore, but you learn at an early stage in The Ice Lands that these are not the cute fairies of English back-garden tradition. Instead, they are malign powers who resent the intrusion of modern man with such venom that they will kill, kidnap and maim in response. (It’s probably worth mentioning that the folkloric references with which Steinar Bragi peppers his book are among its creepiest passages, depicting some extremes of supernatural evil, so it’s scarcely surprising that the country’s bleak interior was a region that travellers sought to avoid in earlier times).

Then, on top of this, we have our main cast, a thirty-something foursome, all of them damaged, distressed and wearied by their experience of modern urban life.

Bragi has been accused of oversimplifying things here, by opting for a crude form of political correctness. I don’t entirely agree, though I can see where the argument has come from.

Hfran and Egill, the men, are basically idiots. Having played the markets in empty-headed fashion during Iceland’s economic boom of the early 2000s, only to crash and burn during the banking collapse of 2008 – to which disaster they have responded in the most boorish way possible, Egill is now a drunk, Hrafn a criminal. It’s almost as if the author is pointing out what he considers to be a characteristic male response to a crisis: i.e. ‘If I personally must fail, then I will damage everything around me en route’. In sharp contrast, the two women, Vigdis and Anna, a journalist and a therapist respectively, are harder workers and more altruistic in their worldview – which of course would be laudable, except that neither of them seems willing or able to separate herself from her worthless other half, plus they each display their own irritating follies, and so they themselves are not beyond criticism.

Overall though, I think the book’s characterisation is the bit where, for me, The Ice Lands loses a little of its power.

Hrafn, Vigdis, Anna and Egill are cyphers or exemplars, stereotypes with a purpose rather than individual personalities. They each come with an awful lot of back-story, though this feels forced, in my view, making them more like fictional characters than real people. It doesn’t help, either, that their dialogue sounds stilted, their arguments are unconvincing, their sex scenes feel contrived and their response – or lack of such – to disturbing weirdness (not to say terrifying threats), jars badly even in a tale which is only superficially a horror story.

I wouldn’t say this killed my interest in the book, but it was something of a distraction (particularly the latter point).

All this said, it wouldn’t be true to say that there isn’t something genuinely eerie and affecting about The Ice Lands . Okay, it’s not a thriller in the conventional sense, and the events leading towards the end of the book are disconcertingly violent and horrible, even if they are a tad puzzling – I struggled to solve the mystery, unfortunately, but that may just be me – but there is something of Robert Aickman and even MR James in the actual setting. This horrible old farmhouse, with all its hidden depths, which, piece by piece, are uncovered and investigated, is deeply discomforting. Why is it here? What purpose did it ever serve in this drear wasteland? Who exactly are its frail and yet ever-watchful custodians? Why do they bar it at night? What terrible thing killed the animals outside? What about the ruined village, etc …?

You won’t need a vivid imagination to realise at an early stage that none of this is going to culminate in a happy ending.

If you’re like me, you’ll probably feel frustrated by some aspects of The Ice Lands , but you’ll also be sufficiently intrigued by all these many uncanny curiosities to stick with it to the end, and if you’re not put off by the increasing incidents of gore and are not dissuaded by an ever-greater atmosphere of approaching doom – you’ll keep going and will draw something out of it even if you’re not entirely sure what that is.

I don’t think I can confidently recommend The Ice Lands to traditionally-minded thriller or horror fans, but it’s definitely worth checking out if you prefer your fiction to come from the dark side.

It won’t be easy casting this one, as my knowledge of Scandinavian actors is not as broad as it could be, let alone my knowledge of Icelandic-born actors, so it’s fortunate this is just a bit of fun. Anyway, here we go: if The Ice Landsever makes it to film or TV, and what an interesting project that would be, here are my picks:

Hrafn - Stefán Karl StefánssonVigdis - Ágústa Eva Erlendsdóttir Anna - Anita Briem Egill - Gísli Örn Garðarsson

Published on October 17, 2019 00:55

October 10, 2019

Galleries of darkness, for October - Week 2

Welcome to Week 2 of my OCTOBER GALLERIES OF DARKNESS. Yet again, I’ll be looking at 20 artists – painters, book illustrators, game designers etc – who’ve hit us over the years with some truly terrifying visuals.

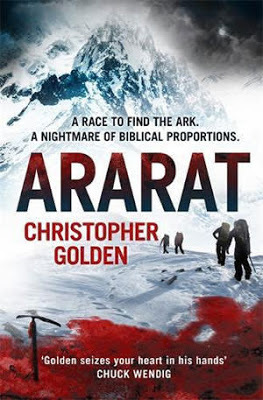

In addition, because the focus yet again this week is on horror, I’ll be offering another of my detailed reviews and discussions, today concerning Christopher Golden’s tale of mountain-top terror ARARAT. If you like ancient mysteries brought into the modern age, if you like the occult, if you like horn-headed demonic nightmares, then this one could definitely be for you.

If you’re only here for the ARARAT discussion, you’ll find it, as always, at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Just zoom on down and check it out. However, if you’ve got a bit more time, there are a couple of other things you might be interested in first. Not just our latest Gallery of Darkness , which you’ll find below, but this too …

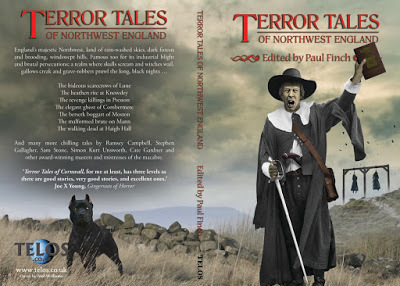

TERROR TALES OF NORTHWEST ENGLAND

I’ve been promoting the hell out of this book for quite a while; the last six or seven months by my reckoning. But now, at last, I can happily announce that it’s available for acquisition both as ebook and paperback. Just follow the link and delve deep into the urban and rural mythology of Northwest England. That means Lancashire boggarts, Manchester monstrosities and general-purpose madness, mayhem and menace from the backstreets of Liverpool and the deceptively quiet country lanes of leafy Cheshire.

Treat yourself to some cracking horror fiction from the likes of Stephen Gallagher, Ramsey Campbell, Cate Gardner, Simon Kurt Unsworth, Sam Stone, and even my good self. Yes, though I’m always a bit pink-cheeked when it comes to self-promotion, I must admit that we close off this collection with my previously unpublished novella, The Upper Tier , which was written for and performed live at a special Ghost Story Night at Haigh Hall in Wigan, back in 2011. And yes, it’s all about that infamous haunted mansion that still sits in its own green and overgrown hinterland in the heart of a borough once notorious for its smoke and industry, and which is rightly regarded as ‘the Borley Rectory of the North’.

And now, onto the visual chills …

GALLERIES OF DARKNESS - Week Two

I won’t waste your time with a big preamble this week. Suffice to say that those who were around at the beginning of the month will remember my announcement that throughout October I’ll be treating you each Thursday to a gallery of work produced by 20 artists who have dabbled in the darkness (taking us all the way through to Halloween, and that even then, with 100 of them in total, I’d only be scratching the surface).

The painting at the top of today’s blog hails from distant antiquity, Medusa by Peter Paul Rubens (1618), though for the most part in this series I’ll be concentrating on more contemporary works, mainly because that should guarantee there’ll be a few that you’re not yet aware of.

I won’t be talking about these individual artists in any details, mostly because I’m not qualified to, but also because I haven’t got the space or time to do them justice. On this occasion, I’ll just let the pictures do the talking. But follow the links and, wherever possible, it will divert you through to the artists’ own web-pages, their online shops, etc.

Quick warning: there is nothing here that is simply disgusting; quite often it’s horror of the more sophisticated sort. But even so, these masters and mistresses of the macabre do NOT hold back.

Enjoy …

1. ADAM BURKE

2. DAN PEACOCK

3. FRANCES CASTLE

4. JAMES ENSOR

5. JOHN KENN MORTENSEN

6. OLEG VDOVENKO

7. RAY CAESAR

8. TETSUYA ISHIDA

9. ADRIAN BORDA

10. BOB EGGLETON

11. DANIEL JIMINEZ VILLALBA

12. FRANCISCO GOYA (specifically, the Black Paintings)

13. JEFF SIMPSON

14. LAURIE LIPTON

15. OTTO RAPP

16. RICH JOHNSON

17. VERGVOKTRE

18. ADRIAN SMITH

19. BOM.K

20. DARIUSZ ZAWADZKI

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

ARARAT

ARARAT by Christopher Golden (2017)

Life-partners and professional adventurers, Meryam Karga and Adam Holzer, think they may have stumbled on the find of a lifetime when an avalanche at the top of Turkey’s Mount Ararat exposes a cave in which an ancient timber craft is lodged. Ararat, of course, is one of the most famous mountains on Earth for reasons that date back almost to the dawn of human history – long has it been rumoured that this was the last resting place of Noah’s Ark.

Determined to claim this incredible prize for their own, Meryam and Adam make the arduous trek to the upper slopes of the wintry mountain in company with a handpicked team of assistants. But inevitably, they aren’t going to have things all their own way.

Of their two guides, Feyiz is fine, but the older one, Hakan, is an awkward, aggressive bully who openly dislikes Meryam because he considers her to be a lapsed Moslem. Then we have the rest of the team, a hotchpotch of scholars, archaeologists and student film-makers, and these don’t make for easy bedfellows either. Catholic priest and ancient languages expert, Father Hughes, does not get on with Professor Olivieri; it’s mainly a case of professional rivalry, but it still threatens the work. The Turkish authorities are present too, and though on the whole cooperative, they are suspicious of Father Hughes, who they worry will try to turn this into a ‘Christian achievement’.

A quieter presence is the mission’s action-man, Ben Walker. He arrives in company with UN observer, Kim Seong, and though he ostensibly represents the US National Science Foundation, in fact he is an American defence operative whose main role is to establish if there is anything on top of Mount Ararat that might be useful to his government. Walker is experienced at this sort of thing (very experienced, it soon transpires), but he knows when to play it low-key; at first, he is all things to all men, but it isn’t long before he too has identified weaknesses in the chain of command which he might be able to exploit.

As if all these vying interests don’t cause enough problems, the weather up there in the high peaks is extremely hazardous, bitterly cold wind and intense snowstorms sweeping the desolate ridges. But initially, the find makes all the hardships and complexities of reaching it worthwhile. The Ark, for that is what it appears to be, has all but burrowed its way into the mountain, its interior accessible only by a relatively small opening. But once you get inside there, it’s a wondrous structure, a vast ocean-going vessel of a sort that no-one thought the pre-Biblical world was capable of producing. It also dates correctly and is a virtual treasure trove in terms of the human bones, pottery and ancient writings adorning its lower decks.

The question as to whether this vast object could actually be Noah’s Ark is the key. No one on the mission believes the Noah story word-for-word, but there is a general acceptance that some tribal elder, possibly named Noah, took his family and some livestock and embarked on a hastily-built craft to ride out a sudden flood. But what kind of cataclysm might have left the boat high and dry at the top of a 16,000-foot mountain?

And then an even bigger and much more unsettling question arises.

Whose is the mummified cadaver the team discover in an eerie, glyph-covered coffin deep in the heart of the fossilised craft?

And why does it apparently have horns on its head?

A gawing fear grips the intrepid band. No one seriously wants to contemplate that this might be the relic of an ancient demon, but then stories of the Great Flood concern a race of evil beings who, in Genesis, were spawned on the Earth by fallen angels, and who in due course became the targets of God’s wrath, hence the fast-rising water.

Could there be a kernel of truth in that myth? Could this be the desiccated remnant of one such creature, which somehow sneaked aboard?

Only when the killings start, individual members of the team butchered with climbing tools, and/or thrown down the mountainside to freeze, does this fear morph into utter terror.

Debates rage on as to the nature of the thing in the sarcophagus. Is it what they suspect? Could it be wielding a malign influence? Or do they simply have a madman in their midst?

The obvious solution is to get the hell out of there, abandon the Ark and the sarcophagus, and stumble back down the mountainside to civilisation. But the weather is getting worse. The worn-out archaeologists are now trapped in this hellish place, and a very real malevolence is spreading among them …

All kinds of influences are visible in this fascinating and intense chiller from US author, Chris Golden, quite a few of them filmic. There is certainly a bit of The Thing in there, hints of The Exorcist , and more than a dollop of Raiders of the Lost Ark (a different Ark this time, of course). But there is nothing unusual in this in the modern age.

Certain book genres seem to have blended together in recent times, to give us a whole new range of thriller/horror/adventure novels, invariably set in exotic locations and underwritten by mysteries from the ancient religious world.

It often makes for an intriguing mix, but I’m particularly impressed on this occasion that Golden has taken it all a step further by upgrading the fear factor to an extreme degree.

We readers are left in no doubt that the Ark discovered here is an amazing thing, venerable and mystifying beyond imagining, and very possibly an indicator that cosmic powers have controlled the events on Earth from time immemorial, and that good and evil once held sentient forms, and maybe still do. But while these huge metaphysical issues pervade Ararat , the author doesn’t forget to entertain us as well.

From the moment, the terrible husk is discovered inside the dank, fire-lit interior of this long-forgotten hulk, the atmosphere changes. Everything that once seemed miraculous now seems deeply ominous. What formerly felt like a hidden door which, should our heroes open it, would shed light upon a distant, semi-mythical past, is a door they must at all costs keep closed for fear of what it might admit.

The author channels these big concepts through his characters, amplifying them in the process without hitting us over the head with them.

Meryam and Adam’s team are robust sorts, outdoor types who’ve managed to make it to the top of the world despite inconceivable obstacles. For the most part, they are scientists and cultured intellectuals, who don’t believe in angels and demons, but not long after you get into this novel, lack of spiritual belief starts to feel like a weakness rather than a strength. If you’re purely a rationalist, how can you cope mentally with supernatural revelations like these?

And it’s not as if all is hunky dory in the group anyway. For various reasons, Adam and Meryam have found themselves drawing apart during this expedition. For one thing, Adam resents that Meryam often confides in the handsome young guide, Feyiz, while he himself is drawn to the beautiful camera-girl, Calliope Shaw. Then there are the religious differences; Golden handles these particularly well, not overdoing the issues that arise when Jews, Moslems and Christians are required to work together, but not pretending that basic mistrust doesn’t exist – and of course allowing it to become a major problem when the horror in the casket is found.

How do you tackle such a being? Whose religious explanation do you believe? Whose religious weaponry do you invoke?

There is a political dimension too. The Turks are paranoid about the American, Ben Walker’s presence, which you can hardly blame them for as he’s so secretive about his real purpose here, while Hakan the hardliner – and he’s not the only one! – increasingly feels that all foreigners, particularly irreligious modernists like these, should be barred from what is clearly a sacred site.

In short, everything that could be going wrong is soon going wrong, and at a time when this small microcosm of humanity is pitted against what is potentially the deadliest foe mankind has faced in millennia – and this time, it’s safe to say, God won’t be intervening to save everyone with a cataclysmic flood.

Ararat is a rousing 21st century thriller, an intense action-horror both claustrophobic in tone and epic in scale. At the same time, it’s disconcertingly grown-up in terms of the questions it raises … mainly because there are no easy answers (if any). A thoroughly compelling read.

And now, I’ll embarrass myself again by attempting to cast Ararat should Hollywood or HBO come knocking at Chris Golden’s door. It’s often drawn to my attention that in playing this game with each review, I sometimes overlook the fact that adaptations are already in the works. Apologies if that is the case here – in truth, I’d be disappointed and surprised if it wasn’t – but I’m still having a go. Remember, the big difference between my casting sessions and those of the big studios is that in my case money is no object (heh heh heh).

Ben Walker – Adrien BrodyMeryam Karga – Ahu TurkpenceAdam Holzer – David SchwimmerKim Seong – Dianne DoanFeyiz – Cansel ElkinHakan – Serhan YavasFr. Cornelius Hughes – Michael GambonProf. Armando Olivieri – Giancarlo GianniniCalliope Shaw – Hayley Atwell

Published on October 10, 2019 00:33

October 3, 2019

Galleries of darkness, for October - Week 1

Okay, something a bit different now that we’re into the month of October. It’s a time of year that’s always associated with spookiness. Regular readers of this column will probably think: “So what’s different there? Everything you talk about on here is spooky or scary or dark or disturbing.”

Well, yes … that’s true. But rather than blathering on throughout October about books, films or whatever I happen to be writing at the time, and doing my level best to persuade you that it’s the scariest thing since His Satanic Majesty’s escape from Hell, I thought I’d take a more visual approach this month – and hit you where it frightens the most, showcasing artwork rather than verbiage.

I’ll also this month, in my review section – again, because it’s October – be looking exclusively at horror novels or anthologies, starting today with John Farris’s legendary ALL HEADS TURN WHEN THE HUNT GOES BY.

Now, if the John Farris piece is all you’re here for, no problem. As is usually the case, you can scoot on down to the lower end of today’s blog, where you’ll find the review and discussion in the ‘Thrillers, Chillers’ section. However, if you’re interested in seeing what else I’ve got to offer first, then stick around and check out some …

Dark Arts

Dark ArtsNot many people know this, but I’m actually a lover of fine art. I adorn my home with paintings (whenever I can afford them), and I’m never more relaxed than when I’m wandering around an art gallery with plenty of time to absorb and enjoy the treats on offer there. (I don’t go as much for sculpture; sadly, that wouldn’t be possible in our house, as we have two whirlwind springer spaniels with a lifelong mission to demolish every ornament in their path).

When I say I’m a lover of the arts, you may assume that, because I’m also a scare-meister when it comes to my writing and reading, that this means I’m mainly interested in artists who specialise in the grim and ghoulish. Well … that’s not true. I love quality paintings, whatever the mood they evoke. That said, for our purposes this month – October, remember, that spookiest time of the year! – I’m going to be focussing on those artists who’ve dabbled in the darkness.

I’ll thus be hitting you each Thursday this month with a gallery of 20 painters or illustrators, offering several samples in each case of their more twisted imaginings, the whole thing culminating on Halloween itself.

I’ll thus be hitting you each Thursday this month with a gallery of 20 painters or illustrators, offering several samples in each case of their more twisted imaginings, the whole thing culminating on Halloween itself.Now, before we get going, I should point out that, even featuring 20 a week – which overall this month gives us a nice round 100 – I’ll barely be scratching the surface of this subject. So many visual creators have thrown nightmares onto canvas, and not just those of a recent vintage.

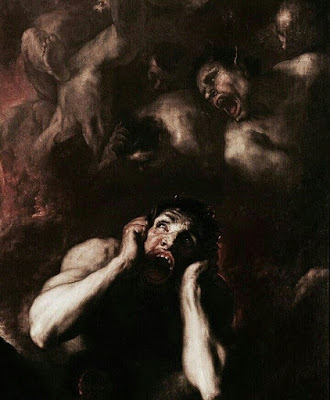

Check out the image at the top of this column: a close detail from Fall of the Rebel Angels by Luca Giordano, created in 1666. Have you ever seen such a depiction of horror and terror? No less disturbing, you’ll also see in this opening section (in descending order) Death and the Miser by Hieronymus Bosch (1494), Saturn Devouring His Son by Peter Paul Rubens (1636) and Flaying of Marysas by Titian (1570).

I won’t wax lyrical on the subject of these old masters. Firstly, because I’m not qualified to do so – I'm an art buff, not an expert. Secondly, because they largely speak for themselves.

That’s also the approach I’ll be taking with the weekly galleries I’ll be presenting to you. In nearly all cases I’ve done my research but haven’t learned anything like enough about the painters themselves to discuss them. In some cases, I don’t even know the names and dates of the pictures themselves; that’s the problem with the Internet – you find this great stuff floating around online but finding credits and background information is much harder.

That’s also the approach I’ll be taking with the weekly galleries I’ll be presenting to you. In nearly all cases I’ve done my research but haven’t learned anything like enough about the painters themselves to discuss them. In some cases, I don’t even know the names and dates of the pictures themselves; that’s the problem with the Internet – you find this great stuff floating around online but finding credits and background information is much harder.However, in each case I’ve created a link, which will take you through to that particular artist’s page or site, from where you can hopefully learn all you need to know, and maybe even buy some prints. (You’ll notice that most of these artists are current, so it may even be possible to acquire some originals).

So, without further ado, I’ll stop gabbling and get on with our …

GALLERIES OF DARKNESS – Week One

As I say, don’t be looking for detailed info on here; I simply haven’t got it – just follow the links and with luck that will be sufficient. (And here’s a quick, last-minute WARNING: though I’ve consciously tried to avoid anything that is simply revolting, I’ve gone all out for the disturbing and terrifying. So, be aware, these artists do NOT hold back).

1. ELIRAN KANTOR

2. ASYA YORDANOVA

3. BORIS GROH

4. DAVE KENDALL

5. JOSHUA HOFFINE

6. PAUL CAMPION

7. RACHAEL BRIDGE

8. SETH SIRO

9. LES EDWARDS

9. SAFIR RIFAS

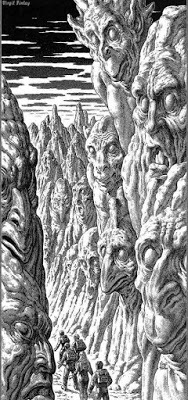

10. VIRGIL FINLAY

11. BUDDY McCUE

12. AERON ALFREY

13. REGGIE OLIVER

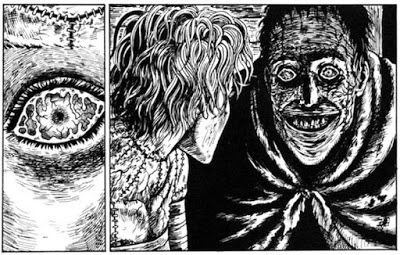

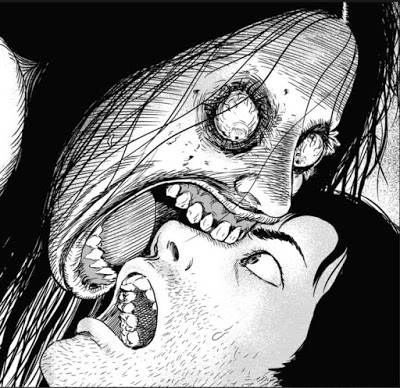

14. JUNJI ITO

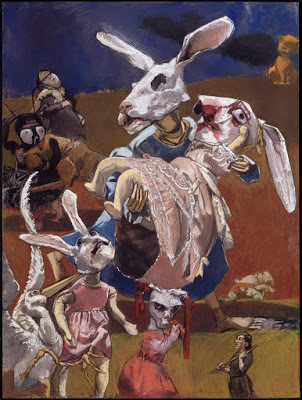

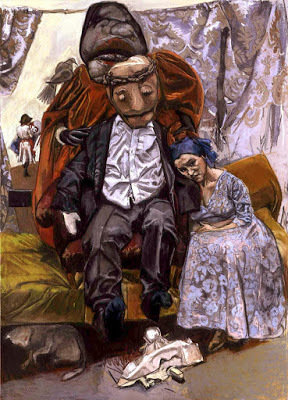

15. PAULA REGO

16. SANTIAGO CARUSO

17. WAYNE BARLOWE

18. KARL PERSSON

19. MARK RYDEN

20. PIOTR JABLONSKI

Part II follows next Thursday ...

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

ALL HEADS TURN WHEN THE HUNT GOES BY

ALL HEADS TURN WHEN THE HUNT GOES BY

by John Farris (1977)

In 1942, officer and gentleman, Charles ‘Champ’ Bradwin, takes leave from his unit and heads home to Arkansas to attend his younger brother, cadet officer Clipper’s wedding. It is a grand occasion. Everyone who is anyone is present; most members of the aristocratic Bradwin family, including demagogic patriarch, Boss, though not oldest brother, Beau, who left the district many years earlier. But it still ends in disaster, because when the church bell inexplicably tolls of its own accord, Clipper goes mad, attacking the congregation with his dress sabre, slaughtering, among others, his wife-to-be and his father, before killing himself.

Stunned and helpless, the family retreat to Dasheroons, their vast rural estate, but there is no solace to be found there. Both Champ and Nhora, Boss’s young and beautiful French wife (his third, in fact), are lost for an explanation, while Champ’s wife, Nancy – whom Clipper particularly tried to slay, but who survived – is left almost comatose by the experience. The staff on the estate, Boss’s loyal, longstanding man-servant, Hackaliah, and his educated but surly son, Tyrone, are equally horrified and bemused. Detailed examination of Clipper’s background reveals a hitherto concealed lifestyle of predatory sexual behaviour, but there is no indication of the homicidal personality that revealed itself during the wedding.

With no option, but shell-shocked before he even gets to the battlefield, Champ must now return to his unit and fight the war, while Nhora takes charge of the palatial estate despite a strange undercurrent of hostility towards her.

Needless to say, the terror and the misery go on. Champ is dispatched to the Pacific, where his company is decimated in heavy fighting with the Japanese, and he himself suffers an horrific throat-wound (though this happens in weird, dreamlike circumstances, during which his assailant looks remarkably like a decayed version of his dead brother, Clipper). When Champ finally returns home, a shadow of the man he was, he is in the company of a doctor the Bradwin family have never met before, an Englishman called Jackson Holley, whose credentials are very good, at least on paper – but who in actual fact has a fabricated pedigree because he never completed his medical training and is now on the run from his own peculiar demons.

But this is actually a big event, because with the arrival of Holley, two cursed families have finally come together.

It seems that the wedding butchery is only one tragedy in the history of the Bradwin family; there have been others in the past, dating back to an even more savage occasion when Boss, not exactly a white supremacist but still an icon of southern gentry entitlement, led violent retaliation against a protest by local black farmers, which turned into a massacre (as one character comments, Dasheroons “is built on the bodies and blood of Africans”) – but the Holleys too have stumbled from one misfortune to the next.

Jackson Holley is lucky to be alive, as his youth, spent at a Congo mission hospital where his father was a voluntary medic, brought him face to face with all kinds of hardships and horrors: heat, illness, bizarre apparitions, and a cannibalistic tribe so in thrall to the aggressive snake goddess, Ai-da Wedo, that they were prepared to sew the seeds of their own eventual destruction by following her warlike path rather than living in peace with the ever-more covetous colonial powers.

A major coincidence now occurs in the story (at least, it seems that way at first, though all will be revealed in due course). Because beautiful widow, Nhora, also spent her youth in that steamy jungle realm – at the time classified as French Equatorial Africa – where she was kidnapped as a child by the same ferocious tribesmen. Perhaps inevitably, she and Holley hit it off when they meet – in fact, it is virtually love (and lust!) at first sight – but even though the Englishman has brought the family’s last surviving son safe home again, he doesn’t feel entirely safe; there are many menacing mysteries on the great southern estate.

What happened to Beau Bradwin?; did he really leave because he fell out with his father over the brutal methods Boss displayed in his younger days? And if so, where did he leave to? Is it possible that Tyrone, who clearly does not get on with his own father, Hackaliah, might actually have been sired by Boss, and in which case does he have his own agenda? Why is a grizzled outlaw known only as Early Boy hanging around on the plantation’s fringes? What dark power keeps so many of the family’s black servants in such a state of fear? Could the secret of all this evil lie in the apparent voodoo temple that Holley and Nhora discover in a nearby bayou?

The answers to all these questions, and others, will only be provided if Holley hangs around for once, and tries to work his way through the layers of mystery. Nhora may help him, or she may hinder him. But one thing is certain, when the truth finally emerges it will neither be palatable nor edifying. If we thought there was horror in the Bradwins’ and Holleys’ lives previously, we ain’t seen anything yet …