Paul Finch's Blog, page 12

June 24, 2018

Heck's timeline so far, career and love life

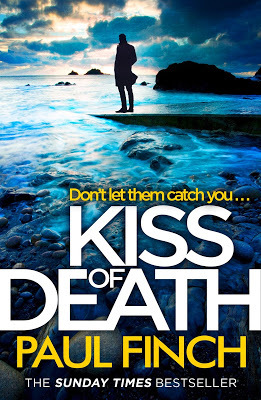

I’m going to be talking almost solely about my main cop character, Heck, this week. His background, the timeline of his life and career to date, and some of his forthcoming adventures, such as in the novel, KISS OF DEATH (out in August), and in the novella, DEATH’S DOOR (out next Friday, FREE, hence the unashamed advert just above).

But I say almost solely, because as usual, I will also be reviewing and discussing, in some considerable detail, another piece of dark fiction that I’ve recently read and enjoyed, and today, sticking with the murder detective theme, that’s going to be Tony Parsons’ very intriguing, London-set crime thriller, THE HANGING CLUB.

If you’re only here for the Parsons review, that’s fine. As is normally the way, you’ll find it at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Just skip on down there straight away. But if you can give me a minute or two, perhaps you’ll be interested in letting me take you through the Heck timeline.

Who he is

Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg is the star of six of my crime novels to date, with a seventh, KISS OF DEATH , due for publication on August 9 this year. He has also appeared in two novellas thus far, with a third, DEATH’S DOOR , due out, as already mentioned, next weekend.

I’ve already written a lot about the character, what kind of personality he is, where he gets his traits from, who in real life – if anyone – influenced his creation. But it’s recently occurred to me – and I only realised this when someone asked me the other day – that I’ve never sat down and tabulated his chronological timeline. I’ve never listed the order of events in his home-life and career that have led up to the place where we are now.

I’ve already written a lot about the character, what kind of personality he is, where he gets his traits from, who in real life – if anyone – influenced his creation. But it’s recently occurred to me – and I only realised this when someone asked me the other day – that I’ve never sat down and tabulated his chronological timeline. I’ve never listed the order of events in his home-life and career that have led up to the place where we are now.On reflection, it quickly became apparent that, were I to do this, it would serve as an ideal reference point for me as well as for my readers. I too get lost in the woods sometimes, when I’m trying who remember Heck was with at such and such a time, what he was doing, where he was based, and so forth.

So here we are.

It’s only a thumbnail sketch, of course. I’ve not got the time or space to give you a chapter and verse biography. But here is the main order of developments in the life of Mark Heckenburg, from the moment of his birth to the commencement of KISS OF DEATH .

(But first, a quick warning: take some my dates and the like with a slight pinch of salt. That’s not because I’m unsure about them, it’s because when you’re writing a character who is part of a franchise, their natural ageing process can sometimes become inconvenient. Take James Bond, for instance. To us he’s Daniel Craig, aged somewhere in his mid 40s and still lean and fit, but if Bond was a real person who was born when Ian Fleming originally said he was, he’d now be in his late 80s and without doubt the oldest and most decrepit MI6 agent still in service. Now, obviously we don’t want that, so to us these paragons of fictional heroism must, at some point become, inexplicably but pleasingly ageless. We’re not at that stage with Heck yet, I’m glad to say, but just bear in mind – if he goes on and on into the distant future, there will come a time when we have to start playing fast and loose with ages, dates and so forth – but as I say, and I reiterate, that’s NOT the case at present).

Heck – the timeline

WARNING – if you’ve not read any of the Heck books yet but plan to, and you’d prefer an unfolding story, with information gradually emerging as you progress from volume to volume, then this timeline will definitely contain some SPOILERS …

Mark Heckenburg was born on January 9 1977 in Bradburn, a Lancashire coal-mining town on the northwest edge of the Greater Manchester conurbation. The third child of a factory worker, George Heckenburg and his wife, Mary, he had an older brother by three years, Tom, and an older sister by six, Dana.

Mark had a traditional working-class upbringing, the family never moving from their terraced house on Cranby Street, in the St Nathaniel’s quarter of Bradburn, a district known as the Old Town and centred around St Nathaniel’s Roman Catholic Church, which they attended every Sunday and where Mary Heckenburg’s younger brother, Pat McPhearson, was the parish priest.

Mark had a traditional working-class upbringing, the family never moving from their terraced house on Cranby Street, in the St Nathaniel’s quarter of Bradburn, a district known as the Old Town and centred around St Nathaniel’s Roman Catholic Church, which they attended every Sunday and where Mary Heckenburg’s younger brother, Pat McPhearson, was the parish priest.Another fixture in the Old Town was St Nathaniel’s Amateur Rugby League Club, where Mark excelled as a junior player, becoming a schoolboy superstar who was soon deemed good enough to turn professional. His teenage lifestyle came to reflect this, the swaggering youngster hanging out with a bunch of roughneck mates, who loved sport, drank lots of beer and chased the girls.

For all these reasons, George Heckenburg was deeply proud of his youngest son (even though Mark’s education was being neglected), regarding him as a true chip off the old block. George was less enamoured of the older boy, however. Tom, a hippyish metal-head, was studious initially, but threw it all away when he entered 6th form college, got into drugs, dropped out and turned to petty crime in order to feed his habit. All through this difficult time, George Heckenburg punished his eldest son in repeated, heavy-handed fashion, but failed to get him the professional help he needed.

The difficult situation deteriorated rapidly, until it finally turned into a disaster that would change all their lives permanently. It was 1992 and Mark was still only 15, when Tom, by now 18, was arrested on suspicion of being the Bradburn Granny Basher.

In short, a violent burglar had been attacking old people in their homes, stealing what few valuables they possessed, and beating them half to death in the process. Tom Heckenburg, a regular burglar of business premises – but NOT the Granny Basher – was framed for these crimes by a bent police team desperate to get a result, subsequently convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. A drug-addled weakling, he was simply unable to endure what followed, getting raped and assaulted repeatedly by fellow inmates, and eventually, later that year, taking his own life in the prison showers by slashing his wrists and groin.

In short, a violent burglar had been attacking old people in their homes, stealing what few valuables they possessed, and beating them half to death in the process. Tom Heckenburg, a regular burglar of business premises – but NOT the Granny Basher – was framed for these crimes by a bent police team desperate to get a result, subsequently convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. A drug-addled weakling, he was simply unable to endure what followed, getting raped and assaulted repeatedly by fellow inmates, and eventually, later that year, taking his own life in the prison showers by slashing his wrists and groin.The Heckenburg family were devastated, especially as a short time afterwards, the real Granny Basher was apprehended in the act of launching another vicious attack. It had a particularly damaging effect on George Heckenburg, who, riddled with guilt about his own inability to fix Tom’s problem, began to take it out on Mark. Once the apple of his father’s eye, Mark now became the victim of a rewritten history in which he had been the bad boy waster and Tom the family’s best hope, a terrible travesty which Dana resisted but Mark’s mother, the mousy Mary, simply went along with.

Eager to win his father round, Heck gave up playing rugby league, even though he was still only 16, and went to college to study for his A-levels. He got good grades, but it wasn’t enough. As far as his father was concerned, he was now the villain, and his brother had been a saint. In one terrible moment, George even went as far as to tell Mark that the wrong one of his two sons had died.

So, in 1995, on his 18th birthday, determined to have revenge against his father, Mark Heckenburg joined the Greater Manchester Police.

His family were obviously appalled. It was GMP who had framed Tom. It was GMP who later defended their actions so vigorously that, though the wronged family received compensation, none of the corrupt coppers involved in the case were brought to book. And now Heck had joined them. Even Dana, his older sister, who had sided with him against their father, considered this an unforgivable betrayal.

Mark was thrown out of the family home, and for a brief time, lived as a lodger with his uncle in the presbytery at St Nathaniel’s, but that couldn’t last long. His entire home town became a hostile zone for him, the word spreading widely among the local community what a traitor he was. Even though Mark, now a uniformed constable nicknamed Heck, worked 17 miles away in Salford, his life was becoming increasingly difficult.

It was around this time – it was 1997 and Heck was still only 20 – that he began catching the attention of his supervisors.

Check out the events of the novella,

A WANTED MAN

, in which Heck, during a night-shift from Hell, picks up the trail of a predatory rapist called ‘the Spider’ because he scales walls and climbs in through bedroom windows ...

Check out the events of the novella,

A WANTED MAN

, in which Heck, during a night-shift from Hell, picks up the trail of a predatory rapist called ‘the Spider’ because he scales walls and climbs in through bedroom windows ...Later that same year, even though he’d got himself a flat in Manchester, Heck decided that the proximity to his family was becoming intolerable. None of them would ever return his phone-calls, much less involve him in family events. But the original plan, which had been to resign once he’d punished his parents a little, was now put on hold, because ... rather unexpectedly, Heck had started to enjoy being a policeman, plus he was proving to be very good at it. He didn’t want to resign, and so, to get away from his family once and for all, he voluntarily transferred to the Metropolitan Police in London.

In the capital, Heck worked initially as a uniformed beat-officer in Kentish Town, but in 1998 joined CID, moving to Bethnal Green, where he came under the tutelage of the excellent and very maternal DI Gwen Straker. At the same time, he met this other incredible girl – Detective Constable Gemma Piper – who was his own age and who had also just moved out of the uniform branch. Gemma was standoffish at first, but gradually, as they worked together through a number of cases, Heck won her over – and by the year 2000 they’d become an item.

The events of Heck and Gemma’s first Christmas as boyfriend and girlfriend can be followed in the novella, BRIGHTLY SHONE THE MOON THAT NIGHT, which I posted in three installments on this blog on consecutive Fridays during December 2017. It all takes place one very snowy Christmas Eve, when the duo become concerned about a weird and rather murderous bunch of carol singers ...

Heck and Gemma continued working together and seeing each other, a relationship that in 2001 led them to set up home together in a rented flat in Finsbury Park. However, things were not entirely hunky dory. Gemma, a very efficient officer and a renowned straight bat was marked for promotion from an early age, whereas Heck’s more undisciplined approach to procedure and protocol often threatened to sink his career (and hers, she came to fear, if they stayed together). Heck was still a good cop, who got great results, but he was increasingly seen as a risk-taker and adventurer.

The strain this put on their relationship, even though they were now living together, can be seen next Friday, when the novella, DEATH’S DOOR, is published. In short, Heck becomes concerned when he learns that the new female occupant of a house that has long stood empty reports a prowler. This is because another woman was murdered in that same house only six years ago, and that very disturbing case was never solved ...

The strain this put on their relationship, even though they were now living together, can be seen next Friday, when the novella, DEATH’S DOOR, is published. In short, Heck becomes concerned when he learns that the new female occupant of a house that has long stood empty reports a prowler. This is because another woman was murdered in that same house only six years ago, and that very disturbing case was never solved ...While Heck and Gemma’s relationship continued to slowly unravel, any relationship remaining with his family at home completely evaporated when he learned that both his parents had died within a relatively short time-frame and that, at their request, he wasn’t informed until after they had been buried, thus preventing him from attending either of the funerals.

Hurt by this, and now at odds with almost the entirety of his home town, Heck pressed on with his career as a London cop, playing ever faster and looser with the rules, and taking ever greater risks. He and Gemma finally parted company in 2005, Gemma rocketing off into the upper echelons of London law enforcement through a series of impressive promotions, Heck continuing to slog it as a detective constable, though, as he would often say, he preferred being an investigator to being an administrator.

In this capacity, he did stints with the Burglary Squad and Robbery Squad in Tower Hamlets, before finally being promoted to sergeant and returning briefly to uniform in Rotherhithe, though he rejoined CID at the first opportunity, less than a year later in fact, taking up the post of detective sergeant at Brick Lane. Six months later, after yet more impressive results, he was joined the Murder Investigation Team in Lewisham, and two years later, in 2006, he transferred to the National Crime Group at New Scotland Yard to work in the Serial Crimes Unit.

The National Crime Group was an elite and specialist police force, entirely separate from the Met, which was FBI-like in its remit, and covered all the police force areas of England and Wales. But it was with some consternation that Heck found Gemma had got to NCG ahead of him, and now, as a detective superintendent, was actual commander of the Serial Crimes Unit.

The twosome were thus reunited, but things were very different between them. In a ‘fire and water’ relationship, they commenced working their way through a series of complex and often very distressing murder cases.

This, of course, is where we pick up with the Heck novels.

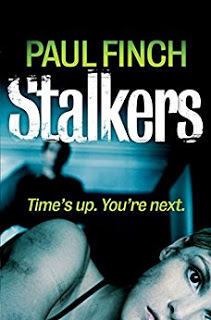

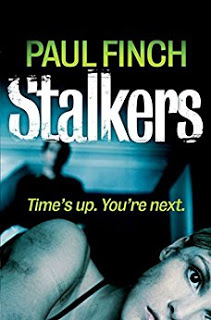

In

STALKERS

, Heck and Gemma, both now 36, find themselves on the trail of the Nice Guys Club, a secretive crime syndicate who abduct female victims to order and provide secure places where their clients can rape and abuse them, the club then disposing of all the evidence afterwards, including the victims ...

In

STALKERS

, Heck and Gemma, both now 36, find themselves on the trail of the Nice Guys Club, a secretive crime syndicate who abduct female victims to order and provide secure places where their clients can rape and abuse them, the club then disposing of all the evidence afterwards, including the victims ...In SACRIFICE , a series of brutal and elaborate murders appear to coincide with special feast days in the calendar, which it soon becomes apparent are human sacrifices based on ancient and obscure beliefs ...

In THE KILLING CLUB , what remains of the Nice Guys return to the UK, determined to kill off their former client-list, men who might conceivably give evidence against them in court. A spate of horrific torture-murders thus ensues ...

In

DEAD MAN WALKING

, Heck, after one massive fall-out too many with Gemma, transfers to the Cumbrian Police, and finds himself in charge of an isolated rural police station during a foggy winter, just at the time when a vicious, unprovoked attack on some hill-walkers proves eerily similar to the crimes of the Stranger, a serial killer who terrorised Devon 10 years earlier, and was never caught ...

In

DEAD MAN WALKING

, Heck, after one massive fall-out too many with Gemma, transfers to the Cumbrian Police, and finds himself in charge of an isolated rural police station during a foggy winter, just at the time when a vicious, unprovoked attack on some hill-walkers proves eerily similar to the crimes of the Stranger, a serial killer who terrorised Devon 10 years earlier, and was never caught ... In HUNTED , Heck and Gemma are still partly estranged, but Heck is back in the SCU fold, and heads down to Surrey, where he begins to suspect than a spate of unlikely but fatal accidents might actually have been engineered by someone playing elaborate but deadly pranks ...

In ASHES TO ASHES , Heck almost snags John Sagan, a professional torturer, who rents himself out to the highest bidder. The trail warms up again when new intel suggests that Sagan has headed north, to participate in a violent gangland war (one very gruesome aspect of which is an unknown hitman who incinerates his victims with a flame-thrower!). Gemma authorises Heck to head up there and get involved. There’s only one problem: the epicentre of the violence is Bradburn, the home town that Heck has so utterly disowned ...

Which brings at last us to

KISS OF DEATH

, due out in August, but available to pre-order right now, if you so wish.

Which brings at last us to

KISS OF DEATH

, due out in August, but available to pre-order right now, if you so wish.In this one, savage police cuts have finally reached the National Crime Group, and to prove that her unit still has a role to play, Gemma joins forces with Scotland Yard’s Cold Case Team. Together, they put together a list of the 20 worst British criminals still evading justice, in order to hunt and catch them all. Heck pursues a vicious bank robber/kidnapper, but then uncovers a ghastly video, which suggests that many of the UK’s top criminals have not disappeared because they are on the run, but for very different reasons, reasons almost to sickening to comprehend …

So, there you go. That’s where we are at present.

To recap, Heck is now 39 years old, and still in the thick of it, walking a tightrope through a world of ultra-violent crime. Check out DEATH’S DOOR (next Friday), for a 20,000-word novella that will take you back to the very important early days of his relationship with Gemma Piper, and KISS OF DEATH (August 9) for the latest installment in the ongoing series of novels.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE HANGING CLUB

THE HANGING CLUB

by Tony Parsons (2016)

Detective Constable Max Wolfe is a single-parent cop attached to the Major Incident Team at West End Central.

Under the steady leadership of his quietly-spoken but firmly authoritative boss, Detective Chief Inspector Pat Whitestone, he divides his time between caring for his beloved young daughter, Scout, and investigating bizarre and disturbing murder cases. The Hanging Club will be the third such case that we readers have joined him on, and it will see him tested to his absolute limits.

The horror begins when a London taxi-driver only recently released from jail after serving time for his role in a grooming gang, is video-taped being hanged by the neck in a dingy cellar and the images fed online. Other similar acts of ‘frontier justice’ now follow.

In rapid succession, a cashed-up boy-racer from the City gets off lightly after mowing down the grandson of ex-gangster, Paul Warboys, and so he too is strung up at an unknown location and the film of it played to the nation. Ditto a junk-head idiot who beat an octogenarian war-veteran into paralysis in order to get drugs money; he too walked away untouched and so also gets the rope.

By this time, Whitestone and Wolfe realise that they are dealing with an organised vigilante group who are apparently determined that they aren’t going to stop until justified violence has been served fully on the endless train of scumbags who seem to pass through the British judicial system with no more than a slapped wrist.

But there is a little bit more to it than this.

Some of the bodies are dumped at Marble Arch, near the site of the old Tyburn gallows, while on each of the hanging videos, a sonorous voice speaks beforehand, asking the victim if he knows why he has been ‘brought to this place of execution’. These guys take themselves very seriously; in their eyes, they aren’t just a gang, they are the new face of law-enforcement in 21st century Britain, an alternative to the official but jaded legal system which even Wolfe thinks has been hijacked by clever lawyers and judges dwelling in ivory towers. (Right at the beginning of the narrative, Wolfe himself is infuriated when one of his own cases fails, the Central Criminal Court going easy on three hooligans who kicked a householder to death and filmed it on their iPhones).

Conventional investigative techniques pay no initial dividends. Warboys, who, during his violent past, shared top billing with the Krays and Richardsons, seems a likely candidate, but he’s old now and past it. He sympathises with the Hanging Club (as the press gleefully proclaim them), but he doesn’t appear to be connected to them. Extensive surveillance of the deposition sites in the West End bears no fruit, and the forensics draw a blank. So, Whitestone calls in various experts.

Professor Hitchens is a historian who knows London inside-out. He’s initially hostile to the police, thinking himself above such mundane activities as crime-fighting, but Wolfe soon brings him down to Earth, though even then Hitchens is only really able to colour in the background (which, in several very enjoyable scenes, drives Wolfe to consult with old sweat, Sergeant Caine, the retiree who curates the infamous Black Museum).

Then there is Tara Jones, a beautiful but profoundly deaf woman who, ironically, is an expert at voice biometrics. By conducting computer analysis of the audio tracks on the video feeds, she is more useful to the team, who need to crack the location of the kill-site, by focussing on the sound of heavy building work nearby – though all this really tells them is that the subterranean location is somewhere in central London.

As if all this isn’t problematic enough, Wolfe finds himself in temporary charge when Whitestone’s son is blinded in an unprovoked nightclub attack, and at the same time, he must babysit Scout, who has now finished school for the summer holidays, and look out for Jackson Rose, a former school-friend turned army deserter and societal dropout, who, considering that he was only a cook when he was in the forces, seems to be remarkably adept at combat (both with and without weapons). Rose is currently lodging with Wolfe, but his oft-voiced support for the Hanging Club sees the copper getting increasingly worried and suspicious.

Of course, the ex-squaddie isn’t the only one to think this way. And here lies the real problem. Even while the enquiry stumbles around in the dark, the murderers’ popularity is growing among the general public, cheap newspaper headlines hailing the killers heroes and creating a mob atmosphere in a city soon sweltering in unusually high temperatures. This incendiary mood only amplifies when the vigilantes next target a Muslim hate preacher, an incident that adds race and religion to the mix.

And just when it seems that things can’t get any worse, Wolfe himself is grabbed. The Hanging Club aren’t just hunting the guilty, it seems, they are also looking to punish those who they see as protecting them …

Tony Parsons, renowned journalist and ‘men-lit’ author, came onto the crime fiction scene several years ago in a blaze of publicity, which left people with very high expectations. When the Max Wolfe series first got going, my expectations were largely fulfilled. The two novels before this one – The Murder Bag and The Slaughter Man – were slick, taut thrillers, which left me wanting much more. However, I’m slightly less sold on The Hanging Club . Not that it doesn’t contain some great stuff. It does, but I might as well get the brickbats out of the way first.

It is filled with procedural exposition, policing-by-numbers if you like, something which, whenever I see it in a book, makes me think that the author is taking up a lot of page-space trying to show how much research he/she has done. In this novel, it’s repetitive and distracting. I also took issue with the way the major investigations team is portrayed (which is ironic, because, as I say, otherwise Parsons has clearly done his homework). Basically, it’s undermanned. Whitestone’s absence leaves DC Max Wolfe in charge, apparently with only the assistance of DC Edie Wren, and trainee detective, Billy Greene. In my own police experience, it wouldn’t be completely unknown for an officer of constable rank to take point on an enquiry if he/she was deemed to have a certain expertise, but tackling the Hanging Club would surely be a massive operation and allocated huge resources, including a deputy SIO, duty DIs, etc?

But ultimately, these are the only problems I had with it.

The Hanging Club is a rattling good read, intriguing and exciting all the way through, and filled with colourful London characters. London itself is one of these, because in this novel we stay firmly in the centre of town, going both above it and below it, but never straying further west than Hyde Park or further east than the Old Bailey. I have a personal interest in the mythology of our capital city, and much of that is examined here, both interestingly and intelligently. I don’t want to say too much more about that, because I’ll risk giving away vital plot-points, but Tony Parsons is clearly in his element in this part of the book, effectively evoking the mysteries and brutalities of the old world, which, in London at least, are only buried under our feet by a few inches of concrete, if that.

He also – and this is a slightly more serious point – gives us a polemic about British justice.

Okay, in some ways, the idea may seem a bit hackneyed: honest cop falls out with system because hoodlums go unpunished, but eventually stands by it because it’s all he’s got. But in The Hanging Club it is elaborated on from various angles and with serious thought. Yes, we do see vile creatures enjoying the torment of their victims’ families in court, mee-mawing to their pals in the public gallery and celebrating when they beat the rap. Yes, we do hear the coppers’ frustration, and listen agog to judges summing cases up purely on the basis of legalese and without a hint of actual humanity. But we also learn about the savagery of the older methods, which so many empty-headed people hark back to; we hear what a verminous pit Newgate Prison was, and how folk could be incarcerated there and even dragged out along Dead Man’s Walk to be lynched in front of a raucous crowd for offences that would seem totally petty even in the 20th century let alone the 21st.

It’s a real conundrum that Parsons hits us with, but it comes with a warning too; namely that when a tide flows inexorably against public opinion, there may be a backlash which could easily get out of control. You don’t let the mob rule, but you must at least pay heed to their wishes.

Don’t let that put you off, by the way. The Hanging Club may be written with a clever subtext, but overall, it’s nowhere near as heavy as that may make it sound. It’s a fast, accessible read, and fans of London crime thrillers in particular will have no trouble enjoying it.

I’d have thought that any novel with Tony Parsons’ name on it would have a better-than-average chance of film or TV adaptation at some point. I’m not sure where the Max Wolfe series stands in that regard, but on the off-chance they need me to give them a little nudge, as usual I’m going to pitch in with my own recommendations for a cast should The Hanging Club ever get the green light. Just a bit of fun of course. Feel free to agree or disagree, as it suits you.

DC Max Wolfe - Richard ArmitageJackson Rose - Noel ClarkeTara Jones - Hayley AtwellDCI Pat Whitestone - Anna HopeDC Edie Wren - Rachel Hurd-WoodProfessor Hitchens - Russell ToveyPaul Warboys - Donald SumpterSergeant John Caine - Kevin Lloyd

Published on June 24, 2018 11:00

June 8, 2018

Crossing the country to punish the guilty

I’m going to be talking a bit more about KISS OF DEATHthis week. That’s my next novel, which is due out in August. In particular today, I’ll be focussing on some of the sexy locations we visit during the course of it, one of which is an idyllic place on a rural stretch of the English coastline.

On that same seaside theme, though it’s a bit more exotic in this other case, I’ll also be reviewing and discussing, in my usual forensic detail, Michael Marshall’s never less than totally compelling thriller, KILLER MOVE.

Those of you who are only here for the Mike Marshall review, you’ll find it at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Feel free to scroll straight down there. But if you’ve got a bit more time to kill, you might be interested first in the stuff I’ve got to say about

KISS OF DEATH

.

Those of you who are only here for the Mike Marshall review, you’ll find it at the lower end of today’s blogpost. Feel free to scroll straight down there. But if you’ve got a bit more time to kill, you might be interested first in the stuff I’ve got to say about

KISS OF DEATH

.Coming soon

The marketing drive behind KISS OF DEATH is really picking up now. I’m seeing the book’s cover everywhere. I also note, as pictured above, that the Kindle reviewers are already receiving their e-copies. For those who are really, really excited about this, and just can’t wait until August 9, you may already be aware that DEATH’S DOOR , a brand new 20,000-word Heck e-novella, will come out first on June 29.

You can get that one entirely FREE, though I ought to add that it’s not essential for you to read DEATH’S DOOR in order to enjoy KISS OF DEATH . The former is set at a very early stage of Mark Heckenburg’s police career, when he and girlfriend, Gemma Piper, who is now his ex-girlfriend – and his boss of course! – were setting up home together in North London. But it does a bit of groundwork on the relationship, which newcomers to the series might not know about.

One of the things I like most about writing the Heck books, though, and one thing that is commented on most often by fans and reviewers, is the range of locations we travel through in each story.

Heck and Gemma – he now a detective sergeant, she now a detective superintendent – both work for the Serial Crimes Unit (part of the National Crime Group, based at Scotland Yard – and I had the idea for that before the real UK police service did, so they pinched the idea off me). This operates as a kind of British FBI, its officers consulting and assisting widely across all the police force areas of England and Wales, wherever crimes fitting their particular expertise are being investigated.

Heck and Gemma – he now a detective sergeant, she now a detective superintendent – both work for the Serial Crimes Unit (part of the National Crime Group, based at Scotland Yard – and I had the idea for that before the real UK police service did, so they pinched the idea off me). This operates as a kind of British FBI, its officers consulting and assisting widely across all the police force areas of England and Wales, wherever crimes fitting their particular expertise are being investigated.Before anyone asks, this was a deliberate ploy on my part. It seems to me that there are lots of fictional detectives out there at present, all of whom have their own patch, which they (and their authors) know inside out. I’d venture to suggest that Lucy Clayburn, my other police character, who is permanently based in Crowley in inner Manchester, is one of these. But with Heck, I wanted to do something very different. I wanted a change of scene as often as possible, and in the six Heck novels prior to this one, we’ve done that a lot.

So, for example, the very first one,

STALKERS

, took him from London to Manchester to the Thames estuary in Kent. In

THE KILLING CLUB

, we went from the Cotswolds to Holy Island off the Northeast coast. In

DEAD MAN WALKING

, it was the Lake District in the depths of a foggy winter, in

HUNTED

the Surrey Weald at the height of a glorious summer, and so on.

So, for example, the very first one,

STALKERS

, took him from London to Manchester to the Thames estuary in Kent. In

THE KILLING CLUB

, we went from the Cotswolds to Holy Island off the Northeast coast. In

DEAD MAN WALKING

, it was the Lake District in the depths of a foggy winter, in

HUNTED

the Surrey Weald at the height of a glorious summer, and so on.In KISS OF DEATH we are really pushing the boat out (quite literally at one point), Heck visiting places that are poles apart from each other, both in tone and spirit, as well as geography. And here are just some of them:

London (west), as photographed by David Henderson ...

Humberside, as photographed by Bernard Sharp ...

London (east), as photographed by MJ Richardson ...

And Cornwall, as photographed by Richard Law ...

It amused me once when a reviewer referred to this device as “a poor man’s James Bond tactic”. Well, I must admit, Britain’s abandoned buildings and desolate backstreets, and even her splendid countryside can’t compete easily with Miami or Hong Kong or Moscow or Istanbul, or wherever Bond happens to be next. But one thing I do share with Ian Fleming when writing my novels is motivation.

I’ve wanted always Heck to be more than just a local investigator and have tried to draw his stories on a grand canvas, where heinous villains and phenomenal action sequences can all comfortably be found without raising too many eyebrows. But he’s not an SAS man or a rogue MI6 agent, so he can’t continent hop, and must deal solely with those issues falling inside his own jurisdiction.

As I once said to a writers’ group I addressed in Liverpool, you can’t take Heck seriously when he’s riding the roofs of trains, or jumping off motorway bridges onto the backs of lorries, or tackling gangs of Russian drug-traffickers, if every case is set, for example, in my hometown of Wigan. He has to get out there a little bit.

Anyway, that’s all I’m going to reveal about KISS OF DEATH for now … and no, the bit about Russian drug-traffickers is not a hint, though rest assured: in this new one, Heck still goes one-to-one with some of the worst of the very worst.

Just a quick reminder that, while it’s already available for pre-order, it can actually be acquired on August 9, and that the e-novella

DEATH’S DOOR

, which is completely FREE, will be available on June 29.

Just a quick reminder that, while it’s already available for pre-order, it can actually be acquired on August 9, and that the e-novella

DEATH’S DOOR

, which is completely FREE, will be available on June 29.In the time remaining between then and now, I’ll be dropping further morsels your way. Just keep checking back here.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

KILLER MOVE

KILLER MOVE by Michael Marshall (2011)

When the enigmatic John Hunter is released from prison after serving 16 years for murder, we immediately get the feeling that his crime and its repercussions aren’t over. Hunter isn’t a threatening man; quite the opposite – he’s placid and respectful, to the point where the warden of the US jail in which he’s been incarcerated is almost sorry to see him leave. Apparently, Hunter has been an exemplary prisoner, which explains why he’s had so many years trimmed off his original sentence.

But Hunter’s iron-core strength, not to mention his inner darkness, are more than evident to us readers – thanks mainly to the subtle skill with which he is depicted. And when, as soon as he hits the outside world, he goes looking for a gun, we realise that all our unspoken fears about this man are about to come true.

Meanwhile, in the somewhat less ominous environment of ‘the Breakers’, a luxury condo complex in the Florida Keys, ambitious young realtor, Bill Moore, is doing his best to live the American dream. He has a lovely and successful wife, Steph, he makes good money selling top-quality seafront properties, owns one himself, drives a swish car, and enjoys a promising relationship with his boss, Tony Thompson (despite Thompson’s rather disdainful other-half, Marie).

The Moores aren’t even close to being the wealthiest folk on the block. That status, if it doesn’t lie with the Thompsons, may lie with neighbouring widow, Hazel Wilkins, or one of the upscale neighbourhood’s real movers-and-shakers, business mogul David Warner. But Bill and Steph strongly aspire to be part of this racy set, and feel they are well on the way to getting there. Even if they don’t manage it straight away, life here is good; Bill is friendly with local lawman, Sheriff Frank Barclay, though there is minimal crime for the elderly cop to deal with in this idyllic spot.

And then, one day, quite out of the blue, Bill receives a card printed with a single word: MODIFIED. His first reaction is to assume that it’s a joke, but from this moment on his and Steph’s lives slowly start falling apart.

Initially, it’s almost innocuous. A semi-pornographic book arriving from Amazon, which Bill has no memory of ordering. Then a vaguely racist joke circled from his email account, which, fortunately, most of the recipients are amused by – though Bill would never have sent such a message. He and Steph really stop seeing the funny side of things when voyeuristic images of Bill’s gorgeous co-worker, Karren White, are found on his laptop.

Bill investigates but is hampered by further chilling developments. Steph vanishes – whether that’s because she’s still irritated with him about Karren or because of something more sinister, he doesn’t know. And it isn’t easy asking questions around town when the police are on your case – because, quite bewilderingly, he now finds himself implicated in another disappearance, that of David Warner. Despite this, and with the assistance of a spirited young waitress, Cassie, whom he befriends almost by default, he gradually figures out that he’s the become the object of a cruel and relentless game controlled by powerful but faceless individuals.

Even then it might just be tolerable, a bit of harmless fun which while it is undoubtedly inconveniencing Bill Moore, could all be put right by some financial restitution at the end. But then people start dying. If this is a game, Moore realises – still minus his wife, still with the law on his case – it’s a game that may well result in the end of his life … For years, Michael Marshall has written sci-fi, horror and fantasy under the not-dissimilar pen-name, Michael Marshall Smith, and he’s done so effectively and successfully. So, no-one should be surprised to pick up a thriller like this and find that it's filled with ultra-dark concepts. That isn’t to say that it’s particularly violent. It’s certainly no more violent than the average crime thriller, but there is a dehumanising brutality of purpose to some of the characters in Killer Move , which, when you sit back and think about it, is quite disturbing.

For example, John Hunter is a man whose life has genuinely been ruined. Even though he’s not especially evil, he enters our awareness as a cold, frightening individual, a guy for whom vengeance is the only reason to live – literally. And you know almost from the outset that it’s going to be extreme vengeance, delivered without qualm or hesitation. Even though Hunter is a man grievously wronged, it’s difficult to root for such a person in a novel as well-written as this, because it’s so easy to picture him in real life as someone you’d run a mile to avoid.

But Hunter isn’t the worst of it, because while a powerful presence, he’s not one of the main characters, and if nothing else at least he isn’t a direct threat to the hapless hero of the piece, Bill Moore. But while the overarching concept – that a bunch of bored richies might seek to fill their empty days by playing cruel games with other people’s lives – may seem vaguely fanciful (would you really get off on this kind of thing so much that you’d actually go to the expense of hiring ex-spec ops people to make it happen?), there is a much deeper darkness here.

The utter soullessness required to turn other people into your playthings undoubtedly rings true. And this for me is the real success of Killer Move .

With the exception of Hunter, who’s clearly deranged, and Bill Moore, who’s introduced to us at first as an annoying go-getter of the sort you can easily imagine packing US realty, but who learns through bitter experience how much he loves his wife, Steph, no-one else cares about anyone, even in an affluent community in southern Florida. The wealthy gamers are so absorbed in their own fun – even though it patently isn’t that much fun, as they are still jaded and bored – that feelings for their fellow men don’t even figure on their radar. But this self-interest extends to others too. Moore’s colleague, Karren White, is only superficially his friend; in reality she’s a rival, whose chief interest are the bonuses she can get at his expense. Even lowly office secretary, Janine, harbours secret resentments, which finally emerge in a scene that I found quite stomach-turning, because even though there is no violence used, a rotten human soul is unexpectedly but very plausibly laid bare to us.

And if that’s the whole of Breakers society written off, then I suspect that’s exactly what Michael Marshall intended. Though more likely he’s actually going further than that, and being cynical about the whole of society, because let’s face it, the truly malevolent force in Killer Move , which lies hidden until the very end of the book, can be hugely confident that this whole disaster, even when played out so full-bloodedly, will soon become yesterday’s news because of our modern-day mindset in which nobody else really matters.

For all these reasons, Killer Move makes increasingly uncomfortable reading, but you’ve got to stick with it and you’ve got to pay attention. Because what gradually unfolds here is a compelling but complex saga. Wheels turn within wheels; there is villainy within villainy, and no shortage of suspects. Bill Moore finally reaches a point where he doesn’t know whether to trust anyone else at all, wondering if he’s the only person on stage who’s not an actor – and we, the readers, ask ourselves the same question. More than once.

On top of that, we spend a not insubstantial portion of time philosophising. And because this is Michael Marshall and this is another thing he does so well, this is always interesting and amusing, especially as in this book it’s done through the mind’s eye of Bill Moore, who we soon realise is a much deeper and less confident character than we first thought, which means that it’s all wonderfully acerbic. The trade-off to this is that Killer Move is no quickfire actioner, but it’s still totally engrossing. As the mysteries pile up, and the obstacles cluttering Moore’s life become ever more insurmountable, you’re literally flying through the pages. You must know how it’s all going to resolve itself, even though it’s soon pretty obvious that that isn’t going to happen easily or without casualties.

One quick warning. Killer Move is a kind of unofficial add-on to Marshall’s remarkable ‘Straw Men’ trilogy. Now, if you haven’t read any of the Straw Men books, never fear. That won’t interfere with your enjoyment of Killer Move , as the author explains in more than adequate fashion just who the Straw Men are and how their existence impinges on this completely separate little drama. It all works perfectly well for me, but if you’re someone who really needs every single i dotted and every t crossed before you reach the last page, it might be an idea to check out those other titles first (it’s not like you won’t enjoy them thoroughly). They are, in this order: The Straw Men , The Lonely Dead and Blood of Angels .

The pre-existence of those other three novels also serves to make my habitual casting session even more meaningless than it usually is. But I’m still going to have a go. I’d like nothing better than to assemble the actors that could bring this taut tale to the screen, and how cool would that be, given that I always have a limitless budget (LOL). But for this one to work, you’ll just have to assume that The Straw Men etc have already hit the cinemas, because I can’t imagine that Killer Move would get this treatment first. Anyway, here we go:

Bill Moore – James MarsdenStephanie Moore - Renee ZellwegerJohn Hunter - John CusackCassandra - Erin MoriartyKarren White – Alison BrieSheriff Frank Barclay - JK SimmonsTony Thompson - Sam ElliottMarie Thompson - Susan SarandonHazel Wilkins - Charlotte RamplingDavid Warner – Don Johnson

Published on June 08, 2018 02:00

May 29, 2018

Brand new Heck novella, absolutely FREE

Anyone waiting for the next Heck novel, KISS OF DEATH, which will hit the shelves in August, and who can’t wait that long, may be interested to learn that a brand new Heck e-novella, DEATH’S DOOR, set when he was still a young detective constable in the East End of London, will be available much sooner than that … entirely free of charge.

Anyone waiting for the next Heck novel, KISS OF DEATH, which will hit the shelves in August, and who can’t wait that long, may be interested to learn that a brand new Heck e-novella, DEATH’S DOOR, set when he was still a young detective constable in the East End of London, will be available much sooner than that … entirely free of charge.In addition today, while we’re talking about shorter-than-usual forays into dark fiction, I’ll be offering a detailed review and discussion of Stephen King’s excellent chiller, JOYLAND.

If you’re only here for the King review, no problem. You’ll find that, as usual, down at the lower end of today’s blog. Feel free to shoot on down there straight away. However, if you’ve got a bit more time on your hands, perhaps you’ll be interested to learn a little more about DEATH’S DOOR .

Early days

When KISS OF DEATH comes out this August, it will be the seventh book in the DS Mark Heckenburg series, and as part of that, it occurs in the present-day UK, its events unfolding as you read about them. Set against a backdrop of savage police cuts, it concerns a ho-holds-barred hunt by the Serial Crimes Unit for a hit-list of Britain’s 20 most dangerous and violent criminals who are still on the run from justice, during the course of which Heck and DSU Gemma Piper (his former girlfriend-turned-boss) get their hands on some grainy, black-and-white video footage with truly hideous content, which subsequently leads them to uncover a terrifying conspiracy.

No more about that at present. But much more about

DEATH’S DOOR

(out on June 29, for the princely price of nothing at all) which while it isn’t exactly a prelude to

KISS OF DEATH

, (though, as a bonus, it does contain a sneak peek at the novel!) tells an earlier but very relevant tale from Heck and Gemma’s relationship.

No more about that at present. But much more about

DEATH’S DOOR

(out on June 29, for the princely price of nothing at all) which while it isn’t exactly a prelude to

KISS OF DEATH

, (though, as a bonus, it does contain a sneak peek at the novel!) tells an earlier but very relevant tale from Heck and Gemma’s relationship.I’m hopeful that most regular readers by now will be equally as interested in the overarching ‘Heck and Gemma’ story thread as they are the horrible crimes that Heck regularly finds himself investigating (I’d be inhuman if I hadn’t noticed that the ‘will they or won’t they?’ thing is now a big issue for certain followers of the series), and DEATH’S DOOR will only add to that, taking us back to a time when our two heroes weren’t just boyfriend and girlfriend, but were actually living together in a small flat in Finsbury Park.

However, stresses in the relationship are now finally showing. You may recall that, last Christmas, I ran the novella, BRIGHTLY SHONE THE MOON THAT NIGHT on this blog, which was set even earlier in their relationship, when all was hunky dory and the twosome, as well as being very much in love, were working well together as fellow detective constables in Bethnal Green CID. When DEATH’S DOOR is set, they are still working as DCs in Bethnal Green (and as I say, by this time living together), but Gemma is increasingly frustrated with Heck’s rule-bending and risk-taking, especially as she is about to embark on the series of promotions that will eventually propel her to the uppermost tier of the job.

That said, if there’s one thing Gemma unfailingly trusts about Heck, it’s his intuition. And when he comes to suspect that a mysterious peeping tom who has occasionally been spotted on a local housing estate might pose a much, much greater threat than it initially seems, she knows that it won’t pay to ignore him …

As I say, you can acquire DEATH’S DOOR , all 20,000 words of it, from your favourite online retailers from June 29, and it won’t cost you anything. If you’re planning to buy KISS OF DEATH later in the year, I strongly suggest you dip into this one first, as it gives yet more of the crucial back-story between the series’ two central characters (and as a quick reminder, it also gives you a glimpse at some early chapters of the forthcoming novel).

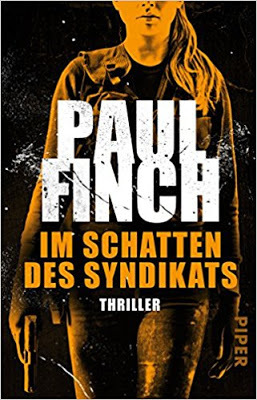

Still on the subject of my fictional police heroes, I have to say that I love this fantabulous cover from Piper Verlag, my publishers over in Germany.

Still on the subject of my fictional police heroes, I have to say that I love this fantabulous cover from Piper Verlag, my publishers over in Germany.This is IM SCHATTEN DES SYNDIKATS , the German translation of SHADOWS , my second Lucy Clayburn novel (published over here last October, but due out from Piper next January).

Again, as with the first Lucy novel to appear in Germany, the marketing strategy is noticeably different.

Again, as with the first Lucy novel to appear in Germany, the marketing strategy is noticeably different.As you can see here, the original English novel hit the shops in the style of a domestic noir – which wasn’t strictly accurate, in my view, given that the Lucy Clayburn novels are dark-toned police procedurals, but which was understandable given how popular domestic thrillers were in the UK up to and including last year.

Over in Germany, there is clearly a greater interest among sales strategists in Lucy’s biker credentials and her ‘action girl’ approach to policing (the inheritance, no doubt, of her estranged father, who is now a high-ranking figure in the Manchester underworld).

Over in Germany, there is clearly a greater interest among sales strategists in Lucy’s biker credentials and her ‘action girl’ approach to policing (the inheritance, no doubt, of her estranged father, who is now a high-ranking figure in the Manchester underworld).Either way, I love this latest cover from Piper just as much as any of the others. As with SCHWARZE WITWEN , the first German edition of a Lucy Clayburn novel, it completely captures the image of the heroine that I had in my mind’s eye when I first wrote about her.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

JOYLAND

JOYLAND

by Stephen King (2013)

It is 1973, and New England-born college guy, Devin Jones, is screwing things up educationally. Head over heels in love with classmate, Wendy Keegan, he just can’t focus on his studies – a problem that worsens when reality starts dawning that her increasing coolness is basically because she doesn’t share his ardour.

As the girl is at no stage kind enough to turn around and tell him he’s dumped, Devin continues to delude himself that Wendy is his, even when he flees into a summer job at Joyland, a second-rate amusement part on the North Carolina beachfront.

Deep down, of course, he’s well aware that the relationship has fractured, probably fatally, but instead of facing the fact, he throws himself into the new alliances he makes at the park, specifically with fellow ‘greenies’ (summer-staff), Tom Kennedy and Erin Cook, but also with hardbitten carney regulars, Fred Dean, Lane Hardy, and even grouchy old Eddie Parks, the latter group of whom, though they are civil enough with Devin on his first arrival, only become his firm pals when they discover that he excels at ‘wearing the fur’, i.e. putting on the costume of Howie the Happy Hound, the park’s mascot, and entertaining the kiddies.

It’s a long, hot, hardworking summer, during which the tireless Devin wins the approval of nonagenarian park-owner, Bradley Easterbrook, ends up being mothered by firm but fair landlady, Emmalina Shoplaw, and even attracts the attention of fortune-teller, Rozzy Gold, who is disturbed to see something bad in the kid’s future.

And this is the thing about Joyland. Though it does exactly what it says on the tin, providing a great afternoon for young families, it has a dark history. There was a murder here in the 1960s, when a girl had her throat cut on the Horror House ride. If that isn’t enough, the case was never solved, and rumour-mongers hold that the victim, Linda Gray, was only one of several attributable to the same maniac.

This macabre story is of growing interest to Devin, especially when he learns that the Horror House is now supposed to be haunted for real, Linda Gray’s sad ghost lingering in its shadows, looking to make contact with anyone she can, so that she can name her killer.

Devin never sees the ghost, himself, or even senses its presence, and is envious when he learns that Tom Kennedy has done, even though Tom doesn’t think this cool at all, and in fact was so frightened by the experience that, once the summer is over, he plans to get as far from Joyland as he can – and intends to take Erin with him, as the twosome are now an item (despite Erin and Devin’s mutual attraction).

Meanwhile, Devin, who’s grown to accept that he’ll never see Wendy again, is cultivating a relationship with another young woman, though this one is far more complex.

Single mother, Annie Ross, is spending the summer in her wealthy evangelical preacher father’s coastal mansion, and is sole guardian to her crippled, dying and yet permanently cheerful son, Michael. It is Michael who initially makes friends with Devin, a relationship Annie tries to discourage because she thinks it will end in tears – though when she actually gets to know Devin, she realises that he’s an okay guy.

But even this arrangement starts to prove difficult. Young Michael is another who possesses second-sight – and in his case it’s genuine. He doesn’t just get vague impressions like Rozzy Gold, so when he too warns Devin that something bad is looming, it needs to be taken seriously.

From a reader’s perspective, of course, it’s impossible not to form a suspicion that this approaching danger must be connected to story of the Funhouse Killer, with which Devin is increasingly fascinated. In fact, at the end of summer, when Tom and Erin go back to college, but Devin stays on – having decided to take a year out – the girl, at Devin’s behest, starts to research the case, and comes up with some compelling clues, which she duly sends back.

The question is will Devin be able to make use of these, and if he can, will that in itself be a problem? Because, if you’re a soulless, many-times murderer, and you learn that someone’s investigating you, aren’t you going to take action to prevent it? And if you’re really and truly wicked, isn’t it also possible that you won’t just draw the line at dealing with him, but maybe with all those he knows and loves as well? …

My first impression on reading Joyland was that it may have started life as a novella, or even a short story. It’s a fairly slight concept, and a very linear narrative, uncluttered by the usual side-tracks and detours that Stephen King’s larger novels are renowned for. Was it originally a shortie, I wonder, and in that inimitable Steve King style, did it simply grow with the telling? That said, it isn’t padded; there’s no issue there, and it’s a very fast read – so no-one must be concerned that Joyland is a bit of nothing.

The second impression I got is that it’s another classic piece of King’s folksy Americana. Once again, we’re in the US of the author’s younger days, his college years perhaps, which are evoked in completely authentic and loving detail. This is a classic Stephen King retrospective on earlier periods of his life. Not content just to tell you how it looked and sounded and smelled, he gets you right into the mindset, helps you capture the zeitgeist. To start with, this is a politer age; everyone, you feel, has less than they do now, yet they are more genteel. People are adults when they hit their mid-20s, and automatically are treated with respect by juveniles. Students work their way through the vacation, and they work damn hard, because they need the money. Rules at rooming houses are there to be obeyed. Children are less streetwise, and yet intangibly tougher than their counterparts today. The simple pleasures of an amusement park are deemed a worthwhile experience for working class families who take nothing for granted.

As for King’s descriptive powers … well, it’s the usual case of every other writer who reads it going green with envy. Everything about Joyland, the park, is vivid. You can hear the whistles and bells of the rides, you can smell the candy-floss and ketchup, can hear the roar of the nearby surf, and feel the tremors of excitement on first sight of the simp-hoister(Ferris wheel), Zamp rides (children’s attractions) and bang-shies (rifle ranges).

Is it as terrifying as so many of his other works?

No, not a bit of it.

It’s a thriller. Be under no illusion about that, but it’s a low-key thriller. More important to the author on this occasion is the development of some wonderfully believable characters and relationships, and a deep contemplation of the afterlife.

Devin, for example, is only a young man – he rarely thinks about death; but there’s a killer at large, who preys on women younger even than he is. At the same time, little Michael is terminally ill, a fact he’s accepted with numbing bravery and stoicism. Because Joyland isn’t set now, this isn’t a world of atheists to whom death is oblivion. But this isn’t the long past either, so there’s uncertainty, there’s doubt, there’s fear. Annie Ross cannot disassociate the Jesus she learned about and loved as a little girl from the money-grabbing millionaire phoney that is her father. Even though there’s supposedly a ghost at Joyland, physical proof that we’re all spirits, Devin has never seen it, even though he yearns to (he misses his deceased mom terribly, and would love to hook up with her again).

This is all immensely affecting and moving – but there’s no schmaltz or sugar here; this is not a Disney story. And it makes for a hugely satisfying if very different kind of read.

I didn’t know much about Joyland when I picked it up. I tuned in expecting a typical blood-churning Stephen King chiller. I didn’t get that, but what I did get was yet another remarkable (if slightly shorter than usual) reading experience from one of the 20th and 21st centuries’ great masters of the written word.

Amazingly, given that almost everything Stephen King ever writes ends up on film or TV at some point, Joyland hasn’t – as far as I know – been adapted just yet. So (as usual) I’ll take a chance to nominate my own cast straight away. No-one’s going to listen to me, but hell, these guys would be great:

Devin Jones – Zac EfronAnnie Ross – Sienna MillerErin Cook – Saoirse RonanTom Kennedy – Kevin McHaleEmmalina Shoplaw – Kathy BatesEddie Parks – Billy DragoLane Hardy – Clancy BrownBradley Easterbrook – M. Emmet Walsh

As usual, the only one I can’t cast is young Michael Ross; I know so little about child actors of those tender years that it would be a wasted exercise.

Published on May 29, 2018 05:43

May 16, 2018

Demons, demons ... everywhere demons!

We’re firmly back on the horror trail this week. Primarily, that’s because there are big developments with the TERROR TALES series that I want to tell you about, but also because I’ll be reviewing and discussing A HEAD FULL OF GHOSTS, Paul Tremblay’s masterly study of a suburban family’s catastrophic decline during the course of what may or may not be a demonic possession.

As always, you’ll find that review towards the lower end of today’s blog. Skip straight on down if you’ve a mind to, but if you’ve got a bit more time, perhaps you’ll be interested to hang around and see what’s happening with TERROR TALES.

First of all, if readers of the series can forgive me, I’ll just need to give those who are new to it a quick thumbnail sketch.

TERROR TALES

was born from my love of regional folklore, not just in the UK but all over the world.

TERROR TALES

was born from my love of regional folklore, not just in the UK but all over the world.It was long my dream to commence editing a series of anthologies dedicated to this uniquely homespun brand of horror, but in order to create as broad an overview as possible, I knew that I’d need to focus each particular volume on a specific geographic region. So, for example, the first book in the series was TERROR TALES OF THE LAKE DISTRICT . Since then, we’ve covered, in no order of preference, the COTSWOLDS , EAST ANGLIA , WALES , LONDON , CORNWALL , the SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS , YORKSHIRE , the SEASIDE and the OCEAN .

My plan was not just to publish new fiction based on local terrifying mythology, but also to reprint a few classics here and there, and to intersperse the stories with short, factual anecdotes on the same theme.

So, again using TERROR TALES OF THE LAKE DISTRICT as an example, the marvellous stories Little Mag’s Barrow and The Coniston Star Mystery, as written by Adam Nevill and Simon Clark respectively, found themselves sitting either side of a vignette concerning the life and crimes of Tom Fool, the Mad Jester of Muncaster Castle (also depicted on the book’s cover). This has been the style of the series ever since, and from the responses I’ve had from readers, one of its most popular aspects.

When I first started with TERROR TALES back in 2011, the plan was to publish two books a year. But events have gradually conspired against that. My own novel-writing career has, to a degree, sky-rocketed, which has left me much less time to focus on the anthologies, and by the same token, Gary Fry, the owner of Gray Friar Press, the original publisher, has seen his own career develop and been left with no option but to move on.

This caused a brief interlude in the series, though last year we returned with a new publisher, Telos Books, and our first new title in a year and a half,

TERROR TALES OF CORNWALL

.

This caused a brief interlude in the series, though last year we returned with a new publisher, Telos Books, and our first new title in a year and a half,

TERROR TALES OF CORNWALL

.I’m glad to say that our audience hadn’t deserted us, but even now, with a new publisher behind us, doing two books a year is a bit on the difficult side. So, the revised ambition is just to do one. That will be a much more manageable time-frame and will give all those involved opportunities to do other things as well.

As such, this year’s offering, which I’m hoping will be available for pre-order in the early autumn, will be TERROR TALES OF NORTHWEST ENGLAND. I’m not able to show you the cover yet, though I’ve already viewed Neil Williams’s sensation artwork, and I’m totally blown away by it. Hopefully it will be available for you all to take a good look at in the very near future. Keep watching this space.

Making movies

Still on the subject of horror anthologies, here’s a fun thing.

I loved the recent, very scary movie, Ghost Stories (below, right), not least because it went where other recent British horror movies have feared to tread.

Some of you will already know that it was adapted by Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson from their stage play of the same name. It tells a nightmarish supernatural tale in which three chilling shorts cleverly interweave with a central narrative, creating a very satisfying whole. It got a mainstream cinema release, which is a rarity for this kind of movie in the 21st century, and has been widely viewed and applauded.

Some of you will already know that it was adapted by Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson from their stage play of the same name. It tells a nightmarish supernatural tale in which three chilling shorts cleverly interweave with a central narrative, creating a very satisfying whole. It got a mainstream cinema release, which is a rarity for this kind of movie in the 21st century, and has been widely viewed and applauded.At one time, British cinema was no stranger to this kind of thing. I’m sure you’ll all remember the halcyon days of the Amicus portmanteaux: Dr Terror’s House of Horrors, Tales from the Crypt, Torture Garden, Vault of Horror, Asylum, etc … which were very successful in the 1960s and 1970s (having taken their cue, of course from the classic Ealing chiller of 1945, Dead of Night).

I’d like nothing better than to see horror film-makers get back to this format in some shape of other, and it seems I’m not the only one. After the success of Ghost Stories, I understand that The Field Guide to Evil, another big-money portmanteau horror, is currently in production, while Channel 4 is presently running its True Horror TV series, in which real-life ghostly events from around the UK are each week dramatised and presented to us in short ‘horror fiction’ fashion.

I’d like nothing better than to see horror film-makers get back to this format in some shape of other, and it seems I’m not the only one. After the success of Ghost Stories, I understand that The Field Guide to Evil, another big-money portmanteau horror, is currently in production, while Channel 4 is presently running its True Horror TV series, in which real-life ghostly events from around the UK are each week dramatised and presented to us in short ‘horror fiction’ fashion.In respect of this apparent new interest in the short scary form, I thought I’d slightly alter my regular Thrillers, Chillers, Shockers and Killers section, by occasionally reviewing and discussing anthologies and single-author collections as well as novels – and each time I cover one, selecting four particular stories from it, which I’d love to see incorporated into a single movie, complete with my usual fantasy casting, etc.

While I’m not in a position to review any new anthologies at this moment, though I’m already inserting several into my to-be-read pile, I thought I might as well start with the Terror Tales books. I won’t review these as such – that would bit rich, me reviewing my own anthologies (five stars all round, lads!) – but I can at least turn each one into a portmanteau horror movie, pick the four stories necessary and cast them. In which case, assuming you’ve bought into the conceit of that, we might as well start at the beginning, with TERROR TALES OF THE LAKE DISTRICT (I’ll work my way through the others during the course of this year).

So, here is …

TERROR TALES OF THE LAKE DISTRICT – the movie.

Just a bit of fun, remember. No film-maker has optioned this book yet, or any of the stories inside it (as far as I’m aware), but here are my thoughts on how they should proceed. Note: these four stories are NOT the ones I necessarily consider to be the best in the book – I love all the stories in these anthos equally – but these are the four I perceive as most filmic and most right for a compendium horror. Of course, no such horror film can happen without a central thread, and this is where you guys, the audience, and your vivid imaginations, come in. Just accept that four strangers have been thrown together in unusual circumstances which require them to relate spooky stories to each other. It could be that they’re all trapped in a cellar by a broken lift, and are awaiting rescue (a la Vault of Horror), or are marooned on a fogbound train and forced to listen to each other’s fortunes as read by a mysterious man with a pack of cards (al la Dr Terror) – but basically it’s up to you.

Yes, I know, I’m copping out on that bit. But, tough. You’ve got the idea. So, without further messing about, here are the stories and the casts I envisage performing in them:

ABOVE THE WORLD by Ramsey Campbell

Lonely soul, Knox, is convinced that he hasn’t returned to the idyllic country hotel on the shores of Lake Bassenthwaite because he’s nostalgic about the holiday he once spent there with his lovely wife, Wendy. He’s moved on from those happy days, he tells himself, as he sets out on a solo hike through the surrounding fells, despite the impending stormy weather. He doesn’t regret their separation several years later, and he feels no grief that his ex-wife and the new man in her life suddenly and recently died while exploring these self-same wooded hills. What matter that he keeps hearing the drifting voices of an elusive couple? What matter the increasing sense that he isn’t alone in this bleak, desolate place …?

Knox - Steve PembertonWendy - Anna Friel

THE CONISTON STAR MYSTERY by Simon Clark

Amateur frogmen, Blake Keller and Andrew Harper plan to scour the depths of Coniston Water, searching for the remains of famous escape artist, Iskander Carvesh, who drowned in 1910, when the boat he was chained upon, the Coniston Star, sank without trace. It’ll be a dangerous dive, but Keller and Harper know what they are doing. The only potential fly in the ointment, is Enid, a handsome blonde they’ve only known a day but who wants to accompany them. Loudmouthed Keller delights in trying to frighten her with his tales of underwater peril, but Enid is no novice, and she has dark reasons of her own for making this very dangerous dive …

Keller - Steve OramHarper - Michael SochaEnid - Florence Pugh

THE CLAIFE CRYER – by Carole Johnstone

The tale of the Claife Cryer, a horrible, disembodied voice said to have cried out from the shadows on the wooded west shore of Windermere, luring a young ferryman to his death, is one of the scariest Lake District ghost stories Kerry has ever heard. But of course, she doesn’t believe it, or she tries not to on the day she and her unpleasant father attempt a bonding exercise by exploring that thickly-treed region. Local gossips say the voice belonged to a deranged monk from a monastery now long abandoned. Spooky as that is, Kerry doesn’t feel it’s half as bad as spending time with her scornful and argumentative parent, but then, as twilight descends, she hears an awful cry. And then she hears it again. And again. Undeniably, it’s getting closer …

Kerry - Ella Purnell Dad - David Morrissey

THE MORAINE by Simon Bestwick

College lecturers Steve and Diane’s relationship is in trouble. Hopes were high that a Lake District hiking trip would be just the thing. But they’re still not getting on, and that’s not helped by the terrible October weather, everything wet and gloomy, and now – typically – just when they’re lost among the high, rock-strewn peaks, a thick mist coming down, which ensures that they lose the path as well. Even then, in danger, they don’t form easy allies – though in truth, they don’t know the meaning of danger yet. That will only come when they realise they’re being stalked by something unseen, something that can mimic animal sounds and human voices, and which appears to be stalking them underneath the endless heaps of moraine …

Steve - Iwan RheonDiane - Jessica Brown Findlay

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller, horror and sci-fi novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

A HEAD FULL OF GHOSTS

A HEAD FULL OF GHOSTS by Paul Tremblay (2016)

Meredith Barrett is an intelligent, sophisticated and seemingly stable young woman, leading a relatively quiet life in a South Boston apartment. However, it’s fairly well known that when she was a child, something appalling happened to her family, something she hasn’t been able to speak fully about for years, in consequence of which the true facts in the case are much-mythologised. When best-selling author, Rachel Neville, arrives to interview Meredith, a loose agreement has been reached that the younger woman will finally, for the first time, tell all.

Rachel is unsure what she is going to get, or whether it will be adequately enthralling for a new book, but the story, when it starts to unfold, astounds her. It concerns a young suburban family entrapped by an intangible but malevolent something, which may have an entirely mundane (i.e. psychological) explanation, or alternatively could be the work of the Devil.

Central to the story are the then-eight-year-old Meredith, known back then as Merry, and her 15-year-old sister, Marjorie. They enjoy a typical sisterly relationship, adoring each other but at the same time adversarial, delighting in catching each other out with naughty, sometimes nasty tricks. Marjorie is the cannier and more dominant of the two, but Merry, while not necessarily adept at this game, is so willing to meet every challenge that Marjorie treats her with a degree of grudging respect, and affectionately calls her ‘Monkey’.

From a reader’s POV, it’s a charming scenario, and something that’s instantly recognisable in happy families everywhere.

The rest of the Barrett clan consists of father, John, a Catholic by upbringing who, since he lost his middle-management job a year and a half ago, is trying to re-energise his religious beliefs, and mother, Sarah, also a Catholic, but one who has grown away from the Church of her childhood and is now skeptical of its teachings.

Worried about their dwindling finances, the parents are going through a difficult patch, but their real problems commence when Marjorie starts displaying erratic behavior. On some occasions, it’s odd but harmless, Marjorie telling her sister some unusually scary and macabre stories, or rearranging her bedroom posters into weird patterns, but on others it’s more sinister, such as when she sneaks into Merry’s room while she’s asleep, and clamps her nose and mouth shut.

Merry, as our main observer, is never quite sure whether Marjorie, a natural mischief-maker, is faking all this bizarre stuff or not. But parents, John and Sarah, have been concerned about Marjorie’s fractious, moody behavior for some time.

Initially, at Sarah’s behest, a psycho-analytical approach is taken, but medical personnel, though they talk to her and prescribe meds (for which they charge handsomely), are unable to fix the older girl’s apparent personality-change, which continues to worsen. One minute she is mocking her father’s belief in Heaven in a cruel, smug way, and the next she is screaming at her parents to get the voices out of her head.