Paul Finch's Blog, page 15

February 8, 2017

Human monsters from a world of darkness

Okay, we’re talking serial killers this week – not exactly a new experience for regulars on this blog, I suppose.

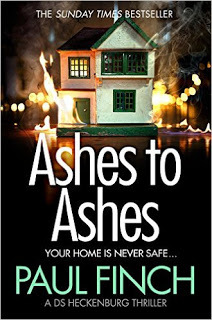

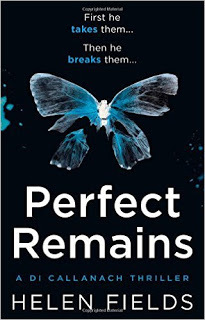

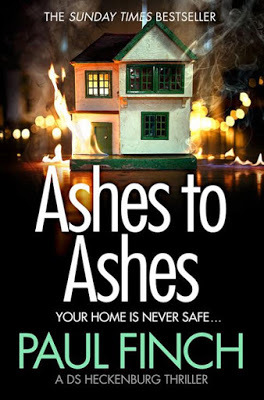

Okay, we’re talking serial killers this week – not exactly a new experience for regulars on this blog, I suppose. But today we’ll be looking at two particular instances of fictional monsterdom: the indescribably terrifying psychopath who haunts the pages of Helen Fields’s new novel, PERFECT REMAINS, which we’ll be reviewing and discussing in full detail, and also the two-handed trail of slaughter and destruction that a pair of rival madmen wreak in my forthcoming Mark Heckenburg novel, ASHES TO ASHES.

I’ll also be reprinting a blog I wrote for GRAB THIS BOOK back in September last year, when I was posed the seemingly simple question: ‘If you had to meet a serial killer, how would you go about it?’

But, first things first. PERFECT REMAINS is a really excellent addition to the fictional serial killer canon. I strongly suspect that its author, Helen Fields, will pretty soon rank among the superstars of the genre. However, as always, my detailed analysis of the book can be found at the lower end of today’s post. Shoot on down there straight away if you wish. But if you’re interested in hearing stuff about Heck as well, hang around here for a bit first.

The most immediately important thing to day about ASHES TO ASHES is that a free sampler – approximately 29 pages of the final, finished text – is now available on Amazon. The book is published on April 6, but if you just can’t wait that long and you want to get a quick snifter of it without having to pay, then I recommend you call in HERE .

For those who are too impatient even for that, here is a quick outline:

The Serial Crimes Unit is hunting a professional torturer called John Sagan, a man who is literally a

The Serial Crimes Unit is hunting a professional torturer called John Sagan, a man who is literally a travelling roadshow of atrocity. He cruises the country, taking his mobile torture chamber with him, and for a not inconsiderable fee he will happily introduce it to anyone a client nominates – though for the most part those he lures into his ‘Pain Box’, as he calls it, are underworld figures who have defied their paymasters and thus are being officially punished. As such, it’s taken a long time for word to get out that Sagan even exists. However, once Heck and the rest of SCU are informed, they go after him full-tilt – only for their first attempted interception to end in disaster, especially for one highly valued member of the team.

Now doubly determined to nab the highly-paid sadist, they pick his trail up again, but this time it leads them to the very last place Heck would have expected or wanted: his grimy northern hometown, Bradburn.

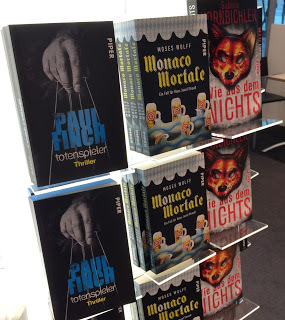

(As a quick aside, I’ve been asked several times now if Bradburn is my own hometown, Wigan, which occupies a similar place on the border between Greater Manchester and Lancashire. The answer is a simple and straightforward ‘no’. Bradburn, though fictional, is Bradburn. The fact that that I recently did a special introduction to the book, and a reading of it in Wigan Central Library – and here’s the photographic evidence – is entirely coincidental).

(As a quick aside, I’ve been asked several times now if Bradburn is my own hometown, Wigan, which occupies a similar place on the border between Greater Manchester and Lancashire. The answer is a simple and straightforward ‘no’. Bradburn, though fictional, is Bradburn. The fact that that I recently did a special introduction to the book, and a reading of it in Wigan Central Library – and here’s the photographic evidence – is entirely coincidental). (On a not-unrelated topic, I'll be doing another of these book events at Blackwell ’ s bookshop, Edinburgh, on Wednesday Feb 15, in company with HELEN FIELDS herself, so keep that date in your diary free).

Anyway, Bradburn, a drab, post-industrial blot on the Northwest English landscape, is a town already in a state of terror. A gang war has erupted between local drugs-dealers and a more powerful mob from nearby Manchester, resulting in a succession of tit-for-tat killings. In that regard, it’s probably a natural hunting ground for John Sagan, who will hire himself to the highest bidder but who, as he enjoys inflicting horrific and agonising deaths on his victims almost as much as he enjoys getting paid for it, is a serial killer in all but name.

And the frightened town’s problems don’t end there. The underworld battle has also attracted another nightmarish figure who will slay for pay – an armoured and helmeted maniac whose murder weapon of choice is a flame-thrower, which perhaps explains his nickname: ‘the Incinerator’.

And the frightened town’s problems don’t end there. The underworld battle has also attracted another nightmarish figure who will slay for pay – an armoured and helmeted maniac whose murder weapon of choice is a flame-thrower, which perhaps explains his nickname: ‘the Incinerator’.Bradburn has never seen anything like this carnage. In truth, Heck has never seen anything like it. Perhaps they can pull together and face this double-headed challenge side-by-side?

But then again, perhaps not.

As those who’ve read the Heck books prior to ASHES TO ASHES will know, Heck and his hometown don’t get on. There are deep wounds there. More than once in the past, Heck has commented that he wouldn’t mind if the entire place was reduced to ashes. Well, who knows … this could be that very moment.

*

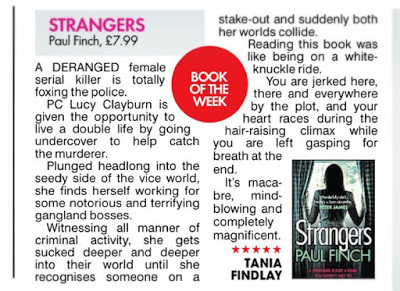

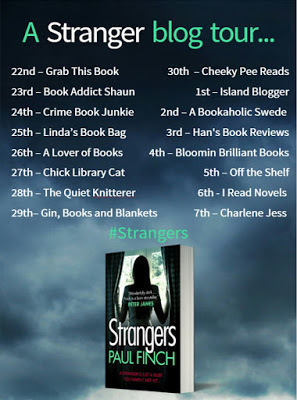

Since the publication of my last novel, STRANGERS , which pitted a young undercover policewoman, Lucy Clayburn, against that rarest of criminals, a female sex-killer, I was grateful to be invited to participate in a number of crime-writing blogsites, to pen a little essay in each case about a different aspect of my work – the way I approach it, my research methods, and so forth.

This is always an enjoyable experience, but sometimes it can be a challenge. Take, for example, this question I was asked last September by GRAB THIS BOOK .

If you had to meet a serial killer, how would you go about it?

It’s a fascinating question. Where would you arrange to meet a serial killer, to interview him (or her) if you had the opportunity? Well, assuming you ever wanted to do that, the location is certainly something you’d have to give considerable thought to.

Even meeting such a person in the controlled environment of a prison would be no guarantee of safety. Far from it.

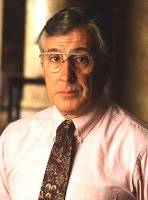

In the 1980s, Robert Ressler (pictured right) was a senior FBI agent who’d investigated a number of serial murder cases. Around this time, he began to devise what we know today as Vi-Cap (or the Violent Criminal Apprehension Programme), which required him to get into the minds of repeat violent offenders and attempt to understand their motivations. As part of his mission, he interviewed numerous multiple murderers in US jails. One particularly disturbing story he later told involved an encounter with a 6ft9in convict who’d killed and decapitated ten victims. The interview was going swimmingly, the convict seemingly cooperating. Ressler felt perfectly safe. They were in the heart of a maximum security facility, under full and constant surveillance by the prison staff – and yet they were alone. Ressler later said that he only realised how vulnerable this made him when his interviewee’s mood suddenly changed, and he said: “Do you realise … if I attacked you now, I could twist your head off before anyone even gets in here.”

In the 1980s, Robert Ressler (pictured right) was a senior FBI agent who’d investigated a number of serial murder cases. Around this time, he began to devise what we know today as Vi-Cap (or the Violent Criminal Apprehension Programme), which required him to get into the minds of repeat violent offenders and attempt to understand their motivations. As part of his mission, he interviewed numerous multiple murderers in US jails. One particularly disturbing story he later told involved an encounter with a 6ft9in convict who’d killed and decapitated ten victims. The interview was going swimmingly, the convict seemingly cooperating. Ressler felt perfectly safe. They were in the heart of a maximum security facility, under full and constant surveillance by the prison staff – and yet they were alone. Ressler later said that he only realised how vulnerable this made him when his interviewee’s mood suddenly changed, and he said: “Do you realise … if I attacked you now, I could twist your head off before anyone even gets in here.”Ressler later described it as a wake-up call with regard to the kinds of people he was dealing with.

This is the important thing, I suppose. Serial killers are not like the rest of us. In fact, they are not like ordinary criminals either.

By their nature, psychopaths lack empathy with others. This doesn’t necessarily mean they are violent – as long as they get their own way. However, add other factors. Such as narcissism, which involves a reckless pursuit of self-gratification (and wherein any opposition, whether real or imagined, is deemed intolerable), and maybe sexual sadism disorder (which speaks for itself), and you’ve got the devil’s own brew and a fairly typical blueprint for the average serial killer.

The other thing to say, of course, is that these people are very plausible.

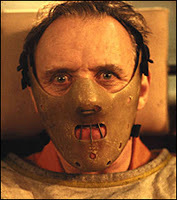

A genius like Hannibal Lecter would be a rarity in real life, but most serial killers are smart enough to know that it will benefit them to conceal their true personality. You only need to look at the numbers of killers who’ve managed to talk their way into people’s houses or have persuaded strangers to climb into their cars, or have used endless other strategies to charm or lure the innocent and gullible.

So, this gift of the gab is something else we’d need to take heed of. Robert Ressler emerged alive from his interview with his 6ft9in nemesis, but for a couple of minutes – because he’d allowed a pleasant demeanour and a glib tongue to fool him – he’d almost become number 11 on the maniac’s butcher’s bill.

In light of that, how can we take them at their word? How can believe anything they tell us? Why would we even expect them to be truthful?

Hannibal Lecter is a good case in point here. Thomas Harris created in Hannibal such a deadly adversary that even the most experienced detectives had no option but to converse with him either through shock-proof glass or with him strapped to a gurney and wearing a mouth-guard. That would certainly be an attractive idea for our interview, but I’d query if the killer would even talk to us under such circumstances.

Hannibal Lecter is a good case in point here. Thomas Harris created in Hannibal such a deadly adversary that even the most experienced detectives had no option but to converse with him either through shock-proof glass or with him strapped to a gurney and wearing a mouth-guard. That would certainly be an attractive idea for our interview, but I’d query if the killer would even talk to us under such circumstances. I’d be surprised if any hardcore criminal, even one who hasn’t committed murder, would be prepared to talk to us about anything unless he or she was getting something in return. Consider that, and then bear in mind that the average incarcerated serial killer is almost certainly facing a full life tariff (and maybe even the death penalty) – and you can see how tough it’s going to be.

At the very least we’d have to be nice to them. So … no straps, no gurney.

And where exactly does that leave us? A rubber room, where there is nothing nasty the killer can put his/her hands on? Maybe, but the killer can still put his/her hands on us …

Might they be prepared to talk to us on the phone over a long distance?

Well, in that case we’re back to the old chestnut: it depends how much info we want. I remember hearing about a US journalist who regularly spoke on the phone to a serial killer serving life, asking his assistance in other unsolved murder cases. At first, the journo got the impression the killer was being helpful. But then he realised that the guy was playing games, imparting some information but on the whole offering just enough to make his correspondent come back for more. In other words, these phone-chats made pleasant breaks for the killer from his otherwise mundane life inside, and he wanted as many of them as possible.

After this, there aren’t too many options open to us.

Ultimately, I suppose, this is a question I can’t answer.

In a novel I’ve got planned for the future, Serial Crimes Unit officer, DS Heckenburg interviews an imprisoned serial killer in a quest for information, but in that one I’m opting for the gentler approach (it all takes place in a ‘soft interview room’, with comfy furniture and pictures on the walls). This female felon is showing contrition, you see, and so she’s deemed by her jailers to be lower risk. But she still wants something in return … and she wants it so badly that Heck has made a judgement call that she won’t try anything stupid.

Will she or won’t she?

At this stage, who knows.

I’m suppose I’m just glad this terrible business is something I write about rather than something I actually do.

*

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

PERFECT REMAINS

PERFECT REMAINS

by Helen Fields (2017)

When ex-Parisian police detective and Interpol agent, Luc Callanach, transfers to Police Scotland, taking up a detective inspector post with the Major Investigations Team in Edinburgh, he isn’t completely a fish out of water. To begin with, Callanach is half-Scottish as well as half-French. He’s also a real bloodhound of a cop, with great analytical skills and a fearless dedication to the cases he is assigned – though on first arriving, it wouldn’t be true to say that he’s completely comfortable with his new environment.

After his sun-drenched days in the Interpol office at Lyon, he finds the Scottish capital windy, wet and dour, and quickly learns that certain officers at his command – the truculent DS Lively in particular – are irritated by his presence because they perceive him to be an outsider who’s been fast-tracked into a plum job.

Moreover, Callanach doesn’t help himself, because rather than attempting to win friends and influence people, he fights back domineeringly against those who seek to undermine him.

The reason for this is simple. Even without his sudden change-of-world, Luc Callanach is a man under astonishingly intense pressure. Back home, he was accused of raping a petulant beauty called Astrid Borde, whose main objection to Callanach was that he showed no interest in her. He wasn’t even charged, never mind convicted – but of course this meant that neither was he able to clear his name, so he left France under such a cloud of suspicion that even his family have now disassociated themselves from him.

He is a good cop who focusses intensely on his job, but even now he agonises over whether he could have handled things better, and as such he is filled with self-doubt, and to a degree, self-loathing.

Ironically, because he needs to be distracted from all this, it’s the perfect time for him to be handed a particularly difficult investigation – on his very first day no less, when what appears to be the burned remnants of an eminent Edinburgh solicitor are found on a Cairngorm hillside. There isn’t much left of the unfortunate woman, but it’s sufficient to reveal who she was and that she died very violently. Callanach throws himself into the case speedily and professionally, but then another prominent local woman – a vicar, no less – is also kidnapped, her tell-tale relics duly found in a drum of chemicals in a dockside warehouse.

Callanach is a by-the-book man. He doesn’t want to look at potential patterns just yet, but it seems increasingly likely that a serial abductor and murderer is at large, his sights fixed squarely on the successful women of the city. Callanach’s methodical approach then faces a serious challenge from within, when DS Lively – badly affected by the second abduction because he knew the victim personally – takes it on himself to call in renowned profiler Edwin Harris, an expert for sure, but a man more interested in promoting his own theories than in catching the actual killer.

Callanach’s protest that this is a breach of protocol falls on deaf ears, because head of the Major Investigations Team, DCI George Begbie, though sympathetic, is currently cash-strapped and has no option but to accept Harris’s assistance as it is being privately funded.

All of this hampers Callanach massively, both in terms of the enquiry and in terms of his personal recovery. Though he doesn’t feel quite so isolated when his friendship grows with fellow DI, Ava Turner, who, though she is currently investigating a different case, is very open – not just to cross-enquiry consultation, but also to afterhours socialising.

Meanwhile, in a parallel thread – and it’s no spoiler to mention this because we are hit hard with this intelligence very early in the novel – a certain Reginald King is hatching a truly heinous scheme. King, a sociopathic loner who work as a lowly admin officer in the Department of Philosophy at Edinburgh University, considers that he’s been at the beck and call of Professor Natasha Forge, Head of School, for quite long enough. In short, King regards himself as a genius and feels that Forge only doesn’t recognise this because she’s a stuck-up bitch. In the long run, he’s going to punish her, but he’s also going to punish lots of other women too. Hence the kidnapping, the imprisonment, the terrible torture and of course the murders.

Problematically for Luc Callanach, Reginald King, despite his lowly status, is a genuinely clever man, whose plan does not just involve a series of revenge killings, but is much, much more wickedly ingenious and twisted than that, and in terms of cruelty, is almost off-the-scale.

There’s one other problem here too, not just for Callanach, but all those who work with him. It’s a coincidence but of course hugely advantageous to the murderer that Natasha Forge’s best friend happens to be DI Ava Turner, another strong, independent woman. So this isn’t going to be any ordinary murder investigation, which all members of the enquiry team can go home from in the evening and relax; as King steadily advances his gruesome grand-plan, things start to get very, very nasty indeed, but also very, very personal …

There are plenty of psycho-thrillers set in contemporary Scotland, and Edinburgh seems to suffer from more than its fair share of fictional serial killers. But Perfect Remains is a very different kind of novel from the norm. Perhaps its most outstanding features are how well constructed it is as a story and how well written as a piece of crime literature. I don’t mean to say that other books of this ilk are not well written, but this one is truly of an exceptional calibre.

As a former barrister, Helen Fields clearly knows her legalities and her procedures inside-out, and yet she weaves them all into this complex and lurid mystery with an effortless, non-fussy style, which informs as much as it entertains, creating a real feel of authenticity but never once cluttering the quick-fire plotline with extraneous detail. In addition to that, her quality descriptive work fully conveys both the time and the place, not to mention the people embroiled in the saga, again without sacrificing any of the novel’s pace. Take one particular scene, for example, when DI Callanach, while stressed out of his mind, finds himself in an amorous clinch with an incidental character called Penny. Penny is little more than a walk-on, and as such could easily be a stock character whom we never think about again, and yet in the space of a page and a half, Fields brings her vividly and sympathetically to life – you almost want to cry for her, she is so unfairly treated by our emotionally distraught hero.

And that was only a member of the supporting cast, so imagine how it is with the leads.

The first thing that strikes me about these more prominent characters is that they are, none of them, free of foibles.

It’s not unusual in crime fiction for our star detective to be damaged, but Luc Callanach takes this to a whole new level. We are told that he is a good-looking guy and at one time he even worked as a male model, and yet none of this info is used to win our favour. If anything, it paints a picture in the reader’s mind of a man who, perhaps back home in his beloved France – which he endlessly and pointlessly yearns for – was rather spoiled. On arrival in Scotland, his initially brusque and rather snippy attitude only adds to this. It’s also the case that what he’s actually on the run from – a rape accusation, for Heaven’s sake! – is the sort of thing that would blemish any police officer’s record for the rest of his career. And after all that, he doesn’t help himself much – at least from the reader’s POV – with a constant, dogged self-analysis which borders on self-obsessiveness. But again, what we’ve got here is a realistically flawed character who needs to work very hard to win his audience over – and, as you might expect, he eventually does so. Firstly, because he’s willing to learn from his errors in order to correct his behaviour, particularly his people skills, and secondly because he’s an excellent detective who doesn’t miss a trick – it is Callanach’s instinct, and his instinct alone, that manage to refocus the enquiry after Lively and Harris send it barking down a blind alley.

In contrast, DI Ava Turner, though another stranger in a strange land (she’s Scottish, but an English-sounding accent born of a private education puts her at a disadvantage), is much savvier in her day-to-day management style, and in the way she handles suspects. She’s an equally tough cop to Callanach, but she’s never less than even-handed: for instance, when she zealously closes down an extremist Catholic sect for brutalising the underage mothers supposedly in their care, her comment to the press that there is “nothing godly about what was happening here” indicates that it isn’t organised religion she has a problem with, but those who abuse it.

Like Callanach, Turner is also single and, under the surface, maybe a little lonely, but she’s learned to ride with the blows and during her downtime is able to relax with friends – as such, she leads a happier, more fulfilled life. That said, her bosom buddy, Natasha Forge, is perhaps not quite so generous a spirit, and this provides us with a key link in the story.

Another confident, professional woman, Forge is pleasant and companionable if she decides she likes you, but terse to the point of being discourteous with office administrator, Reginald King, and okay, while King is without doubt a tad pompous and someone whose academic credentials are at the least dubious, there are times when we as the readers feel that his boss could perhaps be a little warmer towards him.

This of course leads me to King himself, and what I consider to be one of the most powerful pieces of characterisation in the whole novel. For me, Reginald King is so neatly observed and multi-layered an individual that he underpins the entire narrative, and on top of that he must rate as one of the most believable psychopaths I’ve ever encountered in fiction – primarily because, like so many real-life killers, his greatest defence is his total anonymity. King is no drooling Mr. Hyde-type madman, nor is he suave and calculating like Hannibal Lecter. Yes, he is secretly and monstrously narcissistic; he is convinced he is a genius and that the only reason he hasn’t advanced further in life is because those around him are hateful and jealous, and are conspiring in his downfall. But apart from this, he is so, so ordinary. He possesses neither Hyde’s brutish physicality nor Lecter’s sparkly-eyed gaze. He is a simple everyman you could pass in a corridor without batting an eyelid. Incredible though it may sound, there is even an element of pathos in King’s makeup. Because for all the awful things he does – and at times they are truly and torturously awful (and the reader is spared almost none of it) – there are other times when we recognise what a lost soul he is, a guy who, despite attempting civility, can’t even seem to earn the most basic degree of respect from his peers.

Helen Fields has done an all-round amazing job with Perfect Remains . It’s even more remarkable when you consider that it’s her debut novel. A terrific premise is executed to full unforgiving effect in a complex yet pacy procedural, which is peopled by living, breathing characters whom you can easily empathise with (both the heroes and the villains), and which is not only adult in tone but also adult in subtext – there is far more on show here than a simple crime/actioner – but which accelerates during its final quarter to an exhilarating, slam-bang climax.

In short, this is superb stuff – not a whodunit exactly, but an intense and deeply intriguing ‘good vs evil’ thriller, which once you’ve started it is quite impossible to put down. But don’t take my word for it. Just read it. You will not be disappointed – and make a note of the author too, because Helen Fields is a name we’ll be hearing about again and again.

And now, as always, here are my personal thoughts re. casting should Perfect Remains make it to celluloid. It’s just for laughs of course – no-one would listen to me anyway – but this could be a very cool cop series indeed, so it’s got to happen at some point. In the meantime, here are my picks for the leads (as always, with no expense spared):

DI Luc Callanach – Pio Marmai

DI Ava Turner – Gemma Whelan

Reginald King – Gray O’Brien

Natasha Forge – Ruth Millar

DCI George Begbie – Gary Lewis

Astrid Borde – Melanie Laurent

DS Lively – Tommy Flanagan

Edwin Harris – Graham McTavish

Published on February 08, 2017 02:09

January 25, 2017

When terror cuts through to our very souls

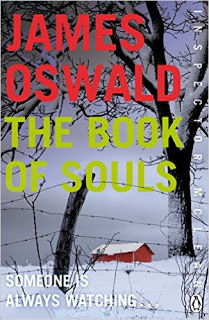

Uh-oh … it’s all getting personal this week, as we take a long, hard look at Scottish crime superstar James Oswald’s hit novel THE BOOK OF SOULS – because trust me, that is one investigation that takes his Edinburgh detective, Tony McLean, very close to home. But also, because we’re going to be talking about the cover to my new Heck novel, ASHES TO ASHES, which you can see right here – yep, this is the next cover, revealed in all its glory – and because we’re going to be discussing why this book will also be visiting a private Hell on its central character.

Uh-oh … it’s all getting personal this week, as we take a long, hard look at Scottish crime superstar James Oswald’s hit novel THE BOOK OF SOULS – because trust me, that is one investigation that takes his Edinburgh detective, Tony McLean, very close to home. But also, because we’re going to be talking about the cover to my new Heck novel, ASHES TO ASHES, which you can see right here – yep, this is the next cover, revealed in all its glory – and because we’re going to be discussing why this book will also be visiting a private Hell on its central character.

Okay, I’m not sure if any of that makes sense. Never mind, all we be explained soon.

In the meantime, if you’re only here for THE BOOK OF SOULS review, you’ll find that, as usual, at the lower end of today’s post. Feel free to skip on down there right away. If, however, you’re equally interested in Heck and keen to know more about the new book, then stick around at this end of the blog.

It’s always difficult when you’ve got a new novel due out, not knowing exactly how much you can and can’t say about it. You obviously don’t want to reveal too much, because that could spoil all kinds of surprises. But by the same token you want to whet as many appetites as possible.

It’s going to be particularly difficult on this occasion, because this unusual cover is likely to excite a bit of debate. And while I want to shove my own oar in, I don’t want to expose too much of the backroom discourse that has gone into the design of this latest novel of mine. That would feel an awful lot like giving away trade secrets.

It’s certainly the case that, in terms of the Heck novels, this cover is very different from everything that’s gone before it. And yet – and this is the really interesting thing – of all the Heck jackets to date, this is the one that I personally think cuts most quickly to the heart of the story (and not just the story, but what I suppose you’d call the subtext of the story).

And there we go – we’re already at a point where I can’t say too much more. You’ll just have to trust me that this cover is very, very relevant to the events in ASHES TO ASHES .

But, on this occasion I think there’s even a bit more to it than that. After all, an effective cover isn’t just about succinctly conveying the meaning of the book. It’s also got to be demography-aware; in other words, it’s got to recognise and respond to its core market. And markets, as we all know, can change on a regular basis.

What I mean is I’m sure that all we writers have our favourite book covers, and we all of us have clear ideas what we’d like to see on the fronts of our books. The problem is: we can’t always have what we want, especially if the marketeers tell us that a more effective alternative is available.

For example, I’ve made it fairly clear over the last few weeks with various Tweets and Facebook posts that one of the main antagonists in ASHES TO ASHES is a ruthless killer whose weapon of choice is a flamethrower. As such, my immediate thought about what I’d like to see on the jacket was something along those lines: a menacing figure in a visored helmet, wearing fireproof armour, perhaps driving a spear of flame right into our faces.

But you know, that wouldn’t have been massively original.

But you know, that wouldn’t have been massively original.Imagery of that sort has adorned games, comics and movie posters for decades (like this one on the right, from the third-person shooter game,

Tom Clancy’s The Division).

In addition, it tends to be associated more, I would suggest, with war-themed products, or something in the realms of a horror or sci-fi style Armageddon.

So when I heard that we weren’t going to use any such image on the cover of ASHES TO ASHES I was surprised, but only for a short time – before it occurred to me that it wouldn’t necessarily have made our target audience (the crime thriller crowd) looking twice.

And making you look twice is the key thing these days, especially when so many book covers are first seen online, usually as thumbnails (which also explains the big wording, and perhaps the less startling, less garish imagery than we used to see).

We’ve tried all sorts of tricks in the past to get potential audiences to spot our novels on the shelves: from racy pictures of gun-toting babes in heels and stockings, as inspired by 1960s spy thrillers; to more ghoulish subjects – corpses in sacks, dead hands with flies on them, rotted doll faces etc, as driven by the craze for ‘true crime’ books following on from Truman Capote’s seminal In Cold Blood; to the stark photographic images of masked killers, brutal weapons and captives-in-peril that represented the more realistically violent fashions of the 1990s and 2000s.

We’ve tried all sorts of tricks in the past to get potential audiences to spot our novels on the shelves: from racy pictures of gun-toting babes in heels and stockings, as inspired by 1960s spy thrillers; to more ghoulish subjects – corpses in sacks, dead hands with flies on them, rotted doll faces etc, as driven by the craze for ‘true crime’ books following on from Truman Capote’s seminal In Cold Blood; to the stark photographic images of masked killers, brutal weapons and captives-in-peril that represented the more realistically violent fashions of the 1990s and 2000s. Even now, we see a wide variation dependent on the booksellers’ experience. Nordic Noir, for instance, often announces itself by portraying cold, desolate landscapes. British urban noir tends to focus on diminutive figures set against the immense backdrops of nighttime cities. Massive gangland sagas, or crime thrillers concerned with international intrigue often use subtle glamour – female beauty, jewelry, diamonds, casinos and the like.

Even now, we see a wide variation dependent on the booksellers’ experience. Nordic Noir, for instance, often announces itself by portraying cold, desolate landscapes. British urban noir tends to focus on diminutive figures set against the immense backdrops of nighttime cities. Massive gangland sagas, or crime thrillers concerned with international intrigue often use subtle glamour – female beauty, jewelry, diamonds, casinos and the like.So where does all that leave the cover for ASHES TO ASHES ?

Good question. Heck’s been around a bit for sure. He too has done the diminutive figure and the captive-in-fear thing. But this new cover is quite clearly something else. Very different, as we’ve already said. Eye-catching – I certainly hope so. And maybe – just maybe – a tad domestic in tone?

Domestic?, you ask.

Well, I’ve already said that I can’t reveal too many details about this new novel. But as I’ve also said, it’s a particularly personal story where DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg is concerned, and it cuts very, very close to home.

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS …

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

THE BOOK OF SOULS

THE BOOK OF SOULS by James Oswald (2012)

There can be few officers in the Lothian and Borders Police (as they were before ‘Police Scotland’) who’ve had a harder time of it than DI Tony McLean. A veteran homicide investigator whose normal beat is the grimy backstreets of Edinburgh, he thinks he’s seen and done it all, but as this second investigation in the McLean canon opens, the likeable but lonely detective finds himself under intense emotional pressure.

First of all, it’s nearly Christmas, which means the anniversary of the murder of his fiancée, Kirsty Summers, who was the final victim of Donald Anderson, an antiquarian book-dealer by trade and ritual sex-slayer nicknamed ‘the Christmas Killer’ by hobby. Every year for ten years, one of Anderson’s victims – invariably a young female – after being bound and raped in the cellar of Anderson’s shop, was found with her throat cut in one or other of the city’s filthy waterways. Kirsty Summers was only the most recent, and the last girl to die before McLean, then a detective constable, finally put an end to Anderson’s reign of evil. Needless to say, with it now being Christmas again, all the bad memories come rushing back. It’s a minor consolation – of sorts, when McLean learns that Anderson himself has now died in prison, the victim of a brutal attack by a fellow inmate. He even attends the funeral in Aberdeen just to ensure that he’s saying goodbye to bad rubbish.

But then, almost as soon as McLean returns to Edinburgh, another series of murders commences, which is almost identical to the one before: young women abducted, indecently assaulted and deposited in the city’s culverts and streams with throats slashed from ear to ear. To confuse things even more, a couple of occasions follow when McLean thinks he spots the deceased murderer walking the streets of Edinburgh, though of course, despite strenuous efforts, he’s never actually able to lay hands on anyone who looks even vaguely similar.

Despite this, our bewildered hero finds that he has the full confidence of his senior supervisor, Chief Superintendent Jayne McIntyre, but on this occasion he finds resources restricted because the bullish but somewhat empty-headed DCI Charles Duguid, known to his colleagues simply as ‘Dagwood’, has commandeered almost everything as part of the major anti-drugs operation he is running in the city, and deeply resents that McLean is leading a rival investigation.

At the same time, an unknown arsonist has been setting buildings alight all over the place. Most of these are disused industrial units, but then the block of flats in which Tony McLean himself lives is also torched, and several residents die in the process. This, in its turn, reveals that drugs production activity was occurring in McLean’s own building, right under his nose in fact, which is a huge embarrassment for him and deeply frustrates Chief Superintendent McIntyre, who insists that he’s overly stressed and must now attend psychological counselling sessions. This puts McLean in the clutches of irritating police-shrink, Prof. Matthew Hilton, who’s hardly the DI’s favourite person given that he interviewed Donald Anderson on his arrest and later tried to persuade the court that Anderson’s bizarre excuse for his crimes – namely that he was driven to kill by the evil contained in an ancient book – surely proved that he was insane.

In the midst of this seething tension, the copycat killer’s victims pile up, which only adds fuel to the fire in that a local journalist, Joanne Dalgliesh – in her efforts to sell a sensational new book – begins to air suspicions that Donald Anderson, evidently a mentally ill man, was framed by the original investigation team and now has died unjustly.

There will clearly be no rest this festive season for McLean and regular sidekicks like DS ‘Grumpy Bob’ Laird and station archivist John ‘Needy’ Needham. McLean gets some welcome assistance from the attractive DS Kirsty Ritchie, who is drafted in from Grampian Police, but finds he has very little time to devote to the potential new woman in his life, Emma Baird, who works for the police as a crime scene technician, and who, in truth, McLean is not sure he is right for.

It certainly seems as if nothing is going right. Even the glitz of the Christmas season, which is always there in the background, feels far removed from the cold, sterile offices in which McLean and his team must work, or the gloomy, half-empty house of McLean’s lately-dead grandmother, where he now must dwell. To match this mood, the weather switches regularly between snow and rain, constantly and consciously defying the yuletide spirit, creating a near constant aura of winter desolation.

But no evil lasts forever when good guys are on the case. A break finally comes along – but it’s a curious one. McLean first meets elderly cleric, Father Noam Anton, when he arrives at the detective’s door with a bunch of carol singers. But then he receives a second visit on Christmas Day itself, when Anton tells Mclean that he knew Donald Anderson well – the guy was originally a member of his monastic group, the Order of St. Herman, who among other duties, were charged with keeping rare books. Anton claims that Anderson, a tortured individual, stole a number of valuable volumes, including the Liber animorum, or Book of Souls, which legend claims was dictated to a deranged medieval monk by the Devil himself. This, Anton says, became the eventual cause of Anderson’s murderous depravity.

McLean is frustrated by this story – he believes it yet more excuse-making for a sexually degenerate serial killer – especially as there is no trace of the book now. To his mind that probably means it never existed, though an alternative – if somewhat fanciful – explanation could be that the Book of Souls has found its way into someone else’s hands and is now exerting the same malign influence as before, thereby creating another ‘Christmas Killer’.

It’s difficult to say more about the synopsis of The Book of Souls without giving away enormous spoilers, because there are several humungous twists and turns still to come in this complex and alarming tale (including one truly colossal head-spinner right near the end), but suffice to say that, whether he likes it or not, Tony McLean – ever more determined to catch the latest killer, and at the same time prove that he got the right one before – finally opens to the possibility that the answer to this mystery may lie in the occult …

One of the most interesting aspects of the Tony McLean books, at least in my view, is their regular supernatural undertone. Even though these are good, strong police procedurals – and The Book of Souls is no exception to that – you never get the feeling you have strayed very far from ‘the other world’. This intrigues and enthuses me because it’s often been said that horror and crime as rival subgenres simply don’t match, that there can’t be any overlap between the two because the rationale behind both forms of fiction should almost always work to cancel the other out.

If that is your resolute view, then James Oswald is definitely the fly in your ointment, especially when it comes to The Book of Souls . However, at first glance, what we're dealing with here is undeniably a cop thriller.

DI McLean is a little bit of an archetype in that regard: a flawed, tired loner in the midst of a mean city, almost invariably faced by opponents whose depths of wickedness know no bounds. Despite this, he’s an attractive figure; instinctively good at his job and no-one’s fool, but affable with it, trusting of colleagues (at least, those he rates), and yet monstrously unfortunate. I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a fictional copper who suffers as much bad luck as Tony McLean does, but he’s very well written too, a weary Scottish everyman, which makes him a character you root for from page one.

So far so familiar, of course. This is solid cop novel territory, especially when McLean and his team get a hint that a copycat murderer is on the loose, leading them a non-too-merry dance from one corner of Edinburgh to the next, and these, it won’t surprise you to learn, are locations distinctly absent from the tourist trail: we’re talking derelict factories, rundown tenements and rubbish-strewn lots where sewer outlets swim with disgusting effluent.

But for all this, we’re aware from an early stage that there’s something curious going on here. McLean’s occasional sightings of the deceased Anderson are an eerie touch, but Oswald handles them most effectively, restricting them to brief glimpses in the thronging city streets. These weird events are so scant that it’s actually quite easy to feed them into Jayne McIntyre’s concerns about McLean’s fragile mental state. Even we, the readers, who are 100% on McLean’s side, might fleetingly wonder if it’s all been a bit too much for him, and if maybe these psychological counselling sessions are actually a good idea – but then of course we dismiss such concerns, because McLean is the hero while police shrink/profiler Matthew Hilton is a pillock of the first order.

So … does this mean that something genuinely strange is happening? Could it conceivably be that what McLean is seeing is Donald Anderson’s ghost? It’s an increasingly unnerving thought given what McLean knows about Anderson’s past: the esoteric bookshop he kept and the foul rituals that happened in its basement. Then add to this the emerging information about the so-called Book of Souls, a demonic tome, which according to Father Anton, does not just possess its owner like an evil spirit, but gradually drains his or her entire soul.

Separate all that stuff from the police procedural, and you are in pure horror story country. But the real strength of this novel is that Oswald doesn’t do that; he splices the two threads together neatly, creating a fast-moving, ultra-dark thriller, which in no way contradicts itself and thoroughly entertains from beginning to end.

Possibly not one to read on a bright, sunny day – I’ll admit that much – but no sooner will the spring and summer be here, than winter will be coming round again in due course, and if you like your crime fiction hard-edged, dark-toned, and you aren’t disaffected by the festive spook story tradition, this could well be one for you.

As always at the end of a review, I’m being cheeky enough to suggest the cast I would choose were this book ever to make it to film or TV. Obviously, as The Book of Souls is number two in the McLean series, it would only be right for the eponymous hero’s previous outing to hit the celluloid first, but this is the bit where we always suspend belief anyway (on that score, wait till you see who I’ve chosen!!!).

DI Tony McLean - Ewan McGregorEmma Baird - Rose LeslieDS Kirsty Ritchie - Georgia KingSgt. John ‘Needy’ Needham - David O’HaraFather Noam Anton - Peter MullanDS ‘Grumpy Bob’ Laird - Tony CurranDCI Charles Duguid - Peter CapaldiCh. Supt. Jayne McIntyre - Tilda SwintonDonald Anderson – Clive RussellJoanne Dalgliesh – Zoe Eeles

(Ah, yes … another of those wonderfully expensive cast-lists that only someone of my limitless resources can assemble).

Published on January 25, 2017 08:28

December 1, 2016

Admit it, you're all just dying for Christmas

I don’t know about you, but whenever we get to December, I start thinking scary. I’m sure it’s as much to do with the short days, long dark nights and desolate, frozen landscapes as it is our midwinter tradition of telling ghost stories, though in truth, I don’t think any of us really need a reason. I now automatically associate the waning of the year, especially the days leading up to Christmas, with genuinely creepy tales – no nursery stuff about elves and pixies in this neck of the woods.

In that spirit, I’m this week reviewing an especially frightening horror novel, which also happens to be set in the depths of winter, in fact one of the darkest, coldest winters you could imagine: Michelle Paver’s thoroughly terrifying DARK MATTER. However, before we get to that - as usual, you’ll find a full review and discussion of that novel towards the lower end of this post - a word or two about my own ‘ghost story for Christmas’ output ...

Some of you may be aware that around this time each year, I’m in the habit of posting one of my own Christmas terror tales right here on this blog. There’ll be no exception to that rule this year, though as it’s not quite Christmas yet, you’ll need to tune in for a that a little later in the month. I've got no actual date for it yet, but it will be in a couple of weeks’ time and before December 24.

This year’s offering will be THE UNREAL, which features a ghost-hunter holding a solo vigil in a supposedly haunted theatre on a very cold and lonely Christmas Eve.

Before then, I’m going to make use of the time of year to unashamedly pimp some of my other Christmas stories - so apologies for this in advance. All have been published in the relatively recent past, but they may well have skipped your attention as they only tend to appear on readers’ radars between October and December.

The most obvious one that springs to mind is my novella of 2010, SPARROWHAWK , which has been reviewed in the following terms;

A supernatural feast in more ways than one.

The author superbly captures the atmosphere of 19th century London; the plot is gripping from the outset.

A Christmas tale with a twist that is captivating.

SPARROWHAWK is one of my favourite novellas, as it contains what I still consider to be some of my best writing. It follows the fortunes of Captain John Sparrowhawk, a veteran of the Afghan War of the early 1840s, who on surviving a campaign which saw all his men killed, returns home shell-shocked to find that his depressed wife has died during his absence. Resigning his commission and falling into drink and gambling, he soon runs up debts, which finally see him incarcerated in the terrible Fleet Prison.

This is where the story actually opens; with Sparrowhawk at his wits’ end after one whole year on Debtors’ Row, and no apparent way to purchase his liberty – until, very unexpectedly, and just as a bitterly cold December descends on London, the beautiful and enigmatic Miss Evangeline offers to pay his debts on the condition he will do a job for her: protect an unnamed middle class family against an unspecified foe for the duration of the Christmas period.

With nothing to lose, Sparrowhawk takes the job, but soon finds himself pitted against a very dangerous opponent – a supernatural entity with many and varied forms, which quickly takes advantage of the thick frost, freezing fog and heavy Yuletide snow, and wastes no time in using fragments of Sparrowhawk’s own tragic past to torture him.

Here’s a quick extract:

Sparrowhawk advanced a few yards into the park. As always, the moonlight reflected brilliantly from the snow, and at first he saw nothing. But then, gradually, he became aware of a heavy-set figure about thirty yards to the left of the bandstand. It stood perfectly still and watched him. He continued to advance, steadily. If this fellow was nothing more than a curious passer-by, the shotgun would involve some awkward explanations, but Sparrowhawk was playing for high stakes here, and he kept the weapon levelled.A few yards more, however, and he relaxed again.The figure was a snowman.Some children must have built it during the day, though when he circled it, it struck him as odder than usual. It had no features – no lumps of coal for eyes, no traditional carrot for a nose, yet someone had stuck a cigar where its mouth should be – a full-sized Cuban cheroot of the sort Sparrowhawk favoured but couldn’t afford. Likewise, the evening coat and top-hat, the former of which was velvet, the latter silk, made for expensive adornments. Even though the figure had no eyes, he felt as though it was looking straight at him. He contemplated knocking the thing down and trampling it, but decided that this would be cruel on the children who’d built it. At the very least he could take the cheroot, though it occurred to him that maybe the cheroot had been left here specifically for that purpose and that it might have been tainted in some way. On reflection, that seemed a little ridiculous, though of course stranger things had so far happened. Sparrowhawk resumed his patrol, ignoring the snowman further. The rest of his shift was uneventful, and in the morning he went back to his residence. When he returned the following evening, he noticed that the snowman had gone. He wandered around, but there was no trace of it. There wasn’t even a clump of messy snow where it had stood. The surface was smooth, unbroken – even though there hadn’t been another snow shower for the last couple of days.

SPARROWHAWK is a special case really, as on penning it, I didn’t set out with the sole intention of writing a horror story. If I say so myself, I think it’s a lot bigger than that, hence it’s length – at 40,000 words it’s a novella rather than a short. There ishorror in there – ghosts, monsters and festive frights – but I think it’s more a tale of self-discovery than anything else, with lots of romance as well, some Dickensian-era social drama, and lashings of the traditional Victorian Christmas.

If you’re looking for some more typical seasonal terror, I’m still rather proud of

IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER

, which was first published in November 2014 (and republished this year in Germany, both electronically and in paperback, as

DAS GESPENST VON KILLINGLY HALL

) and which collects five of my Christmas horror stories. In this case, it’s exactly what it says on the tin: a bunch of seasonal chillers designed to make your hair stand on end. Here are some tasters and some short extracts:

If you’re looking for some more typical seasonal terror, I’m still rather proud of

IN A DEEP, DARK DECEMBER

, which was first published in November 2014 (and republished this year in Germany, both electronically and in paperback, as

DAS GESPENST VON KILLINGLY HALL

) and which collects five of my Christmas horror stories. In this case, it’s exactly what it says on the tin: a bunch of seasonal chillers designed to make your hair stand on end. Here are some tasters and some short extracts:THE CHRISTMAS TOYS

Two burglars target an ordinary suburban house one Christmas Eve, only to awaken the dark side of the festive spirit …

… it appeared to be an entire representation of Bethlehem in miniature. Fleetingly, Tookey was touched by long ago memories of his infant school days, when the hopes and fears of all the years had seemed to apply to him as much as all the other kids. The flat-roofed houses were brown or beige, as if moulded from mud-brick, the glow of mellow lamplight visible from each interior, donkeys and camels yoked outside. In the very centre, on a raised mound, there was a stable, its frontage removed, revealing a baby in a manger and toy soldier-sized figures of Mary and Joseph kneeling one to either side. Above them, a single star was suspended. Somewhere on the floor one of the wires to the fallen Christmas trees sparked, and the star began to shine with a pale, silvery luminescence. At the same time figures started moving in the town. Tookey watched in fascination as three or four men – again no more than toy soldier size – but distinctly sinister in hoods and cloaks, and with curved daggers, roved up and down the narrow streets, moving along electric runners which he hadn’t noticed previously. One by one they visited each house, the internal light to which would then turn blood-red – to the accompaniment of tinny shrieks.“What the …?” Tookey breathed. He had some vague memory of a school lesson during which he’d been told about that bad-tempered bastard – wasn’t his name ‘Herod’? – having all the babies killed to try and get to Jesus.

MIDNIGHT SERVICE

A stranded traveller in a desolate town one snowy Christmas Eve. Where can he find shelter? The former workhouse, of course …

… it was ludicrously dark. There didn’t seem to be any windows down there, not even small ones. On one hand this shouldn’t surprise him: he knew all about the old workhouses and how they’d been designed to be as uncomfortable as possible, to deter all but the most desperate poor; but on the other hand, if someone insisted on re-adapting one of those aged buildings for more modern use, was it asking too much that they update it a little? At the bottom of the stairs, he blundered into a damp, musty hanging – and only when he struggled past that did he at last see light: Christmas firelight shimmering around what looked like tall sections of flat, theatrical scenery. He shrugged his ram’s costume onto his shoulders as he sidled his way through. Somewhere ahead, he could hear whispers and titters of anticipation. It seemed the audience was in place.Then a woman stepped into his path.He recognised her as the woman he’d seen earlier. Her costume was rustic Victorian – that ground-length skirt, that shawl, that coal-scuttle bonnet from beneath which wisps of stringy, metal-gray hair protruded. But like Reverend What’s-His-Name, she was incredibly old, her face wizened as desiccated leather, her mouth a toothless, crumpled maw, her eyes milky, sightless orbs.

THE FAERIE

Timid husband Arthur snatches his young daughter and flees his angry wife across the wintry moors, finally seeking sanctuary in a mysterious snowbound house …

The house was now directly above them. Thanks to the flurrying flakes, much of it was still hidden, but his first guess looked to have been correct. It was about the size of an old barn, but its windows – in particular the two bay windows at the front – though mullioned, were almost certainly a recent installation. The mellow light that flooded out of them was extremely comforting.“Come on,” he said, unfastening his seatbelt and zipping his anorak up. He switched the engine off, and they climbed out of the car together. Initially the wind took their breath away; it had a sword’s edge, and a sword straight from the Pole. Snowflakes fluttered in their faces like moths as they fought their way up a tall flight of steps, which, thanks to each tread being several inches deep, were highly treacherous.At the top, they advanced along a short path – only visible as a linear and slightly sunken section of snow – until they saw the front door. It was impressively tall and wide, with a carved pediment over the lintel; it looked like a symbol of the sun with a tree growing against it. The door itself was of solid oak with a big brass knocker.

“It’s a grand-looking place,” Arthur said. “Can’t think what it’s doing all the way out here in the wilds of Derbyshire.”He reached for the knocker, but the door creaked open as soon as he touched it.

“It’s a grand-looking place,” Arthur said. “Can’t think what it’s doing all the way out here in the wilds of Derbyshire.”He reached for the knocker, but the door creaked open as soon as he touched it.They glanced through, and saw an arched stone passage with low wooden beams across its ceiling. It ended at a flight of four broad steps, which led up into a living area. A rosy flush of firelight was visible up there, and a pleasant scent struck their nostrils, a combination of oranges and cinnamon, and something else – evergreens.

THE MUMMERS

Two men plot an elaborate Christmas Eve revenge by summoning a pantomime from Hell …

Phil glanced around at a gilt-framed portrait propped in a corner. It was done in dark oils and had been varnished in order to preserve it. Much of the varnish was now dirty and yellowed, but through it the deeply-troubled visage of Hugh Holker was still visible; an elderly man with sagging jowls, a heavily furrowed brow and thick grey tufts for sideburns. Phil had been in to look at the picture several times already, and still found it compelling. The artist had depicted Holker leaning forward on his fist, in a posture of dignified contemplation, but had etched despair and even fear into the final composition. The old industrialist’s eyes bore a stark quality, as if some ghastly apparition had just materialised before him. In the background meanwhile there were indistinct mist-forms, swirls and eddies of smoke or fog, which might have had more to do with the picture’s age than the artist’s intent, but which were ominously obscure all the same.“… to save us all from Satan’s power when we were gone astray,” sang Perry.With a pang of unease, Phil was reminded of his purpose here. He glanced at his watch – it read seven-thirty; time was ticking away quickly. Almost too quickly. He shivered – trepidation, anxiety, fear, all mixed in one; but then he heard again the raucous, gluttonous shouts filling the room behind him, and his nerves settled. What was it Eric had said? That this was an experiment? Yes, and Phil too was keen to see the result.

THE KILLING GROUND

THE KILLING GROUNDDuring an atmospheric English Christmas, man and wife security experts are hired to protect a film star’s family from the cannibal woman said to haunt their new country estate …

“Ruth, this is like the biggest load of crap in the history of humanity.” Alec zipped up his fleece jacket and stood shivering in the snow. It was ankle-deep, and flakes were falling steadily. They both stared up at the window to Claudette Duvalier’s bedroom. “Are you telling me someone couldn’t climb up there?” Ruth said.The window was some twenty feet up, but ten feet below it a kitchen-annex abutted outwards four yards or so. In keeping with the general architecture this too was castellated, but that wouldn’t present a major obstacle. To prove her point, Ruth clambered lithely up the drainpipe beside the kitchen window, scrambled over the mock-battlements, and then had only ten feet of sheer wall to scale. That might have been more difficult had it not been densely clad with ivy. She only had to ascend a few feet to prove it would easily hold someone of her weight. She jumped back down and stood next to her husband, beating fragments of leaf from her gloved hands.“Satisfied?”“No I’m not,” he said. “You’re wearing sweats and trainers. We’re talking about a woman in a long dress.”“Rags. Not exactly a long dress.”“Okay, you’re in peak physical condition. We’re talking about a woman who’s been dead nearly nine-hundred years.”

More recently, last Christmas in fact,

DARK WINTER TALES

was published. While this didn’t specifically include tales of horror associated with the Christmas season, it was published last December because my publishers at Avon (HarperCollins) were interested to see how well a collection of dark and spooky tales would sell at this time of year. There are only one or two supernatural stories in here, but all were selected (hopefully) because they are dark and suitably nightmarish in tone. Anyway, as above here are a few tasters and extracts:

More recently, last Christmas in fact,

DARK WINTER TALES

was published. While this didn’t specifically include tales of horror associated with the Christmas season, it was published last December because my publishers at Avon (HarperCollins) were interested to see how well a collection of dark and spooky tales would sell at this time of year. There are only one or two supernatural stories in here, but all were selected (hopefully) because they are dark and suitably nightmarish in tone. Anyway, as above here are a few tasters and extracts: THE INCIDENT AT NORTH SHORE

A policewoman is summoned by her secret lover to an illicit tryst in an abandoned theme park. Unfortunately, it’s the same night that a homicidal maniac has escaped from the nearby asylum.

Sharon stood by the barrier and phoned him again. Still it went to voice-mail. “Geoff!” she said under her breath. And then, because frankly she couldn’t take much more of this: “Geoff, where the hell are you?”A voice replied. At first she thought it was another echo, though on this occasion it sounded as if it had come from inside the Haunted Palace. She ducked under the barrier and stood at the foot of the access ramp, on which only eroded metal stubs remained of the rail-car system. The door at the top stood ajar. Finally, she ascended. It had definitely sounded as if the voice had called her by name. So it was Geoff. But if so, why didn’t he come out? She approached the door, the glare of her torch penetrating the gaunt passage beyond but revealing very little. When she entered, it stank of mildew. The ghostly murals that once adorned the fake brick walls had mouldered to the point where they were unrecognisable. She ventured on, turning a sharp corner – no doubt one of those hairpin bends where, for their own entertainment, everyone inside the car would be thrown violently to one side – and stopped in her tracks.A tall figure stood in the dimness, just beyond the reach of her torchlight.“Geoff?” she said, in the sort of querulous tone the general public would never associate with a police officer on duty.The figure remained motionless; made no reply.“Geoff?”Still no reply; no movement. She advanced a couple more steps, the light spearing ahead of her. And then a couple more, and finally, relieved, she strode forward boldly.It was a department store mannequin, albeit in a hideous state: burned, mutilated, covered with spray-paint. Up close, its face had been scarred and slashed frenziedly; for some reason, she imagined a pair of scissors …

CHILDREN DON’T PLAY HERE ANYMORE

A retired detective can’t give up on his last unsolved case. Who killed the young boy in the quiet stretch of woodland? A final clue reveals a horrible truth.

As I perambulate downhill, it strikes me as immensely sad how modern children are denied the youth of wild adventure that Geoff and others like him enjoyed. A wood like the one at the bottom of the Dell should not be silent and filled with undisturbed shadows; courting couples sneaking off into its undergrowth should not go unspied-upon; tadpole-filled ponds like the one deep in the middle here should not remain unplundered.But that is the way of it these days. And with good reason. The murder of Andrew Conroy was really quite horrible. More so from my point of view, perhaps, because I knew the kid personally. He was a contemporary of Geoff’s … went to the same school and scout troop, was a member of the same swimming club. Don’t ever believe it if someone tells you that police detectives get hardened to the slaughter of the innocents.Especially don’t believe it if those police detectives happen to work in their home town …

TOK

A series of strangulation murders are apparently committed by someone with non-human qualities. Bernadette suspects the weird stuffed creature in her in-laws’ gloomy old house.

The Bannerwood wasn’t by any means a problem housing estate, being privately owned and suburban in character. But it was vast and sprawling, and on first being built it was occupied mainly by young families, which soon meant there were lots of children gambolling around – so many children, as Miriam Presswick would complain. Children in gangs, children running, children shouting, children screaming – and children encroaching, always encroaching, finding ever more reasons to trespass on her property: in summer chasing footballs or playing hide and seek among her trees, in autumn trick-or-treating or throwing fireworks onto her lawn. Berni didn’t know whether such persecutions had actually taken place or were purely imaginary, but given Miriam’s personal history it was no surprise that her sense of embattlement had finally become so acute that she’d had the outer wall erected, cutting herself off completely from the busy world that had suddenly encircled her. Despite that, but not atypically of psychological breakdown (not to mention advancing senility), even this security measure had in due course proved insufficient. In the last year alone, Miriam had contacted her son on average once a week to complain that people were trying to climb over the wall, were scratching on her doors, tapping on her windows. Nonsense, of course. Utter nonsense. Though Don had not admitted that. He would never have the guts to be so abrupt with his mother. He’d tried to calm her, tried to reassure her that she was imagining it – to no avail. And then, this last week, the murders had started.

The Bannerwood wasn’t by any means a problem housing estate, being privately owned and suburban in character. But it was vast and sprawling, and on first being built it was occupied mainly by young families, which soon meant there were lots of children gambolling around – so many children, as Miriam Presswick would complain. Children in gangs, children running, children shouting, children screaming – and children encroaching, always encroaching, finding ever more reasons to trespass on her property: in summer chasing footballs or playing hide and seek among her trees, in autumn trick-or-treating or throwing fireworks onto her lawn. Berni didn’t know whether such persecutions had actually taken place or were purely imaginary, but given Miriam’s personal history it was no surprise that her sense of embattlement had finally become so acute that she’d had the outer wall erected, cutting herself off completely from the busy world that had suddenly encircled her. Despite that, but not atypically of psychological breakdown (not to mention advancing senility), even this security measure had in due course proved insufficient. In the last year alone, Miriam had contacted her son on average once a week to complain that people were trying to climb over the wall, were scratching on her doors, tapping on her windows. Nonsense, of course. Utter nonsense. Though Don had not admitted that. He would never have the guts to be so abrupt with his mother. He’d tried to calm her, tried to reassure her that she was imagining it – to no avail. And then, this last week, the murders had started. GOD’S FIST

When a disgraced cop allows the violence of modern life to explode in his mind, an odd experience in a church confessional sends him on a mission to clean things up.

As a former cop, Skelton knew John Pizer of old; at least he knew about him. He knew for instance that Pizer – who’d begun his illustrious career offering protection to hotdog vendors outside football stadiums, but who then served time for GBH and later progressed as muscle for larger, wealthier outfits – now dabbled in smack, Ecstasy and illegal steroids, and ran sections of the red-light district, providing outlets where the hardest of hardcore porn was available, and controlling the dozens of goodtime girls who waited in the salons and parlours, or if they were drabber, skinnier and more visibly damaged by the life, in the roach-ridden alleys and backstreets where only the most desperate punters would seek them out. Pizer had now attained that relatively secure underworld status where he continued to reap the rewards but rarely got his own hands dirty, instead having numerous fall guys, or in his case girls, to take the rap. “Hey, John!”Pizer halted. It was just after eight, and he was taking his normal morning walk with his young pit-bull, Ivan. He was dressed in a snazzy designer running suit and flash trainers, but, as always, was distinctive with his gold-encased hands and his pink, shaven dome. Even so, he hadn’t expected to meet anyone he knew. He was cutting through a narrow ginnel to the park when he heard the voice. He turned – a tall, heavily built man, wearing jeans and a denim jacket, with a shock of black hair and dense black sideburns, was approaching.“Who are you?” Pizer asked. Beside him, Ivan started to growl.Skelton smiled. “Got a message for you.”“Yeah?”“From God.”Pizer looked puzzled. “Uh?”Skelton jerked his right arm forward, the monkey wrench shooting out from his denim sleeve, landing neatly in his right palm. “But this white-trash ornament gets it first.” He smashed the heavy tool down on the pit-bull’s head …

WHAT’S BEHIND YOU?

WHAT’S BEHIND YOU?Art students think it’ll be a hoot to walk one-by-one through the supposedly haunted rectory. But it’s unnerving to be told that whatever they hear behind them, they must never look round.

“There have been shipwrecks on that coast throughout history,” he said in his melodious Welsh voice. “And it’s entirely possible the injured and dying were brought ashore at Rhossili Bay and perhaps spent their final minutes in Rhossili Rectory, a remote structure at the foot of Rhossili Down, and at one time the only habitation in the vicinity. There were also stories that this Rectory was built on the site of a Dark Age monastery, sacked by the Danes and later buried in sand during a tempest.” I remember that he watched us all closely as he spoke, smiling like a cat. He had a thick, red/grey brush of a beard and moustache, and round spectacles. His eyes, which were very green, twinkled like jewels beneath the rim of his fedora.“However,” he added ominously, “none of these potentially dramatic events can really explain the true depths of fear and despair this unholy presence has caused. You see, gentlemen … you must never turn and look. That is what they say.” We exchanged baffled glances, and he chuckled in that hearty way of his. “Rhossili Rectory is now ruined and empty, and according to the story, an evil spirit haunts it. One can only surmise that it may be connected to the historical events I have mentioned. But whatever its origins, the locals don’t take this as a joke. You’ll notice that when we arrive. The Rectory is far along the beach from Rhossili village and the boarding house where we’ll be staying. It’s very isolated – people do not go there.” “What form does this spirit take?” Flickwood asked, sounding nervous.“Oh, Mr. Flickwood … you walk through that ruined building on your own, day or night, and you will find out. I guarantee it.”

THOSE THEY LEFT BEHIND

The mother of the last man in England hanged becomes obsessed with the plastic head she sees on the market. When she learns it was part of a hangman’s dummy, she knows she has to have it.

Out of professional necessity, Shirley had already researched the events surrounding Tommy Dawkins’s execution. He’d been found guilty of murdering a girl called Mary Stillwell, who’d lived next door. Apparently he’d also mutilated her, quite horribly. No-one had really understood why he’d done it. Had there been something going on between them? Had Mary Stillwell resisted a sexual advance maybe? No answers were ever provided. But this had happened in 1965, and the twenty-year-old was subsequently tried, and, as he’d already confessed, was convicted and sentenced to death; a sentence carried out swiftly – only a few days before the passing of the Murder Act, which effectively abolished capital punishment in Great Britain. He’d been one of the very last men to hang. Whether this in itself was a sore point with Elsie, Shirley didn’t know. But it couldn’t have helped.Strangely, though the bereaved woman had proclaimed her son’s innocence at the time, and had tried to claim that his penalty was an injustice, she’d afterwards come to accept it with surprising speed and dignity. There’d been no histrionics in the following months, no letters to the newspapers or the Home Secretary. When, over the next few years, the policeman who’d arrested Tommy – Shirley thought he was called Mackeson – had occasionally come to visit Elsie, she’d maintained a cold but proud silence. Of course, Elsie was part of that steely World War II generation, who kept their grief and rage buried deep inside, only allowing it to surface now and then – like when her local church, previously a source of strength during her difficult years as a young widow, had refused even to acknowledge that there might be hope for her son in the afterlife.

HAG FOLD

HAG FOLDWhen a run-down inner city district is terrorised by a sex-killer, a brutal firearms cop is brought in. He knows this area well. He grew up here. It left its mark on him as surely as it did the killer.

There’d already been numerous replacements at the top, senior investigators having been sacked, sidelined or forced through overwork into early retirement. A catalogue of errors, initially caused by a preponderance of evidence so vast it literally overwhelmed the pre-computer age intelligence system, had received glaring press attention and had been referred too scornfully in the House of Commons. We’d had the usual barrel-load of hoaxes, some obvious, some not so obvious, but all of which had had to be investigated, which had soaked up yet more time and manpower. Experts from Scotland Yard had been called in, but had failed to make an impact. Even the FBI had been contacted; they’d provided GMP detectives with a detailed profile of the killer, but that too had failed to get results. There’d been door-to-door questionings, traffic spot-checks, random stop-and-searches, follow-up interviews based on all vehicle registrations spotted in the district – still nothing. There’d even been widespread blooding for DNA, though that hadn’t been much use as the Strangler always took care to wear a condom when he raped. It’s probably fair to say that as much as was humanly possible was being done, but as long as the maniac was at liberty to strike, that wasn’t going to be enough. By the time I transferred to GMP, we had ‘Men Off The Streets’ marches to contend with, ‘Reinstate The Death Penalty’ protests, ‘public vigilance committees’ – basically gangs of drunken hooligans who got off on harassing strangers once the pubs had chucked-out, and a constant stream of well-meaning cranks, who poured into police stations armed with everything from crystal balls to divining rods. I avoided all this for as long as I could, putting in for one training course after another, sitting my sergeant’s exam, even volunteering to work Firearms at the airport. It might not sound very public-spirited of me, but let me tell you there is nothing even vaguely romantic about wandering the backstreets all night dressed as a tramp, or going house-to-house all day with an artist’s impression so vague it could be your own uncle and you wouldn’t recognise him. But after the Beverly Jones murder – she was the yummy mummy dragged from her own back garden – the shit really hit the fan. There was wholesale panic: police stations were besieged; patrol cars got jeered at; chief superintendents ran amok in their own offices ...

I hope all that was of interest. Sorry again ... there was quite a bit of self-pimpery there, but people often ask me these days what other books of mine can they read?, so I guess it’s only fair to post the details here. And as I say, at this time of year, it makes a kind of sense to focus those earlier publications that were specifically tailored for this dark and wintry time of year. Of course, as I mentioned at the top, it isn’t just me who prefers his horror to be a dish served ice-cold.

Now at last - I'm sure some of you must be thinking that - we reach that part of the programme where we talk about a different writer ...

THRILLERS, CHILLERS, SHOCKERS AND KILLERS ...

An ongoing series of reviews of dark fiction (crime, thriller and horror novels) – both old and new – that I have recently read and enjoyed. I’ll endeavour to keep the SPOILERS to a minimum; there will certainly be no given-away denouements or exposed twists-in-the-tail, but by the definition of the word ‘review’, I’m going to be talking about these books in more than just thumbnail detail, extolling the aspects that I particularly enjoyed … so I guess if you’d rather not know anything at all about these pieces of work in advance of reading them yourself, then these particular posts will not be your thing.

DARK MATTER

by Michelle Paver (2011)

DARK MATTER

by Michelle Paver (2011)